Abstract

Despite substantial progress in the field of bladder cancer management, the disease continues to represent an important health issue characterized by increased recurrence and progression rates. This is largely attributed to cancer stem cells (CSCs), a unique cell subpopulation capable of self-renewal, differentiation and resistance to conventional anti-cancer therapies. At the same time, our understanding of cancer biology has been revolutionized by the identification of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), a heterogeneous group of RNA molecules that do not translate into proteins yet function as pivotal regulators of gene expression. Emerging evidence demonstrates that ncRNAs modulate key hallmarks of CSCs, including self-renewal, epithelial–mesenchymal transition and drug resistance. This review investigates the intricate interplay between ncRNAs and the core signaling pathways that underlie bladder CSC biology. Unravelling the nexus between CSCs and ncRNAs is crucial for developing novel diagnostic biomarkers, better prognostic tools and innovative therapeutic strategies for patients with bladder cancer.

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer represents a significant global health challenge. According to GLOBOCAN 2022 estimates, there were 613,791 new cases and 220,349 deaths recorded worldwide, establishing it as the 9th most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the 13th leading cause of cancer-related mortality [1]. Bladder cancer is clinically divided into two broad classifications: non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). NMIBC is typically managed with conservative approaches, such as endoscopic resection and risk-based intravesical therapies. Muscle-invasive disease requires radical treatments, including the surgical excision of the bladder, often in combination with cisplatin-based chemotherapy and radiation [2,3].

Despite notable advancements in treatment modalities and the increased awareness regarding patient surveillance and follow-up, the rates of bladder cancer progression and recurrence remain considerably elevated [4,5]. The therapeutic resistance of certain tumors is increasingly attributed to a subpopulation of tumor-initiating cells known as cancer stem cells (CSCs). Characterized by their capacity for self-renewal, differentiation, and high tumorigenicity, CSCs sustain tumor growth, generate intra-tumoral heterogeneity, and can promote disease progression and metastasis, posing a significant barrier to effective treatment [6,7].

Currently, our understanding of genomic regulation has been revolutionized by the identification of an extensive network of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). The central dogma of molecular biology states that genes are DNA sequences transcribed into messenger RNAs (mRNAs), which are then translated into proteins [8]. However, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project revealed that over 80% of the human genome is biochemically active, a figure that stands in stark contrast to the small fraction of the genome that is translated into proteins [9]. NcRNAs are defined as RNA molecules that do not translate into proteins. Once dismissed as transcriptional noise, this heterogenous group of molecules are now recognized as master regulators of gene expression, at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [10]. ΝcRNAs are broadly categorized by size into small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs), shorter than 200 nucleotides, and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which exceed 200 nucleotides in length [10]. Each class is characterized by unique biogenesis, structure, and mechanisms of action. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short transcripts that post-transcriptionally suppress the expression of their target mRNAs [11]. LncRNAs are versatile molecules that can act as molecular scaffolds, guides, or decoys [12]. Another critical class, circular RNAs (circRNAs), are formed into a covalently closed loop, a structure that confers exceptional stability and allows them to function as robust miRNA sponges [13,14].

The intricate interplay between ncRNAs and the signaling pathways that govern CSC biology is emerging as a pivotal axis in cancer progression. The scope of this review is to revisit the principles of CSCs and their role in bladder cancer, with a focus on delineating the specific interactions between key ncRNAs and the fundamental signaling pathways in which CSCs are involved, and to highlight the profound clinical relevance of these interactions. A deeper understanding of this regulatory nexus holds immense promise for the development of novel diagnostics, more accurate prognostic biomarkers, and innovative therapeutic strategies.

2. Hallmarks of Cancer Stem Cells

The initial compelling evidence for the existence of CSCs was presented by Bonnet and Dick in 1997 [15]. They identified a distinct subpopulation of leukemic cells characterized by the presence of CD34 and absence of CD38 antigens on their surface that demonstrated the ability to initiate cancer growth upon transplantation into immunocompromised mice and exhibited self-renewal properties [15]. A few years later, different groups were able to provide evidence of the presence of CSCs in solid tumors. Ignatova et al. isolated a specific subpopulation of cells from cortical glial tumors that exhibited several defining characteristics associated with stem cells, including clonogenic potential under specific in vitro conditions and transcriptomic profiles characteristic of both undifferentiated neural progenitors and reactive astrocytes (such as nestin), as well as of differentiated neural lineages, including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) [16]. The concept of a cell population capable of promoting tumor formation was further enhanced by the findings of Al-Hajj et al., who identified a rare subpopulation of breast cancer cells characterized by a CD44+/CD24-/lowlineage- surface marker profile capable of initiating tumor formation in vivo, even when transplanted in very small numbers [17].

CSCs are widely recognized as the cells at the root of tumor initiation due to their distinctive self-renewal and differentiation properties [18]. They demonstrate the capacity for asymmetric cell division, a process through which a single CSC produces one daughter cell that retains its stem-like properties, thereby preserving the CSC pool, and another cell that differentiates further, comprising the bulk of the tumor mass. This process establishes a cellular hierarchy that ensures the sustained propagation of the tumor by simultaneously maintaining the CSC reservoir and fueling tumor growth [19,20].

