Abstract

This study calculates the intensity of radiation received by two types of greenhouses: Even Span and Modified Arched geometry. The Even Span greenhouse is covered with glass, while the Modified Arched greenhouse is covered with polyethylene plastic sheets. Both greenhouses are located in the same geographical area. The analysis incorporates various forms of radiation, including incident, reflected, transmitted, and absorbed radiation, calculated based on solar angles. Notably, this study does not include temperature data. The greenhouse covering material is considered transparent, and parameters such as the refractive index and the attenuation coefficient of the materials are integrated into the calculations. The integration of these specific indices allows for the calculation of radiation across different materials. Additionally, this study assesses radiation for all sides of the greenhouse, rather than focusing solely on the roof. The research analyses data from a total of 396 days, with measurements taken every ten minutes from a meteorological station situated near the greenhouses. MATLAB (R2021b) software is utilised for computational purposes to solve the relevant equations, while IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0.0.0 software is employed for statistical analysis of the results. The statistical analysis regards data collected from sunrise to sunset, varying by month. It is important to note that radiation values recorded with a negative sign are retained in this analysis, as they are considered useful for capturing the temporal and spatial dynamics of radiation within the model. The analysed greenhouses are geographically situated in the Psachna area of Messapia, Evia Prefecture, Greece.

1. Introduction

In recent years, greenhouse farming has become increasingly popular, recognised as a burgeoning industry capable of meeting the rising demand for agricultural products [1]. This method of agriculture is more intensive compared to traditional field farming, yielding ten times more per unit of cultivated area [2]. Official FAO statistics estimate that the total area of greenhouses worldwide, including glass and plastic structures, is 405,000 hectares [3]. In Greece, greenhouse crops account for approximately 0.12% of the country’s cultivated land, totalling around 5600 hectares [4].

Greenhouses can vary widely in design, geometry, and characteristics, reflecting the diverse climatic, economic, and social conditions of different regions [5]. Enhancing the sustainability of greenhouses is closely linked to the effectiveness of microclimate control systems and energy sources, which are influenced by factors such as covering materials, water and nutrient supply, and pest and disease management [2]. Greenhouses protect crops against external conditions [6]. They facilitate growth and improve both the quantity and quality of the produce [6]. They also allow for year-round planting and harvesting [7], even in regions where adverse climatic conditions typically hinder agricultural activities [8]. Advanced technology in greenhouse production positively impacts water management and usage [9,10].

Selecting the right type of greenhouse is crucial and hinges on the producer’s expertise [11]; this decision should consider essential criteria such as the specific climate of the installation area, the quality and availability of resources, financial capacity, market size, and applicable regulations [12,13]. Essential factors such as crop type, climatic conditions, length of the growing season, investment capital, and costs dictate the choice of greenhouse type and equipment [14]. By effectively utilising environmental control elements, the producer can regulate temperature, humidity, light intensity, and CO2 concentrations to maintain optimal conditions within the greenhouse [15,16]. It is important to note that managing the internal environment of the greenhouse results in energy consumption [17].

The greenhouse operates as a dynamic system influenced by energy exchange with the environment and temperature changes inside, resulting from heat and mass transfer [18]. To gain a precise understanding of this dynamic greenhouse system, simulation systems are employed, focusing on design elements, climate management, and interior performance [19,20]. The primary objective is to model the system using mathematical models [5]. Successfully modelling the greenhouse system is a clear challenge due to its intricate environment [21].

The literature review reveals that no similar studies have been conducted in the selected geographical area for this research. The greenhouses proposed and examined in this work are strategically located in Psachna, within the Messapia region of Evia Prefecture, Greece. This area is undeniably significant due to its vibrant agricultural activity and the potential for high-production greenhouses. Moreover, the region’s climatic conditions warrant attention, and this work provides a detailed report that highlights the prevailing weather patterns.

1.1. Objective

This study examines the radiation intensity received by greenhouses with two geometries: Even Span and Modified Arched, both commonly used by growers in Greece and compliant with national legislation. The greenhouses analysed are closed solar passive systems in the same geographical location, same orientation, and same dimensions, but using different covering materials—glass for Even Span and polyethylene for Modified Arched (which are typically used in the corresponding geometries). The proposed mathematical model effectively accommodates various covering materials, allowing for the assessment of both transparent and translucent options (such as agrophotovoltaics), and factors in critical parameters like the refractive index (Z) and attenuation index (K) for accurate radiation calculations. For instance, in the case of agrophotovoltaics, the optical properties of the covering material as well as the characteristics of the panel materials could be taken into account (including their transmittance rates) [22,23].

The study assesses different types of radiation—incident, reflected, transmitted, absorbed, and outgoing—using equations based on solar angles, after a thorough literature review. It calculates radiation for all sides of the greenhouse, processing data from 396 days with ten-minute intervals. Notably, data from a nearby meteorological station supported the findings.

1.2. Novelty—Innovation

The Mendeley platform was used to search for relevant literature using the keywords “Psachna” and “Greece,” resulting in 11 references, none of which addressed greenhouse studies in the area (see Supplementary Material S1, Table S1). A search using the keywords “radiation” and “greenhouse” yielded 37 references (detailed in Table S2 of Supplementary Material S1), none of which provided a comprehensive mathematical model factoring in solar angles for the specific geographical location, using a complete set of mathematical equations for calculating solar radiation in a greenhouse within the country.

For a third search on the Mendeley platform, the keywords “radiation” and “greenhouse” were used. This time, the results related to radiation were filtered out, excluding all the irrelevant topics (medical applications, atmospheric gases, aerosols, carbon dioxide, climate change, greenhouse effect, greenhouse gas emissions, studies on plant cultivation, biometric factors in growth stages, photosynthesis, and evapotranspiration). The further search included the term “solar” before “radiation” was included, excluding materials related to solar biomass, solar fuels, solar collectors, panels, and solar dryers.

In the final search, the phrase “mathematical model” was used. Table S3 in Supplementary Materials S1 lists references to manuscripts that specifically propose mathematical models for calculating radiation, excluding those that do not focus on radiation calculations as their primary subject. A broad bibliographic search using the keywords “mathematical model,” “solar radiation,” and “greenhouse” yielded references proposing mathematical solutions. However, the model introduced in this work appears to be original and not found in prior studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Greenhouse’s Characteristics

2.1.1. Greenhouse’s Geometry

Greenhouses are defined by their geometric designs, primarily based on the shape of their roofs. The two most common roof styles are the Even Span roof and the Modified Arched roof, which features two sloping levels. Additional key characteristics include the height and width of the greenhouse opening. The greenhouse design varies by local climate, affecting its efficiency in nurturing the crops it supports. This particular study, adhering to the legislative framework of Greece [24], will comparatively analyse two types of greenhouses: the Venlo-Type or Even Span greenhouse and the Modified Arched Greenhouse.

The Even Span greenhouse type is well-recognised in agricultural production; therefore, it has been the focus of various studies aimed at controlling the internal climate, improving energy efficiency, and reducing operational costs [2,18,21,25,26,27]. Additionally, it is designed to minimise water consumption [28]. Literature related to the Arched Type greenhouses includes various studies, such as those focusing on energy-saving technologies [25], the load-carrying capacity of Gothic-type greenhouse covers [14], optimal microclimate control, energy consumption reduction [2], and thermal behaviour management through heat storage systems [29].

2.1.2. Greenhouse’s Cover Material

The mechanical and physical properties of greenhouse covering materials play a crucial role in shaping the microclimate within the structure, protecting crops, equipment, and workers, as well as ensuring the facility’s structural safety [14]. These materials create optimal conditions for plant cultivation inside the greenhouse [27]. Thanks to their transparent nature, greenhouses act as solar collectors [30], capturing solar radiation, which consists of three bands: ultraviolet radiation (UV, 300–400 nm), photosynthetically active radiation (PAR, 400–700 nm), and near-infrared radiation (NIR, 700–2500 nm) [27]. Choosing the right greenhouse covering material is essential for its performance and productivity, as it determines both the quantity and quality of light that reaches the crops.

Although not all incident radiation can penetrate the covering material completely, it is important to maximise the percentage of transmittance. Factors such as dust and water droplets on the covers can reduce light transmission by up to 8%, as well as thermal radiation [31]. Light diffusion is another critical requirement for greenhouse covering materials. When selecting a covering material, multiple parameters must be considered. These include its weight, lifespan, repair potential, and initial purchase and installation costs [31], as well as evaluating how much light it transmits and its energy flow [31].

