Abstract

The cement industry significantly contributes to global CO2 emissions, making material efficiency in concrete structures a crucial sustainability goal. This study addresses the challenge of excessive cement usage in traditional concrete design by optimizing a cast-in-place concrete bench. A density-based topology optimization framework was implemented in ANSYS Mechanical and enhanced with a deep-learning surrogate model to accelerate computational performance. The optimization aimed to minimize the structural mass while satisfying serviceability and strength constraints, including limits on displacement and compressive stress under realistic public-use loading conditions. The topology optimization converged after 62 iterations, achieving a 46% reduction in mass (from 258.3 kg to 139.4 kg) while maintaining a maximum deflection below 2 mm and a maximum compressive stress of 15.5 MPa, within the allowable limit for C20/25 concrete. The deep-learning surrogate model achieved strong predictive accuracy (IoU = 0.75, Dice = 0.73) and reduced computation time by over 105× compared to the full finite element optimization. The optimized geometry was reconstructed and rendered using Blender for visualization. These results highlight the potential of combining topology optimization and machine learning to reduce material use, enhance structural efficiency, and support sustainable practices in concrete construction.

1. Introduction

The global cement industry is the world’s third-largest anthropogenic emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions [1], accounting for approximately 5% of human emissions [2] and 8% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions [3]. In addition to the fuel used to power cement production, the chemical process intrinsic to the production process contributes significantly to the overall emissions produced. The combustion of the raw cement material limestone results in a chemical reduction from calcium oxide to calcium carbonate, during which CO2 is released [4].

It is essential to determine the optimum topology or structure according to some design objectives and constraints for new product development, particularly at the early phase of the design process, i.e., the conceptual and project definition phase. Correspondingly, in the past decade, immense efforts in basic research have been directed toward creating efficient and trustworthy systems [5]. Structure topology optimization (TO) is a field that is quickly developing and is of particular interest to the aerospace and automotive sectors. Topology optimization, as opposed to shape optimization, permits the creation of voids or recesses in structures, typically leading to spectacular reductions in weight or enhancements in structural performance measures such as stiffness, strength, or dynamic response [6].

Topology optimization is the method by which void connectivity, topology, and placement are determined within a specified design domain. Topology optimization provides significantly more design flexibility than sizing and shape optimization, which seek to optimize design parameters such as thicknesses or cross-sectional areas of structural members (sizing) and the geometry parameters (shape) of specified structural configurations. Thus, topology optimization is highly valuable during the early conceptual and preliminary design stages, where design modifications can drastically influence the performance of the final structure. The general mathematical formulation of a density-based topology optimization problem consists of an objective function, a system of constraints—likely containing a maximum material consumption limit—and a discretized model of the physical system. A general formulation derived from linear static finite element analysis [7].

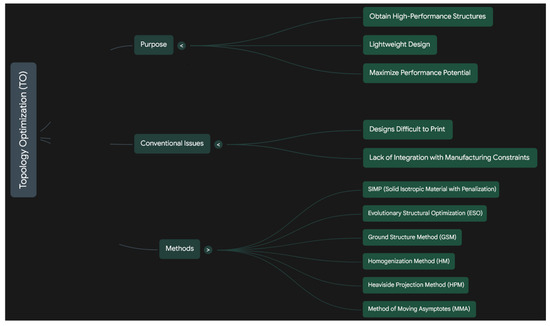

Topology optimization is widely recognized as an advanced design technique for attaining high-performance structural solutions. It is used as a freeform engineering design tool that automatically develops optimal geometries by placing material in critical areas and removing it from less loaded areas within a predefined design space (see Figure 1). This method often leads to novel design options that typically outperform conventional lightweight designs. While TO has been effectively applied in lightweight designs in various areas of engineering, such as automotive and aerospace, its application in concrete structures is particularly attractive considering the initial liquid stage of concrete, which makes it highly formable and inexpensive and high strength, making it a ubiquitous building material [8,9]. The resulting load-adaptive character of TO structures, analogous to those of natural systems such as bones, has significant potential for material efficiency and sustainable construction [10].

Figure 1.

Overview of topology optimization: Purposes, conventional issues, and common methods.

Optimization Problem:

subject to:

where

- : Vector of density design variables (values between 0 and 1 represent the material distribution).

- : Displacement vector—nodal displacement of the structure.

- : Stiffness matrix, which depends on the density variables.

- : Force (load) vector, which may also depend on the density variables.

Product development and manufacturing, particularly in industrial uses, create a question regarding the resulting actions that must be taken to carry out quality and reliability enhancement successfully without incurring more than specified cost constraints. A new field has appeared in computer-aided engineering called structural optimization, with the objective of structure optimization. It offers to the development, calculation, and design departments a tool that, via mathematical algorithms, allows us to obtain better, perhaps optimal, designs as far as admissible structural responses, deformations, stresses, eigenfrequencies, etc., manufacturing, and interaction of all structural components are concerned. Thus, structural optimization has become a multidisciplinary field of research [11,12,13,14].

Within topology optimization, which is the field of interest in the present study, compliant materials can be defined in terms of voids, which considerably simplifies the formulations linked to the optimum characteristics of microstructures and hence facilitates the description of such optimum features within a compact analytical framework [15]. Beyond its direct applicability to cast-in-place members, as exemplified by the concrete bench subject to analysis herein, topology optimization is identified as an indispensable component in many other vital aspects of concrete construction. Its application has been markedly substantiated in the field of reinforced concrete (RC) design, specifically the formulation of strut-and-tie models (STMs) developed for complex D-regions, which provide the means to describe force transfer paths and reinforcement requirements. Researchers have utilized topology optimization for the optimization of concrete and reinforcing steel elements with the aim of enhancing damage resistance or attaining weight savings in posttensioned RC members. This reinforces the flexibility of topology optimization in addressing the distinctive challenges and opportunities inherent in different concrete applications [9].

