Abstract

Mitochondria serve as central hubs of cellular metabolism, integrating catabolic and anabolic pathways through the controlled exchange of metabolites across their membranes. Although mitochondrial transport of several metabolites has been well documented, the mechanisms underlying the trafficking of fumarate, glutamine, and phosphoenolpyruvate as well as the role of the mitochondrial pyruvate kinase remain insufficiently represented in modern biochemistry textbooks. Here, we revisit the biochemical evidence supporting specific transport activities for these metabolites, discuss their physiological roles in major metabolic pathways, and highlight how foundational experimental studies have been overlooked in contemporary literature. Re-examining these mechanisms provides new insight into the dynamic interplay between mitochondrial function, cytosolic metabolism, and overall cellular homeostasis.

1. Introduction

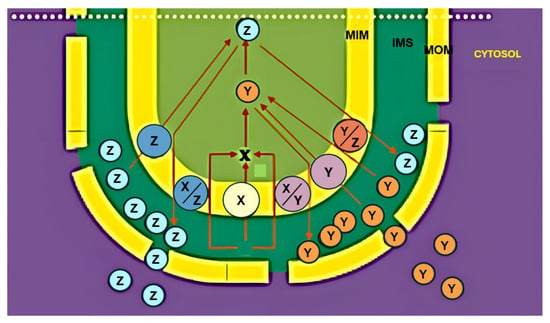

Mitochondria are highly compartmentalized organelles in which numerous metabolic reactions occur, requiring the regulated uptake of substrates from the cytosol and the export of products formed within the matrix [1]. Foundational studies conducted with isolated and coupled mitochondria have led to a general paradigm of mitochondrial metabolite transport as summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The transport paradigm. The theoretical transport paradigm is reported.

According to this model, metabolite translocation across the mitochondrial membranes can be described as a two-step process.

During the anaplerotic phase, substrates as X are imported into the matrix to replenish the intermediates of the Krebs cycle (TCA) that are consumed in other biosynthesis, such as amino acid synthesis.

In the subsequent cataplerotic phase, these intermediates generated within the matrix are removed for use in other metabolic pathways, typically in exchange for further substrate uptake. A given metabolite X may enter the matrix via uniport, proton-compensated symport, or antiport with non-carbon compounds. Once metabolized to generate products Y and Z, continued uptake of X may proceed by antiport with one of these newly formed metabolites.

Exported products may either remain in the cytosol or re-enter the organelle through alternative carriers, thereby establishing a tight coupling between electron transport, metabolite exchange, and cytosolic metabolism. Notably, no major exceptions to this paradigm have been reported to date.

It should be noted that despite its conceptual importance, the functional contribution of the intermembrane space (IMS) to metabolite distribution remains insufficiently explored. For example, whether metabolites newly exported from the matrix equilibrate rapidly with cytosolic concentrations is still unclear and rarely discussed in textbooks.

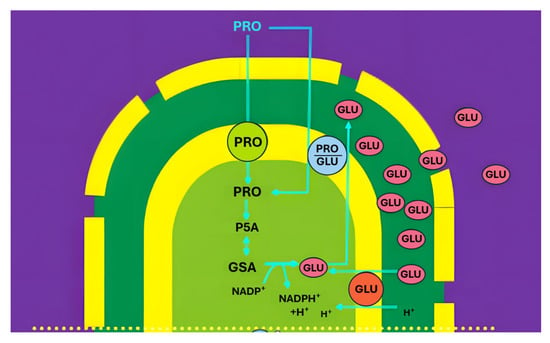

Evidence for the presence of distinct IMS pools was provided in a study investigating the energy dependence of the proline/glutamate antiporter in rat kidney mitochondria [2]. The exchange was shown to be driven by the electrochemical proton gradient, with a ΔΨ-dependent proline/glutamate translocator acting together with a ΔpH-dependent glutamate/OH− carrier. High-performance liquid chromatography revealed a discrete glutamate pool in the IMS (Figure 2), demonstrating that metabolites exported from the matrix may accumulate transiently in this compartment.

Figure 2.

Organization of proline/glutamate antiport. Abbreviations: PRO, proline; GLU, glutamate; GSA, glutamate semialdehyde: PSC, pyrroline-5-carboxylate; m.i.m. mitochondrial inner membrane; GDH, Glu-DH.

On the other hand, a variety of static approaches to investigate the role of mitochondrial transport in energy metabolism have been used in recent decades. In this case, a detailed description of the molecules involved in transport and metabolism is made, but no/minimal information on how certain transports and reactions can play a role in the metabolic pathways (see [3]).

