Abstract

Forces exerted by cells due to their internal contractility play fundamental roles in a host of processes, including adhesion, migration, survival and differentiation. Traction force microscopy (TFM) enables the determination of forces exerted by cells or cell collectives on their environment, which is typically taken to be an extra-cellular matrix (ECM)-coated substrate. Sample preparation for TFM involves the plating of cells onto an environment embedded with fiducial markers. The imaging of these fiducial markers in the presence and absence of the cells then enables calculation of the displacement of localized regions of the environment, and, consequently, the spatial distribution of forces exerted by the cells on their environment. Here, we consider the most widely used implementation of TFM (two-dimensional or 2D TFM) which enables the determination of in-plane forces exerted by cells plated on top of an elastic soft substrate. We present streamlined methods for preparing TFM substrates, with special consideration towards experimental steps involved in implementing it using an epifluorescence microscope. We highlight considerations involved in substrate choice between polyacrylamide (PAA) gels and soft silicones, fiducial marker (microbead) choice and distribution as well as microbead and ECM coupling to the substrate. We also point out caveats related to sub-optimal choices in the methodology which can affect the resultant traction force distribution, as well as further derived quantities such as inter-cellular forces in cell pairs computed using the traction force imbalance method (TFIM).

1. Introduction

Cells in all solid tissues not only adhere to their surroundings but also use energy to exert contractile forces on their surroundings [1,2]. These forces are transmitted through cell surface adhesions to the ECM and neighboring cells and influence the mechanical state of the tissue itself. Through mechanotransduction [3], these forces also influence the biochemical state of and gene expression in the cells. Thus, determination of the forces exerted by cells has gained increasing importance in understanding various aspects of cell physiology, including cell migration [4,5,6,7] and multi-cellular organization [8]. There are many approaches to determining cell-generated forces that vary in length-scale, as well as the equipment and reagents required to carry out the measurements [9,10,11,12,13]. Plating cells on a bed of microfabricated micro-pillars can yield cell-generated forces [14], but this approach involves considerable effort in substrate fabrication as well as a specific non-continuous adhesive microenvironment for the cells which may be less representative of the physiological context. In TFM, on the other hand, cells are plated on a continuous substrate embedded with fiducial markers, and cell-exerted forces are determined from the displacement field of the substrate [15,16]. TFM complements other techniques that determine molecular-level forces such as those that utilize molecular tension sensors [11,17,18,19]. While three-dimensional (3D) TFM deals with cells in 3D environments [20,21], and 2.5D TFM [22,23] deals with cells on 2D substrates but where fiducial marker displacements and cell-exerted forces are determined in 3D, we focus here on the more widely used 2D TFM [24,25,26], referred to henceforth here simply as TFM.

For a typical TFM experiment [27,28], the precursor to the soft substrate is first prepared as a liquid, coated/applied onto a glass coverslip, and then polymerized/cured to obtain a solid-like soft substrate affixed to the coverslip. Fiducial markers that eventually help visualize the soft substrate displacement field are either mixed into the soft substrate material before polymerization or coupled to the substrate surface after curing. An ECM protein such as fibronectin or collagen is also coupled to the substrate surface in order to enable specific adhesion between cells and the substrate. Imaging the fiducial markers with the cell present as well as with it absent is typically essential. Here, whether the fiducial markers—which are typically fluorescent microbeads—are imaged with a widefield, i.e., epifluorescence microscope, or with a confocal microscope affects the resolution of the image. While many labs use confocal microscopy [29,30] or other higher-resolution imaging setups [31,32] to obtain fiducial marker images for TFM, the more widely used epifluorescence microscope can just as well be employed, but requires more careful consideration with respect to the fiducial marker used, as well as how it is coupled to the substrate.

Using the images of fiducial markers with and without the cell, the displacement field of the substrate surface is first computed, followed by computational reconstruction of the traction field. There are various excellent articles addressing the computational aspects of TFM [33,34,35,36,37]. Here, our focus will be on considerations for the experimental aspects of TFM, including choice of substrate and fiducial markers as well as pitfalls one needs to be aware of in preparing substrates and imaging them, especially with an epifluorescence microscope. These choices ultimately affect the quality of the reconstructed traction force field of single cells or cell clusters and derived quantities like the inter-cellular force [8,38,39] in cell pairs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of PAA Gel

Square 22 mm glass coverslips were first cleaned by sonicating in a dilute solution of detergent (VersaClean, Fisherbrand, Waltham, MA, USA) and then rinsing with aqueous solutions of progressively higher concentrations of ethanol. These coverslips were stored in ethanol at room temperature and used for the subsequent steps. A collagen I-coated coverslip was first obtained by incubating coverslips with 0.033 mg/mL rat tail collagen I (Corning, Bedford, MA, USA) in sodium bicarbonate buffer, pH 8.5, for 30 min, followed by washing with Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS). Activated glass coverslips were prepared by incubating each clean coverslip with 50 µL of a mixture of 5.5% (v/v) glacial acetic acid and 0.4% (v/v) Bind-Silane (3- (Trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate, Sigma-Aldrich, Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) in ethanol for three minutes and then rinsing with ethanol. The microbeads used with the PAA gels were 0.2 µm diameter carboxylate surface modified fluorescent microbeads (ThermoFisher Scientific, Eugene, OR, USA), made of polystyrene and contained a dark red fluorophore with an excitation peak at 660 nm and an emission peak at 680 nm. The polyacrylamide (PAA) gel (100 µL per coverslip) was prepared from an aqueous solution containing 0.04% (w/v) microbeads, 7.5% (v/v) acrylamide, 0.1% (v/v) bis-acrylamide, 0.05% (w/v) ammonium persulphate solution (APS) and 0.15% tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) that was sandwiched between a collagen I-coated coverslip and an activated coverslip at room temperature for one hour. The collagen I-coated coverslip was then removed from the polymerized PAA gel (which stayed attached to the activated coverslip), after immersing in DPBS for a minimum of 10 min. The resultant collagen I-coated PAA coverslips were stored in DPBS at 4 °C until they were used for live cell imaging.

