1. Introduction

Bridges are essential to transportation systems and play an important role in daily mobility. Many of these structures are made of steel and are exposed to environmental conditions, including rain, temperature fluctuations, and pollution, which cause corrosion over time. Regular inspections are necessary to ensure safety and functionality, with visual surveys being the most common method for detecting early damage. Although these inspections rely on human judgement, they help identify visible issues such as rust or missing coatings. Recent work has also explored the use of imaging technology and BIM for visual inspection tasks, offering new ways to collect and process field data [

1], such as those by Scianna et al. [

2] and Brighenti et al. [

3], confirming that combining visual inspection with clear documentation is an efficient first step in monitoring the health of steel structures.

Bridge maintenance played a significant role in extending the life of structures and reducing long-term repair costs. Without proper maintenance, corrosion and other types of damage can progress, leading to structural failure. Corrosion is also a common issue in mixed and reinforced concrete bridges, where steel reinforcement is affected by moisture and chemical reactions. Similar digital workflows can support their assessment. Maintenance strategies are most effective based on accurate and up-to-date information from field inspections. Manual inspection records often lack traceability, which can complicate data comparisons and long-term tracking. Systems are needed to allow the organisation to update and analyse inspection data more efficiently. In this context, digital tools such as Building Information Modelling (BIM) are considered valuable.

Ensuring the long-term integrity of bridges depends on reliable upkeep guided by condition-based data. Without maintenance, small areas of corrosion can expand and weaken structural members. The success of any maintenance strategy depends on accurate and up-to-date information gathered through field inspections. However, manual reports are often difficult to manage, compare, or update. There is an increasing need for structured tools to organise and track inspection data over time. EU-supported research has outlined several technologies that improve inspection quality, data consistency, and visual documentation of bridge health [

4], where maintaining visual records is critical.

A 3D digital model of the structure created using Building Information Modelling (BIM), which includes both geometric and condition data. These benefits have been demonstrated in recent studies that used deep learning and BIM integration for mapping corrosion conditions in steel structures [

5,

6]. However, most existing BIM-based inspection workflows do not clearly show how their procedures can be repeated or how much manual effort they require. The proposed workflow was designed to lower labour demand by using automated colour mapping in Dynamo, which improves comparison stability between different inspection periods. Several recent studies, including a BIM-based rehabilitation workflow for heritage steel bridges by Crisan et al. [

7]. It has integrated inspection results directly into the model, enhancing communication between engineers and ensuring that maintenance decisions are based on reliable information [

8].

Previous studies have established the value of structured bridge condition assessment as a foundation for effective maintenance planning. The Lombardia regional guidelines, for example, describe a systematic approach to bridge monitoring developed through collaboration between Politecnico di Milano and local authorities [

9]. Their MoRe framework identifies four key decision-making areas—maintenance management, emergency response, safety assessment, and code standardisation—where structural monitoring plays a pivotal role. Several recent BIM lifecycle planning frameworks have also incorporated corrosion tracking into digital models for infrastructure maintenance [

3], enabling the more efficient allocation of maintenance resources while reducing uncertainty in bridge performance forecasting.

This research aims to examine a steel bridge structure using digital assessment methods and to develop observation systems for future monitoring needs. Traditional bridge inspection techniques rely on manual visual assessments, in which engineers physically inspect structural components for signs of rust, cracks, and coating deterioration. Though widely used, manual inspection methods have significant limitations in detecting early-stage damage and are susceptible to environmental and human factors. Variations in lighting, weather conditions, and the inspector’s level of experience can lead to subjective evaluations, making it challenging to accurately track the progress of corrosion. Furthermore, the reliance on manual periodic inspections allows corrosion damage to develop undetected between inspections, leading to unexpected structural failures or costly repairs.

Recent research has explored digital solutions, including drone-based inspection, mixed reality, and artificial intelligence, to assess corrosion and monitor structural integrity, overcoming the limitations of traditional inspection methods [

10,

11]. Building Information Modelling (BIM) combined with extended reality tools has gained considerable attention as a method for visualising and documenting the condition of bridges [

12]. BIM offers a parametric, three-dimensional (3D) digital representation of a structure, enabling engineers to map corrosion distribution, monitor deterioration over time, and plan maintenance activities efficiently. The integration of real-time condition data into a centralised digital model makes BIM a powerful tool for bridge management [

13].

This study proposed a structured and replicable workflow for visual corrosion assessment using BIM [

14,

15]. A five-level corrosion severity grading system was developed based on surface changes identified in matched photographs from two inspection periods. These grades were integrated directly into a Revit-based digital model through a customised colour override script in Dynamo. The proposed method provides an organised framework for visually tracking corrosion in steel bridge structures and supports future decision-making processes as well as digital twin development.

