Abstract

Background: Spontaneous regression of testicular cancer with retroperitoneal metastasis is a rare phenomenon and poses challenges in its diagnosis. Methods: A 33-year-old male patient presented with severe lower back pain (10/10) of 4 months’ duration, radiating to the left lower limb, refractory to NSAIDs, and significantly impaired ambulation, accompanied by nausea and vomiting. In addition to difficulty initiating urination and defecation, with weight loss of 30 kg, he was referred to the urology service of our hospital. Results: On physical examination, the left testicle showed signs of varicocele without pain. Therefore, laboratory and imaging studies were requested, highlighting elevated β-hCG (156.4 mIU/mL) and LDH (850 IU/L). Testicular ultrasound confirmed the diagnosis of left varicocele, while computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a conglomerated retroperitoneal mass of more than 5 cm, located in the paravertebral, retrocural, paraaortic, and intercavoaortic regions. Based on these findings, primary treatment with left radical orchiectomy was chosen, which showed regression of the seminomatous tumor. Histopathological examination revealed a seminomatous germ cell tumor (pT0, pN3, M0), clinical stage IIC, with a good prognosis. Therefore, chemotherapy was initiated with four cycles of EP (etoposide 170 mg and cisplatin 35 mg). However, despite standard chemotherapy, the disease progressed until the patient died. Conclusions: Cases of testicular tumor with retroperitoneal metastasis are rare and infrequently present with clinical, testicular, and imaging findings. Therefore, histopathology, accompanied by the intentional identification of mutations associated with the TP53 gene when therapeutic failure exists.

1. Introduction

Germ Cell Tumors (GCTs) are the most common form of neoplasia and account for 95% of testicular cancer in men aged 15–40 years [1]. According to their histology, they are classified as seminomas (30–40%) which includes classic seminoma, and non-seminomatous neoplasm (60–70%) [2] including embryonal carcinoma, teratoma (mature or immature), yolk sac carcinoma and choriocarcinoma [3]. While, according to the site of origin, it can be gonadal, which represents around 95% of cases, or extragonadal (EGCT) in 5% [4].

There is doubt that they exist as a single disease and are only metastases from a primary occult testicular tumor [5]. This concept is known as “burned tumor” which was first reported by Prym [6] as an extragonadal retroperitoneal germ cell tumor with testicular scar after the autopsy. Subsequently, Azzopardi [7] reported a series of cases where the histopathological study revealed the presence of scars and tumor foci, even though during the physical examination the testicles showed no abnormality. Furthermore, Balzer [8] identified that seminoma is the most common histological type in metastasis sites, these being the mediastinum, followed by the pineal gland and retroperitoneum [9].

The theory that exists to explain the mechanism by which there is primary tumor regression is that of tumor cell destruction in the testicle due to the activity of the immune system. Where host cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize antigens from cancer cells and destroy them, replacing the primary tumor with fibrosis. There may also be ischemia, caused by the high metabolic rate of the tumor that exceeds its blood supply, having the presence of testicular atrophy associated with scarring, reduced spermatogenesis, necrosis and calcifications [10]. Thus, spontaneous regression of cancer is recognized as a rare phenomenon in tumors [4].

According to Iannantuono et al. [4], the main initial symptoms of this rare clinical form are abdominal pain and back pain. Weight loss, gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, epigastric pain, melena, hematemesis, and loss of appetite are also identified. Specifically, only 7.8% of patients report testicular symptoms such as scrotal swelling, a palpable mass, or pain; occasionally, fever and night sweats have been described. Thus, the condition is not very specific and requires a complex diagnosis. However, imaging (ultrasound) and histopathological diagnosis are vitally important in the management of these patients when a diagnosis is suspected [4].

Therefore, we present the case of a man with no apparent clinical testicular findings and a diagnosis of retroperitoneal metastasis from a primary testicular seminoma with spontaneous regression and unfavorable progressive course.

2. Case Presentation

A 33-year-old male patient was referred in January 2023 for evaluation of a left varicocele. During the medical history, the patient reported severe low back pain (10/10) on the visual analogue scale, which had been present for 4 months, radiating to the left pelvic extremity. The pain was refractory to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and significantly limited walking. The pain was accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and difficulty initiating and defecating. The patient also reported an unintentional weight loss of 30 kg over three months and hyporexia.

