Abstract

While YOLO’s efficiency and accuracy have made it a popular choice for object detection and tracking in real-world applications, models trained on smaller datasets often suffer from intermittent detection failures, where objects remain undetected across multiple consecutive frames, significantly degrading tracking performance in practical scenarios. To address this challenge, we propose PrED (Predictive Enhancement of Detection), a novel framework that enhances object detection and aids in tracking by integrating low-confidence detections with multiple similarity metrics—including Intersection over Union (IoU), spatial distance similarity, and template similarity, and predicts the locations of undetected objects based on a parameter called predictability index. By maintaining object continuity during missed detections, PrED ensures robust tracking performance even when the underlying detection model experiences failures. Extensive evaluations across multiple benchmark datasets demonstrate PrED’s superior performance, achieving over 11% higher DetA with at least 6.9% MOTA improvement in our test scenarios, 17% higher detection accuracy (DetA) and 12.3% higher Multiple Object Tracking Accuracy (MOTA) on the KITTI training dataset, 8% higher DetA and 2.6% higher MOTA on the MOT17 training dataset, compared to ByteTrack, establishing PrED as an effective solution for enhancing tracking robustness in scenarios with suboptimal detection performance.

1. Introduction

The advancement of fast and efficient deep learning algorithms, coupled with increased computational power, has made real-time object detection a reality. State-of-the-art models like R-CNN [1] and YOLO [2] have become foundational tools in this domain, with their capabilities extending to real-time object tracking in video streams. Applications of object detection and tracking are critical in numerous fields, including traffic monitoring and search-and-rescue missions, where simultaneous and accurate detection and tracking are essential. In autonomous vehicles, particularly those operating in off-road environments without predefined paths, object detection and tracking are vital for environmental perception. They enable vehicles to predict obstacles’ trajectories and plan a path to avoid them, maintain formation in vehicle platoons, and ensure safe traversal with situational awareness by keeping key objects within the line of sight. Figure 1 demonstrates the necessity for autonomous vehicles to maintain the line of sight of obstacles.

Figure 1.

Importance of detection and tracking of objects for an autonomous vehicle. Understanding the position and motion of the object in front helps the vehicle in planning trajectories to avoid collision.

In some cases, when the training dataset is not sufficiently large, deep learning models may encounter challenges such as misclassification and missed detections between frames. Since object tracking performance is heavily dependent on object detection [3], missed detection severely limits tracking accuracy. These detection gaps can be mitigated through two primary approaches. The first involves retraining the model using a larger dataset, though acquiring additional data is often challenging or impractical. A more feasible approach is to predict the location of the missing object by leveraging information from previous frames. The Kalman Filter is particularly useful for this purpose, as it employs a Newtonian motion model to estimate an object’s position during detection gaps. However, the Kalman Filter may diverge from the ground truth when an object’s motion becomes irregular—especially when captured by a moving camera, where the relative motion between the camera and objects varies from frame to frame. Therefore, it is essential to implement a validation mechanism to check whether the predicted location of the object has sufficiently high confidence before drawing a bounding box in the frame.

In this study, we propose a framework that utilizes YOLO v8, a model trained on a small dataset that exhibits irregular and low-confidence detection performance, as the primary detector. When detections are missed, the algorithm compensates by utilizing previously discarded low-confidence bounding boxes, an eight-dimensional weighted Kalman Filter, and various similarity metrics to predict object locations based on a predictability score. The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews existing object detection mechanisms and recent efforts to improve them. The methodology underlying the proposed framework is detailed in Section 3, followed by a discussion of its performance in Section 4. Section 5 provides a comprehensive discussion of key findings and implications. Finally, Section 6 presents conclusions and outlines potential directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Traditional machine-learning methods for object detection often rely on feature engineering. Ballard D. Hough [4] introduced General Hough Transform for feature extraction, and Harris Corner detection [5] is proposed to detect objects through corner detection in 2D images. However, these two methods are sensitive to the geometric features of the images, so changes in image size, rotation, and intensity can affect the detection. Lowe [6] proposed SIFT (Scale Invariant Feature Transform) which is a scale and rotation invariant feature extraction method.