These considerations underscore the need to re-evaluate the integration of mitochondrial transport within major metabolic pathways. In this regard, glycolysis (including mitochondrial shuttles and the transport/metabolism of oxaloacetate and L-lactate) and gluconeogenesis (involving L-lactate, D-lactate, as a glucose precursor), have already been investigated (for refs. see [1,3,4]). In contrast, other pathways remain insufficiently addressed, including the urea and purine nucleotide cycles (especially the fate of cytosolic fumarate), glutamine bioenergetics, and fatty acid synthesis (notably the roles of phosphoenolpyruvate and mitochondrial pyruvate kinase). These areas merit renewed investigation in light of the evolving understanding of mitochondrial transport and its integration with cellular metabolism.

2. Fumarate Transport in Mitochondria

A long-standing question in the study of the urea cycle concerns the metabolic fate of fumarate generated in the cytosol. Fumarate is released into the cytoplasm not only during the urea and purine nucleotide cycles but also during the metabolism of several amino acids. Yet its subsequent handling, particularly whether mitochondria play a direct role in its metabolism, has been insufficiently described in standard biochemistry textbooks.

Although the presence of both mitochondrial and cytosolic fumarase isoforms [5] theoretically allows fumarate to be transported across the inner mitochondrial membrane after conversion to malate or related metabolites, and although, because of its trans configuration, fumarate has traditionally been considered non-permeant across the inner mitochondrial membrane since the discovery of mitochondrial metabolite carriers [6], several mitochondrial transport activities directly involving fumarate have been reported.

The first experimental evidence for mitochondrial fumarate uptake was provided in 1978, when a fumarate/malate exchange system was identified in rat heart mitochondria. Subsequent investigations revealed the presence of two distinct transport systems in rat liver mitochondria: a fumarate/malate antiporter and a fumarate/phosphate (Pi) antiporter. Additional studies showed that fumarate is also taken up by rat brain mitochondria via the dicarboxylate carrier. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that directed fumarate transport occurs in multiple tissues and is mediated by specific carrier proteins (for ref. see [1]).

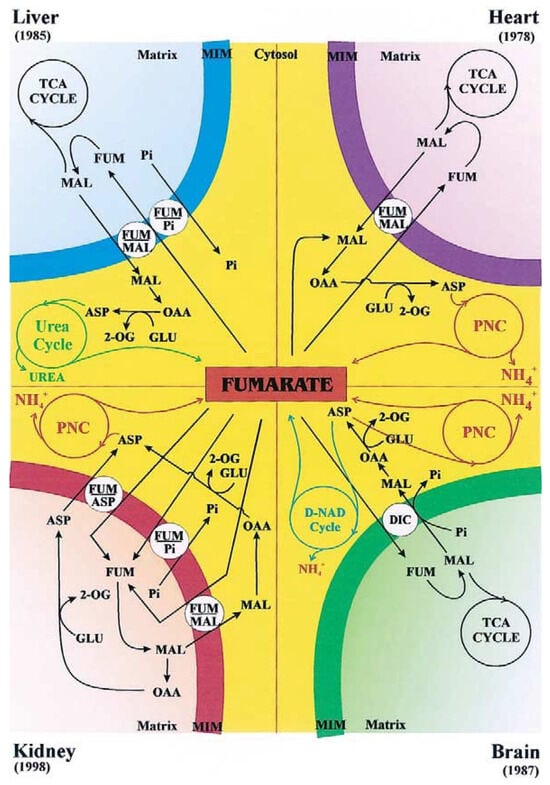

Figure 3 (from [1]) summarizes the known fumarate transport pathways in mitochondria from liver, heart, kidney, and brain, and highlights the specific carriers involved in each tissue type. The fumarate/malate exchange is thought to play a key role in providing cytosolic malate, which supports gluconeogenesis and contributes to the closure of the urea cycle through aspartate formation via malate dehydrogenase and aspartate aminotransferase. Conversely, fumarate uptake in exchange for phosphate represents an anaplerotic route for carbon replenishment in the TCA cycle, thereby linking amino acid catabolism to oxidative phosphorylation. In rat brain mitochondria, fumarate addition induces a hyperbolic efflux of malate, further supporting its role in mitochondrial–cytosolic metabolite exchange. A similar fumarate/malate antiporter has also been demonstrated in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria [7]. The physiological role of the novel fumarate/malate translocator still remains a matter of speculation: we could assume that this carrier could be involved in the cytosolic purine biosynthesis and in the arginine metabolism (see also Figure 4).

Figure 3.