Recent studies further highlight the integration of machine learning with structural engineering applications. Duan et al. demonstrated how finite element analysis (FEA) generates substantial amounts of numerical and image data, which can be processed by machine learning algorithms to assess the spatial–temporal conditions of reinforced concrete beams under flexural loading [16]. Similarly, Lazaridis and Thomoglou (2024) proposed a data-driven methodology for masonry structures, noting that “the most effective models were the optimized instances of XGBoost and CatBoost methods, which combined into a voting model to leverage the predictive capacity of more than a single regressor” [17]. These contributions illustrate the growing role of interpretable and efficient ML frameworks in predicting structural performance, ranging from reinforced concrete beams to TRM-strengthened masonry walls. In parallel, carbon footprint analyses of concrete highlight cement production as the dominant source of greenhouse gas emissions, while the incorporation of waste materials such as rubber powder and recycled wire has been shown to substantially reduce embodied emissions [18]. Together, these advances reinforce the relevance of ML-assisted optimization in sustainable construction research, linking predictive performance with environmental impact reduction.

This research investigates the optimization of concrete bench design aimed at minimizing material usage during construction, which is consistent with the principles of sustainable development, while striving to decrease cement consumption without jeopardizing structural integrity. Concrete is a heterogeneous material characterized by multiple scales that has varied responses to both tensile and compressive forces. In contrast to metals, concrete exhibits significant nonlinear behavior, which is evident through phenomena such as cracking, creep, shrinkage, tension softening, and compression softening. The present study adopts a linear elastic material model in conjunction with the von Mises stress criterion for the sake of simplicity during the preliminary optimization phase; however, it is critical to acknowledge that this criterion presumes equal strength thresholds under both tension and compression. Given that concrete behaves asymmetrically within these two domains, the Drucker–Prager yield criterion is generally favored, as it accommodates separate strength limits for tensile and compressive conditions. Recent progress in the field of topology optimization for concrete has frequently integrated elastoplastic material models along with reinforcing steel, commonly employing Drucker–Prager plasticity to more accurately capture the nonlinear characteristics of the material’s response. Consequently, the employment of a linear elastic model in this foundational study serves as a conscious simplification, with the anticipation that forthcoming research will adopt more sophisticated nonlinear material representations.

While density-based topology optimization successfully optimizes for the minimum mass with the required stiffness, each finite element simulation is computationally expensive such that it is currently impractical for iteration in design or parametric studies. To overcome this limitation, this work combines a deep learning-based surrogate model for the first time with traditional finite element topology optimization. The surrogate model estimates optimized density fields directly from boundary conditions and load configurations by several orders of magnitude, decreasing the computation time. The aims are (i) designing a machine-learning surrogate for topology optimization, (ii) assessing its predictive accuracy and computational efficiency, and (iii) illustrating its potential for sustainability-oriented concrete design. Recent research, such as that of Shin et al. [19] and Sosnovik & Oseledets [20], has shown the potential of data-driven models for the purpose of topology optimization, and this work is motivated by these data-driven models.

2. Problem Statement

The current research aims to reduce the self-weight of a cast-in situ concrete bench without sacrificing both structural stiffness and functionality. By reducing the amount of cementitious materials used, this design consequently addresses the high carbon dioxide emissions from the cement industry while following modern sustainable guidelines regarding material efficiency. The optimization goal is mass minimization within the strength and displacement performance constraints, hence ensuring that the bench complies with typical load demands for public use while significantly reducing the amount of concrete used.

2.1. Design Domain

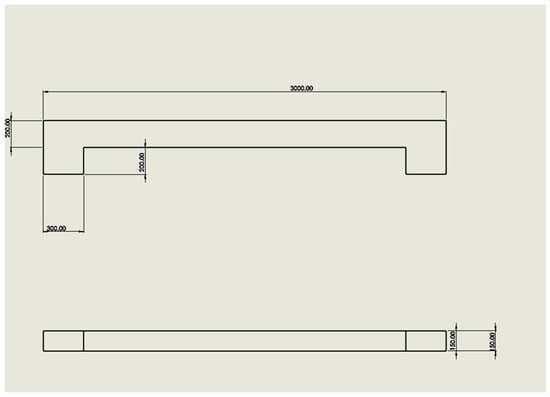

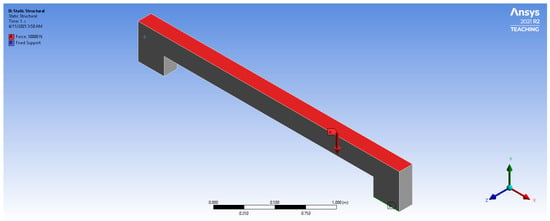

The bench has overall dimensions of 3000 mm in length, 150 mm in width, and 400 mm in height, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The material used in this model was C20/25 concrete, and the mechanical properties of the material are listed in Table 1. The material properties for C20/25 concrete were taken from 2021 ANSYS Granta Material Data for Simulation [21].

Figure 2.

Initial design domain of the concrete bench with key dimensions.