With extensive improvement in deep learning, object detection has become faster and more effective, with less dependence on feature engineering. Girshick et al. [1] utilized deep learning in object detection while proposing an R-CNN model. Later, Fast R-CNN [7] and Faster R-CNN [8] were introduced with improved time efficiency over R-CNN. The above approaches are called two-stage approaches, where a scene or extracted features from a scene are divided into multiple regions, and detections are made in those regions. Around the same time, YOLO (You Only Look Once) [2] was proposed as a fast and accurate single-stage method for object detection. YOLO uses a pre-defined set of bounding boxes that look for objects in their regions. Each bounding box can detect only one object. Being a single-stage detector, YOLO is significantly faster than the two-stage models (1000X faster than R-CNN and 100X faster than Fast R-CNN) [9]. As it has been proven as a quick and accurate method, this method has garnered widespread popularity, and various research is being conducted to improve this method. Currently, there are nine versions of this architecture with multiple publications, with the latest version published in 2024 [10,11,12,13]. In this study, we have explored YOLO v8 as it was published in 2023 with considerable resources to work with.

Several approaches exist for multi-object tracking (MOT), including Tracking-by-Detection (TBD), Joint Detection and Tracking, and Detection-based MOT Enhanced by Transformers, all of which represent detection-based tracking mechanisms [3]. TBD employs object detection as its backbone, followed by subsequent data association steps. Early TBD-based MOT algorithms [14,15,16,17,18] relied on different R-CNN architectures as their detectors. Following the publication and widespread adoption of YOLO, researchers increasingly integrated it as the detector within their MOT frameworks. Bathija et al. [19] explored object tracking by combining YOLO v3 with SORT, incorporating Kalman Filters to track objects. Kapania et al. [20] utilized a combination of DeepSORT, YOLOv3, and RetinaNet to track objects from drone footage. Du et al. [21] enhanced the DeepSORT algorithm by replacing the R-CNN detector with YOLO and modifying the feature parameters. Yang et al. [22] presented a Cascaded-Buffered IoU (C-BIoU) tracker to track objects having indistinguishable appearances and irregular motions. Zhang et al. [23] proposed ByteTrack, a Multi-object tracking (MOT) method where they tracked objects by associating almost every detection box instead of only the high score ones. The method achieved a MOTA accuracy of 80.3% (Multi-object tracking accuracy), 77.3% IDF1, and HOTA (higher order tracking accuracy) of 63.1% on the MOT17 dataset, outperforming multiple other tracking algorithms. Aharon et al. [24] proposed Bot-SORT, utilizing similar tracklet association techniques as ByteTrack, but utilizing ResNet50 as the feature extractor, achieving a 2.9% higher IDF1 score than ByteTrack. ByteTrack served as a benchmark for several other studies. Notably, BoostTrack [25] leverages a combination of different similarity metrics to evaluate low-confidence bounding boxes, outperforming ByteTrack by 0.6% in MOTA and 4.5% in IDF1 in the MOT17 dataset.

In parallel to TBD approaches, several researchers have explored Joint Detection and Tracking (JDT) methodologies. Zhang et al. [26] proposed an encoder–decoder structure for detection and Re-Identification. Liu et al. [27] proposed a modification on YOLO v3 for object tracking where a 3D feature extractor is introduced in the backbone of the CNN model to utilize motion models for different object sizes.

However, conventional MOT algorithms are primarily designed to optimize tracking performance rather than enhance detection capabilities. These methods typically rely on high-accuracy backbone detection models or JDT frameworks and focus on maintaining consistent track ID associations across frames. To the best of our knowledge, no existing algorithm has been specifically designed to enhance overall system performance when working with suboptimal detection models. While algorithms such as ByteTrack demonstrate some improvement in detection accuracy and MOTA through low-confidence bounding box matching, these gains are incidental rather than systematic and remain insufficient for robust performance enhancement.

Our study reveal that there is a substantial opportunity for further exploration in systematically improving detection performance for models with suboptimal accuracy. To address this gap, we propose a framework designed to enhance object detection and tracking in scenarios where traditional models face significant limitations. Table 1 demonstrates the fundamental differences among ByteTrack, Bot-SORT, BoostTrack, and PrED (proposed). The details of the proposed algorithm will be explained in the subsequent sections.

Table 1.

Fundamental differences among ByteTrack, Bot-SORT, BoostTrack, and PrED.

