Abstract

This paper presents a closed-loop price–dispatch framework for park-scale virtual power plants (VPPs) with coupled electric–thermal processes under high penetrations of photovoltaics (PVs) and electric vehicles (EVs). The outer layer clears time-varying prices for operator electricity, operator heat, and user feed-in using an improved particle swarm optimizer with adaptive coefficients and velocity clamping. Given these prices, the inner layer executes a lightweight linear source decomposition with feasibility projection that enforces transformer limits, combined heat-and-power (CHP) and boiler constraints, ramping, energy balances, and EV state-of-charge requirements. PV uncertainty is represented by a small set of scenarios and a conditional value-at-risk (CVaR) term augments the welfare objective to control tail risk. On a typical winter day case, the coordinated setting aligns EV charging with solar hours, reduces evening grid imports, and improves a social welfare proxy while maintaining interpretable price signals. Measured outcomes include 99.17% PV utilization (95.14% self-consumption and 4.03% routed to EV charging) and a reduction in EV charging cost from CNY 304.18 to CNY 249.87 (−17.9%) compared with an all-from-operator benchmark; all transformer, CHP/boiler, and EV constraints are satisfied. The price loop converges within several dozen iterations without oscillation. Sensitivity studies show that increasing risk weight lowers CVaR with modest welfare trade-offs, while wider price bounds and higher EV availability raise welfare until physical limits bind. The results demonstrate an effective, interpretable, and reproducible pathway to integrate market signals with engineering constraints in park VPP operations.

1. Introduction

Urban districts and industrial parks are increasingly supplied by heterogeneous distributed energy resources (DERs) such as rooftop photovoltaics (PVs), combined heat-and-power (CHP) units, electric boilers and heat pumps, and growing fleets of electric-vehicle (EV) chargers [1,2,3,4]. Aggregating these assets as a virtual power plant (VPP) can improve local self-balancing and reduce system costs, but operational coordination remains challenging [5,6,7,8]. First, the electrical and thermal subsystems are tightly coupled through co-generation and power-to-heat substitutions, so naïve electricity-only scheduling can induce thermal infeasibilities or large fuel penalties [4,5]. Specifically, the rigid coupling between heat and electricity in CHP units often forces operators to curtail renewable generation to meet heat loads during off-peak hours [9,10]. Second, behind-the-meter PV behaves as a prosumer resource whose surplus depends on uncertain load and solar conditions and whose economic participation depends on retail prices and subsidies [11,12,13,14,15]. Third, EV charging is both flexible and stochastic: unmanaged arrivals create new peaks that coincide with high retail tariffs, whereas coordinated charging must respect transformer limits, CHP ramps, charger ratings, and state-of-charge (SOC) constraints [16]. Furthermore, traditional open-loop pricing schemes fail to account for the collective impact of price-responsive users. When all EVs respond to a low-price signal simultaneously, it can cause a ‘rebound peak’ that violates transformer capacity limits, a phenomenon not adequately addressed in static TOU schemes [17]. Finally, risk exposure under variable PV and time-of-use (TOU) prices motivates operators to manage not only expected costs, but also tail events [18,19].

Existing coordination methods fall into two categories. Centralized dispatch [13] ensures feasibility but ignores prosumer incentives. Bi-level optimization [20,21], internalizes prices using KKT conditions, but requires the lower-level problem to be strictly convex, making it difficult to handle complex logic like the ‘minimum tariff’ rule. Other works [22] employ robust optimization but often neglect the thermal coupling constraints inherent in CHP systems. Nevertheless, when the pricing layer is designed or updated without being tightly constrained by the underlying engineering feasibility region, the resulting price–quantity iteration may become weakly coupled and exhibit oscillations or infeasible intermediate solutions, particularly under electric–thermal coupling, ramping constraints, and high PV/EV penetration with uncertainty [11,23,24,25,26,27,28]. In addition, clearing electricity and heat independently obscures CHP’s joint operating region and may misprice cross-carrier pathways, thereby degrading both dispatch efficiency and economic signals [29]. Moreover, operational uncertainty is often addressed by heuristic reserve margins rather than by an explicit coherent risk measure such as CVaR, making the welfare–robustness trade-off opaque and difficult to tune systematically [18,19,30,31]. Distributed coordination has also been studied using decomposition methods such as ADMM [32], yet practical deployment may require iterative message passing and careful convergence tuning and may face information and privacy challenges in transactive settings [26]. Recent works therefore combine transactive mechanisms with (distributionally) robust formulations in decentralized solvers to improve stability and out-of-sample performance under renewable uncertainty [33,34]. To clearly position the contribution of this study, Table 1 summarizes a comparative review of representative works against the proposed closed-loop framework in terms of dispatch mechanism, coupling handling, and risk management. Practically, compared to KKT-based bi-level formulations, this projection-based approach avoids the need for strict convexity and complementarity constraints, thereby ensuring robust numerical convergence even when handling non-smooth logic like the ‘minimum tariff’ rule.

Table 1.

Compares proposed framework with representative recent studies.

