Abstract

Many nations have been investing in hydrogen energy in the most recent wave of development and numerous projects have been proposed, yet a substantial share of these projects remain at the conceptual or feasibility stage and have not progressed to final investment decision or operation. There is a need to identify initial potential sites for green hydrogen production from renewable energy on an objective basis with minimal upfront cost to the investor. This study develops a decision support system (DSS) for identifying optimal locations for green hydrogen production using solar and wind resources that integrate economic, environmental, technical, social, and risk and safety factors through advanced Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) techniques. The study evaluates alternative weighting scenarios using (a) occurrence-based, (b) PageRank-based, and (c) equal weighting approaches to minimize human bias and enhance decision transparency. In the occurrence-based approach (a), renewable resource potential receives the highest weighting (≈34% total weighting). By comparison, approach (b) redistributes importance toward infrastructure and social indicators, yielding a more balanced representation of technical and economic priorities and highlighting the practical value of capturing interdependencies among indicators for resource-efficient site selection. The research also contrasts the empirical and operational efficiencies of various weighting methods and processing stages, highlighting strengths and weaknesses in supporting sustainable and economically viable site selection. Ultimately, this research contributes significantly to both academic and practical implementations in the green hydrogen sector, providing a strategic, data-driven approach to support sustainable energy transitions.

1. Introduction

The commitment to achieving carbon neutrality [1] has led to a worldwide transition towards developing and adopting renewable energy systems to replace conventional fossil fuel-based sources. Wind and solar energy are prominent renewable resources [2,3]; however, direct electrification faces significant challenges and limitations in some areas, primarily due to technological and economic limits [4], which has led to the consideration of hydrogen as an alternative in such applications [5]. Global hydrogen demand was around 97 Mt in 2023, mainly for fertilizer and methanol production and use in oil refineries [6]. The Hydrogen for Net Zero scenario, a collaborative projection by the Hydrogen Council and McKinsey & Company, highlighted the projected need for hydrogen. The estimate, considered optimistic yet plausible, states that the demand for hydrogen might increase to 140 MT by 2030 and 660 MT by 2050, with much of this increase for non-traditional applications [7].

While these projections have triggered a rapid expansion of announced green hydrogen projects, recent evidence indicates a pronounced gap between ambition and implementation, with only a small fraction of announced capacity reaching final investment decision or timely operation [8]. This implementation gap reflects rising electrolyzer and financing costs, limited availability of long-term offtake agreements, and uncertainty in the design and execution of hydrogen-specific support policies, undermining the translation of project announcements into realized capacity [8]. As a result, despite growing ambition, the expansion of green hydrogen production remains uncertain, underscoring the urgent need to identify cost-effective and scalable production pathways. Since production costs are largely determined by electricity prices and capacity factors of renewable power sources [9,10], the spatial selection of green hydrogen production facilities—aligned with high-quality renewable resource availability—emerges as a critical determinant of future supply viability.

Most proposed projects have an opportunistic element to them—government subsidies or indirect policy support—or strategic value to the proponent. However, for governments or global project investors wishing to seriously investigate hydrogen as an option, it is important to have an initial idea of which regions could be expected to provide the best opportunity for sustainable hydrogen production at a reasonable cost point. This represents a gap in the project development cycle that, while partially explored through existing MCDM and GIS-MCDM studies, remains insufficiently addressed in terms of objective, first-pass global screening prior to detailed spatial or techno-economic analysis.

This study aims to create a decision support system (DSS) that assists authorities and decision-makers in identifying the most suitable locations worldwide for utilizing solar and wind resources to produce hydrogen energy. A comprehensive review of the available literature (described in Section 2) showed a notable gap in optimal and objective location planning for green hydrogen production facilities. To tackle this issue, this study presents a framework combining competing and critical factors to identify priority areas for hydrogen production. This approach can offer significant support for countries aiming to accelerate the incorporation of green hydrogen into their energy mix. Another objective of this study is to minimize human bias in the decision-making process by relying exclusively on data-driven solutions.

To identify the current state of the art in research literature, a comprehensive search was conducted on academic sources via Web of Science and Google Scholar to collect research articles related to “site suitability analysis,” and “hydrogen production,” or “power plants.” Following the search, 15 articles pertinent to the initial search were identified and 205 articles for the second. 30 of these involved comprehensive investigation into site suitability for establishing green hydrogen production facilities. In addition, the citation chain approach resulted in three additional publications, bringing the total number of articles for this literature review to 32. This includes one in-depth review paper. The research showed that although all studies included Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) procedures similar to Figure 1, there were notable variations in the specific methodology used. The detailed variations, advantages and disadvantages of those methodologies can be seen in the Supplementary Material (Table S1 and S2, Figure S1). The variety of MCDM methods, the alternatives compared for selection, and the criteria used for exclusion or classification, has ultimately led to a range of analytical procedures designed for diverse purposes. The articles included site selection for hydrogen production plants (26 studies), refueling stations (1 study), and hydrogen storage facilities (4 studies). Moreover, variations were noted in the approach to sensitivity analysis and validation. The criteria used in decision-making exhibited significant variation, and numerous criteria were frequently employed concurrently without explicit evaluation of their interconnections, potentially resulting in biased outcomes. The technique of validating results using an alternative MCDM approach to compare choices is widely acknowledged to improve reliability [11]. However, this practice was not followed in this study, but instead, robustness is assessed through transparent indicator selection, objective weighting approaches, scenario-based comparison, the results are compared to the existing previous literature results when given and a case study demonstrates how the framework can be operationalized in practice in Section 4.2. Comparative validation using multiple MCDM ranking methods is therefore viewed as complementary and more appropriate, where stakeholder preferences are clearly specified.

Figure 1.

Process flow of the multi-criteria decision-making problem (adapted from [12]).

The previous studies were conducted in multiple countries, including 4 in Afghanistan, 3 in Algeria, 5 in China, 12 in Iran, 2 in Uzbekistan, and 1 each in Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and Turkey, while 2 studies did not include a case study. The extensive geographical scope not only emphasizes the worldwide interest in hydrogen production but also the need for site suitability evaluations that consider specific local characteristics that are applicable globally for fair comparison.

In order to identify the best sites for hydrogen production (particularly when dealing with a global or national scale), it is logical to firstly exclude those locations that are inappropriate from the scope of analysis [13,14,15]. This elimination limits the data-processing requirement for prioritizing the remaining areas. The exclusion criteria apply to both natural and man-made features, such as land use, aquatic bodies, waterways, roads, railways, power lines, and their respective buffer zones, to guarantee safety and compliance. However, the literature suggests that the application of these exclusion criteria has been limited: only 7 studies have implemented constraints to remove undesirable areas.

The results of MCDM processes are influenced by the weighting of criteria, which is predominantly determined by expert judgment [12]. Nevertheless, the inherent heterogeneity in decision-making is frequently disregarded in previous research. It is a complex challenge to accurately capture the genuine performance of alternatives in practical scenarios, particularly when qualitative criteria are involved. In addition, there is a clear challenge to precisely evaluate qualitative criteria [16]. Moreover, in the human sense, there is always a constraint of inaccuracy and ambiguity, which certainly limits consistent evaluation of the alternative outcomes [17]. Consequently, qualitative criteria should be omitted or objectively quantified with proxies to enhance reliability.