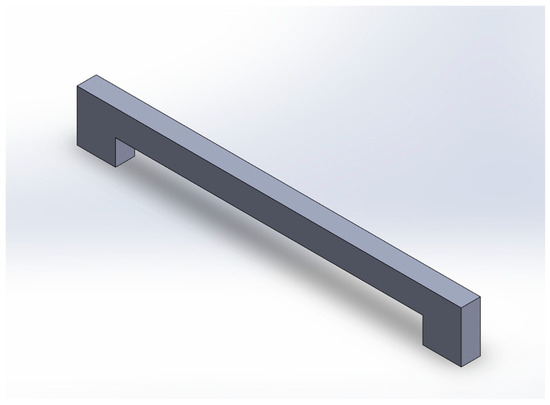

Figure 3.

Isometric view of the initial concrete bench design.

Table 1.

Material properties of the concrete used in the optimization on this study.

2.2. Boundary Conditions and Loading

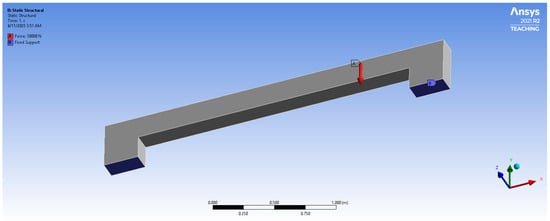

The bench was restrained at two support regions located on the underside of the structure, as shown in Figure 4. These regions were modeled using fixed support, preventing translation and rotation in all degrees of freedom. To represent the load from users sitting on the bench, a distributed vertical load of 30 kN was applied uniformly along the top surface across the full 3000 mm length of the bench as shown in Figure 5. This loading condition simulates the realistic service load acting on the bench during use.

Figure 4.

Load application and fixed support location (side view).

Figure 5.

Load application and fixed support location (top view).

2.3. Meshing

The geometry was meshed using hexahedral elements with an element size of 0.03 m with number of nodes equal to 16,286 and 3150 elements to balance computational efficiency and geometric accuracy during the topology optimization.

2.4. Topology Optimization Setup

Topology optimization is performed using the SIMP density-based method, with a penalization factor of 3.0 to enforce a clear distinction between solid and void regions. The optimization objective is to minimize mass, while satisfying both structural performance constraints and manufacturability constraints, listed as follows:

Structural Performance Constraints:

- Maximum vertical displacement ≤ 2 mm.

- Maximum equivalent (von Mises) stress ≤ 10 MPa.

Manufacturability Constraints:

- Minimum feature size controlled by a 20 mm filter radius.

- Symmetry constraints applied along the global Y- and Z-axes to maintain geometric balance and facilitate fabrication.

This setup ensures that the optimized bench remains structurally efficient, manufacturable, and visually symmetric.

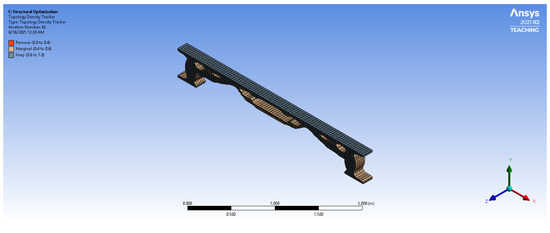

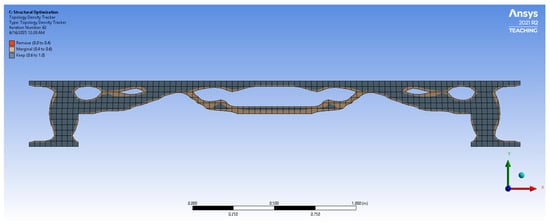

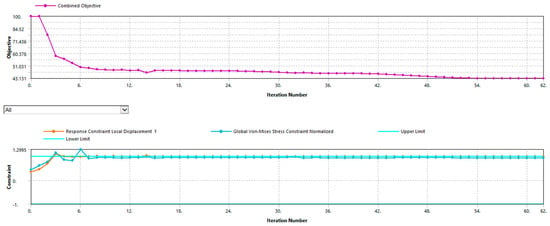

2.5. Optimization Results

The resulting material distribution and optimized geometry are illustrated in Figure 6 and Figure 7. A comparison between the original and optimized designs in terms of mass and volume is presented in Table 2. The topology optimization converged after 62 iterations, as shown in Figure 8. The solution satisfied all imposed constraints on displacement, stress, and minimum feature size. The final optimized design resulted in a bench mass of 139.36 kg, reduced from the original 258.3 kg.

Figure 6.

Optimized bench design showing the material distribution (isometric view).

Figure 7.

Optimized bench design showing the material distribution (front view).

Table 2.

Comparison of mass and volume.

Figure 8.

Convergence plot.

2.6. Validation and FEA

Before conducting the final stress analysis, the optimized density field obtained from the topology optimization was not used directly in the finite element simulation. The optimization output is a voxel-based density layout, which does not form a clean or manufacturable solid body. Therefore, the optimized geometry was remodeled to create a smooth solid representation that preserves the primary load paths identified during optimization. It is important to note that this remodeling process can slightly alter the local stiffness distribution, and therefore the stresses in the remodeled model are generally higher than those reported in the raw topology optimization stage. For this reason, a 10 MPa stress constraint was intentionally used during optimization—significantly below the material’s compressive strength of 20 MPa—to ensure that once the geometry was remodeled and remeshed, the final stresses would remain within safe limits.

This explains why the optimization stage used a 10 MPa stress limit, while the remodeled geometry exhibits a higher final stress of 15.5 MPa.

