Abstract

The monitoring of wildlife habitats is crucial for effective conservation efforts, particularly where biodiversity faces significant threats. This study aimed to monitor the biodiversity of wild mammals in a protected area (PA) of Northeastern Bangladesh, with a particular focus on detecting previously unrecorded species using camera traps. We deployed nine camera traps across 19 locations inside the PAs of Satchari National Park (SNP) from May 2024 to April 2025. Further, the camera-trap data were analyzed to evaluate the existing wild mammals, along with their activity patterns and seasonal variations, in SNP. Our study identified the Asiatic black bear in SNP for the first time, representing a significant contribution to biodiversity records of Bangladesh. Among the other frequently documented wild mammals were the wild boar, northern pig-tailed macaque, and barking deer, whereas less commonly detected species included the crab-eating mongoose and jungle cat. Activity pattern analysis of Asiatic black bear revealed a predominantly nocturnal-to-crepuscular behavior, with distinct bimodal peaks during early morning and evening. The present study showed that the Asiatic black bear was active in pre-monsoon and winter; however, it was absent during the rainy season, suggesting seasonal habitat use or detectability challenges. This is the first study to confirm the presence of Asiatic black bears in PAs of SNP using camera traps. These findings also highlight the importance of long-term biodiversity monitoring for continued conservation efforts to protect the diverse wildlife of SNP. The detection of previously undocumented wild mammals highlights the ecological importance of SNP, urging authorities to tighten the ongoing conservation initiatives. Understanding the diel and seasonal activity patterns would instruct the timing of conservation and habitat management strategies. This study also makes the integration of camera-trap monitoring into long-term biodiversity management to guide evidence-based conservation policies in Bangladesh’s PAs.

1. Introduction

Understanding wild animal species’ activity patterns is essential for effective conservation, as these behaviors, ranging from diurnal to cathemeral, are influenced by environmental (e.g., light and temperature), biological factors (e.g., competition and predation risk), and human-induced factors [1,2]. Camera trapping has become a powerful, non-invasive tool for vegetation and animals compared to most conventional methods, without requiring researchers to cut transects in the forest or perform direct observation of animals [3]. Subsequently, camera trapping has become a standard method for long-term monitoring of wild animals, including their behavior and natural habitats [2,4]. Therefore, monitoring shifts in animal activity patterns offers valuable insights into ecological dynamics and helps assess how human disturbances influence wildlife behavior and conservation outcomes [5].

In Bangladesh, two of the world’s eight recognized bear species have been documented: the Tibetan black bear (Ursus thibetanus thibetanus), a subspecies of the Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus), and the Malayan sun bear (Helarctos malayanus malayanus), a subspecies of the sun bear (Helarctos malayanus) [6,7]. These species thrive in a variety of habitats, including coniferous forests, oak–coniferous mixed forests, and deciduous and broadleaf forests, as well as shrublands and grasslands [8,9]. The sloth bear (Melursus ursinus) has been declared locally extirpated in Bangladesh, as per the latest IUCN regional assessment, primarily due to the loss of wet deciduous forests in the northern and central regions [10]. On the other hand, the Asiatic black bear has been designated as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and is classified as critically endangered, with its population seeing a significant drop due to habitat degradation, poaching, and human–wildlife conflict in different forest areas in Bangladesh [10]. Monitoring trends in the abundance and distribution of Asiatic black bear has become an important conservation objective, as the habitat and populations of this species need to intensify and expand globally [11,12,13,14]. The previous studies suggested that the Asiatic black bear was relatively prevalent in the Chittagong region and adjoining border areas of Northeastern Bangladesh about a decade ago [15,16,17]. However, while recent evidence points toward a decline in Asiatic black bears, including in the northeastern region of Bangladesh, insufficient datasets and the absence of scientific evaluation limit the interpretation certainty, highlighting the need for rigorous and landscape-scale assessments.

Protected areas (PAs) are vital for biodiversity conservation, yet they currently cover only a small fraction of land and marine areas, with very limited effective management in Bangladesh [18]. Most PAs are concentrated in coastal and marine habitats, leaving gaps in freshwater and broader terrestrial coverage [18,19]. No Bangladeshi sites are listed on the IUCN Green List, and critical species like the Asiatic black bear remain largely unprotected [18,19]. With growing anthropogenic pressure and biodiversity threats, more balanced conservation efforts are essential. Satchari National Park (SNP) is a notable designated PA situated in the Sylhet division of Bangladesh. Importantly, SNP is distinguished for its abundant biodiversity and varied ecosystems, including many that are uncommon and at risk of endangerment and regional extinction [10]. Previous studies reported a variety of wild mammalian species, including the northern pig-tail macaque, rhesus macaque, leopard cat, jungle cat, fishing cat, large Indian civet, palm civet, masked civet, jackal, wild boar, and barking deer in SNP and around PAs in the Sylhet division [20,21,22,23,24]. Nevertheless, there is currently no scientific report or evidence or notification that the Asiatic black bear is present in SNP. Based on a variety of local community observations, the Asiatic black bear may exist in SNP or the surrounding, indicating that the Asiatic black bear may still make appearances in some parts of SNP.

