Abstract

Given the ubiquity of anti-fat prejudice, in this experimental study, we tested whether weight gain attributed to COVID-19 would influence evaluations of overweight male and female targets. Female participants (N = 160) were randomly assigned to read one of four mock medical forms that outlined distractor medical information (e.g., blood requisition results), the sex of the target (male vs. female) and stated reason for weight gain (unhealthy lifestyle choices vs. inactivity due to the COVID-19 lockdown). Participants evaluated the patient on a series of binary adjectives (e.g., lazy/industrious), and completed measures assessing anti-fat attitudes (i.e., fear of becoming fat and belief in the controllability of weight), internalization of ideal standards of appearance, and BMI (i.e., self-reported weight and height). Contrary to our predictions, we found that overweight male and female patients were evaluated similarly regardless of whether their weight gain was attributable to unhealthy lifestyle choices or inactivity due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, believing that one’s weight is controllable and internalizing general standards of attractiveness correlated positively with fat disparagement of the medical patients. Participants’ BMI and fear of fat, however, were negligibly related to fat disparagement. Possible explanations for our findings, implications for healthcare settings, and directions for future research are explored.

1. Introduction

In North America, general attitudes towards individuals deemed to be “overweight” or “fat” are markedly negative [,]. Moreover, the greater a person’s body weight (i.e., the closer their proximity to clinical obesity), the greater the probability that they will experience discrimination compared to those of lesser weight []. Social scientists have used the term “anti-fat attitudes” to describe negative beliefs about and perceptions of individuals whose body type is classified as overweight or obese [,].

Social psychologists posit that cultures whose beauty standards reflect unrealistic body ideals (e.g., leanness, muscularity) and who deem body fat to be unattractive tend to exhibit greater anti-fat attitudes than cultures that do not embrace these aesthetic ideals []. For instance, North American culture has strict appearance ideals for both men and women []. The corporeal ideal for women is generally conveyed by popular models and social media influencers, and may be characterized by leanness and, in some cases, fat distribution in specific regions of the body such as the breasts and buttocks [,,]. For men, athletes and social media influencers convey ideals such as muscularity and an absence of body fat [,].

Group membership on the dimension of body weight (overweight vs. average/low weight) also has been linked with anti-fat attitudes; however, the findings are mixed. For example, Schwartz and colleagues [], in their well-cited study, found an inverse association between participants’ body mass index (BMI) and their endorsement of anti-fat attitudes (i.e., as BMI increased, anti-fat attitudes decreased). However, Seibert and colleagues [] reported that overweight individuals often devalue others who are overweight and at the same level as non-overweight individuals. In their experimental study, Seibert et al. [] also demonstrated that individuals associating with a non-overweight group demonstrated more pronounced anti-fat bias, while those associating with an overweight group showed diminished anti-fat bias. Further highlighting the mixed nature of findings, Standen and colleagues [] report locating only one study that clearly showed in-group favouritism in terms of both the predicted negative correlation and absolute levels of explicit weight bias (p. 4).

Gender differences in endorsement of anti-fat attitudes also have been noted, with studies demonstrating repeatedly that men hold greater anti-fat attitudes towards overweight and obese individuals [,,,,]. Additionally, researchers have found that overweight female targets are evaluated more negatively than their overweight male counterparts [,,]. It is unsurprising, then, that women, in comparison to men, have a greater fear of gaining weight [], possibly due to the heightened stigma experienced by overweight women.

1.1. Attribution Theory

In addition to body weight and gender, researchers have documented that the perceived aetiology of an individual’s weight also plays a role in anti-fat attitudes. Attribution theory, for example, posits that people make different judgements about others’ behaviour when they are privy to the cause of the observed behaviour []. According to this theory, the causes of a given behaviour can be apprised on two dimensions: (1) the behaviour is based on situational or individual factors (i.e., external or internal causes, respectively) and (2) the behaviour is seen as controllable or uncontrollable.

Previous research has used attribution theory to account for anti-fat bias [,,]. Researchers have observed that overweight targets are evaluated more negatively if participants receive information stating that a target’s weight gain could be attributed to an internal and controllable cause such as consumption of unhealthy food, lack of willpower, or minimal physical activity [,,]. In contrast, overweight targets were evaluated more positively when weight gain was attributed to uncontrollable factors such as having a metabolic disorder [].

Based on these findings, one would anticipate that individuals gaining weight because of an external factor, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, may be accorded more latitude (and, thus, less fat disparagement) than individuals who gain weight because of internal factors such as unhealthy lifestyle choices. It should be noted, however, that when it comes to weight gain, a strong role is still assigned to personal responsibility. Thus, while an “obesogenic environment” or event, such as COVID-19, may make it more difficult for people to manage their weight, it does not absolve them of their “responsibility” to do so [] (p. 49).