To address these gaps, this paper proposes a closed-loop price–dispatch framework for park VPPs with electric–thermal coupling and high PV/EV penetration. The outer layer clears time-varying prices for three channels—operator electricity, operator heat, and user feed-in—using an improved particle swarm optimizer (PSO) with adaptive coefficients and velocity clamping. The inner layer accepts those prices and executes a linear source decomposition with feasibility projection, which enforces transformer capacity, CHP and boiler limits, ramping, balances, and EV SOC constraints. Uncertainty in PV is represented by a small set of representative scenarios with probabilities and risk is handled via a conditional value-at-risk (CVaR) term that augments the welfare objective. Closing the loop ensures that price movements are economically interpretable and immediately reflected in feasible physical schedules, while the linear structure of the inner layer keeps the computation lightweight. Specifically, unlike open-loop market models that may produce prices incompatible with physical constraints (leading to oscillations), this closed-loop mechanism guarantees that every price signal is validated against the physical feasibility layer. This ensures that the market equilibrium is strictly executable by the underlying assets (CHP, boiler, and transformers).

The contributions are threefold. First, we develop a joint pricing mechanism for the electric and thermal channels that explicitly respects CHP co-generation and power-to-heat substitutions; this removes common inconsistencies between the independent price setting and coupled dispatch. Second, we introduce a convex, projection-based inner dispatcher that guarantees feasibility under device and network limits while maintaining transparency of the physical flows (grid imports, CHP output, boiler back-up, EV charging sources). Third, we embed a CVaR-based risk term into the welfare objective so that operators can tune the trade-off between expected performance and tail robustness; the risk-aware outer loop remains stable due to the explicit physical feedback from the inner layer.

The approach is evaluated on a typical winter day in a park VPP that includes CHP, a gas boiler, a distribution transformer, rooftop PV arrays, and an EV charging aggregator. Results show that the coordinated setting naturally aligns EV charging with solar hours, reduces evening grid imports, and improves a welfare proxy while keeping operator revenues and user costs within realistic bounds. Sensitivity analyses further quantify the effects of risk aversion, price bounds, and EV availability on welfare, price variability, and PV absorption.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 details the system architecture and optimization objectives. Section 3 formulates the device, balance, and market models, together with the risk representation. Section 4 presents the solution methodology, including the improved PSO price layer and the feasibility-projected inner dispatcher. Section 5 reports case studies and sensitivity analyses. Section 6 summarizes the relevant content.

2. System Framework and Optimization Goals

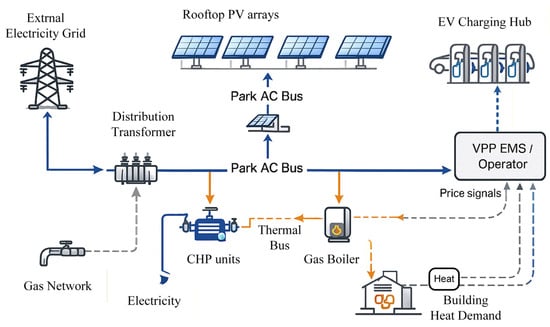

This study considers a park-scale virtual power plant (VPP) that aggregates combined heat-and-power (CHP) units, gas boilers (GB), a distribution transformer, rooftop photovoltaic (PV) arrays, and electric-vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure, coupled to the external electricity and gas networks, as shown in Figure 1. Three market actors interact over a scheduling horizon: the VPP operator (opr), PV prosumer users (user), and the EV charging aggregator (agg). The information layer comprises each actor’s Energy Management System (EMS) and a park Energy Trade Center (ETC) that collects bids/asks, performs provisional clearing, and dispatches setpoints.

Figure 1.

Park-scale VPP architecture.

The scheduling horizon is discretized as

with step Δt (15 min in the case study). The power variable is denoted as

and the energy variable is denoted as

. The main price and power variables are as follows:

The actor-facing prices are

(electricity/heat selling prices of the operator),

(user’s feed-in price),

(EV charging tariff),

(external time-of-use electricity tariff),

(gas price), and

(Solar energy subsidy).

The key power variables include

(operator’s electricity/heat sales),

(grid import),

(CHP outputs), and

(boiler heat).

The user and aggregated power variables include

(photovoltaic power generation),

(personal use),

(sale outside),

(purchase electricity/heat from the operator),

(aggregated EV charging),

(the charging power purchased, respectively, from the operator side and the user side). The EV state is summarized by

with a charging efficiency

and an aggregated equivalent battery capacity

.

Prices are bounded by feasible bid/ask intervals:

The charging settlement price for aggregators follows the selection rule of ‘lower price takes precedence’, as shown in Equation (2).

The net revenue of the operator in time slot t is defined as:

where

represents gas consumption and

represents the operation and maintenance costs. The net revenue at the user side is

Without considering the service fee, the net revenue of the aggregator and the negative power purchase expenditure are as follows:

The social welfare target is the sum of the net benefits of the three parties, as shown in the following formula:

where

integrates the quotations and output decisions. The objective function

represents the aggregated net social surplus of the park, accounting for the operator’s profit, users’ net revenue (including subsidies), and the aggregator’s procurement savings. This objective needs to be solved under constraints such as electricity and heat balance, equipment capacity and ramp rate, EV availability and SOC, and external prices and quotation boundaries. It should be noted that Equation (6) is a purely economic metric. Although environmental externalities (e.g., carbon emissions) are not explicitly formulated as penalty terms (as explored in carbon-aware frameworks [9,14]), the inclusion of the PV subsidy

indirectly promotes environmental benefits by incentivizing the maximization of renewable self-consumption.