CSCs also contribute to tumor growth and progression by the secretion of pro-angiogenic factors, such as Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), thus promoting neovascularization and ensuring an adequate supply of oxygen and nutrients to the expanding tumor mass [7]. Hypoxia within the tumor microenvironment appears to amplify this process through stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1a), a molecule with a central role in oxygen homeostasis that promotes metabolic reprogramming in CSCs [21].

Finally, another critical feature of CSCs is their capacity to undergo Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition (EMT). EMT is a process orchestrated by the overexpression of transcription factors in CSCs, such as Snail, Slug, and Twist [22,23,24]. This phenotypical transition enhances the migratory and invasive properties of cancer cells, necessary to disseminate to distant organs. EMT programs are often linked with the activation of pluripotency factors like OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, reinforcing the stem-like state of these cells [25]. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) usually express different CSC markers, which, in association with the frequent detection of CSCs in metastatic sites, provides strong evidence that CSCs serve as the primary “seeds” of metastasis [7,26].

3. CSC-Mediated Treatment Resistance and Relapse

In addition to their involvement in cancer initiation and progression, CSCs play a critical role in the development of chemoresistance and tumor relapse. Unlike most neoplastic cells, CSCs exhibit distinct properties that allow them to withstand conventional anti-cancer treatments. Notably, CSCs can enter a quiescent state, a period of dormancy where they are not actively dividing. This attribute provides CSCs with a survival advantage, as it enables them to evade the cytotoxic impact of cancer therapies that predominantly target rapidly dividing cells [27,28]. Consequently, while conventional therapies may effectively eradicate most proliferating tumor cells, a population of CSCs can persist, which are capable of reinitiating tumor growth, often displaying heightened invasiveness and increased resistance to subsequent therapeutic interventions [29]. For example, a population of pre-leukemic hematopoietic stem cells harboring mutations in the DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha (DNMT3A) gene have been identified as a key reservoir for therapeutic resistance and tumor relapse in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). These mutant cells demonstrate increased resistance towards chemotherapy and persist during the remission stage of the disease, as evident by the stable or even increased allele frequency of the DNMT3A mutation observed in patients following treatment and during relapse [30].

Another study found that treatment of patient-derived and established glioma cell lines with temozolomide (TMZ), the standard chemotherapy for glioma, caused a steady increase in the glioma stem cell (GSC) population. Lineage-tracing studies revealed that TMZ exposure induced a phenotypic transformation, causing differentiated glioma cells to revert to a more primitive, stem-like state. These newly formed GSCs expressed key pluripotency and stemness markers (CD133, SOX2, Oct4, and Nestin) and, when implanted intracranially into nude mice, demonstrated enhanced engraftment and a more invasive behavior. This phenomenon suggests a potential mechanism for tumor relapse following treatment [31].

The resistance of CSCs to anti-cancer therapy is driven by several molecular mechanisms. A primary mechanism is their ability to shift between epithelial and mesenchymal states through the EMT process. EMT increases the plasticity of tumor cells and promotes the development of distinct subpopulations within the tumor [32]. The miR-200 family of miRNAs and miR-205 have been recognized as key regulators of EMT. These molecules act cooperatively to control the expression of two transcriptional repressors of E-cadherin, ZEB1 (also referred to as deltaEF1) and SIP1 (also called ZEB2). Both ZEB1 and SIP1 have been shown to play significant roles in EMT and tumor metastasis [33,34].

An additional mechanism contributing to the increased resistance of CSCs is their enhanced capacity for drug efflux. The overexpression of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily, a large family of transmembrane proteins, plays a pivotal role in facilitating the expulsion of cytotoxic agents and in conferring multidrug resistance (MDR). These transporters function as energy-dependent pumps, utilizing ATP hydrolysis to transfer various substrates across cellular membranes [35]. The clinical relevance of this mechanism is highlighted by the association of specific ABC proteins with CSC-mediated resistance in malignancies such as ovarian cancer, melanoma, and glioma [36,37,38].

Collectively, these adaptive strategies, ranging from quiescence and lineage plasticity to active drug efflux, highlight the formidable nature of CSCs as reservoirs of therapeutic resistance across diverse malignancies.

4. Bladder Cancer Stem Cells

The fundamental principles underlying CSCs are also relevant to bladder cancer. Bladder cancer stem cells (BCSCs) have been identified as a specific subpopulation that exhibits many of the previously described hallmarks and is considered pivotal in driving tumor initiation, recurrence, and resistance to therapy [39]. Chan et al. first identified BCSCs in 2009 by isolating a CD44+CK5+CK20- subpopulation with stem-like traits. In the same study, a unique gene expression signature was identified from this tumor-initiating cell (T-IC) population that could differentiate between MIBC and NMIBC and in addition was able to predict shorter disease recurrence and progression times in certain NMIBC patients, highlighting its potential as a tool with clinical utility [40].

