Abstract

The present research demonstrates the utility of the linear canonical transform (LCT) in constructing the characteristic function of real random variables. We refer to this construction as the linear canonical characteristic function (LCCF). The proposed LCCF aims to address the limitations of the classical characteristic function in both theoretical and applied aspects. Using this approach, we investigate its properties, such as Hermitian symmetry, continuity, convolution, and derivatives, which are generalized forms of the classical characteristic function in the literature. Finally, we implement the obtained results by calculating several probability density functions in the LCCF domains.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, the linear canonical transform (LCT) has attracted considerable research interest. The LCT may be interpreted as a natural expansion of the classical Fourier transform (FT) and the fractional Fourier transform (FrFT) [1,2], which implies that the LCT is more flexible and superior to the FT and the FrFT. The LCT has received a lot of attention and has become a hot topic due to its usefulness in various disciplines; see, e.g., [3,4,5,6]. In the past ten years, detailed studies on essential properties related to the LCT, such as shifting, modulation, derivatives, Parseval’s relation, inequalities, convolution, and correlation theorems, have been presented in [7,8,9,10].

As is well known, in probability theory, there is a close relationship between the classical characteristic function (CF) and the Fourier transform (FT), where the CF may be considered as the FT of its probability density function. These facts have inspired a promising research direction, and a number of papers have since appeared that contain generalizations and extensions of the characteristic function in various transformations. For instance, the authors of [11,12] have proposed the fractional characteristic function of any random variable, which is a non-trivial generalization of the characteristic function using the Mittag-Leffler transform [13]. Several important properties of this extended characteristic function have been demonstrated in detail. In [14], the authors have discussed the characteristic function in the setting of Clifford algebra using the one-dimensional Clifford Fourier transform. The works of the authors in [15,16,17] have explored the characteristic function in quaternion algebra using the quaternion Fourier transform and quaternion fractional Fourier transform. Recently, the authors of [18,19] have studied the utility of the quaternion linear canonical transform (QLCT) in probability modeling. They also introduced the quaternion characteristic function in the framework of the QLCT. Despite these significant advancements, further exploration is still needed to extend the classical characteristic function in the context of the LCT, which we call the linear canonical characteristic function (LCCF).

In the present work, we first introduce the definition of the LCCF. The direct connection between the LCCF and the classical characteristic function is also presented. Various properties of the LCCF are demonstrated. We make a fascinating connection between the moments and the LCCF. Based on this relation, we obtain a new definition of variance in the context of the LCCF. Finally, some simple examples of the LCCF are also presented to illustrate the obtained theoretical results.

The structure of our paper is as follows. In Section 2, we introduce the basic concept of the LCT and summarize its basic properties, which will be useful for this research. In Section 3, we focus on the construction of the LCCF and derive some of its key properties. In Section 4, an interesting relationship between the moments and the LCCF is investigated in detail. In Section 5, we provide some illustrative examples of the LCCF for well-known probability density functions. Lastly, a simple conclusion is given in Section 6.

2. Linear Canonical Transform and Properties

First, we intend to recall the basic concept of the LCT and then summarize some of its basic properties, which are crucial for the main results of this research.

Definition 1.

Let denote the matrix parameter for which . The LCT of a signal is defined by

where

is the kernel function of the LCT.

The original signal f above can be restored using the inversion formula for the LCT as follows:

Definition 2.

Let , such that . The inversion of the LCT is described through

where represents the complex conjugate of .

The following lemma collects the elementary properties of the LCT defined above. For more comprehensive information, readers are encouraged to refer to [3,4,5,7,9,10,20].

Lemma 1.

We have the following properties:

- 1.

- LinearityLet f,g in and let , be real constants. Then

- 2.

- ShiftingLet , and the shifted operator is defined by . Then, we have

- 3.

- ModulationFor any function with . If , one gets

By exploiting Equation (1) above, the LCT definition can be reduced to that of the Fourier transform, that is,

This equation is equivalent to

where stands for the Fourier transform of the signal given by [21,22]

3. Characteristic Function in LCT

Recently, the authors of [11,12,23] have proposed the fractional characteristic function, which is a natural generalization of the classical characteristic function using a fractional calculus approach. This part will construct the characteristic function in the context of the LCT and investigate its crucial properties.