Physical examination revealed both testes in the scrotal sac, with no enlargement. The left testicle showed a clinically painless varicocele. Testicular ultrasound and extension studies were therefore requested. The varicocele was interpreted as secondary to extrinsic compression of the left gonadal vein by a retroperitoneal conglomerate. Testicular ultrasound identified heterogeneous parenchyma with poorly defined and diffuse areas of increased and decreased echogenicity. Likewise, rounded hyperechoic images with a tendency to converge on the posterior wall were observed, as well as diffuse calcifications in the left testicle (Figure 1A,B). These findings were suggestive of microcalcifications and fibrotic changes, consistent with a burned-out or regressed testicular tumor.

Figure 1.

Left testicular ultrasound. (A) Heterogeneous parenchyma with poorly defined and diffuse areas of increased and decreased echogenicity, corresponding to regressive changes. (B) Presence of diffuse intratesticular calcifications (red box), a characteristic finding of a burned-out testicular tumor.

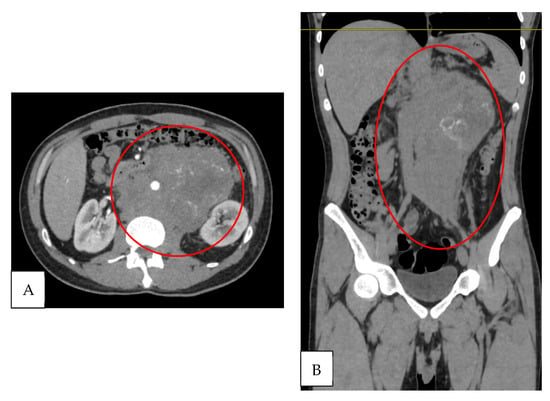

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a conglomerated retroperitoneal mass measuring more than 5 cm, located in the paravertebral, retroclavicular, paraaortic, and intercavoaortic regions. The mass enhanced with contrast administration and caused displacement of adjacent vascular structures, including partial blockage of the abdominal aorta, superior mesenteric artery, and left renal artery (Figure 2A,B). The left testicle was heterogeneous with calcifications. The retroperitoneal mass was interpreted as a massive lymph node metastasis. Therefore, the cause of the clinical left varicocele was considered to be compression of the venous drainage.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced tomography. (A) Axial section: retroperitoneal conglomerate >5 cm with partial encasement of the abdominal aorta and superior mesenteric and left renal arteries (red circle). (B) Coronal section: retroperitoneal conglomerate with involvement of paravertebral, retrocrural, and paraaortic lymphadenopathy, with contrast enhancement (red circle).

On the other hand, laboratory studies showed normal levels of complete blood count, blood chemistry, and alpha-fetoprotein (4.17 ng/mL; normal value: 0.89–8.78 ng/mL). However, a significant elevation of the beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG: 156.4 mIU/mL; normal value: <2 mIU/mL) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH: 850 IU/L; normal value: 125–220 IU/L) was identified (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical laboratory results during patient approach.

Based on imaging and laboratory findings, a diagnosis of probable testicular germ cell neoplasia with retroperitoneal metastasis was established. A left radical orchiectomy was performed in January 2023.

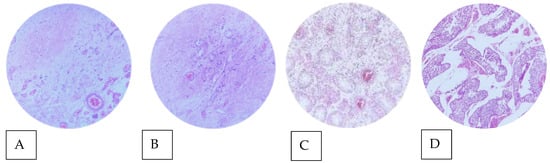

Histopathological examination of the surgical specimen obtained from orchiectomy revealed a central, ill-defined, whitish fibrotic scar in the testicular parenchyma. Microscopic examination showed characteristic findings of spontaneous tumor regression, highlighting acellular collagenous tissue with numerous interspersed small blood vessels, lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, and macrophages. The adjacent testicular parenchyma showed partial atrophy with sclerosis of the seminiferous tubules. In addition, adjacent to the scar area, in situ germ cell neoplasia with a pagetoid pattern was identified. No invasive germ cell tumor or lymphovascular invasion was observed (Figure 3). These findings thus confirmed the diagnosis of a “burned” or regressed testicular tumor.

Figure 3.

