Abstract

Recently, the kinetic improvement of the nitrogenation reaction of lithium hydride (LiH) to form lithium imide (Li2NH) by adding a scaffold was reported. The scaffold prevents agglomeration of Li2NH and maintains the activity of LiH, achieving a reduction in reaction temperature and an increase in reaction rate. In this work, a Li–Si alloy, Li22Si5, was used as a starting material to form nano-sized LiH dispersed in a Li alloy matrix. Lithium nitride (Li3N) is generated by the reaction between Li22Si5 and N2 to form Li7Si3, and then Li3N is converted to LiH with ammonia (NH3) generation during heat treatment under H2 flow conditions. Since Li3N is formed at the nano-scale on the surface of alloy particles, LiH generated from the above nano-Li3N is also nano-scale. The differential scanning calorimetry results indicate that direct nitrogenation of LiH in the alloy matrix occurred from around 280 °C, which is much lower than that of the LiH powder itself. Such a highly active state might be achieved due to the nano-crystalline LiH confined by the Li alloy as a self-transformed scaffold. From the above experimental results, the nano-confined LiH in the alloy matrix was recognized as a potential NH3 synthesis technique based on the LiH-Li2NH type chemical looping process.

1. Introduction

To utilize unstable and distributed renewable resources, efficient and cost-effective techniques for energy storage and transportation are being strongly demanded. H2 is one of the most promising energy carriers for long-term storage, with its high gravimetric energy density and many advantages. On the other hand, the unfavorable properties of H2 itself, such as low volumetric energy density, high flammability, and harsh liquification conditions, are still challenging. Therefore, various kinds of H2 carriers, including H2 storage alloys and metal hydrides, are being investigated [1,2,3,4,5]. Ammonia (NH3) is an outstanding H2 and/or energy carrier because of its high volumetric and gravimetric H2/energy density and mild liquification conditions [6,7].

For the establishment of a system that converts renewable energies into NH3 onsite, small-scale and distributed types of NH3 synthesis techniques are required. The Haber–Bosch process is conventionally used for industrial NH3 mass production, in which NH3 is synthesized under high pressure (10–35 MPa) and temperature (400–600 °C) [8,9]. Considering the utilization of renewable energies, this method is not suitable for downsizing because it lowers the scale merits. Thus, the novel NH3 synthesis techniques adapted with unstable renewable energy sources, which can be operated under lower temperature and pressure conditions, are required. The dissociation of stable nitrogen (N2) molecules is considered the bottleneck in the NH3 synthesis reaction, and the key to the development of innovative techniques is how to efficiently dissociate N2 under mild conditions. One approach is the improvement of conventional catalysts by adding promoters to enhance N2 dissociation activity [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Ru is well known as an active metal because of its high N2 dissociation properties. Ru-based catalysts exhibit high activity even at low temperatures and have become a trend in catalyst development [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. On the other hand, since Ru is an expensive precious metal, research on methods using less costly elements continues [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Li is a promising element because it can dissociate N2 even at room temperature. Various Li-based NH3 synthesis methods, including electrosynthesis [35,36,37,38], light-driven methods [39,40,41], liquid alloy catalysts [42,43], and heterogeneous catalysts [44,45,46,47,48,49,50], were reported. Many reports focus on chemical looping processes, in which N2 and H2 interact with Li-based materials at different reaction steps. The NH3 production process is not limited by the equilibrium of the direct NH3 formation reaction, different from conventional catalytic synthesis; therefore, the chemical looping processes are expected to achieve efficient NH3 synthesis even under moderate conditions.

A chemical looping process based on lithium hydride (LiH) can generate NH3 below 500 °C under 0.1 MPa [51]. In this process, LiH reacts with N2 to form lithium imide (Li2NH), and then NH3 is produced by heating Li2NH under a H2 flow with the re-formation of LiH. Both nitrogenation and hydrogenation in the LiH system, expressed by reactions (1) and (2), are exothermic reactions with an enthalpy change of ΔH = −79 kJ/mol H2 and −13 kJ/mol NH3, respectively [52]. It was also reported that the nitrogenation temperature and reaction speed of LiH can be drastically improved by mixing Li2O as a scaffold, which prevents the agglomeration of reaction intermediates. Similar scaffold effects were observed for the chemical looping process of sodium hydride [33]. Namely, controlling the reaction environment and sample geometry using scaffolds is effective for improving the reaction properties.

The chemical looping NH3 synthesis using Li and other group 14 element alloys is operated below 500 °C under 0.1 MPa [45]. This process consists of three steps: nitrogenation, NH3 formation, and initial alloy regeneration, as in the following reactions. Li22Si5 reacts with N2 to form Li3N and Li7Si3, and then Li3N reacts with H2 and is converted to NH3 and LiH. At the third step, the initial alloy phase, Li22Si5, is regenerated by releasing H2.

