Abstract

In clinical medicine it is of interest to know vitamin C blood levels. There are numerous variations in published sample preparation methods for quantifying vitamin C using HPLC. For the determination of vitamin C in human probes, the method needs to be simple, fast, and accurate. A systematic search in Pubmed was carried out to identify the methods for the quantification of vitamin C with HPLC in combination with a UV detector in human plasma. A total of 83 reports were screened, from which seven methods were selected and examined in detail. Tabular overviews compare the different sample preparation options, HPLC parameters, and validation criteria. Different reagents for protein precipitation and extraction are discussed. By allowing the user to see the criteria of interest at a glance, it can be used as a tool for the rapid development and establishment of a vitamin C determination method using HPLC.

1. Introduction

1.1. Vitamin C—Structure, Function, and Occurrence

Vitamin C is called L-ascorbic acid (AA) and its chemical formula is C6H8O6 [1]. Chemically, vitamin C is known as 2-oxo-L-threo-hexono-1,4-lactone-2,3-enediol [1]. The vitamin C redox system comprises the reduced form ascorbic acid (AA), the oxidized form dehydroascorbic acid (DHA), and the free radical intermediate, semi-dehydroascorbic acid [2]. Under biological pH, the main form of vitamin C is AA [3].

AA is rapidly oxidized to DHA due to its structure (two hydroxyl groups) [4]. This oxidation reaction can occur under elevated temperature, high pH, light, oxygen, and metals. It is reversible and is the cause for the antioxidant activity of ascorbic acid. While DHA is significantly more stable than L-ascorbic acid, it can be irreversibly hydrolyzed to 2,3-diketogulonic acid (DKG). DKG has no biological function, and the reaction is irreversible. The AA/DHA ratio can be an indicator of an organism’s redox state [2].

Ascorbic acid is one of the essential vitamins and is necessary for human health [5]. Vitamin C has various functions in humans, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and immune boosting effects [6]. It acts in the human body as a cofactor for enzymatic reactions and as an electron donor [5]. Vitamin C is involved in different biological functions, such as metabolism of carnitine and catecholamine, absorption of iron from food, normal function of the immune system, and biosynthesis of collagen [7]. Ascorbic acid is considered a low molecular weight, water-soluble antioxidant [2]. Vitamin C acts as an antioxidant by catching free radicals, and mitigates the effects of oxidative stress in various diseases [3,8].

The human body cannot produce ascorbic acid. The lack of ability to synthesize vitamin C is due to a mutation in the gulonolactone oxidase gene leading to the absence of this enzyme, which is responsible for the synthesis of L-ascorbic acid from L-gulono-1,4-lactone [1,9]. Therefore, ascorbic acid must be administered to humans through food or supplementation and absorbed via the intestines [1].

Ascorbic acid is readily available in food [1]. It can be found in fresh fruits and vegetables, including oranges, lemons, grapefruit, watermelons, and strawberries, as well as green leafy vegetables, broccoli, cauliflower, and red peppers [1].

Vitamin C deficiency is associated with scurvy and malnutrition, but also with multiple diseases such as heart diseases, inflammation, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, delayed wound healing in smokers, mood and psychiatric disorders, immune reactions, and respiratory infections [10].

Vitamin C is an important dietary antioxidant [1]. It reduces the negative effects of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. These can cause oxidative damage to macromolecules such as lipids, proteins, and DNA, which in turn are implicated in numerous diseases such as strokes, cancer, and neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases [1].

Vitamin C is recommended to prevent the common cold [11,12]. Ascorbic acid has also been discussed for the prevention of arteriosclerosis [1]. Lipid peroxidation and oxidative modification of low-density lipoproteins have been linked to the development of arteriosclerosis [1]. Vitamin C protects against oxidation caused by various types of oxidative stress. Ascorbic acid plays a role in wound healing and regeneration, stimulating collagen synthesis. Therefore, an adequate supply of ascorbic acid is necessary for a normal healing process [1].

1.2. Sampling, Sample Preparation and Analysis

1.2.1. Measurand

Different vitamin C forms can be determined [13]. Measurement of AA only, separate measurement of AA and DHA, and measurement of total vitamin C (sum of AA and DHA) are possible. Separate measurement of AA can lead to an underestimation because some vitamin C is likely converted to DHA [13]. This also results in an underestimation of total antioxidant availability, since DHA has approximately the same biological activity as AA [13]. DHA is usually calculated by subtracting the AA amount from total vitamin C [13]. The simultaneous determination of both AA and DHA is difficult due to their different physicochemical properties [14]. It can be achieved through a so-called double analysis using a redox reaction: the oxidation of one substance and the reduction of the other, followed by subtraction. However, this method is not specific and is susceptible to interference from other reducing agents [14].

1.2.2. Sample

Plasma is considered the most frequently used matrix for vitamin C analysis, largely because its measurement is fast, simple, and analytically accessible compared with tissue-based methods [13]. Although vitamin C concentrations in tissues can be up to 100-fold higher, plasma levels change more rapidly and therefore reflect short-term fluctuations, such as increases following supplementation or declines due to insufficient intake.

