Abstract

The detection of metallic surface defects is an essential task to control the quality of industrial products. During the production of metal materials, several defect types may appear on the surface, accompanied by a large amount of background texture information, leading to false or missing detections during small-defect detection. Computer vision is a crucial method for the automatic detection of defects. Yet, this remains a challenging problem, requiring the continuous development of new approaches and algorithms. Furthermore, many industries require fast and real-time detection. In this paper, a lightweight deep learning model is presented for implementation on embedded devices to perform in real time. The YOLOX-Tiny model is used for detecting and classifying metallic surface defect types. The YOLOX-Tiny has 5.06M parameters and only 6.45 GFLOPs, yet performs well, even with a smaller model size than its counterparts. Extensive experiments on the dataset demonstrate that the proposed model is robust and can meet the accuracy requirements for metallic defect detection.

1. Introduction

For decades, automated surface defect detection has been a challenging problem attracting significant interest. The demand for high-quality, high-performance products necessitates accurate defect detection. This is crucial for ensuring the safety and reliability of manufactured goods, especially when used in critical infrastructure such as buildings or transportation systems, where it helps prevent failures. Furthermore, detecting defects early significantly boosts overall manufacturing productivity by avoiding operational interruptions and reducing production costs [1].

To optimize production and efficiently create products, real-time product quality measurement and data storage are crucial. This makes a defect inspection system, capable of detecting and classifying defects in real time, a key technology that could be used, for example, for the implementation of smart factories [2]. This technology is particularly important for several reasons. First, correctly classifying defects allows for analyzing the type of defect occurrence based on process conditions, which in turn optimizes those conditions. A second benefit is the ability to diagnose equipment failure through defect analysis. For example, in a rolling process, if a defect consistently appears within a certain cycle, it becomes possible to identify the particular roll causing the issue. Third, this technology enables determining product grade by evaluating the number and specific types of defects present, which directly guides the decision of whether a product meets customer requirements for shipment. Finally, this technology prevents faulty products from reaching customers, thereby minimizing claims and maximizing the company’s reliability. Despite its critical role, many manufacturers still depend on operator-led visual sampling rather than automated 100% real-time inspection. This approach hinders process optimization because sampled quality data lacks a time-synchronized operational context. Unlike offline sampling tests, real-time total inspection can proactively prevent mass defects. Furthermore, an automatic defect inspection system surpasses human inspectors in many ways. For example, it operates continuously for extended periods, delivers consistent results, and performs reliably even in challenging conditions such as high temperatures and dust. Consequently, automated vision-based defect detection systems have been widely researched across industries, such as transportation [3], renewable energies [4], civil infrastructure [5], hardwood flooring [6], printed circuit board [7], Mask Manufacturing Process [8], Leather products [9], and Steel products [10]. This technology has also been applied to metallic surfaces, as they are widely used in many industrial applications.

Especially in recent years, machine vision techniques for surface defect detection have been extensively investigated, extending beyond just metallic surfaces. These methods primarily fall into two categories: traditional image processing and machine learning (based on handcrafted features or shallow learning techniques). Traditional image processing methods detect and segment defects by identifying primitive attributes that reflect local anomalies. These methods can be further categorized into structural, threshold, spectral, and model-based approaches. Structural methods focus on analyzing the relationships between components or elements within an image rather than just their individual pixel values [11]. It aims to understand the overall structure and arrangement of features to identify and classify patterns, especially defects. The thresholding methods are based on techniques that simplify an image by converting it into a binary image [12,13]. Regarding spectral methods, they primarily leverage the fact that different materials and objects interact with light in unique ways across various wavelengths [14,15]. Model-based approaches, on the other hand, leverage mathematical and statistical models to understand, analyze, and manipulate images [16,17]. Instead of relying purely on data-driven patterns or simple pixel operations, these methods incorporate prior knowledge about the image formation process, the objects within the image, or the expected properties of the image data. Machine learning-based methods typically involve two stages: feature extraction and pattern classification. First, a feature vector is designed by analyzing the input image’s characteristics to describe the defect information. This vector is then fed into a pre-trained classifier model to determine if the image contains a defect [18,19]. Defect detection often involves designing a feature vector from the input image’s characteristics, which is then fed into a pre-trained classifier to determine the presence of defects. Common features include Local Binary Patterns, Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix, Histogram of Oriented Gradients, and other grayscale statistical features. However, despite achieving good results in various surface defect detection tasks, these algorithms are not directly applicable to metallic surfaces. Traditional methods frequently require multiple, defect-specific thresholds that are highly sensitive to lighting and background variations. New problems necessitate threshold adjustments or even algorithm redesign. Furthermore, handcrafted or shallow learning features often lack sufficient discriminative power for complex conditions, as these methods typically target specific scenarios, compromising adaptability and robustness in the aforementioned detection environment.

