Abstract

In the face of escalating energy demand, this research proposes a demand-side management (DSM) strategy that focuses on appliance-level load shifting in residential environments. The proposed approach utilizes detailed energy consumption forecasts that are generated by ensemble machine learning models, which predict usage at both whole-household and individual appliance levels. This granular forecasting enables the development of customized load-shifting schedules for controllable devices. These schedules are optimized using a metaheuristic genetic algorithm (GA) with the objectives of minimizing consumer energy costs and reducing peak demand. The iterative nature of GA allows for continuous fine-tuning, thereby adapting to dynamic energy market conditions. The implemented DSM technique yields significant results, successfully reducing the daily energy consumption cost for shiftable appliances. Overall, the proposed system decreases the per-day consumer electricity cost from 237 cents (without DSM) to 208 cents (with DSM), achieving a 12.23% cost saving. Furthermore, it effectively mitigates peak demand, reducing it from 3.4 kW to 1.2 kW, which represents a substantial 64.7% reduction. These promising outcomes demonstrate the potential for substantial consumer savings while concurrently enhancing the overall efficiency and reliability of the power grid.

1. Introduction

The term “Smart Grid” (SG) [1,2] refers to the efficient transmission and distribution of electricity, which is achieved via the integration of control and communication technology inside a conventional grid. The goal is to reduce global warming by lowering carbon emissions and to lower electricity costs by managing loads more efficiently. Regarding energy management, demand-side management (DSM) [3] is a key aspect of the smart grid. DSM’s purpose is to enhance the economics of the power system by the optimal use of existing grid energy. In the given context, controlling the load pattern can minimize peak load demand, improving grid efficiency, lowering carbon emissions, and lowering the user’s electricity price [4]. DSM modifies customer energy consumption patterns through various techniques and programs, including financial incentives and behavioral modification via education.

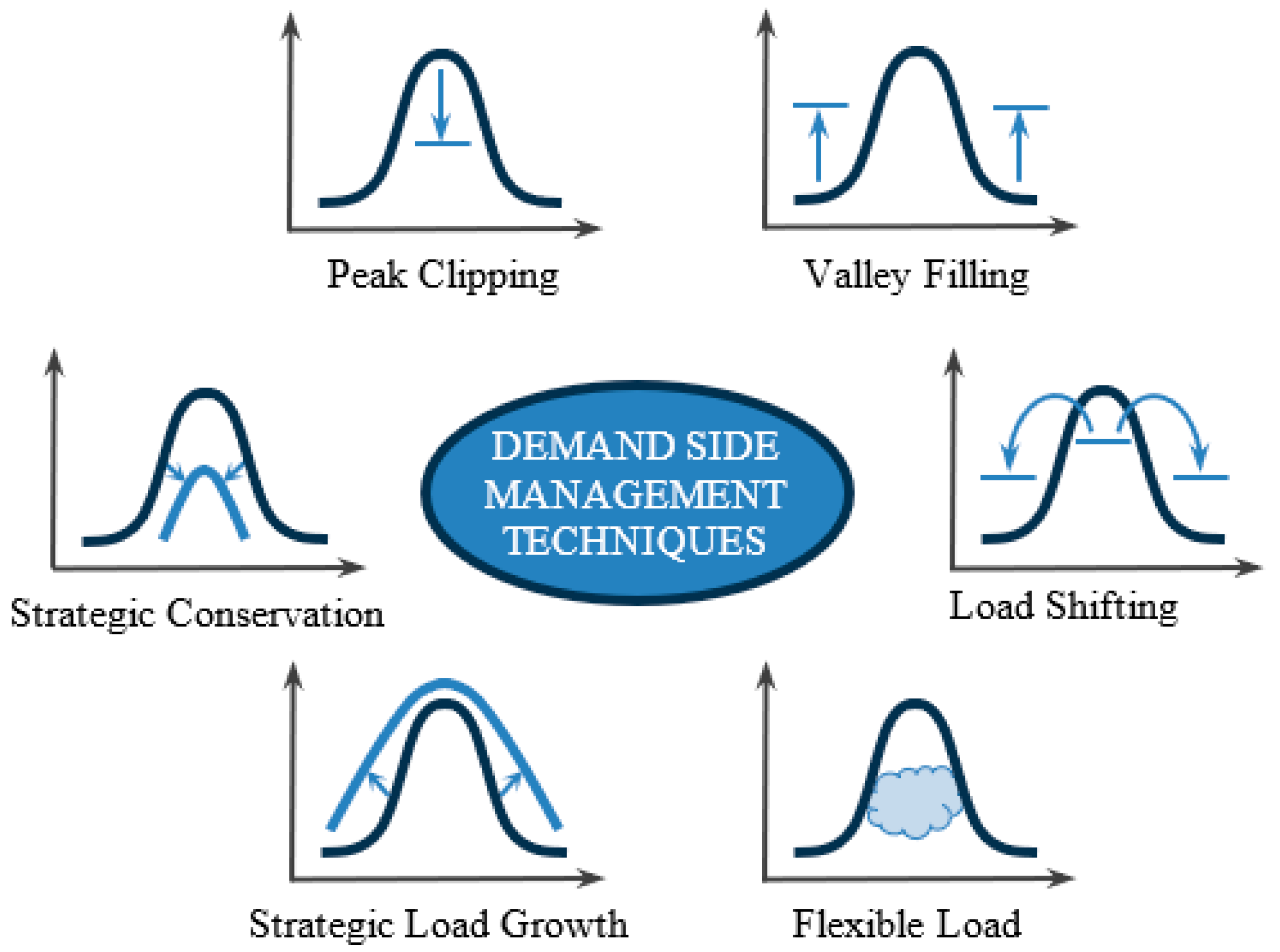

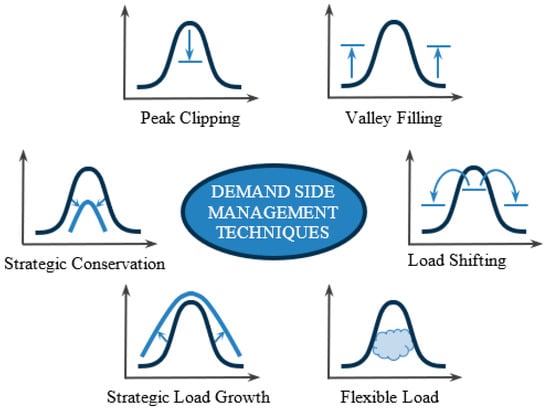

DSM modifies customer demand patterns to accomplish the desired change in the load shape of the power network. DSM techniques adjust load patterns by moving the demands made by shiftable appliances during peak hours and relocating these loads to a more cost-effective time. Within DSM, the load pattern that indicates power consumption can be altered in six ways [5]: peak clipping, valley filling, load shifting, flexible load shape, strategic conservation, and strategic load growth. A graphical representation of all six techniques is depicted in Figure 1. The peak clipping [6,7] technique is a direct load control technique that aims to reduce the peak of a customer’s load profile at designated times. As a result, both the peak demand and overall energy consumption are reduced. Valley filling [8] is a form of load management technique that increases or builds off-peak loads. This technique is preferable if a utility has excess capacity during off-peak hours. The net effect of this technique results in an increment in total energy demand but no change in peak demand. Load shifting is the most effective and widely used load management technique. It essentially moves electricity consumption from one time period to another by shifting the load from peak time to off-peak time. The net effect is a decrease in peak demand but with no change in total energy demand. The strategic conservation [7] technique involves reducing overall energy consumption by encouraging consumers to use energy-efficient appliances and devices. The net effect is a reduction in both peak demand and the total energy demand. Strategic load growth [6] tends to increase the market share of loads supported by energy conservation and storage systems or distributed energy resources. Peak demand and overall energy usage both rise as a result. Typically, it is executed by either raising energy intensity or bringing on board additional clients. For example, an area with four power plants can generate 400 MW, but the peak demand at any time of the day goes up to 300 MW, with 100 MW remaining idle for the entire year. Now, the task at hand involves the establishment of a customer base or the provision of incentives to encourage companies to purchase or utilize energy from the available sources. Flexible load shapes improve smart grid reliability by finding customers with flexible loads who are prepared for that to be managed during critical periods in exchange for a variety of incentives [6,7]. Thus, the government needs to identify such consumers, namely, those who can work at any time period of the day. When the government asks them to operate during peak periods, they should be ready to do so. If the government asks them to stop their production, they should be able to stop production. And, if the government asks them again to start production during the off-peak period, they should be ready to start production during off-peak hours. These flexible consumers need to be identified in a region by providing some incentives for them to flexibly change their operating schedules. The overall results may be a reduction in peak demand and a change in total energy usage.