3. Methodology

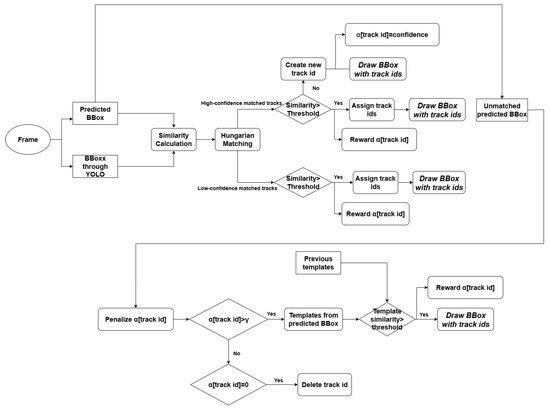

The proposed algorithm implements a TBD framework that leverages YOLOv8 as the primary detector while incorporating a combination of similarity metrics for tracklet matching and undetected bounding box generation. Figure 2 demonstrates the overview of the proposed framework. The flow of our methodology is described below.

Figure 2.

Overview of PrED.

3.1. Implementation of Kalman Filter

To predict the object motion, an 8-dimensional Kalman filter is considered with the object’s position and velocity being the state vectors.

Here, denote the center coordinates, and represent the bounding box width and height at time t for a tracklet.

Considering both sensor noise and measurement noise to be negligible in our system, we selected the values for Q (sensor noise) and R (measurement noise) to be and , respectively, where denotes the identity matrix of p dimensions.

3.2. Similarity Metrics

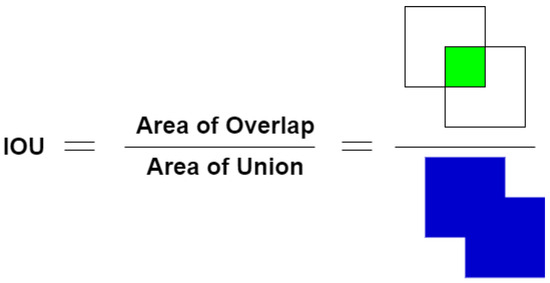

PrED employs three similarity metrics in different proportions based on specific cases: Intersection over Union (IoU) similarity (), distance-based similarity (), and template similarity (). Figure 3 demonstrates the procedure for calculating IoU.

Figure 3.

IOU calculation.

Various distance metrics can be used to measure the difference between predicted and YOLO-detected objects. In this work, we utilize the Mahalanobis distance, which calculates the distance of a detected point from the probability distribution obtained from the Kalman Filter. The Mahalanobis distance is given by

where represents the YOLO-detected object’s location, is the predicted track’s location, and is the covariance matrix of the predicted track. Since objects in the scene move with different velocities, this probabilistic approach provides a more accurate estimate of an object’s subsequent location.

The final similarity metric in PrED is template matching [28]. Template matching involves comparing sections of an image to pre-stored template images. In PrED, cropped images from the bounding boxes are stored as templates associated with specific track IDs. For each frame, YOLO-predicted bounding boxes are used to crop the images, which are then compared with the stored templates. The templates are subsequently updated with the newly cropped images from the tracked bounding boxes. To minimize computational requirements, each template is resized to a standard size of (40 × 40) pixels.

3.3. Algorithm

The PrED algorithm consists of three sequential stages. First, it calculates the similarity metrics between all active tracklets’ predicted boundary boxes and detections generated by the detector. Then, it performs prediction-detection pairing and draws bounding boxes for both high-and-low confidence matched pairs. Simultaneously, new tracklets are created for unmatched high-confidence detections. Finally, the algorithm examines unmatched tracklets and strategically generates bounding boxes where necessary to maintain consistent tracking. The overall algorithm is illustrated in Algorithm 1.