To verify the species’ existence and evaluate the Asiatic black bear’s conservation status in the SNP area, systematic scientific surveys, camera-trap monitoring, and ecological evaluations are required. Additionally, there has been a significant gap in the constant monitoring and updated evaluations of wildlife biodiversity, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic in this region. The global health crisis caused an interruption in investigations and conservation initiatives, resulting in gaps in the understanding of the current status of wildlife biodiversity in SNP, thus highlighting the necessity for comprehensive camera-trap monitoring here. Therefore, the present study aims to monitor the status of distribution, abundance, and activity patterns of wild animal species across SNP, with a particular focus on the Asiatic black bear.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

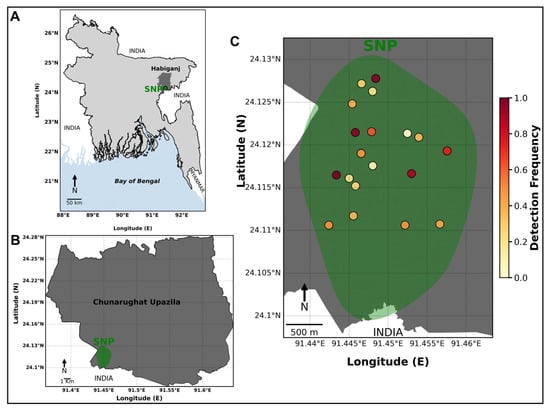

The study was conducted in SNP, located at 24°07′12″ N 91°27′03″ E, spanning 2.43 km2 and safeguarding approximately 2 km2 of mixed-evergreen forest within the Raghunandan hill reserved forest in the Chunarughat Upazila, Habiganj District under Sylhet division, Bangladesh (Figure 1) [25]. This ecologically significant forest serves as a biodiversity hotspot, hosting a variety of flora and fauna, alongside patches of rubber (Hevea brasiliensis), agar (Aquilaria sp.), and teak (Tectona grandis) plantations [26]. The landscape of SNP is characterized by rolling hills and mounds, under a tropical monsoon climate that receives an average annual rainfall of 5173 mm. Seasonal sand-bedded streams crisscross the forest, enhancing its ecological diversity. The forest is bordered by human settlements and tea plantations, with a national highway bisecting the northern boundary of the Raghunandan hill reserved forest. Connectivity between SNP and the Raghunandan hill reserved forest is maintained through five small bridges, which function as wildlife underpasses, allowing safe movement across the streambeds. This intricate interplay of natural and human-modified landscapes makes SNP a critical area for conservation research and biodiversity management.

Figure 1.

(A) Map of the study area in Bangladesh showing the location of SNP in Habiganj District, Sylhet Division, near the northeastern border with India. (B) Enlarged map of Chunarughat Upazila indicating the relative location of SNP within the administrative region. (C) Spatial distribution of camera-trap stations inside SNP, where each point represents a camera-trap location color-coded by detection frequency of wild mammals. Detection frequency ranges from low (yellow) to high (red), indicating spatial variation in wild species activity and detection intensity across SNP. The green polygon denotes the approximate boundary of SNP. North arrows and scale bars are provided for geographic reference.

2.2. Camera Trap

We conducted the camera-trap survey in SNP from May 2024 to April 2025, deploying a total of nine “Digital Wildlife Cameras” (TC06, China) across 19 locations. Camera traps were strategically placed along active wildlife trails, including feeding and resting sites, valleys, and streambanks. All procedures of the installation of camera traps were carried out according to the previous report described by Shawon et al. [27], but with slide modifications. Briefly, each camera trap was fastened firmly to a tree at a height of 1 to 1.5 m above the ground, utilizing strong chains to guarantee stability. The cameras were enclosed in protective iron enclosures to prevent damage or tampering by wildlife and humans, or theft. No bait or lure substances were employed, guaranteeing impartial recording of wildlife activity. The cameras were operated continuously for 24 h daily, recording images with a minimal interframe interval of 10 s. Prior to the deployment of camera trapping, each of the camera traps was configured with high-sensitivity motion detection with a trigger speed of 1 s and programmed to capture a burst of three consecutive images per trigger. The camera-trapping infrared flash was set to low-glow mode to minimize the disturbance to wild animal movement. Before final operation, each of the camera trappings was tested on-site to evaluate the sensor activation, photo quality, and date and time accuracy, followed by a test walk to ensure a proper viewpoint and detection angle of the object. Cameras were inspected during routine field visits to confirm continuous operation. Bi-weekly assessments were carried out to check memory card status, replace batteries, and ensure the devices were functioning properly. Furthermore, certain images from camera traps were repositioned every 1–1.5 months to enhance spatial coverage and record a wider array of wildlife. Every captured image contained a timestamp and date, enabling systematic data arrangement and analysis [27].

2.3. Data Analysis

The present study assessed the camera-trapping datasets to identify the wild animal species according to the previously published studies [27,28,29]. All collected photos were manually inspected to distinguish genuine wildlife detections from false triggers. We also verified our identified wild animal species by consulting with research team members, field wildlife guides, local community members, and conservation specialists from SNP. The raw data from the camera traps were methodically organized using Flexible Renamer (ver. 8.4) and NeoFileInfolist (ver. 1.4.1.0) software. Prior to further analysis, the recorded photos (RPs; Table 1) were preprocessed following the method described by Lim et al. [30]. During image capture, some species may trigger the camera multiple times while remaining in the detection zone, resulting in multiple photographs of the same individual within a single event [30,31]. To minimize the impact of repeated captures on Relative Abundance Index (RAI) values, duplicate photos were excluded by retaining only independent photographs (IPs). Consecutive photos of the same species were taken within a 30 min interval that considered a single-event occurrence [32]. The proportion of independent photographs (PI%) represents the percentage of deduplicated images relative to the total number of captures. The wild animal species is considered a common resident if the proportion of its independent photographs exceeds 1% [33]. The preprocessed data were subsequently analyzed and visualized using Python (v3.11.3) packages “numpy” [34], “pandas” [35], “seaborn” [36], and “Matplotlib” [37]. The RAI was calculated using the following formula:

where Ai represents the number of independent photographs of wild animal species in category i, and N denotes the number of valid camera-trap days [32]. Seasonal fluctuations were analyzed by categorizing monthly data into three distinct intervals: the pre-monsoon hot season (March–June), the monsoon wet season (July–October), and the dry winter season (November–February) [38]. Seasonal differences in diel activity patterns were evaluated using the Watson–Williams F-test for circular data [39], implemented via the “pycircstat” package in Python (v3.11.3). Our study map was generated using the Python packages “Cartopy” (v0.22) and “Matplotlib” [37], utilizing shapefile data from the Global Administrative Areas (GADM) database [40].

