Abstract

Hydrogels based on gelatin–chitosan mixtures have great potential for practical application in the development of new materials in food technology and biomedicine. This study examines the effect of chitosan on the gelling properties, rheological, and structural characteristics of fish gelatin type A hydrogels in the acidic pH range of 3.2–3.9. It was shown that an increase in the chitosan-to-gelatin mass ratio up to 0.15 resulted in a growth in the hydrogel thermal stability and an increase in the elastic modulus, hardness, and yield stress. The structural strength of the fish gelatin–chitosan hydrogel increased due to the strengthening of the binding zones in the fish gelatin gel network in the presence of chitosan. According to scanning electron microscopy, the supramolecular microstructure of the gels demonstrated a significant compaction upon the addition of chitosan to fish gelatin. UV and IR spectroscopy data, as well as changes in zeta potential, showed the formation of supramolecular complexes of fish gelatin with chitosan as a result of hydrophobic interactions between biomacromolecules and the establishment of hydrogen bonds; in this case, electrostatic interactions between macromolecules of fish gelatin and chitosan are practically absent in the acidic pH region. The ability to form supramolecular complexes of different compositions at different mass ratios of polysaccharide-to-fish gelatin makes it possible to obtain hydrogels with high gelling properties, strength, elasticity, and thermal stability comparable to hydrogels of mammalian gelatin.

1. Introduction

Biopolymer gelatin obtained from fish skin—fish gelatin (FG)—is widely used in the food industry [1,2,3] as well as in the pharmaceutical industry and medicine [4,5] as a stabilizer and a structuring and gelling agent. In recent years, the demand for FG as a multifunctional food ingredient has increased sharply in comparison with mammalian gelatin (like bovine and porcine gelatins) due to certain economic, ethnocultural, and epidemiological reasons [6,7].

Gelatin is a product of the destruction of collagen, a fibrillar protein of connective tissue. The amino acid sequence of the gelatin macromolecule is approximately one third glycine, Gly, part of the repeating tripeptide Gly–X–Y, where X is most often proline, Pro, and Y is hydroxyproline, Hyp. Gly–X–Y triads in polypeptide chains play a decisive role in the formation of collagen-like triple helices, determining the ability of gelatin for thermoreversible gelation [8]; this unique ability ensures wide applications for gelatin in various technologies. However, FG (especially from cold water fish species) is characterized by reduced Pro and Hyp content compared to mammalian gelatin [1,6,9]. This causes a number of disadvantages in FG: the low sol–gel transition temperatures of its aqueous systems [10] and low strength and elasticity for hydrogels [11,12,13]. These disadvantages limit the use of gelatin hydrogels in food technologies, since the gel, as a basis for structured food product, must retain its properties (not melt) in the range of room temperatures, while remaining strong enough to ensure the necessary organoleptic properties of the product.

One of the effective ways to improve the physicochemical and rheological properties of FG is to use it in multicomponent systems, for example, in mixtures with polysaccharides [14,15]. In aqueous mixtures that are precursors to hydrogels, the self-assembly of FG–polysaccharide supramolecular complexes occurs [16,17] as a result of intermolecular (non-covalent) interactions—electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic interactions [18,19]. The increase in the rheological characteristics of FG gels with the introduction of complexing polysaccharides is shown by the examples of κ-carrageenan [11,13], sodium alginate [20], gum arabic [12], pectin [11], gellan [13], agar [21], and chitosan [22,23,24].

One of the most promising polysaccharides for modifying FG is the cationic chitosan (Ch) [25]. In addition to the ability to form complexes with gelatin, chitosan has a set of unique properties that are in demand in the food industry: biodegradability, biocompatibility, and non-toxicity, along with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [26]. Chitosan is obtained by carrying out a deacetylation reaction by the alkaline, acid, or enzymatic treatment of chitin; the solubility of chitosan increases with increasing degrees of deacetylation [27]. Chitin, in turn, is the basis of supporting tissues and the external skeleton (cuticle) of arthropods and is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature after cellulose [26,28]. Ch dissolves in a weakly acidic aqueous medium at a pH that is below the isoelectric point of fish gelatin; however, despite the same charge of chitosan and gelatin macromolecules, supramolecular complexes are formed in the aqueous phase [29], mainly as a result of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions [30].

Hydrogels formed by supramolecular complexes of mammalian gelatin with chitosan demonstrate clearly expressed viscoelastic properties, while the rheological properties of hydrogels are largely determined by the colloidal structure of the supramolecular complexes formed in the sol, the gel precursor [31]. The ability to change the rheological properties, including strength and plastic deformation ability, as well as the heat resistance of the fish gelatin–chitosan (FG–Ch) complex hydrogel, are extremely important when using it as a basis for structured food products.

The goal of this work is a comprehensive study of the viscoelastic properties (in the linear and nonlinear regions) of hydrogels obtained from aqueous mixtures of FG with Ch at different polysaccharide-to-gelatin w/w ratios. The concentration of Ch in the mixtures was small, insufficient for the independent gelation of chitosan. We studied the effect of chitosan on the viscoelastic characteristics and thermal stability of the gels. The properties of the products depend on the interaction of the components during the self-assembly of FG–Ch supramolecular complexes. In this work, intermolecular interactions were studied using ultraviolet and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, as well as the dynamic quasi-elastic light scattering method.

The results obtained in this work, describing the rheological and microstructural properties of hydrogels, can serve to solve technological problems, given that gelatin–chitosan hydrogels have great potential for practical use. Thus, reinforced FG–Ch hydrogels can improve the texture, stability, and shelf life of structured food products [2,3]. Recent advances demonstrate the potential for using FG–Ch composites in biodegradable packaging materials with improved antimicrobial and barrier properties [32,33]. FG–Ch hydrogels are finding biomedical applications. They are widely studied as scaffolds for dressings, tissue engineering, and drug delivery due to their biocompatibility and controlled degradation [5,34].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish Gelatin and Chitosan

A sample of fish gelatin (FG) from cold water fish skin Type A was supplied by Sigma–Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). The moisture content was 5.5%, and the total nitrogen (dry residue) was 17.0%. The protein content was 94.4%. The FG isoelectric point, pIFG, of 7.6 was defined by viscometric and turbidimetric methods.

The chitosan (Ch) sample was obtained from shrimp shells and supplied by Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and it was used without additional purification. The degree of deacetylation was 76.2%. The moisture content was 9.8%, the ash (dry residue) was 0.25%, and the total nitrogen (dry residue) was 5.5%.

2.2. Molecular Weight Distribution of Fish Gelatin and Chitosan

The molecular weight of FG and Ch was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography. An LCMS-QP8000 chromatography mass spectrometer (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) was used with a spectrophotometric detector SPD-10AV at 280 nm and a refractive index detector RID-10A. Chromatographic separation was performed using a TSK gel Alpha-4000, 300 × 7.8 mm, and 13 μm column (Tosoh Corp., Tokyo, Japan) at 25 °C in isocratic mode; the eluent was 0.15 M NaCl, with an elution rate of 0.8 cm3/min. To determine the chitosan molecular weight, the column was calibrated using standard pullulans, with weight-average molecular weight, Mw, of 6.2 to 740 kDa, and blue dextran, with Mw = 2000 kDa. To determine the FG molecular weight, the column was calibrated using a set of proteins (cytochrome C, carbonic anhydrase, bovine serum albumin, alcohol dehydrogenase, and β-amylase), with Mw of 12, 29, 66, 150, and 200 kDa, respectively. All column calibration standards were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

The molecular weights of the biopolymer fractions were calculated using the linear dependence (the Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.99) of the eluent volume (cm3) that flowed through the column versus the log Mw (Da). The samples of biopolymers were characterized by a quite narrow molecular weight distribution. The molecular weight was 250 kDa for Ch and 130 kDa for FG.