2.2. Preparation of Soft Silicone

QGel soft silicone-coated coverslips were made by first adding soft silicone (QGel 300, CHT USA Inc., Cassopolis, MI, USA) components A and B at a ratio of 1:2.2 into a weigh boat and mixing them for about 5 min using a thin wooden stick. The mixture was then applied onto square 22 mm glass coverslips to cover its surface with about 0.25 g of the soft silicone mixture per coverslip. Coverslips with silicone were then degassed using a vacuum pump for 10 min and then cured on a hotplate at 100 °C for an hour. After curing, soft silicone-laden coverslips were exposed to 305 nm ultraviolet (UV) light (UVP Crosslinker, Analytik Jena, Upland, CA, USA) for 5 min. A microbead/ECM incubation solution consisting of 0.03% (w/v) microbeads, 10 mg/mL 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC), 10 mg/mL sulfo-N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (sulfo-NHS or sNHS) and 0.017 mg/mL rat tail collagen I (Corning, Bedford, MA, USA) was used to couple microbeads and ECM to the soft silicone by inverting the soft silicone-laden coverslip onto the solution for 30 min. The microbeads used with soft silicones were 0.44 µm diameter carboxylate surface modified fluorescent microbeads (Spherotech Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) made of polystyrene and containing a water-insoluble red fluorophore with an excitation peak at 570 nm and an emission peak at 590 nm. The microbead-coupled soft silicone coverslip was then washed with DPBS and stored in DPBS at 4 °C until it was used for experiments. Another soft silicone made of 1:1 GEL-8100 (NuSil Silicone Technologies, Carpinteria, CA, USA) and 0.55% Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) crosslinker has been characterized using rheology further below. This soft silicone was made similar to the QGel soft silicone and contained components A and B in the ratio 1:1 but differed in the following respects: it included the indicated percentage of the curing agent from Sylgard 184 and was cured at 100 °C for 3 h.

2.3. Cell Culture and Reagents

Madin–Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK II) cells were grown in cell culture medium consisting of DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA), sodium pyruvate, L-Glutamine and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin at 37 °C and under 5% CO2. For TFM experiments, ~105 cells were plated onto soft silicone/PAA substrates in 35 mm culture dishes overnight. Hoechst 33,342, diluted from a 10 mg/mL stock solution in PBS and used at 1:2000 for 15 min with cells, was used as a live stain for nuclei.

2.4. Imaging

Imaging was performed using the 40× objective of a Leica DMi8 epifluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) equipped with a Clara cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Andor Technology, Belfast, Ulster, UK) and an airstream incubator (Nevtek, Williamsville, VA, USA). The mercury metal halide light source (EL6000, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) for fluorescence excitation was connected to the microscope with a liquid light guide. Red fluorescent beads were excited in the band 541–551 nm and emission was collected in the band 565–605 nm. Dark red fluorescent beads were excited in the band 590–650 nm and emission was collected in the band 663–738 nm. The CCD camera had 1392 × 1040 pixels and a 14-bit depth. Exposure times for microbead imaging were in the 100–200 ms range. Cells were imaged using phase contrast microscopy and Hoechst 33342-stained nuclei were used to distinguish single cells from cell pairs.

2.5. Rheology of Soft Silicone

Bulk shear rheology of the soft silicone and PAA gels was characterized using an MCR-302 rheometer (Anton Paar, Ashland, VA, USA). The soft silicone was prepared and cured as above and then loaded between 25 mm diameter parallel plates. For PAA gels, the pre-polymerization mix was loaded between the parallel plates and first allowed to polymerize for 1 h. The storage and loss shear moduli were obtained as a function of angular frequency for 1% strain, which was first determined to be in the linear range using a strain sweep. The shear storage modulus (G′) at 1 rad/s range was considered to be the nominal G′.

2.6. Traction Force Microscopy

Phase images of each cell or cell pair and the corresponding fluorescence images of microbeads beneath, at the substrate surface, were first recorded. For each experiment, the positions of cells (say, 15–20 single cells or cell pairs per experiment) on the coverslip in the chamber (Chamlide, Live Cell Instrument, Namyangju-si, Republic of Korea) on the LMT200 stage (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) were marked into memory via LASX software, version 1.9 (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). To remove cells, 1 mL of cell media from the chamber was replaced with 1 mL of 1% SDS, with the chamber still on the microscope stage. After 10 min, once the cells were disintegrated, stage control was used to revisit each stored cell stage position to record the relaxed substrate microbead images. The microbead fluorescence images with the cell and without the cell were first aligned using an ImageJ (version 1.53t) plugin [40] and then particle image velocimetry (PIV) was used to compute substrate displacements using mpiv (https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/2411-mpiv, accessed on 30 May 2011) scripted in MATLAB and run using MATLAB version R2022a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Traction stresses were then reconstructed using regularized Fourier transform traction cytometry employing the Boussinesq solution [26]. The cell phase images were used to ascertain if the resultant traction stress displayed the expected centripetally directed distribution around the cell periphery. Traction stresses obtained are the in-plane components of the stress acting on the x-y plane. Traction stress multiplied by the unit grid area used for computation (for, e.g., 8 × 8 pixels is equivalent to 1.66 µm2 for a 6.45 µm camera pixel size and a 40× objective) yields the traction force at that location. Note that not all computed traction stress values are rendered in the traction images—they are typically more sparsely rendered in the images to aid visual clarity.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, we address the considerations involved in various aspects of TFM sample preparation as well as imaging and present results that arise from various experimental choices. Representative acceptable and unacceptable TFM outputs presented below should help guide TFM sample preparation, imaging and interpretation, especially using an epifluorescence microscope.