In contrast, concentrations in leukocytes vary less and are considered a better indicator of the body’s longer-term vitamin C reserves [13].

Determining vitamin C levels in lymphocytes and leukocytes is another approach to assess vitamin C status [15]. These are not acutely influenced by changes in diet or circadian rhythm [15]. The methods of determination of vitamin C in lymphocytes and leucocytes are not part of this publication.

1.2.3. Blood Collection

For sample collection, peripheral venous blood is taken from a subject and is collected in a tube containing lithium heparin or EDTA as anticoagulants.

It was found that K2-EDTA, lithium heparin, and serum tubes are well-suited for total vitamin C analysis because the DHA is reduced back to AA before measurement [13]. The choice of anticoagulant is therefore crucial [14]. Heparin and EDTA on ice are best, as L-ascorbic acid is unstable with gel or fluoride anticoagulants [14]. Vitamin C remains most stable in heparin during the first few hours [6]. EDTA samples and whole serum are unstable at room temperature, with losses of up to 15–20% within two hours. EDTA chelates of iron and copper can remain reoxidatively active at physiological pH and can lead to the oxidation of ascorbate at room temperature [6].

1.2.4. Sample Preparation

The analysis of vitamin C in blood samples using HPLC presents several challenges. These include instability of the analyte, but also inefficient handling of the sample prior to analysis [10]. Before analytical analysis, sample preparation must be carried out, which is required for accurate analysis [16]. It is necessary to remove the interferent compounds, so that the analyte can be analyzed.

One main step in the sample preparation is protein precipitation. Many protein precipitants are acids. Acids not only precipitate proteins, but also prevent the hydrolysis of the lactone ring of vitamin C, or lead to the inhibition of oxidation.

Acids such as metaphosphoric acid (MPA) and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) are commonly used [16].

Before analysis, the compounds should be in a stable form [3]. To increase stability (prevention of analyte degradation due to oxidation), a reducing agent such as MPA, tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) or dithiothreitol can be added to the sample [10]. The reduction of DHA to AA is described as significant in biological samples before HPLC analysis [3].

The following factors influence oxidation in plasma samples: temperature, pH, sample concentration, oxygen, light, presence of iron ions, solvents, oxidizing enzymes, and ionic strength of the solution [3]. Therefore, vitamin C samples must be protected from light and stored frozen [17].

Some laboratories report analysis of total vitamin C by reducing DHA to AA prior to analysis [10]. Analysis methods that do not perform the reduction step by not containing an antioxidant thus measure only AA, and in these cases, the overall vitamin C status is not sufficiently specified [10].

1.2.5. Analysis

There are numerous assays for the measurement of AA and DHA [3]. They can be divided into three categories: spectrometric, enzymatic, and chromatographic assays [3]. Spectrometric and enzymatic methods show low sensitivity and specificity, and are susceptible to biological interference [3,13]. These methods can interfere with analytes (e.g., iron(III) or copper(I) ions, sugars or glucuronic acid (spectrophotometry), or citrate and hydrogen peroxide (enzymatic methods)) [4]. If other substances absorb UV light at the utilized wavelength, it leads to an overestimation of AA in biological samples [4].

Newer methods use the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method in combination with ultraviolet (UV), fluorescence, or electrochemical (EC) detectors and mass spectrometry [3,17]. Detection of DHA using EC and UV detectors is limited due to low response [3]. Therefore, the oxidation of AA to DHA must be prevented when a UV detector is used. This can be done by derivatization of AA, sample preparation under very acidic pH conditions, or the use of ion pairing reagents such as cationic detergents (e.g., tridecyl ammonium formate and octylamine) [18].

In general, HPLC is the preferred analytical method because it offers higher selectivity than spectrometric, tritrative, and enzymatic methods, and does not require derivatization [4].

1.3. Clinical Relevance and Aim of This Work

The intake of vitamin C correlates with its concentration [17]. Studies generally show the frequent association between low vitamin C intake and low plasma concentration [9]. The most readily available biomarker for vitamin C status is its plasma concentration [9]. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) usually occurs in plasma at a concentration of 30 to 80 µmol/L [18,19]. Reduced plasma concentrations of vitamin C are frequently observed in critically ill patients with sepsis, bleeding, trauma, after cardiac arrest, and burns [6]. In patients with septic shock, the level of vitamin C was often reported to be below 23 µmol/L [6].

Values below 11 μmol/L describe a deficiency and are associated with the clinical symptoms of scurvy, although heavy scurvy is rare these days [9,15,17].

Causes of a deficiency can include reduced intake and absorption, increased metabolic consumption, and reduced utilization as a result of severe oxidative stress [6].

During severe oxidative stress, vitamin C is rapidly consumed, and regeneration is insufficient, leading to a deficiency. Consequently, the body is no longer adequately protected against oxidative stress. This supports the use of vitamin C supplementation in cases of deficiency and severe oxidative stress [6].

