Chitosan and Alginate in Aquatic Vaccine Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Chitosan and Sodium Alginate as Adjuvants and Carriers for Fish Vaccines

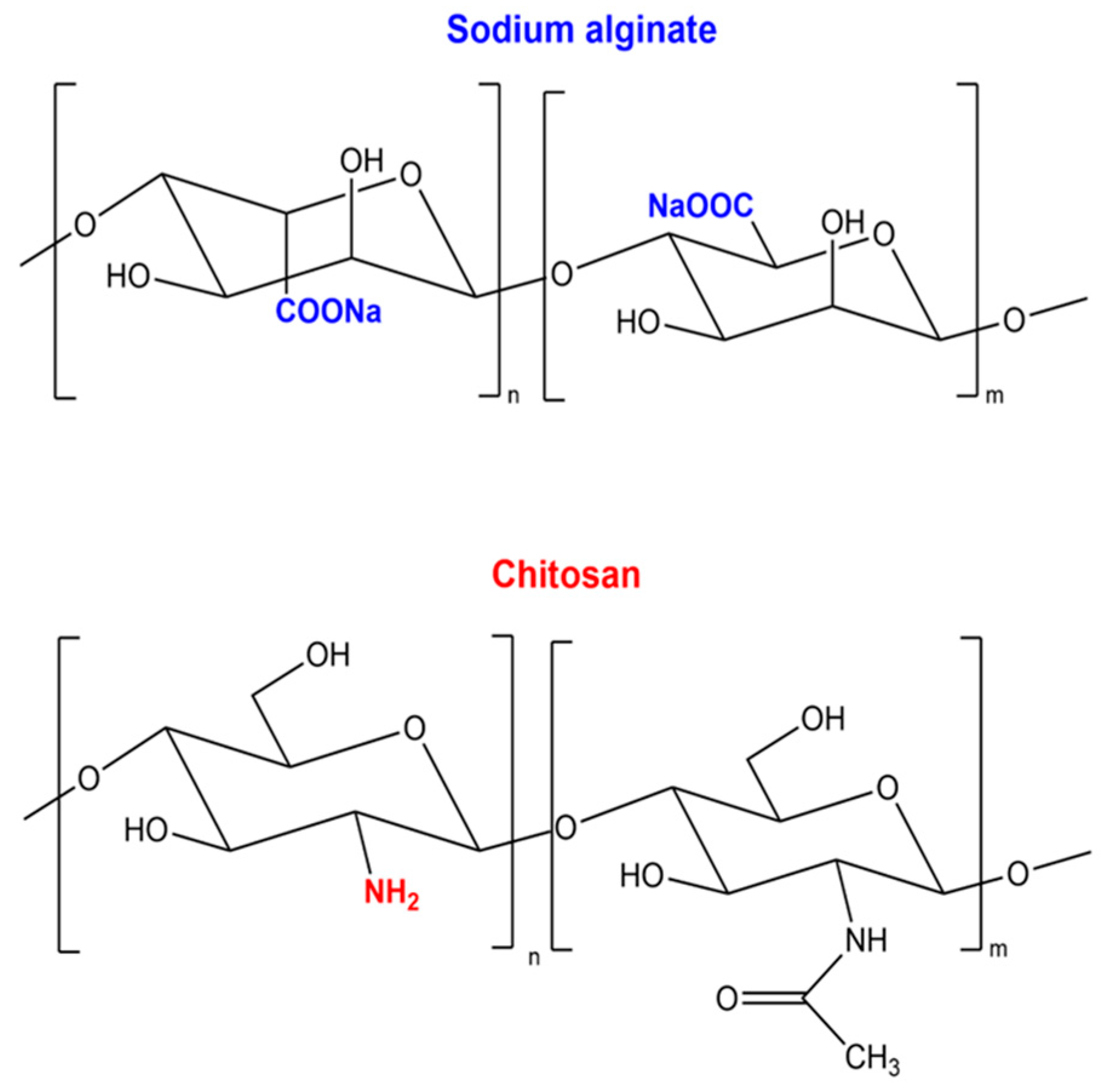

2.1. Structural Properties and Sources of Chitosan and Alginate

2.2. A Difficult Choice: Problems of Chitosan and Alginate Characterization and Standardization for Aquatic Vaccine Development

| Chitosan Based Vaccines | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish Species | Antigen | Administration Route | Source | Manufacturer | MW/Viscosity | DD | Endotoxins /Residual Proteins | Form | Reference |

| Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Streptococcus agalactiae | i/p, imm + i/p, i/m + per os or per os | n/d | Qingdao Hehai Biotechnology Company (China) | MW ≤ 1500 Da | n/d | n/d | A formalin-inactivated vaccine mixed with chito-oligosaccharides. | [51] |

| Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) | Vibrio harveyi | imm | n/d | Sigma-Aldrich (USA) | MW 50,000–190,000 Da/ 20–300 cps 1 wt.% in 1% acetic acid (25 °C, Brookfield) | >75% | n/d | An inactivated vaccine mixed with chitosan solution in acetic acid | [40] |

| Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Edwardsiella tarda | imm | n/d | n/d | Water soluble, MW < 100,000 Da | n/d | n/d | A formalin-inactivated vaccine mixed with 0.5% chitosan solution | [52] |

| Hybrid red tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) | Flavobacterium oreochromis | per os | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | An inactivated bacterium, incapsulated in a chitosan/alginate /bentonite microparticles | [53] |

| Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Edwardsiella tarda | per os | n/d | Sigma Aldrich (USA) | Low MW | n/d | n/d | Bacterin incorporated in chitosan/alginate scaffolds | [54] |

| Pacific white shrimp | Spot syndrome virus (pva-pre-miRNA 11881) | imm | Shrimp | Marine Bio Resources (Thailand) | MW 160,000 Da | 90% | n/d | TPP-chitosan nanoparticles | [42] |

| Striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus) | Edwardsiella ictaluri | imm | n/d | Merck (Thailand) | Low MW | n/d | n/d | Cationic lipid-based nanoparticles coated with chitosan | [55] |

| Red tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) | Aeromonas veronii | imm | n/d | Sigma Aldrich (USA) | MW 50,000–200,000 Da | n/d | n/d | TPP-chitosan nanoparticles | [41] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Haemorrhagic septicaemia virus (miRNA-155) | i/p | n/d | Sigma Aldrich (USA) | MW 50,000–200,000 Da | n/d | n/d | TPP-chitosan nanoparticles | [56] |

| Pacific white shrimp | Spot syndrome virus | per os | Shrimp or squid | Marine Bioresources (Thailand). | MW 35,000 Da. | higher than 90% | n/d | TPP-chitosan nanoparticles | [57] |

| Alginate Characteristics | |||||||||

| Fish Species | Antigen | Administration Route | Source | Manufacturer | MW | M/G Ratio | Endotoxins | Form | Reference |

| Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) | Vibrio harveyi | per os | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | Calcium alginate Microparticles with sodium bentonite | [58] |

| Hybrid red tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) | Flavobacterium oreochromis | per os | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | An inactivated bacterium, incapsulated in chitosan/ alginate microparticles | [53] |

| Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Edwardsiella tarda | per os | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | Bacterin incorporated in chitosan/alginate scaffolds | [54] |

