Abstract

The structural performance of automotive doors is highly dependent on their metallic support; however, conventional development processes often involve multiple CAD-CAE iterations, which increase lead time and engineering effort. This study presents a methodology for optimizing metallic support geometry by integrating Computer-Aided Design (CAD), Computer-Aided Engineering (CAE), and the Taguchi Design of Experiments (DOE). A Taguchi L16 orthogonal array was used to evaluate eight key geometric factors, including material thickness, fixation point configuration, and geometric reinforcements. Finite element simulations with a meshless solver significantly reduced pre-processing time without compromising accuracy. By analyzing the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio, the optimal factor combination was identified, which maximized stiffness while minimizing displacement and ensuring robustness against material variability. The optimal design achieved a stiffness of 248 N/mm, a substantial increase over the baseline’s 39 N/mm. This design demonstrates the potential of this methodology to dramatically improve structural performance from the early stages of development and accelerate product development by reducing design iterations.

1. Introduction

Driven by a global demand for safer, more reliable, and more sustainable vehicles, the automotive industry is undergoing continuous evolution. A pivotal strategy for achieving these objectives is vehicle lightweighting, which entails reducing a vehicle’s overall mass without compromising performance, structural integrity, or safety standards [1,2]. In practical terms, many OEMs now target a 5% to 10% reduction in curb weight, aiming to improve fuel efficiency by 6% to 8% for every 10% of mass saved [3]. Other studies indicate that a 10% weight reduction can reduce fuel consumption by up to 7% and, correspondingly, CO2 emissions [4]. Moreover, projections suggest that the market for lightweight automotive materials will grow from USD 73.9 billion in 2022 to USD 101.5 billion by 2027, reflecting the strategic importance of weight reduction in future vehicle design. The vehicle door, as a critical component that fulfills multiple functions—from structural support and security to aesthetics and passenger access—constitutes a primary area for implementing innovative lightweighting and optimization strategies [5,6,7,8]. The design of a modern automotive door presents a complex, multi-faceted engineering challenge, necessitating a careful balance among competing objectives such as weight, rigidity, noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH), as well as manufacturability and cost [9,10]. The importance of balancing these objectives is well-documented in the literature [5].

In this context of lightweighting, the use of advanced metals and alloys has emerged as a cornerstone of automotive strategies. These materials offer superior strength, durability, and a high strength-to-weight ratio, enabling mass reduction in various components [11,12]. The manufacturing process for these metallic components, such as stamping or forming, enables mass production of intricate and complex geometries [13,14,15]. However, this process is susceptible to defects that compromise a product’s quality and structural performance, such as residual stresses and warpage [16,17]. Consequently, optimizing manufacturing parameters is crucial for mitigating these issues [18]. The broader field of process parameter optimization is also subject to an extensive review [11,15].

To address the complexities of both structural design and manufacturing processes, the automotive industry has widely adopted Computer-Aided Engineering (CAE) as a powerful tool for virtual prototyping [1,19]. Methodologies such as Finite Element Analysis (FEA) enable engineers to simulate and predict a component’s behavior under various load conditions before fabricating a physical prototype [20,21]. This approach not only reduces the time and cost of traditional trial-and-error development [1,20] but also facilitates a more thorough exploration of the design space [22]. FEA has been successfully applied to evaluate a wide range of critical performance attributes, including crashworthiness, static stiffness, and dynamic responses [6,20,22]. Its integration with other computational methods further enhances the accuracy and efficiency of complex simulations [21,22,23].

While CAE provides the analytical capability to evaluate a design, it must be coupled with a robust optimization methodology to comprehensively identify the most favorable solution among a multitude of design variables. The Taguchi method, a form of design of experiments (DOE), has proven to be an effective approach for this purpose [24], with its application in the automotive field being well-documented [25]. This method is particularly well-suited for tackling multi-objective optimization problems [10,26]. Techniques such as Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can be integrated with the Taguchi method to convert multiple performance characteristics into a single objective function, thereby rendering the optimization process more manageable and effective [6]. However, despite these advances, most prior studies have focused on plastic components, crash simulations, or general structural panels. At the same time, the application of a CAD–CAE–Taguchi framework specifically for metallic door supports remains largely unexplored. Moreover, the use of meshless CAE tools such as Altair SimSolid, which significantly reduces the pre-processing effort compared to traditional FEA, has rarely been reported in conjunction with robust optimization strategies [27]. This gap underscores the novelty of the present work, which integrates Taguchi design with SimSolid-based simulations to optimize the stiffness of metallic door supports systematically.

The combination of CAD, CAE, and the Taguchi method constitutes a powerful and efficient integrated design framework [26]. This methodology enables rapid exploration of design variations in a virtual environment, enabling engineers to identify an optimal, robust solution. For automotive door components, this integrated approach can be employed to optimize complex geometries, such as the architecture of reinforcing ribs, to enhance vibrational response and structural integrity [28]. Alternatively, it can be used to determine the optimal thickness of key structural elements, thereby enhancing performance while reducing weight [2,5].

Building on these established principles, the present study proposes a methodology to optimize the geometry of a metallic support for an automotive door. This research leverages an integrated CAD-CAE–Taguchi approach to address a multi-objective optimization problem that considers several key geometric factors. Using a Taguchi L16 orthogonal array, the effects of these factors on the support’s structural rigidity were thoroughly investigated to identify the optimal design for achieving maximum performance. The findings of this research aim to provide a practical and efficient framework for automotive engineers, thereby minimizing engineering lead time while facilitating the development of high-performance, lightweight, and robust structural components.