In the process of N2 dissociation by Li alloys, Li3N was formed with a nano-size at around the particle surface [48,49], and therefore LiH could be formed in nano-scale during the reaction (4). Therefore, we expected that this nano-sized LiH formed in the alloy matrix to possess high reactivity with N2, lowering the reaction temperature for the exothermic process. In this case, the host Li alloys would act as the self-scaffold. Since there are no reports about direct nitrogenation of the products after the NH3 generation step for the Li–S system, we investigated the chemical looping process based on Li22Si5 without a regeneration step to know whether nano-scaled LiH can be formed as speculated above or not in this work. Furthermore, the reactivity of the generated LiH was examined. As a result, the nano-confined LiH in the Li alloy matrix showed high reactivity toward N2 dissociation, and the reaction temperature was much lower than that of LiH powder. Thus, this system is recognized as a potential small-scale NH3 synthesis technique operated below 300 °C under 0.1 MPa.

2. Materials and Methods

Li (99%) and Si (99.999%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC (Saint Louis, MO, USA) and used as raw materials, where surface oxide layers of Li granules were roughly removed. A Li alloy, Li22Si5, was prepared by heating a stoichiometric mixture of Li and Si at 500 °C for 10 h in an air-tight stainless-steel reactor under argon (Ar) atmosphere.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Rigaku Holdings Corporation, Tokyo, Japan, SmartLab, Cu, Kα radiation) was used for phase identification of the synthesized alloy and the solid products after the reactions. The hand-milled samples were placed on a glass plate and covered with a polyimide sheet (Du Pont-Toray, Tokyo, Japan, Kapton) to prevent oxidation during measurements. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (TA Instruments, Tokyo, Japan, Q10 PDSC), placed in an Ar-filled glovebox, was used for the thermal analysis of the nitrogenation reaction of the samples. A total of 2–3 mg of sample was placed into an aluminum sample pan (TA Instruments,, Tokyo, Japan, Tzero Lid) and placed in the heating chamber. Before starting DSC measurements, the gas inside the sample chamber was purged with pure N2 and Ar several times, and the measurements were performed in a closed system under atmospheric pressure.

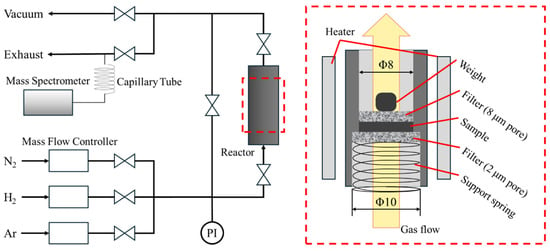

For the NH3 synthesis, the sample powder was loaded into a home-made stainless-steel reactor with an inner diameter of 8 mm and held by stainless-steel filters (SMC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Weight was placed on top of the upper filter to prevent the moving and carrying away of the samples by the gas flow, as shown in Figure 1. The samples were heated under N2 (>99.9999%) or H2 (>99.9999%) gas flow from the bottom side of the sample. The gas flow rate was fixed to 50 cm3/min by mass flow controllers, and the total pressure was kept at 0.1 MPa. A total of 40.8 mg of Li22Si5 was nitrogenated at 500 °C for 10 h under N2 flow. After cooling down to room temperature, the flow gas was switched to H2, and the sample was heated at 300 °C for 15 h. The above experimental procedure was repeated 2 times. After the 1st cycle, the sample was taken out of the reactor. A part of the sample was used for the XRD and DSC measurements, and the remaining sample was used for the 2nd cycle without any treatment. Generated gases were analyzed using a quadrupole mass spectrometer (MS) (MKS Inc., Andover, MA, USA, Microvision 2) connected to the downstream pipeline via about 4 m of capillary tube. All the downstream side pipelines, including the capillary, were kept at 90 °C to prevent adsorption of NH3 on the inner surface of pipelines [33,53]. All the sample handling was performed in a glovebox filled with Ar (>99.9999%) equipped with a circulation gas purifier system (Miwa Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan, MDB-2BL) to avoid any undesired reaction such as oxidation.

Figure 1.

Schematic image of a home-made experimental setup for NH3 synthesis.