3. Vaccines Based on Chitosan and/or Alginate Delivery Systems

3.1. Inactivated Vaccines with Biopolymer Adjuvant

3.2. Subunit Vaccines

3.3. DNA/RNA Vaccines Based on Chitosan and Alginate

| Cell Line | Plasmid | Gene | Agent | Transfection Efficacy, % | RPS, % | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABG HK7 | pEGFP-N1 | GFP | Lipofectamine 2000; X-tremeGENE HP; GeneJuice | 5 | n/d | [94] |

| CSTF | pEGFP | GFP | - | 2 | n/d | [95] |

| EPC RTG2 | pMCV1.4-G pMCV1.4-bga pMCV1.4-EGFP | β-gal GFP | PEI,15 kDa | EPC–30 RTG2–6 | n/d | [90] |

| Chinese sturgeon (Acipenser sinensis) head kidney cell lines | Plasmids containing the CMV promoter and GFP or RFP reporter gene | GFP RFP | X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent | 40 | n/d | [96] |

| EPC | pMCV1.4AE6- β-gal | β-gal | Fugene Trans IT LT1 | 30 | n/d | [97] |

| EPC | G3pcDNAI/Amp | GFP | Lipofectin | Low | n/d | [98] |

| OCF | pMaxGFP | GFP | Lipofectamine 3000 | 7 | n/d | [99] |

| FHM | pcDNA3.1-VP4C pcDNA3.1-VP56C | GFP | Chitosan-alginate microcapsules | 2 | 34–54 (per os) | [91] |

| ZFL | pcDNA3-GFP | GFP | Nanoparticles from chitosan and Gamma-polyglutamic acid | 100 | n/d | [93] |

| SISK | pcDNA 3.1- OMP | GFP | Chitosan nanoparticles | 100 | 46 (per os) | [92] |

| TK | pEGFP-N2-TRBIV-MCP | GFP | Chitosan nanoparticles | 40 | 68 (per os) | [100] |

| SHK-1 | EGFP-N1 | GFP | Chitosan nanoparticles | Low | 39–77 (per os) | [68] |

| Disease/Pathogen | Fish Model | Plasmid/Type | Polymers | Route | Dose/Fish | Survival Rate vs. Control | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nocardiosis (Nocardia seriolae) | Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) | pcDNA-ABP | Mannosylated chitosan | i/p | 20 µg | 80/17 | [101] |

| Viral nervous necrosis (Nodavirus) | Asian sea bass (L. calcarifer) | pcDNA3.1 modified with gene encoding for ORF of the major capsid protein | Low MW chitosan, Sigma-Aldrich | per os | - | 85/50 | [102] |

| Vibriosis (V. anguillarum) | Asian sea bass (L. calcarifer) | pcDNA3.1 modified with gene encoding OMP protein | Low MW chitosan, Sigma-Aldrich | per os | - | - | [103] |

| Vibriosis (V. anguillarum) | Asian sea bass (L. calcarifer) | pcDNA3.1 modified with gene encoding OMP38 protein | Chitosan DD 85%, Sigma-Aldrich | per os | 50 µg | 89/47 | [92] |

| Spring viremia of carp (Carp sprivivirus) | Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) | Lactobacillus plantarum coexpressing glycoprotein of SVCV and ORF81 protein of koi herpesvirus | Chitosan/alginate | per os | 50 µg | 100/18 | [104] |

| Edwardsiella septicemia (Edwardsiella tarda) | Rohu (Labeo rohita) | Bicistronic DNA vaccine (pGPD + IFN) containing GAPDH gene of E. tarda and IFN-г gene of L. rohita | Chitosan, Sigma-Aldrich | imm | 10 µg | - | [105] |

| - | Gilt-head bream (Sparus aurata) | pCMVβ modified with reporter gene encoding β -Galactosidase | Chitosan | per os or i/m | 40 µg | - | [106] |

| - | Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | pCMV-SPORT- β gal | Chitosan | i/b per os i/m | 50 µg | - | [107] |

| - | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | pcDNA3-GFP | Low MW chitosan MW 60 kDa, DD 85% | microinjection | - | [93] | |

| Lymphocystis disease/ lymphocystis disease viruses (LCDV) | Olive flounder (P. olivaceus) | pEGFP-N2-modified with gene encoding virus protein LCDV | Chitosan, MW 1080 kDa, DD 80% | per os, gavage | 30 mg | - | [108] |

| Edwardsiella septicemia (E. tarda) | Rohu (L. rohita) | pGPD + IFN containing GAPDH gene of E. tarda and IFN-г gene of L. rohita | Chitosan | per os i/m imm | 55/20% | [109] | |

| Vibriosis (Vibrio parahaemolyticus) | Black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegel) | pEGFP-N2 modified with gene encoding protein of V. parahaemolyticus strain (OS4) | Chitosan DD 85% Sigma-Aldrich | per os | 50 µg | 73/ 20 | [110] |

| Hemorrhagic septicemia. Fin and tail rot in fish (Aeromonas hydrophila) | Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) | pcDNA3.1-aerA | Chitosan MW 50 kDa, DD 93%, China. Hyaluronic acid, MW 5 kDa | per os gavage | 5 µg | - | [111] |

| Aeromonas hydrophila infection | Rohu (L. rohita) | pVAX1 modified with gene encoding outer membrane protein and hemolysin | Chitosan DD 75–85% | per os | - | 76/25 | [112] |

| Cryptocaryonosis (Cryptocaryon irritans) | Orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides) | pcDNA3.1 modified with gene encoding immobilization antigen and heat shock protein | Chitosan MW 800 kDa, DD 85% | per os | 20 µg | - | [113] |

| - | Gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) juveniles | pCMVβ | - | per os | 40 µg or 125 µg | - | [114] |

| Nodaviridae family Betanodavirus genus | European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) | pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO | Chitosan MW 390 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich | per os | 10 µg | 100/45 | [115] |

| Turbot reddish body iridovirus (TRBIV) | Turbot (S. maximus) | pEGFP-N2-TRBIV-MCP | Chitosan MW 220 kDa, DD 85%, Sigma-Aldrich | per os | 10 µg | 89/28 | [100] |

| Grass carp hemorrhagic disease caused by grass carp reovirus (GCRV) | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | pcDNA3.1-VP4C and pcDNA3.1-VP56C, respectively | Chitosan and alginate | per os | - | 54/12 | [91] |

| Infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) | Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | pcDNA3.1 contains VP2 gene | Chitosan and alginate | per os | 10 or 15 µg | 57/10 | [116] |