Figure 1.

Different demand-side management techniques [9].

In the context of DSM, a dynamic pricing scheme, i.e., an electricity tariff, plays a key role. Smart meters and intelligent metering equipment (as found in SGs) make it simple to manage loads according to dynamic pricing schemes. Real-time pricing (RTP), time of use (TOU), critical peak pricing (CPP), and direct load control (DLC) are some of the demand responses (DRs) that dynamic pricing schemes often utilize in DSM programs. When these demand response-based dynamic pricing methods are implemented in conjunction with DSM strategies, penalties, and incentives, they impact client energy usage control. A comprehensive overview of demand response programs is presented by Han and Piette in [10] and can be classified into two main types: time-based DRs and incentive-based DRs. Participants in incentive-based programs can receive incentives in exchange for agreeing to reduce energy usage during periods of peak demand. Time-based programs provide clients with time-varying electricity pricing, encouraging them to shift their respective loads to low-priced hours [11]. The two types of DR can be further classified into various categories, such as time-of-use rates, real time pricing, critical peak pricing and direct load control, and emergency DR programs, respectively [12].

Recent developments in artificial intelligence, optimization techniques, and computational resources have empowered researchers to conduct research with greater ease and accuracy. The optimization problems reported in the literature are being addressed through classical techniques along with mathematical optimization, meta-heuristic techniques, and hybrid-heuristic techniques [13]. Classical techniques include linear programming (LP) [14], non-linear programming (NLP) [15], convex programming (CP), and dynamic programming (DP) [16]. Meta-heuristic techniques are more popular and more efficient optimization techniques than conventional techniques, due to the large search space needed to find optimal solutions [17]. Meta-heuristics include genetic algorithms (GAs) [18], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [19], ant colony optimization (ACO) [20], and wind-driven optimization (WDO) [21], among others. The hybrid-heuristic technique is the combination of two or more algorithms [22]. Table 1 provides a comparative analysis of traditional, meta-heuristic, and hybrid-heuristic techniques.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of optimization techniques.

Numerous research works have proposed many DSM strategies, with the key objective of reducing the load peak and energy consumption cost. In Ref. [23], an evolutionary algorithm was utilized to schedule various numbers of appliances, by which means the user load curve is moved closer to the predefined objective curve, which is inverse to the electricity price signal. Furthermore, the article addresses a variety of loads, including residential, commercial, and industrial loads. The reported results suggest that the evolutionary algorithm method is more efficient than mathematical approaches for dealing with a large number of loads. In Ref. [24], the authors suggested an integer linear programming (ILP)-based appliance scheduling strategy that shifts loads from on-peak to off-peak to reduce power consumption expense and peak load. To reduce peak demand and electricity costs, the authors of [25] employed a GA to schedule home load optimally. They implemented a pricing scheme that used real-time pricing (RTP) and notified the user one day in advance. PSO was also implemented for DSM optimization by the authors of [26] to minimize customer electricity expenses. The ACO-based scheduling technique was developed by Okonta et al. [27]; the time of unit (TOU) pricing plan, consumer comfort, and electricity costs were the main focuses of the study. A GA-based load scheduling technique was proposed for residential, commercial, and industrial areas in [18] to optimize the cost and peak demand issues associated with energy consumption. Rahim et al. [28] presented a load scheduling technique used to lower peak load, electricity costs, and the peak-to-average ratio (PAR). Game-theoretic and evolutionary approaches have been widely explored to analyze strategic interactions and long-run behavior in decentralized power markets [29]; that study adopts a data-driven scheduling perspective to evaluate residential load shifting under real-time pricing using the Pecan Street dataset. In Ref. [30], forecasting of renewable energy, such as solar power, using LSTM has been shown to improve prediction accuracy. Hybrid machine learning approaches combining LSTM and reinforcement learning have been shown to optimize home energy management [31]. In Ref. [32], decentralized federated LSTM models were used to predict energy demand in smart homes while preserving data privacy, enabling optimized energy distribution and improved energy efficiency. Moreover, ConvLSTM and BiConvLSTM models have been shown to accurately forecast energy demand in electric vehicle charging station networks, supporting more efficient energy management [33].

In the existing literature, numerous studies have proposed using DSM strategies; however, most of these studies have primarily focused on aggregated load data. Consequently, the existing literature is limited in terms of providing an in-depth analysis of load-shifting techniques for segregated loads, i.e., individual appliances. To reap the benefits of DSM techniques in practical energy efficiency applications such as recommender systems, it is necessary to formulate and evaluate individual appliance-level load shifting strategies. Therefore, to address the identified shortcomings and realize the practical potential of individual load shifting, this study concentrates on utilizing the results of segregated load forecasting to achieve the implementation of load-shifting techniques for diverse shiftable loads. The objective of this study is to minimize energy consumption costs and reduce the peaks associated with energy consumption, thereby providing a more comprehensive and targeted approach to DSM. The key contribution of this research work is summarized as follows:

- •

- Employing segregated forecasted load data in addition to aggregated forecasted load data, which are traditionally used for load shifting applications, and a load shifting strategy is proposed for diverse individual loads, which is equally applicable for aggregated load.

- •

- Digital simulations are carried out using real-world load measurements acquired from the Pecan Street—Data port.

- •

- Comprehensive performance evaluation is carried out for an in-depth analysis of the load-shifting strategies at segregated as well as aggregated levels.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: the detailed research methodology of load shifting, along with problem formulation, is presented in Section 2, Section 3 and Section 4. Section 5 presents details of the digital simulations, the extracted results, and a corresponding analysis. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Research Methodology

To solve the optimization problem at hand, this research work formulates a research methodology, which is detailed in the following subsections.

2.1. Forecasted Load Data Acquisition and Its Utilization in Demand-Side Management

This section of the paper focuses on the most crucial aspect of DSM, emphasizing the importance of harnessing forecasted data for effective implementation. For this purpose, actual load forecasting results that have been extracted are utilized for demand-side management problems.

Accurate load forecasting is important to take maximum advantage of the DSM technique, i.e., load shifting. The forecasting results utilized in this study were extracted from ensemble machine learning models that demonstrated superior performance in a previous study [34]. The forecasted data derived from these models form the basis for the DSM strategies used herein. By utilizing these forecasting results, the aim is to identify the objective curve that guides decision-making under specific conditions. Data from hourly forecasted loads obtained from ensemble learners are utilized for the DSM technique. The proposed algorithm is designed for one-day-ahead load shifting, i.e., a 24-h window size from 8 a.m. to 8 a.m. This 8 a.m. to 8 a.m. window size was carefully chosen for load-shifting applications to improve consumer comfort and flexibility in managing their appliance usage. By starting at 8 a.m., users have the flexibility to adjust their appliance usage well before or well after potential peak hours. The 8 a.m. to 8 a.m. window size, therefore, aims to strike a balance between accommodating user preferences and maximizing the opportunities for effective load shifting. Table 2 shows the hourly forecasted load data with real-time pricing [23] for a 24-h window size.

Table 2.

Hourly forecasted load with real-time pricing.

2.2. Shiftable and Non-Shiftable Appliances

After load forecasting, the next step in implementing DSM techniques, specifically load shifting, involves the task of categorizing appliances into shiftable and non-shiftable types. In load shifting, the pivotal strategy involves shifting consumer load from peak hours to off-peak hours. This requires categorizing appliances into two groups: shiftable appliances and non-shiftable appliances. Shiftable appliances are the ones that can be shifted from one time to another if the service provider (SP) deems it necessary. Such appliances provide a dynamic response to load shifting and offer the flexibility required to redistribute the energy usage in peak periods to reduce the grid stress, allowing for the more efficient utilization of resources and contributing to overall grid stability. In contrast, non-shiftable appliances are the ones that do not offer flexibility for load shifting. They are essential for the everyday operations of a household and must remain operational until the specific need of the consumer is fulfilled. Such appliances are not considered to be flexible in terms of load-shifting tactics, and their uninterruptible functioning is dictated by the household’s immediate demands and routine [35].

Table 3 enumerates the list of appliances categorized as shiftable and non-shiftable for the purposes of this study [23,35]. This categorization serves as a foundational framework for implementing load-shifting practices effectively, optimizing energy consumption, and promoting a more sustainable and resilient power infrastructure.

Table 3.

Shiftable and non-shiftable appliances’ definition.

3. Why Is a Genetic Algorithm Employed in This Study?

Of the above-mentioned techniques listed in Table 1, meta-heuristic techniques are more commonly used and more effective optimization techniques than conventional techniques, due to the large search space needed to find the optimal solution, and they are less complex and easy to implement than hybrid-heuristic techniques [36]. Meta-heuristics includes many techniques like the GA, PSO, and ACO. A comparative analysis is provided in Table 4.