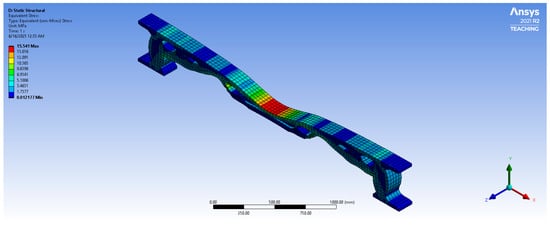

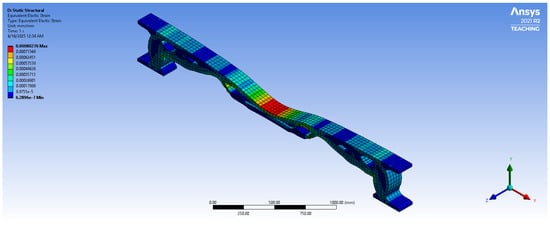

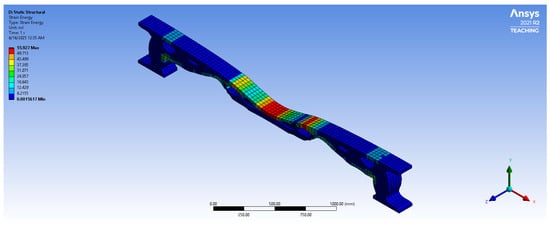

After remodeling, a new finite element analysis was performed. The results showed a maximum compressive stress of 15.5 MPa, which remains below the allowable limit for C20/25 concrete, and a maximum vertical deflection of less than 2 mm, meeting the required criteria. These performance results, including stress, displacement, strain, and strain energy, are summarized in Table 3 (see Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Table 3.

Stress test summary.

Figure 9.

Total deformation of the optimized concrete bench under loading.

Figure 10.

Equivalent von Mises stress distribution in the optimized bench.

Figure 11.

Equivalent elastic strain distribution in the optimized bench.

Figure 12.

Strain energy distribution in the optimized bench.

While this approach is appropriate for initial evaluations, the notoriously nonlinear nature of concrete behavior, particularly its greatly diminished tensile strength, means that future investigations should employ more advanced material models—such as the Drucker–Prager yield criterion—to properly model structural behavior under realistic conditions. In conclusion, the stress analysis performed on the optimized bench shows that it not only achieves significant material efficiencies but also maintains robust structural performance under normal service loading.

2.7. Machine Learning Surrogate Model

A coarse-level surrogate model using deep learning enables the approximation of the finite-element topology optimization process. The network design utilized a three-dimensional U-Net that had approximately 45.5 million parameters structured in the form of an encoder–decoder setup using residual connections and attention-gate connections. The input to the model included seven channels (three spatial coordinates (x, y, z), three components of the forces (Fx, Fy, Fz), and a single boundary-condition channel), and the model’s output represented a single density field normalized between 0 and 1.

The model was implemented inside the software environment of Python 3.13.7 using PyTorch 2.8.0 as the underlying machine learning platform. All the experiments are conducted inside the OS platform of Windows 11 via NVIDIA RTX-class GPUs; the minimum requirement is RTX 2060 (6 GB VRAM), whereas the training setup employs RTX 4090 (24 GB VRAM) and 64 GB RAM. The entire dependency matrix, which consists of 25 software libraries by their exact versions, is provided inside the supplementary document [22].

The training and validating dataset comprise voxelized 3D topology-optimization problems and their respective reference solutions. Each sample consists of paired CSV files: one containing voxelwise spatial and force data, and the other containing scalar material properties. These files were converted into PyTorch tensors for model input. Specifically, we used the disc_complex subset of the SELTO dataset, which includes approximately 4000–5000 samples in the training archive. The dataset was split into 80% training, 20% validation, and a separate test set, following standard practice in surrogate modeling. All samples were accessed and processed using the DL4TO Python library [23,24], which provides structured loading and conversion into PyTorch-compatible formats.

2.8. Hyperparameter Optimization & Metrics

A hold-out validation approach was taken (see Figure 13), dividing the dataset into 80% training and 20% validation sets and a separate test set for final testing. We did not use K-fold validation because the dataset is very large and training a 3D convolution has a very high computational cost; the 80/20 divide is typical for the engineering domain in surrogate modelling.

Figure 13.

Training & Validation Performances.

The hyperparameters were tuned via a random search for 20 runs. The configuration that performed the best employed an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4, a batch size of 4, the optimizer Adam, ReLU activations, and early stopping by 10 epochs without change. Training terminated when loss in the validation set converged for a tradeoff between accuracy and computational cost.

To ensure physical consistency, the learning objective combines multiple loss components into a composite function:

where measures the voxelwise mean-square error between the predicted and target densities, penalizes the predicted fields that violate equilibrium-derived stress consistency, and enforces the spatial continuity of the material distribution (see Figure 14). The weighting factors and were optimized empirically to minimize the overall validation error.

Figure 14.

Force distribution. Black circles represent statistical outliers in the boxplot.

The accuracy of the model was assessed by applying more than fifteen measures for the classes of regression, topological overlap, and statistical correlation. The main measures included the mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), intersection-over-union (IoU), Dice coefficient, and Pearson correlation coefficient. Statistical reliability was approximated via bootstrap sampling and 95% confidence interval estimation.

The performance of the surrogate model was evaluated using a combination of regression, overlap, correlation, and efficiency metrics. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) originate from classical regression analysis and quantify the voxelwise prediction errors between the predicted and reference density fields. The Intersection-over-Union (IoU) and Dice coefficient are widely used in computer vision and medical image segmentation to measure spatial overlap between predicted and ground-truth geometries; here, IoU@0.5 refers to overlap computed after applying a density threshold of 0.5. The Pearson correlation coefficient comes from statistics and assesses the global linear consistency between predicted and reference density distributions. Finally, Inference Time is a standard benchmarking measure in machine learning, reporting the average computational time required for the trained model to generate a prediction per sample [25].

