Abstract

Combustion at the meso-scale is constrained by large surface-to-volume ratios that shorten residence time and intensify wall heat loss. We perform steady, three-dimensional CFD of two asymmetric vortex combustors: Model A (compact) and Model B (larger-volume) over inlet-air mass flow rates

(40–170 mg s−1) and equivalence ratios ϕ (0.7–1.5), using an Eddy-Dissipation closure for turbulence–chemistry interactions. A six-mesh independence study (the best mesh is 113,133 nodes) yields ≤ 1.5% variation in core fields and ~2.6% absolute temperature error at a benchmark station. Results show that swirl-induced CRZ governs mixing and flame anchoring: Model A develops higher swirl envelopes (S up to ~6.5) and strong near-inlet heat-flux density but becomes breakdown-prone at the highest loading; Model B maintains a centered, coherent Central Recirculation Zone (CRZ) with lower

(~3.2 m s−1) and S ≈ 1.2–1.6, distributing heat more uniformly downstream. Peak flame temperatures (~2100–2140 K) occur at ϕ ≈ 1.0–1.3, remaining sub-adiabatic due to wall heat loss and dilution. Within this regime and

≈ 85–130 mg s−1, the system balances intensity against flow coherence, defining a stable, thermally efficient operating window for portable micro-power and thermoelectric applications.

1. Introduction

The demand for compact and high-efficiency energy sources has driven the advancement of micro- and meso-scale combustion systems, particularly for portable power generation and thermoelectric applications like MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) [1,2]. Compared to conventional batteries, combustion-based micro power systems [3] offer significantly higher energy densities, making them ideal for use in remote, unmanned, or mobile platforms [4]. However, at reduced scales, combustion is challenged by rapid heat losses, limited residence time, and flame quenching effects, all consequences of elevated surface-to-volume ratios and confined geometries [5,6]. To address these limitations, vortex-induced swirl stabilization has emerged as a promising technique to enhance flame anchoring and combustion stability [7]. Swirl flows introduce a central recirculation zone (CRZ), which promotes fuel-air mixing, increases residence time, and recirculates hot combustion products toward the flame base, thereby enabling sustained combustion even under lean or transient conditions [8,9]. The effectiveness of swirl combustion is highly sensitive to the geometric configuration of the combustor, particularly the inlet diameters, chamber volume, flow behaviour, and degree of asymmetry, which collectively influence the strength [10], position, and symmetry of the vortex core [11,12].

This study directly addresses a meso-scale gap in how asymmetric geometry and volume scaling jointly modulate swirl intensity, Central Recirculation Zone (CRZ) coherence, wall heat transfer, and temperature fields across practical operating windows by contrasting two side-by-side combustors (Model A vs. Model B) over mass flow rates of inlet-air, = 40–170 mg s−1 and equivalence ratios, ϕ = 0.7–1.5. A problem space underexplored in prior micro/meso work is that it typically isolates swirlers or macro-devices rather than focusing on asymmetry scaling at the meso-scale. Methodologically, we solve the steady, 3-D Favre-averaged governing equations with a second-order upwind scheme, SIMPLE pressure velocity coupling, and the eddy-dissipation (ED) framework (chemistry treated volumetrically), with strict residual and temperature-monitor convergence criteria. In the grid independence test (six meshes), Scheme E (113,133 nodes) is selected as the optimal accuracy–cost trade-off (absolute error ≈ 2.6% at the right-most station), and differences versus finer meshes were ≤1.5% in key fields, evidence of numerical fidelity prior to production runs. Quantitatively, we report (i) strong divergence in swirl envelopes: Model A achieves S ≈ 6.5 at high /rich ϕ whereas Model B remains in a narrow S ≈ 1.2–1.6 band; (ii) consistent kinematic corroboration via tangential-velocity scaling (≈9 m s−1 for Model A vs. ≈3.2 m s−1 for Model B) that maps onto vortex-breakdown location and CRZ persistence; and (iii) the thermo-fluid linkage between breakdown, hot-product entrainment and wall loading, explaining broader but slightly cooler thermal cores in the larger-volume model (peak ≈ 2100–2140 K, below adiabatic due to wall losses and dilution). Collectively, these data reveal a clear design trade-off. Model A concentrates near-inlet heat-flux density but is more breakdown-prone at the highest . Model B trades peak intensity for coherence, uniformity, and wider stability margin, and they delimit an optimal operating window around ϕ ≈ 1.0–1.3 for stable, efficient output.

Recent numerical and experimental studies have investigated the role of inlet swirlers and flame–vortex interactions in macro- and mesoscale devices. Yet, there remains a gap in understanding how asymmetry and volume scaling influence vortex behavior, wall heat transfer, and emissions in meso-scale systems [13,14]. Furthermore, there is limited data correlating swirl strength and combustor performance under varying equivalence ratios and inlet mass flow conditions, parameters critical to achieving optimal combustion efficiency and reduced pollutant formation. In this study, we perform a detailed computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis of two asymmetric meso-scale vortex combustors operating over a wide range of air mass flow rates and equivalence ratios. The goal is to elucidate the relationships between combustor geometry, flow dynamics, and temperature distribution. The findings contribute to the rational design of next-generation micro-combustion systems with improved performance, thermal management, and environmental sustainability.

