Hybrid Optimization of Hardfacing Conditions and the Content of Exothermic Additions in the Core Filler During the Flux-Cored Arc Welding Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review: Use of Exothermic Additives in Flux-Cored Wires

1.2. Literature Review of Methods for Optimizing Welding Processes with Multiple Output Parameters

1.3. Contribution and Organization

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Statistical Evaluation

2.1.1. Taguchi’s Design of Experiment

2.1.2. Grey Relational Analysis

2.1.3. Principal Component Analysis

2.2. Materials

2.3. Hardfacing Procedure

2.4. Calculation Method for Melting Characteristics

3. Results

3.1. Melting Characteristics

3.1.1. Experiment Results for Melting Characteristics

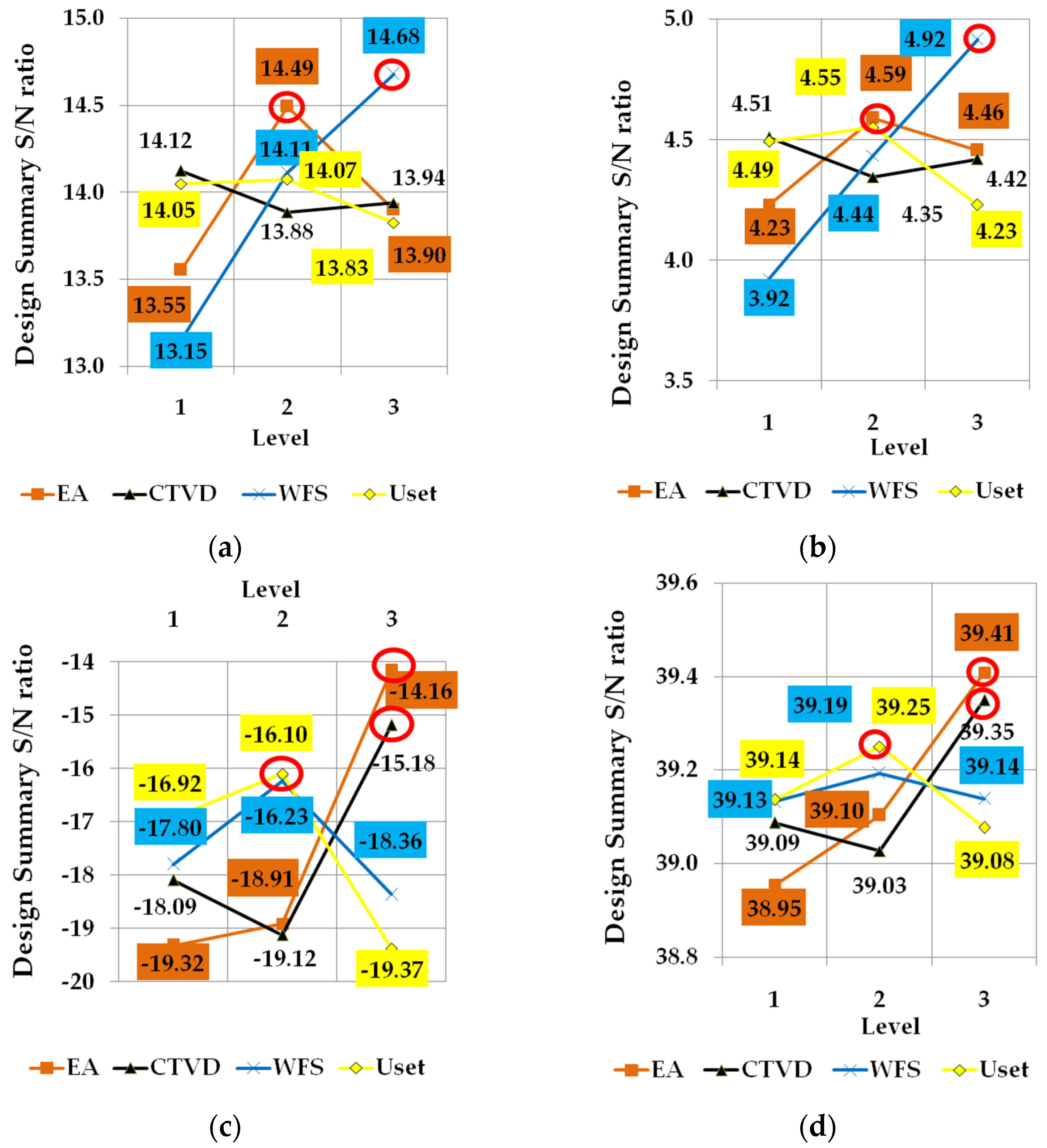

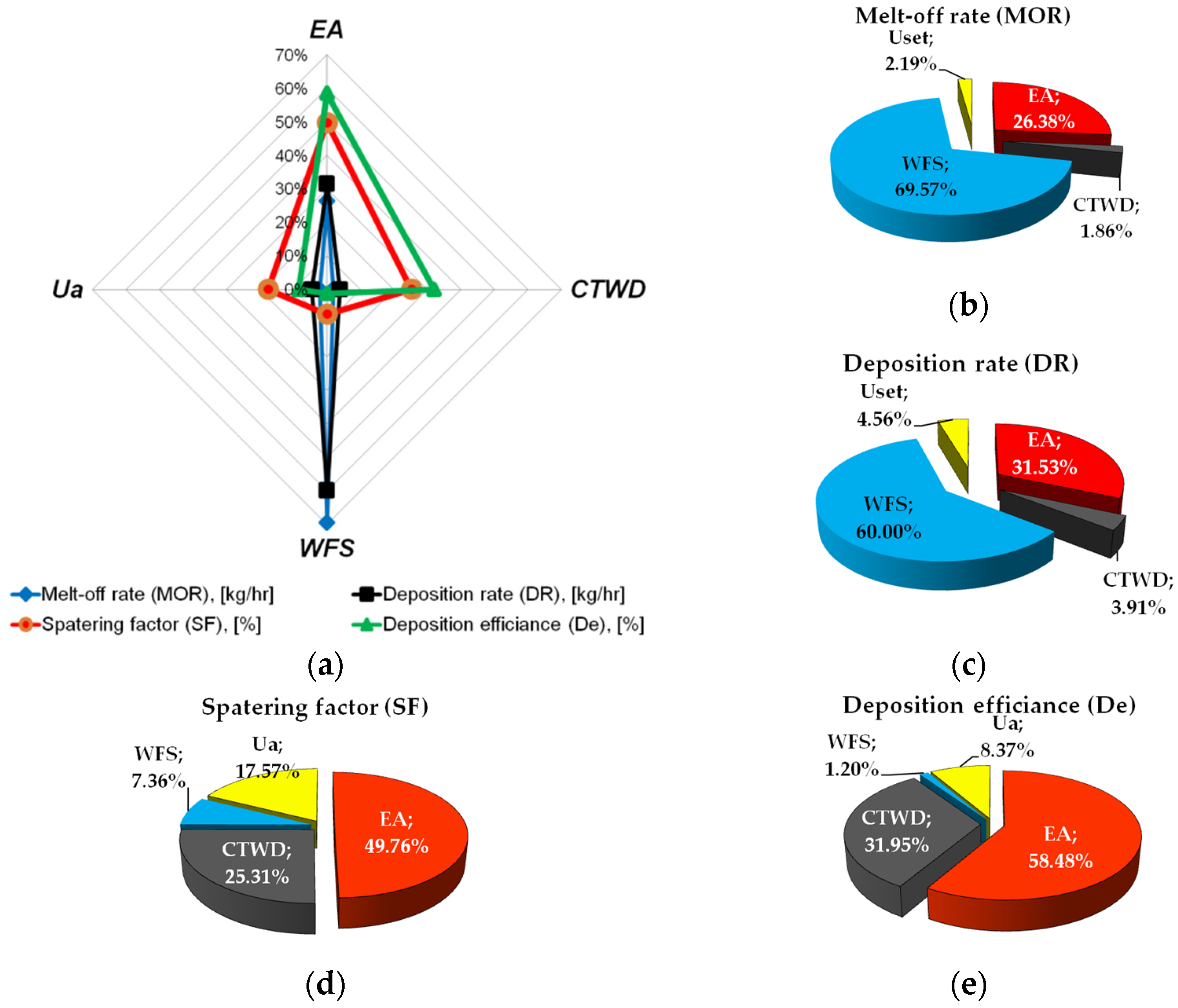

3.1.2. Taguchi Method and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for Melting Characteristics

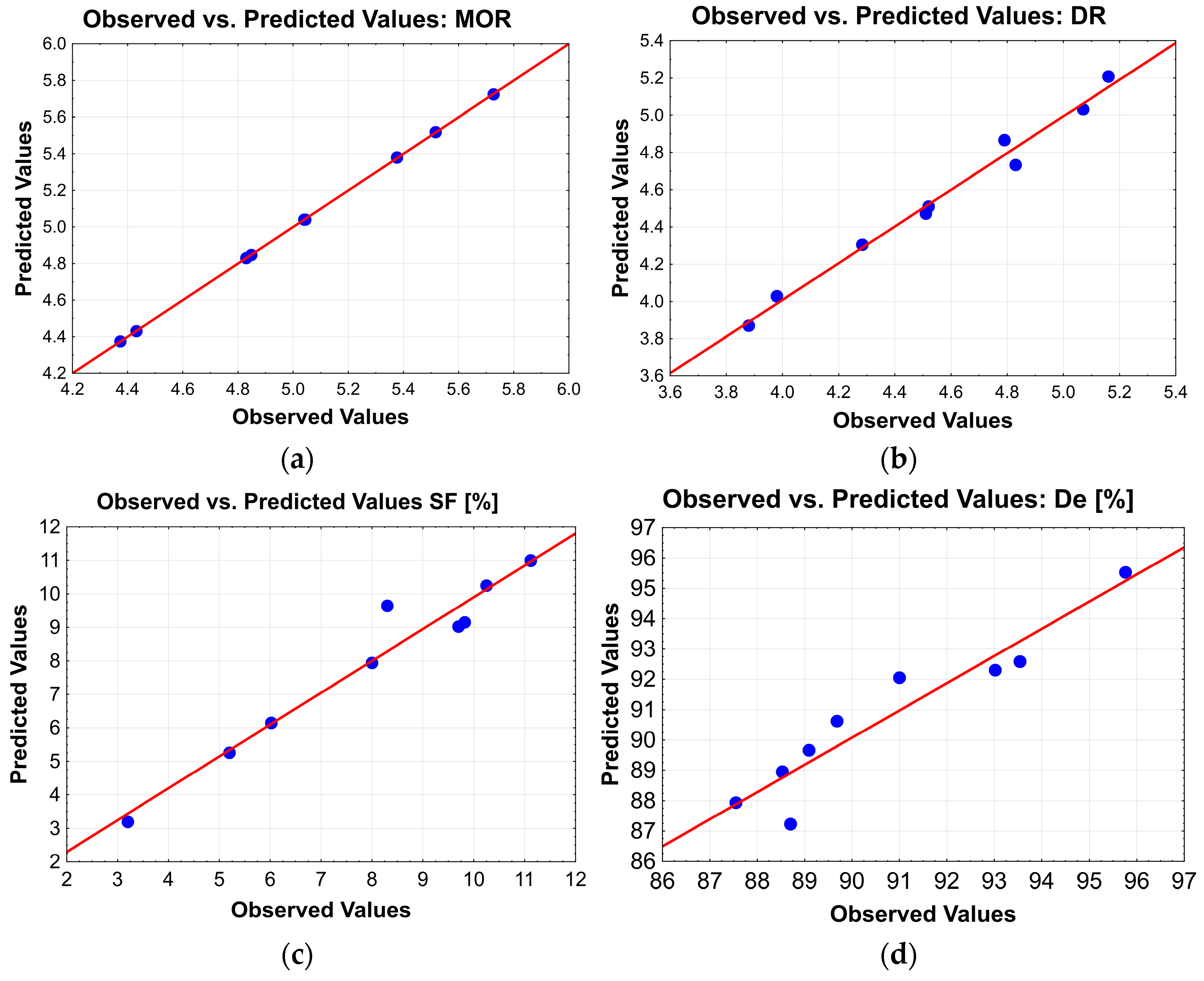

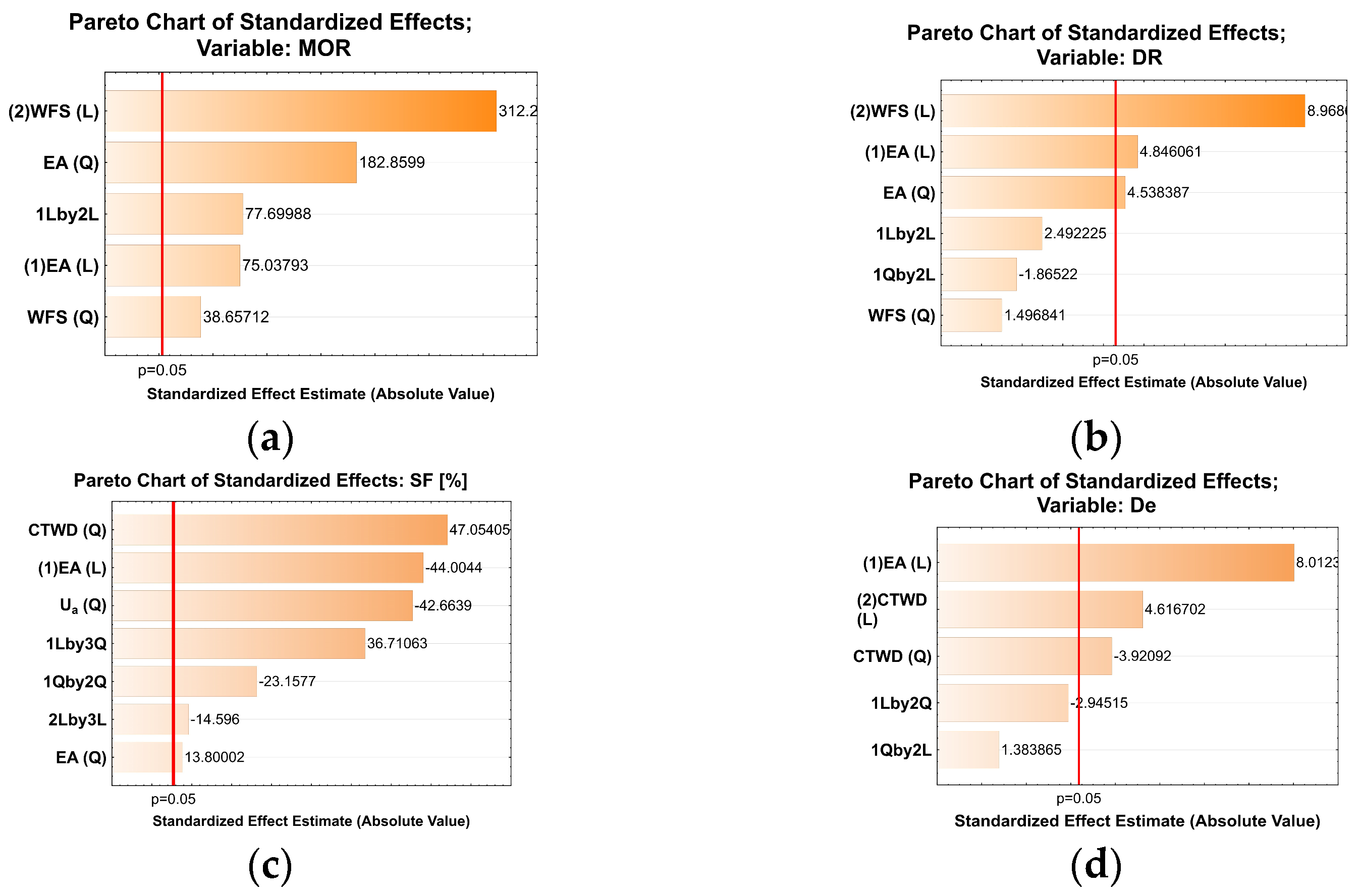

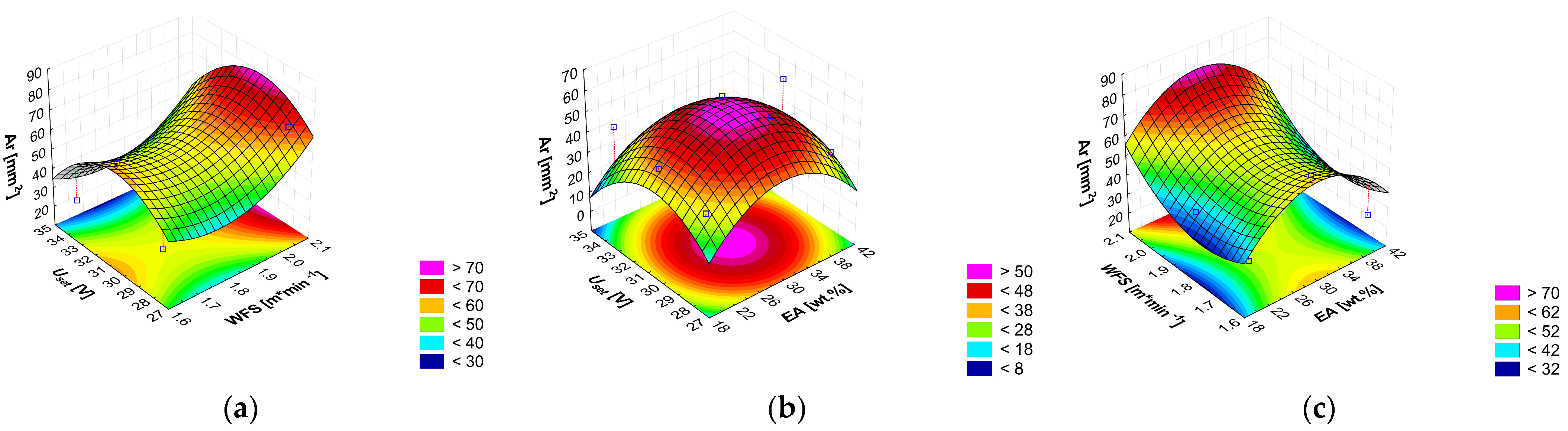

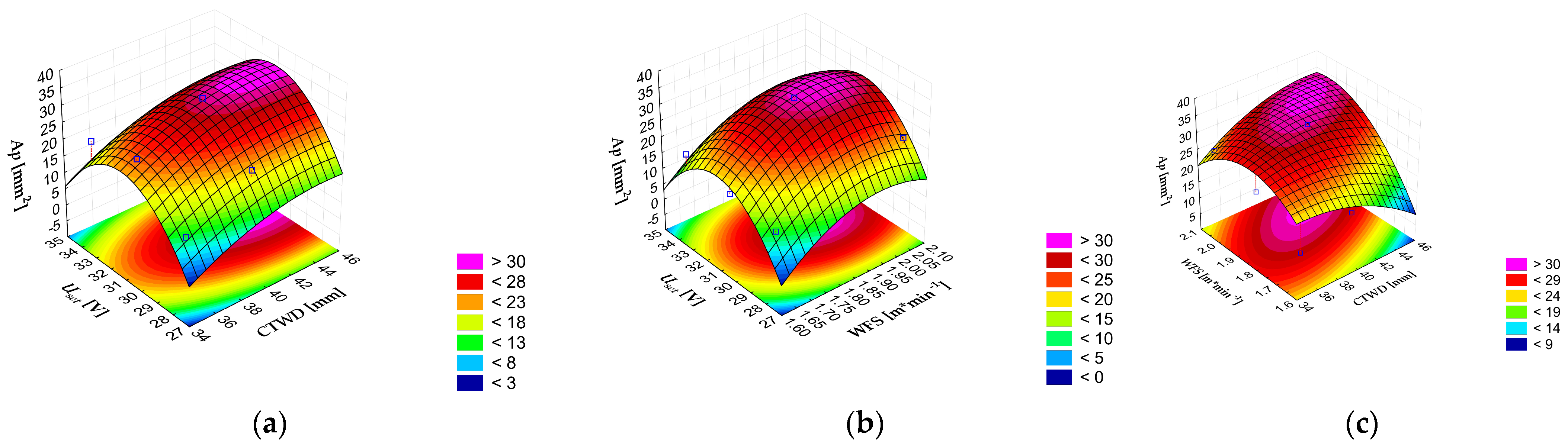

