Abstract

Background: Primary ventral hernias (PVHs) are a frequent disease that can impair quality of life. Laparoscopic intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM) technique has shown good outcomes in appropriately selected cases. Methods: We report the results of a retrospective analysis involving 200 consecutive patients who underwent laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with a standardized technique using a single mesh from January 2011 to September 2024 to define the safety of laparoscopy in ventral hernia treatment. Results: The study included 147 umbilical hernias (73%) and 53 epigastric hernias (27%). The average defect measured 3 cm, with sizes ranging from 2 to 7 cm. After a mean follow-up of 1708 days (range 117–4642), no complications associated with the mesh were observed; there was only one (0.5%) recurrence documented and no bulging was observed. Conclusions: Laparoscopic repair of PVH using a standardized technique and using the same mesh, which has been proven safe over the last 15 years, offers good results.

1. Introduction

Primary ventral hernias (PVHs) are a frequently reported disease that can impair quality of life and can lead to severe complications. Ventral hernias (VHs) are classified according to their location. An umbilical hernia is a midline defect located within the lateral edges of the rectus sheaths, extending from 3 cm above to 3 cm below the umbilicus, whereas an epigastric hernia is a midline defect situated from 3 cm below the xiphoid process to 3 cm above the umbilicus. Risk factors for umbilical hernias development include obesity, physical exertion, and pregnancy [1].

It is important to distinguish between hernias that require intervention and those that may not necessitate treatment. There is poor evidence supporting a watchful-waiting strategy for asymptomatic hernias, and current guidelines endorse this management option.

Moreover, umbilical and epigastric hernia repair differs substantially between different gender and age groups: the first is more common in males aged 61–70 years, while the second is prevalent in females aged 41–50 years [2].

Complications of VHs are represented by pain discomfort, negative association with body image, and more severe, bowel incarceration. VH repair is a common procedure, but the best surgical technique is not defined, and the choice is generally related to the surgeon’s experience. Discussions are generally centered on whether to use sutures or a mesh, which type of mesh to choose, and different approaches for mesh placement. There is strong evidence that the use of mesh for open umbilical or epigastric hernia repair reduces the rate of recurrence for large hernia defects; however, data remain insufficient regarding defects smaller than 1 cm. The optimal surgical strategy is still debated, and the optimal level at which the mesh should be positioned is another aspect that has been inadequately explored. The ideal approach depends on patients’ characteristics and must be discussed with them. Several techniques are described, including open, laparoscopic, and robotic procedures, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Randomized and non-randomized studies indicate that laparoscopic repair results in fewer complications and recurrences and reduced hospital stays but typically requires a longer operative time [3,4].

Although PVH repair is considered a straightforward surgical procedure, the optimal treatment strategy is still being debated. Clear distinctions exist between incisional hernias (IHs) and PVHs. Repairing IHs is generally more difficult than repairing PVHs, because these defects tend to be more complex (often larger, located at transitional zones, and presenting with a Swiss-cheese configuration), and adhesions are commonly encountered, which consequently prolong the operative time. Nevertheless, PVHs are rarely investigated as separate entities, and no evidence-based treatments have been reported.

For various reasons, PVHs represent the cases that offer the best results in laparoscopic treatment. Personal experiences and the wide variety of prosthetic materials introduced over time have contributed to the evolution of laparoscopic repair techniques. Laparoscopic repair of umbilical hernias was first described in the 1990s [5]. Laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias has increased in recent years and involves minimally invasive accesses and the possibility of placing the prosthesis under the abdominal fascia without involvement of the hernia sac. This approach decreases operative trauma and offers superior visualization of defects, including small defects that might not be detected during physical examination. As a result, this enables precise positioning of the prosthetic mesh with consistent and adequate fascial overlap. Furthermore, it also helps minimize the risk of bleeding, seroma, and infections. Minimally invasive repair provides multiple benefits due to reduced surgical trauma, as it avoids long incisions, extensive dissections, flap creation, and opening of the hernia sac [5,6,7]. Clinical studies have confirmed the safety of the laparoscopic technique with recurrence rates comparable to open repair and, in addition, is particularly useful in obese patients [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Since 2011, in our institution, 200 patients have undergone laparoscopic abdominal wall repair for PVH using a uniform mesh type and a consistent standardized technique. The objective of this study is to present our outcomes to further characterize the safety profile of the laparoscopic technique in PVH repair.