Microphotographs of testicular parenchyma (Hematoxylin-Eosin objective 40 × stain). (A) Intratesticular fibrotic scar. (B) Acellular collagenous tissue with numerous interspersed small blood vessels (characteristic of regression). (C) Atrophy and sclerosis of the seminiferous tubules. (D) Germ cell neoplasia in situ (pagetoid stain) adjacent to the scar area.

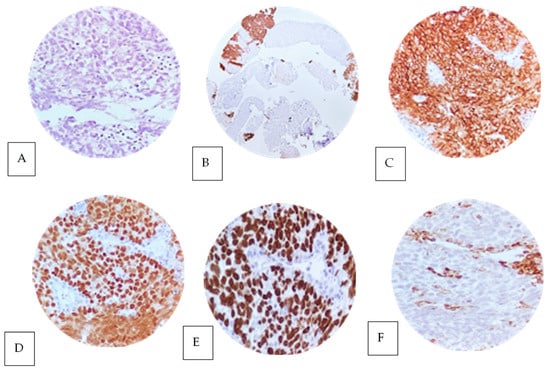

Subsequently, a trucut biopsy of the retroperitoneal conglomerate was performed. Histology showed a germ cell tumor with a solid pattern, composed of uniform cells with well-defined cell membranes, pale cytoplasm, and polygonal nuclei with prominent nucleoli, compatible with pure seminoma (Figure 4A). Immunohistochemistry was essential to confirm the diagnosis, showing intense and diffuse positive staining for PLAP (membranous/cytoplasmic) (Figure 4B,C), and nuclear staining for OCT3/4 (Figure 4D) and SALL4 (Figure 4E) in the neoplastic cells. While, in the differential diagnosis, staining for CD45 was negative in the tumor cells and positive in the peritumoral lymphocytic infiltrate (positive internal control) (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Trucut biopsy of a retroperitoneal conglomerate with histological features of pure seminoma (A) with a solid pattern stained with hematoxylin and eosin (40× objective). The neoplastic cells are uniformly arranged with well-defined cell membranes without nuclear overlay, with pale to slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm, polygonal nuclei and prominent nucleoli. The stroma shows variable lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. The immunophenotype in the neoplastic cells showed positive expression with diffuse membranous and cytoplasmic staining in the neoplastic cells for PLAP (B,C), as well as intense positive nuclear expression in the neoplastic cells for OCT 3/4 (D) and SALL 4 (E). Negative expression for CD45 ACL was found in the neoplastic cells (F). The positive control was reactive in peritumoral stromal lymphocytes. All control samples are positive and adequate.

The patient was subsequently evaluated by medical oncology and chemotherapy was started in March 2023 with 4 cycles of the EP regimen (Etoposide 170 mg and Cisplatin 35 mg), which were completed in May 2023. Additionally, during treatment, he required pain management due to oppressive lower back pain.

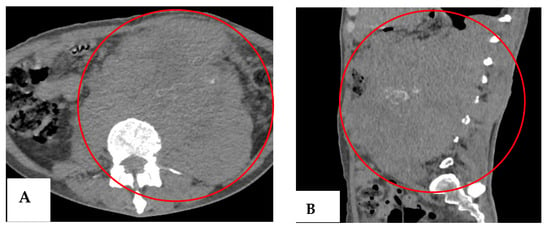

Our patient remained under follow-up by the medical oncology department, so new tumor markers were ordered in July 2023, with elevated LDH (1354 IU/L) and β-hCG (93.56 mIU/mL) (Table 2). Additionally, a CT scan was required, which showed an increase in the size of the cluster (Figure 5), corroborating an unsuccessful therapy, considered progressive disease according to RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) criteria.

Table 2.

Tumor marker results during evaluation and progression at six months.

Figure 5.

Follow-up CT scan (July 2023). (A) Axial section showing an enlarged mass with a larger necrotic component and anterior extension (red circle). (B) Coronal section showing the craniocaudal extension of the mass from T10 to S1 (red oval).

The patient subsequently entered intermediate care in July 2023 for renal failure and urosepsis. Due to the unfavorable outcome, the patient and his family opted for discharge for maximum benefit. The patient’s death was recorded one month later. Table 3 shows the chronology of events for our patient.

Table 3.

Chronology of events during the approach to this case report.

