1. Introduction

Ranked fifth among the most exported plant-based products by Brazil, coffee is one of the commodities that has significantly contributed to the expansion of agribusiness exports in 2023, according to a report by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Supply (MAPA).

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Brazil is the largest producer of Arabica coffee (

Coffea arabica) and ranks second in Robusta coffee (

Coffea canephora) production, popularly known as Conilon variety, behind only Vietnam. Globally, Brazil occupies the first position in the ranking, considering both types (

Arabica and

Canephora), thus becoming the largest coffee producer in the world (United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service June 2023 Coffee: World Markets and Trade (

https://fas.usda.gov/data/coffee-world-markets-and-trade-06222023), accessed on 22 September 2025).

In an increasingly demanding consumer market, in addition to the volume of sacks produced, the quality of coffee beans is crucial to secure a larger market share. One way to ensure the high quality of the product is through understanding the plant’s water relations, aiming to keep it consistently hydrated, thus ensuring a final product of high quality.

With the growing demand in both national and international consumer markets, maintaining production requires ensuring adequate hydration of the plant, which is essential for delivering a high-quality final product. The traditional way to measure plant hydration is through a pressure chamber, known as a Scholander Chamber, where the value of the water potential is determined by samples of leaves collected from plants that are subjected to different pressure levels. However, this measurement method implies a time-consuming process, must be estimated at a specific time (between 4:00 and 5:00 a.m.), requires specialized labor, in addition to being a destructive test and may pose a risk to the operator. Due to these limitations, alternative methods for indirectly measuring plant water conditions have been proposed, based on spectral signatures [

1]. Although water potential is a physiologically robust indicator of plant hydration, it remains highly unusual, impractical, and laborious for farmers, as measurements require pre-dawn sampling, destructive leaf excision, and specialized pressure-chamber equipment operated under strict safety conditions. For this reason, more accessible proxies are commonly preferred in applied or commercial settings. Importantly, however, a variety of hydration indices are physically interrelated with

, meaning that alternative metrics often reflect the same underlying physiological state. Indicators such as relative water content (RWC), gravimetric water content (WC) or mass loss, dielectric or impedance-based measurements, and low-field NMR parameters represent complementary facets of plant hydration. These measures are inherently connected: pressure-volume relations link RWC directly with

, while progressive water loss simultaneously reduces water content and alters dielectric behavior and LF-NMR signatures. Consequently, a monotonic correspondence between

and these alternative indicators is generally expected, even though each quantifies a different dimension of water status (amount vs. potential vs. mobility) [

2].

Spectral signature analysis can provide various information regarding different aspects related to plant health [

3,

4]. These aspects are studied by experts in the field to ensure the relevance of the information. Thus, certain reflectances in the spectral signature have a relationship with the plant’s water status, which may be linear or nonlinear to varying degrees, depending on the wavelength of the spectral signature. Thus, it is expected that artificial intelligence-based models may be used in an attempt to estimate plant characteristics indirectly.

In the study reported in [

5], the aim was to determine the effect of water stress on maize (

Zea mays L.) using spectral indices, chlorophyll readings, and consequently, evaluate reflectance spectra. Similarly, in the study of [

6], coffee plants in irrigated and non-irrigated crops had their spectral indices measured and used to determine the water conditions of the coffee plants applying artificial neural networks and decision tree algorithms, obtaining simple and efficient predictive models. Unlike these, ref. [

7] used geostatistical analysis (via semivariograms) to investigate the spatial dependence of the leaf water potential. The study reported in [

8] evaluated the relationship between water potential and coffee canopy temperature obtained by a thermal camera mounted on a remotely piloted aircraft. Results showed that a decrease in WP was associated with stomatal closure and reduced stomatal conductance, leading to an increase in canopy temperature due to water deficit.

Current studies estimating coffee plant water potential face several limitations, including restricted spectral resolution of low-cost sensors, sensitivity to environmental conditions, limited accuracy at the leaf scale, coarse and infrequent satellite observations, and poor model generalization across regions. These challenges indicate that water potential estimation in coffee remains an open research area, encouraging the development of more robust and scalable approaches.

In order to explore a different approach from the works of [

5,

6], the current study did not address spectral indices. Spectral indices, despite their widespread use, have limitations that can affect the accuracy of water potential estimation. The primary limitation lies in their reductionist nature, as they condense the complexity of the reflectance spectrum into a single value. This simplification can obscure relevant information about the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with the leaf, especially in situations of moderate to severe water stress [

9]. In addition, the indices are calculated from specific spectral bands, focusing on predetermined characteristics, which can lead to the loss of relevant information, which inevitably occurs when the captured window is restricted [

10]. According to [

10,

11], the analysis of a larger window of the reflectance spectrum offers a more holistic and detailed view of the interactions between electromagnetic radiation and the leaf.

In contrast to previous studies based on spectral indices, this study employed full-spectrum data in combination with multiple models to predict the water potential of coffee plants, enabling a more detailed and comprehensive analysis of the interactions between electromagnetic radiation and leaf reflectance. Additionally, it explored which specific wavelength or range of wavelengths was best suited for inferring the water potential of coffee plants.

The present study addresses the implementation of four machine learning techniques to estimate and classify the water potential of coffee plants: Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Decision Tree, Random Forest, and K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN). Using these techniques for regression and classification tasks is valuable due to their diverse learning mechanisms, which allow for robust performance across varying data structures and complexities [

12,

13]. A Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is a type of artificial neural network composed of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, where each layer consists of interconnected neurons that use non-linear activation functions to model complex relationships in data [

14]. According to the Universal Approximation Theorem, an MLP can approximate any continuous function to an arbitrary degree of accuracy with sufficient hidden neurons, making it highly versatile for modeling complex, non-linear relationships in data [

14]. In summary, the decision trees present tree-like structures composed of a set of interconnected nodes. Each internal node tests input attributes as decision constants and determines the next descendant node [

15]. They are computationally simple in the operating phase and more interpretable than neural networks, which are often regarded as black-box models. Random Forest is an ensemble technique widely recognized in the literature for its ability to increase model complexity by incorporating new data while maintaining strong generalization performance. Ensemble methods consist of a collection of classifiers; in the case of Random Forest, it utilizes a set of decision trees that determine the final prediction through a majority voting process [

16]. Finally, the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) is a simple, instance-based learning algorithm that classifies data points based on the majority label of their nearest neighbors, offering advantages such as ease of implementation, flexibility, and effectiveness in handling non-linear data distributions. As a regressor, KNN predicts continuous values by averaging the outcomes of its nearest neighbors, offering advantages such as simplicity, non-parametric nature, and the ability to model complex, non-linear relationships without requiring explicit assumptions about the data [

17].

