Abstract

This study investigates a water–energy investment in the Consorzio di Bonifica della Romagna Occidentale (Northern Italy) over the period 2015–2022, analysing how integrated irrigation and energy infrastructures can support agricultural resilience. In this area, pressurised irrigation systems are increasingly replacing traditional gravity-fed networks, enabling precise water distribution. However, their energy intensity raises operational costs and exposure to volatile electricity prices. To address these challenges, the research evaluates the coupling of pressurised irrigation with floating photovoltaic (PV) systems on irrigation reservoirs. Using plot-level economic data for vineyards and orchards, the analysis shows that, although pressurised systems entail higher costs in terms of Relative Water Cost (RWC) and Economic Water Productivity Ratio (EWPR), integrating them with PV production significantly improves economic performance. The findings show an average reduction in RWC of 1.44% for vineyards and 5.52% for orchards, and an average increase in EWPR of 38.51 units for vineyards and 24.81 units for orchards. This suggests that combining efficient irrigation systems with renewable energy could represent a viable pathway toward more sustainable water management. Policy implications may concern incentives for joint water–energy investments, adjustments to zero-injection rules, and broader reforms in agricultural, energy, and environmental policies.

1. Introduction

To meet the rapidly increasing food demand driven by continuous global population growth, agricultural systems are required to pursue sustainable intensification strategies that ensure adequate food production while simultaneously mitigating water scarcity and reducing contributions to climate change [1]. In this context, agriculture plays a pivotal role, as it accounts for approximately 70% of global freshwater withdrawals and represents a major source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, thereby contributing to climate change through multiple pathways [2,3,4].

In the European context, over the past decades, both the scientific and policy communities have devoted considerable attention to identifying effective measures for improving water-use efficiency in agriculture. Among these, the modernisation of irrigation infrastructure—particularly the replacement of gravity-fed open-air canals with pressurised distribution networks—has been widely recognised as an effective solution for reducing conveyance losses and improving water delivery efficiency. However, despite their technical effectiveness, several studies highlight that the high investment and operating costs associated with pressurised systems represent a significant barrier to adoption, especially for smallholder farms [1,5,6]. Moreover, while pressurised irrigation systems reduce water losses, they typically entail higher electricity consumption compared to gravity-fed systems, raising concerns regarding farm profitability and increased GHG emissions [2,4]. In Italy, irrigation water management is largely entrusted to Local Agencies for Water Management (LAWMs), which collectively distribute approximately 63% of national irrigation water to farms through an extensive network of withdrawal, storage, and distribution infrastructures [7]. This collective governance arrangement represents one of the most advanced forms of Participatory Irrigation Management (PIM) worldwide, enabling farmers to benefit from large-scale infrastructure investments while sharing costs and risks among users [8,9,10,11]. Collective irrigation systems are therefore widely regarded as effective instruments for promoting the sustainable and efficient use of water resources [12,13,14]. Their performance, however, critically depends on coordinated planning and targeted investments along the entire irrigation supply chain, including distribution network modernisation [15,16].

In response to these trade-offs, recent policy frameworks, particularly within the European Union, have increasingly promoted the integration of pressurised irrigation networks with renewable energy sources, notably photovoltaic (PV) systems. Funding instruments such as the Rural Development Programmes of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) explicitly support such investments. A growing share of PV installations adopts floating configurations on irrigation reservoirs, thereby limiting land-use conflicts and enhancing overall system efficiency. These integrated solutions align with the “nexus” approach to resource management, addressing interlinkages among water, energy, food, land use, and climate objectives [2,4,17]. Since 2011, in fact, with the emergence of the Water–Energy–Food (WEF) nexus concept, the need for an interdisciplinary approach to achieve sustainability in the agri-food sector has been clearly recognised. More recent studies have expanded this framework by incorporating the carbon dimension, leading to the Water–Energy–Food–Carbon (WEFC) nexus, which aims to ensure food security while simultaneously reducing environmental pressures. For example, ref. [18] demonstrated that, within a WEFC nexus framework, bioenergy production can be optimised while minimising both costs and carbon emissions in an irrigation district in China. Similarly, ref. [19] showed that nexus-based approaches can increase agricultural production without expanding arable land while reducing freshwater consumption and the use of fossil-fuel-based electricity in Europe.

Concerning irrigation modernisation and renewable energy integration, the literature is growing. However, previous studies have mainly focused on international case studies [20,21], engineering and hydraulic aspects [22,23,24], or environmental [25,26] and agronomic impacts [27,28]. These contributions have provided important insights, including identification of areas with sufficient solar radiation for PV energy, assessment of farmers’ acceptance and satisfaction, optimisation of panel–sensor configurations for precision irrigation, and life cycle and agronomic assessments of photovoltaic installations, mostly with agrivoltaic configurations.

However, in the context of public funding allocation governed by agricultural policies, a comprehensive evaluation also requires an explicit analysis of the economic outcomes experienced by farmers. Empirical evidence on how different irrigation delivery modalities and water–energy investments affect farm-level economic outcomes and economic water productivity is still scarce, especially in the Italian context. This gap constrains the ability to assess the actual economic viability and distributional effects of such investments under real-world operating conditions.

Against this background, the present study aims to contribute to the existing literature by providing an empirical case study assessment of the economic implications of irrigation modernisation and photovoltaic-powered pressurised systems for farmers in Northern Italy. The analysis focuses on the Buche Gattelli irrigation system, managed by the Consorzio di Bonifica della Romagna Occidentale (CBRO), and addresses the following research questions:

(i) To what extent do economic outcomes differ between farms supplied by pressurised irrigation networks and those relying on gravity-fed systems?

(ii) To what extent do water–energy investments, specifically photovoltaic-powered pressurised irrigation networks, affect farm economic outcomes compared to conventional pressurised systems?

To address these research questions, the study adopts a quantitative analytical framework based on the estimation of farm-level economic performance indices. Specifically, water economic productivity and water-related cost efficiency are calculated for each farm within the study area, allowing a comparative assessment of economic outcomes before and after the implementation of irrigation modernisation and photovoltaic-powered pressurised systems.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides a detailed description of the study area and the Buche Gattelli irrigation system. Section 3 outlines the materials and methods used, including the datasets employed, their sources, and the analytical procedures applied. Section 4 presents and discusses the results, while Section 5 and Section 6 conclude by summarising the main findings and outlining their broader implications for irrigation modernisation and water–energy investment policies.

2. Study Area

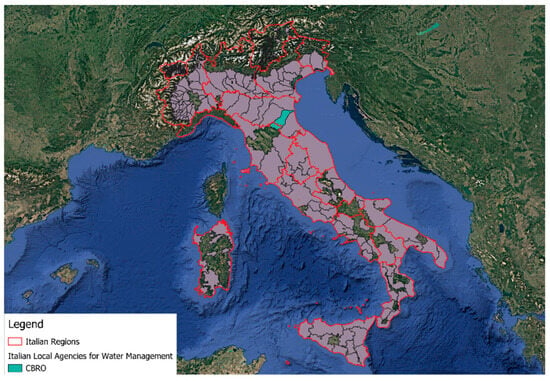

This research focuses on the Buche Gattelli plant, located in the plain area of the Consorzio di Bonifica della Romagna Occidentale (CBRO), which extends over 200,000 hectares between Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna, as shown in Figure 1. Since most of the territory lies in Emilia-Romagna, national legislation and the regional legislation of Emilia-Romagna on land reclamation apply (Regional Council Resolution No. 2151/1988).