From [1]. The fumarate transport in rat liver, heart, kidney and brain mitochondria. The fumarate transport in certain pathways is described, as catalyzed by the fumarate carriers. Main abbreviations: ASP, aspartate; FUM, fumarate; GLU, glutamate; MAL, malate, 2-OG, 2-oxoglutarate; PNC; purine nucleotide cycle; TCA cycle, tricarboxylate cycle.

Figure 4.

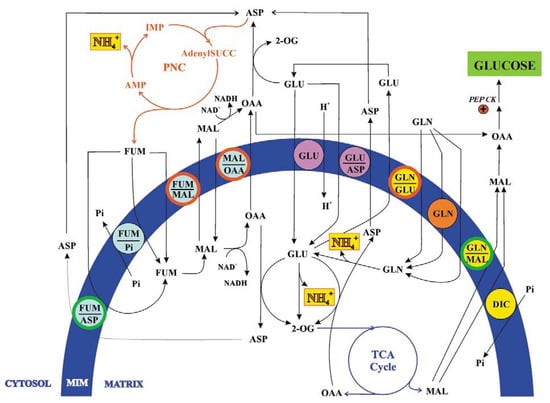

From [1]. The fumarate and glutamine transport in kidney ammoniogenesis. For details see the text. Main abbreviations: AdenylSUCC, adenilsuccinate; GLN, glutamine; PEP CK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase.

It is worth noting that the study entitled: “Identification of mitochondrial carriers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae” [8] does not cite this work, nor earlier investigations that had reported mitochondrial permeability to fumarate approximately two decades earlier [see [1]]. A similar lack of reference to these studies can also be observed in a preceding report describing the identification of the gene encoding the succinate/fumarate transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria [9].

In rat kidney mitochondria, both under normal and acidotic conditions, fumarate, whether generated in vitro from externally added adenyl-succinate via adenyl-succinate lyase or supplied exogenously, was shown to enter the matrix in exchange for malate or aspartate [10]. These findings highlight that fumarate transport systems are not uniform across tissues but instead reflect the specific metabolic demands of each organ.

It is remarkable that nearly a century after the discovery of the urea cycle, the fate of cytosolic fumarate remains largely overlooked, not only in biochemistry textbooks, but even in the recent literature intended to clarify metabolic pathways. In one such article, the author states: “Similar to the urea cycle, the carbon skeleton of aspartate leaves the purine nucleotide cycle as fumarate in the cytosol. Even if the role of this compound is to perform the anaplerotic function of replenishing the citric acid cycle by being converted to oxaloacetate, to do so it must first enter the mitochondrial matrix. Because the mitochondrial inner membrane does not possess a transporter for fumarate, it must first be converted to malate in the cytosol” [11].

In another paper reporting multiple functions of fumarate [12], metabolite traffic across the mitochondrial membrane is described as “an essential process coordinating both mitochondrial and cytosolic metabolism… our coverage of the entire mitochondrial family remains incomplete and further investigations are required in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of organic acid transport. It is well established that the exchange of TCA cycle intermediates, such as fumarate, across the mitochondrial membrane connects the TCA cycle with diverse metabolic processes including gluconeogenesis, the glyoxylate cycle, and the biosynthesis of amino acids and nucleic acids”. Yet, fumarate transporters are not discussed in this paper, nor in another study examining the role of fumarate in cancer [13]. The authors note: “The phenomenon of enhanced glycolysis in tumors has been acknowledged for decades, but biochemical evidence to explain it is only just beginning to emerge… A significant hint as to the triggers and advantages of enhanced glycolysis in tumors was supplied by the recent discovery that succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and fumarate hydratase (FH) are tumor suppressors… Further steps forward showed that the substrates of SDH (succinate dehydrogenase) and FH, (fumarate hydratase) succinate and fumarate, respectively, can mediate a ‘metabolic signaling’ pathway. Succinate or fumarate, which accumulate in mitochondria owing to the inactivation of SDH or FH, leak out to the cytosol, where they inhibit a family of prolyl hydroxylase enzymes”. However, no mechanism is provided to explain how succinate and fumarate “leak out to the cytosol”.

Similarly, in a review describing major changes in the expression of urea-cycle enzymes and metabolites in different cancers at various stages [14], the generation of fumarate is proposed to integrate the urea cycle with the TCA cycle. Fumarate is suggested to enter mitochondria, yet no indication is given of the carrier(s) that would mediate such transport reported also in Figure 3.

In another paper discussing the “rewiring” of urea-cycle metabolism in cancer to support anabolism [15], two schemes illustrating “urea cycle enzymes, substrates and intermediates” depict mitochondrial uptake of fumarate, again without identifying the corresponding transporter(s). The same omission appears in [16].

