Abstract

Background: Liver fibrosis drives mortality in chronic liver disease, with effective and approved targeted therapies being an urgent unmet medical need. Natural polysaccharides are promising multitarget candidates, but a critical appraisal of the preclinical evidence for their translatability is lacking. Objective: This review systematically synthesizes the evidence on the efficacy, mechanisms, and methodological quality of preclinical studies investigating the antifibrotic potential of natural polysaccharides. Methods: Six databases were searched (inception to February 2025) for studies in experimental liver fibrosis models. The review followed PRISMA guidelines. Risk of bias and reporting quality were assessed using the SYRCLE (Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation) and ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines, respectively. Results: Eighty-eight studies on 44 polysaccharides were included. A major limitation was the predominant use of the carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) rat model (54.5%). Despite this, polysaccharides showed consistent efficacy: collagen deposition was suppressed in 92.0% of studies, and serum alanine/aspartate aminotransferase (ALT/AST) were reduced in 100%. Mechanistically, inhibition of the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)/Smad pathway (implicated in 60.2% of studies) and modulation of the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway (15.9%) were the most common findings. However, methodological quality was low, with unclear allocation concealment (92.0%) and absent blinding (86.4%) being pervasive issues. Conclusions: This review confirms that natural polysaccharides consistently attenuate experimental fibrosis by modulating key pathways like TGF-β/Smad. Our key contribution is highlighting a critical disconnect: demonstrated efficacy is undermined by poor methodological rigor and the use of simplistic models. This gap represents a major barrier to clinical translation. Advancing these promising agents requires prioritizing chemical standardization, employing more relevant disease models, and adhering to rigorous reporting standards.

1. Introduction

Liver fibrosis, characterized by dysregulated extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and architectural distortion, is the common pathological endpoint of chronic liver injury arising from diverse etiologies, including viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease (ALD), metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), and cholestatic disorders [1,2]. As a precursor to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), fibrosis contributes to approximately 2 million liver-related deaths annually, accounting for 4% of all deaths worldwide [3,4]. In Western populations, MAFLD affects over 25% of individuals, with 20–30% of these patients progressing to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) and 10–15% developing advanced fibrosis; ALD exhibits similar perisinusoidal fibrogenic patterns [5,6,7]. Fibrosis strongly predicts outcomes: bridging fibrosis increases liver-related mortality roughly fivefold, and cirrhosis elevates the risk tenfold [8,9]. Notably, 75–80% of HCC arises on a fibrotic background, and non-cirrhotic MAFLD accounts for 20–30% of all HCC cases [3,10]. Pathogenetically, persistent hepatocyte injury sustains inflammation through damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which activate Kupffer cells and recruit monocyte-derived macrophages [3,11]. In non-cholestatic liver injury, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) turn from quiescent, vitamin A-storing cells into collagen-producing myofibroblasts and account for more than 90% of fibrogenesis, whereas in cholestatic biliary fibrosis, portal fibroblasts are the predominant myofibroblast source [12,13]. Regarding macrophages, they have dual effects in fibrosis. Pro-inflammatory Ly6C+ (lymphocyte antigen 6 complex locus C–positive) M1 macrophages aggravate injury and initiate fibrogenesis via tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), whereas pro-resolving Ly6C-alternatively activated M2 macrophages can initially promote myofibroblast activation and matrix deposition through transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). During regression, these M2 cells can switch to a matrix-degrading phenotype, expressing matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and matrix metalloproteinase 12 (MMP12), thereby driving resolution [14,15].

Although early-stage fibrosis can regress after the underlying injury is removed, clinical management remains limited. Etiology-directed therapies are beneficial but often insufficient. For example, suppressing hepatitis B virus (HBV) reduces, but does not eliminate, the residual risk of HCC owing to persistent immune-mediated injury [16]. Moreover, no pharmacotherapy is currently approved for MAFLD, in which significant fibrosis improvement typically requires at least 10% weight loss—a threshold achieved by fewer than 15% of patients [17,18]. Cholestatic disorders such as primary biliary cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis lack disease-modifying antifibrotic therapies. Approximately 50% of biliary atresia cases ultimately require liver transplantation [19]. Direct antifibrotic drug development has also been hampered by high-profile failures; the lysyl oxidase–like 2 (LOXL2) inhibitor simtuzumab and the C-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2)/C-C motif chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) antagonist cenicriviroc were proven ineffective in phase II/III clinical trials despite promising preclinical data [20]. These setbacks underscore fundamental challenges, including etiological heterogeneity with divergent fibroblast sources, animal models that poorly recapitulate human chronic injury microenvironments, and insensitive noninvasive biomarkers for dynamic monitoring [21,22]. Addressing this unmet need will require therapies that modulate fundamental fibrogenic mechanisms such as HSC deactivation, ECM remodeling, and macrophage reprogramming.

Among natural products, natural polysaccharides have garnered substantial attention as uniquely suited candidates for antifibrotic therapy. These are high-molecular-weight biopolymers, typically composed of monosaccharide units linked by glycosidic bonds, derived from diverse sources including medicinal plants, fungi, and algae. Their structural complexity, ranging from linear homopolysaccharides like β-glucans to highly branched heteropolysaccharides, underpins their pleiotropic biological activities [23]. For instance, well-studied examples such as Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide, Lycium barbarum polysaccharide, and Astragalus polysaccharide have demonstrated potent immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and direct HSC-inactivating effects in various preclinical models [24,25,26]. Unlike many small-molecule drugs that target a single pathway, polysaccharides can simultaneously modulate multiple core drivers of fibrogenesis [27]. Furthermore, their favorable safety profiles, low production costs, and abundance in nature support their potential for scalable development.

Despite the growing body of literature demonstrating the promise of these agents, the evidence remains fragmented and has not been systematically evaluated. Preclinical studies are scattered across numerous journals, employing a wide variety of fibrosis models, polysaccharide sources, and dosing regimens. This heterogeneity can lead to seemingly contradictory results and makes it difficult for researchers to discern which polysaccharides are most promising or what mechanisms are most consistently implicated. Crucially, the methodological quality of these studies has not been critically appraised, leaving the reliability and reproducibility of the findings in question. This lack of a synthesized, quality-assessed evidence base represents a critical barrier (the research problem/gap), hindering the rational prioritization of candidates for further development and their translation into clinical trials.

This systematic review aimed to: (1) synthesize preclinical in vivo evidence on the efficacy of natural polysaccharides in liver fibrosis; (2) characterize the principal mechanisms underlying their antifibrotic activity; (3) critically assess the methodological quality and risk of bias of the included studies; and (4) identify key translational challenges and offer evidence-based recommendations for future research on polysaccharide therapies for liver fibrosis.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement [28]. The review protocol was registered prospectively on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), with registration number CRD420251076829. The protocol is available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251076829 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across six electronic databases to identify relevant preclinical studies on the use of natural polysaccharides for the treatment of liver fibrosis. The databases included PubMed, Embase, Ovid MEDLINE, HKBU Full Text Journals at Ovid, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Wanfang Database. The search period spanned from each database’s inception (build date) up to 12 February 2025. Studies published in English or Chinese were considered to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant international and regional research.

The search strategy employed a combination of the keywords “polysaccharide,” “liver fibrosis,” and their respective synonyms and related terms to maximize retrieval of relevant studies. Boolean operators (AND, OR) and truncation symbols were used to refine the search. Detailed search strategies for each database, including exact terms and operators, are provided in Supplementary File S1.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) Original preclinical animal studies (in vivo) investigating the effects of polysaccharides on liver fibrosis. (2) Studies employing established animal models of liver fibrosis, such as rats or mice. (3) Studies including a control group, either a positive control and/or a blank/vehicle control. (4) Studies reporting quantitative outcome measures related to liver fibrosis, including histological, biochemical, or molecular indicators. (5) Full-text articles published in peer-reviewed journals.

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) Studies limited to in vitro experiments only. (2) Studies measuring indicators related to liver fibrosis but where the target disease was not liver fibrosis itself. (3) Studies where polysaccharides were used not as therapeutic interventions but as diagnostic markers. (4) Studies using polysaccharides extracted from multi-component herbal formulations rather than a single polysaccharide species. (5) Reviews, systematic reviews, editorials, correspondence, conference abstracts, or case reports. (6) Duplicate publications or studies with incomplete data.