3. Results and Discussion

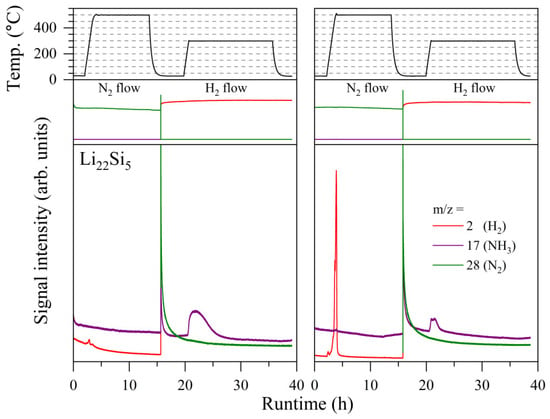

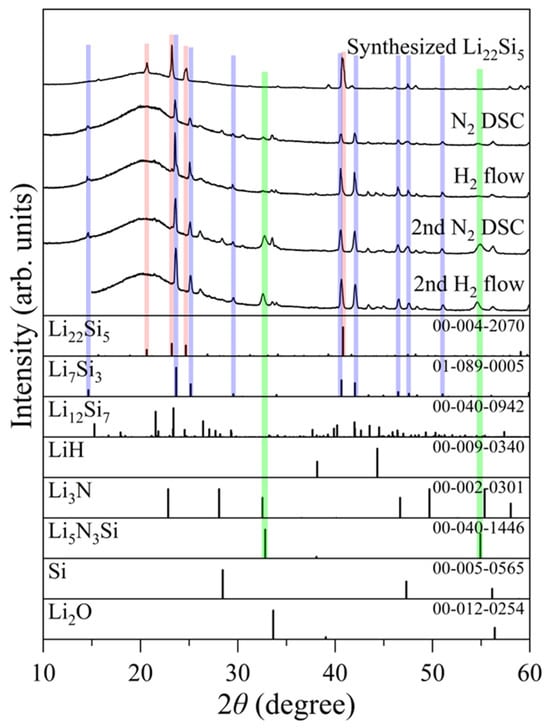

Figure 2 shows the MS spectra of the 1st and 2nd cycles of NH3 synthesis using Li22Si5, where m/z = 2, 17, and 28 correspond to H2, NH3, and N2, respectively; other related signals are shown in Figure S1. Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns before and after each reaction step. In the 1st cycle, NH3 was produced at around 250 °C during the H2 flow experiment following nitrogenation, as reported in a previous paper [45]. This result implies that Li22Si5 reacted with N2 to form Li7Si3 and Li3N in the nitrogenation step, and NH3 was produced from the reaction between Li3N and H2, forming LiH. This is also suggested by the phase change from Li22Si5 to Li7Si3 after the nitrogenation shown in Figure 3, in which a broad peak in the range of 15–35° is a diffraction by a SiO2 amorphous glass plate. Here, the XRD pattern shows peaks assigned to Li7Si3; however, this phase does not produce any NH3 under the H2 flow conditions (see Figure S2). Namely, there are other products, even if they are undetectable in the XRD measurements. The existence of Li3N and LiH was expected based on the experimental facts, which were the reaction temperature of NH3 generation, thermal properties obtained by DSC shown later, and the results reported before [45,49]. The crystalline size of the formed Li3N and LiH is probably nano-scale, where the formation of Li3N with a nano-size by the reaction between the Li alloys and N2 was clarified in previous works [48,49]. Different from the previous work, the formation of Li12Si7 by partial hydrogenation of Li7Si3 during the NH3 generation step was not observed in this experiment, likely due to differences in experimental conditions. The sample amount used for the home-made gas flow system, as shown in Figure 1 in this work, is ten times larger than that used for the thermogravimetry system in previous work, leading to a difference in reaction progress due to the influence of temperature, route, and heat capacity (heat release) of the flow gas.

Figure 2.

MS spectra under N2 and H2 flow under 0.1 MPa pressure for Li22Si5 (upper: full scale data to show the gas switching from N2 to H2, lower: enlarged data to show the detected gases), where m/z = 2, 17, and 28 correspond to H2, NH3, and N2, respectively.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of the Li22Si5 after each step in 2 cycles of chemical looping NH3 synthesis. Red, blue, and green bars indicate peak positions of Li22Si5, Li7Si3, and Li5N3Si, respectively.

In the 2nd cycle, H2 was detected at around 250 °C in the nitrogenation step, and NH3 was produced again in the H2 flow process, indicating that the products after the 1st NH3 generation, which might be composed of Li7Si3 and nano-LiH, successfully react under N2 flow, releasing H2. The main phase after the 2nd nitrogenation is also Li7Si3. Here, the ternary nitride phase, Li5N3Si, was observed as a byproduct, which did not contribute to the NH3 generation and decomposed under H2 flow below 300 °C (Figures S3 and S4). Although Li5N3Si is recognized as a stable impurity without any influence on the main reactions, the Li5N3Si formed by consuming reactive Li in the sample possibly affects the durability in long cycles. The optimization of reaction conditions to suppress the formation of Li5N3Si phase and further investigation of the detailed reaction pathway would be required for improvement of the system efficiency. Although quantitative analyses were difficult in this study due to experimental limitations, it was reported that the NH3 generation rates are about 100 and 700 μmol g−1 h−1 for LiH and palladium-doped LiH, respectively [44]. Considering the temperature range, it is expected that the NH3 formation rate would be similar to that of LiH itself.