1.2. COVID-19 and Weight

Most of the research on anti-fat attitudes and prejudice towards overweight individuals was conducted outside the constraints of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Since the pandemic began in December 2019, nearly 800 million cases with 7 million deaths [] have occurred. The coronavirus pandemic forced individuals to make substantial changes to their daily routines and behaviour to adapt to lockdowns and other restrictions []. For instance, food takeout and alcohol sales increased significantly during and after lockdown, suggesting that people may have used these forms of consumption to deal with feelings of distress caused by the pandemic []. People also reported increasing their caloric intake through meals, snacks, and beverages, decreasing the overall quality of their diet (e.g., eating more processed, high sugar, high-fat foods). Compounding this issue is that researchers have found large proportions of participants have reported becoming more sedentary since the beginning of the pandemic. For example, Zeigler [] found that 63.2% of respondents had become more sedentary, with most reporting they spent upwards of 7 h per day “just sitting”. Combined, these factors are likely to cause rapid weight gain, a phenomenon which has been termed “covibesity” [].

The consequences of changes in diet and physical activity have been captured in a longitudinal study conducted by Bhutani and colleagues []. Specifically, they found that 41.2% of their participants (N = 727) reported gaining weight during the peak, early phase of lockdown (April, May 2020). Of those that gained more than five pounds in this phase, one-third reported continuing to gain weight (September, October 2020). Further, 28% of participants reported they had maintained their weight gain [].

Another more recent longitudinal analysis, using objective measures for sedentary behaviour and weight, was conducted with 257 Japanese participants who underwent health check-ups in 2018 (pre-pandemic) and in 2020 (during the pandemic). For both time points, sedentary behaviour was objectively measured using an accelerometer for at least 7 days, and visceral fat area (VFA) was objectively measured using abdominal bioelectrical impedance analysis. Compared with data in 2018, sedentary behaviour and VFA increased significantly during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the authors suggesting that a decrement in the amount of time spent being sedentary is important to prevent weight gain, especially when behavioural restrictions are imposed, as occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic [].

1.3. Purpose

In this experimental study, we investigate if evaluations of a male versus female patient, who experienced a substantial weight gain (30 pounds), differ when those reasons may be classified as external (i.e., COVID-19) or internal (i.e., unhealthy lifestyle). In addition, we examine individual difference variables that, as noted earlier, have been associated with individuals’ evaluations of weight: sex, anti-fat attitudes, internalization of appearance standards, and body mass index (BMI).

Based on previous research in the realms of attribution theory and stigma, we predict that: (1) a patient whose weight gain is attributable to external, uncontrollable factors (i.e., COVID-19) will be evaluated more positively than a patient whose weight gain is attributable to internal, controllable factors (i.e., unhealthy lifestyle choices) (H1); (2) as females are subject to greater penalties when violating sociocultural standards of attractiveness, participants’ evaluations of an overweight female patient will be more negative than their evaluations of an overweight male patient (H2); and (3) the aforementioned sex difference will be most pronounced in the internal attribution condition (i.e., the female patient who has gained weight ostensibly due to “unhealthy lifestyle choices” will be evaluated most negatively [H3]).

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 160 participants who self-identified as female provided analysable data. Of the 235 participants that completed this study, 75 were removed for the following reasons: 43 failed one or more of the manipulation checks contained in the medical record they were assigned to read, 3 completed the survey in less than four minutes, 3 resided outside of North America, 22 identified as male, and 4 did not report a gender. Participants had a mean age of 39.4 (SD = 15.6). Their average BMI was 26.4 (SD = 7.6), which, according to the National Institute of Health BMI classifications, suggested that 5% (n = 8) of participants were underweight, 48.8% (n = 78) were of average weight, 20.6% (n = 33) were overweight, and 25.6% (n = 41) were obese.

2.2. Procedure

Following ethical approval, the study was advertised on the Department of Psychology and Health Studies participant pool at the University of Saskatchewan, Facebook (Psychology Research Group and the Research Survey Exchange Group), Reddit (r/SampleSize and r/PlusSize), and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Of these, 6 participants were from Reddit subgroups; 24 were from the subject pool, and 130 participants were from MTurk. Participants who completed the survey through the participant pool and Amazon received compensation for their involvement (i.e., one bonus mark for a psychology class and 0.25 cents, respectively).

Those wishing to participate received a letter of invitation providing a general overview of the study. From there, participants were instructed to read and agree to a consent form that outlined the purpose of the study, its benefits and risks, details pertaining to confidentiality and anonymity, and a statement highlighting the participant’s right to withdraw at any time without penalty.