Given its widespread usage, and based on the comparative analysis presented, a GA is employed for the current DSM problem. Therefore, this section provides a detailed methodology of DSM using optimization techniques, i.e., a genetic algorithm (GA). A GA can address complex optimization problems like DSM, and it uses a parallel search mechanism across a population of potential solutions. This search mechanism enables it to avoid getting trapped in local optimal solutions and allows for a complete exploration of the solution space [37]. As a result, the use of GAs aligns with the complex nature of DSM, providing a robust and proper approach to such optimization problems.

In the proposed framework, an optimization algorithm is integrated with the specific purpose of bringing the final load curve as close to the predefined objective load curve as possible, and this alignment serves as the foundation for achieving the primary goal of the DSM strategy, which is the reduction of utility bills and peak load. In pursuit of this goal, an objective load curve is formulated and is chosen so that it is inversely proportional to electricity market prices.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of meta-heuristics techniques.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of meta-heuristics techniques.

| Algorithm | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| GA | Highly amenable to parallelization, mitigates local optima through effective mutation, and keeps a balance between exploration and exploitation | Premature convergence, limited scalability, and difficulty with multimodal problems |

| PSO | Easy to implement, fast convergence, versatility, and robustness | Less parallelizable, with parameter selection challenges due to poor exploration, and does not retain information about past searches, due to a lack of memory |

| ACO | Capable of efficient clustering and route construction, with a memory of past solutions, and robustness to parameter settings | Less naturally parallelizable, compared to the GA and PSO, and time-intensive, with a comparatively low convergence speed |

4. Problem Formulation and the Proposed Algorithm

The proposed DSM strategy introduced in this study schedules the connection time of each shiftable device of the household, and its schedules are such that the load consumption curve should come close to the predefined objective load consumption curve. The mathematical formulation of the proposed load-shifting technique is given in Equation (1).

In Equation (5), (t) is the actual load consumption that has been forecasted, while is the value of a predefined objective load curve. The objective load curve is selected to be inversely proportional to the electricity pricing because the goal is to reduce the utility bill. Consequently, each step’s objective curve is specified as in Equation (2).

The price (t) denotes the price per kWh of electricity at each time step, while the objective curve defined in Equation (2) reflects the way in which the electricity bill is balanced every hour. In instances of high prices, energy consumption tends to be lower, and vice versa. The aim is to minimize the difference between the forecasted energy consumption curve and the defined objective curve, as given in Equation (1).

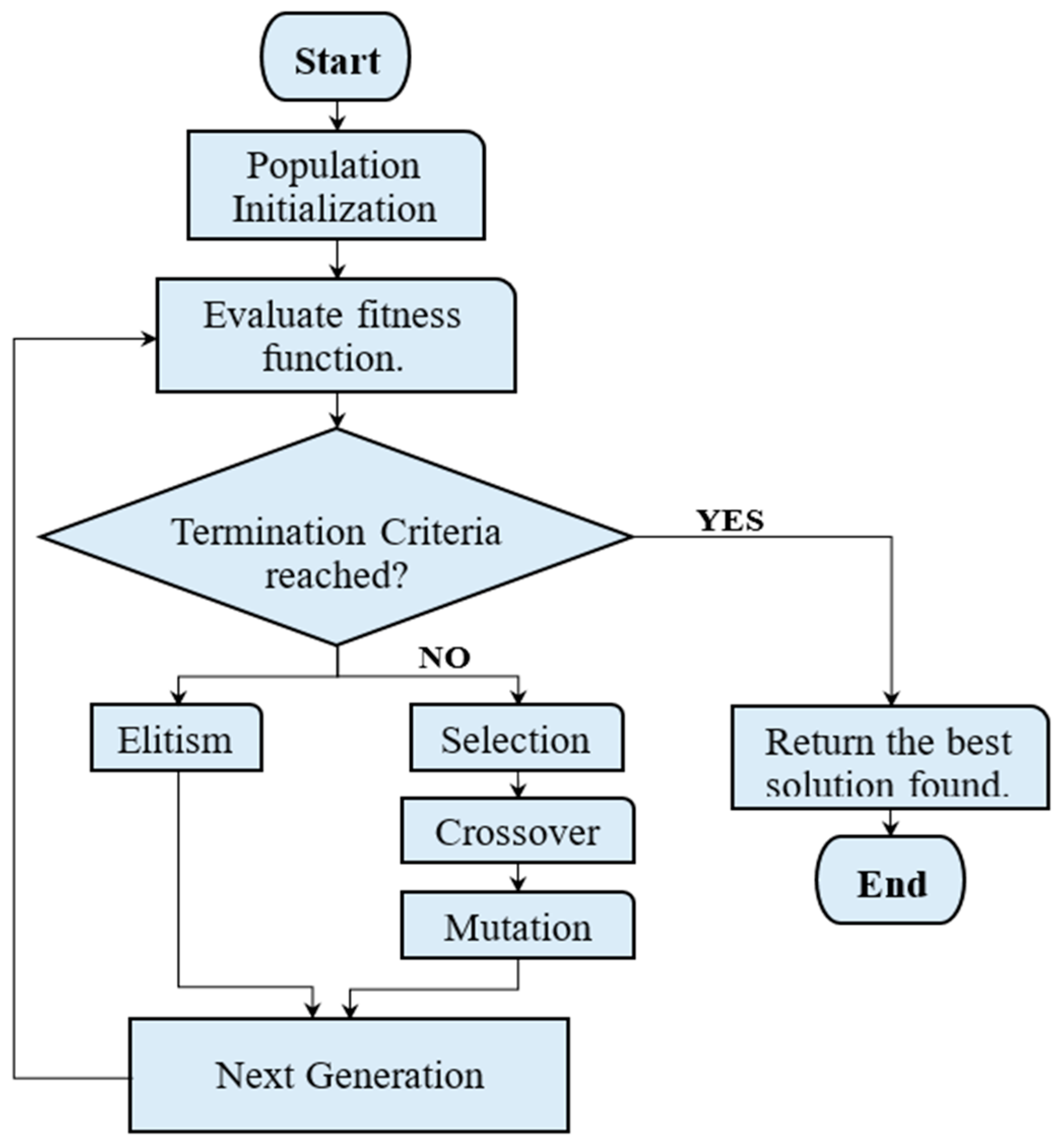

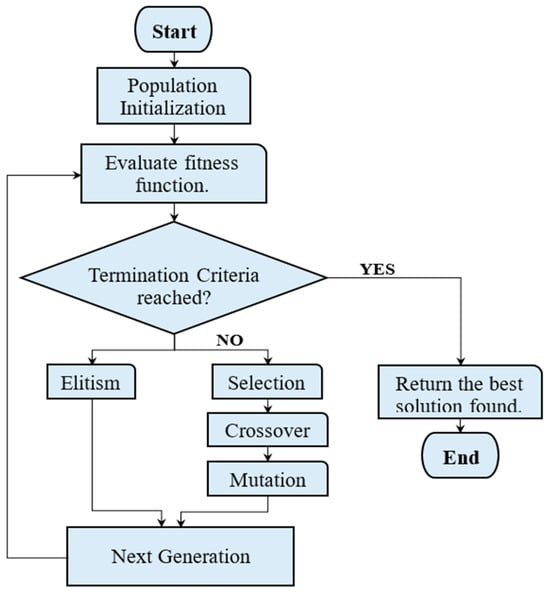

After defining the objective function, the next step is to employ the GA to solve the load scheduling problem. The GA generates solutions to optimization problems inspired by natural evolution, utilizing processes such as selection, crossover, and mutation. The procedure starts with a randomly initialized population chosen by the GA, which contains sets of solutions also called chromosomes. The fitness of each chromosome/individual is evaluated using the fitness function, and then the fittest individuals are selected. After selection, these individuals undergo an alteration process through crossover and mutation operators, resulting in a newly generated population, which is then employed in the subsequent evaluation process. This process of altering and generating a new population continues until the maximum number of generations is reached. The best chromosomes are considered to be optimal solutions based on their fitness, signified as those closest to the predefined objective curve. The overall flow of the employed genetic algorithm is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow of the employed genetic algorithm for demand-side management.

The fitness function formulated in this problem is presented in Equation (3):

where x(t) indicates the solutions generated by the GA, and is the pre-defined objective curve. Upon reaching the maximum number of generations, the algorithm identifies the optimal solution x(t) based on its fitness value. A higher fitness value is associated with a solution that either closely aligns or best converges with the pre-defined objective curve.