Advanced tools such as thermal imaging, infrared thermography, or corrosion-detecting UAVs offer promising capabilities for large-scale bridge inspections. However, this study focused on accessible, low-cost image-based inspection to ensure broad applicability.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study Characterisation

The object of study in this work is a steel pedestrian bridge, depicted in

Figure 1, constructed in 2000, that connects the two campuses of the University of Aveiro—the Santiago and Castro campuses, situated in the centre of mainland Portugal. It is 318 m long and approximately 4 m wide. It spans a seasonal branch of the Aveiro lagoon. Nine steel columns support it, each measuring 18 m in height.

The primary structure of the bridge consists of steel structural components and a concrete deck. A truss system provides the main structural support. This design was chosen to ensure high resistance to various loading conditions. However, the exposure of the truss system makes the structure more susceptible to long-term corrosion. Environmental conditions, such as humidity, rainfall, temperature fluctuations, air pollution, and proximity to the ocean, can significantly affect steel surfaces, accelerating their degradation. Additionally, the seasonal river beneath the bridge increases moisture exposure, further contributing to the structure’s vulnerability to long-term corrosion.

Allowing corrosion to progress diminishes material integrity, reduces the structural lifespan of the bridge, and compromises its overall safety. To ensure long-term performance and prevent significant damage, regular maintenance and effective monitoring systems are essential. Maintaining the bridge in a safe condition requires continuous assessment, monitoring, and the implementation of detection methods that can identify early signs of deterioration [

24]. The case study represents a typical example of steel bridges in Portugal. Similar truss structures are often built near coastal or lagoon environments, where humidity and salt exposure create comparable corrosion conditions. The observed damage patterns can therefore be considered representative of regional bridge typologies, and the proposed workflow is suitable for broader application in similar settings.

3.2. BIM-Based Corrosion Visualisation and Monitoring

This research integrates on-site observation and BIM to analyse and document corrosion damage of a pedestrian bridge. Two on-site inspections were conducted in February 2024 and April 2025, during which detailed photographs and condition reports were collected. These data were used to create a Revit-based BIM model that incorporates a colour-coded grading system to classify the severity of corrosion across various bridge components. This approach enabled the creation of a structured visual representation of the damage, facilitating more precise identification of areas requiring immediate attention.

The colour-coded system assigns different colours to minor, light, and moderate corrosion, facilitating the identification of high-risk areas and the tracking of corrosion progression by engineers and maintenance teams. This enhances the efficiency of maintenance planning by enabling decision-makers to prioritise repairs based on the severity of the damage. Rather than relying only on written reports and manual notes, engineers can access a visually detailed 3D model, thereby reducing the risk of overlooking critical areas of deterioration.

Beyond providing a snapshot of the bridge’s current condition, BIM offers a structured method for long-term monitoring and maintenance. Recent research highlights that integrating Scan-to-BIM data with predictive models enhances accuracy in deterioration forecasting and maintenance scheduling [

25]. With a digital model established, future inspections can be compared against historical data, allowing technicians to assess whether corrosion is progressing at an expected rate or accelerating beyond safe limits. This method provides a structured visual approach to corrosion assessment, which reduces subjectivity in classification but still requires some manual steps, such as photo alignment, that may introduce limited observer interpretation.

3.3. Challenges in Corrosion Detection and Maintenance

Despite advancements in digital corrosion assessment, steel pedestrian bridges continue to face significant maintenance challenges. A primary difficulty lies in detecting corrosion at an early stage, before it causes substantial structural weakening. Corrosion often initiates in hidden or hard-to-reach areas, such as welded joints, beneath bridge decks, or inside hollow steel sections, making it difficult to identify with traditional visual inspections alone. Small cracks or rust formations may develop unnoticed without regular monitoring, eventually leading to material loss, reduced load capacity, and higher repair costs [

26], Deep-learning-based corrosion detection techniques have recently improved early defect recognition and reduced human bias in visual inspection workflows [

27].

In the case of the pedestrian bridge under study, the proximity to water sources and the marine environment is known to accelerate corrosion processes. Exposure to varying humidity levels, seasonal temperature changes, and airborne pollutants contributes to the oxidation of steel and the deterioration of protective coatings. These effects are especially pronounced in structures located near rivers or coastal areas, where salt accumulation and moisture penetration can compromise material integrity over time [

28]. To prevent such degradation, regular inspections and maintenance interventions have been emphasised in recent research, particularly for steel bridges with visible signs of wear [

29]. Even in the absence of heavy traffic loads, pedestrian bridges remain vulnerable to surface degradation due to constant exposure to environmental conditions [

30].

Image alignment was performed manually using fixed structural markers such as column numbers, weld seams, and truss intersections. Although this introduces observer subjectivity, these locations were consistent and traceable across inspections.