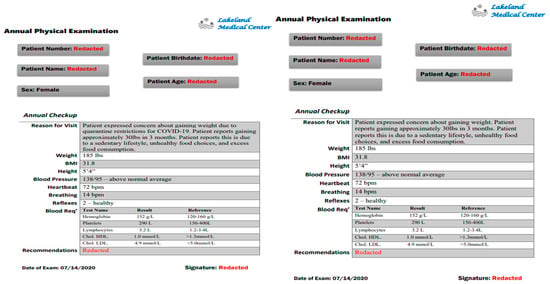

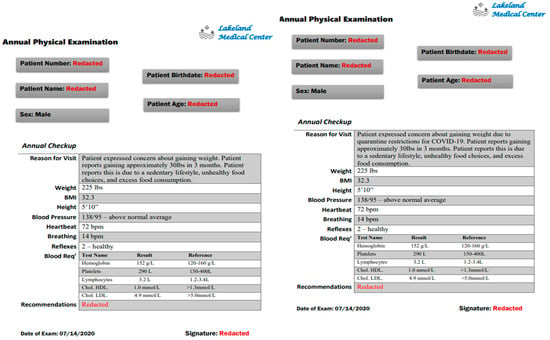

Participants providing their consent were then assigned randomly to one of four conditions: (1) a medical record detailing a male patient whose 30-pound weight gain is due to internal factors (e.g., unhealthy eating); (2) a medical record detailing a male patient whose 30-pound weight gain is due to external factors (e.g., inactivity due to COVID-19); (3) a medical record detailing a female patient whose 30-pound weight gain is due to internal factors (e.g., unhealthy eating); and (4) a medical record detailing a female patient whose 30-pound weight gain is due to external factors (e.g., inactivity due to COVID-19).

Across all vignettes, the patient had gained 30 pounds in three months. For the male patient, his weight had gone from 195 lbs to 225 lbs. Given his stated height (5′10), his BMI increased from 28 (overweight) to 32.3 (obese). The female patient had similarly gained 30 pounds: 155 lbs to 185 lbs. As the female patient’s height was 5′4, her BMI increased from 26.6 (overweight) to 31.8 (obese). Thus, based on their BMIs, both male and female patients went from being classified as overweight to being classified as obese.

The following number of participants was assigned to each condition: male patient (internal, unhealthy lifestyle) = 40; female patient (internal, unhealthy lifestyle) = 41; male patient (external, COVID-19) = 37; and female patient (external, COVID-19) = 42.

In each condition, participants read a medical vignette (see Appendix A) that was designed to resemble an actual patient medical record. The first half of the medical form included information such as the patient’s number, name, birthdate, age, and sex. To make the form look as realistic as possible, most information was redacted for privacy concerns, except for patient’s sex.

The second half of the form detailed a reason for the visit to the physician and the results of different medical assessments. The reason for the visit was either internal (i.e., indicating the patient simply gained weight) or external (e.g., indicating the patient gained weight because of COVID-19 quarantine restrictions). In both conditions, the reason for visiting indicates that the patient believes their weight gain results from many factors (e.g., sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy food choices, and excess food consumption). The patient’s results from different medical assessments (e.g., weight, height, blood pressure, heartbeat, breathing, and reflexes) were included in addition to results from a blood requisition (e.g., haemoglobin, platelets, lymphocytes, and cholesterol). Below these details was a section for the doctor’s recommendation, which also was redacted.

Participants completed three manipulation checks that appeared with the medical form to ensure they attended to important information (e.g., patient’s sex, one of the stated reasons for patient’s weight gain; and the amount of weight gained by the patient). Participants answering any of these questions incorrectly were removed from data analysis. Following the medical form, participants were directed to a semantic differential scale in which they rated the patient on a series of polarized adjectives (e.g., Do you believe this individual is healthy/unhealthy, attractive/unattractive?). Lastly, participants were directed to a series of measures including a demographic survey, which assessed variables such as sex (Please specify your sex: male, female, other), personal body weight (Please specify, to the best of your knowledge, your weight in pounds), and height (Please specify, to the best of your knowledge, your height in feet), as well as scales that assessed internalization of sociocultural standards of attractiveness and anti-fat attitudes (specifically fear of fat and perceived controllability of weight). After participants completed the online survey, they were presented with a debriefing form that outlined the study’s true purpose.

2.3. Measures

The Anti-Fat Attitudes Questionnaire (AFAQ; []) examines negative attitudes towards overweight and obese individuals. For this study, only two subscales of the AFAQ were utilized: (1) Fear of Fat and (2) Willpower. The Fear of Fat subscale measures an individual’s fear of becoming fat themselves whereas the Willpower subscale examines beliefs about the controllability of weight gain. Both subscales contain three items and are scored on a 10-point Likert scale (0 = very strongly disagree; 9 = very strongly agree). Scores can range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating greater anti-fat attitudes. We found scores on the two subscales to be reliable (Fear of Fat subscale: α = 0.864, Ω = 0.865; Willpower subscale: α = 0.81, Ω = 0.82) with 95% CIs of 0.82–0.90 and 0.75–0.85, respectively.

