Abstract

Conventional polycarboxylate superplasticizers (PCEs) suffer from uncontrollable adsorption, characterized by rapid initial uptake and limited subsequent release, which causes pronounced slump loss, particularly at elevated temperatures where hydration accelerates and dispersion efficiency declines. To overcome these limitations, we developed a series of chitosan-based upper critical solution temperature (UCST) responsive superplasticizers (Thermo-PCEx, UCST = 40–42 °C) capable of temperature -adaptive dispersion during cement hydration. A vinyl-functionalized chitosan macromonomer (uCS-g-T8) was synthesized by reacting cetyl polyoxyethylene glycidyl ether with chitosan, followed by methacrylate modification, and then copolymerized with acrylic acid and isopentenol polyoxyethylene ether to yield Thermo-PCEx with tunable sugar-to-acid ratios. The polymers exhibited clear UCST-type phase-transition behavior in aqueous solution. When incorporated into cement paste, Thermo-PCEx enabled continuous fluidity enhancement at 25 °C (<UCST), with increases of 43.6%, 52.9%, 62.3% and 63.6%, after 180 min for x = 0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2, respectively. Adjusting dosage and composition further regulated setting time, improved rheological stability, and enhanced mechanical strength. These findings demonstrate a viable pathway for designing bio-based, temperature-responsive superplasticizers with self-adaptive dispersibility for sustainable cement technologies.

1. Introduction

Cement-based materials are extensively used in modern engineering, and their performance largely depends on the kinetics of the hydration process. Excessive heat release and the accompanying loss of fluidity may induce thermal stress or cement cracking [1,2,3]. Water-reducers are therefore employed as an indispensable ingredient of modern type concretes, to reduce water-to-cement (w/c) ratio, regulate rheological behavior and hydration dynamics of the cement systems [4,5,6]. Comparative performance with the lignosulfonate and sulfonated naphthalene formaldehyde based superplasticizers, comb-like polycarboxylate superplasticizers (PCEs) have become the most prominent owing to their special advantages: (1) lower doping amount for higher water reducing rate (>25%) and higher plasticizing effect [7,8]; (2) effectively prevent slump loss without causing obvious retardation of concrete and the compressive strength improved [9,10]; (3) and molecular design flexibility [11,12,13,14]. PCEs disperse cement particles through coordination between anchoring groups and Ca2+ ions [15,16,17], while polyether side chains provide steric hindrance to prevent flocculation of particles in the liquid phase [18,19,20,21]. Nevertheless, conventional PCEs exhibit limited controllability in their adsorption behavior: they adsorb rapidly at the early stage but release insufficiently during later hydration, resulting in a pronounced time-dependent slump loss [22,23,24]. Importantly, this drawback indicates that the key limitation of modern PCEs has shifted from insufficient dispersing capability to the lack of controllable, time-dependent adsorption–release behavior during cement hydration [25]. Moreover, elevated temperatures accelerate hydration reactions, weaken the dispersing effect of PCEs, and further deteriorate rheological properties of the mixture [26,27,28]. This temperature sensitivity makes it particularly challenging to maintain workability in hot-weather concreting and mass concrete applications.

Thermo-responsive polymers, which can reversibly adjust their aggregation state as well as solubility in response to temperature changes, offer a promising strategy for developing adaptive superplasticizers [29,30]. According to their phase-transition behavior, these polymers are generally categorized into lower critical solution temperature (LCST) and upper critical solution temperature (UCST) types [31,32]. Most previously reported thermo-responsive polymers for cement-related applications are based on LCST behavior, in which polymer chains tend to aggregate upon heating [32,33]. However, such a response is intrinsically mismatched with the exothermic hydration process of cement, where enhanced dispersion rather than phase separation is required as temperature rises. In contrast, UCST-type polymers become more soluble upon heating, which aligns well with the “heat evolution-temperature rise” process during cement hydration [34]. Incorporating UCST-type segments into PCE structures, therefore, provides a rational pathway to achieve temperature-adaptive adsorption and release, enabling delayed dispersion at early stages and enhanced dispersibility during later hydration. Chitosan (CS), a naturally abundant polysaccharide rich in amino and hydroxyl groups, provides a sustainable and chemically versatile platform for constructing UCST-type polymers through controlled tuning of hydrophilic–hydrophobic balance [35]. In addition to its renewability, the multiple functional groups of chitosan allow for strong interactions with metal ions and hydration products [36,37], while its polysaccharide backbone enables precise modulation of intermolecular interactions governing UCST behavior. These features make chitosan particularly attractive for designing bio-based, thermo-responsive superplasticizers that can operate reliably in the highly alkaline and ion-rich cement environment.

In this work, we grafted tetradecyl polyoxyethylene ether onto chitosan to obtain UCST-type chitosan derivatives (CS-g-T8), followed by introducing polymerizable double bonds to prepare chitosan macromonomers (uCS-g-T8). Then macromonomers were copolymerized with acrylic acid and polyether monomers to synthesize a series of chitosan-based upper critical thermo-responsive polycarboxylate superplasticizers (Thermo-PCEx, x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2). Distinct from conventional PCEs and previously reported LCST-type systems, the designed Thermo-PCEx aims to achieve controllable, temperature-triggered dispersion behavior that is synchronized with the hydration-induced temperature evolution of cement. The thermo-responsive solubility, dispersing performance, and influence of Thermo-PCEx on cement paste fluidity, setting behavior, and mechanical strength were investigated. The results demonstrate that Thermo-PCEx can adaptively respond to temperature rises during hydration, maintaining excellent dispersion and slump retention. This study highlights a sustainable and intelligent design strategy for bio-based, temperature-adaptive superplasticizers with controllable adsorption–release behavior for high-performance cement-based materials.

2. Materials and Synthesis

2.1. Materials

Tetradecyl polyoxyethylene ether alcohol (C14H29O-(CH2CH2O)8-H, abbreviated as T8-OH) and isopentenol polyoxyethylene ether (TPEG, Mn = 2400) were obtained from Haian Petrochemical (Haian, China) and Fujia Fine Chemicals Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), respectively. Water-soluble chitosan (CS, η = 25 mPa·s, DD = 90%) was supplied by Weifang Haizhiyuan Bioproducts Co., Ltd. (Weifang, China). Ammonia-ammonium chloride buffer (pH 10), sodium hydride (NaH, 60% purity), dichloromethane (DCM), epichlorohydrin (ECH), toluene, glycidyl methacrylate (GMA), isopropanol (i-PrOH), acrylic acid (AA), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), ascorbic acid, and thioglycolic acid (TGA) were of analytical grade and purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). AA and GMA were purified by passing through a neutral alumina column to remove inhibitors. The cement used was P·I 42.5 ordinary Portland cement supplied by China United Cement Co., Ltd. (CUCC, Xuzhou, China). Its main chemical composition is listed in Table S1 (Supporting Information). Natural sand (fineness modulus 2.8, apparent density 2630 kg m−3, bulk density 1500 kg m−3) was provided by Zhongtai Concrete Development Co., Ltd. (Quanzhou, China).