The transmittance of solar radiation through greenhouse cover material varies over time and directly influences its metabolism throughout its life cycle [32]. The well-being of crops inside the greenhouse is affected by the direct and diffuse components of solar radiation, which is why transparent casings are utilised [33]. A study by Maraveas [34] compared various covering materials, including polyvinyl chloride (PVC), acrylic, D-polymer, linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE), polyolefins, and silica glass. The study revealed that each covering material has its advantages and limitations.

According to the global research organisation “NSW Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development” [31], the use of glass as a greenhouse covering material has several advantages. It transmits a high rate of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), has low transmission of ultraviolet (UV) radiation, retains heat at night, and is very durable over time [31]. However, it is also associated with high maintenance costs. In contrast, the same source [31] examines plastic greenhouse covering materials, such as plastic films, polyethylene, EVA (vinyl acetate), and PVC (polyvinyl chloride). These materials exhibit properties like infrared (IR) reflection, UV blocking, heat retention at night, and minimal to no requirement for chemical pest control. Achieving these benefits often necessitates improvements through the use of additives, which can enhance both the amount of dust that adheres to the films and the formation of droplets on their surface. Despite this, the lower cost of plastic materials makes them more commonly used.

For the Even Span greenhouse, glass will be used as its covering material because it is ideal for this geometry. The sun emits electromagnetic radiation of various wavelengths, which is partially absorbed, reflected, and transmitted by the glass [33]. The specific characteristics of any glass surface, which depend on the type of glass and its manufacturing process, influence how it filters light and heat [33]. Research has shown that anti-reflective coatings can effectively reduce the glass reflectivity, allowing light to enter the greenhouse [35]. Since this study aims to create a greenhouse model using commercially available materials, the selected glass will meet existing market specifications.

The Mediterranean regions are characterised by a Mediterranean climate, featuring relatively mild winters and particularly hot summers, with high levels of solar radiation. In these areas, greenhouses with curved roofs and plastic coverings are especially common [33]. The Modified Arched geometry greenhouse is particularly well-known and is widely used across many countries, including Greece [14]. For this study, the plastic sheets cover greenhouse material offers better properties than typical plastic membranes, without requiring additional additives for durability over time [31].

2.2. Description of Modelled Greenhouses

The greenhouse chosen for this study is situated in the Psachna area, within the Municipality of Dirfion-Messapia, in the Prefecture of Evia. To provide accurate coordinates and dimensions for calculating the selected area, the electronic resources of the Hellenic Cadastre were utilised [36].

The geographical coordinates of the greenhouse’s location are presented in Table 1, while a photographic image of the site is shown in Figure 1. According to the computer program on the official Hellenic Cadastre website, the total surface area of the site is 13,846.46 m2, which converts to approximately 3.42 acres or 1.39 ha.

Table 1.

Coordinates.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the modelled greenhouse [36].

Google Earth also provided the elevation for the specific area, which was determined to be 36 m.

2.2.1. Climatic Classification

In studying greenhouses, it is essential to consider the climatic classification of their geographical location [37]. Psachna, located in Evia, Greece, is characterised by a Mediterranean climate, as confirmed by the Köppen climate classification [38]. Climatic data for the area collected by a meteorological station located on the roof of the Energy and Environmental Research Laboratory (E2ReLab) at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. The coordinates of this station are 38°34′11.3″ N (latitude) and 23°38′57.4″ E (longitude), which are in proximity to the selected area. For this study, data was collected from a meteorological station over a period of 396 calendar days, beginning on 1 May 2021, at 00:10 and concluding on 31 May 2022, at 23:50. The selection of this time frame was also advised by other research and studies that validate the appropriateness of this duration, as existing greenhouse simulations commonly reference climate data from a standard meteorological year [27].

2.2.2. Geometry and Covering Material

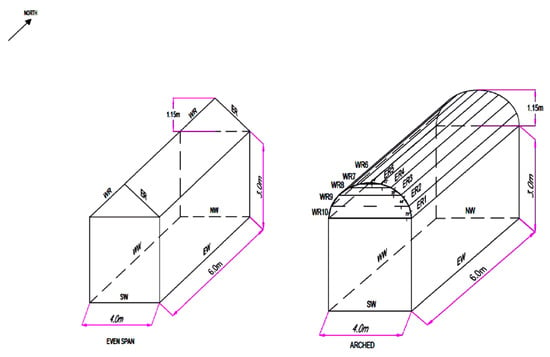

Designing a greenhouse is a complex task because its performance relies on various factors, including climate, building materials, technological systems, and intended use [33]. Analysing annual external climatic parameters alongside the internal microclimate is crucial for determining the greenhouse’s shape, orientation, and materials [33]. This study focuses on a greenhouse, which is a passive system that maintains a constant size and orientation in both geometric cases discussed previously. Each case features its specific covering material. When proposing greenhouse systems, it is essential to consider the location, as it significantly influences the external climatic conditions [39]. Both greenhouses are located at the same coordinates previously mentioned. The selected orientation has the largest sides of the greenhouse facing West and East [40] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Basic Central Unit (CU).

The Basic Central Unit is designed in accordance with current legislation [24], featuring the following characteristics (Table 2 and Table 3):

Table 2.

Basic Central Unit (CU) of Even Span greenhouse geometry greenhouse.

Table 3.

Basic Central Unit (CU) of the Modified Arched geometry greenhouse.

In this paragraph, no reference will be made to the openings included in the greenhouses of different geometries. Greenhouses will initially be studied as passive systems based on the solar radiation they receive.

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Methodology Analysis

Incoming radiation is calculated using mathematical models that rely on the geographical location of the greenhouses and weather data collected from a nearby station of a year.

It is important to note that meteorological stations provide information on global radiation, which pertains to the horizontal surface [41]. According to Duffie and Beckman [42], most available radiation data includes both direct and diffuse radiation, measured by instruments that track radiation over time, yet this data still relates to horizontal surfaces. The modelled greenhouses feature two types of geometries: Even Span and Modified Arched. However, the data from the meteorological station and existing data do not correspond reliably or adequately. Therefore, it should be used a mathematical model to calculate the incident radiation for each of these two cases.

For an accurate assessment of the available solar energy, it is crucial to consider the specific geographical area in question. Calculating radiation based on the meteorological and geographical data for that area will facilitate better mapping. This improved mapping will enhance the performance of applications and increase accuracy, which, in turn, will contribute to a comprehensive study. The results will inform both greenhouse configuration and the optimisation of cultivation microclimate conditions, leading to reduced reliance on conventional energy sources and lower operational costs.

Information about the geographical location of the greenhouses is provided in Section 2.2.1. Detailed information regarding the greenhouses and their dimensions can be found in Section 2.2.2 as well as in Table 2 and Table 3. Since the study focuses on an industrial-type greenhouse that is large and equipped appropriately, the Basic Central Unit will be analysed for each type. To facilitate calculations, the greenhouse has been divided into four distinct sections based on its perimeter masonry for both geometries. Additionally, the roof has been segmented into two parts for the Even Span design and into ten parts for the Modified Arched design.

The orientation of the greenhouse is established with the longer side aligned along the West–East axis, while the shorter side is oriented from South to North. This orientation applies to both geometrical configurations of the greenhouse. The coordinate system employed for solving the equations is based on the Coordinates in decimal form WGS84. Recordings are taken every ten minutes throughout the hour for each day within the specified annual period selected for this study. To solve the radiation equations, it is necessary to calculate the relevant angles. MATLAB R2021b software is utilised as a computational tool to solve these equations.

2.3.2. Calculating Solar Angles

To calculate equations related to solar radiation, it is essential to determine several angles: the Hour Angle (ω), the Latitude (φ), the Declination Angle (δ), the Azimuth Angle of the surface (γ), the Inclination Angle of the surface (β), and the Incidence Angle (θ).

The Hour Angle (ω), expressed in degrees (°), is calculated using the equation [43,44,45]:

ST represents the local solar time, which is determined using the following equation [43,44]:

To solve Equation (2), you need data including LST, which is the standard local time, LST (the standard meridian for the study area), and LΙ (the local meridian for the study area). The standard local time (LST) is derived from the time difference between each country and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). It is important to note that the ± sign is used as follows: (+) is used for the western hemisphere, while (−) is for the eastern hemisphere, with Greece falling into the latter category. The variable c represents the time correction for the transition between standard time and daylight-saving time. This correction is equal to 1, which is subtracted from the last Sunday in March to the last Sunday in October, marking the period during which this time change occurs. The time correction function Et is calculated using the equation [41,44]:

The determination of “n day” based on days of the year is provided by Klein [46], with the restriction that it is not applicable for .