Figure 1.

Italian Local Agencies for Water Management and Consorzio di Bonifica della Romagna Occidentale (CBRO). SOURCE: Our elaborations on ISTAT and SIGRIAN data.

The CBRO is historically divided into two areas: the hilly-mountain area and the plain. Our study focuses on the plain, where irrigation represents the main activity carried out by the CBRO to support agricultural productivity. The primary water source here is the Canale Emiliano Romagnolo (C.E.R.) [29]. About 30% of the CBRO plain is upstream of the C.E.R., with 70% downstream, and irrigation water is distributed through two systems [30]: (1) gravity-fed canals for combined irrigation and drainage, feasible only downstream of the C.E.R.; (2) pressurised pipelines fed by pumping stations, developed upstream where elevation requires pressure boosting and where agriculture is highly water-demanding.

According to [30], route losses are significantly higher in gravity-fed canals, a critical issue in the debate on water scarcity exacerbated by climate change. Since water availability is close to demand and subject to competition between agricultural, civil, and industrial uses [31,32], avoiding conveyance losses is essential. For this reason, the CBRO has been investing in network efficiency not only upstream of the C.E.R. but also downstream, with the goal of guaranteeing water supply even in drought years.

In 2019, with RDP 2014–2020 funds (Measure 4.3.02 “Irrigation Infrastructures”), the CBRO launched works in the newly established Pero District (Lugo, RA, Italy), converting the area from gravity-fed to pressurised distribution systems. The project involved 48 farms covering 207 hectares, with key crops including grapevine (66 ha), fruit orchards (57 ha), and wheat (37 ha).

A Water–Energy Investment at Buche Gattelli

As part of a larger investment, a floating photovoltaic (PV) system was installed on the “Buche Gattelli” reservoir, used for storage and flood control, resulting in a combined water–energy investment. In this paper, we specifically analyse the PV component, with the assessment of the pre- and post-investment situation referring to the upgrade achieved through the adoption of the floating PV system compared to conventional pressurised networks. The aim is to reduce the energy consumption of the pressurised irrigation network and, consequently, irrigation costs.

In pressurised irrigation systems, the variable component of the LAWM tariff is closely linked both to energy prices and to the operating time of the system, which depends, among other factors, on crop irrigation needs under climate change scenarios [33,34]. Thus, while farmers benefit from the reliability of the water supply provided by pressurised networks, they are also exposed to higher Irrigation Water Service (IWS) costs.

On the environmental side, several implications have been highlighted, particularly in the context of climate change and with reference to floating PV plants [35,36,37]. These include reductions in greenhouse gas emissions [38]; the avoidance of land use for energy purposes, thereby limiting deforestation, habitat conversion and biodiversity loss; and the partial coverage of the water surface, which reduces evaporation and contributes to water resource protection [39]. For example, ref. [40] estimated that reservoir coverage of 20%, 50%, and 70% led to evaporation reductions of 15.3%, 37%, and 55.2%, respectively. In addition, shading limits algal blooms and helps regulate water temperature, supporting water quality in artificial reservoirs used for irrigation [41,42]. Conversely, in natural water bodies, such changes in light and thermal regimes may negatively affect biodiversity and aquatic life [43].

The Buche Gattelli PV system has a capacity of 63.765 kWp (195 modules, 318.05 m2).

Based on its cumulative annual self-consumption (38,318 kWh/year), the FPV system is estimated to avoid 18.16 t CO2/year, together with reductions in SO2 (0.014 t/year), NOx (0.016 t/year), and particulate matter (0.0005 t/year). These estimates were obtained by applying the plant-specific emission factors provided in the technical design report to the volume of electricity produced and self-consumed during the first year of operation. However, according to the CBRO Executive Project Report, regulatory constraints set by DGR 1584/2017, which published the Regional Single Call for Measure 4, operation type 4.03.02 “Irrigation infrastructures”, prevent surplus energy from being fed into the grid. A monitoring device enforces this zero-injection rule, so the plant can only operate under self-consumption, drawing additional power from the national grid when necessary. This regulatory framework reduces both economic and environmental performance, since pumps operate mainly in the morning and evening, when solar output is low, whereas during peak irradiance hours they are often inactive, leaving a significant share of potential PV generation unused. In fact, according to CBRO data, out of an annual consumption of 101,182.55 kWh, the PV system covered 37.8% of the demand (38,317.67 kWh).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

The methods described below rely on data provided by the CBRO concerning the Buche Gattelli photovoltaic plant, complemented by information from two databases managed by CREA-PB: (the National Information System for the Management of Water Resources in Agriculture (SIGRIAN) and the Agricultural Accounting Data Network (FADN). The former serves as the reference national system for monitoring irrigation volumes and is accessible to all public bodies responsible for agricultural water management. The latter is an annual European sample survey that is statistically representative of the population of agricultural farms in each member state and constitutes the only harmonised source of economic data [44,45]. Since no direct information was available on the farms within the Pero District involved in the construction of the Buche Gattelli photovoltaic plant, FADN samples from 2015 to 2022 were used to perform the econometric analyses of this case study.

To construct the two analytical farm groups, the following steps were undertaken:

- Importing SIGRIAN irrigation districts into QGIS.The irrigation districts of the CBRO were loaded into QGIS software (version number 3.34.11). For each district, the SIGRIAN layer includes both the applicable fee and the information on the irrigation distribution method (gravity-fed or pressurised) [45,46].

- Spatial identification of FADN farms.The geographical coordinates of the FADN farms were intersected, for each year, with the SIGRIAN irrigation district’s boundaries. This spatial overlay enabled the assignment of each FADN farm to the distribution modality characteristic.

- Construction of the two analytical groups and computation of economic indicators.Based on the spatial match, two datasets were created: one including all FADN farms located in gravity-fed districts and one including farms located in pressurised districts. The SIGRIAN districts’ fees were assigned to each group. Economic indicators were then computed separately for the two groups using FADN data.

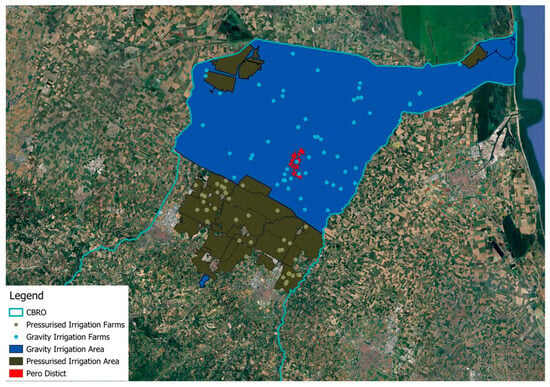

Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of this classification: the area served by gravity-fed distribution is shown in blue, with farms represented by light-blue dots; the area served by pressurised distribution is shown in dark green, with the corresponding farms shown as light-grey dots. The Pero District, highlighted in red, has been entirely included in the pressurised area since 2023, the year in which the system became operational.