Subsequent research has identified an expanded panel of biomarkers for BCSCs, including Sox4, Bmi1, OCT4, CD133, ALDH1, SOX2 and SSEA-4 [41,42,43,44]. These markers correlate with several stem-like properties and their presence may be linked to the biological aggressiveness of the disease, potentially serving as a prognostic indicator [45,46]. For example, Chiu et al. identified the stem cell factor SOX2 as a prognostic marker for bladder cancer associated with reduced recurrence-free survival and advanced tumor grade [47]. These findings align with those of Ruan et al., who demonstrated that in bladder cancer patients with stage T1 disease, high SOX2 expression was associated with significantly lower recurrence-free survival than low SOX2 expression (p = 0.0002) [48]. In an immunohistochemical analysis of 227 bladder cancer tissues, Xu et al. revealed that the stem cell marker ALDH1 was significantly upregulated in tumors compared to adjacent normal tissue. In NMIBC, ALDH1 protein expression was associated with adverse clinicopathological features, including higher tumor grade and frequent tumor recurrence (p ≤ 0.05), whereas higher expression in MIBC cases was correlated with an advanced tumor grade and stage, as well as lymph node and distant metastases (p ≤ 0.05). Multivariate analysis showed that high ALDH1 expression could be used as a predictor of shorter relapse-free survival in NMIBC patients and poorer overall survival in invasive cancer patients [49].

5. The Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Bladder Cancer

While the identification of BCSCs offers a cellular explanation for tumor recurrence and therapeutic failure, understanding the molecular machinery driving these phenotypes requires a broader look at gene regulation. In this context, ncRNAs have emerged as a fundamental layer of complexity, playing a decisive role in the pathogenesis and progression of bladder cancer through multiple mechanisms, including regulation of fundamental cellular processes such as cell growth, differentiation, and the establishment of cellular identity [50]. Involvement in modulating gene expression and cellular behavior suggests that they may facilitate the spread of cancer cells to distant sites, contributing to disease progression and metastasis [51].

Numerous miRNAs have been identified in bladder cancer, along with their corresponding molecular targets [52,53]. The differential expression of these miRNAs plays a significant role not only in regulating the development of bladder cancer but also in influencing various clinical and pathological characteristics associated with the disease [53]. There is also evidence that miRNAs could serve as potential tools with clinical applications. For instance, a study found that the ratio of miR126 to miR152 in urine samples from bladder cancer patients may serve as an effective diagnostic biomarker. This approach enabled detection of bladder cancer with a specificity of 82% and a sensitivity of 72% [54]. In a different study of miRNA expression in bladder cancer cell lines and patient samples, several miRNAs with differential expression between normal and cancerous were identified. The results suggested that these miRNAs, particularly those with prognostic potential like miR-129, miR-133b, and miR-518c*, could serve as a basis for developing new biomarkers for bladder cancer detection and progression [55].

There is a growing body of evidence highlighting the involvement of various lncRNAs in bladder cancer pathogenesis. Altered expression of these lncRNAs has been associated with multiple aspects of bladder cancer development and progression [56]. For example, in a study by Lv et al., the lncRNA H19 was identified as a critical oncogenic driver in bladder cancer. Mechanistically, H19 acts as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA), binding miR-29b-3p and preventing it from inhibiting DNMT3B, thus promoting bladder cancer progression through EMT [57].

Different studies have delved into the potential clinical application of lncRNA in patients with bladder cancer. Xue et al. reported that the expression levels of exosomal lncRNA-UCA1 were significantly higher in the serum of bladder cancer patients compared to healthy individuals, proposing its potential role as a biomarker for this type of tumor [58]. In another study, the lncRNA LINC02446 was found to be significantly downregulated in cancerous tissues compared to non-cancerous tissues. Reduced LINC02446 expression was associated with higher proliferation, migration, and invasion of bladder cancer cells. In addition, Western blot assay demonstrated a positive correlation between LINC02446 and E-cadherin but an inverse correlation with N-cadherin and Vimentin. Collectively, these findings indicate that LINC02446 could act as a tumor suppressor and as a negative modulator of EMT. Further investigations revealed that LINC02446 interacts with the EIF3G protein, regulating its stability and subsequently inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway, suggesting that LINC02446 could be a promising therapeutic target for bladder cancer [59].

6. The Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Bladder Cancer Stem Cells

Emerging research has increasingly positioned the interaction between ncRNAs and cancer stem cells as a central crossroads in bladder cancer regulation. This complex molecular network represents a critical regulatory layer where genetic and epigenetic mechanisms converge to drive tumor progression. To illustrate the functional significance of this interplay, the following sections examine key studies that have mechanistically characterized the impact of specific ncRNAs on bladder cancer stem cell biology.

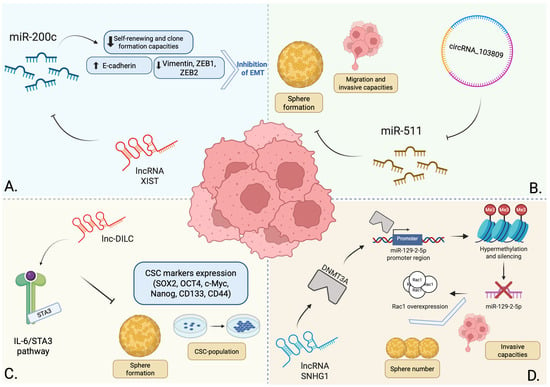

Xu et al. investigated the functional interplay between miR-200c, which is downregulated in various cancers, and its complementary lncRNA XIST, both of which have been implicated in cancer, demonstrating an inverse correlation between their expression in malignant tissues [60]. BCSC-like cells were isolated from the human bladder cancer cell lines 5637 and T24. These cells were confirmed to have stemness properties via Western blotting, which showed high expression of the markers CD44, CD133, OCT-4, KLF4, and ABCG2. Using these confirmed BCSC models, the researchers investigated the effects of miR-200c overexpression and XIST knockdown on cell functions. Their findings demonstrated that both interventions significantly suppressed the self-renewal and clonal expansion capabilities of the BCSC-like cells, implying a role for miR-200c as a tumor suppressor, whereas lncRNA XIST could promote these properties. Furthermore, this study revealed that miR-200c overexpression and XIST knockdown upregulated the expression of E-cadherin and downregulated the expression of vimentin, ZEB1, and ZEB2. These changes indicate that both interventions inhibit EMT in BCSCs. A dual-luciferase reporter assay provided mechanistic evidence, confirming that XIST directly binds to miR-200c and functions as a molecular sponge, thereby regulating its biological effects within cancer cells [60].