3.1.3. Factorial Design Analysis of Melting Characteristics

3.2. Weld Bead Morphology

3.2.1. Experiment Results for Weld Bead Morphology

3.2.2. Taguchi Method and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for Weld Bead Morphology

3.2.3. Factorial Design Analysis of Weld Bead Morphology

3.3. Taguchi–Grey Relational Analysis Coupled with Principal Component Analysis

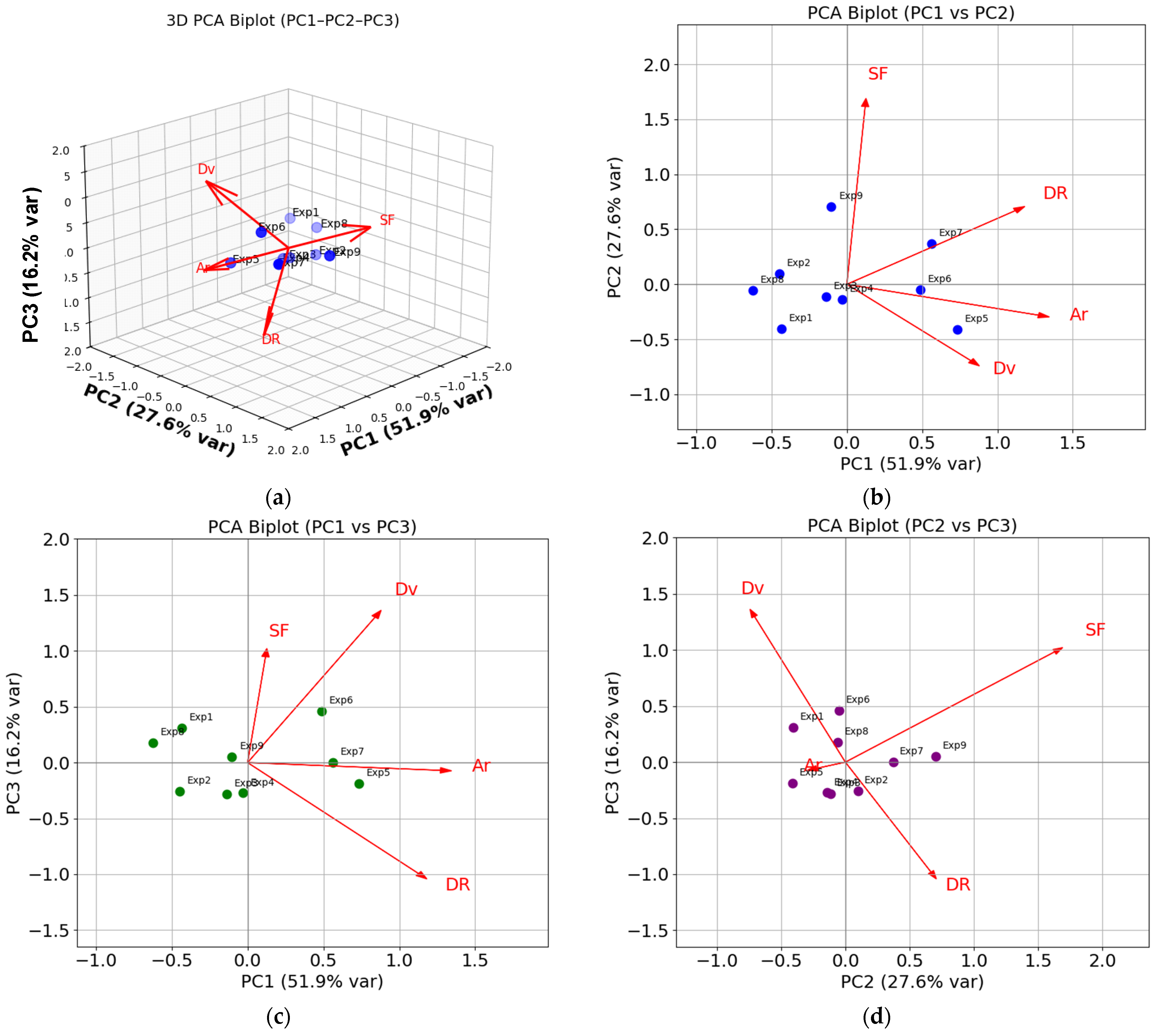

3.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GRA | Grey Relational Analysis |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| FCAW | Flux-Cored Arc Welding |