Table 1.

The identification of wild mammals by camera traps in SNP, Bangladesh.

3. Results

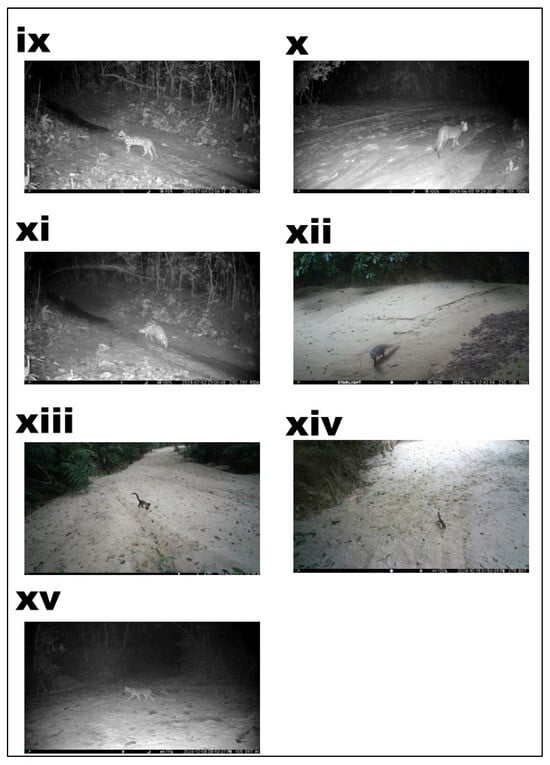

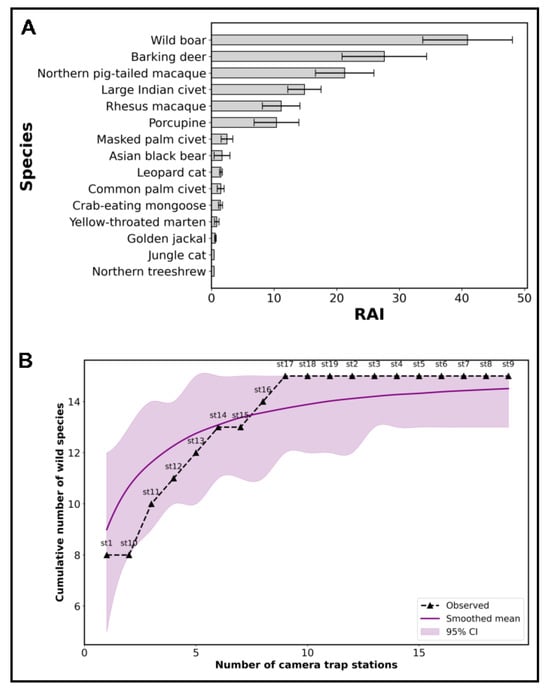

This study recorded 8333 camera-trap photos of independent counts obtained from 19 camera-trap locations in SNP, averaging 216 camera-trap nights per site. After the curation of all camera-trap photos, a total of 5779 images were obtained that identified 15 different wild mammal species in SNP (Table 1 and Figure 2). Importantly, our camera trap recorded the Asiatic black bear (n = 8, RAI= 1.69 ± 1.27) for the first time in SNP, a significant finding considering its conservation status (Table 1 and Figure 3A). Our camera trap also recorded other wild mammals, including wild species such as the wild boar (n = 1834, RAI = 40.90 ± 7.17); northern pig-tailed macaque (n = 954, RAI = 21.28 ± 4.67); rhesus macaque (n = 447, RAI = 11.14 ± 2.99); barking deer (n = 1238, RAI = 27.61 ± 6.75); large Indian civet (n = 666, RAI = 14.85 ± 2.67); common palm civet (n = 21, RAI = 1.48 ± 0.54); masked palm civet (n = 41, RAI = 2.48 ± 0.92); leopard cat (n = 54, RAI = 1.53 ± 0.22); jungle cat (n = 4, RAI = 0.42 ± 0.00); porcupine (n = 441, RAI = 10.38 ± 3.57); crab-eating mongoose (n = 48, RAI = 1.45 ± 0.33); yellow-throated marten (n = 16, RAI = 0.85 ± 0.37); golden jackal (n = 6, RAI = 0.64 ± 0.12); and northern tree shrew (n = 1, RAI = 0.42 ± 0.00), in SNP (Table 1, Figure 3). The results also identified wild avian species, including the red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus), pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), and anonymous bird species; livestock grazing; and human activity in SNP that were not listed here. Among the 15 different wild mammal species, seven were identified as common residents, each representing more than 1% of the total independent photographs (Table 1). The wild boar, barking deer, northern pig-tailed macaque, rhesus macaque, large Indian civet, and porcupine were the most frequently captured species, collectively accounting for >96.5% of all mammal images (Table 1). The species-accumulation curve reveals that wild mammal species were recorded from all of the 19 camera-trap stations deployed in SNP (Figure 3). The accumulation curve revealed a steady increase in cumulative wild species richness with the addition of new camera stations, eventually reaching a plateau. This trend indicated that the sampling effort using camera traps was sufficient to detect most of the wild mammal species present in SNP. The smoothed mean curve, along with the 95% confidence interval, further supports the representativeness and adequacy of the sampling design. As the study prioritized wild mammal detection, non-target species and other objects were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 2.