2.2. Instrumentation and Measurements

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz spectrometer using CD3Cl or D2O as the solvent. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were obtained using a Nicolet Nexus TM-470 spectrometer in attenuated total reflection (ATR) mode over the range of 4000–400 cm−1 at 25 °C. The thermo-responsive phase transition behavior of chitosan-based copolymers in aqueous solution was characterized using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-2600; Shimadu Enterprise Management, Shanghai, China) equipped with a temperature-controlled water bath. Transmittance at 650 nm was recorded while heating from 25 to 60 °C at 0.5 °C min−1, with a 2 min equilibration at each step. The upper critical solution temperature (UCST) was determined from the onset of turbidity upon cooling and the point of transparency upon heating. Cement paste samples were cured for 2 min, 1 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h, and hydration was terminated by immersing them in absolute ethanol. Then the samples were vacuum-dried at 40 °C over P2O5 to constant weight, ground to powder, and analyzed by X-ray diffraction (Smart/SmarLa diffractometer, CuKα, λ = 1.5418 Å; Rigaku Corp. Akishiima-shi, Japan) in the 2θ range of 5–70° at a scan rate of 8° min−1. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis was performed using an S-3500N tungsten filament emission (Hitachi, Hitachinaka, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan), operating at 15 kV and 1.33 × 10−2 Pa. The samples were pieces vacuum-dried at 40 °C over P2O5, picked randomly and coated with gold by sputter under vacuum.

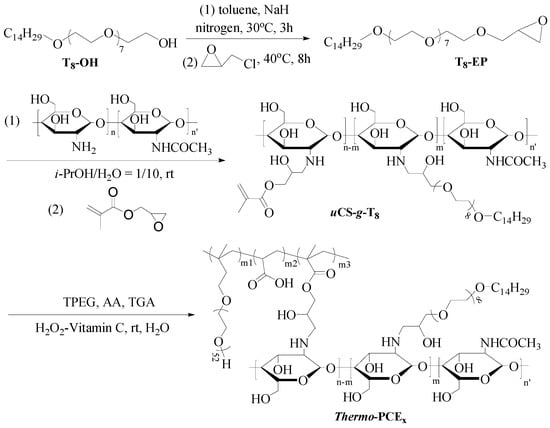

2.3. Synthesis of Chitosan-Based Thermo-Responsive Superplasticizers (Thermo-PCEx)

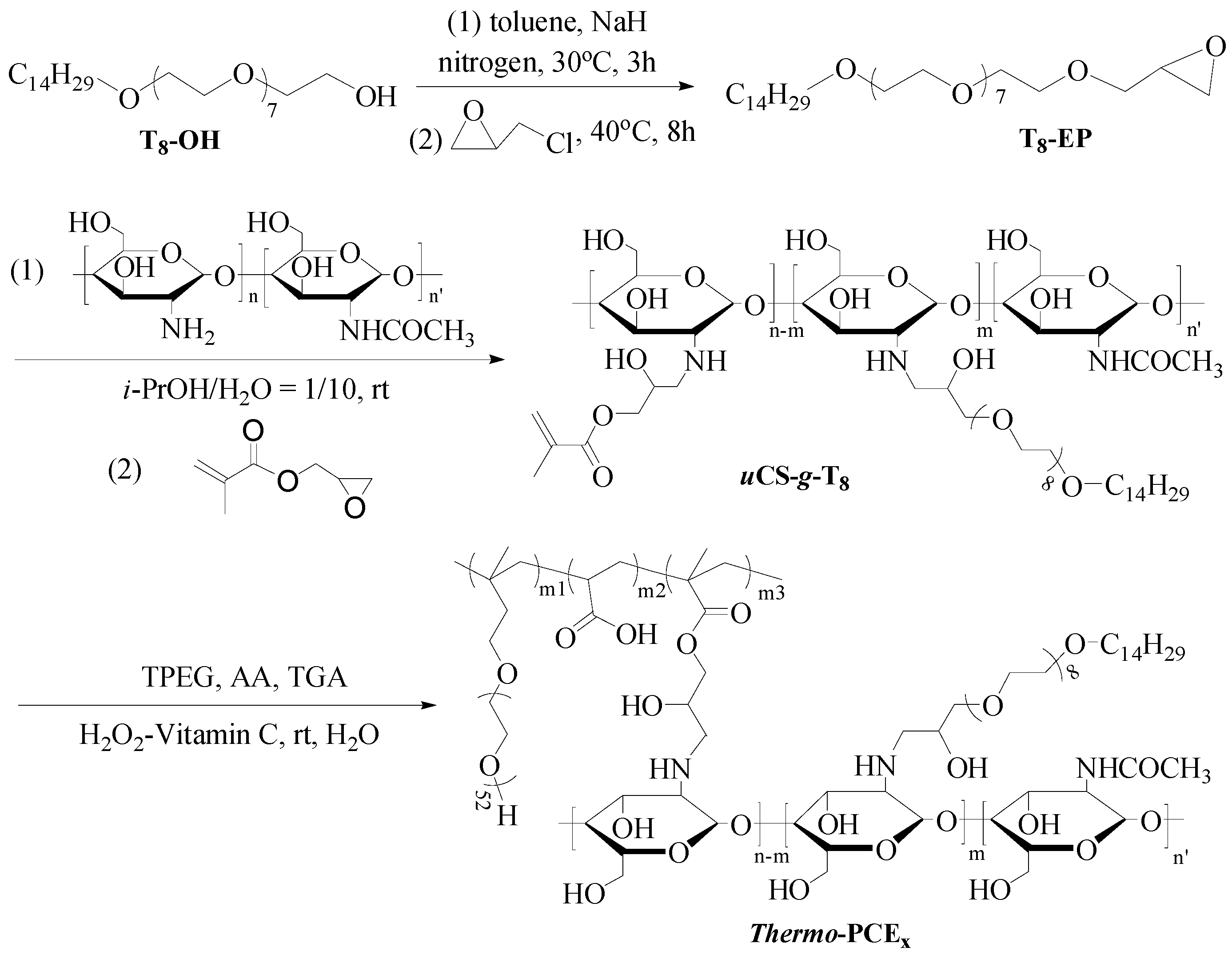

Thermo-PCEx were synthesized as illustrated in Scheme 1 through a four-step process (Thermo-PCE0 corresponding to conventional PCE, synthesized directly without chitosan-based monomers; and x denotes the chitosan-based units-to-acid mass ratio (WCS/WAA)).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Thermo-PCEx, x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2.

- (1)

- Synthesis of tetradecyl poly(ethylene glycol) glycidyl ether (T8-EP) [38]

Under N2 atmosphere, 50.0 g of tetradecyl poly(ethylene glycol) alcohol and 200 mL toluene were dehydrated azeotropically at 140 °C. After cooling to 40 °C, 5.2 g NaH (0.13 mol) was added and reacted for 3 h, followed by dropwise addition of 18.5 g epichlorohydrin (0.2 mol). The mixture was stirred for 12 h, filtered, concentrated by rotary evaporation, re-dissolved in DCM, washed three times with an equal volume of deionized water, evaporated and vacuum-dried to obtain a yellowish product, T8-EP.

- (2)

- Synthesis of thermo-responsive chitosan macromonomers (uCS-g-T8) [39]

T8-EP (18.6 g) was dissolved in a mixed solution of 100 mL with a volume ratio of isopropanol-to-water of 1/10, and a 2 wt% chitosan solution (10 g CS) was added dropwise under stirring at 30 °C for 3 days. The product solution was filtered, concentrated, dialyzed (MW cutoff = 1000), and freeze-dried to yield tetradecyl poly(ethylene glycol) glycidyl ether grafted chitosan (CS-g-T8). Subsequently, 28.6 g of obtained CS-g-T8 and 1.6 g of glycidyl methacrylate (GMA) were reacted in 500 mL of water for 48 h to synthesize chitosan macromonomers uCS-g-T8.

- (3)

- Copolymerization to obtain Thermo-PCEx

Acrylic acid (AA), isoprenyloxy poly(ethylene glycol) ether (TPEG), thioglycolic acid (TGA, 0.2 g), and deionized water were mixed in a three-neck flask with a constant mass ratio of WAA/WTPEG = 2.88/24. Different amounts of uCS-g-T8 were induced to adjust the chitosan-based repeat units/acid mass ratio WCS/WAA = x (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2). The copolymerization was initiated by dropwise adding H2O2 and ascorbic acid (3 ‰ and 1 ‰ of total monomer mass, respectively) and proceeded for 3 h. The synthesized copolymers were adjusted to 10 wt% solutions for subsequent testing.

