Study on Microscopic Seepage Simulation of Tight Sandstone Reservoir Based on Digital Core Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

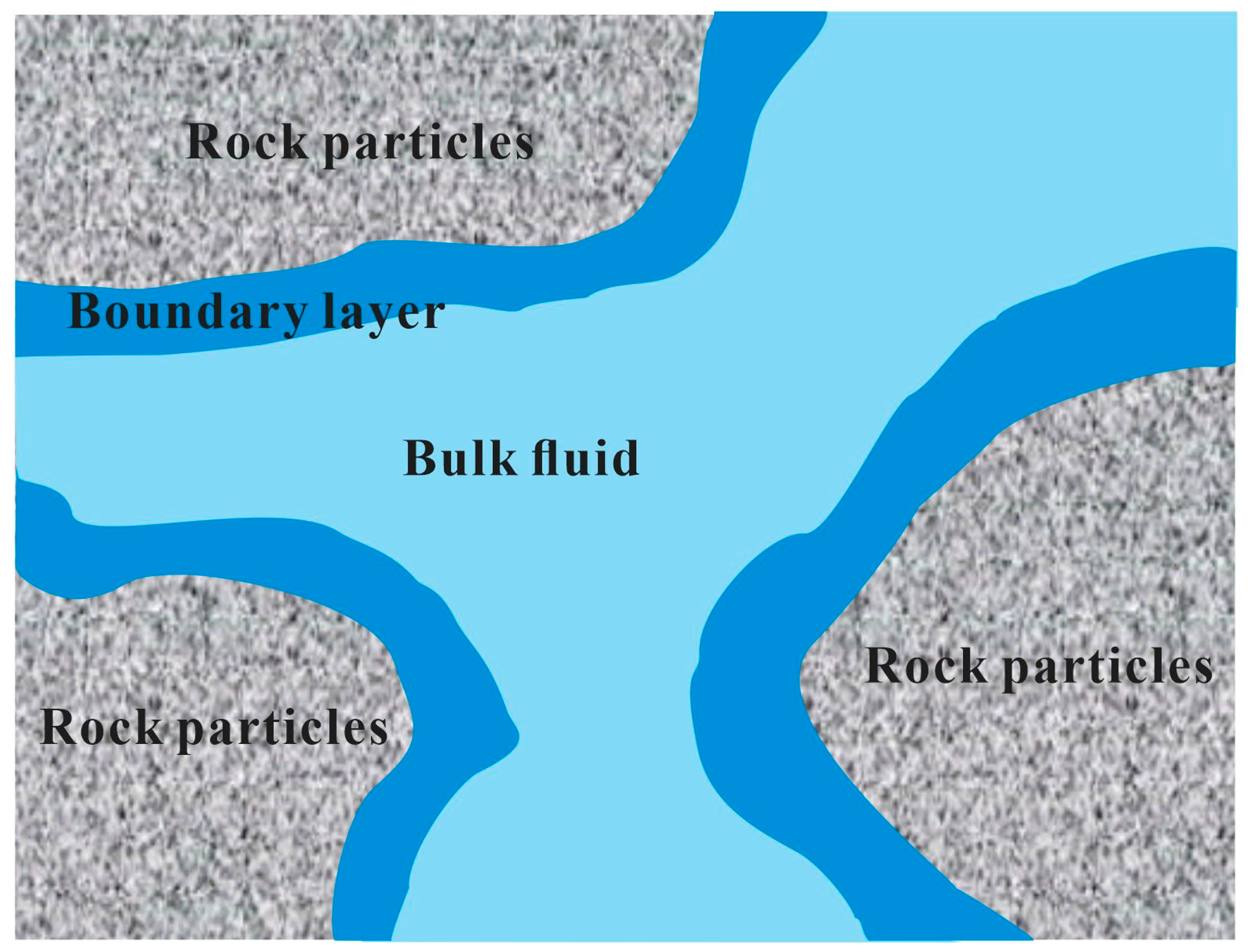

2. Calculation of Boundary Layer Thickness and Viscosity