3.4. Practical Monitoring Strategy Development

A structured monitoring plan is essential to complement field assessments and BIM. While this study demonstrates a short-term application using two inspection cycles, the proposed workflow is designed to support future long-term monitoring. A monthly inspection routine is suggested as a scalable and realistic solution, allowing regular updates of corrosion status without excessive resource demands.

This aligns with established regional frameworks for infrastructure condition-based planning, such as the Lombardia guidelines [

9].

By integrating BIM with structured monitoring, a digital record of corrosion progression can be maintained, reducing the dependence on traditional documentation methods. Each new inspection can be compared against the existing BIM model, allowing the identification of changes in corrosion severity over time. Furthermore, implementing a standardised data collection ensures that inspections remain consistent and reliable, minimising the risk of overlooking critical structural issues.

A well-designed monitoring plan also enables proactive maintenance planning. Instead of reacting to unexpected structural deterioration, historical data can be leveraged to predict maintenance needs, ensuring that repairs are scheduled before damage becomes severe and costly. This approach reduces long-term maintenance costs, improves safety, and extends the service life of the bridge.

3.5. Grading Damage

Corrosion Severity Grading

The corrosion severity grading system described in this section was developed not only for assigning condition levels but also to support a structured workflow for visual corrosion assessment in bridge inspections. A sequence of image matching, surface evaluation, grade assignment, and Revit model integration was followed to ensure consistency and clarity. This method was designed to be repeatable and applicable to similar steel pedestrian bridges. The process enables surface-level deterioration to be documented and visualised in a format compatible with long-term digital monitoring.

The corrosion severity grading system was defined through visual interpretation based on surface changes observed during different inspection periods. Each inspection provided high-resolution images of structural elements from matching locations, allowing direct comparison of corrosion development over time.

Key indicators used to describe degradation level included the following:

- -

Surface discolouration;

- -

Coating loss;

- -

Rust formation;

- -

Visible metal flaking.

The use of repeated image locations helped ensure that condition differences were associated with time-based progression rather than view angle or lighting variation.

The corrosion grading method applied in this study was adapted from ASTM D610 [

31]. While the original numeric rating scale and specific rust pattern charts were reviewed, the system was simplified to improve consistency with photographic field data and compatibility with digital modelling tools. The adapted classification was designed to reflect observable surface conditions and enable straightforward integration into the BIM environment.

The adaptation involved redefining visual thresholds and simplifying categories to enhance clarity in digital implementation. A summary of the modified grading levels is presented in

Table 2. A five-level scale was selected to maintain a balance between detail and clarity, making it suitable for integration into digital inspection environments.

Table 2 summarises descriptive criteria for each severity level. Grade 1 refers to elements with no corrosion or intact coatings, Grade 2 indicates early-stage corrosion, including light surface rust or spotting. Grades 3 and 4 represent progressive deterioration, characterised by coating failure, visible pitting, and partial section loss. Grade 5 represents elements with extensive surface damage, including deep pitting and metal flaking, or significant material degradation. These levels are defined based on visual field features, allowing for rapid and consistent assessment across the structure.

Table 2 defines the corrosion severity levels used in this study. This classification is based on visual inspection criteria and adapted from the ASTM D610 [

31] standard for integration into the BIM model.

To support visual communication, the corrosion grades were linked to modelled elements in Revit using colour-coded overrides. This integration allowed inspectors and engineers to identify the severity of damage during digital reviews directly. The BIM environment thus served both as a digital inspection record and a collaborative tool for decision-making. To improve consistency, a simplified grading structure is supported by standardised visual references, tabular summaries, and visual reference examples. Each assigned grade was also accompanied by a confidence level, classified as High, Medium, or Low. Based on predefined criteria, including image clarity, angle consistency, and repeatability of visual assessments across different inspection periods. The rust percentage for each grade was estimated by visual inspection in the photograph, following the ASTM D610 [

31] reference bands adapted for field images.