There are two possible reaction pathways in the 2nd nitrogenation step, which are direct nitrogenation of LiH and continuous reactions of the Li22Si5 regeneration and its nitrogenation. In the former case, LiH reacts with N2 directly by the exothermic process to form Li2NH, and NH3 can be produced via the hydrogenation of Li2NH, as shown in reactions (1) and (2), as reported before [44,51]. In another case, Li7Si3 reacts with LiH to form Li22Si5 with H2 release by the endothermic process following reaction (5), and then Li22Si5 successively reacts with N2 to produce Li7Si3 and Li3N by the exothermic process following reaction (3). The total reaction is described in reaction (6), and it is an endothermic process. The standard heat of formation () of Li7Si3, Li22Si5, LiH, and Li3N is about −250, −640, −91, and −160 kJ/mol, respectively [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. Thus, the ΔH of reactions (5), (3), and (6) is estimated to be around 416, −202, and 214 kJ, respectively. If the nitrogenation process of the cycled samples could be dominated by the regeneration process (reaction (5)), an external heat supply is required. Therefore, the direct nitrogenation of LiH to form Li2NH (reaction (1)) is thermodynamically preferable; however, more than 400 °C is required for activation of this process, considering previous work using the powder state samples.

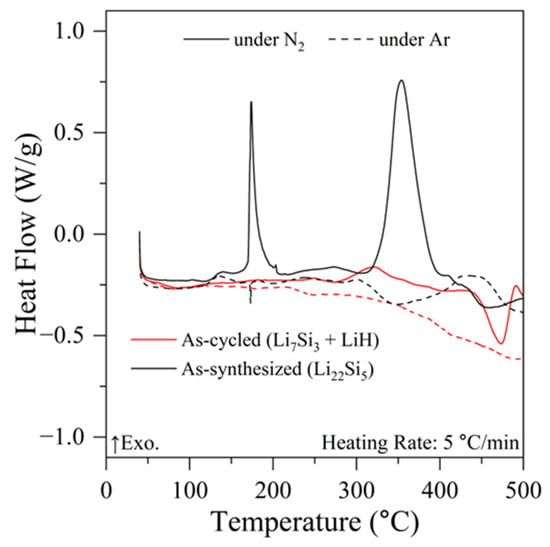

To determine the reaction process during the reaction with N2 of the as-synthesized and cycled samples, the DSC experiments were carried out under N2 and Ar atmospheres. As shown in Figure 4, the synthesized Li22Si5 showed clear exothermic peaks below 200 °C and around 350 °C, and a small endothermic peak appeared around 450 °C under N2 atmosphere (solid black line). A small sharp endothermic peak around 180 °C and small broad peaks above 300 °C were observed under an Ar atmosphere (dashed black line). These peaks obtained from the DSC results under an Ar atmosphere would correspond to the melting of the remaining Li metal used for the sample synthesis and decomposition of tiny impurity alloy phases, such as Li13Si4. The nitrogenation reaction of Li22Si5 is an exothermic and weight-increasing reaction, and these exothermic peaks obtained by DSC are consistent with the successive weight change in thermogravimetric analysis conducted in a previous report [45]. For the sample after one cycle, the heat absorption due to the regeneration process by reaction (5) proceeded at a higher temperature region than 350 °C under Ar. On the other hand, the gradual heat release was observed in the temperature range of 280–400 °C under N2, and this exothermic process probably corresponds to the nitrogenation of LiH expressed by reaction (1). At higher temperatures than 450 °C, thermal reactions were observed. This would be caused by the regeneration of the initial alloy from the kinetically remaining LiH with Li7Si3 (reaction (5)) and the immediate nitrogenation of the alloy to form Li3N (reaction (3)). In the previous experimental studies, it was clarified that the regeneration and nitrogenation reaction of Li22Si5 proceeds below 380 °C and around 200 °C, respectively [45]. Thus, more than 380 °C would be necessary for the regeneration process, and the temperature range was consistent with that observed in this work. The above results revealed that the nitrogenation of LiH was prior to the regeneration reaction of the Li22Si5 phase. The exothermic reaction proceeded from around 280 °C under N2 and might be assigned to be the nitrogenation of LiH; however, the nitrogenation of LiH powders with a 50–100 μm particle size requires around 400 °C, as reported before [52]. From detailed analyses of the nitrogenation process of alloys conducted in a previous study [49], it was revealed that Li3N generated from the alloys possessed a nano-crystalline size, which was characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) techniques. Thus, it is expected that LiH generated from nano-Li3N on the alloy surface during the NH3 generation process would also be nano-sized. In addition to the scaffold effects reported before [52], the surface of LiH nanoparticles may be quite active, in which the nitrogenation reaction at lower temperatures than that of LiH powder would be achieved. The nano-confinement may affect the electronic states on the particle surface, resulting in a decrease in activation energy for the nitrogenation reaction. Further accurate analyses of the chemical state of Li in LiH and Li3N by in situ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) are required to understand the detailed reaction mechanism.

