Abstract

We investigated the roles and regulation of contractile and sodium ion transporter proteins in the pathogenesis of diarrhea in the acute ulcerative colitis. Acute ulcerative colitis was induced in male Sprague-Dawley rats using dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in drinking water for seven days. The effects of nobiletin, a citrus flavonoid, were also examined. Increased myeloperoxidase activity, colon mass, and inflammatory cell infiltration were associated with damage to goblet cells and the epithelial cell lining indicating the development of acute ulcerative colitis. SERCA-2 calcium pump expression remained unchanged, whereas the phospholamban (PLN) regulatory peptide was reduced and its phosphorylated form (PLN-P) increased, suggesting a post-translational increase in SERCA-2 activity in the inflamed colon. Higher levels of IP3 were associated with a decrease in the Gαq protein levels without altering phospholipase C expression, suggesting that IP3 regulation is independent of Gαq protein signaling. In addition, the expression of sodium/hydrogen exchanger isoforms NHE-1, NHE-3 and carbonic anhydrase-1 and sodium pump activity were decreased in the inflamed colon. Nobiletin treatment of colitis selectively reversed the inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, including superoxide dismutase and catalase without restoring the expression of ion transporters. This study highlights alterations in the expression of ion transporters and their regulatory proteins in acute ulcerative colitis. These changes in the ion transporters are likely to reduce NaCl absorption and alter contractility, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of diarrhea in the present model of acute ulcerative colitis. Nobiletin selectively ameliorates acute colitis in this model.

1. Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are two major forms of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) that commonly affect individuals worldwide [1]. These conditions are associated with decreased colonic contractility, rapid transit, and increased propulsive activity in the gastrointestinal tract, contributing to diarrhea [2,3]. These changes cause diarrhea which is likely resulting from the defects in Ca2+ mobilization in smooth muscle cells and impaired sodium transport in gastrointestinal epithelial cells [2]. Studies have shown an impaired extracellular and intracellular Ca2+ mobilization due to defects in the L-type calcium channels in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases [4,5,6,7,8]. However, the role of IP3-sensitive Ca2+ channels, which release calcium from intracellular stores, remains incompletely understood in the acute ulcerative colitis. For the efficient functioning of IP3-sensitive calcium channels, refilling of the intracellular calcium stores (ER) by the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum-bound calcium ATPase, or SERCA-2 Ca-pump, is critical. The SERCA-2 activity is inhibited by phospholamban (PLN) inhibitory peptide and activated by PLN-P, the phosphorylated form [9]. Therefore, it is also essential to investigate the role and regulation of SERCA-2 by measuring the levels of Ca2+ signaling molecules, including IP3, PLN, PLN-P, protein Gq, and PLCy in the acute stage of ulcerative colitis.

Impaired epithelial Na+ transport in the inflamed colon is also likely to contribute to diarrhea [10]. Transport of Na+ is regulated by Na-H exchangers (NHE), Na channels, pump, and cotransporters [11,12,13]. While NHEs are responsible for an electroneutral absorption of NaCl and water, epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) regulate electrogenic Na+ absorption from the distal colon. Altered expression of epithelial Na+ transporters, including NHEs, ENaC, and sodium pump, has been reported in chronic inflammation in human IBDs [11,12,14,15,16]. NHE-3 isoform is the main regulator of electroneutral uptake of NaCl from the gastrointestinal tract, whereas NHE-1 primarily regulates intracellular pH [17,18,19,20,21,22]. The activity of NHE is regulated by Na+ and H+ ion gradients established, respectively, by the sodium pump and carbonic anhydrase (CA) [3]. Several studies have reported conflicting results on the suppression of sodium pump activity in chronic colitis [23,24,25,26]. The carbonic anhydrase isoforms CA-1 and CA-2 also regulate the NHE-1 activity by a direct interaction, which is disrupted in TNBS-induced colitis [27]. Proton (H+) and HCO3− produced by CA are removed, respectively, by NHE and anion exchangers SLC4A and SLC26A. Among the several SLC26A isoforms, SLC26A3 and SLC26A6 are primarily responsible for apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in the mammalian intestine [28]. Colon expresses a high level of SLC26A3 playing a key role in chloride (Cl−) absorption, whereas the electrogenic SLC26A6 exchanger is predominantly localized to the small intestine [29]. Notably, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the SLC26A3 gene have been reported to increase susceptibility to ulcerative colitis [30], possibly by altering the luminal pH, mucosal barrier, and dysbiosis [31]. The reports on the role of the anion exchanger in IBD are conflicting, with findings ranging from induction and suppression to no observable change. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the role of key ion transporters, including NHE-1, NHE-3, the sodium pump, carbonic anhydrase, and the anion exchanger SLC26A3, in the acute ulcerative colitis.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying diarrhea in the acute ulcerative colitis induced in male Sprague-Dawley rats using dextran sulfate sodium. The role of muscle contractility was also investigated by examining the expression of SERCA-2, phospholamban, and inositol trisphosphate (IP3) levels. Furthermore, the level of Gαq protein and phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) signaling molecules was also examined in the inflamed colonic tissue. To explore the role of sodium transport, we examined the expression of NHE-1, NHE-3, and their regulators, including the sodium pump, carbonic anhydrase, and the chloride-bicarbonate exchanger. Acute ulcerative colitis was induced by administering DSS in the drinking water for seven days, as described recently [32]. We observed ameliorative effects of nobiletin in colitis, which support our recent findings [32]. However, these findings showed a lack of reversal effect of nobiletin on the expression of the selected ion transporter proteins in the present model. We predict that changes in the transporters expression in ulcerative colitis are secondary to the inflammation and hence not reverted in the present model of acute UC.