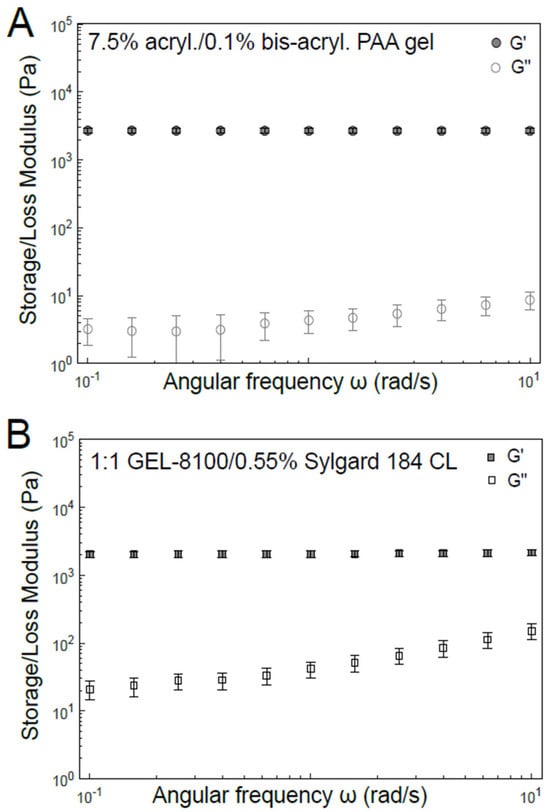

A primary choice that needs to be made for TFM experiments is an appropriate substrate for the cells to adhere to and spread on. This choice directly affects other considerations such as the mechanical properties of the substrate, which in turn influence cell-generated forces, the method to couple and the resultant distribution of microbeads on the substrate and the method to couple ECM onto the substrate. Here, we highlight and detail preparation of the two most widely useful, yet relatively simple, substrates: PAA gels and soft silicones. PAA gels are the most commonly chosen TFM substrates [41,42,43,44,45,46] due to several reasons: PAA gels are (i) chemically and biologically inert, in that protein adsorption and cell adhesion to unmodified PAA surfaces are minimal (ii) optically transparent, enabling microscopy and (iii) linear elastic, which enables the accurate computational reconstruction of the traction stresses from substrate displacements. PAA gels are obtained by the polymerization of solutions containing specific ratios of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide, which in turn specify the Young’s modulus of the gel. As shown in Figure 1A, for a 7.5% acrylamide/0.1% bis-acrylamide PAA gel, the shear elastic (storage) modulus (G′) is essentially constant over the 0.1 to 1 rad/s angular frequency range. PAA gels of different compositions lead to different Young’s moduli, which in turn elicit different degrees of cell spreading and force exertion on these substrates [47,48,49].

Figure 1.

Mechanical characterization of materials typically used as the TFM substrate. Bulk shear rheology of (A) PAA hydrogel of 7.5% acrylamide: 0.1% bis-acrylamide composition and (B) soft silicone 1:1 GEL-8100/0.55% Sylgard 184 crosslinker (CL). Storage shear modulus (G′, filled symbols) and loss shear modulus (G″, open symbols) have been plotted as a function of angular frequency (ω).

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is a widely used polysiloxane (or silicone) that has found extensive use in microfabrication for many decades [50,51,52]. While the composition used for microfabrication needs to result in a stiff polymer amenable for that purpose, mechanobiology studies typically require a more pliable version. Accordingly, softer PDMS formulations (simply referred to as soft silicones here) with elastic moduli in the range of ECM and cells have recently gained prominence (Table 1) [53,54]. Similarly to PAA gels, such soft silicones are also optically transparent but differ in the following respects. Soft silicones are relatively more viscoelastic. However, the loss tangent is small enough (about 1–2%, as shown in Figure 1B) for such soft silicones to be considered elastic at biologically relevant frequencies (~0.1–1 rad/s angular frequency). Soft silicones are also not as chemically inert and adsorb proteins to a much greater extent than PAA gels. This can, in a way, be considered fortuitously beneficial, since ECM proteins can be adsorbed onto their surfaces to some extent without any chemical coupling. While Sylgard 184 can be used with a low crosslinker (i.e., curing agent) fraction to yield Young’s moduli closer to the biological range, other formulations like GEL8100 [53] and Qgel 300 [55,56] more readily yield Young’s moduli similar to tissues, based on the choice of component ratios [57]. Soft silicones can also be used readily as a layer above stiffer PDMS for TFM experiments involving cell stretching [58] due to adhesion between soft and stiff silicones [59]. PAA gels can also be used for this purpose but bring hydraulic effects into play [60].

Table 1.

Some soft silicones used in TFM studies.