Recent advancements have shown that neural network methods yield excellent performance across a wide range of computer vision applications, such as natural scene classification, face recognition, fault diagnosis in machines, and aerial target tracking [20,21,22]. Defect detection methods utilizing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have also seen several proposals [23,24]. A flexible multi-layered deep feature extraction framework was proposed in [25], leveraging CNN and transfer learning to detect anomalies in datasets. In [26], a cascaded autoencoder (CASAE) architecture was designed to segment and localize defects. This cascading network transforms input defect images into pixel-wise prediction masks using semantic segmentation. Subsequently, a compact convolutional neural network (CNN) classifies the segmented defect regions into their specific classes. In [27], a U-Net-based CNN architecture was presented for metal surface defect detection. An automatic method for detecting and classifying defective areas on metal parts was presented in [28], which leverages an adaptive fusion of Faster R-CNN and shape from shading. An Automated Machine Learning System for Defect Detection on Cylindrical Metal Surfaces was proposed in [29]. In this case, the ability of three CNNs—VGG-16, ResNet-50, and MobileNet v1—to detect defects on metal surfaces was implemented and compared. A metal surface defect detection technology employing the You Only Look Once (YOLO) model is presented in [30]. An approach for Object Detection and Classification of Metal Polishing Shaft Surface Defects using Convolutional Neural Network Deep Learning was presented in [31]. An end-to-end CNN architecture, called the Fusion Feature CNN (FFCNN), is proposed in [32]. FFCNN comprises three modules: a feature extraction module (designed to extract features from different images), a feature fusion module, and a decision-making module. In [33], a method combining an improved ResNet50 and an enhanced Faster Region Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN) was proposed to reduce average running time and improve accuracy. A Steel Plate Surface Defect Detection method employing Dataset Enhancement and Lightweight Convolutional Neural Networks was proposed in [34]. In [35], a compact convolutional neural network (CNN)-based optical nondestructive inspection scheme was presented for high-volume metallic components.

As discussed, the development of machine learning and computer vision has led to a variety of proposed algorithms, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Thus, the continued development of new approaches is still required to keep improving this process. The purpose of this paper is to explore metal surface defect detection algorithms based on the YOLOX framework, aiming for fast, accurate, and automatic detection in real-time applications. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- -

- The use of the YOLOX-Tiny model for the detection and classification of metallic surface defect types;

- -

- Practical validation for real-world metallic surface inspection;

- -

- The perfect balanced results between speed and accuracy in defect detection.

With just 5.06 million parameters and 6.45 GFLOPs, the YOLOX-Tiny is a shrunk version of the YOLOXv4-Tiny, making it appropriate for embedded devices with limited memory and processing resources, such as mobile devices [36]. This shrunken model performs efficiently, even outperforming larger models. Extensive experiments on the dataset confirm the model’s robustness and its ability to meet the accuracy requirements for metallic defect detection.

2. Method

In recent years, several versions of YOLO algorithms for object detection have been proposed, achieving a good balance between detection accuracy and speed. In 2021, a YOLOX algorithm with an anchor-free design was proposed, drastically reducing model complexity compared to previous YOLO versions [37]. The anchor-free architecture simplifies both training and decoding. One version of the YOLOX architectures is the lightweight YOLOX-Tiny model that has a small structure size with fewer parameters, requiring lower hardware conditions. Fundamentally, YOLOX-Tiny is based on a specialized deep learning algorithm that employs convolutional and residual networks. This type of model is suitable for low-end GPUs and is valuable for real-time, practical object detection applications. In this type of application, YoloX-Tiny with an input size of 448 × 448 was implemented on the Jetson Nano and Jetson NX platforms, achieving latencies of 38.89 ms and 10.68 ms, respectively [38]. For both edge devices, the number of FPS was 25.71 on the Jetson Nano and 93.63 on the Jetson NX platform. It should be noted that Jetson NX is more powerful than Jetson Nano in terms of computational performance. Under the same lightweight model conditions, the Jetson Nano shows greater speed fluctuations than Jetson NX. The Yolox-Tiny model was also implemented on the NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano device for real-time inference in black ice detection with drones [39]. With an input image size of 416 × 416, YoloX-Tiny achieved 24 FPS during inference, thus meeting the 20 FPS criterion for real-time drone detection [40].

The performance of lightweight object detection models is usually lower than that of deep learning models with a larger architecture and more parameters. In recent years, particular attention has been given to deep learning object detection networks to improve the performance of these lightweight models [41,42].

2.1. Dataset

The adopted surface defect dataset is the GC10-DET dataset [43] collected in a real industry, which contains ten types of metal defects, namely, Punching hole, Welding line, Crescent gap, Water spot, Oil spot, Silk spot, Inclusion, Rolled pit, Crease, and Waist folding. These defects are present on the surface of the steel sheet. The dataset contains a total of 3570 grayscale images divided into ten different class folders available on the github [44].

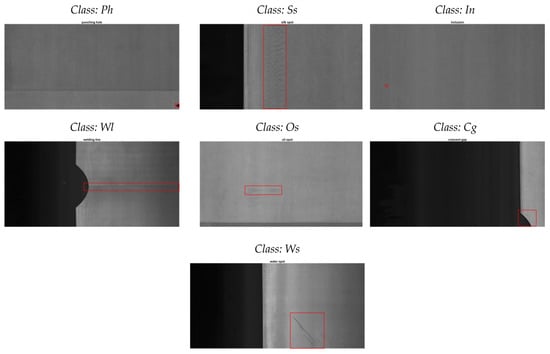

Due to an insufficient number of images for some defect types, the presented method detects only 7 of the faults represented in the database, which were obtained from 1878 high-resolution images [45]. The fault types detected and classified by the deep learning model are the Punching hole (Ph), Welding line (Wl), Crescent gap (Cg), Water spot (Ws), Oil spot (Os), Silk spot (Ss), and Inclusion (In). Figure 1 shows the randomly selected image samples of each defect type from the dataset. The characterization of each type of metal surface failure is described in [43]. The distribution of images per defect class is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Image samples from each class of the dataset. The red bounding box indicates the fault region.