4. Advanced Vaccine Approaches

4.1. Hybrid Particles

4.2. Artificial Intelligence for Vaccine Optimization

5. Possible Mechanisms of Action of Chitosan in Vaccines

6. Regulatory Pathways and Ecological Safety Aspects

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pollard, A.J.; Bijker, E.M. A guide to vaccinology: From basic principles to new developments. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, D. The oral immunization of trout against Bacterium salmonicida. J. Immunol. 1942, 44, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Hu, X.; Miao, L.; Chen, J. Current status and development prospects of aquatic vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1040336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishnan, A.; Vaseeharan, B.; Ramasamy, P.; Jeyachandran, S. Oral vaccination for sustainable disease prevention in aquaculture-an encapsulation approach. Aquac. Int. J. Eur. Aquac. Soc. 2023, 31, 867–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, B.; Mahanty, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Choudhury, A.R.; Daware, A.; Bhattacharjee, S. Nanotechnology: A next-generation tool for sustainable aquaculture. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, C.; Tello-Olea, M.; Reyes-Becerril, M.; Monreal-Escalante, E.; Hernández-Adame, L.; Angulo, M.; Mazon-Suastegui, J.M. Developing oral nanovaccines for fish: A modern trend to fight infectious diseases. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 1172–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Soliman, F.M.; Adly, M.A.; Soliman, H.A.M.; El-Matbouli, M.; Saleh, M. Recent progress in biomedical applications of chitosan and its nanocomposites in aquaculture: A review. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 126, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Torrealba, D.; Ruyra, À.; Roher, N. Nanodelivery Systems as New Tools for Immunostimulant or Vaccine Administration: Targeting the Fish Immune System. Biology 2015, 4, 664–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaalan, M.; Saleh, M.; El-Mahdy, M.; El-Matbouli, M. Recent progress in applications of nanoparticles in fish medicine: A review. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.U.D.; Ali, M.; Mehdi, S.; Masoodi, M.H.; Zargar, M.I.; Shakeel, F. A review on chitosan and alginate-based microcapsules: Mechanism and applications in drug delivery systems. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 248, 125875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Rajan, D.K.; Ganesan, A.R.; Divya, D.; Johansen, J.; Zhang, S. Chitin, chitosan and chitooligosaccharides as potential growth promoters and immunostimulants in aquaculture: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 251, 126285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Middha, S.K.; Menon, S.V.; Paital, B.; Gokarn, S.; Nelli, M.; Rajanikanth, R.B.; Chandra, H.M.; Mugunthan, S.P.; Kantwa, S.M.; et al. Current Challenges of Vaccination in Fish Health Management. Animals 2024, 14, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgogna, M.; Bellich, B.; Cesàro, A. Marine polysaccharides in microencapsulation and application to aquaculture: “from sea to sea”. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 2572–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, K.; Ravichandran, S.; Muralisankar, T.; Uthayakumar, V.; Chandirasekar, R.; Seedevi, P.; Abirami, R.G.; Rajan, D.K. Application of marine-derived polysaccharides as immunostimulants in aquaculture: A review of current knowledge and further perspectives. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 86, 1177–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, M.; Fasulo, G.; Volpe, M.G. Employment of Marine Polysaccharides to Manufacture Functional Biocomposites for Aquaculture Feeding Applications. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 2680–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Sun, H.; Li, Y.; He, D.; Ren, C.; Zhu, C.; Lv, G. Effects of fucoidan on growth performance, immunity, antioxidant ability, digestive enzyme activity, and hepatic morphology in juvenile common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1167400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, J.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Putra, D.F.; Kitikiew, S.; Li, C.C.; Hsieh, J.F.; Liou, C.H.; Yeh, S.T. Shrimp that have received carrageenan via immersion and diet exhibit immunocompetence in phagocytosis despite a post-plateau in immune parameters. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 36, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponce, M.; Zuasti, E.; Anguís, V.; Fernández-Díaz, C. Anti-Bacterial and Immunostimulatory Properties of Ulvan-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles for Use in Aquaculture. Mar. Biotechnol. 2024, 26, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Zhao, J.; An, H.; Wang, Y.; Shao, J.; Weng, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W. Effects of laminarin on growth performance and resistance against Pseudomonas plecoglossicida of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 144, 109271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.F.; Jiang, F.Y.; Zhou, G.Q.; Xia, J.Y.; Yang, F.; Zhu, B. The recombinant subunit vaccine encapsulated by alginate-chitosan microsphere enhances the immune effect against Micropterus salmoides rhabdovirus. J. Fish Dis. 2022, 45, 1757–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomayor-Gerding, D.; Troncoso, J.M.; Pino, A.; Almendras, F.; Diaz, M.R. Assessing the Immune Response of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) after the Oral Intake of Alginate-Encapsulated Piscirickettsia salmonis Antigens. Vaccines 2020, 8, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilya, D.; Khan, M.I.R. Chitin and Chitosan as Promising Immunostimulant for Aquaculture. In Handbook of Chitin and Chitosan; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 761–771. [Google Scholar]