3. Discussion

GCTs are the most common form of testicular cancer in men aged 15–40 years, while tumors of extra-gonadal origin without primary lesion are rare [11]. Most occult or “burned” retroperitoneal germ cell tumors in young adult’s regress spontaneously [12]. In our case, clinical symptoms such as lower back pain, difficulty walking, and the absence of testicular symptoms due to the lack of pain and increased volume did not initially indicate a presumptive diagnosis of evidence of a primary testicular tumor. In particular, the absence of a palpable mass in our patient has been proposed to be due to the present metastasis [13]. Meanwhile, imaging (ultrasound and CT) raised the diagnostic suspicion. Through the performance of orchiectomy, data of tumor regression were evidenced, and the histopathological study was what confirmed the diagnosis.

In the case presented here, the laboratory studies were mostly within normal values; however, elevation of β-hCG (beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin) and LDH (lactic dehydrogenase) was identified, this fact being uncommon, particularly in the case of β-hCG [4,14]. This is probably due to the location of the tumor is the retroperitoneum, where the main tumor marker identified is LDH [4].

The typical histopathological findings of regressing neoplasms are multiple, the most common being matrix with lymphocytic infiltrate, hemosiderin deposits associated with scarring, and atrophy of seminiferous tubules forming “ghost tubules.” In our patient, the testicular scar showed fibrosis, calcifications, and atrophy with residual GCNIS, which is consistent with previous reports of burn tumor. While the less common are angiomatous foci, siderophages and thick intratubular calcifications with psammoma bodies, these are fine onion-skin-shaped calcifications that are observed in atrophic cryptorchid testes and in testicular microlithiasis [8,15]. In contrast to what can be found in histopathology of a primary testicular seminoma, it is clear cytoplasm due to glycogen particles, nuclei with granular chromatin, spaced with flattened edges and lymphocytic infiltrate [16].

Regarding Immunohistochemistry (IHC), it turns out to be of utmost importance to guide individualized treatment, especially SALL4 and PLAP which are common markers of malignant GCTs [17]. The immunophenotype for which the patient was positive highlights the expression of OCT3/4, PLAP, SALL4. According to Preda et al., [18], the expression of OCT3/4 and SALL4 maintains the full potential of stem cells and primordial germ cells.

Although histopathology confirmed the diagnosis, ultrasound showed poorly defined and diffuse areas of higher and lower echogenicity, with some round hyperechogenic images with a tendency to converge on the posterior wall. Abdominal and pelvic tomography reported left testicle heterogeneous in its density with calcifications, paravertebral, retrocrural, and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, which allowed the recognition of the retroperitoneal mass. In this sense, the usefulness of ultrasound has been highlighted in the initial approach to patients with this disease, allowing the identification of specific parenchymal alterations, such as scarring, calcifications, and nodular lesions [13,14,19,20,21,22].

Currently, the treatment of primary seminomatous GCTs is performed in an equivalent manner to that for metastatic GCTs of gonadal origin. In the case of pure seminomas, there is a better prognosis if treated with chemotherapy compared to non-seminomas. This is because seminoma cells are very susceptible to cisplatin-based chemotherapy, regardless of their location [22].

In the case we report here, the disease had a good prognosis, so four cycles of EP were applied, since the standard chemotherapy options should include three cycles of BEP or four cycles of EP [23]. However, in our patient, chemotherapy did not show improvement, resulting in disease progression and poor outcome. Although we could not confirm the reason for therapeutic failure in our patient, therapeutic failures due to mutations in the TP53 gene have been reported [24]. According to Ottaviano [24], drug-resistant GCTs associated with mutations in the TP53 gene cause its function to be inactivated, preventing apoptosis after contact with immune cells, promoting the survival and growth of tumor cells.

Currently, the management of residual retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) following chemotherapy in certain clinical settings has been noted for its excellent results. In this regard, in a study such as that by Perdonà et al. [25], the authors performed orchiectomy followed by adjuvant treatment (chemotherapy) in a 41-year-old man with NSGCT (pT2, UICC stage IB). A unilateral left-sided modified template guided dissection was performed from the aortic bifurcation to the renal hilum, preserving vascular structures. A 3.5 cm residual mass and para-aortic nodes were excised with the help of a flexible Greena® applicator for clips. This approach minimized morbidity and improved patient recovery using a minimally invasive surgical approach. Furthermore, Franzese et al. [26] conducted a study with a larger cohort, in which post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (PC-RPLND) yielded reliable oncological results and the postoperative ejaculatory function of the 33 patients with non-seminomatous germ cell tumor IIA and IIB was acceptable. Thus, this procedure proved to be reliable and technically reproducible. In our case, we considered that the post-chemotherapy residual mass was unresectable, and the patient’s clinical conditions did not allow for it.