Table 4 outlines parameters related to LST (the standard meridian of the study area) and LΙ (the local meridian of the study area).

Table 4.

Latitude, Standard and Local Meridian.

The deviation angle δ as calculated in degrees (°) is given by the Cooper equation [42,44,45,46]:

It has been noted, based on Klein’s n-day determination table [46], that the maximum rate of deviation change is 0.4° per day. This deviation is considered to fluctuate throughout the year [42,46].

The azimuth angle () of a surface is defined as follows: 0° for north-facing surfaces, 180° for south-facing surfaces, 90° for east-facing surfaces, and −90° for west-facing surfaces.

The equation that relates the incidence angle () to the deviation angle, latitude, inclination, azimuth angle, and hour angle, applicable to surfaces aligned in any direction concerning the local meridian, is given as follows [40,41,43,44,45,47]:

It is important to note that when the angle exceeds 90°, the sun is located behind the surface [42]. Additionally, reducing the angle of incidence of direct radiation on the surface leads to maximised incident direct radiation [42].

The solar altitude angle is expressed by the following equation [43,47]:

The zenith angle , also known as the zenith distance or polar angle, can be easily calculated from the solar altitude angle. The formula for calculating the zenith angle is as follows [43]:

To calculate the transmission of radiation, it is essential to consider the angle of refraction . The formula for determining the angle of refraction in relation to the ratio of the refractive indices (refractive index ) [43] is derived from Snell’s Law [48] and is expressed as follows:

The refractive index is influenced by the type of material and is determined by its composition and wavelength. In greenhouses, ordinary glass is typically used for the covering material; neither medium glass made from flint nor acrylic glass is used. In this scenario, the refractive index of the glass is [49]. Additionally, when plastic covering material is considered, the focus will be on polyethylene sheets, which have a refractive index of [50].

To calculate the solar angles when radiation strikes an inclined or curved surface, such as a greenhouse roof, it is essential to incorporate the slope angle β in degrees. For the Even Span greenhouse, the roof slope angle β has been determined to be 30°. This angle was chosen based on the orientation of photovoltaic panels, as it has been shown to enhance the efficiency of the incident radiation. In the case of the Modified Arched greenhouse, the roof is divided into two main sections based on orientation. The section facing west is designated as WR, while the section facing east is designated as ER. Each of these sections is further divided into five sub-surfaces: ER1, ER2, ER3, ER4, and ER5 for the eastern section, and WR6, WR7, WR8, WR9, and WR10 for the western section. The angles for each sub-surface are calculated using a design program, as shown in Table 3.

2.3.3. Calculation of Radiation

To estimate the solar radiation incident on the greenhouse effectively, mathematical equations that calculate the radiation hitting the roof as well as the horizontal sides of the greenhouse are solved. Although the contribution from the sides is relatively small and is often overlooked in many studies, it is important to consider for a comprehensive analysis. The total radiation includes the sum of direct radiation, diffuse radiation, and radiation reflected from the ground. All equations to be solved in MATLAB for each scenario are outlined accordingly.

Coefficients for Solving Radiation

Chen, Ma, and Pang [47] propose Equations (10a) and (10b) for calculating atmospheric mass, which are also referenced in a study by Huang et al. [40]. For the ratio of the atmospheric mass through which direct radiation passes to the mass, it would pass when the sun is at zenith ; the following is valid:

For where is the angle of the solar altitude (10a).

For , , where is the angle of the solar altitude (10b).

Similarly, the equation proposed by Chen, Ma, and Pang [47] for calculating the large gas volume under certain ground conditions is given by:

The atmospheric transparency coefficient of direct radiation is given by the equation of Kreith & Kreider [47,51] and relates the volume of the local atmosphere to the atmospheric conditions:

The atmospheric transparency coefficient of diffuse radiation is given by the equation of Liu & Jordan [47,52], the graph of which is a straight line obtained by the method of least squares:

Direct Radiation on a Horizontal Surface

According to Psiloglou and Kambezidis [53], the intensity of direct radiation reaching a horizontal external surface, denoted as , can be expressed using the equation:

In this equation, represents water vapor transmittance, stands for Rayleigh scattering, is ozone absorption, indicates the absorption of uniformly mixed gases, and is the total aerosol attenuation. Duffie & Beckman [42], elaborate on the same equation, describing direct solar radiation on a horizontal surface ( under clear sky conditions. They conclude that extra-atmospheric radiation ( is diminished due to absorption and scattering processes within the atmosphere. Each factor Τ in the equation signifies transmittance.

In order to simplify calculations, the product of the individual transmittance coefficients is replaced by a single atmospheric transparency coefficient (as shown in Equation (12)). This coefficient provides an approximation of total radiation attenuation [43] and is widely accepted for calculating direct radiation on a horizontal surface, maintaining a high degree of accuracy. The equation is formulated as follows:

Diffuse Radiation on a Horizontal Surface

The diffuse radiation intensity reaching a horizontal external surface is given by the equation [54]:

Total Radiation on a Horizontal Surface

The total radiation intensity reaching a horizontal external surface is given as the sum of the direct radiation and diffuse radiation with the formula [45]:

Direct Radiation on an Inclined Surface

The direct radiation reaching the inclined outer surface of the greenhouse , based on Chen, Ma & Pang [47], Zang et al. [54] and Equation (14), is formulated as:

Diffuse Radiation on an Inclined Surface

The diffuse radiation reaching the inclined outer surface of the greenhouse , based on Chen, Ma & Pang [47], Zang et al. [54] and Equation (15), is formulated as:

Total Radiation on an Inclined Surface

The total solar radiation reaching the inclined outer surface of a greenhouse during a day is given as the sum of the direct radiation and the diffuse radiation by the equation [45]:

Slope Factors

The reflected ground radiation slope factor is given by the isotropic model equation [43,55,56]:

where ρ is the ground albedo, which is the ratio of reflected to incident solar radiation [43]; it is not considered constant for the surface and varies based on the spectral and angular distribution of light, such as the position of the sun (time of day, season, latitude), conditions (cloudiness, sunshine) [57] and other factors related to the deviation from Lambert’s equilibrium law, as well as ground variations [41]. According to Gueymard [58], the ground albedo has a constant value, which is set at .

The reflected direct radiation slope factor is given by the isotropic model equation [43,55,56]:

The reflected diffuse radiation slope factor is given by the isotropic model equation [43,55,56]:

Reflected Ground Radiation

This paragraph refers to the radiation reflected by the ground when the sun’s rays reach the ground outside the greenhouse. The calculation of the radiation reflected by the ground serves to better approximate the radiation received by the greenhouse, as the reflected radiation is part of the diffuse radiation. Diffuse radiation, in addition to the type of radiation scattered by the atmosphere, could also include the type of radiation reflected by the ground. For the calculation of the radiation reflected by the ground, it is noted that:

- The ground is considered as a pure diffusion surface

- The variation in the properties of transparent materials is not taken into account, and

- The environment around the solar greenhouse is considered as having its own reflectivity

The ground-reflected radiation is given as a function of the global radiation and the reflected radiation slope factor . The equation for the total ground-reflected radiation is given by equation [43,55,56,59]:

The reflected direct radiation is given as a function of the direct radiation in the horizontal surface and the reflected radiation slope factor . The equation for the total reflected direct radiation is given by the equation [43,55,56,59]:

The reflected diffuse radiation is given as a function of the diffuse radiation in the horizontal surface and the reflected radiation slope factor . The equation for the total reflected direct radiation is given by the equation [43,55,56,59]:

The total reflected radiation is given by equation [43]:

Factors for Solving Atmospheric Radiative Transmission

Hottel Model [42,60]:

Components for Calculating Radiation Transmission

The components included in the formula for calculating radiation transmission are the perpendicular component and the parallel component , which are given in relation to the angle of incidence and the angle of refraction by the following formulas according to the law of Fresnel & Bouguer [42,59,61]:

Transmittance

Radiation reaches the surface of the greenhouse, part of which is reflected and another part of which enters the greenhouse space. The radiation that enters the greenhouse serves both for natural lighting and for heating the greenhouse. The reason that the radiation that reaches the greenhouse penetrates it is the transparent materials with which it is covered. The transparent greenhouse covering materials affect the transmission of radiation through their optical parameters. The transmission of radiation that reaches the greenhouse and ultimately penetrates it is also affected by its angle of incidence. The law of Fresnel & Bouguer [42] gives the transmission of radiation in relation to the angle of incidence and the optical parameters of the material [54,59,62]:

Radiant Transmission

Zhang et al. [54] relate the transmitted radiation to the radiation on an inclined surface and the radiant transmissivity. The direct radiation transmission is given as a function of the direct radiation on an inclined surface and the transmissivity . The equation for the total direct radiation transmission is given by the equation:

Similarly, the diffuse radiation transmission is given as a function of the diffuse radiation on an inclined surface and the transmissivity [54]. The equation for the total diffuse radiation transmission is given by the equation:

The total radiation transmission is given by the equation [45]:

Components to Calculate Radiation Absorption

The components included in the formula for calculating radiation absorption are the perpendicular component and the parallel component , which are given in relation to the perpendicular component and the parallel component of radiation transmission, as well as from the radiation absorption by the following formulas. The perpendicular component and the parallel component of radiation diffusion have already been calculated for the needs of calculating radiation transmission through Formulas (30) and (31) respectively. Radiation transmission is given by Bouguer’s Law in relation to the material’s attenuation coefficient , the medium’s thickness and the angle of refraction , through the following formula [59,61,62]:

The material attenuation for normal glass, with a refractive index of , is assumed to be and the glass thickness is [49]. The material attenuation for polyethylene, with a refractive index of , is assumed to be and the polyethylene thickness is [50].

According to the law of Fresnel and Bouguer [42,59,61]:

Absorptivity

The calculation of the radiation absorptivity of the cover is crucial for a better understanding of the thermal loads that develop inside the greenhouse and, consequently, the temperatures that occur within it. In this study, radiation is examined for all sides of the greenhouse, not just its roof; this means that the radiation absorbed is studied equally for all sides. The radiation absorption is given by the following formula [61]:

Radiation Absorption

The literature relates the absorbed radiation to the transmitted radiation and the absorption [59]. The absorption of direct radiation is given as a function of the transmitted radiation and the absorptivity . The equation for the total absorbed direct radiation is given by the equation:

The absorption of diffuse radiation is given as a function of the transmitted radiation and the absorptivity . The equation for the total direct radiation transmission is given by the equation:

The total absorbed radiation is given by the equation:

Sunshine

Cloud cover is a parameter used to calculate solar radiation (direct and diffuse). The data collected regarding daily sunshine duration helps estimate the intensity of solar radiation in a given area through modelling [63,64]. To calculate sunshine duration, essential data must be gathered, including global radiation (I0) values from meteorological stations located on either side of the modelled greenhouse, as well as diffuse radiation ) values, which are computed. Only those data points that satisfy both conditions are utilised:

[65] and [65,66]

From these data, the diffuse fraction (where ) is calculated by the following formula [65]:

3. Results

It is crucial to highlight that the materials and designs of the greenhouse roof differ significantly. Nevertheless, this paper focuses on presenting the results of the radiation calculations as a parallel development, rather than merely comparing them. To enhance clarity and depth, this section is structured into three distinct subsections.

The first subsection presents results that describe the characteristics of the area, with calculations independent of greenhouse-related parameters. However, these calculations are essential for subsequent analyses. This subsection includes global radiation (, total radiation on a horizontal surface ( and sunshine (diffuse fraction ). Additionally, information regarding prevailing temperatures (as recorded by the meteorological station) is provided to understand the area’s phenomena.

The second subsection focuses on results about greenhouses, but it does not consider their technical features. Here, total radiation on an inclined surface ( and total reflected radiation ( are presented.

The third and final subsection incorporates parameters related to the technical characteristics of greenhouses. It presents total transmitted radiation ( and total absorbed radiation (. The calculations of these radiations are closely tied to the properties of the covering material, such as the refractive index , from which the angle of refraction is determined. Additionally, the material’s attenuation coefficient and the thickness of the medium are used to calculate the radiation transmission . This transmission value is essential for determining both the parallel and perpendicular components needed to calculate the absorbed radiation.

To present the specific results, summary tables are used to group the results derived from solving the equations with MATLAB software, as well as graphs produced from statistical analysis using SPSS software.

It is important to clarify that the reported radiation levels mentioned in the greenhouses, as presented in the second and third subsections, have been calculated for all surfaces, including the perimeter and roof of the greenhouses. These calculations cover a full 24-h period. As such, the results include a significant number of negative values, since the data accounts for the hours from sunset to sunrise as well.

3.1. Presentation of Meteorological Data

The meteorological station near the modelled greenhouse provided 57,023 records from 1 May 2021, to 31 May 2022, with measurements taken hourly from 00:00 to 23:50 each day.

3.1.1. High Temperatures & Low Temperatures

This section outlines the changes in maximum and minimum temperatures, providing average values for these variations. Temperatures fluctuate seasonally, with average high temperatures notably increasing during the summer and decreasing during the winter. This seasonal variation directly influences heating and cooling thermal loads. During summer, the average maximum temperature typically exceeds 35 °C, while in winter, it falls below 10 °C. The average minimum temperature in winter typically reaches around 5 °C during the coldest months. The average low temperature exhibits a seasonal pattern similar to that of the high temperature. Hourly temperature distribution indicates a gradual increase from early morning, peaking between 14:00 and 16:00 (Supplementary Materials S2, Figure S1), followed by a decline after sunset. It is essential to consider local temperatures concerning greenhouse operations, as these temperatures significantly impact the greenhouse’s internal climate and dictate its heating and cooling requirements. This is particularly relevant during transitional seasons, where specific temperature values can directly influence the greenhouse’s heating and cooling needs, especially during extreme weather conditions.

3.1.2. Global Radiation (

The seasonality of temperatures is also reflected in solar radiation. During the summer months, the average solar radiation can exceed 800 , while in the winter, the values can drop to low or even zero. A gradual decline in the values is observed starting in October, with particularly low levels in February. This decline occurs because increased cloud cover and the sun’s lower angle during these months limit solar exposure. The hourly distribution of solar radiation shows peak values around noon, specifically from approximately 1:00 p.m. to 2:00 p.m., when solar intensity is at its highest (Supplementary Materials S2, Figure S2). Concerning greenhouses, understanding radiation values is crucial as they determine the need for artificial lighting, especially for crops that require a specific daily light dose.

3.1.3. Total Radiation on a Horizontal Surface (

The reference ratio for direct radiation on a horizontal surface is crucial for estimating the amount of sunshine in an area, as it is derived from direct radiation measurements. As mentioned in a previous section, direct radiation is considered sunshine when it exceeds . During the summer months, total radiation on the horizontal surface can reach an average maximum of 1000 , while in winter, it may drop below 100 . The daily distribution of radiation resembles that of , peaking at noon, which is important for estimating photosynthesis hours (Supplementary Materials S2, Figure S2). For greenhouse management, understanding these radiation values is essential as they provide key information for determining the photoperiod and total usable energy. This knowledge also aids in planning the installation of additional systems in the greenhouse, such as shading or supplementary lighting.

3.1.4. Direct Radiation on Horizontal Surface (

Direct radiation on a horizontal surface varies with the seasons. In summer, the solar radiation values Ibhor often exceed 500 , while in winter, they can drop below 100 . The hourly distribution of this radiation typically peaks when the sun is at its zenith, around 1:00 p.m. to 2:00 p.m. These values are important for greenhouse operations as they relate to photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) and the heat generated inside the greenhouse. A significant amount of direct radiation allows light to efficiently penetrate through transparent materials. The orientation and angle of the greenhouse roof play crucial roles in maximising this light entry. However, during winter, the low values mean less natural light is available, which often necessitates the use of supplementary lighting.

3.1.5. Sunshine (Diffuse Fraction )

The diffuse fraction defines conditions such as clear skies, partially cloudy days, and nighttime when there is no light (from sunset to sunrise). Values of close to 1 indicate overcast days, while values close to 0 reflect clear, sunny weather. During the summer, values typically range from 0.2 to 0.4, signifying high levels of direct sunlight and clear skies. In contrast, winter values range from 0.5 to 0.8, indicating a predominance of diffuse radiation due to increased cloud cover and lower solar angles (Supplementary Materials S2, Figure S3). Regarding greenhouses, high levels of diffuse radiation can be beneficial for achieving uniform light distribution within the plant canopy. However, these conditions do not support high light intensity , which can negatively affect crops that require significant daily light exposure. To address this, additional artificial lighting may be necessary, tailored to a daily activation schedule.