2. Methodology

The methodological framework integrated CAD-based geometric benchmarking, robust design principles, and simulation-driven evaluation to determine the most effective configuration of metallic door supports for stiffness. A geometric comparison of production components established the control factors and feasible levels, which were then arranged in a Taguchi L16 orthogonal design with an outer array to account for material variability [2,25]. Structural performance was assessed through Altair SimSolid simulations under consistent boundary conditions, enabling the identification of robust designs [27,29,30].

2.1. Comparative Analysis of Geometric Factors

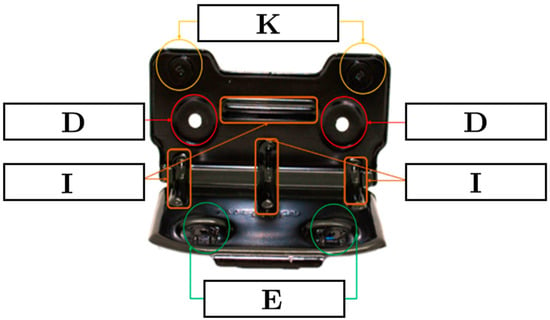

The study begins with a CAD-based geometric comparison of 25 metallic door supports from production vehicles (Figure 1). The metallic support is a critical internal bracket within the door assembly, providing the primary structural connection between the exterior door handle and the Body-in-White (BIW), thereby transmitting user-applied loads during handle operation. Each component was reviewed in a CAD environment to identify and catalog design factors relevant to stiffness: A. Vehicle, B. Thickness, C. Handle fixation points, D. Body fixation points, E. Distance between handle fixation points, F. Distance between body fixation points, G. Distance between handle-to-body fixation points, Z axis, H. Distance between handle-to-body fixation points, Y axis, I. Geometric reinforcements, J. Angle, K. Geometric locators, L. Central displacement in the Y axis at 50 N, M. Stiffness, N. Requirement compliance: 0–49 N/mm = Does not comply, 50–100 N/mm = Complies, >101 N/mm = Exceeds, O. Material (Type 1, Type 2).

Figure 1.

Representative metallic door support and its key design factors. This diagram illustrates the key geometric factors identified through the CAD-based comparative analysis, including handle fixation points (E), body fixation points (D), geometric reinforcements (I), and geometric locators (K). These factors were selected for their relevance to structural stiffness and manufacturability.

The objective of this comparison was to identify control factors, noise factors, and feasible levels (low and high) based on real-world designs and to constrain the experimental design to what is currently manufacturable.

2.2. Parameter Diagram (P-Diagram)

Based on the comparative analysis results, we developed the P-diagram (see Figure 2), a fundamental tool for structuring the overall design landscape. This diagram enabled the classification of control factors, noise factors, and responses of interest, a crucial step in properly delimiting the experimental space. This phase served as a methodological bridge between the initial characterization of the problem and the formal design of the experiment, providing a solid basis for our justified selection of factors and levels within the Taguchi method. It also helped us ensure that the Taguchi orthogonal array captured the true variability associated with material type, which we treated as a noise factor in our experiment.

Figure 2.

P-diagram for the metallic door support. This diagram was used to structure the experimental design by classifying inputs, outputs, and noise factors. The material type (Type 1 and Type 2) was treated as a noise factor and implemented via an outer array in the experimental design, resulting in 32 total simulations (16 geometric configurations × 2 materials).

2.3. Control Factors and Levels

Based on the P-diagram and the comparative analysis, the geometric factors with the greatest potential impact on the metallic support’s structural performance were identified. Subsequently, low and high levels were established for each factor to construct the experimental design.

These levels were selected through graphical and statistical analysis of the collected dataset, which revealed distributions, operating ranges, and outliers. This process ensured the experimental space was limited to realistic combinations with a high probability of generating technically feasible results. The distribution graphs and detailed analysis supporting the defined levels are presented in the Results section. Ultimately, eight control factors, each with two levels, were defined based on their potential influence on stiffness, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Geometric control factors and their defined levels for the Taguchi L16 orthogonal array.

Optimization Problem Formulation

The robust optimization problem in this study is formally defined as follows:

- Design Variables: The eight geometric control factors (F1–F8) detailed in Table 1 constitute the design variables for the optimization. Each variable was studied at two levels (low and high) based on the feasible ranges identified from the CAD benchmarking analysis.

- Objective Function: Maximize the structural rigidity of the metallic support. This was implemented by maximizing the “Larger-the-Better” Signal-to-Noise (S/N) ratio for stiffness K, based on simulation results. The S/N ratio serves as a robust performance metric that simultaneously maximizes the mean stiffness while minimizing performance variation (sensitivity) due to noise factors (material variability) [24].

- Constraint Function: No explicit constraint functions were applied in this initial screening study. The design space was inherently constrained by defining the low and high levels for each geometric factor (Table 1) within manufacturable and physically feasible ranges, as determined by the prior analysis of production vehicle components. This approach aligns with methodologies used in similar component-level optimization studies [2,5,31].

2.4. Taguchi L16 Orthogonal Array Design

A Taguchi L16 orthogonal array was employed to study the eight control factors. This methodological approach is a key strength of the study, as it reduces the total experimental combinations from 256 (28 full factorial) to only 16 runs, representing a 93.75% reduction in the number of models and simulations required. The 16 CAD models were generated parametrically, greatly automating and accelerating the remodeling process. This efficient sampling strategy makes the optimization workflow feasible without excessive computational burden (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Taguchi L16 orthogonal array for the experimental design. Control factors F1–F8 correspond to the geometric parameters defined in Table 1.

