Abstract

Background: Chitosan and Lavandula angustifolia (lavender) exhibit antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects, making them potential candidates for managing infected wounds. This study investigated the therapeutic efficacy of a chitosan nanoparticle-loaded hydrogel, lavender extract, and their combination in treating Staphylococcus aureus-infected wounds in rats. Methods: Forty-eight male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g, 8–10 weeks) were divided into six groups: healthy control, infected untreated, Fucidin, lavender extract, chitosan hydrogel, and chitosan–lavender combination. Wound healing was evaluated on days 3, 7, and 14 using clinical assessment, histopathology, and biochemical markers. Non-parametric statistical tests were applied, with significance set at p < 0.05. Results: The chitosan–lavender group showed the most pronounced healing response, with significantly reduced WBC counts, lower levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and MDA, and enhanced SOD activity (p < 0.05). Histological analysis confirmed superior re-epithelialization, granulation tissue development, collagen deposition, and wound contraction in chitosan-based treatments, particularly their combination, compared to lavender or Fucidin alone (p < 0.001). Inflammatory infiltrates, angiogenesis, necrosis, and hemorrhage were also notably reduced across treated groups. Conclusions: Combining chitosan hydrogel with lavender extract exerts synergistic antibacterial and wound healing effects, offering a promising alternative therapy for infected wounds.

1. Introduction

The skin serves as a defensive barrier against pathogen invasion. The alteration of the normal anatomical structure due to surgical procedures or chemical, physical, mechanical, and thermal events, leading to a disruption of skin functions, results in a wound [1]. Wound healing is intricate and entails a sequence of coordinated and overlapping phases that must converge to restore skin integrity. The stages include a variety of discrete but frequently interconnected events, including coagulation, inflammation, migration, proliferation, regeneration, and remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM). Wound healing starts with hemostasis and continues with an inflammatory phase, a proliferative phase ending in re-epithelization, and a remodeling phase wherein the scar develops [2,3]. Once the skin is compromised, typical microorganisms from the normal skin flora, along with exogenous bacteria and fungus, can rapidly infiltrate the underlying tissues, which provide a moist, warm, and nutrient-rich environment [4]. Staphylococcus aureus, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are the dominant microbial strains present in patients with infected wounds [5]. As antibiotics are increasingly being tolerated by pathogenic strains, individuals are currently utilizing an extensive array of bioresources. These consist primarily of herbs but may also incorporate animal and mineral components [6]. Skin regeneration and infection prevention are complicated procedures in wound healing. Both local and systemic therapies are employed in wound healing. However, localized treatment may be a more advantageous approach to reduce side effects, enhance efficacy, and overcome antibiotic resistance [7]. Current wound healing therapies typically fail to achieve favorable clinical results, either structurally (e.g., wound re-epithelialization, fluid loss management) or functionally (e.g., histological characteristics affecting elasticity, durability, sensitivity, etc.). Therefore, nanotechnology, due to its diverse physicochemical features, is a dependable field of research for wound healing therapies. By altering the material type, size, and electrical charge of the nanoparticles, their biochemical characteristics, including hydrophobicity, interaction with biological targets, and tissue penetration depth, may be readily optimized for various wound types [8].

Chitin and its deacetylated derivative, chitosan, include a series of linear polysaccharides comprising differing quantities of (β1 → 4) linked residues of Nacetyl-2-amino-2-deoxy-D-glucose (glucosamine, GlcN) and 2-amino-2-deoxy-Dglucose (N-acetyl-glucosamine, GlcNAc) residues. Chitosan dissolves in aqueous acidic environments through the protonation of primary amines. Chitin is a prevalent biopolymer present in the exoskeletons of crustaceans, the cuticles of insects, algae, and the cell walls of fungi. Chitosan rarely occurs in nature, although it is primarily present in some fungi of the Mucoraceae family. Historically, commercial chitosan samples were predominantly derived from the chemical deacetylation of chitin sourced from crustaceans. Chitosan derived from fungi is increasingly attracting market interest [9]. Chitosan demonstrates numerous biological activities, including antitumoral, antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, making it suitable for application as a therapeutic polymer [10].

Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) is among the most valued plants utilized in cosmetics and aromatherapy. It possesses deodorizing, calming, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties [11]. The most valuable component of the plant is the flowers, which contain up to 4.5% essential oil. The primary constituents of the oil include esterified and free linalool, camphor, and cineole [12]. The leaves generally possess higher concentrations of camphor and cineole compared to the flowers, resulting in a more potent leaf oil. Alongside the oil, there are components like tannins, phenolic acids, flavones, anthocyanidins, saponins, polyphenols, and minerals [13].

Previous studies have shown that chitosan supports tissue repair by promoting the migration of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells while also enhancing re-epithelialization and normal skin regeneration. Given these properties, it is proposed that combining chitosan with medical plant extract, both of which exhibit similar regenerative effects, may further accelerate wound recovery and demonstrate synergistic activity [14].

The use of plant extracts incorporated into nanoemulsion systems combined with nanofiber dressings represents a promising new strategy for enhancing wound healing [15].

This study introduces a novel approach to wound healing by combining chitosan nanoparticles with a hydrogel matrix and Lavandula angustifolia extract. Unlike previous research that has primarily focused on either nanomaterials or herbal extracts in isolation, our investigation uniquely combines these two modalities to enhance antimicrobial efficacy and promote tissue regeneration in the context of Staphylococcus aureus-infected wounds, addressing the need for alternatives to chemical antimicrobial agents. By demonstrating the enhanced antimicrobial efficacy and tissue regeneration capabilities of this natural nanocomposite in treating Staphylococcus aureus-infected wounds in a rat model, our research highlights a promising strategy that merges natural bioactive agents with nanotechnology, paving the way for innovative and biocompatible wound management solutions. This study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of chitosan nanoparticle-loaded hydrogel, Lavandula angustifolia extract, and their combination in wound healing.

2. Materials and Methods

An experimental, randomized, controlled animal study was conducted at The Department of Pharmacology, College of Medicine/Baghdad University and The Iraqi Center for Cancer Research and Medical Genetics/Mustansiriyah University. This research was conducted from October 2024 to August 2025.

All of the experimental work was implemented following protocol review by the Iraqi Board Review of the College of Medicine/Baghdad University after being approved by the scientific committee of the Department of Pharmacology at the College of Medicine/Baghdad University.

All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the international guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th edition) and complied with the ethical standards set by the College of Medicine, University of Baghdad.

Approval Number: 35.

Date of Approval: [6 October 2024].

2.1. Lavandula angustifolia Collection and Preparation of the Essential Oil

Lavandula angustifolia leaves were collected from the mountains of Sulaimani, Kurdistan region of Iraq, in September 2024. Collection was carried out in the field under the supervision of a researcher to avoid contaminants. The collected plant was identified and confirmed at Baghdad University/Iraq Natural History Research Center and Museum. The plant was cleaned, dried in the shade at room temperature, and extracted at the Ministry of Science and Technology (Environment, Water, and Renewable Energy Directorate). Essential oil of L. angustifolia was extracted using hydro distillation of every 100 g of dried crushed leaves in 500 mL of distilled water utilizing a Clevenger-type apparatus for 4 h. Every 100 g of the plant produces about 5 ml of oil. The essential oil was extracted, centrifuged, separated from the upper layer, and preserved in amber bottles at +4 °C until use [16]. Although the present study demonstrates potential benefits of the chitosan–lavender formulation in a rat model, essential oils, such as lavender, have inherent variability depending on source and extraction. Regulatory approval for clinical use would require rigorous standardization, quality control, and further safety and efficacy studies in humans [11].

2.2. Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticle-Loaded Hydrogel

Preparation of chitosan nanoparticle-loaded hydrogel involved reacting chitosan using a Dean–Stark (Clevenger) apparatus Dean–Stark (Schott Duran/Germany) with xylene to extract water. The chitosan amide was separated through filtration, washed with methanol, hot distilled water, and ethanol, and then dried at 50 °C. Chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs) were synthesized via ionic gelation using TPP and chitosan. Chitosan was dissolved in 1% acetic acid until clear, and then TPP was added at a 1:2.5 (w/w) ratio with continuous stirring for 6 h at room temperature. The resulting nanoparticles were separated through centrifugation and washed multiple times, and the supernatant discarded, leaving the precipitate, which was re-suspended in water [17,18].

2.3. Preparation and Charactarization of Chitosan–Lavandula angustifolia Nanoemulsion

The preparation involved reacting chitosan using a Dean–Stark (Clevenger) apparatus with xylene to extract water. The chitosan amide product was separated through filtration, washed with methanol, hot distilled water, and ethanol, and then dried at 50 °C and weighed [17,18]. Chitosan was dissolved in 1% acetic acid until clear, and Tween 80 (1%) was added as a surfactant. Lavender oil was gradually incorporated with continuous stirring to form a stable emulsion. TPP solution was added dropwise under high-speed stirring, where ionic interactions crosslinked chitosan chains, encapsulating the lavender oil into nanoparticles. Sonication was used to reduce particle size and ensure uniformity [19]. Characterization of the chitosan nanoparticle-loaded hydrogel and the nanoemulsion was performed by the Ministry of Science and Technology in Iraq, using techniques like UV-Vis spectroscopy, FTIR, SEM, EDX, AFM, and XRD to confirm their nano properties.