Conclusions

- The climatic conditions in the Psachna area of Evia (with coordinates ) are favourable for greenhouse crops due to the area’s abundant solar energy, particularly during the warmer months

- The low radiation and temperature levels during winter necessitate the implementation of supplementary heating and lighting systems

- The significant fluctuations in daily and seasonal temperatures and solar radiation underscore the need for effective control systems for greenhouse cultivation

- Direct radiation () plays a vital role in photosynthesis, particularly when greenhouse surfaces are clean and well-oriented

- Conversely, while diffuse light () aids in light penetration into the deeper layers of foliage, an excessive amount may indicate suboptimal sunlight conditions

3.2. Presentation of Radiation Results Not Related to the Technical Characteristics of the Covering Material

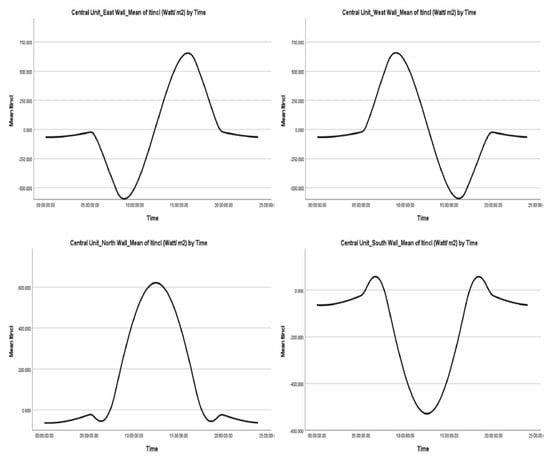

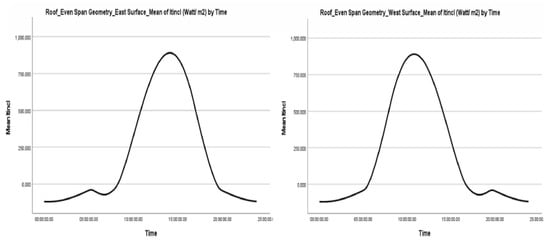

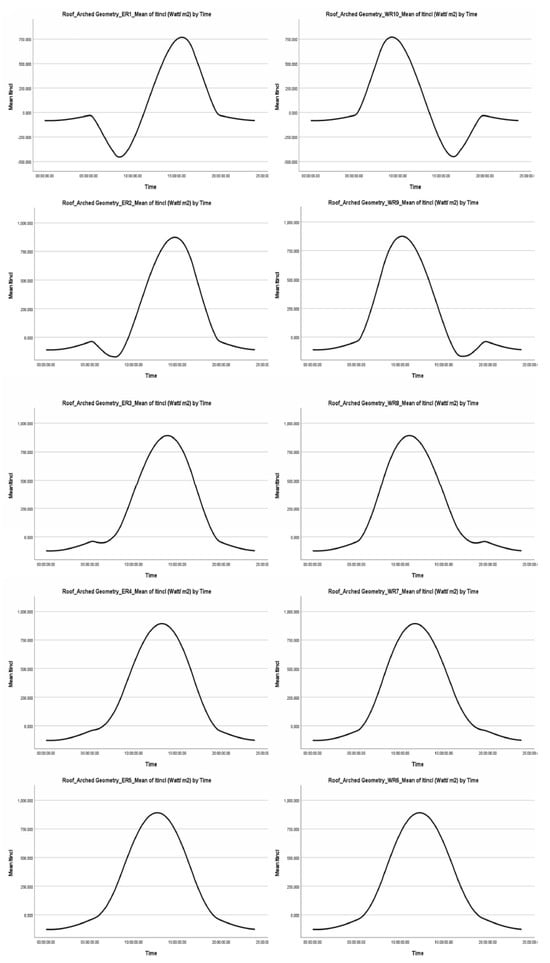

The total incident radiation on an inclined surface ( and the total reflected solar radiation ( are not related to the technical characteristics of the greenhouse covering material (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Tables S4 and S5 in Supplementary Materials S3 summarise the calculations of two types of radiation on the greenhouse’s walls and roofs for both Even Span and Modified Arched geometries. While wall values remain consistent across geometries, roof values differ. Additionally, the duration of negative radiation values is recorded, which is associated with periods of unfavourable incidence angles or low radiation intensity, primarily occurring at night. Sunshine is also taken into account, presented with a negative sign to facilitate evaluation in the subsequent section. The statistical analysis, conducted using SPSS, includes extreme values (maximum and minimum) for each case and the duration of their occurrence. The total radiation on an inclined surface ( is the sum of the direct, diffuse, and reflected components of solar radiation, with values that can be either positive or negative. The sign indicates the geometric relationship of the respective surface to the incident radiation. Negative values result from the algebraic sum of the incident and incoming radiation, along with long-wavelength radiation emitted from the greenhouse envelope. This typically occurs at night, when the incident radiation is zero, or during hours when the incident and incoming radiation are significantly low, falling short of the outgoing radiation. These conditions arise due to an unfavourable angle of incidence and reduced intensity of incident radiation caused by a large air mass. The total reflected radiation ( results from reflections from the ground or adjacent surfaces and behaves similarly to the total radiation on an inclined surface (. Specific months for certain radiation values are noted only when they do not pertain to the entire calendar year.

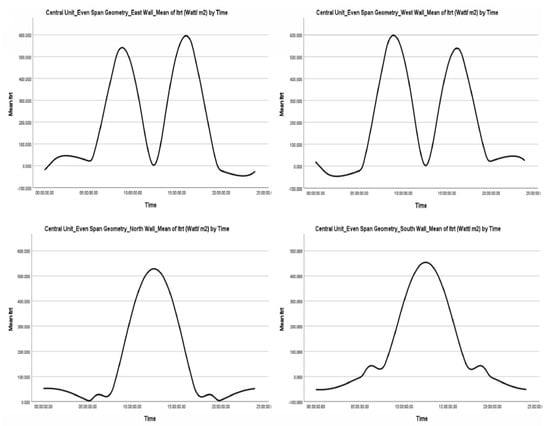

Figure 3.

Summary Graph of average values of total radiation on a tilted surface ( in relation to time. Central Unit.

Figure 4.

Summary Graph of average values of total radiation on a tilted surface ( in relation to time. Even Span Geometry Roof.

Figure 5.

Summary Graph of average values of total radiation on a tilted surface ( in relation to time. Modified Arched Geometry Roof.

3.3. Presentation of Radiation Results Related to the Technical Characteristics of the Covering Material

The total transmitted radiation ( and the total absorbed radiation ( are important factors related to the technical characteristics of the greenhouse covering material. Tables S6 and S7 in Supplementary Materials S3 provide the results of calculations for these two types of radiation on each wall and the roof of the greenhouse, considering both Even Span and Modified Arched geometries. The duration of negative radiation values is also documented. Sunshine is taken into account, and its values are presented with a negative sign, enabling evaluation in the following section. The statistical analysis, conducted using SPSS, includes extreme values (maximum and minimum) for each case, along with the time duration of their occurrence. Specific months in which particular radiation values occur are noted only for cases that do not affect the entire calendar year.

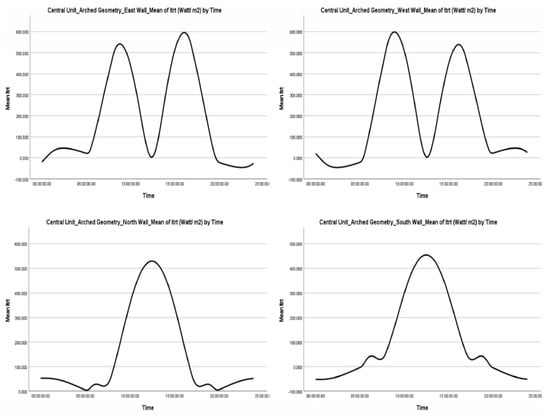

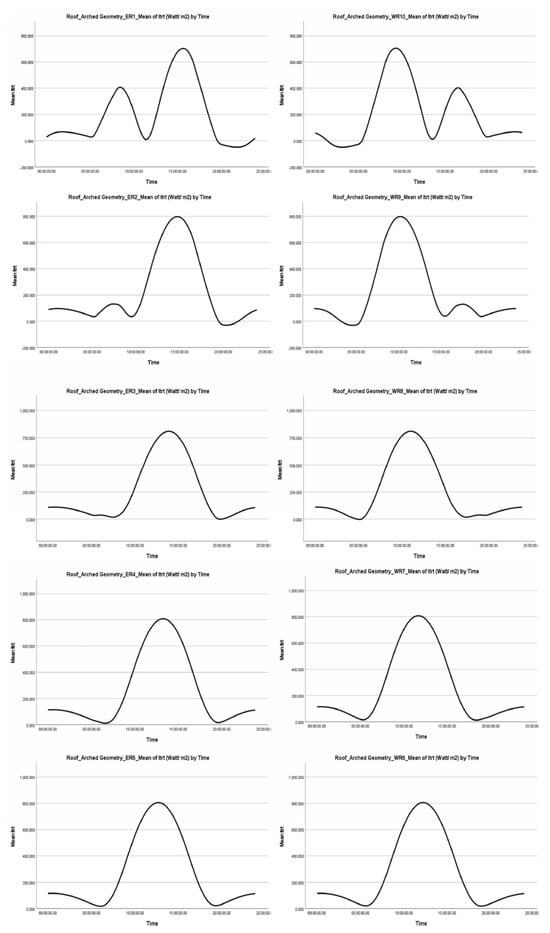

Summary figures present the average values of total transmitted radiation ( in relation to time for the Even Span Geometry Central Unit and Roof. (Figure 6 and Figure 7) and for the Modified Arched Geometry Central Unit and Roof (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 6.