A critical innovation of the PrED algorithm is the introduction of a predictability score (), which serves as a dynamic confidence measure assigned to each detected object. This score operates within a normalized range where with higher values indicating greater tracking reliability. The predictability score is continuously updated through a reward–penalty system based on subsequent detection performance, enabling the algorithm to adapt to object-specific tracking characteristics and environmental variations. The detailed mathematical formulation and update mechanisms for the predictability score are presented in the following sections.

| Algorithm 1 Proposed Algorithm |

|

3.3.1. Deletion of Duplicate Bounding Boxes

First, PrED collects all bounding boxes detected by its YOLO backbone and categorizes them into two groups: high-confidence and low-confidence detections. High-confidence bounding boxes typically provide the most accurate predictions of objects. However, in some cases, multiple high-confidence bounding boxes may be generated for the same object. To address this, PrED calculates the normalized distances between the centroids of detected objects and prunes any bounding box that meets the following criteria: (1) its centroid is very close to an existing detection’s centroid, and (2) it has an iou level of 0.5 or higher with the close existing detection’s centroid. Algorithm 2 demonstrates the process.

| Algorithm 2 Deletion of duplicate bounding box |

|

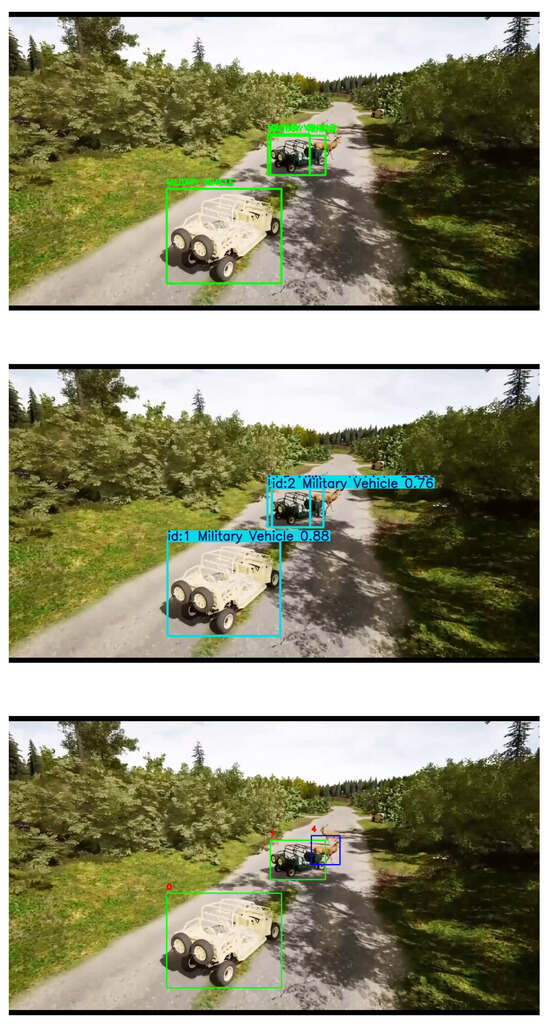

Figure 4 illustrates a scenario where a military vehicle is assigned two high-confidence bounding boxes by the detector.

Figure 4.

Deleting redundant bounding boxes for the same objects by PrED (bottom). Both of the bounding boxes are of high confidence scores, as predicted by base YOLO (top). ByteTrack (middle) also treats both of the bounding boxes as separate detections.

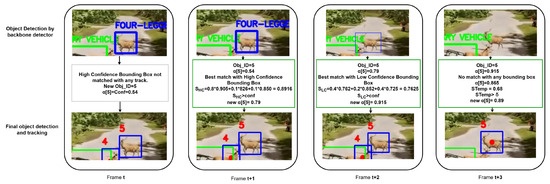

3.3.2. Similarity Calculation

Later, the high-confidence detections and the Kalman-filter predicted tracklet bounding boxes are similarity-matched. The similarity is calculated using the following equation:

Here, and are 0.8, 0.1, and 0.1, which are determined for optimal performance based on observations.

Next, the remaining bounding boxes predicted by the associated Kalman filters, along with low-confidence detections, are considered. For this case, the generalized form of the similarity for track ID i is given by