The Fat Phobia Scale (FPS; []) is a 14-item self-report survey that uses opposite pairs of adjectives like “lazy/industrious” and “attractive/unattractive” to assess evaluations of overweight and obese people. The FPS uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = an attribute stereotypical of an overweight person; 5 = an attribute stereotypical of an average-weight person), with total scores ranging from 14 to 70. Items were scored such that higher scores denote greater fat disparagement. In the current study, the FPS had excellent scale score reliability (α = 0.90, Ω = 0.90) with a 95% CI of 0.88–0.92.

The Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4R (SATAQ-4R; []) measures internalization and pressure to achieve appearance ideals. Only the internalization items were used. These 15 items are further divided into three subscales representing thin ideal internalization (TI, 4 items), muscular ideal internalization (MI, 5 items), and internalization of general attractiveness (GI, 6 items). Each subscale uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = definitely disagree; 5 = definitely agree). Thus, possible scores can range from 4 to 20 for thin ideal internalization; 5 to 25 for muscular ideal internalization; and 6 to 30 for internalization of general attractiveness. Higher scores on each subscale reflect greater internationalization. We found scores on these subscales to be reliable: thin (α = 0.84, Ω = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.80–0.88), muscular (α = 0.91, Ω = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.89–0.93), and general (α = 0.79, Ω = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.74–0.84).

The Social Desirability Scale-17 (SDS-17; []) examines the likelihood that respondents may dissemble when answering surveys by selecting response options that cast them in a desirable light. The SDS-17 includes 16 items answered using two response categories (0 = false; 1 = true), in which seven items are reverse keyed. Scores can range from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating greater impression management. We found that scale scores possessed satisfactory reliability (α = 0.80, Ω = 0.79) with a 95% confidence interval of 0.75–0.84.

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

Means and standard deviations were computed for all scales. Bivariate correlations also were calculated to determine the degree of association between variables of interest. To test the study’s hypotheses, an ANCOVA was conducted: the independent variables (type of attribution; internal versus external) and sex of patient (male versus female) were fixed factors. Fat disparagement as measured by the Fat Phobia Scale served as the dependent variable. Any measured variables that correlated with scores on the Fat Phobia Scale were treated as covariates.

3.2. Key Findings

Means and standard deviations for all scales are presented in Table 1. Two variables were noticeably above scale midpoints: participants’ overall fat disparagement (i.e., the Fat Phobia Scale [FPS]), which was 9.7 points above the midpoint (42) and participants’ internalization of general appearance standards (i.e., the General Attractiveness subscale of the SATAQ-4R), which was 6 points above the midpoint (18). Mean scores for all other measures were ±3 points from the midpoint. It should be mentioned that the only measure falling slightly below the midpoint was the muscular internalization subscale of the SATAQ-4R.

Table 1.

Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for key measures.

Participants’ mean level of fat disparagement was calculated for each experimental cell. The values were: male patient/internal attribution = 54.83 (SD = 8.09); female patient/internal attribution = 50.22 (SD = 7.38); male patient/external attribution = 49.95 (SD = 10.78); female patient/external attribution = 51.73 (SD = 8.03). A series of one-sample t-tests were conducted to determine if these values differed from the scale midpoint of the FPS. All t values were statistically significant (ranging from 4.85 to 10.03, p < 0.001) revealing appreciable levels of fat disparagement across all conditions.

Bivariate correlations revealed that participants’ level of fat disparagement, as measured by the FPS, correlated significantly, albeit weakly, with perceptions of weight being controllable (i.e., participants who believed that weight is under one’s personal control evaluated the medical patient more negatively). Fat disparagement also correlated significantly with two of the three internalization subscales. First, as participants’ internalization of general standards of appearance (i.e., their desire to be physically attractive) increased, so did their level of fat disparagement. Participants’ internalization of a muscular/athletic ideal correlated negatively with fat disparagement (i.e., greater internalization was associated with lower levels of disparagement). Surprisingly, neither participants’ internalization of the thin ideal nor their own personal fear of becoming fat correlated significantly with fat disparagement of the medical patient. Participants’ body mass index also did not correlate significantly with fat disparagement (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among key measures.

To determine if any associations differed as a function of the patient’s sex, correlations were conducted separately for the male versus female patient (see Table 3). Overall, the direction and strength of the correlates for disparagement of a male versus female patient were similar. Two differences, however, were noted: (1) participants’ internalization of general standards of attractiveness correlated significantly with disparagement of a male patient only; and (2) participants view that weight is controllable correlated significantly with disparagement of a female patient only.

Table 3.

Bivariate correlations among key variables, stratified by sex of patient.

Hypotheses 1 through 3 were jointly tested using a 2 (internal/external attribution) × 2 (male patient/female patient) ANCOVA. As noted earlier, three variables correlated with fat disparagement (weight controllability, internalization of general standards of appearance, and internalization of the muscular ideal). Thus, each of these variables was treated as a covariate. It should be noted that participants’ self-reported age did not correlate with fat disparagement, r = 0.134, p = 0.09; thus, age was not treated as a covariate. Participants’ total score on the FPS, which denotes fat disparagement of the patient outlined in the medical record, served as the dependent variable.