Our findings demonstrate a post-translational activation of both SERCA-2 and IP3-sensitive calcium channels in acute ulcerative colitis. This dual activation is likely to disturb cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels, contraction, and propulsive action in the inflamed colon. Interestingly, an increase in IP3 concentrations despite a reduction in Gαq protein expression and no significant change in PLCγ levels suggests that the IP3 increase in this context is regulated independently of the canonical Gαq-PLCγ axis. Regarding Na+ absorption, a reduction in Na+ transporter and CA-1 expression, without any change in CA-2, suggests a reduced NHE activity in the inflamed colon. These changes lead to the accumulation of intracellular Na+ and H+, resulting in acidosis, cell swelling, and necrosis.

Nobiletin selectively reversed the inflammatory markers, sparing ion transporters in the present acute ulcerative colitis model. In conclusion, the epithelial cell Na+ and Ca2+ transport defects, together with thinning of the colonic muscularis, likely affect the colonic muscle contractility and diarrhea in the present model of acute ulcerative colitis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Induction of Colitis

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (6 weeks old) used in this study were maintained by the Animal Care Facility, College of Medicine, Kuwait University, following the animal care guidelines. Colitis was induced by allowing the animals free access to a freshly prepared 6% aqueous solution of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS, MP Biomedicals Inc, Solon, OH, USA) for the first 3 days, followed by 3% DSS solution for an additional 4 days, until day 7 [32]. This study was approved by the Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Committee via approval number 23/VDR/EC.

2.2. Nobiletin Treatment

Nobiletin (Catalog# CFN98726, ChemFaces, Wuhan, China) was suspended in the autoclaved phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and daily administered (60 mg/kg BW) orally. The drug was initiated 2 days before DSS administration and terminated 2 h before sacrificing the animals on day 7 post-induction of colitis. The dose of nobiletin did not have any adverse effects on the non-colitis control animals, and was effective in reducing inflammation in the same model of ulcerative colitis reported earlier [32,33,34,35].

2.3. Test Groups

This study was conducted using four experimental groups: C (non-colitis control), D (DSS-colitis), CN (non-colitis controls treated with nobiletin), and DN (DSS-colitis treated with nobiletin). On day 7, animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation, colons were taken out, cleaned with ice-cold PBS, and used in this study.

2.4. Percentage Body Weight Change

The animal body weights were recorded daily until day 7. Changes in body weight were expressed as a percentage weight gain relative to the body weight on day 0. On day 7, post-sacrifice colon weight and colon length were measured and used for different experiments as described recently.

2.5. Myeloperoxidase Activity

Colonic myeloperoxidase activity (MPO), a reliable marker of acute inflammation, was used to assess the induction of colitis by DSS [32]. Briefly, MPO activity was measured in the colonic tissue lysates in the presence of O-dianisidine (Sigma, Dorset, UK) as described [32].

2.6. Superoxide Dismutase Assay

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) was measured in the colon tissue homogenates using the Invitrogen SOD colorimetric activity kit (Catalog# EIASODC, ThermoFisher Scientific, Horsham, UK). Following the manufacturer’s protocol, undiluted samples and standards were added to the designated wells, followed by addition of the substrate and the chromogenic detection reagents. After 20 min of incubation at room temperature, absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 450 nm (BMG LabTech ClarioStar, Ortenberg, Germany). A standard curve was prepared to calculate enzyme activity in the samples.

2.7. Catalase Assay

Catalase activity was measured in the colonic tissue homogenates using a colorimetric assay kit (Catalog# EIACATC, ThermoFisher Scientific, Horsham, UK). Homogenate and standard samples were mixed with hydrogen peroxide in appropriate wells and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the substrate and horse radish peroxidase (HRP) were added into each well. After incubation for 15 min the absorbance was measured at 560 nm spectrophotometrically (BMG LabTech ClarioStar). To measure the catalase activity, a catalase standard curve was prepared using standards provided with the kit.

2.8. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

Cleaned colonic segments fixed in paraformaldehyde were used to prepare paraffin-embedded tissue blocks [32]. Thin tissue sections (5 μm thickness), collected onto coated-glass slides, were stained with hematoxylin and eosin dyes (Sigma, Dorset, UK) using routine methods [32]. Histological scores were measured and photographed using a camera (Olympus DP71, Tokyo, Japan) attached to a microscope (Olympus BX 51TF, Tokyo, Japan).

2.9. Mucin Staining

Integrity of the mucin layer was examined by alcian blue (1% alcian dye, pH 2.5) staining of the colonic tissue sections [32]. The sections were analyzed and photographed using a camera (Olympus DP71) attached to the microscope (Olympus BX 51TF).

2.10. Expression of Contractile Proteins

ECL Western blot analysis was employed to examine the expression of contractile proteins in the colonic tissue lysates.

2.10.1. ECL Western Blot Analysis

Colonic tissues were chopped with scissors and homogenized using an ice-cold 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid buffer solution (pH 7.4) containing EDTA (1 mM) and EGTA (1 mM) and PMSF (1 mM) and DTT (1 mM). Lysates were centrifuged at 600× g for 10 min, and the supernatants were collected after passing through cheesecloth. The supernatants were then centrifuged at 5000× g for 10 min, and the resulting supernatants were collected for protein expression studies. Crude microsomes were also prepared by centrifuging a portion of each supernatant at 188,000× g for 45 min (Sorvall, Dumfries, UK). All steps were conducted at 4 °C.

Total protein concentrations in the lysates and crude microsomes were estimated using a protein-dye binding assay kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). The protein samples (2 mg/mL protein) were electrophoresed on a polyacrylamide gel along with a pre-stained protein size marker (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 60 volts for 1–2 h at ambient temperature. Subsequently, the separated proteins were electroblotted from the gels onto PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare, Amersham-Hybond TM-P, Uppsala, Switzerland). After washing with 1× PBS, the membranes were blocked with a 5% skimmed milk solution for 30 min and then incubated with appropriate primary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). After washing, the membranes were incubated with the secondary antibody-peroxidase-conjugates (AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG, Jackson, West Grove, PA, USA) for 2 h. All steps were performed at ambient temperature with gentle shaking. Protein bands were developed using ECL reagents (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA), detected and quantified using Image Lab 6.0.1 software on a BioRad Chemi Doc (Bio-Rad chemi-DocTM MP Imaging System, Hercules, CA, USA).