3. Mathematical Model

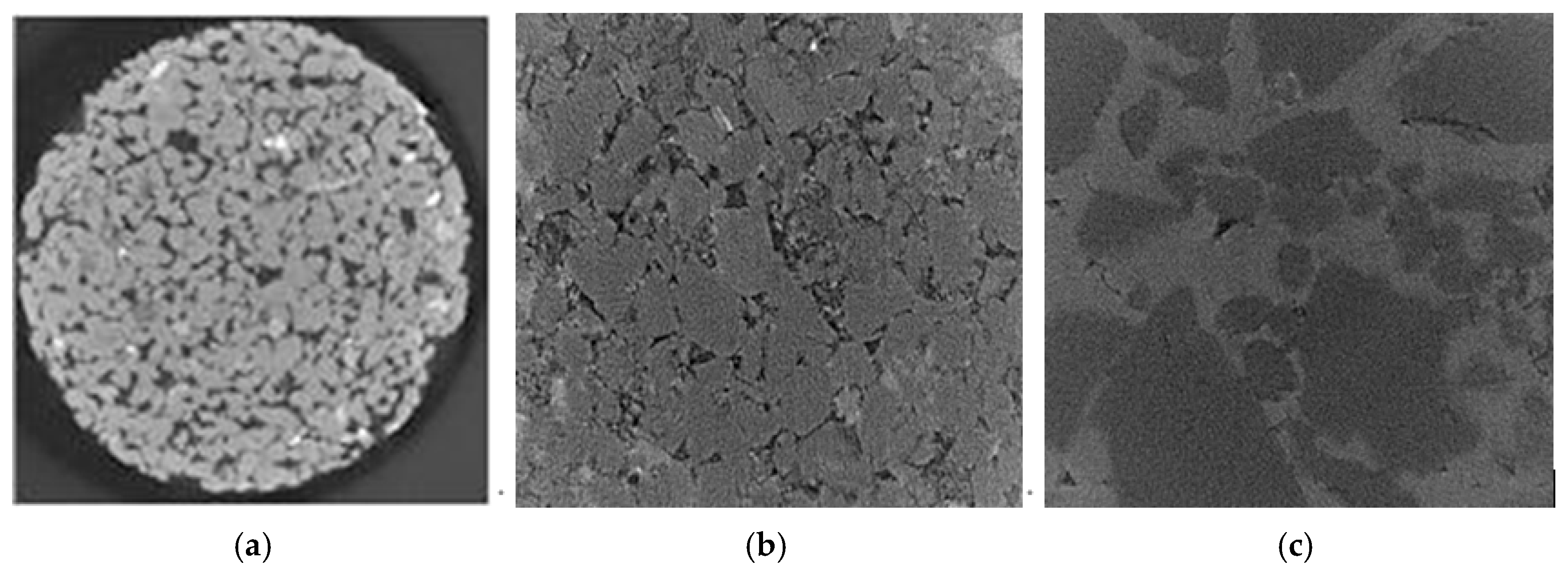

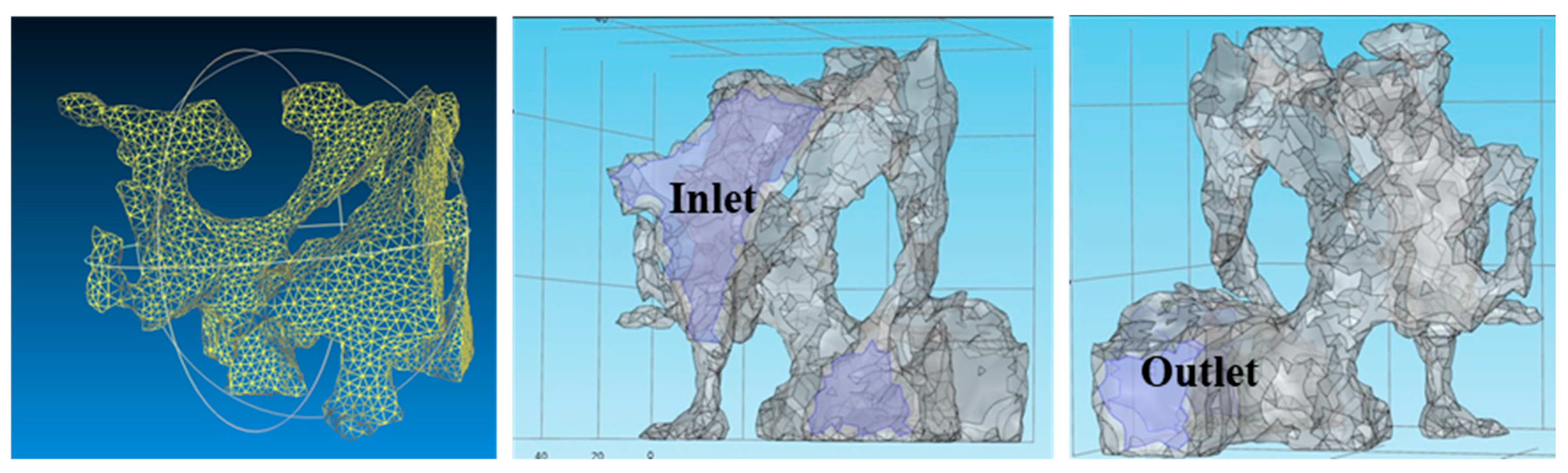

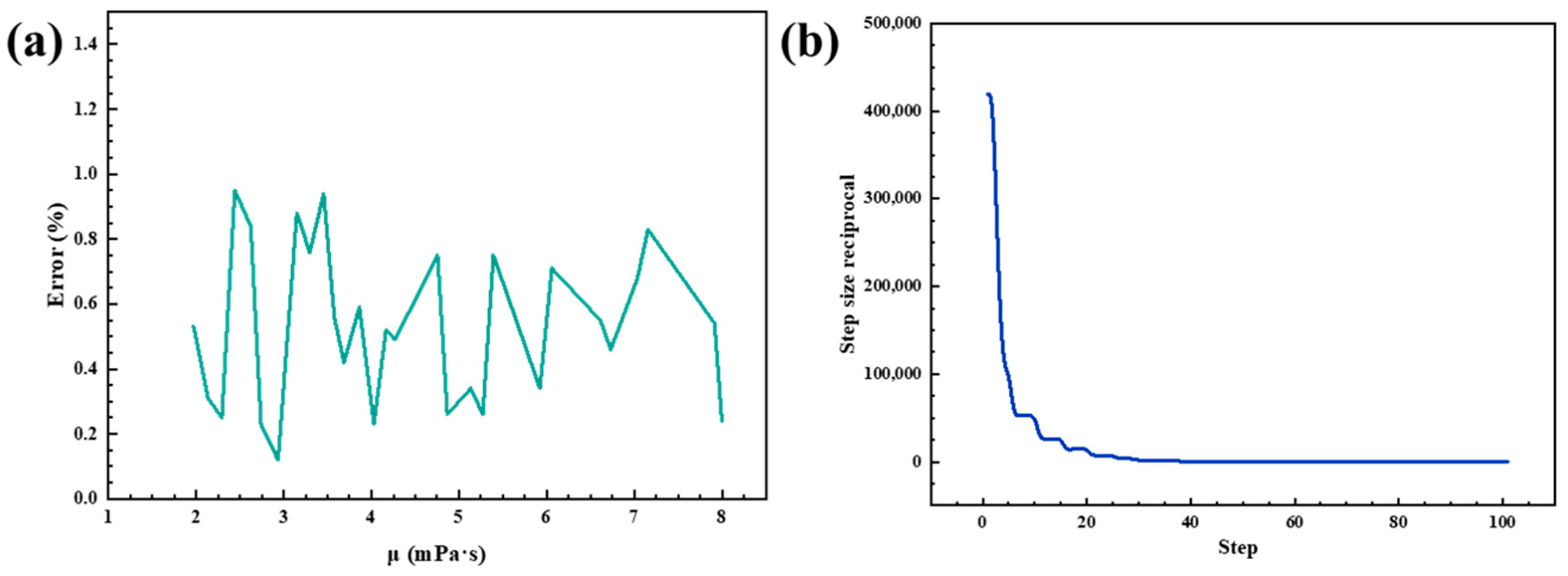

4. Construction of Pore Network Model

5. Result Analysis

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- By comparing the numerical simulation results with the theoretical calculations, the accuracy of the proposed flow model incorporating boundary layer effects was effectively validated.

- (2)