There are apprehension and uncertainty regarding the future performance of alternatives when they are evaluated using established criteria, due to the complexity of production plant operations and the constraints of decision makers’ experience. Fuzzy sets have been developed in the previous literature to address this ambiguity by integrating the uncertainty that arises from the forward-looking nature of project evaluations, ambiguities in opinions, and knowledge limitations [11,17,18,19,20,21]. By allowing elements to have differing degrees of membership within a set, such approaches can help manage uncertainty in subjective assessments. However, such approaches may not be sufficient in scenarios where uncertainty is caused by rapidly evolving technological landscapes, incomplete data, or highly dynamic environmental factors. In order to improve reasoning, a more comprehensive understanding of risks and prospective outcomes is necessary, necessitating objective data-driven weighting. This study also highlights this research gap by emphasizing the necessity for objective weighting methods that are more robust and incorporate realistic and quantitative proxy/data for both qualitative and quantitative criteria.

The importance of decision-makers must be further emphasized where subjective decision-making is still utilized. With the exception of two of the identified articles, the norm in the literature has been to assign equal weight to all experts in the final decision-making process. This fails to consider the correlation between experts’ opinions and their varying degrees of expertise. One study [22] has suggested a novel method incorporating Tversky’s similarity principle to determine the correlation between experts and implement a distance deviation maximization model that utilizes probabilistic language to estimate weight. Another study utilizes Pythagorean fuzzy weighted average aggregation to ascertain the weights for each expert, thereby acknowledging the bounded rationality of DMs and their behavioral proclivities, which they characterized using a power function-based utility model [17]. A 2022 study [16] described how the quality of decisions could be enhanced by simulating the characteristics of DMs through generalized utility functions. Despite that enhancement, most are based on expected utility theory, which frequently fails to account for the psychological factors affecting DMs. Moreover, it has been emphasized by others [23] that the average number of specialists involved in these studies is less than 10, which is insufficient to balance the weights they provide accurately or to encompass the complete spectrum of perspectives. Introducing substantial ambiguity and inaccuracy in the absence of expert input can significantly inhibit the accurate evaluation of alternative outcomes. The robustness and accuracy of decisions are compromised by the inherent subjectivity in weighting and the limited number of expert opinions.

Furthermore, there is a lack of systematic evaluations of MCDM methodologies tailored explicitly for the renewable hydrogen production sector, a relatively unexplored area of research. The absence of an exhaustive analysis suggests a significant research opportunity, as has previously been noted [12]. This study therefore aims to contribute to bridging this gap by implementing a methodical framework that employs objective weighting of indicators and criteria.

In response to these limitations, this study proposes a structured, first-pass decision support framework for green hydrogen site selection that prioritizes objectivity, transparency, and global applicability. The framework explicitly separates early-stage screening from later spatial optimization, focusing on indicator selection, classification, and weighting as a foundation for subsequent GIS-based implementation. The novel contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- An objective, literature-driven indicator filtering and weighting approach without reliance on individual expert judgment to minimize human bias.

- Application of an occurrence based and PageRank weighting method to capture interdependence among indicators and avoid overemphasis of redundant criteria.

- Explicit integration of risk and safety considerations alongside economic, technical, environmental, and social criteria.

- A scenario-based weighting structure enabling transparent comparison between objective, interdependency-aware, and equal-weighting approaches.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology of this study is divided into four major stages. First, indicators are collected from existing literature on site selection of green hydrogen production plants. These indicators are screened to eliminate vague, inaccessible and out-of-scope criteria for analysis. Second, these filtered indicators are reclassified and categorized for a structured framework. This is followed by two weighing methods to quantify the relative importance of each indicator and finally, scenario analysis is applied.

2.1. Collation of Indicators and Criteria

The fundamental direction of this study is based on the notion that it is better to use specific quantitative indicators while rejecting vague and qualitative ones, as mentioned in Section 2. In screening the potential indicators (refer to Supplementary Material S1, Table S3 and Supplementary Material S2), those found to not be self-explanatory, where the authors did not provide sufficient explanation on how they were defined or give representative proxies to calculate them, such as the impact on the local economy, ecological influence, visual impact, solvency, etc., were eliminated. Moreover, those criteria for which data cannot be collected through open-sourced databases were also rejected to make global analysis possible and to enhance the open and accessible use of the framework. These include public satisfaction, employment demand, market competition risk, unemployment rate, distance to bird habitat, etc. This filtering stage is a standalone process that aims to refine the indicator pool before any modeling, ensuring only measurable, transparent, and globally accessible indicators are retained. In contrast, the optimization step involves applying mathematical models to pre-filtered indicators to determine the most suitable sites. Location filtering must be done before the optimization model to reflect the actual condition of site suitability analysis. The criteria that can be used in the optimization model, such as initial investment cost, operation and maintenance cost, construction cost, and financing risk, and the output of it will also be rejected, such as levelized cost of electricity, levelized cost of green hydrogen, energy production, and carbon emission reduction. Moreover, criteria not applicable due to the scope of the studies will also be rejected if the criteria are for other types of resources, such as geothermal (in this case). The indicator filtering process highlights a fundamental trade-off between analytical objectivity and decision completeness. While socio-economic and qualitative indicators are undeniably influential in real-world hydrogen project success, the primary objective of this framework is to reduce early-stage uncertainty and search space using indicators that are measurable, comparable and easy to collect data from readily available sources.

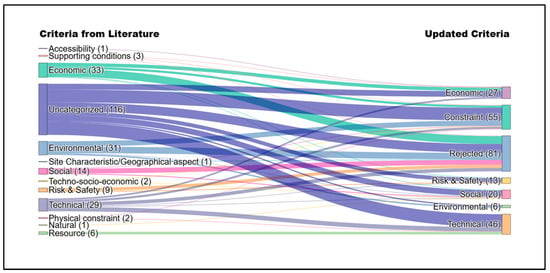

The criteria count can be seen in Figure 2, with a total of 248 unique criteria on the left (the existing literature) and their reclassification on the right (current study). Initially, the majority of the requirements were categorized as economic (33), environmental (31) and technical criteria (29), with a lower count for risk and safety factors (9) and social criteria (14). However, in the hydrogen economy, social and risk factors are key indicators that cannot be deemphasized when considering hydrogen’s highly flammable nature. Comprehensive safety protocols and risk management are essential to prevent accidents and ensure integration into existing energy systems [24]. While some of these will be integrated in detailed plant design, there are factors which can be applied to the site selection phase. Therefore, addressing the underrepresentation of these crucial factors is vital to enhance the holistic development of projects, ensuring they are safe, accepted by communities, and successfully integrated into the broader energy landscape.

Figure 2.

Reclassification of indicators from previous literature.

2.2. Framework

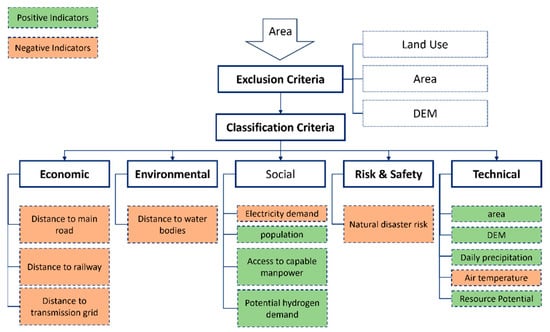

Indicators are the most important structural component of MCDM and can alter the output significantly. Therefore their selection requires careful and systematic consideration [25]. In the framework, indicators can serve two purposes: exclusion/constraint or classification. Some indicators are used for both purposes, as mentioned by [12] depending on the applied threshold and decision context. For instance, land area and digital elevation model (DEM) data are employed for both exclusion and classification. Minimum area thresholds may be used to exclude sites that are too small to accommodate infrastructure, while DEM values may identify locations with prohibitive slope or altitude. At the same time, these indicators can inform the ranking of acceptable sites—for example, preferring sites with larger contiguous areas or moderate elevation for construction ease and scalability. Exclusion indicators identify unsuitable areas by discarding those that would be legislatively or fundamentally ineligible, while classification indicators classify the remaining suitable locations [13].