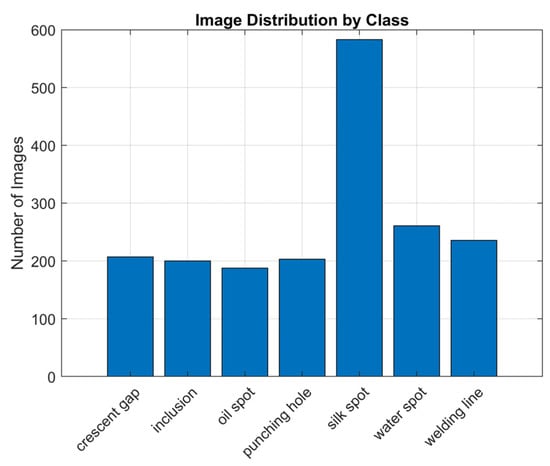

Figure 2.

Number of images for each type of defect.

From Figure 2, it can be seen that the dataset exhibits significant class imbalance, with silk spot representing 31% of all images, while oil spot or welding line constitutes only 10%.

2.2. Data Augmentation

Detailed information on small objects can be retained in high-resolution images. In real production environments, the accuracy and speed of defect detection are two main factors affecting production efficiency and quality. In order to further improve detection speed while maintaining approximately the same detection accuracy as the YOLOX-Tiny model for small-object defect areas on metal surfaces, its input image resolution is resized from 2048 × 1000 to 608 × 608 [43,45]. Reducing the image size increases the model processing speed and reduces the model inference time and memory footprint. These factors enable real-time deployment and model training on devices with more limited resources.

YOLOX uses two data augmentation techniques, namely Mosaic Data augmentation [46] and MixUp Data augmentation [47], improving its generalization ability to unseen data and to handle variations in real-world images. The Mosaic Data Augmentation technique blends multiple images into a single image. The resulting image can have a more balanced mix of classes, even if the dataset is imbalanced. Minority classes will appear in new visual contexts, helping the model improve their detection. The MixUp Data augmentation technique blends classes together, generating interpolated images. Images with the majority class are blended with the other classes, reducing the visual dominance of the majority class and increasing the indirect visibility of the other classes. Both augmentation techniques, while not altering the absolute number of samples in the dataset, mitigate the impact of data imbalance.

In order to restore the possible complexity of metal defect detection, we augmented the dataset by random rotation, scaling, and flipping.

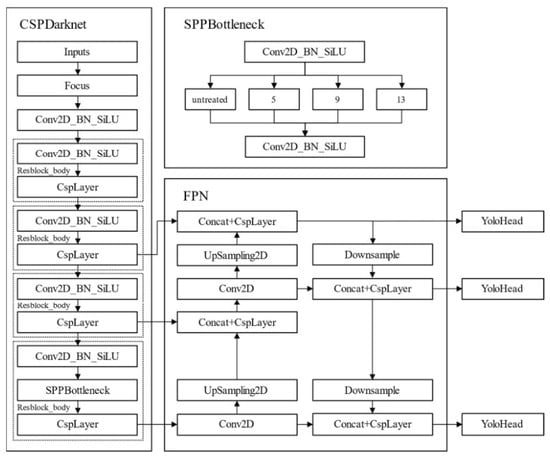

2.3. YOLOX-Tiny Architecture

The YOLOX architecture is divided into three parts: the backbone network, which extracts features from the input image; the neck that combines multi-scale features extracted from the backbone, allowing the model to learn from a wider range of scales; and the head that uses the extracted features to perform classification, localization, instance segmentation, and pose estimation tasks (Figure 3). At the end, a post-processing step, such as Non-maximum Suppression (NMS) [48], filters out overlapping predictions and retains only the most confident detections.

Figure 3.

YOLOX-Tiny network architecture [49].

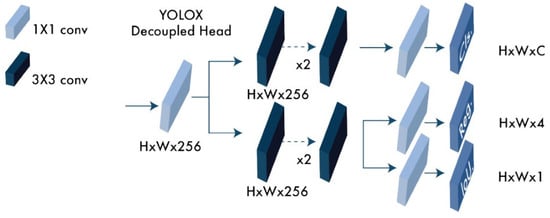

The backbone feature extraction network is the CSPDarknet network that uses a residual network architecture to initially extract feature layers of various sizes from the input image. In this network, there exists a large number of ordinary convolutions. In the feature-extraction network model, deeper layers contain richer semantic features; consequently, location information has been highly abstracted into semantic information. The YOLOX-Tiny utilizes the SPPBottleneck module, positioned between the convolutional layer and the CspLayer, to increase the model’s receptive field in the deep network while avoiding image distortion that often results from operations like cropping and scaling. The SPPBottleneck module processes the input data in parallel using maximum pooling layers of different sizes (5, 9, and 13), performing fusion afterward. This approach reduces the number of parameters, removes redundant information, and addresses the multi-scale problem of target detection. The output of the last three CspLayer in the CSPDarknet enters in the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) module to achieve feature fusion and obtain significant contextual features. In the FPN, the bottom-up and top-down paths are fused. The high-level features are then transmitted and combined using UpSampling2D. Finally, the predicted feature maps are obtained by down-sampling, which enhances the characterization of the backbone feature extraction network. The predicted feature maps of the FPN are input into the Yolo Head detection. The Yolo Head consists of Conv2D_BN_SiLU convolution modules. It starts with a 1 × 1 convolution layer to reduce the feature channel (to 256) and then adds two parallel branches, each with two 3 × 3 convolution layers. Using a large number of convolutions in the YOLOX-Tiny detection head increases the model’s complexity, but also improves its detection accuracy. The branch outputs include predictions for object type classification (Cls), regression (Reg) for the prediction box’s location, and objectness (Obj) that indicates the coordinates of the prediction box (Figure 4). Finally, these three outputs are integrated to generate comprehensive details about the target objects.

