Abstract

This study addresses the growing need for effective energy management solutions in university settings, with particular emphasis on solar–hydrogen systems. The study’s purpose is to explore the integration of deep learning models, specifically MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3, in enhancing fault detection capabilities in AIoT-based environments, while also customizing ISO 50001:2018 standards to align with the unique energy management needs of academic institutions. Our research employs comparative analysis of the two deep learning models in terms of their performance in detecting solar panel defects and assessing accuracy, loss values, and computational efficiency. The findings reveal that MobileNetV2 achieves 80% accuracy, making it suitable for resource-constrained environments, while InceptionV3 demonstrates superior accuracy of 90% but requires more computational resources. The study concludes that both models offer distinct advantages based on application scenarios, emphasizing the importance of balancing accuracy and efficiency when selecting appropriate models for solar–hydrogen system management. This research highlights the critical role of continuous improvement and leadership commitment in the successful implementation of energy management standards in universities.

1. Introduction

The energy industry worldwide is going through a substantial transformation due to the necessity of tackling issues related to climate change and energy security. As societies confront the constraints of fossil fuel resources and their impact on the environment, the shift to renewable energy sources has become more than just a strategic choice—it is now a crucial necessity. Solar power is distinguished among renewable energy sources for its plentifulness, adaptability, and rapidly decreasing cost. Utilizing solar power in energy grids has the potential to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate the effects of climate change, offering a sustainable solution to the world’s energy needs [1,2,3,4].

Solar–hydrogen systems have the capability to maximize the utilization of solar energy. By using PVs (Photovoltaics) cells to transform sunlight into electricity, these systems can produce hydrogen through electrolysis, a process that separates water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity. This hydrogen can be stored and utilized as a clean energy source, addressing the issue of unreliability in renewable energy [5,6,7,8]. Solar power generation is naturally unpredictable, relying on elements like the time of day, weather patterns, and seasonal fluctuations. Hydrogen serves as a buffer, allowing for the storage of extra solar energy to be used at a later time when production does not match consumption. This dual-purpose capability enhances energy reliability and provides a sustainable method for reducing reliance on fossil fuels [9,10].

Although solar–hydrogen systems offer many benefits, effectively running them poses significant obstacles. Various factors such as environmental conditions, system design, and operational strategies impact the performance of these systems. Changes in energy requirements and availability lead to complications that call for advanced energy management techniques [11,12,13]. Conventional methods of energy management frequently fail to adequately handle these intricate issues, especially in time-sensitive situations that require quick decision-making. Therefore, it is crucial to develop innovative methods that can merge the capabilities of real-time data analysis and forecasting to improve the effectiveness and reliability of solar–hydrogen systems [14,15,16,17]. In recent times, there has been substantial advancement in artificial intelligence, particularly with regard to deep learning, which has proven to be a valuable tool for addressing these challenges [18,19,20,21]. MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3, among other deep learning algorithms, have shown outstanding results in different fields like image categorization and in predicting time series. These models excel at handling large datasets and understanding intricate patterns, making them ideal for use in renewable energy systems. By utilizing these models, we can utilize the extensive datasets produced by solar–hydrogen systems to forecast energy needs, improve operational efficiency, and boost system reliability as a whole [22,23,24,25].

The transition to renewable energy sources is a critical component of addressing global energy challenges, particularly in the context of climate change and sustainability. However, this transition is fraught with numerous challenges, especially in the integration and management of variable renewable energy (VRE) sources such as solar and wind power. Deep learning (DL) and other advanced machine learning techniques have shown significant promise in addressing these challenges by improving forecasting accuracy, optimizing energy management, and enhancing system reliability. The integration of renewable energy sources into existing power grids presents several challenges, including the intermittent and unpredictable nature of these energy sources. For instance, solar and wind energy generation can vary significantly due to weather conditions, making it difficult to maintain a stable and reliable power supply. Additionally, the complexity of managing energy flows increases with the integration of multiple renewable sources, necessitating advanced control and optimization techniques [26,27].

Deep learning has emerged as a powerful tool for addressing the complexities of renewable energy management. Various DL-based approaches have been developed to improve the forecasting of solar and wind energy generation, system scheduling, and grid management. For example, deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has been applied to optimize the control policies for renewable power systems, demonstrating significant improvements in performance and cost reduction. Moreover, hybrid DL techniques, which combine multiple learning methods, have shown superior performance in handling large datasets and improving prediction accuracy [28,29].

Quantitative data are essential to support the transition to renewable energy, particularly when demonstrating the effectiveness of DL applications. Studies have shown that DL techniques can achieve up to 20% performance improvement in energy management tasks compared to traditional methods [30]. In the context of solar–hydrogen systems, DL-driven optimization has been shown to reduce operational costs by up to 89.1% compared to conventional battery energy storage systems [31]. These data points underscore the potential of DL in enhancing the efficiency and reliability of renewable energy systems.

The implementation of ISO 50001:2018, an international standard for energy management systems, in universities can lead to significant energy savings and operational efficiencies. Case studies from various universities have demonstrated the quantifiable benefits of adopting this standard. For instance, universities that have implemented ISO 50001:2018 have reported energy savings of up to 15% and a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions [32]. These case studies highlight the practical benefits and the importance of adopting standardized energy management practices in educational institutions.

The selection of specific deep learning models, such as MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3, requires a strong justification based on comparative analysis with other available models. MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 are known for their efficiency and accuracy in handling large-scale image data, making them suitable for applications in energy management where high-resolution data from sensors and imaging devices are used [33,34]. Comparative studies have shown that these models outperform other architectures in terms of computational efficiency and prediction accuracy, making them ideal choices for real-time energy management applications [35].

This research is motivated by both the necessity for enhanced energy management in solar–hydrogen systems and the possibility of deep learning techniques offering new solutions. Incorporating cutting-edge deep learning techniques into existing energy management systems like ISO 50001:2018 can provide a chance to develop a more effective and resilient operational model. ISO 50001:2018 offers a thorough structure for EnMS, emphasizing systematic methods to enhance energy efficiency and lower consumption [36,37,38,39]. By combining deep learning abilities with the guidelines specified in ISO 50001:2018, we can guarantee that energy management procedures are both effective and environmentally friendly. One primary objective of this study is to evaluate how MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 can enhance the effectiveness of solar–hydrogen systems. This evaluation involves assessing the models’ capability to forecast energy use, identify operational problems, and enhance strategic operations instantly. MobileNetV2 is created for mobile and embedded vision tasks, providing a compact design for fast processing and effective use of resources. On the other hand, InceptionV3, which is known for its intricate design, outperforms it in terms of precision and is especially efficient when dealing with substantial amounts of data. Our goal is to determine the most efficient methods for incorporating deep learning into the management of solar–hydrogen systems by comparing the performances of different models.

This study aims to explore how ISO 50001:2018 can help improve energy management in solar–hydrogen systems, in addition to assessing deep learning models. ISO 50001 stresses the significance of setting up a structured system to monitor and enhance energy efficiency. It offers a methodical strategy involving identifying EnPIs, conducting audits, and ongoing improvement processes. By incorporating deep learning models into this system, we can improve the decision-making process, enabling quicker reactions to changing energy needs and environmental situations.

An important part of our study involves presenting a thorough integration framework that merges deep learning techniques with the concepts of ISO 50001:2018. This framework aims to make the exchange of data between energy management processes and machine learning models smoother, ultimately boosting the overall efficiency and sustainability of solar–hydrogen systems. Through establishing a loop of feedback in which current data influence predictive models, and the predictions help to inform energy management choices, we can enhance the efficiency of these systems in a flexible way. The goals of this study can be outlined as follows:

- Assess the efficiency of MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 in predicting energy needs and detecting irregularities in solar–hydrogen systems. This will require comparing model performance in terms of accuracy, processing speed, and applicability for real-time use.