2.4. Literature Review

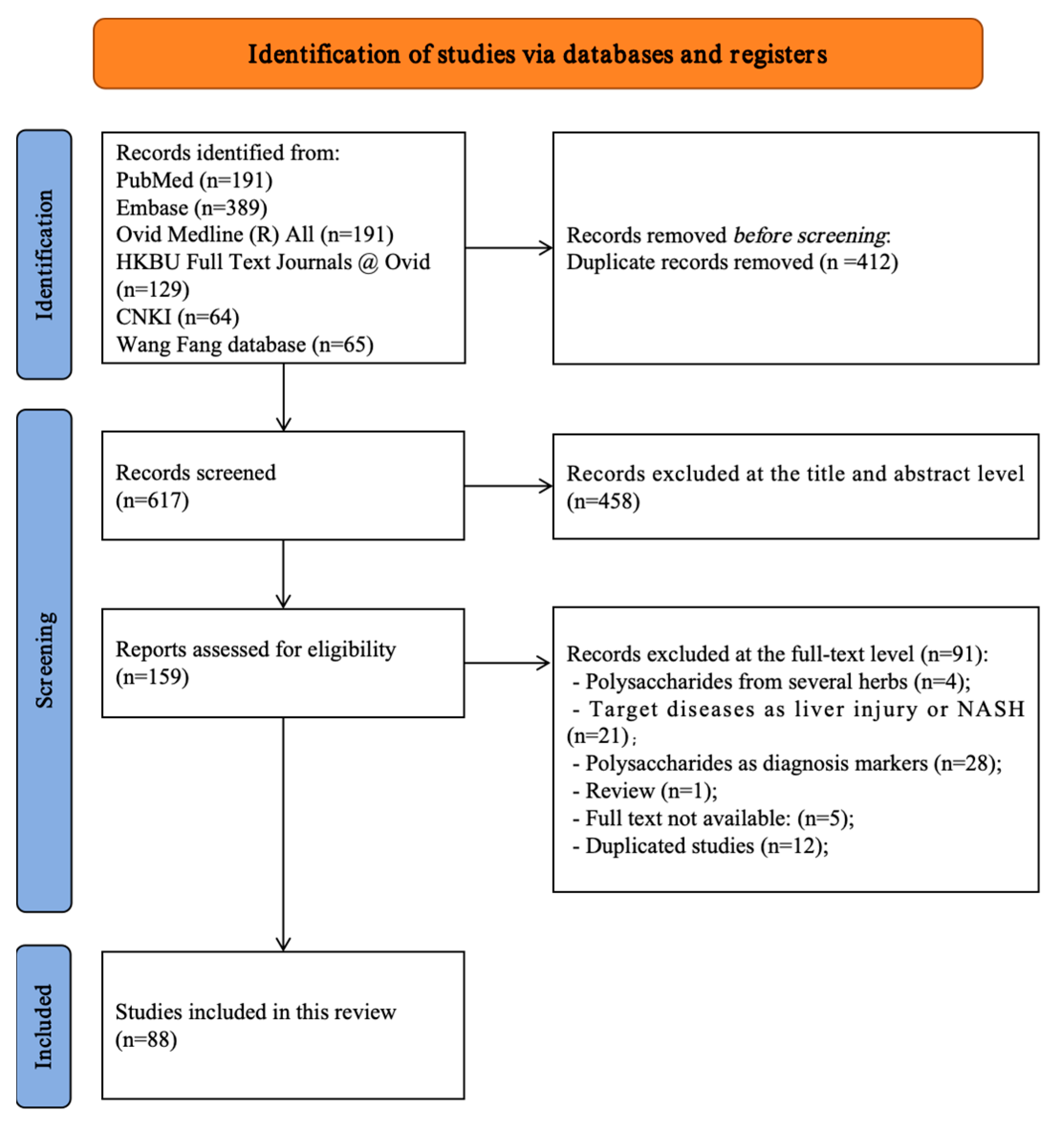

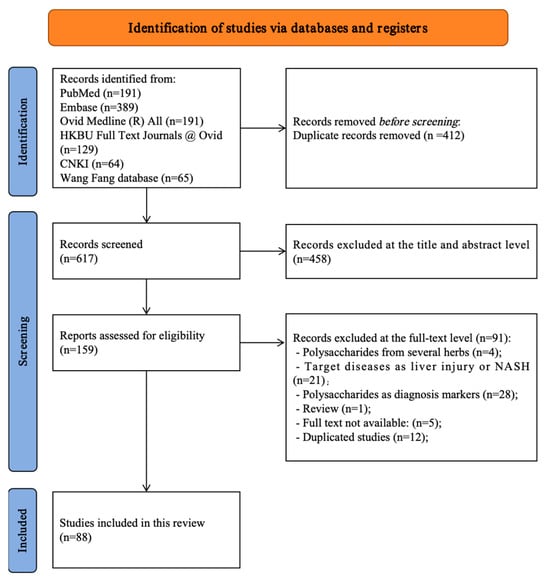

All retrieved records were imported into reference management software, and duplicates were removed prior to screening. Duplicate records were first removed automatically by the software, followed by manual verification. Two independent reviewers performed a two-stage screening process. Initially, titles and abstracts were screened to exclude clearly irrelevant articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, full-text articles of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and thoroughly assessed for final inclusion. Any disagreements between reviewers at either stage were resolved through discussion to reach a consensus. If a consensus could not be reached, a third senior reviewer was consulted for a final decision. The entire study selection process was documented and is presented using a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 1) [28].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of all included and excluded studies [28].

2.5. Data Extraction

Data extraction was independently performed by two reviewers using a predesigned standardized form. The following data were collected from each included study: first author, publication year, title, name of the polysaccharide, source of the polysaccharide, animal species and strain used, liver fibrosis model employed, total sample size, sample size per group, control group details, administration route, dosage regimen, treatment duration, frequency of administration, and the outcome measures assessed. Discrepancies in extracted data were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

2.6. Quality Assessment

The risk of bias for the included studies was assessed using the SYRCLE risk of bias tool, which is specifically designed for animal intervention studies [29]. This tool evaluates various domains, including selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other potential sources of bias. Each domain was rated as “low risk,” “high risk,” or “unclear risk” of bias based on the information provided in the studies.

Additionally, the reporting quality of the included studies was evaluated in accordance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines [30]. Key reporting items such as details on animal characteristics, experimental procedures, sample size calculation, randomization, blinding, and statistical analyses were systematically assessed to ensure comprehensive and transparent reporting.

The interpretation of our findings carefully accounted for the methodological limitations of the primary studies, including deficiencies in randomization and blinding. These limitations were explicitly detailed in our narrative synthesis, where we discussed their implications for the robustness and translatability of the results. Significant methodological heterogeneity among the studies rendered it impractical to conduct subgroup analyses to quantify the effect of bias. As such, we employed a qualitative assessment to gauge the potential impact of these methodological issues on our overall conclusions. Two reviewers independently performed the risk of bias and reporting quality assessments. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion or by consulting a third reviewer.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

A quantitative meta-analysis was not performed due to substantial heterogeneity across the included studies regarding polysaccharide types, animal models, fibrosis induction methods, administration protocols, and outcome measures. Pooling the data was considered inappropriate and likely to yield misleading results. Instead, a narrative synthesis was performed. The results from the included studies were summarized descriptively, focusing on the characteristics of animal models, interventions, comparators, and outcome measures. Key findings were grouped according to the type of polysaccharide, animal model, and major outcomes. Tables and figures were used to present study characteristics and main results for clarity and comparison.

3. Results

3.1. Study Search and Selection

A systematic search of six databases (PubMed, Embase, Ovid MEDLINE, HKBU Full Text Journals at Ovid, CNKI, and Wanfang) identified 1029 records. After automated and manual deduplication, 412 records were removed, leaving 617 unique records for title and abstract screening. Of these, 458 were excluded because they were reviews, employed disease models not focused on liver fibrosis, or investigated interventions unrelated to natural polysaccharides. The full texts of 159 articles were assessed for eligibility, and 71 were excluded for the following reasons: four examined polysaccharide mixtures without isolated-component analysis; 21 addressed non-fibrotic liver conditions (e.g., acute liver injury or MAFLD without fibrosis quantification); 28 used polysaccharides as diagnostic markers rather than therapeutic agents; one was a review; five full texts were unavailable; and 12 were duplicate publications. A total of 88 studies (published between 2000 and 2025) met the predefined inclusion criteria and were included in data extraction and synthesis. Manual screening of reference lists did not yield additional eligible studies. The study selection process is depicted in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 1), and detailed study information and a reference list are provided in Supplementary Files S2 and S3.

3.2. Polysaccharide Varieties and Sources

The 88 included studies evaluated 44 distinct natural polysaccharides from diverse biological sources. Botanical polysaccharides were the largest category (21/44, 47.7%), notably Dicliptera chinensis polysaccharide (11 studies), Lycium barbarum polysaccharide (9 studies), and Dendrobium species polysaccharides (4 studies). Fungal polysaccharides accounted for 15/44 (34.1%), led by Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide (3 studies), Cordyceps polysaccharides (4 studies, including C. sinensis and C. militaris), and Phellinus species polysaccharides (3 studies). Marine/algal polysaccharides included fucoidan (from Fucus vesiculosus and Chondrus/Chadosiphon species; 4 studies) and a Sargassum polysaccharide (1 study).

Substantial structural diversity was reported, including neutral polysaccharides (e.g., inulin-like ABWW from Achyranthes bidentata), acidic/sulfated polysaccharides (e.g., fucoidan), and chemically modified derivatives (e.g., selenium-modified Se-BSP from Bletilla striata). Dicliptera chinensis polysaccharide (11 studies) and Lycium barbarum L. polysaccharide (9 studies) were the most extensively investigated, whereas 35 polysaccharides were reported only once. Full polysaccharide–source mappings are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Polysaccharides in treating liver fibrosis.