Figure 4.

YOLOX Decoupled Head diagram [48].

Using a decoupled detection head can effectively improve model accuracy, accelerate network convergence, and enhance its characterization ability. Since YoloX-Tiny uses an Anchor-free detector, it will directly predict the coordinates of the upper-left corner of the grid as well as the height and width of the prediction box, reducing the parameters and calculations of the detector. The detection pipeline becomes more straightforward and computationally efficient, which can accelerate inference speed. Since the model does not require anchors to have defined dimensions, the detection of objects with reduced dimensions and irregular shapes also improves.

2.4. Evaluation Index

To evaluate the performance of the model, several metrics are used to provide a comprehensive picture of the model’s performance in the detection and classification tasks. Those metrics include the precision (P), recall (R), F1-score (F1), mean average precision (mAP), and average precision (AP).

The precision is the relation between the number of samples correctly predicted by the model as true positives (TP) and the number of all samples predicted as positives (1).

Recall represents the ratio of correctly detected images and all testing images for each defect class (2).

F1-score is the harmonic average of precision and recall, and it is particularly useful for evaluating classification models on class-imbalanced datasets, where accuracy can be misleading (3).

For each class, predictions are ranked by confidence score (t), and the precision and recall are calculated at each rank (Pt and Rt). The average precision is the area under the precision-recall curve obtained from all the ranks (T) calculated separately for each class, c (4).

The mean average precision is the average of AP values across all classes, C, expressed as follows:

3. Results and Discussion

The experiments were performed with Matlab R2025a. To train and test the deep learning model, a machine with an Intel® Xeon multi-core processor with 16 GB DDR4/DDR5, a NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5090 GPU with 32 GB VRAM was used.

Of the 1878 images with defects on the metal surface from the GC10-DET dataset, 80% were split for training and 20% for testing, with class distribution maintained across both subsets. Table 1 presents the detailed distribution of images between the training and validation sets for each defect type.

Table 1.

Subsets of images for training and testing.

As there may be more than one defect in an image, there may be several detections in a single image. The number of bounding boxes for each defect type in both subsets is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Subsets of bounding boxes for training and testing.

In view of enlarging our training set to increase variability and model generalization, we incorporate several data augmentations, including random flips using the horizontal and vertical axis, resizing from 0.8 to 1.5, and random rotation ranging from −15° to 15°.

The YOLOX-Tiny configuration is described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Model parameters setup.

Table 4 describes the configuration parameters that define the environment in which the training process takes place

Table 4.

Training Setup.

The selection of training hyperparameters is important in deep learning model development, influencing their training convergence and overall model performance. A sensitivity analysis was conducted through comparative experiments for different learning rates while keeping the dataset, number of iterations, and hardware configurations unchanged. The results of the experiments are shown in Table 5, indicating that the highest mean average precision value was obtained for a learning rate equal to 0.0001.

Table 5.

Experimental results at different learning rates.

Since their optimization is often computationally expensive, especially when dealing with large-scale datasets, in YOLOX-Tiny, the other hyperparameter values were set based on domain expertise (Table 6).

Table 6.

Hyperparameter settings.

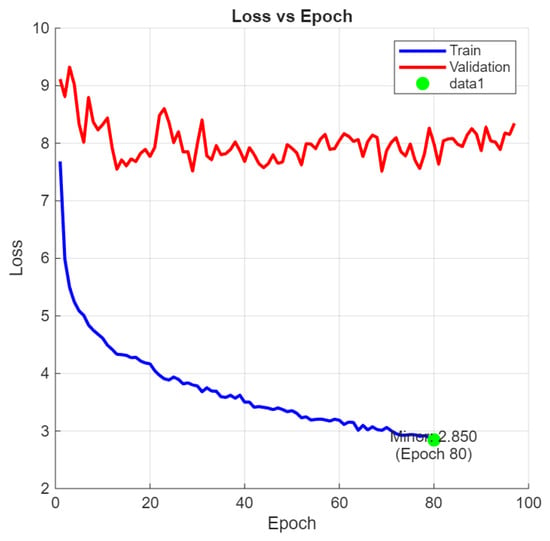

Figure 5 illustrates the YOLOX-Tiny model training convergence, showing stable learning progression over 80 epochs without signs of overfitting. Since the Loss curve continued to decrease upon completion of training, increasing the number of epochs may improve overall results.

Figure 5.

Loss training progress.

3.1. Global Performance Analysis

The YOLOX-Tiny detector achieved robust performance across the seven defect classes, with a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 0.8375 at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.2. The IoU measure assesses the quality of the predicted bounding boxes in the defect detection. This metric is determined by the ratio between the areas resulting from the intersection and the union of the ground truth bounding box and the predicted bounding box. A higher IoU value indicates that there is greater overlap between the ground truth bounding box and the predicted bounding box, resulting in better quality defect detection. The global performance metrics obtained by the model are shown in Table 7 and demonstrate their effectiveness.

Table 7.