The suggested DSM model is formulated as a day-ahead scheduling problem; however, the optimization framework can be regularly re-executed across a rolling horizon as new demand forecasts and electricity price signals become available. This periodic re-optimization aligns the proposed approach with over-time and online combinatorial optimization paradigms, as discussed by Duque et al. in [38], where sustained system performance is achieved by repeatedly revisiting scheduling decisions in dynamic environments.

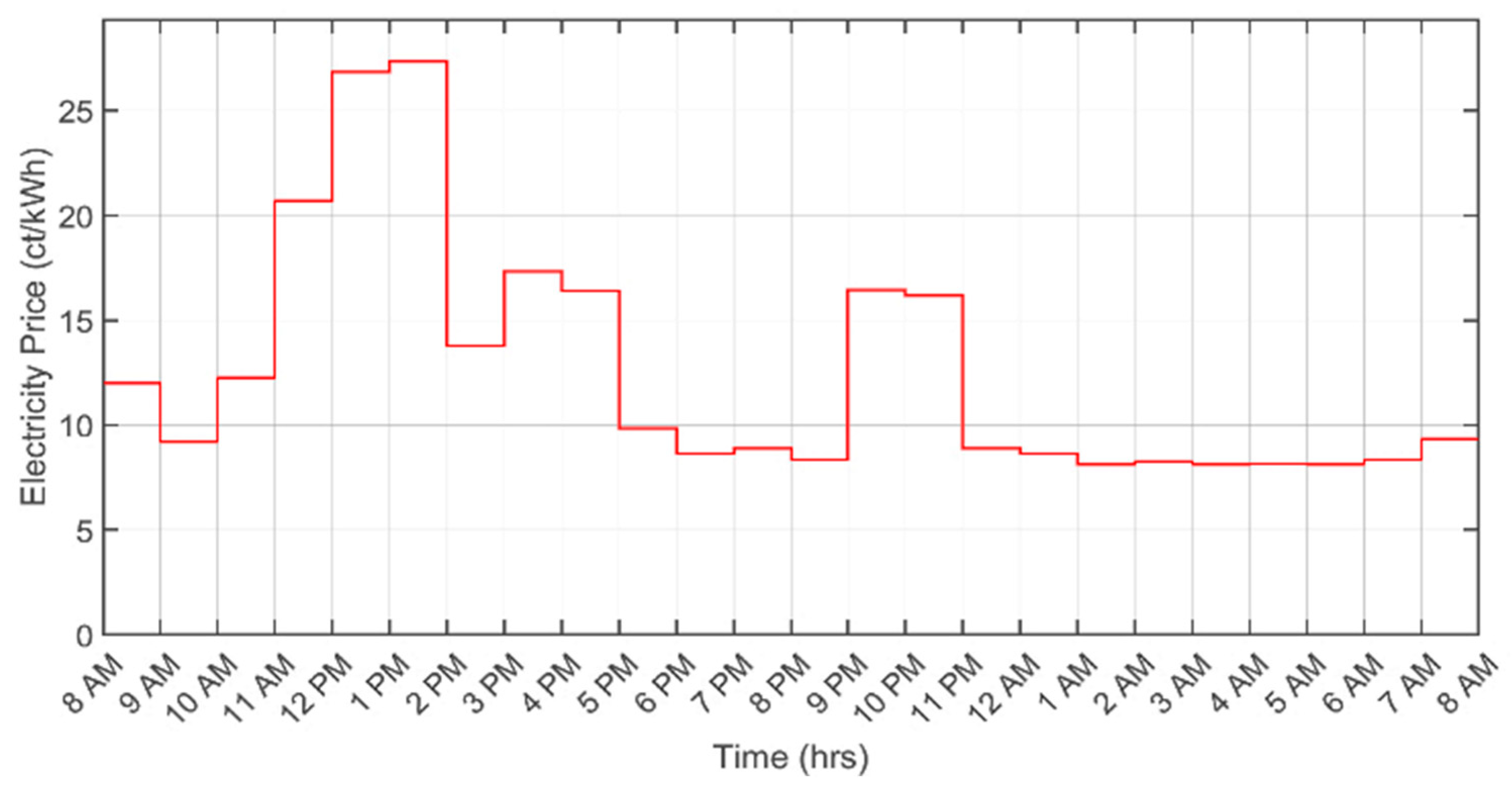

5. Simulation and Results

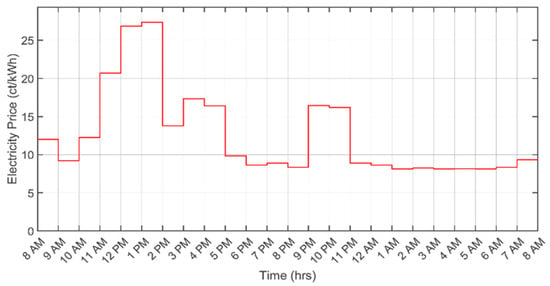

For simulation purposes, MATLAB 2019a was used. The simulations were carried out using a Notebook with a Core i7 5th Gen CPU (2.6 GHz clock) and 8 GB RAM. To optimize the performance of the GA, the GA parameters were also optimized. The parameters included population size, the number of generations, crossover rates, and mutation rates. This exploration was carried out through experimentation [39], systematically evaluating each combination to identify the parameters that yielded the best results. The selected parameters are referred to herein as the best or optimized parameters. Brief details of the different hyperparameters of the employed GA are presented in Table 5. The RTP signal (based on data presented in Table 2, as used in the DSM) is shown in Figure 3.

Table 5.

The employed parameters for the genetic algorithm.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the real-time pricing signal.