- Study energy-management guidelines: Explore the impact of ISO 50001:2018 on energy-management methods in solar–hydrogen systems. This involves evaluating how the standard can be successfully combined with machine learning strategies to improve energy efficiency.

- Suggest an Integrated Framework: Create a thorough framework that merges deep learning techniques with ISO 50001:2018 guidelines to enhance the operational efficiency of solar–hydrogen systems. This structure will prioritize creating a feedback system that uses up-to-date information to guide decision-making processes.

- Encourage sustainability: Emphasize the opportunity for this holistic method to support wider sustainability objectives, illustrating how smart energy management can result in lower carbon emissions and enhanced resource efficiency.

This research seeks to tackle the difficulties encountered by solar–hydrogen systems by connecting advanced machine-learning methods with established energy management frameworks [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. This study leverages open-source AI architectures, specifically MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3, as core components of the proposed fault detection system. The use of open-source models offers several advantages, including accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and reproducibility. These models allow for easy replication and adaptation by other researchers and institutions without the constraints of licensing fees, supporting the development of scalable and widely applicable solutions. By emphasizing open-source tools, our approach promotes transparency and fosters collaboration in the field, facilitating advancements in solar panel fault detection and sustainable energy management. Combining MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 with ISO 50001:2018 provides a distinct chance to develop more intelligent, effective renewable energy setups.

AI refers to the simulation of human intelligence in machines, enabling them to perform tasks such as learning, reasoning, and problem-solving. On the other hand, AIoT represents the integration of AI (artificial intelligence) technologies with the Internet of Things (IoT), where interconnected devices utilize AI (artificial intelligence) capabilities to analyze data and make intelligent decisions in real time. This distinction is crucial, as it underscores how AI (artificial intelligence) serves as the foundational technology that empowers IoT devices to operate more autonomously and efficiently. By elaborating on this differentiation, we aim to provide a clearer understanding of the roles of both AI (artificial intelligence) and AIoT (artificial intelligence of things) in our research, particularly in the context of advancing solar panel fault detection and management.

This research aims to offer knowledge that can encourage more widespread use of similar integrated methods in the renewable energy industry, thus promoting a more sustainable energy future. Embracing new solutions that utilize advanced technologies will be crucial in achieving sustainability goals as the world faces the challenges of the energy transition. The combination of deep learning and energy management guidelines offers an effective way to improve solar–hydrogen systems, improve their performance, and support global initiatives to address climate change. This study seeks to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of renewable energy solutions by improving the performance of solar–hydrogen systems and encouraging further exploration of the technology’s potential.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Solar–Hydrogen Systems

Solar–hydrogen systems (Table 1) provide a fresh method for fulfilling the growing demand for sustainable energy sources. These systems utilize solar power to produce hydrogen, which serves as a clean source of fuel and as an energy carrier. Solar–hydrogen systems utilize PV technology to produce electricity from sunlight, which powers an electrolyzer that splits water into hydrogen and oxygen through electrolysis. This method provides a means of storing energy and utilizing excess solar energy during peak production [48,49,50].

Table 1.

Key components of solar–hydrogen system.

Combining solar energy with hydrogen production has numerous benefits. One of the major advantages is the capability to save energy produced during sunny times for later use when solar output is limited, like in the evening or on overcast days. This characteristic boosts energy dependability and renders solar–hydrogen systems especially beneficial in areas with ample solar resources [51,52]. Furthermore, renewable sources have the potential to produce hydrogen for the purpose of decarbonizing sectors such as heavy transportation and industrial processes that are challenging to electrify [53,54,55].

Technological advancements are providing support for the creation and integration of solar–hydrogen systems (Table 2). Studies have concentrated on increasing the effectiveness of solar cells and electrolyzers, crucial for improving the system’s overall efficiency. As an illustration, advancements in tandem solar cell technology, which combine various materials to capture a wider range of sunlight, have the possibility to boost energy conversion efficiencies beyond what can be achieved by traditional silicon-based cells [56,57,58]. In the same way, improvements in electrolyzer technology like PEM (Polymer Electrolyte Membrane) electrolyzers and alkaline electrolyzers are leading to increased efficiencies and decreased operational expenses. Although solar–hydrogen systems show great promise, there are still obstacles that may prevent their extensive use. A major concern is the significant initial investment required for solar panels, electrolyzers, and hydrogen storage technologies due to their high capital cost. Furthermore, efficient energy management strategies are required to align hydrogen production with energy demand due to the on-and-off nature of solar energy generation. To tackle these obstacles, a multifaceted strategy involving engineering, economics, and policy factors is necessary [59,60,61].

Table 2.

Advantages and challenges of solar–hydrogen systems.

Lately, extensive research (Table 3) has been performed to examine the possibilities of solar–hydrogen systems in different applications, from small residential systems to big industrial installations. Research has indicated that integrating solar energy with hydrogen production can greatly decrease greenhouse gas emissions, aiding in achieving both national and international climate objectives [62,63,64,65,66]. Moreover, there is a growing emphasis on combining solar–hydrogen systems with wind power and other renewable energy sources in research, aiming to develop hybrid systems that maximize energy production and efficiency. The importance of energy management frameworks like ISO 50001:2018 is gaining increasing acknowledgement within the realm of solar–hydrogen systems. These guidelines offer a structured approach for organizations to enhance their energy efficiency, which is essential for managing solar–hydrogen systems effectively. Incorporating energy management standards with advanced predictive models, especially those utilizing deep learning, can improve the efficiency and reliability of these systems even more [67,68,69,70,71,72].

Table 3.

Research focus areas in solar–hydrogen systems.

Solar–hydrogen systems offer an attractive answer for the future of energy, merging the benefits of solar power with the flexibility of hydrogen. Continued research and development are essential for addressing current challenges and unlocking the complete capabilities of these systems, despite notable progress being achieved. As the need for sustainable energy sources increases, the use of solar and hydrogen technologies will become more important in the worldwide shift towards renewable energy [73,74,75,76,77].

Recent studies provide crucial insights into advancements in green hydrogen storage, generation, and production technologies that are essential for a sustainable future. Using green hydrogen as a renewable energy carrier addresses the intermittency of renewable sources. Large-scale storage and transportation methods have been reviewed, including compressed and liquid hydrogen, pipeline blending, and ammonia-based carriers. While costs associated with hydrogen storage and transport are expected to decrease through technological improvements and economies of scale, challenges remain. The study emphasizes the need for thorough assessments of storage solutions, such as salt caverns and pipelines, to facilitate a robust hydrogen industry [78]. In parallel, a Digital Replica (DR) model of a Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer (PEMEL) as a tool for optimizing hydrogen storage systems. Using an Equivalent Circuit Model (ECM) to capture the static behaviors of PEM cells, the model accurately simulates key parameters like current, voltage, and hydrogen flow through a Data Acquisition System (DAQ). Experimental data confirm the DR model’s efficacy, making it a valuable asset in modeling PEMEL performance under varying conditions and advancing efficient hydrogen storage applications [79]. Further emphasis is placed on green hydrogen production technologies, focusing on the “color codes” of hydrogen and highlighting green hydrogen derived from renewable sources as particularly promising. Recent technological advancements have made green hydrogen increasingly competitive with fossil-derived blue hydrogen. The review identifies solid oxide electrolysis cells (SOECs) as a leading technology, along with promising alternatives like anion exchange membranes (AEMs) and electrified steam methane reforming (ESMR). Global progress in hydrogen infrastructure and policies has also been reviewed, offering valuable insights into the evolving hydrogen energy landscape [80].

2.2. Deep Learning in Energy Systems

Deep learning has become a game-changing technology in different fields, such as energy systems. Deep learning models can assess extensive datasets, detect patterns, and predict outcomes essential for successful energy management through intricate neural network structures. Two well-known models in this area are MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3, both of which have exhibited significant potential for tasks like time-series forecasting, anomaly detection, and real-time monitoring in energy systems. Their effectiveness and capabilities make them very appropriate for integration into renewable energy uses, such as solar–hydrogen systems [81,82,83,84,85].