Indicators were reorganized to harmonize those with the same meaning as in Section 2.1, and those that could be described as the more common indicators are renamed. For example, sunshine hours and wind hours are effectively the same as resource potential where it is used in the reviewed studies [26]. These indicators are classified into criteria categories based on their occurrence in the previous literature. The detailed grouping can be seen in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S3 and S4). The application flow of this framework can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Decision-making framework for site suitability analysis of green hydrogen production plants from solar and wind energy. Green indicators denote positive indicators, where higher values increase site suitability, while orange indicators denote negative indicators, where higher values reduce suitability and therefore require inverse normalization. (Bold text represents criteria while regular text denotes indicators grouped under each criterion).

2.3. Weighting Methods

Two alternative weighting methods were applied, on the basis of occurrence and citation as assumed priority within the academic community relevant to the specific area of investigation.

2.3.1. Occurrence-Based Weighting

This methodology outlines an approach to measure the importance of different indicators by analyzing the frequency with which they are used in academic articles within the scope. It consists of two primary steps: the computation of raw weights and the normalization of these weights to enable a comparative comparison of indicators. This technique allows an objective assessment of the importance assigned to each criterion by the academic community based on empirical data.

Calculation of Raw Weights

After collecting the indicator count, the raw weights are calculated by adding the total number of times each indicator is used in all the reviewed articles. The raw weights provide an initial quantitative assessment of each indicator’s relative significance or emphasis.

Normalization of Weights

Normalizing the raw weights is crucial to ensure that the resulting weights are proportionally comparable. The normalization formula employed is:

where Wi represents the normalized weight of the ith indicator, Ci is the raw count of occurrences for the ith indicator, and n is the total number of the indicator. This method is especially advantageous in areas where there may be a lack of actual or experimental evidence, but there is scholarly literature that shows the case in the construction of green hydrogen production plants. As this approach uses quantitative weights to convert scholarly occurrences, it allows for an objective assessment of the thematic concentrations and gaps within the scope of study.

2.3.2. PageRank Algorithm

The initial purpose of the PageRank algorithm was to assign a ranking to web pages on the Internet. The core concept is that a webpage is deemed significant if it is connected to other prominent webpages. It employs a simulation of a random surfer who navigates across web pages by clicking on links randomly. The probability of a page being visited is then calculated as a metric of its significance [27]. Adapting the PageRank algorithm to assess the weights of the indicators through the network follows a similar principle: indicators are considered more important if a larger number of articles consistently utilize them. Analyzing indicators in networks offers a detailed comprehension of the importance and interconnectedness of different criteria within the site suitability analysis of green hydrogen production plants. Therefore, the process entails the creation of a network, where nodes represent the indicators and edges indicate the linkages between them.

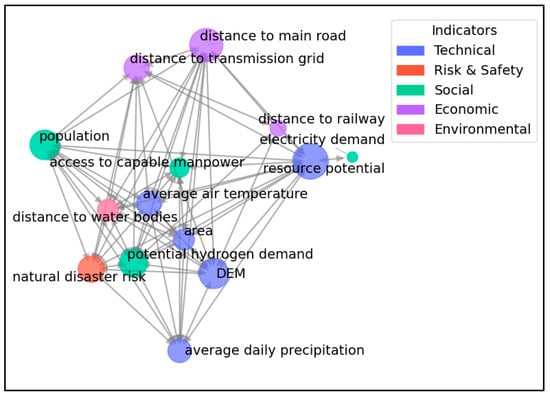

Network Construction

The network is constructed as a directed graph as in Equation (2) and visually as in Figure 4 for Scenario 2—which will be explained in Table 1:

where represents a set of nodes representing an indicator, and represents a set of edges representing relationships between this indicator by being mentioned in the same article. Each node corresponds to a distinct indicator. The edges between the nodes represent relationships with an edge. from node to node indicates that an article cites both indicator and indicator .

Figure 4.

Network diagram of indicators and its network of Scenario 2. (Nodes represent indicators, while edges indicate the direction of influence).

Table 1.

The main scenarios for the decision framework.

The weight of each edge is set to the number of documents that cite both indicators and . This raw co-occurrence frequency is used as a direct measure of the strength of the relationship between the two indicators:

Initialization

Each node (criterion) is assigned an initial PageRank value. Typically, this initial value is uniform across all nodes:

where N is the total number of nodes in the graph.

Mathematical Formulation for Iteration

The PageRank algorithm is employed to determine the importance of each node within the graph. The PageRank values are updated iteratively based on the inbound links and their respective PageRank values. The PageRank for a node is calculated using the iterative formula:

where:

is the damping factor, usually set to 0.85, representing the probability of continuing the random walk from one node to another.

is the total number of nodes in the graph.

represents the set of nodes that link to node (i.e., nodes such that there exists an edge from to ).

is the sum of the weights of all outbound links from node which normalizes the contribution of each node:

Convergence

The iteration continues until the PageRank values reach convergence, when the value difference between consecutive iterations is less than a preset threshold, particularly 10−6 in this instance. This recurrent method guarantees that the rankings settle, reflecting a condition of equilibrium in node influence determined by the network structure. In the PageRank-based weighting, minor changes in indicator occurrence or the addition/removal of weak co-occurrence links are expected to have limited impact on highly connected indicators, whose importance is reinforced through multiple network pathways. Conversely, sparsely connected or context-specific indicators may exhibit greater relative variability under such perturbations [27]. Larger structural changes to the indicator network would warrant formal perturbation-based sensitivity testing, which is identified as future work.

Higher PageRank scores signify greater impact or credibility. The results can be verified using conventional metrics of occurrence-based weighting methods to assure dependability and reliability. This methodology offers a strong foundation for using the PageRank algorithm to provide meaningful assessments of indicator weights using networks, specifically under academic research and strategic planning in scholarly disciplines.

In this context, a high PageRank value does not simply reflect frequent use of an indicator, but rather its centrality within the broader decision structure. Indicators with high PageRank act as “enablers” that repeatedly co-occur with diverse technical, environmental, economic, social, or risk-related criteria, suggesting that they play a systemic role in shaping site suitability.

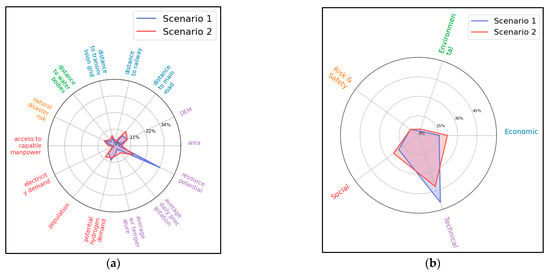

For example, an indicator such as distance to main roads may not always receive the highest standalone importance in individual studies as in Figure 5, but if it frequently appears alongside resource potential, population proximity, and infrastructure access, it will accumulate a higher PageRank score than the Scenario 1. Practically, this means that improving performance on a high-PageRank indicator is more likely to positively influence overall site suitability because it supports multiple decision dimensions simultaneously. Conversely, indicators with low PageRank tend to be more isolated or context-specific and therefore exert a more limited influence on the final ranking.

Figure 5.

Weights of (a) indicators and (b) criteria for Scenarios 1 and 2.