5.1. Segregated Loads DSM

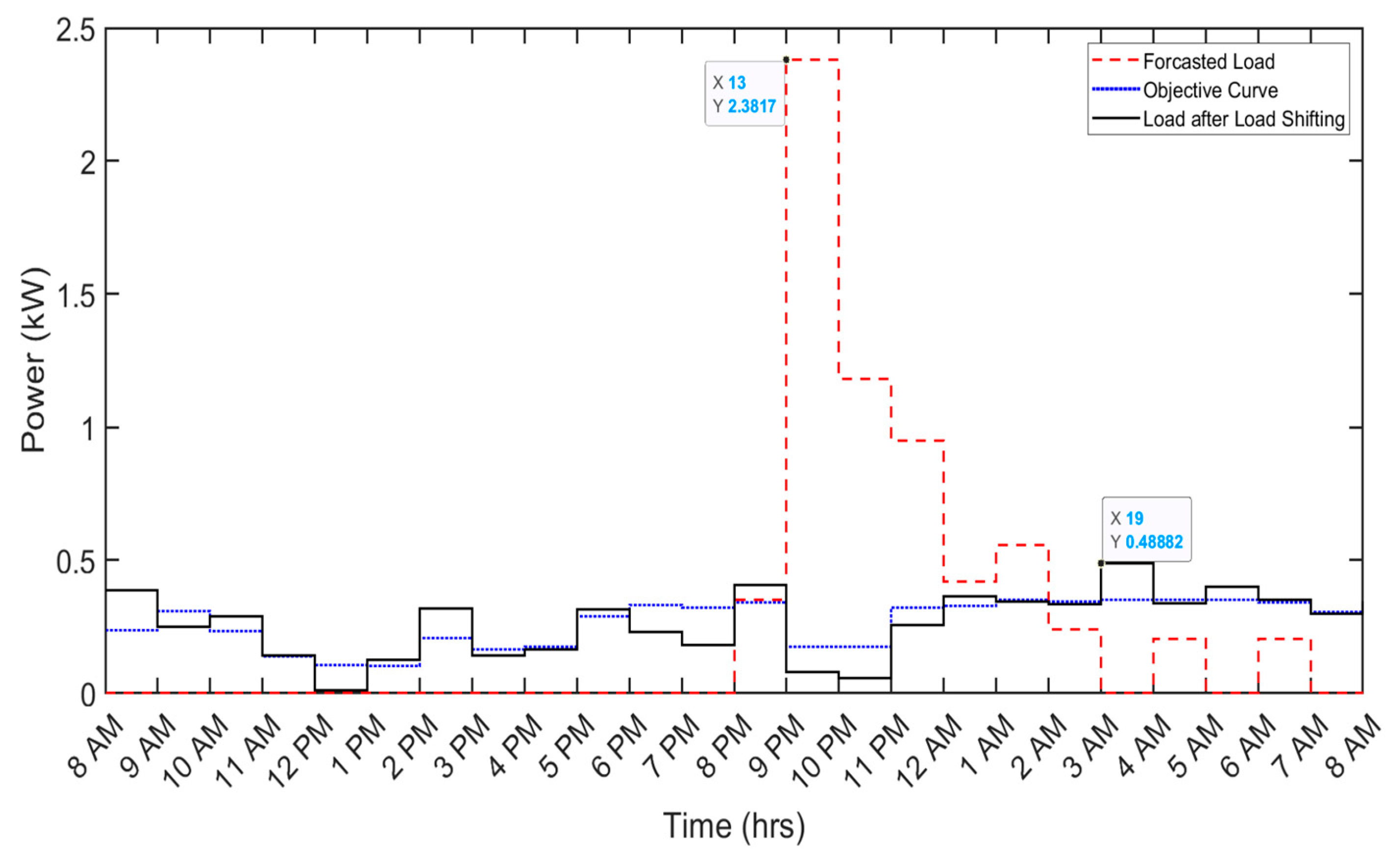

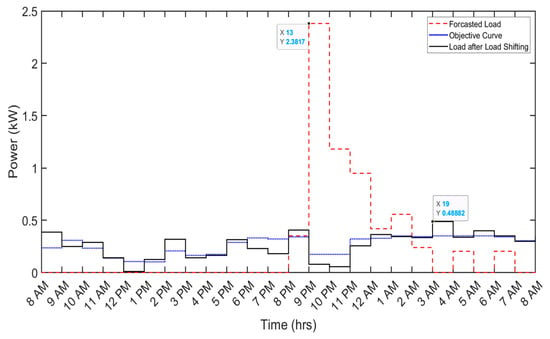

The simulation results depict the impact of implementing DSM on various shiftable appliances, such as air conditioners (ACs), clothes washers, kitchen appliances, and miscellaneous loads, within a household. The scheduling of shiftable appliances, such as the AC, demonstrates a noteworthy reduction in the daily electricity bill from 83.1 cents to 65.7 cents, constituting a 20.9% decrease. Concurrently, the peak demand experiences a substantial reduction from 2.382 kW to 0.4888 kW, indicating a notable 79.3% decrease in peak load.