To reprobe with different primary antibodies, the bound antibodies were removed by treating the membranes with 62.5 mM Tris-base buffer (pH 6.8) with 2% SDS, 100 mM ß-mercaptoethanol for 20 min at 50 °C with constant shaking.

2.10.2. Measurement of Inositol Trisphosphate

Inositol trisphosphate (IP3) was measured in colonic homogenates using a rat IP3 ELISA Kit (Catalog# MBS754505, MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA). The diluted homogenate samples were incubated with IP3-HRP conjugate in a pre-coated plate for 1 h, following the manufacturer’s instructions. At the end of incubation, the wells were washed with a buffer and then incubated with an HRP enzyme substrate. The reaction was terminated, and the color intensity was measured at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer (BMG LabTech ClarioStar, Germany). A standard curve was also prepared using 0–50 ng/mL concentrations of the IP3 supplied with the kit to calculate IP3 concentration (ng/mL).

2.11. Sodium Pump Activity

Sodium pump activity was represented by the ouabain-sensitive K-stimulated p-nitrophenylphosphatase (PNPase) activity of the sodium pump. Briefly, the colonic homogenates were diluted to 1 µg/µL using imidazole buffer (pH 7.4). The pump activity was measured in the absence (A) and presence (B) of ouabain (Sigma) at 37 °C for 1 h in a water bath. The optical density of the samples was measured at 410 nm using a spectrophotometer. The activity was calculated using the equation: PNPase activity = (ODA − ODB) × 63 µmol/mg/min.

2.12. mRNA Expression

Total RNA was extracted from colonic segments using a TRIzol kit (Invitrogen, Oxford, UK). Briefly, tissues were homogenized in TRIzol solution, extracted with phenol and chloroform, and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min to collect the aqueous layer. Total RNA was precipitated from the aqueous layer using isopropanol and recovered by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. RNA pellets were washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried, and suspended in RNase-free deionized water. The quality and concentration of the total RNA were examined by measuring the optical density at 260 nm and 280 nm. DSS inhibits RT-PCR reaction; therefore, the total RNA was further purified by two rounds of 8M LiCl precipitation [32,36].

The primers selective for NHE-1 and NHE-3 were designed using the published sequences XM_032896551.1 and NM_012654.2, respectively. The mRNA levels were quantified using the purified RNA samples by the realtime RT-PCR method with Sybr green dye. The mRNA expression levels were represented as the ratios of NHE mRNA to β-actin mRNA.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SD, and the differences between the mean values of two or more groups were tested using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The significance was further evaluated with a post hoc Tukey test using GraphPad Prism version 10. A value of significance at p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant compared to respective controls.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Colitis