Figure 2.

Placement of FADN farms according to the different water distribution methods. SOURCE: Our elaborations on FADN and SIGRIAN data.

The two resulting datasets were subsequently refined by excluding all plots with an irrigated Utilised Agricultural Area (UAA) equal to zero, to focus solely on those effectively engaged in irrigation. To facilitate the analysis of the area’s complex cropping pattern, individual crops were grouped into homogeneous categories, as reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crop categories used.

Using specific indices described in the following section, a preliminary assessment was conducted to evaluate the economic effects of improvements to the irrigation distribution network. Subsequently, to estimate the additional economic impacts associated with the adoption of clean energy systems, the economic results of farms served by the pressurised distribution network (shown in dark green in Figure 2) were recalculated by applying a revised LAWM fee. This fee was based on real data from the Buche Gattelli photovoltaic plant provided by the CBRO. This revised fee was derived using an avoided average cost value computed from real operational data of the Buche Gattelli photovoltaic plant, as provided directly by the CBRO.

For clarity, it is important to specify that the operational scope of LAWMs concerns water abstraction, regulation, and distribution from the source to the farm gate. While the volume of irrigation water ultimately applied at field level may be influenced by a range of on-farm factors—such as soil characteristics, crop composition, management practices, and in-farm distribution efficiency—these elements lie outside the analytical scope of the present study. The analysis is deliberately confined to the off-farm segment of the irrigation supply chain. All processes occurring beyond the farm gate are therefore excluded by design. Within this boundary, the study assesses how farms’ economic outcomes vary ceteris paribus [47], isolating the contribution of water–energy investments implemented within the LAMW-managed distribution network and identifying their specific effects on the economic performance associated with different irrigation delivery modalities.

3.2. Irrigation Cost-Effectiveness Indices

For each irrigated plot, FADN and SIGRIAN data were processed for the two farm groups to calculate two main indices: Relative Water Cost (RWC) and Economic Water Productivity Ratio (EWPR) values.

Intermediate calculation phases led to the definition of several contextual indices useful for a more accurate characterisation of the study area, based on the related economic FADN variables, all expressed per hectare and normalised using the UAA of each plot as reported in the FADN database itself. They include the following:

- Average Crop Yield (ACY) (kg/ha);

- Average Variable Cost (AVC) (EUR/ha);

- Average Gross Margin (AGM) (EUR/ha).

Average Water Utilisation (AWU) (m3/ha): As previously mentioned, the fee values reported in the SIGRIAN layer for each irrigation district were used to derive the Average Economic Water Expenditure (EWEXP) per hectare (EUR/ha), which is required for the computation of both RWC and EWPR. This value corresponds to the annual LAWM tariffs officially reported in SIGRIAN and includes a fixed component (FC), paid per irrigable hectare regardless of actual water use, mainly covering fixed costs, and a variable component (VC), expressed in EUR per cubic metre of water effectively used per hectare, reflecting operating costs such as electricity. The total annual fee is thus given by

where

EWEXP = FC + V × VC

- EWEXP = annual LAWM fee per farm (EUR/ha);

- FC = fixed component, paid by the farms per irrigable hectare (EUR/ha);

- V = volume used per hectare (m3/ha);

- VC = variable component paid by farms per m3 of water effectively used (EUR/m3).

To determine annual EWEXP values, the average of the CBRO district tariffs was used separately for gravity-fed (blue area in Figure 2) and pressurised (dark green area) systems. For districts with gravity water distribution, the variable component was already expressed in EUR/ha, whereas for those with pressure irrigation, it was provided in EUR/m3. Multiplying this value by the AWU of each FADN plot allowed conversion to a per-hectare amount.

The economic performance of farms operating under gravity irrigation distribution and those with irrigation distribution through a pressurised network—initially traditional and later integrated with photovoltaic energy—was then assessed using two indices:

- Relative Water Cost (RWC) (%);

- Economic Water Productivity Ratio (EWPR).

The Relative Water Cost (RWC) estimates the share of the Irrigation Water Service (IWS) cost in relation to the total farm variable costs [46,48] and is calculated as

where

RWC = (AWEXP/AVC) × 100

AWEXP = Average Economic Water Expenditure (EWEXP) per hectare (EUR/ha);

AVC = Average Variable Costs (AVC) (EUR/ha).

The Economic Water Productivity Ratio (EWPR) is a dimensionless index that measures the economic efficiency of water use, calculated as the ratio between the economic value of the yield of a specific crop and the associated irrigation costs [49,50].

where

EWPR = (AGM/EWEXP)

AGM = Average Gross Margin (AGM) (EUR/ha);

AWEXP = Average Economic Water Expenditure (EWEXP) per hectare (EUR/ha).

In this study, the numerator was expressed in terms of the gross margin for the crop under consideration, rather than physical yield per hectare. In fact, the economics of production was considered when expressing both the numerator and the denominator in monetary terms [49,50].

High EWPR values indicate a strong economic return on irrigation, while values below one suggest losses [51]. Maximising EWPR is thus a key objective for farms.

The use of the index enables comparison of the effects of current water cost with those under alternative scenarios, [50] such as those achievable through targeted investments.

In the context of agricultural policy analysis, indices that estimate farmers’ economic capacity to cover irrigation infrastructure costs—as well as the productivity of the water use, particularly for the main crops in each territory—play a crucial role. They support the precise identification of areas requiring intervention and the selection of the most suitable types of investment, thereby promoting the sustainable and efficient use of both economic and water resources [52].

3.3. Specification of the Variable Component Reduction Model

Data provided by the CBRO include the following variables:

- Savings coefficient (EUR/MWh produced);

- Monthly consumption of the plant (MWh/month);

- Monthly withdrawal from the plant’s grid (MWh/month);

- Monthly self-production (SP) of the plant (MWh/month);

- Percentage of self-sufficiency (percentage of self-sufficiency of the plant from an energy point of view);

- Volume handled by the irrigation system (m3/month);

- Investment cost.

These data, covering the period from August 2023 to July 2024 (the first operational year of the Buche Gattelli photovoltaic plant), were used to recalculate the variable component (VC) of the LAWM water tariff, since the investment directly affected the energy-related portion of the fee.

In addition to the above variables, and following the CBRO’s instructions, the values of the single national price of electricity were obtained from the Energy Markets Operator (GME) (https://www.mercatoelettrico.org/it-it/Home/Esiti/Elettricita/MGP/Esiti/PUN, accessed on 14 January 2026) website for the same months.

The Average Avoided Cost (AAC) per unit of distributed water (EUR/m3) was then estimated according to the following formula:

where

AAC = [(Rsv × SP) + (PUN × 1.1 × SP)]/V

- AAC = Average Avoided Cost per unit of water distributed per month in EUR/m3.