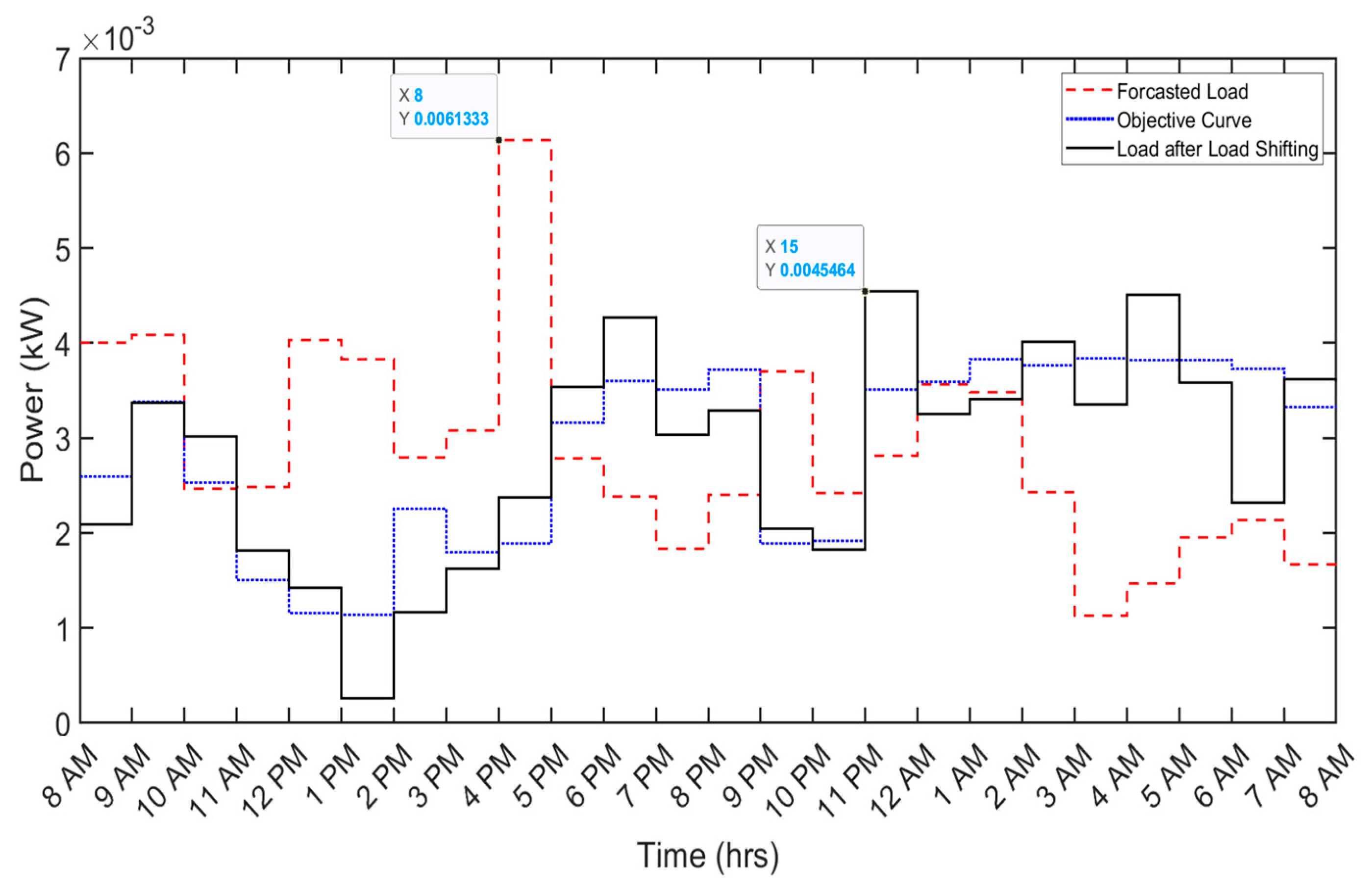

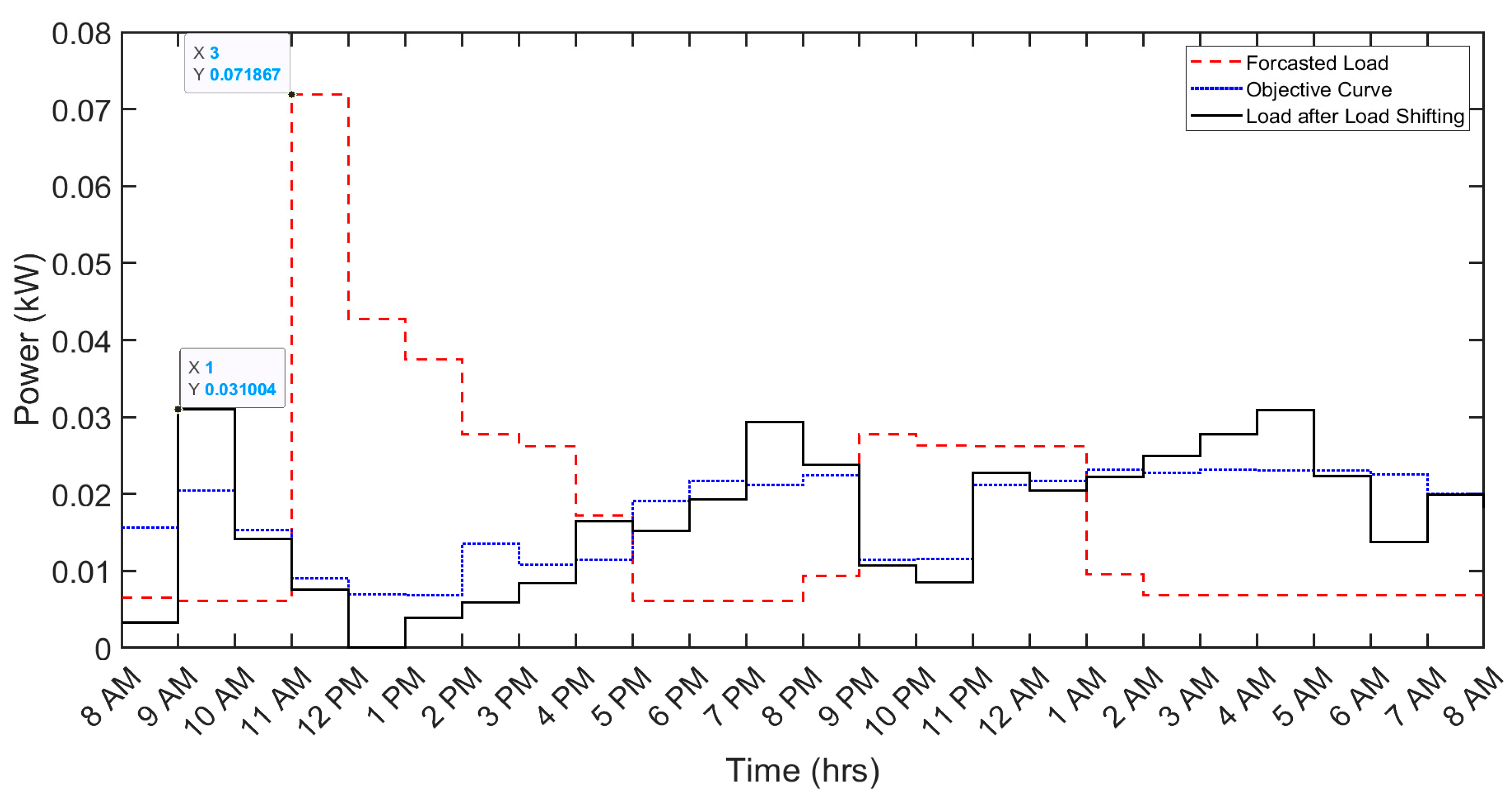

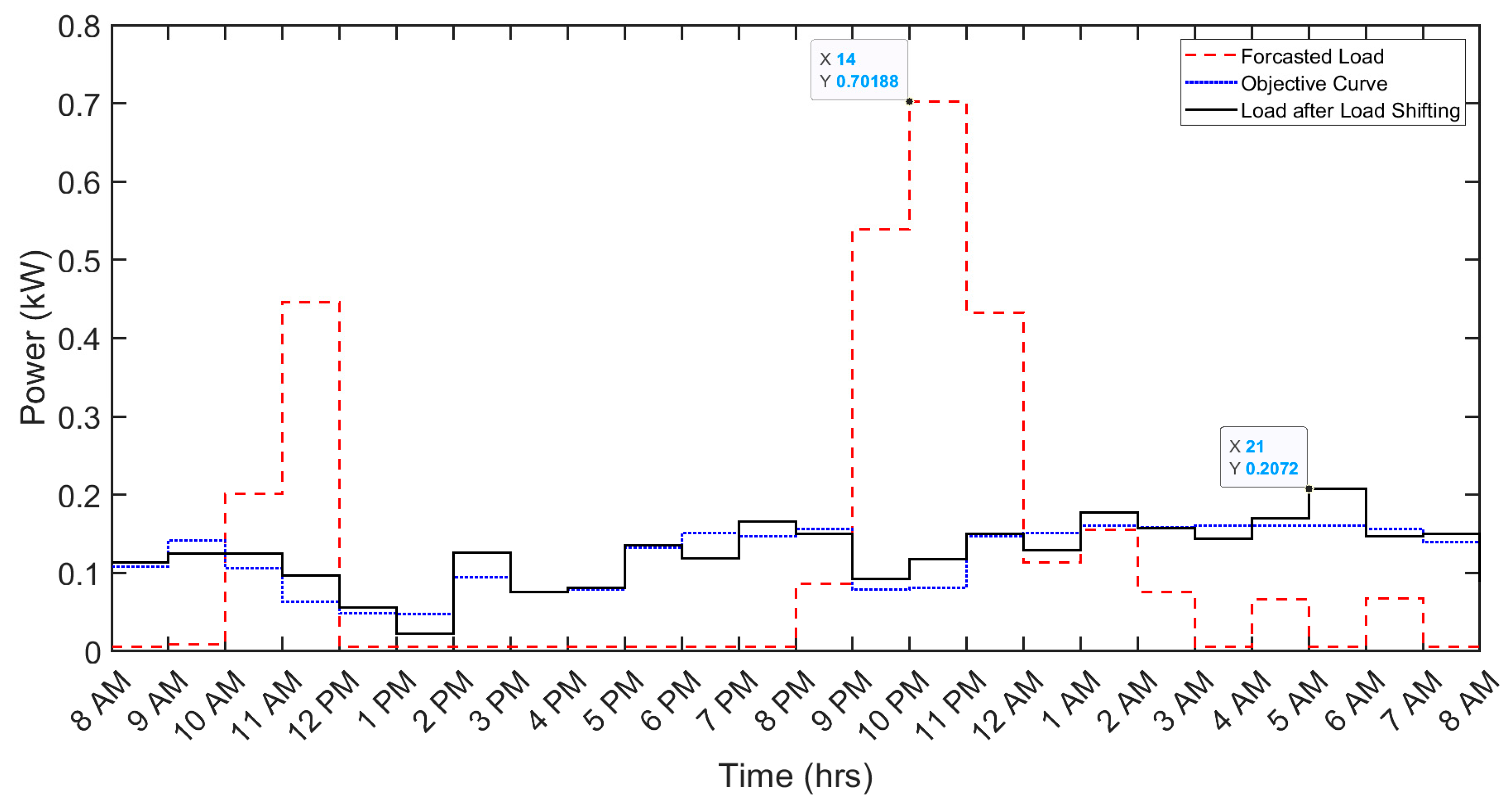

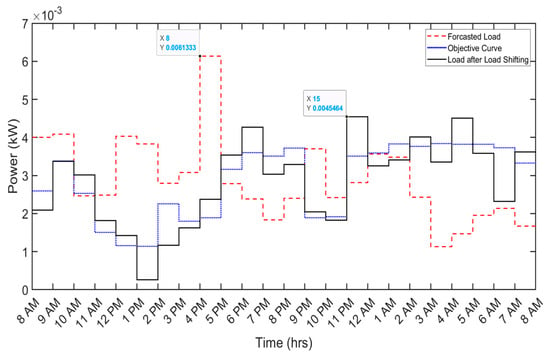

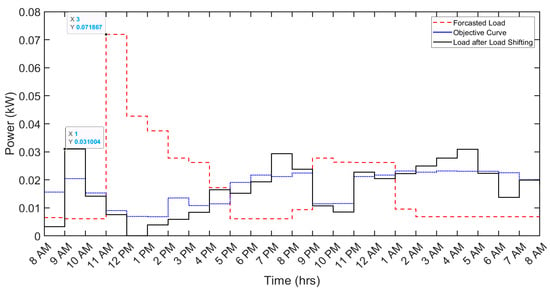

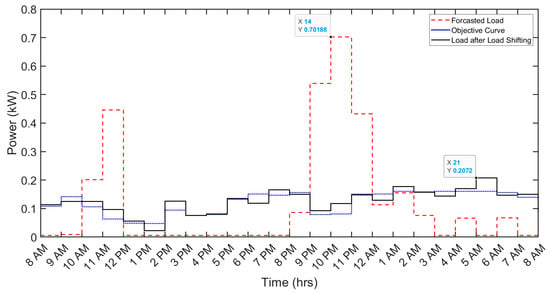

Similarly, the clothes washer exhibits a reduction in daily cost from 0.9 cents to 0.7 cents, reflecting a 22.2% decrease. The associated peak reduction is observed to be from 0.0061 kW to 0.0045 kW, accounting for a 26.23% decrease. Likewise, other loads, such as kitchen appliances and miscellaneous loads, contribute to a reduction in the daily electricity bill from 7 cents to 4.1 cents (42% reduction) and 41.5 cents to 33.1 cents (19.5% reduction), respectively. Correspondingly, the peak demand for both these loads undergoes a substantial reduction from 0.072 kW to 0.031 kW (56.9% reduction) and 0.702 kW to 0.207 kW (70.5% reduction), respectively. Table 6 and Table 7 provide a detailed comparison of per-day cost and peak demand before and after the implementation of DSM techniques, respectively. The impact of the implemented DSM techniques on various shiftable appliances (AC, clothes washer, kitchen appliances, and miscellaneous loads) is visually depicted in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 4.

Demand-side management results for the air conditioner.

Figure 5.

Demand-side management results for the clothes washer.

Figure 6.

Demand-side management results for the kitchen appliances.

Figure 7.

Demand-side management results for miscellaneous loads.

The overall cost of electrical energy consumption for each hour by a specific appliance is computed by multiplying the total energy consumption during that hour by the corresponding electricity price for that period, as outlined below in Equation (4):

where pi is the electricity consumption price in hour i, and Ei is the energy consumed by an appliance at hour i. Costi is the energy consumption cost in an hour i. Therefore, the per-day energy consumption cost will be the sum of the cost of each hour, as given in Equation (5).

Table 6.

Impact of demand-side management on energy consumption cost for segregated loads.

Table 6.