2. Numerical Method

2.1. Governing Equations

The three-dimensional, steady-state Favre-averaged governing equations for mass, momentum, species mass fraction, and energy in Cartesian coordinates are applied in this study [15]. These are given as follows:

where

is the density, u(i/j) is the velocity vector components, P is the pressure, λ is the thermal conductivity, Prt is the turbulent Prandtl number, Dn is the mass diffusivity of species (n) which was assumed to be constant for each species, Yn is the mass fraction of species (n), ωn is the chemical reaction rate,

is total enthalpy, μ is the dynamic viscosity, and μt is the turbulent viscosity. The ~ denotes the Favre averaging. Sct is the turbulence Schmidt number (Sct = μt/Dt, where Dt is a turbulence diffusivity). In the numerical procedure of this present study, various models of turbulence viscosity are examined.

2.2. Computational Approach

A second-order upwind scheme has been employed to discretize the flow domain using a three-dimensional (3D) finite volume solver that is grid-independent, and a variety of tetrahedral grids have been generated. In order to determine the mass conservation between the velocity terms and pressure in the discretized momentum equation, the SIMPLE algorithm has been implemented. The Eddy-Dissipation (ED) algorithm has been chosen for turbulence-chemistry interactions, and chemical reactions have been regarded as volumetric. Chemical kinetics (i.e., the Arrhenius rate) are disregarded by the ED reaction model, which exclusively employs the parameters specified in the reaction flow. The temperature and operating pressure were established at 300 K and 1.01 bar, respectively. The governing equations were solved using a steady-state pressure-based solver in all simulations using the CFD code ANSYS Fluent 14.0.

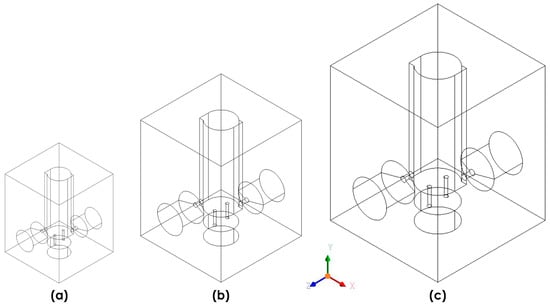

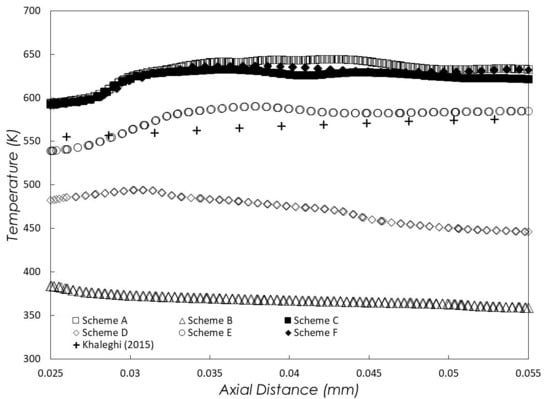

The solution is converged when the residuals of each governing equation at consecutive iterations are less than 1 × 10−4, with the exception of the species and energy equations, which are converged at quantities less than 1 × 10−6. When this condition was met, the flow field variables achieved stable local values with respect to any number of iterations. Additionally, the temperature parameter monitors converged independently. Reacting flow cases were subjected to this convergence criterion. Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the asymmetric vortex combustor design, while Table 1 provides the corresponding dimensions. A grid-independence study was conducted to quantify mesh-size effects; Scheme E provided the best accuracy, cost trade-off, and was therefore adopted for all cases to minimize computational time (Figure 3). This test was conducted with laminar flow and a counter-flow configuration, with inlet air and inlet fuel (methane) temperatures set at 300 K. Six (6) sets of meshes were generated using tetrahedral elements with SA = 649,207 nodes, SB = 337,918 nodes, SC = 222,096 nodes, SD = 151,567 nodes, SE = 113,133 nodes, and SF = 90,424 nodes. Results from the grid independence observations, Scheme E, which comprises 113,133 nodes, were determined to provide the optimal equilibrium between computational cost and accuracy among the evaluated schemes. Based on the rightmost axial station (x ≈ 0.055 mm) with T ≈ 570 K as reference, Scheme E predicts ≈ 585 K and an absolute error of ≈ 2.6%, the smallest among all schemes, and it is also close to the previous work from [16]. Hence, Scheme E is the preferred choice for validation and production runs, offering the best agreement with the benchmark while avoiding the systematic over-/under-prediction seen elsewhere. The differences in key flow parameters between Scheme E and finer meshes (Scheme A and Scheme B) were negligible, with variations in core temperature and velocity magnitudes remaining below 1.5%. This level of agreement validates the numerical fidelity of the mesh scheme and confirms its suitability for use in all subsequent simulations. All computational domains included both fluid and solid regions of the meso-scale combustor. A computer with a Core i9 CPU and 16 GB of RAM was used to perform these computations.

Figure 1.

Multi-scale meso combustor configurations: (a) Model X, d’FI = 1 mm, (b) Model A, d’FI = 1.5 mm, and (c) Model B, d’FI = 2.0 mm.

Figure 2.