An outer array was incorporated to account for noise factors. The material type (Type 1 and Type 2) was treated as a noise factor and implemented via this outer array in the experimental design. This approach increased the number of simulations to 32 runs (16 geometric configurations from the L16 orthogonal array × 2 material types) to evaluate the design’s robustness against material variability.

Based on the defined L16 orthogonal array, a parametric CAD environment generated models for each geometric configuration. The dimensions and features were parametrically controlled to match the DOE’s factor levels, ensuring the models accurately represented the intended variations and facilitating the subsequent comparative analysis of structural performance.

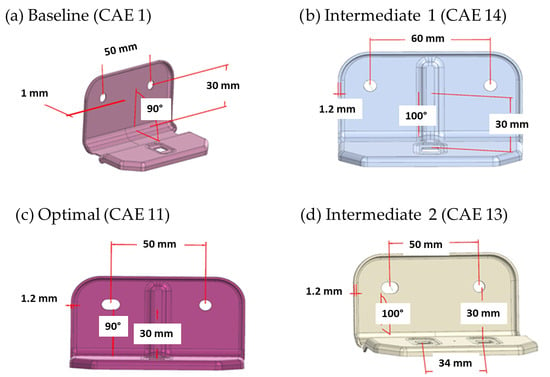

To document this stage, representative thumbnail images of the CAD models for each experimental combination are included in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Parametric CAD models for the 16 experimental combinations of the Taguchi design. These models were generated based on the eight control factors and their two levels, representing the intended geometric variations for accurate simulation. The diagrams show key dimensions corresponding to the design parameters.

2.5. CAE Simulation and Setup

Once the CAD models of the metallic support were completed for the 16 configurations defined in the experimental design, the computational simulation stage began using CAE tools. This phase aims to evaluate the structural performance of each design under a 50 N loading condition, which represents a typical door handle actuation force based on industry standards and ergonomic studies [32], ensuring the component can withstand real-world use. The analysis focuses on displacement and stiffness, critical variables for ensuring the component’s functionality and durability.

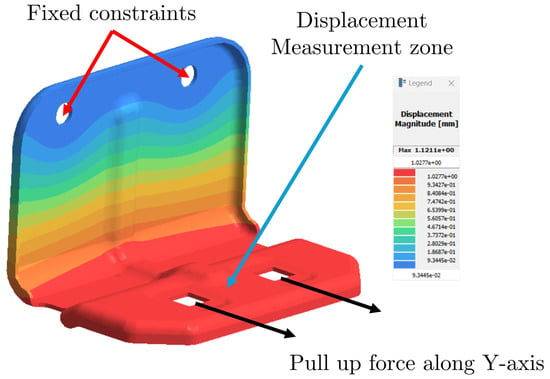

The procedure for performing the CAE simulations for each configuration is described below. This procedure included defining boundary conditions, applied loads, and materials. To replicate the component’s real-world function, the attachment points to the body (BIW) were considered fully restrained, simulating a rigid connection. Each model was subjected to a 50 N load on the Y-axis in the contact area between the metallic support and the door handle, while the attachment points to the body were considered fully restrained (see Figure 4). This idealization of fully fixed constraints at the Body-in-White (BIW) attachment points is a common, conservative practice in the early design stages of this type of component-level analysis [33]. It provides an estimate of the support’s maximum intrinsic stiffness. While real-world door hinges introduce some compliance, which would affect absolute stiffness values, this simplified approach remains valid for the primary goal of this study: the relative comparison of stiffness between different geometric configurations under identical boundary conditions. The assigned mechanical properties correspond to the two materials selected during the experimental planning stage.

Figure 4.

Free-body diagram of the metallic support, showing boundary conditions. The model is shown with a 50 N load applied on the Y-axis at the contact area of the handle, and the attachment points to the body are fully restrained.

These materials, representative of common automotive steel grades (e.g., Advanced High-Strength Steel and Low-Carbon Steel), were treated as noise factors to assess design robustness. Their complete mechanical properties are detailed in Table 3. Although the outer array was implemented to account for material variability, the specific material batches chosen for this study had a very similar Young’s Modulus (differing by <2%). This resulted in nearly identical stiffness values (N1 and N2) for each geometric configuration in Figure 3. This demonstrates that, for the chosen materials, geometric factors dominate the structural response. However, the methodological framework is designed to capture larger material variabilities, typically in industrial supply chains.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of the materials used as a noise factor in the experimental design.

A linear static analysis method was employed for all simulations. This approach was deemed appropriate for three key reasons. First, the applied load of 50 N is low and well below the threshold for yielding in the metallic materials used, making material nonlinearity negligible. Second, the expected and calculated displacements were small (see Table 3), meaning geometric nonlinearity—where stiffness changes due to large displacements—is not significant. Finally, the primary goal of this study was to compare stiffness across geometric configurations under identical, standardized conditions, rather than to predict absolute failure. The linear method is therefore both efficient and sufficient for this screening and optimization purpose.

To perform the CAE simulations, a standardized procedure was followed to evaluate the structural performance of the metallic supports generated through the experimental design. As previously mentioned, this analysis considered 32 combinations, resulting from the 16 configurations defined in the orthogonal array and the two noise factor levels corresponding to the two types of materials.

The procedure began with the inclusion of an auxiliary feature in the CAD models, which featured two attachment points to the handle. A 0.5 mm diameter hole was located between these points and used as a reference for measuring the effective displacement. Each model was then exported from Siemens NX [34] and imported into the simulation environment.

Once the geometry was loaded, the corresponding material was assigned according to the experimental design. The analysis was configured as a linear structural analysis with fully constrained boundary conditions at the body attachment points. Additionally, a point load of 50 N was applied in the Y-direction to the handle’s attachment faces, and the bolt bearing faces were restrained to prevent unwanted lateral displacement.