There is increased clinical interest in measuring vitamin C levels in patients, as it is used to assess nutritional status and to monitor vitamin C supplementation [10,17]. Measuring vitamin C levels thus allows a better correlation between dose, concentration, and clinical outcome [6].

The standard for measuring vitamin C in plasma is the use of HPLC. The measurement is performed in a variety of laboratories [15]. Various methods for the analytical quantification of vitamin C in blood samples using HPLC have been published in the literature [10,16,20]. The various methods differ from each other not only in the HPLC parameters but also in the sample preparation. The sample preparation requires a sequence of steps: protein precipitation, form stabilization (e.g., reducing DHAA to AA), separation activities, evaporation, and concentrating the sample (reducing the volume).

A method for vitamin C analysis using HPLC should be simple, sensitive and feasible in any normally equipped clinical laboratory. The aim of this publication is to provide an overview of published methods. For this purpose, a systematic literature search was carried out. The presented methods describe the quantification of vitamin C using HPLC in combination with a UV detector in human plasma. The individual methods are summarized in a table showing the different approaches to sample preparation. This makes it possible to determine similarities and differences between the individual sample preparation methods. Additionally, we examined which publications reported the quality criteria of their described method. The stated limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), and reference values are compared.

Our tabular overview is intended to enable the user in the laboratory to see criteria that are of interest at a glance, which can thus serve as a tool for the development and establishment of an HPLC vitamin C analysis method in combination with a UV detector for human blood samples.

2. Methods

Database Search Strategy

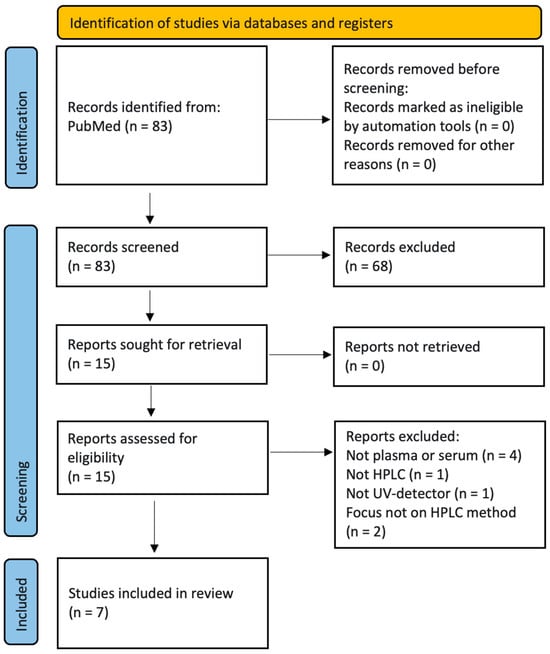

The systematic literature search was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines within the scope of the applicability of the criteria [21] (see Table S1).

The online database PubMed was searched using the following search terms:

(vitamin* C OR vitamin-c OR acidum ascorbicum OR ascorbic acid)

AND (HPLC OR “high-performance liquid chromatography” OR “high-pressure liquid chromatography”)

AND (plasma OR blood OR serum)

AND (UV detect*).

The search was executed on 6 July 2024.

- Selection of publications

The abstracts of all results were screened for inclusion in the full-text review. Full-text articles were selected for inclusion into this review by using the inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 1. Manuscripts which presented methods or modified extraction procedures were included. Manuscripts presenting applications without new methodological adjustments were excluded.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Data collection, extraction, and analysis

To evaluate the published methods for vitamin C quantification, a thorough qualitative analysis was performed using the extracted data. Two independent reviewers documented key characteristics of the different methods, including the procedures for precipitation, form stabilization, separation activities, and purification used in sample preparation. Additional parameters such as the mobile phase composition, flow rate, column specifications, injection volume, HPLC oven temperature, and UV detector wavelength were recorded. The analysis also included information on LOD, LOQ, and reference values. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through discussion. The results were summarized in tables.

3. Results

3.1. Search

The search and selection process is shown in the flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram according to PRISMA 2020 [21].

After title and subsequent abstract screening by two scientists, seven papers were selected for further analysis.

3.2. Reporting on Sample Preparation, HPLC Parameters and Quality Criteria

We extracted the applied methods for sample preparation, the HPLC parameters, as well as the reported quality criteria from the literature. Table 2 lists the selected publications and shows which criteria were reported in the manuscripts. The studies present the development of analytical methods; therefore the results were summarized only narratively.

Table 2.

Reporting of analytical process and quality criteria. Green: criterium fulfilled, red: not fulfilled.

Tavazzi et al. [22] and Karlsen et al. [3] both reported all three predefined quality criteria, which are important for the evaluation of a method (LOD, LOQ, and reference values). Two of the three criteria were reported by van Gorkom et al. [5], Robitaille et al. [20], as well as Kand’ár et al. [16]. Fitzpatrick et al. [10] only determined the LOQ.