Description of Meso-Combustor Model X, d’FI = 1.0 mm: (a) isometric view, (b) boundary conditions, (c) dimensions, and (d) meshing.

Table 1.

Dimensions of the meso-vortex combustor (all dimensions are in mm).

Figure 3.

Computational grid independence test [16].

3. Results

The evolution of Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) technology [1,2] has catalyzed growing interest in micro-combustion systems for portable power generation and propulsion, owing to their superior energy density relative to traditional energy storage devices. Despite their promise, these systems face inherent challenges associated with small-scale combustion, primarily due to reduced residence times and increased heat loss to combustor walls. These effects can severely limit combustion efficiency and may even result in flame quenching. Overcoming these limitations is essential to ensure reliable operation and sustain flame stability within meso-scale combustor architectures. As such, identifying and implementing effective stabilization strategies is a critical research priority. One proven approach to address these challenges is the introduction of swirl flow, which significantly enhances flame stabilization and combustion efficiency across various configurations. The intensity of the swirl, quantified by the swirl number, governs key combustion characteristics [17,18], including flame structure, anchoring, heat release distribution, and combustor geometry.

Swirl flow promotes a helical trajectory of the incoming reactants, facilitating enhanced mixing and localizing the reaction zone. Under strong swirl conditions, distinct axial and radial pressure gradients induce a Central Recirculation Zone (CRZ) [14,19], a flow structure absent in weak swirl regimes. The CRZ plays a pivotal role in flame stabilization by recirculating hot combustion products and generating a central low-velocity zone that inhibits flame blow-off and promotes compact flame anchoring. In this sub-topic, a series of computational simulations is conducted to systematically analyze the flow evolution and flame dynamics within a vortex-stabilized meso-combustor. Emphasis is placed on elucidating the formation and function of the CRZ under varying operational conditions.

3.1. Dynamic Mixing

3.1.1. Mixing Vortex in Combustion Chamber

Figure 4 illustrates the fuel (methane) at equivalence ratio, ϕ = 1.1, with air streamlines, respectively, and across varying air mass flow rates: (a) 40 mg/s, (b) 80 mg/s, (c) 120 mg/s, and (d) 170 mg/s. At lower flow rates (40–80 mg/s), the formation of a compact, centralized vortex core is evident, characterized by tightly coiled streamlines that enhance near-inlet mixing. This strong vortex structure facilitates rapid interaction between the fuel and oxidizer, promoting efficient premixing. As the air and fuel mass flow rates increase (120–170 mg/s), the streamlines elongate, and the vortex core shifts downstream. This displacement weakens the near-inlet recirculation and induces radial dispersion of the flow, indicating that the axial momentum begins to dominate over tangential confinement. Consequently, the core of the vortex becomes less effective in maintaining localized mixing, which can adversely impact combustion efficiency. Pathlines reveal that increasing

elongates streamlines and convects the vortex core downstream, weakening near-inlet recirculation while broadening the CRZ footprint. At higher

, secondary recirculation forms near the walls, and species accumulate off-axis, indicating reduced central mixing efficiency. Optimal mixing is observed at intermediate

, where axial and tangential momenta are balanced and CRZ coherence is maintained.

Figure 4.

Pathlines of (a) fuel and (b) air inlet at different fuel flow and mass flow rate at stoichiometric conditions.

At elevated fuel mass flow rates, the intensified axial momentum further displaces the vortex core downstream. It gives rise to secondary recirculation zones near the combustor walls. This shift results in fuel species accumulating along the outer radial regions rather than the core, thereby diminishing central mixing efficiency. The recirculation zone becomes broader and more elongated, reducing flame anchoring near the inlet and potentially increasing residence times in regions not conducive to optimal combustion. These observations are consistent with prior studies [8,20], which demonstrate that vortex behavior in such systems is highly sensitive to the ratio of axial to tangential momentum. In summary, increasing air and fuel mass flow rates lead to the downstream migration and expansion of the recirculation zone, altering vortex intensity and overall mixing quality. Optimal mixing occurs at intermediate flow conditions, where a balance between tangential and axial momentum prevents excessive vortex stretching or displacement. These findings underscore the importance of precisely tuning inlet geometry and mass flow conditions to sustain a strong, centralized recirculation zone, essential for achieving stable and efficient combustion in mesoscale vortex combustors.

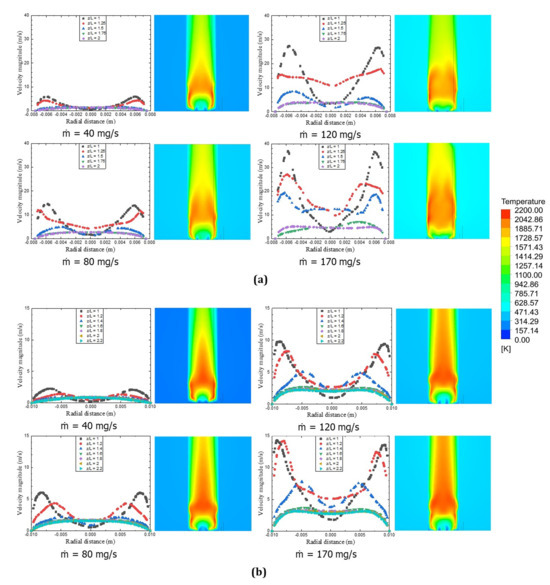

3.1.2. Flow Characteristics

Figure 5 presents the axial velocity magnitude profiles at five axial positions within the combustor for Model A and Model B, respectively. Both geometries display the canonical “low centerline–off-axis peak–near-wall decay” set by swirl-induced centrifugal displacement. With a larger inlet/volume (Model B), the pressure drop decreases and throughput rises. However, at the highest