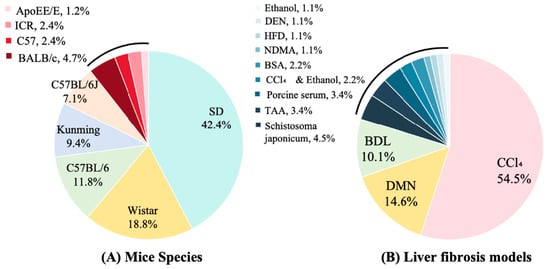

3.3. Experimental Models and Control Groups

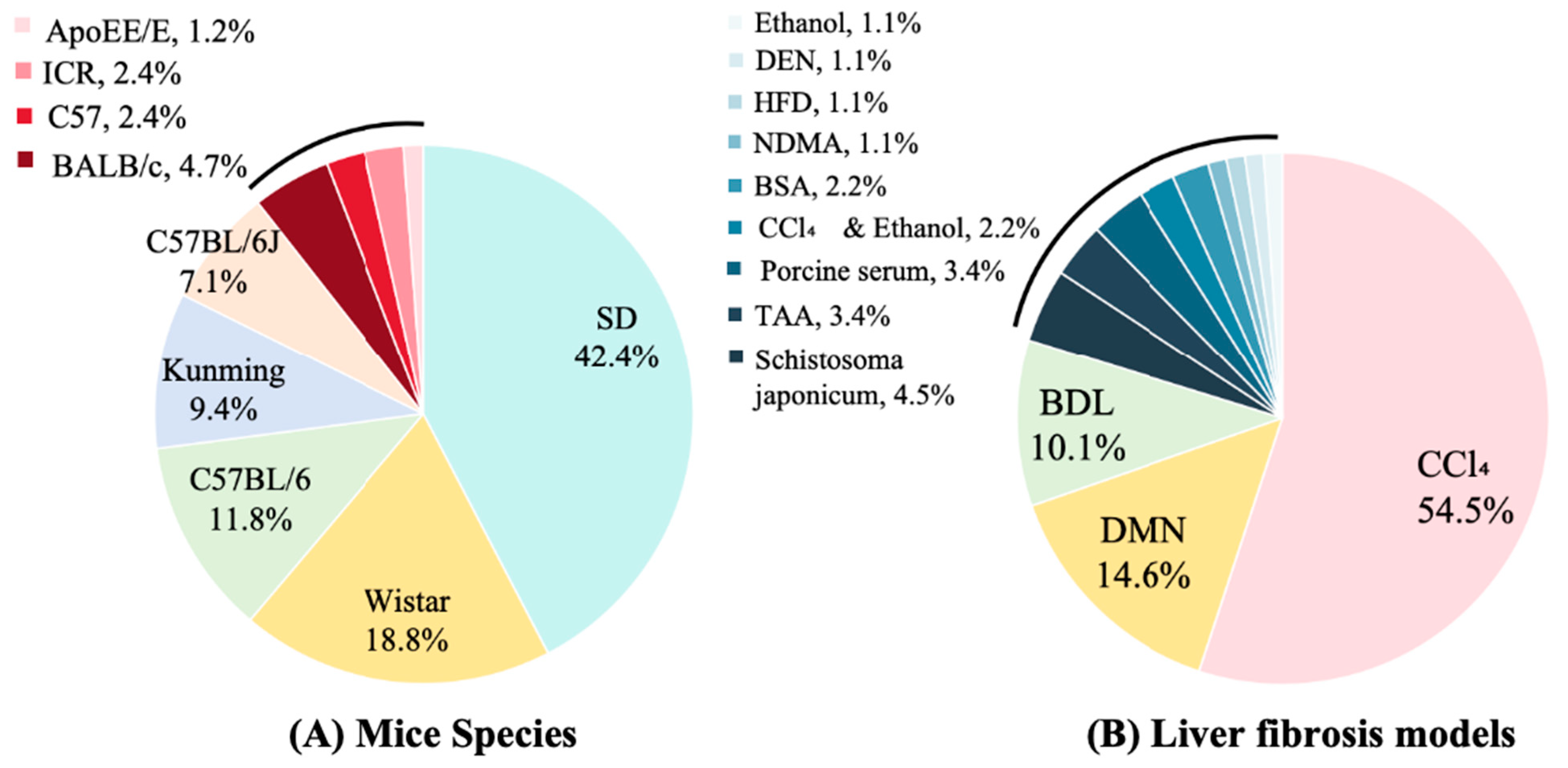

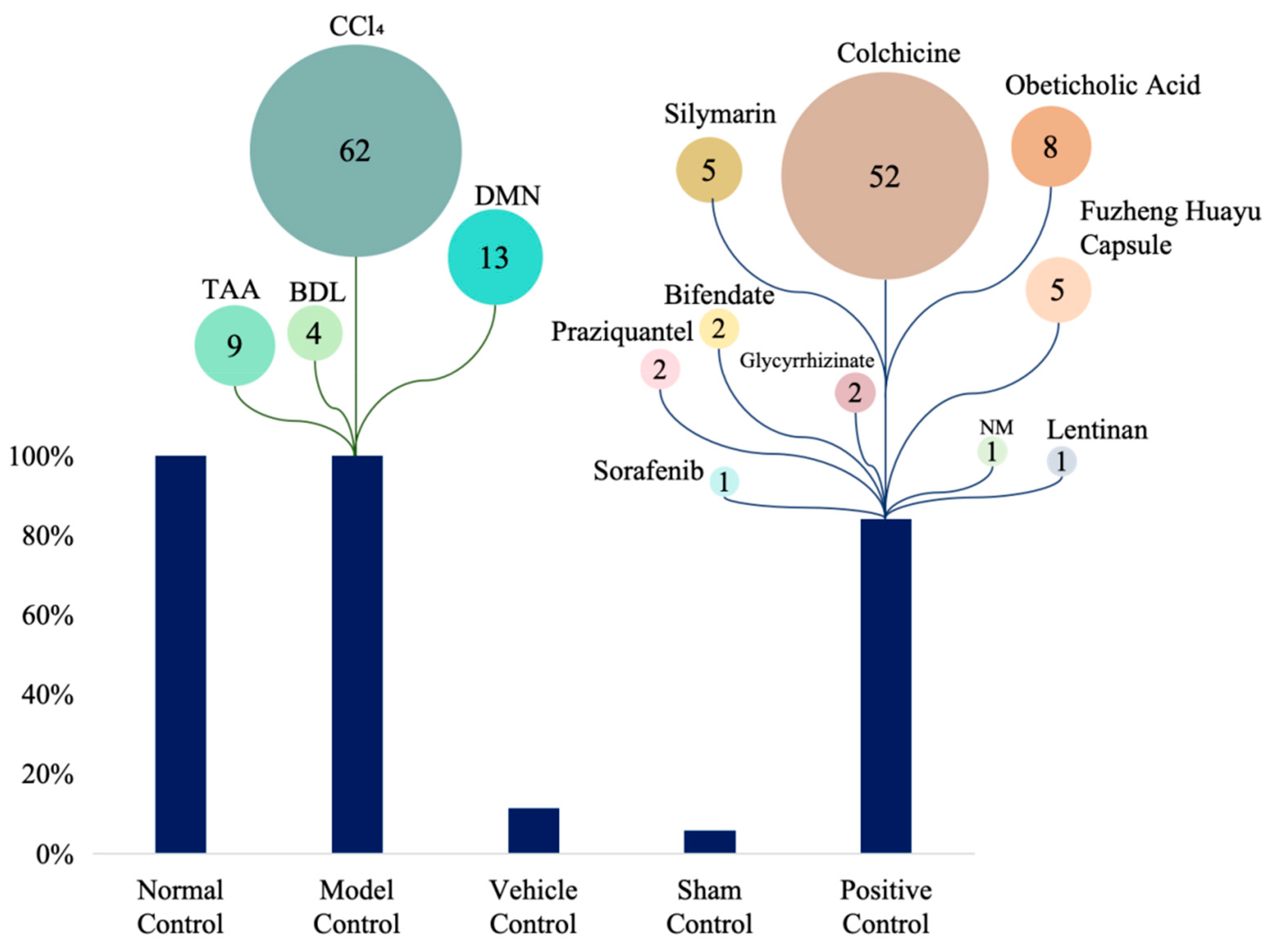

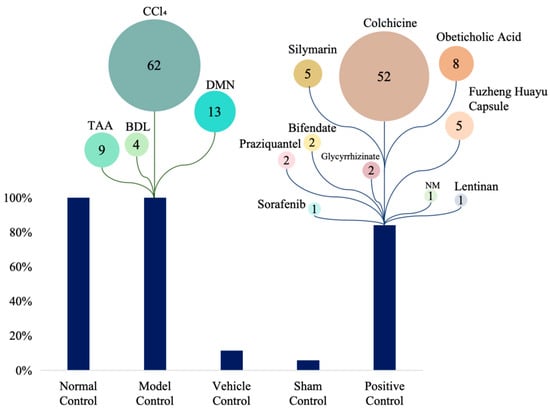

All studies employed rodent models. Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats were the most commonly used (42.4% of in vivo studies), followed by Wistar rats (18.8%) and C57BL/6 mice (11.8%); Kunming and BALB/c mice were used less frequently (9.4% and 4.7%, respectively) (Figure 2A). Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) administration was the predominant fibrosis induction method (54.5%), with dimethylnitrosamine (DMN, 14.6%), bile duct ligation (BDL, 10.1%), and thioacetamide (TAA, 3.4%) also commonly employed. Less frequent approaches included schistosomiasis infection (4.5%), porcine serum immunization (3.4%), and high-fat diet (HFD, 1.1%) (Figure 2B). Control-group designs varied across studies: 62% included normal (uninjured) controls, 13% used model controls (fibrotic, untreated animals), 9% incorporated vehicle controls, and 4% used sham-surgical controls. Positive control arms were present in 52% of studies. Among active comparators, colchicine was the most common (used in 52% of studies with a positive control), followed by obeticholic acid (8%), silymarin (5%), and Fuzheng Huayu capsule (5%) (Figure 3). Sample sizes were heterogeneous. Total animals per study ranged from 18 to 123 (median 50), and 16 studies reported exactly 50 animals. Polysaccharide treatment arms were generally small: 30 studies (34.5%) enrolled 4–9 animals per group, 28 studies (32.2%) enrolled 10 animals per group, and 26 studies (29.9%) enrolled 11–20 animals per group; no treatment group exceeded 20 animals. Three studies (3.4%) did not report group-level sample sizes.