The reminder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the methodology employed, where the database used is presented and the steps to design the proposed models are described.

Section 3 presents the achieved results and discussions. Finally,

Section 4 presents the final conclusions and gives directions for future works.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the database details, the data pre-processing, the design of the models and the metrics used for performance evaluation.

2.1. Database

The data were collected in an experiment set up on a private rural property in the municipality of Diamantina, located in the northern region of the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The experimental design was a randomized complete block with split-strip plots, consisting of 10 Coffea arabica genotypes provided by the coffee breeding program of EPAMIG (Empresa de Pesquisa Agropecuária de Minas Gerais), two irrigation systems, and four blocks. Each experimental plot comprised six plants, and the experiment was conducted at a spacing of 3.7 m × 0.6 m. Two types of management of coffee plants were considered: irrigated and rainfed.

The irrigation system was gravity-driven drip, with drippers delivering and spaced every 75 cm. The drip lines were supplied by a 75 mm PVC pipe, and water was sourced from a local reservoir. The emitter flow rate was (equivalent to ), and irrigation was applied for approximately two hours per day. Irrigation was managed to replace crop evapotranspiration, as measured by a local automatic weather station.

The experiment, including both irrigated and rainfed systems, was established in March 2014, when the plants were 24 months old. In the irrigated system, plants continued to receive water through the drip system. In contrast, under rainfed management, the irrigation hoses were disconnected in the corresponding plots to impose water deficit, and coffee plants relied exclusively on natural precipitation for hydration, with no artificial irrigation applied. Fertilization in the irrigated treatments was performed via fertigation, whereas in the rainfed treatments, fertilization was carried out conventionally by surface application beneath the coffee canopy, following recommended guidelines.

To capture the effect of seasonal climate variations, data were collected when the plants were 25 months old (April 2014), 26 months (May 2014), 30 months (September 2014), 34 months (January 2015), 36 months (March 2015), 39 months (June 2015), 41 months (August 2015), 42 months (September 2015), 44 months (November 2015), 48 months (March 2016), 53 months (August 2016), and 54 months (September 2016). The database was provided by the field research team of EPAMIG and presents spectral characteristics and the corresponding water potential of each coffee plant. Leaf samples were collected from the same marked plants across all sampling periods, with each genotype corresponding to a single, permanently identified plant. Repeated measurements therefore represent longitudinal data from the same genotypic individual, ensuring that temporal variations reflect physiological or environmental effects rather than genotypic differences. Each genotype (i.e., marked plant) was treated as a biological replicate in the statistical analyses to account for the repeated-measures design. Leaves from the third or fourth pair of plagiotropic branches in the middle third of the coffee plant, on the sun-exposed side facing east, were collected between 3:00 and 5:00 a.m.

Pre-dawn water potential () measurements were made using the Scholander-type pressure chamber (PMS Instruments Plant Moisture-Model 1000, PMS Instrument Company, Albany, OR, USA). The leaves collected in the field were inserted into the chamber using an appropriately sized gasket, and subsequently pressure was applied until exudation occurred from the cut leaf petiole.

Leaf reflectance spectra were measured using a CI-710 miniaturized leaf spectrometer (CID Bio-Science, Camas, WA, USA), which illuminates the adaxial surface of the coffee leaf with blue LED light and an incandescent lamp, providing output across the visible to near-infrared range (400–1000 nm). Spectral data were analyzed using SpectraSnap software (version 1.1.3.150, CID Bio-Science, Camas, Washington, DC, USA) with an integration time of 900 ms. Measurements were conducted following preliminary calibration of the device according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The database was composed of 437 samples of irrigated coffee and 445 of rainfed. Each sample consisted of 2863 attributes, which were defined by the collection date, genotype/cultivar number, the repetition for the corresponding genotype/cultivar, and the reflectance sequence corresponding to the wavelength range from 400 to 950 nm. Although the device is nominally specified to operate within the 400–1000 nm range, its spectral response exhibits decreased precision and increased noise beyond approximately 950 nm. Consequently, the analyses were restricted to the 400–950 nm region to ensure data quality and reproducibility. Furthermore, each sample from both databases had the corresponding water potential (), measured with a Scholander Pressure Chamber.

2.2. Pre-Processing

For the preprocessing stage, we adopted the median filtering method developed by [

18], which aims to smooth impulsive noise in digital signals and images [

19]. The median filter operates by determining a window of

N samples, where the

N values were arranged in ascending order. The median is the value located precisely in the middle of the sample, and the median filter replaces the “problematic” value with the median of the window. In this work, a fourth-order median filter was implemented.

Subsequently, the dataset was normalized using a scaling method to the range [0, 1], according to Equation (

1).

where

Pn corresponds to the normalized value of variable

n,

P,

Pmin, and

Pmax represent the original, minimum, and maximum values, respectively [

20].

An important aspect of preprocessing in pattern recognition and regression methods is the feature selection. For this stage, the technique used was the Pearson’s coefficient, which measures the degree of linear correlation between two variables. This coefficient, typically represented by

, takes values only between −1 and 1.

Table 1 displays the interpretation of the Pearson’s coefficient (

) values [

21,

22].

2.3. Model Design

Following data normalization and the selection of the most relevant features, four machine learning techniques—Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Decision Tree, Random Forest, and K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)—were implemented to estimate the water potential of coffee plants. Additionally, the regression problem was converted into a classification task by segmenting the water potential values into discrete classes. The classes were defined according to the work of [

23] and are shown in

Table 2.