| WFS | Wire feed speed |

| CTWD | Contact tip-to-work distance |

| EA | Percentage of exothermic mixture in the core filler |

| MOR | Melting-off rate |

| DR | Deposition rate |

| SF | Spattering factor |

| De | Deposition efficiency |

| R sqr | Coefficient of Determination |

| R Adj | Adjusted Sum of Squares |

| WB | Width of bead |

| THR | Top height of reinforcement |

| DP | Bottom depth of penetration |

| Ar | Cross-sectional area of reinforcement |

| Ap | Cross-sectional area of penetration |

| Dv | Dilution variation |

References

- Bannikov, D.; Tiutkin, O.; Hezentsvei, Y.; Muntian, A. Controlling the dynamic characteristics of steel bunker containers for bulk materials. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; Volume 1348, p. 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembenek, M.; Mandziy, T.; Ivasenko, I.; Berehulyak, O.; Vorobel, R.; Slobodyan, Z.; Ropyak, L. Multiclass Level-Set Segmentation of Rust and Coating Damages in Images of Metal Structures. Sensors 2022, 22, 7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krol, O.; Sokolov, V.; Stanciu, D.I. Structural and Parametric Identification of Mathematical Models of HVAC Systems. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Proceedings of the International Conference on Reliable Systems Engineering (ICoRSE)—2025, Bucharest, Romania, 4–5 September 2025; Cioboată, D.D., Machado, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratov, B.; Mechnik, V.A.; Rucki, M.; Hevorkian, E.; Bondarenko, N.; Prikhna, T.; Moshchil, V.E.; Kolodnitskyi, V.; Morozow, D.; Gusmanova, A.; et al. Enhancement of the Refractory Matrix Diamond-Reinforced Cutting Tool Composite with Zirconia Nano-Additive. Materials 2024, 17, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, D.; Psuj, G.; Bartkowski, D.; Bartkowska, A. Assessment of Coating Properties in Car Body by Ultrasonic Method. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekiač, J.J.; Krbata, M.; Kohutiar, M.; Janík, R.; Kakošová, L.; Breznická, A.; Eckert, M.; Mikuš, P. Comprehensive Review: Optimization of Epoxy Composites, Mechanical Properties, & Technological Trends. Polymers 2025, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, K.M.M.; Brasil, R.M.L.R.F.; Wahrhaftig, A.M.; Siqueira, G.H.; Bondarenko, I.; Neduzha, L. Influence of Atmospheric Humidity on the Critical Buckling Load of Reinforced Concrete Columns. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2022, 22, 2250011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannikov, D.O.; Tiutkin, O.L. Prospective directions of the development of loose medium mechanics. Sci. Innov. 2020, 16, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruš, P.; Barényi, I.; Majerík, J.; Krbata, M.; Kohutiar, M.; Kovaříková, I.; Bilka, M. Impact of Heat Treatment on Microstructure Evolution in Grey Cast Iron EN-GJL-300. Metals 2025, 15, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myamlin, S.; Neduzha, L.; Urbutis, Ž. Research of Innovations of Diesel Locomotives and Bogies. Procedia Eng. 2016, 134, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myamlin, S.; Lunys, O.; Neduzha, L.; Kyryl’chuk, O. Mathematical modeling of dynamic loading of cassette bearings for freight cars. In Proceedings of the 21st International Scientific Conference Transport Means, Juodkrante, Lithuania, 20–22 September 2017; pp. 973–976. [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko, I.; Lunys, O.; Neduzha, L.; Keršys, R. Dynamic track irregularities modeling when studying rolling stock dynamics. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Scientific Conference Transport Means, Palanga, Lithuania, 2–4 October 2019; pp. 1014–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko, I.; Lukoševičius, V.; Keršys, R.; Neduzha, L. Investigation of Dynamic Processes of Rolling Stock–Track Interaction: Experimental Realization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawczuk, W.; Cañás, A.M.R.; Ulbrich, D.; Kowalczyk, J. Modeling the Average and Instantaneous Friction Coefficient of a Disc Brake on the Basis of Bench Tests. Materials 2021, 14, 4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazev, S.; Rebrova, R.; Riumin, V.; Nikichanov, V.; Rebrova, A. Establishment of structure and operational properties of borated layers on 40X steel obtained from paste by induction heating. Funct. Mater. 2021, 28, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romek, D.; Selech, J.; Ulbrich, D. Use of Heat-Applied Coatings to Reduce Wear on Agricultural Machinery Components. Materials 2024, 17, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolovskij, E.; Žuraulis, V. Advances in Vehicle Dynamics and Road Safety: Technologies, Simulations, and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalivoda, J.; Neduzha, L. Running Dynamics of Rail Vehicles. Energies 2022, 15, 5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenko, Y.; Zelenko, D.; Neduzha, L. Contemporary principles for solving the problem in noise reduction from railway rolling stock. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 985, p. 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropyak, L.Y.; Velychkovych, A.S.; Vytvytskyi, V.S.; Shovkoplias, M.V. Analytical study of “crosshead—Slider ail” wear effect on pumprod stress state. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1741, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efremenko, V.G.; Chbak, Y.; Fedun, V.I.; Shimizu, K.; Pastukhova, T.V.; Petryshynets, I.; Zusin, A.M.; Kudinova, E.V.; Efremenko, B.V. Formation mechanism, microstructural features and dry-sliding behaviour of “Bronze/WC carbide” composite synthesised by atmospheric pulsed-plasma deposition. Vacuum 2021, 185, 110031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlushkova, D.B.; Bagrov, V.A.; Saenko, V.A.; Volchuk, V.M.; Kalinin, A.V.; Kalinina, N.E. Study of wear of the buiding-up zone of martensite-austenitic and secondary hardening steels of the Cr-Mn-Ti system. Probl. At. Sci. Technol. 2023, 144, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetsee, T.; De Bruin, F.J. Thermochemical analysis of the behaviour of Cu in Ti nano-strand formation from low-temperature reaction of Al-Fe-Cu powder with CaF2-SiO2-Al2O3-MgO-MnO-TiO2 flux. Chem. Thermodyn. Therm. Anal. 2025, 17, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetsee, T.; De Bruin, F. A Review of the Thermochemical Behaviour of Fluxes in Submerged Arc Welding: Modelling of Gas Phase Reactions. Processes 2023, 11, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhova, O.V. Mechanical and corrosion properties of Fe–B–C alloys. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerczyńska, A.; Varbai, B.; Pandey, C.; Fydrych, D. Exploring the trends in flux-cored arc welding: Scientometric analysis approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 130, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, A.; Świerczyńska, A.; Lentka, G.; Fydrych, D. Storage of high-strength steel flux-cored welding wires in urbanized areas. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green. Technol. 2024, 11, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembach, B.; Starikov, V.; Sukov, M.G.; Zharikov, S.; Kabatskyi, O.; Ivanova, Y. Application of mixture design in optimization of physical properties of slag during self-shielded flux-cored wire arc welding process. In Proceedings of the IEEE 5th International Conference on Modern Electrical and Energy System (MEES), Kremenchuk, Ukraine, 27–30 September 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Assunção, E.; Pires, I. Study of a hardfacing flux-cored wire for arc directed energy deposition applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 118, 3431–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerczyńska, A. Long-term storage of rutile flux-cored wires in shipyard environment. Ships Offshore Struct. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerczyńska, A.; Bet, J.; Gorgol, M.; Wolski, A. Effect of rewinding on flux-cored welding wires. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, J.G.; Moreno, A.M.; Ribeiro, P.H.; Arias, A.R.; Bracarense, A.Q. Formation of TiC by the application of Ti6Al4V machining chips as flux compounds of tubular wires. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1126, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozynskyi, V.; Trembach, B.; Hossain, M.M.; Kabir, M.H.; Silchenko, Y.; Krbata, M.; Sadovyi, K.; Kolomiitse, O.; Ropyak, L. Prediction of phase composition and mechanical properties Fe–Cr–C–B–Ti–Cu hardfacing alloys: Modeling and experimental validations. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembenek, M.; Prysyazhnyuk, P.; Shihab, T.; Machnik, R.; Ivanov, O.; Ropyak, L. Microstructure and Wear Characterization of the Fe-Mo-B-C-Based Hardfacing Alloys Deposited by Flux-Cored Arc Welding. Materials 2022, 15, 5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhova, O.V. Structure and properties of Fe–B–C powders alloyed with Cr, V, Mo or Nb for plasma-sprayed coatings. Probl. At. Sci. Technol. 2020, 4, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, C.; Hu, J.; Han, K.; Wang, Z.; Yang, R.; Liu, D. Underwater wet welding of high-strength low-alloy steel using self-shielded flux-cored wire with highly exothermic Al/CuO mixture. J. Mater. Process Technol. 2024, 328, 118404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L.; Liu, D.; Guo, N.; Chena, H.; Dua, Y.P.; Feng, J.C. The effect of alumino-thermic addition on underwater wet welding process stability. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 245, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, I.A.; Grin, A.G. Effect of the surface condition of fluxed-cored wires on the stability of the arc process. Weld. Int. 2015, 29, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharikov, S.V.; Grin, A.G. Investigation of slags in surfacing with exothermic flux-cored wires. Weld. Int. 2015, 29, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, J.; Patel, V.K.; Srinivasan, S.; Chaudhari, R.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Giasin, K.; Sharma, S. Optimization of Activated Tungsten Inert Gas Welding Process Parameters Using Heat Transfer Search Algorithm: With Experimental Validation Using Case Studies. Metals 2021, 11, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binande, P.; Shahverdi, H.R.; Farnia, A. Study on the effect of flux composition on the melting efficiency of A-TIG of AISI 316L stainless steel: Experimental and analytical approaches. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 9092–9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetsee, T.; De Bruin, F. Sodium-Oxide Fluxed Aluminothermic Reduction of Manganese Ore for a Circular Economy: Cr Collector Metal Application. Sustain. Chem. 2025, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasov, A.F.; Makarenko, N.A.; Kushchiy, A.M. Using exothermic mixtures in manual arc welding and electroslag processes. Weld. Int. 2017, 31, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasov, A.F.; Makarenko, N.A. Special features of heating and melting electrodes with an exothermic mixture in the coating. Weld. Int. 2016, 30, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.W.; Olson, D.L.; Frost, R.H. Exothermically assisted shielded metal arc welding. Weld. J. 1998, 77, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, K. Development of exothermic flux for enhanced penetration in submerged arc welding. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 19, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, H.; Hu, C.; Wang, Z.; Han, K.; Liu, D.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Q. The Efficiency of Thermite-Assisted Underwater Wet Flux-Cored Arc Welding Process: Electrical Dependence, Microstructural Changes, and Mechanical Properties. Metals 2023, 13, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembach, B.; Trembach, I.; Grin, A.; Makarenko, N.; Babych, O.; Knyazev, S.; Musairova, Y.; Krbata, M.; Balenko, O.; Vorobiov, O.; et al. Study of the Effects of Hardfacing Modes Carried out by FCAW-S with Exothermic Addition of MnO2-Al on Non-Metallic Inclusions, Grain Size, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Eng 2025, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, H.; Yan, Y.; Guo, N.; Song, X.; Feng, J. Effects of processing parameters on arc stability and cutting quality in underwater wet flux-cored arc cutting at shallow water. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 33, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, X.; Zhao, D.; He, C.; Shi, C.; Liu, E.; Zhao, N. Revealing the strengthening and toughening mechanisms of Al-CuO composite fabricated via in-situ solid-state reaction. Acta Mater. 2021, 204, 116524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembach, B.; Silchenko, Y.; Balenko, O.; Hlachev, D.; Kulahin, K.; Heiko, H.; Bellorin-Herrera, O.; Khabosha, S.; Zakovorotnyi, O.; Trembach, I. Study of the hardfacing process using self-shielding flux-cored wire with an exothermic addition with a combined oxidizer of the Al-(CuO/Fe2O3) system. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembach, B.; Trembach, I.; Maliuha, V.; Knyazev, S.; Krbata, M.; Kabatskyi, O.; Balenko, O.; Zarichniak, Y.; Brechka, M.; Mykhailo, B.; et al. Study of self-shielded flux-cored wire with exothermic additions CuO-Al on weld bead morphology, microstructure, and mechanical properties. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 4685–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozynskyi, V.; Trembach, B.; Katinas, E.; Sadovyi, K.; Krbata, M.; Balenko, O.; Krasnoshapka, I.; Rebrova, O.; Knyazev, S.; Kabatskyi, O.; et al. Effect of Exothermic Additions in Core Filler on Arc Stability and Microstructure during Self-Shielded, Flux-Cored Arc Welding. Crystals 2024, 14, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.; Zhang, M.; Ma, Q.; Fang, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, H. Research on the Welding Process and Weld Formation in Multiple Solid-Flux Cored Wires Arc Hybrid Welding Process for Q960E Ultrahigh-Strength Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.J.; Seo, B.W.; Son, H.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Cho, Y.T. Slag inclusion-free flux cored wire arc directed energy deposition process. Mater. Des. 2024, 238, 112669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassov, V.; Berezshna, O.; Yermakova, S.; Turchanin, D.; Malyhina, S. Features of heating and melting of powder tape for surfacing of composite and complex-alloyed alloys. East. Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2025, 2, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Xing, C.; Zhao, B.; Wu, C. Comprehensive analysis of spatter loss in wet FCAW considering interactions of bubbles, droplets and arc—Part 1: Measurement and improvement. J. Manuf. Process. 2019, 40, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.Z.I.; Turin, T.C. Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Fam. Med. Community Health 2020, 8, e000262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, E.; Yamazaki, K.; Suzuki, K.; Koshiishi, F. Effect of flux ratio in flux-cored wire on wire melting behaviour and fume emission rate. Weld. World 2010, 54, R154–R159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembach, B.O.; Hlushkova, D.V.; Hvozdetskyi, V.M.; Vynar, V.A.; Zakiev, V.I.; Kabatskyi, O.V.; Savenok, D.V.; Zakavorotnyi, O.Y. Prediction of Fill Factor and Charge Density of Self-Shielding Flux-Cored Wire with Variable Composition. Mater. Sci. 2023, 59, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, N.Q.; Tashiro, S.; Suga, T.; Kakizaki, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Morimoto, T.; Shimizu, H.; Lersvanichkool, A.; Bui, H.V.; Tanaka, M. Effect of Flux Ratio on Droplet Transfer Behavior in Metal-Cored Arc Welding. Metals 2022, 12, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Ma, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shan, C.; Liu, H.; Qi, Y.; Xie, Y.; Meng, X.; et al. High-efficient hybrid arc and friction stir additive manufacturing of high-performance Al-Cu-Mg-Ag-Zr alloy: Microstructural evolution and precipitation behaviors with Ω/L12 co-precipitates. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 124, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.H.F.; Paiva, A.P.; Costa, S.C.; Balestrassi, P.P.; Paiva, E.J. Weighted multivariate mean square error for processes optimization: A case study on flux-cored arc welding for stainless steel claddings. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 226, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.; Chang, J.; Houng, J.; Tsai, C.; Lin, C.; Tsen, H. Optimization of medium composition for improving biomass production of Lactobacillus plantarum Pi06 using the Taguchi array design and the Box-Behnken method. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2012, 17, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.M.; Bliemer, M.C. Constructing efficient stated choice experimental designs. Transp. Rev. 2009, 29, 587–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliemer, M.C.J.; Rose, J.M.; Hensher, D.A. Constructing efficient stated choice experiments allowing for differences in error variances across subsets of alternatives. Transp. Res. Part B 2009, 43, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, U.; Mokhtar, W. Quality Improvement of Polycarbonate Medical Device by Moldex3D and Taguchi DOE. J. Manuf. Mater. Process 2025, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniyan, I.A.; Tlhabadira, I.; Mpofu, K.; Adeodu, A.O. Process design and optimization for the milling operation of aluminum alloy (AA6063 T6). Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 32, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funai, V.I.; Melo, D.N.; Lima, N.M.; Pattaro, A.F.; Liñan, L.Z.; Bonon, A.J.; Maciel Filho, R. Attainment of kinetic parameters and model validation for nylon-6 process. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 2014, 33, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahali, M.A. Multi-objective optimization of FCA welding process: Trade-off between welding cost and penetration under hardness limitation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 110, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembach, I.O.; Trembach, B.O.; Grin, A.G.; Luzhetskyy, R.Y.; Brechko, V.O.; Zakovorotniy, O.Y.; Balenko, O.I.; Molchanov, H.I.; Rebrova, O.M.; Kabatskyi, O.V. Application of a complete factorial experiment for optimization of the filling factor and charge density of self-shielding flux-cored powder wire. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Y.; Shah, A.; Chaudhari, R.; Vaghasia, V.; Patel, V.; Vora, J. Experimental Investigations on Wire-Arc Additive Manufacturing of Metal-Cored Wires. Eng. Proc. 2025, 114, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembach, B.; Trembach, I.; Grin, A.; Makarenko, N.; Rebrov, O.; Musairova, Y.; Kuravska, N.; Knyazev, S.; Krasnoshapka, I.; Kuravskyi, M.; et al. Optimisation of hardfacing conditions carried out by self-shielded flux-cored wire using combined Taguchi method and factorial design. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 140, 1367–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, H.; Mozafari, V.; Roosta, H.R.; Farhangi, M. Optimizing growth conditions in vertical farming: Enhancing lettuce and basil cultivation through the application of the Taguchi method. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.T.; Ye, J.W. Optical design of contact lenses using principal component analysis method with Taguchi method. Appl. Math. Model. 2015, 39, 5778–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinothkumar, K.; Mathivanan, A. Optimization of CMT Welding for 18/8 Stainless Steel: A Teaching Learning Based Algorithm-Driven Approach. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, R.K.; Park, S.W. Analysis of activated sludge process using multivariate statistical tools—A PCA approach. Chem. Eng. J. 2002, 90, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Nandi, G.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Pal, P.D. Application of PCA-based hybrid Taguchi method for correlated multicriteria optimization of submerged arc weld: A case study. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2009, 45, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, A.R. Simultaneous optimization of multivariate surface roughness parameters in precision grinding of silicon by unsupervised machine learning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 139, 3543–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.; Pal, S.K. Tribological performance optimization of electroless Ni–P coatingsusing the Taguchi method and grey relational analysis. Tribol. Lett. 2007, 28, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahboun, S.; Maaroufi, M. Principal Component Analysis and Machine Learning Approaches for Photovoltaic Power Prediction: A Comparative Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisam, M.W.; Dar, A.A.; Elrasheed, M.O.; Khan, S.; Gera, R.; Azad, I. The Versatility of the Taguchi Method: Optimizing Experiments Across Diverse Disciplines. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 2024, 23, 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malene, S.H.; Park, Y.D.; Olson, D.L. Response of exothermic additions to the flux cored arc welding electrode-Part 1 Effectiveness of exothermically reacting magnesium-type flux additions was investigated with the flux-cored arc welding process. Weld. J. 2007, 86, 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Vaghasia, V.; Chaudhari, R.; Patel, V.K.; Vora, J. Parametric Study on Investigations of GMAW-Based WAAM Process Parameters and Effect on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of NiTi SMA. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembach, B.; Balenko, O.; Davydov, V.; Brechko, V.; Trembach, I.; Kabatskyi, O. Prediction the Melting Characteristics of Self-Shielded Flux Cored arc Welding (FCAW-S) with Exothermic Addition (CuO-Al). In Proceedings of the IEEE 4th International Conference on Modern Electrical and Energy System (MEES), Kremenchuk, Ukraine, 20–23 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarng, Y.S.; Yang, W.H.; Juang, S.C. Use of fuzzy logic in the Taguchi method for the optimization of the submerged arc welding process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2000, 16, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, N.; Singhal, S. Hybrid combination of Taguchi-GRA-PCA for optimization of wear behavior in AA6063/SiCp matrix composite. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2018, 6, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahapurkar, K.; Chenrayan, V.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Badruddin, I.A.; Shahapurkar, P.; Elfasakhany, A.; Mujtaba, M.; Siddiqui, M.I.H.; Ali, M.A.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Leverage of Environmental Pollutant Crump Rubber on the Dry Sliding Wear Response of Epoxy Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotelling, H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933, 24, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenrayan, V.; Gelaw, M.; Manivannan, C.; Rajamanickam, V.; Venugopal, E. An extensive data set related to micro-drilling of Al-SiC-B4C hybrid composite through µECM using GRA coupled PCA. Data Brief 2020, 33, 106491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanchuk, V.; Kruhlov, I.; Zakiev, V.; Lozova, A.; Trembach, B.; Orlov, A.; Voloshko, S. Thermal and Ion Treatment Effect on Nanoscale Thin Films Scratch Resistance. Met. Adv. Technol. 2022, 44, 1275–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymura, M.; Czupryński, A.; Ochodek, V. Development of a Mathematical Model of the Self-Shielded Flux-Cored Arc Surfacing Process for the Determination of Deposition Rate. Materials 2024, 17, 5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starling, C.M.D.; Modenesi, P.J. Metal Transfer Evaluation of Tubular Wires. Weld. Int. 2007, 21, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.K.; Tashiro, S.; Trinh, N.Q.; Tanaka, T.; Bui, H.V. Elucidation of alkali element’s role in optimizing metal transfer behavior in rutile-type flux-cored arc welding. J. Manuf. Process 2025, 139, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Fan, K.; Liu, H.; Ma, G. Characteristics of short-circuit behaviour and its influencing factors in self-shielded flux-cored arc welding. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2016, 21, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, M.T.; Bracarense, A.Q. A novel strategy to improve melting efficiency and arc stability in underwater FCAW via contact tip air chamber. J. Manuf. Process 2023, 104, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauné, E.; Bonnet, C.; Liu, S. Assessing Metal Transfer Stability and Spatter Severity in Flux Cored Arc Welding. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2001, 6, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Chadha, U.; Chadha, A.; Mahadevan, R.R.; Sai, B.R.; Chaudhary, D.; Selvaraj, S.K.; Lokeshkumar, R.; Das, S.; Karthikeyan, B.; et al. Weld Quality Monitoring via Machine Learning-Enabled Approaches. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2023, 3, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aita, C.A.G.; Goss, I.C.; Rosendo, T.S.; Tier, M.D.; Wiedenhoft, A.; Reguly, A. Shear strength optimization for FSSW AA6060-T5 joints by Taguchi and full factorial design. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 16072–16079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.C.; Chiang, S. Mathematical Modeling and Structural Equation Analysis of Acceptance Behavior Intention to AI Medical Diagnosis Systems. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, C.; Yi, J.; Li, X.; Yin, J. Analysis of Strength Effects on the Dynamic Response of a Shaped-Charge Under Lateral Disturbances. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veza, I.; Spraggon, M.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Idris, M. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) for Optimizing Engine Performance and Emissions Fueled with Biofuel: Review of RSM for Sustainability Energy Transition. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finšgar, M.; Jezernik, K. The Use of Factorial Design and Simplex Optimization to Improve Analytical Performance of In Situ Film Electrodes. Sensors 2020, 20, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavčnik, L.; Bohanec, S.; Trdan Lušin, T.; Roškar, R. Use of Factorial Designs to Reduce Stability Studies for Parenteral Drug Products: Determination of Factor Effects via Accelerated Stability Data Analysis. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, M.A. Minimizing Vibrations and Power Consumption in Milling of AZ31 Alloy Through Parameter Optimization. Results Eng. 2025, 107186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Klimpel, A. Industrial surfacing and hardfacing technology, fundamentals and applications. Weld. Technol. Rev. 2019, 91, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-K.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Liao, T.-W.; Kuo, C.-F.J. The Use of the Taguchi Method with Grey Relational Analysis for Nanofluid-Phase Change-Optimized Parameter Design at a Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Thermal Composite Module for Small Households. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thekkuden, D.T.; Sherif, M.M.; Alkhedher, M.; Iftikhar, S.H.; Mourad, A.H.I. Integrated Taguchi-PCA-GRA based multi objective optimization of tube projection and radial clearance for friction stir welded heat exchanger tube-to-tube sheet joints. Manufacture 2024, 7, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavimani, V.; Prakash, K.S.; Thankachan, T.; Nagaraja, S.; Jeevanantham, A.K.; Jhon, J.P. WEDM Parameter Optimization for Silicon@r-GO/Magneisum Composite Using Taguchi Based GRA Coupled PCA. Silicon 2020, 12, 1161–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, H.; Vargas, Z.; Valdez, S.; Serrano, M.; del Pozo, A.; Alcántara, M. Taguchi, Grey Relational Analysis, and ANOVA Optimization of TIG Welding Parameters to Maximize Mechanical Performance of Al-6061 T6 Alloy. J. Manuf. Mater. Process 2024, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, M.I.; Akhtar, R.; Abas, M.; Khalid, Q.S.; Babar, A.R.; Pruncu, C.I. An Integrated Approach of GRA Coupled with Principal Component Analysis for Multi-Optimization of Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW) Process. Materials 2020, 13, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, H.N.; Nishi, T.; Ohta, H. Measurement of Exothermic Values of Casting-sleeve Materials Using an Ice Calorimeter. ISIJ Int. 2023, 63, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, N.Q.; Tashiro, S.; Tanaka, K.; Suga, T.; Kakizaki, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Morimoto, T.; Shimizu, H.; Lersvanichkool, A. Effects of Alkaline Elements on the Metal Transfer Behavior in Metal Cored Arc Welding. J. Manuf. Process 2021, 68, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Xinglong, Y.; Yingjie, H.; Jiankang, H.; Dequan, L. The study of arc behavior with different content of copper vapor in GTAW. China Weld. 2022, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaghimi-Tehrani, J.; Pfender, E. Effects of metallic vapor on the properties of an argon arc plasma. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process 1984, 4, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myamlin, S.; Dailidka, S.; Neduzha, L. Mathematical modeling of a cargo locomotive. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Transport Means, Kaunas, Lithuania, 25–26 October 2012; pp. 310–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lunys, O.; Neduzha, L.; Tatarinova, V. Stability research of the main-line locomotive movement. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference Transport Means, Palanga, Lithuania, 2–4 October 2019; pp. 1341–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko, I.; Severino, A.; Olayode, I.O.; Campisi, T.; Neduzha, L. Dynamic Sustainable Processes Simulation to Study Transport Object Efficiency. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goolak, S.; Riabov, I.; Petrychenko, O.; Kyrychenko, M.; Pohosov, O. The simulation model of an induction motor with consideration of instantaneous magnetic losses in steel. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2025, 17, 16878132251320236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goolak, S.; Riabov, I.; Tkachenko, V.; Sapronova, S.; Rubanik, I. Model of pulsating current traction motor taking into consideration magnetic losses in steel. Electr. Eng. Electromechanics 2021, 6, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimenko, I.; Kalivoda, J.; Neduzha, L. Influence of Parameters of Electric Locomotive on its Critical Speed. In Lecture Notes in Intelligent Transportation and Infrastructure, Proceedings of the TRANSBALTICA XI: Transportation Science and Technology, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2–3 May 2019; Gopalakrishnan, K., Prentkovskis, O., Jackiva, I., Junevičius, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riabov, I.; Goolak, S.; Neduzha, L. An Estimation of the Energy Savings of a Mainline Diesel Locomotive Equipped with an Energy Storage Device. Vehicles 2024, 6, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, D.; Kowalczyk, J.; Josko, M.; Sawczuk, W.; Chudyk, P. Assessment of selected properties of varnish coating of motor vehicles. Coatings 2021, 11, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatskyi, I.; Makoviichuk, M.; Ropyak, L. Planede formation of contrast layered coating under local load. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 59, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalyak, T.M.; Shatsky, I.P. On brittle fracture of a body with partial healed star-shaped crack. Bull. Taras Shevchenko Natl. Univ. Kyiv Phys. Math. Sci. 2023, 2, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutkiewicz, M.; Dalyak, T.; Shatskyi, I.; Venhrynyuk, T.; Velychkovych, A. Stress analysis in damaged pipe line with composite coating. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzan, S.A.; Sidashenko, A.I.; Luzan, A.S. Composite material for hardening of tillage machines working bodies containing titanium and chromium borides synthesized using shs-process. Metallofiz. Noveishie Tekhnologii 2020, 42, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzan, S.A.; Bantkovskiy, V.A. Structure and Tribotechnical Properties of Deposited Composite Layers Based on PG 10N-01 Alloy Containing AL2O3. Mater. Sci. 2023, 59, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezher, M.T.; Pereira, A.; Trzepieciński, T. Study on Fatigue Life and Fracture Behaviour of Similar and Dissimilar Resistance Spot-Welded Joints of Titanium Grade 2 Alloy and Austenitic Stainless Steel 304. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.L.; Qin, Z.W.; Jiang, X.; Wang, J.L.; Li, J.C.; Ding, Z.J.; Wang, J.K.; Shi, S.Y.; Li, P.; Dong, H.G. Compositional and structural control toward boosting inner-grain prestress and releasing inter-lattice strain of FGH99 diffusion bonded superalloy. Mater. Horiz. 2026. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Input Variable (Factor) | Unit | Notation | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (1) | Average (2) | High (3) | ||||

