Abstract

With the increasing frequency of precipitation events under global warming, understanding rainfall-induced disruptions to urban mobility has become increasingly important. While prior studies primarily focus on road traffic, the lagged and threshold effects of rainfall on urban rail transit (URT) passenger flow remain insufficiently explored. This study analyzes 109 days of automatic fare collection data from Tianhe District, Guangzhou, in combination with hourly meteorological records and station-level built environment attributes. A rainfall threshold-aware gradient boosting framework is proposed to capture nonlinear response regimes, and an explainable learning approach is used to quantify the relative importance of rainfall, temporal factors, and built environment characteristics. The proposed framework outperforms the baseline model, with the root mean squared error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) reduced by over 5.38% and 5.93%, respectively. Results further indicate that lagged rainfall intensity exerts the strongest influence on passenger flow variation, with impact magnitudes varying systematically across station types. These findings enhance understanding of the nonlinear, time-dependent effects of rainfall on URT demand and provide practical guidance for passenger flow management and operational planning under rainfall conditions.

1. Introduction

Climate warming has led to rainfall affecting many cities. On a global average, the number of rainfall events has increased by 7% more than expected due to climate warming [1,2,3]. This affects various aspects of urban systems, including urban rail transit (URT). Due to its large capacity and environmental friendliness, URT has attracted wide attention to satisfy the increasing travel demand, particularly within metropolitan areas. Currently, 59 cities in China’s Mainland have opened URT, with a cumulative total of 11,200 km in operation and an annual passenger volume of 29 billion [4]. To better match transportation capacity with passengers’ travel demand, URT management departments often need to monitor inbound passenger flow under different scenarios to adjust operation strategies.

Therefore, many researchers have explored various aspects of URT passenger flow, such as its spatiotemporal characteristics. However, these studies usually do not take weather effects, especially rainfall, into in-depth consideration—and this is the main focus of this study.

Unlike typical URT passenger flow analysis, rainfall exerts an impact on the travel behavior of URT passengers [5,6,7]. Therefore, the analysis of URT passenger flow fluctuations under rainfall conditions exhibits several unique characteristics and challenges.

- The effect of rainfall on passenger flow usually does not manifest immediately; instead, it exhibits a certain degree of lag or advance effect. This time-staggered effect implies that before or after rainfall occurs, passengers’ travel decisions may be adjusted due to weather expectations or actual weather changes. Consequently, changes in passenger flow may not only occur when rainfall starts, but also possibly happen in advance or with a delay. However, existing studies often emphasize real-time associations and pay limited attention to such lead–lag dynamics.

- The analysis of rainfall’s effect on passenger flow needs to take into account the particularity of rainfall scenarios and various factors. These factors include the built environment of stations and the time periods when passenger flow occurs. Therefore, the model should be able to flexibly adapt to different rainfall scenarios and factors to accurately reflect the actual impact of rainfall on passenger flow. Nevertheless, these heterogeneous effects are rarely modeled explicitly within a unified analytical framework.

Based on the above challenges, this study explores the lead-lag effects of rainfall on passenger flow and introduces an interpretable model based on rainfall scenarios. This model integrates rainfall characteristics, the built environment of stations, and time attributes, effectively filling the gap in existing research regarding the mechanism analysis of how passenger flow is affected by rainfall. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- Methodological contribution

Exploring the lagged mechanism of rainfall’s impact on URT passenger flow: In response to the limitation of existing studies that mostly focus on the immediate correlation between rainfall and passenger flow, this study concentrates on the lead and lag effects of rainfall. By constructing an interpretable machine learning model, it clarifies the temporal gradient law of rainfall’s impact on passenger flow, addressing the deficiency in the analysis of temporal dimension mechanisms in “rainfall–passenger flow” relationship research, and providing certain references for studies related to the impact of weather factors on passenger flow.

- 2.

- Empirical and contextual contribution

Constructing a multi-dimensionally integrated interpretable analysis framework: Traditional machine learning models have difficulties in quantifying variable contributions and the interaction between variables. This study takes into account rainfall characteristics, the built environment of stations, and time-period characteristics, and constructs an analysis framework based on an interpretable machine learning model to identify the differentiated impact patterns of rainfall under various conditions. This framework can not only provide a verifiable analytical basis for explaining the internal mechanism of how rainfall impacts passenger flow, but also offer certain references for subsequent related research.

The remainder of the study is organized as follows: The literature review is discussed in Section 2. In Section 3, the methodology is analyzed herein. Then, the study area and data are described in Section 4. This is followed by the empirical results of the models. Finally, Section 6 and Section 7 focus on discussion, offering conclusive perspectives.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Impact of Weather on Transportation

Weather factors are closely related to transportation. Numerous studies have examined the impact of weather on intercity transportation systems, primarily focusing on highway, maritime, aviation, and railway transport. Early research tended to focus more on maritime and aviation transport, as these modes are more susceptible to weather conditions. For example, by considering seasonal and weather changes, optimal fuel savings can be achieved through ship speed control [8]; flight trajectories can be predicted by accounting for weather influences [9]; seasonal and diurnal climate changes are analyzed for urban air traffic operations to determine expected flight altitudes, while surveys are used to assess travelers’ preferences for air travel under adverse weather conditions [10]; an integrated modeling framework is proposed to predict weather-induced delays in different transportation systems, such as high-speed rail and aviation [11]. Research on the impact of weather on highway traffic volume has also attracted significant attention [12], incorporating traffic, weather, and temporal factors to develop a ridge regression-based fusion prediction model for estimating hourly traffic volume between origins and destinations.