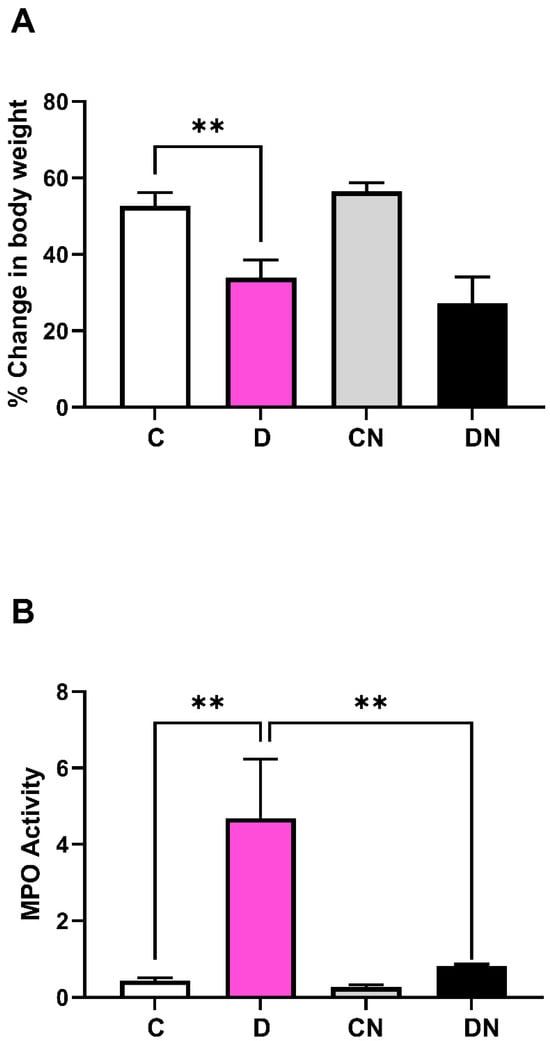

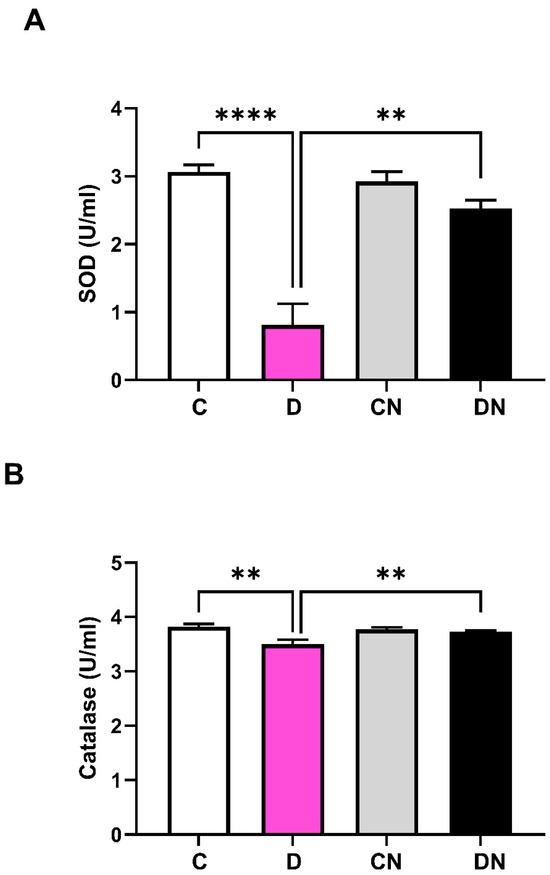

The growth of colitis animals on day 7 was significantly inhibited compared to the non-colitis controls, regardless of nobiletin treatment (Figure 1A). MPO activity was markedly increased in the inflamed colon, which was suppressed significantly by the nobiletin treatment (Figure 1B). Colitis was also assessed by measuring the superoxide dismutase (SOD) (Figure 2A) and catalase activity (Figure 2B). DSS caused a significant reduction in both SOD and catalase enzyme activities in the inflamed-colon, which was significantly reversed by the nobiletin treatment (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 1.

Shown are (A): percentage animal body weight changes on day 7 post-induction of colitis, relative to their weights at day 0, and (B): colonic myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (units/mg/min) in tissue samples from the four test conditions: non-colitis control (C), DSS-induced colitis (D), non-colitis treated with nobiletin (CN) and DSS-colitis treated with nobiletin (DN). Data are means ± SD (n = 10). ** Significance at p < 0.05 between the indicated groups.

Figure 2.

Shown are (A): superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity (units/mL), and (B): catalase activity (units/mL) in colonic segments taken from non-colitis control (C), DSS-induced colitis (D), non-colitis treated with nobiletin (CN), and DSS-colitis treated with nobiletin (DN). Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 10). ** and **** indicate significance at p < 0.05 between the shown groups.

3.2. Histological Changes

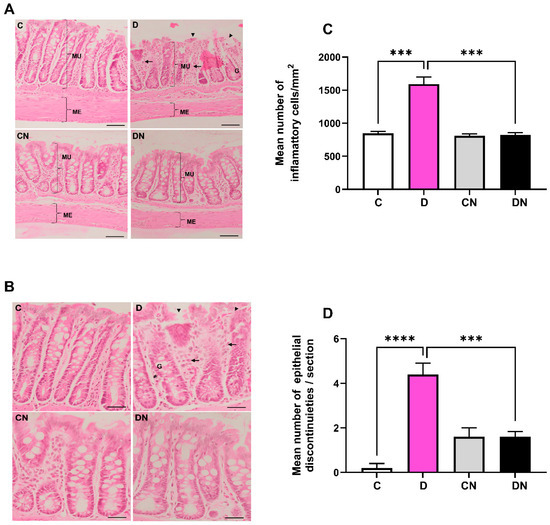

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained colonic sections exhibited increased infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lamina propria and submucosal layers. The epithelium was also disrupted. There was an increased infiltration of inflammatory cells (Figure 3A–C) and epithelial disruptions in the DSS-induced colitis group (Figure 3A,B,D). Furthermore, the quantitative data showed a significant increase in the mean number of inflammatory cells/mm2 and epithelial disruption in the inflamed colon, which were reversed by nobiletin treatment (Figure 3A–C).

Figure 3.

(A): A representative photomicrograph showing histology of colonic sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Inflammatory cells in the lamina propria and submucosal layers (arrows), epithelial disruption (arrow heads), goblet cells, and muscularis externa thickness are shown. (B): number of inflammatory cells/mm2 area of colon, and (C): bar diagram showing inflammatory cells per mm2, and (D): epithelial discontinuities/section in colon from the indicated test conditions. Data are mean ± SD (n = 5). *** and **** show significance at p < 0.05 between indicated groups. Scale bar = 50 µm.

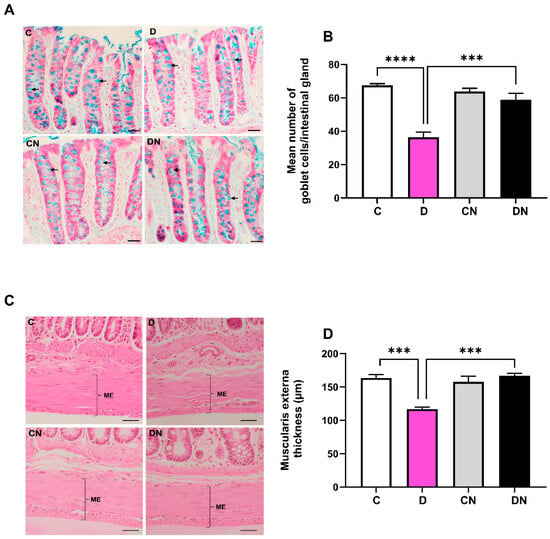

DSS significantly reduced the number of goblet cells, which were normalized by nobiletin treatment of the colitis animals (Figure 4A,B). Morphometry of the muscularis externa showed a significant thinning of the muscle layer in the inflamed colon, which was normalized by nobiletin treatment of the colitis animals (Figure 4C,D).

Figure 4.

(A): A representative photomicrograph of colonic mucosa showing goblet cells (arrows). (B): bar diagram showing mean number of goblet cells/intestinal gland, (C): a representative photomicrograph showing colon muscularis externa (ME), and (D): bar diagram showing muscularis externa thickness (µm) in the colon from the indicated test conditions. The data are the mean ± SD (n = 5). ***, **** show significance at p < 0.05 between indicated groups. Scale bar = 50 µm.