- Aghelinejad, A.; Golshan Ebrahimi, N. Investigation of delivery mechanism of curcumin loaded in a core of zein with a double-layer shell of chitosan and alginate. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, A.G.; Grumezescu, A.M. Applications of Chitosan-Alginate-Based Nanoparticles-An Up-to-Date Review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harugade, A.; Sherje, A.P.; Pethe, A. Chitosan: A review on properties, biological activities and recent progress in biomedical applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2023, 191, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, A.O.; Derkach, S.R.; Khair, T.; Kazantseva, M.A.; Zuev, Y.F.; Zueva, O.S. Ion-Induced Polysaccharide Gelation: Peculiarities of Alginate Egg-Box Association with Different Divalent Cations. Polymers 2023, 15, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosney, A.; Ullah, S.; Barčauskaitė, K. A Review of the Chemical Extraction of Chitosan from Shrimp Wastes and Prediction of Factors Affecting Chitosan Yield by Using an Artificial Neural Network. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado-González, M.; Esteban, M. Chitosan-nanoparticles effects on mucosal immunity: A systematic review. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 130, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellich, B.; D’Agostino, I.; Semeraro, S.; Gamini, A.; Cesàro, A. “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” of Chitosans. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, Y.M. Chitosan-based vaccine adjuvants: Incomplete characterization complicates preclinical and clinical evaluation. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Il’ina, A.; Varlamov, V. Determination of residual protein and endotoxins in chitosan. Prikl. Biokhimiia Mikrobiol. 2016, 52, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, V.N.; Kalitnik, A.A.; Markov, P.A.; Volod’ko, A.V.; Popov, S.V.; Ermak, I.M. Cytokine-inducing and anti-inflammatory activity of chitosan and its low-molecular derivative. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2016, 52, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zariri, A.; van der Ley, P. Biosynthetically engineered lipopolysaccharide as vaccine adjuvant. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davydova, V.N.; Komleva, D.D.; Volod’ko, A.V.; Sidorin, E.V.; Pimenova, E.A.; Kitan, S.A.; Shulgin, A.A.; Spirin, P.V.; Sidorin, A.E.; Prassolov, V.S.; et al. Comparative analysis of physicochemical properties and biological activities of chitosans from squid gladius and crab shell. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 365, 123812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, S.; Peters, L.M.; Mucalo, M.R. Chitosan: A review of sources and preparation methods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 169, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davydova, V.N.; Yermak, I.M. The Conformation of Chitosan Molecules in Aqueous Solutions. Biophysics 2018, 63, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, H.; Srebnik, S. Structural Characterization of Sodium Alginate and Calcium Alginate. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 2160–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojorges, H.; López-Rubio, A.; Martínez-Abad, A.; Fabra, M.J. Overview of alginate extraction processes: Impact on alginate molecular structure and techno-functional properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 140, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayianni, M.; Sentoukas, T.; Skandalis, A.; Pippa, N.; Pispas, S. Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles for Nucleic Acid Delivery: Technological Aspects, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu Lan, N.G.; Dong, H.T.; Vinh, N.T.; Salin, K.R.; Senapin, S.; Pimsannil, K.; St-Hilaire, S.; Shinn, A.P.; Rodkhum, C. A novel vaccination strategy against Vibrio harveyi infection in Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) with the aid of oxygen nanobubbles and chitosan. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 149, 109557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkarun, P.; Kitiyodom, S.; Kamble, M.T.; Bunnoy, A.; Boonanuntanasarn, S.; Yata, T.; Boonrungsiman, S.; Thompson, K.D.; Rodkhum, C.; Pirarat, N. Systemic and mucosal immune responses in red tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) following immersion vaccination with a chitosan polymer-based nanovaccine against Aeromonas veronii. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 146, 109383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangchai, P.; Somboonwiwat, K. Chitosan nanoparticles encapsulating pva-pre-miR-11881 for RNA therapy against white spot syndrome virus in the Pacific white shrimp. Aquaculture 2025, 606, 742583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, T.; Gulich, M.; Richter, K. Quality Control and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) for Chitosan-Based Biopharmaceutical Products. In Chitosan-Based Systems for Biopharmaceuticals; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 503–524. [Google Scholar]