Camera trap identified wild mammal species in SNP: Asiatic black bear (i), wild boar (ii), northern pig-tailed macaque (iii), rhesus macaque (iv), barking deer (v), large Indian civet (vi), common palm civet (vii), and masked palm civet (viii). Leopard cat (ix), jungle cat (x), porcupine (xi), crab-eating mongoose (xii), yellow-throated marten (xiii), northern squirrel (xiv), and golden jackal (xv).

Figure 3.

Relative abundance and species-accumulation curve of wild mammals detected in SNP, Bangladesh. (A) Relative Abundance Index (RAI) of wild mammal species based on camera-trap detections, showing wild boar (Sus scrofa), barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak), and northern pig-tailed macaque (Macaca leonina) as the most frequently detected species. RAI was calculated as the number of independent detections per 100 trap nights. (B) Species-accumulation curve demonstrates the cumulative number of wild mammal species recorded with increasing number of camera-trap stations. The dashed black line represents the observed species accumulation, the solid purple line shows the smoothed mean, and the shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval. The curve approaches an asymptote, suggesting that a majority of wild mammal species present were captured by the current sampling effort.

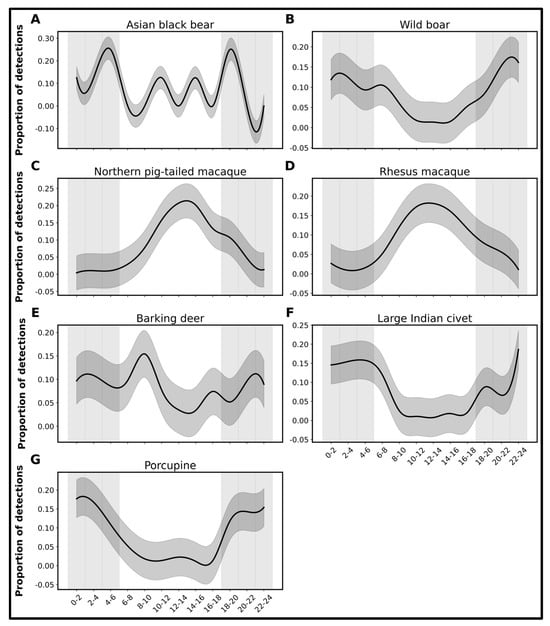

In addition, the study identified the daily activity patterns of wild mammals in SNP, showing that such mammals exhibited significant fluctuations in behavior and detection frequency across the day (Figure 4 and Figure S1). The diel activity pattern of the Asiatic black bear showed a distinct bimodal distribution of activity across the 24 h period. The Asiatic black bear exhibited distinct peaks in activity between midnight and early morning (around 2:00–6:00 a.m.), with an additional smaller peak observed during the evening hours (16:00–20:00 p.m.; Figure 4 and Figure S1). This indicates a predominantly nocturnal-to-crepuscular behavior, with the bears being most active under low-light conditions. In contrast, the activity significantly declines during daylight hours, particularly between 8:00 and 14:00, suggesting a strong avoidance of daytime movement. This pattern likely reflects an adaptive strategy to avoid human presence, reduce thermal stress, and optimize foraging efficiency in cooler periods. The relatively narrow confidence intervals during peak hours indicate consistent activity patterns, while broader intervals during midday reflect low and variable detection rates. The camera-trap data also reveal diverse diel activity patterns of other recorded mammalian species in SNP. Several species, including the wild boar, large Indian civet, common palm civet, masked palm civet, leopard cat, jungle cat, porcupine, and golden jackal, displayed nocturnal behavior, with peak activity occurring during night hours, particularly between 22:00 and 04:00 (Figure 4 and Figure S1). In contrast, the northern pig-tailed macaque, rhesus macaque, yellow-throated marten, and northern tree shrew were diurnally active, showing peak movement between 10:00 and 14:00 (Figure 4 and Figure S1). Some species, such as the barking deer and crab-eating mongoose, exhibited crepuscular or multimodal activity, being active during twilight periods or at multiple intervals throughout the day.

Figure 4.

Diel activity patterns of wild mammal species in SNP (A–G). Only species with >1% of detections are shown here, except for the Asian black bear (detection < 1%). Panels represent: (A) Asiatic black bear, (B) wild boar, (C) northern pig-tailed macaque, (D) rhesus macaque, (E) barking deer, (F) large Indian civet, and (G) porcupine. The y-axis represents the frequency of detected wild animal species (log transformed), while the x-axis indicates the 24 h time period divided into 2 h intervals.