where,

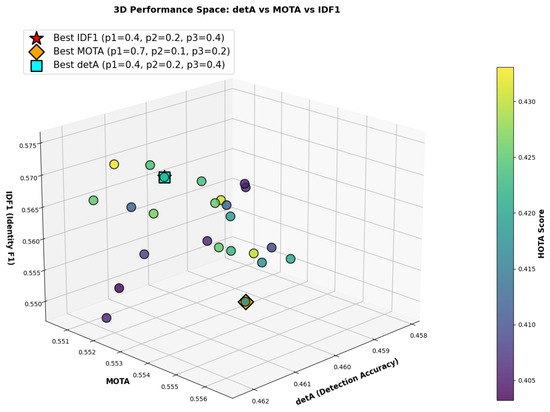

Here, , , and are coefficients that control the contribution of IOU similarity, Distance similarity, and template similarity to the overall similarity metric. Through extensive grid search, we determined that the optimum values for these coefficients are and . Figure 5 illustrates the performance trends of detA, MOTA, and IDF1 across different combinations of , , and values. The results demonstrate that the configuration and , achieves the best performance for two key metrics, detA and IDF1, while maintaining a MOTA score within 0.23% of the optimal value observed.

Figure 5.

Performance trends for different combinations of P1, P2, and P3. The grid search was conducted on the MOT17-13 sequence.

3.3.3. Pair Matching and Drawing Matched Bounding Boxes

Following similarity computation, all detected bounding boxes are matched with predicted tracklets based on their corresponding similarity scores. The Hungarian algorithm is employed to perform the optimal matching operation, ensuring efficient tracklet-detection association. After the matching operation is conducted, both high-confidence and low-confidence matched tracks undergo similarity-based validation. For high-confidence matched tracks, if the matched similarities exceed a predefined threshold, bounding boxes are generated, tracks are updated with their corresponding matched detected bounding boxes, and their values are rewarded with an increment of . Conversely, when high-confidence detections fail the threshold criterion, new tracks are initialized using the threshold-failed high-detection bounding boxes, their respective detection confidence scores are assigned as initial values, and bounding boxes are subsequently drawn.

Similarly, low-confidence matched tracks that successfully pass the threshold validation are updated with their corresponding matched detected bounding boxes, bounding boxes are generated, and their respective scores receive a reward increment of , where the optimum is found 0.125. Here, the optimal and are found following an extensive manual tuning from the possible set . The comprehensive procedure for tracklet-detection pair matching and matched bounding box generation is detailed in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3 Pair Matching and Drawing Matched BBox |

|

3.3.4. Predicting Bounding Boxes on Missing Detections

In this step, the unmatched tracklets’ values initially undergo a penalty of , after which they are evaluated to determine whether the value exceeds the predictability threshold . This condition indicates consistent successful detection and tracking performance over multiple frames, despite the object being absent in the current frame. When this criterion is satisfied, the template region enclosed by the tracklet’s predicted bounding box undergoes similarity comparison against the previous frame’s template from the same track. If the computed similarity exceeds the required threshold, the algorithm determines that the object remains present in the current frame, and a bounding box based on the tracklet’s spatial prediction is generated. Subsequently, the value receives a small reward of . Here, and are set as 0.05 and 0.025, respectively. Conversely, if the tracklet’s value reaches zero, indicating complete loss of predictability, the respective track is deleted from the active tracking set. Algorithm 4 provides a detailed illustration of the missing object prediction methodology.

An essential component of our proposed algorithm is the memory decay mechanism for forgotten objects. The predictability index, , is designed such that only tracks with a sufficiently high predictability score are able to project bounding boxes, minimizing the occurrence of false positive detections. However, when falls below the threshold, the tracking predictor is not immediately deleted. Instead, the track is preserved, and is incrementally reduced over time. This approach allows the track to be matched with future detections before reaches zero, enabling the retention of an undetected track across multiple frames. If the track is successfully matched before reaches zero, its predictability score is rewarded, pushing it back above the threshold and preserving its track history. The value of is constrained between 0 and 1, and once for a track reaches zero, the track is deleted. This memory decay mechanism ensures that the algorithm retains track history and can continue to detect tracks even in the presence of detection interruptions by YOLO.

| Algorithm 4 Predicting Missing Objects |

|

3.4. Testing Environment

The proposed algorithm undergoes comprehensive evaluation across multiple testing scenarios to validate its performance under diverse conditions. Initially, the algorithm is evaluated using a custom test environment developed in Unreal Engine, specifically designed to simulate realistic platoon movement scenarios with controlled parameters. Subsequently, the algorithm is assessed using established benchmark datasets, including KITTI [29] and MOT17 [30,31,32] training datasets. We utilize training datasets rather than test sets for two key reasons: first, test datasets lack ground-truth track IDs necessary for tracking performance evaluation, and second, our algorithm specifically targets enhancement of suboptimal detection models—a scenario that training datasets effectively simulate through their inherent detection challenges. This evaluation approach provides comprehensive performance analysis while ensuring access to complete ground-truth annotations required for accurate assessment of both detection and tracking improvements.