- Visible Absorption Spectroscopy

UV-VIS double beam spectrophotometers were used to measure the absorbance spectra of the lavender/CSNPs solution. All spectra were taken in a quartz cell with a 1 cm optical path at room temperature. As a control, deionized distilled water was utilized. Absorption was calculated using 200–800 nm. The concentrated samples were diluted at 1:10 [20]. The measurements were investigated by the Ministry of Science and Technology in Iraq.

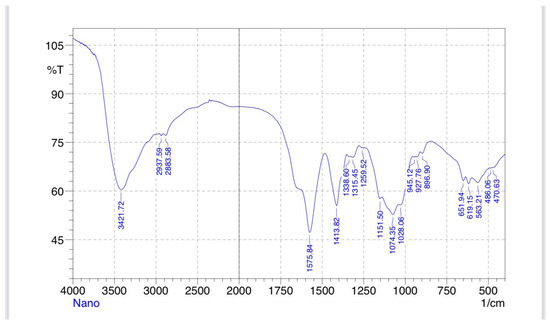

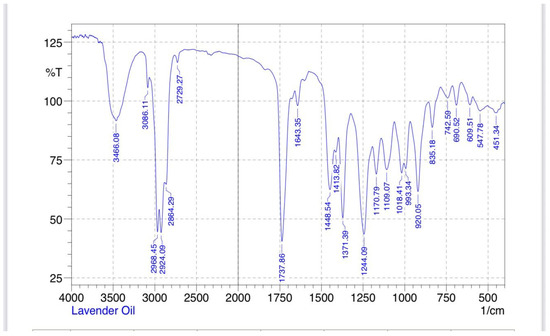

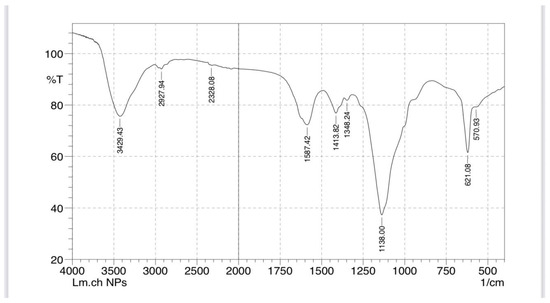

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis (FTIR)

The characterization of functional groups on the surface of chitosan and lavander/chitosanNPs was investigated through FTIR analysis (Shimadzu), and the spectra were scanned at a resolution of 4 cm−1 in the range of 400–4000 cm−1. By spreading the samples on a microscope slide, the samples were produced according to standard methods [20]. Each sample was prepared as a pellet in potassium bromide (KBr) at a 1:99 ratio of sample to KBr for FTIR. After that, the sample was subjected to examination [21]. The measurements were investigated by the Ministry of Science and Technology in Iraq.

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) was employed to analyze the morphology of the nanoparticles that were formed. The samples were morphologically characterized using a Brucker Scanning Electron Microscope. By spreading the materials on a glass slide, the samples were prepared according to standard methods (almost seven drops on the slide). After then, the sample was put through its tests [22]. A small drop of each type of nanoparticle was placed on a carbon-coated copper grid and allowed to dry using the mercury lamp for 5 min. Then, readings were taken at a magnification of 5000×, 10,000×, 20,000×, and 50,000× and with steady voltage [23].

- Energy Dispersive X-Ray (EDX)

EDX was used in combination with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) and the transmission operation mode of the SEM. EDX analysis was performed via EDX Oxford instruments INCA 350 with the Si detector comprising a 10 mm2 area and resolution at Mn 133 eV [24].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

The surface morphology of the nanoparticles was visualized using an Atomic Force Microscope in contact mode under normal atmospheric conditions. Samples of nanoparticle solution were dropped on a glass slide (1 × 2 cm), the samples were dried, the slide was dispersed on the AFM sample stage, and analysis was carried out according to the standard procedure [25]. AFM analysis was performed by the Ministry of Science and Technology in Iraq.

- X-Ray Diffractometer (XRD)

A thin film of uniformly suspended water with each type of nanoparticle was prepared on a glass slide and kept for drying. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded by employing an X-ray diffractometer at 2θ/θ scanning mode (operational voltage 40 kV and current 30 mA, Cu K (a) radiation λ = 1.540) [26]. Data were recorded for the 2θ range of 10 to 80 degrees with a step of 0.0200 degree. The result obtained from the XRD pattern was interpreted based on the standard reference of the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS card number 04-0783) for the characterization of AgNPs [27]. The particle size of the prepared samples was determined by using the Debye–Scherrer equation, as follows:

where D is the crystal size, λ is the wavelength of the X-ray, θ is the diffraction angle (Braggs angle) in radians, and β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the peak in radians [27].

D = 0.9λ/β cosθ

2.4. Preparation of Staphylococcus aureus Suspension

Staphylococcus aureus was sourced from a patient with an infected wound in Ghazi Al-Hariri hospital for surgical specialties, and bacteria were cultivated on nutrient agar for 24 h at 37 °C under aerobic conditions. Following confirmation of their viability and purity using the Vitek2 system (Bio number 050602062361231), a pure colony was aseptically transferred into BHI broth and incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h, resulting in turbid broth indicating bacterial growth. Turbidity was adjusted to the 0.5 McFarland standard (1 × 108 CFU/mL) [28].

2.5. In Vitro Antimicrobial Test of Lavandula angustifolia Extract Using Agar Well Diffusion Method

For in vitro antimicrobial testing, Mueller–Hinton agar plates were evenly inoculated with the bacterial suspension. Wells 6–8 mm in diameter were punched into the agar, and 20–100 µL of Lavandula angustifolia extract at various concentrations (2.5%, 5%, 10%, 20%) in Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) were added. The plates were incubated, allowing the extract to diffuse and inhibit bacterial growth. Zones of inhibition were measured to determine the effective concentration [29]. As shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Antimicrobial effect of different concentrations of Lavandula angustifolia extract.

2.6. Experimental Design and Preparation of Experimental Animals

Forty-eight Sprague-Dawley male rats (weighing 250–350 g and ranging in age from 8 to 10 weeks) were included in the experiment. Random allocation of animals into groups was performed. Furthermore, the investigators conducting the histopathological evaluations were blinded to group allocations to prevent observational bias. Animals were obtained from the Iraqi Center for Cancer Research and Medical Genetics. Before the experiment, the animals were acclimatized for two weeks at the same location where they were obtained. The animals were housed in separate polypropylene cages with consistent 12 h light/dark cycles and temperature and humidity levels (40–60%). Water and standard food pellets were provided ad libitum. Each animal was anaesthetized with an intramuscular injection of a ketamine and xylazine mixture at dosages of 20 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg, respectively [30]. The dorsal region of the animals was cleaned with 70% ethanol and shaved. A full-thickness circular excision wound (1.5 cm in diameter) was created using a sterilized surgical blade [31]. Ten microliters of the previously prepared bacterial suspension was applied to the wound and spread with the aid of a sterile swab to wounds of infected animal groups [28].

2.7. Induction of Staphylococcus aureus-Infected Excisional Wound

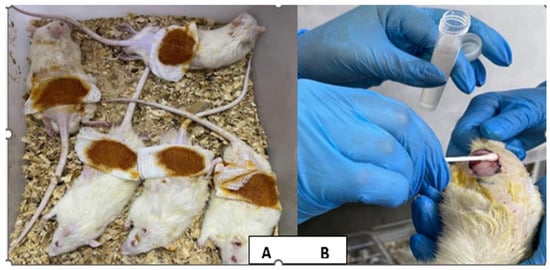

Each animal was anaesthetized with an intramuscular injection of a ketamine and xylazine mixture at dosages of 20 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg, respectively [30]. The dorsal region of the animals was cleaned with 70% ethanol and shaved. A full-thickness circular excision wound (1.5 cm in diameter) was created using a sterilized surgical blade [31]. Ten microliters of the previously prepared bacterial suspension was applied to the wound and spread with the aid of a sterile swab to wounds of infected animal groups [28] (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 2.

(A) Excisional wound of the rat on the first day. (B) Application of the bacterial suspension to the wound.

Study groups.

After confirming the induction of excisional wound infection, a total of 48 rats were divided randomly into six groups (each group consisted of 8 rats), as follows:

- 1-Group 1: Members of this group were normal and healthy, without any intervention.

- 2-Group 2: Infected excisional wounds were only treated with normal saline 0.9% topically.

- 3-Group 3: Infected excisional wounds were treated with 2% sodium fusidate ointment topically for 13 days.

- 4-Group 4: Infected excisional wounds were treated with 2.5% v/v Lavandula angustifolia extract topically for 13 days.