2.2.1. MobileNetV2

MobileNetV2 (Table 4) is a compact convolutional neural network (CNN) developed for mobile and embedded vision tasks. It expands on the groundwork laid by MobileNetV1, incorporating various upgrades to enhance its effectiveness and efficiency [86,87,88,89,90]. The main advancements in MobileNetV2 are listed below.

Table 4.

Key Features of MobileNetV2.

- Depthwise separable convolutions involve dividing the convolution process into two steps: first, a depthwise convolution, then, a pointwise convolution. This decreases both the computational complexity and parameter count, resulting in a lighter and faster model without sacrificing accuracy.

- Linear bottlenecks are integrated into the design of MobileNetV2 to preserve crucial information while it moves through the network. This function is especially useful for activities that demand precise information, like predicting energy levels and identifying abnormalities.

- Flexibility and Scalability: MobileNetV2 can be scaled in width and resolution to accommodate different hardware limitations and application requirements. This flexibility makes it perfect for use in real-time energy monitoring systems with possible restrictions on computational resources.

The primary focus of applying MobileNetV2 in energy systems is on real-time data analysis and predictive modeling. For example, it has the capability to forecast energy requirements by examining past usage trends and factors like temperature and solar radiation. Furthermore, the system’s capability to pinpoint irregularities in energy consumption can assist in recognizing possible problems in solar–hydrogen systems, enabling prompt actions and upkeep.

2.2.2. InceptionV3

InceptionV3 (Table 5) is a deep neural network designed to achieve superior performance in tasks involving image classification. It enhances the performance and decreases computational requirements by making various improvements to the Inception architecture [91,92,93,94,95]. Important features of InceptionV3 are listed below.

Table 5.

Key features of InceptionV3.

- Modules of Inception: These modules enable the network to conduct convolutions of various sizes simultaneously, allowing it to gather a range of features at different scales. This method of extracting features at different scales is very beneficial for the intricate data often found in energy systems.

- InceptionV3 includes additional classifiers to address the issue of vanishing gradient in training. These secondary networks offer extra gradient signals, which help to improve the learning process of deep representations.

- Methods like dropout and batch normalization are used in the architecture to avoid overfitting and enhance generalization, both of which are crucial when handling various energy data.

Within energy systems, InceptionV3 can be efficiently used for intricate predictive modeling duties. Its capacity to analyze time-series data makes it appropriate for predicting solar panel energy generation, forecasting energy storage requirements, and optimizing energy distribution. InceptionV3 can improve the operational efficiency of solar–hydrogen systems by analyzing both historical data and real-time inputs to offer actionable insights (Table 6).

Table 6.

Applications of deep learning models using InceptionV3 and MobileNetV2 in energy systems.

2.3. ISO 50001:2018

ISO 50001:2018 is an internationally recognized standard developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) that provides guidance on developing, implementing, preserving, and continually improving an energy management system (EnMS) within enterprises [96].

The main goal of ISO 50001:2018 is to assist organizations in increasing their energy efficiency, reducing their energy consumption, and lowering their energy costs while advancing environmental sustainability. Regardless of an organization’s location, industry, or amount of energy use, the standard applies to businesses of all shapes and sizes. With the adaptable framework provided by ISO 50001:2018, companies can address energy management methodically and efficiently, regardless of their unique demands and circumstances [97]. The foundation of ISO 50001:2018, Key Principles and Requirements [98,99], is a set of essential guidelines and standards that enterprises must follow to accomplish successful energy management (Table 7).

Table 7.

Key principles and requirements for ISO 50001:2018.

The energy management system (EnMS) standard ISO 50001:2018 is closely linked to several other ISO standards that address various facets of organizational management and sustainability. Table 8 displays some of the most pertinent ISO standards [100,101,102,103,104].

Table 8.

Relevant ISO standards related to ISO 50001:2018.

Organizations are given a comprehensive framework for managing quality, environmental performance, occupational health and safety, social responsibility, and energy efficiency when these ISO standards are combined and put into practice. Organizations can demonstrate their commitment to sustainability and ethical business practices, improve operational efficiency, and strengthen their overall management systems by aligning with these standards [105].

2.3.1. ISO 50001:2018 in Higher Education

The use of ISO 50001:2018 in higher education provides an organized method for effectively managing energy resources, which aligns with the institutions’ increasing focus on environmental responsibility and sustainability. Universities and colleges can systematically identify and prioritize opportunities for energy conservation, lowering operating costs and carbon footprints, through the installation of an ISO 50001-based Energy Management System (EnMS). This guideline encourages the development of energy policy, senior management participation, and the incorporation of energy management into administrative and instructional procedures. By putting sustainability ideals into practice, educational institutions can also save money that could be used for more academic endeavors and give students real-world examples of responsible resource management. Moreover, ISO 50001’s continuous improvement component fosters a higher education sector culture of continuous environmental awareness and operational efficiency. Higher education institutions can benefit from implementing ISO 50001:2018 in several ways because they frequently have large campuses, buildings, and energy use. This guide (Table 9) explains how to connect the higher education sector to the implementation of ISO 50001 [106,107,108].

Table 9.

Implementation of ISO 50001 to higher education.

2.3.2. Relevance of ISO 50001:2018 to Solar–Hydrogen Systems in Universities

The applicability of ISO 50001:2018 to solar–hydrogen systems in higher education can be attributed to its capacity to offer an all-encompassing structure for efficient energy resource management, which is consistent with the increasing focus on sustainability and renewable energy programs in academic settings. ISO 50001 encourages universities to implement and maintain an Energy Management System (EnMS), which facilitates a systematic approach to energy conservation and efficiency. Regarding solar–hydrogen systems, ISO 50001 can assist academic institutions in maximizing the integration and functionality of these renewable energy sources. The ISO 50001:2018 standard offers a thorough framework for the effective and sustainable management of energy resources, making it extremely pertinent to solar–hydrogen systems in academic settings. Table 10 provides various essential features that might be used to elaborate on the relevance [109,110].

Table 10.

Several key aspects.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. System Architecture Design

The architectural design centers on using two advanced deep learning models: MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3. These designs were chosen for their effectiveness in completing tasks related to both constrained devices and image classification at a large scale. The system was designed to evaluate and control the energy flow in a solar–hydrogen system, with these models carrying out important functions like recognizing energy patterns and detecting faults.

- InceptionV3 Model: The MobileNetV2 model is optimized for use with low-power devices, allowing for effective real-time energy management in a solar–hydrogen system. This model employs depthwise separable convolutions in order to decrease computational expenses while still achieving high precision. The article outlines the structure of the model, emphasizing its ability to extract features, and justifies why its efficient design is perfect for this use.

- MobileNetV2 Model: Meanwhile, InceptionV3 is selected for its superior ability to manage complicated image identification assignments using limited computational power. The model makes use of various filter sizes in its design to capture varied levels of data, which is essential for spotting irregularities and improving energy efficiency in solar–hydrogen systems. The strong feature extraction and efficient computation of this model make it suitable for analyzing large energy datasets.

3.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

Extensive data collection and preprocessing were conducted to guarantee the optimal functioning of the models. The dataset includes information on energy usage, environmental factors like solar radiation and temperature, and past records of system malfunctions.

- Dataset Description: The dataset consists of time-series information gathered from different sensors integrated into the solar–hydrogen system. The data encompass key metrics such as energy production and consumption, hydrogen storage levels, and environmental factors. This information is crucial for teaching deep learning algorithms to identify defects and enhance energy allocation in the system. The dataset comprises time-series information collected from multiple sensors within the solar–hydrogen system, including the following details:

- Energy production and consumption metrics.

- Hydrogen storage levels.

- Environmental parameters (solar radiation, temperature).