With the model fully configured, the simulation was run. The results were accessed by selecting the “Displacement Magnitude” option to evaluate the generated deformation. The effective displacement was obtained by measuring the average displacement on the face of the previously defined auxiliary hole. For configurations with a single attachment point, the innermost face of the main hole was considered.

Finally, based on this average displacement, the structural stiffness of each configuration was calculated as the applied load (50 N) divided by the measured displacement. This value represents the response of interest defined in the parameter diagram, reflecting the metallic support’s ability to resist deformations under applied loads.

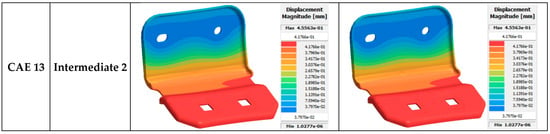

To complement the documentation of the CAE simulation stage, representative thumbnail images of the models generated for each of the 32 experimental combinations are included in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

CAE simulation results for the 32 experimental combinations. The images display the displacement analysis for each of the 16 geometric configurations across the two material types (noise factor). The color gradients indicate the magnitude of displacement, with red showing areas of maximum deformation.

2.6. Simulation Setup

Structural simulations were conducted using Altair SimSolid (version 2022.1) [29]. This meshless FEA software (Altair SimSolid 2022.1) eliminates the traditional and time-consuming meshing process, thereby drastically reducing pre-processing time and shortening the design cycle. This method leverages extensions to the theory of external approximation, allowing for the analysis of fully featured solid geometry without traditional meshing [35]. The software’s multi-pass adaptive analysis ensured solution accuracy, while its geometry decoupling capabilities facilitated the simulation of complex geometries.

Parameterized CAD models, corresponding to defined factor levels, were imported into SimSolid. Linear static analyses were performed for all simulations, with applied boundary conditions replicating operational constraints and loads simulating handle actuation. Structural stiffness was calculated as the ratio of the applied load to the resultant displacement [6,36] (Figure 6). The following steps were applied for each configuration:

Figure 6.

Simulation setup for structural analysis in Altair SimSolid. This free-body diagram highlights the applied boundary conditions, including the fixed constraints at the BIW attachment points and the 50 N pull force applied along the Y-axis at the handle fixation points. The image also indicates the zone where displacement was measured to calculate stiffness.

The BIW attachment points were fully constrained in all directions as boundary conditions. A load of 50 N was applied at the handle’s fixation points. Type 1 and Type 2 materials were used for each metallic support, as detailed in Table 3. The solver retained its default adaptive-refinement settings and ensured convergence via displacement stabilization between iterations.

Stiffness (K) was calculated from the simulation results using the following:

where F is the applied load, and δ is the displacement measured at the load application point.

K = F/δ,

3. Results

3.1. Stiffness Results from the Taguchi Inner–Outer Array

The Taguchi L16 inner array, combined with a two-level outer array for the noise factor (material type), resulted in 32 simulation cases. For each configuration, displacement was obtained from Altair SimSolid simulations, and stiffness (K, N/mm) was calculated as the ratio between the applied load (50 N) and the measured displacement at the handle fixation points. The larger-the-better S/N ratio was computed for each case to evaluate robustness against material variability. Results showed a wide range of stiffness values, confirming that geometric factor combinations strongly influence the structural performance of metallic supports, as presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of results from the Taguchi L16 inner–outer array.

The computational efficiency of this workflow was a key contributor to its practicality. The simulation time per configuration in the meshless SimSolid environment was approximately 2–3 min on a standard workstation, compared to an estimated 20–30 min for traditional FEA software that requires meshing. This represents a nearly 90% reduction in analysis time per design.

Component mass was calculated for each configuration based on material density and CAD model volume. The mass values for all 16 configurations are reported in Table 4, enabling analysis of the stiffness-to-weight trade-off.

Similarly, Sunanta et al. [37] proposed a Taguchi L27 orthogonal array for the optimization of forming process parameters for automotive advanced high-strength steel parts, where they found that Taguchi design of experiments (DOE) can be efficiently employed to analyze the influence of each process parameter, such as blank holder force, die gap, and blank width. In the same context, Lee et al. [32] found that stiffness and natural frequency can be optimized through a design of experiments (DOE), as demonstrated in their studies on automotive door tailor-welded blanks.

Combinations that included higher thickness, an optimal fixation-point distribution, and geometric reinforcements consistently yielded higher stiffness values. Conversely, configurations with minimal reinforcement or less favorable fixation layouts exhibited lower stiffness. These observations align with the CAD-based comparative analysis, which indicates that support from production vehicles with such features tends to improve load distribution and reduce displacement.

3.2. Identification of Optimal Configuration

The configurations that achieved the highest stiffness values in the Taguchi analysis were Runs 9, 11, and 13. Among these, run 11 exhibited the best performance, with a stiffness value of 248 N/mm, well above the minimum requirement of 50 N. These results show that different combinations of feasible geometric factor levels can yield superior structural performance; however, the identified optimal setup combines high stiffness with robustness against the noise factor. This configuration, derived from production-feasible designs, was validated through the DOE–CAE workflow, confirming the efficiency of the robust design approach.

The optimal configuration corresponded to the highest S/N ratio, indicating both maximum stiffness and robustness to material variability. This configuration was derived directly from the feasible factor levels identified in the CAD comparison and validated through the DOE–CAE workflow. The improvement confirms that applying a structured Taguchi approach can rapidly converge to robust designs without the need for exhaustive full-factorial testing. Similar results were presented by Park and Dang [38] in their studies of structural optimization based on CAD-CAE integration, which found that the application of CAD-CAE computer-aided tools combined with other techniques can be used to improve designs, as was presented in this research work, which combined Taguchi design of experiments (DOE) with CAD-CAE computer-aided tools.