Global metric results.

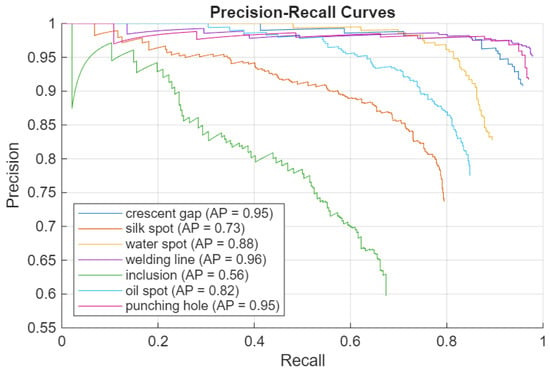

3.2. Per-Class Analysis

When handling multiple object classes, the models must identify and localize multiple object classes in each image. This is addressed by the average precision metric (AP) by calculating separately the average precision for each class. This metric allows the model’s performance to be evaluated for each class individually, providing a more comprehensive assessment of the model’s overall performance. A higher AP value means higher recognition accuracy and better performance of the model. Individual class performance revealed significant variations correlated with defect visual characteristics. Table 8 shows the performance metrics for each defect type.

Table 8.

Metric results for each class.

The main difficulty lies in recognizing silk spots and inclusion defects, which yielded average accuracies of 0.73 and 0.56, respectively. The explanation for this could be that the inclusion defects on the surface are often on a tiny scale that can be confused with the background noise. Regarding the silk spot defect, the model has difficulty identifying it when the defect lacks sufficient contrast with the background.

While the recognition of oil spots and water spots is superior to the previously mentioned defects, neither achieves an average precision of 0.90. This can be justified by the fact that the hue of oil spots and water spots occasionally approximates the background color, making distinction difficult. When this occurs, the model struggles to successfully determine which defect is present on the metal surface.

There is a trade-off between precision and recall, where increasing the number of detected objects (higher recall) may result in more false positives (lower precision). To deal with this, there exists the precision-recall curve that shows the precision against recall for different confidence thresholds. This metric provides a balanced assessment of precision and recall by considering the area under the precision-recall curve. Model performance will be better when the P-R curve is closer to the upper right corner. The precision-recall curves for each defect type are shown in Figure 6. The area under the P-R curve represents the AP value for each defect type, and a larger area means a larger AP value of the model. It can be seen from the test results that a higher area under the curve was obtained in the punching hole, welding line, and crescent gap defects with an AP value of 0.953%, 0.964%, and 0.947%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Average Precision–Recall (P-R) curves for each defect class.

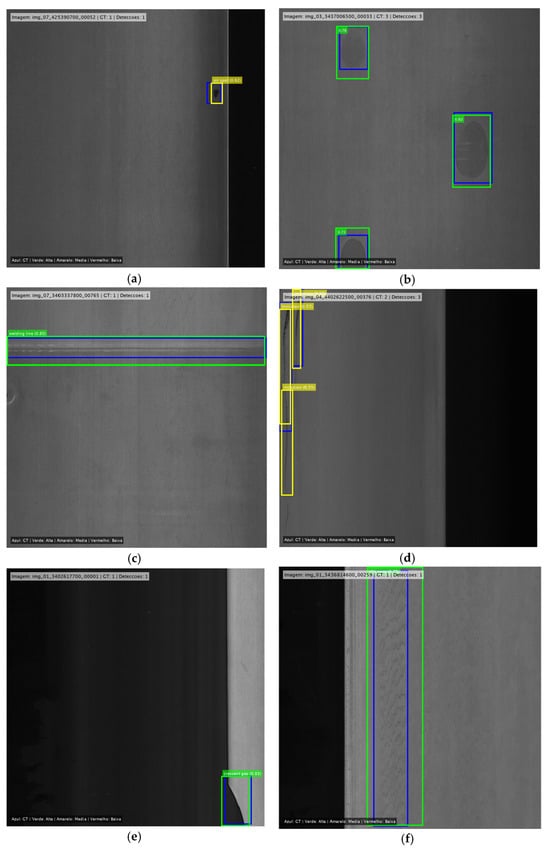

3.3. Detection Results

The images in Figure 7 show the detection effect of the YOLOX-Tiny model for different defect types. The proposed system uses color-based visual codification to facilitate the analysis of the results. This approach permits easy evaluation of the model prediction at the defect location and the corresponding confidence level. The blue bounding box represents the location of real defects in the metallic surface. The green bounding box represents the model detection with higher confidence (Conf > 0.7). The yellow and red bounding box represents the model detection with mean confidence (0.4 < Conf < 0.7) and lower confidence (0.3 < Conf < 0.4), respectively. Figure 7a–f shows some test results of the model prediction. In Figure 7b,d, it is possible to verify the presence of a defect in more than one location in the image (blue bounding boxes), with the proposed model detecting it for each location (green or yellow bounding boxes).

Figure 7.

Defect detection for different confidence levels. (a) oil spot defect; (b) water spot defect; (c) welding line defect; (d) inclusion defect; (e) crescent gap defect; (f) silk spot defect.