No statistically significant interaction was observed between type of attribution (internal/external) and sex of the patient F (1, 153) = 3.499, p = 0.063, partial ŋ2 = 0.022. As well, no statistically significant main effects were observed: attribution, F (1, 153) = 2.274, p = 0.134, partial ŋ2 = 0.015 or sex of patient, F (1, 153) = 1.014, p = 0.316, partial ŋ2 = 007.

4. Discussion

In this experimental study, we examined how participants would evaluate overweight patients if information on ostensible reasons for weight gain (unhealthy lifestyle choices versus inactivity attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic) and the sex of the patient (male versus female) were provided. Further, we examined whether individual difference variables such as anti-fat attitudes, in particular fear of fat and the belief that weight is controllable, internalization of idealized standards of attractiveness (i.e., thin, muscular, and general appearance ideals) as well as body mass index were associated with fat disparagement.

Our results identified three intriguing correlations. First, for both the male and female patient, participants reporting stronger internalization of the muscular ideal reported lower levels of fat disparagement. Second, for the male patient only, stronger internalization of general standards of attractiveness correlated with greater disparagement. Third, for the female patient only, as participants’ belief that weight is controllable increased, so did their level of fat disparagement. These findings underscore that the correlates of fat disparagement may differ depending on whether the target (i.e., in our case, a medical patient) is male or female. For example, Langdon and associates [] reported that scores on internalization of an athletic ideal (the precursor to the SATAQ-4R’s internalization of the muscular ideal) correlated positively with fat disparagement. However, the authors did not examine this correlation separately for men and women. Given our findings, it is possible that, for women, internalization of the muscular ideal is associated with lower levels of fat disparagement whereas for men, those idealizing muscularity may be more likely to disparage fat people. The potentially unique role of internalization of the muscular ideal among women is evident in a recent study by Anić and colleagues []. Using a convenience sample of 262 young Croatian women, these researchers found that endorsement of the muscular ideal correlated weakly with endorsement of the thin ideal and did not correlate significantly with perceived appearance-related pressures from family, media, peers, and significant others. In contrast, internalization of the thin ideal correlated significantly with all sources of appearance-related pressures. Additional research is needed to identify whether women and men’s internalization of the muscular ideal plays a similar or dissimilar role vis-à-vis its association with fat disparagement.

Our finding that the perceived controllability of weight correlated with fat disparagement of the female patient only is compatible with the feminist perspective that because women are expected to be attractive, those who violate this expectation by being overweight are subject to greater stigma than their male counterparts []. According to this perspective, overweight women are viewed as unattractive because of the common stereotype that fat women lack the willpower/discipline to “control” their weight [].

Contrary to our predictions, we did not find that the attribution manipulation affected fat disparagement. Thus, participants did not appear to distinguish between a patient who reported gaining 30 pounds due to COVID-19-based restrictions or one who gained weight because of unhealthy “lifestyle” choices. We also did not find the anticipated main effect for sex (i.e., we had proposed that the female patient would be evaluated more negatively than the male patient) or the anticipated weight gain attribution by sex interaction (i.e., we had predicted that the female patient who reported gaining weight for reasons that may be construed as an internal attribution would be subjected to the greatest level of fat disparagement).

The statistically non-significant main effects and interaction that we identified in this study should not be (mis)construed as reflecting an absence of fat disparagement. Across all experimental cells, the mean score on the FPS was significantly above the scale midpoint. Thus, based on limited details contained on a bogus medical form, participants still felt comfortable making judgments about patients’ laziness, attractiveness, endurance, and level of industry among other characterological traits.

Such anti-fat bias is not surprising. Conducting a secondary analysis of data reflecting a nationally representative sample of Canadians, Côté and associates [] found that substantial proportions of respondents evidenced anti-fat attitudes. Specifically, 32% agreed with items measuring the perceived controllability of weight and 36% reported being fearful of gaining weight themselves. The authors also make the cogent observation that large proportions of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed with items that reflect the constituent elements of anti-fat bias; namely, dislike of fat people (26%), fear of fat (32%), and the perception that weight is a matter of willpower and control (45%). As the authors note, “[the absence of agreement or disagreement might be] indicative of a covert form of stigma that may or may not be expressed, depending on circumstances” [] (p. 4). Similarly, in a recent experimental study, 99 Turkish dieticians were randomly assigned to a vignette featuring an obese or non-obese client seeking “dietetic management” for lactose intolerance []. The researchers found that participants evaluated the obese client as less attractive, lazier, having poorer self-control, less endurance, lower self-esteem, and being more self-indulgent and insecure than those who evaluated the normal weight client. Findings such as these, which are evident among experts in diet and nutrition, underscore the pernicious nature of anti-fat attitudes.