3. System Modeling

To quantify the impact of EVs and distributed PV resources on distribution network operation, a park-scale distribution network power-flow model is first established. For radial distribution networks, the branch power-flow formulation offers high computational accuracy; the nodal voltage relationships and branch active and reactive power transfers are represented using this model. The proposed network model focuses on active power balance for day-ahead economic scheduling. Voltage limits and reactive power support are assumed to be managed by lower-level local controllers (e.g., inverter volt-var control) and are not explicitly modeled in this timeframe.

For an individual EV, once it arrives at a charging facility, its required net charging energy is jointly determined by the initial SOC at connection, the user-specified SOC target interval at departure, and the battery capacity, and is further constrained by the available connection duration and the admissible charging/discharging power range. Within each scheduling interval, the EV is assumed to occupy exactly one of three mutually exclusive states: charging, discharging, or idle (with charging/discharging power equal to 0 kW). According to their willingness to participate in the scheduling process, EV users are classified into three categories: controlled-charging users, vehicle-to-grid (V2G) users, and non-participating users.

For both controlled-charging and V2G users, the EV can be scheduled to charge in any time slot between the arrival time and the expected departure time, subject to the requirement that the SOC at the expected departure reaches the user-specified target. The control objective for these users is to minimize their charging cost. In addition, for V2G users, the EV is allowed to discharge power back to the grid over one contiguous time interval between arrival and expected departure, thereby shaving the daily peak load and improving the economic efficiency of the distribution system’s operation. For non-participating users, the EV starts charging immediately at a pre-agreed constant power upon connection and continues until the battery is fully charged or the vehicle leaves. Provided that the connection duration is sufficiently long, the actual net charged energy for each user category is assumed to coincide with the corresponding required net charging energy. It is noted that this assumption holds primarily for workplace or residential scenarios with long dwell times, where users connect for durations sufficient to meet the target SOC. In cases of unexpected early departure, real-time adjustment mechanisms would be required, which are beyond the scope of this day-ahead scheduling framework.

The power-side and heat-side balances for the operator are as follows:

Equation (8) adopts a simplified single-node thermal bus model. This is valid for compact park-scale systems where thermal transmission delays and pipe losses are negligible relative to the 15 min scheduling step. For larger district heating networks, explicit hydraulic constraints would be required. The power distribution of PV electricity at the user end is as follows:

The power supply configuration for aggregated charging is as follows:

In this park-scale aggregation model, the internal network is treated as a radial microgrid. The primary network constraint is the capacity limit of the Point of Common Coupling (PCC) distribution transformer. The capacity and non-negativity constraints are as follows:

The climbing slope constraint is as follows:

CHP Thermal Coupling: To maintain the convexity of the inner-layer sub-problem and ensure rapid convergence, a polyhedral approximation is applied to the nonlinear feasible operation region of the CHP unit [29]. The linearization approximation using thermoelectric ratio or equivalent energy constraints is as follows:

The operation and maintenance costs are as follows:

The aggregated charging power is constrained by the sum of availability and the rated power of the charging station as follows:

The evolution of the aggregated SOC is as follows:

Then, we impose the following target constraints on the departure time period:

The price boundaries and external conditions are as follows:

The revenue from the user-side PV is as follows:

The user’s expenditure on purchasing energy from the operator is as follows:

The purchase costs and gas costs of the operator are as follows:

The revenue from energy sales by the operator is as follows:

All of the power, energy, price, and SOC variables meet the following conditions:

Based on the comprehensive objective and the feasible region, the integrated optimization problem is as follows:

4. Solution Method

The method couples prices and physical dispatch in a closed loop. The outer layer optimizes the time trajectory of three price signals, namely operator electricity and heat-selling prices and the user feed-in price. The inner layer, given any price vector, carries out provisional clearing and solves a feasible electro-thermal and EV charging dispatch that returns power trajectories and social welfare. Let the horizon be discretized as

with step

. Stack prices as follows:

where

is the box defined by price bounds. For any

, the inner evaluation solves a linear program that enforces electric and thermal balances, device capacities and ramps, EV availability and SOC dynamics, external time-of-use electricity tariff and gas price, and the linear source decomposition of EV charging. The linear decomposition replaces a non-smooth minimum tariff with two charging energy streams from the operator and the user, which preserves linearity while allowing the optimizer to prefer the cheaper source. Economically, this decomposition is a linear proxy for the ‘if-else’ logic of choosing the cheapest supplier. Since the objective function seeks to minimize costs (maximize welfare), the linear program effectively forces the variable corresponding to the higher price to zero, preventing arbitrage. Physical consistency is guaranteed by Equation (10), ensuring that the sum of decomposed flows exactly matches the battery’s physical intake, eliminating any risk of double-counting energy.