Most of the details of the HPLC parameters (e.g., flow rate, injection volume, HPLC oven temperature, detector wavelength) were mentioned by all publications. The individual values can be found in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Sample preparation steps and parameters of the HPLC.

Table 4.

Parameters of the HPLC column.

3.3. Process Characteristics

3.3.1. Extraction and Measurement

Table 3 shows the sample preparation steps in detail. For protein precipitation different reagents were used. MPA was usually used for precipitation, either in a concentration of 10% or in combination with other reagents like acetonitrile. Tavazzi et al. [22] did not use a precipitation reagent but used a filter (3 kDa cut-off) for removement of disturbing substances.

Some authors reduced DHA to AA by adding TCEP as reducing agent. Kand’ár et al. [16] filtered the extract before measuring it using HPLC through a 0.20 μm nylon filter, to remove interfering components so that the analysis column does not clog.

A reversed-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) apparatus was mostly used for the determination of vitamin C (5 of 7 methods). Fitzpatrick et al. [10] used ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) and van Gorkom et al. [5] reported the usage of hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC).

The largest difference between the reported HPLC methods can be seen in the selection of the mobile phase. Acetonitrile is often a component of it. Normally, an isocratic elution was done. Only Tavazzi et al. [22] used a step gradient. The applied flow rates were between 0.5 and 6.0 mL/min. The reported injection volumes were between 5 and 20 μL, and the temperatures of the oven increased from 10, 25, and 30 until 40 °C. Kand’ár et al. [16] assessed the influence of different oven temperatures and found that the optimum was 25 to 30 °C.

Ascorbic acid was measured by UV detectors set at values between 245 and 265 nm by the various groups.

3.3.2. Method Validation

In Table 5 the quality values of the selected methods are shown. Ross et al. [18] are not included in this table, because they did not report any of these values.

Table 5.

Quality criteria of the selected papers.

All of the stated LOD and LOQ—being below 5 μmol/L—are low enough to measure normal vitamin C levels accurately. The lowest limits were achieved by Tavazzi et al.’s method [22].

Fitzpatrick et al. and Robitaille et al. did not determine the LOD values. Fitzpatrick did not mention the reference value. Kandar et al. and van Gorkom et al. did not calculate the LOQ values.

4. Discussion

4.1. Method Selection

We found seven methods for the quantification of vitamin C using HPLC with a UV detector. The methods are quite similar. They differ in the mobile phase used during HPLC analysis and in the procedure of separating vitamin C from the other sample components by protein precipitation, centrifugation, or filtration.

Tavazzi et al. achieved the lowest LOD and LOQ values and were the only group that did not use a chemical reagent for sample purification. Instead, they filtered the plasma before HPLC analysis. Filtering consumes some time, but on the other hand, time and reagents for protein precipitation are saved using this method [22].

The method of Tavazzi et al. also incorporates ion-pairing, which may add another layer of complexity to the analysis [22]. Ion-pair chromatography improves the retention and resolution of highly polar or ionic compounds that are poorly retained on conventional reversed-phase columns by forming temporary ion pairs with a reagent added to the mobile phase [22]. This approach allows simultaneous separation of neutral and charged analytes with enhanced selectivity [23].

Alternative methods, such as Kand’ár et al.’s mixture for protein precipitation, are also acknowledged, but they can be labor-intensive [16]. On the other hand, the method of Karlsen et al. [3], utilizing rapid HPLC with a retention time of 0.7 min, has demonstrated good values despite its more involved reduction reaction [3].

Sample preparation is complicated, and various approaches exist. The method of Fitzpatrick et al., which employs a robotic system for plate-based sample preparation, allows for the simultaneous processing of multiple samples, significantly enhancing throughput compared to tube-based preparations [10]. The automatic sample preparation approach results in less sample loss due to pipetting errors compared to a manual pipette. Meanwhile, the approach of Van Gorkom et al. [5] uses acetonitrile and MPA for sample handling but reports longer retention times, which could impact efficiency [5].

Robitaille et al.’s technique is particularly noted for its straightforward purification process, utilizing a mobile phase with minimal reagents and isocratic elution, making it an appealing option for laboratories looking for efficient protocols [20].

Most methods involve centrifuging samples, except for that of Tavazzi et al. [22]. Parameters such as injection volume, oven temperature, and flow rates are generally determined experimentally. Most laboratories also adjust the pH of the mobile phase, ensuring it remains within an acidic to neutral range to optimize the analysis.

The method of Tavazzi et al. also incorporates ion-pairing, which may add another layer of complexity to the analysis [22].

4.2. Sample Preparation and Analytical Consideration

This section will be a consideration of aspects related to sample preparation and analytical possibilities.

Vitamin C exists primarily in the form of AA (reduced) and DHA (oxidized). The determination of vitamin C can be complicated, as not all methods measure the same forms—AA, DHA, or total vitamin C [13].