2. Methods

- Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study on 200 unselected adult patients treated for PVH from January 2011 to September 2024. Before undergoing the procedure, all patients provided written informed consent. The study adheres to STROBE guidelines. The study period began in January 2011, when the standardized technique described in this report was first implemented. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board with protocol number 378-2023-OSS-AUSLIM, ID 6098. All participants gave written informed consent to take part in the study and to allow publication of anonymized data and images.

- Variable measured

In cases of PVH, preoperative computed tomography (CT) is not always performed; it is typically indicated for defects larger than 4 cm or in emergency settings. Hernia width (W) was measured and defined based on the European Hernia Society (EHS) classification, which defines a transverse defect width as W1 (<4 cm), W2 (≥4–10 cm), or W3 (≥10 cm) (9). Evaluation was based solely on clinical evaluation. Data collected during the follow-up included incidences of late complications or mortality, defined as any death occurring within 30 days (immediate/procedure related) or beyond 30 days (late) after surgery. The main variables examined were the defect size, body mass index (BMI), age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, and associated interventions.

No postoperative radiological examinations were performed unless clinically necessary. In the case of a suspected recurrence at clinical examination, abdominal CT scan was performed. The main outcomes examined were post-operative complications, recurrences, and mesh-related complications. Chronic pain was defined as a persistent discomfort lasting beyond 6 months despite medical therapy.

- Intervention

All procedures were carried out by surgeons skilled in laparoscopic IPOM techniques for abdominal wall repair. Operations were conducted under general anesthesia, using a standardized protocol for the key stages of the laparoscopic approach. Antibiotic and antithrombotic prophylaxis were given using Cefazolin and low-weight molecular heparin. Before surgery, pneumoperitoneum induction was performed in curarized patients, and preoperative measurements were made. Pneumoperitoneum was established using a Veress needle inserted in the left hypochondrium, after which an optical trocar was placed in the left flank (5 mm), together with two additional trocars on the left side of the abdomen (10 mm and 5 mm), and a 30° laparoscopic camera. Once the abdominal wall defect was exposed, the hernia sac was isolated, and the defect was measured to select the appropriate mesh. Falciform ligament and preperitoneal fat were removed to facilitate mesh positioning.

The selected mesh (VentralightTM ST mesh, Bard, Davol Inc., Warwick, RI, UK) is a light-weight (51 g/m2) monofilament, microporous polypropylene mesh (pores vary between 300 and 1000 micron) with a 30-day absorbable hydrogel barrier to minimize tissue adhesion to the visceral side of the mesh, which is activated by saline solution. The mesh was inserted using a 10 mm port and applied on the defect by a specific system (Echo PS™ Positioning System Bard, Davol Inc., Warwick, RI, UK) to help its positioning in the intraperitoneal space. The hydrogel side is on the viscera. The mesh was then fixed to the wall with at least 4 cm of overlap in all edges. Generally, absorbable tacks were used for fixation (SorbafixTM, Bard) and, in selected cases, metallic tacks were added (CapsureTM BD). SorbafixTM is a sterile single-use absorbable device made by poly (D,L)-lactide. CapsureTM is a metal sterile single-use permanent fixation device covered with smooth polyetheretherketone cap. ProtackTM Medtronic was not used. The ‘double crown’ technique was routinely ensured [13]. Mesh fixation was performed, reducing pneumoperitoneum to 8–10 mmHg to obtain a tension-free placement. Hemostasis was ensured before removing the trocars; drains were placed only when abdominoplasty was performed concurrently. When abdominoplasty was associated, surgery started after hernia repair and pneumoperitoneum resolution. Preoperative drawings were made before surgery, defining the surgical suprapubic incision and the midline. The umbilicus was mobilized while preserving its pedicle, and a suprapubic incision was created to gain access to the fascial layer. The skin was dissected from the muscle plane until the costal arch, and the abdominal flap was elevated to define the amount of skin to resect. After resection, the umbilicus was repositioned and sutured; drains were positioned accordingly. The nasogastric tube was withdrawn upon completion of the operation. An abdominal binder was applied immediately postoperatively. Oral analgesia was administered regularly, and early mobilization was encouraged. Patients were advised to wear abdominal compressive garments for at least 60 days. Scheduled follow-up visits were performed at 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year after surgery. After the first-year visit, patients were asked to report any problems and, if necessary, book a visit to the clinic.