In this park-scale context, PV generation is identified as the dominant source of stochastic volatility. While EV arrival times are also uncertain, they are handled via the aggregator’s time-varying availability constraints

rather than probabilistic scenarios. Extending the CVaR term to include load and EV uncertainties would exponentially increase the scenario dimensionality and computation time, which is left for future work. PV uncertainty is represented by a reduced scenario set

with probabilities

. For tail risk control, a conditional value-at-risk at confidence

is introduced via the standard linearization:

where

is the stage payoff under scenario

,

is the auxiliary threshold, and

are excess losses. A risk weight

blends expected performance and tail robustness. The risk-adjusted fitness for a price trajectory is as follows:

Risk neutrality is recovered at

. A larger

places greater emphasis on adverse scenarios.

The Improved PSO is selected for the outer layer for two reasons. First, the inner feasibility projection creates a non-differentiable landscape that precludes gradient-based bi-level solvers. Second, compared to discrete metaheuristics like Genetic Algorithms, PSO is naturally advantageous for continuous price variables. Its particle memory mechanism allows it to navigate the non-convexity introduced by the ‘minimum-tariff’ logic more robustly than standard descent methods. For particle

at iteration

with position

and velocity

, the update is as follows:

where

,

is the best position of particle

,

is the iteration best, and

is the projection onto the price box. The inertia weight follows exponential annealing and is as follows:

The learning factors are linearly annealed is as follows:

where

and

. Componentwise velocity clamping is proportional to the span of each price dimension, out-of-range components undergo a single mirror reflection followed by clipping. The clamping scale of 0.2 was empirically selected to prevent particles from oscillating violently across price boundaries, ensuring stable convergence. Similarly, the inertia weight annealing ( = 0.9 to

= 0.4) balances global exploration in early iterations with local exploitation in later stages. Diversity is maintained by gradually expanding the topology from ring to fully connected when the global best stagnates and by a small zero mean Gaussian perturbation on price coordinates for non-improving particles, with a variance that decays with

.

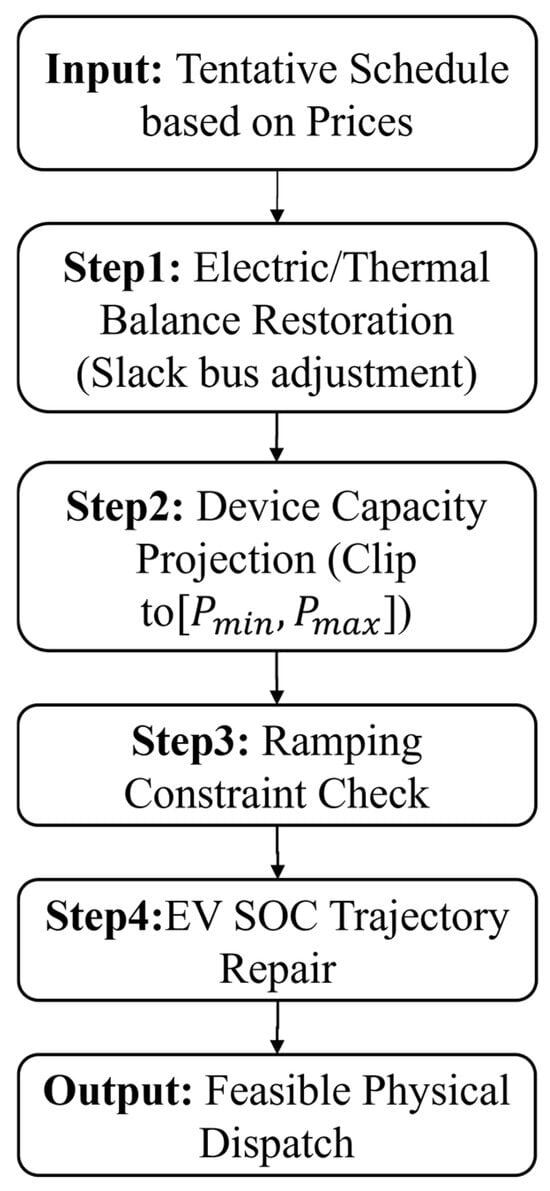

To protect feasibility, infeasible inner solutions are repaired by a grouped projection that proceeds sequentially, as illustrated in Figure 2: it first restores the global power balance by compensating any mismatch through adjusting the grid import PT(t) or boiler output; it then projects the updated variables onto device capacity limits (Equation (10)) by clamping PPP to [,

] and passing any residual to the next flexible resource; finally, it enforces ramping constraints (Equations (12)–(14)) by smoothing the trajectory via a forward–backward sweep correction, followed by repairing EV charging power and SOC when necessary. An adaptive quadratic penalty augment

with iteration-growing coefficients, and feasibility-precedence rules are applied when comparing candidates. If an LP solver is available, the inner problem returns an exact optimum; otherwise, the grouped projection provides a feasible approximation, whose welfare is used as the fitness. The stopping criteria combine a maximum-iteration cap, a small relative-improvement window for the global best, and a threshold on total constraint violation. The per-iteration computational cost scales with the number of representative scenarios and time steps and grows approximately linearly with

in projection-only mode.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the feasibility-prediction process.