Summary Graph of average values of total transmitted radiation ( in relation to time. Central Unit. Even Span Geometry.

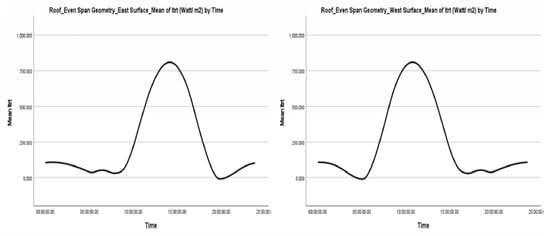

Figure 7.

Summary Graph of average values of total transmitted radiation ( in relation to time. Roof. Even Span Geometry.

Figure 8.

Summary Graph of average values of total transmitted radiation ( in relation to time. Central Unit. Modified Arched Geometry.

Figure 9.

Summary Graph of average values of total transmitted radiation ( in relation to time. Roof. Modified Arched Geometry.

4. Discussion

Clarifications

- This section analyses meteorological data by incorporating high and low temperatures for each hour of the day. Understanding these temperatures is crucial, as the outside temperature has a significant impact on the temperature inside the greenhouse throughout the entire 24-h period.

- In the previous section, the results of all radiation measurements for a full 24-h day were presented, highlighting the negative radiation values recorded from sunset to sunrise, during the hours when there is no sunlight. This section will focus specifically on the results for the hours between sunrise and sunset, which vary by month. The discussion will explain the occurrence of negative radiation values during daytime hours that receive sunlight.

- The calculation of radiation is followed by a separate paragraph addressing the duration of sunshine and the diffuse fraction. The commentary for these calculations focuses solely on the values obtained from sunrise to sunset, which also vary throughout the year.

- For the commentary on the radiation results, hours from sunset to sunrise are not considered. To ensure accuracy, each month’s sunset and sunrise times were evaluated separately. However, any values recorded as negative during the hours from sunrise to sunset are not eliminated. In most studies, negative values are typically excluded or set to zero in subsequent calculations and analyses. In this work, to provide a more accurate representation, these negative values are included and justified.

- Negative radiation values may indicate either a calculation error or necessitate an interpretation suggesting these values are likely related to shading or counter-radiation effects. After verifying the correctness of the calculation equations and confirming the lack of shading based on the selected location (evident through Google Maps), coupled with the radiation calculations based on solar angles, it is evident that the appearance of negative values is caused by the opposite radiation flow and the differences arising from a 90° inclination to the sun’s position. The models selected for this study to calculate solar radiation are based on solar angles.

- Some equations concerning the calculation of direct radiation rely on the angle of incidence . When , , resulting in negative values for direct radiation in these cases. A indicates that the sun is obscured behind the surface.

- Negative values may also occur in the absence of solar radiation, such as during cloudy skies.

- While negative values as a description of a physical quantity are not typically “normal,” they are mathematically legitimate and can be justified within the context of solar movement and the relationship between radiation and surface orientation.

4.1. Meteorological Data

4.1.1. Distribution of Temperatures Compared to Normal

The analysis compared the distribution of temperatures in the area to a normal distribution. The results indicated that high temperatures displayed positive skewness, with a mild deviation at the extremes due to some days experiencing higher temperatures than expected. In contrast, the distribution of low temperatures appeared more symmetrical, with some negative skewness caused by a few outliers in low temperature occurrences. However, there was no significant deviation from normality in this distribution. Both high and low temperatures demonstrate a continuity between them, both in terms of daily and seasonal patterns. The area presents a relatively stable temperature profile, showing only minor variations throughout the seasons and during the day. The statistical analysis of high temperatures does not reveal any extreme values, as most recorded temperatures fall within a moderate range. The frequency of high temperature values indicates that temperatures between 10 °C and 24 °C are the most commonly observed in the region, with an average high temperature of 18 °C and a standard error of 0.0364. A similar pattern is observed for low temperatures. The region exhibits a stable distribution of low temperatures, again without significant variations across seasons or daily cycles. No extreme low temperatures are noted. The frequency of low temperature values shows that temperatures ranging from 0.6 °C to 24 °C are commonly recorded in the region, with an average low temperature of 17 °C and a standard error of 0.0363. Overall, the findings suggest a stable temperature environment in the area, with no notable fluctuations during the specified time period for either high or low temperatures.

4.1.2. Temperature Picture of the Area

The geographical area of Psachna, located in the Municipality of Messapia-Dirfyos in the Prefecture of Evia, has the coordinates , with an altitude of 36 m. This region experiences a Mediterranean climate, characterised by hot summers and mild winters. The temperature fluctuations during the summer months highlight the need for cooling, while the relatively lower temperatures in winter indicate a lesser requirement for heating. Overall, the temperature distribution is quite typical, which positively influences the prediction and modelling of thermal loads.

Conclusions:

The temperature data emphasises the necessity for effective cooling during the summer months, especially in greenhouses, to prevent overheating. Conversely, the need for heating is relatively low. The nearly normal distributions, with only minimal deviations, offer confidence in the application of statistical tools.

4.1.3. Global Radiation (, Direct (, Diffuse ( and Total ( Radiation in a Horizontal Surface

Global radiation ( has an average value of approximately 330 , with a maximum recorded value of 1057 , during the period from sunrise to sunset. The standard deviation is 293.24 , indicating significant variation throughout the day. Direct radiation ( has an average of about 473 , with a maximum value of 1051 and a standard deviation of 318.71 . The high variation reflects considerable changes in intensity during the day, with a range of 554.51 . In contrast, diffuse radiation ( has a lower average of approximately 65.71 , and a small standard deviation of 29.54 , making it more stable and less variable. Total radiation closely follows Direct radiation, with clearly higher values than Diffuse radiation. The average Total radiation is 538.71 , with a maximum of 1159 and a standard deviation of 347.55 .

Conclusions:

The analysis indicated that total radiation is primarily influenced by direct radiation, while diffuse radiation plays a stabilising role in the overall energy behaviour. The daily variation follows the expected pattern, peaking at noon, due to the maximum solar altitude angle, and decreasing as the day progresses toward the west. The statistical correlation supports the significance of direct radiation, and any deviations from normal patterns can be attributed to fluctuations in solar intensity and weather conditions. Therefore, the results are deemed reliable and representative of the area’s actual conditions.

4.1.4. Correlation Between Radiation and Local Temperatures

The evolution of temperatures corresponds with changes in solar radiation, showing the highest values around noon and the lowest in the morning and evening. This alignment demonstrates the strong relationship between thermal conditions and solar energy in the area.

Conclusions:

Temperature variations are directly influenced by solar radiation, making them a crucial factor in the study of energy and the design of greenhouses.

4.1.5. Sunshine (Diffuse Fraction )

The reference to direct radiation on a horizontal surface provides a rough estimate of sunshine, derived from the intensity of this radiation [65]. Based on this estimate, it is evident that clear skies are more prevalent than cloudy ones in this area. Statistical analysis indicates that 86% of the time during the study period, the sky is clear. However, it is important to note that this analysis does not distinguish between intervals when there is no sunlight and it is dark. To address this, a further statistical analysis was conducted based on the results of the diffuse fraction. This analysis revealed that, during the study period and specifically between sunrise and sunset (which varies by month), only 3.3% of the time is cloudy. Additionally, there is a 27.1% occurrence of partially sunny skies, while the majority of the time, at 68.4%, the sky is clear.