3.5. Performance Metrics

To assess the performance of the proposed framework, four distinct metrics are considered—Detection Accuracy (detA), Multiple Object Tracking Precision (MOTP), and Multiple Object Tracking Accuracy (MOTA), and IDF1 [33,34].

Detection Accuracy measures how well a tracking algorithm predicts an object location in each frame, typically utilizing IOU thresholds. For a sequence of frames, if the algorithm yields True Positive TP, False Positive FP, and False Negative FN, detA can be computed as

MOTP quantifies the average spatial misalignment between the correctly detected objects (true positives) and their corresponding ground truth targets [30]. It is computed as

Here, denotes the number of matches in frame t and expresses the bounding box overlap of object i in frame t with its ground truth. Thus, MOTP measures how closely the predicted bounding box aligns with the ground truth for true positives, indicating the detected objects’ localization precision.

The MOTA is calculated following this formula:

where , , and are the number of misses, false positives, and mismatches, respectively, for time t, normalized by the total number of objects present in all frames.

The IDF1 metric is used to evaluate the consistency of a tracker by measuring the duration over which the tracker correctly follows an object. It is calculated using the formula:

where

- IDTP (ID True Positive) refers to the number of correctly tracked detections,

- IDFP (ID False Positive) refers to the number of incorrectly tracked detections as well as false detections,

- IDFN (ID False Negative) refers to the number of ground truth objects that are not tracked.

Given our primary objective of enhancing detection accuracy, we focus on detA and MOTA as our key performance indicators. As demonstrated in the analysis by Luiten et al. [34], improved detection performance typically increases detA and MOTA while potentially decreasing IDF1 and Higher-order Tracking Accuracy (HOTA), since algorithms that prioritize detection may permit ID switches to capture more objects. Therefore, we evaluate our method using detA and MOTA, which directly align with our detection-focused approach. For direct comparison of performance, we selected ByteTrack as ByteTrack demonstrated the highest weighted macro-average MOTA score on different benchmark datasets [35].

3.6. Hardware

All experiments were conducted on a system with Intel Xeon Gold 6130 32-core CPU with 2.1 GHz clock speed, 128 GB RAM, and NVIDIA TITAN RTX GPU.