5. Results

The test system is a park virtual power plant over a typical winter day with

. It includes one combined heat-and-power unit, one gas boiler, one distribution transformer, five rooftop photovoltaic arrays, and forty EV charging points, coupled to the external electricity and gas networks. The device and economic parameters are as follows. The CHP has a

and a

, with an electrical efficiency of

, a thermal efficiency of

, a heat-to-power ratio of

, a ramp of

, and an O&M cost of CNY

. The boiler has a

, an efficiency of

, a ramp of

, and an O&M cost of CNY

. The transformer has a

and an O&M cost of CNY

. The user-side PV has a subsidy cost of CNY

and an O&M cost of CNY

. The EV fleet charges with an efficiency of

, has an aggregated equivalent battery capacity of about

and

per charger. The price bounds are CNY

to

for operator electricity, CNY

to

for operator heat, and CNY

to

for user feed-in. The gas price is CNY

. The grid time-of-use tariff

follows the utility day schedule. Photovoltaic scenarios are generated from historical profiles and reduced to a small representative set with probabilities. PV uncertainty is represented by a reduced set of representative scenarios extracted from historical PV profiles to capture distinct regimes such as clear-sky peak, overcast low-output, and fast-variation mid-day ramps, while keeping the inner evaluation computationally tractable. Risk parameters use

, a standard industry benchmark for tail risk management focusing on the worst 10% of outcomes, and

in the base run and are varied in sensitivity analysis.

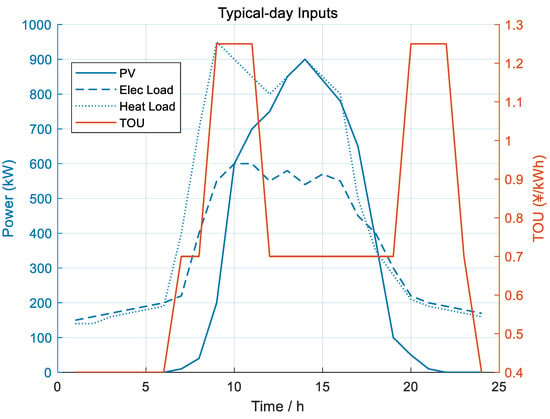

Figure 3 summarizes the typical-day inputs. PV peaks around noon, the electric load exhibits a mid-day plateau and evening shoulder, and the heat demand is high in the morning and late afternoon. The overlaid TOU curve explains why the optimizer tends to avoid purchases during high-price windows and shift EV absorption toward solar hours.

Figure 3.

Typical-day inputs and TOU tariff: PV output, electric load, heat demand, and TOU price.

Three operational settings are considered. The coordinated setting uses the closed-loop price–dispatch system with the improved particle swarm and a linear program or grouped projection in the inner layer. The unordered EV setting follows an exogenous arrival and immediate charging profile without price response. The all-from-operator setting forces the EV aggregator to purchase all energy from the operator without user PV sourcing. The swarm size is 40 with 50 iterations; inertia and learning factors anneal automatically and the velocity clamp scale is 0.2.

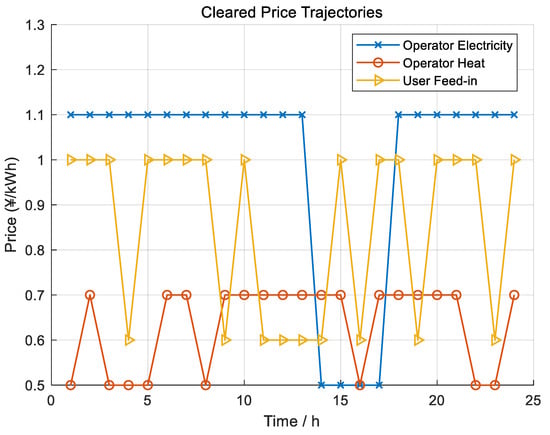

Figure 4 gives the cleared trajectories in the coordinated setting, respecting the price boxes. Electricity prices remain higher during evening hours to discourage imports, heat prices relax around noon when CHP co-produces heat, and the user feed-in price varies to balance PV surplus versus local absorption via EVs. Notably, the user feed-in price dips during periods of abundant PV (e.g., 11:00–14:00). This serves as an economic signal to reflect the reduced marginal value of surplus energy and to incentivize the aggregator to shift EV charging loads to these high-generation periods.

Figure 4.

Cleared price trajectories: operator electricity price, operator heat price, and user feed-in price.