Figure 4.

DSC profiles of synthesized Li22Si5 (black) and the products after 1 cycle (red) under 0.1 MPa pressure of N2 (solid line) and Ar (dashed line) atmosphere.

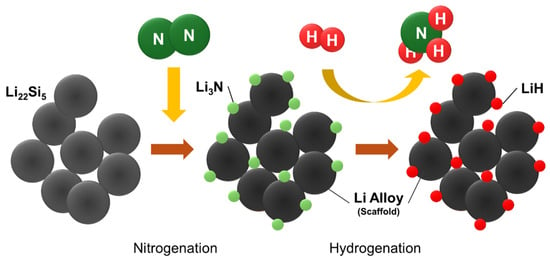

From the nitrogenation and hydrogenation process of Li22Si5, “nano-confined LiH” might be generated in the Li alloy matrix, as shown in the schematic image in Figure 5. In fact, the Li3N and LiH phases were not observed in the XRD analyses, as shown in Figure 3, while the existence of these materials is indicated from the MS and DSC results, suggesting that these phases may be nano-sized. Likely due to the small crystalline size and highly dispersed state, it is speculated that the nano-LiH is quite reactive, resulting in the progress of the exothermic reaction with N2 to form Li2NH at a lower temperature than that of LiH powder. The H2 desorption observed from around 280 °C during the 2nd nitrogenation step in the MS profile would originate from the nitrogenation of the nano-confined LiH. In addition, similar to the Li2O case, the agglomeration of Li2NH would be suppressed by the Li7Si3 matrix as expected. In fact, this phenomenon can be explained by the absence of peaks corresponding to Li2NH in the XRD pattern after the 2nd nitrogenation [52].

Figure 5.

Schematic image of LiH formation at the nano-scale in Li alloy matrix.

From 22. Si5. The reactivity of LiH is enhanced due to the nano-size and the scaffold effect of Li7Si3, resulting in a lower reaction temperature than 300 °C. Here, it is expected that the LiH particles are possibly agglomerated during long-term utilization. However, for the proposed nano-confined LiH supported by the alloy, re-activation (re-formation of nano-confined state) would be easy via the regeneration of Li22Si5 at high temperatures under flow conditions of inert gases, as reported in previous works, and its nitrogenation.