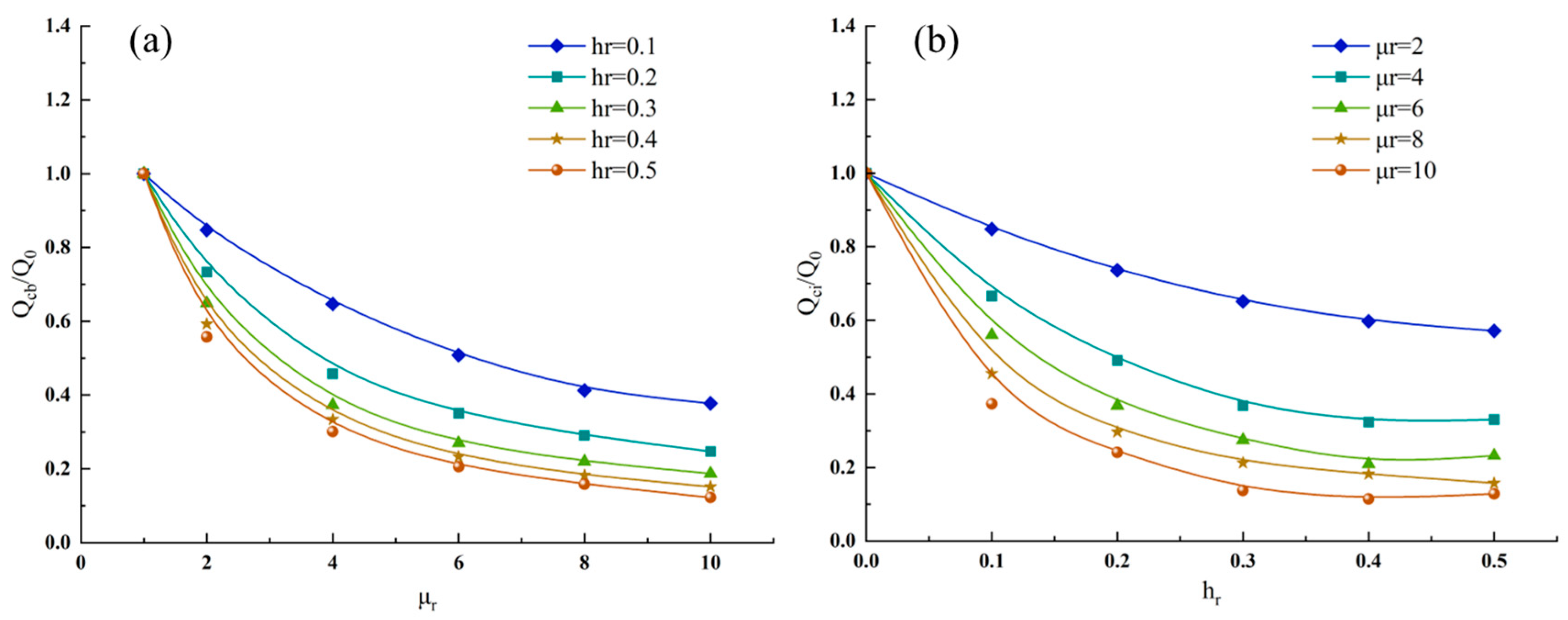

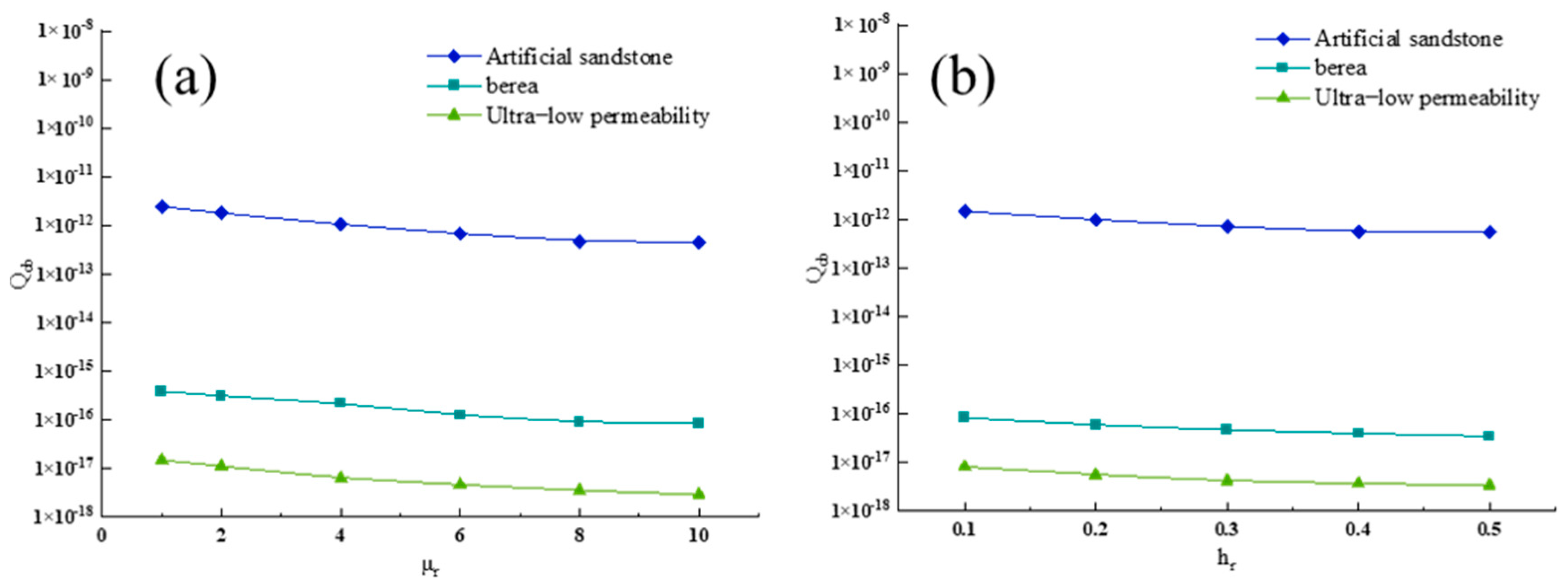

- The thickness and viscosity of the boundary layer significantly influence fluid flow in microscale pores. When the relative boundary layer thickness is 0.5, and the relative viscosity is 10, the actual flow rate at the outlet under boundary layer conditions is only 12.89% of that without considering boundary effects. Furthermore, the impact of boundary layers