Finally, among the “Key Facts” listed in a paper devoted to fumarate as “Metabolite of the Month” [17], it is stated that “although fumarate is present in different cellular compartments, its transporters have not yet been identified in mammals, unlike in plants and bacteria”. This statement epitomizes the enduring enigma surrounding fumarate transport in mammalian mitochondria and highlights the need for renewed biochemical and physiological investigations into this overlooked aspect of intermediary metabolism.

3. Glutamine Transport in Mitochondria

The mitochondrial transport and metabolism of glutamine, extensively investigated throughout the last century, have been comprehensively summarized in earlier papers [1,18]. A pivotal study published in 1994 examined glutamine transport in both normal and acidotic rat kidney mitochondria (RKM) using radiolabeled substrates and spectroscopic approaches under conditions permitting active glutamine metabolism [19].

As illustrated in Figure 3, glutamine crosses the inner mitochondrial membrane through three distinct transport mechanisms: a glutamine uniport, operative exclusively under acidic conditions; a glutamine/glutamate antiporter; and a glutamine/malate antiporter, both active in mitochondria from normal and acidotic rats. All transport systems satisfied the classical criteria for carrier-mediated translocation established in [1].

Detailed kinetic analyses revealed that the uniport and both antiport systems differ in their Km and Vmax values, pH and temperature dependencies, and sensitivity to specific transport inhibitors. Together, these observations demonstrated the presence of five distinct glutamine translocators, whose differing activities align with the physiological requirements of renal ammoniogenesis. Under conditions of low ammonia demand, glutamate produced from intramitochondrial glutamine catabolism may exit the matrix. When ammonia production must increase, additional glutamate undergoes oxidative deamination by glutamate dehydrogenase, and malate derived from the tricarboxylic acid cycle is exported, likely to support renal gluconeogenesis.

Despite robust experimental evidence, the later literature has frequently overlooked these transport systems. For example, a widely cited review on glutaminase regulation and glutamine metabolism [20] mentions only a single glutamine uniporter. Another review addressing the role of glutamine in human carbohydrate metabolism [21] highlights glutamine as an important gluconeogenic precursor yet does not discuss mitochondrial involvement or the glutamine/malate antiporter responsible for exporting malate, a key intermediate in renal gluconeogenesis.

Equally surprising is the statement found in a paper published five years ago [22]: “The identification of the glutamine transporter comes at an exciting time in understanding the transport of molecules across membranes. While older methods relied on relatively low-throughput membrane-reconstitution studies or genetic screens in yeast, new techniques such as insertional mutagenesis now permit the identification of cell-surface and mitochondrial transporters”.

The authors seem to disregard the long-established history of mitochondrial metabolite transport studies, in which isolated coupled mitochondria played a central role. Techniques used for decades after the discovery of mitochondrial carriers, described in [3], are dismissed as “old”, despite their effectiveness in studying metabolic transport. The situation is comparable to a virtuoso violinist rejecting Stradivari or Guarneri del Gesù instruments in favor of newly built ones.

Other reviews continue to perpetuate the misconception that mitochondrial glutamine transport remains poorly characterized. In [23], the importance of renal gluconeogenesis under ketogenic or diabetic conditions is emphasized, yet the mechanistic basis for glutamine-derived carbon export is not addressed. In [24], it is claimed that glutamine metabolic activity interferes with the characterization of mitochondrial carriers; however, as clarified in [3], the original work in [19] directly detected export products in intact mitochondria, overcoming such limitations.

Even in recent years, statements persist that the structural and functional characterization of mitochondrial glutamine transporters is still “at infancy” [25], or that “the network of proteins involved in glutamine flux to the mitochondrial matrix is still underneath” [26]. These claims overlook the experimentally demonstrated existence of five glutamine transport systems, knowledge that could provide critical insight into cancer cell metabolism and metabolic reprogramming.

A paper examining metabolic reprogramming in cancer [27] briefly mentions metabolite trafficking but provides no details regarding the transporters required for glutamine-dependent mitochondrial functions. Notably, the authors identify 2-oxoglutarate, rather than malate, as the precursor of phosphoenolpyruvate in renal gluconeogenesis, in contradiction with established biochemical pathways. The same article further states that “the mitochondrial glutamine transporter has long been unknown”, despite the earlier characterization of at least five such transport systems.