Together, these ready-to-use implementations from the PyTorch ecosystem provide complementary insights: regression errors (MAE, RMSE) capture numerical accuracy, IoU and Dice quantify geometric fidelity, correlation reflects global agreement, and inference time demonstrates computational efficiency compared to full finite element optimization.

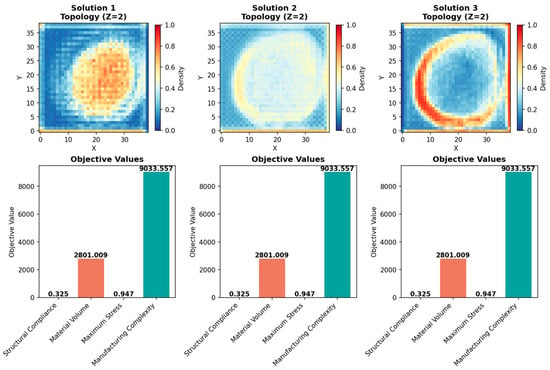

All reported values represent the mean and standard deviation over 50 previously unseen test cases. The benchmarking of the inference was used to evaluate the average prediction time per sample, thereby testing the computational efficiency of the surrogate model. Detailed summaries of the parameter values and measurement definitions are provided in Table 4. Figure 15 provides an evaluation of three topological solutions (Solution 1, Solution 2, and Solution 3) under uniform parameter conditions (Z = 2), highlighting the change in spatial density distributions while showing consistent performance measurements. The top row shows the density heatmaps for each solution showing individual material arrangements: Solution 1 shows a central density core, Solution 2 shows a radially more symmetric distribution, and Solution 3 shows a ring-like arrangement with a priority towards the outer density. The variation between these configurations demonstrates the flexibility of topology optimization in delivering structurally identical but geometrically diverse configurations. The bottom row confirms that all three solutions achieve the same objective values—isotropic structural compliance, metal waste, manufacturing stress, and complexity—demonstrating that several topologies may satisfy the same design requirements. This result has important implications for the addition of aesthetic or manufacturability concerns to the optimization procedure without degrading overall performance.

Table 4.

Metrics.

Figure 15.

Optimization solution.

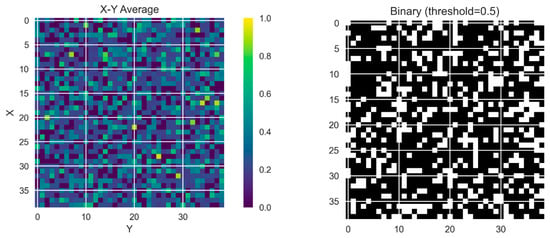

Figure 16 shows the binary conversion of a continuous density field with a threshold value of 0.5. Each matrix cell represents a voxel in the design domain, with white squares indicating the existence of material (density ≥ 0.5) and the absence of black squares (density < 0.5) representing voids. The binary format provides a clear and manufacturable interpretation of the optimized topology, thus allowing the computational output to be transformed into a physical realization. Thresholding plays a critical role in topology optimization techniques since it enables the extraction of the resulting solid geometries suitable for casting/fabrication while retaining the structural intention inherent in the initial density distribution.

Figure 16.

Binary transformation of a continuous density.

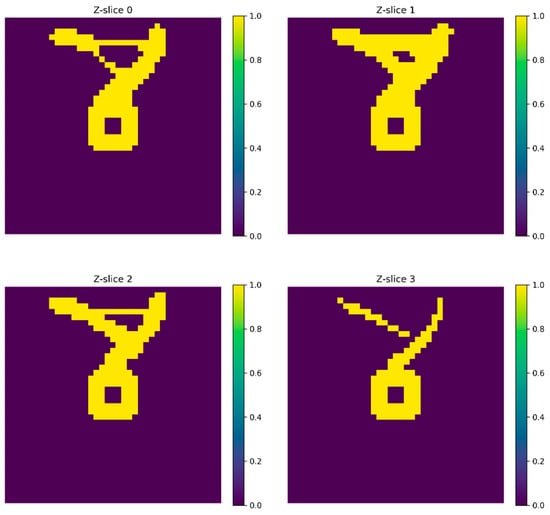

A heatmap representing cross-sectional slices (Z = 0–Z = 3) of a 3D density field is shown in Figure 17, offering insight into the spatial evolution of the material distribution along the depth axis. Each slice was localized at the mid-span of the specimen and reveals distinct patterns of density concentration, with central regions exhibiting higher values (yellow) surrounded by lower-density zones (purple). The gradual shift in shape and intensity across slices suggests a smoothly varying internal topology, indicative of a load-adaptive structure. Such visualization is crucial for validating the continuity and coherence of optimized designs in three dimensions, ensuring that material placement aligns with structural demands throughout the volume. These slices also serve as valuable inputs for postprocessing and manufacturability assessments, particularly in cast-in-place or additive concrete applications.

Figure 17.

Density slices.