becomes more pronounced in tight reservoirs with smaller pore-throat dimensions.

- (3)

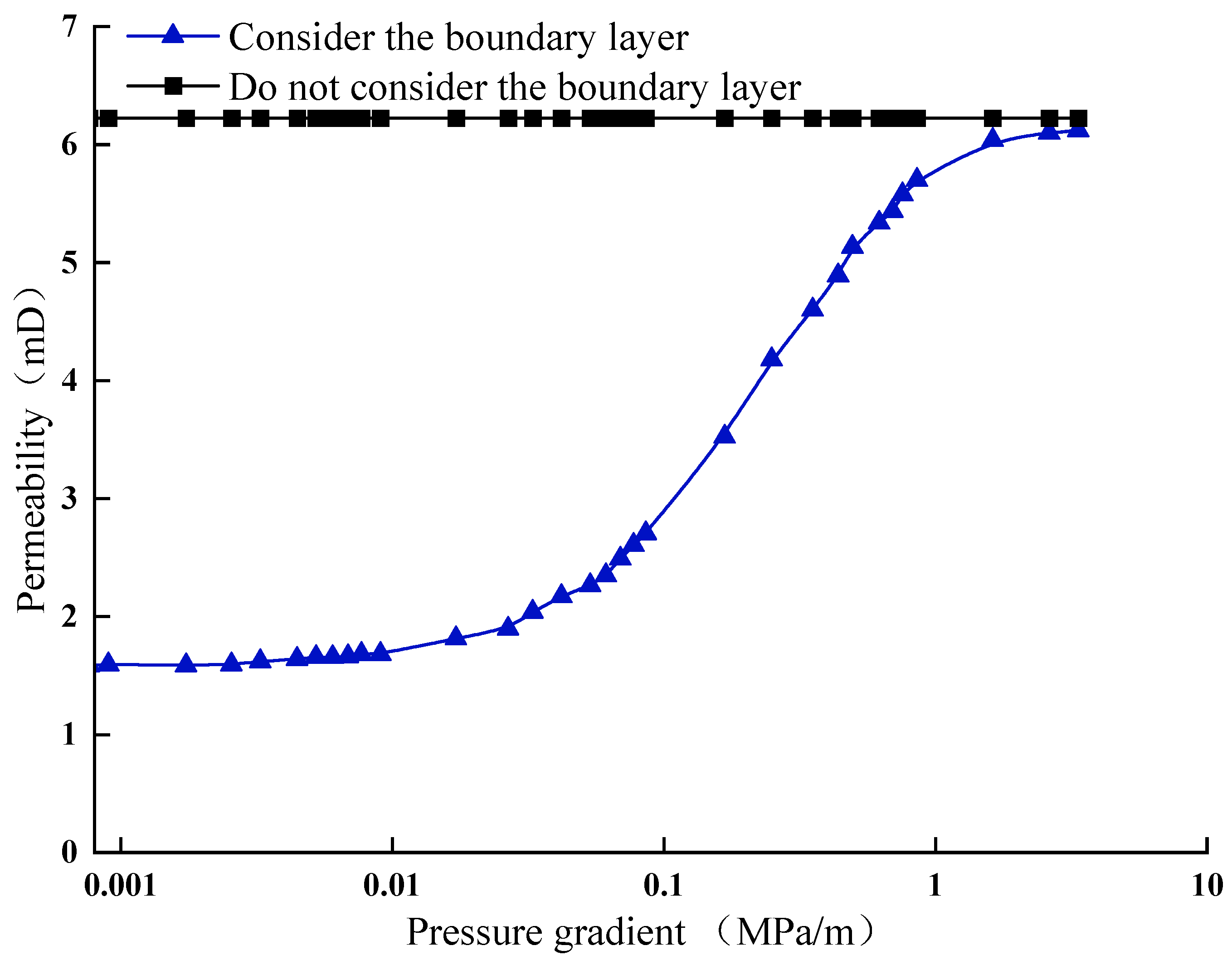

- When boundary layer effects are incorporated into the pore-scale network model, the permeability initially increases with increasing pressure gradient and then stabilizes. Under low-pressure gradients, boundary layer effects result in reduced permeability, which can negatively impact reservoir development performance.