- 5-Group 5: Infected excisional wounds were treated with 2% w/v chitosan nanoparticle-loaded hydrogel topically for 13 days.

- 6-Group 6: Infected excisional wounds were treated with a chitosan (1% w/v) + Lavandula angustifolia (1% v/v) nanoemulsion combination topically for 13 days.

All topical formulations were applied two times daily for 13 days. At the end of the experiment, the animals were humanely euthanized on day 14 in accordance with [ethical approval number]. Immediately following euthanasia, full-thickness skin samples were removed, fixed in 10% formalin for 24–48 h, and processed for histological examination.

2.8. Tissue Sampling and Processing for Histopathological Study

Tissue sampling and processing for histopathological study were performed according to Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques [32]. A piece of healed skin was excised from each animal after confirmation on day 14. The specimens were fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h and then dehydrated through sequential immersion for 2 h in each concentration of ethanol (70%, 80%, 95%, and 100%). The specimens were cleared from ethanol by immersing them in xylene for an additional 2 h. Paraffin impregnation, infiltration, and penetration were carried out using molten paraffin (55–60 °C) for 2 h. The specimens were then cooled in an L-shaped metal template. Upon solidification, the paraffin blocks were sectioned using a rotary microtome, obtaining sections of 5 μm thickness. The sections were attached to slides after being floated on a water bath (45–48 °C) and then allowed to settle on clean glass slides. Deparaffinization was performed by removing excess paraffin from the sections after 30 min in an oven at 65 °C.

Sections were examined using a light microscope at different magnifications (10× and 40×) to evaluate histopathological changes according to the semi-quantitative wound scoring system [33]. The healing process was scored into four categories (scores of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4) based on the level of the following essentials of healing: re-epithelialization, granulation tissue formation, collagen deposition, inflammatory cell infiltration, angiogenesis, hemorrhage, and necrosis/degeneration.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS v.26. Data were represented as tables and figures. All continuous variables were non-normally distributed, so they were reported as medians with an interquartile range (IQR). For within-group comparisons of these non-normally distributed variables, we used the Mann–Whitney U test instead of the independent t-test; the Kruskal–Wallis Test instead of the one-way ANOVA test; and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test instead of the paired t-test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

This study included six groups, with eight rats in each group. These groups were as follows: apparently healthy (control group), induced non-treated group, induced treated topically with Fucidin ointment 2% (sodium fusidate 20 mg/g) twice daily for 14 days (Fucidin group), induced treated topically with Lavandula angustifolia extract 2.5 mg/mL twice daily for 14 days (Lavandula group), induced treated topically with chitosan nanoparticle hydrogel 2% W/V twice daily for 14 days (chitosan group), and induced treated topically with chitosan nanoparticles and Lavandula angustifolia nanoemulsion combination applied twice daily for 14 days (chitosan and Lavandula group).

The comparison of the studied groups was performed using the hematological biomarker of White Blood Cell (WBC) count; skin tissue homogenate (TNF-α, IL-6, MDA, and SOD); wound contraction percentage; and a semi-quantitative wound scoring system (re-epithelization, granulation, tissue formation, collagen deposition, inflammatory infiltrate, angiogenesis, hemorrhage, and necrosis/degeneration).

A comparison between the apparently healthy control group and the induced non- treated group in relation to different measured parameters was performed.

The induced non-treated group had levels of WBC on days 7 and 14 and ELISA biomarkers on day 14 (TNF-α, IL-6, and MDA) that were significantly increased in comparison with the apparently healthy control group, p < 0.001.

Meanwhile, the level of SOD was significantly decreased in the induced non-treated group in comparison with the apparently healthy control group, p < 0.001 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison between apparently healthy control group and induced non-treated group in relation to different measured parameters (hematological biomarker (WBC count) and ELISA biomarkers on day 14 (TNF-α, IL-6, MDA, and SOD)).

The induced non-treated group showed that granulation tissue formation, inflammatory infiltrate, angiogenesis, hemorrhage, and necrosis/degeneration were significantly increased in comparison to the apparently healthy control group, p < 0.001.

Meanwhile, re-epithelization and collagen deposition were significantly decreased in the induced non-treated group in comparison to the apparently healthy control group, p < 0.001 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison between apparently healthy control group and induced non-treated group in relation to semi-quantitative wound scoring system.

The comparison between the induced non-treated group and the induced then treated groups is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison between induced groups (induced non-treated group, Fucidin group, Lavandula group, chitosan group, and chitosan and Lavandula group) in relation to different measured parameters (hematological biomarker (WBC count) and ELISA biomarkers on day 14 (TNF-α, IL-6, MDA, and SOD)).

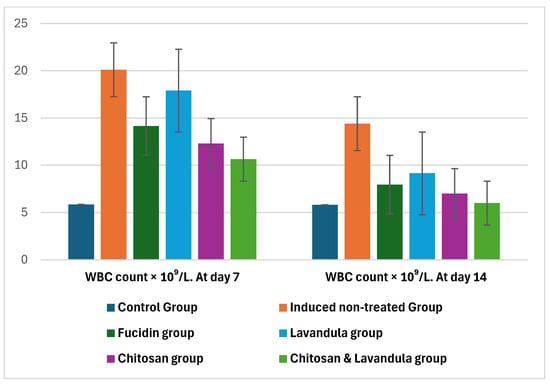

On days 7 and 14, the lowest WBC level was observed in the chitosan and Lavandula group, with significant differences from the other groups, p < 0.001.

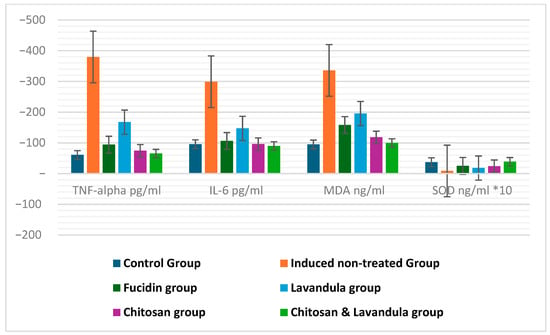

Similarly, the lowest LISA biomarker levels on day 14 for TNF-α, IL-6, and MDA were observed in the chitosan and Lavandula group, with significant differences from the other groups, p < 0.001.

Also, the highest level of SOD was observed in the chitosan and Lavandula group in comparison with other groups, p < 0.001 Table 3, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Comparison between induced groups (induced non-treated group, Fucidin group, Lavandula group, chitosan group, and chitosan and Lavandula group) in relation to hematological biomarker (WBC count) on days 7 and 14 of therapy; bars represent the median (IQR).

Figure 4.

Comparison between induced groups (induced non−treated group, Fucidin group, Lavandula group, chitosan group, and chitosan and Lavandula group) in relation to ELISA biomarkers on day 14: TNFα, IL−6, MDA, and SOD. Bars represent the median (IQR). IL = interleukin; TNF−a = tumor necrosis factor alpha; MDA = malondialdehyde; SOD = superoxide dismutase.

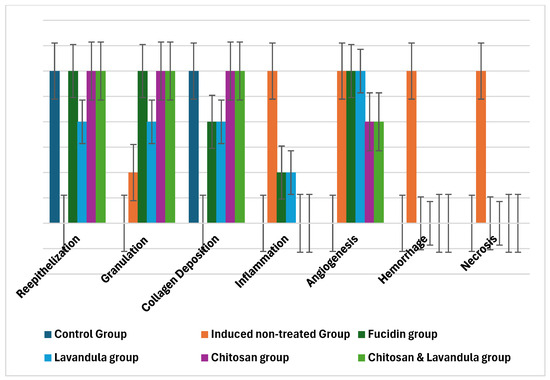

The semi-quantitative wound scoring system showed that re-epithelization, granulation tissue formation, and collagen deposition were significantly higher in both the chitosan group and the chitosan and Lavandula group in comparison to the other groups after 14 days of therapy; p < 0.001.

Also, inflammatory infiltrate and angiogenesis were significantly lower in both the chitosan group and the chitosan and Lavandula group in comparison to other groups after 14 days of therapy; p < 0.001.

Hemorrhage and necrosis/degeneration were significantly decreased among all induced and then treated groups in comparison to the induced non-treated group, p < 0.001.