2.4. Preparation of Cement Composites

Cement pastes were prepared according to GB/T 8077-2012 with a water-to-cement ratio (w/c) of 0.29 [40]. Concrete mixtures were formulated following GB/T 50080-2016 with cement/sand/stone/fly ash/slag/water = 164/850/997/83/83/165 [41]. The dosage of PCE or Thermo-PCEx was 5% by weight of cement. Cubic specimens (100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm) were cured at 20 ± 1 °C and 95% relative humidity for 24 h, demolded and stored under the same conditions until testing.

2.5. Evaluation of Thermo-PCEx Performance in Cement

The fluidity of cement pastes was determined following GB/T 8077-2012. Thermo-PCEx, 87 g of water, and 300 g of cement (preheated at 25 or 50 °C for 40 min) were mixed at low speed for 1 min and high speed for 1 min. The mixture was poured into a truncated cone (height = 60 mm; top = 36 mm; bottom = 60 mm) and lifted vertically to measure the spread. Each test was performed twice at right angles, and the average values at 0, 60, 120, and 180 min were recorded as F0 and Ft. The relative variation in fluidity was calculated as (Ft − F0)/F0 × 100%. Setting times were measured according to GB/T 1346-2011 using a Vicat apparatus [42]. The initial setting was defined when the needle was 4 ± 1 mm from the base, and the final setting when the penetration depth was 0.5 mm. The compressive strength of concrete for 7 d and 28 d was tested using a DYE-300S concrete strength test instrument (Rongjida Instrument Tech. Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) according to GB/T50107-2010 [43]. Three samples of each concrete were tested and the results were averaged.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization

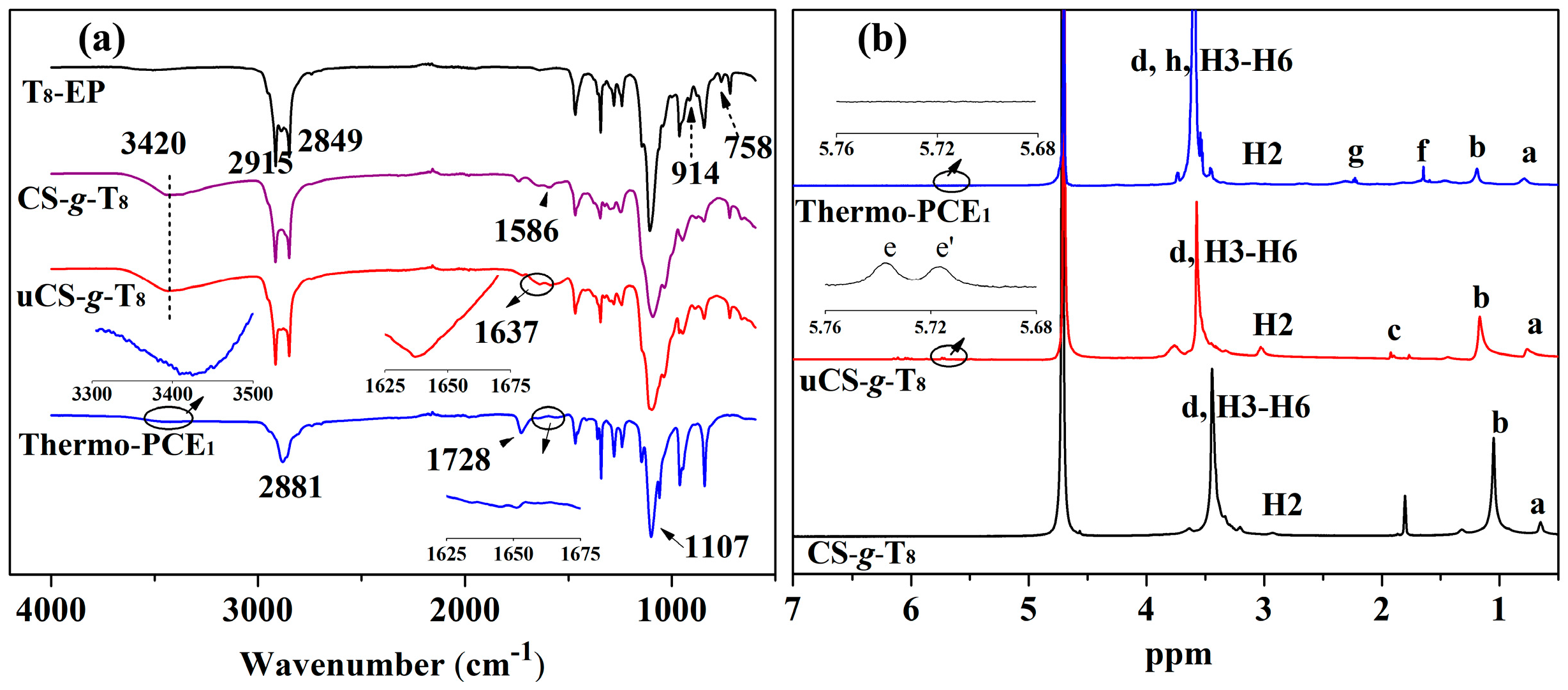

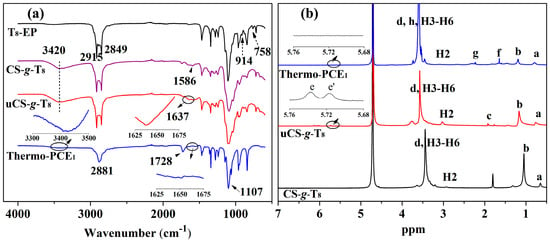

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to monitor the structural evolution. As shown in Figure 1a, T8-EP exhibits characteristic epoxy absorptions at 914 and 758 cm−1. These bands disappear completely in CS-g-T8, while new signals emerge at 1586 cm−1 (in-plane N–H bending) and 3420 cm−1 (overlapping –NH2/–OH stretching), confirming the epoxy ring-opening reaction with chitosan. Upon introducing methacrylate groups, uCS-g-T8 shows an additional C=C stretching band at 1637 cm−1. After free-radical copolymerization, this C=C band is no longer observed in Thermo-PCE1, and new absorptions at 1728 cm−1 (C=O from acrylic acid) and 1107 cm−1 (ether linkages) appear. These spectral changes corroborate the reaction pathway proposed in Scheme 1.

Figure 1.

(a) FTIR analysis of T8-EP, CS-g-T8, uCS-g-T8 and Thermo-PCE1. (b) 1H NMR spectra of T8-EP, CS-g-T8, uCS-g-T8 and Thermo-PCE1.

The structures were further validated using 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 1b). Peaks a, b, and d at 0.90, 1.27, and 3.65 ppm correspond to the H signal of –CH3, –CH2–, and –CH2CH2O– segment. For the macromonomer uCS-g-T8, vinyl H and -CH3 links to vinyl resonances appear at e, e′ and c (5.72, 5.74 and 1.78 ppm) with an integral ratio of approximately 1:1:3, confirming the successful incorporation of methacrylate groups. Signals at 2.89 ppm (H2) and 3.11–4.15 ppm (H3–H6) arise from the H signal on the chitosan pyranose ring. In Thermo-PCE1, the disappearance of vinyl peaks and the appearance of new resonances at 1.65 ppm (f) and 2.23 ppm (g), attributable to H on the copolymer backbone, indicate complete consumption of double bonds. The strengthened ether-segment signal further supports successful copolymerization. Taken together, the FTIR and 1H NMR analyses unequivocally confirm the successful synthesis of the chitosan-based UCST-type superplasticizers.