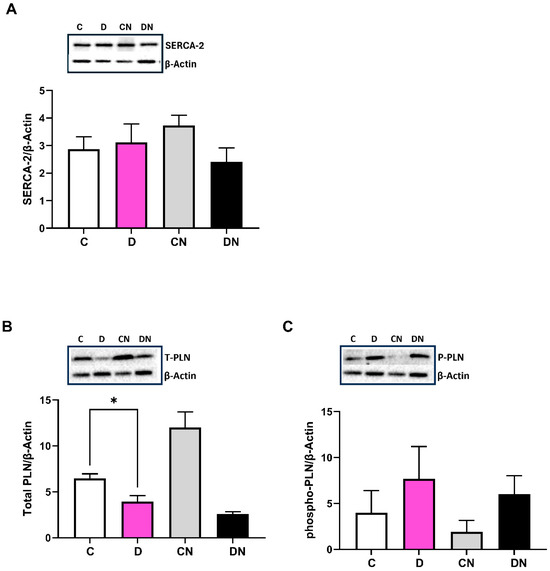

3.3. Expression of SERCA-2 and Phospholamban

The SERCA-2 Ca pump is expressed in the smooth muscle of the gastrointestinal tract [34]. The SERCA-2 selective primary antibodies reacted with an expected size of protein (Figure 5A). The SERCA-2 protein levels remained unchanged in all four test groups (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the expression of phospholamban, PLN inhibitory peptide was decreased significantly in the inflamed colon as compared to the non-colitis control regardless of nobiletin treatment (Figure 5B). However, phosphorylated PLN-P expression was increased in the DSS-inflamed colon compared to the controls irrespective of nobiletin treatment (Figure 5C). The level of β-actin a housekeeping gene remained unchanged in all test conditions.

Figure 5.

Shown are the expression of the indicated proteins, (A): calcium pump (SERCA-2) using SERCA-2 selective primary antibody (ABCAM, AB183531), (B): total phospholamban (PLN), and (C): phosphorylated phospholamban (P-PLN) using primary antibodies (ABCAM, AB234903 and AB15000) examined by ECL Western blot analysis relative to β-actin using primary antibodies (Sigma, A5316) in the colonic tissues from the indicated test conditions. In each case, the inset is a representative figure of the corresponding data from the four indicated conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 10). * Significance at p < 0.05 between the indicated groups.

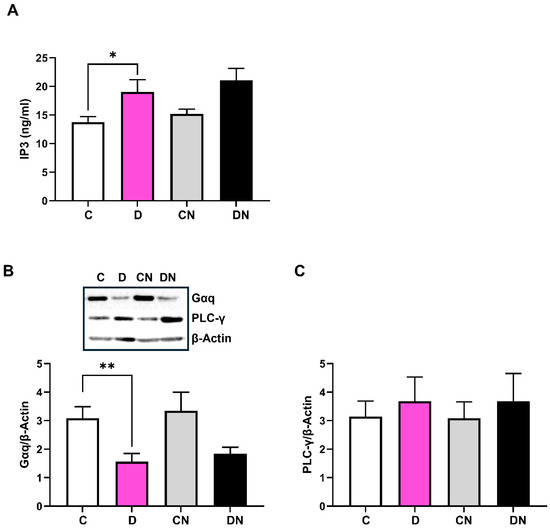

3.4. IP3-Sensitive Ca2+ Signaling

DSS increased the IP3 concentration in the inflamed colon, which was not reversed by nobiletin treatment of colitis (Figure 6A). Regarding the mechanism underlying the colitis-induced increase in the IP3 levels, we observed a decrease in the Gαq protein expression irrespective of nobiletin treatment (Figure 6B). In addition, DSS did not change the levels of PLC-γ in the test conditions (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Shown are the levels of (A): IP3 (ng/mL) determined by ELISA assay, (B): G-protein αq (Gαq) using primary antibodies (SantaCruz Sc136181), and (C): phospholipase C-gamma (PLC-y) with primary antibodies (ABCAM, AB131455) measured by ECL Western blot analysis relative to β-actin using the actin-selective primary antibodies (Sigma, A5316) in the colonic tissues from the indicated test conditions. Inset is a representative figure of the indicated protein from the four test conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 8). * and ** show significance at p < 0.05 between the indicated groups.

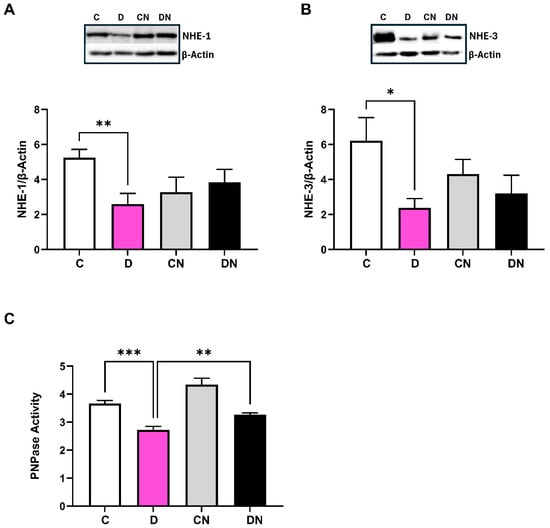

3.5. Expression of NHE Isoforms

The expression of NHE-1 and NHE-3 isoforms relative to β-actin was decreased in the inflamed colon, which was not reversed by nobiletin treatment (Figure 7A,B). To explore the underlying mechanism of NHE regulation, we examined the activity of sodium pump, which was significantly reduced in the inflamed colon (Figure 7C). Treatment of nobiletin restored sodium pump activity significantly (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Bar diagram showing the levels of expression of (A): NHE-1, (B): NHE-3 relative to β-actin using selective primary antibodies, and (C): sodium pump (PNPase) activity (units per mg protein) in the colonic tissues from the indicated test conditions. Inset shows a representative figure in the indicated four conditions. Data are mean ± SD (n = 6). *, **, *** show significance at p < 0.05 between the indicated groups.