2.4. Scenario Building

The scenarios for calculating the weights of indicators and criteria are differentiated based on the approach and weighting methods. The approach can be categorized into two alternatives: bottom-up, which aggregates the indicators’ weight to criteria; and top-down, which distributes the weights equally from criteria to indicators. The former allows for a detailed analysis of the indicators, while the latter emphasizes a holistic view from the outset. The weighting methods are occurrence-based weighting, PageRank algorithm, and equal weighting method. The first method is straightforward and rooted in empirical evidence but may not fully capture the nuances of decision-making. The second method provides a more dynamic weighting that considers the influence of one indicator over others through the network, offering a more interconnected and systematic view. The last two in the comparative scenarios are oversimplified yet democratic and unbiased while enhancing transparency. However, these may not accurately reflect the process in practice, as not all factors are likely to contribute equally to the decision outcome in all contexts. The detailed structure of core scenarios can be seen in Table 1 and the comparative scenarios in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative scenarios for the decision-making framework.

The combinations of approach and weighting method considered were selected deliberately rather than exhaustively. Occurrence-based weighting and the PageRank algorithm are both indicator-level weighting methods that rely on the relative importance and interrelationships among individual indicators. These methods are therefore consistent with a bottom-up approach, where indicator weights are first derived and then aggregated to the criteria level. Applying occurrence-based or PageRank-based weighting within a top-down structure would require assigning equal importance to criteria prior to indicator weighting, which would partially negate the informational content captured by literature frequency or network interdependence. Such combinations would introduce redundancy without providing additional analytical insight beyond the bottom-up formulations already examined. For this reason, top-down approaches were paired only with equal weighting—Scenario 4, which serves as a transparent benchmark rather than an indicator-driven prioritization scheme. This targeted scenario selection ensures conceptual coherence while allowing meaningful comparison between empirically derived, interdependency-aware, and neutral weighting strategies.

3. Results

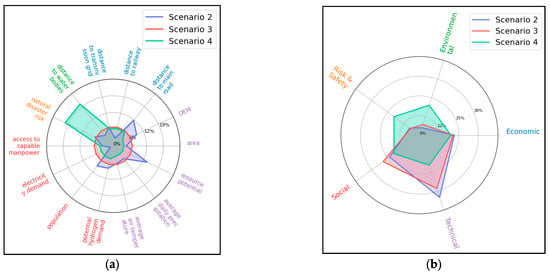

3.1. Scenario 1 and 2

As in Figure 5, in Scenario 1, which applies the Occurrence-Based Method, the highest weight is allocated to resource potential (34%), followed by potential hydrogen demand (10%), DEM (10%), and distance to main road (9%). This reflects a strong emphasis on technical feasibility and demand-related criteria. In contrast, Scenario 2—based on the PageRank algorithm—presents a more balanced distribution, reducing the dominance of resource potential (14%) and slightly elevating weights across multiple economic and social indicators such as distance to main road (12%), population (10%), and DEM (10%). Notably, indicators that received minimal attention in Scenario 1, like electricity demand (0.5%) and access to capable manpower (2%), gain relatively higher prominence under the PageRank-derived weights (1% and 4%, respectively), suggesting that this method captures a broader network of interdependencies among indicators. Overall, while Scenario 1 prioritizes core technical and demand-driven factors, Scenario 2 presents a more interconnected perspective that raises the relative importance of supporting infrastructure and social context.

The inclusion of indicators with similar meanings in multiple studies often leads to redundancy within the research framework, as mentioned in Section 2.1. Each of these indicators, though slightly different, contributes to an overlapping assessment of resource potential for energy production. Consequently, when an occurrence-based method is used for determining weights, this redundancy can result in what might appear as an overemphasis on indicators such as resource potential, potential hydrogen demand, and distance to main roads. The method counts each occurrence of these related indicators, potentially magnifying their perceived importance through what could be described as double or triple counting. This redundancy affects weight distribution and could skew the decision-making process towards favoring locations with optimal wind conditions, sometimes at the expense of other equally important factors. It’s crucial to recognize these overlaps and consider the aggregate impact of related indicators, rather than viewing them in isolation, to ensure a balanced and comprehensive evaluation of potential sites for green hydrogen production. Such awareness can lead to more refined and effective weighting strategies that accurately reflect the true importance of each factor in the context of the overall project objectives.

The weights for the criteria of both scenarios are roughly similar, with a strong emphasis on technical criteria followed by social and economic criteria; however, the nuances in the weights of each indicator for criteria are relatively different. Based on the differences observed between the two scenarios, important implications arise for decision-making in hydrogen site selection. Scenario 1, with its heavy weighting on technical factors like resource potential and demand indicators, is highly suitable for targeted investments focused on maximizing technical efficiency and immediate market potential. This scenario implies prioritizing locations with abundant renewable resources and clear, measurable hydrogen demand, thus being beneficial for stakeholders with shorter-term, economically driven objectives. Conversely, Scenario 2 introduces a broader, interconnected consideration of criteria, spreading importance across economic, social, and infrastructure. This balanced distribution suggests a more holistic decision-making framework, favorable for long-term planning and policy development. Such an approach emphasizes sustainable development, supporting infrastructure, social readiness, and resilience. Stakeholders aiming for comprehensive regional development, minimizing risks, or fostering broader economic and social benefits may find Scenario 2 more aligned with their strategic objectives, which align with the objective of the current study. Based on the reasons above, despite the computational simplicity of the occurrence-based method in Scenario 1 compared to the resource-intensive PageRank Algorithm in Scenario 2, we believe Scenario 2 is worth the complexities and potential overheads associated with the iterative calculations required for a more appropriate weighting system.

3.2. Example Application of the Framework and Weights: Case Study in Australia

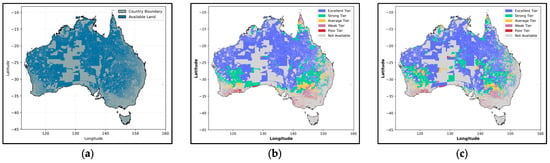

To demonstrate how the proposed decision support system (DSS) can be operationalized within a geographic information system (GIS) environment, an illustrative application using Australia is presented. Australia was selected due to the availability of consistent, high-resolution national datasets and its relevance to large-scale green hydrogen deployment. This example is intended to illustrate the workflow and interpretability of the framework rather than to identify final or optimal project locations. Figure 6a presents the outcome of the spatial exclusion stage, in which unsuitable areas are removed prior to ranking based on land-use constraints, minimum contiguous area requirements for large scale solar hydrogen plants, and topographic limitations derived from a digital elevation model (DEM). This exclusion step reflects the first pass filtering logic of the framework and substantially reduces the spatial decision space, ensuring that only technically and physically feasible land remains for subsequent assessment.

Figure 6.

(a) Spatial exclusion of unsuitable areas and relative suitability classification of available land in Australia, using (b) Scenario 1 and (c) Scenario 2. Data sources can be found in the Supplementary Material (Table S5).