4.2. Radiations Not Related to the Technical Characteristics of the Greenhouse Covering Material: Radiation on an Inclined Surface and Reflected Radiation (Supplementary Materials S3, Tables S8 and S9)

In this subsection, the radiation that is not related to the technical characteristics of the greenhouse covering material is analysed:

- This includes the direct, diffuse, and total radiations on an inclined surface, as well as the reflected radiation (ground, direct, diffuse, and total)

- The vertical side surfaces of the greenhouse (EW, NW, SW, WW) exhibit common results for these two types of radiation across various greenhouse geometries. This consistency arises because these radiations are independent of the covering material, while still sharing common characteristics in terms of orientation and geometry. However, this is not the case for the roof surfaces, which vary due to their distinct geometrical designs. Therefore, the roof surfaces of the greenhouse will be analysed separately for the Even Span and Modified Arched greenhouse configurations

- The roofs of various geometries are symmetrical

- Each roof, regardless of its geometry, consists of surfaces made from the same covering material. For instance, both the east and west-facing surfaces of the Even Span roof geometry are constructed from the same type of glass, while the east and west-facing surfaces of the Modified Arched roof geometry are made of polyethylene

- The average value of total radiation on an inclined surface ( is significantly influenced by the average value of direct radiation on an inclined surface (, which is typically higher than that of diffuse radiation on an inclined surface (. Similarly, for reflected radiation

- The diffuse radiation values on an inclined surface ( can be negative when the surface experiences a shaded sky with very low brightness or when it faces a brightly lit area of the sky near the horizon. This situation occurs when the viewing angle of the surface is directed toward vast regions of the sky with minimal diffuse radiation or during conditions of uneven brightness caused by cloud cover [67,68]

- The radiation reflected from the ground ( always presents positive values, as all surfaces are favoured by this type of radiation when sunlight is available

- The average value of direct and diffuse reflected radiation on an inclined surface is consistent with the average value of direct and diffuse radiation on that surface

- The average values of direct and diffuse reflected radiation align with the average values of direct and diffuse radiation on an inclined surface. This relationship is also consistent for the vertical surfaces corresponding to the same orientation. For the east and west-facing surfaces of the Even Span roof geometry, the average values of reflected radiation in terms of direct and diffuse radiation are consistent. The same holds true for the average value of ground-reflected radiation (

- When the angle of incidence . Therefore, any radiations calculated using the cosine of the specific angle may yield negative values in cases where , such as:

- ✓

- Equation (17) states , indicating that radiation hits the backside of the surface rather than directly illuminating it

- ✓

- Equation (21), the which means that can yield negative values when the sun does not illuminate the area directly in front of the surface, or when the geometry prevents the reflected radiation from reaching the surface

- Furthermore, Equation (21) shows that when either or . Practically:

- ✓

- According to Equation (8) , which means that . In this scenario, the zenith angle , meaning that the angle of elevation of the sun , and indicates that the sun is below the horizon

- ✓

- In conclusion, when the solar angle is small, resulting in a large zenith angle ( and or when the angle of incidence is leading to

- According to Duffie & Beckman [42], negative values of direct radiation on inclined surfaces can mathematically occur when the angle of incidence exceeds 90°. Since these values do not correspond to physically observable phenomena, the common practice in the literature is to treat them as zero. However, in this study, the decision is made to not disregard these values and instead investigate them further to assess their contribution to the computational results. This approach differentiates our methodology and adds an element of innovation to the study. The same consideration applies to reflected radiation. It is important to note that the negative values resulting from the mathematical model indicate heat outflow, which signifies the cooling of the space.

- Skewness measures the distribution of values in relation to the mean and is similar for both vertical surfaces of the greenhouse. The interpretations of skewness are as follows:

- ✓

- Skewness = 0 indicates a symmetric, normal distribution

- ✓

- Skewness > 0 indicates a positive skewness, characterised by many small values and few large values

- ✓

- Skewness < 0 indicates a negative skewness, characterized by many large values and few small values

- Kurtosis measures how extreme values are distributed and is also similar for both vertical surfaces of the greenhouse. The interpretations of kurtosis are as follows:

- ✓

- Kurtosis = 0 indicates a normal distribution (serving as a measure of comparison)

- ✓

- Kurtosis > 0 indicates the presence of many outliers

- ✓

- Kurtosis < 0 indicates the presence of fewer outliers

4.2.1. Vertical Greenhouse Surfaces with Even Span and Modified Arched Geometry

The relevant results indicate the following:

- When the average value of radiation on an inclined surface from sunrise to sunset is similar, this is primarily due to the sun’s movement from east to west. This observation holds for surfaces oriented towards the east and west. A similar phenomenon is observed in the reflected radiation between the vertical surfaces oriented to the east and west and those oriented to the north and south

- When the average value of direct radiation on a tilted surface ( is almost exactly symmetrical and inverse, it confirms that the two surfaces receive the same amount of direct radiation, albeit at opposite times of the day or year. This is valid for surfaces-oriented north and south

- The negative values that appear in the case of direct radiation on a tilted surface ( are since during the period when the sun is in the east, the western vertical surface of the greenhouse does not receive any direct radiation. The same principle applies in the opposite scenario. Additionally, the presence of a negative value for direct reflected radiation ( indicates that, based on the orientation of the surface (whether east, west, north, or south), the vertical geometry of the surfaces prevents direct exposure to sunlight. Consequently, when the value of direct radiation on an inclined surface is negative, the corresponding value of direct reflected radiation is also negative

- When the maximum and minimum values of direct radiation on an inclined surface ( show almost the same values between the two vertical surfaces, it underscores the dependence of direct radiation on solar movement. This applies to surface-oriented east and west

- Direct radiation on an inclined surface ( exhibits higher values on the vertical surface oriented to the north compared to that oriented to the south. The essential data is collected from these observations:

- ✓

- Both surfaces have the same slope, which means they are perpendicular to each other with an angle of

- ✓

- The average value of diffuse radiation is identical for both surfaces

- ✓

- There is no shading from the southern surface

- ✓

- The orientation is correctly set, with the northern surface at and the southern surface at

- ✓

- Only the radiation from sunrise to sunset has been considered for each month separately

- ✓

- The direct radiation on an inclined surface ( takes the angle of incidence into account. This means that a smaller angle of incidence results in a higher cosine of the angle , and consequently a higher

- ✓

- Negative values are preserved in both the radiation and cosθ calculations, indicating that the sun is facing the opposite side

- ✓

- Absolute values are not used for which is why negative results appear in the calculations

- Therefore, although the appearance of higher direct radiation values on an inclined surface on the vertical surface with a north orientation compared to that with a south orientation is not expected, it could be justified (taking into account the data already presented):

- ✓

- The smaller angle of incidence results in a higher , which in turn increases . However, there are specific times, such as early morning and late afternoon during spring and autumn, when the sun’s azimuth creates more favorable angles with the vertical north-facing sides. Meanwhile, vertical south-facing surfaces receive more direct radiation on inclined surfaces when is smaller, indicating a larger angle of incidence. For instance, on 21 October, the northeast sunrise benefits the north-facing surface significantly more than the south-facing surface

- ✓

- The latitude of the study area is linked to a particularly low solar path during the winter months, causing the vertical surfaces-oriented east, south, and north to receive solar radiation indirectly or through reflections from the environment, even at low angles

- ✓

- The northern vertical surface tends to receive more radiation during the early morning and late afternoon

- ✓

- However, around midday, when the sun is high in the south, the south-facing surface is favoured. Yet, during the hours near sunrise and sunset, the north-facing surface performs better due to a more optimal angle of incidence between the sun and the vertical surface

- ✓

- Additionally, the transparent covering material allows solar radiation to enter through surfaces of any orientation. This means that the south-facing vertical surface not only permits solar radiation to pass through but also allows it to reflect onto the north-facing surface

- However, for a more precise justification of the higher values presented by direct radiation on a tilted surface However, for a more precise justification of the higher values presented by direct radiation on an inclined surface ( on the vertical surface of the north and south orientation, a statistical analysis was performed, the results of which showed that:

- ✓

- The average incidence angle in the northern hemisphere is . The minimum incidence angle is . These results indicate the presence of direct radiation

- ✓

- The average incidence angle in the southern hemisphere is , leading to , while the minimum angle is , resulting in . This data shows a lack of direct radiation and only minimal instances of positive radiation