3. Results

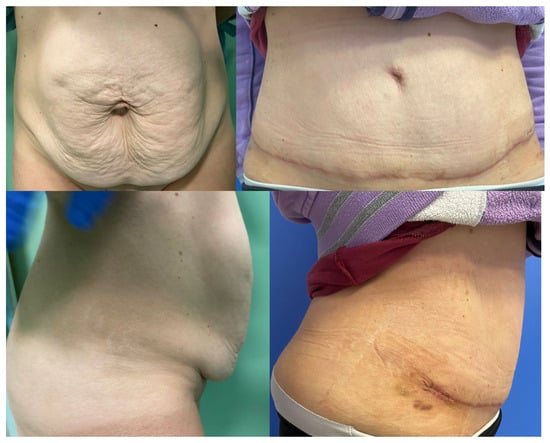

Two hundred consecutive, unselected patients underwent laparoscopic abdominal wall repair for PVH from January 2011 to September 2024. Table 1 summarizes patients’ characteristics. The average age was 54 years (range 19–82); thirty-five patients (17%) were older than 70 years of age. A total of 126 patients were male (64%); the average ASA score was 1.9; the mean BMI was 29.3, and 75 (37%) patients presented with a BMI greater than 30. Mean defect size was 3 cm (range 2–7) in width (W). In this series, classification following the European Hernia Society (EHS) criteria showed 161 (80%) W1 and 39 (20%) W2. Twenty-three patients (11%) had previously undergone open abdominal surgery, and 11 cases (4%) required emergency interventions due to the omentum being trapped inside the hernia. Absorbable fixing devices were employed in 138 patients (69%). In no case was a conversion to open surgery necessary. In 25 (12.5%) cases, further procedures were performed: four cholecystectomies and three abdominoplasties (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Overall, the average operative duration was 71 min (range 30–180), and the mean length of hospitalization was 1.6 days (range 1–3). We had one (0.5%) symptomatic seroma that was drained. No surgical site infections (SSIs) occurred. Only one (0.5%) recurrence and no bulging were found on follow-up. The recurrence was verified through abdominal CT imaging (W2) and occurred 11 months after surgery; the patient declined any further intervention. After a mean follow-up of 1646 days (range 117–4642), no complications attributable to the mesh were observed. Two (1%) cases of chronic pain were recorded. An abdominal CT scan was performed to exclude a recurrence. For these two patients, no surgical procedure was performed, but they were referred to our pain therapy clinic. Two patients died during follow-up due to medical conditions after 2 and 3 years from surgery.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (BMI: Body Mass Index).

Figure 1.

Symptomatic umbilical hernia with associated abdominoplasty.

Figure 2.

Ventral hernia with associated abdominoplasty.

Figure 3.

Ventral hernia with associated abdominoplasty.