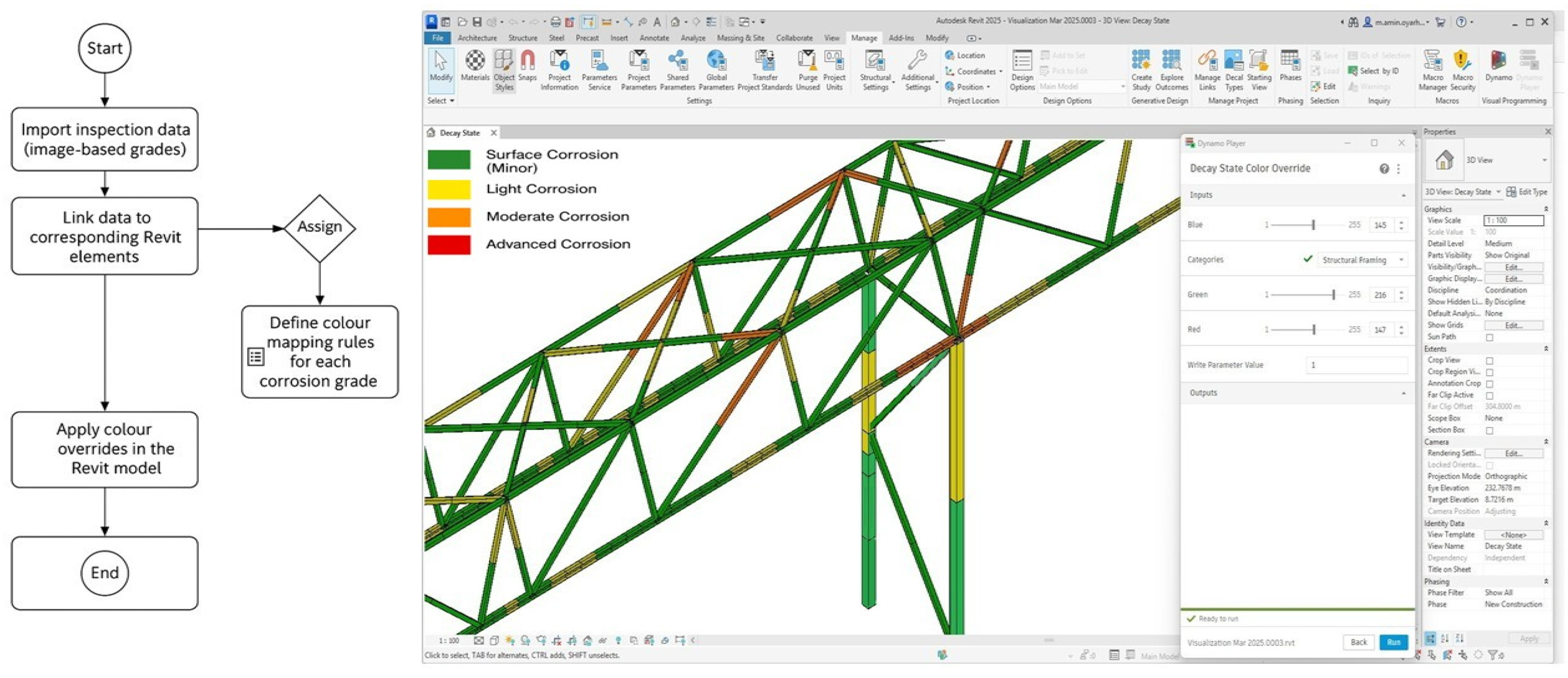

3.6. Workflow for Corrosion Severity Grading and BIM Integration

Figure 2 illustrates the workflow designed to assess corrosion severity and integrate it into the BIM environment. The workflow was developed to be reproducible by others. The repeatable steps include selecting matched photo pairs using fixed reference points such as column or weld numbers, assigning corrosion grades according to

Table 2, recording element IDs and grade values in a standard spreadsheet, and importing these data into Revit through Dynamo Player. The process begins with the acquisition of field images from two visual inspection campaigns, followed by the identification of matching photo pairs using physical reference points. A visual analysis is then conducted on surface conditions, including coating loss, rust patterns, and flaking. Based on these observations, each element is assigned a corrosion severity grade ranging from 1 to 5. As shown in

Table 2, this information is imported into the Revit model using a Dynamo Player script, which applies colour-coded overrides.

To ensure transparency, each visual classification was accompanied by a confidence level determined by three factors: image clarity, consistency of camera angle between campaigns, and the inspector’s certainty in identifying corrosion features. Confidence was assessed using a qualitative scale with three levels: High, Medium, or Low. Finally, the graded elements were reviewed within the 3D model, allowing spatial organisation of the inspection data and supporting future maintenance decisions.

Descriptive Classification of Corrosion Grades

The corrosion severity grading scale applied in this study was based on the extent and depth of corrosion damage, as summarised in

Table 2. The structural steel system was assessed according to the 5th level scale:

- -

Grade 1: Surface Corrosion (No corrosion or Minor):

This early stage of corrosion (

Figure 3) involves minor surface rust and barely visible cracks. The steel remains structurally sound, with no significant material loss. Visualisation techniques such as infrared thermography and high-resolution photography can help detect these minor surface changes. Basic cleaning and protective coating applications are recommended at this stage to prevent further corrosion.

- -

Grade 2: Light Corrosion:

Cracks are now more apparent (

Figure 4), with light pitting and minor material loss. Ultrasonic Testing (UT) helps to detect the depth of the cracks, while laser scanning provides detailed 3D models of surface-level damage. This grade requires routine maintenance, such as cleaning and applying protective coatings.

- -

Grade 3: Moderate Corrosion:

Moderate corrosion involves deeper penetration into the steel, causing visible rust, pitting, and material loss (

Figure 5). Although it remains functional, the structure is showing signs of weakening. Visualisation techniques, such as magnetic particle inspection (MPI) and digital twins, provide detailed damage assessments. Localised repairs, such as welding or patching, may be necessary.