- Rsv = reduction in monthly variable costs in the bill for each self-produced MWh (EUR/MWh). According to an analysis conducted by the C.E.A. (https://www.ceaconsorzioenergiaacque.it/, accessed on 14 January 2026) (Consorzio Energia Acqua) on the consumption of the Buche Gattelli plant, each self-produced MWh leads to a saving of approximately EUR 80 in variable energy costs (information provided by CBRO).

- SP = self-produced MWh per month (MWh/month).

- PUN = single national monthly price for the energy raw material (EUR/MWh).

- V = monthly water volume handled by the irrigation system (m3).

To account for the systematic difference between the wholesale electricity price and the effective unit cost paid by the CBRO, an adjustment factor of 1.1 was applied to the raw energy component. Electricity is procured by the CBRO through the national C.E.A. framework agreement (C.E.A.—Consorzio Energia Acque > Il Consorzio > Attivita’ e Servizi, https://www.ceaconsorzioenergiaacque.it/servizi, accessed on 14 January 2026), in which the selected trader applies a procurement spread in addition to the wholesale price. Consequently, the effective purchase cost includes the wholesale component, the trader’s spread, conventional grid losses, pass-through charges, and VAT— the latter representing a real cost for LAWMs. The coefficient of 1.1 therefore reflects the empirically observed ratio between the invoiced unit cost and the wholesale energy component over the reference period, computed ex post from the CBRO’s procurement data. As such, it functions as a synthetic correction factor allowing the avoided cost calculation to approximate the true economic value of the self-consumed photovoltaic energy. Future applications should recalibrate this parameter using locally observed procurement data to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility.

Equation (4) allowed the calculation of monthly avoided cost values within the VC. By averaging these monthly values, an annual Average Avoided Cost was obtained and applied to adjust the 2015–2022 VC values of farms served by pressurised irrigation network. Using the recalculated tariffs, new values of EWEXP, and consequently of RWC and EWPR, were computed.

This made it possible to analyse (i) how the relative weight of the water costs changed within total variable costs at the crop-category level and (ii) how the economic performance (operating margin) varied across crop categories following a change in the IWS cost due to renewable energy investment.

Finally, all monetary flows used in the model and the related indices were updated to 2024, the year when the Buche Gattelli irrigation system became fully operational. The present value of the monetary flows was calculated using a 4% discount rate. This rate was selected in accordance with [53] for the 2014–2020 programming period, during which the Buche Gattelli plant was financed and built, and in line with [54] for the 2021–2027 period, when the plant entered into operation.

4. Results

Table 2 reports the interannual evolution of climatic variables for the April–November period, together with the AWC values of the analysed crops. As shown, in the CBRO area, the average annual temperatures show a slight upward trend, with the warmest years occurring in 2018 and 2022, while cumulative precipitation displays pronounced interannual variability, with notably dry years such as 2017, 2020, and 2021, and wetter years like 2019. These climatic patterns, however, do not translate into a proportional response in AWU: drier or hotter years do not systematically correspond to higher water applications, as AWU is probably influenced mainly by farm-level management decisions. However, a clear structural pattern emerges across all years: farms supplied by pressurised distribution networks consistently exhibit higher AWU values than those served by gravity-fed systems, with particularly pronounced differences for orchards.

Table 2.

Meteorological variables and AWU during the study period in the CBRO area.

4.1. Data Analysis and Comparison Between Water Distribution Systems

Table 3 summarises the characteristics of the two datasets derived from intersecting the SIGRIAN shapefile with the FADN sample. The difference in sample size between the gravity-fed and pressurised systems mirrors the actual distribution of irrigation types within the FADN data for the study area, as the dataset was used in its entirety without any filtering or restriction. As FADN constitutes the only harmonised source providing comparable plot-level economic information at the national scale, all available observations were retained for both irrigation systems.

Table 3.

Detail of the datasets referring to the two different water distribution methods.

To ensure a consistent temporal comparison between the gravity-fed and pressurised irrigation areas, both before and after the implementation of the investment, the analysis focused on orchards (including minor fruit species) and vineyards. This choice was made because these crops were cultivated in both areas from 2015 to 2022 according to the FADN sample, and because they represent the main crops within the Pero District. FADN data show an average of 50 hectares of vineyards irrigated by gravity and 41 hectares irrigated through pressurised distribution. For orchards, an average of 131 hectares was recorded in the gravity-fed area and 65 hectares in the area served by pressurised pipeline networks.

4.2. Impact of the Photovoltaic System on Variable Rate

The application of Formula (4) allowed for the estimation of Average Avoided Cost, resulting in a variable amount of EUR 0.083 per cubic metre. This made it possible to calculate the post-investment variable component (VC) of EWEXP, as reported in Table 4. The terms pre-investment and post-investment refer to the condition of a pressurised irrigation distribution network before and after its upgrade through the installation of photovoltaic systems designed to partially meet the system’s energy needs.

Table 4.

Pre- and post-investment variable component, calculated by estimating the avoided cost.

Based on the data reported in Table 4, updated to 2024, it can be observed that the Average Avoided Cost value represents a substantial portion of the VC for the years under consideration, accounting for a percentage ranging from over 29% in 2022 to more than 50% in 2015.

4.3. Evaluation of Economic Indices

4.3.1. Pre- and Post-Investment Scenario—Vineyards

Relative Water Cost

The first index analysed, described in Table 5, is the RWC.

Table 5.

Pre- and post-investment RWC values for vineyards. St. dev (in parenthesis) and t-test results.

Table 5 reports, for each year, the RWC values of gravity-fed farms and pressurised farms, and the difference between the two (P–G). When this difference is negative, pressurised farms show lower RWC values than gravity-fed farms and therefore a lower incidence of IWC.

The second part of the table reports the post-investment RWC of pressurised farms, the change in the index after the investment (Δ), and the new difference between pressurised and gravity-fed farms.

In the pre-investment scenario, the incidence of irrigation costs (RWC) appears higher in farms supplied by a gravity-fed network, particularly in between 2015 and 2017. However, this higher cost incidence does not appear to be justified by a greater water input per unit area. In fact, water consumption per irrigated hectare (AWU) was consistently lower in gravity-fed farms than in those supplied by a pressurised network, as shown in Table 2. It should be noted that the comparison shown in Table 5 refers exclusively to the segment managed by the LAWMS (i.e., from the water source to the farm gate). The efficiency considered here lies in the reduced conveyance losses along this distribution path. Farms supplied by pressurised networks may still rely on gravity systems within their boundaries or operate on soils with higher water requirements (e.g., sandy soils with greater percolation). There may therefore be various reasons why farms served by pressurised networks appear to use more water, but these factors fall outside the scope of this analysis, which does not investigate on-farm irrigation efficiency.

Starting in 2018, the pre-investment RWC trend reversed: the relative costs incurred by farms using pressurised networks became higher than those observed in gravity-fed farms. Once again, this shift does not seem to be linked to the amount of water used, as the AWU trend remained nearly stable. The divergence in RWC trends arises from opposite component dynamics: in gravity-fed farms, the marked increase in variable costs enlarges the denominator and depresses the index, whereas in pressurised farms the sharper rise in water expenditure inflates the numerator, driving RWC upwards.