- System fault history.

- Operational status indicators.

- Data Augmentation and Transformation: Data preprocessing included cleaning, normalizing, and augmenting methods to improve the diversity and quality of the training dataset. As the system functions in changing environments, where energy generation may fluctuate because of weather conditions, data augmentation methods like time-shifting and noise insertion were used. Utilizing these methods enhanced the model’s resilience by replicating various actual energy situations, guaranteeing better generalization to new data. Data preprocessing implementation includes the following steps:

- Cleaning Procedures

- -

- Missing value imputation using time-series-specific methods.

- -

- Outlier detection using statistical and domain-specific rules.

- -

- Noise reduction through moving average filters.

- Normalization Techniques

- -

- Min–max scaling for sensor data.

- -

- Z-score normalization for environmental parameters.

- -

- Time-series specific normalization for seasonal adjustments.

- Augmentation Methods

- -

- Time-shifting for temporal pattern enhancement.

- -

- Noise insertion for robustness.

- -

- Synthetic sample generation for rare fault conditions.

3.3. Training and Optimization of the Deep Learning Models

Following data preprocessing, the MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 models were trained to identify patterns and abnormalities in the energy data of the system. The training was adjusted to guarantee the best performance.

- Model Training Techniques: The training utilized backpropagation with stochastic gradient descent (SGD) as the optimizer to ensure quick convergence. The models were sequentially fed input data, with weights being updated according to the error produced. Moreover, cross-validation was implemented to guarantee the models would perform well on new data, avoiding overfitting and enhancing dependability. This included the following steps:

- Implementation of stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer.

- Batch processing with dynamic batch size adjustment.

- Cross-validation implementation (k = 5).

- Early stopping criteria based on validation loss.

- Hyperparameter Tuning and Regularization: Extensive tuning of hyperparameters was carried out to achieve optimal model performance. Techniques like grid and random search were used to systematically adjust parameters such as the learning rate, batch size, and the number of layers. Furthermore, techniques like dropout and L2 regularization were employed to avoid overfitting and guarantee optimal performance of the models in different energy scenarios. Employing these techniques, in conjunction with implementing early termination during the training process, contributed to enhancing the effectiveness and precision of the models in controlling energy in the solar–hydrogen system:

- Grid search optimization for key parameters.

- Random search for architectural variations.

- Bayesian optimization for fine-tuning.

- Learning rate scheduling with warm-up period.

3.4. ISO 50001:2018 Design Strategy

3.4.1. Design Approach

This research (Figure 1) investigates the impacts of applying ISO 50001:2018 in universities on sustainability and future paths using a systematic, four-step method (Figure 1). Firstly, a comprehensive review of literature is conducted to recognize key concepts and establish a theoretical basis. Next, relevant information is collected through a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, such as conducting case studies or interviews with university stakeholders, as well as utilizing surveys and analyzing energy consumption data. Thirdly, the analysis and interpretation of the data collected lead to conclusions and insights, focusing on how implementing ISO 50001:2018 will impact sustainable practices and future directions in higher education. Finally, suggestions are made from the findings to help organizations looking to adopt ISO 50001:2018 or enhance their sustainability efforts. Furthermore, suggestions for future research are proposed to advance sustainability in higher education. This systematic method of investigation ensures a comprehensive and stringent analysis of the topic, providing valuable insights for those in the field of energy management and sustainability, including practitioners, policymakers, and scholars.

Figure 1.

Design approach graph.

The implementation follows a systematic four-step methodology.

Literature Review:

- -

- Comprehensive analysis of existing implementations.

- -

- Identification of key success factors.

- -

- Analysis of gaps in current practices.

Data Collection:

- -

- Qualitative: Stakeholder interviews and case studies.

- -

- Quantitative: Energy consumption data analysis.

- -

- Mixed-methods validation approaches.

Analysis and Interpretation:

- -

- Assessing the impact of sustainability metrics.

- -

- Performance evaluation frameworks.

- -

- Future direction identification.

Recommendations and Future Directions:

- -

- Implementation guidelines.

- -

- Best practice documentation.

- -

- Future research directions.

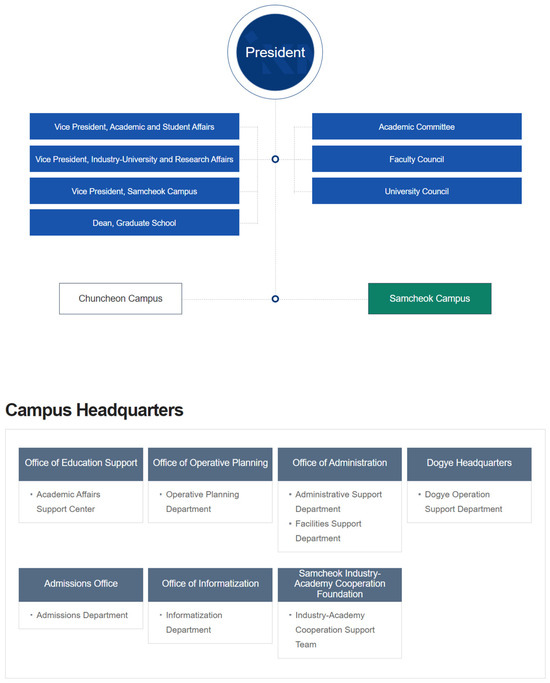

3.4.2. Kangwon National University Samcheok Campus

Located in Samcheok City, Gangwon Province, South Korea, is the Samcheok Campus of Kangwon National University (KNU), a satellite campus of KNU. The organizational structure of the Samcheok Campus (Figure 2) is typically hierarchical like the main institution, although the details may differ. At the top of the organizational hierarchy is the university president, responsible for overseeing all university operations, including those at its various campuses. Vice presidents or vice-chancellors, who report to the president, might oversee specific areas such as academic affairs, research, or administration. The administrative departments at Samcheok Campus are responsible for managing student affairs, finance, human resources, and facilities on a daily basis. These departments help the university achieve its academic objectives while also maintaining efficient campus operations. The academic departments at Samcheok Campus offer diverse graduate and undergraduate programs across multiple subject areas. Usually, a department chair or director oversees each department and is accountable for faculty recruitment, curriculum planning, and academic undertakings. The faculty at Samcheok Campus (Figure 2) are tasked with teaching, research, and service. By providing students with high-quality education, conducting research, and participating in service and governance efforts, they contribute to the university’s academic mission:

Figure 2.

Organization Structure at Kangwon National University Samcheok Campus.

- Hierarchical structure analysis.

- Administrative process mapping.

- Academic department integration.

- Stakeholder engagement strategies.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Design of Energy Management System Standard, Organization Structure and Regulations in University

Customizing ISO 50001:2018 to develop an Energy Management System (EnMS) standard for universities involves tailoring the widely recognized structure to meet the specific energy management needs of educational institutions. The initial step in this approach is to have a deep understanding of the university’s energy context, which includes its infrastructure, stakeholders, and sustainability goals. In order to guarantee successful execution, it is crucial to establish a diverse energy management team and obtain commitments from leadership. These methods provide the necessary assistance and expertise. By carrying out a gap analysis, universities can identify areas needing improvement and set specific objectives aligned with the principles of ISO 50001:2018. Developing an energy policy involving stakeholders is essential for driving energy efficiency initiatives and achieving the set goals. The standard’s operational basis is the execution of processes, which involve monitoring, measuring, and ongoing enhancement following the PDCA cycle. Employee awareness and training programs promote a culture of sustainability and energy conservation, while comprehensive record-keeping and documentation ensure accountability and transparency. Seeking external accreditation to ISO 50001:2018 standards can enhance the university’s reputation as a leader in sustainability within the higher education industry and demonstrate its commitment to efficient energy management. In order for universities to align with the unique requirements of academic institutions, it is essential to take several important steps to ensure the effectiveness of the Energy Management System (EnMS) standard based on ISO 50001:2018 (Table 11).