- Szymańska, E.; Winnicka, K. Stability of Chitosan—A Challenge for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 1819–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyalina, T.; Zubareva, A.; Lopatin, S.; Zubov, V.; Sizova, S.; Svirshchevskaya, E. Correlation analysis of chitosan physicochemical parameters determined by different methods. Org. Med. Chem. Int. J. 2017, 1, 555562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalova, M.; Shagdarova, B.; Zubov, V.; Svirshchevskaya, E. Express analysis of chitosan and its derivatives by gel electrophoresis. Prog. Chem. Appl. Chitin Its Deriv. 2019, XXIV, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezrodnykh, E.A.; Vyshivannaya, O.V.; Polezhaev, A.V.; Abramchuk, S.S.; Blagodatskikh, I.V.; Tikhonov, V.E. Residual heavy metals in industrial chitosan: State of distribution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghattas, M.; Chevrier, A.; Wang, D.; Alameh, M.-G.; Lavertu, M. Reducing endotoxin contamination in chitosan: An optimized purification method for biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 10, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, S.; Goycoolea, F.M.; Moerschbacher, B.M.; Rivera-Rodriguez, G.R. Parameters influencing the size of chitosan-TPP nano- and microparticles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, B.; Piacentini, E.; Bazzarelli, F.; Calderoni, G.; Vacca, P.; Figoli, A.; Giorno, L. Scalable production of chitosan sub-micron particles by membrane ionotropic gelation process. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 318, 121125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-l.; Wangkahart, E.; Huang, J.-w.; Huang, Y.-x.; Huang, Y.; Cai, J.; Jian, J.-c.; Wang, B. Immune response and protective efficacy of Streptococcus agalactiae vaccine coated with chitosan oligosaccharide for different immunization strategy in nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 145, 109353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhakumar; Ramachandran, I.; Elumalai, P. Mucoadhesive chitosan-based nano vaccine as promising immersion vaccine against Edwardsiella tarda challenge in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2025, 286, 110976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangsunan, P.; Thangsunan, P.; Mahatnirunkul, T.; Buncharoen, W.; Saenphet, K.; Saenphet, S.; Phaksopa, J.; Thompson, K.D.; Srisapoome, P.; Kumwan, B.; et al. Development and characterization of an innovative Flavobacterium oreochromis antigen-encapsulated hydrogel bead for enhancing oral vaccine delivery in hybrid red tilapia (Oreochromis spp.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2025, 165, 110483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, P.; Nandhakumar, K.; Lakshmi, S.; Wangkahart, E. Evaluation of the efficacy of microencapsulated scaffold against Edwardsiella tarda in oral vaccinated Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2025, 165, 110513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitiyodom, S.; Kamble, M.T.; Yostawonkul, J.; Sukkarun, P.; Thompson, K.D.; Pirarat, N. Effects of immersion vaccination in striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus) using a cationic lipid-based mucoadhesive nanovaccine against Edwardsiella ictaluri. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2025, 165, 110540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, T.D.; Nikapitiya, C.; De Zoysa, M. Chitosan nanoparticles-based in vivo delivery of miR-155 modulates the Viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus-induced antiviral immune responses in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 144, 109234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonjaroen, V.; Jitrakorn, S.; Charoonnart, P.; Kaewsaengon, P.; Thinkohkaew, K.; Payongsri, P.; Surarit, R.; Saksmerprome, V.; Niamsiri, N. Optimizing chitosan nanoparticles for oral delivery of double-stranded RNA in treating white spot disease in shrimp: Key insights and practical implications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 290, 138970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchuwittayakul, A.; Thompson, K.D.; Thangsunan, P.; Phaksopa, J.; Buncharoen, W.; Saenphet, K.; Kumwan, B.; Meachasompop, P.; Saenphet, S.; Wiratama, N.; et al. Evaluation of a hydrogel platform for encapsulated multivalent Vibrio antigen delivery to enhance immune responses and disease protection against vibriosis in Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2025, 160, 110230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafalla, C.; Bøgwald, J.; Dalmo, R.A. Adjuvants and immunostimulants in fish vaccines: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 35, 1740–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Villegas, J.; García-Alcazar, A.; Meseguer, J.; Mulero, V. Aluminum adjuvant potentiates gilthead seabream immune responses but induces toxicity in splenic melanomacrophage centers. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 85, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, P.; Sun, F.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. An oral vaccine based on chitosan/aluminum adjuvant induces both local and systemic immune responses in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Vaccine 2021, 39, 7477–7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Bruce, T.J.; Jones, E.M.; Cain, K.D. A Review of Fish Vaccine Development Strategies: Conventional Methods and Modern Biotechnological Approaches. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, G.; Liu, X.; Ai, T.; Su, J. Astragalus polysaccharides, chitosan and poly(I:C) obviously enhance inactivated Edwardsiella ictaluri vaccine potency in yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 87, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkarun, P.; Kitiyodom, S.; Yostawornkul, J.; Chaiin, P.; Yata, T.; Rodkhum, C.; Boonrungsiman, S.; Pirarat, N. Chitosan-polymer based nanovaccine as promising immersion vaccine against Aeromonas veronii challenge in red tilapia (Oreochromis sp.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 129, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halimi, M.; Alishahi, M.; Abbaspour, M.R.; Ghorbanpoor, M.; Tabandeh, M.R. Valuable method for production of oral vaccine by using alginate and chitosan against Lactococcus garvieae/Streptococcus iniae in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 90, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitiyodom, S.; Trullàs, C.; Rodkhum, C.; Thompson, K.D.; Katagiri, T.; Temisak, S.; Namdee, K.; Yata, T.; Pirarat, N. Modulation of the mucosal immune response of red tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) against columnaris disease using a biomimetic-mucoadhesive nanovaccine. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 112, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, S.; Shin, S.M.; Kwak, I.S.; Cho, S.H.; Jung, S.J. Efficacy of Chitosan-PLGA encapsulated trivalent oral vaccine against viral haemorrhagic septicemia virus, Streptococcus parauberis, and Miamiensis avidus in olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 127, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Aravena, A.; Fuentes, Y.; Cartagena, J.; Brito, T.; Poggio, V.; La Torre, J.; Mendoza, H.; Gonzalez-Nilo, F.; Sandino, A.M.; Spencer, E. Development of a nanoparticle-based oral vaccine for Atlantic salmon against ISAV using an alphavirus replicon as adjuvant. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015, 45, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, H.; Thomas, J. A review on the recent advances and application of vaccines against fish pathogens in aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2022, 30, 1971–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammas, I.; Bitchava, K.; Gelasakis, A.I. Transforming Aquaculture through Vaccination: A Review on Recent Developments and Milestones. Vaccines 2024, 12, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmour, I.; Islam, N. Recent advances on chitosan as an adjuvant for vaccine delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 200, 498–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, T.; Swain, P. Alginate-chitosan-PLGA composite microspheres induce both innate and adaptive immune response through parenteral immunization in fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 35, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, T.; Swain, P. Antigen encapsulated alginate-coated chitosan microspheres stimulate both innate and adaptive immune responses in fish through oral immunization. Aquac. Int. 2014, 22, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Avadhani, K.; Mutalik, S.; Sivadasan, S.M.; Maiti, B.; Girisha, S.K.; Venugopal, M.N.; Mutoloki, S.; Evensen, Ø.; Karunasagar, I.; et al. Edwardsiella tarda OmpA Encapsulated in Chitosan Nanoparticles Shows Superior Protection over Inactivated Whole Cell Vaccine in Orally Vaccinated Fringed-Lipped Peninsula Carp (Labeo fimbriatus). Vaccines 2016, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Wang, X.; Wang, K.; He, J.; Zhu, L.; He, Y.; Chen, D.; Ouyang, P.; Geng, Y.; Huang, X.; et al. Preparation, characterization and evaluation of the immune effect of alginate/chitosan composite microspheres encapsulating recombinant protein of Streptococcus iniae designed for fish oral vaccination. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 73, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliari, S.; Dema, B.; Sanchez-Martinez, A.; Montalvo Zurbia-Flores, G.; Rollier, C.S. DNA Vaccines: History, Molecular Mechanisms and Future Perspectives. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 168297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yao, F. Chitosan and its derivatives A promising non-viral vector for gene transfection. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2002, 83, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, M.P.; Xia, W.; Hartsell, S.; McCaman, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, S.; Harvey, S.; Bringmann, P.; Cobb, R.R. Transient transfection of CHO-K1-S using serum-free medium in suspension: A rapid mammalian protein expression system. Protein Expr. Purif. 2005, 40, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoemann, C.D.; Guzmán-Morales, J.; Tran-Khanh, N.; Lavallée, G.; Jolicoeur, M.; Lavertu, M. Chitosan Rate of Uptake in HEK293 Cells is Influenced by Soluble versus Microparticle State and Enhanced by Serum-Induced Cell Metabolism and Lactate-Based Media Acidification. Molecules 2013, 18, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankov, V.; Shagdarova, B.; Varlamov, V.; Esipov, R.; Svirshchevskaya, E. Large size DNA in vitro and in vivo delivery using chitosan transfection. Prog. Chem. Appl. Chitin Its Deriv. 2017, XXII, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raik, S.V.; Mashel, T.V.; Muslimov, A.R.; Epifanovskaya, O.S.; Trofimov, M.A.; Poshina, D.N.; Lepik, K.V.; Skorik, Y.A. N-[4-(N,N,N-Trimethylammonium)Benzyl]Chitosan Chloride as a Gene Carrier: The Influence of Polyplex Composition and Cell Type. Materials 2021, 14, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badazhkova, V.D.; Raik, S.V.; Polyakov, D.S.; Poshina, D.N.; Skorik, Y.A. Effect of Double Substitution in Cationic Chitosan Derivatives on DNA Transfection Efficiency. Polymers 2020, 12, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gök, M.K. In vitro evaluation of synergistic effect of primary and tertiary amino groups in chitosan used as a non-viral gene carrier system. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 115, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şalva, E.; Turan, S.; Ekentok, C.; Akbuğa, J. Generation of stable cell line by using chitosan as gene delivery system. Cytotechnology 2016, 68, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rocha, A.; Ruiz, S.; Coll, J.M. Improvement of transfection efficiency of epithelioma papulosum cyprini carp cells by modification of cell cycle and use of an optimal promoter. Mar. Biotechnol. 2004, 6, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominko, K.; Talajić, A.; Radić, M.; Vidaček, N.Š.; Vlahoviček, K.; Bosnar, M.H.; Ćetković, H. Transfection of Sponge Cells and Intracellular Localization of Cancer-Related MYC, RRAS2, and DRG1 Proteins. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbichler, A.M.; Aschberger, T.; Pelster, B. A method to evaluate the efficiency of transfection reagents in an adherent zebrafish cell line. BioResearch Open Access 2013, 2, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.; Fernandez-Alonso, M.; Rocha, A.; Estepa, A.; Coll, J.M. Transfection of epithelioma papulosum cyprini (EPC) carp cells. Biotechnol. Lett. 2001, 23, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.L.; Chen, L.M.; Le, Y.; Li, Y.L.; Hong, Y.H.; Jia, K.T.; Yi, M.S. Establishment of a cell line with high transfection efficiency from zebrafish Danio rerio embryos and its susceptibility to fish viruses. J. Fish Biol. 2017, 91, 1018–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falco, A.; Encinas, P.; Carbajosa, S.; Cuesta, A.; Chaves-Pozo, E.; Tafalla, C.; Estepa, A.; Coll, J.M. Transfection improvements of fish cell lines by using deacylated polyethylenimine of selected molecular weights. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2009, 26, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, X.; Tang, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, J.; Hu, M.; Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Yuan, G.; Yang, C.; et al. Oral pcDNA3.1-VP4/VP56-FlaC DNA vaccine encapsulated by chitosan/sodium alginate nanoparticles confers remarkable protection against GCRV infection in grass carp. Aquaculture 2023, 577, 739996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh Kumar, S.; Ishaq Ahmed, V.P.; Parameswaran, V.; Sudhakaran, R.; Sarath Babu, V.; Sahul Hameed, A.S. Potential use of chitosan nanoparticles for oral delivery of DNA vaccine in Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer) to protect from Vibrio (Listonella anguillarum). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008, 25, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.W.; Cheng, P.C.; Chou, C.M.; Lin, C.; Kuo, Y.C.; Lee, Y.A.; Liu, C.Y.; Mi, F.L.; Cheng, C.H. A novel low-molecular-weight chitosan/gamma-polyglutamic acid polyplexes for nucleic acid delivery into zebrafish larvae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 194, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.T.; Nam, Y.K.; Gong, S.P. Gene delivery into Siberian sturgeon cell lines by commercial transfection reagents. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2019, 55, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.Z.; Gui, L.; Li, Z.Q.; Yuan, X.P.; Zhang, Q.Y. Establishment of a Chinese sturgeon Acipenser sinensis tail-fin cell line and its susceptibility to frog iridovirus. J. Fish Biol. 2008, 73, 2058–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Nam, Y.K.; Gong, S.P. Derivation of the clonal-cell lines from Siberian sturgeon (Acipenser baerii) head-kidney cell lines and its applicability to foreign gene expression and virus culture. J. Fish Biol. 2018, 92, 1273–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, S.; Tafalla, C.; Cuesta, A.; Estepa, A.; Coll, J.M. In vitro search for alternative promoters to the human immediate early cytomegalovirus (IE-cMV) to express the G gene of viral haemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) in fish epithelial cells. Vaccine 2008, 26, 6620–6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Alonso, M.; Alvarez, F.; Estepa, A.; Blasco, R.; Coll, J. A model to study fish DNA immersion vaccination by using the green fluorescent protein. J. Fish Dis. 2001, 22, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashwanth, B.S.; Goswami, M.; Kooloth Valappil, R.; Thakuria, D.; Chaudhari, A. Characterization of a new cell line from ornamental fish Amphiprion ocellaris (Cuvier, 1830) and its susceptibility to nervous necrosis virus. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Teng, Z.; Hou, Y.; Wang, B. Development of oral DNA vaccine based on chitosan nanoparticles for the immunization against reddish body iridovirus in turbots (Scophthalmus maximus). Aquaculture 2016, 452, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jin, Z.; Wang, G.; Ling, F. Mannosylated chitosan nanoparticles loaded with ABP antigen server as a novel nucleic acid vaccine against Nocardia Seriolae infection in Micropterus Salmoides. Aquaculture 2023, 574, 739635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, S.; Abdul Majeed, S.; Nambi, K.S.N.; Madan, N.; Farook, M.A.; Venkatesan, C.; Taju, G.; Venu, S.; Subburaj, R.; Thirunavukkarasu, A.R.; et al. Delivery of DNA vaccine using chitosan–tripolyphosphate (CS/TPP) nanoparticles in Asian sea bass, Lates calcarifer (Bloch, 1790) for protection against nodavirus infection. Aquaculture 2014, 420–421, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, S.; Taju, G.; Nambi, K.S.N.; Abdul Majeed, S.; Sarath Babu, V.; Ravi, M.; Sahul Hameed, A.S. Synthesis and characterization of CS/TPP nanoparticles for oral delivery of gene in fish. Aquaculture 2012, 358–359, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Zhou, K.; Pan, R.; Wei, J.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Y. Oral immunization of carps with chitosan-alginate microcapsule containing probiotic expressing spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) G protein provides effective protection against SVCV infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 105, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, B.M.; Kole, S.; Gireesh-Babu, P.; Sharma, R.; Tripathi, G.; Bedekar, M.K. Evaluation of persistence, bio-distribution and environmental transmission of chitosan/PLGA/pDNA vaccine complex against Edwardsiella tarda in Labeo rohita. Aquaculture 2019, 500, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez, M.I.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Alarcón, F.J.; Martínez, T.F. Comparison of lacZ reporter gene expression in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) following oral or intramuscular administration of plasmid DNA in chitosan nanoparticles. Aquaculture 2017, 474, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E.A.; Relucio, J.L.; Torres-Villanueva, C.A. Gene expression in tilapia following oral delivery of chitosan-encapsulated plasmid DNA incorporated into fish feeds. Mar. Biotechnol. 2005, 7, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Yu, J.; Sun, X. Chitosan microspheres as candidate plasmid vaccine carrier for oral immunisation of Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008, 126, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, S.; Kumari, R.; Anand, D.