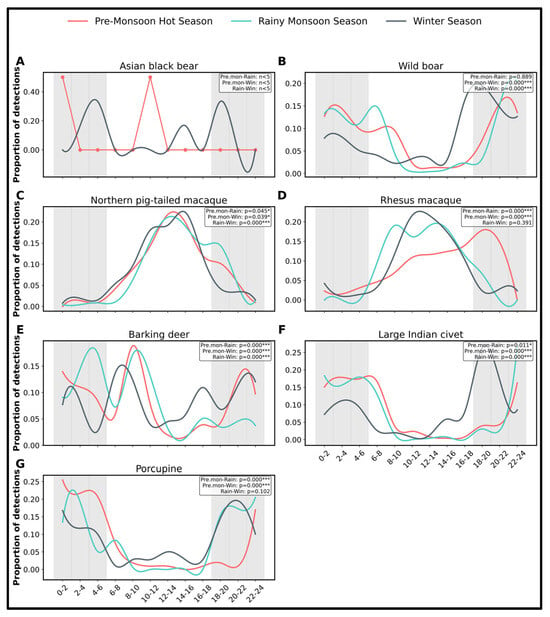

The line plots demonstrate distinct temporal and seasonal changes in diel activity patterns across species, with clear differences observed among the pre-monsoon hot season, rainy monsoon season, and winter season (Figure 5). Furthermore, circular statistical comparisons (Watson–Williams F-tests) revealed that the more frequently detected species (>1% of total detections) exhibited statistically significant differences in their diel activity distributions between seasons (Figure 5), indicating that seasonal shifts strongly influence daily activity rhythms within the mammal community. The Asiatic black bear shows limited (<1% of total detections) but confirmed seasonal presence, with activity detected in two out of the three seasons: pre-monsoon and winter. In the pre-monsoon, a single detection is evident in the 10:00–12:00 time bin. In contrast, there are no detections during the monsoon season, suggesting either seasonal movement, reduced activity, or lower detectability during periods of heavy rainfall. During the winter season, multiple detections were recorded, particularly between 2:00 and 6:00 and between 18:00 and 20:00 (Figure 5 and Figure S2), indicating a clear nocturnal activity pattern. This pattern suggests that the Asiatic black bear in the study area prefers cooler nighttime hours, especially in the winter, and is more likely to be detected during these periods. Its absence during the monsoon season may reflect either reduced mobility; shifting habitat use; or environmental factors such as vegetation cover and camera function. The bear’s scarce but seasonally consistent nocturnal activity reinforces its status as an elusive and low-density species, emphasizing the need for seasonal and habitat-specific monitoring to support the conservation of this endangered species in tropical forest landscapes.

Figure 5.

Seasonal activity patterns of wild mammal species recorded in SNP across the three major seasons (A–G). Only species with >1% of detections are shown here, except for the Asiatic black bear (detection < 1%). Panels represent: (A) Asiatic black bear, (B) wild boar, (C) northern pig-tailed macaque, (D) rhesus macaque, (E) barking deer, (F) large Indian civet, and (G) porcupine. Each panel illustrates the 24 h activity rhythm of a single species, plotted across 2 h time bins. Asterisks next to p-values in the top-right corner of each panel indicate significant differences in mean activity time between seasons based on the Watson–Williams circular test (p < 0.05 = * and p < 0.001 = ***). “n < 5” indicates that the species had fewer than five detections in one or both of the compared seasons, and therefore the Watson–Williams F-test could not be reliably performed. Pre.mon, pre-monsoon hot season; Rain, rainy monsoon season; and Win, winter season.

In regard to the other mammals’ activity during the pre-monsoon, species like the northern pig-tailed macaque and rhesus macaque showed consistently high activity across almost all-time bins, with peak frequencies during daylight hours (especially 10:00–14:00; (Figure 5 and Figure S2). Nocturnal species such as the wild boar, large Indian civet, masked palm civet, and porcupine also displayed strong activity from 0:00 to 6:00, and again after 20:00. In the monsoon season, overall detection frequencies declined, possibly due to reduced animal movement or lower camera detection rates during heavy rainfall. However, wild boars and macaques remained dominant, particularly between 6:00 and 14:00. Nocturnal species such as the wild boars, civets, porcupine, and mongoose continued their nighttime activity, though at lower intensities. During the winter season, the most significant activity peak occurred between 10:00 and 14:00, particularly for northern pig-tailed macaques and rhesus macaques, likely due to favorable daytime temperatures. Nocturnal species such as wild boars, porcupines, leopard cats, jungle cats, and civets continued to be active during nighttime intervals, reinforcing their nocturnal behavior across all seasons. Overall, the line plots emphasize species-specific diel activity adaptations to seasonal changes. Diurnal species tend to shift activity slightly toward warmer midday periods in winter, while nocturnal species maintain stable patterns across seasons.

4. Discussion

The present study highlighted the remarkable updated status of biodiversity of wild mammals in the PA of Northeastern Bangladesh, emphasizing its importance as a vital habitat for wildlife management and conservation. The study recoded a total of 15 wild mammals, wherein 4 species were small-sized mammals (<5 kg), namely the northern tree shrew, jungle cat, common palm civet, and masked palm civet; 7 species were medium-sized mammals (5–25 kg), namely the crab-eating mongoose, yellow-throated marten, porcupine, leopard cat, large Indian civet, golden jackal, and both macaque species (i.e., rhesus macaque and northern pig-tailed macaque); and 3 species were large-sized mammals (over 25 kg), namely the Asiatic black bear, wild boar, and barking deer in SNP. In this study, the detection of the Asiatic black bear in SNP marks a significant and novel finding, as this is the first documented evidence of the species’ presence in this PA of Sylhet to date. A recent camera-trap study in the Rajkandi Reserve Forest within the Sylhet region of Northeastern Bangladesh confirmed the presence of the Asiatic black bear with nocturnal or crepuscular activity; however, the bear was not detected in SNP [41].

Our study provides the first camera-trap evidence confirming the presence of the Asiatic black bear in SNP, a finding not previously documented. The current study demonstrated that the Asiatic black bear showed a bimodal activity pattern, with prominent peaks from midnight to early morning and during twilight hours, indicating nocturnal-to-crepuscular behavior and that it is seasonally active in the pre-monsoon and late winter periods. Previous studies conducted a year-round camera trapping in or around SNP, but none of them had the evidence that the Asiatic black bear was present in SNP [20,21,22,23,24]. Therefore, their non-detection cannot be attributed to monsoon-specific camera-trapping limitations. Instead, the earlier absence of the Asiatic black bear may reflect the species’ low population density, the researcher’s limited sampling intensity, or the researchers’ methodological constraints, rather than seasonal inactivity. Contrarily, it is also possible that the Asiatic black bears detected in our study are transient or shifting bears originating from adjoining forest habitats across the India–Bangladesh border. As we know, SNP lies adjacent to continuous PA patches in the neighboring country of India. As a result, the cross-border movements of the Asiatic black bear may account for the low and irregular detection rates observed in SNP. Another possible reason that may be behind the low and irregular detection rates is that the Asiatic black bear may occasionally enter the SNP area during periods of abundant resources and enhanced foraging opportunities. Once these resources diminish, Asiatic black bears may return to their core habitat across the border. Nonetheless, monsoon weather conditions, including dense vegetation, huge flooding, and reduced movement along trails, could also lower the detection probability in heavily disturbed forest patches in SNP. Zahoor et al. [9] reported that Asiatic black bears exhibited peak activity during the summer months, especially in July and August, with reduced activity in spring and autumn, and complete inactivity from December to March due to hibernation in Machiara National Park, Pakistan. Another study reported that bears were generally inactive from late December to early April in Taipinggou National Nature Reserve and Tangjiahe National Nature Reserve, China, where fresh droppings of an Asiatic black bear were discovered in March [42,43]. In SNP, the comparatively moderate winter climate and abundance of food supplies may lessen the Asiatic black bear’s requirement for lengthy hibernation, allowing for occasional winter activity compared to other places. Furthermore, local ecological constraints such as human disturbance, habitat features, and interspecific competition may have an impact on Asiatic black bear temporal activity and seasonal behavior across geographic regions.