Figure 6b,c show the classification and relative suitability ranking of the remaining available land using indicator weights derived from Scenario 1 and Scenario 2, respectively. Both scenarios apply the same indicator set and exclusion rules; however, differences in weighting logic led to distinct spatial suitability patterns. Scenario 1 yields broader areas classified as highly suitable, reflecting the dominance of frequently cited technical indicators in the literature. In contrast, Scenario 2 produces a relatively differentiated spatial structure. This illustrates how network-based weighting moderates redundancy effects and emphasizes indicators that support multiple aspects of site suitability simultaneously. Importantly, this illustrative application is not intended to represent site-level optimization, project feasibility, or techno-economic performance. Rather, it demonstrates how the proposed DSS functions as a transparent, data-driven first-pass screening tool that can be readily implemented prior to detailed spatial optimization or techno-economic analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Equal Weighting

Comparing Scenario 2 with Scenarios 3 and 4, which focus on simplicity and fairness to align with broader project goals, distinct differences in the weighting distribution emerge as in Figure 7. In real-world decision contexts, equal weighting can be preferable when stakeholder priorities are contested, reliable information on relative importance is unavailable, or neutrality is required to avoid perceived bias. In early-stage policy or exploratory planning settings, equal weighting provides a neutral reference by treating all criteria symmetrically. Scenario 3 represents a uniform distribution, allocating precisely 7% roughly to each indicator, disregarding their contextual importance or interdependencies, suggesting a democratic approach that values all factors equally in the decision-making process. This can be beneficial when no single indicator is expected to dominate the decision, promoting a balanced view. However, criteria weights vary naturally from the number of indicators per criterion. This method supports an equitable consideration of all aspects of the project. This approach ensures fairness but might dilute critical indicators and emphasize less impactful ones disproportionately. In contrast, Scenario 4 assigns equal weights at the criteria level and distributes these weights equally among the indicators within each criterion. This method notably elevates indicators from criteria with fewer total indicators, such as distance to water bodies (20%) and natural disaster risk (20%), potentially exaggerating their importance relative to others. This strategic emphasis suggests a proactive approach to addressing potential environmental impacts and safety concerns, aligning with broader sustainability goals and risk management strategies.

Figure 7.

Weights of (a) indicators and (b) criteria for scenarios 2, 3, and 4. (Colouring of text in (a) and (b) are used to identify the criteria under which each indicator is grouped, the clockwise order of occurrence of each criterion is the same in both cases).

Conversely, Scenario 2 provides a nuanced distribution reflecting inherent indicator connectivity, reducing extremes but still highlighting influential indicators such as distance to main road (12%) and resource potential (14%). Scenario 3’s equal weighting is most suitable when stakeholders lack consensus on priorities, ensuring neutrality. Scenario 3 offers simplicity and ease of implementation, which can be beneficial during the initial project stages, especially when straightforward decision-making and rapid stakeholder consensus are needed. Scenario 4 might appeal to stakeholders seeking balanced criteria-level representation but risks overstating the importance of indicators in smaller criteria sets. Scenario 2 offers a balanced, data-driven alternative reflecting practical interdependencies, beneficial for informed, nuanced decision-making contexts Scenario 4 is favored in environments where environmental and social compliance is critical, aligning project objectives with stringent regulatory standards and community expectations, thus facilitating smoother project approvals and long-term operational sustainability.

4.2. Potential Stakeholder Perspectives

In selecting appropriate scenarios for site selection in green hydrogen production projects, understanding the varied perspectives of key stakeholders such as project managers, environmental regulators, local community leaders, and investors is crucial [28]. Each stakeholder group has distinct priorities and concerns, significantly influencing their preferences for specific decision-making scenarios.

Project managers, whose primary responsibilities include managing implementation timelines, resource allocation, and operational feasibility [29], would likely prefer Scenario 2. This scenario emphasizes the practical integration of technical, economic, and social factors, enabling project managers to plan accurately, reduce unforeseen disruptions, and enhance overall operational efficiency. The interconnected weighting approach ensures a realistic evaluation of indicators, facilitating smoother project execution.

Investors concerned with short-term economic profitability and rapid market entry might prefer Scenario 1, as it emphasizes high-priority technical criteria and market-driven factors, optimizing returns through targeted site selection. Conversely, investors with longer-term horizons who value sustainable returns, reduced investment risk, and community acceptance would find Scenario 2 more attractive. Its balanced consideration of technical viability, economic infrastructure, and social acceptance reduces exposure to socio-political risks and enhances the investment’s longevity and stability.

For environmental regulators, the primary focus is minimizing projects’ ecological impact and ensuring strict adherence to environmental policies [30]. Scenario 4, which prioritizes environmental and safety criteria significantly, is likely the most aligned with their objectives. This scenario’s proactive approach to incorporating high environmental standards ensures that projects not only meet but potentially exceed regulatory requirements, promoting environmental stewardship and risk mitigation.

Scenario 4 also stands out as the most suitable for local community leaders, who seek to maximize social and economic benefits for their communities while mitigating negative impacts. It equally emphasizes community-oriented factors, including population welfare, workforce development, and infrastructure accessibility, ensuring local socio-economic growth while mitigating resistance from community stakeholders.

While Scenario 2 is particularly suited to the needs of project managers and investors due to its emphasis on technical and economic precision, Scenario 4 is better aligned with the priorities of environmental regulators and local community leaders due to its focus on sustainability and community benefits. Each scenario serves distinct objectives and addresses the specific concerns of different stakeholder groups. The selection of a decision-making scenario in green hydrogen production projects must consider various stakeholders’ diverse and sometimes competing interests. The optimal choice integrates these perspectives, balancing technical precision, regulatory compliance, community integration, and investment security to ensure the project’s success and sustainability. This stakeholder-centric approach aligns the project with broader strategic objectives and enhances its acceptance and viability in complex operational landscapes.

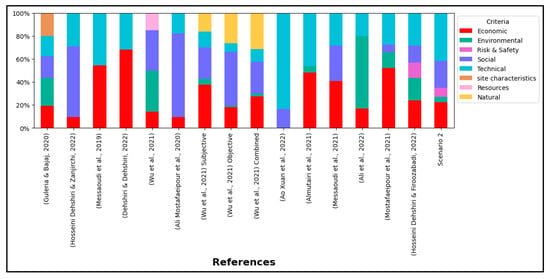

4.3. Comparison with Previous Literature

In the review of 32 studies on site selection criteria for green hydrogen production, only 13 explicitly disclose the weights assigned to various criteria, as in Figure 8. Among them, three have introduced criteria not commonly found in the broader corpus, precisely site characteristics, resources, and natural criteria. Furthermore, categorizing indicators into criteria varies significantly from one study to another. Such variations can be attributed to differences in project focus, regional considerations, or specific research objectives, which influence how the authors group and how experts weigh various factors. Given these differences, the comparison between the findings from these studies and the scenarios outlined in this study should be approached with caution. It is not necessarily an ‘apples to apples’ comparison due to the divergent frameworks and emphasis on different criteria. This highlights the complexity and context-dependent nature of site selection for green hydrogen production facilities, necessitating a nuanced understanding of each study’s strategic focus and methodological choices. Despite not being a fair comparison, it allows meaningful insights to be drawn from the existing body of research.

Only one study [31] aligns with the criteria used in this study, offering a unique opportunity for a more detailed and direct comparison. This congruence allows for examining the methodological approaches and weight allocations that are particularly relevant to enhancing the robustness and applicability of current findings. In a detailed comparison, both studies allocate substantial importance to economic criteria at roughly 20%, although the distribution within this category shows variation. Greater variation can be seen in environmental and risk and safety criteria. This comparison validates methodological choices made in my research and highlights areas of divergence that could be attributed to regional differences, specific project requirements, or evolving stakeholder expectations.