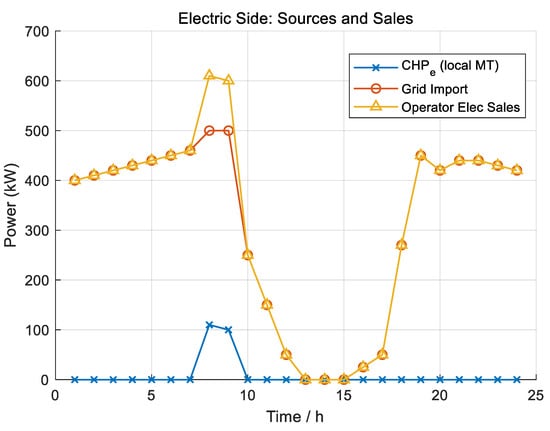

On the electric side (Figure 5), grid imports are curtailed around the solar peak, as EV demand is satisfied by user PV and by CHP electric output only when transformer limits bind. During these binding intervals, the internal shadow price of grid imports rises, forcing the dispatcher to curtail imports and utilize local CHP generation to satisfy the remaining load. Operator electricity sales track the sum of building demand and the operator-sourced share of EV charging.

Figure 5.

Electric-side sources and sales: CHP electric output, grid imports, and total operator electricity sales.

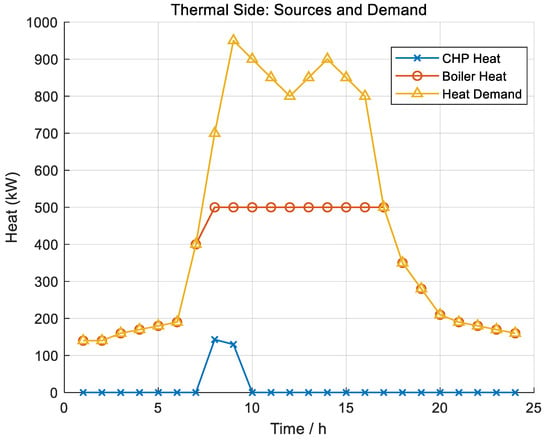

On the thermal side (Figure 6), CHP heat output follows electric co-generation around mid-day, while the boiler heat covers residual heat during morning and evening ramps. The coordinated pricing on the heat channel suppresses uneconomic power-to-heat substitution near noon and maintains thermal balance at low cost.

Figure 6.

Thermal-side sources and demand: CHP heat output, boiler heat, and heat demand.

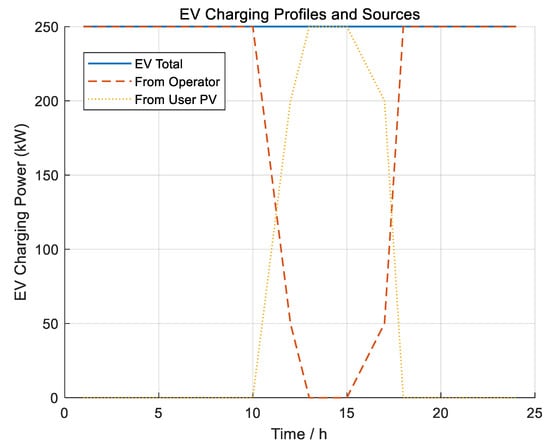

Figure 7 shows the EV charging decomposition. The total EV profile remains within charger and transformer limits. During solar hours, most EV energy is drawn from user PV; the operator-sourced share increases in shoulder periods to smooth residual demand, which reduces evening imports.

Figure 7.

EV charging profiles and source decomposition: total charging, operator-sourced share, and user-PV-sourced share.

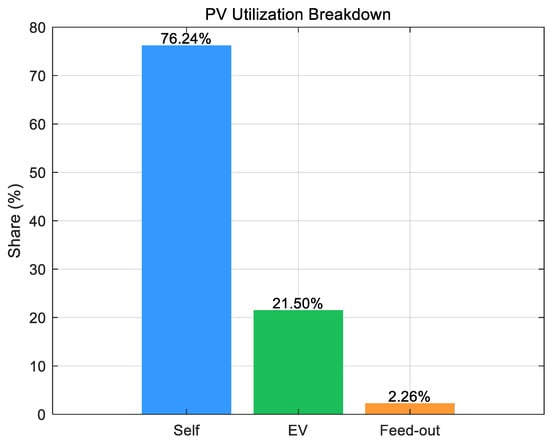

The PV utilization breakdown in Figure 8 indicates that self-consumption is the dominant sink, EV absorption provides a substantial secondary sink during mid-day, and feed-out is minimal. This pattern evidences effective coordination between the price signal and the EV aggregator.

Figure 8.

PV utilization breakdown: self-consumption, EV absorption, and feed-out.

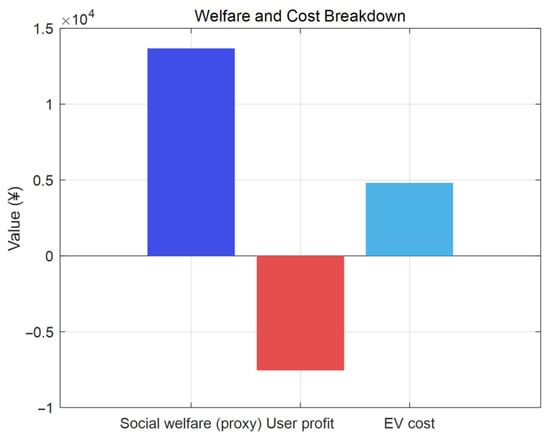

Figure 9 reports the welfare and cost components. Social welfare increases under coordination while the EV charging cost remains moderated relative to the all-from-operator benchmark. User profit reflects the balance between PV subsidies, modest feed-in income, and purchases from the operator; operator profit tracks the net of retail revenues, TOU imports, and CHP/boiler O&M costs.