4.2.1. Sample Preparation

To prepare the sample and precipitate plasma proteins (deproteinization), stabilizers or acids such as trichloroacetic acid (TCA), homocysteine, trifluoroacetic acid, oxalic acid, metaphosphoric acid (MTA), or perchloric acid are added to the sample, or metal chelators such as EDTA (for chelating unwanted metal ions) or diethylenetriamphenicol pentaacetic acid (DTPA) are used instead of a reducing agent [13,14].

Deproteinization and stabilization can also be achieved by adding a modifier such as organic methanol [6].

A common method for extracting and purifying vitamins is liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) [24]. However, this method is not well-suited for high-throughput routine or clinical applications, nor for experimental work, due to the use of highly toxic volatile compounds.

Solid phase extraction (SPE) is one of the most common methods for sample preparation and is used to analyze vitamins in various matrices. Its advantages include complete phase separation, high yield, and low consumption of organic solvents [24]. The standard SPE method consists of four steps: conditioning, sample adsorption, washing, and elution [25]. This method for extracting and purifying analytes is very time-consuming and prone to errors. An improved method, online solid phase extraction liquid chromatography (online SPE-LC), is gaining increasing attention. Its advantages include reduced sample preparation time and manual effort resulting in high sensitivity and accuracy of the results [25].

4.2.2. Analysis

Internal Standard

In the routine determination of L-ascorbic acid, an internal standard is not used. It is difficult to find a compound suitable for both extraction and analytical steps that is similar to L-ascorbic acid [14].

Iso-ascorbic acid is used in analytical chemistry, but its usefulness is limited by its potential presence in biological samples. Substances such as tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride are also used, but they can undergo similar redox reactions to L-ascorbic acid [14].

The simultaneous determination of AA and DHA precluded the use of these as internal standards [4]. Hippuric acid, nicotinic acid, uric acid, chlorogenic acid, or 4-hydroxyacetanilide have been used as internal standards in HPLC analysis for AA/DHA [4].

RP-HPLC

RP-HPLC consists of a nonpolar stationary phase and a polar mobile phase [26]. This type of HPLC column is widely used in chromatographic analysis due to its performance, selectivity, and practical applicability. Nonpolar stationary phases include C4, C8 (octyl), C18 (octadecyl), and octadecylsilane (ODS) columns [26]. However, reversed-phase methods often exhibit insufficient resolution of AA and DHA [4].

Mobile Phase and Elution

The mobile phases contain usually more than two components, including various modifiers or reagents.

In isocratic elution, the mobile phase remains constant and circulates uniformly throughout the separation process [27]. The elution constant and polarity constant remain constant during the run [27].

Some studies (like Tavazzi et al. [22]) have explored gradient methods. In gradient elution, the polarity or elution strength increases during the separation process [27]. There is the possibility of a linear gradient with continuous change of the mobile phase composition, or of a step gradient like Tavazzi et al. used.

While a linear gradient is a solution for separation, it results in long run times [28]. This necessitates the use of (C-8) instead of octadecylsilane (C-18) chromatographic columns.

Detector Types

The choice of detector depends on the sample to be analyzed, its chemical properties, any impurities, the sample matrix, the detector’s sensitivity and availability, and the costs [26]. The most commonly used UV detector is the UV/VIS detector. Other optical detection systems include photodiode arrays (PDAs) and fluorescence detectors [26].

UV detection and electrochemical detection (ECD) are considered the most commonly used detection methods in HPLC [14]. Advantages of UV detectors (as well as of PDA) include its affordability. However, it is only suitable for quantifying ascorbic acid (due to DHA’s low absorption properties) [14].

The UV/VIS detector is an HPLC detector that utilizes a UV wavelength range of 200 to 400 nm and a visible wavelength range of 400 to 800 nm [26]. UV/VIS absorption photometry is based on measuring the attenuation of electromagnetic radiation by an absorbing substance. Generally, there are two types of UV/VIS detectors: fixed-wavelength detectors, which operate at a specific wavelength, and variable-wavelength detectors, which operate across a broad wavelength range [26]. The fixed-wavelength detector operates at a specific wavelength of, for example, 254 nm. Most active substances are absorbed at a low UV wavelength [27,29]. The variable-wavelength detector operates in a wavelength range (i.e., 190 to 600 nm) of which the desired wavelength for the specific analysis can be set. Both detector types show good stability and are easy to use [27].

The UV-VIS detector offers advantages such as reliability, ease of use, high precision, and high linearity, and is widely used in analytical chemistry [26]. Its limitations lie in the fact that the mobile phase must be transparent, and the detector response depends on the molar absorbance of the analyte. This first challenge can be overcome by carefully selec-ting a mobile phase [26].

By using a UV detector, only AA can be detected, but if DHA is reduced to AA prior to detection, total vitamin C can be measured. A common approach involves using TCEP as a reduction agent to convert DHA to AA, enabling the complete quantification of vitamin C [30].

The absorption maximum of L-ascorbic acid lies in the pH-dependent range of 244 to 265 nm [2,14]. DHA has low absorption at wavelengths above 220 nm [14]. Thus, the detection of DHA must be carried out at a much lower wavelength, i.e., 185 nm [4].