Figure 2.

Mice species and models in included studies. DMN: Dimethylnitrosamine; BDL: Bile Duct Ligation; TAA: Thioacetamide; BSA: Bovine Serum Albumin; NDMA: N-Nitrosodimethylamine; HFD: High-fat diet; DEN: Diethylnitrosamine.

Figure 3.

Control types and comparator drugs in included studies. DMN: Dimethylnitrosamine; BDL: Bile Duct Ligation; TAA: Thioacetamide; NM: Not mentioned. The numbers indicate the number of studies applying each model or drug, indicating their relative usage.

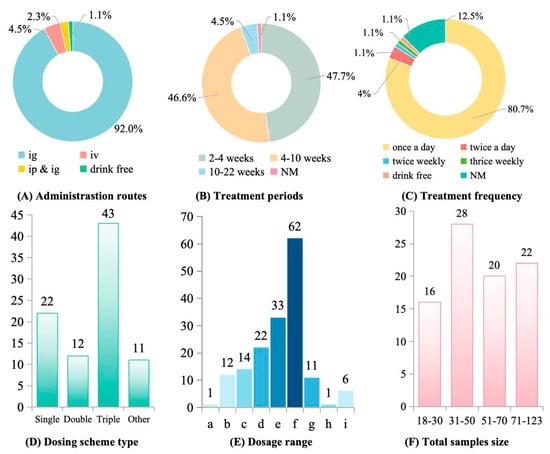

3.4. Administration Parameters and Dosage Regimens

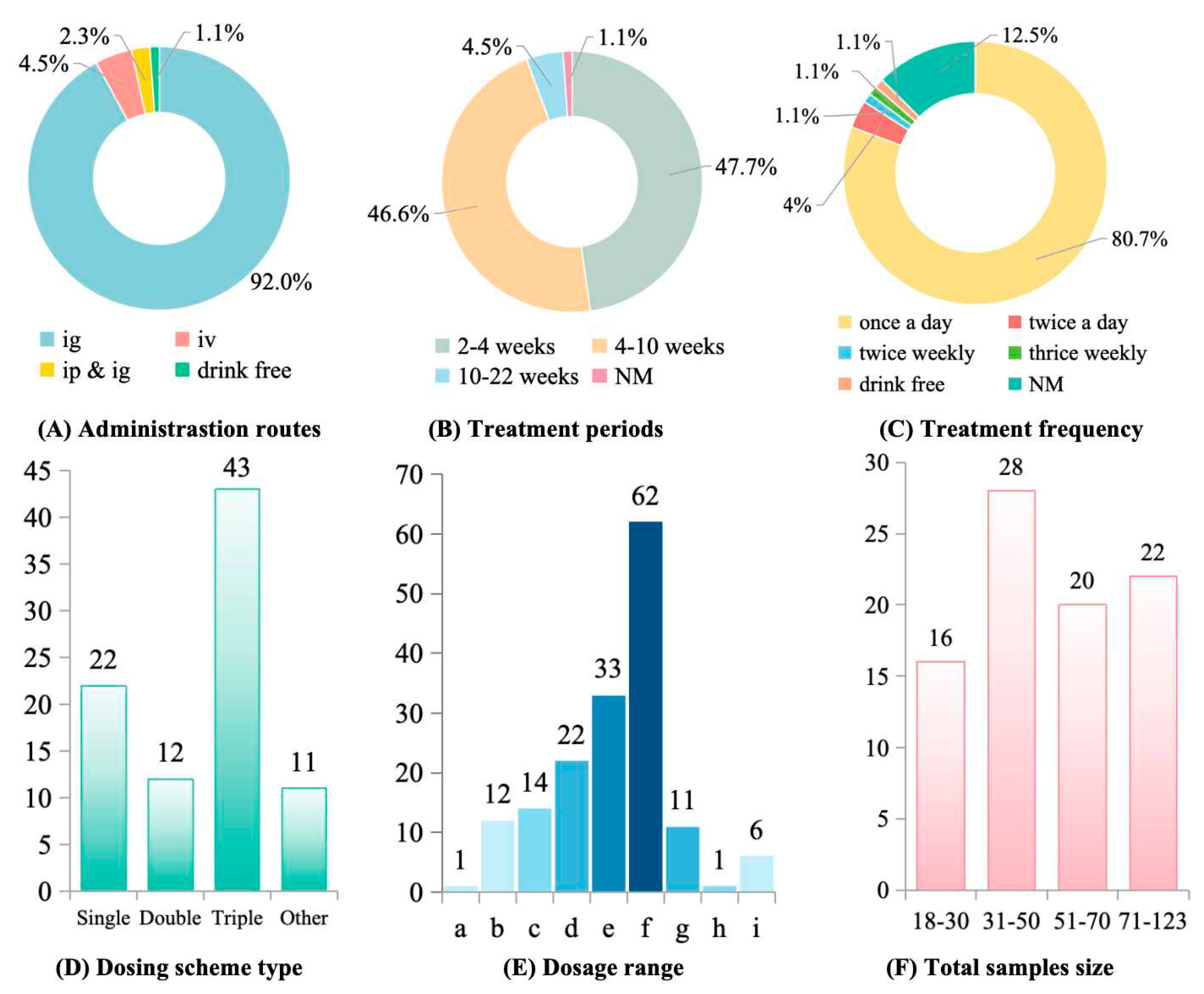

Administration routes and dosing regimens varied widely. Intragastric delivery was most common (73.6%), followed by intraperitoneal injection (18.3%) and intravenous injection (5.2%); 3.1% of studies did not specify the administration route (Figure 4A). Treatment durations ranged from acute (1–2 weeks) to chronic (>12 weeks), with most studies (64.7%) lasting 4–8 weeks (Figure 4B). Daily dosing was predominant (82.4%), while intermittent schedules (every 2–3 days) were used in 11.8% of studies (Figure 4C). Most studies evaluated therapeutic interventions initiated after fibrosis had been established (68.3%), whereas 31.7% assessed preventive regimens administered concurrently with the fibrogenic insult (Figure 4D). Effective dose ranges varied widely: 44.1% of studies used 100–200 mg/kg, 23.5% used 200–500 mg/kg, 17.6% reported efficacy at low doses (10–50 mg/kg), and 8.8% tested doses >500 mg/kg (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Polysaccharides administration parameters and sample size in treating liver fibrosis. (A) Administration routes. ig: Intragastric Administration; iv: Intravenous Injection; ip: Intraperitoneal Injection; NM: Not mentioned. (B) Treatment periods. (C) Treatment frequency. (D) Dosing scheme type. “Other” means “Non-mg/kg units”. (E) Dosage range. a: <1 mg/kg; b: 1–10 mg/kg; c: 10–50 mg/kg; d: 50–100 mg/kg; e: 100–200 mg/kg; f: 200–500 mg/kg; g: 500–1000 mg/kg; h: 1000–5000 mg/kg; i: >5000 mg/kg. There are more than one dosage in some studies. (F) Total sample size.

3.5. Outcome Measures and Mechanistic Pathways

Antifibrotic efficacy was assessed across ten biomarker categories (Table 2). Serum liver enzymes were routinely measured: ALT/AST in 96.6% of studies and ALP/GGT in 68.2%. Fibrosis quantification relied primarily on histological collagen staining (Sirius Red or Masson; 71.6%) and serum fibrosis panels (HA, LN, PCIII, and IVC; 77.3%). α-SMA immunostaining, a marker of HSC activation, was reported in 85.2% of studies. Oxidative stress markers (SOD, MDA) and inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) were assessed in 65.9% and 73.9% of studies, respectively. Emerging endpoints included gut–liver axis markers (ZO-1, LPS; 31.8%) and ECM remodeling enzymes (MMP-9, TIMP-1; 59.1%).

Table 2.

Classification of outcome indicators for polysaccharide treatment of liver fibrosis.