In this setting, the t-test results show that there are no statistically significant differences between the two farm groups in any of the analysed years.

The intervention on the pressurised network through the installation of photovoltaic systems results in a negative percentage variation in the index, thereby reducing the incidence of water costs. During the 2015–2017 period, when RWC values for farms connected to the pressurised network were already lower, the investment further widened the gap in index values compared with farms supplied by the gravity-fed network.

In 2018, 2019, and 2022, the observed ΔP leads to a reversal of the situation: after the investment, pressurised farms show a lower incidence of water costs than the control group. In 2021, although pressurised farms still display higher water cost incidence, the gap between the two groups is reduced, with an index contraction of 1.8%.

Post-investment RWC values make the two farm groups statistically different in 2015, 2016, and 2017.

Economic Water Productivity Ratio

Similarly to the results reported for RWC, Table 6 shows, for each year, the EWPR values of gravity-fed farms and pressurised farms and the difference between the two (P–G). When this difference is negative, pressurised farms show lower EWPR values than gravity-fed farms and therefore lower water productivity.

Table 6.

Pre- and post-investment EWPR values for vineyards. St. dev (in parenthesis) and t-test results.

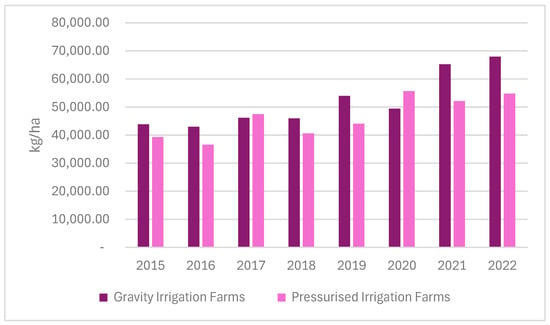

The second part of the table reports the post-investment EWPR of pressurised farms, the change in the index after the investment (Δ), and the new difference between pressurised and gravity-fed farms. Moreover, Figure 3 reports vineyard yields for both farm groups and can be used as an auxiliary tool to interpret the fluctuations in EWPR.

Figure 3.

Average Crop Yield values for vineyards.

Before the investment, farms connected to the pressurised network exhibit higher economic water productivity up to 2017; thereafter, with the exception of 2020, the trend appears to reverse.

The higher water productivity observed for farms served by the pressurised network during the first three years does not seem to be explained by higher yields per hectare (Table 6). In fact, in 2015 and 2016, ACY was even lower for this group. In 2020, however, the higher EWPR achieved by the beneficiary farms compared to the control farms may be attributed to an increase in the numerator of the index (i.e., gross operating margin per unit area), rather than to a reduction in the denominator (IWS costs per unit area), given the higher yields recorded in that year.

The investment results in a positive variation in the EWPR (ΔP column in Table 6), thereby increasing water productivity. These increases allowed these farms to maintain higher economic water productivity than the control group up to 2020. In 2021 and 2022, EWPR values for pressurised-network farms remained lower; however, the investment allowed them to reduce the gap with the control group.

The reported values are not statistically significant in either the pre- or post-investment scenario.

4.3.2. Pre- and Post-Investment Scenario for Orchards and Minor Fruits

Relative Water Cost

As above, Table 7 reports, for each year, the RWC values of gravity-fed farms and pressurised farms, the difference between the two (P–G) (when negative, pressurised farms show lower RWC values than gravity-fed farms and therefore a lower incidence of IWC), the post-investment RWC of pressurised farms, the change in the index after the investment (Δ), and the new difference between pressurised and gravity-fed farms.

Table 7.

Pre- and post-investment RWC values for orchards. St. dev (in parenthesis) and t-test results.

Unlike vineyards, gravity-fed farms show lower RWC values than pressurised-network farms throughout most of the period, although the t-test results do not indicate statistically significant differences. However, the differences remain substantial. Pressurised farms consistently display much higher RWC values than the control group, reaching a peak in 2022, when gravity-fed farms show an RWC of 4.28% compared with 34.29% for pressurised farms. By construction, part of this difference in the index may also reflect a marked contraction in variable costs for pressurised-network farms. However, according to [55], the sharp increase in electricity prices in 2022 likely played a decisive role, pushing total energy expenditures for the LAWMs above EUR 423 million, compared with around EUR 75 million in 2021.

Moreover, analysis of AWU in Table 2 indicates that the higher RWC observed in 2022 for pressurised-network farms cannot be explained by water input quantity. In fact, in that year pressurised-network farms also used less water than gravity-fed farms.

The integration of pressurised irrigation networks with photovoltaic systems led to important economic improvements. In fact, for farms supplied by a pressurised network, RWC values were reduced, showing a negative delta, as indicated in ΔP column (Table 7). The strongest effect occurred in 2015, when the incidence of costs fell by 10.88%. As a result, pressurised farms reached values very close to the control group, even though their water use was higher. In 2022, however, a percentage reduction of 8.2% was still not sufficient to match the levels achieved under gravity-fed distribution systems.

Even after the investment, the two groups remained statistically indistinguishable according to the t-test results, except in 2017. In that year, with a ΔP in RWC of −2.28, the difference between the two groups is statistically significant.

Economic Water Productivity Ratio

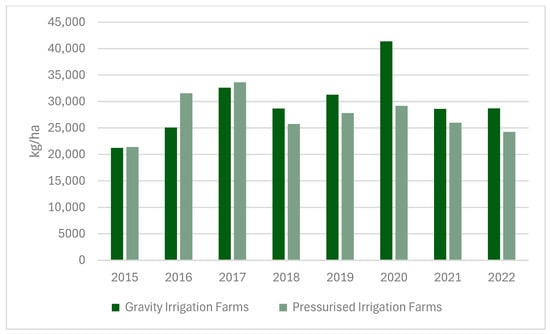

Finally, Table 8 shows, for each year, the EWPR values of gravity-fed farms and pressurised farms, the difference between the two (P–G) (when this difference is negative, pressurised farms show lower EWPR values than gravity-fed farms and therefore lower water productivity), the post-investment EWPR of pressurised farms, the change in the index after the investment (Δ), and the new difference between pressurised and gravity-fed farms. In addition, Figure 4 reports orchard yields for both farm groups and can be used as an auxiliary tool to interpret the fluctuations in EWPR.

Table 8.

Pre- and post-investment EWPR values for orchards. St. dev (in parenthesis) and t-test results.

Figure 4.

Average Crop Yield values for orchards.

Similarly to what was observed for vineyards, EWPR exhibits a generally opposite trend to RWC. For orchards, therefore, the economic productivity of water is consistently higher for farms served by gravity-fed distribution networks. It should be recalled that the EWPR index, defined as the ratio between the gross margin of a crop and the costs incurred for irrigation water, can vary not only in relation to water costs but also as a function of yield per hectare. Higher yields, given constant water costs, increase the gross margin and positively affect the index value. For example, 2020 exhibits the most marked difference in yield per hectare between the two groups, with control farms achieving the highest values and beneficiary farms the lowest (Figure 4. This yield gap likely contributed to the observed differences in EWPR. The same can be seen in 2016, when pressurised-network farms—despite having more than double the RWC of gravity-fed farms—still achieve higher economic water productivity, probably also because of their yields.