3.2. Thermo-Responsive Behavior of Thermo-PCEx

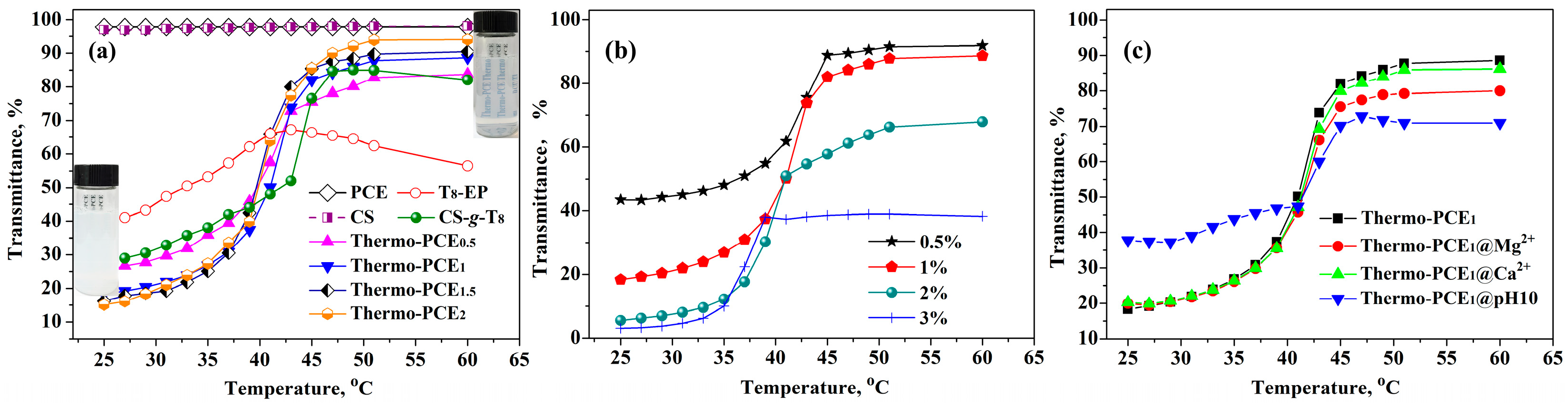

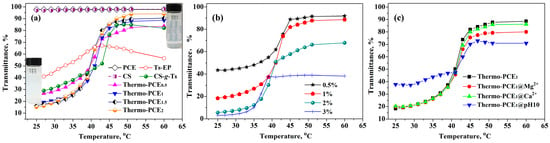

The thermo-responsive properties of Thermo-PCEx and its precursors are shown in Figure 2a. Transmittance of conventional PCE with temperature is essentially identical to that of the CS solution: both maintained above 97% and exhibited no temperature-dependent change, confirming their non-responsive nature. The amphiphilic precursor T8-EP displayed a non-monotonic transmittance variation with a temperature increase, indicating the absence of a critical dissolution behavior. In contrast, Thermo-PCEx solutions exhibited a distinct UCST transition. As the chitosan-based units-to-acid ratio (WCS/WAA) increased from 0 to 2, transmittance decreased at low temperature (T < UCST) and increased at high temperature range (T > UCST), while the UCST remained nearly constant at 40–42 °C. This suggests that the UCST of chitosan-based Thermo-PCEx is mainly governed by the hydrophobic alkyl segments rather than hydrogen bonding between chitosan chains.

Figure 2.

UCST-type thermo-responsive behavior of Thermo-PCEx. (a) Temperature dependence of transmittance for Thermo-PCEx and its precursor solutions; (b) Effect of Thermo-PCE1 solution concentration on transmittance; (c) Influence of ionic species and pH on the transmittance of Thermo-PCE1 solutions. (Unless otherwise specified, the concentration is 1 wt%).

As shown in Figure 2b, the concentration effect on the thermo-responsiveness of Thermo-PCE1 was further investigated. With concentration increasing from 0.5% to 3%, initial transmittance (T < UCST) dropped from 43.5% to 3.1%, implying that stronger chain entanglement and network formation are favored in concentrated solutions. Meanwhile, the UCST decreased slightly from 41 to 37 °C, opposite to trends reported for UCST-like thermo-responsive polymers. This anomaly is likely due to enhanced hydrogen bonding among chitosan hydroxyl groups, which may mitigate hydrophobic aggregation and facilitate dispersion at higher temperatures.

Considering the alkaline and metal-ion-rich environment of cement pastes, the thermo-responsiveness of Thermo-PCE1 was also evaluated in 0.05 M CaCl2, 0.05 M MgCl2, and a pH 10 NH3-NH4Cl buffer to simulate the paste environment (Figure 2c). The UCST behavior remained largely unaffected by Ca2+, Mg2+, or basic conditions. However, at pH = 10 and T < UCST, higher transmittance was observed, attributed to deprotonation of –NH3+ groups that weaken the interactions existing between –COO−/+H3N–. Remarkably, the persistence of UCST behavior under alkaline and ionic environments highlights the strong potential of Thermo-PCEx for practical concrete applications.