Mechanistic analyses most often implicated the transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1)/Smad axis (60.2% of studies), typically showing reductions in TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-beta receptor type I/II (TβR-I/II), and phosphorylated Smad2/3 (p-Smad2/3) and increased Smad7. The TLR4/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway was the next most reported (15.9%, 14/88), usually evidenced by decreased TLR4, myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88), and phosphorylated NF-κB p65. Additional mechanisms included inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling with reduced p-ERK and p-JNK activities, modulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K)/AKT-related apoptosis pathways (changes in p-AKT and caspase-3), and activation of Nrf2-dependent antioxidant responses (HO-1/NQO1, heme oxygenase-1/NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1). Notch and Wnt/β-catenin pathways were rarely examined. Detailed pathway-target mappings appear in Table 3.

Table 3.

Signaling pathways in liver fibrosis research.

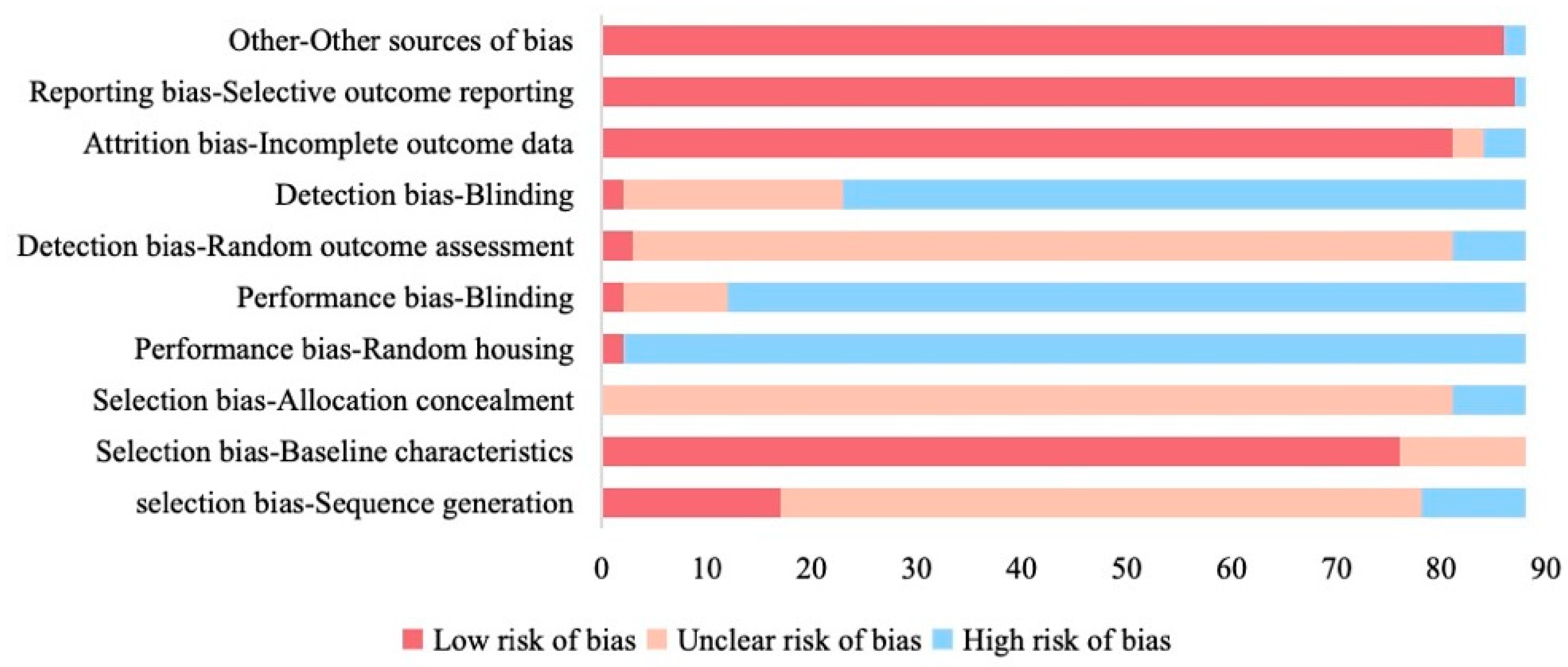

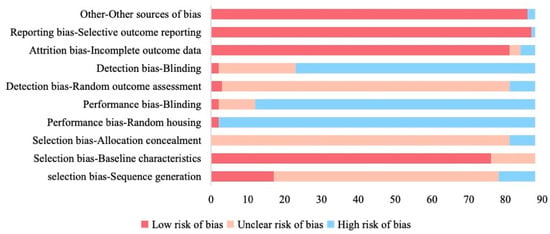

3.6. Methodological Quality Assessment

The SYRCLE risk-of-bias assessment revealed pervasive methodological shortcomings (Figure 5). Sequence generation was inadequately described in 69.3% (61/88) and judged high risk in 11.4% (10/88). Allocation concealment was poorly reported (92.0% unclear; 8.0% high risk). Performance bias was prominent. For example, caregiver blinding was unreported or absent in 86.4% (high risk), and random housing was not documented in 97.7% (high risk). Detection bias was also common, with outcome assessor blinding lacking in 74.4% of studies and random outcome assessment unclear in 88.6% of studies. By contrast, attrition bias (95.5% low/unclear) and reporting bias (98.9% low/unclear) were less pronounced, and baseline characteristics were well documented in 86.4% of studies.

Figure 5.

Quality assessment of included studies based on SYRCLE risk of bias tool.

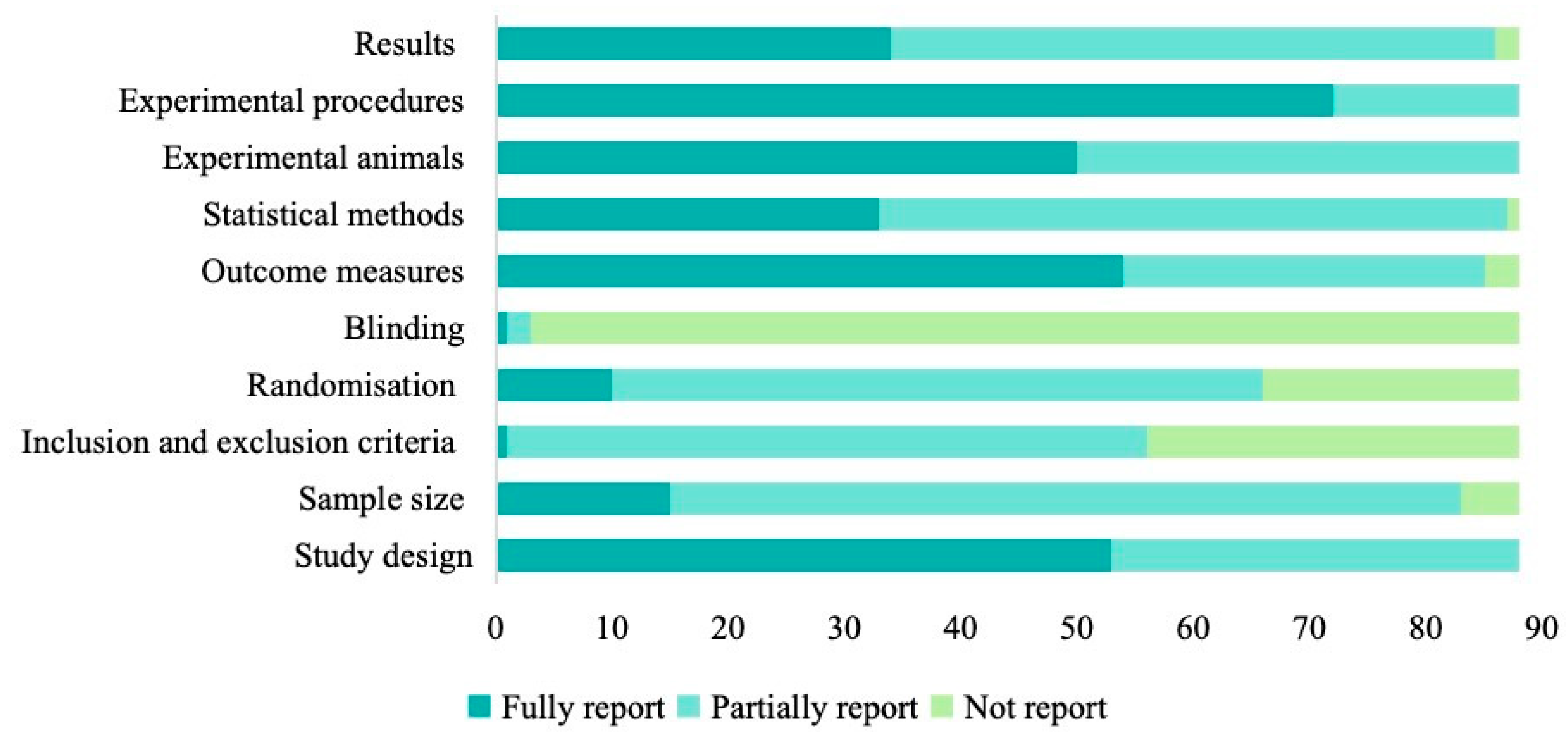

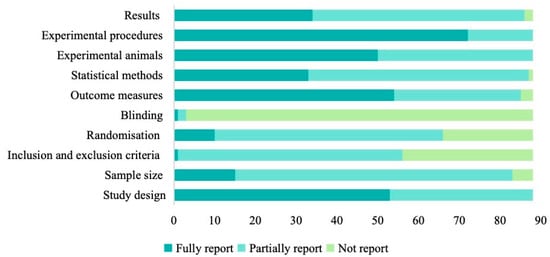

Assessment against ARRIVE 2.0 highlighted further reporting gaps (Figure 6). Only 11.4% (10/88) fully described randomization, while 25.0% (22/88) gave no details. Blinding was comprehensively reported in just one study (1.1%) and omitted in 96.6% (85/88). Sample size justification was missing in 5.7% (5/88) and only partially addressed in 77.3% (68/88). Inclusion/exclusion criteria were incompletely documented in 36.4% (32/88). In contrast, experimental procedures were well described in 81.8% of studies, statistical methods appeared in 98.9% (87/88) of reports (37.5% fully, 61.4% partially), and outcome measures were fully reported in 61.4% (54/88).