- -

Grade 4: Advanced Corrosion:

Corrosion has progressed, resulting in deeper cracks, more substantial material loss, and extensive rust spots (

Figure 6). The structural integrity is noticeably compromised. Visualisation techniques such as acoustic emission testing (AET) and fibre optic sensors can monitor the real-time progression of damage. Repairs at this stage are more intensive and may involve replacing corroded parts.

In this study, the corrosion severity grading system was developed solely based on visual inspection findings from the actual bridge. No external reference images were used. All grading levels were assigned by comparing surface changes such as coating loss, rust expansion, and localised texture variation observed in matching photographs taken during the February 2024 and April 2025 inspections. No areas with critical corrosion or advanced structural damage (Grade 5) were recorded during the inspection campaigns.

3.7. Location Sensitivity

To support the classification of structural components by sensitivity, this section presents a zoning configuration based on the function and vulnerability of each element (

Table 3). Components are grouped into three zones: high sensitivity (main load-bearing parts such as beams, trusses, and primary connections), medium sensitivity (braces and secondary supports), and low sensitivity (non-structural surfaces and protective coatings). This method is consistent with earlier studies on steel bridge corrosion, which found that damage to key structural elements can have a greater effect on overall safety.

For example, Ghiasi et al. [

32] showed that corrosion in girders and joints had a more substantial impact on bridge performance than corrosion in other parts. Their results confirm the importance of focusing inspection and maintenance efforts on the most critical zones.

Grading Corrosion with Visualisation Methods

In this study, corrosion grading was supported using visual methods, including inspection photographs and 3D BIM. The main goal was to identify and document changes in the surface condition of steel elements by comparing images from two field inspections. This methodology enabled the analysis of rust buildup, crack formation, and coating loss over different periods. Examining surface patterns would allow experts to assign a specific grade of corrosion to each bridge component, eliminating the need for specialised instruments during routine safety checks.

To facilitate a clear comparison between inspection results, the visual grading system (

Table 2) was implemented directly within the BIM environment. The photographs were analysed and used to identify which parts of the bridge had remained stable and which had exhibited increased corrosion. This information was then transferred into the 3D model using the colour-coded system that matched the corrosion severity levels described in

Table 2. The visual tools made it possible to display condition changes in a clear and organised manner. This method also improved the readability, communication, and use of inspection results to support maintenance planning in this way. Colour-coded digital twins were used to represent different grades of corrosion severity. This visual scale helped inspectors and engineers quickly understand the condition of structural elements within the model.

- -

3D surface models from LiDAR or laser scanning can accurately visualise crack length and width in the early stages of corrosion. This is crucial for identifying and tracking the spread of damage.

- -

Depth measurements from ultrasonic testing can provide insight into the internal progression of corrosion, particularly in grades 3 through 5.

- -

Time-series data collected by fibre optic sensors can visualise corrosion growth over time, helping to predict when a crack may reach a critical stage. This is achieved using histogram-based quantification methods to track the spread of damage over time [

33].

- -

Machine learning algorithms can enhance predictive analysis by utilising historical data from sensors to estimate future corrosion rates and recommend pre-emptive maintenance actions.

3.8. Visual Inspection

Although widely applied, visual inspection provides surface-level insights that are now enhanced by digital tools such as BIM and drone imaging, improving consistency and documentation. It involves trained inspectors physically examining the bridge for visible signs of rust, pitting, cracks, or other deterioration caused by corrosion. Tools like drones or robotic crawlers can access hard-to-reach areas, such as the undersides of bridges or structures in dangerous locations. This inspection process helps assess the condition of coatings and areas prone to moisture retention, which are early indicators of corrosion. These can be enhanced using Otsu’s thresholding method (Otsu-based image segmentation) and Sobel filters for automated crack edge detection [

34].

The advantages of visual inspection include its simplicity and cost-effectiveness, allowing for real-time identification of surface damage. Advanced technology, including uncrewed aerial vehicle (UAV)-based systems integrated with deep learning models, has been demonstrated to enhance crack detection coverage and reduce human error during bridge inspections, improving accuracy and coverage [

35]. As visual inspection is limited to surface-level corrosion and cannot detect internal damage, continuous or real-time monitoring is challenging without combining visual inspection with other techniques.