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, R.; Tripathi, G.; Makesh, M.; Rajendran, K.V.; Bedekar, M.K. Nanoconjugation of bicistronic DNA vaccine against Edwardsiella tarda using chitosan nanoparticles: Evaluation of its protective efficacy and immune modulatory effects in Labeo rohita vaccinated by different delivery routes. Vaccine 2018, 36, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lin, S.L.; Deng, L.; Liu, Z.G. Potential use of chitosan nanoparticles for oral delivery of DNA vaccine in black seabream Acanthopagrus schlegelii Bleeker to protect from Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Fish Dis. 2013, 36, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, F.Q.; Shah, Z.; Cheng, X.J.; Kong, M.; Feng, C.; Chen, X.G. Nano-polyplex based on oleoyl-carboxymethyl-chitosan (OCMCS) and hyaluronic acid for oral gene vaccine delivery. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 145, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalaikumar, E.; Lelin, C.; Sathishkumar, R.; Vimal, S.; Anand, S.B.; Babu, M.M.; Citarasu, T. Oral delivery of pVAX-OMP and pVAX-hly DNA vaccine using chitosan-tripolyphosphate (Cs-TPP) nanoparticles in Rohu, (Labeo rohita) for protection against Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 115, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josepriya, T.A.; Chien, K.H.; Lin, H.Y.; Huang, H.N.; Wu, C.J.; Song, Y.L. Immobilization antigen vaccine adjuvanted by parasitic heat shock protein 70C confers high protection in fish against cryptocaryonosis. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2015, 45, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáez, M.I.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Alarcón, F.J.; Martínez, T.F. Feed pellets containing chitosan nanoparticles as plasmid DNA oral delivery system for fish: In vivo assessment in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) juveniles. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 80, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, Y.; Awad, E.; Buonocore, F.; Arizcun, M.; Esteban, M.; Meseguer, J.; Chaves-Pozo, E.; Cuesta, A. An oral chitosan DNA vaccine against nodavirus improves transcription of cell-mediated cytotoxicity and interferon genes in the European sea bass juveniles gut and survival upon infection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016, 65, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadivand, S.; Soltani, M.; Behdani, M.; Evensen, Ø.; Alirahimi, E.; Hassanzadeh, R.; Soltani, E. Oral DNA vaccines based on CS-TPP nanoparticles and alginate microparticles confer high protection against infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) infection in trout. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 74, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Gao, C.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Yin, J.; Li, Y.; Zeng, W.; Bergmann, S.M.; Wang, Q. Recombinant Baculovirus-Produced Grass Carp Reovirus Virus-Like Particles as Vaccine Candidate That Provides Protective Immunity against GCRV Genotype II Infection in Grass Carp. Vaccines 2021, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyaf Dezfuli, B.; Lorenzoni, M.; Carosi, A.; Giari, L.; Bosi, G. Teleost innate immunity, an intricate game between immune cells and parasites of fish organs: Who wins, who loses. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1250835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.D.; Dong, W.T.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.J.; Liu, J.X.; Zhao, X.X. A recombinant adenovirus targeting typical Aeromonas salmonicida induces an antibody-mediated adaptive immune response after immunization of rainbow trout. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 133, 103559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, H. Improvement and applications of adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV-2) system for efficient gene transfer and expression in penaeid shrimp cells. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 32, 101700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.B.; Alves, P.M.; Aunins, J.G.; Carrondo, M.J. Use of adenoviral vectors as veterinary vaccines. Gene Ther. 2005, 12 (Suppl. 1), S73–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhr, A.I. DNA Vaccines: Regulatory Considerations and Safety Aspects. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2017, 22, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasala, D.; Yoon, A.R.; Hong, J.; Kim, S.W.; Yun, C.O. Evolving lessons on nanomaterial-coated viral vectors for local and systemic gene therapy. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 1689–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, S.R.; Kim, S.Y.; Jang, K.Y.; Lee, K.C.; Yi, H.K.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Hwang, P.H. N-hexanoyl chitosan-stabilized magnetic nanoparticles: Enhancement of adenoviral-mediated gene expression both in vitro and in vivo. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2008, 4, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.J.; Kang, E.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, S.W.; Yun, C.O. Therapeutic targeting of chitosan-PEG-folate-complexed oncolytic adenovirus for active and systemic cancer gene therapy. J. Control. Release 2013, 169, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, T.; Swain, P.; Sahoo, S.K. Antigen in chitosan coated liposomes enhances immune responses through parenteral immunization. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2011, 11, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Gan, L.; Yang, X.; Xu, H. Chitosan as a condensing agent induces high gene transfection efficiency and low cytotoxicity of liposome. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2011, 111, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Long, M.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Qu, M.; Ge, X.; Nan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. Chitosan-alginate/R8 ternary polyelectrolyte complex as an oral protein-based vaccine candidate induce effective mucosal immune responses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, B.B.M.; Mertins, O.; Silva, E.R.D.; Mathews, P.D.; Han, S.W. Arginine-modified chitosan complexed with liposome systems for plasmid DNA delivery. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 193, 111131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yang, Y.; Hong, E.K.; Yin, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D. Analyzing the structure-activity relationship of raspberry polysaccharides using interpretable artificial neural network model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-del Rio, L.; Diaz-Rodriguez, P.; Landin, M. Design of novel orotransmucosal vaccine-delivery platforms using artificial intelligence. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 159, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Gan, L.; Yang, X.; Tan, Z.; Shi, H.; Lai, C.; Zhang, D. Progress of AI assisted synthesis of polysaccharides-based hydrogel and their applications in biomedical field. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 287, 138643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharifar, H.; Amani, A. Size, Loading Efficiency, and Cytotoxicity of Albumin-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles: An Artificial Neural Networks Study. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.W.; Manan, S.; Alabbosh, K.F.; Ul-Islam, M.; Atta, O.M.; Khan, A.A.; Fan, Y.; Khan, K.A.; Elboughdiri, N.; Wang, Z. Bacterial polysaccharides in the food industry: Synthesis-structure-properties relationships, AI-driven innovations, regulatory challenges, and bioeconomy prospects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 370, 124343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.; Sharma, A.; Jaiswal, S.; Fatma, S.; Arora, V.; Iquebal, M.A.; Nandi, S.; Sundaray, J.K.; Jayasankar, P.; Rai, A.; et al. Development of Antimicrobial Peptide Prediction Tool for Aquaculture Industries. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2016, 8, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Ding, L.; Xu, Z. Immunoglobulins, Mucosal Immunity and Vaccination in Teleost Fish. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 567941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, S.; Das, S.K.; Samal, J.; Thatoi, H.N. Epidermal mucus, a major determinant in fish health: A review. Iran. J. Vet. Res. 2018, 19, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Tasumi, S.; Tsutsui, S.; Okamoto, M.; Suetake, H. Molecular diversity of skin mucus lectins in fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003, 136, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakers, S.; Niklasson, L.; Steinhagen, D.; Kruse, C.; Schauber, J.; Sundell, K.; Paus, R. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) from fish epidermis: Perspectives for investigative dermatology. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubashynskaya, N.V.; Petrova, V.A.; Skorik, Y.A. Biopolymer Drug Delivery Systems for Oromucosal Application: Recent Trends in Pharmaceutical R&D. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaetzel, C.S. The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor: Bridging innate and adaptive immune responses at mucosal surfaces. Immunol. Rev. 2005, 206, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthachalam, B.V.; Zwolak, A.; Lin-Schmidt, X.; Keough, E.; Tamot, N.; Venkataramani, S.; Geist, B.; Singh, S.; Ganesan, R. Discovery and characterization of single-domain antibodies for polymeric Ig receptor-mediated mucosal delivery of biologics. mAbs 2020, 12, 1708030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