Our investigation also reported another 14 wild mammals including that wild boar was the most often observed wild mammal, underlining its ecological importance in SNP. On the other hand, northern pig-tailed macaques, barking deer, and rhesus macaques are all present in moderate abundance, indicating that the forest supports a varied range of herbivorous and frugivorous species. In this study, the presence of carnivores and omnivores, such as the large Indian civet, masked palm civet, and crab-eating mongoose, indicates a healthy food chain. Furthermore, the existence of rare species such as the yellow-throated marten, leopard cat, and golden jackal suggests that the ecosystem of SNP has a high niche variety and complicated trophic interactions [10]. However, compared with the previous studies, the current findings suggested a reduction of several wild mammals once documented in SNP, including the Bengal slow loris, Assamese macaque, and western hoolock [10,44,45]. Importantly, our investigation was unable to identify the dhole that was previously recorded by Zakir et al. [24]. The absence of these wild mammals in our camera-trap surveys raises concerns about their current state and conservation outlook. This gap may be attributed to habitat degradation, hunting, poaching, and various human disturbances, which were recorded during our investigation that are consistent with the statement of previous reports [20,21,46]. In addition, our correlation analysis further confirmed that human disturbances significantly influence the activity patterns of wild animals within the SNP protected area (Figure S1).

In the other areas of the Sylhet division, a total of 22 medium- and large-sized mammal species were documented in the Patheria Hill Reserve, including key wild mammal species such as the fishing cat, oriental small-clawed otter, hog badger, and Phayre’s langur. Previous studies have reported that the transboundary hilly forest of Patheria Hill Reserve, bordering India, was the home of a wide range of wild animal species, including Asian elephants, western hoolock gibbons, Chinese pangolins, and other primate species [47,48]. Other studies reported that a total of 49 species of wild animal species, primarily small- and medium-sized mammals such as the Bengal slow loris, Assamese macaque, northern pig-tailed macaque, Phayre’s leaf monkey, capped langur, western hoolock, fishing cat, Eurasian otter, binturong, and Indian pangolin, were documented as being present in the northeastern region of Sylhet [10,44,45]. Recently, a total of 17 small- and medium-sized wild mammals, including the northern pig-tailed macaque, barking deer, rhesus macaque, leopard cat, jungle cat, large Indian civet, masked palm civet was reported as being present in SNP [24]. Our investigation also found the majority of the wild mammals previously recorded, confirming the species’ long-term presence and persistence in SNP. This consistency in species occurrence across temporal scales not only improves the reliability of previous data, but it also shows a minimum level of ecological stability inside the park.

5. Conclusions

The current study provides a vital insight into the updated status of biodiversity and wildlife activity patterns in the PA of Northeastern Bangladesh. Notably, our study provided the first camera-trap evidence of the Asiatic black bear in SNP of Bangladesh, highlighting a significant extension of its known range within the Sylhet region. The Asiatic black bear demonstrated predominantly nocturnal and crepuscular activity, with clear seasonal variation, being active during pre-monsoon and winter but absent during the monsoon season. On the other hand, the diverse activity patterns of other identified wild mammals reflected the different behavioral and habitat adaptations. Collectively, the present study offers critical baseline data for informed conservation planning to protect biodiversity in SNP and similar fragmented habitats. Our findings suggest the important need for ongoing and regular monitoring measures to comprehensively evaluate and mitigate the impact of anthropogenic activities on wildlife and their habitats.