Factor Effect Analysis

To quantitatively determine the influence of each geometric factor on the structural stiffness, an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed on the results. The percentage contribution of each factor, derived from the ANOVA, is presented in Table 5 and visually summarized in the Main Effects Plot (Figure 7).

Table 5.

ANOVA results showing the percentage contribution of each control factor to structural stiffness.

Figure 7.

Main effects plot for stiffness. The plot shows the average stiffness at the low and high levels for each control factor (F1–F8). The slope of each line indicates the magnitude of the factor’s effect on structural performance, with steeper slopes indicating a stronger influence. Factors F1 (Thickness) and F3 (Distance between handle fixation points) show the strongest positive effects, while F8 (Geometric Locators) shows a strong negative effect within the studied range.

The analysis reveals that factor F1 (Thickness) was the most influential, accounting for 42.1%. This is consistent with fundamental mechanics, as bending stiffness is proportional to the cube of the thickness. The second most significant factor was F6 (Geometric Reinforcements), contributing 15.0%. The addition of ribs and gussets drastically increases the moment of inertia of the cross-sections, reducing deformation under load. Factor F8 (Geometric Locators) also showed a notable influence (8.6%), as these features improve load transfer and stability by preventing localized twisting or shifting.

In contrast, factors such as F7 (Angle) and F2 (Handle Fixation Points) demonstrated a relatively minor influence within the ranges studied. This hierarchy of factor importance aligns with findings from other automotive structural optimization studies, which consistently identify global parameters such as thickness and primary reinforcement strategies as dominant drivers of performance [5,26].

The statistical significance of these factors was confirmed using an F-test, with F1 (p = 0.001), F6 (p = 0.018), and F3 (p = 0.023) all demonstrating significance at the 95% confidence level. Factor F8 was marginally significant (p = 0.050). The relatively low error contribution (11.6%) indicates that the selected geometric factors effectively capture the primary mechanisms governing structural stiffness, validating the experimental design.

The Main Effects Plot for mean stiffness (Figure 7) provides a visual confirmation of the ANOVA results. Factor F1 (Thickness) exhibits the steepest positive slope, demonstrating that increasing the thickness from 1.0 mm to 1.2 mm results in the largest improvement in stiffness, from 46.8 N/mm to 96.5 N/mm. Similarly, Factors F3 (Distance between handle fixation points) and F6 (Geometric Reinforcements) show substantial positive effects. In contrast, Factor F8 (Geometric Locators) shows a significant negative slope, indicating that, within the constraints of this study, adding locators reduces stiffness. Interestingly, Factor F7 (Angle) shows a nearly flat line, confirming its negligible impact as identified by the ANOVA. This graphical representation aligns perfectly with the percentage contributions in Table 4, providing an intuitive understanding of how each geometric parameter influences the structural performance of the support.

3.3. Validation with Traditional FEA

To validate the accuracy of the meshless simulations performed in Altair SimSolid, a comparative study was conducted using the traditional Finite Element Method (FEM) in ANSYS 2023 R2 Mechanical. Four representative configurations from the Taguchi L16 array were selected for this purpose: the Baseline (Run 1), the Optimal (Run 11), and two Intermediate designs (Run 9 and Run 13).

In ANSYS Workbench, each model was meshed. A mesh independence study was performed, progressively refining the mesh size until the change in maximum displacement was less than 2%. The final converged mesh consisted of approximately 340,500 nodes and 191,475 elements. The same boundary conditions and material properties defined in Section 2.4 were applied.

The results of this comparative analysis are summarized in Table 6. The stiffness values predicted by SimSolid showed excellent agreement with those from traditional FEA. The percentage discrepancy was calculated for each configuration, with the maximum value being only 1.6% for the Intermediate Run 13. For the critical Optimal design (Run 11), the discrepancy was a mere 0.55%. This close correlation, with all discrepancies well below 2%, falls within the acceptable accuracy range for engineering design and aligns with independent validation benchmarks for SimSolid [27,39,40]. Therefore, the use of the meshless solver for the screening and optimization of these thin-walled metallic components is validated, confirming that the computational efficiency gains do not compromise result accuracy.”

Table 6.

Comparison of stiffness results between Altair SimSolid and traditional FEA (ANSYS Mechanical).

3.4. Comparison with Baseline Designs

Compared with baseline support from the CAD dataset, the optimal configuration exhibited superior stiffness in numerical simulation. This improvement, obtained without altering manufacturability constraints, demonstrates the potential of integrating CAD-based benchmarking with robust design methods in early development stages.

Figure 8 presents a direct comparison between the baseline configuration (Run 1, all factors at the low level) and the optimal configuration determined through the Taguchi DOE. In terms of stiffness, the baseline configuration exhibited a value of 39 N/mm, whereas the optimal configuration reached 248 N/mm, representing a substantial increase in the structural performance of the metallic support. The use of tools such as CAD, CAE, and DOE enabled the identification of this configuration without the need for multiple virtual iterations, thereby validating the hypothesis that the design can be optimized from the early stages of development. The graph provides a clear visualization of this improvement, quantitatively confirming the methodological approach’s benefit.

Figure 8.