As a critical component of urban transportation systems, the influence of weather on public transit has also been extensively studied. The ordinary least squares (OLS) method was applied to quantify the impact of weather on ride-hailing service demand. As rainfall increases, ride-hailing demand was found to rise correspondingly, with these fluctuations exhibiting significant spatiotemporal distribution characteristics [13]. Nissen et al. [14] analyzed the impact of Berlin’s weather—including temperature, rainfall, sunshine duration, wind speed, and snowfall—on public transit ridership, revealing that rainfall can increase weekday ridership by up to 5%. Additionally, a hybrid simulation-optimization method has been developed for public transit evacuation strategies during extreme weather events, enabling decision-makers to identify optimal solutions under severe time constraints [15]. Additionally, many scholars have conducted research on the impact of weather on URT passenger flow. One study took two URT stations of different types in Delhi, India as the research objects, analyzed the influence of extreme weather such as high temperature and rainfall on passengers’ travel adjustment behaviors, and found that passengers are more inclined to change their original travel patterns in rainy and high-temperature environments, and the quality of facilities around stations significantly regulates the adaptation of passenger flow to extreme weather [16]. Another study relied on passenger flow data and meteorological data of Shenzhen URT to quantify the effect of extreme rainfall on the spatio-temporal distribution of passenger flow, and proposed indicators such as direction imbalance coefficient and section imbalance coefficient. The results showed that rainfall exacerbates the problem of passenger flow imbalance on lines during peak hours [7]. By constructing a multiple linear regression model, Jiang et al. [17] found that temperature residuals have a positive impact on weekday passenger flow, while rainfall inhibits passenger flow, and weekend passenger flow is significantly more sensitive to weather changes than weekday passenger flow. A further study verified the inverted U-shaped relationship between temperature and passenger flow, and pointed out that built environment characteristics, such as the density of enterprises around stations, have a regulatory effect on changes in passenger flow during heatwave weather [18]. In addition, the impact of weather on public transport has also been proven to have various special effects, but relevant research remains relatively limited. A light gradient boosted machine model has been proposed, demonstrating that weather has nonlinear and threshold effects on public transit ridership, while also highlighting complex interactions between weather and passengers’ travel time and spatial patterns [19].

Research on the lagged impacts of weather on transportation systems remains limited, with focus primarily on highway operations, public transport management, and traffic safety. Yang et al. [20] analyzed the lagged effects of adverse weather conditions on highway traffic volume, finding that snowfall and heavy rain have significant delayed and anticipatory impacts. Tao et al. [21] constructed time-series regression models to capture the weather’s influence on bus ridership, showing that temperature and rainfall changes have both immediate and delayed effects. In traffic safety research, lagged weather effects must also be considered, and distributed lag nonlinear models are used to describe the nonlinear relationships and delayed impacts between weather and traffic accidents [22].

Existing research has explored the impact of rainfall on URT passenger flow from multiple dimensions, laying an important foundation for understanding the relationship between the two. However, existing research still has certain limitations: First, most research has not identified the rainfall threshold effect for the URT scenario. One research by scholars such as Lin et al. [12] has conducted preliminary discussions on the weather threshold of public transport, but failed to apply the identified threshold to modeling analysis. Second, the potential lead and lag effects of rainfall are often ignored in existing research. Most research focuses on the analysis of immediate impacts and fails to depict the dynamic response process of passenger flow. To address the abovementioned shortcomings, this research focuses on identifying the threshold effect of URT passenger flow on rainfall and embedding it into the prediction model; at the same time, it systematically examines the lead and lag effects of rainfall to make up for the gaps in current research. Regarding the impact of weather on URT passenger flow, Table 1 summarizes the existing research.

Table 1.

Literature summary on the impact of weather on transportation.

2.2. Methods in URT Passenger Flow Research

In the field of URT passenger flow research, especially when analyzing the impact of multiple factors on passenger flow, the reasonable selection and continuous innovation of research methods and models have always been the core research content of this field.

Traditional time series analysis models, such as the autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model and its extended models, have been widely used in passenger flow prediction [23,24]. The ARIMA model relies on the autocorrelation of time series data and fits data patterns through autoregressive and moving average terms to predict future passenger flow trends. In regular traffic passenger flow scenarios with obvious periodicity, the ARIMA model can well capture cyclical variation characteristics and achieve a certain level of accuracy in short-term passenger flow prediction for stationary time series. However, when affected by weather factors, the uncertainty of weather changes leads to abnormal fluctuations in passenger flow data. The ARIMA model has poor adaptability to such non-stationary and non-linear changes, making it difficult to accurately capture the complex dynamic changes in passenger flow under the influence of weather.

Regression models are also important tools in passenger flow research. Linear regression models attempt to establish a linear relationship between passenger flow and influencing factors (such as time, weather, etc.). They can initially analyze the general direction and extent of the impact of each factor on passenger flow. However, in actual transportation systems, the relationship between passenger flow and numerous factors exhibits complex non-linear characteristics. This makes it difficult for linear regression models to comprehensively and accurately describe such complex relationships, resulting in limited prediction accuracy [25].

With the rise in machine learning technology, a variety of models have been introduced into the research field of passenger flow, providing new approaches to solving complex problems. As a classic machine learning model, the support vector machine (SVM) performs well in small-sample regression tasks [26]. In addition, models such as random forest and decision tree, with their intuitive tree-like structures, can reduce the risk of overfitting and improve model stability [27]. Besides, neural network models are also widely used in traffic passenger flow research. Among them, long short-term memory and gated recurrent unit have demonstrated advantages in passenger flow prediction due to their ability to capture long-term dependencies in time-series data [28]. Nevertheless, neural network models are “black-box” models, lacking interpretability, which makes it difficult to intuitively reveal the intrinsic relationship between factors (such as weather) and changes in passenger flow [29]. Several recent studies have further combined deep learning architectures with statistical components to form hybrid modeling frameworks for passenger flow prediction. Although these approaches often improve predictive performance, the learned nonlinear relationships and potential threshold effects of weather variables remain difficult to interpret explicitly, which limits their applicability for mechanism-oriented analysis.

Among the numerous models, the XGBoost model has attracted considerable attention in the URT passenger flow field in recent years. The built-in regularization term of XGBoost effectively prevents overfitting, enabling it to more accurately capture the complex nonlinear relationships between multiple factors and passenger flow. However, as a black-box model, the XGBoost model has limitations in terms of interpretability [30]. To address this shortcoming, the SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) method, when integrated with XGBoost, has been widely applied in passenger flow impact analysis studies. Several studies have verified the performance of the XGBoost-SHAP hybrid model in traffic passenger flow research [31]. Compared with deep learning-based and hybrid modeling approaches, tree-based ensemble models combined with SHAP provide a more transparent way to identify nonlinear feature contributions and potential threshold-like responses, making them suitable for interpreting weather–passenger flow interactions. Tang et al. [32] conducted multi-classification tasks based on the XGBoost model and analyzed the contribution of each feature to travel behavior classification by integrating SHAP values, thereby identifying the impact of factors such as holidays and travel frequency on changes in travel behavior. In another study, Jiao et al. [33] explored the non-linear relationship between the distance to high-speed rail stations and land value using the XGBoost-SHAP model. They identified 17.3 km as the influential threshold range and revealed the heterogeneity patterns under different HSR (high speed rail) station levels and city types. Some studies have also combined SHAP-based analysis with global sensitivity analysis (GSA), which provides a complementary perspective for quantifying main effects and interaction effects across the feature space [34,35].