The datasets corresponding to irrigated and rainfed management systems differ due to varying levels of water stress. The rainfed management dataset exhibits water potential values ranging from −0.25 MPa to −6.60 MPa, covering all values listed in

Table 2. Consequently, when classes are assigned to this dataset, the samples under rainfed conditions are distributed across five distinct classes. In contrast, the irrigated management dataset, characterized by lower water stress, shows water potential values ranging from −0.20 MPa to −2.40 MPa, covering only the first three classes.

The number of samples per class for both datasets (rainfed and irrigated conditions) is presented in

Table 3. Note that both datasets have imbalanced classes, which makes the classification problem more complex. Imbalanced classes pose challenges for pattern recognition by biasing models towards the majority class, often leading to reduced accuracy and poor performance on minority class predictions. To deal with this issue, we applied the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) [

24] to create synthetic data, however, the results showed a decreasing in the classification performance with the use of SMOTE (See

Appendix A). This reduction was likely due to the synthetic samples not fully capturing the spectral variability of the real data, which introduced noise and reduced the models’ generalization ability. Thus, we decided to not use SMOTE and to perform a stratified division of the data into training and testing sets. The division was conducted using the Cross-Validation technique [

25], with five folds, so that for each fold, one is chosen for testing and the other four for training. The methods were implemented via MATLAB software (version 2011). To optimize the classifiers and predictors, the hyperparameters were adjusted to identify the most parsimonious models. Consequently, each model was run 30 times, resulting in a total of 150 executions for each machine learning method.

Furthermore, classes 1, 4, and 5 have fewer samples compared to the others in the rainfed condition dataset (see

Table 3). This may hinder the learning and generalization process of some classifiers that require more samples to converge. The KNN classifier is suitable for small datasets, since it does not require explicit training [

12]. It relies on the distances between data points, which means its performance can be competitive with limited data if the feature space is well-defined. Also, decision trees are interpretable and perform well on small datasets. They can easily fit the data, even with complex relationships, without requiring large amounts of training data [

12].

Figure 1 illustrates the steps of the design of the proposed approaches. Note that the preprocessing stage (data normalization and feature selection) follows the same procedure for both regression and classification approaches.

2.4. Evaluation and Performance Metrics

For performance evaluation, confusion matrices were used for the classification approaches. In addition, the balanced accuracy was utilized. It is a performance evaluation metric particularly useful when the classes in a classification problem are imbalanced. Equation (

2) shows how to calculate the balanced accuracy.

where

N is the number of classes in the dataset,

and

refer to the true positives and false negatives of class

i, respectively. Balanced accuracy aims to reduce bias caused by class imbalance by averaging the individual accuracies of each class, giving equal weight to all classes regardless of their size.

For the regression approaches, the root mean squared error (

RMSE) was used (see Equation (

3)). It is a standard metric used to evaluate the accuracy of a model by measuring the differences between predicted and observed values. Since errors are squared before averaging,

RMSE places greater weight on larger errors. A lower

RMSE indicates better model performance, with perfect predictions yielding an

RMSE of 0 [

26,

27].

where

is the estimated value of

(observed value).

The coefficient of determination was also employed as a metric for the regression approaches, as shown in Equation (

4). It is a number between 0 and 1 that measures how well a model predicts an outcome and can be understood as the percentage of data variation explained by the model. Therefore, the higher the

, the more explanatory the model is, meaning it fits the data better [

28,

29].

where

is the mean value of the observations.

3. Results

The Pearson correlation coefficient () was calculated to assess the relationship between the attributes and the target variable (water potential). For data under irrigated conditions, a threshold of was applied, where attributes with were deemed irrelevant for the model. This threshold reduced the number of attributes from 2863 dimensions to 22. For data under rainfed conditions, a higher threshold of , indicating a moderate correlation, was used. In this case, the number of attributes was reduced from 2863 dimensions to 20. The thresholds for both irrigated and rainfed conditions were determined experimentally, with the primary goal of identifying more parsimonious models. To this end, we varied the correlation threshold from to . The selected values ( for irrigated and for rainfed) corresponded to the models that achieved the best trade-off between accuracy and complexity.

Finally, the ten most relevant attributes for both conditions were selected. They are shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5, corresponding to the irrigated and rainfed conditions, respectively.

The results in

Table 4 indicate that reflectance values near the 780 nm wavelength are the most significant under irrigated conditions. This finding is consistent with previous studies [

30,

31], which report that the spectral signature of vegetative targets—particularly hydrated green leaves—exhibits high reflectance in the Near-Infrared (NIR) range (700–1300 nm). In the infrared region (720–1100 nm), these interactions are primarily associated with mesophyll structure and variations in leaf water content [

32,

33]. This occurs because liquid water strongly absorbs solar radiation in the NIR (720–1000 nm) and Shortwave Infrared (SWIR, 1000–2500 nm) bands. In a study of spring wheat, hyperspectral data revealed that the 780 nm and 1750 nm bands were sensitive to water-related parameters, with both wavelengths showing strong positive correlations with soil water potential, soil relative moisture, and canopy water content [

30].

Under rainfed conditions, however, wavelengths around 690 nm were identified as the most prominent (

Table 5), highlighting them as critical bands for analysis. In the visible spectrum, wavelengths between 650 nm and 700 nm correspond to the red region of light. This observation agrees with existing literature [

30,

31], which reports that coffee plants grown under rainfed conditions tend to exhibit higher reflectance in this range. Healthy vegetation, by contrast, strongly absorbs light in this region due to chlorophyll a, which exhibits peak absorption at approximately 680 nm. This correlation supports the observed results, as coffee leaves under rainfed conditions often display a brownish or reddish hue.

Drought stress significantly affects several physiological parameters in more sensitive coffee genotypes, reducing relative leaf water content, net assimilation rate, stomatal conductance, and chlorophyll pigments compared to well-watered conditions [

31]. Although the NIR and red bands are not directly correlated with water content, they are linked to chlorophyll concentration, green leaf biomass, and photosynthetic activity—parameters that are negatively affected by drought stress [

34,

35]. Consistent with our observations, in spring wheat, VIS and SWIR reflectance were reported to increase with decreasing soil water content, whereas NIR reflectance increased with higher soil water content [

30].