, the flow exhibits stronger stratification and unsteadiness, characterized by enhanced thermal/velocity stratification, which is consistent with a shortened residence time and modified recirculation patterns. These trends clarify that the diameter causes

trade-off and show that stability margins narrow at the top end of

. The velocity distributions reveal a characteristic trend in both configurations: velocity magnitudes are lowest along the centerline, increase to a peak value beyond half the chamber radius, and then decline near the wall. This behavior arises from the outward displacement of flow due to centrifugal forces induced by the swirling motion. This pattern aligns well with the previous findings [6,20].

Figure 5.

Velocity magnitude profiles at various axial distances for (a) Model A, D = 1.5 mm and (b) Model B, D = 2.0 mm at an equivalence ratio of 1.0, under different inlet air mass flow rates of 40 mg/s, 80 mg/s, 120 mg/s, and 170 mg/s.

Furthermore, this section presents a comparative analysis of temperature distributions in a meso-scale combustor for two fuel inlet diameters, namely 1.5 mm and 2.0 mm, under varying fuel mass flow rates ranging from 40 mg/s to 170 mg/s. The investigation was carried out through numerical simulations, with results illustrated via transverse temperature profiles at multiple axial locations (z/L = 1.0–2.2) and corresponding temperature contour plots. The observed trends provide insights into the influence of inlet geometry and mass flux on combustion characteristics, with implications for thermal efficiency, flame stability, and heat transfer behavior. At increasing

, axial momentum rises, convecting the vortex-breakdown station downstream and shortening the flow time scale (lower Da); stability therefore hinges on CRZ coherence. Model B’s larger-volume configuration and inlet sizing sustain a centrally anchored, axially aligned vortex (lower peak

, narrower S-range), yielding longer effective residence time and smoother temperature fields as Pe increases. Model A intensifies swirl and shear at high

, enhancing near-inlet mixing at low–moderate

, but becoming breakdown-prone and wall-loaded at the highest

. This trade-off explains Model B’s robustness at high

and the observed ϕ trends. For the 1.5 mm fuel inlet, at the lowest flow rate ( = 40 mg/s), the combustion zone is confined near the inlet region, forming a short, centrally concentrated flame with limited radial spread. The temperature contours and cross-sectional profiles reveal a diffusion-dominated regime, where insufficient convective momentum hinders effective mixing and thermal penetration toward the combustor walls. As a result, wall heat flux remains minimal, and combustion energy is largely localized within the flame core. This behavior is characteristic of low Reynolds number flow conditions with reduced turbulent activity [20,21] contributing to incomplete heat release and reduced flame-wall interaction.

As the mass flow rate increases to 85 mg/s and 130 mg/s, the flame becomes progressively more developed, with significant axial elongation and radial expansion. The transverse temperature profiles at z/L = 1.25–1.5 indicate elevated wall temperatures and a more uniform thermal envelope. This improvement is attributed to the formation of coherent vortex recirculation zones and intensified shear at the fuel–air interface, enhancing both momentum and scalar mixing. In this range, the combustion transitions into a convective-dominated regime, resulting in improved heat transfer to the combustor walls and a more stable flame structure. These conditions are favorable for optimized combustor performance in terms of energy recovery and temperature uniformity. However, at the highest flow rate of 170 mg/s, the flame exhibits over-penetration, as evidenced by the elongated temperature contours and declining thermal intensity in downstream regions (z/L > 1.75). The cross-sectional profiles show elevated temperatures at near-wall regions, particularly at early axial positions, followed by a sharp drop beyond z/L = 2. This trend suggests the onset of flame quenching and thermal stratification, likely due to excessive inertial forces causing the flame core to detach from optimal reaction zones. Shortened residence time, combined with turbulent dispersion, reduces the effective mixing duration, resulting in incomplete combustion and localized thermal inefficiencies.

In comparison, the combustor performance with a 2.0 mm fuel inlet diameter shows similar progression across the range, but with distinct variations arising from the increased flow area. At 40 mg/s, the flame remains short and poorly mixed, with lower peak temperatures compared to the 1.5 mm case. Despite the larger orifice, the lower injection velocity limits momentum-driven transport and vortex generation, sustaining a diffusion-limited regime with weak convective interaction. At 85 mg/s and 130 mg/s, the 2.0 mm inlet achieves broader flame coverage, with improved radial spreading and higher wall temperature profiles, especially at mid-length sections (z/L = 1.4–1.6). This suggests an enhanced flame–wall interaction due to increased entrainment and flow development [22].

The increased hydraulic diameter promotes lower pressure drop, allowing higher throughput without compromising stability, though it requires careful tuning of mass flux to avoid overexpansion. At 170 mg/s, however, the flame structure exhibits stronger stratification and unsteadiness, with pronounced thermal stratification and abrupt downstream temperature decay. The high fuel momentum leads to irregular recirculation behavior, reduced anchoring strength, and incomplete combustion due to insufficient residence time. These effects are amplified compared to the 1.5 mm case, indicating that the stability margin is narrower for larger inlets at elevated levels.