2.3. Summary of Literature

At present, research on the impact of weather on transportation has made certain progress. It has explored the response mechanisms of various transportation systems under different weather conditions. It has been confirmed that rainfall exerts a significant impact on urban public transport passenger flow. Based on this finding, the characteristics of passenger flow changes have been analyzed. Furthermore, it has been verified that weather has lagged impacts on transportation systems, with rainfall being one of the key factors. However, existing research still has the following limitations. First, the analysis of the lagged impact of weather on transportation mainly focuses on road transportation and traditional public transportation systems, while the lagged impact mechanism of weather on URT remains unclear. Second, existing models have not yet established an adaptive analysis framework between rainfall and passenger flow, which requires further investigation. Additionally, in the conduct of SHAP analysis, previous studies have focused more on global interpretability and local interpretability, while neglecting the analysis of the interaction between variables.

In response to the limitations of existing research, this study constructs an adaptive analysis framework integrating rainfall characteristics, built environment, and time-period attributes. By introducing a multi-time-period sliding window, it explores the lead-lag effects of rainfall on URT passenger flow to clarify its impact mechanism, while optimizing the SHAP interpretation system and adding a variable interaction detection module to quantify the synergistic effects between rainfall and other factors, thereby filling the gaps in the research on URT dynamic impact mechanism and addressing the shortcomings in the analysis of inter-variable relationships.

3. Methodology

This paper aims to explore the nonlinear relationship between rainfall and URT passenger flow. In recent years, the number of studies using machine learning algorithms to explore the characteristics of URT passenger flow has increased significantly [36]. In this paper, the results of linear models and various nonlinear models are comparatively analyzed. Specifically, the linear model included a linear regression model using OLS; for nonlinear models, several commonly used ones are tested, including SVM, decision tree (DT), gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT), and XGBoost. By comparing metrics in the model estimation results—such as R2, root mean squared error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE)—the XGBoost model is found to show better performance than other models. Based on this, an RT-XGBoost model is proposed according to the research scenario.

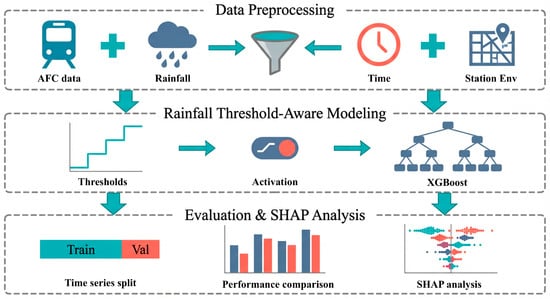

While XGBoost excels in capturing nonlinear relationships and complex feature interaction within datasets, it is often criticized for its “black-box” nature. This limitation impedes the interpretation of how specific predictions are generated and hinders quantitative assessment of the marginal impact of individual input variables on passenger flow forecasts. To address this critical gap, the SHAP algorithm is introduced in this paper—a pivotal advancement in the domain of explainable artificial intelligence [32,33]. In the empirical analysis, the RT-XGBoost model is first used to study the impact of rainfall on changes in URT passenger flow. Subsequently, the SHAP algorithm is applied to further explore the nonlinear relationships between variables. The overall research framework and analytical steps are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research flow chart.

Importantly, the modeling strategy adopted in this study is framed as a retrospective explanatory analysis rather than a predictive or causal modeling. The objective is to characterize empirical associations between observed passenger flows and real-time as well as temporally adjacent rainfall conditions under different temporal and contextual settings. The model is, therefore, estimated using historical data in a post hoc manner, and all variables are included for explanatory purposes. Consequently, the model outputs are interpreted as descriptive summaries of observed regularities in the data, rather than as evidence of causal mechanisms.

3.1. RT-XGBoost

RT-XGBoost is an improved gradient boosting framework derived from the XGBoost model, tailored to capture the non-linear and threshold-dependent relationship between URT passenger flow. While retaining XGBoost’s advantages in handling complex feature interaction and mitigating overfitting via regularization, RT-XGBoost introduces a rainfall threshold-aware activation mechanism to enhance the model’s sensitivity to rainfall intensity variations. This mechanism modulates the feature mapping of rainfall-related variables based on predefined rainfall grade thresholds, addressing the limitation of standard XGBoost in failing to explicitly account for rainfall’s context-dependent influence on passenger flow.

3.1.1. Fundamental Framework

RT-XGBoost retains the ensemble learning logic of XGBoost, which constructs a strong predictor by iteratively training decision trees and minimizing a regularized loss function. For the prediction of the URT passenger flow impact factor, the model’s output is the weighted sum of predictions from decision trees.

The objective function of RT-XGBoost is consistent with that of XGBoost, comprising a loss function and a regularization term, as shown in Equation (1).

where is the t-th tree model; is the loss function; is the regularization term for the t-th tree, designed to prevent overfitting, which can be expressed as Equation (2).

The variable denotes the number of leaf nodes in the t-th decision tree, while and are hyperparameters controlling the regularization intensity. The term corresponds to the weight assigned to each leaf node. The final prediction of the model is obtained through a weighted summation of outputs from all decision trees. During the t-th iteration, the predicted outcome can be formulated as Equation (3).

where is the decision tree space, is the prediction results of sample i after the t-th iteration, and is the prediction results of the previous t – 1 trees.

The predictive performance of a model is governed by two fundamental components: bias and variance. Bias originates from the formulation of the loss function, which defines the optimization objective, while variance is primarily controlled through regularization techniques that constrain model complexity. Accordingly, the overall objective function integrates both aspects through the following formulation:

where is the number of samples, is the true value of the impact factor for the i-th sample, is the predicted value of the i-th sample after (t − 1) iterations, is the prediction of the t-th decision tree for the i-th sample, is the loss function, and denotes the regularization term.