After the execution of preprocessing and feature selection steps, the machine learning models (MLP, Decision Tree, Random Forest, and KNN) were implemented considering all selected features as input variables. After that, the classification and regression models were designed considering only the ten and five most relevant features.

3.1. Irrigated Condition

3.1.1. Results for the Regression Models

The

RMSE and

values were computed for all executions. For each fold (in the context of the k-fold cross validation), the best result was selected among the 30 executions. The results of mean (

) and standard deviation (

), considering the 5 folds of the k-fold cross validation, are displayed in

Table 6, for the selected 22 features, and for the 10 and 5 most relevant features. A stratified k-fold cross-validation procedure was implemented using the

cvpartition function of MATLAB with the k-fold parameter set to five, ensuring that the proportional representation of classes was maintained across all folds. This approach minimizes potential bias arising from unequal class distributions during model training and testing. However, no fixed random seed was applied, meaning that fold assignment was based on the software’s default randomization routine. Consequently, while the procedure is fully reproducible within the same computational environment and configuration, minor variations may occur if the randomization process is reinitialized.

Analyzing the results from

Table 6, it can be observed that the Decision Tree achieved the best result among the three attribute options, with a mean root mean squared error value (

) of 0.3884 ± 0.0299 and a coefficient of determination (

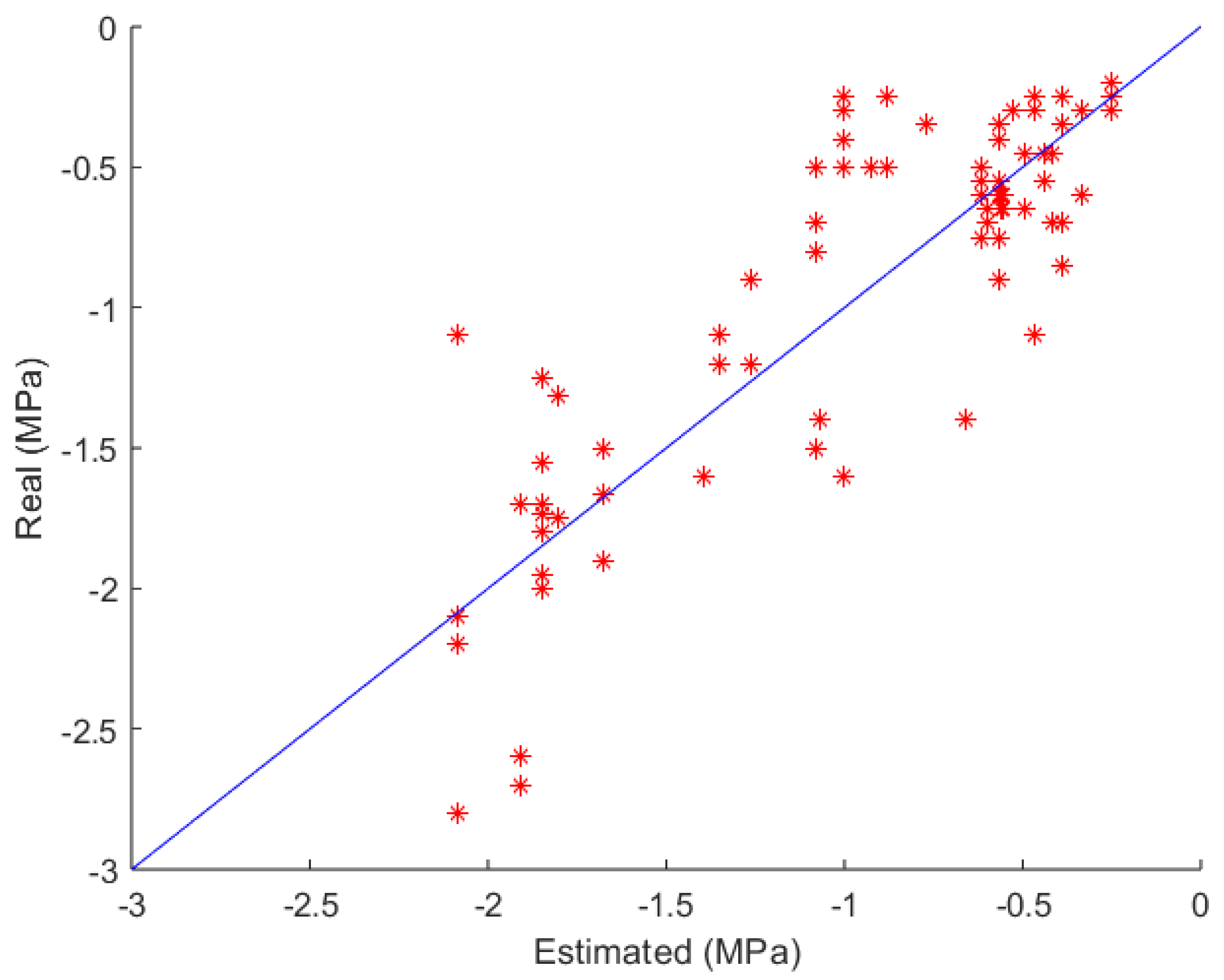

) of 0.6313 ± 0.0569, corresponding to the model with the 5 most relevant attributes considering the regression method. The decision tree model that performed better among the five folds presented a simple structure, consisting of 7 levels and a total of 30 nodes, being the root node, 9 internal nodes and 20 leaf nodes.

Figure 2 illustrates the predicted values in the best-performing fold for the decision tree model compared to the ideal line (blue line), with errors increasing as the estimated data points move farther from the line, the greater the errors associated with those data points. A noticeable dispersion of data around the ideal line is observed, with the largest errors occurring for water potential values higher than

. For this classifier, the achieved

RMSE was 0.3354 and the coefficient of determination (

) was 0.7259.