Table 11.

Requirements and Features of Academic Institutions.

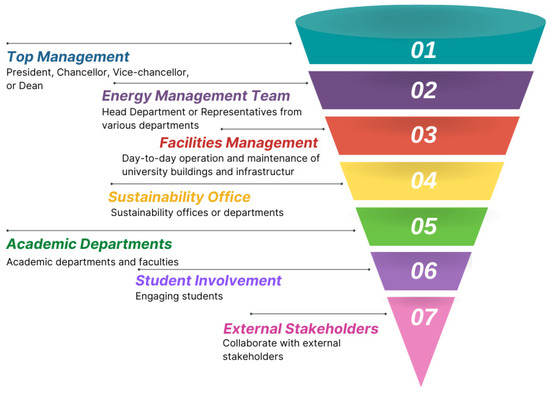

It is important to create a hierarchy in line with ISO 50001:2018’s leadership commitment, continuous improvement, and systematic energy management principles to integrate it into a university’s structure. The university’s top executives oversee the energy strategy, allocate funding, and supervise energy management programs. Underneath them, there is a dedicated Energy Management Team that guides ongoing improvement efforts and oversees the implementation of the Energy Management System (EnMS). This team consists of individuals from academic departments, sustainability offices, and facilities management. Facilities management departments must prioritize energy-saving measures and adhere to energy management processes, while sustainability offices oversee broader sustainability policies and initiatives. Academic departments play a role in improving energy efficiency through research, education, and collaborative work across disciplines. Encouraging sustainable practices involves engaging students, and partnering with external stakeholders provides additional support and resources. By integrating ISO 50001:2018 principles into their organizational framework, academic institutions can successfully handle energy resources, reduce their impact on the environment, and achieve sustainability objectives (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The University Organization Structure by Adapting ISO 50001:2018.

Before introducing ISO 50001:2018, it is essential to thoroughly examine and adjust a university’s organizational structure to align with its existing administrative hierarchies. The guideline highlights the significance of leadership engagement and dedication to energy management techniques. Therefore, the typical components included when integrating ISO 50001:2018 (Figure 1) into the university’s organizational structure are as follows:

Management at the highest level, which includes individuals like the president, chancellor, vice-chancellor, or dean, plays a significant role in determining the strategic path for energy management at universities. Their duties involve endorsing the energy policy, allocating funds, and showing a firm dedication to implementing ISO 50001:2018.

Energy Management Team: It is necessary to form a dedicated Energy Management Team composed of members from various university departments and fields. The interdisciplinary team is in charge of implementing and overseeing the Energy Management System (EnMS), ensuring its integration into the university’s operations, and leading initiatives for continual improvement.

Facilities Management: The department responsible for facilities management typically oversees the daily maintenance and operation of university infrastructure and buildings. This department is crucial in carrying out energy-saving initiatives, conducting energy audits, and ensuring compliance with energy management procedures under ISO 50001:2018.

Sustainability Offices: The promotion of sustainable practices and advancement of environmental initiatives is the duty of specialized sustainability offices or departments in many universities. These offices often take the lead in implementing ISO 50001:2018 and work closely with other departments to incorporate energy management into broader sustainability plans and programs.

Academic departments and faculties can contribute to energy management efforts through research, teaching, and awareness campaigns. They may explore energy-saving technology, integrate energy-focused topics into their curriculum, and collaborate with different departments on interdisciplinary projects to reduce energy consumption.

Get students involved in energy management programs to promote a sustainable campus culture. Student-led organizations advocating for energy conservation, such as sustainability committees and environmental clubs, have the opportunity to collaborate with the administration on energy initiatives and promote awareness through campaigns.

External parties such as energy providers, government bodies, and community organizations can collaborate with universities to enhance energy management efforts. By utilizing these connections, it is possible to gain access to financial opportunities, resources, and knowledge, which can help in implementing ISO 50001:2018 and reaching energy efficiency goals.

Academic institutions can effectively adopt ISO 50001:2018, achieve energy efficiency objectives, and uphold broader sustainability aims through clearly outlining responsibilities in university policies and ensuring accountability across all tiers.

Incorporating ISO 50001:2018 concepts and requirements into university energy management policies and processes is essential to align university legislation with the standard’s requirements. In order to achieve this, the university needs to create an energy policy that demonstrates their dedication to sustainability and energy efficiency, aligned with ISO 50001:2018. According to the university regulations, departments like sustainability offices and facilities management are in charge of implementing the Energy Management System (EnMS) as specified in the standard. These guidelines specify the criteria for meeting ISO 50001:2018 by performing regular energy audits and recording energy efficiency. Additionally, staff, instructors, and students must engage in training programs to enhance their understanding of energy management techniques. Monitoring and reporting systems track the progress of energy efficiency goals, while documentation and record-keeping protocols ensure transparency and accountability. Incorporating ISO 50001:2018 into university regulations means integrating the standard’s principles and requirements into the school’s energy management policies, procedures, and guidelines. University guidelines regarding ISO 50001:2018 typically address several crucial areas (Table 12).

Table 12.

University Regulations by Adapting ISO 50001:2018.

4.2. Fault Detection Performance

Before delving into the specific performance metrics of the fault detection methods employed, it is important to highlight the significance of the computing environment that supports our deep learning models. The effectiveness of these models in identifying faults in solar panels hinges not only on their architecture but also on the computational resources at their disposal. Table 13 presents the key specifications of the computing equipment utilized in this study, designed to meet the intensive requirements of our analytical processes.

Table 13.

Computing Equipment.

This computing setup, featuring a powerful 13th Gen Intel Core i9 processor and 32 GB of RAM, provides the necessary computational resources to handle the higher demands of the InceptionV3 model effectively. Utilizing online platforms like Kaggle further enhances our capability to leverage cloud-based resources for training and testing our models, ensuring optimal performance in our deep learning tasks. Additionally, software tools like OpenCV and Pandas are employed to assist in dataset creation, preprocessing, and analysis, facilitating the development of a robust and reliable dataset for model training.