Importantly, anti-fat attitudes also may harm those who hold them. A group of researchers found recently the belief that fat individuals lack willpower was longitudinally associated with a stronger drive to increase muscularity and symptoms of body dysmorphia []. These findings suggest that internalizing weight-based stigma can push individuals towards unhealthy and rigid appearance goals, revealing the damaging effects of anti-fat bias on perceivers as well as recipients.

4.1. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

While we used manipulation checks to ensure that relevant portions of the fictitious medical record, such as sex of the patient and stated reason for weight gain, were attended to, we did not evaluate the degree to which participants regarded the medical record as realistic []. A review of the comments provided by participants upon completing the survey did not reveal any suspicions about the authenticity of the medical record we used. However, going forward, we would advise researchers to assess the perceived realism and authenticity of stimulus materials such as simulated medical records.

Another limitation concerns the narrow depiction of the patient in each medical record; that is, we focused on the sociodemographic variables of sex and weight status. However, anti-fat bias exists in a nexus of marginalized identities such as race, social status, and sexual orientation. For example, Vartanian and Silverstein [] reported that an overweight target was described as lazier when represented in a low status occupation (i.e., a janitor) versus one of higher status (i.e., a surgeon). This finding suggests that weight status and social class interact such that fat disparagement may be greater for obese targets depicted as occupying a lower socioeconomic stratum (also see []). Also, in accordance with the view that anti-fat bias is best examined through an intersectional lens, Foster-Gimbel and Engeln [] documented that, among a community sample of 215 self-identified American gay men, those reporting anti-fat bias (defined as having received or witnessed weight-based prejudice), were significantly older and had higher BMIs than those who had not witnessed anti-fat bias in their communities. Collectively, this research underscores the need to use medical records that depict patients who are more multidimensional.

Also warranting discussion is the restricted racial and sex composition of the participants used in our research. Hebl and Heatherton [], for example, observed that Black and White women in their study evaluated Black and White photographs of varying body sizes differently. White participants derogated large White women targets in terms of their intelligence, attractiveness, career acumen, success in relationships, overall happiness, and popularity. No statistically significant findings were noted for Black women and their assessments of large White women. When evaluating a large Black woman, White participants similarly evaluated them negatively on the preceding six variables (e.g., intelligence, attractiveness, career acumen, etc.). Black women, however, only denigrated a large Black woman target on the dimension of attractiveness. With to respect to men, researchers have shown consistent gender differences, with men reporting greater dislike of fat people and stronger belief that weight is controllability, and women reporting greater fear of becoming fat (e.g., []).

It should be stressed that we asked participants to report their sex (e.g., Please specify your sex: male, female, other), and not their gender. To avoid definitional slippage, we have opted to use sex throughout this paper rather than use sex and gender interchangeably. Inconsistency with respect to the application of sex and gender terminology has been criticized [] and we echo that concern. However, because we are more interested in the sociocultural underpinnings of sex (i.e., gender), in future, we will ask participants to specify their gender identity rather than their sex.

Beyond race, sex, and gender, other sociodemographic variables that are relevant to anti-fat attitudes warrant inclusion. Take, for example, participants’ socioeconomic status. A group of researchers examined anti-fat prejudice among a large sample of Spanish citizens (N = 1248) []. Results indicated that those occupying lower income strata reported the greatest dislike of obese persons and were more likely to believe that obesity is attributable to a lack of willpower []. The role that income potentially plays in vignette studies akin to the one we conducted awaits investigation.

Finally, researchers should consider incorporating pictorial stimuli that manipulates the location of the patient’s body fat. Krems and Neuberg [] found that body shape (i.e., the location of fat on the body) was an important determinant of weight stigma. Specifically, across three samples (two from the US [ns = 191 and 295] and one from India [N = 263]) greater negativity was directed at an overweight female target depicted as having abdominal fat rather than gluteofemoral fat. Thus, simply reporting a target’s weight or body mass index may not capture the aesthetic underpinnings of weight stigma.

4.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study have significant implications for healthcare settings, particularly in how clinicians may unconsciously assess or interact with patients who are overweight or have obesity. Despite the lack of influence from attribution (e.g., whether weight gain was due to lifestyle or pandemic-related factors), the consistent presence of fat disparagement suggests that anti-fat bias can be readily activated, even when patients are described neutrally. This underscores the need to address weight stigma in medical training, raising awareness of how implicit biases shape clinical impressions. Evidence shows that educational interventions, such as structured courses and ethics-based sessions, can reduce weight bias among healthcare professionals, leading to better outcomes for patients [].

Furthermore, the differing associations between fat disparagement and beliefs such as internalisation of appearance ideals and perceptions of weight controllability suggest that interventions should target these attitudes. Challenging simplistic beliefs about personal responsibility for body weight, promoting nuanced understandings of health, and critically examining beauty standards may help mitigate bias. However, while weight bias education in medical curricula can contribute to a less biased physician workforce, recent research indicates that implicit bias training alone may be insufficient. To achieve lasting change, these efforts should be paired with systemic adjustments to healthcare environments that sustain discriminatory practices (e.g., lack of diversity in leadership, inequitable access to resources, and organisational cultures that reinforce stereotypes). Addressing these structural issues is essential for ensuring that implicit bias training leads to tangible improvements in patient care [].