For a real random variable X with probability density function (pdf) , the (classical) characteristic function of X is defined by

and the characteristic function of is

Equation (10) may be represented as

where is the moment. Equation (10) shows that the characteristic function is constructed using the kernel of the Fourier transform (FT). Based on this idea, we extend the characteristic function using the LCT kernel, which is called the linear canonical characteristic function (LCCF). The LCCF is obtained by replacing the FT kernel with the LCT kernel in Equation (10). To this end, we start with the following definition:

Definition 3.

Let be a real random variable whose probability density function is . The LCCF, denoted by , is defined by

provided the integral exists and is finite.

We may express Equation (13) in the following form:

Now, if we assume that

then Equation (14) may be expressed as

for which

It can easily be seen that when we take , Equation (16) changes to Equation (12). The relation of the LCCF with the classical characteristic function is given by

In particular, we have

We collected some of the basic properties of the LCCF in the following lemma:

Lemma 2.

Let X be a real random variable. We have the following properties:

- , where , .

- .

Proof.

We just derived part 3, and the others are similar. With the help of Relation (13), we immediately get

□

In particular, when , Expression (20) becomes .

Another property of the LCCF is given by

To verify (21), we see that

Also, it is quite simple to check that

Here, . By virtue of Relations (18) and (22), one has

and

Furthermore, according to (3), the probability density function in terms of the LCCF is given by

The other properties of the LCCF are collected in the following theorems. These properties are an extended version of the classical characteristic function [24].

Theorem 1.

Let X be a random variable. Let denote the LCCF of the function f, then

where α and β are constants. In this case, and .

Proof.

It follows from Equation (13) that

The above expression may be rewritten in the form

which finishes the proof. □

Remark 1.

Taking the matrix in Theorem 1, we obtain

which is the basic property of the characteristic function.

Theorem 2.

Let X be a real random variable. Then is uniformly continuous on .

Proof.

The following result explains that the LCCF of the convolution of two probability density functions is equal to the simple product of their respective LCCFs with the chirp signal.

Theorem 3.

Suppose that and are probability density functions of independent random variables X and Y. Then, we have

where the convolution of two probability density functions of and is defined by

4. Moments, Variance, and Their Relationship to LCCF

As is well known, moments and variances of a random variable are closely related to characteristic functions, where they can be obtained from the derivatives of the characteristic functions. In this part, we shall discuss these important facts in relation to the proposed LCCF. The main result of this section is a fundamental relation between the nth derivative of the LCCF calculated at zero and the nth moment. In this regard, we first recall the nth moment of a real random variable X as

provided the integral exists. Based on Equation (35), we define the nth moment related to the LCCF as

Equation (36) may be expressed in the following form:

in which is described by Equation (17). In particular, when , we may utilize the following result to calculate (36) through the LCCF:

Theorem 4.

Let X be a real random variable and let be the LCCF of X. Then there exists the second continuous derivative for the LCCF, which is described by

Furthermore,

Proof.

From Equation (13), it follows that

This equation yields

Therefore,

This implies that

which is the first moment of a real random variable, X, related to the LCCF.

Remark 2.

By putting the matrix in Equation (39), we immediately obtain

By Equation (36), the variance of the random variable X is therefore defined as

If Equation (15) is satisfied, Equation (48) produces

From Equations (39) and (43), we get the variance in terms of the LCCF as

If we choose , then Equation (50) becomes

In what follows, we establish the nth derivative of the LCCF related to its moment. In this regard, we obtain the important theorem.

Theorem 5.

Let X be a real random variable. Then there exists an nth continuous derivative for the LCCF , given by

Proof.

By invoking Equation (13), we get

This equation leads to

By induction, it follows that

The proof is complete. □

Remark 3.

By selecting in Theorem 5, we obtain

Equation (55) explicitly describes the basic relationship between the derivative of a classical characteristic function, evaluated at 0, and the moment of the random variable X.

5. Illustrative Examples

In this last section, we verify the above results by providing some examples of the LCCF for well-known probability density functions.

Example 1.