From a transport phenomenon standpoint, increasing the inlet diameter alters the balance between convective transport, diffusive mixing, and reaction time scales. While larger diameters allow for higher throughput, they also pose challenges related to residence time reduction, flame detachment, and localized quenching. The interaction between Reynolds number, Peclet number, and swirl intensity becomes critical in maintaining flame stability and thermal uniformity, especially at high loading conditions. Overall, the results confirm that the optimal operating window for both geometries lies within the 85–130 mg/s range, where favorable momentum and turbulence levels promote efficient mixing, uniform heat distribution, and stable flame anchoring. The 1.5 mm inlet provides better upstream thermal localization and flame control. In comparison, the 2.0 mm inlet enables broader flame expansion but requires careful optimization to mitigate instabilities at higher flow rates. These findings highlight the importance of tuning fuel delivery parameters and combustor geometry in achieving thermally efficient and robust meso-combustor designs [4].

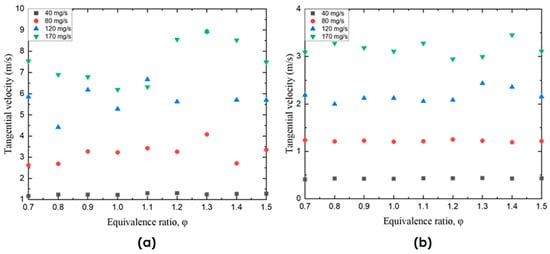

Figure 6 illustrates the variation in tangential velocity across different equivalence ratios and mass flow rates for both models. Model A exhibits a steep increase in

with

(peaking at the highest loading) and moderate enrichment sensitivity up to ϕ ≈ 1.3–1.4, reflecting centrifugal intensification under heavy momentum input. Model B maintains consistently lower

and flatter radial profiles, indicating geometric/hydraulic suppression of swirl amplification. The contrast demonstrates how geometry tunes swirl intensity and, in turn, CRZ behavior and wall-heat-flux exposure. This behavior suggests that centrifugal forces associated with higher flow rates play a dominant role in vortex intensification, while the equivalence ratio exerts a secondary influence, likely through changes in flame anchoring and density stratification at richer mixtures.

Figure 6.

Variation in tangential velocity with respect to mass flow rate of inlet air (40, 80, 120, and 170 mg/s) for (a) Model A, D = 1.5 mm and (b) Model B, D = 2.0 mm.

This disparity is attributed to geometric or flow resistance constraints that inhibit swirl development. Both models show limited sensitivity to equivalence ratio at low flow rates but exhibit modest increases at higher flow conditions, underscoring the complex interplay between flow dynamics and mixture composition. These results align with recent studies by [13], which emphasize the critical role of combustor geometry and flow conditions in governing swirl development and vortex breakdown. Collectively, the lower

and flatter radial profiles in Model B support CRZ coherence as

increases, which is critical to avoiding downstream flame thinning and wall-biased losses.

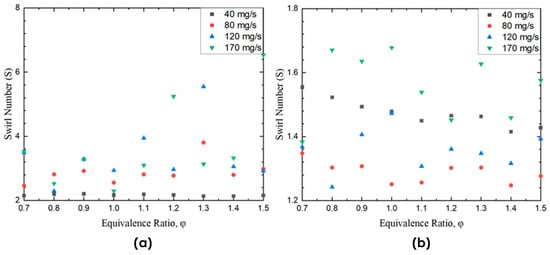

3.1.3. Swirl Number

In micro/meso combustors, swirling flows provide a straightforward and efficient method of flame stabilization. In order to create a strong unfavourable pressure gradient that causes a flow reversal and establishes a core recirculation zone, the meso-scale combustor’s input air is totally tangential. The integration of the swirl number (S) [23], as defined in Equation (5), was calculated along the chamber depth across various equivalence ratios and mass flow rates, as illustrated in Figure 7, and offers a more comprehensive insight into the differences in vortex characteristics [18,24]. Figure 7 shows the swirl number, S, versus

and ϕ (Models A and B). In Model A, S escalates markedly beyond

in the upper-mid range and for ϕ > 1.1, signaling strong coupling between momentum input and vortex strength; this raises the risk of shear-layer corrugation, core drift, and early breakdown. Model B remains narrowly distributed (moderate S) across the tested

–ϕ window, denoting swirl insensitivity to enrichment and supporting a centered, coherent CRZ under high

.

where

is the density,

is the axial velocity component (m/s),

is the tangential (swirl) velocity component (m/s),

is the radial coordinate (m),

is the differential area element over the cross-sectional area

,

is the diameter of the combustor or pipe (m), and

is the cross-sectional area of the flow.

Figure 7.

Variation in swirl number with respect to inlet air mass flow rates of 40, 80, 120, and 170 mg/s for (a) Model A, D = 1.5 mm and (b) Model B, D = 2.0 mm.