4. Discussion

The results shown by this study in the treatment of PVHs proved interesting. We noted an almost complete absence of complications, reduced operating time, absence of conversions, short hospital stays, and very low incidence of recurrence (1 in 200 patients). Hernia recurrence represents a key postoperative endpoint and serves as an indicator of surgical effectiveness. There may be several explanations. First, by definition, patients with PVH have not undergone previous abdominal surgery: this allows for an operating field free of adhesions, thus minimizing the probability of visceral complications. Another factor is that the wall around the defect is a healthy wall: in IPOM, no muscle dissections are performed, while dissections could inevitably weaken the surrounding abdominal wall. Added to this is the fact that the risk of surgical site infections is practically zero, along with all the consequences that this would entail, for example, the risk of recurrence. In this cohort we did not observe any surgical site infections, a finding that we consider particularly noteworthy in the context of hernia repairs. Usually, the defects of primary hernias are small–medium-sized, as it is also verified by analyzing the average defect in our study population (mean defect size 3, range 2–7 cm, Table 1). The role of defect closure during laparoscopic plastic surgery (IPOM plus) has been widely studied [18,19]. We hypothesize that defects of this size (small–medium) and cases of primary hernias are those that benefit most from the IPOM laparoscopic technique. The unique case of recurrence and the absence of bulging have led us to conclude that for defects of this size, defect closure is useless. In the literature, reported recurrence rates vary between 1% and 20% [11], typically manifesting within the first postoperative year [17]. Existing evidence indicates that laparoscopic repair results in significantly fewer recurrences than open procedures for defects under 6 cm [15,16]. Analyzing our data, we only had one recurrence that was probably due to a technical error; we believe that a small prosthesis was chosen in relation to the defect. Obese patients have benefitted from the laparoscopic technique [10,11]; in fact, in our series, 37% of the patients presented with a BMI greater than 30, and no wound-related complications were identified. Cholecystectomy was performed during the intervention in case of symptomatic cholelithiasis. In our series, an important skin excess was present, so we performed a simultaneous abdominoplasty to reduce it (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). The literature reported similar outcomes regardless of fixation techniques [19,20]. Since 2011, we have abandoned the use of the ProtackTM Medtronic, and we have increasingly used a combination fixation method (CapsureTM BD together with SorbafixTM Bard) [11]. Based on these results, we can state that both umbilical and epigastric PVH are well-suited for laparoscopic repair. It remains necessary to determine whether PVH and IH should be regarded as distinct conditions or grouped together to draw accurate conclusions about their management and outcomes. It is worth nothing that, as reported by Stabilini et al. [21], incisional hernias are more challenging to treat compared to PVHs. The authors state that statistical analyses should separate PVH cases from incisional hernias. A major limitation in the current literature on umbilical and epigastric hernias is that many studies merge their outcomes with those of incisional hernias. Because umbilical and epigastric hernias are often approached differently, likely with different outcomes compared with incisional hernias; hence, future studies on umbilical and epigastric hernias should evaluate them separately from incisional hernias. Our results suggest that laparoscopy may be an effective option for these cases; however, comparative research is required to validate these results, and the absence of comparative data highlights the need for future studies.

5. Conclusions

In this analysis, we show very good results in PVH laparoscopic repair using a standardized technique and employing the same mesh (VentralightTM ST Echo PS, Bard, Artarmon, Austrlia). The principal strengths of this study include the large patient cohort, the extended follow-up period, the consistent use of a standardized technique, and the employment of a single mesh type. These conclusions reflect our experience over 15 years of clinical practice.

There are some limitations of the study to consider. Firstly, it is a retrospective study of non-randomized patients. Despite that, the study population was considerably large, and the follow-up was long. On the other hand, the retrospective study design and the lack of a control group limit its statistical robustness. Another limitation is that recurrences were assessed only during clinical evaluation and routine imaging was never performed. All procedures were performed at a single center by highly experienced surgeons, which may reduce the generalizability of the findings.