- (4)

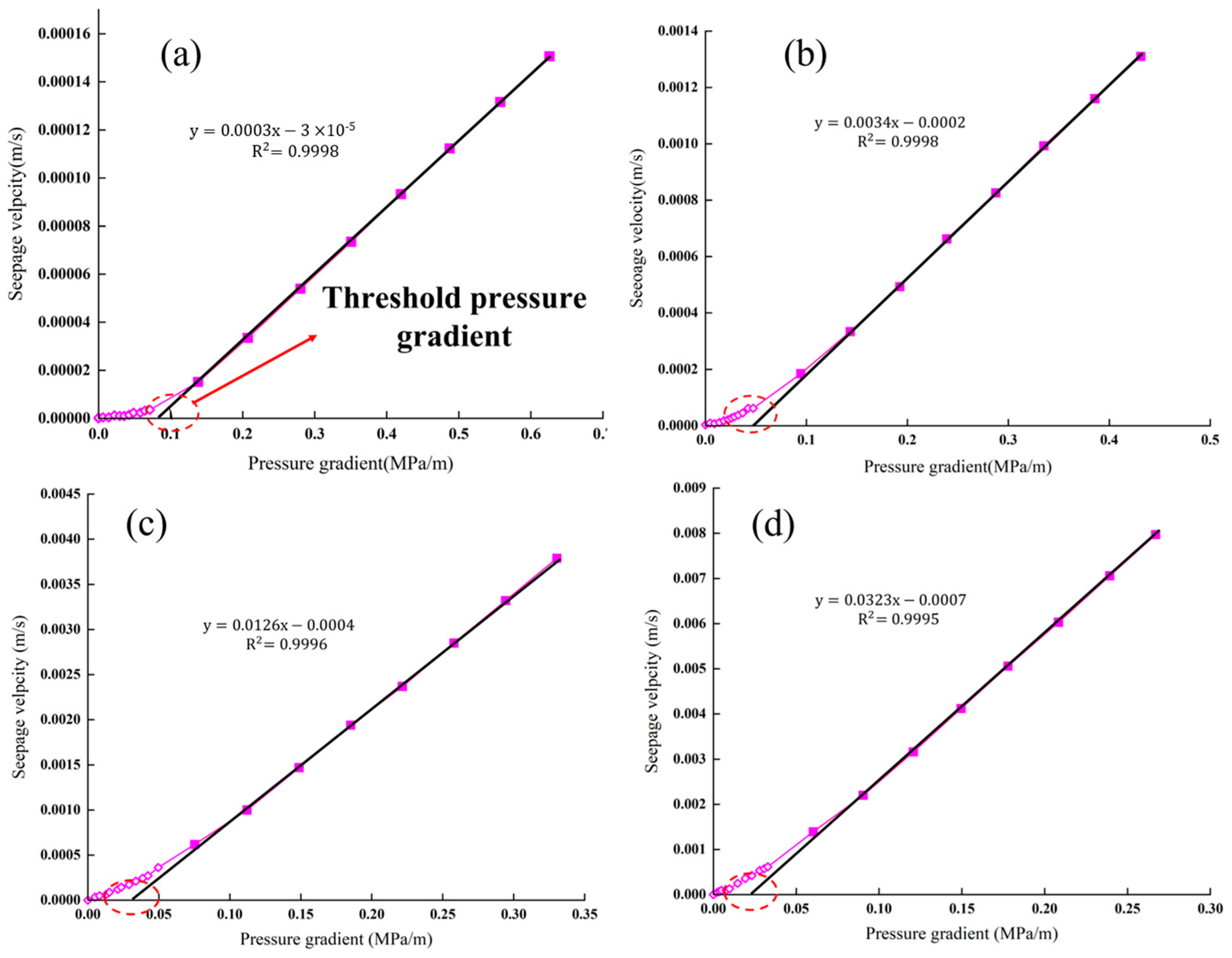

- The flow curve exhibits nonlinear behavior in the pore-scale network model when boundary layer effects are included. Under low-gradient conditions, flow velocity increases nonlinearly with pressure gradient, transitioning to linear Darcy flow only after the gradient exceeds a certain threshold. Moreover, the pore-scale network model allows the threshold pressure gradient in low-permeability media to be identified. Higher permeability corresponds to a lower threshold pressure gradient, whereas smaller pore sizes lead to more pronounced nonlinear flow behavior during the early stages of displacement.