Conservation Implications and Recommendations

The findings of the current study have several significant implications for wildlife conservation in SNP and other PAs in Bangladesh. The first-identified Asiatic black bear using camera traps in SNP emphasizes the vast ecological importance of that park in supporting rare and elusive wild mammals. This discovery calls for the establishment of platforms for existing wildlife monitoring strategies through the deployment of camera traps and other non-invasive tools to enhance the documentation and protection of biodiversity. The activity pattern analysis of wild mammals revealed the predominantly nocturnal-to-crepuscular behavior, where seasonal variations provided a valuable basis for designing adaptive conservation strategies. Additionally, the absence of the few mammals during the specific seasons highlighted the potential challenges in detectability or shifts in habitat use that could be needed for further investigation. The study suggests the engagement of local communities through awareness programs, participatory conservation practices, and alternate sustainable livelihood options that could enhance stewardship and reduce human–wildlife conflict. Our study also indicated that integrating the outcomes of this research into national biodiversity conservation forums and policymaking is essential. Furthermore, documenting the presence and activity patterns of wild mammals, particularly globally vulnerable species like the Asiatic black bear, contributes to Asia–Pacific conservation priorities and enhances transboundary efforts for biodiversity protection under global view.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ecologies6040083/s1, Figure S1: Diel activity patterns of all wild mammal species in SNP. The images demonstrate the activity patterns of wild animal species that were illustrated based on camera-trap data from SNP. The y-axis represents the frequency of detected wild animal species (log transformed), while the x-axis indicates the 24 h time period divided into 2 h intervals. Figure S2: Seasonal activity patterns of all wild mammal species recorded in SNP across the three major seasons. Each panel represents the 24 h activity rhythm of a single species, plotted across 2 h time bins. Asterisks next to p-values in the top-right corner of each panel indicate significant differences in mean activity time between seasons based on the Watson–Williams circular test (p < 0.05 = *, p < 0.01 = **, p < 0.001 = ***). “n < 5” indicates that the species had fewer than five detections in one or both of the compared seasons, and therefore the Watson–Williams F-test could not be reliably performed. Pre.mon, pre-monsoon hot season; Rain, rainy monsoon season; and Win, winter season.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.R.S.; methodology, R.A.R.S.; software, M.M.I.; validation, R.A.R.S. and M.M.R.; formal analysis, R.A.R.S., M.M.I. and M.M.R.; investigation, R.A.R.S., M.M.R. and H.D.; data curation, R.A.R.S., M.M.R. and M.M.I.; visualization, M.M.I., writing—original draft preparation, R.A.R.S. and M.M.R.; writing—review and editing, R.A.R.S., M.M.R., M.M.I., H.D. and J.M.; supervision, J.M.; project administration, J.M.; funding acquisition, J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Graduate School of Agricultural Science Research Competitiveness Enhancement Support Program of Gifu University, Japan, and the THERS Make New Standards Program for the Next-Generation Researchers of Gifu University, Japan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our research does not involve invasive or experimental procedures conducted on live animals. This study adheres strictly to observational or non-invasive methodologies, and no animal was harmed or subjected to experimental manipulation during the research. According to the ethical guidelines and regulations established by Gifu University, research of this nature does not fall within the scope of projects requiring formal ethical review or approval by the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) or equivalent bodies.

Informed Consent Statement

All essential experiments using camera traps were carried out in Satchari National Forest with a written order from the Deputy Chief Conservator of Forests, Bangladesh Forest Department, Dhaka, Bangladesh (office order: 22.01.0000.004.04.21.2.23.232; date: 14 March 2024).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful for the enormous support of forest personnel of the Satchari range and the Bangladesh Forest Department for their cooperation as we carried out our entire experiments in SNP.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mori, E.; Bagnato, S.; Serroni, P.; Sangiuliano, A.; Rotondaro, F.; Marchianò, V.; Cascini, V.; Poerio, L.; Ferretti, F. Spatiotemporal mechanisms of coexistence in a European mammal community. J. Zool. 2020, 310, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, N.; Schlindwein, X.; Gottschalk, T.K.; Dvorak, J.; Randler, C. Seasonal variation in the activity pattern of red squirrels and their predators. Mamm. Res. 2024, 69, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucera, T.E.; Barrett, R.H. A history of camera trapping. In Camera Traps in Animal Ecology; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, S.; Volpe, J.; Heim, N.; Paczkowski, J.; Fisher, J. Move to nocturnality is not a universal trend in carnivore species on disturbed landscapes. Oikos 2020, 129, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, K.M.; Hojnowski, C.E.; Carter, N.H.; Brashares, J.S. The influence of human disturbance on wildlife nocturnality. Science 2018, 360, 1232–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.I.A. Helarctos malayanus. In Red List of Bangladesh, Volume 2: Mammals; IUCN: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015; Available online: http://www.iucn.org/bangladesh (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Naher, H. Melursus ursinus. In Red List of Bangladesh, Volume 2: Mammals; IUCN: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sathyakumar, S.; Sharma, L.; Charoo, S. Ecology of Asiatic Black Bear in Dachigam National Park; Wildlife Institute of India: Dehradun, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zahoor, B.; Ahmad, B.; Minhas, R.A.; Awan, M.S. Damages caused by black bear in Moji Game Reserve. Pak. J. Zool. 2021, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Bangladesh. Red List of Bangladesh: Volume 2: Mammals; IUCN Bangladesh Country Office: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015; p. xvi+232. [Google Scholar]