For interpretation, we refer to the Damköhler number Da = τflow/τchem and the Peclet number Pe = UL/α to characterize, respectively, reaction-to-flow time-scale ratios and advection-dominated transport; the swirl number S is defined in Equation (5). Increases in

raise U (higher Pe, lower Da); hence, stability at high

requires a coherent CRZ rather than merely higher global node counts.

In Model A, the swirl number increases significantly with mass flow rate, especially beyond 120 mg/s. A sharp rise is evident at equivalence ratios greater than ϕ = 1.1, culminating in a peak swirl number of approximately 6.5 at ϕ = 1.5 under the highest flow rate. This trend indicates a strong coupling between flow rate and vortex strength, with richer mixtures contributing to intensified centrifugal and shear forces. At lower mass flow rates (40–80 mg/s), however, the swirl number remains relatively constant, suggesting that the influence of the equivalence ratio on vortex behavior is minimal under low-flow conditions. In contrast, Model B exhibits a markedly different pattern. Across all tested conditions, the swirl number remains relatively stable, ranging narrowly between 1.2 and 1.6. Even at the highest mass flow rate (170 mg/s), variations in equivalence ratio produce only marginal changes in swirl number. This stability reflects an inherent insensitivity to mixture richness, likely due to the geometric or hydraulic design features of Model B that limit vortex amplification.

Such behavior indicates a more uniform and stable flow regime, albeit at the expense of strong recirculation. These findings are consistent with the work of [10], emphasizing the influence of combustor architecture on swirl development. In summary, Model A promotes vortex intensification under high flow and rich mixture conditions, whereas Model B maintains consistent, weaker swirl dynamics across the entire operating envelope. This contrast highlights the critical role of combustor design in tailoring vortex strength for optimized combustion stability and mixing performance. Accordingly, B’s narrow S band (~1.2–1.6) maintains an on-axis vortex and limits shear-layer corrugation, preserving a centered CRZ at high

.

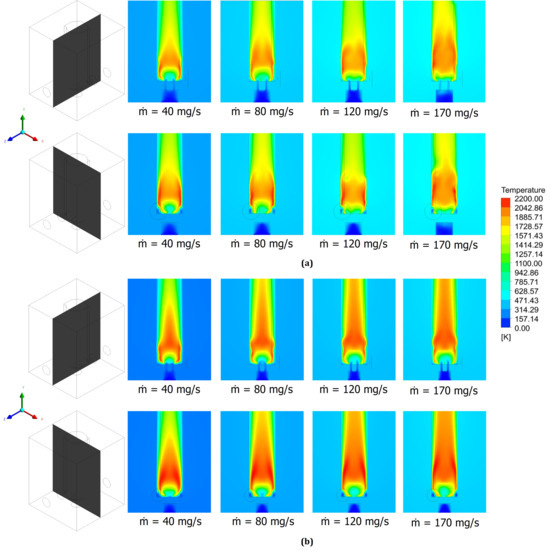

3.2. Combustion Temperatures

3.2.1. Temperature Pattern for Natural Gas with Air

Understanding the temperature distribution within vortex-stabilized combustors is critical for elucidating the aerodynamic mechanisms that underpin flame stability [22]. Figure 8 presents two-dimensional temperature contours for a stoichiometric natural gas–air mixture under atmospheric conditions at varying inlet air mass flow rates (40–170 mg/s). As

increases, the high-temperature core elongates and spreads radially downstream, especially in the larger-volume Model B, which distributes heat over a wider cross-section. Model A shows stronger near-inlet intensity at low–moderate

but greater susceptibility to downstream stratification at the highest

. The comparison clarifies a design trade-off between peak heat-flux density (A) and downstream uniformity/robustness (B).

Figure 8.

Temperature contours of the reacting flow within the vortex combustor are presented for different inlet air mass flow rates: (a) Model A, d’FI = 1.5 mm and (b) Model B, d’FI = 2 mm.

This effect is evident in both Model A and Model B, but it is particularly pronounced in the larger-volume combustor (Model B), where greater inlet momentum and stronger swirling motion enhance the radial spreading of the thermal core. In Model A, thermal asymmetry becomes evident beyond 80 mg/s, with the flame tilting toward the asymmetric side. This phenomenon indicates intensified vortex breakdown and increased entrainment of cooler surrounding gases, which reduces thermal uniformity downstream. The expansion of the hot core is accompanied by a peak temperature rise to a flow rate of 120 mg/s. However, at 170 mg/s, a slight decline in peak temperature is observed, likely due to reduced residence time and incomplete combustion at high velocities. Peak temperatures consistently appear near the flame front and shift upstream with increasing flow rates, indicating flame anchoring closer to the nozzle exit as axial momentum increases.

Despite achieving localized peak temperatures between 2100 K and 2140 K in Model A, and slightly lower (~2100 K–2103 K) in Model B, these values remain below the theoretical adiabatic flame temperature (~2200 K). The discrepancy is attributed to wall heat losses and dilution effects from entrained air. The broader radial and axial spread of the hot flow region with increasing mass flow rate is more prominent in Model B, a result of intensified centrifugal forces that promote wider flame distribution and reinforce the central recirculation zone (CRZ) [14]. Consequently, the flame structure transitions from a compact to a broader and flatter shape, signifying improved flame stability at higher flow rates due to enhanced recirculatory flow. Nevertheless, the slightly lower peak temperatures in Model B highlight the trade-off between expanded flame spread and increased thermal losses owing to its larger surface area.