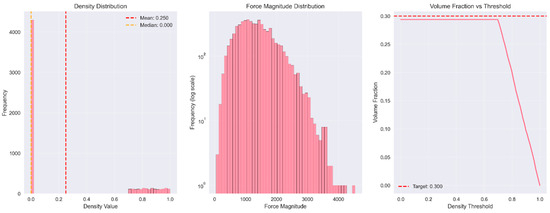

The complete statistical interpretation of the dataset used in the topology optimization process described in Figure 18 follows. The left panel shows the density distribution, which does exhibit a highly skewed profile; in this case, the mean density value (0.259) highlights the dominance of low-density regions accompanied by a stretched tail of elevated density values. The central panel shows the force magnitude distribution in logarithmic form with a central tendency close to two thousand, indicating a flat load intensity distribution over the design area. The right panel shows the volume fraction–density threshold relationship, which shows a sharp dip after the 0.3 threshold—corresponding to the target value—thereby highlighting the material volume’s sensitivity to threshold selection. Such combined visual cues provide valuable information regarding the behaviour of the optimization model’s dynamics, guiding threshold selection and verifying the physical reasonability in the predicted surrogates.

Figure 18.

Force magnitude.

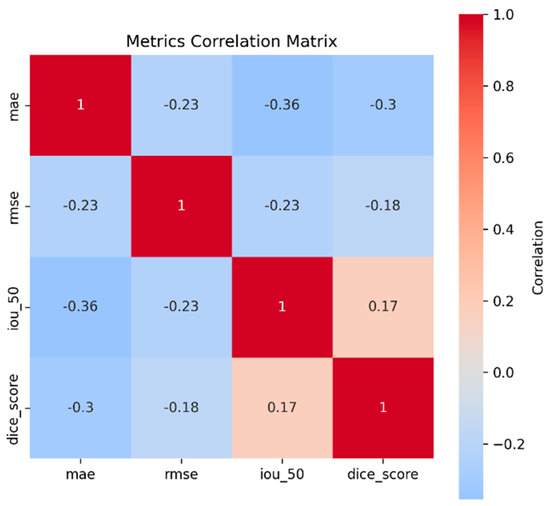

Figure 19 presents a correlation matrix that visualizes the relationships among key evaluation metrics used to assess the performance of the machine learning surrogate model: mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), intersection-over-union at the 0.5 threshold (IoU 0.5), and Dice score. The heatmap reveals that the MAE and RMSE are weakly negatively correlated with topological overlap metrics (IoU and Dice), suggesting that lower error values tend to align with higher spatial agreement between the predicted and ground-truth density fields. Notably, the IoU and Dice score exhibit a modest positive correlation (0.17), reflecting their shared sensitivity to spatial overlap. These insights are critical for multimeric model evaluation, as they highlight trade-offs between regression accuracy and topological fidelity, guiding the selection of loss functions and performance targets in future surrogate model refinements.

Figure 19.

Correlation matrix.

3. Results

The optimization procedure leads to an impressive internal structure in the form of ribs and arches, which efficiently handles load paths while eliminating excess concrete. The total mass decreases from 258.3 kg to 139.4 kg, a reduction of 46%, whereas the seat’s maximum deflection is sustained below the 2 mm limit, and the maximum compressive stress reaches 15.5 MPa, remaining below the allowable limit. This design illustrates that considerable material efficiency can be achieved without compromising structural stability or operation capability.

The use of topology optimization in the design of the concrete bench resulted in the genesis of a prominent internal structure featuring a rib-and-arch pattern, which is a paradigm of load-responsive designs inspired by natural structures such as bone. This new engineering paradigm effectively redistributes material by automatically assigning mass to important load-carrying areas and removing it from less-used areas within the design specifications. The optimized geometry resulting from it, as shown in Figure 5, clearly exhibits this principle by showing well-defined force paths.

The above equations quantify the environmental benefit of the optimized design by linking mass reduction to cement savings and corresponding CO2 emissions. In this case, the optimized bench reduces the concrete mass by 118.98 kg, equivalent to a volume reduction of 0.0497 m3. Assuming a cement fraction of approximately 12.5% for C20/25 concrete and an emission factor of 0.9 kg CO2 per kilogram of cement, this translates into an avoided emission of about 13.4 kg CO2. Although simplified, this calculation demonstrates the tangible mitigation potential of topology optimization in concrete structures and highlights the broader sustainability impact of integrating machine learning surrogates into structural design workflows.

Quantitatively, the optimization procedure achieved a significant reduction of 46% in material usage, decreasing the total mass from 258.3 kg to 139.4 kg. This result is clearly aligned with the objectives of the research, which are to significantly reduce cement use and its equivalent CO2 emissions, thus addressing the global call for resource-efficient construction practices.

The trained 3D U-Net achieved strong agreement with ground-truth topologies, with a mean IoU of 0.75 and Dice coefficient of 0.73 across 50 unseen test cases. The mean correlation coefficient of 0.82 confirms that the network reliably captures spatial density distributions under varying loads and boundary conditions. Importantly, the inference time averaged 24.8 ms per case, representing a computational speedup of over 105× compared with the full ANSYS-based topology optimization process (≈1.4 h per run). These results demonstrate that the surrogate model provides physically meaningful and computationally efficient predictions suitable for rapid conceptual design.

From the structural performance standpoint, the structure adequately meets the fundamental requirements of serviceability and strength:

- Displacement Control: The peak seat deflection remained below the specified 2 mm limit, ensuring the bench’s serviceability under public-use loading conditions. This objective was to minimize compliance (maximize stiffness), which is a commonly used objective in topology optimization, to obtain stiff designs.