Another study [32] introduces an additional layer of complexity to comparative analysis by employing the CRITIC method for objective indicator weighting. This technique determines the importance of indicators based on both the variability (contrast intensity) and the conflict information (correlation) among the indicators [32]. This methodological approach contrasts with the more subjective or expert-driven weighting methods in many other studies. The technical criteria receive a relatively moderate weight (7.5%), which is considerably lower than the 34% weighting in Scenario 2. This suggests that the CRITIC method may have identified a lower variability or less information gain from technical factors in the dataset used, leading to a lower assigned weight. Similarly, their economic criteria receive an overall weight of 18%, aligning more closely with Scenario 2 at 20%. This alignment might indicate that the economic factors in the datasets used in both studies showed a similar level of variability or informational importance, thereby yielding comparable weights. While the use of the CRITIC method provides a robust, data-centric weighting mechanism, it also illustrates how different approaches can lead to divergent conclusions about the importance of various criteria, depending on the nature and variability of the data. In contexts where data variability is low or where certain criteria are uniformly important across all options, the CRITIC method might undervalue these factors compared to more subjective but contextually attuned methods used in the current study.

In general, a substantial variation in the weights of criteria is observed. A pronounced emphasis on economic factors is evident in several studies, reflecting a primary focus on the financial viability of projects [13,15]. This contrasts with the moderate weighting in Scenario 1 (17%) and a slightly increased emphasis in Scenario 2 (26%). Environmental considerations across the studies fluctuate significantly, ranging from predominant emphasis [14] to not even considering it [13,15,23,33,34,35], possibly reflecting each study’s geographic diversity, distinct regulatory environments, and specific project objectives. It also becomes evident that environmental criteria often receive relatively less emphasis. This observation aligns with broader trends in real-world project implementation, where, despite growing awareness and regulatory pressure, environmental factors may not always be prioritized to the same extent as economic or technical considerations.

In many cases, the relatively lower weighting of environmental criteria reflects the practical challenges and priorities faced during project planning and implementation. While environmental sustainability is a critical aspect of renewable energy projects, the immediate practicalities of economic viability and technical feasibility frequently take precedence in decision-making processes. This prioritization is often driven by the need to ensure project profitability, secure investments, and meet stringent technical requirements necessary for operational success. For instance, studies employing objective methods like the entropy method [32] often result in lower weights for environmental factors, which might indicate less variability or perceived impact of these factors on the project’s overall success compared to economic or technical aspects. This trend of underweighting environmental criteria can be problematic considering global sustainability goals and increasing regulatory demands for lower environmental impact, but reflective of practical realities of project investment. It underscores the need for a more balanced decision-making approach, where environmental sustainability is integrated as a fundamental component rather than an auxiliary consideration. This alignment with real-world practices highlights a gap between theoretical idealism in environmental management and practical implementation constraints, suggesting that more efforts are needed to elevate the role of environmental factors in the decision-making process for green hydrogen projects.

Interestingly, while economic, technical, and social criteria frequently dominate the discussion in site selection for green hydrogen projects, the category of risk and safety is often notably absent in many studies. This omission is significant, considering that risk and safety considerations are pivotal in ensuring energy projects’ secure operation and long-term viability, particularly in industries involving new and potentially disruptive technologies like green hydrogen [36]. The lack of emphasis on risk and safety could be attributed to several factors. Firstly, some studies might implicitly incorporate risk assessments within other criteria, such as technical or economic, rather than addressing them as a standalone category. For instance, aspects like geological faults [37] and faults in power transmission lines [15] can be categorized as economic criteria. However, this approach might obscure the risk and safety challenges prominent in hydrogen production, such as handling highly flammable materials or integrating hydrogen technologies into existing energy systems, which require explicit consideration [38]. Secondly, the absence of a focused risk and safety category could reflect a gap in the existing research methodologies, or a lack of comprehensive industry-specific risk assessment frameworks publicly accessible and standardized across different regions or projects. This lack of standardization can lead to inconsistencies in how risks are assessed and reported, potentially underplaying their importance in project planning and implementation. Furthermore, the omission of dedicated risk and safety considerations in many studies could potentially underrepresent the complexities and challenges associated with green hydrogen projects, leading to oversimplified project evaluations. This simplification might appeal to stakeholders looking to promote the benefits of green hydrogen without fully addressing the potential drawbacks or challenges, which could ultimately impact project success and sustainability.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Scenario 2 with previous literature [13,14,15,17,23,31,32,33,34,35,39,40].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study aimed to develop a decision support system (DSS) for site selection in green hydrogen production, enhancing the framework to support authorities and decision-makers better globally. The comprehensive review of existing literature has revealed a substantial gap in location planning for green hydrogen facilities. Addressing this, the study has developed a robust framework that integrates critical and competing factors to determine optimal locations for leveraging solar and wind resources for hydrogen energy production, which can be used before the optimization model and in the GIS environment. Developing such preparations will help encourage investments in the green hydrogen sector to establish the industry to meet the global demand. Based on the current study, the following conclusions can be made.

- This study distinguishes itself by employing an objective, data-driven approach to minimize human bias in the decision-making process. This approach ensures a more accurate and reliable selection of sites and contributes significantly to the broader adoption of hydrogen energy by providing a clear and quantifiable framework for evaluating potential sites.

- The indicators are designed for more streamlined assessments, focusing on directly applying weighted criteria that reflect economic viability and technical feasibility concerns. These scenarios are particularly useful in contexts where agile decision-making is required, and key factors are well understood and can be straightforwardly quantified. Scenarios 3 and 4, on the other hand, adopt an equalized approach to weighing each criterion and indicator. This is crucial in situations where it is essential to avoid bias towards any single aspect of the project or when a balanced view is necessary to meet the equitable expectations of diverse stakeholder groups.

- The findings indicate that while economic, technical, and sometimes social criteria are predominantly considered in most studies, there is a general underemphasis on environmental criteria and an often-complete omission of risk and safety categories. This reflects the real-world project implementation challenges where immediate practical and economic considerations usually overshadow environmental and safety issues. The proposed framework helps address this imbalance by explicitly integrating environmental and risk and safety considerations.

- Unlike many existing MCDM–GIS approaches that rely heavily on expert elicitation, case-specific criteria, or direct spatial implementation, the proposed framework deliberately focuses on objective, literature-derived indicator selection and weighting as a pre-spatial, first-pass screening tool. By clearly separating indicator filtering, weighting, and scenario analysis from subsequent GIS-based spatial modeling, the framework provides a transparent and reproducible foundation that can be consistently applied across regions before detailed site-level analysis. Future research is recommended to build upon this foundation by integrating the framework with spatially explicit cost models, such as levelized cost of hydrogen and infrastructure cost assessments, as well as optimization and clustering techniques to refine site selection at higher spatial resolution. Coupling the DSS with techno-economic optimization or energy system models would enable a transition from regional prioritization to project-level feasibility assessment, supporting the full decision-making lifecycle.

Site suitability analysis and project evaluation is a feedback loop for continuous improvement [41]. Therefore, stakeholders should establish a feedback loop that informs continuous improvement processes using the above frameworks. Comparing actual outcomes with initial projections allows teams to identify discrepancies and understand their causes, whether due to inaccurate data, changed external conditions, or other factors. This ongoing evaluation supports the refinement of the project and the methodologies used for site selection and impact assessment. The insights gained before implementation and after the power plant is operational are invaluable for adjusting policies and strategies. If the actual data reveals that certain impacts are more significant than initially predicted, adjustments can be made to regulatory frameworks or operational guidelines to address these issues better in future projects.