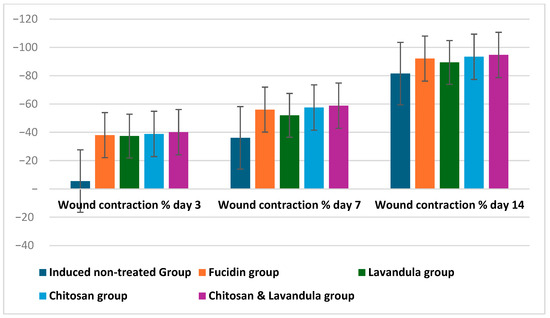

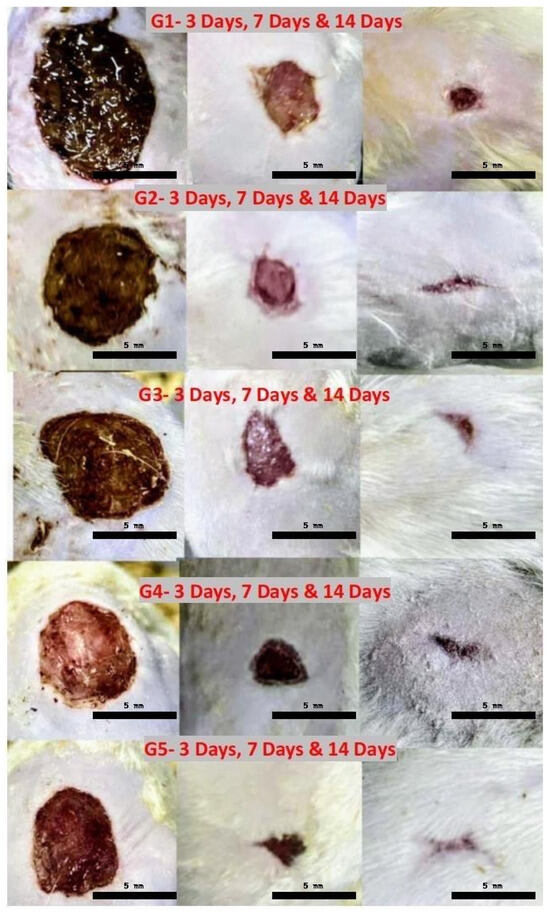

Wound contraction % on days 3, 7, and 14 of therapy was significantly increased among all induced and then treated groups in comparison to the induced non-treated group, but the highest increase was observed in the chitosan and Lavandula group, p < 0.001. Table 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Table 4.

Comparison between induced groups (induced non-treated group, Fucidin group, Lavandula group, chitosan group, and chitosan and Lavandula group) in relation to the semi-quantitative wound scoring system and wound contraction %.

Figure 5.

Comparison between induced groups (induced non−treated group, Fucidin group, Lavandula group, chitosan group, and chitosan and Lavandula group) in relation to semi−quantitative wound scoring system. Bars represent the median (IQR).

Figure 6.

Comparison between induced groups (induced non−treated group, Fucidin group, Lavandula group, chitosan group, and chitosan and Lavandula group) in relation to wound contraction %. Bars represent the median (IQR).

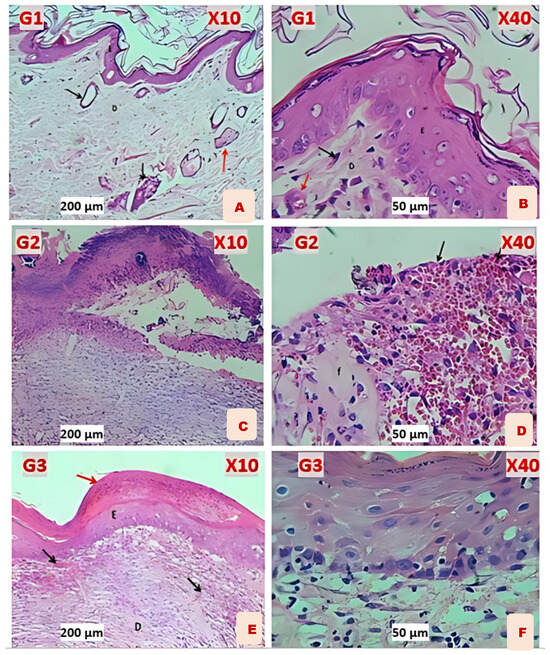

3.1. Histopathological Results

-G1 (Healthy control)

The histopathological figures of the skin revealed a normal appearance of the epidermis lining epithelial cells, a normal appearance of dermal collagen fibers with blood vessels, fibroblasts and fibrocytes with normal sweat glands, and hair follicles with related sebaceous glands as shown in Figure 7A,B.

Figure 7.

(A) G1: Normal appearance of epidermis lining epithelial cells (E), normal dermal collagen fibers and cells (D), sweat gland with duct (black arrow), and sebaceous glands (red arrow). (B) G1: shows lining epithelial cells (E), normal dermal collagen fibers with capillaries (D), and fibroblasts (black arrow) and blood vessel (red arrow). (C) G2 (Induction): shows skin ulcer covered by thick layer of necrotic tissue, thick fibrin deposition, degeneration with necrosis of fibrous tissue, and infiltration of MNLs. (D) G2: shows hemorrhagic dermal ulcer (black arrows), fibrin deposition (F), and degeneration with necrosis of fibrous tissue. (E) G3 Fucidin: shows hyperkeratosis (red arrow), re−epithelization (E), and immature fibrous tissue (D) with marked angiogenesis (black arrows). (F) G3: shows well−regenerated epidermis epithelium, sub−epithelial angiogenesis, and little infiltration of leukocytes.

-G2 (Induction)

All histopathological figures of the skin revealed severe ulcerative dermatitis characterized by depressed areas of skin and complete loss of the epidermis; the dermis revealed hemorrhagic ulcers with fibrin deposition, degeneration with necrosis of fibrous connective tissue, vascular congestion, and infiltration of mononuclear leukocytes as shown in Figure 7C,D.

-G3 (Fucidin treatment)

Almost all histopathological figures of the skin revealed normal epidermis keratinized stratified squamous epithelium (complete epithelization). The dermis revealed immature fibrous tissue with marked angiogenesis and little sub−epidermis infiltration of leukocytes. Some figures revealed hyperkeratosis with re−epithelization of the epidermis and the dermis comprising immature fibrous tissue with marked angiogenesis as shown in Figure 7E,F.

-G4 (Lavandula treatment)

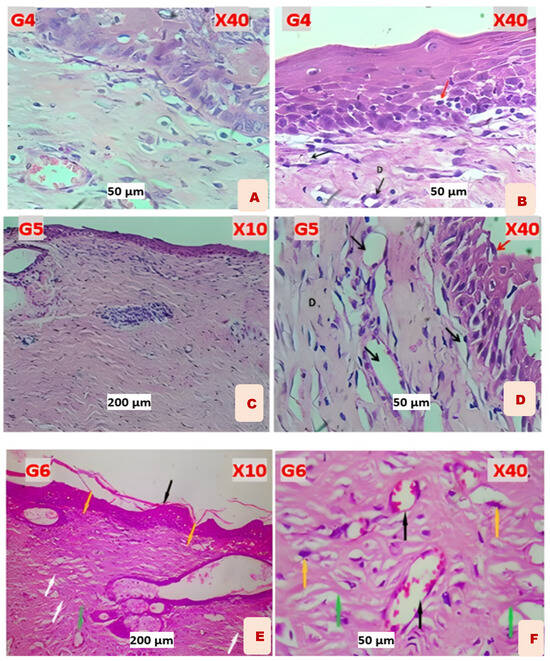

Almost all histopathological figures of the skin revealed incomplete re−epithelization of epidermis non−keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, which showed mitotic figures of the stratum basalis. The dermis comprised immature dermal collagen fibers with marked angiogenesis and few infiltrated mononuclear leukocytes as shown in Figure 8A,B.

Figure 8.

(A) G4 Lavandula: reveals marked dermal papilla within the epidermis, with immature dermal collagen fibers and marked angiogenesis. (B) G4: reveals a well−regenerated epidermis that showed few intra−epithelial leukocytes (red arrow) and immature dermal collagen fibers (D) with marked angiogenesis (black arrows). (C) G5 Chitosan: shows re−epithelization of the epidermis, a dermis comprising mature fibrous tissue with marked angiogenesis, and no infiltration of leukocytes. (D) G5: shows re−epithelization of the epidermis (red arrow), a dermis comprising mature fibrous tissue (D) with marked angiogenesis (black arrows), and no infiltration of leukocytes. (E) G6 Chitosan and Lavandula: shows epidermal re−epithelization with keratinized stratified squamous epithelium (black arrow). Matured granulation tissue formation (yellow arrow), with more prominent fibroblast proliferation and collagen fiber deposition, with more mature collagen fiber deposition (white arrow). Moderate angiogenesis with very few inflammatory cell infiltrates (green arrow). (F) G6: shows mature dermal granulation tissue showing more matured fibrous tissue, with more prominent proliferative fibroblasts (yellow arrow), and coarse collagen fiber deposition (green arrows). Angiogenesis (black arrow).

-G5 (Chitosan treatment)

Almost all histopathological figures of the skin revealed a normal epidermis keratinized stratified squamous epithelium which little mitotic figures. The dermis comprised mature fibrous tissue characterized by marked angiogenesis (numerous blood capillaries) and no infiltration of leukocytes. Other figures revealed well−keratinized stratified epithelial cells of the epidermis as shown in Figure 8C,D.