- Stress Management: The maximum compressive stress reached 15.5 MPa, remaining below the allowable compressive strength of the concrete. While this demonstrates effective stress management within the design parameters, it is crucial to acknowledge the underlying material model. This study utilized a linear elastic material model with a von Mises stress limit for simplicity in the initial optimization. However, concrete is a complex material with significantly different tensile and compressive behaviours. For a more realistic concrete design, the Drucker–Prager yield criterion is often preferred because it can enforce different strength limits in tension and compression, whereas von Mises enforces equal limits. This choice implies that while the design is robust within the linear elastic assumption, further validation with more sophisticated, nonlinear concrete models (including cracking, creep, and compression softening) would provide a more accurate representation of real-world performance.

The application of a density threshold of 0.3 for generating a constructible solid from the optimized topology serves as an additional processing step. Although this method yields a clean and manufacturable geometry, the literature reveals that solutions generated through topology optimization with imposed stress constraints often require extensive postprocessing steps before actual construction can begin. This heuristic postprocessing technique has been found to have a significant effect on the performance characteristics of an optimized structure, leading to high variability in the experimental results. These findings highlight the need to incorporate construction and manufacturability considerations directly into topology optimization methods to minimize or potentially eradicate postprocessing requirements. Future work will examine methods for more effectively incorporating these manufacturing constraints into optimization algorithms to address potential inconsistencies between the idealized optimized structure and the ultimate constructed product.

The successful application of this complex rib-and-arch structure as a “cast-in-place” element testifies to the suitability of concrete for topologically optimized designs. As a liquid in its initial state, concrete demonstrates greater flexibility, allowing for the production of complex forms that may be difficult with other materials. This is in contrast to 3D concrete printing, which faces manufacturing constraints related to nozzle size, path continuity, and overhang angles.

4. Translation from Optimized Topology to a Buildable Design

Topology optimization can yield highly efficient and sometimes counterintuitive structural layouts; however, the results produced by these algorithms are rarely usable directly for implementation, especially in the case of concrete structures. Bridging the gap between computational design and practical use involves the crucial step of transforming the optimized topology into a viable design that meets regulatory guidelines and is manufacturable.

4.1. Postprocessing of Optimized Geometry

The output of topology optimization is typically a density distribution or a geometry with complex, organic forms and fine features. To make this geometry buildable:

- A density threshold is applied (e.g., 0.3 in this study) to distinguish between solid and void regions, resulting in a clear, manufacturable solid.

- Smoothing and simplifying the geometry are often necessary to remove impractically thin webs and sharp corners, which may be difficult or impossible to cast with conventional formwork.

- Symmetric planes and member-size control (such as a filter radius) are used during optimization to avoid features that are too small to construct and to ensure a visually balanced layout.

4.2. Manufacturability Considerations

Despite its formability, concrete imposes practical constraints:

- Minimum member thickness must be respected to ensure proper compaction and durability.

- The geometry must allow for demolding, reinforcement placement, and concrete pouring without creating trapped voids or inaccessible regions.

- Complex internal geometries, such as the rib-and-arch layouts produced by topology optimization, may require advanced construction techniques, such as 3D-printed formwork or segmental casting.

4.3. Reinforcement Integration

For reinforced concrete structures:

- The optimized shape must be adapted to accommodate reinforcing bars, which may require further modification of the geometry to ensure proper cover, anchorage, and placement.

- Strut-and-tie models derived from topology optimization can guide the reinforcement layout, especially in regions with nonstandard force flow paths.

4.4. Compliance with Codes and Standards

The final design must be checked against relevant building codes for:

- Minimum and maximum cross-sectional dimensions.

- Serviceability and strength requirements under various load cases.

- Durability, fire resistance, and other regulatory criteria.

4.5. Digital Fabrication and Advanced Construction Methods

To realize complex optimized geometries, emerging construction technologies can be leveraged:

- 3D-printed formwork or direct concrete printing can enable the construction of freeform shapes that would be prohibitively expensive or impossible with traditional methods.

- Modular or segmental constructions may simplify the assembly of intricate forms.

4.6. Final Geometry Reconstruction and Visualization

Following the topology optimization and stress validation, the optimized geometry was reconstructed into a smooth solid model suitable for physical interpretation and fabrication. As the raw output of the topology optimization is voxel-based and not directly manufacturable, the geometry was remodeled while preserving the primary structural load paths identified by the optimization as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. The final solid model was then rendered for visualization using Blender, which provided a clean and realistic representation of the optimized bench shape. This rendered model is shown in Figure 20, highlighting the rib-and-arch structural configuration that enables material efficiency while maintaining load-carrying performance.

Figure 20.

Rendered visualization of the optimized bench geometry.

5. Conclusions

This research demonstrates the effectiveness of topology optimization as a key tool for the sustainable design of concrete structures. Through the optimization of material use with continuing fulfilment of structural requirements, the proposed approach satisfies both ecological objectives and increases resource effectiveness. The methods and achievements discussed in this work can be applied to any structural component, thus enabling wider use of optimization-based design for the construction and engineering fields.

This design approach in question will be extended to include multimaterial optimization, i.e., by embedding the reinforcing phase (in the form of steel) directly in the optimization procedures of reinforced concrete (RC) members. The method, as described by Bogomolny and Amir [26], involves the optimization of the spatial distributions of concrete and steel, which are categorized into two separate nonlinear candidate materials, each with its own distinct yield limit and post-yield response. As a result, this approach enables the conceptual design of RC members that better capture the true material behaviors concerned and may also simplify the construction of strut-and-tie models (STMs) for complex D-regions directly from the optimization results.

5.1. Findings

- 46% mass reduction: The topology-optimized bench achieved a 46% reduction in material usage (from 258.3 kg to 139.4 kg) while maintaining structural performance, demonstrating significant potential for reducing cement consumption and associated CO2 emissions.