2.3. Preparation of Fish Gelatin–Chitosan Hydrogels

The aqueous solutions (hydrosols) of FG and Ch were prepared separately. Initially, samples of FG and Ch were swelled in 0.1 M acetic acid at 20 °C for 1 h and 24 h, respectively. The acetic acid solution was used as solvent because an acidic medium is required to dissolve chitosan. Then FG and Ch were dissolved at elevated temperatures, 40 °C and 70 °C, respectively.

After that, the Ch solution was added to the FG solution at a ratio corresponding to required biopolymer concentrations. The pH values of the gelatin–chitosan (FG–Ch) aqueous mixtures were in the range of 3.2–3.9, which is significantly lower than pIFG (7.6). In all the studied systems (solutions and hydrogels), the FG concentration, CFG, was 10 wt%; the Ch concentration, CCh, was varied in the range from 0.3 to 1.5 wt% Therefore, the Ch/FG mass ratio, Z, was varied from 0.03 to 0.15 gCh/gFG. In this pH range, neither phase separation nor coacervation of the mixtures was observed in the studied concentration range. In our previous work, we looked at the study of chitosan–gelatin interaction at the constant gelatin concentration and in the mass ration range of polysaccharide-to-gelatin less than 0.5, Z(gCh/gFG) < 0.5, and at pH from 3.2 to 3.9; it has been shown that, under the above conditions, stoichiometric complexes of composition 0.78 gCh/gFG are formed [29].

The FG hydrogel and FG–Ch hydrogels were obtained by cooling (at 4 °C for 20 h) the FG solution and the FG–Ch aqueous mixtures. The range of chitosan concentrations was chosen such that chitosan alone (in the absence of gelatin) does not form hydrogels at the chosen low Ch concentrations and pH used. Flow curves of chitosan solutions can be fitted with the Ostwald–De Waele power law and in the exponent n, which is close to unity [31]. So, the flow properties of chitosan solutions are rather close to those of Newtonian fluids.

2.4. Rheological Measurements

The rheological measurements of hydrogels from FG and FG–Ch were carried out using a Physica MCR 302 rheometer (Anton Paar GmbH, Graz, Austria) with the cone-and-plate measuring cell (plate diameter: 50 mm, angle: 1°, and 0.100 mm gap). The samples were subject to five protocols. Detailed steps are as follows [35]:

- A frequency sweep (ω of 10−2–102 rad/s) at 1% strain was conducted. Changes in the storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli were measured.

- A strain amplitude sweep (γ of 10−2–103%) at frequency f = 1 Hz was conducted. Values of the storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli were recorded.

- Shearing of the samples in the rate-controlled ( of 10−2–102 s−1) or stress-controlled (σ of 100–103 Pa) regimes was performed. Changes in apparent viscosity (η) were recorded.

- A creep recovery test was carried out at a constant shear stress of 10 Pa from 0 to 900 s (creep phase). The shear stress was removed, and the changes in strain were recorded from 900 to 1800 s (elastic recovery phase).

- A temperature sweep during the gel–sol–gel transition was conducted on hydrogel samples that were prepared at 4 ± 1 °C for 20 h. The gels were placed on a rheometer, then the gels were heated from 4 to 16 °C at a ramp rate of 1 °C/min, and then they were cooled from 16 to −5 °C at a constant shear strain of γ = 1% and a constant frequency of f = 1 Hz. Melting (Tm) and gelling (Tg) temperatures were determined as the temperatures at the crossover of G′ and G″ during the heating and cooling processes, respectively [10].

The experimental protocols (1–4) were performed at 4.00 ± 0.03 °C. The sample temperature control was carried out using the Peltier elements P-PTD200/GL. Each measurement was conducted three times (n = 3, biological replicates).

2.5. Ultraviolet (UV) Absorption Spectra

Ultraviolet (UV) absorption spectra of the investigated aqueous dispersions of the native chitosan, the native FG, and their mixtures were obtained in the 220–255 nm spectral range. Spectrometric measurements were made on a T70 UV/visible spectrometer (PG Instruments Ltd., Leicestershire, United Kingdom) with an accuracy of 0.1 nm; the width of the quartz cuvette was 1 cm; and the measurement temperature was 23 °C. The results were presented as a dependence of the absorbance (A) on the wavelength (λ). Before the measurement was performed, the investigated systems were kept in the cuvette of the spectrometer at the given temperature for 2.5 h. It has been determined that, during this time, the A of all systems in the entire spectral range under study takes equilibrium values.

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectra

FG hydrogel and FG-Ch hydrogel samples were formed at 4 ± 1 °C for 12 h. Then, samples were mixed with KBr powder in a w/w ratio of 1:1 and freeze-dried at −50 °C under 9.8 Pa for 6 h using a FreeZone 6 L freeze dryer (Labconco Corp., Kansas City, MO, USA). Next, the samples were dried at 60 ± 1 °C for 6–8 h to remove residual moisture. Finally, the highly dispersed powder (150 mg) was pressed (under 650 kgf/cm2) into a pellet.

FTIR absorption spectra of hydrogel samples were obtained using the FTIR-spectrometer Shimadzu IR Tracer—100 (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) in the wavenumber range from 1200 cm−1 to 1800 cm−1. The scan number was 250, and the resolution was 0.5 cm−1.

To minimize the effect of moisture, the water vapour spectrum was subtracted from the obtained spectra. To do this, KBr was pressed into a pellet. The obtained pellet was kept in the air for 4 h to absorb water vapour and then scanned to obtain the water vapour spectrum.

2.7. Dynamic Quasi-Elastic Light Scattering (QELS) Measurements

The average hydrodynamic radius R and ζ-potential of particles of the hydrosols under study were found using the QELS method. Finding R is based on the determination of the diffusion coefficient of dispersed particles in the aqueous phase by analyzing the characteristic time of scattered light fluctuations. R is determined from the diffusion coefficient according to the Stokes–Einstein equation.

The ζ-potential was estimated by applying a uniform electric field of constant intensity to the hydrosols under study. The Doppler frequency shift observed in this case is related to the linear velocity of particles’ motion. The ζ-potential is determined from the Helmholtz–Smoluchowski equation based on the magnitude of the electrophoretic mobility of the particles.

A particle size and ζ-potential analyser Photocor Compact-Z (Photocor, Moscow, Russia) with a thermally stabilized semiconductor laser with a wavelength of 636.8 nm and a power of 35 mW was used. The light scattering angle in the mode of R determining was θ = 90° and in the mode of ζ-potential determining was θ = −20°. The measurements were carried out at 23 °C.

2.8. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Measurements

Thermal properties of dried gels were studied using a DZ–DSC300C differential scanning calorimeter (NanJing Dazhan Testing Instruments, Nanjing, China) according to the following protocol. The studied hydrogels were dried in a BK-FD10T freeze dryer (Biobase Group, Jinan, Shandong, China) at a temperature of −60 °C and a residual pressure of no more than 1 Pa for 8 h. Before the experiment, temperature and enthalpy were calibrated using In and Sn at a rate of 5 °C/min. Samples (m = 3–5 mg) were tightly packed on the bottom of an aluminum crucible and hermetically sealed with a cover. The experiment was carried out in a nitrogen atmosphere with a gas supply rate of 25 mL/min according to the following scheme: (1) cooling to 0 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min; (2) holding at 0 °C for 5 min; and (3) heating to 200 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min. An empty crucible with a cover was used as a comparison sample. Each measurement was conducted three times (n = 3, biological replicates).

2.9. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

To study the morphology of gelatin gels, the field emission scanning electron microscope “Merlin” (“Carl Zeiss”, Oberkochen, Germany) was used. Experiments were carried out using gelatin or gelatin/chitosan cryogels prepared in the following manner [36]. Hydrogels were frozen in liquid nitrogen, snapped immediately, and vacuum freeze-dried to obtain xerogels. Prepared cryogels were coated with gold for SEM observations. The morphology was studied at the 15 kV accelerating voltage in the Interdisciplinary Center “Analytical Microscopy” (Kazan Federal University, Kazan, Russia).