Figure 6.

The quality assessments of included articles based on ARRIVE guidelines.

4. Discussion

Our systematic review demonstrates that natural polysaccharides exert their antifibrotic effects through a multi-pronged mechanism, converging on three core pathological axes: fibrogenic signaling, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

The most frequently reported mechanism was the direct inhibition of the canonical TGF-β/Smad pathway (reported in 60.2% of studies). Polysaccharides appear to function as upstream regulators in this cascade. It is hypothesized that many polysaccharides, particularly those rich in β-glucans, can act as pattern recognition receptor (PRR) modulators. For instance, they may compete with endogenous ligands for binding to receptors like Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4), thereby downregulating the MyD88-dependent pathway that often leads to pro-inflammatory cytokine production and subsequent TGF-β1 activation in HSCs [31]. By suppressing TGF-β1 expression or its receptor signaling, polysaccharides consequently reduce the phosphorylation of Smad2/3, leading to decreased nuclear translocation and reduced transcription of profibrotic genes such as α-SMA and collagen I [32]. The concurrent upregulation of the inhibitory Smad7, reported in several high-quality studies, further reinforces this homeostatic rebalancing [33,34]. It should be critically acknowledged, however, that these mechanisms are mostly suggested by indirect markers rather than being causally established. Few studies have moved beyond association to confirmation by using tools like pharmacological inhibitors or gene knockout. As such, the current body of evidence is largely associative and lacks definitive proof.

This anti-fibrogenic activity is tightly interwoven with potent antioxidant (65.9% of studies) and anti-inflammatory (73.9% of studies) effects. Mechanistically, polysaccharides do not simply scavenge free radicals. Instead, many are proposed to activate the Nrf2-ARE antioxidant pathway [35]. By inducing the nuclear translocation of Nrf2, they upregulate a battery of endogenous antioxidant enzymes like SOD and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), while decreasing lipid peroxidation products like MDA, a well-established mechanism for Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress regulation [36]. This reduction in oxidative stress directly alleviates a primary trigger for HSC activation [37]. Concurrently, the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 is likely linked to the inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway. The previously mentioned modulation of TLR4, as well as direct interactions with other receptors on macrophages, can prevent the activation of IκB kinase (IKK) and subsequent degradation of IκBα, thus sequestering NF-κB in the cytoplasm and preventing the transcription of inflammatory genes, a well-characterized mechanism of NF-κB pathway inhibition [38].

Therefore, the therapeutic profile of polysaccharides is not merely a collection of parallel effects but an integrated network: by dampening inflammatory signals (e.g., via TLR4/NF-κB), they reduce the triggers for both oxidative stress and TGF-β production. By bolstering endogenous antioxidant defenses (e.g., via Nrf2), they protect hepatocytes from injury and remove another key stimulus for HSC activation. This integrated mechanism explains their consistent efficacy across diverse preclinical models and underscores their potential as true disease-modifying agents.

While our findings corroborate prior reviews on the multitarget actions of natural products [39], this review provides the first granular synthesis focused specifically on polysaccharides. By quantitatively mapping the landscape of preclinical models, administration routes, and reported mechanisms, we establish a comprehensive evidence base. However, this analysis reveals a critical limitation within the field: the evidence is overwhelmingly dominated by CCl4-induced models (54.5% of studies), which primarily reflect acute, toxin-driven injury pathways [40]. This over-reliance on acute toxic injury models may lead to an overestimation of the anti-fibrotic efficacy of polysaccharides, particularly by amplifying the perceived importance of their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Consequently, the antifibrotic mechanisms identified, such as potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, may be overrepresented in their importance. Models reflecting the more clinically relevant etiologies of MAFLD or cholestasis were significantly underrepresented. Therefore, the applicability of these findings to human disease must be approached with caution and requires validation in more etiologically relevant systems. We strongly recommend that future research prioritize the adoption of alternative models that more closely recapitulate the complex pathophysiology of human disease. Examples include HFD-induced MAFLD models, methionine- and choline-deficient (MCD) diet models, BDL models, or relevant genetically engineered models.

Despite the considerable therapeutic potential demonstrated by polysaccharides, our analysis identifies a central translational bottleneck: a widespread lack of investigation into Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR). This issue stems from the severely inadequate chemical characterization of the polysaccharides used in the included studies. Forty-four distinct polysaccharides converge on overlapping targets, most notably TGF-β, TLR4, and MAPK nodes, enhancing biological plausibility but obscuring structure–activity relationships. As the majority of studies failed to report critical structural parameters—such as molecular weight, glycosidic linkage types (e.g., β-(1 → 3) vs. β-(1 → 6)), monosaccharide composition, or the presence of functional groups like sulfate or carboxyl moieties—it was impossible for us to correlate specific chemical features with the observed biological effects. Efficacy readouts vary widely despite similar chemical classifications: α-SMA inhibition ranges from 24.3% to 81.5% [41,42]. Methodological heterogeneity compounds this ambiguity; the dosing spans an order of magnitude (50–800 mg/kg), 37% of studies report nonlinear pharmacodynamic responses, and fibrosis models yield divergent efficacy profiles. For example, BDL exhibits a 38% weaker response to TLR4 inhibitors than CCl4. Short treatment durations (<4 weeks) also risk missing late-phase mechanisms such as Smad7 induction [43,44,45]. Accordingly, rigorous chemical standardization, especially molecular-weight stratification and glycosidic linkage profiling, is imperative to resolve these structure-function paradoxes and enable cross-study validation of these promising bioactive agents [46]. This bottleneck not only impedes a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of action but also makes it exceedingly difficult to prioritize the most promising candidates for clinical translation from a vast pool of potential molecules.

Natural polysaccharides possess several attributes favorable for clinical translation: widespread availability, generally low acute toxicity, and the potential for multitarget modulation of fibrogenic pathways. However, important translational barriers must be addressed before clinical evaluation. First, methodological deficiencies undermine the reliability of the evidence. Allocation concealment was not reported in 92.0% of the studies, and blinding procedures were omitted in most, a common methodological flaw known to amplify selection and performance bias [47]. Furthermore, small group sizes were common (61.8% used ≤10 animals per group), thereby increasing the risk of effect overestimation, as is well-established in statistical methodology [48]. Second, pharmacological incongruence exists between rodent and human physiology [49]. Rodent doses that were frequently effective (100–200 mg/kg in 44.1% of studies) convert, by allometric scaling, to human-equivalent doses of roughly 1–2 g/day for a 60 kg adult [50]. This raises feasibility concerns because several polysaccharides have limited oral bioavailability. For example, fucoidan exhibits less than 15% oral absorption [51,52,53]. For context, many approved small-molecule drugs achieve oral bioavailability greater than 50%, and the “high permeability” category in the Biopharmaceutics Classification System is defined by at least 90% absorption in humans [54,55]. Therefore, formulation and delivery limitations represent major translational hurdles. Third, limitations in model relevance persist. The preclinical literature is dominated by chemically induced fibrosis models, particularly CCl4 and Sprague-Dawley rats, neither of which fully recapitulates the pathophysiology of human metabolic fibrosis or progressive cholestatic scarring [56,57,58]. Consequently, promising candidates validated primarily in CCl4 models may underperform in clinically relevant contexts.

Three underexplored avenues could be transformative if prioritized to accelerate translation: modulation of the gut-liver axis, structural bioengineering and formulation, and human-relevant model systems. In 22.7% (20/88) of studies, polysaccharides exhibited prebiotic effects, including preservation of the tight junction protein ZO-1 and reductions in systemic LPS, suggesting a capacity to modulate endotoxin-driven inflammation; one study reported that ophiopogon fructans (OJP-W2) reduced portal hypertension by about 38% through butyrate-dependent mechanisms, suggesting that trials in portal hypertensive fibrosis could be warranted [59]. Moreover, chemically modified polysaccharides show markedly higher hepatic accumulation in imaging studies. For example, selenium-modified Bletilla striata polysaccharide (Se-BSP) and low-molecular-weight fucoidan fractions demonstrate efficacy at substantially lower doses, such as 50 mg/kg, indicating that rational modification and fractionation can improve druggability and reduce required exposures [60,61]. Although underused, patient-derived liver organoids, pioneered through methods like those described in reference [62], and other precision in vitro platforms show promise. Preliminary work indicates that Ganoderma polysaccharides reproduced in vivo reductions in collagen I and α-SMA in patient-derived organoids, supporting scalable, human-relevant screening paradigms to prioritize candidates before costly in vivo validation [23,47,63].