4. Digital Twin

4.1. Digital Twin Technology

Digital modelling of corrosion conditions through BIM provides visual clarity and creates the foundation for a digital twin of the bridge [

36]. A digital twin is a continuously updated digital replica of the physical structure that integrates geometric data, inspection results, and, in advanced cases, real-time sensor inputs. The Revit model developed in this study already contains spatial and condition-based information for each component, making it highly suitable for future expansion into a digital twin system [

37]. Similar digital frameworks have been proposed for reinforced concrete structures to manage corrosion data and sensor information within digital twins [

24]. By transforming the BIM model into a digital twin, a living model that reflects the structure’s real-time condition can be created, similar to studies where IoT sensors support dynamic condition updates in reinforced concrete bridges [

38]. This model promotes ongoing assessment, risk evaluation, and bridge maintenance planning, consistent with digital twin frameworks developed for structural asset management [

39]. This enables a faster response to early signs of deterioration and facilitates more informed long-term decision-making.

A digital twin helps track past and current condition data for steel bridges exposed to corrosion. This enables engineers, inspectors, and managers to understand the structure better and work together more effectively. As new data from inspections or measurements is added over time, the digital twin becomes more detailed and more helpful for decision-making. As a digital twin is a virtual copy of the real bridge, it can be updated in real time. It can include information from sensors and structural models (like Finite Element Models (FEMs)).

To clearly show damage, a digital twin can use the colour-coded grades in

Table 2 to mark different levels of corrosion and their consequent evolution over time, supporting effective maintenance and repair actions. This colour system helps to find which parts need attention or repair quickly.

4.2. Visual Comparison of Corrosion Progression Using Revit Model

Two Revit models were developed from visual inspections conducted in February 2024 and April 2025 to understand how corrosion has progressed over time on the steel pedestrian bridge. The primary inspection methods for examining the structure utilised drone platforms and handheld devices. These tools provided broad access to various surfaces and viewing directions, which helped achieve thoroughness.

This process aligns with recent studies that utilise image-guided BIM to identify cracks in concrete bridges through structured mapping techniques [

40]. The inspection focused on all surfaces that were easily observable on the truss roof, column structures, handrails, and the deck beneath. Surface observation results from the field were transferred into Revit to allow 3D examination of each bridge component. Using the Decay State Colour Override tool, Dynamo Player enabled the visual automation of inspection results (

Figure 7). Colour codes were assigned to each structural element based on inspection findings using this feature. The model functioned as both a digital and interactive tool, serving two primary purposes: providing a visual representation of the bridge and tracking its condition over time.

To facilitate visual comparison of corrosion levels across the model, a Dynamo Player script was developed to automatically apply colour overrides based on each element’s assigned grade. The overall workflow and visual scripting steps used for this automation are summarised in

Figure 8.

To complement the schematic workflow presented earlier in

Figure 8,

Figure 9 shows the actual Dynamo script used to implement colour overrides based on corrosion severity. The script extracts element parameters related to the “Decay State” using the Element. The GetParameterValueByName node processes the values and maps them to colour ranges via the Colour node.ByARGB. These are then assigned to bridge elements using OverrideGraphicSettings. By Properties and Element.OverrideInView. The colour values correspond to predefined corrosion grades and are rendered directly within the Revit environment. This real implementation enables the automatic visual classification of inspection data within the BIM model, supporting clearer condition tracking and aiding in maintenance planning.

To validate the proposed method, the Dynamo-developed script was executed in the Revit environment. This step demonstrates the transition from a conceptual workflow to a real-world application.

Figure 10 illustrates both the simplified flowchart used to guide the process and the actual BIM model with colour-coded elements reflecting their corrosion severity. The Dynamo Player interface is shown on the right, where input parameters, colour values, and structural categories are selected, allowing automated visualisation directly within the 3D model.

The script was designed to automatically assign colour codes (according to

Table 2 grades) to different elements of the bridge model based on the corrosion grades identified during inspection. The grades were first recorded in a spreadsheet, which included the corresponding element IDs. These values were then used to control the colour override of each element within the model, ensuring that the correct level of corrosion was visually represented.

The grading system was more easily applied across structural components through this method. Instead of assigning colours manually, the script read the inspection data and automatically used the colours. By automating the colour application, the process was made faster, more consistent, and less prone to error. The system also enables quick updates when new inspection data becomes available.

The use of Dynamo and Revit together provided a clear visual representation of the bridge’s corrosion condition over time. The workflow allowed changes from the first to the second inspection to be viewed directly within the BIM model. As a result, the model not only showed the current condition but also helped to identify areas where corrosion had increased. This approach supports better maintenance planning by making condition changes easy to detect and understand. By embedding inspection data, the Revit environment enabled users to locate specific components and compare their conditions without consulting external reports. This structured workflow aligns with BIM-based rehabilitation models commonly used in steel infrastructure, where defined information delivery plans and BIM execution protocols facilitate lifecycle-driven maintenance and informed decision-making processes [

8].