4. Conclusions

In this work, kinetic improvement for the nitrogenation of LiH using Li alloy as a starting material was investigated. Li22Si5 was heated up to 500 °C under a N2 flow to form Li3N, and then the products were heated to 300 °C under a H2 flow. After that, the same reaction procedure was conducted without the alloy regeneration step. The formation of LiH on the Li alloy surface was suggested based on the NH3 generation, its temperature, and comparison with previous studies. The DSC measurement under a N2 and Ar atmosphere revealed that direct nitrogenation of LiH to form Li2NH would occur prior to the regeneration and nitrogenation of Li22Si5 in the 2nd nitrogenation process. Namely, the nitrogenation temperature of LiH was clearly reduced to around 280 °C, which is lower than the nitrogenation temperature (400 °C) of the typical LiH powder of a 50–100 μm particle size. The extraction of Li from Li22Si5 during the nitrogenation leads to the formation of nano-Li3N on the particle surface, and it would result in the formation of LiH at the nano-scale in the Li alloy matrix during the NH3 generation process. This “nano-confined” state of LiH and the contribution of Li alloy as a self-transformed scaffold would realize significant improvement in kinetics and enable LiH to dissociate N2 at such a low temperature. Although further investigation of the reaction mechanism and state of the LiH particles is required, the proposed chemical looping process by the nano-confined LiH in the alloy matrix is recognized as the potential NH3 synthesis technique, which can be operated below 300 °C under 0.1 MPa. In future works, further research on the investigation/improvement of the reaction rate, cyclic properties, NH3 synthesis behaviors with unstable H2 supply from renewables, and design of a practical system including gas purification is required and will be performed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/hydrogen7010003/s1, Figure S1. MS spectra under N2 and H2 flow under 0.1 MPa pressure for Li22Si5 (upper: full scale data to show the gas switching from N2 to H2, lower: enlarged data to show the detected gases); Figure S2. MS spectra under N2 and H2 flow under 0.1 MPa pressure for Li7Si3 (upper: full scale data to show the gas switching from N2 to H2, lower: enlarged data to show the detected gases); Figure S3. MS spectra under H2 flow under 0.1 MPa pressure for Li5N3Si (upper: full scale data to show the gas switching from N2 to H2, lower: enlarged data to show the detected gases); Figure S4. XRD patterns of Li5N3Si before and after the reaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.T. and H.M.; methodology, K.T. and H.M.; validation, K.T.; investigation, K.T.; resources, H.M. and T.I.; data curation, K.T.; writing—original draft preparation, K.T.; writing—review and editing, H.M.; visualization, K.T. and H.M.; supervision, H.M. and T.I.; project administration, H.M.; funding acquisition, H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Kakenhi: Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) 24H00386.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the main text and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted with the powder XRD facilities in the Natural Science Center for Basic Research and Development (N-BARD) at Hiroshima University [NBARD-00059]. This work was the result of using research equipment shared in the MEXT Project to promote public utilization of advanced research infrastructure (Program for supporting construction of core facilities), Grant Number JPMXS0441300026.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lin, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Edalati, K.; Révész, Á. Recent Advances in Metastable Alloys for Hydrogen Storage: A Review. Rare Met. 2022, 41, 1797–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Habermann, F.; Burkmann, K.; Felderhoff, M.; Mertens, F. Unstable Metal Hydrides for Possible On-Board Hydrogen Storage. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 241–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebsz, M.; Pasinszki, T.; Sreenath, S.; Andrews, J.; Ting, V.P. Hydrogen Storage, a Key Technology for the Sustainable Green Economy: Current Trends and Future Challenges. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2025, 9, 5108–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnin, A.S.; Wacławiak, K.; Humayun, M.; Zhang, S.; Ullah, H. Hydrogen Storage Technology, and Its Challenges: A Review. Catalysts 2025, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebsz, M.; Pasinszki, T.; Sreenath, S.; Ting, V.P. Advances in Catalysing the Hydrogen Storage in Main Group Metals and Their Tetrahydroborates and Tetrahydroaluminates. EES Catal. 2025, 3, 1196–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, D.R.; Cherepanov, P.V.; Choi, J.; Suryanto, B.H.R.; Hodgetts, R.Y.; Bakker, J.M.; Ferrero Vallana, F.M.; Simonov, A.N. A Roadmap to the Ammonia Economy. Joule 2020, 4, 1186–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Muhammad, A.; Kaario, O.; Ahmad, Z.; Martti, L. Ammonia as a Sustainable Fuel: Review and Novel Strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 207, 114995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Ammonia Synthesis Catalyst 100 Years: Practice, Enlightenment and Challenge. Chin. J. Catal. 2014, 35, 1619–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiong, Q.; Mu, X.; Li, L. Recent Advances in Ammonia Synthesis: From Haber-Bosch Process to External Field Driven Strategies. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202301775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AIKA, K. Mechanism and Isotope Effect in Ammonia Synthesis over Molybdenum Nitride. J. Catal. 1969, 14, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, M.; Miyashita, K.; Nagasawa, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Hara, M. Ammonia Synthesis Over an Iron Catalyst with an Inverse Structure. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2410313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aika, K.; Yamaguchi, J.; Ozaki, A. Ammonia Synthesis over Rhodium, Iridium and Platinum Promoted by Potassium. Chem. Lett. 1973, 2, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIKA, K. Activation of Nitrogen by Alkali Metal Promoted Transition Metal I. Ammonia Synthesis over Ruthenium Promoted by Alkali Metal. J. Catal. 