Comparison of stiffness between the baseline and optimal configurations. This graph provides a direct visual comparison of the structural performance of the baseline design (Run 1) and the optimal configuration (Run 11) identified using the Taguchi method. The optimal design achieved a stiffness of 248 N/mm, a substantial improvement over the baseline’s 39 N/mm. This represents a 635% increase in rigidity, validating the proposed methodological approach for optimizing structural performance in early design stages.

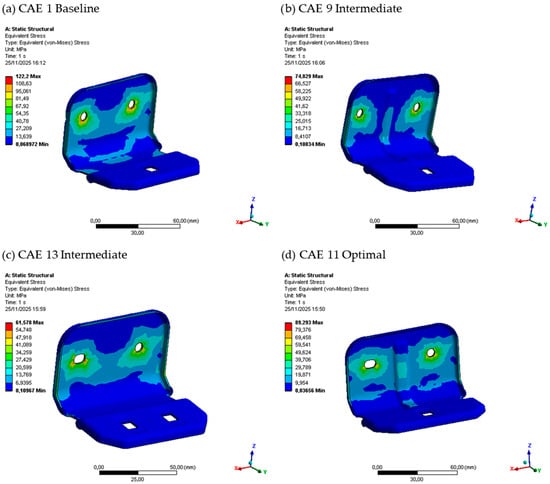

3.5. Stress Distribution Analysis

To ensure the structural integrity of the optimized design, a stress analysis was performed. The von Mises stress distributions for the baseline (Run 1) and optimal (Run 11) configurations under the 50 N load are presented in Figure 9. The maximum stress values and corresponding safety factors, calculated based on the yield strength of Material Type 1 (σy = 252 MPa), are summarized in Table 7.

Figure 9.

Von Mises stress distribution for (a) the baseline configuration (Run 1), (b) intermediate configuration (Run 9), (c) intermediate configuration (Run 13), and (d) the optimal configuration (Run 11) under a 50 N load. The optimal design exhibits a higher stress magnitude, consistent with its increased stiffness, but the stress remains well below the material’s yield strength. Stress concentrations are located at geometric discontinuities such as fillets and reinforcement junctions, which are typical in stamped metallic components.

Table 7.

Von Mises Stress and Safety Factors for Selected Configurations.

For the baseline configuration, the maximum von Mises stress was 122.233 MPa. The optimal configuration exhibited a lower maximum stress of 89.220 MPa, concentrated at the junction between a new reinforcement and the main body.

The safety factor (SF) for each configuration was calculated as follows:

where σy is the material yield strength, and σmax is the maximum von Mises stress. The baseline design yielded a safety factor of 2.06, while the optimal design achieved a safety factor of 2.82.

SF = σy/σmax,

This analysis confirms that, while the high-stiffness optimal design leads to higher stress levels due to its greater load-bearing capacity, the calculated safety factor remains significantly above 1. This indicates that the optimal configuration does not incur a strength penalty severe enough to cause yielding under the specified operational load and is therefore structurally sound. The stress concentrations identified are typical for stamped metallic components and occur at expected geometric discontinuities.

4. Discussion

The proposed methodology, combining CAD benchmarking, Taguchi robust design, and CAE validation, is directly applicable to other structural automotive components. By focusing on manufacturable geometric factor levels, the approach minimizes design iterations, shortens development time, and ensures consistent performance despite material variability. The results quantitatively demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach: a 635% improvement in structural stiffness substantially exceeds performance gains reported in similar studies, such as the 68.9% reduction in sink marks for injection-molded door handles reported by Muhamat et al. [10]. Furthermore, the 87.5% reduction in computational effort achieved via the Taguchi L16 array highlights the methodology’s efficiency, making it feasible for complex industrial problems where full-factorial designs are prohibitive [25,26]. Several studies support the present findings, highlighting the importance of the Taguchi method, FEA (Finite Element Analysis), and CAD-CAE computational-aided tools in improving the process parameters of automotive components [38,41,42,43].

Based on the results of this study, a set of design guidelines has been established to improve the structural performance of metallic supports in automotive doors. These recommendations, summarized in Table 8, are based on analyses using CAD, CAE, and DOE tools and aim to optimize structural rigidity from the initial stages of development. The purpose is to provide guidelines that facilitate technical decision-making and contribute to the design of more efficient, robust, and suitable components for implementation in real-world manufacturing processes.

Table 8.

Recommended design guidelines for improving the structural rigidity of metallic door supports.

The proposed design guidelines synthesize the key findings of this study and establish specific geometric values that significantly improve the structural performance of metallic supports in automotive doors. These guidelines guide design toward more robust solutions from the early stages of development, minimizing the need for costly iterations and validations in later phases.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully developed and applied an integrated CAD-CAE–Taguchi methodology to optimize the geometry of metallic automotive door support for structural rigidity. The key innovations and findings are as follows:

- Novel Application: This work presents one of the first integral applications of the CAD-CAE–Taguchi framework, specifically the optimization of metallic door supports, which is an area previously largely unexplored compared to plastic components or general panels.

- Computational Efficiency: The use of the Altair SimSolid meshless solver was fundamental, eliminating the need for meshing and reducing simulation time to 2–3 min per design. Combined with the Taguchi L16 array, which reduced the number of required simulations by 93.75%, this approach resulted in an overall reduction in development time and computational effort by over 87.5% compared to a full-factorial design using traditional FEA, drastically shortening the development cycle.

- Performance Improvement: The methodology identified a robust optimal configuration that increased stiffness to 248 N/mm and a substantial 635% improvement over the baseline design (39 N/mm). This demonstrates the approach’s capacity to deliver dramatic performance gains from the early design stages.