Tao et al. conducted a transcriptome microarray analysis to compare BCSCs with their non-stem counterparts, using cells isolated from three patient specimens. This comparison identified distinct expression profiles, revealing 2849 mRNAs, 2698 lncRNAs, and 127 circRNAs with significant differential expression (p < 0.05, fold change > 2.0). Functional validation centered on circRNA_103809, the most highly upregulated circRNA in the BCSC population, and demonstrated that knockdown of circRNA_103809 significantly inhibited oncosphere formation, migration, and invasive capacities. Mechanistically, pull-down assays confirmed that circRNA_103809 functions as a molecular sponge for miR-511, suggesting that it promotes bladder cancer progression by modulating the activity of this molecule [61].

A different study examined the function of lnc-DILC in bladder cancer [62]. This molecule has been established as a tumor suppressor in liver and colorectal cancer through regulation of the IL-6/STAT3 axis [63,64]. Functional assays performed in vitro concluded that overexpression of lnc-DILC suppressed cell proliferation and colony formation capacity and significantly impaired the migratory and invasive potential of bladder cancer cells, supporting its role as a tumor suppressor in bladder cancer. The tumor-suppressive effects of lnc-DILC were found to be mediated through inhibition of the IL-6/STAT3 pathway, as validated by experiments using the STAT3 inhibitor S3I-201. Regarding BCSCs, lnc-DILC expression was found to be significantly downregulated in self-renewing bladder cancer spheroids compared to their adherent counterparts, with its expression progressively decreasing through serial passages. Consistent with these findings, lnc-DILC levels were also significantly reduced in cells sorted for the established BCSC markers CD44 and CD133. Functional studies demonstrated that stable overexpression of lnc-DILC markedly impaired the self-renewal capacity of bladder cancer cells, leading to fewer spheroids formed and a dramatically decreased CSC population as measured by limiting dilution assay. In addition, lnc-DILC overexpression suppressed the expression of key stemness-associated transcription factors and CSC markers such as SOX2, OCT4, c-Myc, Nanog, CD133, and CD44. Taken together, these results demonstrate that lnc-DILC functions as a negative regulator of BCSC expansion and maintenance [62].

In another study, bladder cancer cell lines were transfected with a plasmid encoding the lncRNA SNHG1 to evaluate its effect on their ability to form stem-cell-like spheres. Compared to the control group, the transfected cells formed nearly six times more spheres and demonstrated increased invasive capacity. Conversely, knockdown of SNHG1 reversed these properties and reduced sphere formation in the control group. Further investigation indicated that SNHG1-driven tumorigenesis was promoted through the overexpression of Rac1, a protein implicated in cancer cell stemness and invasion. RAC1 is overexpressed in MIBC, and higher expression correlates with poor survival. Mechanistically, SNHG1 binds to DNMT3A, translocating it to the promoter region of miR-129-2-5p. This leads to the hypermethylation and silencing of miR-129-2-5p. The subsequent decrease in miR-129-2-5p expression stabilizes Rac1 mRNA, increasing Rac1 protein levels and promoting cancer cell sphere formation and invasion [65].

In summary, the presented evidence establishes that ncRNAs form a complex regulatory network that is central to the biology of BCSCs, implicating the role of these molecules as a promising class of targets for novel therapeutic interventions. Figure 1 summarizes the main findings previously described. However, these examples demonstrate some important restraints. A significant limitation shared by three of these studies is the predominant reliance on in vitro models. For instance, Xu et al. employed human bladder cancer cell lines 5637 and T24 as the primary platforms for their experiments. While immortalized cell lines are invaluable tools regarding reproducibility and material generation, valid concerns remain regarding their genomic and phenotypic fidelity to the original tumors they are intended to model [66,67].

Figure 1.

Summary of the provided examples regarding the regulatory role of ncRNAs in BCSCs. The lncRNA XIST acts as a molecular sponge for miR-200c, a tumor-suppressing miRNA that is frequently downregulated in various tumors. Through miR-200c inhibition, XIST promotes stem-like properties and EMT (A) [60]. CircRNA_103809 was found to be upregulated in BCSCs, acting as a molecular sponge for miR-511, another tumor-suppressing miRNA that inhibits sphere formation and reduces the migration and invasive capacities of these cells (B) [61]. Lnc-DILC modulates the IL-6/STAT3 pathway, acting as a negative regulator of BCSCs by inhibiting sphere formation, reducing the CSC population and suppressing the expression of key stemness-associated factors (C) [62]. The lncRNA SNHG1 recruits DNMT3A to the promoter region of miR-129-2-5p, leading to its hypermethylation and silencing. The resulting decrease in miR-129-2-5p levels leads to an amplified Rac1 protein level, increasing the number of formed spheres and promoting the invasive capacity of BCSCs (D) [65]. Created in BioRender. Georgiou, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jol1go7.