-G6 (Chitosan and Lavandula Treatment)

Histopathological examination of the skin sections revealed a normal epidermis with a keratinized stratified squamous epithelium showing complete epithelialization. The dermis comprised mature fibrous connective tissue with abundant collagen bundles and numerous blood capillaries, indicating marked angiogenesis. Sweat glands and sebaceous glands appeared normal. There was no significant infiltration of inflammatory cells. The overall tissue architecture appeared well−organized, suggesting effective healing response post−treatment as shown in Figure 8E,F.

3.2. Wound Contraction

Wound contraction percentage on day 3, day 7, and day 14 of therapy was significantly higher in the chitosan and Lavandula group in comparison to other groups, p < 0.001. Wound contraction % on day 14 of therapy was significantly increased from that on day 3 and day 7 of therapy among all study groups, p < 0. 001.as shown in Table 5 and Figure 9.

Table 5.

Comparison between induced groups (induced non−treated group, Fucidin group, Lavandula group, chitosan group, and chitosan and Lavandula group) in relation to wound contraction % across different days of therapy.

Figure 9.

Wound contraction percentage for groups (2 to 6) on day 3, day 7, and day 14 of therapy. G1, induced non−treated group; G2, Fucidin group; G3, Lavandula group; G4, chitosan group; and G5, chitosan and Lavandula group.

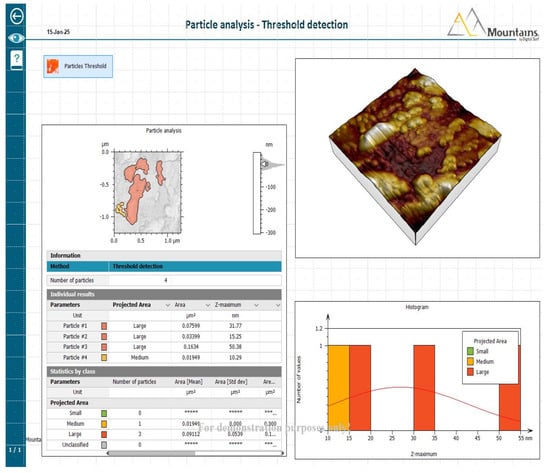

Atomic Force Microscopy

The morphological characteristics and particle size distribution of the prepared nanoparticles were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM), as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Particle analysis—threshold detection.

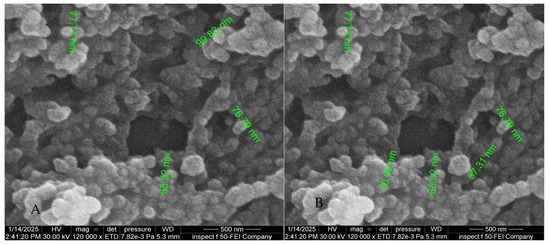

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of Chitosan nanoparticles showing spherical morphology with particle sizes below 100 nanometer, shown in Figure 11A,B.

Figure 11.

(A,B) Scanning electron microscope.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy of Chitosan nanoparticles (Figure 12), Lavender oil (Figure 13) and Chitosan-Lavender nanoemulsion (Figure 14).

Figure 12.

Chitosan nanoparticle FTIR.

Figure 13.

Lavender oil FTIR.

Figure 14.

Chitosan–lavender nanoemulsion FITR.

4. Discussion

The wound healing process includes complex interactions between many cell types, cytokines, mediators, and the vascular system. The sequence of initial vasoconstriction of blood vessels and platelet aggregation aims to stop hemorrhaging. This is succeeded by an influx of different inflammatory cells, beginning with the neutrophil. These inflammatory cells subsequently secrete various mediators and cytokines to facilitate angiogenesis, thrombosis, and re−epithelialization. The fibroblasts subsequently release extracellular components. Wound healing is a natural physiological response to tissue damage [34]. Wound infections resulting from the colonization of bacteria and other microorganisms at the wound site present a significant challenge to wound treatment, as they induce severe inflammatory reactions that impede healing and may lead to wound deterioration [35,36,37].

The current study investigates various wound healing processes across multiple groups, including those with untreated wounds compared to induced treatment groups. These treatment groups consist of a Lavandula group, a chitosan group, and a combination of both Lavandula and chitosan, all compared to a positive control group treated with Fucidin.

The current study compared a hematological biomarker (WBC count on day 7 and day 14) and ELISA biomarkers on day 14 (TNF−α, IL−6, MDA, and SOD) between an apparently healthy control group and an induced non−treated group. The significant elevation in WBC count observed on days 7 and 14 indicates a persistent immune response during the inflammatory phase of wound healing. This response is further supported by the marked increase in the pro−inflammatory cytokines TNF−α and IL−6 and the oxidative stress marker MDA on day 14. These biomarkers are critical indicators of the inflammatory and oxidative status of the wound environment and suggest that the healing process is still in an active or prolonged inflammatory phase. This can influence tissue remodeling and may delay progression to the proliferative and maturation phases of healing.

These findings align with recent studies indicating that as a result of skin injury, various chemoattractant chemicals are released into circulation, prompting the migration and recruitment of neutrophils initially and macrophages later. Recruited leukocytes phagocytize necrotic tissues and secrete cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor−α (TNF−α), interleukin (IL)−1β, and IL−6, as well as growth factors, which mediate and promote healing [38,39]. Interleukin (IL)−6 is essential for the prompt resolution of wound healing and plays a key role in acute inflammation. IL−6, which is released early in response to damage, causes tissue−resident macrophages, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, and stromal cells to release pro−inflammatory cytokines. Leukocyte chemotaxis into a wound has also been observed in response to IL−6. IL−6 signaling is responsible for the switch to a reparative environment. Controlling the healing process of wounds is essential. Inappropriate pro−inflammatory signaling can lead to wounds that are more prone to infection and take quite longer to heal [40].

TNF−α, a type of tumor necrosis factor, is crucial in the inflammatory phase of wound healing. TNF−α not only activates the immune response but also attracts immune cells to the site of injury. Furthermore, TNF−α stimulates the proliferation of fibroblasts and angiogenesis, the differentiation of keratinocytes, and the production of growth factors [41].

Oxidative stress is an internal imbalance between the body’s pro−oxidants and antioxidants. During oxidative stress, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) increases, which is crucial for wound healing [42]. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) functions as an antioxidant enzyme that reduces oxygen radicals via oxidation/reduction cycles at an exceptionally rapid response rate [43].

4.1. Rationale for Using Chitosan−Based Nanoparticles in Wound Healing

Chitosan−based nanoparticles (CSNPs) have emerged as a novel approach in wound healing due to their capacity to accurately deliver therapeutic agents for enhanced tissue repair. The sustained release of encapsulated pharmaceuticals, growth hormones, or antibacterial agents is facilitated by their small size, allowing for effective infiltration and retention at the wound’s location. The targeted delivery reduces systemic side effects and sustains optimal local therapeutic concentrations, which is essential for effective healing [44].

The biocompatibility of chitosan arises from its natural origin, non−toxic breakdown products, and capacity to facilitate cellular functions without triggering negative immunological responses. It stimulates fibroblast proliferation, facilitates collagen production, and accelerates tissue regeneration by mimicking extracellular matrix components, making it optimal for wound healing. Its cationic properties enhance interactions with negatively charged cell membranes and extracellular components, boosting adhesion and migration while preserving a non−immunogenic character [45].

4.2. Anti−Inflammatory Effects of Different Treatment Groups

The chitosan group and the chitosan and Lavandula combination group demonstrated a significant reduction in WBC counts on days 7 and 14, along with decreased TNF−α and IL−6 levels on day 14 compared with other treated groups (p < 0.05). This indicates an accelerated resolution of infection−induced inflammation due to their nanoparticles’ properties.

Chitosan regulates the inflammatory phase of wound healing by reducing pro−inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin−6 (IL−6) and tumor necrosis factor−alpha (TNF−α). It promotes the resolution of inflammation by stimulating macrophage polarization towards the anti−inflammatory M2 phenotype [46].

Chitosan is widely used for its anti−inflammatory properties, primarily through the inhibition of NF−κB activation. In cell−based studies, it has been shown to suppress inflammation triggered by LPS by downregulating NF−κB and decreasing the production of pro−inflammatory cytokines in several cell types, such as Caco−2 cells, endothelial cells, and RAW 264.7 macrophages [47].

Lavandula angustifolia decreased the expression of inflammatory mediators, including IL−6 and TNF−α; the anti−inflammatory properties of lavender are attributed to its essential oil constituents, non−volatile terpenoids, and polyphenols [48].

Linalool and linalyl acetate components exhibit anti−inflammatory properties by diminishing the phosphorylation of the p65 and p50 NFκB transcription factors, reducing the synthesis of pro−inflammatory cytokines IL−6 and TNFα. α−terpineol reduces the synthesis of the pro−inflammatory cytokine IL−6 [49].