Fluorescence detection requires derivatization of DHA and additional oxidation of AA to DHA [4]. The reaction of DHA with dimethyl-o-phenylenediamine leads to a fluorescent quinoxaline derivative, which can be detected by a fluorescence detector [4]. Because of the time-consuming derivatization step, fluorescence detection is not widely used, and is used even less frequently than mass spectrometry [4,14].

HPLC-ECD offers selectivity and sensitivity, and is easily miniaturized [14]. Disadvantages include the risk of electrode contamination with real samples. [14]. DHA is electrochemically inactive, unlike L-ascorbic acid; for this reason, ECD detection of DHA is not possible [14].

Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) allows for the simultaneous detection of both AA and DHA [14]. HPLC-MS offers selectivity and the use of labeled internal standards [4]. Disadvantages include high equipment costs and the need for trained personnel [4,14].

The difficulty in developing HPLC methods with MS detection lies in matrix-induced signal suppression, as well as non-standard ionization patterns that lead to complex ion species. MS detection is generally performed in negative mode with electrospray ionization [14]. A low pH is required to counteract the degradation of AA in the sample, but MS detection is not compatible with ion-pairing reagents or EDTA, which makes it unsuitable for some HPLC methods for the measurement of vitamin C [14].

UHPLC

UHPLC has several advantages over conventional HPLC. It utilizes chromatographic principles for separation by employing short columns packed with smaller particles (below 2 µm) [31]. Compared to conventional HPLC, UHPLC offers improved peak efficiency (peak width), better resolution, and minimization of matrix effects [31,32]. UHPLC exhibits an improved signal-to-noise ratio, enabling the detection of analytes at very low concentrations [31]. The injection volume can be significantly reduced without loss of sensitivity. However, the use of short columns (50–100 mm) packed with particles below 2 µm is limited in conventional liquid chromatography due to the increased column backpressure (>40 MPa), which is incompatible with conventional instruments and thus represents a limitation. The UHPLC method is faster, more sensitive, and uses less eluent, and is also considered more environmentally friendly than conventional HPLC methods [31]. The total run time of a UHPLC apparatus is two to three times faster than that of the usual HPLC [33]. UHPLC is therefore more cost-effective than HPLC because a higher number of analyses can be performed per unit of time, and the reagent consumption is lower due to the reduced amount of eluent required [31].

HPLC Kits

In routine practice and clinical studies, commercial vitamin C kits are frequently used. HPLC kits contain chromatographic columns, mobile phases, extraction reagents, and controls. They are based on reversed-phase chromatography and exhibit higher selectivity and specificity than other types of L-ascorbic acid kits. However, they require complex instruments and are very expensive. [14].

HILIC

Hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) is an HPLC technique that uses a polar stationary phase and a highly organic mobile phase to retain and separate very polar and hydrophilic analytes through hydrophilic interactions [4]. HILIC would be very suitable for the determination of L-ascorbic acid [14]. HILIC offers an alternative to conventional RP-HPLC and it is particularly well-suited for the analysis of small and polar molecules that are poorly retained or eluted with the dead volume in conventional RP-HPLC [14].

Precision

Precision is a critical factor in any assay, with both intra- and inter-assay variability discussed in the literature. When evaluating different methods, it is important to balance precision, simplicity, and time efficiency. The methods employed must also be relevant for practical applications in clinical settings.

4.2.3. Summary

In summary, the measurement of vitamin C in plasma involves a range of methods and considerations. While UV detection after HPLC is a common option, the choice of chromatography, sample preparation techniques, and the use of reduction agents play significant roles in the accuracy and efficiency of the analysis. By focusing on simpler, quicker methodologies with effective automation, laboratories can enhance their productivity while ensuring reliable results. However, it is recommended to use methods that are simple and sensitive and can be used with the laboratory’s normal laboratory equipment.

4.3. Limitations and Strengths

This report is a systematic review and provides an overview of different sample preparation methods for the analysis of vitamin C using HPLC in combination with a UV detector in human blood samples. It shows the similarities and differences between the sample preparation steps, HPLC parameters and quality criteria.

A comprehensive search of the PubMed research database was performed. A search on other platforms was not conducted. Each step of manuscript selection, assessment and data extraction was executed independently by two researchers to reduce the selection and assessment bias. Each study was critically discussed with respect to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The main focus of this review is a methodical comparison. During the literature search, studies with an application-oriented approach were also found, and excluded manually.

Different detection methods can be employed to measure vitamin C after HPLC, including UV detection, electrochemical detection, and mass spectrometry. In this work we only looked at methods using an UV detector. They provide reliable measurements of AA concentrations, though the wavelengths used may vary slightly among studies, necessitating the review of chromatograms to ascertain the maximum absorption for AA, which is between 244 and 265 nm [2,14]. For the determination of vitamin C, a HPLC in combination with a UV detector has shown equivalent performance to an EC detector [13]. When determining different redox forms, other detectors must be used.