Well-designed prospective, randomized controlled trials with sufficient statistical power are required to provide more results. Future studies should analyze other important aspects, such as the outcomes related to hernia dimension or the clinical setting, pain after surgery, quality of life, recovery time, and the cost-effectiveness related to the different techniques.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.V. and L.N.; methodology, G.V. and L.N.; writing-review and editing, G.V. and L.N.; supervision, M.M. and R.S.; and validation, M.M. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the AVEC Ethics Committee with the code 378-2023-OSS-AUSLIM, ID 6098 on 6 September 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study and written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sara Nesti for the revision of the language and of the manuscript duplications.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors disclose all relationships or interests that could inappropriately influence or bias their work. The companies Medtronic and Bard had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. Negosanti Luca is empolyed at Montecatone Rehabilitation Institute. Montecatone Rehabilitation Institute had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Haskins, I.N. Hernia Formation: Risk Factors and Biology. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 103, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burcharth, J.; Pedersen, M.S.; Pommergaard, H.C.; Bisgaard, T.; Pedersen, C.B.; Rosenberg, J. The prevalence of umbilical and epigastric hernia repair: A nationwide epidemiologic study. Hernia 2015, 19, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.G.; Mallett, S.; Quinn, L.; Wood, C.P.J.; Boulton, R.W.; Jamshaid, S.; Erotocritou, M.; Gowda, S.; Collier, W.; Plumb, A.A.O.; et al. Identifying predictors of ventral hernia recurrence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJS Open 2021, 5, zraa071, Erratum in BJS Open 2021, 5, zrab047. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zrab047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Misra, M.C.; Bansal, V.K.; Kulkarni, M.P.; Pawar, D.K. Comparison of laparoscopic and open repair of incisional and primary ventral hernia: Results of a prospective randomized study. Surg. Endosc. 2006, 20, 1839–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leblanc, K.A.; Booth, W.V. Laparoscopic repair of incisional abdominal hernias using polytetrafluoroethylene: Preliminary findings. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. 1993, 3, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, K.A.; Booth, W.V.; Whitaker, J.M.; Bellanger, D.E. Laparoscopic incisional and ventral herniorrhaphy in 100 patients. Am. J. Surg. 2000, 180, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heniford, B.T.; Park, A.; Ramshaw, B.J.; Voeller, G. Laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias: Nine years’ experience with 850 consecutive hernias. Ann. Surg. 2003, 238, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, V.; Zhou, H.; Chai, Y.; Cao, C.; Jin, K.; Hu, Z. Laparoscopic versus open incisional and ventral hernia repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. 2014, 38, 2233–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauerland, S.; Walgenbach, M.; Habermalz, B.; Seiler, C.M.; Miserez, M. Laparoscopic versus open surgical techniques for ventral or incisional hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, CD007781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sistema Nazionale Linee Guida—Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Trattamento Laparoscopico del Laparocele ed Ernie Ventrali; ISS: Roma, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cuccurullo, D.; Piccoli, M.; Agresta, F.; Magnone, S.; Corcione, F.; Stancanelli, V.; Melotti, G. Laparoscopic ventral incisional hernia repair: Evidence-based guidelines of the first Italian Consensus Conference. Hernia 2013, 17, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muysoms, F.E.; Miserez, M.; Berrevoet, F.; Campanelli, G.; Champault, G.G.; Chelala, E.; Dietz, U.A.; Eker, H.H.; El Nakadi, I.; Hauters, P.; et al. Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia 2009, 13, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrone, G.; Linguerri, R.; Negosanti, L.; Masetti, M. The role of laparoscopic IPOM in the treatment of abdominal hernias: Lesson learned after 400 surgeries using single mesh. Minerva Surg. 2023, 78, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccoli, M.; Pecchini, F.; Vetrone, G.; Linguerri, R.; Sarro, G.; Rivolta, U.; Elio, A.; Piccirillo, G.; Faillace, G.; Masci, E.; et al. Predictive factors of recurrence for laparoscopic repair of primary and incisional ventral hernias with single mesh from a multicenter study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmi, S.; Millo, P.; Piccoli, M.; Garulli, G.; Nardi, M.J.; Pecchini, F.; Oldani, A.; Pirrera, B. Laparoscopic Treatment of Incisional and Ventral Hernia. JSLS 2021, 25, e2021.00007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, L.J.; Piccoli, M.; Ferrari, C.G.; Cocozza, E.; Cesari, M.; Maida, P.; Iuppa, A.; Pavone, G.; Bencini, L. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: Results of a two thousand patients prospective multicentric database. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 51, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Egea, A.; Carrillo-Alcaraz, A.; Aguayo-Albasini, J.L. Is the outcome of laparoscopic incisional hernia repair affected by size? A prospective study. Am. J. Surg. 2012, 203, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriksen, N.A.; Friis-Andersen, H.; Jorgensen, L.N.; Helgstrand, F. Open versus laparoscopic incisional hernia repair: Nationwide database study. BJS Open 2021, 5, zraa010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Shao, X.; Cheng, T.; Li, J. Laparoscopic intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM) with fascial repair (IPOM-plus) for ventral and incisional hernia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia 2024, 28, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassenaar, E.; Schoenmaeckers, E.; Raymakers, J.; van der Palen, J.; Rakic, S. Mesh-fixation method and pain and quality of life after laparoscopic ventral or incisional hernia repair; a randomized trial of three fixation techniques. Surg. Endosc. 2010, 24, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabilini, C.; Cavallaro, G.; Dolce, P.; Capoccia Giovannini, S.; Corcione, F.; Frascio, M.; Sodo, M.; Merola, G.; Bracale, U. Pooled data analysis of primary ventral (PVH) and incisional hernia (IH) repair is no more acceptable: Results of a systematic review and metanalysis of current literature. Hernia 2019, 23, 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.