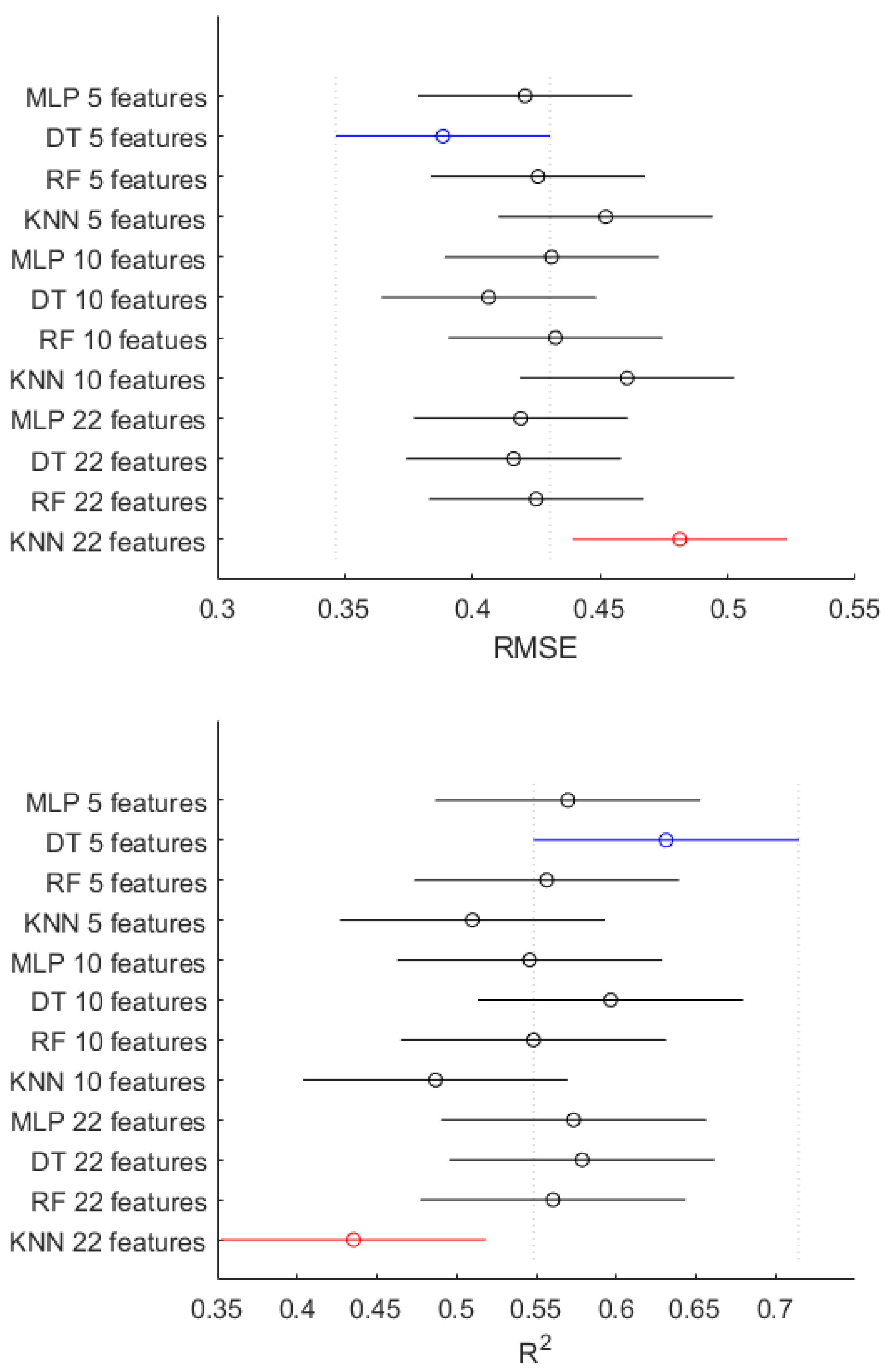

To compare the performance of the four machine learning models across the three feature sets (22, 10, and 5 features), a one-way ANOVA was applied to evaluate whether the mean prediction errors varied among the different configurations. When RMSE was used as the response metric, the ANOVA indicated a significant overall effect (

), demonstrating that at least one model–feature combination performed differently from the others. The subsequent Tukey HSD test identified a single statistically significant contrast: the decision tree with 5 features (DT 5 features) differed from the KNN with 22 features (KNN 22 features). As illustrated in

Figure 3, these two configurations represent opposite extremes in the distribution of RMSE values, while the remaining approaches show largely overlapping confidence intervals, indicating similar error magnitudes.

For the metric, the results revealed a consistent pattern. The ANOVA detected a significant global effect (), and the Tukey HSD test again found only one significant pairwise difference—between DT 5 features and KNN 22 features. The decision tree with 5 features achieved higher values, whereas the KNN with 22 features showed the lowest performance. The other model–feature combinations displayed similar predictive capacity, with no statistically distinguishable differences according to Tukey’s test.

3.1.2. Results for the Classification Models

For the classification procedure, the balanced accuracy metric was used, as it provides a more realistic assessment of the performance of Machine Learning models when dealing with imbalanced datasets. The results for irrigated condition are displayed in

Table 7 in terms of the number of features used as input for each model. The hyperparameters used for each model are presented in

Appendix B. These results comprise the mean (

) and standard deviation (

) values of the 5 folds (k-fold cross validation) used. It is observed that the KNN classifier applied to the five most relevant features achieved the best

values (67.73 ± 3.48). Among the five folds evaluated, the best performance was achieved for fold 5, with a balanced accuracy near to 73%. For this result, five neighbors and the Hamming distance were used to calculate the proximity between data points. The Inverse Function was applied for distance weighting, where the influence of neighbors on the classification of a new point is weighted inversely to its distance—closer neighbors have greater influence on the decision [

36]. The confusion matrix presented in

Table 8 refers to fold 5. It indicates some confusion between classes, but maintaining an accuracy above 70% for all classes, which leads to a global accuracy of 73.56%. The class imbalance in the training dataset (103, 167 and 80 samples for classes 1, 2, and 3, respectively) adversely impacted the model’s performance, as it hindered the model’s ability to effectively learn. This imbalance led to lower performance for Class 3, which had fewer training samples available.