3.3. Dispersion Capacities of Thermo-PCEx in Cement Pastes

3.3.1. Effects of Temperature and Hydration Time on Workability

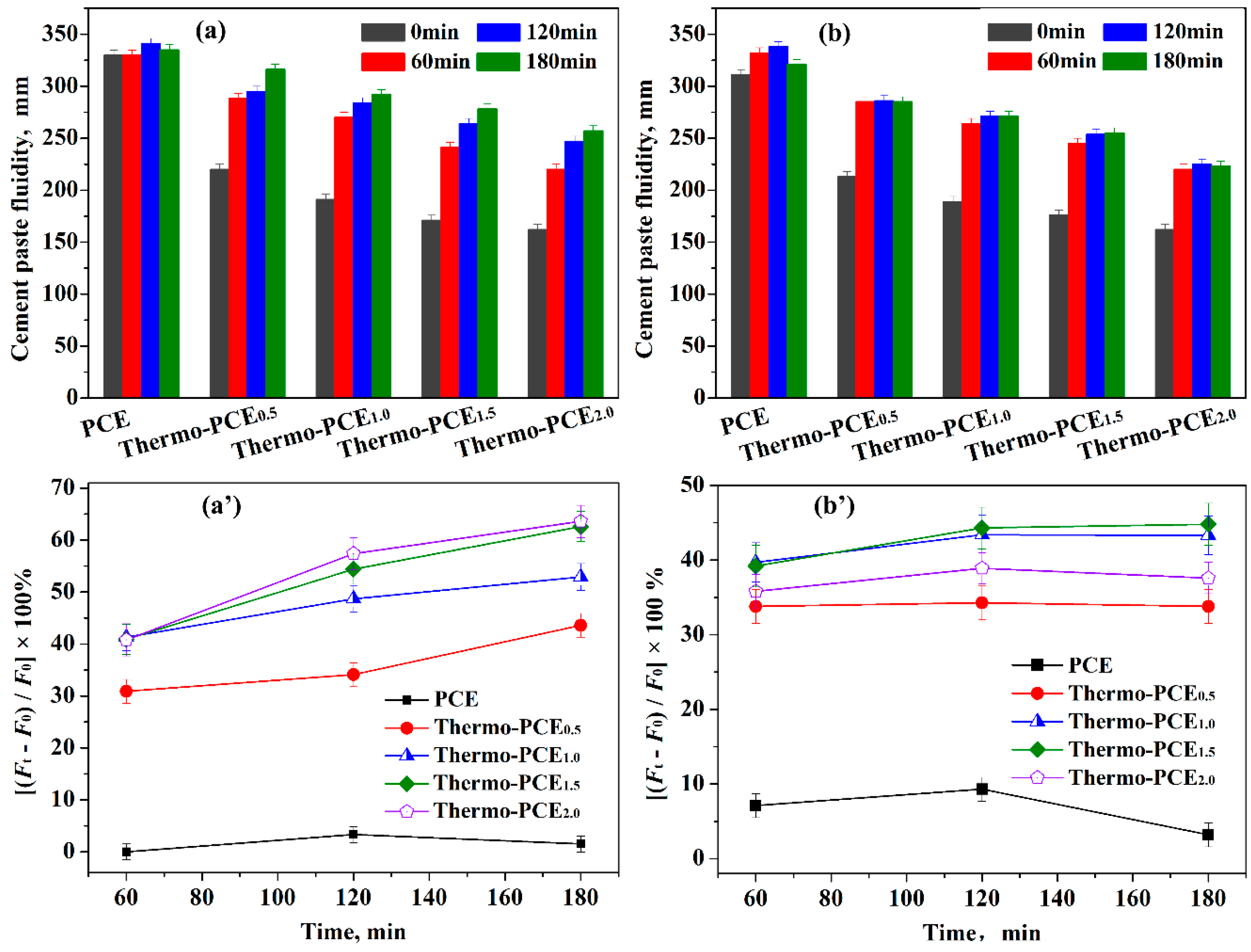

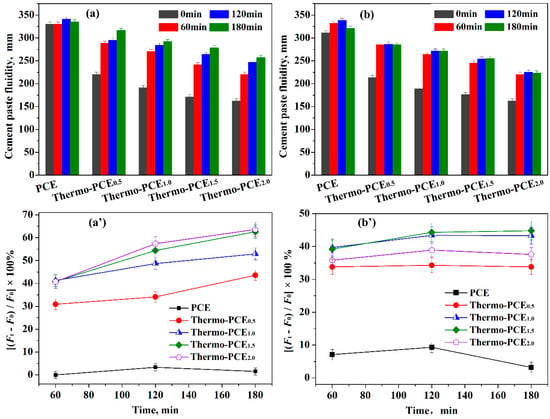

The dispersion performance and retention of Thermo-PCEx in cement pastes were evaluated by measuring the time-dependent flowability at different temperatures. According to GB/T 8077-2012, which specifies that the flowability should be controlled at 180 ± 5 mm, all the additive dosage was set at 5% bwoc, although this is excessive for conventional PCE (2.3% bwoc). At 25 °C (< UCST), the effect of the chitosan-based units acid ratio WCS/WAA on the initial flowability of cement pastes was investigated (Figure 3a). Increasing WCS/WAA from 0 (conventional PCE) to 0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2 led to a decrease in initial flowability from 330 mm to 220, 191, 171 and 162 mm, respectively. This reduction in dispersibility may be attributed to two main factors: (i) the higher chitosan content increases paste viscosity, and (ii) below UCST, Thermo-PCEx molecules cannot effectively anchor onto or adsorb at cement particle surfaces, limiting their initial dispersing efficiency.

Figure 3.

Effect of Thermo-PCEx on paste rheology. (a,a′) Time-dependent flowability and flow change in cement pastes at 25 °C; (b,b′) Time-dependent flowability and flow change in cement pastes at 50 °C. (superplasticizers, 5% bwoc).

The evolution of flowability during hydration was further examined (Figure 3a′). Pastes containing conventional PCE exhibited negligible changes over time, whereas Thermo-PCEx-containing pastes showed a continuous increase in flowability. For WCS/WAA = 0.5, the flowability change rates at 60, 120 and 180 min were 30.9%, 34.1% and 43.6%, respectively; for WCS/WAA = 1.5 and 2, these values increased to 40.9%, 54.4%, 63.6% and 35.8%, 52.5%, 58.6%, respectively. This behavior suggests that hydration-induced temperature rise may trigger the in situ release of Thermo-PCEx within the pore solution, thereby enhancing paste dispersibility over time.

Further evaluation was conducted at T = 50 °C (> UCST) to assess the dispersing performance of Thermo-PCEx in cement pastes. As shown in Figure 3b,b′, when T > UCST, the fluidity increases in the paste containing conventional PCE, reaching only 6.7% after 60 min of hydration. In contrast, pastes incorporating Thermo-PCEx exhibit markedly higher fluidity gains of 33.8%, 43.3%, 44.3% and 35.8% for x = 0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2, respectively. Correspondingly, the initial fluidities of 213, 189, 176 and 162 mm increase to 285, 271, 254 and 220 mm after 60 min. During the subsequent hydration period of 120–180 min, the fluidity remains essentially unchanged. That can be attributed to the fact that above the UCST (50 °C), Thermo-PCEx undergoes rapid phase dissolution and complete release within the first 60 min, enabling prompt adsorption onto cement particle surfaces. Once adsorption is saturated, no further enhancement in dispersibility occurs. In addition, the elevated reaction temperature accelerates the formation of early hydration products, thereby reducing the overall fluidity compared with that measured at 25 °C.

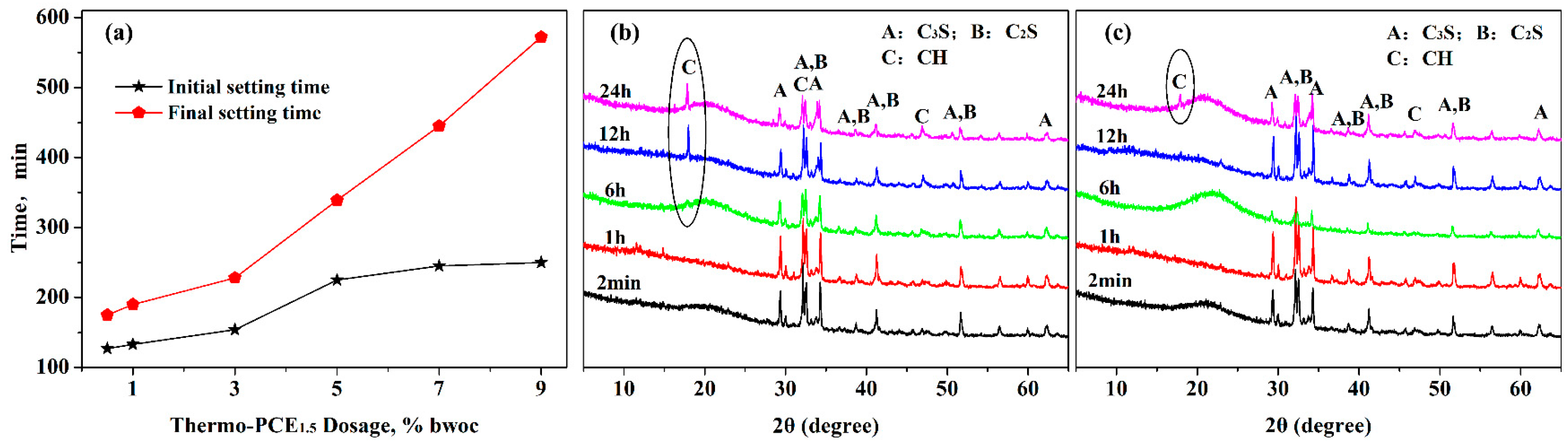

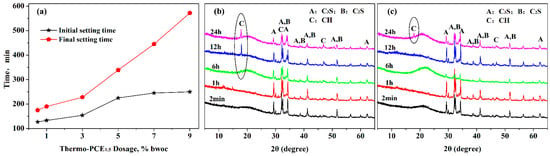

3.3.2. Effects of Thermo-PCE1.5 on Setting Time and Early Hydration Products

Subsequently, the effect of UCST-type superplasticizer on the setting time of cement pastes was investigated, since the setting behavior significantly influences the casting and construction methods of concrete. The impact of Thermo-PCE1.5 dosage on cement paste setting time is shown in Figure 4a. As the dosage of Thermo-PCE1 increased from 0.5% to 9% bwoc, the initial and final setting times were extended from 127 min and 175 min to 250 min and 572 min, respectively, with the prolongation of the final setting time being more pronounced.