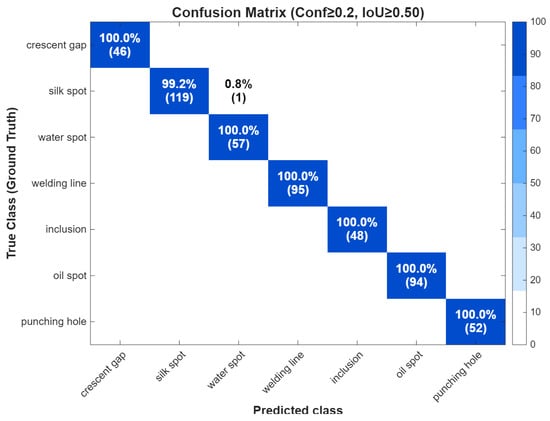

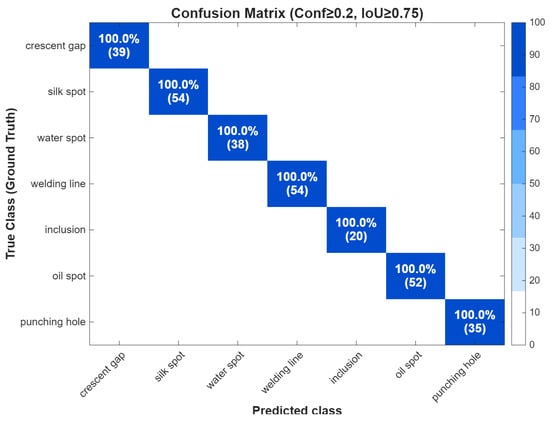

The obtained confusion matrix, considering a confidence greater than or equal to 0.2, is shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9. These figures present the confusion matrices for a confidence level of 0.2, using an IoU of 0.5 and 0.75, respectively. It is worth noting that the confusion matrices only account for successful detections. These successes are defined as detections where the confidence level is ≥0.2 and the Intersection over Union (IoU) between the prediction and the ground truth is ≥0.5 (for Figure 8) or ≥0.75 (for Figure 9). Figure 8 shows that the model made 511 total detections of defects out of a total of 569 defects present in the test images (Table 2). From the results presented in the confusion matrix for an IoU ≥ 0.5, it can be seen that the proposed model has difficulty only classifying the type of silk spot defect, occasionally confusing it with the type of water spot defect. Figure 9’s confusion matrix shows that the total number of defect detections made by the model (292) is smaller than the previous count, given the 569 total defects in the test images. For an IoU ≥ 0.75, the confusion matrix indicates that, among successful detections, the model had no difficulty identifying the seven defect types. The defect shown in Figure 8, which the model incorrectly classified as a water spot, is no longer successfully detected when the IoU ≥ 0.75, causing it to disappear from the confusion matrix in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix for IoU of 0.50.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix for IoU of 0.75.

An increase in the number of successful detections will lead to a corresponding rise in the number of occurrences in the confusion matrices. In order to improve the accuracy in detecting silk spots, oil spots, and water spots defects, it will be interesting to increase the contrast of the images in advance so that their hues are clearly distinguished from the background hue. According to Shaoshu Gao et al., as with inclusion defects, there are also a large number of small oil spot defects [45]. With the image resizing performed to fit the model, the defects become even smaller and, in some situations, difficult to detect. To resize the image without reducing the size of the defects, it would be interesting to first apply a contour detection algorithm and then crop the image, ensuring that no detected contours are eliminated.

3.4. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Algorithms

To verify the advancement of the used model in this paper, we conducted a comparative experiment with other detection models, including SSD and Faster-RCNN, representing the current classical single-stage and two-stage object detection networks, respectively. In order to compare the performance of various models, several metrics were used in the experiment, including mAP for multi-class defects, FLOPs, and the number of parameters (NParams).

Table 9 shows the results obtained from different methods on the GC10-DET image dataset. The mAP values presented correspond to the detection of the same seven types of defects on metal surfaces. The proposed lightweight YOLOX-Tiny model achieves a higher accuracy (0.8375) in detecting the seven defects compared to the other analyzed methods. Compared with the two-stage representative Faster-RCNN, our model improves detection accuracy by 0.2161 mAP, and it improves detection accuracy by 0.1647 mAP compared to the other one-stage representative algorithm, SSD. Regarding computational cost, the YOLOX-Tiny model features 13.8 GFLOPs and 5.06 M parameters. Compared to other models, this makes it one of the fastest, with the lowest memory usage, ideal for use on low-resource devices and in real-time applications.

Table 9.

Experimental results of different methods on the GC10-DET dataset.

3.5. Ablation Experiment

To further prove the efficacy of our method, we carry out ablation experiments on the GC10-DET dataset. We evaluate the effectiveness of the L2 regularization parameter (λ) in the model’s learning process for defect detection. Choosing a very small λ can lead to overfitting the model to the training data. If the parameter is too large, the model may lose its ability to capture complex patterns. In lightweight models like YOLOX-Tiny, a large λ parameter can weaken gradients and reduce sensitivity in detecting small defects. Choosing an intermediate value for the parameter enables the model to better detect small defects. The results of the experiments, presented in Table 10, validate the selection of 1 × 10−4 for the L2 regularization parameter in the loss function.

Table 10.

Effect of L2 Regularization Ratio on the GC10-DET Dataset.

Table 11 shows the performance metrics for the inclusion defect type. This type of defect appears frequently in the GC10-DET Dataset, but its reduced size makes it difficult to detect. For this type of defect, it is observed that as the L2 regularization parameter increases, the precision metric decreases and the recall metric increases. The model incorrectly detects more regions as containing the defect (more false positives) but correctly classifies more regions as having the defect (fewer false negatives). The model exhibits optimal precision and balance with an L2 regularization parameter value of 1 × 10−4. This corresponds to accurate detection of the existing defect, resulting in fewer false positives and false negatives, and consequently, a higher AP value (0.56318).