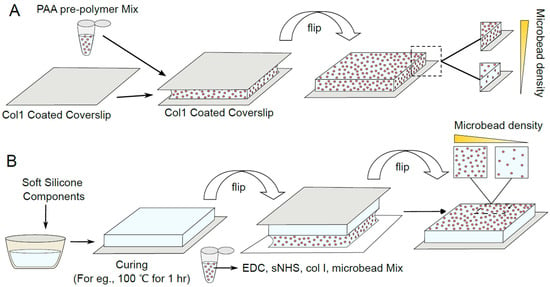

Fluorescent microbeads are typically used as fiducial markers that report on the displacement of localized regions of the substrate. Therefore, these microbeads ought to be either embedded in or coupled to the surface of the substrate. Similarly, the substrate surface ought to be coupled to the ECM to allow cell adhesion to the substrate. We thus outline protocols that we have successfully used to couple beads and ECM to the substrate—either PAA gel or soft silicone—in Figure 2. Briefly, microbeads are embedded in the PAA gel by adding and mixing microbeads in the pre-polymerization mixture. ECM (specifically, collagen I here) adsorbed onto glass is presented as a gel boundary during polymerization, enabling it to be embedded in the gel at the PAA gel surface (Figure 2A). The soft silicone surface, on the other hand, is exposed to 305 nm UV light, followed by incubation with a mixture of microbeads with surface carboxylate groups, ECM (collagen I here), EDC and sulfo-NHS (Figure 2B). Here, exposure to 305 nm UV light can be disregarded if unavailable. Some considerations involved in obtaining a more uniform bead distribution are as follows: Microbeads used in our protocol have carboxylate surface groups and are typically available as 1 or 2% suspensions from manufacturers. When withdrawing a certain volume of this suspension, pipetting the microbead suspension up and down multiple times (at least about 10 times) helps to break down microbead aggregates, resulting in a suspension of nearly uniform single microbeads. Incubation of the soft silicone with the EDC/sNHS/ECM/microbead suspension is performed with the soft silicone upside-down (as in Figure 2B), since some microbead aggregation occurs during this incubation time and this arrangement avoids these aggregates from settling down onto the soft silicone surface via gravity. Microbead suspensions can also be ultrasonicated in a water bath for 10–15 min to break down any aggregates and obtain a more uniform distribution of beads in/on the substrate.

Figure 2.

Schematic depicting the preparation of PAA gel and soft silicone TFM substrates. (A) PAA gel is polymerized while sandwiched between an ECM-coated coverslip and a chemically activated coverslip. PAA gel is doped with fluorescent beads throughout and varying levels of the volumetric bead density in the resultant gel are schematically depicted. (B) Soft silicone is coated on a glass coverslip, cured, and then fluorescent beads and ECM are coupled to the surface using EDC/sNHS chemistry. Varying levels of the bead surface density on the resultant silicone are schematically depicted.

The methods we have outlined here differ in some respects from other experimental methods used for TFM. Many groups have used sulfosuccinimidyl 6-(4′-azido-2′-nitrophenylamino) hexanoate (sulfo-SANPAH) [66], N-6-((acryloyl)amino)hexanoic acid [67] or hydrazine hydrate [68] to couple ECM onto PAA gels. The relative merits of these methods have been previously reported [69]. In our experience, we have found that the sulfo-SANPAH-based coupling of ECM to PAA gels [41,70] results in a rather non-uniform adhesive surface. The coupling of ECM during PAA gel polymerization, as outlined here in Figure 2, is much easier and cheaper than using additional chemical reagents. With respect to silicone substrates, the silicone before curing can be coated onto glass or plastic by spin-coating [54], but this is unnecessary unless the substrate thickness needs to be small enough, in which case the substrate thickness needs to be taken into account in the traction computation. An alternative method using silanization has been used to couple microbeads onto the silicone surface by Teo et al., [54], followed by non-specific ECM adsorption. Non-specific adsorption of ECM on soft silicones is convenient and can be considered a useful alternative to what we outlined in Figure 2. Deep UV exposure of soft silicones has been previously used to couple beads/ECM [57], but care should be taken to check that surface stiffness does not change, since deep UV treatment for more than a few minutes can increase surface stiffness. Other substrates, like gelatin gels [71] and poly-dimethyl-diphenyl-siloxane [64], have been characterized and used for TFM studies by some groups. In comparison, PAA gels enable a larger range of elastic moduli via choice of composition and soft silicones enable a large range of elastic moduli through a proper choice of soft silicone type and composition.

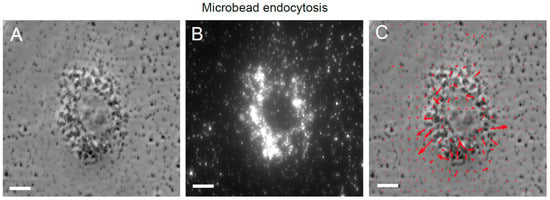

Choice of microbead size is dependent on two main factors: Smaller microbeads can contain a smaller amount of fluorophore and hence result in a dimmer microbead, whereas larger microbeads can more easily become endocytosed by cells. For TFM using epifluorescence microscopy, we have found that it is difficult to obtain well-focused, bright images with microbeads < 0.1 µm in size due to relatively low fluorophore content, although this is less of an issue with soft silicone substrates [65]. However, microbead internalization becomes an issue for microbeads > 0.5 µm in size. Particles greater than about 0.5 µm in size are internalized via phagocytosis or macropinocytosis, while those less than this size are endocytosed via other specific pathways [72]. For instance, we have found that 0.44 µm fluorescent microbeads are typically bright enough to yield good microbead images but are internalized by cells to various extents. Thus, each cell needs to be checked, using the microbead image, for microbead internalization. While a minor level of microbead internalization has little impact on the traction stress field, a large amount of internalization (Figure 3A,B) yields a spurious traction stress field (Figure 3C). We have found that a microbead size range of ~0.1 to 0.4 µm typically allows for enough fluorophore content in microbeads to facilitate epifluorescence imaging, along with low microbead internalization. Again, it is good practice to check for microbead internalization whenever the traction stress field shows centrifugally directed, or otherwise spurious-looking, stress vectors.