Consistent with the velocity/swirl trends, Model B distributes heat more uniformly downstream at high

reflecting a coherent CRZ and axially aligned core; Model A, while intense near the inlet at low–moderate

shows stronger stratification and earlier decay at the highest

due to shear-induced core fragmentation and wall loading. This uniformity underpins B’s higher completeness at high Pe despite slightly lower peak temperatures.

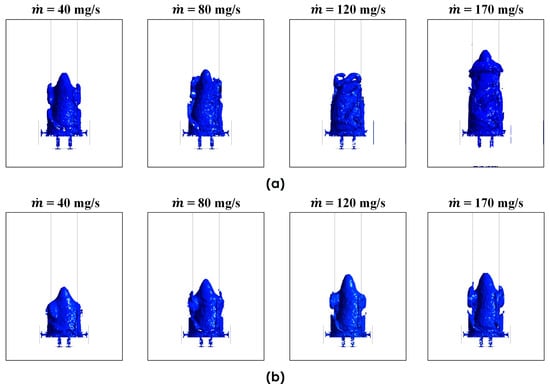

3.2.2. Vortex Structure

Figure 9 shows that swirling-strength iso-contours with varying

(Models A and B). Swirling-strength ridges co-locate with a near-zero static-pressure well, evidencing a swirl-induced mechanism that sustains the CRZ and hot-product entrainment to the flame base. With increasing

, the breakdown station shifts downstream and the core–shear interface corrugates; geometry dictates whether this intensification yields coherence or fragmentation. Model A develops secondary vortices and lateral core drift at the highest

, whereas Model B preserves an axially aligned, centered vortex with smoother temperature fields and a wider stability margin.

Figure 9.

Iso-contours of swirling strength at various inlet air mass flow rates: (a) Model A, d’FI = 1.5 mm and (b) Model B, d’FI = 2.0 mm.

As the inlet air mass flow increases from 40 to 170 mg s−1, axial momentum strengthens, the vortex-breakdown station convects downstream, and the core–shear interface becomes more corrugated, signatures of amplified Kelvin–Helmholtz activity and turbulence production, yet a discernible CRZ persists. Geometry governs whether this intensification yields coherence or fragmentation: the compact chamber (Model A; d’FI = 1.5 mm) produces high local velocities (≈40 m s−1) and steep radial gradients that accelerate near-inlet mixing and promote strong heat release at low–moderate

, but at the highest

it develops secondary vortices and lateral core drift, indicating reduced symmetry, earlier breakdown susceptibility, and sharper wall-normal thermal gradients.

In contrast, the larger chamber (Model B; d’FI = 2.0 mm) maintains a centrally anchored, axially aligned vortex (peaks ≈ 15 m s−1) with flatter radial profiles, suppressing secondary structures and yielding smoother temperature fields and a wider stability margin. Critically, these observations expose a design trade-off: Model A concentrates heat-flux density but is more breakdown-prone under high momentum, whereas Model B trades peak intensity for coherent entrainment and uniform downstream heating. Hence, for subsonic operation (M < 0.3), selecting combustor volume and inlet sizing is the primary lever to balance mixing-driven gains against residence-time penalties and to position breakdown where it benefits flame anchoring rather than destabilizing it.