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data was presented as mean ± standard deviation. In order to control the measurements’ reproducibility, each measurement was conducted three times (n = 3). The standard deviation values of all measurements were smaller than 10%. Data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the means were compared using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. The confidence level was set at 95% (p < 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS for Windows version 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Gel Viscoelasticity

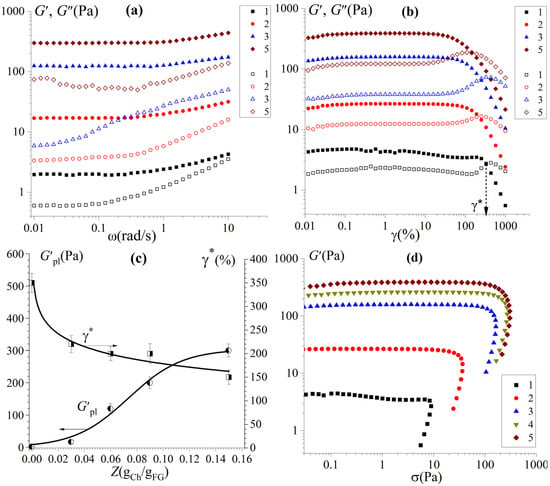

The viscoelastic properties of FG hydrogels and FG–Ch complex hydrogels, obtained in dynamic mechanical analysis mode, are presented in Figure 1a. The frequency dependences of the storage modulus G′(ω) and loss modulus G″(ω) in the linear region of the viscoelastic behaviour of the material (at small strain amplitudes, γ0 = 1%) demonstrate a constant value of the storage modulus G′ (plateau modulus G′pl) over a wide frequency range up to ω ~1 rad/s. In this case, the storage modulus exceeds the loss modulus, G′ > G″, which is characteristic of gels demonstrating solid-like behaviour [35]. The tan values for all samples are lower than 0.15, showing that they have a solid network structure. This is typical for gelatin gels as well as gelatin–polysaccharide complex gels [37].

Figure 1.

Dependencies of the storage modulus G′ (full points) and the loss modulus G″ (open points) (a) on the frequency ω at γ = 1% and (b) on the strain γ at f = 1 Hz; (c) dependencies of the critical strain, γ*, and plateau modulus, G′pl, on Ch-to-FG w/w ratios Z; and (d) stress amplitude sweeps at f = 1 Hz for FG and FG–Ch hydrogels at different chitosan-to-gelatin mass ratios (gCh/gFG): 0 (1), 0.03 (2), 0.06 (3), 0.09 (4), and 0.15 (5).

The rigidity (storage modulus) of the complex hydrogel under conditions where the chitosan concentration is insufficient for independent gelation exceeds the rigidity of the FG gel (Figure 1b,c). This effect increases with increasing polysaccharide content, which is also in accordance with the results of gel strength (see Section 3.2).

The storage modulus G′ was fitted to the power law model:

where the k represents the rigidity coefficient of the hydrogel and m frequency dependence. The results are represented in Table S1 (Supplementary Material). Frequency sweep (Figure 1a) exhibits a characteristic elastic behaviour with slope m, which is much lower than the slope m = 2 expected for a liquid-like behaviour. All hydrogels demonstrate a significant decrease in frequency dependence (from 0.47 to 0.06) as well as rigidity coefficient (from 2 to 390), with an increase in chitosan content up to 1.5%.

For all samples, the highest G′ for high chitosan content in hydrogels could be found, indicating that a denser and more stable intermolecular network structure was formed, and intermolecular bonding was strengthened due to FG–Ch complex formation. Obtained results are consistent with FTIR. This phenomenon is similar to Geng et al. [38], who showed the influence of glycosylation with κ-carrageenan, high methoxyl pectin, and D-Galactose on the rheological properties of FG.

To study the elastic-viscous properties of complex hydrogels beyond the linear regime, the large amplitude oscillatory shear (LAOS) test [39] was used. Figure 1b shows strain amplitude sweeps, also illustrating that the elastic behaviour dominates over the viscous one in the linear viscoelastic range. It should be noted that the FG hydrogel demonstrates linear viscoelastic behaviour in a wide range of strain amplitudes up to approximately 200% (limiting value γL ≈ 200%). With an increasing chitosan-to-gelatin ratio in the complex hydrogel, the linear region becomes shorter and, at Z = 0.15 γL, decreases by an order of magnitude (Figure 1c). The onset of a nonlinear response for gels with increasing deformation is determined by a decrease in the storage modulus and an overshoot of the loss modulus for all samples under study.

The observed spike in G″ is explained by rearrangements of physical bonds in the gel network and their partial destruction at high strains. At some critical value of deformation, γ*, the values of the two moduli are balanced, G′ = G″, which shows the samples behaving at the borderline between being solid-like (gel–like) and liquid [39]. A similar strain sweep response is observed in biopolymer hydrogels including proteins [40], polysaccharides [41], and protein–polysaccharides gels [31], which are more correctly called yielding media (or yielding liquids) [37]. At the same time, a slight decrease in the critical strain, γ*, demonstrated in FG–Ch hydrogels (Figure 1c), means a decrease in stability under vibrational deformation, which is associated with structural changes in FG in complex hydrogels. Figure 1d demonstrates the stress amplitude sweeps and shows the yield stress σY at the limit of the linear viscoelastic range, which logically confirms that the studied gel systems belong to soft matter with a yielding point.

3.2. Yield Stress and Flow Curves

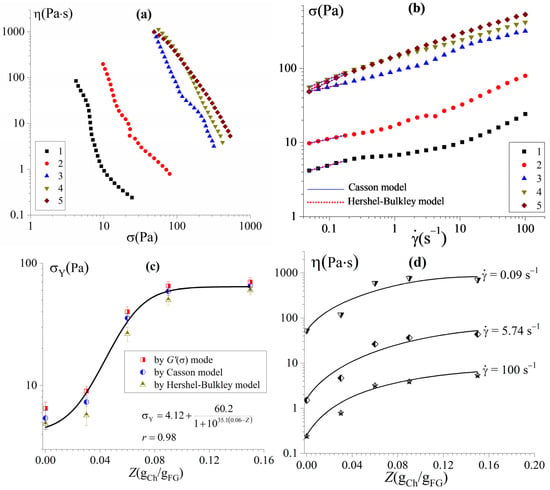

The nonlinear response in the region of high shear stresses exceeding the yield stress, σ > σY, leads to the non-Newtonian flow of the FG–Ch complex hydrogels. Figure 2 shows the flow curves of FG–Ch complex hydrogels obtained in the steady-state flow mode with controlled shear stress, σ (or shear rate, ), presented as η(σ) and σ() in the region above σY. Apparent viscosity, η, decreases by 2–3 orders of magnitude (Figure 2a) when the shear stress increases by approximately 10 times. The shape of the flow curves corresponds to a situation in which the apparent viscosity increases without limit with decreasing shear stress until the transition to a solid state, which is typical for viscoplastic materials [37]. Many protein–polysaccharide hydrogels [10,11,13] and dispersed systems stabilized by protein–polysaccharide complexes [42] have the property of viscoplasticity.

Figure 2.

Flow curves η(τ) (a) and σ() (b) of FG and FG–Ch hydrogels at different chitosan-to-gelatin w/w ratios Z (gCh/gFG): 0 (1), 0.03 (2), 0.06 (3), 0.09 (4), and 0.15 (5); the experimental data (b) are fitted by the Casson and Herschel–Bulkley models. Dependencies of the yield stress σY (c) and the apparent viscosity η (d) on the chitosan-to-gelatin ratios.

The reason for the observed non-Newtonian behaviour in this case (Figure 2) is associated with structural rearrangements of the physical network of the hydrogel and the destruction of non-covalent bonds (ionic bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bonds) [14] between gelatin–polysaccharide complexes in contact zones during shear flow. In this regard, the yield stress, σY, is considered as a strength measure of the gel structure.

The approximation of flow curves (Figure 2b) within the framework of rheological models used to describe viscoplastic disperse systems [35] allows one to estimate the yield stress values of FG–Ch hydrogels; yield stress was calculated according to the Casson and Herschel–Bulkley model and Equations (2) and (3), respectively, as follows:

where σY,C is the Casson yield stress, σY,HB is the Herschel–Bulkley yield stress, ηp is the plastic viscosity, K is a consistency coefficient, and n is the flow index. The calculated correlation coefficient, r, was in the range of 0.97–0.99.