Figure 3.

Endocytosis of microbeads and the resultant spurious traction stress map. (A) Phase image of an MDCK cell on a soft silicone substrate. (B) Microbead fluorescence image of the soft silicone surface showing endocytosed microbeads/microbead aggregates. (C) Phase image of the cell superimposed with the resultant traction stress field (red arrows) shows spurious values due to interference from the endocytosed microbeads. Scale bar is 10 μm.

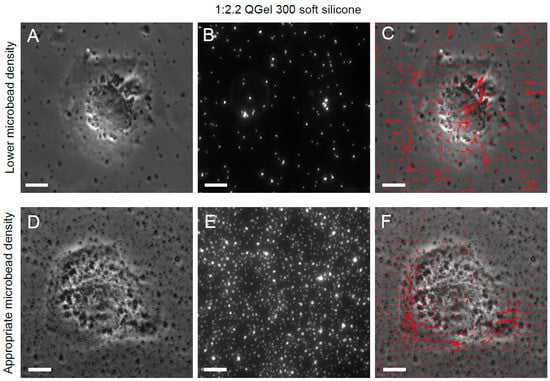

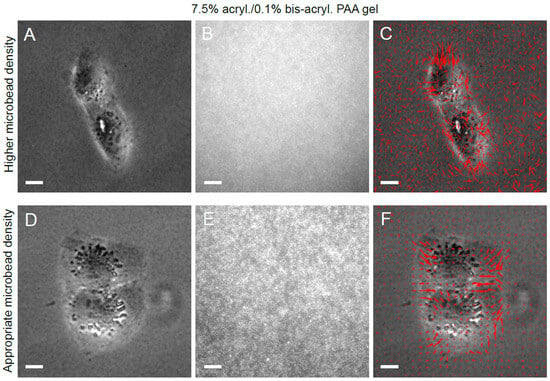

Microbead density is another critical determinant of an accurate resultant traction stress field. If the microbead density is too low (i.e., inter-microbead spacing is not << cell size), as shown in Figure 4A–C for a soft silicone substrate, the displacement field of the substrate top surface is not captured. Hence, the resultant traction stress field is false (Figure 4C). On the other hand, when the microbead density is high (i.e., inter-microbead spacing << cell size), as shown in Figure 4D–F for a soft silicone substrate, the underlying traction stress field is captured well (Figure 4F). For PAA gels, on the other hand, at least as outlined in our protocol, microbeads are distributed throughout the volume of the gel. When using epifluorescence microscopy, the microbead image quality is affected by fluorescence light collected from microbeads deeper in the PAA gel beyond the imaging plane, which is the top surface of the PAA gel. Thus, too high a microbead density in PAA gels can also degrade microbead image quality (Figure 5A–C) and increase noise in the resultant traction stress field (Figure 5C) due to an increased contribution from out-of-plane microbead fluorescence. When the microbead density is appropriate (for, e.g., 0.04% beads in the PAA pre-polymerization mix), the microbead image quality is better (Figure 5D–F) and the resultant traction stress field is more accurate (Figure 5F).

Figure 4.

Effect of sparse soft silicone surface microbead density on resultant traction stress field. (A) Phase image of an MDCK cell on a soft silicone substrate (1:2.2 QGel 300) with a sparse surface microbead density. (B) Microbead fluorescence image showing sparse microbead distribution. (C) Phase image of the cell superimposed with the resultant spurious traction stress field (red arrows). (D) Phase image of an MDCK cell on a soft silicone substrate with sufficiently high surface microbead density. (E) Microbead fluorescence image showing sufficiently high surface microbead density. (F) Phase image of the cell superimposed with the resultant accurate traction stress field (red arrows). Scale bar is 10 μm.

Figure 5.

Effect of PAA gel microbead density on resultant traction stress field. (A) Phase image of an MDCK cell pair on a PAA gel with too high a microbead density. (B) Microbead fluorescence image showing ill-resolved microbeads. (C) Phase image of the cell superimposed with the resultant traction stress field (red arrows) shows increased noise. (D) Phase image of an MDCK cell pair on a PAA gel with appropriate microbead density. (E) Microbead fluorescence image of the PAA gel surface. (F) Phase image of the cell superimposed with the resultant traction stress field (red arrows). Scale bar, 10 μm.

TFM of single cells yields a traction stress field (e.g., Figure 4F) from which scalar measures of traction force levels, such as strain energy and scalar sum of traction forces, can be computed. TFM of cell pairs, such as that shown in Figure 5F, can also yield such measures, but can also be used to compute the inter-cellular force, i.e., the force exerted by each cell on the other, using TFIM. The accuracy of the computed inter-cellular force directly depends on the quality of the traction stress field and, therefore, depends on all the aforementioned factors outlined in this report. Additionally, phase images of cells can sometimes make it difficult to distinguish between single cells and cell pairs. One way to address this is to use a live cell nuclear stain like Hoechst 33342 wherein the number of nuclei stained aids in the identification of cell pairs. Alternately, live cell staining of the plasma membrane can also aid in the identification of cell pairs in addition to accurately identifying cell boundaries. It is, however, always recommended to perform TFM experiments with and without such stains to ensure that such staining does not adversely affect the cells with respect to the variables of interest in a given experiment.