| A | Percentage of exothermic mixture in the core filler | [m·min−1] | EA | 1.63 | 1.85 | 2.07 |

| B | Contact tip-to-work distance | [mm] | CTWD | 35 | 40 | 45 |

| C | Wire feed speed | [m·min−1] | WFS | 1.50 | 2.07 | 2.73 |

| D | Set voltage on the power source | [V] | Uset | 26.0 | 31 | 34 |

| No. Exp. | Fact Mean | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM, [wt.%] | CTWD, [mm] | WFS, [m·min−1] | Uset, [V] | |

| 1 | 18 | 35 | 1.63 | 28 |

| 2 | 18 | 40 | 1.85 | 31 |

| 3 | 18 | 45 | 2.07 | 34 |

| 4 | 28 | 35 | 1.85 | 34 |

| 5 | 28 | 40 | 2.07 | 28 |

| 6 | 28 | 45 | 1.63 | 31 |

| 7 | 38 | 35 | 2.07 | 31 |

| 8 | 38 | 40 | 1.63 | 34 |

| 9 | 38 | 45 | 1.85 | 28 |

| Parameters | Melt-Off Rate (MOR) | Deposition Rate (DR) | Spattering Factor (SF) |

| Selected category | Larger the better | Larger the better | Smaller the better |

| Parameters | Width of bead (WB) | Top height of reinforcement (THR) | Bottom Depth of Penetration (DP) |

| Selected category | Smaller the better | Large the better | Smaller the better |

| Parameters | Cross-Sectional Area of Reinforcement (Ar) | Cross-Sectional Area of Penetration (Ap) | Dilution Variation (Dv) |

| Selected category | Large the better | Smaller the better | Smaller the better |

| The Name of the Component | Content of the Components in Core Filler of FCAW-S, [wt.%] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | E2 | E3 | |

| Gas-slag-forming components | |||

| Fluorite concentrate GOST 4421-73 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Rutile concentrate GOST 22938-78 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Calcium carbonate GOST 8252-79 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Zirconium dioxide GOST 21907-76 | 15 | 5 | 0 |

| Components of exothermic additive | |||

| Oxide of copper powder GOST 16539-79 | 15 | 23.3 | 32.5 |

| Aluminum powder PA1 GOST 6058-73 | 3 | 4.7 | 6.5 |

| Alloying and deoxidizers | |||

| Ferromanganese FMN-88A GOST 4755-91 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Ferrosilicon FS-92 GOST 1415-78 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Ferrovanadium FVd-40 GOST 27130-94 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Titanium powder PTM-3 TU 14-22-57-92 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Metal Chrome X99 GOST 5905-79 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 6.5 |

| Graphite | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Iron powder PZhR-1 GOST 9849-86 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| No. Exp. | Melt-Off Rate MOR, [kg·hr−1] | Deposition Rate DR, [kg·hr−1] | ||||||

| MOR (e) | MOR (c) | Difference | Deviation | DR (e) | DR (c) | Difference | Deviation | |

| 1 | 4.43 | 4.43 | 0.001 | 0.01% | 3.88 | 3.88 | 0.0043 | 0.11% |

| 2 | 4.83 | 4.83 | 0.000 | 0.00% | 4.28 | 4.28 | 0.0000 | 0.00% |

| 3 | 5.04 | 5.04 | 0.000 | 0.01% | 4.52 | 4.52 | 0.0043 | 0.09% |

| 4 | 5.38 | 5.38 | 0.003 | 0.06% | 4.79 | 4.81 | 0.0171 | 0.36% |

| 5 | 5.73 | 5.72 | 0.003 | 0.04% | 5.07 | 5.07 | 0.0000 | 0.00% |

| 6 | 4.85 | 4.85 | 0.001 | 0.01% | 4.51 | 4.49 | 0.0171 | 0.38% |

| 7 | 5.52 | 5.52 | 0.002 | 0.04% | 5.16 | 5.15 | 0.0086 | 0.17% |

| 8 | 4.37 | 4.37 | 0.001 | 0.03% | 3.98 | 3.98 | 0.0000 | 0.00% |

| 9 | 5.04 | 5.04 | 0.003 | 0.07% | 4.83 | 4.84 | 0.0086 | 0.18% |

| No. Exp. | Spattering Factor SF [%] | Deposition Efficiency De [%] | ||||||

| SF (e) | SF (c) | Difference | Deviation | De (e) | De (c) | Difference | Deviation | |

| 1 | 9.68 | 9.73 | 0.050 | 0.52% | 87.55% | 87.79% | 0.24% | 0.27% |

| 2 | 8.45 | 9.16 | 0.707 | 8.51% | 88.70% | 88.28% | 0.42% | 0.47% |

| 3 | 10.12 | 9.36 | 0.757 | 7.71% | 89.68% | 89.86% | 0.18% | 0.20% |

| 4 | 10.15 | 10.86 | 0.707 | 6.89% | 89.09% | 88.67% | 0.42% | 0.47% |

| 5 | 11.12 | 10.36 | 0.757 | 6.80% | 88.53% | 88.71% | 0.18% | 0.20% |

| 6 | 6.02 | 6.07 | 0.050 | 0.83% | 93.02% | 93.26% | 0.24% | 0.25% |

| 7 | 5.35 | 4.44 | 0.757 | 14.55% | 93.54% | 93.72% | 0.18% | 0.19% |

| 8 | 7.9 | 8.05 | 0.050 | 0.62% | 91.00% | 91.24% | 0.24% | 0.26% |

| 9 | 3.52 | 3.91 | 0.707 | 22.08% | 95.76% | 95.34% | 0.42% | 0.44% |

| Criteria | Mathematical Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y(MOR) | Y(DR) | Y(SF) | Y(De) | |

| Coefficient of Determination (R sqr) | 0.9998 | 0.9855 | 0.9999 | 0.9738 |

| Adjusted Sum of Squares (R Adj) | 0.9994 | 0.9422 | 0.9989 | 0.9301 |

| Model quality | Very good | Very good | Very good | Very good |

| No. Exp. | Width of Bead | Top Height of Reinforcement | ||||||||||

| Experimental | WB (c) [mm] | Diff. [mm] | Dev. [%] | Experimental | THR (c) [mm] | Diff. [mm] | Dev. [%] | |||||

| 1 | 2 | WB (e) [mm] | 1 | 2 | THR (e) [mm] | |||||||

| 1 | 13.85 | 13.25 | 13.55 | 13.812 | −0.262 | 1.93 | 3.08 | 3.08 | 3.08 | 3.301 | −0.221 | 7.18 |

| 2 | 20.343 | 19.89 | 20.12 | 19.046 | 1.070 | 5.32 | 2.72 | 1.69 | 2.20 | 2.101 | 0.099 | 4.50 |