Lavender oil exhibited a potent inhibitory effect on ROS production and demonstrated strong anti−inflammatory potential. This effect was mediated through modulation of the NF−κB signaling cascade, a central regulator of the inflammatory response. Activation of NF−κB by stimuli like LPS, cytokines, or oxidants leads to the phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and proteasomal degradation of its inhibitor, IκB. This process exposes the nuclear localization signal of NF−κB, promoting its translocation into the nucleus and subsequent transcription of pro−inflammatory genes, including those encoding iNOS, COX−2, TNF−α, IL−6, and IL−1 Given its pivotal role in inflammation, NF−κB inhibition is considered a major therapeutic target in the development of new anti−inflammatory drugs [50].

Lavandula angustifolia extract has low chemical stability, poor water solubility, and a volatile nature, leading to poor lasting effects. This led us to combine lavender essential oil with chitosan in an emulsion form [51]. This explains why it was less effective than other treatment groups when used alone.

Together, the synergistic effect of the chitosan and Lavandula combination group likely explains the pronounced decline in systemic and local inflammatory markers among other groups observed in this study. Fucidin has demonstrated anti−inflammatory properties, particularly by diminishing the secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF−α and IL−6). It has an inhibitory effect associated with the inhibition of 12−O−tetradecanoyl phorbol−13−acetate (TPA)−induced upregulation of the pro−inflammatory cytokines IL−1β, TNF−α, and COX−2 [52].

Members of this group show less anti−inflammatory action than nanoparticle treatment groups and more anti−inflammatory action than the Lavandula angustifolia extract group.

4.3. Modulation of Oxidative Stress

On day 14, MDA levels were significantly reduced, whereas SOD activity was markedly increased in the chitosan and Lavandula group (p < 0.001). This suggests improved redox balance and enhanced antioxidant defense.

Chitosan demonstrates redox−regulatory functions by inhibiting reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, preventing lipid oxidation by significantly reducing serum free fatty acids and malondialdehyde levels, and enhancing intracellular antioxidant enzyme activity in biological systems. Chitosan exhibits an effective capacity for metal ion chelation, indicating its promise as a natural antioxidant [53].

The transcription factor NRF2 is a central regulator of the cellular stress response orchestrating the expression of multiple ROS−detoxifying enzymes, antioxidant proteins, and drug transporters. Given its pivotal role in protecting cells against ROS during inflammatory processes, NRF2 expression increases following tissue injury in association with enhanced ROS production. Nevertheless, during the progression of wound repair, NRF2 expression declines in response to treatment with chitosan [47].

The antioxidant effectiveness of polyphenols in Lavandula angustifolia comes from their capacity to inhibit the formation of free radicals and neutralize reactive oxygen species. They can give a hydrogen atom or an electron, exhibiting reducing properties [54]. These chemicals can inhibit oxidation processes by activating antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase, glutathione dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase, and also through their chelating activity with metal ions [55,56].

The combination of chitosan and Lavandula agents likely exerts an additive antioxidant effect, contributing to accelerated tissue repair.

The chitosan and Fucidin groups showed a greater antioxidant effect than the Lavandula angustifolia group due to the nanoparticle size of the chitosan group, stronger antioxidant properties, and better stability, with longer−lasting effects of the Fucidin and chitosan groups.

4.4. Antimicrobial Synergy Against Staphylococcus aureus

The lowest WBC level was observed in the chitosan and Lavandula combination group, with a significant difference from the other groups (p < 0.001). The enhanced outcomes in the chitosan and Lavandula combination group are also attributed to dual antimicrobial activity.

The main chemical ingredients of L. angustifolia essential oil, including linalool, linalyl acetate, and terpinen−4−ol, suggest that their method of action mostly involves disrupting the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane, leading to bacterial cell leakage [57,58,59].

The protonated amine groups (NH3+) of chitosan interact with negatively charged microbial components, including lipopolysaccharides in Gram−negative bacteria, peptidoglycan in Gram−positive bacteria, and the polar head groups of phospholipids. This interaction disrupts membrane integrity, increasing permeability and leading to the leakage of intracellular constituents, ultimately resulting in cell death. Beyond membrane disruption, chitosan also exerts antimicrobial effects by chelating essential metal ions, impairing protein synthesis, and interfering with nutrient transport, thereby exhibiting broad−spectrum activity against both bacteria and fungi [60].

Chitosan and its derivatives, such as chitosan nanocrystals, exhibit unique surface functionality arising from their positive surface charge, rod−like morphology, and nanoscale dimensions. These physicochemical properties enable strong electrostatic interactions with negatively charged bacterial cell membranes, ultimately leading to membrane disruption and cell death [60].

Fucidin group members also showed a significant reduction in WBC count (p < 0.001) in comparison with the induced non−treated group. It blocks bacterial protein synthesis by binding to elongation factor G (EF−G) on ribosomes, preventing the elongation of nascent polypeptides [61].

The enhanced outcomes observed in the chitosan and Lavandula group can be attributed to a multifaceted mechanism involving reduced bacterial load, downregulation of pro−inflammatory cytokines, and strengthened antioxidant defenses. These synergistic actions account for the decreases in WBC, TNF−α/IL−6, and MDA levels, alongside the elevation in SOD activity, underscoring the therapeutic promise of integrating natural extracts with biomaterials to optimize infected wound healing.

4.5. Histopathological Findings

Histopathological analysis revealed comprehensive evidence of tissue−level healing among the groups. Histological evaluation clearly revealed the gradual variations in tissue repair among the groups. In the untreated wounds, persistent epidermal loss, necrotic dermal tissue, vascular congestion, and significant leukocyte infiltration indicated prolonged inflammation and delayed advancement to subsequent healing stages. These pathological characteristics align with chronic wound conditions in which ongoing infection and oxidative stress hinder fibroblast migration and collagen production [14].

Treatment with Fucidin facilitated partial healing, as seen by re−epithelialization, immature dermal tissue, and angiogenesis; nevertheless, residual inflammation persisted, signifying an incomplete progression to tissue remodeling [62]. Similarly, the use of Lavandula angustifolia extract enhanced epithelial and vascular responses, but the presence of immature collagen bundles and minor inflammatory infiltrates indicated only a slight improvement in healing. This is in agreement with previous research indicating that Lavandula extracts decrease inflammatory cytokine expression and enhance fibroblast activity, although they may be inadequate as a standalone treatment for complex infected wounds [63].

In contrast, chitosan therapy resulted in significant enhancements, including the restoration of keratinized epithelium, organized dermal fibrous tissue, and heightened capillary density, suggestive of enhanced proliferative activity and decreased inflammation. Chitosan is recognized for its ability to induce macrophage polarization, fibroblast proliferation, and collagen deposition, thus expediting the proliferative process to the remodeling phase transition [14,64].

The most remarkable result was noted in the combination of chitosan and Lavandula, which resulted in complete tissue restoration—normal epidermis, mature dermal connective tissue abundant in collagen, extensive neovascularization, and fully intact cutaneous tissues free of inflammatory infiltrates. These data validate that the combination not only improves structural recovery but also restores tissue integrity, a hallmark of real tissue regeneration rather than simple repair. Recent findings have established that the synergistic effect of chitosan scaffolds infused with essential oils greatly accelerated granulation, collagen remodeling, and re−epithelialization compared to the use of each agent independently [15].

Lavender oil causes upregulation of TGF−β, which provides a plausible explanation for the enhanced fibroblast proliferation, which contributes to collagen synthesis and elevated collagen mRNA expression. TGF−β and collagen are known to be co−expressed in a coordinated manner to facilitate granulation tissue formation during wound repair. Furthermore, TGF−β has been reported to stimulate fibroblasts to secrete matrix metalloproteinase−13 (MMP−13), also referred to as collagenase−3. MMP−13 plays a critical role in the degradation of type III collagen, thereby allowing its replacement by type I collagen, an essential step in tissue remodeling throughout the wound healing process. Topical application of lavender oil enhanced the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts within wound granulation tissue during the early phase of healing. This effect can be attributed to the upregulation of TGF−β, as TGF−β has been shown to promote fibroblast−to−myofibroblast differentiation, a process critical for wound contraction and tissue shrinkage during repair [65].

The elevated collagen levels observed in the treated groups indicate that the formulations enhance the healing process, as the rise in collagen content correlates with tissue maturation, a reduction in total cellularity (indicative of diminished inflammation), and the formation of blood vessels [66].

Together, these histological results highlight the enhanced regenerating capacity of the chitosan–Lavandula formulation, which combines the structural scaffold characteristics of chitosan with the anti−inflammatory and antioxidant properties of lavender. This dual action targets both the microbial/inflammatory load and the necessity for strong matrix formation, therefore facilitating systematic and comprehensive wound healing.

4.6. Wound Contraction Percentage %

Wound contraction is essential for the closure of full−thickness wounds, as the surrounding skin is drawn into the defect by forces produced within the granulation tissue. The myofibroblast, a distinct fibroblast type marked by cytoplasmic stress fibers abundant in α smooth muscle actin (SMA), is recognized as the cell phenotype accountable for wound contraction. The organization of the freshly generated connective tissue matrix into denser collagen fiber bundles generates tension, which facilitates the conversion of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. TGFβ1 biochemically facilitates the conversion of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts in monolayer culture. Promoting the myofibroblast phenotype will help to enhance wound contraction; conversely, obstructing the emergence of myofibroblasts is expected to impede or inhibit wound contraction [67].