The introduction of chitosan leads to an increase in the yield stress (Figure 2c) and apparent viscosity (Figure 2d) of FG hydrogels. The observed effect is especially pronounced in the region of low chitosan-to-gelatin w/w ratios in the complex FG–Ch hydrogels. Thus, σY increases by more than an order of magnitude as Z increases from 0 to 0.09 gCh/gFG, then changes insignificantly with a further increase in Z up to 0.15 gCh/gFG. The effect of increasing the strength (increased yield stress, Figure 2c) and rigidity (increase in storage modulus, Figure 1) of the FG–polysaccharide hydrogel structure under the complexation of biopolymers [18] is widely used in the food industry, expanding the use of FG in multicomponent systems [43].

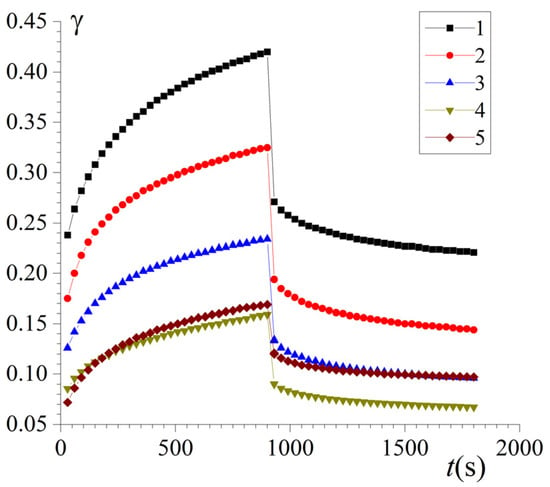

3.3. Creep Sweep

To better understand the rheological properties of FG–Ch hydrogels in the linear region of viscoelastic behaviour, the slow development of deformation in the constant shear stress regime and its subsequent recovery after unloading were studied. Figure 3 shows creep curves at σ0 = 10 Pa and creep recovery curves at σ0 = 0, respectively. The shape of the obtained creep curves of complex hydrogels is typical for real viscoelastic materials [35] and is well described by the Burgers model, combining models for two materials—a Maxwell viscoelastic liquid and a Kelvin–Voigt viscoelastic solid linked in series (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Shear creep at σ0 = 10 Pa and creep recovery at σ0 = 0 curves γ(t) for FG and FG–Ch gels at different chitosan-to-gelatin ratios Z (gCh/gFG): 0 (1), 0.03 (2), 0.06 (3), 0.09 (4), and 0.15 (5).

A complete mathematical description of the development of deformation, γ(t), on the creep curve within the framework of the Burgers model leads to the following equation:

where γ is the shear strain; σ is the shear stress of the creep phase; γ1, γ2, and γ3 are the instantaneous, viscoelastic, and maximum strain, respectively; t and λ are time and retardation time, respectively; η1 is the steady-state viscosity (zero-shear viscosity); G1 is the instantaneous shear modulus; and G2 is the retardation shear modulus.

Processing of experimental curves (Figure 3) within the Burgers model (Equation (4)) was carried out with correlation coefficients of r = 0.97–0.98. The viscoelastic characteristics of FG-Ch hydrogels calculated from the creep curves are presented in the Supplementary Material (Table S2).

Analysis of the data in Table S2 allows us to state an increase in the elastic properties of complex hydrogels with increasing chitosan content; the instantaneous shear modulus G1 increases 3.7 times as Z increases from 0 to 0.15 gCh/gFG. This effect indicates the strengthening of the 3D network of the complex hydrogel, increasing its rigidity and, accordingly, its ability to resist deformation [10]. This is probably due to the strengthening of hydrogen bonds and the formation of additional binding zones. At the same time, the viscoelastic (G2, η2) and purely viscous (η1) components of the rheological behaviour are associated, respectively, with the reversible and irreversible rearrangement of the structural elements of the 3D hydrogel network, and they are most clearly manifested and reach their highest values at Z = 0.09 gCh/gFG, which indicates a modification of the viscous component of the complex hydrogel.

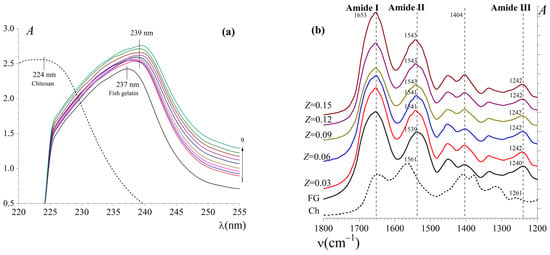

3.4. Fish Gelatin–Chitosan Complexes in Aqueous Phase

The composition of supramolecular complexes formed as a result of the intermolecular interactions of gelatin with chitosan in an aqueous solution—a hydrogel precursor, significantly affecting the rheological properties of complex hydrogels. Information about intermolecular non-covalent interactions of biopolymers was obtained by UV and FT-IR spectroscopy, as well as by the QELS method. UV absorption spectra [A(λ)] of the hydrosols of FG and Ch, as well as their mixtures, are presented in Figure 4a. It is shown that the spectra of individual biopolymers have broad absorption bands with maxima in the mid-ultraviolet region at wavelengths (λmax) of (224 ± 1) and (237 ± 1) nm for chitosan and gelatin, respectively. The position of the absorption bands of biopolymers is due to the presence in their molecules of chromophores that absorb in the UV region of the spectrum [44]. For chitosan, these are hydroxyl and amino groups. For gelatin, these are carboxyl groups of residues of aspartic (Asp) and glutamic (Glu) acids, lone electron pairs of nitrogen conjugated with double bonds in the residues of histidine (His) and arginine (Arg), and hydroxyl groups, as well as conjugated double bonds in the benzene nuclei of aromatic amino acids, in particular, tyrosine (Tyr).

Figure 4.

(a) UV absorption spectra for hydrosols of Ch (CCh = 0.5 wt%), FG (CFG = 1.0 wt%), and aqueous mixtures of Ch–FG at different chitosan/gelatin ratios (Z, gCh/gFG): 0.01 (1), 0.05 (2), 0.10 (3), 0.20 (4), 0.30 (5), 0.40 (6), 0.50 (7), 0.60 (8), and 0.70 (9); (b) FTIR spectra for chitosan, FG, and complexes of FG with Ch at different chitosan-to-gelatin mass ratios, Z (gCh/gFG).

For Ch–FG mixtures in the range of Z from 0.01 to 0.70 gCh/gFG, a bathochromic shift in the absorption band maximum relative to individual biopolymers up to λmax of (239 ± 1) nm is observed. In addition, an increase in the A and a broadening of the absorption band of aqueous mixtures compared to the hydrosol of native FG with increasing Z were shown.

The bathochromic shift in the spectra of mixtures of biopolymers is explained by electrostatic interactions of the amino groups of chitosan with the carboxyl groups of Asp and Glu residues of gelatin, as well as by hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl and/or amino groups of the polysaccharide and amino acid residues of gelatin. The increase in A and the broadening of the absorption band of aqueous mixtures is associated with the coarsening of the particles of the dispersed phase of the aqueous mixture of Ch–FG compared to the hydrosols of individual biopolymers, which causes an increase in the non-Rayleigh character of light scattering. More importantly, the observed enlargement of particles in sols—hydrogel precursors—is an additional reason for strengthening the structural network of the complex hydrogel, increasing its rigidity and elasticity (see Section 3.1). A similar strengthening of the hydrogel with an increase in the size of the supramolecular complexes of bovine skin gelatin–chitosan was shown by the authors earlier [16,29]. In addition, for example, pectin could change the structure of FG with the formation of large aggregates, which is shown by fluorescence and ultraviolet absorption methods [45], while pectin-modified FG could endow FG and had similar gel strength and thermal and textural properties to pig skin gelatin.