Despite the lack of statistical significance in both the pre- and post-investment scenarios, an efficient pressurised irrigation network integrated with renewable energy production results in a markedly different framework. EWPR increases by a positive delta, with values reported in the ΔP column (Table 8. For farms using pressurised networks, the economic productivity of irrigation water rises, even surpassing control farms’ values up to 2019. After this period, despite significant positive deltas, the beneficiary farms remain at a disadvantage in terms of water economic productivity for orchards. The gap becomes particularly pronounced in 2020, possibly due to differences in yields between the two farm groups studied as previously explained.

5. Discussion

The analysis showed that water–energy investments integrating floating photovoltaic systems into irrigation management can enhance economic performance. This improvement, measured through the Relative Water Cost (RWC) and the Economic Water Productivity Ratio (EWPR), derives from the partial replacement of conventional energy sources with renewable generation.

In fact, according to our results, IWS costs associated with pressurised networks may account for up to 2,16% (vineyards, 2021) or 30,01% (orchards, 2022) of the costs observed under traditional gravity systems. The difference between the two groups, in terms of RWC, appears to widen over time for vineyards and, more markedly, for orchards, although with substantial year-to-year fluctuations. Regarding EWPR, a dimensionless ratio representing the economic return per EUR spent on irrigation water, our findings indicate that in the vineyard scenario the index displays considerable variability, with the largest gap recorded in 2021, when farms served by pressurised networks exhibited an economic return 49.07 ratio points lower than those supplied by gravity-fed systems. For orchards, the greatest difference is observed in 2020, when pressurised farms showed an EWPR 90.41 points lower than the control group. These differences are not only driven by the cost of IWS for farms. By construction, the analysed indicators also vary with fluctuations in total variable costs and average gross margin. However, when all these factors are held constant (ceteris paribus) and only the cost of IWS changes, our study yields particularly informative results.

After the investment, both indicators exhibit systematic shifts—negative deltas for RWC (reflecting reductions in water-related costs) and positive deltas for EWPR (indicating enhanced economic water productivity). In some years, these interannual fluctuations lead to a change in the starting position of the two scenarios, with pressurised farms showing lower RWC values than gravity-fed farms or, conversely, higher EWPR values. The main results can be summarised as follows:

Vineyards:

- RWC: The average reduction in RWC is −1.44%. The largest post-investment decrease occurred in 2021 (−1.8%). The resulting difference in RWC between the two groups was −0.37%, meaning that pressurised farms still display slightly higher RWC than gravity-fed farms, although the gap is substantially minimised.

- EWPR: EWPR increased by an average of 38.51 units. The maximum positive variation was recorded in 2017 (+53.58%). Following the investment, pressurised farms achieved an EWPR level 68.47 units higher than the control group.

Orchards (fruit crops):

- RWC: The average RWC reduction is equal to −5.52% while the largest negative change occurred in 2015 (−10.88%). In this year pressurised farms still showed a slightly higher RWC, though the difference was minimal (0.76 units).

- EWPR: The average increase in terms of EWPR is equal to 24.81, while the maximum positive post-investment shift was observed in 2017 (+34.19 units). As a result, the EWPR of pressurised farms exceeded that of gravity-fed farms by 13.72 units.

Although not all post-investment comparisons reach statistical significance according to the t-test, the direction and magnitude of the changes in RWC and EWPR consistently indicate an improvement for pressurised-network farms. In fact, our results are broadly compatible with previous scientific evidence showing that water–energy investments are consistently profitable in Mediterranean irrigation systems [56], particularly in the case of high-power (40–360 kWp) photovoltaic irrigation systems, for which electricity cost reductions of 53–80% have been reported [2]. Similarly, floating PV installations have achieved a 27% decrease in irrigation-related energy costs [57]. These studies analyse reductions in direct energy expenditures and therefore report higher percentage changes than those observed in our work, where variations are assessed in terms of the RWC and EWPR. Nevertheless, because energy costs constitute an essential component of the RWC numerator and EWPR denominator, reductions in energy expenditures translate into proportional decreases/increase in our indices, fully consistent with our findings.

Moreover, one of the limitations of the Buche Gattelli installation relates to the zero-injection rule, which restricts its degree of energy self-sufficiency. This condition mirrors off-grid photovoltaic irrigation systems discussed in [25], where the inability to export surplus energy results in lower investment’s utilisation rates and higher impacts per unit of energy consumed, compared with on-grid conditions. A potential solution is illustrated by [58], who integrate photovoltaic generation with irrigation scheduling through the SPIM self-regulation algorithm. This system synchronises solar energy availability with crop water requirements, maintaining full water delivery while completely eliminating energy costs.

This study has several limitations. First, the zero-injection regulation restricts the Buche Gattelli plant from exploiting its full energy potential, and the available data lack the temporal resolution needed to quantify the related economic effects. Although the system achieved 37.8% self-consumption and avoided 18.16 t CO2 in its commissioning year, the additional benefits achievable without this constraint could not be assessed. Second, the avoided cost estimation is based on a fixed value (EUR 0.083/m3), reflecting the electricity-price structure and energy balance of the reference period. Keeping this parameter constant ensures comparability across years but does not account for future changes in energy markets or PV production. Third, the FADN sample used is not balanced across irrigation methods, a limitation inherent to the database that may affect representativeness.

Future work should integrate high-frequency operational data, alternative electricity-price scenarios, and more evenly distributed farm samples to improve accuracy and robustness.

6. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence on the economic impacts of integrated water–energy investments in the Italian agricultural sector in a WEFC nexus perspective that enables efficient use of resources to pursue sustainable development [18]. Specifically, it shows that the combination of pressurised collective irrigation systems and photovoltaic energy can enhance the economic productivity of irrigation water systems, revealing RWC reductions and EWPR gains for vineyards and orchards. While these configurations are consistent with sustainability and policy objectives [59], their effectiveness is highly context-specific, being shaped by crop characteristics, local environmental and economic conditions, and regulatory constraints, including the zero-injection rule.

The findings yield several relevant policy implications. First, the irrigation modernisation policies should consider both technological and contextual factors. For efficient allocation of community funds, water–energy investments require context-specific assessments and policy mixes to maximise economic resilience and sustainability [60]. Second, evidence of post-investment improvements in water-related cost efficiency and economic water productivity indicates that targeted public supports are essential. Instruments such as investment subsidies and performance-based incentives can facilitate uptake. Such measures may also reduce financial risks while enhancing water–energy efficiency outcomes. Overall, the results highlight the importance of flexible, context-specific, and coherent policy frameworks capable of effectively supporting integrated water–energy solutions in a context of increasing resource constraints.