Moreover, a recent study on glutamine transport and prostate cancer radiosensitivity [28] focuses exclusively on plasma membrane transporters (SLC1A5, SLC7A5, SLC38A1), without addressing the mitochondrial carriers essential for glutamine utilization, even though disruption of glutamine flux is central to the study’s conclusions. Indeed, a number of papers aimed at elucidating the role of glutamine in cancer metabolism continue to overlook glutamine transport within mitochondria [29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

Collectively, these omissions highlight a persistent gap between classical biochemical knowledge and contemporary interpretations of glutamine metabolism. Renewed attention to established transport mechanisms may substantially advance our understanding of mitochondrial function in renal physiology, cancer metabolism, and nutrient signaling.

4. Phosphoenolpyruvate Transport and Mitochondrial Pyruvate Kinase

During a biochemistry lecture, a debate arose concerning two key principles relevant to the field: the principle of molecular economy in living organisms, as formulated by Albert Lehninger (i.e., the principle of maximum economy of parts and processes), and Le Chatelier’s principle, which states that “if a dynamic equilibrium is disturbed by changing the conditions, the position of equilibrium shifts to counteract the change”.

A student then posed the following question: “Why should ATP continue to be formed during glycolysis under high-energy cellular conditions? Specifically, why should ATP be generated in the pyruvate kinase (PK) reaction when the cell is already energy-rich? Would it not be more consistent with the principles mentioned above for phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to enter the mitochondria instead, perhaps in exchange for citrate, which is required in the cytosol for fatty-acid synthesis.

Another student followed up by asking what reactions PEP might undergo inside rat kidney mitochondria, given the apparent absence of intramitochondrial PEP-metabolizing enzymes in addition to PEP carboxykinase. Could mitochondria possess their own pyruvate kinase?

Indeed, PEP transport into and out of mitochondria received limited attention during the last century. However, the first indication that PEP can cross the mitochondrial membrane dates back to 1967, when Gamble and Mazur demonstrated that citrate addition to rabbit liver mitochondria led to the appearance of PEP in the extramitochondrial space [36]. The authors suggested that this observation could reflect a selective permeability of the mitochondrial membrane to PEP. Subsequent studies by Drahota et al. [37] and Wiese et al. [38] confirmed that PEP is able to enter mitochondria.

A significant advance in the field occurred in the first decade of the twenty-first century, when mitochondrial PEP transport and metabolism were re-examined, leading to the identification of pyruvate kinase (PK) activity within mitochondria of both plant [39] and mammalian cells, in particular PK in pig liver mitochondria (PLM) was investigated [40].

Notice that this work confirmed experimentally the existence of mPK already predicted from interrogation of the NCBI genome database (see [40]). Whether mitochondrial PK exists also in other mammalian mitochondria remains to be established. However, the evidence that PEP itself can produce citrate, and that 3-mercaptopicolinate, an inhibitor of the mitochondrial PEP-CK, can prevent only partially the citrate synthesis (see [40]) is in favor of the occurrence of mitochondrial PK in rat, rabbit and pigeon mitochondria.

These findings challenged the traditional view of PEP metabolism as an exclusively cytosolic process.

Despite these advances, the role of PEP transport and metabolism in mitochondria, including the existence and functional relevance of mitochondrial PK, has been largely overlooked in several influential reviews published during the second decade of this century. Notable examples include the work by McCommis and Finck [41] on mitochondrial pyruvate transport, the comprehensive review by Cerdan [42] summarizing nearly three decades of research on cerebral pyruvate recycling, and the analysis by Chinopoulos [43] of biochemical pathways connecting glucose and other metabolites to pyruvate and L- or D-lactate in the brain. Collectively, these omissions underscore the need for a critical re-evaluation of PEP metabolism that integrates both historical evidence and recent discoveries.

Notably, in skeletal muscle, triose phosphates can be generated through the reversal of PK activity, and L-lactate can contribute to glycerol and glycogen synthesis via PK reversal [44], further supporting the physiological relevance of non-canonical PEP–PK pathways.

As described in [3], PEP enters mitochondria in a carrier-mediated manner; inside PLM, PEP can give pyruvate via mPK likely with ATP synthesis from endogenous ADP. Since citrate and oxaloacetate are exported outside mitochondria as a result of PEP addition to PLM, we are forced to assume that they are newly synthesized as a result of the intramitochondrial metabolism of PEP and exported. This may occur as follows: inside the matrix pyruvate, newly synthesized from taken up PEP via PK, gives acetyl-CoA via the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, and oxaloacetate is formed via the acetyl-CoA activated pyruvate carboxylase and/or the mitochondrial PEP-CK; in turn oxaloacetate can be condensed with acetyl-CoA to produce citrate as well as being exported outside mitochondria, likely via a putative PEP/oxaloacetate antiporter. The newly synthesized citrate is transported outside mitochondria, perhaps in exchange with PEP, thus starting fatty acid synthesis, by providing acetyl-CoA via the ATP dependent citrate lyase, by regulating the cytosolic metabolism with inhibition of phosphofructokinase and activation of the acetyl-CoA carboxylase. The exported oxaloacetate is assumed to be reduced by the cytosolic NADH via malate dehydrogenase, to malate which in turn could produce NADPH via malic enzyme to be used in fatty acid synthesis.