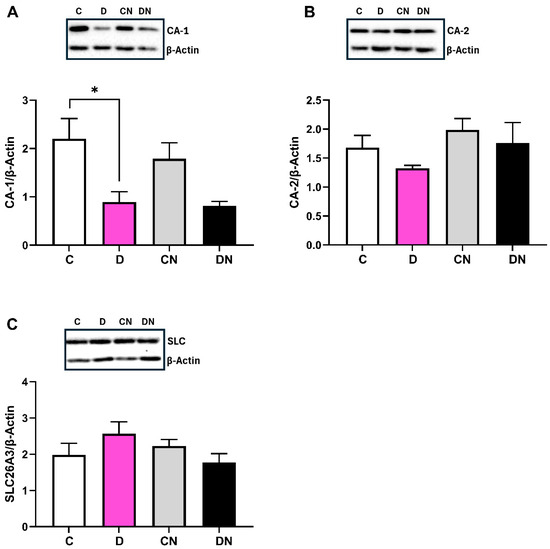

Furthermore, DSS reduced the level of carbonic anhydrase CA-1 isoform expression significantly in the inflamed colon, irrespective of nobiletin treatment (Figure 8A). However, the CA-2 expression remained unchanged in the inflamed colon (Figure 8B). Additionally, the level of SLC26A3 anion exchanger remained unchanged in the test conditions (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Bar diagram showing the level of expression of (A): carbonic anhydrase-1 (CA-1), (B): carbonic anhydrase-2 (CA-2), and (C): anion exchanger (SLC26A3) proteins relative to β-actin using selective primary antibodies, respectively, (Santacruz, Sc393497, Sc133111, Sc376187) with ECL Western blot analysis in the colonic tissues from the indicated test conditions. Insets show a representative figure in the indicated four conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 9). * Shows significance at p < 0.05 between the indicated groups.

The level of β-actin remained uniform in the test conditions and was used to calculate the ratios NHE:β-actin mRNA expression. The level of NHE-1 mRNA expression remained invariant in the test conditions, whereas NHE-3 mRNA was significantly reduced in the inflamed colon without any reversal by nobiletin.

4. Discussion

A delicate regulation of cations and anions is critical to maintain electrolyte homeostasis and intestinal contractility. An interplay between cation transport defects in the colonic epithelial and smooth muscle, therefore, underpins the complex pathophysiology of diarrhea. These mechanisms have been studied in human and animal models of chronic inflammatory IBD conditions, and inconsistencies have been reported in the results. We investigated the role and molecular mechanisms underlying the Na+ and Ca2+ transport in DSS-induced acute ulcerative colitis in rats. Specifically, we examined the roles of the NHE-1 and NHE-3 isoforms, carbonic anhydrase (CA), and sodium pump as markers of epithelial cell transport, and SERCA-2 Ca-pump and IP3-sensitive Ca channels as markers of the smooth muscle ion transport. The regulatory role of phospholamban in SERCA-2 activity and the Gαq protein-PLC signaling mechanism for IP3 regulation was also explored. It is to emphasize that we were interested in investigating changes in the acute stage of ulcerative colitis using the present animal model, which was developed recently [32]. Thus, by selecting these transporters and their regulatory molecules, we investigated the role and regulation of epithelial cell and smooth muscle cell transport comprehensively in the pathogenesis of acute experimental colitis. In addition, the effects of nobiletin, an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant natural flavonoid, were investigated on the selected transporters.

The NHE activity is crucial for a net uptake of NaCl in the gastrointestinal tract. While the NHE-1 isoform regulates intracellular pH, the NHE-3 isoform mediates a net uptake of NaCl in the gastrointestinal tract. We report a post-translational decrease in NHE-1 and NHE-3 activities in the present acute ulcerative colitis. These findings in acute colitis are consistent with earlier observations reported in the TNBS-induced chronic inflammation in the colon [8]. Functionally, this reduction is likely to decrease intracellular pH and increase intracellular Na+ load, fluid loss, cell necrosis, and tissue damage (present study). Since NHE-1 mRNA expression remained unchanged, while NHE-3 was decreased, we interpret that the expression of NHE isoforms is regulated post-translationally. To further investigate the post-translational regulation of NHE, we examined the levels of CA-1 and CA-2 isoforms, SLC26A3 anion exchanger, and sodium pump activity. Carbonic anhydrase produces HCO3− and H+ by reversible hydration of CO2 and regulates the NHE activity. The HCO3− anion fuels the SLC26A3 anion exchanger, allowing it to exchange Cl−. In our case, reduced expression of the CA-1 isoform and sodium pump activity without any change in CA-2 expression suggests a decrease in NHE activity in the inflamed colon.

For a net uptake of NaCl, HCO3− is exchanged with Cl− in an electroneutral manner by the SLC26A3 anion exchanger. As these transporters work in an integrated fashion, no change in the expression of SLC26A3 is likely to augment the electrolyte and water imbalance in the gastrointestinal tract. We examined these molecular changes using ECL Western blot analysis with β-actin as an internal control. Therefore, these changes are consequences of inflammation, culminating in diarrhea, a hallmark symptom of IBD. In conclusion, these findings suggest that the transport defects in the acute stage of ulcerative colitis are similar to those seen in the chronic model of colitis.

Next, we investigated the role of Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms, including SERCA-2 and IP3-sensitive Ca channels, and their regulation by phospholamban, IP3, Gαq, and PLC proteins. SERCA-2 calcium pump sequesters the cytoplasmic Ca2+ into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, promoting muscle relaxation [37]. In IBD, inflammation-induced oxidative stress and reported ER dysfunction can disrupt SERCA-2 function, compromising Ca2+ homeostasis. Notably, there was no change in the SERCA-2 protein expression. However, the phospholamban PLN, an inhibitory peptide, was reduced, and the phosphorylated PLN-P, which relieves SERCA-2 inhibition, was increased, suggesting a post-translational activation of SERCA-2 in the present acute ulcerative colitis. These findings do not support earlier findings reported in the chronic model of Crohn’s disease induced by TNBS in rats but indicate a defect in the Ca-refilling mechanism of internal Ca stores [8]. Increased SERCA-2 activity reduces cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration, disrupts calcium signaling, epithelial barrier function, and smooth muscle contractility, thereby exacerbating diarrhea.