- (5)

- It should be noted that the present study adopts fixed values of relative boundary layer thickness and viscosity, representing a static approximation of boundary layer behavior. In actual reservoir conditions, boundary layer properties may evolve dynamically with temperature, pressure gradient (shear rate), and fluid–rock interactions. Moreover, material-specific characteristics such as wettability and contact angle, which can further influence adsorption behavior and near-wall flow, were not explicitly incorporated in the current model. Future research will focus on coupling the boundary layer formulation with temperature-dependent viscosity, shear-induced evolution, and wettability effects to more accurately capture the dynamic and material-sensitive nature of boundary layer development in tight reservoirs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wenrui, H.U.; Wei, Y.; Bao, J. Development of the theory and technology for low permeability reservoirs in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, C.R.; Vahedian, A.; Ghanizadeh, A.; Song, C. A new low-permeability reservoir core analysis method based on rate- transient analysis theory. Fuel 2019, 235, 1530–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertsin, A.; Grunze, M. Water–Graphite Interaction and Behavior of Water Near the Graphite Surface. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Kang, Y.; You, L. Review of micro flow mech-anism and application in low-permeability reservoirs. Bull. Geol. Sci. Technol. 2013, 32, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Asako, Y.; Abu-Nada, E.; Krafczyk, M.; Faghri, M. From dissipative particle dynamics scales to physical scales: A coarse-graining study for water flow in microchannel. Microfluid. Nanofluidics 2009, 7, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Cheng, L.; Yan, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, W.; Guo, Q. An improved solution to estimate relative permeability in tight oil reservoirs. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2015, 5, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Wu, S.; Su, L.; Cui, J.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, X. Problems and future works of porous texture characterization of tight reservoirs in China. Acta Pet. Sin. 2016, 37, 1323. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Hou, X.; Hao, M.; Yang, T. Pressure transient analysis in low-permeable media with threshold gradients. Acta Pet. Sin. 2011, 32, 847–851. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.J.; Liu, S.B.; Jiang, L.; Yuan, X.J.; Tao, S.Z. Experimental Study of Seepage Characteristic and Mechanism in Tight Gas Sands: A Case from Xujiahe Reservoir of Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2014, 25, 804–809. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.; Zou, C.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Zheng, M. Assessment criteria, main types, basic features and resource prospects of the tight oil in China. Acta Pet. Sin. 2012, 33, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Miao, Z.; Song, Y. Modeling on non-Darcy phenomena of gas flow in tight porous media using Lattice Boltzmann method. J. Liaoning Tech. Univ. 2010, 29, 412–415. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y. Risk Prediction of Gas Hydrate Formation in the Wellbore and Subsea Gathering System of Deep-Water Turbidite Reservoirs: Case Analysis from the South China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, C.; Dou, J. Effects of Crosslinking Agents and Reservoir Conditions on the Propagation of Fractures in Coal Reservoirs During Hydraulic Fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ansari, U. From CO2 Sequestration to Hydrogen Storage: Further Utilization of Depleted Gas Reservoirs. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Lei, Q.; Zhou, T.; He, Y.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Yao, L.; Huang, Q. Study on effect of viscosity on thickness of boundary layer in tight reservoir. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 231, 212311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zeng, J.; Zhan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, J.; Feng, S. Influence of Boundary Layer on Oil Migration into Tight Reservoirs. Transp. Porous Media 2021, 137, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Sui, Y.; Cheng, X.; Ye, Y.; Wang, Z. Numerical Simulation of Low-Permeability Reservoirs with considering the Dynamic Boundary Layer Effect. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Du, M.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y. Research on Mathematical Model of Shale Oil Reservoir Flow. Energies 2023, 16, 5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xing, J.; Jiang, D.; Shang, L.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, J. A Fractal Model of Low-Velocity Non-Darcy Flow Considering Viscosity Distribution and Boundary Layer Effect. Fractals 2022, 30, 2250006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.L.; Yue, X.A.; Hou, J.R.; Wang, B.X. Influence of boundary-layer fluid on the seepage characteristic of low-permeability reservoir. J. Xian Shiyou Univ. 2007, 22, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Sheng, J.J. Effect of low-velocity non-Darcy flow on well production performance in shale and tight oil reservoirs. Fuel 2017, 190, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.X.; Yue, X.A.; Hou, J.R.; Cao, J.B.; Wang, L.M. Experimental study of adsorbed water layer on solid particle surface. Acta Mineral. Sin. 2005, 25, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; You, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Ding, X.; Jiang, Y. Characteristics of boundary layer under microscale flow and regulation mechanism of nanomaterials on boundary layer. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 368, 120616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Research on Boundary Layer Effect in Fractured Reservoirs Based on Pore-Scale Models. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 797617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, H.; Li, H.; Liu, W.; Jiang, B.; Hua, J. Thickness analysis of bound water film in tight reservoir. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2015, 26, 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Du, D.; Chen, H.; Zhang, C. Simulation of Evolution Mechanism of Dynamic Interface of Aqueous Foam in Narrow Space Base on Level Set Method. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 574, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammad, M.J.; Alam, J.M.; Rahman, M.A.; Butt, S.D. Numerical simulation of two-phase flow in porous media using a wavelet based phase-field method. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 173, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambekar, A.S.; Mattey, P.; Buwa, V.V. Pore-resolved two-phase flow in a pseudo-3D porous medium: Measurements and volume-of-fluid simulations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 230, 116128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Cheng, L.; Cao, R.; An, N.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Characteristics of Boundary Layer in Micro and Nano Throats of Tight Sandstone Oil Reservoirs. Chin. J. Comput. Phys. 2016, 33, 717. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.L.; Yue, X.A. Experimental research on nonlinear flow characteristics at low velocity. J. China Univ. Pet. 2007, 31, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | Berea Sandstone | 116-C | Standard Artificial Sandstone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porosity, % | 19.6 | 17.0 | 57.2 |