Table 11.

Effect of L2 Regularization Ratio on the inclusion defect type.

4. Conclusions

This paper successfully demonstrates the application of the YOLOx architecture for automated detection of surface defects in metallic plates. The methodology achieved robust performance, with mAP of 0.8375, validating the approach for industrial-quality control applications. The comprehensive evaluation revealed that defects with well-defined visual characteristics, such as crescent gaps, welding lines, and punching holes, achieve excellent detection rates (AP > 0.900), whereas subtle defects present ongoing challenges requiring future research attention. The conservative detection, which favors precision over recall, aligns well with industrial requirements.

The main contributions of this paper include a comprehensive evaluation across seven defect types, a practical validation for real-world metallic surface inspection, and the demonstration of the YOLOX-Tiny model’s effectiveness in real-time industrial applications. The obtained results show a perfect balance between speed and accuracy in defect detection.

The developed system establishes a solid foundation for automated metallic surface inspection, contributing both methodological frameworks and practical solutions for industrial implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.A.V., T.G.A. and V.F.P.; Methodology, J.D., M.F.C. and P.M.A.V.; Software, J.D. and M.F.C.; Formal analysis, P.M.A.V., T.G.A. and V.F.P.; Investigation, J.D., M.F.C. and P.M.A.V.; Resources, P.M.A.V. and V.F.P.; Writing—original draft, J.D. and M.F.C.; Writing—review & editing, P.M.A.V., T.G.A. and V.F.P.; Visualization, P.M.A.V., T.G.A. and V.F.P.; Supervision, P.M.A.V. and T.G.A.; Project administration, T.G.A. and V.F.P.; Funding acquisition, V.F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CASAE | Cascaded Autoencoder |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| Faster R-CNN | Faster Region Convolutional Neural Network |