Single elements can be examined alongside others from various inspection checkpoints using the 3D system. Accurate visual exams become possible because patterns can be more easily recognised, material behaviour can be more closely monitored, and maintenance plans can be more effectively organised through informed planning. The central database role of the digital model enables more efficient future inspection activities and maintains consistent assessment procedures. These models are used as a robust integrated assessment system by integrating structural information and managerial decisions to support long-term asset management goals. An analysis was conducted between inspection pictures collected during both surveys to confirm the model-based findings. The study focused on the structural components identified by the corrosion grade model. Reviewing image sets helped identify equivalent viewing positions from both inspection stages, validating the assessment of similar areas. Photographs from both inspection campaigns were matched using fixed visual reference points such as column numbers, joint locations, bolt configurations, and weld details.

During this alignment process, printed Revit maps of the bridge were used to record the photo locations, which were marked and colour-coded by hand during the first inspection. Approximately 300 photographs were taken during the first campaign, and the image coordinates recorded by the iPhone camera were used to confirm position accuracy. In the second campaign, photographs were taken from the same mapped points using the recorded coordinates and printed reference plan, ensuring that each image corresponded to the same structural element. Minor variations in camera angle were accepted as long as all main reference markers were clearly visible. The photographs were collected to document the various types of corrosion observed. When different colour grades were identified between the two inspections, additional images were taken from the same position to confirm the change. Although 75 elements were assigned new corrosion grades, more than 200 photographs were captured during each campaign to ensure complete coverage and repeatability.

These features enabled consistent alignment between photo pairs taken 14 months apart, ensuring that observed corrosion changes reflected actual surface degradation rather than differences in viewing angle. Additional field notes, including bolt layouts, shadow markings, and paint identification, supported accurate matching of image locations and helped confirm that each photograph corresponded to the same structural element.

4.3. Case Study Application

To demonstrate the application of the suggested corrosion grading system, elements of the steel pedestrian bridge were selected and examined using matched inspection images captured in February 2024 and April 2025. To assess the severity of corrosion, a visual grading system based on ASTM D610 [

31] was used in each case. These illustrations show how corrosion progression was visually evaluated and how the specified severity levels were represented by the colours in the digital representation. This section enables a direct comparison between the two inspection periods by highlighting the most frequent degradation patterns in the elements. The task is to confirm whether the workflow under field conditions is realistic and to demonstrate how the model aids in planning the desired maintenance activities. Although lighting and camera angles varied slightly between inspections, comparison points were carefully selected using fixed visual references. To address uncertainty, confidence levels were assigned based on image clarity and alignment.

In February 2024, the coating was largely intact, with only minor discolouration visible around the welds, as shown in

Figure 11. However, signs of corrosion were already noticeable on the side beam. By April 2025, rust had increased along the weld lines, particularly at the connection between the brace and the column. The surface exhibited visible corrosion, accompanied by early signs of oxidation and localised flaking. These effects were more pronounced at the connection points, which were frequently exposed to rain and likely experienced accelerated deterioration as a result. The beam also exhibited noticeable surface delamination.

This beam section is not located near a connection point but rather along the middle of the span. In February 2024, a rust patch was observed. By April 2025, the patch had darkened and extended over a larger area. The outer surface showed cracking and peeling at the corners, indicating surface degradation. The visibly affected area had increased by approximately 10%. The spread of corrosion at the beam’s centre, rather than near the joints, suggests a likelihood of localised moisture retention. Such mid-span sections should be included in future inspection procedures.

Figure 12 shows the condition of this area.

In February 2024, visible rust was found at the column base. In April 2025, the situation had deteriorated, with more severe discolouration, flaking and greater areas of rust. The corrosion was visible on up to one-third of the surface. Since this joint is a key element in vertical load transfer, progressive damage indicates that specific maintenance is required to prevent further losses.

Figure 13 indicates the status of this element.

In February 2024, this area exhibited only minor rust spots, primarily near the exposed edges. By April 2025, the rust had spread to a broader area, leading to coating loss and visible changes to the metal surface. More than one-third of the area showed active corrosion. Although the adjacent joint remained unaffected, the deterioration of this segment highlights the importance of regularly monitoring exposed structural surfaces. The condition of this part is illustrated in

Figure 14.

At the base of the column, V-shape, early signs of coating peeling and rust streaks were visible in 2024. By the time of the next inspection, rust had spread across the welds and the surrounding steel, with scaling and moss accumulation indicating moisture entrapment. The corrosion had progressed to an advanced stage, affecting a significant portion of the surface and necessitating urgent attention. Its position at a water-collecting junction reinforces the need for preventive drainage measures and protective coating strategies. The condition of this joint is shown in

Figure 15.

5. Results Discussion

The comparison displays some illustrative examples through

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15. The presented images reveal surface alterations that are visible to the human eye. Minor rust marks appeared in the 2025 pictures that were not visible in the 2024 images.