Wound contraction percentages on days 3, 7, and 14 were significantly higher in the chitosan and Lavandula group compared to the other groups (p < 0.001), with day 14 showing the greatest contraction across all groups.

Chitosan offers a biocompatible scaffold that facilitates tissue regeneration, while volatile oils give antibacterial and anti−inflammatory advantages, resulting in a multifunctional strategy for wound management. The incorporation of Lavandula into a chitosan matrix could improve the antibacterial and anti−inflammatory properties of the mixture, demonstrating efficacy in facilitating wound healing and tissue regeneration [68].

Together, the results demonstrate a progressive improvement from untreated wounds to single−agent therapies (Fucidin, Lavandula, chitosan), with the chitosan and Lavandula combination yielding superior systemic, biochemical, histological, and functional effects. This combined therapy accelerates the resolution of inflammation, increases antioxidant activity, and stimulates collagen deposition, angiogenesis, re−epithelialization, and wound contraction through ordered tissue regeneration and efficient wound closure. The synergistic interaction of chitosan and Lavandula is a promising approach for the management of infected wounds, combining structural support, antibacterial properties, anti−inflammatory effects, and antioxidant capabilities.

5. Conclusions

The integration of chitosan nanoparticle−loaded hydrogel with Lavandula angustifolia extract demonstrates a potent synergistic effect in enhancing wound healing in S. aureus−infected wounds. By improving hematological and biochemical profiles, promoting favorable histopathological changes, and accelerating wound contraction, this combination therapy shows potential benefits for managing infected wounds. Future studies should focus on mechanistic insights and clinical translation to validate its efficacy in humans.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.F.M.Z. and M.Q.Y.M.A.A.A.; methodology, F.F.M.Z. and M.Q.Y.M.A.A.A.; software, F.F.M.Z.; validation, M.Q.Y.M.A.A.A. and F.F.M.Z.; investigation, F.F.M.Z.; resources, F.F.M.Z.; data curation, F.F.M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, F.F.M.Z.; writing—review and editing, F.F.M.Z.; visualization, M.Q.Y.M.A.A.A.; supervision, M.Q.Y.M.A.A.A.; project administration, M.Q.Y.M.A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted from October 2024 to August 2025. All of the experimental work was implemented following the protocol reviewed by the Iraqi Board Review of the College of Medicine/Baghdad University after being approved by the scientific committee of the Department of Pharmacology at the College of Medicine/Baghdad University. Number 35 on 6 October 2024.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the researchers upon reasonable request. The majority of the data were utilized in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Great and deep thanks to Faraedon M. Zardawi for his endless assistance, advice, and encouragement during this research. Special thanks to Labeeb Ahmed Kadhim Al−zubaidi and Suha Mohammed Ibrahim, Ministry of Science and Technology, for their assistance with extraction and nanomaterial preparation. Special thanks to Adnan Khazaal Ajeel, Iraqi Center for Cancer and Medical Genetic Research, University of Mustansiriyah, for his assistance during this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| MRSA | Methicillin−resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| GlcN | Nacetyl−2−amino−2−deoxy−D−glucose glucosamine |

| Cs NPs | Chitosan nanoparticles |

| WBC | White Blood Cell |

| TNF−α | Tumor necrosis factor−alpha |

| IL−6 | Interleukin−6 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| ecSOD | Extracellular super−oxide Dismutase |

| UV−Vis spectroscopy | Ultraviolet−Visible Spectroscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDX | Energy Dispersive X−Ray Spectroscopy |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| XRD | X−ray diffraction |

| TLR4 | Toll−Like Receptor 4 |

| NF−κB | Nuclear Factor kappa−light−chain−enhancer of activated B cell |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

References

- Maillard, J.-Y.; Kampf, G.; Cooper, R. Antimicrobial stewardship of antiseptics that are pertinent to wounds: The need for a united approach. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, M.; Sahin, K.B.; West, Z.E.; Murray, R.Z. Macrophage Phenotypes Regulate Scar Formation and Chronic Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Kosaric, N.; Bonham, C.A.; Gurtner, G.C. Wound Healing: A Cellular Perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 665–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarheed, O.; Ahmed, A.; Shouqair, D.; Boateng, J. Antimicrobial dressings for improving wound healing. In Wound Healing—New Insights into Ancient Challenges; Alexandrescu, V., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2016; pp. 373–398. ISBN 978-953-51-2679-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, A.F.; Wilson, S.E. Skin and soft−tissue infections: A critical review and the role of telavancin in their treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, S69–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, G.; Raphael, J.; Leavitt, S.D.; St Clair, L.L. In vitro evaluation of the antibacterial activity of ex−tracts from 34 species of North American lichens. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 1262–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L. Nanoparticle−based local antimicrobial drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 127, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdan, S.; Pastar, I.; Drakulich, S.; Dikici, E.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Deo, S.; Daunert, S. Nanotechnology−Driven Therapeutic Interventions in Wound Healing: Potential Uses and Applications. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghormade, V.; Pathan, E.K.; Deshpande, M.V. Can fungi compete with marine sources for chitosan production? Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranaz, I.; Alcántara, A.R.; Civera, M.C.; Arias, C.; Elorza, B.; Caballero, A.H.; Acosta, N. Chitosan: An Overview of Its Properties and Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, V.R.; Grekov, D.F.; Kisyov, V.K.; Ivanov, K.I. Potential of lavender (Lavandula vera L.) for phytoremediation of soils contaminated with heavy metals. Int. J. Agric. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 9, 522–529. [Google Scholar]