Consider the standard exponential distribution whose probability density function is given by

The LCCF of the above function is derived as follows:

In fact, we have

We write (57) as

Changing the variables , we immediately obtain

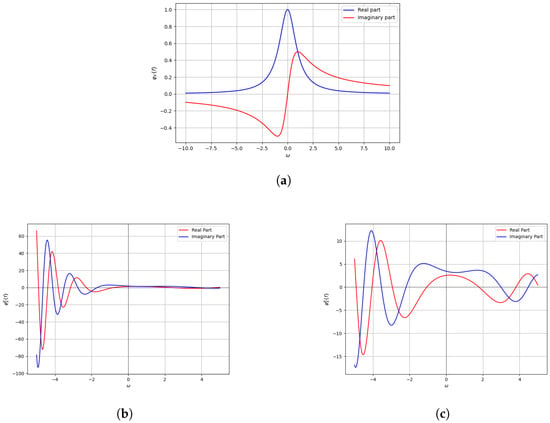

A graph of the LCCF of Relation (59) for different values, compared to the classical characteristic function in (56), is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of characteristic function and LCCF. (a) characteristic function of (56); LCCF of Example 1 with (b) , , ; (c) . This shows that the LCCF is more flexible and superior to the classical characteristic function.

Example 2.

Consider the uniform distribution given by

Its LCCF is as follows:

A simple computation shows

This equation may be further simplified to

Performing the change of variables, in Equation (62) yields

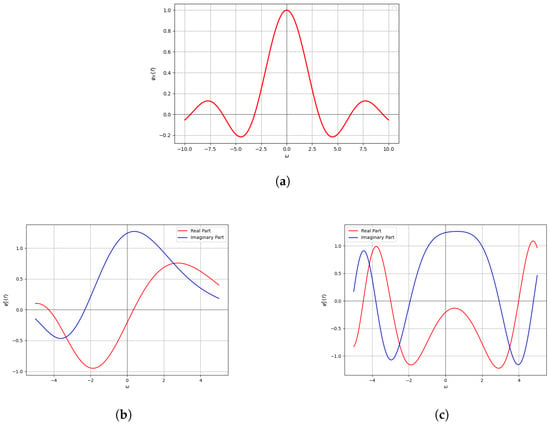

Figure 2 illustrates a comparison of the LCCF (63) with the characteristic function of (60).

Figure 2.

(a) Characteristic function of (60). LCCF of Example 2 with (b) , , ; (c) . This shows that the LCCF is more flexible and superior to the classical characteristic function.

Example 3.

Consider a Gaussian random variable with mean m and variance of the form

By virtue of Equation (13), we have

Substituting into the above expression, we get

Using the fact that

where with and . Thus, Equation (65) above leads to

This equation is simplified into

It can easily be seen that when in Expression (68), we get

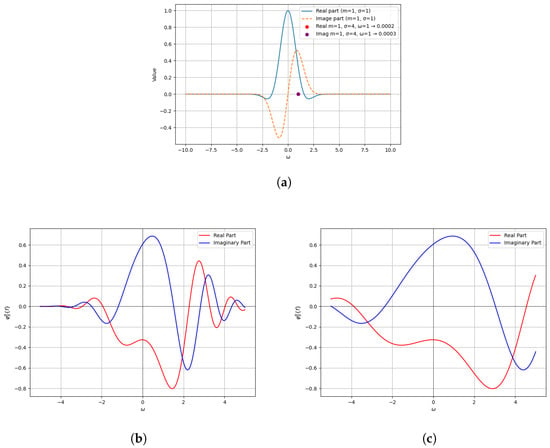

which is quite similar to the classical characteristic function of the Gaussian function [24]. Figure 3 illustrates the difference and comparison of the LCCF (68) and the characteristic function (69). These figures demonstrate that the LCCF is more flexible than the classical characteristic function.

Figure 3.

(a) Characteristic function of Example 3. The LCCF of Example 3 with (b) , ; (c) . This shows that the LCCF is more flexible and superior to the classical characteristic function.

Furthermore, we obtain

According to (43), we obtain

which is the first moment related to the LCCF of Example 3.

Furthermore, simple computations lead to

Now, observe that

By virtue of Equation (39), we have

which is the second moment related to the LCCF of Example 3. According to Equation (48), we have

In particular, when we put in Expression (74), we immediately obtain

Table 1 summarizes the results derived in Example 3.

Table 1.