Methodological limitations exist at both the study and review levels. At the study level, common deficiencies included absent or poorly described random sequence generation, lack of allocation concealment, and infrequent blinding of caregivers and outcome assessors, factors that increase the risk of bias. Small group sizes and missing sample-size justifications were also common, reducing statistical reliability. Outcome heterogeneity, such as varying histological scoring systems, differing serum marker panels, and inconsistent molecular endpoints, further hindered cross-study comparisons and precluded meta-analysis. At the review level, despite conducting extensive database searches, even an exploratory meta-analysis was infeasible. This was due to the extreme heterogeneity across the included studies in terms of interventions (44 different polysaccharides), models, and outcome reporting. Pooling such disparate data would have yielded results that are statistically precise but clinically meaningless and misleading, thereby violating the fundamental principles of meta-analysis. In addition, heterogeneity in polysaccharide preparations and endpoints limited quantitative synthesis.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review offers the most comprehensive evidence to date on the antifibrotic effects of natural polysaccharides. It clearly demonstrates that various natural polysaccharides inhibit fibrosis in preclinical models of liver fibrosis. Our review indicates that natural polysaccharides primarily act by suppressing the TGF-β/Smad pathway and reducing inflammation and oxidative stress through the TLR4/NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways. These findings suggest natural polysaccharides are a promising therapeutic strategy for liver fibrosis.

However, we also highlight critical issues in current preclinical research. Over-reliance on toxin-induced models often fails to reflect the complex clinical realities of liver fibrosis patients, thereby limiting the translational potential of the findings. Additionally, many studies are limited by methodological defects, such as the lack of randomization, inadequate blinding, and small sample sizes, which weaken the soundness and credibility of their conclusions. These limitations collectively hamper the efficiency of clinical translation and the perceived reliability of natural polysaccharides as treatments for liver fibrosis. Therefore, we call for a shift in modeling approaches for liver fibrosis and advocate for more well-designed and standardized preclinical studies on polysaccharide-based therapies to accelerate their successful clinical translation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/polysaccharides7010019/s1, File S1: Search strategies for systematic review of polysaccharides in treating liver fibrosis; File S2: Detailed information of included studies.; File S3: Reference list for included studies.; File S4: Classification of Outcome Indicators of polysaccharide treatment of liver fibrosis (with references).; File S5: PRISMA Checklist.

Author Contributions

J.W. conceived the study, designed the methodology, conducted the formal analysis, and drafted the original manuscript. Y.Y. performed independent, duplicate literature screening, data extraction, and quality assessment. W.J. and H.Y. assisted with data analysis, validation, and visualization. Q.H. and J.X. contributed to the investigation, data curation, and interpretation of results. H.Y.K. and A.L. supervised the project, acquired funding, and provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515011811), Health and Medical Research Fund (08193596), Initial Grant for Faculty Niche Research Areas (RC-FNRA-IG/23–24/SCM/01), Seed Funding for Collaborative Research Grants (RC-SFCRG/23–24/SCM/02) and Vincent and Lily Woo Foundation (No. 42.4621.179636).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515011811), Health and Medical Research Fund (08193596), Initial Grant for Faculty Niche Research Areas (RC-FNRA-IG/23–24/SCM/01), Seed Funding for Collaborative Research Grants (RC-SFCRG/23–24/SCM/02) and Vincent and Lily Woo Foundation(No. 42.4621.179636).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviation

A/G: Albumin/Globulin Ratio; AKT: Protein Kinase B; ALB: Albumin; ALD: Alcoholic liver disease; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; Bax: BCL2-Associated X Protein; Bcl-2: B-cell Lymphoma 2; BDL: Bile Duct Ligation; BSA: Bovine Serum Albumin; BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen; CAT: Catalase; CCl4: Carbon Tetrachloride; CCR2: C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 2; CCR5: C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 5; CDKs: Cyclin-Dependent Kinases; COX-2: Cyclooxygenase-2; CVF: Collagen Volume Fraction; CXCL12: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 12; DAMPs: Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns; DBIL: Direct Bilirubin; DEN: Diethylnitrosamine; DMN: Dimethylnitrosamine; ECM: Extracellular Matrix; ERK: Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase; Gal-3: Galectin-3; GGT: γ-Glutamyl Transferase; GSH: Reduced Glutathione; GSH-Px: Glutathione Peroxidase; HA: Hyaluronic Acid; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HDL-C: High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; Hes1: Hairy and Enhancer of Split 1; HFD: High-Fat Diet; HO-1: Heme Oxygenase 1; HSCs: Hepatic Stellate Cells; Hyp: Hydroxyproline; IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma; IL-10: Interleukin-10; IL-1β: Interleukin-1 beta; IL-22: Interleukin-22; IL-6: Interleukin-6; IL-8: Interleukin-8; iNOS: Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase; ITGβ1: Integrin Beta-1; IV-C: Collagen Type IV; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal Kinase; LDH: Lactate Dehydrogenase; LDL-C: Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; LN: Laminin; LOXL2: Lysyl Oxidase–Like 2; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; MAFLD: Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; MCP-1: Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1; MDA: Malondialdehyde; MMPs: Matrix Metalloproteinases; MT: Metallothionein; MyD88: Myeloid Differentiation Primary Response 88; NDMA: N-Nitrosodimethylamine; Notch 1: Neurogenic Locus Notch Homolog Protein 1; NQO1: NAD(P)H Quinone Dehydrogenase 1; Nrf2: Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2; PAI-1: Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1; PCIII: Procollagen III; PCNA: Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen; PDGF: Platelet-Derived Growth Factor; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase; PRR: Pattern Recognition Receptor; ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; SAR: Structure-Activity Relationships; SCFAs: Short-Chain Fatty Acids; SD: Sprague–Dawley; SOD: Superoxide Dismutase; TAA: Thioacetamide; TBIL: Total Bilirubin; TC: Total Cholesterol; TG: Triglycerides; TGF-β1: Transforming Growth Factor-beta 1; TIMPs: Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinases; TLR4: Toll-Like Receptor 4; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; TP: Total Protein; TβR: TGF-β Receptor; Wnt: Wnt Family Member; ZO-1: Zonula Occludens-1; α-SMA: Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin; β-catenin: Beta-Catenin.