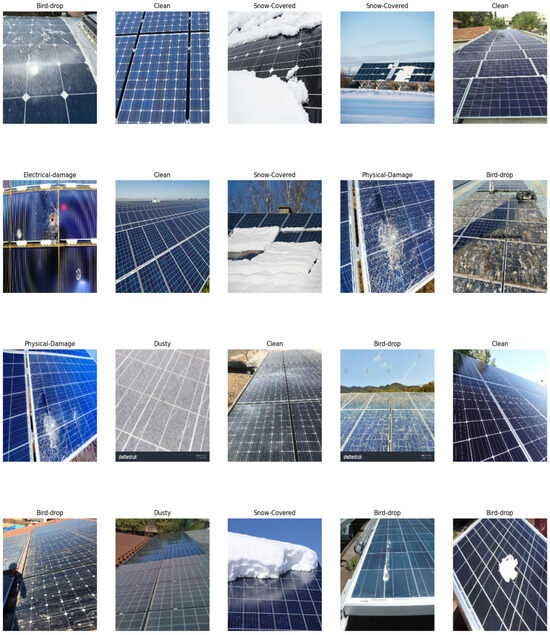

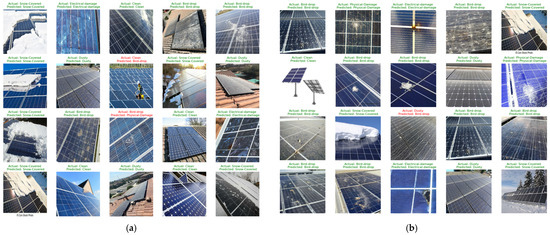

Decreased energy generation is caused by the buildup of trash on solar panels, such as dust, snow, bird droppings, and other debris. This decreases the panels’ ability to convert sunlight into energy. Regular monitoring and cleaning are essential in order to maintain the efficiency of solar panels. It is important to have a methodical process for monitoring and cleaning in order to maximize resource utilization, reduce maintenance expenses, and improve panel efficiency. Having a carefully organized schedule for checking and maintaining solar panels can help owners optimize energy generation, prolong panel life, and support overall sustainability objectives. This dataset aims to evaluate the effectiveness of various machine-learning classifiers in identifying dust, snow, bird droppings, and mechanical and electrical issues on solar panels. The dataset for classification contains six class folders: bird drop, clean, snow-covered, bird drop, dusty and physical damage (Figure 4). A slight discrepancy in the number of photos collected is present due to sourcing data from the internet. Multiple steps are required in the data verification process to guarantee the quality and integrity of the dataset used to train a machine learning model. Getting the data ready for training involves carrying out preprocessing tasks like cleansing, standardization, and feature creation. Reviewing the preprocessed data is crucial to identify anomalies, inconsistencies, or missing variables that may impact the model’s performance. This can involve creating visuals such as plots or graphs to detect patterns or outliers in the data. Furthermore, it is crucial to address class imbalances in order to reduce possible biases in the model caused by overrepresentation or underrepresentation of certain classes.

Figure 4.

Training data.

Splitting the dataset into training and validation sets is essential for assessing the model’s performance on new data. Allowing the use of cross-validation procedures ensures the strength and adaptability of the model. Sustaining the model’s precision and efficiency in the long term also necessitates on consistent monitoring and revising of the training data as new data arises. By closely examining the training data, machine learning practitioners can develop more precise and reliable models for a range of uses, such as detecting faults in solar panels.

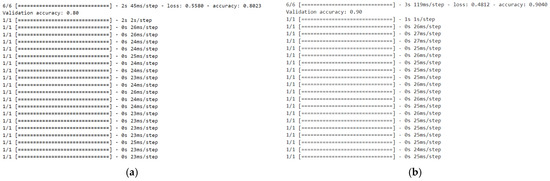

The performance of the two deep learning architectures, MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3, when applied to detect defects in solar panel images, shows noticeable differences. The results (as shown in Figure 5) indicate the relative strengths and weaknesses of both models in terms of accuracy and loss value.

Figure 5.

Loss and accuracy result: (a) MobileNetV2, (b) InceptionV3.

- MobileNetV2 Performance: The MobileNetV2 model achieved an accuracy of 80% with a loss value of 55%. While this is a respectable performance, especially considering the model’s lightweight nature and suitability for resource-constrained environments, it reveals that MobileNetV2 may struggle to capture the more complex features of solar panel defects. The higher loss value (55%) suggests that the model has room for improvement in minimizing prediction errors and refining its ability to differentiate between defective and non-defective panels. However, the trade-off in computational efficiency makes it a valuable choice for real-time applications where low power consumption is a priority.

- InceptionV3 Performance: On the other hand, the InceptionV3 model demonstrated superior performance with an accuracy of 90% and a lower loss value of 48%. The increased accuracy indicates that InceptionV3 is more effective at identifying defects in solar panel images, likely due to its deeper and more complex architecture, which allows it to extract more intricate patterns from the data. Additionally, the lower loss value (48%) suggests better optimization and a more consistent ability to generalize across different solar panel images, reducing the likelihood of misclassification. InceptionV3′s higher computational complexity may make it more suitable for scenarios in which accuracy is a higher priority than computational efficiency.

The findings indicate that InceptionV3 outperforms in defect detection accuracy and loss reduction, but MobileNetV2 may be favored for tasks needing quicker, resource-efficient performance (Figure 6). Choosing the right model necessitates consideration of the particular use case, requiring a trade-off between precision and computational speed.

Figure 6.

Prediction result: (a) MobileNetV2, (b) InceptionV3. Green Color: Correct Prediction, Red Color: Wrong Prediction.

In situations with high stakes in which even small errors could lead to major financial or operational impacts, InceptionV3 is the preferred option. In contrast, in situations where speed and resource efficiency are crucial, like in on-site monitoring systems with low computational power, MobileNetV2 provides a practical option despite its reduced accuracy (Table 14).

Table 14.

Comparison of key metrics.

- Accuracy: InceptionV3 outperforms MobileNetV2 in terms of accuracy by a 10% margin, making it a more reliable model for defect detection tasks. This increased accuracy suggests that InceptionV3 can detect more subtle defects, improving the overall detection rate.

- Loss Value: The lower loss value of InceptionV3 (48%) compared to MobileNetV2 (55%) reflects better performance in terms of minimizing prediction errors. This implies that InceptionV3 produces fewer misclassifications and has a more refined understanding of the data, leading to better generalization.

- Computational Efficiency: Despite the higher performance of InceptionV3, MobileNetV2 remains a strong contender due to its computational efficiency. It requires fewer resources and has lower latency, which makes it suitable for real-time applications in environments where computational power is limited, such as embedded systems for monitoring solar panels in remote locations.

5. Future Prospects

5.1. Implications for Sustainability and Future Directions

The adoption of ISO 50001:2018 in academic institutions not only enhances energy management practices but also plays a pivotal role in fostering sustainability and environmental stewardship. By integrating these energy management standards, universities can align their operational strategies with broader environmental objectives, promoting a culture of sustainability within their communities. This integration creates a framework for continuous improvement in energy performance, facilitating the development and implementation of innovative strategies that minimize energy consumption and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, by harnessing renewable energy sources, such as solar and hydrogen technologies, institutions can significantly contribute to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 7, which emphasizes the importance of sustainable energy access for all. Therefore, our research into hydrogen and solar–hydrogen systems aligns well with the principles of ISO 50001:2018, highlighting the potential for these technologies to transform energy management practices in academic settings and support the transition toward a more sustainable future.

Universities can support global sustainability objectives by reducing their carbon emissions, decreasing resource use, and addressing environmental impacts with strategic energy conservation methods. Furthermore, academic institutions can improve the energy performance and efficiency of all campus buildings by adopting ISO 50001:2018. Universities have the opportunity to enhance their energy efficiency and reduce operational costs by acknowledging the potential for energy conservation, setting specific objectives, and implementing energy-saving initiatives. This enhances economic sustainability and allows for more resources to be directed towards educational programs, research endeavors, and student support services. Furthermore, the university’s commitment to the best energy management practices is demonstrated by its ISO 50001:2018 certification, which also adds credibility to the institution. By boosting the university’s reputation as a leader in sustainability within the higher education sector, it attracts prospective students, faculty, and funding prospects. Additionally, accreditation could result in collaborations with government entities, business groups, and other supporters of sustainability and energy initiatives.

Over time, the implementation of ISO 50001:2018 sets the stage for ongoing progress and innovation in the energy management sector. Universities can adapt to evolving energy technologies, legal obligations, and sustainability trends through implementing ongoing enhancement. This involves researching sustainable energy sources, such as implementing intelligent technology for managing and monitoring energy, and developing creative energy solutions. Furthermore, ISO 50001:2018 provides academic institutions with an opportunity to address broader sustainability concerns beyond energy management alone. It advocates for implementing sustainable practices in waste management, procurement, transportation, and curriculum development, as well as other aspects of university operations. Students are equipped with the knowledge and skills needed to emerge as future leaders in sustainability across a range of fields and industries using a comprehensive approach to sustainability. Ultimately, the adoption of ISO 50001:2018 within the higher education sector will have important implications for sustainability and forthcoming pathways. Universities can reduce their environmental impact, boost their financial stability, enhance their reputation, foster innovation, and prepare students to address complex sustainability challenges in the future.