- Structural integrity preservation: The optimized design limits the vertical displacement to ≤2 mm and the peak compressive stress to 15.5 MPa (below the allowable 20 MPa), confirming compliance with serviceability and safety requirements.

- Efficient Load Paths: The resulting rib-and-arch topology efficiently redistributed material to critical load-bearing regions, eliminating nonstructural concrete masses without compromising stiffness.

5.2. Future Work

Experimental Validation: A critical follow-up process requires empirical testing of prototypes, either 3D-printed or cast, to verify computational predictions under actual loading conditions. This step is crucial because it currently lacks experimental validation, which is a significant barrier to further research and practical application of topology optimization techniques in reinforced concrete (RC) design. Prototypes are to be produced, perhaps using CNC-milled formwork (say, made from Styrofoam or wood) to achieve complex topology-optimized shapes, a tested method for such structures. The validation process involves measurement of key performance parameters, including stiffness, ultimate strength, ductility, and perhaps control of the propagation of cracks, with tests compared with normally designed members to quantify the benefits of the optimized designs.

Multi-Material Optimization: Examine the increased use of manufacturing constraints. While past research has focused primarily on cast-in-place concrete, its extension to 3D concrete printing (3DCP) requires the intentional incorporation of parameters such as the nozzle size, printing trajectory continuity, and overhang angle management into the topology optimization framework. This intentional emphasis aims to create designs that are fundamentally manufacturable, thus avoiding complex postprocessing protocols that may adversely affect the performance of the optimized structures. Multi objective optimization involves integrating sustainability measurements directly into the objective function, beyond just mass reduction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.A. and M.G.; methodology, M.M.A. and M.G.; software, M.G. and M.M.A.; validation, S.B., M.G. and M.M.A.; formal analysis, M.G. and M.M.A.; investigation, M.M.A. and M.G.; data curation, M.G. and M.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.A. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, S.B. and R.M.; visualization, S.B. and R.M.; supervision, S.B. and R.M.; project administration, S.B. and R.M.; funding acquisition, S.B. and R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andrew, R.M. Global CO2 emissions from cement production, 1928–2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1675–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.M.; Muntean, R. Marble Powder as a Sustainable Cement Replacement: A Review of Mechanical Properties. Sustainability 2025, 17, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crave, F.; Bischoff, L. Klimaschutz in der Beton-und Zementindustrie–Hintergrund und Handlungsoptionen; WWF Deutschland: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stoiber, N.; Kromoser, B. Topology optimization in concrete construction: A systematic review on numerical and experimental investigations. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2021, 64, 1725–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschenauer, H.A.; Olhoff, N. Topology optimization of continuum structures: A review. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2001, 54, 331–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmund, O. Design of Material Structures Using Topology Optimization. 1994. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261173987 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Deaton, J.D.; Grandhi, R.V. A survey of structural and multidisciplinary continuum topology optimization: Post 2000. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2014, 49, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Liu, K.; Zheng, C. A review on topology optimization of concrete structures. Eng. Struct. 2023, 17, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambach, M.; Volkmer, D. Properties of 3D-printed fibre-reinforced Portland cement paste. Autom. Constr. 2019, 103, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, R.D.; Zhang, X.S. Sustainability-oriented multimaterial topology optimization: Designing efficient structures incorporating environmental effects. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2025, 68, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.F.; Holloway, D.M.; Biggers, S.B. Stability experiments on the strongest columns and circular arches. Exp. Mech. 1971, 11, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, M. La Statique Graphique Et Ses Applications Aux Constructions, 7th ed.; Académie des Sciences: Paris, France, 1886; Volume 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, I. Geschichte der Mechanischen Prinzipien, 7th ed.; History of mechanical principles, in German; Birkhäuser: Stuttgart, Germany, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, T. Über die Form architektonischer Säulen. In Bulletin de la Classe Physico-Mathématique de l’Académie Impériale Des Sciences de Saint-Pétersbourg; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 1851; Volume 9, p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- Olhoff, N.; Rønholt, E.; Scheel, J. Topology optimization of three-dimensional structures using optimum microstructures. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 1998, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Yan, H.; Tao, C.; Wang, X.; Guan, S.; Zhang, Y. Integration of Finite Element Analysis and Machine Learning for Assessing the Spatial-Temporal Conditions of Reinforced Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, P.C.; Thomoglou, A.K. Rapid shear capacity prediction of TRM-strengthened unreinforced masonry walls through interpretable machine learning deployed in a web app. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 110912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, H.; Kelishadi, M.; Bahmani, H.; Wu, C.; Ghiassi, B. Development of sustainable HPC using rubber powder and waste wire: Carbon footprint analysis, mechanical and microstructural properties. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2024, 29, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Shin, D.; Kang, N. Topology optimization via machine learning and deep learning: A review. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2023, 10, 1736–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnovik, I.; Oseledets, I. Neural networks for topology optimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.09578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSalvo, G.J.; Swanson, J.A. ANSYS Engineering Analysis System User’s Manual; Swanson Analysis Systems: Houston, PA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer, S.; Erzmann, D.; Harms, H.; Falck, R.; Gosch, M. SELTO Dataset (-) [Dataset]. Zenodo 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, G.; Drake, F.L. Python Reference Manual; Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica (CWI): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-NET: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogomolny, M.; Amir, O. Conceptual design of reinforced concrete structures using topology optimization with elastoplastic material modeling. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2012, 90, 1578–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).