- Venter, O.; Sanderson, E.W.; Magrach, A.; Allan, J.R.; Beher, J.; Jones, K.R.; Possingham, H.P.; Laurance, W.F.; Wood, P.; Fekete, B.M.; et al. Global terrestrial human footprint maps for 1993 and 2009. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theobald, D.M.; Zachmann, L.J.; Dickson, B.G.; Hale, R.L.; Sayler, K.L.; Goetz, S.J. A global map of urbanization. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- McShea, W.J.; Hwang, M.-H.; Liu, F.; Li, S.; Lamb, C.; McLellan, B.; Morin, D.J.; Pigeon, K.; Proctor, M.F.; Hernandez-Yanez, H.; et al. Is the delineation of range maps useful for monitoring Asian bears? Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 35, e02068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.K.; Augustine, B.C.; Morin, D.J.; Pigeon, K.; Boulanger, J.; Lee, D.C.; Bisi, F.; Garshelis, D.L. The occupancy–abundance relationship and sampling designs using occupancy to monitor populations of Asian bears. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 35, e02075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Uddin, M.; Aziz, M.A.; Bin Muzaffar, S.; Chakma, S.; Chowdhury, S.U.; Chowdhury, G.W.; Rashid, M.A.; Mohsanin, S.; Jahan, I.; et al. Status of bears in Bangladesh: Going, going, gone? Ursus 2013, 24, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Amin, A.S.M.R.; Sarker, S.K. National report on alien invasive species of Bangladesh. In Invasive Alien Species in South-Southeast Asia; GISP: Cape Town, South Africa, 2003; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Waseem, M.; Teng, M.; Ali, S.; Ishaq, M.; Haseeb, A.; Aryal, A.; Zhou, Z. Human–Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus) interactions in the Kaghan Valley, Pakistan. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 30, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Fuller, R.A.; Rokonuzzaman, M.; Alam, S.; Das, P.; Siddika, A.; Ahmed, S.; Labi, M.M.; Chowdhury, S.U.; Mukul, S.A.; et al. Insights from citizen science reveal priority areas for conserving biodiversity in Bangladesh. One Earth 2023, 6, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-WCMC. Protected Area Profile for Bangladesh from the World Database of Protected Areas; UNEP-WCMC and IUCN: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Available online: www.protectedplanet.net (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Aziz, M.A. Notes on the status of mammalian fauna of the Lawachara National Park, Bangladesh. Ecoprint 2011, 18, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeroz, M.M.; Hasan, M.K.; Khan, M.M.H. Biodiversity of Protected Areas of Bangladesh. Vol. I: Rema-Kalenga Wildlife Sanctuary; BioTrack/Arannayk Foundation: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, A.Z.M.M.; Chowdhury, S.H.; Islam, M.A. Biodiversity of Satchari National Park; IUCN Bangladesh Country Office: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Akash, M.A.; Zakir, T.; Mahjabin, R.; Debbarma, R.; Zahura, F.T.; Minu, M.M.R.; Khan, Z. Camera trapping insights into leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) movement in eastern Bangladesh. Mammal Study 2021, 46, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Zakir, T.; Debbarma, H.; Mahjabin, R.; Debbarma, R.; Khan, Z.; Minu, M.M.R.; Zahura, F.T.; Akash, M.A. Are northeastern forests of Bangladesh empty? Mammal Study 2021, 46, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, M.K.; Rahman, M.M.; Uddin, M.Z.; Hassan, M.A. Angiosperm flora of Satchari National Park, Habiganj, Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Plant Taxon. 2011, 18, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukul, S.A.; Uddin, M.B.; Tito, M.R. Study on the status and various uses of invasive alien plant species in and around Satchari National Park, Sylhet, Bangladesh. Tiger Paper 2006, 33, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Shawon, R.A.R.; Rahman, M.M.; Iqbal, M.M.; Russel, M.A.; Moribe, J. Diversity and dynamics of small and medium mammals in Pittachhara Forest. Animals 2024, 14, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.A.; McCarthy, K.P.; McCarthy, J.L.; Faisal, M.M. Application of multi-species occupancy modelling to assess mammal diversity in northeast Bangladesh. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 25, e01385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Suzuki, A.; Uddin, M.S.; Motalib, M.; Chowdhury, M.R.K.; Hamza, A.; Aziz, M.A. Presence of medium and large mammals in Patharia Hill Reserve. J. Threat. Taxa 2023, 15, 23283–23296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.J.; Han, S.H.; Kim, K.Y.; Hong, S.; Park, Y.C. Relative abundance of mammals using camera traps in Jangsudae, Seoraksan National Park. Mammal Study 2023, 48, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, M.J.; Sanjayan, M.; Lowenstein, J.; Nelson, A.; Jeo, R.M.; Crooks, K.R. Remote camera-trap methods reveal impacts of rangeland management on Namibian carnivore communities. Oryx 2007, 41, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.G.; Kinnaird, M.F.; Wibisono, H.T. Crouching tigers, hidden prey. Anim. Conserv. 2003, 6, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, X.; Kays, R.; Ding, P. Minimum trapping effort for detecting terrestrial animals. Peer J. 2014, 2, e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Waskom, M.L. Seaborn: Statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.M.; Billah, M.M.; Haider, M.N.; Islam, M.S.; Payel, H.R.; Bhuiyan, M.K.A.; Dawood, M.A.O. Seasonal distribution of phytoplankton community in a subtropical estuary of southeastern Bangladesh. Zool. Ecol. 2017, 27, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.S.; Williams, E.J. Construction of significance tests on the circle and sphere. Biometrika 1956, 43, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GADM. Database of Global Administrative Areas, Version 4.1. 2023. Available online: https://gadm.org (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Akash, M.; Debbarma, H.; Ahmed, S.; Chowdhury, A.B.; Zakir, T.; Sarafat, K.N.M.D.; Sharma, S. Assessing the conservation status of and challenges facing Asiatic black bears and Malayan sun bears in Bangladesh. Oryx 2025, 59, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D.; Jiang, M.; Teng, Q.; Qin, Z.; Hu, J. Ecology of the Asiatic black bear in Sichuan, China. Mammalia 1991, 55, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seryodkin, I.V.; Kostyria, A.V.; Goodrich, J.M.; Miquelle, D.G.; Smirnov, E.N.; Kerley, L.L.; Quigley, H.B.; Hornocker, M.G. Denning ecology of brown and Asiatic black bears. Ursus 2003, 14, 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, J.K.; Biswas, S.R.; Islam, M.S.; Rahman, O.; Uddin, S.N. Biodiversity of the Satchari Reserve Forest, Habiganj; IUCN Bangladesh Country Office: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.M.H. Photographic Guide to the Wildlife of Bangladesh; Arannayk Foundation: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Akash, M.; Zakir, T. Appraising carnivore (Mammalia: Carnivora) studies in Bangladesh from 1971 to 2019: Bibliographic retrieves, trends, biases, and opportunities. J. Threat. Taxa 2020, 12, 17105–17120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, N.R.; Choudhury, P. Conserving wildlife in Patharia Hills Reserve Forest, Assam. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 10, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, N.R.; Choudhury, P.; Ahmad, F.; Ahmed, R.; Ahmad, F.; Al-Razi, H. Habitat suitability of the Asiatic elephant in the transboundary Patharia Hills. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 6, 1951–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).