Author Contributions

S.G.: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft Preparation. V.M.: Conceptualisation, Validation, Writing—Review and Editing. L.C.: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing—Review and Editing. C.P.: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Review and Editing. M.B.: Methodology, Data Curation. R.Z.: Conceptualisation, Validation, Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

On request, aggregated FADN data at plot level for the indices analysed in the paper will be made available, with a distinction between plots served by gravity-fed systems and those served by pressurised networks.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sheline, C.; Grant, F.; Gelmini, S.; Pratt, S.; Winter, V.A.G. Designing a Predictive Optimal Water and Energy Irrigation (POWEIr) Controller for Solar-Powered Drip Irrigation Systems in Resource-Constrained Contexts. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrêlo, I.B.; Almeida, R.H.; Narvarte, L.; Martinez-Moreno, F.; Carrasco, L.M. Comparative Analysis of the Economic Feasibility of Five Large-Power Photovoltaic Irrigation Systems in the Mediterranean Region. Renew. Energy 2020, 145, 2671–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrao, C.; Strippoli, R.; Lagioia, G.; Huisingh, D. Water Scarcity in Agriculture: An Overview of Causes, Impacts and Approaches for Reducing the Risks. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todde, G.; Murgia, L.; Deligios, P.A.; Hogan, R.; Carrelo, I.; Moreira, M.; Pazzona, A.; Ledda, L.; Narvarte, L. Energy and Environmental Performances of Hybrid Photovoltaic Irrigation Systems in Mediterranean Intensive and Super-Intensive Olive Orchards. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2514–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guno, C.S.; Agaton, C.B. Socio-Economic and Environmental Analyses of Solar Irrigation Systems for Sustainable Agricultural Production. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Zande, G.D.; Amrose, S.; Donlon, E.; Shamshery, P.; Winter, V.A.G. Identifying Opportunities for Irrigation Systems to Meet the Specific Needs of Farmers in East Africa. Water 2023, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrigno, M.; Folino, L.A. Il Futuro in Una Goccia, RRN. 2023. Available online: https://www.pianetapsr.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/2954 (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Arslan, F.; Córcoles Tendero, J.I.; Rodríguez Díaz, J.A.; Zema, D.A. Comparison of Irrigation Management in Water User Associations of Italy, Spain and Turkey Using Benchmarking Techniques. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, A.; Melo, O.; Rodríguez, F.; Peñafiel, B.; Jara-Rojas, R. Governing Water Resource Allocation: Water User Association Characteristics and the Role of the State. Water 2021, 13, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gany, A.H.A.; Sharma, P.; Singh, S. Global Review of Institutional Reforms in the Irrigation Sector for Sustainable Agricultural Water Management, Including Water Users’ Associations. Irrig. Drain. 2019, 68, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Impact of Incentives to Purchase Energy-Efficient Products: Evidence from Chinese Households Based on a Mixed Logit Model. Energy Effic. 2023, 16, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, A.M. Improving On-Farm Water Use Efficiency: Role of Collective Action in Irrigation Management. Water Resour. Econ. 2018, 22, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, T.; Matsuda, H.; Nakatani, T. The Determinants of Collective Action in Irrigation Management Systems: Evidence from Rural Communities in Japan. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 206, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zema, D.A.; Filianoti, P.; D’Agostino, D.; Labate, A.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Nicotra, A.; Zimbone, S.M. Analyzing the Performances of Water User Associations to Increase the Irrigation Sustainability: An Application of Multivariate Statistics to a Case Study in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battikhi, A.M.; Abu-Hammad, A.H. Comparison between the Efficiencies of Surface and Pressurized Irrigation Systems in Jordan. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 1994, 8, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukcangaz, H.; Demirtas, C.; Yazgan, S.; Korukcu, A. Efficient Water Use in Agriculture in Turkey: The Need for Pressurized Irrigation Systems. Water Int. 2007, 32, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blicharska, M.; Smithers, R.J.; Kuchler, M.; Munaretto, S.; van den Heuvel, L.; Teutschbein, C. The Water–Energy–Food–Land–Climate Nexus: Policy Coherence for Sustainable Resource Management in Sweden. Environ. Policy Gov. 2024, 34, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Su, Y.; Huo, L.; Guo, D.; Wu, Y. A Multi-Objective Synergistic Optimization Model Considering the Water-Energy-Food-Carbon Nexus and Bioenergy. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 312, 109431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, F.; Bustamante, M.; Mancuso, G.; Toscano, A.; Zhuang, J.; Zilberman, D.; Liao, W. Exploring a Food-Energy-Water Nexus Solution towards a Sustainable and Resilient Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2026, 225, 108618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Bao, S.; Xu, H.; Qin, T. Feasibility Evaluation of Solar Photovoltaic Pumping Irrigation System Based on Analysis of Dynamic Variation of Groundwater Table. Appl. Energy 2013, 105, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, F.; Tamoor, M.; Miran, S.; Arif, W.; Kiren, T.; Amjad, W.; Hussain, M.I.; Lee, G.-H. The Socio-Economic Impact of Using Photovoltaic (PV) Energy for High-Efficiency Irrigation Systems: A Case Study. Energies 2022, 15, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waleed, A.; Riaz, M.T.; Muneer, M.F.; Ahmad, M.A.; Mughal, A.; Zafar, M.A.; Shakoor, M.M. Solar (PV) Water Irrigation System with Wireless Control. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Symposium on Recent Advances in Electrical Engineering (RAEE), Islamabad, Pakistan, 28–29 August 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, E.E.; Chung, L.L.; Sulaima, M.F.; Bahaman, N.; Abdul Kadir, A.F. Smart Irrigation System with Phovolataic Supply. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2022, 11, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, T.; Saleh, A.; Eid, S.; Salah, M. Rehabilitation of Mauritanian Oasis Using an Optimal Photovoltaic Based Irrigation System. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 199, 111984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérida García, A.; Gallagher, J.; McNabola, A.; Camacho Poyato, E.; Montesinos Barrios, P.; Rodríguez Díaz, J.A. Comparing the Environmental and Economic Impacts of On- or off-Grid Solar Photovoltaics with Traditional Energy Sources for Rural Irrigation Systems. Renew. Energy 2019, 140, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todde, G.; Murgia, L.; Carrelo, I.; Hogan, R.; Pazzona, A.; Ledda, L.; Narvarte, L. Embodied Energy and Environmental Impact of Large-Power Stand-Alone Photovoltaic Irrigation Systems. Energies 2018, 11, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagnano, M.; Fiorentino, N.; Visconti, D.; Baldi, G.M.; Falce, M.; Acutis, M.; Genovese, M.; Di Blasi, M. Effects of a Photovoltaic Plant on Microclimate and Crops’ Growth in a Mediterranean Area. Agronomy 2024, 14, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, V.; Montesano, F.F.; Altieri, G.M.; Bari, G.; Tarasco, E.; Zito, F.; Strazzella, S.; Stellacci, A.M. Microclimatic Parameters, Soil Quality, and Crop Performance of Lettuce, Pepper, and Chili Pepper as Affected by Modified Growing Conditions in a Photovoltaic Plant: A Case Study in the Puglia Region (Italy). Agronomy 2025, 15, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaretto, S.; Battilani, A. Irrigation Water Governance in Practice: The Case of the Canale Emiliano Romagnolo District, Italy. Water Policy 2014, 16, 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consorzio di Bonifica della Romagna Occidentale (CBRO). Piano di Classifica per Il Riparto Degli Oneri Consortili. 2023. Available online: https://www.consiglioregionale.calabria.it/DEL10/197/1%20RELAZIONE.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Gleick, P.H.; Cooley, H. Freshwater Scarcity. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molle, F. Water Scarcity, Prices and Quotas: A Review of Evidence on Irrigation Volumetric Pricing. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2009, 23, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cebollada, C. Water and Energy Consumption after the Modernization of Irrigation in Spain. In Sustainable Development; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2015; pp. 457–465. [Google Scholar]