In this work only methods for the quantification of vitamin C in human blood samples (plasma) are presented, and not for the quantification in other tissues such as lymphocytes, body organs, animals, and food. Some authors like van Gorkom et al. recommend measuring vitamin C in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) rather than in plasma [5]. Plasma levels of vitamin C tend to reflect the recent intake of the vitamin and may fluctuate depending on dietary habits and supplementation. In contrast, vitamin C levels in PBMCs are less prone to fluctuations. On the other hand, PBMCs require more extensive sample preparation, including cell isolation and potential lysing, which can introduce additional complexity to the procedure.

Plasma may offer a more direct measurement of circulating vitamin C levels, which is useful for assessing intake or deficiency, while PBMCs may provide a more stable and biologically relevant measure of vitamin C within cells. For long-term vitamin C status or cellular function, PBMCs may be more informative, but this comes at the cost of more complex sample processing.

The studies included show a large variation in design and reporting on the quality criteria. This reduces the transferability of the results.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that presents and compares vitamin C analysis methods using HPLC in combination with a UV detector regarding the sample preparation steps in detail for analyzing blood samples.

This comprehensive and detailed overview can therefore serve as a tool for the rapid development and establishment of an HPLC vitamin C analysis method in the laboratory. In order to use a method, the individual laboratory equipment must be taken into account, and experimental adjustments to the analysis parameters are necessary.

4.4. Outlook

The aim of this systematic review was the comparison of different analytical methods to determine vitamin C with HPLC and UV detection. The focus was on the variations in sample preparation. Future research could involve HPLC methods with other detection methods or mass spectrometry, or extend the methods to other matrices.

Another approach could be to compare methods in terms of their adherence to green chemistry principles.

4.5. Conclusions

Measurement of vitamin C is crucial for identifying patients with low levels of this vitamin, which may be associated with various health conditions. Therefore, there is a need for a rapid, simple, and sensitive method for vitamin C analysis that can be implemented as a standard procedure in clinical laboratories.

Several methods for quantifying vitamin C using HPLC have been described in the literature. These methods generally require multiple sample preparation steps before instrumental quantification. The present systematic review provides an overview of the various sample preparation techniques for quantifying vitamin C in human plasma using HPLC apparatus in combination with a UV detector.

Of 83 reports retrieved from the PubMed database, seven methods were selected. These methods were summarized in a table, which outlines the sample preparation steps and HPLC parameters. Six publications were considered of high methodological quality due to the reporting of at least two of the three criteria LOD, LOQ, and reference values.

The tabular summary enables a comparative evaluation of the methods based on their similarities and differences, and serves as a valuable tool for method development and validation for vitamin C quantification in laboratory settings. It provides a practical guide for selecting a method that aligns with the available equipment and reagents in a given laboratory. We recommend selecting a method that can be implemented easily and cost-effectively, and that is timesaving and precise using the laboratory’s existing equipment. For these reasons, the method of Robitaille et al. [20] using RP-HPLC seems to be the most interesting to us.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/analytica7010002/s1, Table S1.PRISMA checklist.

Author Contributions

M.D.: Conceptualization, Literature search, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. P.H.: Literature search, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of the research, data is not available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AA | ascorbic acid |

| DHA | dehydroascorbic acid |

| EC | electrochemical |

| HILIC | hydrophilic interaction chromatography |

| HPLC | high-pressure liquid chromatography |

| LLE | liquid–liquid extraction |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| LOQ | limit of quantification |