To further clarify the iterative optimization process of the objective function, the loss term is expanded to explicitly reflect the stepwise update logic of the model. The expanded form of the iterative loss is shown in Equation (5):

To solve the optimized objective function efficiently, the loss function is approximated using a second-order Taylor expansion, which converts the non-convex loss into a convex quadratic function that is easier to optimize. The second-order Taylor expansion of the loss function is shown in Equation (6):

where is the first-order derivative of the loss function with respect to the (t − 1)-th iteration prediction value, is the second-order derivative.

Substituting the first-order and second-order derivatives into the iterative loss function, the local optimization objective of each tree can be derived, as shown in Equation (7):

This formula clarifies that each tree in the RT-XGBoost model not only needs to fit the residual gradient but also needs to balance the model complexity through the regularization terms, which is the mathematical basis for the model’s anti-overfitting ability.

3.1.2. Rainfall Threshold-Aware Activation Mechanism

The rainfall threshold-aware activation mechanism of RT-XGBoost can adjust the feature mapping of rainfall-related variables according to rainfall grade thresholds. This mechanism addresses two key challenges: suppressing the contribution of rainfall features in rain-free conditions, and adjusting nonlinear transformations based on different rainfall intensities to reflect their varying impacts on URT passenger flow.

Given that there is relatively little exploration of refined rainfall threshold classification in existing studies, this study conducts subsequent analysis in accordance with the mature classification specifications in the meteorological field to reveal the response law of URT passenger flow under different rainfall intensities. RT-XGBoost defines rainfall into several grades based on hourly rainfall intensity with reference to the meteorological industry standard Grade of Precipitation.

- (1)

- r0 = 0 mm/h: Lower bound of no-rain;

- (2)

- r1 = 0.1 mm/h: Threshold between no-rain and light rain;

- (3)

- r2 = 1.6 mm/h: Threshold between light and moderate rain;

- (4)

- r3 = 3.9 mm/h: Threshold between moderate and heavy rain.

Rainfall thresholds in this study are defined using established meteorological intensity categories to ensure interpretability and comparability. It is acknowledged that such thresholds may not be behaviorally optimal for URT passengers, and transportation-specific breakpoints remain insufficiently documented for contexts comparable to the present study. Nevertheless, systematic differences in passenger flow responses are observed across the adopted rainfall ranges, suggesting that these categories provide a reasonable discriminative segmentation in this application. The sensitivity of the results to alternative threshold settings and the identification of behaviorally optimal breakpoints, therefore, remain issues that warrant further examination.

Let denote the hourly rainfall intensity of sample , and let be the predefined rainfall-grade thresholds. We first define rainfall-grade indicators as , where is the indicator function. These indicators encode which rainfall regime each observation belongs to. Accordingly, for a rainfall-related intermediate feature , the threshold-aware activation applies a grade-specific nonlinear transformation, which can be expressed compactly as , where is the grade-specific exponent to be determined. This formulation ensures that only the transformation corresponding to the active rainfall grade is applied for each observation, thereby enabling regime-dependent rainfall effects while keeping the thresholds interpretable.

Previous studies have shown that when dealing with nonlinear relationships between natural phenomena such as rainfall and other variables, power function transformations can effectively capture the inherent patterns in data. Numerous studies on rainfall thresholds have been expanded and applied based on this power-law formula, confirming the effectiveness of power functions in characterizing complex rainfall-related relationships [37]. Therefore, for each rainfall-related input feature H (denoted as the “shared tree layer output,” i.e., intermediate feature mapping values from previous tree iterations), RT-XGBoost applies a piecewise non-linear activation function to generate the activated feature H1. The function is mathematically expressed as:

where is the vector of intermediate feature values for a rainfall-related variable, is the vector of hourly rainfall intensity corresponding to each sample, is the sign function, used to maintain the direction of influence (positive/negative) of the original features on the passenger flow influencing factor, is the power exponent.

The estimation procedure is described as follows. The dataset is first stratified into subsets according to predefined rainfall intensity intervals. Within each interval, a power-law relationship between rainfall intensity and passenger flow is fitted using a log–log linear regression of the form:

where denotes passenger flow and denotes rainfall within the corresponding interval.

To evaluate the relevance of the fitted relationship, the statistical significance of the slope coefficient is examined. Across all rainfall intervals, the estimated values are statistically significant (p < 0.05), indicating that the power-law approximation provides a reasonable and stable description of the rainfall-passenger-flow association within each regime. The estimated values for different rainfall intervals are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The estimated results for different rainfall intervals.

It should be noticed that the additional model structure introduced in RT-XGBoost is intended primarily to enhance the representation of rainfall-related effects, rather than to increase model complexity. The proposed framework retains the original XGBoost learning architecture, objective function, and regularization scheme, with the threshold-aware activation mechanism applied only to rainfall-related features. As a result, the number of trainable parameters and the overall computational burden remain comparable to those of the baseline XGBoost model.

3.2. SHAP

SHAP is an interpretable AI (XAI) technique proposed by Lundberg [38]. It addresses the “black-box” limitation of tree-based models by quantifying each input feature’s marginal contribution to predictions, enabling both local and global interpretability of the non-linear relationship. In this study, SHAP is applied after model training to interpret rainfall-related effects in RT-XGBoost under a rainfall threshold.

The mean absolute SHAP value quantifies the overall importance of a feature, while the relationship between SHAP values and feature values indicates the direction of influence: a positive correlation implies the feature exerts a positive impact on predictions, whereas a negative correlation indicates a negative impact [39]. In SHAP, the contribution of each feature to the model output is allocated based on its marginal contribution, with the Shapley value mathematically expressed by Equation (9):

where is the number of input features, is the set of all input features, including rainfall variables, built environment variables, and temporal variables. is the deviation of the i-th variable’s Shapley value from the expected mean, illustrating its contribution to an individual prediction.

Shapley interaction values extend the concept of SHAP values to quantify the interactive contribution of two features. For a pair of features, the Shapley interaction value is defined as

where is the full set of features, is the weighting term, the term is the interaction effect for a subset .