5.2. Solar Fault Detection for an AIoT-Based Solar–Hydrogen System at a University

Solar–hydrogen systems, which integrate solar power generation with hydrogen production and storage, provide hopeful solutions for sustainable energy control. Yet, a significant hurdle in implementing these systems in institutions such as universities is concerns about the dependability and effectiveness of solar panels. Issues with solar panels, such as shading, soiling, or physical harm, can result in notable decreases in energy output. It is crucial to quickly and accurately identify these faults in order to uphold system performance and enhance energy conversion. AIoT solutions combine artificial intelligence with IoT sensors and devices to offer an innovative way to monitor and detect faults in solar–hydrogen systems in real time.

The incorporation of AIoT in solar–hydrogen setups allows for ongoing supervision of solar panel activity via multiple sensors that gather information like temperature, voltage, current, and irradiance. Next, the information undergoes analysis with advanced deep learning algorithms such as MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 to identify irregularities and possible malfunctions. AI algorithms are able to predict and classify faults by analyzing historical and real-time data and can also set off maintenance alarms. Using AIoT allows for early fault detection, decreasing downtime and enhancing energy efficiency. Some of the types of faults (Table 15) that can be detected in solar–hydrogen systems are listed below.

Table 15.

Fault types and detection techniques in solar–hydrogen AIoT systems.

- Shading: Partial shading of solar panels can significantly reduce energy output, and AI models can identify shading patterns based on data from sensors.

- Soiling: Accumulation of dirt or dust on the panels can lead to decreased efficiency. AIoT systems detect performance drops associated with soiling.

- Panel degradation: Long-term wear and tear of panels can result in performance degradation, which can be detected using trend analysis and predictive maintenance algorithms.

- Electrical faults: These include issues like short circuits, grounding faults, or connection failures that affect the electrical performance of the system.

The incorporation of AIoT into solar–hydrogen systems at universities offers notable advantages. The use of deep learning models such as MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 enables precise solar fault detection, ensuring timely identification of potential system performance risks (Table 16). The lightweight design of the models allows for their efficient operation on edge devices, making them ideal for distributed systems at university campuses. In addition, universities can guarantee a dependable energy supply, extend the system’s lifespan, and lower operational expenses by stopping unnoticed faults from turning into significant issues that could affect solar infrastructure.

Table 16.

Comparison of MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 for fault detection in solar–hydrogen systems.

6. Conclusions

The research on solar fault detection in university-based solar–hydrogen systems, utilizing AIoT-enabled deep learning models, demonstrates significant advancements in energy management and fault detection efficiency. Customizing ISO 50001:2018 for universities offers a robust framework for developing Energy Management Systems (EnMS), promoting energy efficiency, and achieving sustainability goals. By aligning university operations with ISO 50001:2018’s principles, universities can structure their energy management efforts, with leadership commitment, multidisciplinary teams, and continuous improvement cycles ensuring the integration of energy-saving practices into daily activities. This framework establishes a clear organizational structure, with top management endorsing the energy policy, facilities management overseeing day-to-day operations, and sustainability offices driving broader initiatives. In the solar fault detection component, the comparison between MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 offers insights into the trade-offs between accuracy and computational efficiency. MobileNetV2, which achieves 80% accuracy, is more suitable for real-time, resource-constrained environments due to its lightweight architecture. This makes it ideal for on-site monitoring systems, especially when a low amount of computational power is available. However, its higher loss value (55%) suggests that it has room for improvement in terms of accurately identifying complex defects. On the other hand, InceptionV3 achieved a superior 90% accuracy and lower loss value (48%), indicating better performance in detecting subtle defects and minimizing prediction errors. Its more complex architecture allows it to extract intricate patterns, making it more suitable for high-precision applications. However, InceptionV3’s higher computational demands mean it may be less appropriate for real-time, low-power environments, whereas it is ideal for centralized systems where accuracy is a priority. The overall findings highlight that the choice between MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 depends on the specific application scenario. For real-time monitoring and resource-efficient environments, MobileNetV2 offers a practical solution. In contrast, InceptionV3 is better suited for high-stakes environments where accuracy and defect detection precision are critical.

By implementing ISO 50001:2018, this research thoroughly examines and analyzes energy management system standards, focusing on their relevance to implementing solar–hydrogen systems on university grounds. The research has highlighted the significant implications and potential benefits for colleges incorporating solar–hydrogen technologies by examining the basic concepts and requirements of ISO 50001:2018 in detail, as well as their practical application in academia. By using ISO 50001:2018, universities have the ability to establish structured systems to enhance sustainable practices, optimize energy efficiency, and encourage continuous improvements in energy management. This paper uses Kangwon National University Samcheok Campus as an example to show how organizational structures, rules, and best practices are important in implementing energy management system standards in academic institutions. Overall, this article provides important viewpoints and suggestions for educational institutions aiming to enhance their efforts in sustainable energy growth through the use of solar–hydrogen systems and through promoting environmental consciousness within the academic community using ISO 50001:2018.

The integration of deep learning models such as MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 into university-based solar–hydrogen systems provides an effective means of enhancing energy management. While MobileNetV2 excels in computational efficiency, InceptionV3 achieves higher accuracy, making it essential to balance the demands of the specific use case with the strengths of each model. Through continuous improvement, adherence to ISO 50001:2018, and the adoption of AIoT-based monitoring, universities can maintain their energy systems’ operational efficiency and further their sustainability efforts.