Impact of demand-side management on energy consumption cost for segregated loads.

| Loads | Cost Before DSM (Cents) | Cost After DSM (Cents) | Cost Reduction (Cents) | Percentage Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Conditioner | 83.1 | 65.7 | 17.4 | 20.9 |

| Clothes Washer | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 22.2 |

| Kitchen Appliances | 7.0 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 41.4 |

| Miscellaneous Loads | 41.5 | 33.1 | 8.4 | 20.2 |

Table 7.

Impact of demand-side management on peak demand for segregated loads.

Table 7.

Impact of demand-side management on peak demand for segregated loads.

| Loads | Peak Load Before DSM (kW) | Peak Load After DSM (kW) | Peak Reduction (kW) | Percentage Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Conditioner | 2.382 | 0.4888 | 1.89 | 79.3 |

| Clothes Washer | 0.0061 | 0.0045 | 0.0016 | 26.23 |

| Kitchen Appliances | 0.072 | 0.031 | 0.041 | 56.9 |

| Miscellaneous Loads | 0.702 | 0.207 | 0.495 | 70.5 |

5.2. Aggregated Load DSM

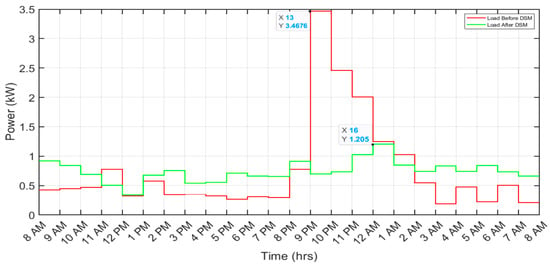

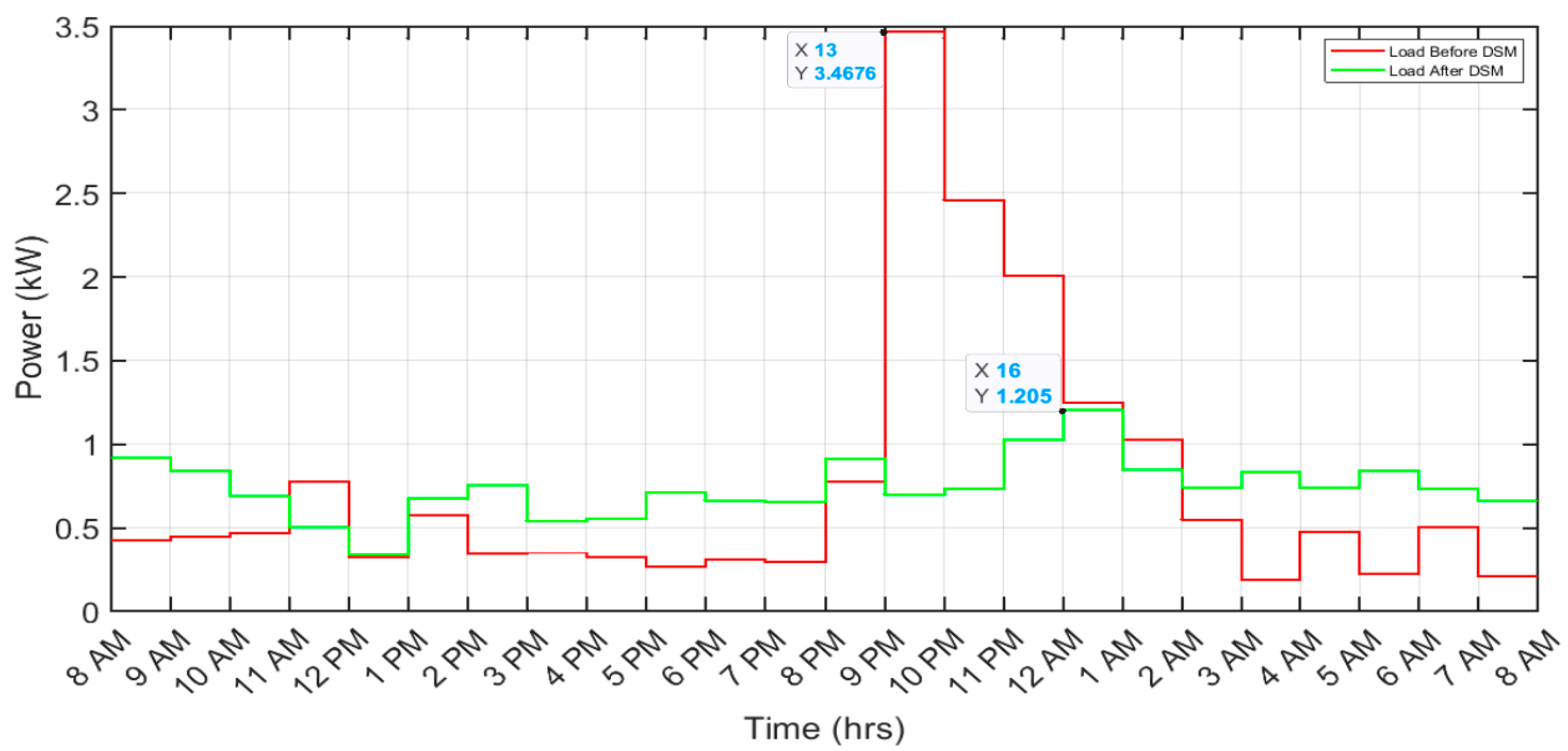

The individual appliances’ shift has an effect on consumer electricity bills and peak reduction. This is because before the implementation of DSM, all loads were unscheduled, but after DSM was implemented, some shiftable loads were scheduled based on the RTP signal; such loads contribute to the overall consumer electricity cost and also to peak demand reduction. The impact of the implemented DSM technique on aggregated load (overall household load) is visually depicted in Figure 8.

The cost of total energy consumption by a consumer at each measured hour is equal to the total energy consumed by all appliances at this hour, multiplied by the energy consumption price at that hour, as given in Equation (6):

where Costi is the total cost for hour i, and pi is the energy price at hour i. Ei (aj) is the energy consumed by appliance j in hour i and n is the total number of appliances. The total cost per day is the summation of each hour’s cost, as given below.

Table 8 summarizes and compares the overall energy consumption cost and peak load demand of a household with the implementation of the employed demand-side management technique. From the presented results in Table 8, it is evident that employing the DSM technique effectively reduces both the cost and peak demand of a household. The consumer effectively decreased their electricity bills from 237 cents to 208 cents per day, reflecting a substantial 12.24% reduction in the daily electricity expenditure.

Furthermore, the peak demand witnessed a significant decrease from 3.467 kW to 1.205 kW, translating to an impressive 65% reduction in the household’s daily peak demand. These findings indicate effective household load management in response to the RTP signal. Moreover, it is worth noting that with DSM, cost savings are dependent upon customer inconvenience, with greater waiting periods resulting in increased savings. In a well-implemented DSM framework, the advantages extend beyond customer benefits to a positive impact on the utility. A notable advantage is the reduction in the peak-to-average ratio (PAR), contributing to enhanced grid efficiency, stability, capacity, and a decrease in power generation costs.

Figure 8.

Demand-side management results for aggregated load.

Figure 8.

Demand-side management results for aggregated load.

Table 8.

Impact of demand-side management on energy consumption cost and peak demand for aggregated load.

Table 8.

Impact of demand-side management on energy consumption cost and peak demand for aggregated load.