Conversely, Tao et al. employed patient-derived specimens, enabling a more accurate preservation of original tumor heterogeneity. Yet, this study relied on a cohort of only three patients [61]. Although typical for resource-intensive microarray screens, such a limited sample size significantly reduces statistical power. Consequently, the impact of inter-patient variability is amplified, creating a risk that individual heterogeneity may skew findings and obscure true, universally applicable biomarkers.

7. Conclusions

Despite significant advancements in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying bladder cancer, the disease remains a major clinical challenge. A major limitation is the lack of robust biomarkers. FDA-approved assays such as the Nuclear Matrix Protein 22 (NMP22) and Bladder Tumor Antigen (BTA) [68,69] have limited clinical application due to performance constraints, including variable sensitivity and specificity among different patient populations [70] or compromised results associated with hematuria and benign inflammatory conditions [71,72]. Consequently, invasive cystoscopy remains the gold standard, imposing a significant patient and economic burden and highlighting the imperative need for reliable, non-invasive alternatives [73]. Recent studies have demonstrated promising candidates, such as Loss of the Y chromosome (LoY), which is linked to impaired immune response and adverse outcomes in male patients [74]. Similarly, the presurgical Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) has been identified as a potential prognostic marker, correlating with aggressive tumor characteristics and reduced relapse-free survival [75].

CSCs have emerged as a pivotal area of investigation due to their central role in tumor maintenance and chemoresistance. Their molecular signatures could serve as highly relevant biomarkers as well as potent therapeutic targets. Throughout this review, we have presented current evidence implicating the role of ncRNAs in governing the fundamental properties of CSCs. This ncRNA-CSC axis represents a critical regulatory crossroads where the molecular drivers of tumor initiation and relapse intersect. However, significant challenges remain on the path to clinical translation. The complexity and redundancy of ncRNA networks, potential off-target effects, and the critical need for efficient and targeted delivery systems must be systematically addressed. Elucidating the underlying molecular mechanisms could demonstrate profound clinical implications, potentially leading to the emergence of new, sensitive biomarkers and more promising therapeutic targets.

Author Contributions

A.G. and D.T. made equal contributions to the conceptualization and preparation of the manuscript. M.G. assisted with manuscript editing. V.Z. supervised the research and offered support during the writing process. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Google Gemini 3 Pro, OpenAI’s ChatGPT GPT-5.1, and Microsoft Copilot (Microsoft 365) for the purposes of language editing and improving readability. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABCs | ATP-binding cassettes |

| AML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| BCSC | Bladder Cancer Stem Cell |

| BTA | Bladder Tumor Antigen |

| ceRNA | Competing Endogenous RNA |

| circRNA | Circular RNA |

| CSC | Cancer Stem Cell |

| CTC | Circulating Tumor Cell |

| DNMT3A | DNA Methyltransferase 3 Alpha |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition |

| ENCODE | Encyclopedia of DNA Elements |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| GSC | Glioma Stem Cell |

| HIF-1a | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha |

| lncRNA | Long Non-coding RNA |

| LoY | Loss of the Y |

| MDR | Multidrug Resistance |

| MIBC | Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| ncRNA | Non-coding RNA |