Author Contributions

S.R.J.: project evaluation, methodology, investigation, resources, supervision, modeling, simulation. Y.J.: data analysis, investigation. S.P.: software development, functionality evaluation. K.K.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by “Regional Innovation Strategy (RIS)” through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) (2022RIS-005).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, Y.; Xia, S.; Huang, P.; Qian, J. Energy transition: Connotations, mechanisms and effects. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 52, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Muneer, T. Energy supply, its demand and security issues for developed and emerging economies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 1388–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Msigwa, G.; Farghali, M.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.S. Cost, environmental impact, and resilience of renewable energy under a changing climate: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 741–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y. Transitioning to sustainable energy: Opportunities, challenges, and the potential of blockchain technology. Front. Energy Res. Sec. Sustain. Energy Syst. 2023, 11, 1258044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peharz, G.; Dimroth, F.; Wittstadt, U. Solar hydrogen production by water splitting with a conversion efficiency of 18%. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 3248–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouabi, H.; Lajouad, R.; Kissaoui, M.; El Magri, A. Hydrogen production by water electrolysis driven by a photovoltaic source: A review. E-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 8, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdelMeguid, H.S.; Al-Johani, H.F.; Saleh, Z.F.; Almaki, A.A.; Almaki, A.M. Advancing Green Hydrogen Production in Saudi Arabia: Harnessing Solar Energy and Seawater Electrolysis. Clean Energy Sustain. 2023, 1, 10006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, M.; Han, D.S. Efficient solar-powered PEM electrolysis for sustainable hydrogen production: An integrated approach. Emergent Mater. 2024, 7, 1401–1415. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42247-024-00697-y (accessed on 5 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Algburi, S.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. A review of hybrid renewable energy systems: Solar and wind-powered solutions: Challenges, opportunities, and policy implications. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.; Said, A.; Saad, M.H.; Farouk, A.; Mahmoud, M.M.; Alshammari, M.S.; Alghaythi, M.L.; Aleem, S.H.E.A.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Omar, A.I. A review of water electrolysis for green hydrogen generation considering PV/wind/hybrid/hydropower/geothermal/tidal and wave/biogas energy systems, economic analysis, and its application. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 87, 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnabuife, S.G.; Hamzat, A.K.; Whidborne, J.; Kuang, B.; Jenkins, K.W. Integration of renewable energy sources in tandem with electrolysis: A technology review for green hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M.; Al-Jiboory, A.K. Hydrogen energy future: Advancements in storage technologies and implications for sustainability. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marouani, I.; Guesmi, T.; Alshammari, B.M.; Alqunun, K.; Alzamil, A.; Alturki, M.; Hadj Abdallah, H. Integration of Renewable-Energy-Based Green Hydrogen into the Energy Future. Processes 2023, 11, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwyn, R.G.; Al-Hinai, A.; Margaret, V. A comprehensive review on energy management strategy of microgrids. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 5565–5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyan, P.; Saravanan, S.; Usha, K.; Kannadasan, R.; Alsharif, M.H.; Kim, M.K. Technological advancements toward smart energy management in smart cities. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 648–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare, M.S.; Abdulkarim, A.; Zeeshan, M.; Shuaibu, A.N. A Comprehensive Overview on Demand Side Energy Management Towards Smart Grids: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Direction. In Energy Informatics; Sringer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 6, Available online: https://energyinformatics.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s42162-023-00262-7 (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Kumar, M.; Panda, K.P.; Naayagi, R.T.; Thakur, R.; Panda, G. Comprehensive Review of Electric Vehicle Technology and Its Impacts: Detailed Investigation of Charging Infrastructure, Power Management, and Control Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, S.B.; Mahmoud, M. A deep learning model for intelligent home energy management system using renewable energy. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijoyo, F.A. AI-powered deep learning for sustainable industry 4.0 and internet of things: Enhancing energy management in smart buildings. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 104, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyazi, M.; Sardar, P.; Thomas, S.I.; Daghigh, R.; Jamali, A.; Esch, T.; Kemper, H.; Langari, R.; Khayyam, H. Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning in Energy Management Systems, Control, and Optimization of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, K.; Bugiotti, F.; Morosuk, T. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Energy Conversion and Management. Energies 2023, 16, 7773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, H.M.; Yusuf, S.A.; Abubakar, A.H.; Abdullahi, M.; Hassan, I.H. A systematic review of deep learning techniques for rice disease recognition: Current trends and future directions. Frankl. Open 2024, 8, 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firnando, F.M.; Setiadi, D.R.I.M.; Muslikh, A.R.; Iriananda, S.W. Analyzing InceptionV3 and InceptionResNetV2 with Data Augmentation for Rice Leaf Disease Classification. J. Fut. Artif. Intell. Tech. 2024, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Flores, C.; San-Martin, P. Deep learning for Chilean native flora classification: A comparative analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1211490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.; Utkin, A.; Chaves, P. Enhanced Automatic Wildfire Detection System Using Big Data and EfficientNets. Fire 2024, 7, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Zitar, R.A.; Almotairi, K.H.; Hussein, A.M.; Abd Elaziz, M.; Nikoo, M.R.; Gandomi, A.H. Wind, Solar, and Photovoltaic Renewable Energy Systems with and without Energy Storage Optimization: A Survey of Advanced Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques. Energies 2022, 15, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, B.; Peng, J. A review of deep learning for renewable energy forecasting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 198, 111799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lin, T.; Yu, Q.; Du, H.; Li, J.; Fu, X. Review of Deep Reinforcement Learning and Its Application in Modern Renewable Power System Control. Energies 2023, 16, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hu, W.; Cao, D.; Liu, W.; Huang, R.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Blaabjerg, F. Data-driven optimal energy management for a wind-solar-diesel-battery-reverse osmosis hybrid energy system using a deep reinforcement learning approach. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 227, 113608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, A.; Kamalaruban, P. Applications of reinforcement learning in energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137, 110618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, M.; Niaz, H.; Na, J.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A.; Liu, J. Machine learning-based utilization of renewable power curtailments under uncertainty by planning of hydrogen systems and battery storages. J. Energy Storage 2021, 41, 103010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, J.; Elavarasan, R.; Shafiullah, G.; Jamal, T.; Khan, I. A holistic review on energy forecasting using big data and deep learning models. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 13489–13530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaiber, J.; Dinther, C. Deep Learning for Variable Renewable Energy: A Systematic Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshirband, S.; Rabczuk, T.; Chau, K. A Survey of Deep Learning Techniques: Application in Wind and Solar Energy Resources. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 164650–164666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Herodotou, H.; Mohsin, S.; Javaid, N.; Ashraf, N.; Aslam, S. A survey on deep learning methods for power load and renewable energy forecasting in smart microgrids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introna, V.; Santolamazza, A.; Cesarotti, V. Integrating Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Innovations for Enhanced Energy Management Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulins, A.; Sudars, K.; Edelmers, E.; Namatevs, I.; Ozols, K.; Komasilovs, V.; Zacepins, A.; Kviesis, A.; Reinhardt, A. Deep Learning for Wind and Solar Energy Forecasting in Hydrogen Production. Energies 2024, 17, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetya, B.; Wahono, D.R.; Dewantoro, A.; Anggundari, W.; Yopi. The role of Energy Management System based on ISO 50001 for Energy-Cost Saving and Reduction of CO2-Emission: A review of implementation, benefits, and challenges. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 926, 012077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda-Orjuela, P.P.; García-Díaz, J.C.; Pulido-Rojano, A.; Cañón-Zabala, G. ISO 50001: 2018 and Its Application in a Comprehensive Management System with an Energy-Performance Focus. Energies 2019, 12, 4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, S.R.; Park, S.; Kwon, K. Knowledge-Based Modeling Approach: A Schematic Design of Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) for Hydrogen Energy System. In Proceedings of the IEEE 14th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 8–10 January 2024; pp. 0235–0241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, S.R.; Park, S.; Kwon, K. H2 EMS: A Simulation Approach of a Solar-Hydrogen Energy Management System. In Proceedings of the IEEE 14th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 8–10 January 2024; pp. 0403–0408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, S.R.; Yeon, A.N.; Park, S.; Kwon, K. Solar–Hydrogen Storage System: Architecture and Integration Design of University Energy Management Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, S.R.; Park, S.; Kwon, K. H2 URESONIC: Design of a Solar-Hydrogen University Renewable Energy System for a New and Innovative Campus. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.; Lee, H.-B.; Kim, N.; Park, S.; Joshua, S.R. Integrated Battery and Hydrogen Energy Storage for Enhanced Grid Power Savings and Green Hydrogen Utilization. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, S.R.; Yeon, A.N.; Park, S.; Kwon, K. A Hybrid Machine Learning Approach: Analyzing Energy Potential and Designing Solar Fault Detection for an AIoT-Based Solar–Hydrogen System in a University Setting. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, S.R.; Park, S.; Kwon, K. Solar Panel Fault Detection: Applying Convolutional Neural Network for Advanced Fault Detection in Solar-Hydrogen System at University. In Proceedings of the IEEE 24th International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability, and Security Companion (QRS-C), Cambridge, UK, 1–5 July 2024; pp. 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, S.R.; Park, S.; Kwon, K. AI-Driven Green Campus: Solar Panel Fault Detection Using ResNet-50 for Solar-Hydrogen System in Universities. In Proceedings of the IEEE 24th International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability, and Security Companion (QRS-C), Cambridge, UK, 1–5 July 2024; pp. 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilanci, C.; Dincer, I.; Ozturk, H.K. A review on solar-hydrogen/fuel cell hybrid energy systems for stationary applications. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2009, 35, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemir, D.; Dincer, I. A new solar energy-based system integrated with hydrogen storage and heat recovery for sustainable community. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M.; Megahed, T.F.; Ookawara, S.; Hassan, H. A review of water electrolysis–based systems for hydrogen production using hybrid/solar/wind energy systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 86994–87018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gursoy, M.; Dincer, I. Design and assessment of a solar-driven combined system with hydrogen production, liquefaction and storage option. Int. J. Thermofluids 2024, 22, 100599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczur, M.; Hassan, Q.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Olapade, O.T.; Wieteska, S. Massive Green Hydrogen Production Using Solar and Wind Energy: Comparison between Europe and the Middle East. Energies 2023, 16, 5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Algburi, S.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. Green hydrogen: A pathway to a sustainable energy future. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 310–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangon, J.; Darekar, A. Advancements in hydrogen energy systems: A review of levelized costs, financial incentives and technological innovations. Innov. Green Dev. 2024, 3, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]