Figure 4.

(a) Influence of Thermo-PCE1.5 dosage on the setting time of cement pastes; (b,c) XRD patterns of hydration products at different hydration times for pastes containing conventional PCE and Thermo-PCE1.5, respectively.

The phase evolution of cement pastes containing 2% Thermo-PCE1.5 during hydration was further analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD). As shown in Figure 4b,c, after 6 h of hydration, characteristic diffraction peaks of CH at around 18.0° (001) appeared in pastes with conventional PCE, whereas in pastes containing Thermo-PCE1.5, CH formation was not observed until 24 h, indicating that the hydration of C3S and C2S was suppressed. These XRD results are consistent with the observed trends in setting time, demonstrating that Thermo-PCEx partially retards the hydration rate.

This retardation can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, at the initial stage of mixing, the ambient temperature is typically below UCST (T < UCST), and a portion of Thermo-PCEx not adsorbed onto cement particle surfaces exists in micellar form dispersed in the paste. As hydration progresses and the paste temperature rises, the upper critical dissolving behavior of Thermo-PCEx is triggered, consuming part of the hydration heat and thus reducing the hydration rate. Secondly, the released Thermo-PCEx can complex with Ca2+ ions through its abundant –COO− and hydroxyl groups and adsorb onto cement particles and newly formed hydration products, limiting the supersaturation of Ca2+ in the system. Additionally, the adsorbed Thermo-PCEx interacts with free water via hydrogen bonding through its chitosan segments, reinforcing the solvation layer around cement particles, which inhibits the diffusion of water molecules toward C3S and C2S [44]. Consequently, the crystallization of CH and C-S-H is delayed, resulting in prolonged setting times of the cement paste.

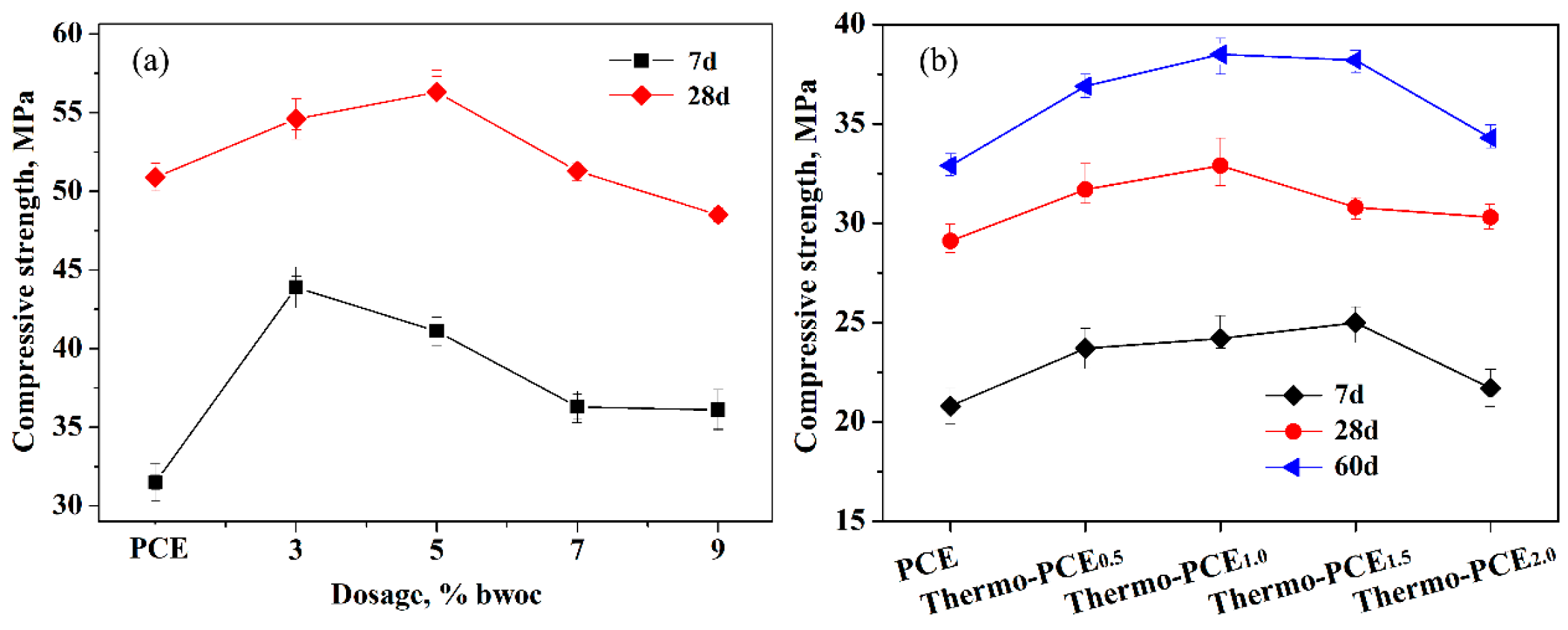

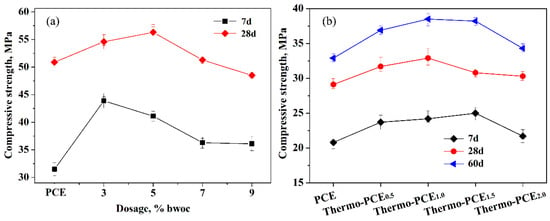

3.4. Application Results of Thermo-PCE1.5 in Cement Composites

As shown in Figure 5a, increasing the dosage of Thermo-PCE1.5 up to 9% bwoc led to enhanced early-age (7 d) compressive strength of cement mortar samples compared to those containing conventional PCE. Within the range of 3–5% bwoc (chitosan units of 0.042–0.069% bwoc), the compressive strengths for 7 d and 28 d reached maximum values of 43.9 MPa and 56.3 MPa, respectively. Even at a high dosage of 9% bwoc, the tested samples still satisfied the requirements of GB/T 8077-2012. Figure 5b illustrates that as the sugar-based units acid ratio WCS/WAA in Thermo-PCEx increased from 0.5 to 2, the compressive strength of concrete initially increased and gained its optimum values of 32.9 and 38.5 MPa, also corresponding to chitosan units of 0.048–0.069% bwoc (Thermo-PCEx, x = 1 and 1.5), then decreased beyond the critical ratio, while all values remained above those of corresponding samples containing conventional PCE.

Figure 5.

(a) Effect of Thermo-PCE1.5 dosage on the compressive strength of cement mortars; (b) Influence of WCS/WAA on the compressive strength of concrete (C30) at a dosage of 5% bwoc.

The existence of a critical dosage for Thermo-PCEx can be ascribed to the excessive adsorption of polymer chains on cement particles and hydration products when the Thermo-PCEx content exceeds the optimal range, leading to the formation of a thick organic layer that impedes clinker phase dissolution and restricts the diffusion of water and ions. This over-adsorption thus retards the hydration of C3S and C2S and delays the formation and densification of C-S-H gel, leading to a reduction in compressive strength [45]. In addition, excessive superplasticizer may increase local heterogeneity in the cement matrix, which further deteriorates the mechanical performance.