Furthermore, increased IP3 concentration suggests increased porosity and disturbed Ca2+ homeostasis of the intracellular Ca2+ stores. Given the reduced Gαq protein expression, together with no change in PLC levels, the mechanism of IP3 increase appears to be independent of the Gαq and PLC signaling pathway. While IP3-mediated Ca2+ release is essential for smooth muscle contraction, excessive release or an inability of SERCA-2 to sequester Ca2+ may lead to abnormal contractility, colonic motility, and the development of diarrhea.

In the present study, we comprehensively examined the role and regulation of these ion transporters in the production of diarrhea in the present acute ulcerative colitis. This study reports the role of ion transport in epithelial cells and contractile proteins, particularly Ca-sensing proteins in the smooth muscle cells, in the pathogenesis of diarrhea.

Our model exhibited acute colonic inflammation, as demonstrated by increased MPO activity, oxidative stress markers, and inflammatory cell infiltration. Epithelial cell damage was evidenced by reduced mucin secretion and structural disruption in the colonic crypts. These findings consistently support our recent report [32]. Additionally, the muscularis externa was significantly thin in the inflamed colon, potentially impairing colonic contractile capacity, consistent with earlier reports in mouse models of chronic ulcerative colitis [38]. These findings provide a comprehensive presentation of the molecular and structural changes underlying diarrhea in acute ulcerative colitis.

Nobiletin treatment reversed the inflammation-induced molecular changes, including suppression of CA-1, sodium pump activity, and partly SERCA-2 regulatory mechanisms. However, NHE-1 and NHE-3 expression remained unchanged, indicating a selective action of nobiletin in acute colitis. These findings highlight the anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties of nobiletin, as evidenced by reduced MPO activity, restored superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase activity, and improved epithelial integrity. We and others have reported selective anti-inflammatory effects of different chemicals including biologics, peptides, and flavonoids on the immune pathways and barrier-related proteins, reducing inflammation and improving epithelial integrity in ulcerative colitis. However, nutrient and ion transporters like NHE-1, NHE-3, Na+/K+ pump remain unaffected by such anti-inflammatory treatment [32,39]. We predict that changes in the transporters expression in ulcerative colitis are secondary to the inflammation and hence not reverted in the present model of acute UC.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of ion transport and smooth muscle contractility dysfunction in the acute DSS-induced colitis model, highlighting their contribution to the development of diarrhea. Unlike previous studies that focused on individual transporters in chronic inflammation, we examined the molecular interplay of Na+ and Ca2+ transport mechanisms, elucidating their roles in the pathophysiology of diarrhea. The selective reversal of inflammation-induced changes by nobiletin underscores its therapeutic potential in acute colitis (Graphical abstract). Further research is warranted to explore the mechanisms underlying IP3 elevation and its implications in Ca2+ homeostasis.

Limitations

This experiment was conducted in an acute, chemically induced colitis model that may not fully replicate human colitis. Also, only one nobiletin dose (60 mg/kg) was evaluated, based on prior literature. Finally, our study focused on short-term therapeutic outcomes of nobiletin. Therefore, longer follow-up will be essential to determine if the nobiletin effect persists beyond the acute phase. This study was conducted using an animal study which does not truly replicate the chronic and relapsing human UC, making long-term therapeutic implications uncertain. In addition, differences in drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics are likely between animals and humans, which may affect dosing and systemic responses. The absence of comorbid conditions commonly seen in human patients further reduces clinical relevance.

Author Contributions

A.A.-F. was responsible for conducting experiments and data collection; M.R. assisted in histochemistry experiments and data interpretation; A.A.-J. prepared graphics; I.K. conceived the idea, supervised the overall project, interpretation, and writing, in collaboration with all co-authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Kuwait University Research Sector (grant # YM 10/20) and by the College of Graduate Studies, Kuwait University, Kuwait.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Committee (Approval code: 23/VDR/EC, Approval Date: 17 December 2020).