5. Conclusions

Anti-fat attitudes remain a harmful force in shaping how individuals view themselves and others. Researchers have shown that higher anti-fat attitudes are linked to stronger internalization of narrow beauty ideals and greater engagement in disordered eating behaviours, particularly among young women. These attitudes contribute to body dissatisfaction and perpetuate stigma against individuals in larger bodies, reinforcing harmful social norms and psychological distress. The participants in our study provided quite negative characterological appraisals based on limited information contained in a bogus medical record. One wonders how their appraisals would have been influenced had we incorporated other contributors to anti-fat bias such as social class, race, and age into the medical records. We recommend that researchers continue to use the vignette method to better understand this insidious and robust form of prejudice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.B., M.J.K. and T.G.M.; methodology, M.B., M.J.K. and T.G.M.; formal analysis, M.B. and T.G.M.; data curation, T.G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., M.J.K., D.R., M.A.M. and T.G.M.; writing—review and editing, D.R., M.A.M. and T.G.M.; supervision, M.J.K. and T.G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This project was approved by the Department of Psychology and Health Studies Ethics Review Board, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada (23 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Medical Form Vignettes

Figure A1.

Female target vignettes (internal attribution, and COVID-19 attribution: left and right respectively).

Figure A2.

Male target vignettes (internal attribution, and COVID-19 attribution: left and right respectively).

References

- Boero, N. Obesity in the media: Social science weighs in. Crit. Public Health 2013, 23, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.; Arons, A.; Pomeranz, J.L.; Siddiqi, A.; Hamad, R. Geographic and longitudinal trends in media framing of obesity in the United States. Obesity 2020, 28, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, M.; Lee, C. “Too fat, too thin”: Understanding bias against overweight and underweight in an Australian female university student sample. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.J.; Cash, T.F.; Bubb-Lewis, C. Prejudice toward fat people: The development and validation of the anti-fat attitudes test. Obes. Res. 1997, 5, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.R.; Rosen, L.H. Predicting anti-fat attitudes: Individual differences based on actual and perceived body size, weight importance, entity mindset, and ethnicity. Eat Weight Discord 2015, 20, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buote, V.M.; Wilson, A.E.; Strahan, E.J.; Gazzola, S.B.; Papps, F. Setting the bar: Divergent sociocultural norms for women’s and men’s ideals appearance in real-world contexts. Body Image 2011, 8, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidekrueger, P.I.; Sinno, S.; Tanna, N.; Szpalski, C.; Juran, S.; Schmauss, D.; Ehrl, D.; Ng, R.; Ninkovic, M.; Broer, P.N. The ideal buttock size: A sociodemographic morphometric evaluation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 20e–32e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monks, H.; Costello, L.; Dare, J.; Boyd, E.R. We’re continually comparing ourselves to something: Navigating body image, media, and social media ideals at the nexus of appearance, health, and wellness. Sex Roles 2021, 84, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.B.; Vartanian, L.R.; Nosek, B.A.; Brownell, K.D. The influence of one’s own body weight on implicit and explicit anti-fat bias. Obesity 2006, 14, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, A.; Schindler, S.; Reinhard, M.A. The heavy weight of death: How anti-fat bias is affected by weight-based group membership and existential threat. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standen, E.C.; Ward, A.; Mann, T. The role of social norms, intergroup contact, and ingroup favoritism in weight stigma. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochu, P.M.; Morrison, M.A. Implicit and explicit prejudice towards overweight and average-weight men and women: Testing their correspondence and relation to behavioural intentions. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 147, 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, C.; Kornblet, S.; Muldoon, A. Not all are created equal: Differences in obesity attitudes between men and women. Women’s Health Issues 2009, 19, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovančević, A. Some predictors of anti-fat prejudices: Joint role of gender, body self-confidence, and BMI. Facta Univ.-Philos. Sociol. Psychol. Hist. 2023, 22, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, D.; Tybur, J.; Latner, J. Disgust sensitivity, obesity stigma, and gender: Contamination psychology predicts weight bias for women, not men. Obesity 2011, 11, 1803–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zidenberg, A.M.; Sparks, B.; Harkins, L.; Lidstone, S.K. Tipping the scales: Effects of gender, rape myth acceptance, and anti-fat attitudes on judgments of sexual coercion scenarios. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP10178–NP10204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovančević, A.; Jović, M. The relation between anti-fat stereotypes and anti-fat prejudices: The role of gender as a moderator. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 125, 1687–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, T.; Lampman, C.; Lupfer-Johnson, G. Assessing bias against overweight individuals among nursing and psychology students: An implicit association test. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 3504–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Attribution Theory. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; Weiner, I.B., Craighead, W.E., Eds.; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 184–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, A.; Rief, W.; Braehler, E. Stigmatizing attitudes toward obesity in a representative population-based sample. Obesity 2008, 16, 1529–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R.L.; Lebowitz, M.S. Beyond personal responsibility: Effects of causal attributions for overweight and obesity on weight-related beliefs, stigma, and policy support. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 1176–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, P.T. Quantifying Elements of Contemporary Fat Discourse: The Development and Validation of the Fat Attitudes Assessment Toolkit. Ph.D. Thesis, Murdoch University, Perth, Australia, 2019. Murdoch University Research Repository. Available online: https://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/52182/1/Cain2019.pdf.