Figure 4b represents the FTIR absorption spectra of FG, Ch, and the FG–Ch complex in the wave number range of 1200–1800 cm−1; it has been previously determined that it is in this range the shifts in the absorption bands in the FG spectrum occur under the influence of Ch. FTIR spectroscopy is a well-established technique for studying gelatin’s secondary structure and functional group interactions. Characteristic peaks for gelatin and Ch are represented in Table S3 [16,30,46,47,48]. The FTIR spectrum of FG demonstrates characteristic absorption peaks of peptide bonds at 1653 cm−1 (amide I band), 1539 cm−1 (amide II band), and 1240 cm−1 (amide III band), corresponding to C=O stretching vibrations, C–N and N–H bending vibrations, and C–N stretching vibrations and N–H deformation, respectively [46]. In addition, the spectrum of FG contains an absorption band at 1404 cm−1 assigned to symmetric stretches of COOH groups [47].

The FTIR absorption spectrum of chitosan demonstrates characteristic peaks at 1653 cm−1 (amide I band), corresponding to the stretching vibrations of C=O and N–H, at 1561 cm−1 (amide II band) for the stretching vibrations of N–H, C–N, and C–C and at 1261 cm−1 (amide III band) for N–H and C–N stretching vibrations [48].

Figure 4b shows that the amide I band has the same position at 1653 cm−1 for both individual biopolymers and their mixtures. The amide II band of FG under the influence of chitosan undergoes a shift to the high-frequency region from 1539 cm−1 in the spectrum of FG to 1543 cm−1 in the spectra of FG–Ch mixtures at Z from 0.09 to 0.15 gCh/gFG. The amide III band of FG also shifts towards higher wavenumbers—from 1240 cm−1 in the spectrum of FG to 1242 cm−1 in the spectra of mixtures throughout the Z region studied (from 0.03 to 0.15 gCh/gFG). The 1404 cm−1 band of FG does not undergo any noticeable changes under the influence of chitosan.

The absence of a significant shift for the 1404 cm−1 band in the spectrum of FG shows that the –COOH groups of its macromolecules slightly participate in the intermolecular interactions between gelatin with chitosan, which indicates weak electrostatic interactions. This is explained by the weak ionization of the carboxyl groups of FG at the acidic pH values (3.2–3.9), lying significantly below pIFG (7.6), at which point FG–Ch complexes were formed; however, electrostatic interactions should not be completely excluded [30]. Obviously, the supramolecular complexes of FG with chitosan are formed mainly due to hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds; in particular, it is indicated by the shift in the amide II band in the spectrum of FG (Figure 4b). Similar “blue” shifts caused by the formation of hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl and/or amino groups of gelatin and chitosan upon their complexation were demonstrated by [5,47]. Usually, the analysis of the IR spectra of mixtures of FG with a polysaccharide, for example, with pectin [49], shows that the formation of complexes between biopolymers occurs through electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions. More importantly, at a pH close to the pI of gelatin, it is the electrostatic interactions between the oppositely charged groups of gelatin and chitosan that promote the formation of supramolecular complexes [29,30].

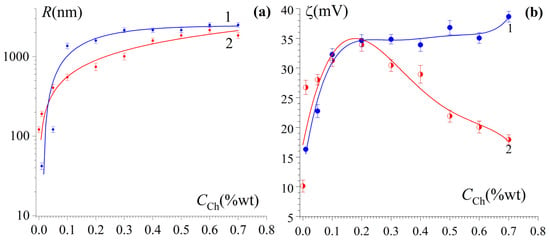

Zeta potential, ζ, and radius, R, of particles of chitosan and the gelatin–chitosan complex at different mass Ch/FG ratios, Z, are demonstrated in Figure 5, Table S4.

Figure 5.

Dependence of hydrodynamic radius R (a) and ζ-potential (b) for Ch (1) and FG–Ch (2) particles in aqueous phase on the chitosan concentration CCh. CFG = 1.0 wt%, 23 °C.

The particle size of the dispersed phase in Ch hydrosols without gelatin at CCh = 0.3 wt% reached a value of R ≈ 2200 nm, which did not change significantly thereafter. Accordingly, the ζ-potential reached 35 mV and then changed insignificantly (see Figure 5a, curves 1). In FG–Ch hydrosols, R increased from 120 nm (without chitosan) to ~(1800–2000) nm at CCh = (0.5–0.7) wt%, which was slightly smaller than the particle size in chitosan sols at the same CCh values (Figure 5a, curve 2). This increase in size of FG–Ch particles with CCh growth is in good agreement with the increasing in the non-Rayleigh character of light scattering detected by UV spectroscopy (see Figure 4a). As for the ζ-potential, for FG–Ch particles, it first increased to 34 mV at CCh = 0.2 wt% (Z = 0.2 gCh/gFG) and then dropped to 18 mV at CCh = 0.7 wt% (Figure 5b, curve 2).

It should be noted that there is a clear connection between changes in the hydrodynamic radius and a decrease in electrostatic stabilization (ζ, mV) in FG–Ch sol. With increasing concentration, highly charged Ch causes additional ionization of the FG carboxyl groups at an acidic pH [50], leading to partial charge compensation due to electrostatic interactions between the carboxyl groups of FG and the amino groups of Ch. Furthermore, the significant increase in FG–Ch particle size (R, nm) with increasing chitosan content may reflect aggregation caused by the hydrophobic domains of weakly charged particles.

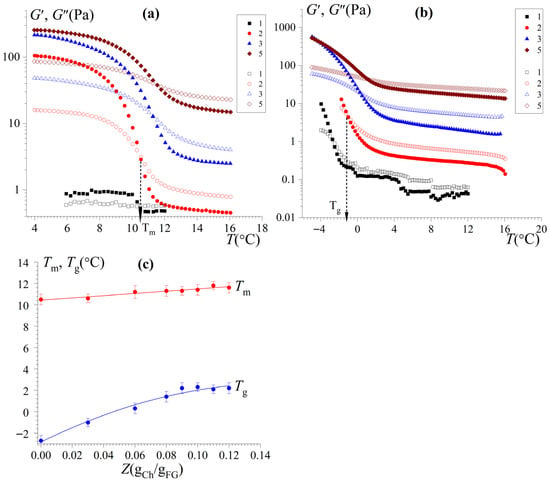

3.5. Gel Thermal Stability: Gelling and Melting Temperatures

Thermal stability is an extremely important property of hydrogels, which largely determines the possibility of their use in food products. The temperature-dependent viscoelastic properties (storage and loss moduli) of FG hydrogels modified with chitosan for heating and cooling are shown in Figure 6. In the case of heating, the crossover points at G′(T) = G″(T) are considered as the gel melting temperature, Tm, while in the case of cooling, it is considered as the gelation temperature, Tg [10].

Figure 6.

Dependencies of the storage modulus G′ (open points) and the loss modulus G″ (full points) on the temperature T at f = 1 Hz and γ = 1% for FG and FG–Ch complex hydrogels at different chitosan-to-gelatin mass ratios Z (gCh/gFG): 0 (1), 0.03 (2), 0.06 (3), 0.09 (4), and 0.12 (5) for heating (a) and cooling (b). The temperature change rate is 1 °C/min. (c) Dependencies of the melt point Tm and the gelation point Tg on the chitosan-to-gelatin w/w ratios Z. CFG = 10 wt%.

With increasing temperature (Figure 6a), there is a sharp decrease in both G′ and G″. A sharp decrease in G′ indicates the destruction of temperature-sensitive physical bonds and a conformational transition from the helix to coil of FG macromolecules, accompanied by the destruction of aggregates and an increase in the solubility of gelatin, which ends with the gel–sol transition. In this sense, the Tm can be considered a characteristic of the thermal stability of the hydrogel [5]. It should be noted that modification of FG hydrogels with chitosan (in the region of low chitosan-to-gelatin ratios) leads to an increase in thermal stability; the Tm increases by 1.2 °C—from 10.5 °C for FG gels to 11.7 °C for FG–Ch gels (Figure 6c)—which indicates the strengthening of the hydrogel network formed by FG–Ch complexes.