1972, 27, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, J.; Lan, R.; Tao, S. Development and Recent Progress on Ammonia Synthesis Catalysts for Haber–Bosch Process. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2021, 2, 2000043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, M.; Okuyama, N.; Kurosawa, H.; Hara, M. Low-Temperature Ammonia Synthesis on Iron Catalyst with an Electron Donor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 7888–7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maksoud, W.; Rai, R.K.; Morlanés, N.; Harb, M.; Ahmad, R.; Ould-Chikh, S.; Anjum, D.; Hedhili, M.N.; Al-Sabban, B.E.; Albahily, K.; et al. Active and Stable Fe-Based Catalyst, Mechanism, and Key Role of Alkali Promoters in Ammonia Synthesis. J. Catal. 2021, 394, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, M.; Inoue, Y.; Yamazaki, Y.; Hayashi, F.; Kanbara, S.; Matsuishi, S.; Yokoyama, T.; Kim, S.-W.; Hara, M.; Hosono, H. Ammonia Synthesis Using a Stable Electride as an Electron Donor and Reversible Hydrogen Store. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, M.; Kanbara, S.; Inoue, Y.; Kuganathan, N.; Sushko, P.V.; Yokoyama, T.; Hara, M.; Hosono, H. Electride Support Boosts Nitrogen Dissociation over Ruthenium Catalyst and Shifts the Bottleneck in Ammonia Synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aika, K. Role of Alkali Promoter in Ammonia Synthesis over Ruthenium Catalysts—Effect on Reaction Mechanism. Catal. Today 2017, 286, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, M.; Iijima, S.; Nakao, T.; Hosono, H.; Hara, M. Solid Solution for Catalytic Ammonia Synthesis from Nitrogen and Hydrogen Gases at 50 °C. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttersack, T.; Mason, P.E.; McMullen, R.S.; Schewe, H.C.; Martinek, T.; Brezina, K.; Crhan, M.; Gomez, A.; Hein, D.; Wartner, G.; et al. Photoelectron Spectra of Alkali Metal–Ammonia Microjets: From Blue Electrolyte to Bronze Metal. Science 2020, 368, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osozawa, M.; Hori, A.; Fukai, K.; Honma, T.; Oshima, K.; Satokawa, S. Improvement in Ammonia Synthesis Activity on Ruthenium Catalyst Using Ceria Support Modified a Large Amount of Cesium Promoter. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 2433–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, J.; Wan, S.; Lin, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Hydrogen-Assisted Dissociation of N2: Prevalence and Consequences for Ammonia Synthesis on Supported Ru Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.; Shareef, M.; Zabed, H.M.; Qi, X.; Chowdhury, F.I.; Das, J.; Uddin, J.; Kaneti, Y.V.; Khandaker, M.U.; Ullah, M.H.; et al. Electrochemical Nitrogen Fixation in Metal-N2 Batteries: A Paradigm for Simultaneous NH3 Synthesis and Energy Generation. Energy Storage Mater. 2023, 54, 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shen, L. Recent Advances in NH 3 Synthesis with Chemical Looping Technology. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 18215–18231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marakatti, V.S.; Gaigneaux, E.M. Recent Advances in Heterogeneous Catalysis for Ammonia Synthesis. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 5838–5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, T.; Luo, Y.; Kong, Q.; Li, T.; Lu, S.; Alshehri, A.A.; Alzahrani, K.A.; Sun, X. Recent Advances in Strategies for Highly Selective Electrocatalytic N2 Reduction toward Ambient NH3 Synthesis. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2021, 29, 100766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, W.; Zhou, M.; Ye, J.; He, G.; Chen, H. Recent Advances in Single-Atom Catalysts for Electrochemical Nitrate Reduction to Ammonia. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skubic, L.; Gyergyek, S.; Huš, M.; Likozar, B. A Review of Multiscale Modelling Approaches for Understanding Catalytic Ammonia Synthesis and Decomposition. J. Catal. 2024, 429, 115217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wen, L.; Tu, B.; Huang, Y. Recent Advances of Ammonia Synthesis under Ambient Conditions over Metal-Organic Framework Based Electrocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 340, 123161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Niemann, V.A.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, K.; Pedersen, J.B.; Saccoccio, M.; Andersen, S.Z.; Enemark-Rasmussen, K.; Benedek, P.; et al. Calcium-Mediated Nitrogen Reduction for Electrochemical Ammonia Synthesis. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, F.; Taniguchi, T. Synthesis of Ammonia Using Sodium Melt. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsunematsu, K.; Miyaoka, H.; Shinzato, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Saima, H.; Ichikawa, T. Ammonia Synthesis via Catalytic and Chemical-Looping Process Mediated by Sodium–Nitrogen Solid Solution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 149, 150112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Miyashita, K.; Wu, T.; Kujirai, J.; Ogasawara, K.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Miyazaki, M.; Matsuishi, S.; Sasase, M.; et al. Anion Vacancies Activate N2 to Ammonia on Ba–Si Orthosilicate Oxynitride-Hydride. Nat. Chem. 2025, 17, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepanov, P.V.; Krebsz, M.; Hodgetts, R.Y.; Simonov, A.N.; MacFarlane, D.R. Understanding the Factors Determining the Faradaic Efficiency and Rate of the Lithium Redox-Mediated N2 Reduction to Ammonia. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 11402–11410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Andersen, S.Z.; Statt, M.J.; Saccoccio, M.; Bukas, V.J.; Krempl, K.; Sažinas, R.; Pedersen, J.B.; Shadravan, V.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Enhancement of Lithium-Mediated Ammonia Synthesis by Addition of Oxygen. Science 2021, 374, 1593–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.-L.; Matuszek, K.; Hodgetts, R.Y.; Ngoc Dinh, K.; Cherepanov, P.V.; Bakker, J.M.