Data Availability Statement

Data sets were used to calculate the mean and SD, and were used to make the Figures presented in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The Research Sector, Kuwait University, for financial support through a grant, the Research Core Facility for their instrumentation facility, and Amna Al-Shamali for her technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Siddique, I.; Alazmi, W.; Al-Ali, J.; Longenecker, J.C.; Al-Fadli, A.; Hasan, F.; Memon, A. Demography and clinical course of ulcerative colitis in Arabs—A study based on the Montreal classification. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 49, 1432–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassotti, G.; Antonelli, E.; Villanacci, V.; Baldoni, M.; Dore, M.P. Colonic motility in ulcerative colitis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2014, 2, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greig, E.; Sanale, G.I. Diarrhea in ulcerative colitis. The role of altered colonic sodium transport. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 915, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarali, H.I.; Pothoulakis, C.; Castagliuolo, I. Altered Ion Channel Activity in Murine Colonic Smooth Muscle Myocytes in an Experimental Colitis Model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 275, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohama, T.; Hori, M.; Ozaki, H. Mechanism of abnormal intestinal motility in inflammatory bowel disease: How smooth muscle contraction is reduced? J. Smooth Muscle Res. 2007, 43, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Rusch, N.J.; Striessnig, J.; Sarna, S.K. Down-regulation of L-type calcium channels in inflamed circular smooth muscle cells of the canine colon. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I. Molecular basis of altered contractility in experimental colitis: Expression of L-type calcium channel. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1999, 44, 1525–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jarallah, A.; Oriowo, M.A.; Khan, I. Mechanism of reduced colonic contractility in experimental colitis: Role of sarcoplasmic reticulum pump isoform-2. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2007, 298, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesi, M.; Vorherr, T.; Falchetto, R.; Waelchli, C.; Carafoli, E. Phospholamban is related to the autoinhibitory domain of the plasma membrane Ca(2+)-pumping ATPase. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 7978–7983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.R.; Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Xu, M.; Fan, H.-W.; Zhang, Q.; Tan, G.H.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.-Q. Involvement of nitrergic neurons in colonic motility in a rat model of ulcerative colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 3854–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyamvada, S.; Gomes, R.; Gill, R.K.; Saksena, S.; Alrefai, W.A.; Dudeja, P.K. Mechanisms underlying dysregulation of electrolyte absorption in inflammatory bowel disease-associated diarrhea. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2926–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, H.J. Mechanisms of diarrhea in inflammatory bowel diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1165, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghishan, F.K.; Kiela, P.R. Epithelial transport in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barkas, F.; Liberopoulos, E.; Kei, A.; Elisaf, M. Electrolyte and acid-base disorders in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2013, 26, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Magalhaes, D.; Cabral, J.M.; Soares-da-Silva, P.; Magro, F. Role of epithelial ion transports in inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2016, 310, G460–G476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Augustin, O.; Romero-Calvo, I.; Suarez, M.D.; Zarzuelo, A.; de Medina, F.S. Molecular bases of impaired water and ion movements in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 2009, 15, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, J.; Grinstein, S. Na+/H+ exchangers of mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 22373–22376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliegel, L. Regulation of the Na(+)/H(+) exchanger in the healthy and diseased myocardium. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2009, 13, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Al-Awadi, F.M.; Abul, H. Colitis-induced changes in the expression of the Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE-1. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998, 285, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleiman, A.A.; Thameem, F.; Khan, I. Mechanism of downregulation of Na-H exchanger-2 in experimental colitis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xu, H.; Zhang, B.; Johansson, M.E.; Li, J.; Hansson, G.C.; Ghishan, F.K. NHE8 plays an important role in mucosal protection via its effect on bacterial adhesion. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2013, 305, C121–C128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shamali, A.; Khan, I. Expression of Na-H exchanger-8 isoform is suppressed in experimental colitis in adult rat: Lack of reversibility by dexamethasone. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgayer, H.; Kruis, W.; Paumgartner, G.; Wiebecke, B.; Brown, L.; Erdmann, E. Inverse relationship between colonic (Na+ + K+)-ATPase activity and degree of mucosal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1988, 33, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Collins, S.M. Altered expression of sodium pump isoforms in the inflamed intestine of Trichinella spiralis-infected rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1993, 264 Pt 1, G1160–G1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.; Alex, P.; Dassopoulos, T.; Zachos, N.C.; Iacobuzio-Donahue, C.; Donowitz, M.; Brant, S.R.; Cuffari, C.; Harris, M.L.; Datta, L.W.; et al. Downregulation of sodium transporters and NHERF proteins in IBD patients and mouse colitis models: Potential contributors to IBD-associated diarrhea. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sly, W.S.; Hu, P.Y. Human carbonic anhydrases and carbonic anhydrase deficiencies. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 64, 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Khan, K. Uncoupling of carbonic anhydrase from Na-H exchanger-1 in experimental colitis: A possible mechanistic link with Na-H exchanger. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Romero, M.F. Regulation of electroneutral NaCl absorption by the small intestine. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2011, 73, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alper, S.L.; Sharma, A.K. The SLC26 gene family of anion transporters and channels. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 494–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, K.; Matsushita, T.; Umeno, J.; Hosono, N.; Takahashi, A.; Kawaguchi, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Matsui, T.; Kakuta, Y.; Kinouchi, Y.; et al. A genome-wide association study identifies three new susceptibility loci for ulcerative colitis in the Japanese population. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1325–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Yu, Q.; Li, J.; Johansson, M.E.; Singh, A.K.; Xia, W.; Riederer, B.; Engelhardt, R.; Montrose, M.; Soleimani, M.; et al. Slc26a3 deficiency is associated with loss of colonic HCO3 (-) secretion, absence of a firm mucus layer, and barrier impairment in mice. Acta Physiol. 2014, 211, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Failakawi, A.; Al-Jarallah, A.; Rao, M.; Khan, I. The role of claudins in the pathogenesis of dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis: The Effects of nobiletin. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenlocher, Y.; Gommeringer, S.; Held, A.; Feilhauer, K.; Köninger, J.; Bischoff, S.C.; Lorentz, A. Nobiletin acts anti-inflammatory on murine IL-10-/- colitis and human intestinal fibroblasts. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Yu, H.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Ruan, J.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T. Citrus aurantium L. and its flavonoids regulate TNBS-induced inflammatory bowel disease through anti-inflammation and suppressing isolated jejunum contraction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.; Afridi, O.K.; Ullah, S.; Khan, H.; Bai, Q. Mitigation of sciatica injury-induced neuropathic pain through active metabolites derived from medicinal plants. Pharmacol Res. 2024, 200, 107076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viennois, E.; Chen, F.; Laroui, H.; Baker, M.T.; Merlin, D. Dextran sodium sulfate inhibits the activities of both polymerase and reverse transcriptase: Lithium chloride purification, a rapid and efficient technique to purify RNA. BMC Res. Notes 2013, 6, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Spencer, G.G.; Samson, S.E.; Crine, P.; Boileau, G.; Grover, A.K. Abundance of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump isoforms in stomach and cardiac muscles. Biochem. J. 1990, 268, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Lin, S.; Yang, Y.; Gong, X.; Tong, J.; Li, K.; Li, Y. Histological and ultrastructural changes of the colon in dextran sodium sulfate-induced mouse colitis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 1987–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandle, G.I.; Rajendran, V.M. Ion transport and epithelial barrier dysfunction in experimental models of ulcerative colitis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2025, 328, G811–G830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).