| 3 | 18.77 | 17.29 | 18.03 | 17.820 | 0.210 | 1.16 | 3.20 | 3.15 | 3.17 | 3.079 | 0.094 | 2.95 |

| 4 | 16.315 | 18.154 | 17.23 | 18.069 | −0.834 | 4.84 | 3.26 | 3.04 | 3.15 | 3.663 | −0.513 | 16.28 |

| 5 | 16.63 | 16.06 | 16.35 | 15.847 | 0.498 | 3.05 | 5.32 | 5.00 | 5.16 | 5.156 | 0.001 | 0.02 |

| 6 | 17.54 | 15.26 | 16.40 | 16.763 | −0.363 | 2.21 | 5.11 | 4.60 | 4.86 | 4.296 | 0.561 | 11.54 |

| 7 | 19.18 | 17 | 18.09 | 18.798 | −0.708 | 3.91 | 3.46 | 5.03 | 4.24 | 4.339 | −0.095 | 2.23 |

| 8 | 16.32 | 16.5 | 16.41 | 15.785 | 0.625 | 3.81 | 2.32 | 2.49 | 2.41 | 2.746 | −0.340 | 14.11 |

| 9 | 16.43 | 15.29 | 15.86 | 16.096 | −0.236 | 1.49 | 3.11 | 2.74 | 2.93 | 2.515 | 0.414 | 14.13 |

| No. Exp. | Bottom Depth of Penetration | Cross-Sectional Area of Reinforcement | ||||||||||

| Experimental | DP (c) [mm] | Diff. [mm] | Dev. [%] | Experimental | Ar (c) [mm2] | Diff. [mm2] | Dev. [%] | |||||

| 1 | 2 | DP (e) [mm] | 1 | 2 | Ar (e) [mm2] | |||||||

| 1 | 1.242 | 1.149 | 1.20 | 1.03 | 0.17 | 13.83 | 33.14 | 32.446 | 32.79 | 34.39 | −1.60 | 4.83 |

| 2 | 2.6 | 2.543 | 2.57 | 2.28 | 0.30 | 11.49 | 44.75 | 32.97 | 38.86 | 39.64 | −0.78 | 1.74 |

| 3 | 2 | 1.486 | 1.74 | 1.75 | −0.01 | 0.45 | 47.78 | 41.455 | 44.62 | 42.24 | 2.38 | 4.98 |

| 4 | 1.6 | 1.458 | 1.53 | 1.74 | −0.21 | 13.88 | 39.483 | 37.44 | 38.46 | 40.06 | −1.60 | 4.05 |

| 5 | 1.829 | 2.2 | 2.01 | 2.15 | −0.14 | 6.91 | 69.36 | 60.74 | 65.05 | 65.83 | −0.78 | 1.12 |

| 6 | 0.858 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.94 | −0.01 | 0.95 | 70.29 | 50.7 | 60.50 | 58.12 | 2.38 | 3.38 |

| 7 | 1.916 | 2.286 | 2.10 | 1.95 | 0.15 | 7.00 | 51.254 | 61.382 | 56.32 | 57.92 | −1.60 | 3.12 |

| 8 | 1.315 | 1.72 | 1.52 | 1.67 | −0.16 | 10.31 | 24.453 | 27.816 | 26.13 | 26.91 | −0.78 | 3.18 |

| 9 | 1.77 | 1.657 | 1.71 | 1.70 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 34.853 | 33.94 | 34.40 | 32.02 | 2.38 | 6.82 |

| No. Exp. | Cross-Sectional Area of Penetration | Dilution Variation | ||||||||||

| Experimental | Ap (c) [mm2] | Diff. [mm2] | Dev. [%] | Experimental | Dv (c) | Diff. | Dev. [%] | |||||

| 1 | 2 | Ap (e) | 1 | 2 | Dv (e) | |||||||

| 1 | 12 | 10.78 | 11.39 | 13.28 | −1.89 | 15.72 | 26.58 | 24.94 | 25.76 | 27.19 | −1.43 | 5.54 |

| 2 | 35.917 | 31.878 | 33.90 | 33.07 | 0.83 | 2.30 | 44.53 | 49.16 | 46.84 | 42.74 | 4.10 | 8.75 |

| 3 | 27.385 | 19.128 | 23.26 | 25.03 | −1.78 | 6.48 | 36.43 | 31.57 | 34.00 | 37.15 | −3.14 | 9.25 |

| 4 | 17.423 | 23.87 | 20.65 | 21.71 | −1.07 | 6.12 | 30.62 | 38.93 | 34.78 | 32.64 | 2.13 | 6.13 |

| 5 | 20.776 | 23.17 | 21.97 | 20.33 | 1.65 | 7.92 | 23.05 | 27.61 | 25.33 | 23.67 | 1.66 | 6.57 |

| 6 | 14.1 | 12.24 | 13.17 | 14.13 | −0.96 | 6.78 | 16.71 | 19.45 | 18.08 | 21.07 | −2.99 | 16.56 |

| 7 | 25.82 | 23.26 | 24.54 | 24.41 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 33.50 | 27.48 | 30.49 | 29.01 | 1.48 | 4.85 |

| 8 | 17.37 | 14.89 | 16.13 | 13.29 | 2.84 | 16.36 | 41.53 | 34.87 | 38.20 | 33.78 | 4.42 | 11.57 |

| 9 | 20.66 | 16.76 | 18.71 | 18.47 | 0.24 | 1.17 | 37.22 | 33.06 | 35.14 | 41.37 | −6.23 | 17.73 |

| Criteria | Mathematical Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y(WB) | Y(THR) | Y(DP) | Y(Ar) | Y(Ap) | Y(Dv) | |

| Coefficient of Determination (R sqr) | 0.87505 | 0.94837 | 0.97622 | 0.98189 | 0.99316 | 0.95465 |

| Adjusted Sum of Squares (R Adj) | 0.75009 | 0.86231 | 0.90489 | 0.92756 | 0.97263 | 0.87907 |

| Model quality | Good | Good | Good | Very good | Very good | Good |

| No. Exp. | DRn | SFn | Arn | Dvn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.000000 | 0.179293 | 0.171120 | 0.717582 |

| 2 | 0.312500 | 0.356061 | 0.327081 | 0.000000 |

| 3 | 0.500000 | 0.164141 | 0.475077 | 0.257960 |

| 4 | 0.710938 | 0.109848 | 0.316804 | 0.466082 |

| 5 | 0.929688 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.880018 |

| 6 | 0.492187 | 0.643939 | 0.883094 | 1.000000 |

| 7 | 1.000000 | 0.747475 | 0.775694 | 0.633595 |

| 8 | 0.078125 | 0.393939 | 0.000000 | 0.413475 |

| 9 | 0.742188 | 1.000000 | 0.212487 | 0.292570 |

| Principal Component | MOR | DR | SF | De |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 0.591220 | 0.063572 | 0.672680 | 0.440362 |

| PC2 | 0.354118 | 0.845546 | −0.148242 | −0.371048 |

| PC3 | −0.521316 | 0.511276 | −0.036763 | 0.682257 |

| PC4 | −0.503278 | 0.140025 | 0.723999 | −0.450478 |

| No. Exp. | GRA | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.433296 | 7 |

| 2 | 0.402523 | 8 |

| 3 | 0.445944 | 6 |

| 4 | 0.487322 | 5 |

| 5 | 0.778055 | 1 |

| 6 | 0.722851 | 3 |

| 7 | 0.745481 | 2 |

| 8 | 0.396078 | 9 |

| 9 | 0.598183 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Trembach, B.; Dmitriiev, O.; Kulahin, K.; Balenko, O.; Maliuha, V.; Neduzha, L. Hybrid Optimization of Hardfacing Conditions and the Content of Exothermic Additions in the Core Filler During the Flux-Cored Arc Welding Process. Eng 2026, 7, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010023

Trembach B, Dmitriiev O, Kulahin K, Balenko O, Maliuha V, Neduzha L. Hybrid Optimization of Hardfacing Conditions and the Content of Exothermic Additions in the Core Filler During the Flux-Cored Arc Welding Process. Eng. 2026; 7(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrembach, Bohdan, Oleh Dmitriiev, Kostiantyn Kulahin, Oleksii Balenko, Volodymyr Maliuha, and Larysa Neduzha. 2026. "Hybrid Optimization of Hardfacing Conditions and the Content of Exothermic Additions in the Core Filler During the Flux-Cored Arc Welding Process" Eng 7, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010023

APA StyleTrembach, B., Dmitriiev, O., Kulahin, K., Balenko, O., Maliuha, V., & Neduzha, L. (2026). Hybrid Optimization of Hardfacing Conditions and the Content of Exothermic Additions in the Core Filler During the Flux-Cored Arc Welding Process. Eng, 7(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010023