- Our World in Data (OWID), University of Oxford. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_pandemic_by_country_and_territory (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Khan, M.; Smith, J. Covibesity, a new pandemic. Obes. Med. 2020, 19, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeigler, Z. COVID-19 self-quarantine and weight gain risk factors in adults. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2021, 10, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutani, S.; vanDellen, M.R.; Cooper, J.A. Longitudinal weight gain and related risk behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic in adults in the US. Nutrients 2021, 13, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, K.; Ozato, N.; Yamaguchi, T.; Bushita, H.; Sudo, M.; Yamashiro, Y.; Mori, K.; Katsuragi, Y.; Sasai, H.; Murashita, K.; et al. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic with changes in objectively measured sedentary behaviour and adiposity. Int. J. Obes. 2023, 47, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, C. Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-interest. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, J.G.; Scheltema, K.E.; Robinson, B.E. Fatphobia scale revisited: The short form. Int. J. Obes. 2001, 25, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, L.M.; Harriger, J.A.; Heinberg, L.J.; Soderberg, T.; Thompson, J.K. Development and validation of the sociocultural attitudes towards appearance questionnaire-4-revised (SATAQ-4R). Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stober, J. The Social Desirability Scale-17 (SDS-17): Convergent validity, discriminant validity, and relationship with age. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2001, 17, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, J.; Rukavina, P.; Greenleaf, C. Predictors of obesity bias among exercise science students. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2016, 40, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anić, P.; Pokrajac-Bulian, A.; Mohorić, T. Role of sociocultural pressures and internalization of appearance ideals in the motivation for exercise. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 125, 1628–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A. The confounding of fat, control, and physical attractiveness for women. Sex Roles 2012, 66, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, M.; Forouhar, V.; Edache, I.Y.; Alberga, A.S. Weight bias among Canadians: Associations with socio-demographics, BMI and body image constructs. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 354, 117061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya Cebioğlu, I.; Dumlu Bilgin, G.; Okan Bakir, B.; Gül Koyuncu, A. Weight bias among dietitians: Does the weight status of the patients change the dietary approaches? Rev. Nutr. 2022, 35, e210214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, W.; Sonnenblick, R.; Kinkel-Ram, S.S.; Stanley, T.B.; Clancy, O.M.; Smith, A.R. Longitudinal relationships between anti-fat attitudes and muscle dysmorphia symptoms. Body Image 2024, 51, 101786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanian, F.; Roudsari, R.L.; Haidari, A.; Bahmani, M.N.D. A narrative on the use of vignette: Its advantages and drawbacks. J. Midwifery Reprod. Health 2020, 8, 2134–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, L.R.; Silverstein, K.M. Obesity as a status cue: Perceived social status and the stereotypes of obese individuals. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, E319–E328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovančević, A.; Milićević, N.; Milenović, M. ‘Fat’, female and unprivileged: Exploring intersectionality, perceiver characteristics, and eye movements. Scand. J. Psychol. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Gimbel, O.; Engeln, R. Fat chance! Experiences and expectations of antifat bias in the gay male community. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2016, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebl, M.R.; Heatherton, T.F. The stigma of obesity in women: The difference is black and white. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 24, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macho, S.; Andrés, A.; Saldaña, C. Anti-fat attitudes among Spanish general population: Psychometric properties of the anti-fat attitudes scale. Clin. Obes. 2022, 12, e12543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordall, J.; Bui, S.; Koupantsis, A.; Yu, T.; Lanovaz, J.L.; Prosser-Loose, E.J.; Morrison, T.G.; Oates, A.R. A scoping review on the current state of sex-and gender-based analysis (SGBA) in standing balance research. Gait Posture 2025, 119, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krems, J.A.; Neuberg, S.L. Updating long-held assumptions about fat stigma: For women, body shape plays a critical role. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2022, 13, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, G.; Watkins, P.A. Addressing medical students’ negative bias toward patients with obesity through ethics education. AMA J. Ethics 2018, 20, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, M.B.; Erondu, A.I.; Smith, N.A.; Peek, M.E.; Woodruff, J.N.; Chin, M.H. Eliminating explicit and implicit biases in health care: Evidence and research needs. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).