- Haro-Monteagudo, D.; Palazón, L.; Zoumides, C.; Beguería, S. Optimal Implementation of Climate Change Adaptation Measures to Ensure Long-Term Sustainability on Large Irrigation Systems. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37, 2909–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamins, S.; Williamson, B.; Billing, S.-L.; Yuan, Z.; Collu, M.; Fox, C.; Hobbs, L.; Masden, E.A.; Cottier-Cook, E.J.; Wilson, B. Potential Environmental Impacts of Floating Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exley, G.; Armstrong, A.; Page, T.; Jones, I.D. Floating Photovoltaics Could Mitigate Climate Change Impacts on Water Body Temperature and Stratification. Sol. Energy 2021, 219, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, R.; Boulêtreau, S.; Colas, F.; Azemar, F.; Tudesque, L.; Parthuisot, N.; Favriou, P.; Cucherousset, J. Potential Ecological Impacts of Floating Photovoltaics on Lake Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 188, 113852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reca, J.; Torrente, C.; López-Luque, R.; Martínez, J. Feasibility Analysis of a Standalone Direct Pumping Photovoltaic System for Irrigation in Mediterranean Greenhouses. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouran, H.M.; Padilha Campos Lopes, M.; Nogueira, T.; Alves Castelo Branco, D.; Sheng, Y. Environmental and Technical Impacts of Floating Photovoltaic Plants as an Emerging Clean Energy Technology. iScience 2022, 25, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilha Campos Lopes, M.; de Andrade Neto, S.; Alves Castelo Branco, D.; Vasconcelos de Freitas, M.A.; da Silva Fidelis, N. Water-Energy Nexus: Floating Photovoltaic Systems Promoting Water Security and Energy Generation in the Semiarid Region of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzaniga, R.; Cicu, M.; Rosa-Clot, M.; Rosa-Clot, P.; Tina, G.M.; Ventura, C. Floating Photovoltaic Plants: Performance Analysis and Design Solutions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Yadav, N.; Sudhakar, K. Floating Photovoltaic Power Plant: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidović, V.; Krajačić, G.; Matak, N.; Stunjek, G.; Mimica, M. Review of the Potentials for Implementation of Floating Solar Panels on Lakes and Water Reservoirs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 178, 113237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodini, A.; Liberati, C. Le Aziende Agricole in Italia nel 2021. Risultati Economici e Produttivi, Caratteristiche Strutturali, Aspetti sociali ed Ambientali. Rapporto RICA 2023. Available online: https://www.reterurale.it/downloads/Rapporto_RICA_2023.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Manganiello, V.; Banterle, A.; Canali, G.; Gios, G.; Branca, G.; Galeotti, S.; De Filippis, F.; Zucaro, R. Economic Characterization of Irrigated and Livestock Farms in The Po River Basin District. Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2022, 23, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perelli, C.; Branca, G.; Corbari, C.; Mancini, M. Physical and Economic Water Productivity in Agriculture between Traditional and Water-Saving Irrigation Systems: A Case Study in Southern Italy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, M.J. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data, 2nd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lionboui, H.; Benabdelouahab, T.; Hasib, A.; Elame, F.; Boulli, A. Dynamic Agro-Economic Modeling for Sustainable Water Resources Management in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas. In Handbook of Environmental Materials Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, G.C.; Pereira, L.S. Assessing Economic Impacts of Deficit Irrigation as Related to Water Productivity and Water Costs. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 103, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, M.M.; Sepaskhah, A. Farm Water Management in Different Conditions of Water Availability Using Water Productivity in Doroodzan Irrigation Network for Winter Crops. Eur. Water 2014, 47, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, P.; Pereira, L.S.; Rodrigues, G.C.; Botelho, N.; Torres, M.O. Using the FAO Dual Crop Coefficient Approach to Model Water Use and Productivity of Processing Pea (Pisum sativum L.) as Influenced by Irrigation Strategies. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 189, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabieh, M.; Al-Karablieh, E.; Salman, A.; Al-Qudah, H.; Al-Rimawi, A.; Qtaishat, T. Farmers’ Ability to Pay for Irrigation Water in the Jordan Valley. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2015, 7, 1157–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Guide to Cost-Benefit Analysis of Investment Projects-Economic Appraisal Tool for Cohesion Policy 2014–2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/1153 of the European Parliament and of the Council with Regard to the Specific Selection Criteria and the Details of the Process for Selecting Cross-Border Projects in the Field of Renewable Energy; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IN UN SOLO MESE 80 MILIONI DI EURO DI MAGGIORE SPESA ENERGETICA PER I CONSORZI DI BONIFICA E I CONSUMATORI. I CONTI NON TORNANO PIU’! [In Just One Month, 80 Million Euros of Increased Energy Spending for Land Reclamation Consortia and Consumers. The Numbers No Longer Add Up!]. Available online: https://www.anbi.it/art/articoli/6768-in-un-solo-mese-80-milioni-di-euro-di-maggiore-spesa-energet (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Carrillo-Cobo, M.T.; Camacho-Poyato, E.; Montesinos, P.; Rodríguez Díaz, J.A. Assessing the Potential of Solar Energy in Pressurized Irrigation Networks. The Case of Bembézar MI Irrigation District (Spain). Span. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 12, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ortiz, M.I.; Melgarejo-Moreno, J.; Redondo-Orts, J.A. Economic and Sustainability Assessment of Floating Photovoltaic Systems in Irrigation Ponds: A Case Study from Alicante (Spain). Sustainability 2025, 17, 6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérida García, A.; Fernández García, I.; Camacho Poyato, E.; Montesinos Barrios, P.; Rodríguez Díaz, J.A. Coupling Irrigation Scheduling with Solar Energy Production in a Smart Irrigation Management System. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganiello, V.; Chiappini, S.; Galeotti, S.; Tarricone, L.; Pergamo, R. Sustainable Water Management in Viticulture under Climate Stress: Irrigation Requirements and Potential of Controlled Water Deficit. Econ. Agro-Aliment./Food Econ. 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, N.; Del Giudice, T.; Sisto, R. Policy Mixes in Rural Areas: A Scoping Literature Review. Riv. Econ. Agrar. 2024, 79, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.