4. Study Area and Data

4.1. Study Area

The research city of this study is Guangzhou, a coastal city in Guangdong province, located in southern China. As one of the most densely populated areas in China, Guangzhou has a total population of over 18 million. With a subtropical monsoon climate, Guangzhou experiences high rainfall, averaging over 1800 mm annually and about 150 rainy days in a year. The Tianhe District, as the central urban area of Guangzhou, is characterized by a well-developed URT network. Therefore, Tianhe District is selected as the study area to analyze the change characteristics of URT passenger flow under rainfall conditions, based on the entry passenger flow data collected from URT stations within this region. The spatial distribution of rail transit in Tianhe District is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

URT lines in Tianhe District.

4.2. Study Data

The passenger flow data comes from the automatic fare collection system of URT stations in Guangzhou. The passenger flow from July to October 2015 is selected for analysis, corresponding to the main rainy season in the study area. A few days before and after the major holiday are excluded from the analysis. Finally, 109 days of passenger flow and corresponding rainfall data are extracted to study the relationship between rainfall conditions and URT passenger flow. The study period is further constrained by data availability and consistency considerations, as only observations within this interval are continuously monitored and quality-controlled across all data sources. In addition, no URT stations were closed due to extreme weather events during the study period.

Three categories of variables are selected for the study, focusing on rainfall variables, built environment variables, and time variables. The historical rainfall data is obtained from the source website: https://xihe-energy.com (accessed on 5 January 2025), which provides comprehensive data support for energy enterprises, government agencies, and research institutions. The spatial data of the stations are obtained from the map open platform. For the spatial study scope of the stations, a catchment radius of 500 m to 1000 m is commonly adopted in most studies. Based on research on the attraction range of stations in Guangzhou, a catchment radius of 800 m is determined to be appropriate [40]. The descriptions and numerical characteristics of each variable are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

In Table 3, the lead rainfall intensity refers to rainfall intensity observed in subsequent time periods (e.g., t + 1 h) within the same historical dataset. This variable is included to describe empirically observed anticipatory response patterns in passenger flow around rainfall events. As the analysis is conducted retrospectively using fully observed data, the lead rainfall variable serves a post hoc interpretive purpose and is not intended for prediction or causal inference.

The mathematical expression of the rainfall change rate is as follows:

where is the rainfall change rate, is the real-time rainfall intensity, and is the rainfall intensity in the previous hour.

When calculating the rainfall change rate, a conditional stabilization step is applied to ensure numerical validity and avoid small-base effects. Specifically, when rainfall in both the current hour and the previous hour is below 1.6 mm/h, the change-rate value is treated as a baseline condition, because near-zero rainfall can yield spuriously large relative rates that are not behaviorally meaningful. For cases involving more substantial rainfall intensities, the change rate is computed using the stabilized formulation in Equation (12), which captures meaningful rainfall dynamics.

5. Results

5.1. Overall Performance Comparison

To ensure the optimal performance of the RT-XGBoost model, a systematic hyperparameter optimization process is first conducted. Subsequently, a comparative analysis is performed against the OLS, SVM, DT, GBDT, and XGBoost to validate its superiority. This evaluation focuses on overall model fitting and relative performance under the same data.

The hyperparameters of RT-XGBoost are optimized using a two-stage approach: grid search for key parameters combined with rolling-origin (time series split) cross-validation, which aims to balance model complexity and generalization ability (Figure 3). The main optimized parameters and their values are presented in Table 4.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of time series split.

Table 4.

Parameter optimization.

To validate the superiority of the RT-XGBoost model, an analysis framework is established. Five models are selected for performance comparison, including OLS, SVM, DT, GBDT, and XGBoost, with the key parameter settings summarized in Table 5 to facilitate replication and ensure reproducibility.

Table 5.

Model parameter settings.

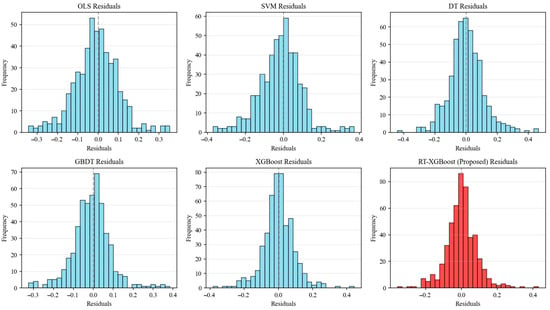

The performance assessment is carried out from two dimensions: First, the scatter distributions of predicted values against actual values (shown in Figure 4) are analyzed to observe the alignment between model predictions and actual data. Then, the residual frequency histograms (shown in Figure 5) are examined to gain insights into the error characteristics of each model. Additionally, quantitative evaluation metrics, including R2, RMSE, and MAE, are integrated to enable an objective and numerical comparison of model performance.

Figure 4.

Comparison of model performance.

Figure 5.

Frequency histogram of residuals.

Figure 4 illustrates the discrepancies between each model’s predictions and their corresponding actual values. Baseline models (OLS, SVM, and DT) exhibit very limited out-of-sample explanatory power, with predictions concentrated in a narrow range and R2 values close to zero. Ensemble-based approaches show improved alignment with observed values. GBDT and XGBoost achieve moderate predictive performance, with R2 values of 0.2747 and 0.3349, respectively. RT-XGBoost attains an out-of-sample R2 of 0.4045 and the lower RMSE and MAE among the evaluated models. While this level of performance should not be interpreted as strong predictive accuracy in an absolute sense, the results indicate that incorporating rainfall thresholds yields relative improvements over baseline models.

While the proposed model captures key nonlinear and threshold-dependent rainfall responses, the overall explanatory power remains moderate, which is expected for complex urban mobility systems. Previous studies on short-term transit demand and weather-sensitive travel behavior have reported similarly modest R2 values and regard them as acceptable, given the strong influence of unobserved behavioral, operational, and stochastic factors [41,42,43,44,45].

Figure 5 presents the residual distribution characteristics of different models. As observed from the figure, the residual distribution of the RT-XGBoost model is the most concentrated, with a high peak and rapid attenuation on both sides—indicating that its prediction errors are small and the degree of dispersion is low. In contrast, the residual distributions of the OLS, SVM, DT, GBDT, and XGBoost models are relatively scattered, with a wider range of error fluctuations. It can thus be concluded that the RT-XGBoost model exhibits the optimal performance in terms of prediction accuracy and residual consistency, as it can fit the data more accurately and reduce prediction errors.