| Overall Cost before DSM (cents) | 237 |

| Overall Cost after DSM (cents) | 208 |

| Overall Cost Reduction (cents) | 29 |

| Percentage Reduction (%) | 12.24 |

| Peak Load before DSM (kW) | 3.467 |

| Peak Load after DSM (kW) | 1.205 |

| Peak Reduction (kW) | 2.26 |

| Percentage Reduction (%) | 65 |

6. Conclusions

This study presents the implementation of the DSM technique of load shifting through an optimization technique employing a GA. This proposed GA-based approach effectively reduces both electricity cost and peak demand for shiftable household appliances. Specifically, AC use exhibits a reduction in cost and peak demand of 17.4 cents and 1.89 kW, respectively. Similarly, clothes washer use experiences a decrease in cost and peak demand by 0.2 cents and 0.0016 kW, respectively, while kitchen appliance use witnesses a reduction of 2.9 cents in cost and 0.041 kW in peak demand. Additionally, miscellaneous loads demonstrate a decrease in cost and peak demand by 8.4 cents and 0.495 kW, respectively. The cumulative impact of load-shifting strategies on overall household electricity cost and peak demand was observed to decrease by 29 cents and 2.26 kW, respectively, which signifies the effectiveness of the proposed GA-based load-shifting technique in terms of optimizing both cost and peak demand for enhanced energy efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.K. and A.U.R.; methodology, S.A.K., A.U.R., and A.A.; software, S.A.K.; validation, A.U.R., A.A., and F.H.M.; formal analysis, S.A.K.; investigation S.A.K.; resources, A.U.R. and A.A.; data curation, S.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.U.R., A.A., and F.H.M.; visualization, A.U.R., A.A., and F.H.M.; supervision, A.U.R. and A.A.; project administration, A.U.R. and A.A.; funding acquisition, A.A., F.H.M., and W.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Ghulam Ishaq Institute of Engineering Sciences and Technology, Pakistan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, Q.; Zhou, M. The Future-Oriented Grid-Smart Grid. J. Comput. 2011, 6, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, B.; Singh, K.; Brar, Y.S. An Introduction to Smart Grid and Demand-Side Management with Its Integration with Renewable Energy. In Advances in Smart Grid Power System. Network, Control and Security; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare, M.S.; Abdulkarim, A.; Zeeshan, M.; Shuaibu, A.N. A Comprehensive Overview on Demand Side Energy Management towards Smart Grids: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Direction. Energy Inform. 2023, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moed, M.S.; Mahmud, S.; Aziz, T.; Abdullah-Ai-Nahid, S.; Khan, T.A. A Consumer-Friendly Demand Side Management Technique for Residential Loads Supported by Two Stage Genetic Algorithm-Based Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2022 Global Energy Conference (GEC), Batman, Turkey, 26–29 October 2022; pp. 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewale, A.; Mokhade, A.; Funde, N.; Bokde, N.D. A Survey of Efficient Demand-Side Management Techniques for the Residential Appliance Scheduling Problem in Smart Homes. Energies 2022, 15, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatziargyriou, N. Book Review: Demand-Side Management: Concepts and Methods. 2nd Ed.: C. W. GELLINGS and J. H. CHAMBERLIN. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Educ. 1995, 32, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, I.K. Demand Side Management: Load Management, Load Profiling, Load Shifting, Residential and Industrial Consumer, Energy Audit, Reliability, Urban, Semi-Urban and Rural Setting; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, D.P.; Nagrath, I.J. Modern Power System Analysis; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003; 694p. [Google Scholar]

- Taveres-Cachat, E.; Grynning, S.; Thomsen, J.; Selkowitz, S. Responsive Building Envelope Concepts in Zero Emission Neighborhoods and Smart Cities—A Roadmap to Implementation. Build. Environ. 2019, 149, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Piette, M.A. Solutions for Summer Electric Power Shortages: Demand Response and Its Applications in Air Conditioning and Refrigerating Systems. Refrig. Air Cond. Electr. Power Mach. 2008, 29, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.; Hong, S.H. Incentive-Based Demand Response for Smart Grid with Reinforcement Learning and Deep Neural Network. Appl. Energy 2019, 236, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, I.; Robu, V.; Couraud, B.; Kirli, D.; Norbu, S.; Kiprakis, A.; Flynn, D.; Elizondo-Gonzalez, S.; Wattam, S. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Approaches to Energy Demand-Side Response: A Systematic Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 130, 109899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradac, Z.; Kaczmarczyk, V.; Fiedler, P. Optimal Scheduling of Domestic Appliances via MILP. Energies 2015, 8, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahia, Z.; Pradhan, A. Optimal Load Scheduling of Household Appliances Considering Consumer Preferences: An Experimental Analysis. Energy 2018, 163, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamii, J.; Trabelsi, M.; Mansouri, M.; Mimouni, M.F.; Shatanawi, W. Non-Linear Programming-Based Energy Management for a Wind Farm Coupled with Pumped Hydro Storage System. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damgacioglu, H.; Bastani, M.; Celik, N. A Dynamic Data-Driven Optimization Framework for Demand Side Management in Microgrids. In Handbook of Dynamic Data Driven Applications Systems, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimi, S.; Ben Maissa, Y.; Tamtaoui, A. Optimization Approaches for Demand-Side Management in the Smart Grid: A Systematic Mapping Study. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1630–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Javaid, N.; Shaheen, N.; Iqbal, Z.; Rehman, G.; Muhammad, K.; Ahmad, I. An Efficient Genetic Algorithm Based Demand Side Management Scheme for Smart Grid. In Proceedings of the 2015 18th International Conference on Network-Based Information Systems, Taipei, Taiwan, 2–4 September 2015; pp. 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaini, F.A.; Sulaima, M.F.; Razak, I.A.W.A.; Zulkafli, N.I.; Mokhlis, H. A Review on the Applications of PSO-Based Algorithm in Demand Side Management: Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 53373–53400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wei, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhu, H.; Yu, Z. A New Fast Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm: The Saltatory Evolution Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm. Mathematics 2022, 10, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rehman, A.; Hafeez, G.; Albogamy, F.R.; Wadud, Z.; Ali, F.; Khan, I.; Rukh, G.; Khan, S. An Efficient Energy Management in Smart Grid Considering Demand Response Program and Renewable Energy Sources. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 148821–148844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, N.K.; Mohanani, R.; Singh, N.K.; Singh, A.K. Demand Side Energy Management in Hybrid Microgrid System Using Heuristic Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Taipei, Taiwan, 14–17 March 2016; pp. 1910–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logenthiran, T.; Srinivasan, D.; Shun, T.Z. Demand Side Management in Smart Grid Using Heuristic Optimization. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2012, 3, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkireb, C.; Dembele, A.; Jouglet, A.; Denoeux, T. A Linear Programming Approach to Optimize Demand Response for Water Systems under Water Demand Uncertainties. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Smart Grid and Clean Energy Technologies (ICSGCE), Kajang, Malaysia, 29 May–1 June 2018; pp. 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Xiao, F. Price-responsive model-based optimal demand response control of inverter air conditioners using genetic algorithm. Appl. Energy 2018, 219, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, I.; Alves, M.J.; Henggeler Antunes, C. A Population-Based Approach to the Bi-Level Multifollower Problem: An Application to the Electricity Retail Market. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2019, 28, 3038–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonta, C.I.; Kemp, A.; Edokpia, R.; Monyei, C.G. A Heuristic Based Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm for Energy Efficient Smart Homes. In Proceedings of the IAEMM Conference 2016, Montreal, QC, Canada, 1–3 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, Q.Z. Optimizing Energy Consumption with Combined Operations of Microgrids for Demand Side Management in Smart Homes. Ph.D. Thesis, Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi, Pakistan, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Yu, F.; Huang, P.; Liu, G.; Zhang, M.; Sun, R. Game-theoretic evolution in renewable energy systems: Advancing sustainable energy management and decision optimization in decentralized power markets. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 217, 115776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jailani, N.L.M.; Dhanasegaran, J.K.; Alkawsi, G.; Alkahtani, A.A.; Phing, C.C.; Baashar, Y.; Capretz, L.F.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Tiong, S.K. Investigating the Power of LSTM-Based Models in Solar Energy Forecasting. Processes 2023, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spantideas, S.T.; Giannopoulos, A.E.; Trakadas, P. Autonomous Price-Aware Energy Management System in Smart Homes via Actor-Critic Learning With Predictive Capabilities. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 15018–15033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polap, D.; Srivastava, G.; Jaszcz, A. Energy Consumption Prediction Model for Smart Homes via Decentralized Federated Learning with LSTM. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, F.; Kang, D.K.; Ahmed, M.A.; Kim, Y.C. Energy Demand Load Forecasting for Electric Vehicle Charging Stations Network Based on ConvLSTM and BiConvLSTM Architectures. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 67350–67369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Rehman, A.U.; Arshad, A.; Alqahtani, M.H.; Mahmoud, K.; Lehtonen, M. Effective Voting-Based Ensemble Learning for Segregated Load Forecasting With Low Sampling Data. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 84074–84087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercel, G. An Overview of the Home Energy Management System. Bull. Polytech. Inst. Iași. Electr. Eng. Power Eng. Electron. Sect. 2021, 67, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asih, A.M.S.; Sopha, B.M.; Kriptaniadewa, G. Comparison Study of Metaheuristics: Empirical Application of Delivery Problems. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2017, 9, 1847979017743603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, S.; Chauhan, S.S.; Kumar, V. A Review on Genetic Algorithm: Past, Present, and Future. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 8091–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, R.; Arbelaez, A.; Díaz, J.F. Online over time processing of combinatorial problems. Constraints 2018, 23, 310–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanat, A.; Almohammadi, K.; Alkafaween, E.; Abunawas, E.; Hammouri, A.; Prasath, V.B.S. Choosing Mutation and Crossover Ratios for Genetic Algorithms—A Review with a New Dynamic Approach. Information 2019, 10, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.