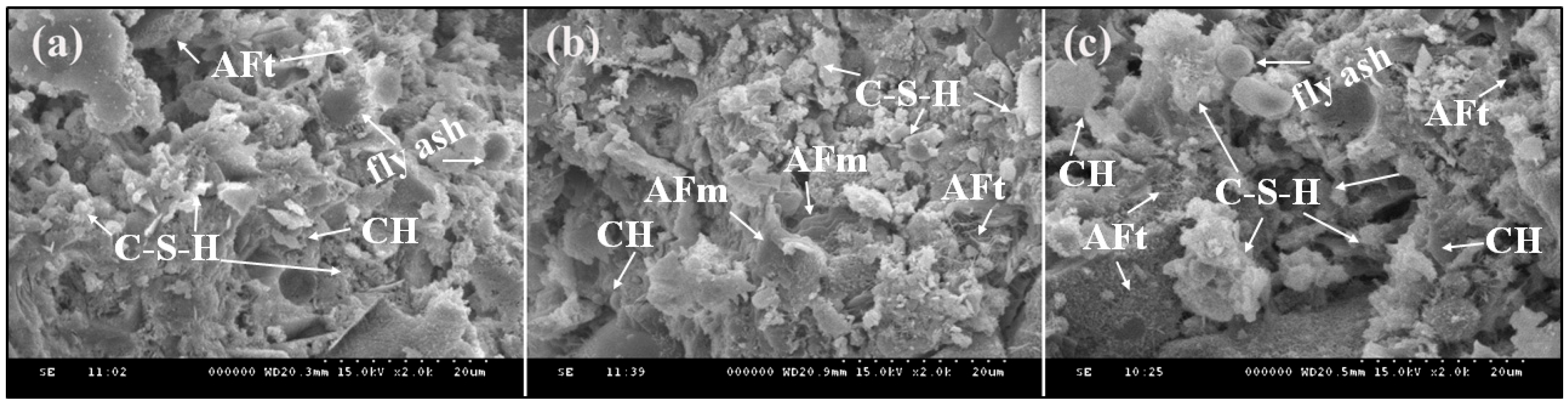

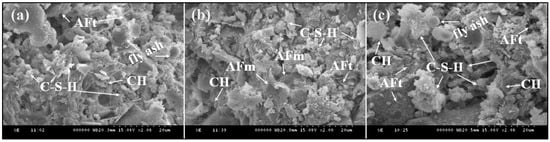

The appearance of a critical WCS/WAA ratio can be attributed to the fact that, when WCS/WAA exceeds a critical level, the strong water-binding capacity and steric hindrance of the chitosan backbone become dominant. This reduces the availability of free water for hydration and weakens the effective anchoring of carboxyl groups onto cement particle surfaces, resulting in less efficient particle packing and delayed hydration. Moreover, excessive polysaccharide segments may partially behave as hydration retarders, similar to conventional sugar-based admixtures [46], thereby suppressing the growth and interconnection of hydration products and leading to decreased compressive strength [47]. This explanation can be further supported by the corresponding SEM images. Figure 6 shows the SEM micrographs of concrete samples doped with PCE, Thermo-PCE1, and Thermo-PCE2 for 7 d, with all dosages fixed at 5% bwoc. The hydration products of the samples mainly consist of ettringite (AFt) crystals, calcium hydroxide (CH) crystals, monosulfate (AFm) crystals, and calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel. When the WCS/WAA ratio is appropriate (Thermo-PCE1), the fracture surface exhibits a dense and compact microstructure, with few small-sized pore defects. Pronounced lamellar and multilayer-stacked AFm aggregates are observed, while the needle-like crystals become less abundant and noticeably thicker (Figure 6b). Such a morphology is typically associated with superior mechanical performance. In contrast, when the WCS/WAA ratio is beyond the optimal level (Thermo-PCE2), the fracture surface becomes relatively loose, with abundant large pore defects. Dense and slender needle-like crystals dominate the microstructure, and the boundaries between different hydration phases are clearly distinguishable (Figure 6c), indicating inferior mechanical performance of the sample.

Figure 6.