To further evaluate the robustness and statistical significance of model performance differences, the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests are conducted to compare RT-XGBoost with each baseline model in terms of RMSE and MAE. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) are confirmed between RT-XGBoost and all baseline models, indicating that the performance improvement is statistically meaningful rather than random variation.

Based on these results, Figure 6 further provides a confidence-interval–based comparison of model performance. The distributions of RMSE and MAE are displayed for each model, together with the corresponding mean values and 95% confidence intervals. As shown in Figure 6, RT-XGBoost achieves lower mean RMSE and MAE, while its confidence intervals are located at lower error ranges compared with those of the baseline models. This indicates that the observed performance gains are maintained across different validation splits, rather than being driven by isolated favorable folds.

Figure 6.

Comparison of model performance with 95% confidence intervals.

5.2. Global Interpretability of the Model

To examine how rainfall-related features are associated with URT passenger flow in the RT-XGBoost model, the global interpretability analysis is conducted using SHAP. This analysis quantifies the relative contribution of each input feature to model predictions and facilitates interpretation of model response patterns related to rainfall (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Feature importance and feature impact distribution.

The SHAP results show that rainfall-related variables are among the most important features in the model, with both lagged and lead rainfall terms ranking highly in terms of contribution. In particular, rain_lag_1 emerges as the strongest contributor, followed by rain_lag_3, while real-time rainfall and several lead terms (e.g., rain_lead_3 and rain_lead_2) also make substantial contributions. This pattern indicates that the model associates URT passenger flow not only with current rainfall conditions but also with rainfall in temporally adjacent periods.

The SHAP beeswarm distributions further suggest that higher values of key rainfall features—especially rain_lag_1, rain_lag_3, and rainfall—are generally linked to more positive SHAP values, corresponding to higher predicted passenger flow, whereas low rainfall levels tend to contribute negatively or remain near zero. Within the scope of this study, one plausible interpretation is that rainy conditions coincide with reduced use of weather-sensitive travel modes such as walking and cycling, alongside a higher share of rail transit usage. Conversely, when rainfall is low or absent, the model tends to assign lower predicted ridership. Overall, these results suggest that rainfall can be regarded as a short-term correlate of variation in URT passenger flow within the modeling framework. Interestingly, real-time rainfall is not consistently more important than recent rainfall in the model. The fact that rain_lag_1 and rain_lag_3 contribute more than the real-time rainfall term suggests that the model captures time-shifted rainfall patterns rather than relying solely on current conditions.

Among non-rainfall factors, built-environment and temporal variables remain important predictors of passenger flow. Notably, company is one of the most influential non-rainfall features, while weekday and peak also contribute meaningfully. Compared with rainfall variables, their SHAP distributions appear more concentrated, indicating comparatively stable contributions. Compared with rainfall variables, their SHAP distributions exhibit lower dispersion, indicating more stable contributions.

Overall, the SHAP-based analysis underscores rainfall as a key factor influencing short-term variation in URT passenger flow through a lagged effect. These results suggest implications for short-term demand prediction and operational planning, such as incorporating recent rainfall information into service adjustment strategies. It should be noted that SHAP provides correlational explanations of model behavior rather than causal inference within this scope [46,47].

5.3. Synergistic Effects

When exploring the impact of rainfall on rail transit passenger flow, the independent role of a single feature only presents local patterns. However, the interaction between features can more comprehensively reveal passenger flow patterns in complex scenarios. The SHAP interaction value can quantify the synergistic or antagonistic effects of feature combinations on model prediction. By analyzing the interaction of multiple features, a basis is provided for passenger flow regulation strategies.

Figure 5 covers features such as rainfall, time, and built environment. The matrix visualizes interaction between features, where both axes denote feature names and the color intensity corresponds to the magnitude of their mutual influence.

Figure 8 illustrates the SHAP interaction heatmap, which represents how pairs of features jointly influence the model’s results. The most prominent structure in the heatmap is the interaction among rainfall-related variables, including real-time rainfall as well as lagged and lead rainfall terms. This suggests that the model encodes rainfall as a temporally contextual signal, where recent and anticipated rainfall jointly modify the predicted impact. At a behavioral level, this pattern is consistent with the idea that individuals or systems represented in the data may respond to rainfall in an accumulated or anticipatory manner—for example, adapting travel or activity decisions based on recent conditions or expectations of near-future weather [48], although SHAP itself does not establish such processes causally.

Figure 8.

Distribution of SHAP interaction.

Interaction effects between rainfall variables and the company feature are comparatively stronger than those involving other non-meteorological factors. In terms of model behavior, this implies that the contribution of rainfall to the prediction is adjusted depending on workplace-related contextual factors. A plausible behavioral interpretation is that activities associated with employment or office environments may exhibit different sensitivities to rainfall, prompting the model to rely on interaction terms when representing these conditions. However, this interpretation reflects how the model organizes information and should not be taken as direct evidence that business-related activities causally alter rainfall responses.

By contrast, variables such as weekday, peak, and several features show relatively weak interaction effects with other factors. This suggests that, within the model, these features primarily contribute through their main effects rather than through interactions.

6. Discussion

Based on the results in Section 5.3, a grouped fitting approach was employed to explore how rainfall-related features interact with the variable company. Specifically, samples were categorized into “high-value” and “low-value” groups using the median of the interactive features, and fitting curves along with their confidence intervals were plotted for each group (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Interaction between rainfall and the built environment.

Figure 9 shows clear differences in SHAP interaction patterns for rainfall-related variables across enterprise-density contexts. For lagged rainfall, interaction SHAP values in high enterprise-density areas (company > 507.00) are strongly concentrated around zero across the entire rainfall range, with only minor fluctuations. This indicates that, in the model, lagged rainfall contributes little additional interaction effect under high-density conditions. In contrast, for low enterprise-density areas (company ≤ 507.00), interaction SHAP values display a more evident negative trend as lagged rainfall increases, with the fitted curves shifting from values near zero at low rainfall levels to clearly negative values at higher rainfall, implying a relative weakening of interaction contributions in these contexts.

The contrast between the two groups is most pronounced for rain_lag_1. While the high-density group remains near zero throughout, the low-density group shows a gradual but consistent downward shift with increasing rainfall, highlighting a divergence in modeled interaction direction for short-term lag effects.