| FFCNN | Fusion Feature CNN |

| GFLOPs | Giga Floating-Point Operations Per Second |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Robinson, S.L.; Miller, R.K. Automated Inspection and Quality Assurance; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1989; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, D.; Andrade, E.; Rativa, D.; Maciel, A.M.A. Fault Detection and Diagnosis in Industry 4.0: A Review on Challenges and Opportunities. Sensors 2025, 25, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Harsha, S.P. A systematic literature review of defect detection in railways using machine vision-based inspection methods. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 18, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, T.G.; Pires, V.F.; Pires, A.J. Fault Detection in PV Tracking Systems Using an Image Processing Algorithm Based on PCA. Energies 2021, 14, 7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Georgieva, K.; Kasireddy, V.; Akinci, B.; Fieguth, P. A review on computer vision based defect detection and condition assessment of concrete and asphalt civil infrastructure. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2015, 29, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; Xia, J.; Jeong, Y.; Yoon, J. An automatic machine vision-based algorithm for inspection of hardwood flooring defects during manufacturing. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123 Pt A, 106268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, J.; Ding, G.; Qin, S. Review of vision-based defect detection research and its perspectives for printed circuit board. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 70, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Jeong, J. Design and Implementation of Machine Vision-Based Quality Inspection System in Mask Manufacturing Process. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Deng, J.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y. A Systematic Review of Machine-Vision-Based Leather Surface Defect Inspection. Electronics 2022, 11, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.A.M.S.; Tapamo, J.-R. A Survey of Vision-Based Methods for Surface Defects’ Detection and Classification in Steel Products. Informatics 2024, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.H.; Asemani, D. Surface defect detection in tiling Industries using digital image processing methods: Analysis and evaluation. ISA Trans. 2014, 53, 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, M.; Bushroa, A.R.; Hassan, M.A.; Hilman, N.M.; Ide-Ektessabi, A. A Contrast Adjustment Thresholding Method for Surface Defect Detection Based on Mesoscopy. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2015, 11, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.F. Automatic thresholding for defect detection. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 1644–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, H.G.; Huang, X.B.; Wang, J.; Chen, X. Detection of fabric defects by auto-regressive spectral analysis and support vector data description. Text. Res. J. 2010, 80, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuewu, Z.; Fang, G.; Lizhong, X. Inspection of surface defects in copper strip using multivariate statistical approach and SVM. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. 2012, 43, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alata, O.; Ramananjarasoa, C. Unsupervised textured image segmentation using 2-D quarter plane autoregressive model with four prediction supports. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2005, 26, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kaur, M. Machine vision system for automated visual inspection of tile’s surface quality. IOSR J. Eng. 2012, 2, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Yan, Y. A noise robust method based on completed local binary patterns for hot-rolled steel strip surface defects. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 285, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondronasios, A.; Popov, I.; Jordanov, I. Feature selection for surface defect classification of extruded aluminum profiles. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 83, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemavhola, A.; Chibaya, C.; Viriri, S. A Systematic Review of CNN Architectures, Databases, Performance Metrics, and Applications in Face Recognition. Information 2025, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.-S.; Fu, S.; Lin, L. A novel gas turbine fault diagnosis method based on transfer learning with CNN. Measurement 2019, 137, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gong, H.; Wang, X.; Sun, P. Aerial Target Tracking Algorithm Based on Faster R-CNN Combined with Frame Differencing. Aerospace 2017, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbajin, E.; Rodrigues, N.; Costa, P.; Miragaia, R.; Frazão, L.; Costa, N.; Fernández-Caballero, A.; Carneiro, J.; Buruberri, L.H.; Pereira, A. A Systematic Review on Deep Learning with CNNs Applied to Surface Defect Detection. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usamentiaga, R.; Lema, D.G.; Pedrayes, O.D.; Garcia, D.F. Automated Surface Defect Detection in Metals: A Comparative Review of Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation Using Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 4203–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, V.; Hung, T.Y.; Vaikundam, S.; Chia, L.T. Convolutional networks for voting-based anomaly classification in metal surface inspection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology, Toronto, ON, Canada, 22–25 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, X.; Zhang, D.; Ma, W.; Liu, X.; Xu, D. Automatic Metallic Surface Defect Detection and Recognition with Convolutional Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalenko, I.; Maruschak, P.; Brezinová, J.; Prentkovskis, O.; Brezina, J. Research of U-Net-Based CNN Architectures for Metal Surface Defect Detection. Machines 2022, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamet, F.; Cakar, S.; Kotan, M. Automatic Detection and Classification of Defective Areas on Metal Parts by Using Adaptive Fusion of Faster R-CNN and Shape From Shading. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 126030–126038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Hung, K.-C.; Lin, J.-C. Automated Machine Learning System for Defect Detection on Cylindrical Metal Surfaces. Sensors 2022, 22, 9783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L. Metal Surface Defect Detection Using Modified YOLO. Algorithms 2021, 14, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Tan, D.; Li, Y.; Ji, S.; Cai, C.; Zheng, Q. Object Detection and Classification of Metal Polishing Shaft Surface Defects Based on Convolutional Neural Network Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Xiang, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, L.; Lin, L.; Yin, G. FFCNN: A Deep Neural Network for Surface Defect Detection of Magnetic Tile. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 3506–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xia, X.; Ye, L.; Yang, B. Automatic Detection and Classification of Steel Surface Defect Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Metals 2021, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Huang, X.; Ren, Y.; Huang, Y. Steel Plate Surface Defect Detection Based on Dataset Enhancement and Lightweight Convolution Neural Network. Machines 2022, 10, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borwankar, R.; Ludwig, R. A Novel Compact Convolutional Neural Network for Real-Time Nondestructive Evaluation of Metallic Surfaces. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 8466–8473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. Scaled-YOLOv4: Scaling Cross Stage Partial Network. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2011.08036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, J. YOLOX: Exceeding YOLO Series in 2021. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.08430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Min, X.; Hu, R.; Long, Y.; Luo, H.; JunYi. FasterX: Real-Time Object Detection Based on Edge GPUs for UAV Applications. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2022, arXiv:2209.03157. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.; Moon, J.; Han, S.; Shin, D. Real-Time Black Ice Detection in Drone View Using YOLOX. J. Stud. Res. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chee, J.H.; Feroskhan, M. Real-Time Multi-Drone Detection and Tracking for Pursuit-Evasion With Parameter Search. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 6027–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, X.; Duan, F.; Jiang, J.; Fu, X.; Gan, L. Deep metallic surface defect detection: The new benchmark and detection network. Sensors 2020, 20, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://github.com/lvxiaoming2019/GC10-DET-Metallic-Surface-Defect-Datasets (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Gao, S.; Chu, M.; Zhang, L. A detection network for small defects of steel surface based on YOLOv7. Digit. Signal Process. 2024, 149, 104484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Duan, C.; Song, X.; Tian, Y.; Wang, H. AMRNet: Chips Augmentation in Aerial Images Object Detection. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2020, arXiv:2009.07168. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cisse, M.; Dauphin, Y.N.; Lopez-Paz, D. Mixup: Beyond Empirical Risk Minimization. Mach. Learn. 2017, arXiv:1710.09412. [Google Scholar]

- Terven, J.; Cordova-Esparza, D. A Comprehensive Review of YOLO Architectures in Computer Vision: From YOLOv1 to YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2023, 5, 1680–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, H.; Bai, S.; Yu, Y.; Duan, Q. Image Recognition and Classification of Farmland Pests Based on Improved Yolox-Tiny Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Li, H.; Xue, X.; Liu, H. Research on a Metal Surface Defect Detection Algorithm Based on DSL-YOLO. Sensors 2024, 24, 6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Zhou, H.; Chen, R. SDMS-YOLOv10: Improved Yolov10-based algorithm for identifying steel surface flaws. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H. RSTD-YOLOv7: A steel surface defect detection based on improved YOLOv7. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Huang, M.; Gao, Z.; Cao, Z.; Cao, P. MSC-DNet: An efficient detector with multi-scale context for defect detection on strip steel surface. Measurement 2023, 209, 112467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kong, F.; Wang, R.; Luo, T.; Shi, Z. EFD-YOLOv4: A steel surface defect detection network with encoder-decoder residual block and feature alignment module. Measurement 2023, 220, 113359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. 2017, 42, 318–327. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Q.; Han, Y.; Zhao, M. DsP-YOLO: An anchor-free network with DsPAN for small object detection of multiscale defects. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2024, 241, 122669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, S.M.; Ahn, H. Faster Metallic Surface Defect Detection Using Deep Learning with Channel Shuffling. Computers Mater. Contin. 2023, 75, 1847–1861. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, X.; Liu, S.; Cheng, K.; Qian, Y. Development of a YOLO-V3-based model for detecting defects on steel strip surface. Measurement 2021, 182, 109454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).