| NMIBC | Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer |

| NMP22 | Nuclear Matrix Protein 22 |

| NSE | Neuron-Specific Enolase |

| SIRI | Systemic Inflammation Response Index |

| sncRNA | Small Non-coding RNA |

| T-IC | Tumor-Initiating Cell |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Bellmunt, J.; Comperat, E.; De Santis, M.; Huddart, R.; Loriot, Y.; Necchi, A.; Valderrama, B.P.; Ravaud, A.; Shariat, S.F.; et al. Bladder Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Beltran, A.; Cookson, M.S.; Guercio, B.J.; Cheng, L. Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment of Bladder Cancer. BMJ 2024, 384, e076743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Han, J.H.; Jeong, C.W.; Kim, H.H.; Kwak, C.; Yuk, H.D.; Ku, J.H. Clinical Determinants of Recurrence in PTa Bladder Cancer Following Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xiao, J.; Zou, J.; He, Z. Recurrence and Prevention Strategies for Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Asian J. Urol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Tian, W.; Ning, J.; Xiao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhai, Z.; Tanzhu, G.; Yang, J.; Zhou, R. Cancer Stem Cells: Advances in Knowledge and Implications for Cancer Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, B.; Park, J.; Park, S.; Yoo, G.; Yum, S.; Kang, W.; Lee, J.-M.; Youn, H.; Youn, B. Cancer Stem Cells: Landscape, Challenges and Emerging Therapeutic Innovations. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T.P.; Subramanian, S.; Supriya, M.H. A Brief Review of Noncoding RNA. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet. 2024, 25, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ENCODE Project Consortium. An Integrated Encyclopedia of DNA Elements in the Human Genome. Nature 2012, 489, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Samuels, D.; Zhao, S.; Xiang, Y.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Guo, Y. Current Research on Non-Coding Ribonucleic Acid (RNA). Genes 2017, 8, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.N.; Belli, A.; Di Pietro, V. Small Non-Coding RNAs: New Class of Biomarkers and Potential Therapeutic Targets in Neurodegenerative Disease. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.-Q. Structure, Regulation, and Function of Linear and Circular Long Non-Coding RNAs. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, L.S.; Andersen, M.S.; Stagsted, L.V.W.; Ebbesen, K.K.; Hansen, T.B.; Kjems, J. The Biogenesis, Biology and Characterization of Circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, A.C. Circular RNAs Act as MiRNA Sponges. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1087, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, D.; Dick, J.E. Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia Is Organized as a Hierarchy That Originates from a Primitive Hematopoietic Cell. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatova, T.N.; Kukekov, V.G.; Laywell, E.D.; Suslov, O.N.; Vrionis, F.D.; Steindler, D.A. Human Cortical Glial Tumors Contain Neural Stem-like Cells Expressing Astroglial and Neuronal Markers In Vitro. Glia 2002, 39, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajj, M.; Wicha, M.S.; Benito-Hernandez, A.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F. Prospective Identification of Tumorigenic Breast Cancer Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 3983–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.; Diaz, E.; Reya, T. Stem Cells in Cancer Initiation and Progression. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e201911053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetti, C.; Levy, D. Role of Symmetric and Asymmetric Division of Stem Cells in Developing Drug Resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16766–16771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Kong, J.; Brat, D.J. Cancer Stem Cell Division: When the Rules of Asymmetry Are Broken. Stem Cells Dev. 2015, 24, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Hu, H.; Chang, R.; Zhong, J.; Knabel, M.; O’Meally, R.; Cole, R.N.; Pandey, A.; Semenza, G.L. Pyruvate Kinase M2 Is a PHD3-Stimulated Coactivator for Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1. Cell 2011, 145, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, C.; Becker, S.A.; Hurst, K.; Nogueira, L.M.; Findlay, V.J.; Camp, E.R. MiR-145 Antagonizes SNAI1-Mediated Stemness and Radiation Resistance in Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.; Prat, A.; Sedic, M.; Proia, T.; Wronski, A.; Mazumdar, S.; Skibinski, A.; Shirley, S.H.; Perou, C.M.; Gill, G.; et al. Cell-State Transitions Regulated by SLUG Are Critical for Tissue Regeneration and Tumor Initiation. Stem Cell Rep. 2014, 2, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Cai, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.J.; Yuan, L.; Ouyang, G. Twist2 Contributes to Breast Cancer Progression by Promoting an Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Stem-like Cell Self-Renewal. Oncogene 2011, 30, 4707–4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.A.; Guo, W.; Liao, M.-J.; Eaton, E.N.; Ayyanan, A.; Zhou, A.Y.; Brooks, M.; Reinhard, F.; Zhang, C.C.; Shipitsin, M.; et al. The Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Generates Cells with Properties of Stem Cells. Cell 2008, 133, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.-H.; Imrali, A.; Heeschen, C. Circulating Cancer Stem Cells: The Importance to Select. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 27, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Dong, J.; Haiech, J.; Kilhoffer, M.-C.; Zeniou, M. Cancer Stem Cell Quiescence and Plasticity as Major Challenges in Cancer Therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 1740936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.; Dorsey, J.F.; Fan, Y. Cell Plasticity, Senescence, and Quiescence in Cancer Stem Cells: Biological and Therapeutic Implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 231, 107985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, R.; Telleria, C.M. Cancer Cell Repopulation After Therapy: Which Is the Mechanism? Oncoscience 2023, 10, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlush, L.I.; Zandi, S.; Mitchell, A.; Chen, W.C.; Brandwein, J.M.; Gupta, V.; Kennedy, J.A.; Schimmer, A.D.; Schuh, A.C.; Yee, K.W.; et al. Identification of Pre-Leukaemic Haematopoietic Stem Cells in Acute Leukaemia. Nature 2014, 506, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffinger, B.; Tobias, A.L.; Han, Y.; Lee, G.; Guo, D.; Dey, M.; Lesniak, M.S.; Ahmed, A.U. Conversion of Differentiated Cancer Cells into Cancer Stem-Like Cells in a Glioblastoma Model After Primary Chemotherapy. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyak, K.; Weinberg, R.A. Transitions Between Epithelial and Mesenchymal States: Acquisition of Malignant and Stem Cell Traits. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, P.A.; Bert, A.G.; Paterson, E.L.; Barry, S.C.; Tsykin, A.; Farshid, G.; Vadas, M.A.; Khew-Goodall, Y.; Goodall, G.J. The MiR-200 Family and MiR-205 Regulate Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition by Targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-M.; Gaur, A.B.; Lengyel, E.; Peter, M.E. The MiR-200 Family Determines the Epithelial Phenotype of Cancer Cells by Targeting the E-Cadherin Repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes. Dev. 2008, 22, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisi, A.; Cho, W.; Locatelli, F.; Fruci, D. Multidrug Resistance and Cancer Stem Cells in Neuroblastoma and Hepatoblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 24706–24725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.-L.; Huang, R.-L.; Shay, J.; Chen, L.-Y.; Lin, S.-J.; Yan, P.S.; Chao, W.-T.; Lai, Y.-H.; Lai, Y.-L.; Chao, T.-K.; et al. Hypermethylation of the TGF-β Target, ABCA1 Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Ovarian Cancer Patients. Clin. Epigenet. 2015, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, N.Y.; Schatton, T.; Kim, S.; Zhan, Q.; Wilson, B.J.; Ma, J.; Saab, K.R.; Osherov, V.; Widlund, H.R.; Gasser, M.; et al. VEGFR-1 Expressed by Malignant Melanoma-Initiating Cells Is Required for Tumor Growth. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 1474–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleau, A.-M.; Hambardzumyan, D.; Ozawa, T.; Fomchenko, E.I.; Huse, J.T.; Brennan, C.W.; Holland, E.C. PTEN/PI3K/Akt Pathway Regulates the Side Population Phenotype and ABCG2 Activity in Glioma Tumor Stem-Like Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Xu, S.; Li, C.; Jin, X. The Origin and Evolution of Bladder Cancer Stem Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 950241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.S.; Espinosa, I.; Chao, M.; Wong, D.; Ailles, L.; Diehn, M.; Gill, H.; Presti, J.; Chang, H.Y.; van de Rijn, M.; et al. Identification, Molecular Characterization, Clinical Prognosis, and Therapeutic Targeting of Human Bladder Tumor-Initiating Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14016–14021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Blijlevens, M.; Yang, N.; Frangou, C.; Wilson, K.E.; Xu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Morrison, C.D.; Shepherd, L.; et al. Sox4 Expression Confers Bladder Cancer Stem Cell Properties and Predicts for Poor Patient Outcome. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 11, 1363–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Wan, X.; Huang, H.; Chen, X.; Liang, W.; Zhao, F.; Lin, T.; Han, J.; Xie, W. Knockdown of Bmi1 Inhibits the Stemness Properties and Tumorigenicity of Human Bladder Cancer Stem Cell-like Side Population Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 31, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedaghat, S.; Gheytanchi, E.; Asgari, M.; Roudi, R.; Keymoosi, H.; Madjd, Z. Expression of Cancer Stem Cell Markers OCT4 and CD133 in Transitional Cell Carcinomas. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2017, 25, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomqvist, M.; Koskinen, I.; Löyttyniemi, E.; Mirtti, T.; Boström, P.J.; Taimen, P. Prognostic and Predictive Value of ALDH1, SOX2 and SSEA-4 in Bladder Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, K.; Jin, Z.; Yan, P.; Wei, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, M.; Guo, X.; Xing, Q.; Zhang, H.; et al. Recent Advances in Bladder Cancer Stem Cells (BCSCs): A Descriptive Review of Emerging Therapeutic Targets. iScience 2025, 28, 112720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.R.A.H.; Syadza, Y.Z.; Yausep, O.E.; Christanto, R.B.I.; Muharia, B.H.R.; Mochtar, C.A. The Expression of Stem Cells Markers and Its Effects on the Propensity for Recurrence and Metastasis in Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0269214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-F.; Wu, C.-C.; Kuo, M.-H.; Miao, C.-C.; Zheng, M.-Y.; Chen, P.-Y.; Lin, S.-C.; Chang, J.-L.; Wang, Y.-H.; Chou, Y.-T. Critical Role of SOX2-IGF2 Signaling in Aggressiveness of Bladder Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Wei, B.; Xu, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, M.; Liang, J.; Jin, K.; Huang, X.; Lu, P.; et al. Predictive Value of Sox2 Expression in Transurethral Resection Specimens in Patients with T1 Bladder Cancer. Med. Oncol. 2013, 30, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Shao, M.-M.; Zhang, H.-T.; Jin, M.-S.; Dong, Y.; Ou, R.-J.; Wang, H.-M.; Shi, A.-P. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) Expression Is Associated with a Poor Prognosis of Bladder Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015, 39, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Bu, P. Non-Coding RNA in Cancer. Essays Biochem. 2021, 65, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, E.A.; Brown, C.J.; Lam, W.L. The Functional Role of Long Non-Coding RNA in Human Carcinomas. Mol. Cancer 2011, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Gao, F.; Hu, X.; Zhou, L.; Chen, J.; Luo, H.; Sun, J.; Wu, S.; Han, Y.; et al. A Systematic Analysis on DNA Methylation and the Expression of Both MRNA and MicroRNA in Bladder Cancer. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, G.; Guo, X.; Yao, H.; Wang, G.; Li, C. Non-Coding RNA in Bladder Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020, 485, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanke, M.; Hoefig, K.; Merz, H.; Feller, A.C.; Kausch, I.; Jocham, D.; Warnecke, J.M.; Sczakiel, G. A Robust Methodology to Study Urine MicroRNA as Tumor Marker: MicroRNA-126 and MicroRNA-182 Are Related to Urinary Bladder Cancer. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2010, 28, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrskjøt, L.; Ostenfeld, M.S.; Bramsen, J.B.; Silahtaroglu, A.N.; Lamy, P.; Ramanathan, R.; Fristrup, N.; Jensen, J.L.; Andersen, C.L.; Zieger, K.; et al. Genomic Profiling of MicroRNAs in Bladder Cancer: MiR-129 Is Associated with Poor Outcome and Promotes Cell Death In Vitro. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 4851–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Lin, J.; Jin, X. Biological Functions and Clinical Significance of Long Noncoding RNAs in Bladder Cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Zhong, Z.; Huang, M.; Tian, Q.; Jiang, R.; Chen, J. LncRNA H19 Regulates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Metastasis of Bladder Cancer by MiR-29b-3p as Competing Endogenous RNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864, 1887–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Chen, W.; Xiang, A.; Wang, R.; Chen, H.; Pan, J.; Pang, H.; An, H.; Wang, X.; Hou, H.; et al. Hypoxic Exosomes Facilitate Bladder Tumor Growth and Development Through Transferring Long Non-Coding RNA-UCA1. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W.; Dong, X.; Xin, P.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Jing, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, C.; et al. Long Non-Coding RNA LINC02446 Suppresses the Proliferation and Metastasis of Bladder Cancer Cells by Binding with EIF3G and Regulating the MTOR Signalling Pathway. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021, 28, 1376–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhu, X.; Chen, F.; Huang, C.; Ai, K.; Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, X. LncRNA XIST/MiR-200c Regulates the Stemness Properties and Tumourigenicity of Human Bladder Cancer Stem Cell-like Cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2018, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Yuan, S.; Liu, J.; Shi, D.; Peng, M.; Li, C.; Wu, S. Cancer Stem Cell-Specific Expression Profiles Reveal Emerging Bladder Cancer Biomarkers and Identify CircRNA_103809 as an Important Regulator in Bladder Cancer. Aging 2020, 12, 3354–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.-Y.; Li, S.-Y.; Li, X.-Z.; Zhou, T.-F.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Liu, F.-L.; Yu, X.-N.; Lin, J.; Chen, F.-Y.; Cao, J.; et al. Long Non-Coding RNA DILC Suppresses Bladder Cancer Cells Progression. Gene 2019, 710, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Sun, W.; Shen, W.; Xia, M.; Chen, C.; Xiang, D.; Ning, B.; Cui, X.; Li, H.; Li, X.; et al. Long Non-Coding RNA DILC Regulates Liver Cancer Stem Cells via IL-6/STAT3 Axis. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.-Q.; Xing, X.-L.; Cai, H.; Si, A.-F.; Hu, X.-R.; Ma, Q.-Y.; Zheng, M.-L.; Wang, R.-Y.; Li, H.-Y.; Zhang, X.-P. Long Non-Coding RNA DILC Suppresses Cell Proliferation and Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. Gene 2018, 666, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yang, R.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Cohen, M.; Simeone, D.M.; Costa, M.; Wu, X.-R. DNMT3A/MiR-129-2-5p/Rac1 Is an Effector Pathway for SNHG1 to Drive Stem-Cell-Like and Invasive Behaviors of Advanced Bladder Cancer Cells. Cancers 2022, 14, 4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipiya, V.V.; Gilazieva, Z.E.; Issa, S.S.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Solovyeva, V.V. Comparison of Primary and Passaged Tumor Cell Cultures and Their Application in Personalized Medicine. Explor. Target. Antitumor Ther. 2024, 5, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsvik, A.; Stieber, D.; Enger, P.Ø.; Golebiewska, A.; Molven, A.; Svendsen, A.; Westermark, B.; Niclou, S.P.; Olsen, T.K.; Chekenya Enger, M.; et al. U-251 Revisited: Genetic Drift and Phenotypic Consequences of Long-Term Cultures of Glioblastoma Cells. Cancer Med. 2014, 3, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewski, D.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Czech, S.; Szpara, J.; Aebisher, D. Bladder Cancer Biomarkers. Explor. Target. Antitumor Ther. 2025, 6, 1002301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Monar, G.V.; Reynolds, T.; Gordon, M.; Moon, D.; Moon, C. Molecular Markers for Bladder Cancer Screening: An Insight into Bladder Cancer and FDA-Approved Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heard, J.R.; Mitra, A.P. Noninvasive Tests for Bladder Cancer Detection and Surveillance: A Systematic Review of Commercially Available Assays. Bladder Cancer 2024, 10, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokeshwar, V.B.; Habuchi, T.; Grossman, H.B.; Murphy, W.M.; Hautmann, S.H.; Hemstreet, G.P.; Bono, A.V.; Getzenberg, R.H.; Goebell, P.; Schmitz-Dräger, B.J.; et al. Bladder Tumor Markers beyond Cytology: International Consensus Panel on Bladder Tumor Markers. Urology 2005, 66, 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Zippe, C.D.; Pandrangi, L.; Nelson, D.; Agarwal, A. Exclusion Criteria Enhance the Specificity and Positive Predictive Value of NMP22 and BTA Stat. J. Urol. 1999, 162, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyaert, M.; Van Praet, C.; Delrue, C.; Speeckaert, M.M. Novel Urinary Biomarkers for the Detection of Bladder Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Bizzarri, F.P.; Filomena, G.B.; Marino, F.; Iacovelli, R.; Ciccarese, C.; Boccuto, L.; Ragonese, M.; Gavi, F.; Rossi, F.; et al. Relationship Between Loss of Y Chromosome and Urologic Cancers: New Future Perspectives. Cancers 2024, 16, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Foschi, N.; Palermo, G.; Maioriello, G.; Lentini, N.; Iacovelli, R.; Ciccarese, C.; Ragonese, M.; Marino, F.; Bizzarri, F.P.; et al. SIRI as a Biomarker for Bladder Neoplasm: Utilizing Decision Curve Analysis to Evaluate Clinical Net Benefit. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2025, 43, 393.e1–393.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).