In the cooling regime, at the high temperatures during the beginning, G″ was greater than G′ (Figure 6b), while with a further decrease in temperature, a rapid increase in both G′ and G” was observed. The rapid increase in G′ indicates a gelation of FG hydrogels induced by the formation of triple collagen-like helices, a decrease in gelatin solubility, the formation of aggregates, and then a 3D gel network. When chitosan is introduced into an FG hydrogel, a shift in the gelation temperature is observed: the Tg increases by 5 °C—from −2.7 °C for FG gels to 2.3 °C for FG–Ch gels (Figure 6c, Table S5). Since chitosan does not form gels at the low concentrations used, FG–Ch complex gelation is due to the association of the triple collagen-like helices of gelatin. At the same time, chitosan being part of a complex with FG stimulates its gelation, promoting the formation of aggregates and junction zones.

A similar result was obtained for the hydrogels of FG, for example, with gellan [13], and mammalian gelatin (type B) with sodium alginate [51] and chitosan [31]. Theoretically [16,48], the introduction of a functional group of polysaccharides could change the triple helix contents in gelatin via inducing gelatin physical cross-linking. In addition, the highest strength and thermal stability of the hydrogel may be due to the fact that the amination of gelatin (with chitosan) can generate more hydrogen bonds, which positively influence the strength gel, strengthening the structure of the gel network and increasing the melting temperature. Similar phenomena are observed under phosphorylation of FG (with sodium pyrophosphate), increasing the functional properties of FG [52].

It is necessary to note the excesses of the Tm over the Tg of the studied hydrogels. This is explained by the fact that the destruction of triple collagen-like helices upon heating, which are the nodes of the 3D hydrogel network, and their formation upon cooling is kinetic in nature [8]. The hydrogels under heating (Figure 6a) were formed at 4 °C for 20 h (see Section 2). Gels formed under such conditions are more thermostable than gels obtained under rapid continuous cooling at a rate of 1 °C/min (Figure 6b).

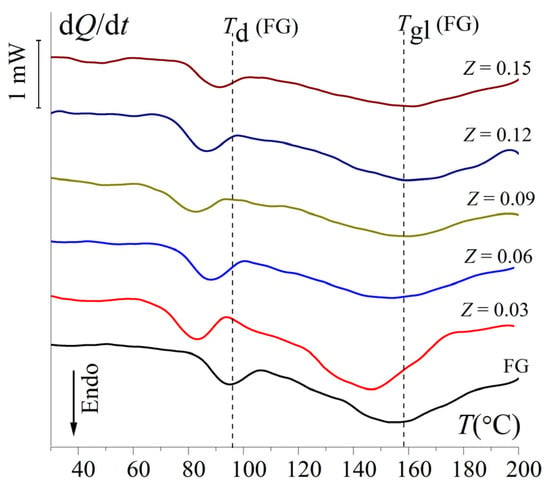

Thermal properties of the gels (lyophilized gels) were studied by differential scanning calorimetry, which has become a popular tool for studying thermal transitions in gelatin-containing systems [53]. Figure 7 shows the heat flow curves for FG gels and FG–Ch complex gels at different chitosan-to-gelatin w/w ratios, Z.

Figure 7.

Heat flow curves dQ/dt(T) for FG and FG–Ch complex hydrogels at different chitosan-to-gelatin w/w ratios, Z (gCh/gFG). Heating rate was 5 °C/min.

Experimental data showed two endothermic peaks: a sharper one, associated with the denaturation of biopolymer segments at Td, and a broader one, associated with the glass transition at Tgl (Table S5). According to [22], the broadening of the glass transition peak is due to the formation of nonequilibrium structures of FG and Ch during this process. For FG gel, the denaturation temperature, Td, is (96.5 ± 0.9) °C (for mammalian gelatin, Td = 100.3 °C, according to [22], and Td = 98.3 °C, according to [53]) and Tgl = (159.5 ± 1.0) °C. For FG–Ch complex gels, Td first decreased to (82.6 ± 0.8) °C at Z = 0.03 gCh/gFG and then tended to increase, reaching (90.8 ± 0.9) °C at Z = 0.15 gCh/gFG. Similarly, the glass transition temperature, Tgl, dropped to (148.6 ± 1.1) °C at Z = 0.03, then increased to (160.5 ± 1.2) °C at Z = 0.15 (Figure 7). Such non-monotonic change in thermal characteristics of FG–Ch complex gels with increasing Z is due to the fact that the denaturation and glass transition temperatures of chitosan are somewhat lower than the Td and Tgl of gelatin [22]. At low Z values, the main effect is the overlap of individual peaks of FG and Ch. However, with increasing Z to 0.15 gCh/gFG, the effect of FG–Ch complexation becomes decisive, increasing the thermal stability of the gels; accordingly, Td and Tgl increase. Apparently, the Tgl of hydrogels increases with an increase in the Ch/FG mass ratio due to a decrease in the mobility of individual biopolymer macromolecules during complex formation.

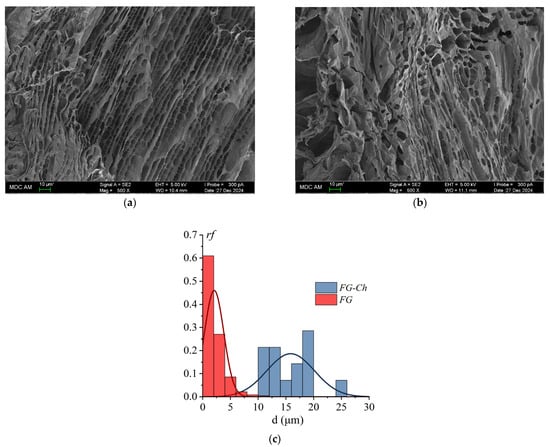

3.6. Microstructure of Modified Gel

SEM micrographs make it possible to observe the morphological changes occurring in gelatin hydrogels when modifying the supramolecular structure by introducing a polysaccharide. Typical SEM microphotographs of morphological patterns of the FG gel and the complex FG–Ch at a low chitosan-to-gelatin mass ratio of 4 × 10−1 gCh/gFG (i.e., with the addition of only 0.8 wt% of chitosan) are presented in Figure 8. The FG gel has a mesh-like porous structure (Figure 8a). It is formed by intersecting collagen-like triple helices (fibrils), between which voids (porous cells) are observed, distributed along the fibrils and formed, apparently, by disordered parts of gelatin polypeptide chains.

Figure 8.

SEM microphotographs of FG hydrogel (a) and FG–Ch complex hydrogel at chitosan-to-gelatin mass ratio 4 × 10−1 gCh/gFG (b); pore size (diameter, d) distribution histograms for FG and FG–Ch gels (c).

Analysis of SEM images (Figure 8) shows that the introduction of chitosan and the formation of gelatin–chitosan complexes disrupt the arrangement of gelatin gel chains. The FG gel cells are elongated and rectangular, with an average diameter of 2.1 ± 1.7 µm (Figure 8a,c). The complex gel exhibits the formation of additional zones of connections between the complexes; the porous cells between the structural elements are modified—they become larger (Figure 8b,c). The cell structure of the FG–Ch gel is similar to that of the original FG; the cells are oblong with thin transverse filaments. The porous cell size increases to 15.8 ± 4.3 µm. Other ionic polysaccharides, such as pectin [11] and κ-carrageenan [54], demonstrate a similar effect on the morphology of FG gel.

The special network microstructure of complex FG–Ch hydrogels may be one of the main reasons for its high rheological properties and thermal stability.