4. Conclusions

This study conducted a detailed computational investigation of two asymmetric meso-scale vortex combustor designs to evaluate the effects of geometry, air mass flow rate, and equivalence ratio on combustion performance, vortex dynamics, temperature fields, and emissions characteristics. The results demonstrate that combustor geometry plays a critical role in determining flame stability, mixing efficiency, and thermal behavior. Model B, with a larger chamber volume and wider inlets, consistently exhibited superior performance across all evaluated metrics. It maintained a more symmetrical and stable recirculation zone, promoted more complete combustion, and exhibited higher total energy output. Additionally, it showed reduced wall temperature gradients and lower NOx emissions under high flow rate conditions. In contrast, Model A, with its more compact configuration, experienced greater flame asymmetry, intensified wall heat flux, and limited combustion completeness at elevated flow conditions, primarily due to reduced residence time and vortex displacement. Nonetheless, it performed efficiently under low to moderate flow rates, where the balance between axial and tangential momentum favored strong near-inlet recirculation. Across both models, the optimal operating window was observed near stoichiometric to moderately rich mixtures (ϕ ≈ 1.0–1.3), which yielded peak flame temperatures and energy output. These findings confirm the importance of carefully tuning both geometric parameters and operating conditions to sustain strong vortex structures, achieve efficient energy conversion, and minimize emissions in compact combustion systems. The insights from this work provide a robust foundation for the advancement of thermally efficient, low-emission meso-scale combustors suitable for integration into portable thermoelectric generators and autonomous micro-power.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.A.L. and C.Y.K.; methodology, M.L.A.L.; software, M.A.R.A.; formal analysis, M.A.-H.M.N.; investigation, M.F.K.; resources, H.J.J.; data curation, M.A.-H.M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.-H.M.N. and M.A.R.A.; writing—review and editing, C.Y.K.; visualization, A.H.R.; supervision, M.A.-H.M.N.; project administration, A.S.A.S. and M.A.J.; funding acquisition, A.H.R. and M.S.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding. As there was no external funding, there was no funder involvement in the design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation for all the support received from the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Technology, Universiti Malaysia Perlis (UniMAP).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Wang, F.; Li, X.; Feng, S.; Yan, Y. Influence of Porous Media Aperture Arrangement on CH4/Air Combustion Characteristics in Micro Combustor. Processes 2021, 9, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelburg, L.M.; Ghaderi, M.; Bilby, D.; Visser, J.H.; Zhang, G.Q.; Lundgren, P.; Enoksson, P.; Wolffenbuttel, R.F. Maintaining Transparency of a Heated MEMS Membrane for Enabling Long-Term Optical Measurements on Soot-Containing Exhaust Gas. Sensors 2020, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, A.H.; Ballal, D.R. Gas Turbine Combustion: Alternative Fuels and Emissions, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbari, A.; Homayoonfar, S.; Valizadeh, E.; Aligoodarz, M.R.; Toghraie, D. Effects of micro-combustor geometry and size on the heat transfer and combustion characteristics of premixed hydrogen/air flames. Energy 2020, 215, 119061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuttaRoy, R.; Chakravarthy, S.R.; Sen, A.K. Experimental investigation of flame propagation and stabilization in a meso-combustor with sudden expansion. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2018, 90, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones, A.M.; Burrus, D.L.; Erdmann, T.J.; Shouse, D.T. Effect of centrifugal force on the performance of high-g ultra compact combustor. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2015: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, Montreal, QC, USA, 15–19 June 2015; Volume 4B, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Yu, J.; Chen, W.; Hao, C.; Zhang, J.; Fu, G.; Sun, B. Experimental Study on Combustion Characteristics of Methane Vertical Jet Flame. Processes 2025, 13, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S.; Wang, H.; Jin, T.; Tao, W.; Wang, G. Isothermal swirling flow characteristics and pressure drop analysis of a novel double swirl burner. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 035240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifzadeh, R.; Afshari, A. Large eddy simulation of swirling flows in a non-reacting trapped-vortex combustor. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 127, 107711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pátý, M.; Valášek, M.; Resta, E.; Marsilio, R.; Ferlauto, M. Passive Control of Vortices in the Wake of a Bluff Body. Fluids 2024, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehole, H.A.H.; Mehdi, G.; Riaz, R.; Maqsood, A. Investigation of Sustainable Combustion Processes of the Industrial Gas Turbine Injector. Processes 2025, 13, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wang, D.; Xu, J.; Meng, H. Computational Study of the Effect of Dual Air Swirling Injection on Turbulent Combustion of Kerosene–Air at a High Pressure. Eng. Proc. 2023, 56, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Pan, J.; Zhu, Y. Effects of the swirler on the performance of an advanced vortex combustor. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 230, 120752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Peng, W.; Yu, X.; Shi, B. A comparison of partially premixed methane/air combustion in confined vane-swirl and jet-swirl combustors. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2023, 195, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obieglo, A.; Gass, J.; Poulikakos, D. Comparative study of modeling a hydrogen nonpremixed turbulent flame. Combust. Flame 2000, 122, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, M.; Hosseini, S.E.; Wahid, M.A. Vortex combustion and heat transfer in meso-scale with thermal recuperation. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 66, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.L.A.; Nawi, M.A.-H.M.; Alias, M.A.R.; Khor, C.Y.; Kamarudin, M.F.; Roslan, A.H.; Jaafar, H.J. Numerical Elucidation on the Dynamic Behaviour of Non-Premixed Flame in Meso-Scale Combustors. Modelling 2025, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, M.F.; Nawi, M.A.-H.M.; Roslan, A.H.; Latif, M.L.A.; Jaafar, H.J.; Hanid, M.H.M.; Danish, M. Effects of Heat Transfer on Combustion Characteristics in a Cylindrical Vortex Combustor. J. Adv. Res. Numer. Heat Trans. 2024, 27, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasch, S.; Swaminathan, N.; Spijker, C.; Ertesvåg, I.S. A Numerical Study of Flow Structures and Flame Shape Transition in Swirl-Stabilized Turbulent Premixed Flames Subject to Local Extinction. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2023, 197, 338–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Jin, Y.; Yao, K.; Wang, Y.; Lian, W. Effects of swirling motion on the cavity flow field and combustion performance. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 138, 108275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Lin, H.; Yu, J.; Song, A.; Guo, Q.; Wen, Z.; Wu, W. Study on Influence of Evaporation Tube Flow Distribution on Combustion Characteristics of Micro Combustion Chamber. Processes 2025, 13, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Tian, X.; Xu, L.; Xia, X.; Qi, F. Experimental Investigation of Pure Hydrogen Flame in a Matrix Micro-Mixing Combustor. Aerospace 2025, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignat, G.; Durox, D.; Candel, S. The suitability of different swirl number definitions for describing swirl flows: Accurate, common and (over-) simplified formulations. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2022, 89, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreres, M.; García-Tíscar, J.; Belmar-Gil, M.; Cervelló-Sanz, D. Influence of key geometrical features on the non-reacting flow of a Lean Direct Injection (LDI) combustor through Large-Eddy Simulation and a Design of Experiments. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 126, 107634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).