The discovery of mitochondrial PK necessitates a revision of current models of mammalian PEP metabolism. The existence of mitochondrial PEP uptake, its conversion within mitochondria, and the export of derived metabolites imply an additional regulatory node connecting glycolysis, lipid biosynthesis, and gluconeogenesis. Interestingly, no mention of mitochondrial pyruvate kinase is made in [45], where the structure, function, and regulation of pyruvate kinases were comprehensively reviewed, underscoring the need for further biochemical and structural characterization. In light of these findings, the current view of PEP metabolism in mammals, at least in pigs, must be revised.

In conclusion, studies of PEP metabolism should carefully consider mitochondrial PEP uptake, its intramitochondrial conversion, and the export of newly synthesized metabolites. The presence of mitochondrial PK provides new insights into the integration of cytosolic and mitochondrial metabolism. Its characterization may reveal additional mechanisms of metabolic regulation, energy distribution, and biosynthetic coordination in both plant and animal cells.

5. Conclusions

Mitochondrial metabolite transport remains one of the most fascinating yet underexplored aspects of cellular bioenergetics. Despite extensive biochemical evidence demonstrating the existence of specific transport systems for fumarate, glutamine, and other key intermediates, much of the modern literature fails to acknowledge or build upon these earlier findings. For example, in a review reporting that “mitochondrial processes play an important role in tumor initiation and progression”, only three mitochondrial contributions to cancer are considered, namely, alterations in glucose metabolism, production of reactive oxygen species, and impairment of intrinsic apoptotic function, while mitochondrial metabolite transport is entirely neglected [46]. Similarly, in a paper stating that “seventy years after the formalization of the Krebs cycle as the central metabolic hub sustaining cellular respiration, key functions of several of its intermediates, especially succinate and fumarate, have recently been uncovered”, the issue of fumarate transport remains unaddressed [47]. The same omission is evident in studies describing “Krebs cycle metabolon formation” [48], as well as in more recent papers focused on “targeting mitochondrial metabolism for precision medicine in cancer” [49] and “targeting mitochondrial transporters and metabolic reprogramming for disease treatment” [50], where the role of mitochondrial transport in energy metabolism is largely ignored.

To the best of the author’s knowledge, among more than thirty biochemistry textbooks published after the discovery of fumarate and glutamine transport in mitochondria, only Albert Lehninger explicitly mentions that fumarate can enter mitochondria, without providing any indication of the underlying transport mechanism: “The fumarate generated in cytosolic arginine synthesis can therefore be converted to malate in the cytosol, and these intermediates can be further metabolized in the cytosol or transported into mitochondria for use in the citric acid cycle” [51].

The integration of transport processes with metabolic fluxes—linking anaplerotic and cataplerotic reactions—constitutes a dynamic equilibrium that is central to mitochondrial function. Revisiting and expanding classical experimental data using modern analytical tools will be essential for a renewed understanding of how mitochondrial transport orchestrates energy metabolism, redox balance, and biosynthetic capacity across different tissues.

Considering that the human body comprises more than 200 distinct cell types, each characterized by specific physiological functions, and that mitochondria themselves display a high degree of functional versatility, including the regulated transport of metabolites into and out of the organelle, it follows that a deeper understanding of mitochondrial physiology can only be achieved through experiments conducted on individual mitochondria under conditions that closely approximate the physiological state. Such an approach necessitates the adoption of experimental procedures that are simple, rapid, and capable of faithfully reproducing physiological conditions.