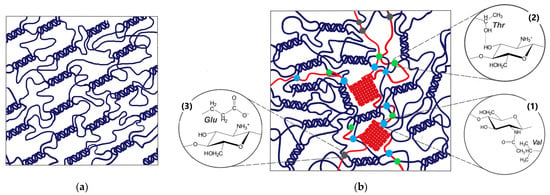

Joint analysis of the results obtained by rheological, UV spectroscopy, FTIR spectroscopy, DSC, QELS, and SEM methods supplemented by the literature data allows us to propose a hypothetical scheme of FG–Ch hydrogel morphological structure including different binding modes (Figure 9). Hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds predominate during gel structure formation (FTIR spectroscopy data); electrostatic interactions at pH values far from the pI of FG, type A, are hindered but not completely excluded. The presence of Ch disrupts the ordered structure of the initial gelatin gel. The porous cell size distribution broadens, and the average cell size increases (SEM data). The introduction of the polysaccharide creates additional binding sites, which strengthens the gel network (the yield stress, σY, and elastic plateau modulus, G′pl, increase with increasing Ch concentration, and the gel thermal stability increases, according to DSC data). The formation of hydrophobic domains with a decrease in the charge of FG–Ch complexes—hydrogel precursors (QELS data)—can additionally contribute to gel strengthening.

Figure 9.

Hypothetical schemes of hydrogel morphological structure: (a)—FG; (b)—FG–Ch, including different binding modes: (1)—hydrophobic interactions, (2)—hydrogen bonds, and (3)—electrostatic interactions.

4. Conclusions

Modification of FG (type A, pI 7.6) by adding a cationic polysaccharide, chitosan, leads to significant changes in the properties of the resulting hydrogels. The combined use of FG and Gh (at low chitosan-to-gelatin w/w ratios up to 0.15 gCh/gFG) shows a synergistic effect on the rheological properties of biopolymer gels. An increase in the polysaccharide content leads to an increase in the elastic properties and rigidity, which indicates a strengthening of the 3D network of complex gels compared to FG. The linear region of viscoelastic behaviour becomes shorter, and the stability under oscillatory deformations decreases, which is associated with structural changes in gelatin modified with chitosan. Being systems that belong to soft matter with a yielding point, FG–Ch hydrogels demonstrate a significant increase in the yield stress with increasing polysaccharide content.

The observed changes in rheological properties are due to the self-assembly of supramolecular complexes of FG with Ch in aqueous mixtures, which are hydrogel precursors. Complexation is caused by hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds in the absence of electrostatic interactions in the acidic pH region (3.2–3.9), which is confirmed by UV and FTIR spectroscopic studies. Supramolecular complexes of a certain composition can modify the rheological properties of hydrogels. The analysis of viscoelastic properties suggests that modification of the macromolecular structures of FG as part of a complex with chitosan leads to increased hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds, as well as to the strengthening of junction zones. An increase in the chitosan content is accompanied by an increase in the thermal stability of complex gels and an increase in the melting temperature and gelation temperature as well denaturation temperatures of biopolymers.

The ability to regulate the viscoelastic properties, rigidity, and plasticity of FG–Ch complex hydrogels is an excellent advantage for their use in modern food technologies as the basis for structured products of high biological value.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/polysaccharides6040110/s1, Table S1: The rigidity coefficient (k) and frequency dependence (m) of the hydrogel at different chitosan-to-fish gelatin w/w ratios (Z); Table S2: Rheological parameters of FG and FG-Ch complex gels (CFG = 10 wt%, σ0 = 10 Pa) for different chitosan-to-gelatin w/w ratios Z; Table S3: Location and assignment of the peaks identified in the FT-IR spectra of biopolymers [16,30,45,46,47,48]; Table S4: Hydrodynamic radius R (nm) and ζ-potential (mV) for Ch and FG–Ch particles in aqueous phase at the different chitosan concentration CCh. CFG = 1.0 wt%, 23 °C; Table S5: The melt point Tm and the gelation point Tg for FG–Ch gels (CFG = 10 wt%), the denaturation of biopolymer segments temperature Td and the glass transition temperature Tgl for lyophilized FG–Ch gels at different the chitosan-to-gelatin w/w ratios Z.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D. and N.V.; methodology, N.V. and S.D.; software, N.V.; validation, V.B., T.D., L.P. and A.N.; formal analysis, Y.K.; investigation, V.B., T.D., L.P., Y.K., D.K. and A.N.; resources, T.D. and L.P.; data curation, N.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D. and N.V.; writing—review and editing, S.D.; visualization, N.V. and D.K.; supervision, S.D. and Y.Z.; project administration, S.D. and N.V.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant number 23-64-10020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the staff of the Chemistry Department and Laboratory of Chemistry and Technology of Marine Bioresources (established with the financial support of the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Reg. No. 1023041300048-6) of the Murmansk Arctic University for the technical support and materials used for experiments. The authors are grateful to V. Abramov from Kazan Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics for analysis of SEM data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Ch | Chitosan |

| FG | Fish gelatin |

| Z | Chitosan–to–fish gelatin mass ratio |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| QELS | Quasi-elastic light scattering |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

References

- Oliveira, V.M.; Assis, C.R.D.; Costa, B.A.M.; Neri, R.C.A.; Monte, F.T.; Freitas, H.M.S.C.V.; Franka, R.C.P.; Santos, J.F.; Bezerra, R.S.; Porto, A.L.F. Physical, biochemical and spectroscopic techniques for characterization collagen from alternative sources: A review based on the sustainable valorization of aquatic by-products. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1224, 129023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Huang, M.; Cao, G.; Tao, F.; Shen, Q.; Zhou, G.; Yang, H. Repurposing fish waste into gelatin as a potential alternative for mammalian sources: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 942–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joy, J.M.; Padmaprakashan, A.; Pradeep, A.; Paul, P.T.; Mannuthy, R.J.; Mathew, S. A review on fish skin-derived gelatin: Elucidating the gelatin peptides—Preparation, bioactivity, mechanistic insights, and strategies for stability improvement. Foods 2024, 13, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, L.; Huang, Q.; Ding, W.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, L. Fish gelatin: The novel potential application. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 63, 103581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshki-Modaress, M.; Zandi, M.; Rajabi, S. Tailoring the gelatin/chitosan electrospun scaffold for application in skin tissue engineering: An in vitro study. Prog. Biomater. 2018, 7, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.A.; Bhat, R. Fish gelatin: Properties, challenges, and prospects as an alternative to mammalian gelatins. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurilmala, M.; Suryamarevita, H.; Hizbullah, H.H.; Agoes, M.J.; Yoshihiro, O. Fish skin as a biomaterial for halal collagen and gelatin. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, I.J.; Draget, K.I. Gelatin. In Handbook of Hydrocolloids; Phillips, G.O., Williams, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; pp. 142–163. [Google Scholar]