Table 9 presents the per-class metrics for the irrigated condition for the results showed in

Table 8 (confusion matrix for the 5 most relevant features of fold 5, for the KNN classifier in the Irrigated condition). These results reveal heterogeneous performance across the three classes. Class 1 exhibits balanced behavior, with precision, recall, and F1-score all at 73.1%, indicating that the model identifies samples from this class consistently, without notable bias toward false positives or false negatives. Class 2 presents a slightly different pattern: while its recall (75.6%) is the highest among all classes—meaning the model successfully retrieves most of the samples belonging to this class—its precision is comparatively lower (70.5%). This discrepancy suggests a tendency toward false positives for Class 2, which ultimately reduces its F1-score (72.9%). Class 3 achieves the highest precision (82.4%), showing that predictions for this class are highly reliable when the model assigns that label. However, the recall for Class 3 drops to 70.0%, indicating that a non-negligible portion of true Class 3 samples are misclassified. Consequently, its F1-score (75.7%) reflects this imbalance.

3.2. Rainfed Condition

3.2.1. Results for the Regression Models

Similarly to the samples under irrigated conditions, the Machine Learning techniques were applied to the rainfed dataset, by considering the 5, 10 and 20 most relevant attributes as input features.

Table 10 displays the mean (

) and standard deviation (

) values of

RMSE and

. The MLP method presented the best results considering 20 attributes, with an

RMSE of 1.0569 ± 0.12462 and an

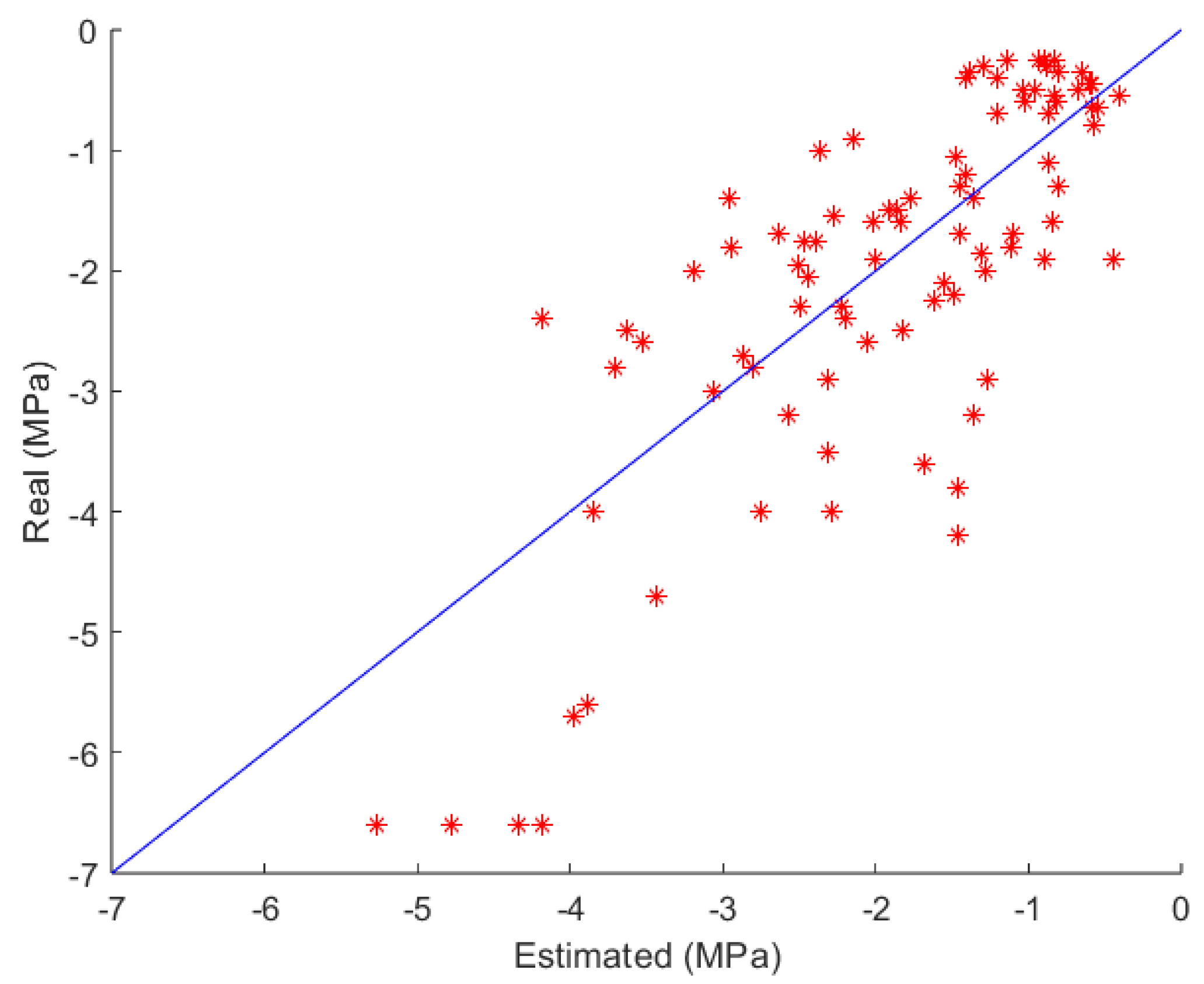

of 0.5441 ± 0.1099.

Figure 4 compares the actual and estimated data for the best fold and for the MLP model. Small errors can be observed for water potential values between

and 0, while other values show an underestimation. The parameters obtained after the iterations comprise a neural network with a single hidden layer, featuring 3 neurons and the Sigmoid activation function. For this model,

and

were found.