4. Conclusions

To conclude, we have outlined streamlined experimental procedures for performing TFM using epifluorescence microscopy, highlighting common pitfalls to avoid as well as considerations to obtain accurate data. While both PAA gels and soft silicones are suitable TFM substrates whose elasticity can be tuned with composition, their relative features outlined in this article should enable choosing between them based on a particular application. Choice of appropriate fluorescent microbeads in terms of their surface groups as well as diameter is important to enable coupling to the substrate and brightness in epifluorescence imaging, as well as to avoid undesirable endocytosis by cells. Uniform and appropriately dense bead distribution on PAA gel or soft silicone surfaces is also essential to obtain accurate traction stress fields without spurious stress values. An overall distribution of traction stress vectors concentrated at the cell periphery and showing centripetal orientation often indicates a reasonable traction stress map but may still be inaccurate if the microbead image is obtained from a plane below the surface plane of the substrate, as assumed in typical computational traction reconstruction approaches. Thus, attention paid to all experimental steps, as well as careful image acquisition and scrutiny of raw image data as outlined here, can increase the likelihood of obtaining accurate traction stress data from TFM as well as inter-cellular force data from cell pairs using TFIM.

Author Contributions

Z.B.—Investigation, Methodology, Writing (original draft, review and editing); M.M.—Investigation, Methodology; R.P.—Investigation, Methodology; V.M.—Supervision, Writing (original draft, review and editing). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NIH grant number R15GM116082.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This investigation was conducted using an immortalized cell line. Therefore, no ethics approval was required.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Burridge, K.; Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M. Focal adhesions, contractility, and signaling. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996, 12, 463–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charras, G.; Yap, A.S. Tensile Forces and Mechanotransduction at Cell-Cell Junctions. Curr. Biol. CB 2018, 28, R445–R457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.S.; Tan, J.; Tien, J. Mechanotransduction at Cell-Matrix and Cell-Cell Contacts. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2004, 6, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, A.D.; Petrie, R.J.; Kutys, M.L.; Yamada, K.M. Dimensions in cell migration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2013, 25, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, A.; Lee, O.; Win, Z.; Edwards, R.M.; Alford, P.W.; Kim, D.H.; Provenzano, P.P. Anisotropic forces from spatially constrained focal adhesions mediate contact guidance directed cell migration. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashirzadeh, Y.; Poole, J.; Qian, S.; Maruthamuthu, V. Effect of pharmacological modulation of actin and myosin on collective cell electrotaxis. Bioelectromagnetics 2018, 39, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liberali, P. Collective behaviours in organoids. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2021, 72, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labernadie, A.; Kato, T.; Brugues, A.; Serra-Picamal, X.; Derzsi, S.; Arwert, E.; Weston, A.; Gonzalez-Tarrago, V.; Elosegui-Artola, A.; Albertazzi, L.; et al. A mechanically active heterotypic E-cadherin/N-cadherin adhesion enables fibroblasts to drive cancer cell invasion. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamed, I.; Chowdhury, F.; Maruthamuthu, V. Biophysical Tools to Study Cellular Mechanotransduction. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.S.; Thomas, W.A.; Eder, O.; Pincet, F.; Perez, E.; Thiery, J.P.; Dufour, S. Force measurements in E-cadherin-mediated cell doublets reveal rapid adhesion strengthened by actin cytoskeleton remodeling through Rac and Cdc42. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 167, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashoff, C.; Hoffman, B.D.; Brenner, M.D.; Zhou, R.; Parsons, M.; Yang, M.T.; McLean, M.A.; Sligar, S.G.; Chen, C.S.; Ha, T.; et al. Measuring mechanical tension across vinculin reveals regulation of focal adhesion dynamics. Nature 2010, 466, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraning-Rush, C.M.; Carey, S.P.; Califano, J.P.; Reinhart-King, C.A. Quantifying traction stresses in adherent cells. Methods Cell Biol. 2012, 110, 139–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lui, C.; Jung, W.H.; Maity, D.; Ong, C.S.; Bush, J.; Maruthamuthu, V.; Hibino, N.; Chen, Y. Mechanical Characterization of hiPSC-Derived Cardiac Tissues for Quality Control. Adv. Biosyst. 2018, 2, 1800251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.L.; Tien, J.; Pirone, D.M.; Gray, D.S.; Bhadriraju, K.; Chen, C.S. Cells lying on a bed of microneedles: An approach to isolate mechanical force. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisin, A.K.; Kim, H.; Riedel-Kruse, I.H.; Pruitt, B.L. Field Guide to Traction Force Microscopy. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2024, 17, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekka, M.; Gnanachandran, K.; Kubiak, A.; Zieliński, T.; Zemła, J. Traction force microscopy—Measuring the forces exerted by cells. Micron 2021, 150, 103138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayrard, C.; Borghi, N. FRET-based Molecular Tension Microscopy. Methods 2016, 94, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghi, N.; Sorokina, M.; Shcherbakova, O.G.; Weis, W.I.; Pruitt, B.L.; Nelson, W.J.; Dunn, A.R. E-cadherin is under constitutive actomyosin-generated tension that is increased at cell–cell contacts upon externally applied stretch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12568–12573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Rahil, Z.; Li, I.T.; Chowdhury, F.; Leckband, D.E.; Chemla, Y.R.; Ha, T. Constructing modular and universal single molecule tension sensor using protein G to study mechano-sensitive receptors. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, B.C.H.; Abbed, R.J.; Wu, M.; Leggett, S.E. 3D Traction Force Microscopy in Biological Gels: From Single Cells to Multicellular Spheroids. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 26, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyjanova, J.; Hannen, E.; Bar-Kochba, E.; Darling, E.M.; Henann, D.L.; Franck, C. 3D Viscoelastic traction force microscopy. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 8095–8106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanoë-Ayari, H.; Hiraiwa, T.; Marcq, P.; Rieu, J.P.; Saw, T.B. 2.5D Traction Force Microscopy: Imaging three-dimensional cell forces at interfaces and biological applications. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2023, 161, 106432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumberg, J.W.; Schwarz, U.S. Comparison of direct and inverse methods for 2.5D traction force microscopy. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zancla, A.; Mozetic, P.; Orsini, M.; Forte, G.; Rainer, A. A primer to traction force microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, U.S.; Balaban, N.Q.; Riveline, D.; Bershadsky, A.; Geiger, B.; Safran, S.A. Calculation of Forces at Focal Adhesions from Elastic Substrate Data: The Effect of Localized Force and the Need for Regularization. Biophys. J. 2002, 83, 1380–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabass, B.; Gardel, M.L.; Waterman, C.M.; Schwarz, U.S. High resolution traction force microscopy based on experimental and computational advances. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Redondo, J.C.; Weber, A.; Vivanco, M.D.; Toca-Herrera, J.L. Measuring (biological) materials mechanics with atomic force microscopy. 5. Traction force microscopy (cell traction forces). Microsc. Res. Tech. 2023, 86, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, S.S.; Jeong, J.H.; Ban, M.J.; Park, J.H.; Yoon, J.K.; Hwang, Y. Traction force microscopy for understanding cellular mechanotransduction. BMB Rep. 2020, 53, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stricker, J.; Aratyn-Schaus, Y.; Oakes, P.W.; Gardel, M.L. Spatiotemporal constraints on the force-dependent growth of focal adhesions. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 2883–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Guo, C.; Yang, X.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wen, G.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Xiong, C.; et al. Super-resolution traction force microscopy with enhanced tracer density enables capturing molecular scale traction. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, L.; Colin-York, H.; Korobchevskaya, K.; Li, D.; Wolfson, D.L.; Karedla, N.; Schneider, F.; Ahluwalia, B.S.; Seternes, T.; Dalmo, R.A.; et al. Two-dimensional TIRF-SIM-traction force microscopy (2D TIRF-SIM-TFM). Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin-York, H.; Javanmardi, Y.; Barbieri, L.; Li, D.; Korobchevskaya, K.; Guo, Y.; Hall, C.; Taylor, A.; Khuon, S.; Sheridan, G.K.; et al. Spatiotemporally Super-Resolved Volumetric Traction Force Microscopy. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 4427–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, A.; Yeh, Y.T.; Serrano, R.; Mercola, M.; Del Alamo, J.C. Uncertainty-aware traction force microscopy. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1013079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, F.S.; Möllerherm, L.; Kierfeld, J. Enhancing robustness, precision, and speed of traction force microscopy with machine learning. Biophys. J. 2023, 122, 3489–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, U.S.; Soine, J.R. Traction force microscopy on soft elastic substrates: A guide to recent computational advances. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 3095–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suñé-Auñón, A.; Jorge-Peñas, A.; Aguilar-Cuenca, R.; Vicente-Manzanares, M.; Van Oosterwyck, H.; Muñoz-Barrutia, A. Full L(1)-regularized Traction Force Microscopy over whole cells. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Lin, Y.C. Traction force microscopy by deep learning. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 3079–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthamuthu, V.; Gardel, M.L. Protrusive activity guides changes in cell-cell tension during epithelial cell scattering. Biophys. J. 2014, 107, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Schlue, K.T.; Kniffin, A.F.; Mayer, C.R.; Duke, A.A.; Narayanan, V.; Arsenovic, P.T.; Bathula, K.; Danielsson, B.E.; Dumbali, S.P.; et al. Spatial Proliferation of Epithelial Cells Is Regulated by E-Cadherin Force. Biophys. J. 2018, 115, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiel, J.L.; Leal, A.; Kurzawa, L.; Balland, M.; Wang, I.; Vignaud, T.; Tseng, Q.; Thery, M. Measurement of cell traction forces with ImageJ. Methods Cell Biol. 2015, 125, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-González, B.; Zhang, S.; Gómez-González, M.; Meili, R.; Firtel, R.A.; Lasheras, J.C.; Del Álamo, J.C. Two-Layer Elastographic 3-D Traction Force Microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Tofangchi, A.; Anand, S.V.; Saif, T.A. A novel cell traction force microscopy to study multi-cellular system. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Windoffer, R.; Kozyrina, A.N.; Piskova, T.; Di Russo, J.; Leube, R.E. Combining Image Restoration and Traction Force Microscopy to Study Extracellular Matrix-Dependent Keratin Filament Network Plasticity. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 901038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbali, S.P.; Mei, L.; Qian, S.; Maruthamuthu, V. Endogenous Sheet-Averaged Tension Within a Large Epithelial Cell Colony. J. Biomech. Eng. 2017, 139, 101008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eftekharjoo, M.; Palmer, D.; McCoy, B.; Maruthamuthu, V. Fibrillar force generation by fibroblasts depends on formin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 510, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, J.; Maruthamuthu, V. In situ determination of exerted forces in magnetic pulling cytometry. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 035221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Jeong, H.; Lee, C.; Lee, M.J.; Delmo, B.R.; Heo, W.D.; Shin, J.H.; Park, Y. High-resolution assessment of multidimensional cellular mechanics using label-free refractive-index traction force microscopy. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendenmann, T.; Schneider, T.; Dumas, J.; Tarini, M.; Giampietro, C.; Bajpai, A.; Chen, W.; Gerber, J.; Poulikakos, D.; Ferrari, A.; et al. Cellogram: On-the-Fly Traction Force Microscopy. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 6742–6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualini, F.S.; Agarwal, A.; O’Connor, B.B.; Liu, Q.; Sheehy, S.P.; Parker, K.K. Traction force microscopy of engineered cardiac tissues. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashirzadeh, Y.; Maruthamuthu, V.; Qian, S. Electrokinetic Phenomena in Pencil Lead-Based Microfluidics. Micromachines 2016, 7, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hockenberry, M.A.; Ulmer, A.J.; Rapp, J.L.; Leibfarth, F.A.; Bear, J.E.; Legant, W.R. Measurement of cellular traction forces during confined migration. bioRxiv, 2024; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, D.C.; McDonald, J.C.; Schueller, O.J.; Whitesides, G.M. Rapid Prototyping of Microfluidic Systems in Poly(dimethylsiloxane). Anal. Chem. 1998, 70, 4974–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekharjoo, M.; Mezher, M.; Chatterji, S.; Maruthamuthu, V. Epithelial Cell-Like Elasticity Modulates Actin-Dependent E-Cadherin Adhesion Organization. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 2455–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, J.L.; Lim, C.T.; Yap, A.S.; Saw, T.B. A Biologist’s Guide to Traction Force Microscopy Using Polydimethylsiloxane Substrate for Two-Dimensional Cell Cultures. STAR Protoc. 2020, 1, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezher, M.; Dumbali, S.; Fenn, I.; Lamb, C.; Miller, C.; Sharmin, S.; Cabe, J.I.; Bejar-Padilla, V.; Conway, D.; Maruthamuthu, V. Vinculin is Essential For Sustaining Normal Levels of Endogenous Force Transmission at Cell-Cell Contacts. Biophys. J. 2023, 122, 4518–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejar-Padilla, V.; Cabe, J.I.; Lopez, S.; Narayanan, V.; Mezher, M.; Maruthamuthu, V.; Conway, D.E. Alpha-Catenin-dependent vinculin recruitment to adherens junctions is antagonistic to focal adhesions. Mol. Biol. Cell 2022, 33, ar93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashirzadeh, Y.; Chatterji, S.; Palmer, D.; Dumbali, S.; Qian, S.; Maruthamuthu, V. Stiffness Measurement of Soft Silicone Substrates for Mechanobiology Studies Using a Widefield Fluorescence Microscope. JoVE 2018, 137, e57797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashirzadeh, Y.; Dumbali, S.; Qian, S.; Maruthamuthu, V. Mechanical Response of an Epithelial Island Subject to Uniaxial Stretch on a Hybrid Silicone Substrate. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2019, 12, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashirzadeh, Y.; Qian, S.; Maruthamuthu, V. Non-intrusive measurement of wall shear stress in flow channels. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2018, 271, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casares, L.; Vincent, R.; Zalvidea, D.; Campillo, N.; Navajas, D.; Arroyo, M.; Trepat, X. Hydraulic fracture during epithelial stretching. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergert, M.; Lendenmann, T.; Zündel, M.; Ehret, A.E.; Panozzo, D.; Richner, P.; Kim, D.K.; Kress, S.J.; Norris, D.J.; Sorkine-Hornung, O.; et al. Confocal reference free traction force microscopy. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Style, R.W.; Boltyanskiy, R.; German, G.K.; Hyland, C.; MacMinn, C.W.; Mertz, A.F.; Wilen, L.A.; Xu, Y.; Dufresne, E.R. Traction force microscopy in physics and biology. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 4047–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshie, H.; Koushki, N.; Kaviani, R.; Tabatabaei, M.; Rajendran, K.; Dang, Q.; Husain, A.; Yao, S.; Li, C.; Sullivan, J.K.; et al. Traction Force Screening Enabled by Compliant PDMS Elastomers. Biophys. J. 2018, 114, 2194–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terdik, J.Z.; Weitz, D.A.; Spaepen, F. Ultrasoft silicone gels with tunable refractive index for traction force microscopy. Soft Matter 2024, 20, 4633–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, E.; Tkachenko, E.; Besser, A.; Sundd, P.; Ley, K.; Danuser, G.; Ginsberg, M.H.; Groisman, A. High Refractive Index Silicone Gels for Simultaneous Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence and Traction Force Microscopy of Adherent Cells. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, F.; Sengupta, K.; Puech, P.H. Protocol for measuring weak cellular traction forces using well-controlled ultra-soft polyacrylamide gels. STAR Protoc. 2022, 3, 101133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhart-King, C.A.; Dembo, M.; Hammer, D.A. The dynamics and mechanics of endothelial cell spreading. Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridharan Weaver, S.; Li, Y.; Foucard, L.; Majeed, H.; Bhaduri, B.; Levine, A.J.; Kilian, K.A.; Popescu, G. Simultaneous cell traction and growth measurements using light. J. Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201800182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aratyn-Schaus, Y.; Oakes, P.W.; Stricker, J.; Winter, S.P.; Gardel, M.L. Preparation of compliant matrices for quantifying cellular contraction. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2010, 46, e2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubb, A.; Laine, R.F.; Miihkinen, M.; Hamidi, H.; Guzmán, C.; Henriques, R.; Jacquemet, G.; Ivaska, J. Fluctuation-Based Super-Resolution Traction Force Microscopy. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 2230–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, A.D.; Lee, J. Simultaneous, real-time imaging of intracellular calcium and cellular traction force production. Biotechniques 2002, 33, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Mg, S.; Mayor, S. Endocytosis unplugged: Multiple ways to enter the cell. Cell Res. 2010, 20, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).