The steel surface exhibited changes in its tone, indicating the onset of coating deterioration. The surface texture in this example appeared rough because moisture may have affected the steel material for an extended period. Minor changes on the surface were documented despite their assigned minor grading status, which indicates corrosion growth in selected areas during the inspection period. The structured approach enables the documentation of modifications in observed corrosion through visual inspections and the identification of these modifications in the BIM models. BIM model updates alongside photographic records enable early and continuous observation of surface deterioration and its time-based evolution. Maintenance planning decisions become more effective when a comprehensive digital record of the bridge’s condition evolution is established through this methodology. The methodology demonstrates a clear value in extensive monitoring activities because it enables the initial identification of potential issues, preventing severe structural damage.

The inspection findings from the image comparisons, as presented in

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, are visually summarised in

Figure 16 and detailed in

Table 4. In each row, the process of surface degradation is visually described, starting from coating failure to rust spread and joint degradation. This filtered summary aims to reinforce the photographic evidence and serve as an auxiliary reference source in identifying the zones where corrosion has escalated significantly. To record the physical position of each case on the bridge (such as between columns or at truss joints) in an easy-to-understand format that allows for the integration of the current status of the steel bridge into the BIM model or completeness inspection, a blank column has also been included.

Table 4 includes confidence levels for each observation, indicating the visual certainty of the severity classification based on image clarity, inspector agreement, and image alignment.

Although

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16 highlight selected cases, the proposed workflow was applied to the entire bridge model, which includes more than 2600 elements. Among these, approximately 75 elements were identified as having visible changes between the February 2024 and April 2025 inspections. These elements were not pre-selected. Instead, they emerged through a systematic review of all modelled components.

Table 5 summarises the number of elements that changed, categorised by their assigned corrosion grade after the second inspection.

Confidence levels were also recorded for each element based on three qualitative criteria: Image clarity, consistency in camera angle between inspections, and the inspector’s confidence in visually identifying corrosion features. This comparison supports the visual evidence and demonstrates how corrosion progression is tracked, scored, and quantified within the BIM environment. Although the dataset included two inspections and seventy-five degraded elements, the sample was considered sufficient to demonstrate the technical feasibility of the proposed method.

6. Conclusions

This article presents the documentation and evaluation of the corrosion condition of a steel pedestrian bridge based on visual inspections, Building Information Modelling (BIM), and structural behaviour monitoring. The field assessments were conducted in February 2024 and April 2025, utilising photographs and condition data to create a Revit-based model of the bridge. Structural elements were colour-coded according to a grading system, enabling visual classification and assessment of corrosion severity.

Figure 7,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 show the entire bridge, the corrosion grading system, and specific points where visual damage could be measured during the 13-month observation period. In brief, a table outlines 13 sites of corrosion acceleration (

Figure 16), which can be referenced in future data and model incorporation.

The Revit model created in the current research is beneficial for visualisation and can serve as the foundation of a digital twin. The model transforms into a dynamic bridge replica when condition data is added, enabling continuous monitoring and centralised storage. The digital twin can incorporate visual records and sensor-based information to provide a comprehensive picture of the bridge’s health over time. The model can be used to identify affected zones, determine intervention directions, and monitor the efficiency of repair actions over time. In future developments, the grading results may be linked to a decision-support framework, where specific corrosion grades can trigger alerts for inspection, repair planning, or budget allocation.

A greater emphasis was placed in this study on surface corrosion, which can be detected by visual inspection. No allowance was made for subsurface damage or fatigue-related degradation. The technique also relies on manual image registration, which can introduce a degree of subjectivity into the inspection. Additional developments can involve incorporating sensor data to achieve automatic detection and extending the digital twin to structural fatigue.

The main contribution of this study is the integration of an adapted visual grading system into a BIM environment via Dynamo scripting, providing a scalable, semi-automated approach to corrosion monitoring.

Whereas the current research may tend to utilise spreadsheets or story inspection reports, the approach provides a structured, visual platform for grading and monitoring corrosion with the assistance of BIM tools. The workflow combines image-based analysis with 3D model colour-mapping to offer a clear connection between asset management planning and field inspection.

This evaluation demonstrates that, even with a limited number of graded examples, integrating visual inspection with BIM-based modelling provides a structured, traceable approach to detect, classify, and monitor corrosion development over time. The approach supports visual consistency and aligns with digital twin strategies for steel infrastructure.

While this study is based on two visual inspections over 13 months, future work may incorporate predictive or statistical modelling to estimate corrosion progression. Approaches such as linear regression, time-series analysis, or machine learning classification could support forecasting of corrosion trends across different bridge zones. This would enhance the model’s ability to anticipate deterioration and optimise maintenance schedules. Although this research was focused on a steel bridge, the same workflow can be adapted to other materials, such as mixed or reinforced concrete structures. In those cases, the visual indicators would include coating loss, reinforcement exposure, or surface discolouration, while the grading and colour system could remain the same. Such adaptation would expand the method’s relevance for broader bridge management applications.