References

- Caligiuri, A.; Gentilini, A.; Pastore, M.; Gitto, S.; Marra, F. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Liver Fibrosis Regression. Cells 2021, 10, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehlen, N.; Crouchet, E.; Baumert, T.F. Liver fibrosis: Mechanistic concepts and therapeutic perspectives. Cells 2020, 9, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zargar, A.H.; Bhansali, A.; Majumdar, A.; Maheshwari, A.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Dasgupta, A.; Saboo, B.D.; Sethi, B.K.; Sanyal, D.; Seshadri, K.G.; et al. Management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)-An expert consensus statement from Indian diabetologists’ perspective. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Wu, D.; Mao, R.; Yao, Z.; Wu, Q.; Lv, W. Global burden of MAFLD, MAFLD related cirrhosis and MASH related liver cancer from 1990 to 2021. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Zhao, L.; Wang, T.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Du, F.; Chen, Y.; Deng, S.; Shen, J.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Alcoholic liver disease: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic potential of traditional Chinese medicine through preclinical and clinical evidence. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 353, 120465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, P.; Kleiner, D.E.; Dam-Larsen, S.; Adams, L.A.; Björnsson, E.S.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P.; Mills, P.R.; Keach, J.C.; Lafferty, H.D.; Stahler, A.; et al. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 389–397.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulai, P.S.; Singh, S.; Patel, J.; Soni, M.; Prokop, L.J.; Younossi, Z.; Sebastiani, G.; Ekstedt, M.; Hagstrom, H.; Nasr, P.; et al. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 2017, 65, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.H.; Lin, S.H.; Lee, M.Y.; Wang, H.C.; Tsai, K.F.; Chou, C.K. Mitochondrial alterations and signatures in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2025, 44, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenkel, O.; Puengel, T.; Govaere, O.; Abdallah, A.T.; Mossanen, J.C.; Kohlhepp, M.; Liepelt, A.; Lefebvre, E.; Luedde, T.; Hellerbrand, C.; et al. Therapeutic inhibition of inflammatory monocyte recruitment reduces steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis. Hepatology 2018, 67, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Rosenthal, S.B.; Liu, X.; Miciano, C.; Hou, X.; Miller, M.; Buchanan, J.; Poirion, O.B.; Chilin-Fuentes, D.; Han, C.; et al. Multi-modal analysis of human hepatic stellate cells identifies novel therapeutic targets for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, R.G.; Schwabe, R.F. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in the liver. Semin Liver Dis. 2015, 35, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, P.; Dobie, R.; Wilson-Kanamori, J.R.; Dora, E.F.; Henderson, B.E.P.; Luu, N.T.; Portman, J.R.; Matchett, K.P.; Brice, M.; Marwick, J.A.; et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature 2019, 575, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A.; Vannella, K.M. Macrophages in tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity 2016, 44, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ye, X.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; You, J.; Feng, Y. Linking fatty liver diseases to hepatocellular carcinoma by hepatic stellate cells. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2024, 4, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassailly, G.; Caiazzo, R.; Ntandja-Wandji, L.C.; Gnemmi, V.; Baud, G.; Verkindt, H.; Ningarhari, M.; Louvet, A.; Leteurtre, E.; Raverdy, V.; et al. Bariatric Surgery Provides Long-term Resolution of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Regression of Fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1290–1301.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsome, P.N.; Buchholtz, K.; Cusi, K.; Linder, M.; Okanoue, T.; Ratziu, V.; Sanyal, A.J.; Sejling, A.-S.; Harrison, S.A. A placebo-controlled trial of subcutaneous semaglutide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manns, M.P.; Bergquist, A.; Karlsen, T.H.; Levy, C.; Muir, A.J.; Ponsioen, C.; Trauner, M.; Wong, G.; Younossi, Z.M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.A.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Caldwell, S.; Shiffman, M.L.; Diehl, A.M.; Ghalib, R.; Lawitz, E.J.; Rockey, D.C.; Schall, R.A.; Jia, C.; et al. Simtuzumab is ineffective for patients with bridging fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis caused by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1140–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratziu, V.; Sanyal, A.; Harrison, S.A.; Wong, V.W.S.; Francque, S.; Goodman, Z.; Aithal, G.P.; Kowdley, K.V.; Seyedkazemi, S.; Fischer, L.; et al. Cenicriviroc treatment for adults with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis: Final analysis of the phase 2b CENTAUR study. Hepatology 2020, 72, 892–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshat, S.Y.; Quiroz, V.M.; Wang, Y.; Tamayo, S.; Doloff, J.C. Liver disease: Induction, progression, immunological mechanisms, and therapeutic interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, M.; Pinzani, M. Liver fibrosis: Pathophysiology, pathogenetic targets and clinical issues. Mol. Aspects Med. 2019, 65, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sheng, X.; Shi, A.; Hu, H.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Fei, L.; Liu, H. β-Glucans: Relationships between Modification, Conformation and Functional Activities. Molecules 2017, 22, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Fang, L.; Guo, C.; Sang, T.; Peng, H.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, S.; Lin, X.; et al. Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide inhibits HSC activation and liver fibrosis via targeting inflammation, apoptosis, cell cycle, and ECM-receptor interaction mediated by TGF-β/Smad signaling. Phytomedicine 2023, 110, 154626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, K.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Wei, Y.; Yang, Y. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide mitigates high-fat-diet-induced skeletal muscle atrophy by promoting AMPK/PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 301, 140488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z.T.; Wu, Z.H.; Wang, C.M.; Xie, X.C.; Wang, Y.H. Astragalus polysaccharide as a potential antitumor immunomodulatory drug (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2025, 32, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Dong, C. Polysaccharides play an anti-fibrotic role by regulating intestinal flora: A review of research progress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 131982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Wang, C.; Dai, X.; Zhou, M.; Gong, L.; Yu, L.; Peng, C.; Li, Y. Phillygenin inhibits LPS-induced activation and inflammation of LX2 cells by TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 248, 112361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, M.; Sang, Y.; Wei, L.; Dai, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. TGF-β inhibitors: The future for prevention and treatment of liver fibrosis? Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1583616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Jia, L.; Xiao, S. Dicliptera chinensis polysaccharides target TGF-β/Smad pathway and inhibit stellate cells activation in rats with dimethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2016, 62, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, K.L.; Huang, S.M.; Cao, H.K.; Zhang, K.F. Effect of Portulaca oleracea polysaccharide on TGF-β1/Smads signaling pathway in dimethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic fibrosis rats. Chin. Pharmacol. Clin. 2016, 32, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, J.Z.; Liang, Y.; Sun, J.-B.; Liu, B.-Q.; Liao, Y. Sagittaria sagittifolia polysaccharide regulates Nrf2-mediated antioxidant to improve apoptosis and ferroptosis in high glucose-induced lens epithelial cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2026, 454, 114841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, X.; Zhu, H.; Chen, R.; Zhang, S.; Chen, G.; Jian, Z. Nrf2 Regulates Oxidative Stress and Its Role in Cerebral Ischemic Stroke. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Long, D.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Liang, Y.; Wan, L.; Zhang, J.; Xue, F.; Feng, L. Oxidative stress-mediated mitochondrial fission promotes hepatic stellate cell activation via stimulating oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qi, J.Y.; Jin, Y.C.; Wang, X.S.; Yang, L.; Lu, L.; Yue, J.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Song, D.; et al. Ruscogenin Exerts Anxiolytic-Like Effect via Microglial NF-κB/MAPKs/NLRP3 Signaling Pathways in Mouse Model of Chronic Inflammatory Pain. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 5417–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, R.; Liu, R. Natural products in licorice for the therapy of liver diseases: Progress and future opportunities. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 144, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fareed, M.M.; Khalid, H.; Khalid, S.; Shityakov, S. Deciphering Molecular Mechanisms of Carbon Tetrachloride- Induced Hepatotoxicity: A Brief Systematic Review. Curr. Mol. Med. 2024, 24, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.X.; He, Y.L.; Huang, D.; Tang, D.X.; Wang, M.; Wang, F. Effect of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide on expression of TGF-β1, α-SMA, type I and type III collagen in hepatic fibrosis rats. Chin. J. Gerontol. 2022, 42, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, P.Y.; Zheng, W.H.; Li, W.; Shan, T.Y.; Han, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z.T.; Liu, H.P.; Niu, S.Y.; Jia, X.Y. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide inhibits expression of α-SMA and type I collagen in liver fibrosis tissue of mice. Occup. Health 2020, 36, 752–756. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Li, D.; Li, M.; Liu, L.; Deng, B.; Jia, L.; Yang, F. Coprinus comatus polysaccharides ameliorated carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis through modulating inflammation and apoptosis. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 11125–11141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Kuang, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Kang, T. A polysaccharide from Codonopsis pilosula roots attenuates carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis via modulation of TLR4/NF-κB and TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 119, 110180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhan, F.; Zhang, J. Effect of Astragalus polysaccharide on TGF-β1/Smads signaling pathway in hepatic fibrosis rats. Chin. J. Chin. Med. 2015, 30, 2184–2186. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Moellering, R.E.; Cravatt, B.F. How chemoproteomics can enable drug discovery and development. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schulz, K.F.; Chalmers, I.; Hayes, R.J.; Altman, D.G. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995, 273, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, K.S.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Mokrysz, C.; Nosek, B.A.; Flint, J.; Robinson, E.S.J.; Munafò, M.R. Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perel, P.; Roberts, I.; Sena, E.; Wheble, P.; Briscoe, C.; Sandercock, P.; Macleod, M.; Mignini, L.E.; Jayaram, P.; Khan, K.S. Comparison of treatment effects between animal experiments and clinical trials: Systematic review. BMJ 2007, 334, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.B.; Jacob, S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2016, 7, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reagan-Shaw, S.; Nihal, M.; Ahmad, N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Estimating the Maximum Safe Starting Dose in Initial Clinical Trials for Therapeutics in Adult Healthy Volunteers; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2005.

- Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Shikov, A.N.; Faustova, N.M.; Obluchinskaya, E.D.; Kosman, V.M.; Vuorela, H.; Makarov, V.G. Pharmacokinetic and Tissue Distribution of Fucoidan from Fucus vesiculosus after Oral Administration to Rats. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA Guidance for Industry: Waiver of In Vivo Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Studies for Immediate-Release Solid Oral Dosage Forms Based on a Biopharmaceutics Classification System. 2017. Available online: https://www.gmp-compliance.org/guidelines/gmp-guideline/fda-guidance-for-industry-waiver-of-in-vivo-bioavailability-and-bioequivalence-studies-for-immediate-release-soloral-dosage-form (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Rowland, M.; Tozer, T.N. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics: Concepts and Applications, 5th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer Business: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bataller, R.; Brenner, D.A. Liver fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, T.; Friedman, S.L. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstee, Q.M.; Reeves, H.L.; Kotsiliti, E.; Govaere, O.; Heikenwalder, M. From NASH to HCC: Current concepts and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Xing, F.; Huo, J.; Fung, M.L.; Liong, E.C.; Ching, Y.P.; Xu, A.; Chang, R.C.C.; So, K.F.; Tipoe, G.L. Lycium barbarum polysaccharides therapeutically improve hepatic functions in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis rats and cellular steatosis model. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Kong, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Niu, J. Antioxidant and hepatic fibrosis-alleviating effects of selenium-modified Bletilla striata polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 301, 140234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, S.; Itoh, A.; Isoda, K.; Kondoh, M.; Kawase, M.; Yagi, K. Fucoidan partly prevents CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 580, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huch, M.; Gehart, H.; van Boxtel, R.; Hamer, K.; Blokzijl, F.; Verstegen, M.M.; Ellis, E.; van Wenum, M.; Fuchs, S.A.; de Ligt, J.; et al. Long-term culture of genome-stable bipotent stem cells from adult human liver. Cell 2015, 160, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broutier, L.; Mastrogiovanni, G.; Verstegen, M.M.; Francies, H.E.; Gavarró, L.M.; Bradshaw, C.R.; Allen, G.E.; Arnes-Benito, R.; Sidorova, O.; Gaspersz, M.P.; et al. Human primary liver cancer-derived organoid cultures for disease modeling and drug screening. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.