| MPA | metaphosphoric acid |

| RP-HPLC | reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography |

| SPE | solid phase extraction |

| TCA | trichloroacetic acid |

| TCEP | tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine |

| UHPLC | ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography |

| UV | ultraviolet |

References

- Naidu, K.A. Vitamin C in human health and disease is still a mystery? An overview. Nutr. J. 2003, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey, M.; Van Montagu, M.; Inze, D.; Sanmartin, M.; Kanellis, A.; Smirnoff, N.; Benzie, I.; Strain, J.; Favell, D.; Fletcher, J. Plant L-ascorbic acid: Chemistry, function, metabolism, bioavailability and effects of processing. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 825–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, A.; Blomhoff, R.; Gundersen, T.E. High-throughput analysis of vitamin C in human plasma with the use of HPLC with monolithic column and UV-detection. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2005, 824, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováková, L.; Solich, P.; Solichová, D. HPLC methods for simultaneous determination of ascorbic and dehydroascorbic acids. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2008, 27, 942–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gorkom, G.; Gijsbers, B.; Ververs, E.J.; El Molla, A.; Sarodnik, C.; Riess, C.; Wodzig, W.; Bos, G.; Van Elssen, C. Easy-to-Use HPLC Method to Measure Intracellular Ascorbic Acid Levels in Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells and in Plasma. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozemeijer, S.; van der Horst, F.A.L.; de Man, A.M.E. Measuring vitamin C in critically ill patients: Clinical importance and practical difficulties-Is it time for a surrogate marker? Crit. Care 2021, 25, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, A.; Moldoveanu, E.T.; Niculescu, A.G.; Grumezescu, A.M. Vitamin C: A Comprehensive Review of Its Role in Health, Disease Prevention, and Therapeutic Potential. Molecules 2025, 30, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttger, F.; Vallés-Martí, A.; Cahn, L.; Jimenez, C.R. High-dose intravenous vitamin C, a promising multi-targeting agent in the treatment of cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, M.; Eck, P. Dietary Vitamin C in Human Health. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 83, 281–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M.; Bonnitcha, P.; Nguyen, V.L. Streamlined three step total vitamin C analysis by HILIC-UV for laboratory testing. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2021, 59, 1944–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykkesfeldt, J.; Michels, A.J.; Frei, B. Vitamin C. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambial, S.; Dwivedi, S.; Shukla, K.K.; John, P.J.; Sharma, P. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: An overview. Indian. J. Clin. Biochem. 2013, 28, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, J.T.B.; Greaves, R.F.; Jones, O.A.H.; Eastwood, G.; Bellomo, R. Vitamin C measurement in critical illness: Challenges, methodologies and quality improvements. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2020, 58, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doseděl, M.; Jirkovský, E.; Macáková, K.; Krčmová, L.K.; Javorská, L.; Pourová, J.; Mercolini, L.; Remião, F.; Nováková, L.; Mladěnka, P.; et al. Vitamin C-Sources, Physiological Role, Kinetics, Deficiency, Use, Toxicity, and Determination. Nutrients 2021, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadi-Konjin, P.; Verjee, Z.; Levin, A.V.; Adeli, K. Measurement of intracellular vitamin C levels in human lymphocytes by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Clin. Biochem. 2005, 38, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kand’ár, R.; Záková, P. Determination of ascorbic acid in human plasma with a view to stability using HPLC with UV detection. J. Sep. Sci. 2008, 31, 3503–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Z.D.; Frank, E.L. Development and implementation of an HPLC-ECD method for analysis of vitamin C in plasma using single column and automatic alternating dual column regeneration. Pract. Lab. Med. 2016, 6, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.A. Determination of ascorbic acid and uric acid in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 1994, 657, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for vitamin C. EFSA J. 2013, 11, 3418. [CrossRef]

- Robitaille, L.; Hoffer, L.J. A simple method for plasma total vitamin C analysis suitable for routine clinical laboratory use. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavazzi, B.; Lazzarino, G.; Leone, P.; Amorini, A.M.; Bellia, F.; Janson, C.G.; Di Pietro, V.; Ceccarelli, L.; Donzelli, S.; Francis, J.S.; et al. Simultaneous high performance liquid chromatographic separation of purines, pyrimidines, N-acetylated amino acids, and dicarboxylic acids for the chemical diagnosis of inborn errors of metabolism. Clin. Biochem. 2005, 38, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auclair, J.; Rathore, A.S.; Bhattacharya, S. The Role of Ion Pairing Agents in Liquid Chromatography (LC) Separations. LCGC N. Am. 2023, 41, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.E.; Yan, J.Q.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, X.; Ma, Y.L.; Feng, X.S.; Yang, J.; Li, G.H. A Review of the Extraction and Determination Methods of Thirteen Essential Vitamins to the Human Body: An Update from 2010. Molecules 2018, 23, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, N.H.; Osman, R.; Abidin, N.; Kassim, N.S.A. Recent trends in the quantification of vitamin b. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2021, 25, 466–482. [Google Scholar]

- Handini, A.; Husni, P.; Agustin, I. Comparative Study of HPLC Detectors in PT. FIP: A Review. Calory J. Med. Lab. J. 2025, 3, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, C.; Minocha, N.; Purohit, D.; Kumar, S.; Makhija, M.; Saini, S.; Kaushik, D.; Pandey, P. High Performance Liquid Chromatography: Recent Patents and Advancement. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2022, 15, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topkoska, M.; Miloshevska, M.; Piponski, M.; Lazarevska Todevska, E.; Slaveska Spirevska, I.; Acevska, J. Development of RP HPLC method with gradient elution for simultaneous Resveratrol and Vitamin E determination in solid dosage forms. Maced. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 68, 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, M. HPLC detectors: A brief review. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2010, 33, 1130–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykkesfeldt, J. Determination of ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid in biological samples by high-performance liquid chromatography using subtraction methods: Reliable reduction with tris[2-carboxyethyl]phosphine hydrochloride. Anal. Biochem. 2000, 282, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, I.; Gliszczyńska-Świgło, A. Comparison of UPLC and HPLC methods for determination of vitamin C. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.F.; Franke, A.A. Analysis of circulating lipid-phase micronutrients in humans by HPLC: Review and overview of new developments. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2013, 931, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paliakov, E.M.; Crow, B.S.; Bishop, M.J.; Norton, D.; George, J.; Bralley, J.A. Rapid quantitative determination of fat-soluble vitamins and coenzyme Q-10 in human serum by reversed phase ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography with UV detection. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2009, 877, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.