- Derkach, S.R.; Voron’ko, N.G.; Kuchina, Y.A.; Kolotova, D.S.; Grokhovsky, V.A.; Nikiforova, A.A.; Sedov, I.A.; Faizullin, D.A.; Zuev, Y.F. Rheological Proper-ties of Fish and Mammalian Gelatin Hydrogels as Bases for Potential Practical Formulations. Gels 2024, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sow, L.C.; Chong, J.M.N.; Liao, Q.X.; Yang, H. Effects of κ-carrageenan on the structure and rheological properties of fish gelatin. J. Food Eng. 2018, 239, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Tu, Z.; Sha, X.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Hu, Z. Gelling properties and interaction analysis of fish gelatin–low-methoxyl pectin system with different concentrations of Ca2+. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 132, 109826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Tu, Z.; Shangguan, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Bansal, N. Characteristics of fish gelatin-anionic polysaccharide complexes and their applications in yoghurt: Rheology and tribology. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sow, L.C.; Tan, S.J.; Yang, H. Rheological properties and structure modification in liquid and gel of tilapia skin gelatin by the addition of low acyl gellan. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 90, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassenieux, C.; Nicolai, T. Mechanical properties and microstructure of (emul)gels formed by mixtures of proteins and polysaccharides. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 70, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makshakova, O.N.; Zuev, Y.F. Interaction-Induced Structural Transformations in Polysaccharide and Protein-Polysaccharide Gels as Functional Basis for Novel Soft-Matter: A Case of Carrageenans. Gels 2022, 8, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkach, S.R.; Voron’ko, N.G.; Kuchina, Y.A. Intermolecular Interactions in the Formulation of Polysaccharide-Gelatin Complexes: A Spectroscopic Study. Polymers 2022, 14, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.C.; Barbosa, J.R.; Ribeiro, S.C.A.; de Vasconcelos, M.A.M.; de Aguiar, B.A.; Pereira, S.G.V.S.; Albuquerque, G.A.; da Silva, F.N.L.; Crizel, R.L.; Campelo, P.H.; et al. Improvement of the characteristics of fish gelatin—Gum arabic through the formation of the polyelectrolyte complex. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 223, 115068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-D.; Huang, J.-J.; Wu, J.-L.; Cai, X.-X.; Tian, Y.-Q.; Rao, P.-F.; Huang, J.-L.; Wang, S.-Y. Fabrication, interaction mechanism, functional properties, and applications of fish gelatin-polysaccharide composites: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 122, 107106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, S.; Ren, J.; Udenigwe, C.C. Maillard-Type Protein–Polysaccharide Conjugates and Electrostatic Protein–Polysaccharide Complexes as Delivery Vehicles for Food Bioactive Ingredients: Formation, Types, and Applications. Gels 2022, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bather, S.; Seibt, J.H.; Hundschell, C.S.; Bonilla, J.C.; Clausen, M.P.; Wagemans, A.M. Phase behaviour and structure formation of alginate-gelatin composite gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 149, 109538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yu, J.; Qian, S.; Chen, Y. Study on texture detection of gelatin–agar composite gel based on bionic chewing. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 5093–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, A.H.; Islam, J.M.M.; Ahmed, M.; Rahman, M.F.; Ahmed, M. Preparation and characterization of artificial skin using chitosan and gelatin composites for potential biomedical application. Polym. Bull. 2012, 69, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.F.; Gomez-Guillen, M.C. A state-of-the-art review on the elaboration of fish gelatin as bioactive packaging: Special emphasis on nanotechnology-based approaches. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 79, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.L.; Yeong, W.Y.; Naing, M.W. Polyelectrolyte gelatin-chitosan hydrogel optimized for 3D bioprinting in skin tissue engineering. Int. J. Bioprinting 2025, 2, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Duan, Q.; Yu, L.; Xie, F. Thermomechanically processed chitosan: Gelatin films being transparent, mechanically robust and less hygroscopic. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 272, 118522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xue, C.; Mao, X. Chitosan: Structural modification, biological activity and application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4532–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, V.Y.; Derkach, S.R.; Konovalova, I.N.; Dolgopyatova, N.V.; Kuchina, Y.A. Mechanism of Heterogeneous Alkaline Deacetylation of Chitin: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.P.; Marques, N.S.S.; Maia, P.C.S.V.; de Lima, M.A.B.; de Oliveira Franco, L.; de Campos-Takaki, G.M. Seafood Waste as Attractive Source of Chitin and Chitosan Production and Their Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voron’ko, N.G.; Derkach, S.R.; Kuchina, Y.A.; Sokolan, N.I. The chitosan–gelatin (bio)polyelectrolyte complexes formation in an acidic medium. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 138, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staroszczyk, H.; Sztuka, K.; Wolska, J.; Wojtasz-Pajak, A.; Kolodziejska, I. Interactions of fish gelatin and chitosan in uncrosslinked and crosslinked with EDC films: FT-IR study. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2014, 117, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derkach, S.; Voron’ko, N.; Sokolan, N. The rheology of hydrogels based on chitosan–gelatin (bio)polyelectrolyte complexes. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2017, 38, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ding, F.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y. Edible films from chitosan-gelatin: Physical properties and food packaging application. Food Biosci. 2021, 40, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrova, L.; Uspenskaya, M.; Elangwe, C.; Ishevskiy, A. Architectonics of gelatin/biopolymer/transglutaminase for packaging films: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 145923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Kaith, B.S. A review on chitosan-gelatin nanocomposites: Synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2022, 179, 105362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkin, A.Y.; Isayev, A.I. Rheology: Concepts, Methods, and Applications, 3rd ed.; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zuev, Y.F.; Derkach, S.R.; Lunev, I.V.; Nikiforova, A.A.; Klimovitskaya, M.A.; Bogdanova, L.R.; Skvortsova, P.V.; Kurbanov, R.K.; Kazantseva, M.A.; Zueva, O.S. Water as a Structural Marker in Gelatin Hydrogels with Different Cross-Linking Nature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkin, A.Y.; Derkach, S.R.; Kulichikhin, V.G. Rheology of Gels and Yielding Liquids. Gels 2023, 9, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Sun, W.; Zhan, S.; Jia, R.; Lou, Q.; Huang, T. Glycosylation with different saccharides on the gelling, rheological and structural properties of fish gelatin. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 150, 109699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, K.; Wilhelm, M.; Klein, C.O.; Cho, K.S.; Nam, J.G.; Ahn, K.H.; Lee, S.J.; Ewoldt, R.H.; McKinley, G.H. A review of nonlinear oscillatory shear tests: Analysis and application of large amplitude oscillatory shear (LAOS). Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 1697–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, U.; Lin, Y.; Zuo, X.; Zheng, H. Soft matter approach for creating novel protein hydrogels using fractal whey protein assemblies as building blocks. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 151, 109828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geonzon, L.C.; Enoki, T.; Humayun, S.; Tuvikene, R.; Matsukawa, S.; Mayumi, K. Understanding the rheological properties from linear to nonlinear regimes and spatiotemporal structure of mixed kappa and reduced molecular weight lambda carrageenan gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 150, 109752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkach, S.; Zhabyko, I.; Voron’ko, N.; Maklakova, A.; Dyakina, T. Stability and the rheological properties of concentrated emulsions containing gelatin/κ-carrageenan polyelectrolyte complexes. Colloids Surf. A 2015, 483, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Cheng, P.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, G.; Han, J. Rheological insight of polysaccharide/protein based hydrogels in recent food and biomedical fields: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 1642–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabek, J.F. Experimental Methods in Polymer Chemistry: Physical Principles and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Zhao, H.; Fang, Y.; Lu, J.; Yang, W.; Qiao, Z.; Lou, Q.; Xu, D.; Zhang, J. Comparison of gelling properties and flow behaviors of microbial transglutaminase (MTGase) and pectin modified fish gelatin. J. Texture Stud. 2019, 50, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyonga, J.N.; Cole, C.G.B.; Dyodu, K.G. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy study of acid soluble collagen and gelatin from skin and bones of young and adult Nile perch (Lates niloticus). Food Chem. 2004, 86, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Xie, F. Chitosan–Gelatin Films: Plasticizers/Nanofillers Affect Chain Interactions and Material Properties in Different Ways. Polymers 2022, 14, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, N.; Shashirekha, V.; Noorjahan, S.E.; Rameshkumar, M.; Rose, C.; Sastry, T.P. Fibrin–Chitosan–Gelatin Composite Film: Preparation and Characterization. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A Pure Appl. Chem. 2005, 42, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lin, S.; Liang, S.; Wang, S.; Yoshimasa, N.; Yue, T. Unlocking stability and efficiency in benzyl isothiocyanate-loaded emulsions: Unveiling synergistic interactions of fish skin gelatin and pectin. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumrudov, V.A. Self-assembly and molecular ‘recognition’ phenomena in solutions of (bio)polyelectrolyte complexes. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2008, 77, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkach, S.R.; Kolotova, D.S.; Voron’ko, N.G.; Obluchinskaya, E.D.; Malkin, Y.A. Rheological Properties of Fish Gelatin Modified with Sodium Alginate. Polymers 2021, 13, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Lou, Q.; Wang, C.; Huang, T. Phosphorylation modification on functional and structural properties of fish gelatin: The effects of phosphate contents. Food Chem. 2022, 380, 132209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjeea, I.; Rosolen, M. Thermal transitions of gelatin evaluated using DSC sample pans of various seal integrities. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 114, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, D.; Ma, W.; Wu, C.; Liu, J.; Du, M. Strong fish gelatin hydrogels double crosslinked by transglutaminase and carrageenan. Food Chem. 2022, 376, 131873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).