Furthermore, the methodology successfully identified a design that provides an optimal balance between stiffness and mass, as evidenced by its position regarding Pareto-optimal development. Notably, the entire workflow is highly amenable to full automation via scripting, representing a promising future direction for high-throughput industrial implementation.

The proposed framework, which combines real-world production geometry with structured design of experiments and rapid simulation, is directly applicable to other automotive structural components.

A limitation of this study is the use of a two-level factorial design, which, while highly efficient for screening, does not capture potential nonlinear relationships or curvature effects between factor levels. This is particularly relevant for continuous variables such as thickness and critical distances. To address this and further refine the optimization, future work will employ Response Surface Methodology (RSM), such as a Central Composite Design, focusing on the most significant factors identified through ANOVA. This approach will enable the development of a second-order model to more accurately predict and optimize performance within the design space [37,41,42,43].

Future work will focus on extending the methodology to dynamic performance metrics, incorporating multi-objective optimization considering mass, and validating results through physical prototyping.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.-S., E.T.-M., J.M.-C. I.E.G., and M.d.Á.-M.; data curation, E.T.-M., J.A.B.-C., J.M.-C., I.P., M.Á.G.-L. and A.G.-S.; formal analysis, A.G.-S., V.H.M.-L., E.T.-M., J.A.B.-C., J.M.-C., I.P., M.Á.G.-L., and J.M.-C.; funding acquisition, A.G.-S., and M.d.Á.-M.; investigation, A.G.-S., V.H.M.-L., I.E.G., M.G.N.-R., and M.d.Á.-M.; methodology, A.G.-S., V.H.M.-L., J.M.-C., E.T.-M., I.E.G., and M.d.Á.-M.; project administration, A.G.-S., and M.d.Á.-M.; resources, E.T.-M., J.A.B.-C., J.M.-C., I.P., M.Á.G.-L. I.E.G., and M.d.Á.-M.; supervision, M.G.N.-R., I.E.G., and M.d.Á.-M.; validation, V.H.M.-L., J.M.-C., J.A.B.-C., I.P., M.Á.G.-L., E.T.-M., A.G.-S., I.E.G., and M.d.Á.-M.; visualization, A.G.-S., V.H.M.-L., J.A.B.-C., and M.Á.G.-L.; writing—original draft, A.G.-S., E.T.-M., J.M.-C., I.E.G., M.d.Á.-M.; writing—review and editing, V.H.M.-L., M.G.N.-R., E.T.-M., J.A.B.-C., J.M.-C., I.P., M.Á.G.-L., I.E.G., and M.d.Á.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