| Permeability in the X direction, mD | 1360 | 1.05 | / |

| Permeability in the Y direction, mD | 1304 | 1.30 | / |

| Permeability in the Z direction, mD | 1193 | 0.51 | / |

| Average permeability, mD | 1286 | 0.91 | 156,135 |

| μr | hr | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| μ (mPa·s) | ||||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 1.36 | 1.51 | 1.64 | 1.75 |

| 4 | 1.00 | 1.57 | 2.08 | 2.53 | 2.92 | 3.25 |

| 6 | 1.00 | 1.95 | 2.80 | 3.55 | 4.20 | 4.75 |

| 8 | 1.00 | 2.33 | 3.52 | 4.57 | 5.48 | 6.25 |

| 10 | 1.00 | 2.71 | 4.24 | 5.59 | 6.76 | 7.75 |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of pores | 20 × 20 × 20 |

| Number of pores and throats | 16,448 |

| Average coordination number | 4 |

| Maximum pore throat radius, µm | 2 |

| Minimum pore throat radius, µm | 0.2 |

| Pore throat ratio | 1.0–5.0 |

| Absolute permeability, mD | 6.27 |

| Porosity, % | 15.07 |

| Parameters | Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Model relative size (number of pores in each direction) | 20 × 20 × 20 | 20 × 20 × 20 | 20 × 20 × 20 | 20 × 20 × 20 |

| Absolute size of the model (mm × mm× mm) | 0.18 × 0.18 × 0.18 | 0.26 × 0.26 × 0.26 | 0.34 × 0.34 × 0.34 | 0.42 × 0.42 × 0.42 |

| Pore radius, μm | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| Pore throat radius, μm | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Pore throat ratio | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Absolute permeability, mD | 0.286185 | 3.22876 | 12.409 | 32.313 |

| Porosity, % | 8.0 | 21.95 | 32.32 | 40.142 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Cao, X.; Du, L. Study on Microscopic Seepage Simulation of Tight Sandstone Reservoir Based on Digital Core Technology. Eng 2026, 7, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010025

Chen H, Cao X, Du L. Study on Microscopic Seepage Simulation of Tight Sandstone Reservoir Based on Digital Core Technology. Eng. 2026; 7(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Hui, Xiaopeng Cao, and Lin Du. 2026. "Study on Microscopic Seepage Simulation of Tight Sandstone Reservoir Based on Digital Core Technology" Eng 7, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010025

APA StyleChen, H., Cao, X., & Du, L. (2026). Study on Microscopic Seepage Simulation of Tight Sandstone Reservoir Based on Digital Core Technology. Eng, 7(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010025