- Dobros, N.; Zawada, K.D.; Paradowska, K. Phytochemical profiling, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of plants belonging to the Lavandula genus. Molecules 2022, 28, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tăbăraşu, A.-M.; Anghelache, D.-N.; Găgeanu, I.; Biris, S.-S.; Vlădut, N.-V. Considerations on the Use of Active Compounds Obtained from Lavender. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektas, N.; Şenel, B.; Yenilmez, E.; Özatik, O.; Arslan, R. Evaluation of wound healing effect of chitosan−based gel formulation containing vitexin. Saudi Pharm. J. 2020, 28, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osanloo, M.; Noori, F.; Varaa, N.; Tavassoli, A.; Goodarzi, A.; Moghaddam, M.T.; Ebrahimi, L.; Abpeikar, Z.; Farmani, A.R.; Safaei, M.; et al. The wound healing effect of polycaprolactone−chitosan scaffold coated with a gel containing Zataria multiflora Boiss. volatile oil nanoemulsions. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kırkıncı, S.; Gercek, Y.C.; Baştürk, F.N.; Yıldırım, N.; Gıdık, B.; Bayram, N.E. Evaluation of lavender essential oils and byproducts using microwave hydrodistillation and conventional hydrodistillation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghaffar, M.A.A.; Hashem, M.S. Chitosan and its amino acids condensation adducts as reactive natural polymer supports for cellulase immobilization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 81, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghaffar, M.A.; Hashem, M.S. Immobilization of α−amylase onto chitosan and its amino acid condensation adducts. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 112, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.N.; Samling, B.A.; Tong, W.Y.; Chear, N.J.; Yusof, S.R.; Lim, J.W.; Tchamgoue, J.; Leong, C.R.; Ramanathan, S. Chitosan−Based Nanoencapsulated Essential Oils: Potential Leads against Breast Cancer Cells in Preclinical Studies. Polymers 2024, 16, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Agarwal, M.K.; Shrivastav, N.; Pandey, S.; Das, R.; Gaur, P. Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles and their In-vitro Characterization. Int. J. Life-Sci. Sci. Res. 2018, 4, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.-W.; Chun, S.C.; Chandrasekaran, M. Preparation and in vitro characterization of chitosan nanoparticles and their broad−spectrum antifungal action compared to antibacterial activities against phytopathogens of tomato. Agronomy 2019, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, E.; Chiweshe, T.T.; Roberts, H. Modification of Novel Chitosan−Starch Cross−Linked Derivatives Polymers: Synthesis and Characterization. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijevic, R.; Cvetkovic, O.; Miodragovic, Z.; Simic, M.; Manojlovic, D.; Jovic, V. SEM/EDX and XRD characterization of silver nanocrystalline thin film prepared from organometallic solution precursor. J. Min. Met. Sect. B Metall. 2013, 49, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodoroaba, V.D. Energy−dispersive X−ray spectroscopy (EDS). In Characterization of Nanoparticles: Measurement Processes for Nanoparticles; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 439–464. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.L.; Xu, Z.R.; Han, X.Y.; Xu, Y.L.; Miao, Z.G. Preparation, characterization and adsorption properties of chitosan nanoparticles for eosin Y as a model anionic dye. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 153, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojha, S.; Sett, A.; Bora, U. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Ricinus communis var. carmencita leaf extract and its antibacterial study. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 035009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.T.; Mohamed, B.S.; Zayed, M.; El-Sabbagh, S.M. Antibacterial, antibiofilm, and anticancer activity of silver-nanoparticles synthesized from the cell-filtrate of Streptomyces enissocaesilis. BMC Biotechnol. 2024, 24, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.C.; Plapler, H.; Costa, M.M.; Silva, S.R.; Sá, M.d.C.; Silva, B.S. Low level laser therapy (AlGaInP) applied at 5 J/cm2 reduces the proliferation of Staphylococcus aureus MRSA in infected wounds and intact skin of rats. Bras. Dermatol. 2013, 88, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeh, N.; Namavar, M.R. Optimisation of ketamine-xylazine anaesthetic dose and its association with changes in the dendritic spine of CA1 hippocampus in the young and old male and female Wistar rats. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinko, B.C.; Precious-Abraham, A.D. Wound healing activity of hydromethanolic Dioscorea bulbifera extract on male wistar rat excision wound models. Pharmacol. Res.-Mod. Chin. Med. 2024, 11, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, K.S.; Layton, C.; Bancroft, J.D. Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques, 8th ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2019; p. 672. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Kumar, P. Assessment of the histological state of the healing wound. Plast. Aesthet. Res. 2015, 2, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgok Kangal, M.K.; Regan, J.P. StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cefalu, J.E.; Barrier, K.M.; Davis, A.H. Wound infections in critical care. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 29, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; Han, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yeung, K.; Li, C.; Cui, Z.; Liang, Y. Rapid bacteria trapping and killing of metal−organic frameworks strengthened photo−responsive hydrogel for rapid tissue repair of bacterial infected wounds. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 396, 125194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negut, I.; Grumezescu, V.; Grumezescu, A.M. Treatment strategies for infected wounds. Molecules 2018, 23, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejada, S.; Batle, J.M.; Ferrer, M.D.; Busquets-Cortés, C.; Monserrat-Mesquida, M.; Nabavi, S.M.; Del Mar Bibiloni, M.; Pons, A.; Sureda, A. Therapeutic Effects of Hyperbaric Oxygen in the Process of Wound Healing. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 1682–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landén, N.X.; Li, D.; Ståhle, M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: A critical step during wound healing. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3861–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.Z.; Stevenson, A.W.; Prêle, C.M.; Fear, M.W.; Wood, F.M. The Role of IL−6 in Skin Fibrosis and Cutaneous Wound Healing. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, K. The Role of TNF−Alpha in the Wound Healing Process: Molecular and Clinical Perspectives−A Systematic Literature Review. J. RSMH Palembang. 2022, 3, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnill, C.; Patton, T.; Brennan, J.; Barrett, J.; Dryden, M.; Cooke, J.; Leaper, D.; Georgopoulos, N.T. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and wound healing: The functional role of ROS and emerging ROS−modulating technologies for augmentation of the healing process. Int. Wound. J. 2017, 14, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Z.; Xu, W.; Chen, Q. The Applications and Mechanisms of Su−peroxide Dismutase in Medicine, Food, and Cosmetics. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskar, A.; Kim, K.S. Recent Advances in Nanomaterial-Based Wound-Healing Therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korniienko, V.; Husak, Y.; Diedkova, K.; Varava, Y.; Grebnevs, V.; Pogorielova, O.; Bērtiņš, M.; Korniienko, V.; Zandersone, B.; Ramanaviciene, A.; et al. Antibacterial Potential and Biocompatibility of Chitosan/Polycaprolactone Nanofibrous Membranes Incorporated with Silver Nanoparticles. Polymers 2024, 16, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, D.; Hoemann, C.D. Chitosan Immunomodulatory Properties: Perspectives on the Impact of Structural Properties and Dosage. Futur. Sci. OA 2017, 4, FSO225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherng, J.-H.; Lin, C.-A.J.; Liu, C.-C.; Yeh, J.-Z.; Fan, G.-Y.; Tsai, H.-D.; Chung, C.-F.; Hsu, S.-D. Hemostasis and Anti−Inflammatory Abilities of AuNPs−Coated Chitosan Dressing for Burn Wounds. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouri, V.; Tebbi, S.O.; Caseiro, A.; Trapali, M. Lamiaceae Family Plants as Natural Solutions for Inflammation and Blood Sugar Management. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2024, 20, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandur, E.; Balatinácz, A.; Micalizzi, G.; Mondello, L.; Horváth, A.; Sipos, K.; Horváth, G. Anti−inflammatory effect of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) essential oil prepared during different plant phenophases on THP−1 macrophages. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuzarte, M.; Francisco, V.; Neves, B.; Liberal, J.; Cavaleiro, C.; Canhoto, J.; Salgueiro, L.; Cruz, M.T. Lavandula viridis L´Hér. Essential Oil Inhibits the Inflammatory Response in Macrophages Through Blockade of NF−KB Signaling Cascade. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 695911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danila, A.; Muresan, E.I.; Ibanescu, S.-A.; Popescu, A.; Danu, M.; Zaharia, C.; Türkoğlu, G.C.; Erkan, G.; Staras, A.-I. Preparation, characterization, and application of polysaccharide−based emulsions incorporated with lavender essential oil for skin−friendly cellulosic support. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 191, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-P.; He, H.; Hong, W.D.; Wu, T.-R.; Huang, G.-Y.; Zhong, Y.-Y.; Tu, B.-R.; Gao, M.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, S.-Q.; et al. The biological evaluation of fusidic acid and its hydrogenation derivative as antimicrobial and anti−inflammatory agents. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 1945–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, D.G.; Yaneva, Z.L. Antioxidant Properties and Redox−Modulating Activity of Chitosan and Its Derivatives: Biomaterials with Application in Cancer Therapy. BioRes. Open Access 2020, 9, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boligon, A.A.; Machado, M.M.; Athayde, M.L. Technical evaluation of antioxidant activity. Med. Chem. 2014, 4, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima Cherubim, D.J.; Buzanello Martins, C.V.; Oliveira Fariña, L.; da Silva de Lucca, R.A. Polyphenols as natural antioxidants in cosmetics applications. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, C.F.; Mee, B.J.; Riley, T.V. Mechanism of Action of Melaleuca alternifolia (Tea Tree) Oil on Staphylococcus aureus Determined by Time−Kill, Lysis, Leakage, and Salt Tolerance Assays and Electron Microscopy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 1914–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombetta, D.; Castelli, F.; Sarpietro, M.G.; Venuti, V.; Cristani, M.; Daniele, C.; Saija, A.; Mazzanti, G.; Bisignano, G. Mechanisms of Antibacterial Action of Three Monoterpenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2474–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galgano, M.; Capozza, P.; Pellegrini, F.; Cordisco, M.; Sposato, A.; Sblano, S.; Camero, M.; Lanave, G.; Fracchiolla, G.; Corrente, M.; et al. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils evaluated in vitro against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez, R.; Aguado, R.J.; Barrios, N.; Arellano, H.; Tolosa, L.; Delgado-Aguilar, M. Advanced antimicrobial surfaces in cellulose−based food packaging. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2025, 341, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseef, H.; Sahoury, Y.; Farraj, M.; Qurt, M.; Abukhalil, A.D.; Jaradat, N.; Sabri, I.; Rabba, A.K.; Sbeih, M. Novel Fusidic Acid Cream Containing Metal Ions and Natural Products against Multidrug−Resistant Bacteria. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurel, M.S.; Naycı, S.; Turgut, A.V.; Bozkurt, E.R. Comparison of the effects of topical fusidic acid and ri−famycin on wound healing in rats. Int. Wound J. 2015, 12, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, A.K.; Çeçen, D.; Gürgen, S.G.; Sayın, O.; Çetin, F. A Comparison Study of Growth Factor Expression following Treatment with Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation, Saline Solution, Povidone-Iodine, and Lavender Oil in Wounds Healing. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 361832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Al Balah, O.F.A.; Refat, M.; Badr, A.M.; Afifi, A. Low−level laser and chitosan nanoparticles therapy speeds up the process of skin wound healing in mice: Histological, hematological, and proinflammatory cytokines assessment. J. Basic. Appl. Zool. 2025, 86, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.-M.; Kawanami, H.; Kawahata, H.; Aoki, M. Wound healing potential of lavender oil by acceleration of granulation and wound contraction through induction of TGF−β in a rat model. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oryan, A.D.; Mohammadalipour, A.D.; Moshiri, A.D.; Tabandeh, M.R.D. Topical Application of Aloe vera Accelerated Wound Healing, Modeling, and Remodeling. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016, 77, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, K.; Ehrlich, H.P. When the Smad signaling pathway is impaired, fibroblasts advance open wound con−traction. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2010, 89, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabil, Y.; Atta, A.H.; El-Fattah, W.A.; Hafez, H.S.; Elshaarawy, R.F. Progress in chitosan/essential oil/ZnO nanobiocomposites fabrication for wound healing applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318, 145123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).