J. Mayén, and I.E. Garduño gratefully acknowledge support from the Secihti Investigadores por México program through project No. 674. V. H. Mercado–Lemus, and J. A. Betancourt gratefully acknowledge support from the SECIHTI Investigadores por México program through project No. 850.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, K.; Tang, L.; Wu, P. Research on Optimization of Injection Molding Process Parameters of Automobile Plastic Front-End Frame. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5955725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, D.; Pan, A. Integrated Lightweight Optimization Design of Wall Thickness, Material, and Performance of Automobile Body Side Structure. Struct. Multidisc Optim. 2024, 67, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Brooker, A.; Kleinbaum, S.; Gotthold, D. Lightweighting Cost Impacts on Market Adoption and GHG Emissions in U.S. Light-Duty Vehicle Fleet. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinda, G.P.; Matope, S. The Lighter the Better: Weight Reduction in the Automotive Industry and Its Impact on Fuel Consumption and Climate Change. In Proceedings of the 2nd African International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Harare, Zimbabwe, 7–10 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Salmani, H.; Khalkhali, A.; Ahmadi, A. Multi-Objective Optimization of Vehicle Floor Panel with a Laminated Structure Based on V-Shape Development Model and Taguchi-Based Grey Relational Analysis. Struct. Multidisc. Optim. 2022, 65, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Tan, D.; Lv, X.; Yan, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, X. Multi-Objective Topology Optimization of a Vehicle Door Using Multiple Material Tailor-Welded Blank (TWB) Technology. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2018, 124, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.R. Optimization in the Automotive Industry. In Optimization and Industry: New Frontiers; Pardalos, P.M., Korotkikh, V., Eds.; Applied Optimization; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; Volume 78, pp. 39–58. ISBN 978-1-4613-7953-9. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovics, D.; Barari, A. Customization of Automotive Structural Components Using Additive Manufacturing and Topology Optimization. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-C.; Nguyen, T.-D.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Lin, S.-X. Rapid Development of an Injection Mold with High Cooling Performance Using Molding Simulation and Rapid Tooling Technology. Micromachines 2021, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamat, W.A.N.W.; Mehat, N.M.; Kamaruddin, S. Multi-Objective Optimization of Injection-Molded Car Door Handles Using Taguchi Method and Grey Relational Analysis. Adv. Sustain. Technol. ASET 2025, 4, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Banu, M. Opportunities and Challenges in Metal Forming for Lightweighting: Review and Future Work. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 142, 110813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Sabirov, I.; Petrov, R.; Verleysen, P. Review of Performance of Advanced High Strength Steels under Impact. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2402016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.B.; Baptista, R.M.S.O.; Martins, P.A.F. Stamping of Automotive Components: A Numerical and Experimental Investigation. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2004, 155–156, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, W.; Long, S.; Zhou, M.; Li, C. Optimization of Stamping Process Parameters for Sustainable Manufacturing: Numerical Simulation Based on AutoForm. Sustainability 2025, 17, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wu, H.; Xue, F.; Guo, J.; Ran, J.; Gong, F. Structural Design of Stamping Die of Advanced High-Strength Steel Part for Automobile Based on Topology Optimization with Variable Density Method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 121, 8115–8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, K.; Xiao, F.; Yang, J. Application of Constitutive Model for High-Strength Steels in Automobile: A Review. Steel Res. Int. 2025, 96, 2400982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perka, A.K.; John, M.; Kuruveri, U.B.; Menezes, P.L. Advanced High-Strength Steels for Automotive Applications: Arc and Laser Welding Process, Properties, and Challenges. Metals 2022, 12, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Peixinho, N.; Costa, S.L. A Review of Sheet Metal Forming Evaluation of Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS). Metals 2024, 14, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D. Study of Injection Molding Process Simulation and Mold Design of Automotive Back Door Panel. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2022, 36, 2331–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-T.; Tasi, Z.-Y.; Ho, W.-H.; Chou, J.-H. Integrating Taguchi Method and Gray Relational Analysis for Auto Locks by Using Multiobjective Design in Computer-Aided Engineering. Polymers 2022, 14, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanke, S.R.S.; Shantha Raju, S.; Tejas, S.S.; Kolhapuri Srinivas, N.; Khot, M.B. A Review on Finite Element Modelling and Experimental Analysis of Crashworthiness Design of Automotive Body. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2024, 30, 471–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.G.; Rachchh, N.V. Meshless Method—Review on Recent Developments. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 26, 1598–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-P.; Wu, C.-T.; Guo, Y.; Botkin, M.E. A Coupled Meshfree/Finite Element Method for Automotive Crashworthiness Simulations. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2009, 36, 1210–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapna, D. Taguchi Based GRA-PCA Hybrid Optimization for the Forming of AL6061 Alloy in Automotive Applications. Sigma J. Eng. Nat. Sci-Sigma Müh Fen. Bil. Derg. 2022, 40, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruddin, S.; Khan, Z.A.; Foong, S.H. Application of Taguchi Method in the Optimization of Injection Moulding Parameters for Manufacturing Products from Plastic Blend. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2010, 2, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hinojosa, R.; Garcia-Herrera, J.E.; Arcos-Gutiérrez, H.; Navarro-Rojero, M.G.; Mercado-Lemus, V.H.; Betancourt Cantera, J.A. Optimization of Polymer Stake Geometry by FEA to Enhance the Retention Force of Automotive Door Panels. Adeletters 2025, 4, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apanovitch, V. Using Altair SimsolidTM Technology Overview. 2020. Available online: https://altair.com/docs/default-source/resource-library/altair_whitepaper_simsolid-technology-overview_10_30_2020.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Remigio-Reyes, J.O.; Garduño, I.E.; Rojas-García, J.M.; Arcos-Gutiérrez, H.; Ortigosa, R. Topology Optimization-Driven Design of Added Rib Architecture System for Enhanced Free Vibration Response of Thin-Wall Plastic Components Used in the Automotive Industry. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 123, 1231–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SimSolid Version 2022.1. Altair Engineering, Inc. Available online: https://altair.com/simsolid (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Goelke, M. Simulation Revolution with Altair SimSolidTM; Altair Engineering, Inc.: Troy, MI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Meng, G.; Wu, H.; Zuo, W. Bending Collapse of Dual Rectangle Thin-Walled Tubes for Conceptual Design. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 135, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Shin, J.-K.; Song, S.-I.; Yoo, Y.-M.; Park, G.-J. Automotive Door Design Using Structural Optimization and Design of Experiments. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part. D J. Automob. Eng. 2003, 217, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lu, C.; Liu, Z.; Shen, C.; Sun, M. Multi-Response Optimisation of Automotive Door Using Grey Relational Analysis with Entropy Weights. Materials 2022, 15, 5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NX Version 2306. Siemens Digital Industries Software. 2023. Available online: https://www.plm.automation.siemens.com/global/en/products/nx (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Martínez-González, J.A.; Juárez-Sosa, I.; Mercado–Lemus, V.H.; Arcos–Gutiérrez, H.; Garduño, I.E. Numerical Assessment and Characterization of Automobile High-Voltage Cable Coverings. Rev. Ci. Tec. 2024, 7, e335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D. Study on Automotive Back Door Panel Injection Molding Process Simulation and Process Parameter Optimization. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9996423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunanta, A.; Julsri, W.; Suranuntchai, S. Optimization of Forming Process Parameters for Automotive Advanced High Strength Steel Parts Using the Taguchi Method. Eng. J. 2024, 28, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-S.; Dang, X.-P. Structural Optimization Based on CAD–CAE Integration and Metamodeling Techniques. Comput.-Aided Des. 2010, 42, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Feng, H.; Lei, Q.; Zhou, J.; Lin, W.; Zhu, X. Analysis of Large Tooling Rigidity for SimSolid under Binding Constraints. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Automation and Intelligent Technology (ICAIT 2025); Zhou, J., Khoo Boon Chong, M., Eds.; SPIE: Wuhan, China; p. 16.

- Symington, I. The International Magazine for Engineering Designers & Analysts. 2020, pp. 32–44. Available online: https://www.symetri.fi/media/8d880946040c544/simsolid-verification-by-nafems.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Zhao, Y.; Dong, H.; Liang, H. Robust Design Optimization of Car-Door Structures with Spatially Varied Material Uncertainties. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8835267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bash, M.S. Design and Finite Element Analysis of a Car Door on Different Speeds, Different Materials. Int. J. Mech. Prod. Eng. Res. Dev. 2019, 9, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, K.C.; Patil, G.M.; Belkhede, A.A. Design and Analysis of Side Door Intrusion Beam for Automotive Safety. Thin-Walled Struct. 2020, 153, 106788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).