In this context, it is advisable to re-evaluate and prioritize these methodologies over more contemporary techniques, which, although valuable for elucidating isolated mechanistic details, often do so at the expense of an integrated and physiologically relevant perspective. A return to experimental strategies grounded in physiological realism may therefore provide a more comprehensive understanding of bioenergetics and cellular biochemistry.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Passarella, S.; Atlante, A.; Valenti, D.; de Bari, L. The role of mitochondrial transport in energy metabolism. Mitochondrion 2003, 2, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlante, A.; Passarella, S.; Pierro, P.; Di Martino, C.; Quagliariello, E. The mechanism of proline/glutamate antiport in rat kidney mitochondria. Energy dependence and glutamate-carrier involvement. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996, 241, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarella, S.; Schurr, A.; Portincasa, P. Mitochondrial Transport in Glycolysis and Gluconeogenesis: Achievements and Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passarella, S. Revisiting concepts of mitochondrial transport and energy metabolism in health and cancer. Acad. Biol. 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, T.; Hiraga, K.; Tuboi, S. Intracellular distribution of fumarase in various animals. J. Biochem. 1984, 96, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, J.B.; Haarhoff, K.N. The Penetration of the Mitochondrial Membrane by Anions and Cations; Slater, E.C., Kaniuga, Z., Wojtczak, L., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1966; pp. 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pallotta, M.L.; Fratianni, A.; Passarella, S. Metabolite transport in isolated yeast mitochondria: Fumarate/malate and succinate/malate antiports. FEBS Lett. 1999, 462, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, F.; Agrimi, G.; Blanco, E.; Castegna, A.; Di Noia, M.A.; Iacobazzi, V.; Lasorsa, F.M.; Marobbio, C.M.; Palmieri, L.; Scarcia, P.; et al. Identification of mitochondrial carriers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by transport assay of reconstituted recombinant proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1757, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, L.; Lasorsa, F.M.; De Palma, A.; Palmieri, F.; Runswicka, M.J.; Walker, J.E. Identification of the yeast ACRl gene product as a succinate-fumarate transporter essential for growth on ethanol or acetate. FEBS Lett. 1997, 417, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlante, A.; Gagliardi, S.; Passarella, S. Fumarate permeation in normal and acidotic rat kidney mitochondria: Fumarate/malate and fumarate/aspartate translocators. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 24, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinze, I.J. Facilitating understanding of the purine nucleotide cycle and the one-carbon pool: Part I: The purine nucleotide cycle. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2005, 33, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, W.L.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Fernie, A.R. Fumarate: Multiple functions of a simple metabolite. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Selak, M.A.; Gottlieb, E. Succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate hydratase: Linking mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4675–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajaj, E.; Sciacovelli, M.; Frezza, C.; Erez, A. The context-specific roles of urea cycle enzymes in tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3749–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshet, R.; Szlosarek, P.; Carracedo, A.; Erez, A. Rewiring urea cycle metabolism in cancer to support anabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, N.; Mahalanobish, S.; Sil, P.C. Reprogramming of urea cycle in cancer: Mechanism, regulation and prospective therapeutic scopes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 228, 116326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatton, D.; Frezza, C. Fumarate. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 36, 778–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarella, S.; Atlante, A. Teaching the role of mitochondrial transport in energy metabolism. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2007, 35, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlante, A.; Passarella, S.; Minervini, G.M.; Quagliariello, E. Glutamine transport in normal and acidotic rat kidney mitochondria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994, 15, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curthoys, N.P.; Watford, M. Regulation of glutaminase activity and glutamine metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1995, 15, 133–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumvoll, M.; Perriello, G.; Meyer, C.; Gerich, J. Role of glutamine in human carbohydrate metabolism in kidney and other tissues. Kidney Int. 1999, 55, 778–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, Z.E.; Dang, C.V. Glutamine Skipping the Q into Mitochondria. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, P.; Lima, M.M.; Procopio, J.; Pithon-Curi, T.C.; Doi, S.Q.; Bazotte, R.B.; Curi, R. Glutamine and glutamate as vital metabolites. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2003, 36, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matés, J.M.; Segura, J.A.; Campos-Sandoval, J.A.; Lobo, C.; Alonso, L.; Alonso, F.J.; Márquez, J. Glutamine homeostasis and mitochondrial dynamics. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 2051–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalise, M.; Pochini, L.; Galluccio, M.; Indiveri, C. Glutamine transport. From energy supply to sensing and beyond. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1857, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalise, M.; Pochini, L.; Galluccio, M.; Console, L.; Indiveri, C. Glutamine transport and Mitochondrial Metabolism in Cancer Cell Growth. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.C.; Park, S.J.; Nam, M.; Kang, J.; Kim, K.; Yeo, J.H.; Kim, J.K.; Heo, Y.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, M.Y.; et al. A Variant of SLC1A5 Is a Mitochondrial Glutamine Transporter for Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer Cells. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahya, U.; Lukiyanchuk, V.; Gorodetska, I.; Weigel, M.M.; Köseer, A.S.; Alkan, B.; Savic, D.; Linge, A.; Löck, S.; Peitzsch, M.; et al. Disruption of glutamine transport uncouples the NUPR1 stress-adaptation program and induces prostate cancer radiosensitivity. Cell Commun. Signal. 2025, 23, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Ko, B.; Hensley, C.T.; Jiang, L.; Wasti, A.T.; Kim, J.; Sudderth, J.; Calvaruso, M.A.; Lumata, L.; Mitsche, M.; et al. Glutamine oxidation maintains the TCA cycle and cell survival during impaired mitochondrial pyruvate transport. Mol. Cell 2014, 56, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vitto, H.; Pérez-Valencia, J.; Radosevich, J.A. Glutamine at focus: Versatile roles in cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 1541–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Kirk, K.; Shurubor, Y.I.; Zhao, D.; Arreguin, A.J.; Shahi, I.; Valsecchi, F.; Primiano, G.; Calder, E.L.; Carelli, V.; et al. Rewiring of Glutamine Metabolism Is a Bioenergetic Adaptation of Human Cells with Mitochondrial DNA Mutations. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1007–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlakonda, L.; Indracanti, M.; Kalangi, S.K.; Gayatri., B.M.; Naidu, N.G.; Reddy, A.B.M. The Role of Pi, Glutamine and the Essential Amino Acids in Modulating the Metabolism in Diabetes and Cancer. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2020, 19, 1731–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frattaruolo, L.; Brindisi, M.; Curcio, R.; Marra, F.; Dolce, V.; Cappello, A.R. Targeting the Mitochondrial Metabolic Network: A Promising Strategy in Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacifico, F.; Leonardi, A.; Crescenzi, E. Glutamine Metabolism in Cancer Stem Cells: A Complex Liaison in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, R.; Mulholland, M.T.; Sedensky, M.; Morgan, P.; Johnson, S.C. Glutamine metabolism in diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2023, 126, 103887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamble, J.L., Jr.; Mazur, J.A. Intramitochondrial metabolism of phosphoenolpyruvate. J. Biol. Chem. 1967, 242, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahota, Z.; Rauchova, H.; Mikova, M.; Kaul, P.; Bass, A. Phosphoenolpyruvate shuttle–transport of energy from mitochondria to cytosol. FEBS Lett. 1983, 157, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, T.J.; Wuensch, S.A.; Ray, P.D. Synthesis of citrate from phosphoenolpyruvate and acetylcarnitine by mitochondria from rabbit, pigeon and rat liver: Implications for lipogenesis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1996, 114, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bari, L.; Valenti, D.; Pizzuto, R.; Atlante, A.; Passarella, S. Phosphoenolpyruvate metabolism in Jerusalem artichoke mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1767, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzuto, R.; Paventi, G.; Atlante, A.; Passarella, S. Pyruvate kinase in pig liver mitochondria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 495, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCommis, K.S.; Finck, B.N. Mitochondrial pyruvate transport: A historical perspective and future research directions. Biochem. J. 2015, 466, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdan, S. Twenty-seven Years of Cerebral Pyruvate Recycling. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinopoulos, C. From glucose to lactate and transiting intermediates through mitochondria, bypassing pyruvate kinase: Considerations for cells exhibiting dimeric PKM2 or otherwise inhibited kinase activity. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 543564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, E.S.; Sherry, A.D.; Malloy, C.R. Lactate Contributes to Glyceroneogenesis and Glyconeogenesis in Skeletal Muscle by Reversal of Pyruvate Kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 30486–30497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schormann, N.; Hayden, K.L.; Lee, P.; Banerjee, S.; Chattopadhyay, D. An overview of structure, function, and regulation of pyruvate kinases. Protein Sci. 2019, 28, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogg, V.C.; Lanning, N.J.; Mackeigan, J.P. Mitochondria in cancer: At the crossroads of life and death. Chin. J. Cancer 2011, 30, 526–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénit, P.; Letouzé, E.; Rak, M.; Aubry, L.; Burnichon, N.; Favier, J.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.P.; Rustin, P. Unsuspected task for an old team: Succinate, fumarate and other Krebs cycle acids in metabolic remodeling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1837, 1330–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Pelster, L.N.; Minteer, S.D. Krebs cycle metabolon formation: Metabolite concentration gradient enhanced compartmentation of sequential enzymes. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainero-Alcolado, L.; Liaño-Pons, J.; Ruiz-Pérez, M.V.; Arsenian-Henriksson, M. Targeting mitochondrial metabolism for precision medicine in cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselme, M.; He, H.; Lai, C.; Luo, W.; Zhong, S. Targeting mitochondrial transporters and metabolic reprogramming for disease treatment. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson David, L.; Cox, M.M. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 4th ed.; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 668. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.