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Simonov, A.N. The Chemistry of Proton Carriers in High-Performance Lithium-Mediated Ammonia Electrosynthesis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, S.; Deissler, N.H.; Mygind, J.B.V.; Kibsgaard, J.; Chorkendorff, I. Effect of Lithium Salt on Lithium-Mediated Ammonia Synthesis. ACS Energy Lett. 2024, 9, 3790–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Wen, H.; Cui, K.; Wang, Q.; Gao, W.; Cai, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Pei, Q.; Li, Z.; Cao, H.; et al. Light-Driven Ammonia Synthesis under Mild Conditions Using Lithium Hydride. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Chen, Y.; Han, J.-I.; Yoon, H.C.; Li, W. Lithium-Mediated Ammonia Synthesis from Water and Nitrogen: A Membrane-Free Approach Enabled by an Immiscible Aqueous/Organic Hybrid Electrolyte System. Green. Chem. 2019, 21, 3839–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, L.; Pizarro, A.H.; Barawi, M.; García-Tecedor, M.; Liras, M.; de la Peña O’Shea, V.A. Light-Driven Nitrogen Fixation Routes for Green Ammonia Production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 11334–11389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, J.; Tang, Z.; Xi, B.; Yan, P.; Wang, X.; Cao, K.; Yang, B.; Guan, X. Molten Multi-Phase Catalytic System Comprising Li–Zn Alloy and LiCl–KCl Salt for Nitrogen Fixation and Ammonia Synthesis at Ambient Pressure. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 3320–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Meng, X.; Shi, Y.; Guan, X. Lithium-based Loop for Ambient-Pressure Ammonia Synthesis in a Liquid Alloy-Salt Catalytic System. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 4697–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Gao, W.; Wang, Q.; Guan, Y.; Feng, S.; Wu, H.; Guo, Q.; Cao, H.; Guo, J.; Chen, P. Lithium Palladium Hydride Promotes Chemical Looping Ammonia Synthesis Mediated by Lithium Imide and Hydride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 6716–6722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinzato, K.; Tagawa, K.; Tsunematsu, K.; Gi, H.; Singh, P.K.; Ichikawa, T.; Miyaoka, H. Systematic Study on Nitrogen Dissociation and Ammonia Synthesis by Lithium and Group 14 Element Alloys. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 4765–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Miyaoka, H.; Kumar, S.; Ichikawa, T.; Kojima, Y. A New Synthesis Route of Ammonia Production through Hydrolysis of Metal—Nitrides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 24897–24903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.H.; Ruckenstein, E. Highly Effective Li2O/Li3N with Ultrafast Kinetics for H2 Storage. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43, 2464–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Shinzato, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Wang, Y.; Nakagawa, Y.; Isobe, S.; Ichikawa, T.; Miyaoka, H.; Ichikawa, T. Pseudo Catalytic Ammonia Synthesis by Lithium–Tin Alloy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 6806–6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Ichikawa, T.; Wang, Y.; Nakagawa, Y.; Isobe, S.; Kojima, Y.; Miyaoka, H. Nitrogen Dissociation via Reaction with Lithium Alloys. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goshome, K.; Miyaoka, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Ichikawa, T.; Ichikawa, T.; Kojima, Y. Ammonia Synthesis via Non-Equilibrium Reaction of Lithium Nitride in Hydrogen Flow Condition. Mater. Trans. 2015, 56, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Guo, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, Q.; Chang, F.; Pei, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, L.; Chen, P. Production of Ammonia via a Chemical Looping Process Based on Metal Imides as Nitrogen Carriers. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagawa, K.; Gi, H.; Shinzato, K.; Miyaoka, H.; Ichikawa, T. Improvement of Kinetics of Ammonia Synthesis at Ambient Pressure by the Chemical Looping Process of Lithium Hydride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 2403–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunematsu, K.; Shinzato, K.; Gi, H.; Tagawa, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Saima, H.; Miyaoka, H.; Ichikawa, T. Catalysis of Sodium Alloys for Ammonia Synthesis around Atmospheric Pressure. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 15282–15289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Bette, N.; Taubert, F.; Hüttl, R.; Seidel, J.; Mertens, F. Experimental Determination of the Enthalpies of Formation of the Lithium Silicides Li7Si3 and Li12Si7 Based on Hydrogen Sorption Measurements. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 704, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębski, A.; Zakulski, W.; Major, Ł.; Góral, A.; Gąsior, W. Enthalpy of Formation of the Li22Si5 Intermetallic Compound. Thermochim. Acta 2013, 551, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevrier, V.L.; Zwanziger, J.W.; Dahn, J.R. First Principles Study of Li–Si Crystalline Phases: Charge Transfer, Electronic Structure, and Lattice Vibrations. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 496, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Materials Project. Available online: https://next-gen.materialsproject.org/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Taylor & Francis. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 86th ed.; Lide, D.R., Ed.; CRC Press (An Imprint of Taylor and Francis Group): Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; p. 2544. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5. [Google Scholar]

- NIST Chemistry WebBook. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G.; et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: A Materials Genome Approach to Accelerating Materials Innovation. APL Mater. 2013, 1, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.K.; Huck, P.; Yang, R.X.; Munro, J.M.; Dwaraknath, S.; Ganose, A.M.; Kingsbury, R.S.; Wen, M.; Shen, J.X.; Mathis, T.S.; et al. Accelerated Data-Driven Materials Science with the Materials Project. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.