A similar but weaker pattern is observed for lead rainfall variables. Interaction SHAP values for the high-density group again remain close to zero with no strong monotonic trend, whereas the low-density group exhibits a modest negative shift at higher rainfall levels. Overall, the magnitude of separation between the two groups under lead rainfall is smaller than that observed for lagged rainfall, with most interaction values still concentrated near zero, suggesting a relatively limited moderating role of enterprise density in the model’s treatment of lead rainfall.

In the rainfall subplot, the group difference becomes more distinct: as rainfall increases, the low-density group shows a clearer downward movement in interaction SHAP values, while the high-density group declines more mildly and remains close to zero. By comparison, in the change_rate subplot, interaction SHAP values for both groups largely overlap and stay centered near zero across the range, indicating that rainfall change rate contributes weak interaction effects.

Beyond behavioral interpretation, these model-based, station-specific interaction patterns provide decision-relevant insights for line-level service coordination and for improving connectivity with existing public transport services [49], aligning with integrated transit planning perspectives.

7. Conclusions

This study investigates the lagged effect of rainfall on URT passenger flow in Guangzhou by proposing an RT-XGBoost model to capture nonlinear and threshold relationships between rainfall and URT passenger flow. Model interpretability is enhanced using SHAP, and interaction effects among rainfall and built environment are explored through SHAP interaction values and grouped fitting analyses. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The RT-XGBoost model demonstrates better performance than the baseline models. Beyond achieving a higher out-of-sample R2 and a lower RMSE and MAE, confidence-interval-based comparative analysis further confirms the robustness of its performance. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests show that its error reductions are statistically significant compared with other models. Together with the residual distribution, these results confirm that RT-XGBoost provides improved accuracy and enhanced robustness in modeling rainfall–passenger flow relationships.

- (2)

- SHAP-based global interpretability analysis identifies rainfall-related variables as the dominant drivers of short-term variation in URT passenger flow, with lagged rainfall playing an important role. Among all input features, rain_lag_1 and rain_lag_3 rank among the top contributors, exceeding the importance of real-time rainfall, which indicates a clear lagged effect in the model’s response to rainfall. Among non-rainfall features, built-environment characteristics (company density) rank as the third most important contributor overall, followed by temporal variables such as weekdays. Compared with rainfall features, these non-meteorological variables show more concentrated SHAP distributions, suggesting more stable but less variable contributions.

- (3)

- SHAP interaction analysis reveals that interaction effects are mainly concentrated among rainfall-related variables. Interactions between rainfall and company density are more pronounced than those involving other non-meteorological features. Grouped fitting results further show clear contextual differences: in high enterprise-density areas, interaction effects between rainfall and company remain weak and close to zero across rainfall levels, while in low enterprise-density areas, increasing rainfall, especially lagged rainfall, is associated with a gradual negative shift in interaction SHAP values. By contrast, interactions between rainfall and peak or weekday variables are generally weak, indicating that these factors mainly act through their main effects rather than strong synergistic mechanisms.

Beyond these empirical findings, the results offer practical implications for URT operations and management. The identified lagged and synergistic effects of rainfall suggest that transit authorities could adopt pre-emptive scheduling strategies and passenger flow redistribution measures before rainfall events, particularly in areas with high enterprise density. Future research can be further extended in the following directions: (1) conducting cross-city validation to examine the transferability of the proposed framework across different urban contexts; (2) incorporating additional influencing factors, such as operational information and other weather conditions, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of passenger flow variation; and (3) applying GSA to further explore the causal mechanisms and spatial–temporal heterogeneity in the rainfall–passenger flow relationship.