There is a question as to whether some extragonadal germ cell tumors are primary or could be the result of metastasis, because spontaneous regression theories suggest that primary testicular GCTs undergo spontaneous regression after metastasis, either due to an immune response or tumor ischemia. Another theory proposes the de novo formation of a primary GCT in extragonadal tissues [1]. In the report we present, the first theory is the most accepted, since in the histopathological report it was shown to have a fibrous scar of a variable lymphoplastic–mocytic infiltrate in most cases of spontaneous regression [4]. It is worth mentioning that the regression phenomenon has also been identified in different histological strains, with pure seminoma being the most common associated with spontaneous regression and as a metastatic strain [15].

4. Conclusions

Cases of testicular tumors with retroperitoneal metastasis are rare and infrequently present with clinical, testicular, and imaging findings. Therefore, histopathology is necessary in suspected cases.

Particularly when chemotherapy treatment results in therapeutic failure, a contributing genetic factor should be considered. Therefore, the deliberate identification of mutations associated with the TP53 gene should be considered. Minimally invasive surgery should also be included to remove the residual mass.

It is important to consider the presence of this type of tumor in patients with laboratory and imaging abnormalities (ultrasound and CT) in order to distinguish testicular tumors among the main differential diagnoses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.O.S. and C.A.C.-F.; methodology, V.O.S., R.P.B., G.G.S., L.T.O., D.G.L., D.G.D.L.T., M.C.C., A.M.C., A.D.C. and C.A.C.-F.; investigation, V.O.S., D.G.L. and C.A.C.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, V.O.S., D.G.L. and C.A.C.-F.; writing—review and editing, V.O.S., D.G.L. and C.A.C.-F.; supervision, C.A.C.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As advancements in non-invasive and invasive surgeries have occurred, the final diagnosis was determined several months after the patient’s first hospital registration. Subsequently, ethical approval was obtained on Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Regional de Alta Especialidad de Ixtapaluca, and the ethic approval code is “NR-078-2024”, dated on 9 September 2024. In 2025, due to the new measures formulated by the hospital’s research ethics committee for the approval and publication of hospital case reports, the ethical approval was re-updated, with the approval code “CC-003-2025” and the date 30 July 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shahrokh, S.; Shahin, M.; Abolhasani, M.; Arefpour, A.M.M.S. Burned—Out Testicular Tumor Presenting as a Retroperitoneal Mass: A Case Report. Cureus 2022, 14, e21603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparella, M.T.; Eusebi, N.; Goteri, G.; Bartelli, F.; Guglielmi, G. Extragonadal germ cell tumor: A rare case in dorsal region. Indian J. Cancer 2024, 61, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, B.A.; Zhang, M.; Pisters, L.L.; Tu, S.M. Systemic therapy for primary and extragonadal germ cell tumors: Prognosis and nuances of treatment. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2020, 9, S56–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannantuono, G.M.; Strigari, L.; Roselli, M.; Torino, F. A scoping review on the “burned out” or “burnt out” testicular cancer: When a rare phenomenon deserves more attention. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 165, 103452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjani, N.; Winquist, E.; Power, N. Do retroperitoneal extragonadal germ cell tumours exist? Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2015, 9, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prym, P. Spontanheilung eines bosartigen, wahrscheinlich chorionephiteliomatosen gewachses im hoden. Virchows Arch. Pathol. Anat. Physiol. Klin. Med. 1927, 265, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, J.G.; Mostofi, F.K.; Theiss, E.A. Lesions of testes observed in certain patients with widespread choriocarcinoma and related tumors. The significance and genesis of hematoxylin-staining bodies in the human testis. Am. J. Pathol. 1961, 38, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Balzer, B.L.; Ulbright, T.M. Spontaneous regression of testicular germ cell tumors: An analysis of 42 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar Bujanda, D.; Pérez Cabrera, D.; Croissier Sánchez, L. Extragonadal Germ Cell Tumors of the Mediastinum and Retroperitoneum. A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-based Study. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 45, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Jara, D.; Saavedra-Verduga, D.; Álvarez-Álvarez, J.; García-Velandria, F. Burnt testicular tumor. Case report. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Médicas 2023, 48, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João Serpa, M.; Franco, S.; Repolho, D.; Branco, F.; Gramaca, J.; Ferreira Júnior, J. An Unusual Case of Primary Retroperitoneal Germ Cell Tumour in a Young Man. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2018, 5, 000900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felici, M.; Gioia Klinger, F.; Campolo, F.; Rita Balistreri, C.; Barchi, M.; Dolci, S. To Be or Not to Be a Germ Cell: The Extragonadal Germ Cell. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, R.; Rochlitz, C.; Sauter, G.; Gasser, T.C. Der “ausgebrannte” Hodentumor: Eine seltene Erscheinungsform der Keimzellneoplasien [“Burned out” testicular tumor: A rare form of germ cell neoplasias]. Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr. 1999, 129, 235–240. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Kontos, S.; Doumanis, G.; Karagianni, M.; Politis, V.; Simaioforidis, V.; Kachrilas, S.; Koritsiadis, S. Burned-out testicular tumor with retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2009, 3, 8705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, J.C.; González, J.; Rodríguez, N.; Hernández, E.; Núñez, C.; Rodríguez-Barbero, J.M. Clinicopathological Study of Regressed Testicular Tumors (Apparent Extragonadal Germ Cell Neoplasms). J. Urol. 2009, 182, 2303–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourne, M.; Radulescu, C.; Allory, Y. Tumeurs germinales du testicule: Caractéristiques histopathologiques es moléculaires. Bull. Cancer 2019, 106, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, W.; Pang, J.; Hu, Y.; Shi, H. Immune-related mechanisms and immunotherapy in extragonadal germ cell tumors. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1145788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, O.; Dulcey, I.; Nogales, F.F. The role of new immunohostochemical markers in malignant germ cell tumours of the gonads. Rev. Esp. Patol. 2012, 45, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Gurioli, A.; Oderda, M.; Vigna, D.; Peraldo, F.; Giona, S.; Soria, F.; Cassenti, A.; Pacchioni, D.; Gontero, P. Two cases of retroperitoneal metastasis from a completely regressed burned-out testicular cancer. Urol. J. 2013, 80, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O.; Hubert, J.; Grignon, Y.; Mangin, P. Séminome testiculaire métastatique spontanément involué (“Burned-out seminoma”). A propos d’un cas révélé par une adénopathie sus-claviculaire [Spontaneously involuting metastatic seminoma of the testis (“burned-out seminoma”). Report of a case presenting with supraclavicular adenopathy]. Prog. Urol. 1996, 6, 278–281. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Sarid, D.L.; Ron, I.G.; Avinoach, I.; Sperber, F.; Inbar, M.J. Spontaneous regression of retroperitoneal metastases from a primary pure anaplastic seminoma: A case report. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 25, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musser, J.E.; Przybycin, C.G.; Russo, P. Regression of metastatic seminoma in a patient referred for carcinoma of unknown primary origin. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2010, 7, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, J.; Seidel, C.; Zengerling, F. Male extragonadal germ cell tumors of the adult. Oncol. Res. Trear 2016, 39, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviano, M.; Giunta, E.F.; Rescigno, P.; Pereira Mestre, R.; Marandino, L.; Tortora, M. The enigmatic Role of TP53 in Germ Cell Tumors: Are we missing something? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdonà, S.; Izzo, A.; Contieri, R.; Passaro, F.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Corrado, R.; Canfora, G.; Damiano, R.; Autorino, R.; Spena, G. Single-Port Robot-Assisted Post-Chemotherapy Unilateral Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection: Feasibility and Surgical Considerations. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2025, 51, e20250091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzese, D.; Tufano, A.; Izzo, A.; Muscariello, R.; Grimaldi, G.; Quarto, G.; Castaldo, L.; Rossetti, S.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Desicato, S.; et al. Unilateral post-chemotherapy robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in Stage II non-seminomatous germ cell tumor: A tertiary care experience. Asian J. Urol. 2023, 10, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).