Comparison of moments and variances in the LCCF domain with those in the classical case in Example 3.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we constructed the LCCF as a combination of the LCT kernel and the probability density function used in the classical characteristic function. The investigation of some original results related to the proposed LCCF was performed in detail. It was found that some crucial properties of the classical characteristic function are substantially modified in the LCCF setting. As an application, we presented some examples to verify the obtained results. Future work will extend the one-dimensional LCCF to the n-dimensional case. This approach is based on replacing the kernel of the characteristic function with an n-dimensional LCT kernel. Of course, the results of the -dimensional LCCF will change significantly in the newly constructed n-dimensional LCCF.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.; formal analysis, M.B.; funding acquisition, R.I.; investigation, R.I. and S.T.; methodology, R.I.; resources, N.B., S.T. and A.T.A.N.; validation; original draft, R.I., N.B. and S.T.; review—writing and editing, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bahri, M.; Karim, S.A.A. Fractional Fourier transform: Main properties and inequalities. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dang, P.; Mai, W. LP-type Heisenberg-Pauli-Weyl uncertainty principles for fractional Fourier transform. Appl. Math. Comput. 2025, 491, 129236. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Li, B.Z. Blind image watermarking method based on linear canonical transform and QR decomposition. IET Image Process. 2016, 10, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Singh, K.; Saxena, R. Multiplicative filtering in the linear canonical transform domain. IET Signal Process. 2016, 10, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D. Filter bank reconstruction of band-limited signals from multichannel samples associated with the LCT. IET Signal Process. 2016, 11, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejjaoli, H. Linear canonical DunklWigner transformation: Theory and Localization Operators. J.-Pseudo-Differ. Oper. Appl. 2025, 16, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, P.; Deng, G.T.; Qian, T. A tighter uncertainty principle for linear canonical transform in terms of phase derivative. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2013, 61, 5153–5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, D.; Ran, T.; Yue, W. Convolution theorems for the linear canonical transform and their application. Sci. China Ser. F Inf. Sci. 2006, 49, 592–603. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Ran, Q.; Li, Y. New convolution theorem for the linear canonical transform and its translation invariance property. Optik 2021, 123, 1478–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Li, B.Z. Convolution and correlation theorems for the two-dimensional linear canonical transform and its applications. IET Signal Process. 2016, 10, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottone, G.; Paola, M.D.; Metzler, R. Fractional calculus approach to the statistical characterization of random variables and vectors. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2010, 389, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomovski, Ž.; Ralf Metzler, R.; Gerhold, S. Fractional characteristic functions, and a fractional calculus approach for moments of random variables. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2022, 25, 1307–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, K. A note on property of the Mittag-Leffler function. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2010, 370, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaim, H.; Fahlaoui, S. General one-dimensional Clifford Fourier transform and application to probability theory. Rend. Circ. Mat. Palermo Ser. II 2024, 73, 1453–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekasasmita, W.; Bahri, M.; Bachtiar, N.; Rahim, A.; Nur, M. One-dimensional quaternion Fourier transform with application to probability theory. Symmetry 2023, 15, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurwahidah, N.; Bahri, M.; Rahim, A. Two-dimensional quaternion Fourier transform method in probability modeling. Symmetry 2024, 16, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, M.A.; Xia, Y.; Siddiqui, S.; Bhat, M.Y.; Urynbassarova, D.; Urynbassarova, A. Quaternion fractional Fourier transform: Bridging signal processing and probability theory. Mathematics 2025, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, M.A.; Xia, Y.; Siddiqui, S.; Bhat, M.Y. Two-dimensional quaternion linear canonical transform: A novel framework for probability modeling. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2025, 71, 7493–7519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Samad, M.A.; Ismoiljonovich, F.D. One dimensional quaternion linear canonical transform in probability theory. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 18, 9419–9430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Ran, Q.; Li, Y. A convolution and convolution theorem for the linear canonical transform and its application. Circuits Syst. Sig. Process. 2022, 31, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, L.; Shah, F.A. Wavelet Transforms and Their Applications; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bracewell, R. The Fourier Transform and Its Applications; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H.; Ma, Z.; Li, L. An improved complex fractional moment-based approach for the probabilistic characterization of random variables. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2018, 53, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr, A.F. Characteristic Functions. In Probability. Springer Texts in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.