Author Contributions

Methodology, B.L. and S.L. (Sirui Li); software, S.L. (Sirui Li) and X.W.; validation, S.L. (Shasha Liu) and Q.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. (Sirui Li); writing—review and editing, B.L. and Z.Y.; visualization, S.L. (Sirui Li); supervision, B.L.; funding acquisition, B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing Municipal Education (KJQN202400749), the Foundation of Key Laboratory of Transport Industry of Big Data Application Technologies for Comprehensive Transport (ZHJTDSJ202401) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52302382, 52302386).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Witze, A. Why Extreme Rains Are Gaining Strength as the Climate Warms. Nature 2018, 563, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papalexiou, S.M.; Montanari, A. Global and Regional Increase of Precipitation Extremes Under Global Warming. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 4901–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, J.; Chen, G.; Li, C. Dynamic Amplification of Subtropical Extreme Precipitation in a Warming Climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL087200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Xie, M. The Impact of Transportation on Commercial Activities: The Stories of Various Transport Routes in Changchun, China. Cities 2023, 132, 103979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Zhu, Y.; Huo, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Resilience Assessment of Metro Stations against Rainstorm Disaster Based on Cloud Model: A Case Study in Chongqing, China. Nat. Hazards 2023, 116, 2311–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zheng, J.; Li, M.; Shao, Z.; Li, L. Gauging the Evolution of Operational Risks for Urban Rail Transit Systems under Rainstorm Disasters. Water 2023, 15, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Meng, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhong, M. Analyzing Spatio-Temporal Impacts of Extreme Rainfall Events on Metro Ridership Characteristics. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 577, 126053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskar, B.; Andersen, P. Benefit of Speed Reduction for Ships in Different Weather Conditions. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2020, 85, 102337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yan, H.; Liu, Y. Data-Driven Trajectory Prediction with Weather Uncertainties: A Bayesian Deep Learning Approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 130, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, C.; Cohen, A.P.; Fernando, C. An Initial Assessment of the Potential Weather Barriers of Urban Air Mobility. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 6018–6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L. Predicting Weather-Induced Delays of High-Speed Rail and Aviation in China. Transp. Policy 2021, 101, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; He, Y.; Pei, M.; Yang, R. Data-Driven Spatial-Temporal Analysis of Highway Traffic Volume Considering Weather and Festival Impacts. Travel. Behav. Soc. 2022, 29, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jiang, H.; Chen, Z. Quantifying the Impact of Weather on Ride-Hailing Ridership: Evidence from Haikou, China. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 24, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, K.M.; Becker, N.; Dahne, O.; Rabe, M.; Scheffler, J.; Solle, M.; Ulbrich, U. How Does Weather Affect the Use of Public Transport in Berlin? Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 085001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Mojtahedi, M.; Loosemore, M. Enhancing Evacuation Response to Extreme Weather Disasters Using Public Transportation Systems: A Novel Simheuristic Approach. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2020, 7, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Singh, S. Adaptation of Trips by Metro Rail Users at Two Stations in Extreme Weather Conditions: Delhi. Urban Clim. 2021, 36, 100766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Cai, C. The Impacts of Weather Conditions on Metro Ridership: An Empirical Study from Three Mega Cities in China. Travel Behav. Soc. 2023, 31, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Tan, Z. The Impacts of Extreme Hot Weather on Metro Ridership: A Case Study of Shenzhen, China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 117, 103899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Weng, J.; Brands, D.K.; Qian, H.; Yin, B. Analysing the Relationship between Weather, Built Environment, and Public Transport Ridership. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 14, 1946–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yue, X.; Sun, H.; Gao, Z.; Wang, W. Impact of Weather on Freeway Origin-Destination Volume in China. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 143, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Corcoran, J.; Rowe, F.; Hickman, M. To Travel or Not to Travel: ‘Weather’ Is the Question. Modelling the Effect of Local Weather Conditions on Bus Ridership. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 86, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Huang, H.; Zhan, Z.Y.; Zhai, X.; Ou, C.; Sze, N.N.; Hon, K.K. Hourly Associations between Weather Factors and Traffic Crashes: Non-Linear and Lag Effects. Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 2019, 24, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Ye, Z.; Wang, C.; Xu, M. Subway Passenger Flow Prediction for Special Events Using Smart Card Data. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 21, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, S.; Ghasri, M.; Sisson, S.A.; Rashidi, T. Ensemble of ARIMA: Combining Parametric and Bootstrapping Technique for Traffic Flow Prediction. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2020, 16, 1552–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Sharda, S.; Zhou, X.; Pendyala, R.M. A Stepwise Interpretable Machine Learning Framework Using Linear Regression (LR) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM): City-Wide Demand-Side Prediction of Yellow Taxi and for-Hire Vehicle (FHV) Service. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 120, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Yao, E.; Huan, N.; Li, B.; Liu, S. Prediction of Urban Rail Transit Ridership under Rainfall Weather Conditions. J. Transp. Eng. A Syst. 2020, 146, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, H.; Rastgoo, A. Predicting the Carbon Dioxide Emission Caused by Road Transport Using a Random Forest (RF) Model Combined by Meta-Heuristic Algorithms. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 93, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalesian, M.; Furno, A.; Leclercq, L. Improving Deep-Learning Methods for Area-Based Traffic Demand Prediction via Hierarchical Reconciliation. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 159, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Yang, H.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, J.; Zhou, S. Traffexplainer: A Framework Toward GNN-Based Interpretable Traffic Prediction. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2025, 6, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Jiang, S.; Liu, M.; Sun, X.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Hao, Q.; Du, W.; Long, Y. A Step Toward Sustainable Cities: Recognizing the Transportation Modes of Urban Residents Based on Mobile Phone Location Data. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Ma, S.; Li, C. Exploring the Impact of Built Environment on Elderly Metro Ridership at Station-to-Station Level. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Jia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, H.; Pei, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Why Metro Passengers Change Travel Behavior: Individual-Level Insights from Interpretable Machine Learning. Cities 2025, 167, 106352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; An, R.; Du, D.; Zhu, M. Non-Linear and Heterogeneous Relationship between Proximity to High-Speed Rail Stations and Land Value in China: Analysis Using XGBoost-SHAP Modelling. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 196, 104486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsattar, D.M.; Owais, M.; Fahmy, M.F.M.; Osman, R.; Nafadi, M.K. Optimizing Pozzolanic Concrete Mixtures Using Machine Learning and Global Sensitivity Analysis Techniques. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2025, 19, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owais, M. Preprocessing and Postprocessing Analysis for Hot-Mix Asphalt Dynamic Modulus Experimental Data. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 450, 138693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuwang, D.D.; Chen, W.; Zhong, M. Short-Term Urban Rail Transit Passenger Flow Forecasting Based on Fusion Model Methods Using Univariate Time Series. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 147, 110740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Shao, X.; Xu, C. Physically-Based Rainfall-Induced Landslide Thresholds for the Tianshui Area of Loess Plateau, China by TRIGRS Model. Catena 2023, 233, 107499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Allen, P.G.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, S.; Li, W.; Yang, H. What Determines Carbon Emissions of Multimodal Travel? Insights from Interpretable Machine Learning on Mobility Trajectory Data. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lyu, D.; Huang, G.; Zhang, X.; Gao, F.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X. Spatially Varying Impacts of Built Environment Factors on Rail Transit Ridership at Station Level: A Case Study in Guangzhou, China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 82, 102631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Deng, Z.; Tang, J.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, P. Uncovering Human Behavioral Heterogeneity in Urban Mobility under the Impacts of Disruptive Weather Events. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2025, 39, 951–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Liang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Guan, Q.; Jiang, R.; Shibasaki, R. Resilience Patterns of Multiscale Human Mobility Under Extreme Rainfall Events Using Massive Individual Trajectory Data. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2025, 115, 578–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Q.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Liu, G. Resilience Assessment and Enhancement Strategies for Urban Transportation Infrastructure to Cope with Extreme Rainfalls. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Sung, M.; Hwang, J. When Less Travel Means More Carbon: How Rainfall-Induced Shifts from Public Transit to Cars Increase Urban Transport Emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2026, 1013, 181269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wu, S.; Yang, S.; Shi, Y. Resilience Assessment of Urban Road Transportation in Rainfall. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, G.; Lykov, A.; Schleich, M.; Suciu, D. On the Tractability of SHAP Explanations. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2022, 74, 851–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcilio, W.E.; Eler, D.M. From Explanations to Feature Selection: Assessing SHAP Values as Feature Selection Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2020 33rd SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images (SIBGRAPI), Porto de Galinhas, Brazil, 7–10 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Haraguchi, M.; Lall, U. Enhancing Urban Resilience to Extreme Weather: The Roles of Human Transition Paths among Multiple Transportation Modes. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 39, 2408–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owais, M.; Ahmed, A.S.; Moussa, G.S.; Khalil, A.A. Integrating Underground Line Design with Existing Public Transportation Systems to Increase Transit Network Connectivity: Case Study in Greater Cairo. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 167, 114183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.