SEM images of concrete with different superplasticizers cured for 7 d. (a) PCE; (b) Thermo-PCE1; and (c) Thermo-PCE2; 5% bwoc.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a chitosan-based thermo-responsive superplasticizer (Thermo-PCEx) exhibiting UCST behavior was successfully synthesized via Williamson reaction, hydroxylamine condensation, and free-radical polymerization. FTIR and 1H NMR confirmed the chemical structure, and UV–vis spectroscopy demonstrated the presence of UCST, which was influenced by the citosan-based repeat units-to-acid ratio but remained largely unaffected by Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, NH4+, or strongly alkaline conditions (pH 10). Thermo-PCEx significantly improved the performance of cement paste. When T < UCST, the flowability increased over 180 min from initial values of 220, 191, 171 and 162 mm to 316, 292, 278 and 257 mm for x = 0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2, respectively, due to in situ release triggered by hydration heat. When T > UCST, Thermo-PCEx exhibited markedly higher fluidity, with increases of 33.8%, 43.3%, 44.3% and 35.8% for x = 0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2, respectively. By adjusting the dosage to 3–5% and the sugar-based units-to-acid ratio to 1.5, the corresponding compressive strength reached an optimal value of 43.9 MPa and 56.3 MPa for 7 d and 28 d curing. These findings demonstrate that Thermo-PCEx offers a promising strategy to enhance workability, control setting, and maintain mechanical performance in cement composites, highlighting its potential as a bio-based, temperature-responsive admixture for concrete applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/polysaccharides7010017/s1, Figure S1: 1H NMR analysis of Chitosan, T8-OH and T8-EP; Table S1: Chemical Composition of the Cement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Q.; methodology, Z.Q.; validation, Z.Q., H.Z. and L.Y.; formal analysis, Z.Q., H.Z., L.Y. and S.Z.; investigation, Z.Q., H.Z. and L.Y.; formal analysis, Z.Q., H.Z., L.Y., X.Z. and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Q. and H.C.; writing—review and editing, Z.Q., H.Z. and H.C.; supervision, Z.Q. project administration, Z.Q.; funding acquisition, Z.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research work was financially supported by the Industrial Pilot (Key) Project of Fujian Province (No. 2022H0015). The authors acknowledge the support from the Instrumental Analysis Center of Huaqiao University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the Instrumental Analysis Center of Huaqiao University; Z.Q. sincerely acknowledge the support from Handong Yan and Zhongdong He.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vohburger, A.; Collin, M.; Rindle, O.; Gädt, T. Influence of Polymeric Dispersants on the Dissolution Rate of Tricalcium Silicate and the Nucleation of Calcium-Silicate-Hydrate and Portlandite. Chem. Eur. J. 2025, 31, e202500207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelardi, G.; Mantellato, S.; Marchon, D.; Palacios, M.; Eberhardt, A.B.; Flatt, R.J. 9—Chemistry of chemical admixtures. In Science and Technology of Concrete Admixtures; Woodhead Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 149–218. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Wu, Y.; Lv, H.; Yang, Z. Behavior of hydration heat regulation and quantitative prediction of the early cracking risk of “dual composite” industrial solid waste concrete materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 495, 143685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Bai, Y. Progress in the polycarboxylate superplasticizer and their structure-activity relationship—A review. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Sugamata, T.; Nakanishi, H. Fluidity Performance Evaluation of Cement and Superplasticizer. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2006, 4, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yan, D.; Ke, Y.; Ma, X.; Lai, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; et al. Study on the Effect of Main Chain Molecular Structure on Adsorption, Dispersion, and Hydration of Polycarboxylate Superplasticizers. Materials 2023, 16, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Lu, J.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Stephan, D. Influence of water to cement ratio on the compatibility of polycarboxylate superplasticizer with Portland cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnefeld, F.; Becker, S.; Pakusch, J.; Götz, T. Effects of the molecular architecture of comb-shaped superplasticizers on their performance in cementitious systems. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houst, Y.F.; Bowen, P.; Perche, F.; Kauppi, A.; Borget, P.; Galmiche, L.; Le Meins, J.-F.; Lafuma, F.; Flatt, R.J.; Schober, I.; et al. Design and function of novel superplasticizers for more durable high performance concrete (superplast project). Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Ma, M.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Wu, X. Compatibility between a polycarboxylate superplasticizer and the belite-rich sulfoaluminate cement: Setting time and the hydration properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 51, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Duan, H.; Li, Z.; Jin, Y.; Liu, H.; Pang, Y.; Lou, H.; Yang, D.; Qiu, X. Reconfiguring Molecular Conformation from Comb-Type to Y-Type for Improving Dispersion Performance of Polycarboxylate Superplasticizers. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.; Liu, X.; Song, X.; Guan, J.; Wang, Z.; Cui, S.; Qian, S.; Luo, Q.; Xie, H.; Xia, C. A mechanistic study on the effectiveness of star-like and comb-like polycarboxylate superplasticizers in cement pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 175, 107389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ran, Q.; Liu, J. Preparing hyperbranched polycarboxylate superplasticizers possessing excellent viscosity-reducing performance through in situ redox initialized polymerization method. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 93, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liao, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Huang, J.; Pang, H. Synthesis and characterization of high-performance cross-linked polycarboxylate superplasticizers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 210, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, J.; Sachsenhauser, B. Experimental determination of the effective anionic charge density of polycarboxylate superplasticizers in cement pore solution. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shui, L.; Wang, Y.; Gu, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Peng, L. Effects of PCEs with various carboxylic densities and functional groups on the fluidity and hydration performances of cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 202, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yang, Y.; Shu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Ran, Q.; Liu, J. The binding of calcium ion with different groups of superplasticizers studied by three DFT methods, B3LYP, M06-2X and M06. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 152, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatt, R.J.; Schober, I.; Raphael, E.; Plassard, C.; Lesniewska, E. Conformation of Adsorbed Comb Copolymer Dispersants. Langmuir 2009, 25, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalas, F.; Nonat, A.; Pourchet, S.; Mosquet, M.; Rinaldi, D.; Sabio, S. Tailoring the anionic function and the side chains of comb-like superplasticizers to improve their adsorption. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 67, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.-D.; Feng, L.; Hu, D.-Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z. Effect of side-chain length in polycarboxylic superplasticizer on the early-age performance of cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 211, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalas, F.; Pourchet, S.; Nonat, A.; Rinaldi, D.; Sabio, S.; Mosquet, M. Fluidizing efficiency of comb-like superplasticizers: The effect of the anionic function, the side chain length and the grafting degree. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 71, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Shi, Z.; Lu, Z. Synthesis of novel polymer nano-particles and their interaction with cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 68, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Chan, H.-K. Investigation into the molecular design and plasticizing effectiveness of HPEG-based polycarboxylate superplasticizers in alkali-activated slag. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 136, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Hu, M.; Liu, M.; Pang, J.; Liu, G.; Guo, J. Preparation of a Polycarboxylate Superplasticizer with Different Monomer Regulations and Its Effect on Fluidity, Rheology, and Strength of Cement. Langmuir 2024, 40, 5673–5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, M.; Lai, G.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Cui, S. Effect of competitive hydrolysis of diester in polycarboxylate superplasticizer on the fluidity of cement paste. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 671, 131691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, J.; Winter, C. Competitive adsorption between superplasticizer and retarder molecules on mineral binder surface. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Kong, Y.; Wang, X.; Shui, L.; Wang, H. Influence of Polycarboxylate Superplasticizer on Rheological Behavior in Cement Paste. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2018, 33, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Pang, H.; Wei, D.; Lu, M.; Liao, B. Effect of superplasticizers with different anchor groups on the properties of cementitious systems. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 630, 127207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerde, N.S.; Del Giudice, A.; Zhu, K.; Knudsen, K.D.; Galantini, L.; Schillén, K.; Nyström, B. Synthesis and Characterization of a Thermoresponsive Copolymer with an LCST–UCST-like Behavior and Exhibiting Crystallization. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 31145–31154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloyaux, X.; Fautré, E.; Blin, T.; Purohit, V.; Leprince, J.; Jouenne, T.; Jonas, A.M.; Glinel, K. Temperature-Responsive Polymer Brushes Switching from Bactericidal to Cell-Repellent. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 5024–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Batchelor, R.; Lowe, A.B.; Roth, P.J. Design of Thermoresponsive Polymers with Aqueous LCST, UCST, or Both: Modification of a Reactive Poly(2-vinyl-4,4-dimethylazlactone) Scaffold. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, N.; Yamamoto, M. Design of an LCST–UCST-Like Thermoresponsive Zwitterionic Copolymer. Langmuir 2021, 37, 3261–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, J.; Xie, G.; Zhu, D.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yu, W. Recent Progress on Regulating the LCST of PNIPAM-Based Thermochromic Materials. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phunpee, S.; Ruktanonchai, U.R.; Chirachanchai, S. Tailoring a UCST-LCST-pH Multiresponsive Window through a Single Polymer Complex of Chitosan–Hyaluronic Acid. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 5361–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Zhao, C.; Beaudoin, G.; Zhu, X.X. Synergistic Approaches in the Design and Applications of UCST Polymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2023, 44, 2370058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaf Elnaser, T.A.; Alotaibi, N.F.; Alruwaili, Y.H.; Gomaa, H.; Sharafeldin, H.; Cheira, M.F.; Abdelmonem, H.A.; Abdelrahman, M.S. Dialdehyde Chitosan/Semicarbazide Synthesis for Lanthanum, Cerium, and Neodymium Ions Recovery from Phosphate Leachate. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 6348–6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.D.; dos Santos, H.F.M.; Bonfim, L.F.; Squarisi, I.S.; Esperandim, T.; Marçal, L.; Tavares, D.C.; de Faria, E.H. Impact of Cationic and Neutral Clay Minerals’ Incorporation in Chitosan and Chitosan/PVA Microsphere Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 21189–21205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butsele, K.V.; Stoffelbach, F.; Jérôme, R.; Jérôme, C. Synthesis of Novel Amphiphilic and pH-Sensitive ABC Miktoarm Star Terpolymers. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 5652–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partansky, A.M. A Study of Accelerators for Epoxy-Amine Condensation Reaction. Adv. Chem. 1970, 92, 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 8077-2012; National Standard of the People’s Republic of China, Methods for testing uniformity of concrete admixture. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- GB/T 50080-2016; National Standard of the People’s Republic of China, Standard for test method of performance on ordinary fresh concrete. China Architecture Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2017.

- GB/T 1346-2011; National Standard of the People’s Republic of China, Test methods for water requirement of normal consistency, setting time and soundness of the portland cements. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- GB/T 50107-2010; National Standard of the People’s Republic of China, Standard for evaluation of concrete compressive strength. China Architecture Publishing & Media Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Lv, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, L.; Sun, T. Synthesis of Modified Chitosan Superplasticizer by Amidation and Sulfonation and Its Application Performance and Working Mechanism. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 3908–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Ray, S.; Sarkar, S. Early strength development in concrete using preformed CSH nano crystals. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaji, M.A.; Almustapha, T.; Nagande, U.; Muhammad, M.; Abass, A.I.; Adefemi, A. Effects of sugar as admixture on setting times and compressive strength of concrete. Dutse J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2025, 10, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M.; Barron, A.R. Cement Hydration Inhibition with Sucrose, Tartaric Acid, and Lignosulfonate: Analytical and Spectroscopic Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 7042–7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.