The proposed framework in this study serves as a theoretical yet practical reference for assessing investment opportunities within the green hydrogen production sector. However, it is important to acknowledge several limitations that could affect the framework’s applicability and effectiveness. Firstly, as green hydrogen production projects are still relatively nascent, the decision support system developed in this study may not be exhaustive. The robustness and accuracy of the system are critically dependent on the quality and availability of data. Effectiveness may be compromised in regions lacking reliable data on environmental, economic, or technical factors. This is particularly pertinent in developing countries or remote areas with underdeveloped data infrastructures. Moreover, the methodology used to determine the criteria weights relies predominantly on an objective approach, predominantly referencing academic literature. This reliance could lead to results that are overly dependent on published studies and may not adequately reflect the subjective perspectives of decision-makers. To ensure relevance and local specificity, it is recommended that the determined index weights be cross-verified with expert and local community opinions. This integration with grey literature could enrich the framework, providing a more comprehensive perspective. On a global basis, the importance of locally specific cultural, regulatory or other governance-related factors may also be lost and is difficult to incorporate as such data is not readily available. The framework does not incorporate legal considerations, which can be crucial in the practical implementation of green hydrogen projects. Including legal assessments could prevent potential regulatory and compliance issues, enhancing the framework’s practical applicability. Addressing these limitations in future iterations of the framework will be essential for improving its utility and ensuring it effectively supports decision-makers in the green hydrogen industry. Moreover, the framework is designed to be coupled with GIS-based spatial optimization models to refine candidate locations and with techno-economic models to estimate levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) once high-priority sites have been identified. Such extensions would allow the DSS to evolve from first-pass screening toward integrated spatial and cost-based decision support, improving its applicability for detailed project planning and investment decision-making.

In future work, the case study used as a demonstration here is expected to be expanded to a global context. Additionally, work should consider the integration and comparison with recent projects and their progress, delay or failure to progress. This should assist in demonstrating the priority sites and hopefully assist in identifying causal factors leading to project delays or closures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/hydrogen7010011/s1, Figure S1: (a) Occurrence of weighting and (b) preference ranking methods in previous literature; Table S1: MCDM Weighing Methods; Table S2: MCDM Ranking Methods; Table S3: Indicators/criteria and their respective occurrence in the previous literature; Table S4: Buffer range for land use constraint from previous literature (Values are in meters); Table S5: Data sources for Australia. The detailed definition of indicators are provided in Supplementary Materials S1 and cited [11,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,25,31,32,33,34,35,37,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. The detailed indicator selections and the justifications are provided in Supplementary Materials S2 and cited [9,11,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,23,25,31,32,33,34,35,37,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,53,54,55,56]. The data sources for case study are provided in Supplementary Materials S2 and cited [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.Z. and B.C.M.; methodology, M.T.Z.; software, M.T.Z.; validation, M.T.Z.; formal analysis, M.T.Z.; data curation, M.T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.T.Z. and B.C.M.; visualization, M.T.Z.; supervision, B.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JST SPRING, Grant Number JPMJSP2110.

Data Availability Statement

Data and codes supporting reported results can be found in the supplementary materials and the GitHub repository (https://github.com/MTZun10/H2site_literature_analysis). All analyses were performed using version v1.0.0 of the repository.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MCDM | Multi-criteria decision-making |