- ✓

- Therefore, the larger average value for the northern-facing surfaces is not a calculation error; rather, it is a consequence of the geometric relationship between the sun’s position and the orientation of the wall, particularly during the early morning and late afternoon hours

- In general, the radiation levels on an inclined surface for all four vertical surfaces of the greenhouse exhibit a symmetrical normal distribution. The diffuse radiation on an inclined surface ( shows slightly higher values for all four surfaces, while the direct radiation on an inclined surface ( shows increased values for the east and west-oriented surfaces. The reflected radiation displays a similar pattern on surfaces with corresponding orientations

- Kurtosis across all four orientations, as well as for all types of radiation, indicates a lack of extreme values

4.2.2. Even Span and Modified Arched Greenhouse Roof Surfaces

The relevant results indicate the following:

- The east and west-facing surfaces of the Even Span roof receive similar average values of direct, indirect, and total radiation, as well as radiation on an inclined surface that is reflected, transmitted, and absorbed by the material. The differences are infinitesimal for the duration of the study and throughout the day, from sunrise to sunset, varying slightly depending on the month. Similarly, the corresponding surfaces of the Modified Arched roof geometry (ER1-WR10, ER2-WR9, ER3-WR8, ER4-WR7, ER5-WR6) show comparable results

- This is primarily due to the symmetrical design of the roof, where the east and west-facing surfaces are geometrically identical, sharing the same inclination angle, surface area, and material. The sun’s path, as it moves from east to west, plays a crucial role; however, the average values remain unchanged due to this symmetry. It’s important to note that this is a roof, not a vertical surface

- On the roof, sunlight exposure is symmetrically equivalent, with morning sunlight hitting the eastern surface and afternoon light illuminating the western surface. This symmetry results in an equivalent solar energy load for both surfaces around noon. Therefore, on average, the surfaces receive an equivalent solar energy load

- Direct radiation on an inclined surface ( shows negative values on the east-facing roof surface during the morning hours and on the west-facing roof surface after noon. Justification:

- ✓

- The large angle of incidence results in negative values for and . However, this does not imply negative solar energy or the absence of solar radiation. Instead, it indicates that the specific surface is oriented away from the sun at that time

- ✓

- In the early morning hours, the sun’s low trajectory justifies the negative values on east-facing roof surfaces. Similarly, as the sun approaches the west during the late afternoon, the low angle also accounts for the negative values on west-facing roof surfaces. To summarise, the sun is positioned lower than the angle of the inclined roof surface

- The diffuse radiation on an inclined surface ( presents values with a negative sign only in the case of the Modified Arched roof geometry. Justification:

- ✓

- The issues mainly arise from negative minimum values of the solar angle

- ✓

- The structure’s complex geometry contributes to these problems, as the roof is composed of multiple narrow and inclined sections that create curvature between them

- ✓

- During the early morning or near sunset, the overlapping geometry of these roof sections causes shading between the surfaces

- ✓

- The limited sky view factor from these surfaces is crucial for receiving diffuse radiation

- The presence of direct reflected radiation ( values with a negative sign is justified by:

- ✓

- In the early morning hours, when the sun is low on the horizon, direct reflected radiation often does not reach the ground in front of greenhouse roof surfaces that are oriented eastward. This is due to shading caused by the geometry of the greenhouse itself

- ✓

- Similarly, during the hours near sunset, direct reflected radiation often fails to reach the ground in front of greenhouse roof surfaces-oriented westward, again due to shading by the greenhouse’s geometry

- ✓

- In these cases, the ground does not serve as an active reflecting surface for direct radiation. As a result, the calculations yield a numerical value with a negative sign to indicate this phenomenon

- ✓

- It is important to note that this negative value does not represent a physical quantity; instead, it serves as a computational indication of the absence of radiative contribution due to geometric incompatibilities in the orientation and exposure of the surfaces

- In general, the radiation symmetry on the inclined east and west roof surfaces of the greenhouse yields identical values. The greenhouse roof exhibits a symmetrical normal distribution. Both the diffuse radiation on the inclined surface ( and the diffuse reflected radiation ( show a similar symmetrical distribution, with a tendency for higher values to appear more frequently than lower values

- The kurtosis displays the same values for both the east and west-facing surfaces. In all scenarios concerning the specific types of radiation, the greenhouse roof demonstrates a lack of extreme values

4.3. Radiations Related to the Technical Characteristics of the Covering Material (Supplementary Materials S3, Tables S10 and S11)

In this subsection, the results of radiation related to the technical characteristics of the greenhouse covering material are analysed. The equations used for radiation calculations include parameters such as the refractive index and the attenuation coefficient of the material. Specifically:

- The transmitted radiation and absorbed radiation by the material (direct, diffuse, and total radiation)

- The average values for direct, diffuse, and total transmitted radiation are comparable for the vertical side surfaces of the greenhouse (EW, NW, SW, WW) across the two different geometries. This observation can be attributed to the uniform geometry of the central unit, the vertical slope of the surfaces, and the transparent covering material. However, this trend does not hold for the roof surfaces, as their geometry and slope differ

- Despite the slight difference in refractive indices between glass and polyethylene , the results are unlikely to vary significantly

- The roofs of different geometries are both symmetrical

- Each roof comprises surfaces made from the same covering material. For instance, the east and west-facing surfaces of the Even Span roof are both constructed from glass, while those of the Modified Arched roof geometry are made of polyethylene

- The direct transmitted radiation ( in all cases does not display negative values

- The diffuse transmitted radiation ( presents negative values across all surfaces in both geometries. This requires further justification:

- ✓

- The calculation depends on the incident diffuse radiation on the external surface

- ✓

- According to Formula (34), ( is the transmissivity) and

- ✓

- According to Formula (32), . The perpendicular and parallel components are positive values, but when their values exceed unity, the transmissivity becomes negative. This means that at extreme angles of incidence, the ratios and may differ numerically

- ✓

- From Formulas (30) and (31), it is evident that the parallel and perpendicular components depend on both the angle of incidence and the angle of refraction, and these components are always positive

- ✓

- It should be noted that the angle of refraction is always constrained within the limits . However, there are instances when

- ✓

- During early morning hours or under conditions of very low total radiation, the incoming diffuse radiation may be minimal or even zero on certain surfaces

- ✓

- In such cases, if the numerical value of the transmitted energy falls below the theoretical minimum limit, the recorded value may turn negative

- The absorbed radiation (direct, diffuse, and total) either does not exhibit negative values or shows values that are extremely close to zero, making them nearly imperceptible

- Negative average values of total absorbed radiation are observed only in cases where average values of total transmitted radiation also exhibit negative values

- The absorptivity of polyethylene coating material is lower than that of glass

- Generally, the radiation symmetry on an inclined surface of the central unit’s vertical surfaces, as well as on the Even Span and modified roof geometry of the greenhouse, displays a symmetrical normal distribution for both transmitted and absorbed radiation (direct, diffuse, and total) with values extremely close to zero (either negative or positive) and without obvious deviations

- The kurtosis shows identical values for the corresponding surfaces and specific radiations, indicating a lack of extreme values

Conclusions:

- The average value of transmitted radiation (direct, diffuse, and total) shows similar levels on the vertical side surfaces (EW, NW, SW, WW) for both geometries. This similarity is due to the consistent slope of the surfaces, the symmetrical geometry of the central unit, and the use of transparent materials. In contrast, differences are observed on the roof surfaces, which arise from the varying slopes and geometries of the Even Span and Modified Arched structures.

- Although polyethylene and glass have very close refractive index values ( for polyethylene and for glass), the different geometries can influence the final calculations of transmitted energy. Specifically, the direct transmitted radiation yields only positive values, while the diffuse transmitted radiation exhibits negative values across all surfaces for both geometries.

- The transmittance is calculated from Equation (32), which incorporates ratios that depend on the parallel and perpendicular components of reflectivity. When these ratios deviate, particularly at large angles of incidence , the value of can become negative, resulting in negative radiation values. This occurrence is numerical and relates either to extreme geometric conditions or to low intensity of incoming radiation (such as early morning or late afternoon).

- The absorbed radiation, both diffuse and total, does not present significant negative values, aside from negligible instances where transmitted radiation is also recorded as negative. This is because absorbed radiation is calculated as the difference between incident and transmitted radiation.

- Notably, polyethylene has a lower absorptivity than glass, which is reflected in the reduced absorbed radiation values on the surfaces of the Modified Arched geometry.

5. Conclusions