Figure 9.

Welfare and cost breakdown for the base case.

The coordinated setting thus aligns the EV charging peak with high PV output hours and reduces evening grid imports. The unordered EV setting produces a morning peak that stacks with building native demand and increases purchases at higher TOU prices. The all-from-operator setting raises EV energy cost because it forgoes cheap mid-day PV absorption. All capacity, ramping, balance, and SOC constraints are satisfied. The specific impacts of varying the risk weight

on system performance are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Risk sensitivity analysis.

Risk sensitivity indicates that increasing the risk weight

from

to

produces a significant reduction in

with only a small reduction in expected welfare. Raising

further toward

reduces expected welfare more noticeably and yields diminishing

gains. Wider price bounds increase welfare by enlarging intertemporal freedom but also increase price variability. Higher EV availability increases the share of PV absorbed through charging and reduces EV cost until transformer and CHP capacities begin to bind, at which point marginal gains saturate. Algorithmic ablations confirm that removing grouped projection and penalties increases infeasible trials and slows convergence and skipping annealing leads to premature convergence and inferior welfare. Regarding scalability, the use of an aggregated battery model ensures that the inner-layer computational complexity is independent of the number of individual EVs (Nev), making the framework suitable for large fleets. The computation time scales primarily with the number of PV scenarios (Nps) and time steps (T), which remained tractable for the case study dimensions.

These results show that the closed loop between prices and dispatch combined with a linear source decomposition naturally aligns the EV charging peak with PV high output hours. The joint pricing in electric and thermal channels improves park self-balancing. The CVaR term provides a tunable trade-off between expected welfare and tail robustness. The study offers a reproducible pathway to integrate market signals and engineering constraints in park virtual power plant operation.