| DSS | Decision support system |

| MT | Million tonnes |

| DM | Decision maker |

| LCOH | Levelized cost of hydrogen |

| GIS | Geographical information system |

References

- Kamei, M.; Wangmo, T.; Leibowicz, B.D.; Nishioka, S. Urbanization, carbon neutrality, and Gross National Happiness: Sustainable development pathways for Bhutan. Cities 2021, 111, 102972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, S.; Wan, W.; Zheng, X.; Chen, C.; Ni, W.; Xu, X.C.; Chen, K. Energy, Environmental and Economic Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrogen Source via Natural Gas Steam Reforming for Fuel Cell Vehicles; Chen, K., Ed.; Tsinghua University: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 405–410. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, A.; Homaee, O.; Jasinski, M.; Tsaousoglou, G.; Leonowicz, Z. Integrating hydrogen technology into active distribution networks: The case of private hydrogen refueling stations. Energy 2023, 278, 127939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreyer, F.; Ueckerdt, F.; Pietzcker, R.; Rodrigues, R.; Rottoli, M.; Madeddu, S.; Pehl, M.; Hasse, R.; Luderer, G. Distinct roles of direct and indirect electrification in pathways to a renewables-dominated European energy system. One Earth 2024, 7, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebreich Associates. The Clean Hydrogen Ladder; Liebreich Associates: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://liebreich.com/the-clean-hydrogen-ladder-now-updated-to-v4-1/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- IEA. Hydrogen Demand—Global Hydrogen Review 2024—Analysis; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2024/hydrogen-demand (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Wappler, M.; Unguder, D.; Lu, X.; Ohlmeyer, H.; Teschke, H.; Lueke, W. Building the green hydrogen market—Current state and outlook on green hydrogen demand and electrolyzer manufacturing. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 33551–33570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odenweller, A.; Ueckerdt, F. The green hydrogen ambition and implementation gap. Nat. Energy 2025, 10, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingason, H.T.; Pall Ingolfsson, H.; Jensson, P. Optimizing site selection for hydrogen production in Iceland. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 3632–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zun, M.T.; McLellan, B.C. Cost Projection of Global Green Hydrogen Production Scenarios. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 932–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; He, F.; Zhou, J.; Wu, C.; Liu, F.; Tao, Y.; Xu, C. Optimal site selection for distributed wind power coupled hydrogen storage project using a geographical information system based multi-criteria decision-making approach: A case in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 299, 126905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna, S.; Gerres, T.; Cossent, R. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making for Renewable Hydrogen Production Site Selection: A Systematic Literature Review. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, D.; Settou, N.; Negrou, B.; Settou, B. GIS based multi-criteria decision making for solar hydrogen production sites selection in Algeria. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 31808–31831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Bennui, A.; Chowdhury, S.; Techato, K. Suitable Site Selection for Solar-Based Green Hydrogen in Southern Thailand Using GIS-MCDM Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehshiri, S.; Dehshiri, S. Locating wind farm for power and hydrogen production based on Geographic information system and multi-criteria decision making method: An application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 24569–24583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Gao, J.; Liu, H.; He, P. A hybrid fuzzy investment assessment framework for offshore wind-photovoltaic-hydrogen storage project. J. Energy Storage 2022, 45, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleria, A.; Bajaj, R.K. A robust decision making approach for hydrogen power plant site selection utilizing (R, S)-Norm Pythagorean Fuzzy information measures based on VIKOR and TOPSIS method. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 18802–18816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Alharbi, S.; Razmjoo, A.; Mohamed, M. Accurate location planning for a wind-powered hydrogen refueling station: Fuzzy VIKOR method. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 33360–33374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhou, J.; He, F.; Xu, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, T. An investment decision framework for photovoltaic power coupling hydrogen storage project based on a mixed evaluation method under intuitionistic fuzzy environment. J. Energy Storage 2020, 30, 101601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, N.Y.; Kentel, E.; Duzgun, S. GIS-based environmental assessment of wind energy systems for spatial planning: A case study from Western Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, M.; Shamsabadi, A.A.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Rezaei, M.; Yousefi, Y.; Pomares, L.M. Using fuzzy MCDM technique to find the best location in Qatar for exploiting wind and solar energy to generate hydrogen and electricity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 13862–13875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, N.; Wei, L.; Zhang, Z. Optimal site selection study of wind-photovoltaic-shared energy storage power stations based on GIS and multi-criteria decision making: A two-stage framework. Renew. Energy 2022, 201, 1139–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao Xuan, H.; Vu Trinh, V.; Techato, K.; Phoungthong, K. Use of hybrid MCDM methods for site location of solar-powered hydrogen production plants in Uzbekistan. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfasfos, R.; Sillman, J.; Soukka, R. Lessons learned and recommendations from analysis of hydrogen incidents and accidents to support risk assessment for the hydrogen economy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 60, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Khalilpour, K.R.; Jahangiri, M. Multi-criteria location identification for wind/solar based hydrogen generation: The case of capital cities of a developing country. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 33151–33168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, L.; Bussar, C.; Stoecker, P.; Jacqué, K.; Chang, M.; Sauer, D.U. Comparison of long-term wind and photovoltaic power capacity factor datasets with open-license. Appl. Energy 2018, 225, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, S.; Page, L. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine. Comput. Netw. ISDN Syst. 1998, 30, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagac, J. Stakeholder Engagement in Project Management: A Comprehensive Guide; Boréalis: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://www.boreal-is.com/blog/stakeholder-engagement-in-project-management/ (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Korhonen, T.; Jääskeläinen, A.; Laine, T.; Saukkonen, N. How performance measurement can support achieving success in project-based operations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2023, 41, 102429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tham, J. The impact of environmental regulation, Environment, Social and Government Performance, and technological innovation on enterprise resilience under a green recovery. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Dehshiri, S.S.; Firoozabadi, B. A new application of measurement of alternatives and ranking according to compromise solution (MARCOS) in solar site location for electricity and hydrogen production: A case study in the southern climate of Iran. Energy 2022, 261, 125376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Tao, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, F.; Zhou, J. Site selection decision framework for photovoltaic hydrogen production project using BWM-CRITIC-MABAC: A case study in Zhangjiakou. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Dehshiri, S.J.; Zanjirchi, S.M. Comparative analysis of multicriteria decision-making approaches for evaluation hydrogen projects development from wind energy. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 13356–13376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaeipour, A.; Dehshiri, S.J.H.; Dehshiri, S.S.H. Ranking locations for producing hydrogen using geothermal energy in Afghanistan. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 15924–15940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, D.; Settou, N.; Negrou, B.; Settou, B.; Mokhtara, C.; Amine, C.M. Suitable Sites for Wind Hydrogen Production Based on GIS-MCDM Method in Algeria. In Advances in Renewable Hydrogen and Other Sustainable Energy Carriers; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, O.R. Hydrogen infrastructure—Efficient risk assessment and design optimization approach to ensure safe and practical solutions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 143, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Shi, Y.; Maleki, A.; A Rosen, M. Optimal location and size of a grid-independent solar/hydrogen system for rural areas using an efficient heuristic approach. Renew. Energy 2020, 156, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, M.; Portarapillo, M.; Di Nardo, A.; Venezia, V.; Turco, M.; Luciani, G.; Di Benedetto, A. Hydrogen Safety Challenges: A Comprehensive Review on Production, Storage, Transport, Utilization, and CFD-Based Consequence and Risk Assessment. Energies 2024, 17, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K.; Hosseini Dehshiri, S.S.; Hosseini Dehshiri, S.J.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Jahangiri, M.; Techato, K. Technical, economic, carbon footprint assessment, and prioritizing stations for hydrogen production using wind energy: A case study. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 36, 100684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaeipour, A.; Rezayat, H.; Rezaei, M. A thorough analysis of renewable hydrogen projects development in Uzbekistan using MCDM methods. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 31174–31190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifino, P. Feedback Loop: The Art of Continuous Improvement. Easy Feedback. Available online: https://easy-feedback.com/blog/feedback-loop-explained/ (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Gao, J.; Men, H.; Guo, F.; Liang, P.; Fan, Y. A multi-criteria decision-making framework for the location of photovoltaic power coupling hydrogen storage projects. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K. Determining the appropriate location for renewable hydrogen development using multi-criteria decision-making approaches. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 5876–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaeipour, A.; Dehshiri, S.J.H.; Dehshiri, S.S.H.; Jahangiri, M. Prioritization of potential locations for harnessing wind energy to produce hydrogen in Afghanistan. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 33169–33184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaeipour, A.; Rezayat, H.; Rezaei, M. A thorough investigation of solar-powered hydrogen potential and accurate location planning for big cities: A case study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 31599–31611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaeipour, A.; Sedaghat, A.; Qolipour, M.; Rezaei, M.; Arabnia, H.R.; Saidi-Mehrabad, M.; Shamshirband, S.; Alavi, O. Localization of solar-hydrogen power plants in the province of Kerman, Iran. Adv. Energy Res. 2017, 5, 179–205. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, M.; Qolipour, M.; Golmohammadi, A.-M.; Hadian, H. Using MCDM approaches to rank different locations for harnessing wind energy to produce hydrogen. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Bandung, Indonesia, 6–8 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shouroki, M.R.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Qolipour, M. Prioritizing of wind farm locations for hydrogen production: A case study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 9500–9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.H.; Hosseini Dehshiri, S.S.; Hosseini Dehshiri, S.J.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Almutairi, K.; Ao, H.X.; Rezaei, M.; Techato, K. A Thorough Economic Evaluation by Implementing Solar/Wind Energies for Hydrogen Production: A Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K.; Hosseini Dehshiri, S.S.; Hosseini Dehshiri, S.J.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Issakhov, A.; Techato, K. A thorough investigation for development of hydrogen projects from wind energy: A case study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 18795–18815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.; Campbell, C.; Denholm, P.; Margolis, R.; Heath, G. Land-Use Requirements for Solar Power Plants in the United States; Office of Scientific and Technical Information (OSTI): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Tao, Y.; Liu, F. Optimal sites selection of oil-hydrogen combined stations considering the diversity of hydrogen sources. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 1043–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaeipour, A.; Qolipour, M.; Goudarzi, H. Feasibility of using wind turbines for renewable hydrogen production in Firuzkuh, Iran. Front. Energy 2019, 13, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karipoğlu, F.; Serdar Genç, M.; Akarsu, B. GIS-based optimal site selection for the solar-powered hydrogen fuel charge stations. Fuel 2022, 324, 124626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, M.; Rezaei, M.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Goojani, A.R.; Saghaei, H.; Hosseini Dehshiri, S.J.; Dehshiri, S.S.H. Prioritization of solar electricity and hydrogen co-production stations considering PV losses and different types of solar trackers: A TOPSIS approach. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 889–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, D.; Settou, N.; Negrou, B.; Rahmouni, S.; Settou, B.; Mayou, I. Site selection methodology for the wind-powered hydrogen refueling station based on AHP-GIS in Adrar, Algeria. Energy Procedia 2019, 162, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.N.; Badger, J.; Hahmann, A.N.; Hansen, B.O.; Mortensen, N.G.; Kelly, M.; Larsén, X.G.; Olsen, B.T.; Floors, R.; Lizcano, G.; et al. The Global Wind Atlas: A High-Resolution Dataset of Climatologies and Associated Web-Based Application. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E1507–E1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. Available online: https://planet.osm.org (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- GEBCO Compilation Group. The GEBCO_2024 Grid|GEBCO. Available online: https://www.gebco.net/data-products-gridded-bathymetry-data/gebco2024-grid (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- NASA Geocoded Disasters (GDIS) Dataset. Available online: https://data.nasa.gov/dataset/geocoded-disasters-gdis-dataset (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Physical Sciences Laboratory. CMAP Precipitation: NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory CMAP Precipitation. Available online: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cmap.html (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- HDX World—Population Counts. Available online: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/worldpop-population-counts-for-world (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory. NCEP/DOE Reanalysis II. Available online: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis2.html (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Global Solar Atlas. Global Horizontal Solar Irradiation. Available online: https://globalsolaratlas.info/download (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- World Bank. Derived Map of Global Electricity Transmission and Distribution Lines. Available online: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0038055/Derived-map-of-global-electricity-transmission-and-distribution-lines (accessed on 3 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.