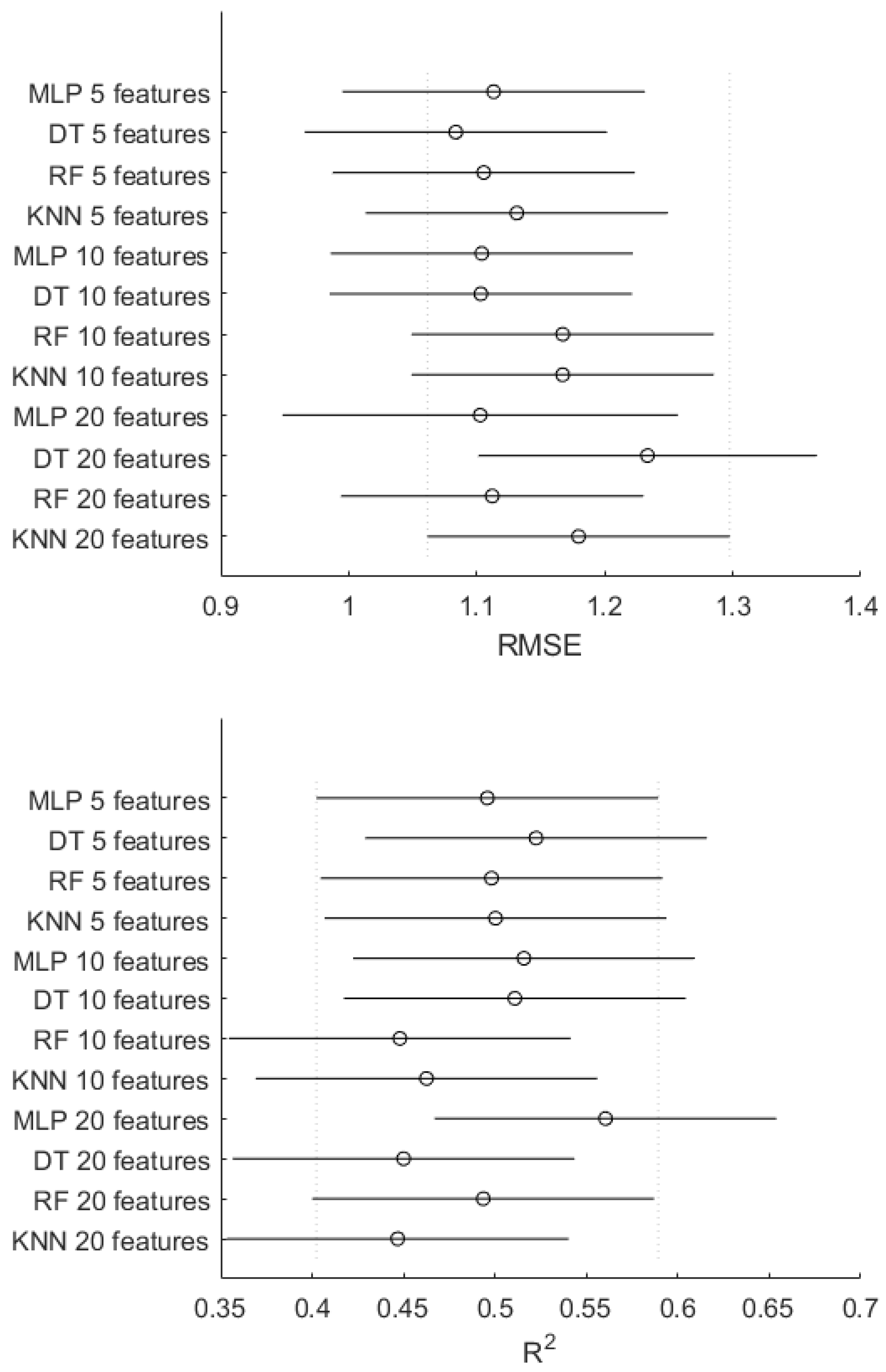

To assess the comparative performance of the machine learning models under rainfed conditions, a one-way ANOVA was applied to evaluate whether the mean prediction errors differed among the combinations of algorithms and feature sets (5, 10, and 20 features). For the

RMSE metric, the ANOVA did not detect a significant global effect (

), indicating that the evaluated configurations exhibit statistically indistinguishable prediction errors. Consistent with this outcome, the Tukey HSD test revealed no significant pairwise contrasts, as illustrated in

Figure 5, where the confidence intervals of the model–feature combinations show substantial overlap.

A similar pattern was observed for the

metric. The ANOVA again indicated the absence of significant differences across models and feature sets (

), and the Tukey HSD comparisons confirmed that none of the pairwise contrasts reached statistical significance. As shown in

Figure 5, the

values are tightly grouped, and the confidence intervals widely intersect, demonstrating that the predictive performance of the models is comparable under rainfed conditions.

3.2.2. Results for the Classification Models

For the classification procedure,

Table 11 displays the mean (

) and standard deviation (

) values of the balanced accuracies achieved by the implemented methods considering three different sets of the most relevant attributes for rainfed conditions. The hyperparameters used for each model are presented in

Appendix B. The balanced accuracy results did not exceed 47.55%, indicating a high level of confusion between classes and suggesting that the classifiers struggled to learn the patterns. Among the classifiers, the Random Forest exhibited the best results, achieving a balanced accuracy of

%, considering the 20 most relevant attributes as inputs. The Random Forest was parameterized with the Bag method, 38 iterations, minimum leaf size of 27, maximum number of splits of 4, and split criterion deviance.

Table 12 displays the confusion matrix for the best-performing fold in the case of Random Forest, where a global accuracy of 52.81% was found. The lowest accuracies were achieved for classes 1 and 4. Class 1 was frequently misclassified as class 2, while class 4 was primarily misclassified as classes 3 and 5. Acceptable classification accuracies were found for classes 2, 3 and 5. Converting class labels to water potential values according to

Table 2, values greater than −0.5 MPa, between −2.5 MPa and −3.5 MPa, and less than −3.5 MPa exhibit an imbalance when compared to the others. The class imbalance in the training dataset (53, 90, 112, 49, and 52 samples for classes 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively) adversely impacted the model’s performance, as it hindered the model’s ability to effectively learn. This imbalance led to lower performance for classes 1 and 4, which had fewer training samples available.