6. Conclusions

This paper presented a closed-loop price–dispatch framework for park-scale virtual power plants that co-optimizes electric–thermal flows with distributed PV and EV charging. An improved PSO clears time-varying electricity/heat/user feed-in prices in the outer loop, while a feasibility-projected inner decomposition enforces engineering limits. On a typical winter day, the coordinated scheme synchronized EV charging with solar hours, curtailed evening imports, and respected all capacity and ramp constraints. Photovoltaic utilization reached 99.17% (95.14% self-consumption, 4.03% via EVs) and EV charging cost fell by about 18% versus the all-from-operator benchmark. Prices exhibited interpretable diurnal patterns and the outer loop converged in tens of iterations. CVaR-based risk weighting offered a tunable trade-off between expected welfare and tail losses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and D.T.; methodology, R.M. and T.M.; software, R.M.; validation, Y.H., H.L., and J.L.; formal analysis, R.M.; investigation, L.L. (Luoyi Li) and Y.X.; resources, L.L. (Liqing Liao); data curation, T.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, D.T. and L.L. (Liqing Liao); visualization, R.M.; supervision, D.T.; project administration, D.T. and L.L. (Liqing Liao); funding acquisition, D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of the State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company, grant number 521996250002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are contained within the article. Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Ruiguang Ma, Tiannan Ma, Yanqiu Hou, Hao Luo, Jieying Liu, Luoyi Li and Yueping Xiang were employed by State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company Economic and Technological Research Institute. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wang, J.; Ilea, V.; Bovo, C.; Xie, N.; Wang, Y. Optimal Self-Scheduling for a Multi-Energy Virtual Power Plant Providing Energy and Reserve Services under a Holistic Market Framework. Energy 2023, 278, 127903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Jin, T.; Feng, C.; Li, C.; Chen, Q.; Kang, C. Review of Virtual Power Plant Operations: Resource Coordination and Multidimensional Interaction. Appl. Energy 2024, 357, 122284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Ran, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M. Optimal Energy Scheduling of Virtual Power Plant Integrating Electric Vehicles and Energy Storage Systems under Uncertainty. Energy 2024, 309, 132988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, M. Optimal Day-Ahead Scheduling of Renewable Energy-Based Virtual Power Plant Considering Electrical, Thermal and Cooling Energy. J. Energy Storage 2023, 65, 107363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pan, Z.; Li, S.; Ge, H.; Yang, G.; Wang, B. Optimal Scheduling of Virtual Power Plant Considering Reconfiguration of District Heating Network. Electronics 2023, 12, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, N.E.; Hasan, S.; Al-Durra, A.; Mishra, M.K. Economic Scheduling of Virtual Power Plant in Day-Ahead and Real-Time Markets Considering Uncertainties in Electrical Parameters. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 3837–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, R.; Kong, D.; Guo, H. Coordinated Operation Strategy for Equitable Aggregation in Virtual Power Plant Clusters with Electric Heat Demand Response Considered. Energies 2024, 17, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhi, Y.; Luo, Z.; Fan, H.; Wan, J.; Zhang, T. Optimal Scheduling of Virtual Power Plant with Flexibility Margin Considering Demand Response and Uncertainties. Energies 2023, 16, 5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Tao, W.; Ai, Q. Optimization Scheduling of Combined Heat–Power–Hydrogen Supply Virtual Power Plant Based on Stepped Carbon Trading Mechanism. Electronics 2024, 13, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Decentralized Coordinated Operation Model of VPP and P2H Systems Based on Stochastic-Bargaining Game Considering Multiple Uncertainties and Carbon Cost. Appl. Energy 2022, 312, 118750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Niu, Y.; Qu, C.; Du, M.; Liu, P. A pricing strategy based on bi-level stochastic optimization for virtual power plant trading in multi-market: Energy, ancillary services and carbon trading market. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 231, 110371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Chang, X.; Xue, Y.; Yi, Z.; Li, Z.; Sun, H. Distributed Peer-to-Peer Electricity-Heat-Carbon Trading for Multi-Energy Virtual Power Plants Considering Copula-CVaR Theory and Trading Preference. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 162, 110231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Xu, N.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Tan, Z. Three-Level Market Optimization Model of Virtual Power Plant with Carbon Capture Considering Copula-CVaR. Energy 2021, 237, 121620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, D.; Cai, G.; Lyu, L.; Koh, L.H.; Wang, T. An Optimal Dispatch Model for Virtual Power Plant that Incorporates Carbon Trading and Green Certificate Trading. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 144, 108558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Ran, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M. Optimal Bidding Strategy for Virtual Power Plant in Multiple Markets Considering Integrated Demand Response and Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage. 2025, 124, 116706. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Han, Z.; Chen, F.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, K. Power Allocation Optimization Strategy for Multiple Virtual Power Plants with Diversified Distributed Flexibility Resources. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2024, 18, 4034–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Gao, C.; Jiang, H.; Francois, B. Multi-Objective Optimization and Profit Allocation of Virtual Power Plant Considering the Security Operation of Distribution Networks. J. Energy Storage 2024, 89, 111607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanuni, A.; Sharifi, R.; Feshki-Farahani, H. A Risk-Based Multi-Objective Energy Scheduling and Bidding Strategy for a Technical Virtual Power Plant. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 220, 109344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Guo, Q. Decentralized Energy Management System of Distributed Energy Resources as Virtual Power Plant: Economic Risk Analysis via Downside Risk Constraints Technique. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 183, 109522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y. Distributed Differentially Private Energy Management of Virtual Power Plants. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 234, 110687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tang, L.; Sun, W.; Zhao, H. A Stochastic-CVaR Optimization Model for CCHP Micro-Grid Operation with Consideration of Electricity Market, Wind Power Accommodation and Multiple Demand Response Programs. Energies 2019, 12, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yang, D.; Dehghanian, P. Co-Optimization of Multiple Virtual Power Plants Considering Electricity–Heat–Carbon Trading: A Stackelberg Game Strategy. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 153, 109294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Amin, W.; Umer, K.; Gooi, H.B.; Eddy, F.Y.S.; Afzal, M.; Shahzadi, M.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmad, S.A. A Review of Transactive Energy Systems: Concept and Implementation. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 7804–7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, C. A Bi-Level Optimization Framework for the Power-Side Virtual Power Plant Participating in Day-Ahead Wholesale Market as a Price-Maker Considering Uncertainty. Energy 2024, 304, 132050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooki, O.O.; Popoola, O.M. A Comprehensive Review on Recent Advances in Transactive Energy System: Concepts, Models, Metrics, Technologies, Challenges, Policies and Future. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 50, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X. Towards Transactive Energy: An Analysis of Information-Related Practical Issues. Energy Convers. Econ. 2022, 3, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Li, S.; Guo, J.; Dong, L.; Dong, Y. A Bi-Level Optimization Framework for Virtual Power Plants Integrating Electric Vehicles and Demand Response. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 84, 104740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baringo, L.; Freire, M.; García-Bertrand, R.; Rahimiyan, M. Offering Strategy of a Price-Maker Virtual Power Plant in Energy and Reserve Markets. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2021, 28, 100558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, A.; Hakonen, H.; Lahdelma, R. An Efficient Linear Model and Optimisation Algorithm for Multi-Site Combined Heat and Power Production. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 168, 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-M.; Yang, C.-Y.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Tsai, M.-T. Optimal Control of a Virtual Power Plant by Maximizing Conditional Value-at-Risk. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockafellar, R.T.; Uryasev, S. Optimization of Conditional Value-at-Risk. J. Risk 2000, 2, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.; Parikh, N.; Chu, E.; Peleato, B.; Eckstein, J. Distributed Optimization and Statistical Learning via the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2011, 3, 1–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Luo, F.; Yan, M.; Yan, L.; Guo, C.; Ranzi, G. Distributionally Robust and Transactive Energy Management Scheme for Integrated Wind-Concentrated Solar Virtual Power Plants. Appl. Energy 2024, 368, 123148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Khodaei, A.; Zhang, H.; Han, Z. Optimal Energy Management for Multi-Microgrid Under a Transactive Energy Framework With Distributionally Robust Optimization. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.