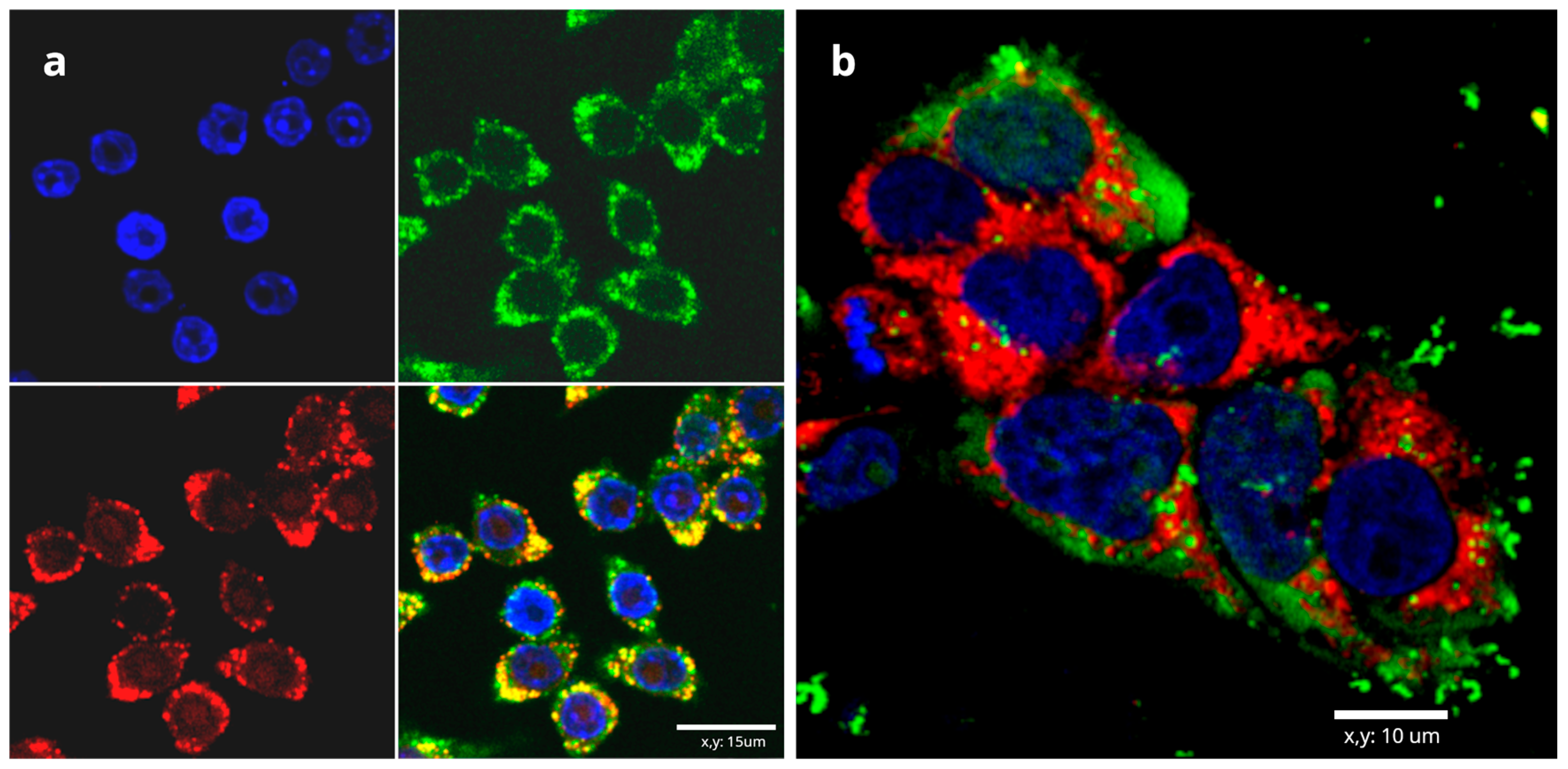

- Zubareva, A.A.; Shcherbinina, T.S.; Varlamov, V.P.; Svirshchevskaya, E.V. Intracellular sorting of differently charged chitosan derivatives and chitosan-based nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 7942–7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubareva, A.; Shagdarova, B.; Varlamov, V.; Kashirina, E.; Svirshchevskaya, E. Penetration and toxicity of chitosan and its derivatives. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 93, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Wood, E.; Dornish, M. Effect of chitosan on epithelial cell tight junctions. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranaldi, G.; Marigliano, I.; Vespignani, I.; Perozzi, G.; Sambuy, Y. The effect of chitosan and other polycations on tight junction permeability in the human intestinal Caco-2 cell line(1). J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kong, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, D.; Yu, X.; Cheng, X.; Feng, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X. Mechanism of surface charge triggered intestinal epithelial tight junction opening upon chitosan nanoparticles for insulin oral delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J.; Wiegertjes, G.F. Long-lived effects of administering β-glucans: Indications for trained immunity in fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016, 64, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rességuier, J.; Dalum, A.S.; Du Pasquier, L.; Zhang, Y.; Koppang, E.O.; Boudinot, P.; Wiegertjes, G.F. Lymphoid Tissue in Teleost Gills: Variations on a Theme. Biology 2020, 9, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Huang, X.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Immune response of large yellow croaker Larimichthys crocea towards a recombinant vaccine candidate targeting the parasitic ciliate Cryptocaryon irritans. Aquac. Int. 2023, 31, 3383–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, T.; Toda, H.; Shibasaki, Y.; Somamoto, T. Cytotoxic T cells in teleost fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011, 35, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas, I. The Mucosal Immune System of Teleost Fish. Biology 2015, 4, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampim, I.T.; Wiggers, H.J.; Bueno, C.Z.; Chevallier, P.; Copes, F.; Mantovani, D. Sourcing Interchangeability in Commercial Chitosan: Focus on the Physical–Chemical Properties of Six Different Products and Their Impact on the Release of Antibacterial Agents. Polymers 2025, 17, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Som, C.; Schmutz, M.; Borges, O.; Borchard, G. How the Lack of Chitosan Characterization Precludes Implementation of the Safe-by-Design Concept. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manigandan, V.; Karthik, R.; Ramachandran, S.; Rajagopal, S. Chapter 15—Chitosan Applications in Food Industry. In Biopolymers for Food Design; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 469–491. [Google Scholar]

- Lunkov, A.P.; Zubareva, A.A.; Varlamov, V.P.; Nechaeva, A.M.; Drozd, N.N. Chemical modification of chitosan for developing of new hemostatic materials: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baffetta, F.; Cecchi, R.; Guerrini, E.; Mangiavacchi, S.; Sorrentino, G.; Stranges, D. Relationship between Endotoxin Content in Vaccine Preclinical Formulations and Animal Welfare: An Extensive Study on Historical Data to Set an Informed Threshold. Vaccines 2024, 12, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kean, T.; Thanou, M. Biodegradation, biodistribution and toxicity of chitosan. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizeq, B.R.; Younes, N.N.; Rasool, K.; Nasrallah, G.K. Synthesis, Bioapplications, and Toxicity Evaluation of Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetranjiwalla, S.; Ononiwu, A. Identifying barriers to scaled-up production and commercialization of chitin and chitosan using green technologies: A review and quantitative green chemistry assessment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zubareva, A.; Svirshchevskaya, E.; Nedoluzhko, A.; Skorik, Y.A. Chitosan and Alginate in Aquatic Vaccine Development. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040111

Zubareva A, Svirshchevskaya E, Nedoluzhko A, Skorik YA. Chitosan and Alginate in Aquatic Vaccine Development. Polysaccharides. 2025; 6(4):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040111

Chicago/Turabian StyleZubareva, Anastasia, Elena Svirshchevskaya, Artem Nedoluzhko, and Yury A. Skorik. 2025. "Chitosan and Alginate in Aquatic Vaccine Development" Polysaccharides 6, no. 4: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040111

APA StyleZubareva, A., Svirshchevskaya, E., Nedoluzhko, A., & Skorik, Y. A. (2025). Chitosan and Alginate in Aquatic Vaccine Development. Polysaccharides, 6(4), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040111