Table 13 presents the per-class metrics for the rainfed condition for the results showed in

Table 12 (confusion matrix for the 20 most relevant features of fold 2, for the Random Forest classifier in the Rainfed condition). These results reveal substantial variability in model performance across the five classes, indicating that the rainfed scenario poses greater classification challenges compared to the irrigated condition. Class 1 shows the largest imbalance between precision (66.7%) and recall (28.6%), resulting in a low F1-score of 40.0%. This pattern suggests that, although the model is relatively conservative and often correct when predicting Class 1, it fails to capture the majority of true Class 1 samples, leading to a high rate of false negatives. Class 2 demonstrates almost the opposite behavior: its precision is modest (41.9%), but recall reaches 59.1%, resulting in an F1-score of 49.1%. The model retrieves many actual Class 2 samples, yet the low precision indicates substantial confusion with other classes, reflecting a higher incidence of false positives. Class 3 exhibits the most balanced and robust performance, with precision and recall both at 64.3%, yielding the highest F1-score (64.3%). This result indicates that the model distinguishes this class more effectively than the others under rainfed conditions. For Class 4, the model achieves moderate precision (50.0%) but very low recall (23.1%), producing the lowest F1-score (31.6%). This again points to a tendency to miss a significant portion of true Class 4 samples, suggesting that the model has difficulty characterizing features associated with this class. Finally, Class 5 shows an interesting contrast: although its precision (50.0%) is only moderate, its recall is the highest among all classes (75.0%), leading to an F1-score of 60.0%. This indicates that the model successfully identifies most instances of Class 5, but at the cost of misclassifying samples from other classes as Class 5.

3.3. Discussion

In our study, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (

) was calculated to select the evaluated attributes most related to water potential. The results in

Table 4 indicate that reflectances near the 780 nm wavelength are the most significant, for irrigated conditions. This finding aligns with previous studies [

37,

38], which suggest that the spectral signature of vegetative targets, particularly hydrated green leaves, exhibits high reflectance in the Near-Infrared (NIR) range (700–1300 nm). In the infrared region (720 to 1100 nm) the interactions are related to the mesophyll structure and the variation in the amount of water [

32,

33]. However, for the rainfed condition, a prominence of wavelengths around 690 nm was observed (

Table 5), identifying them as critical bands for analysis. This finding aligns with existing literature [

37,

38], which reports that coffee plants grown under rainfed conditions tend to exhibit higher reflectance in this range, while healthy vegetation strongly absorbs light in this wavelength range due to chlorophyll. In the visible electromagnetic spectrum, wavelengths between 650 nm and 700 nm correspond to the red light region. This correlation supports the observed results, as the leaves of coffee plants under rainfed conditions often display a brownish or reddish hue. Then, classification and regression models were designed considering only the most relevant features, for each condition, irrigated and rainfed.

The machine learning methods used for estimating coffee leaf water potential differ in complexity, interpretability, and robustness. MLPs can model complex nonlinear relationships but require large datasets, careful tuning, and are less interpretable. Decision trees are simple and interpretable but prone to overfitting and may not capture subtle spectral patterns. Random forests improve accuracy and robustness by combining multiple trees, though they are less interpretable and computationally heavier. k-Nearest Neighbors is a simple, non-parametric approach but suffers in high-dimensional spectral spaces and with noisy data. Overall, each method presents trade-offs between predictive performance, interpretability, and computational cost, highlighting the need to select the approach based on data characteristics and study objectives. Importantly, the proposed models can be retrained efficiently when new cultivars or sensors are introduced, since they are based on standard machine learning algorithms with relatively low computational cost. In practice, retraining requires only the acquisition of new spectral and physiological data under the desired conditions, which can be processed using the same pipeline described in this study.

In summary, the proposed classifiers and estimators demonstrated superior performance when applied to irrigated coffee data. However, the non-uniform variation of values across the wavelength ranges posed challenges for the classifiers and estimators. Using more advanced oversampling or undersampling techniques, along with collecting additional data, could improve the results and should be explored in future work.

Decision tree and MLP techniques achieved the best performance for irrigated and rainfed data, respectively, when using the estimation method. However, performance may have been affected by the limited number of samples with water potential values below −2.5 MPa.

For the classification method, two distinct techniques demonstrated the best performance: Random Forest for rainfed data and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) for irrigated data. An imbalance in the data set was observed, which affected the results. This issue can be mitigated by employing oversampling algorithms along with collecting additional data, which are planned to be used in future studies.

Despite the significant relevance of leaf water potential and its association with spectral indices, there is a notable gap in the literature on studies aimed at estimating and classifying water potential in coffee plants without relying on complex direct measurements. This gap limits the availability of comparative benchmarks in the field.

Using global accuracy as the evaluation metric for the classification method, the results of this study were less favorable compared to those reported by our previous work [

6], which utilized spectral indices derived from wavelengths obtained through field-based spectral measurements. However, the importance of estimation via spectral signatures remains critical, as direct measurement of water potential involves labor-intensive and technically demanding procedures.

By providing detailed information on plant water status, the spectral signature-based methods explored in this study indicate a potential pathway toward the future development of intelligent, accessible, real-time sensing systems for coffee plantations. While no hardware prototype or cost evaluation was conducted, such systems could ultimately support more precise irrigation strategies and enhanced crop monitoring.

4. Conclusions

This study presented a novel approach for estimating and classifying the water potential of coffee plants using full-spectrum leaf reflectance data combined with machine learning techniques, avoiding reliance on spectral indices or labor-intensive direct measurements. By implementing four methods—Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Decision Tree, Random Forest, and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)—and applying both regression and classification strategies, we demonstrated that different algorithms perform optimally under distinct crop management conditions. Specifically, Decision Tree and MLP models achieved the highest accuracy for irrigated and rainfed plants, respectively, while Random Forest and KNN were superior for classification tasks.

Future work should focus on addressing data limitations, such as imbalanced water potential ranges and non-uniform spectral variation, through the collection of additional measurements and the application of advanced oversampling or undersampling techniques. Moreover, exploring hyperspectral datasets and more sophisticated machine learning architectures may further enhance predictive accuracy and generalizability across different cultivars, environmental conditions, and management systems.

Regarding the instrumentation, the spectrometer used in this study costs on the order of USD 20,000. One of our ongoing objectives is to adapt the proposed methodology to low-cost sensing systems that can reproduce the same analytical principles while achieving a substancial cost reduction (approximately 80%). Future developments will focus on implementing simplified optical sensors or miniaturized spectrometers to enable wider application in both research and field contexts.