4. Results

4.1. Qualitative Performance Analysis in Custom Test Environment

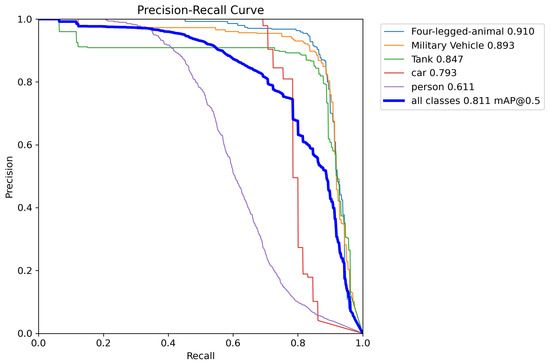

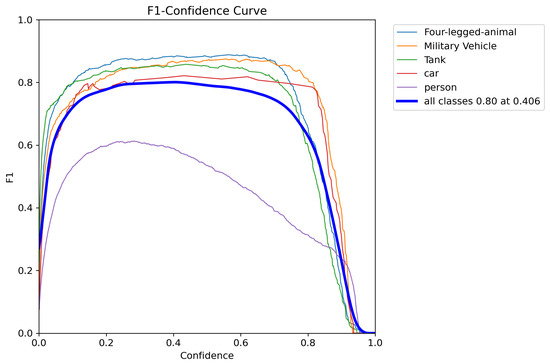

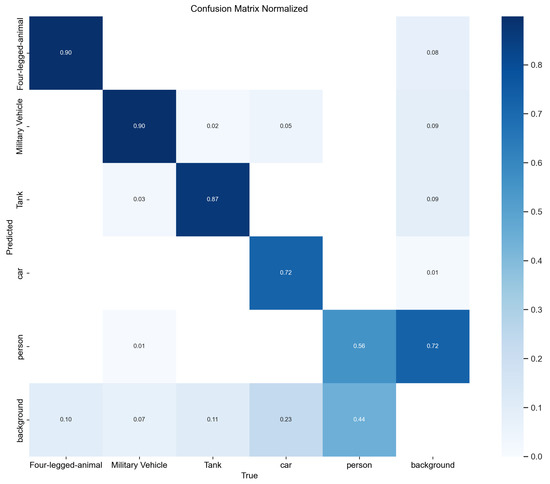

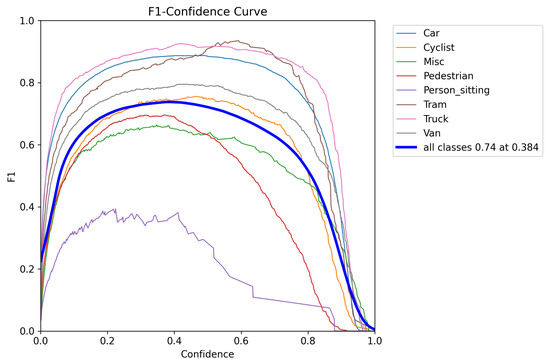

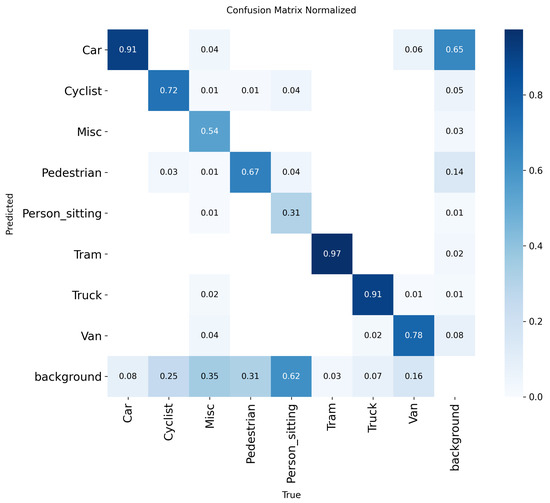

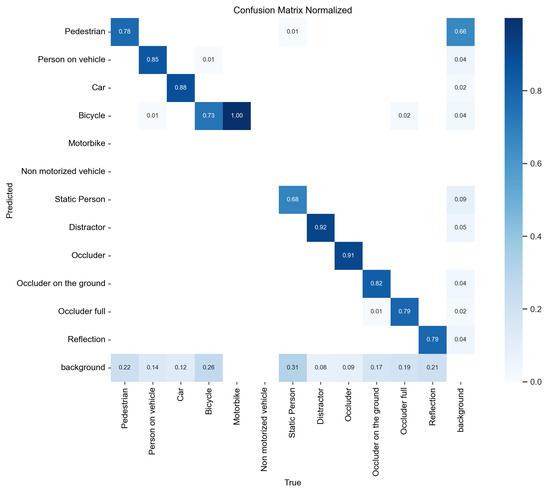

First, we tested our detection enhancement algorithm on a model trained on the custom Unreal Engine scenario. A dataset of 7898 images, including 3004 open-source images from the Roboflow community captured under diverse dynamic lighting conditions and 212 simulated images generated in Unreal Engine, were used to train the YOLO model using five classes: Human, Four-legged animals, Car, Military Vehicles, and Tank. Only deer are included in the “Four-legged animal” class, and the “Military vehicles” class encompasses military trucks, armored personnel carriers (APC), and armored cars. Examples from the training dataset are shown in Figure 6. The ‘Adam’ optimizer was used to train the model with a learning rate of 0.001111 and momentum of 0.9 for 120 epochs. Figure 7 shows the Precision–Recall curve and Figure 8 shows the F1 curve for all classes. The lack of precision and recall—attributable to the limited size of the dataset—resulted in missed detections in several frames due to low confidence, particularly for smaller objects with lower confidence scores. This is evident in Figure 9, where a significant portion of each class objects are misclassified as “background” (i.e., not detected), with the “Person” class exhibiting the highest rate of missed detection due to its smaller size in a frame. In total, 29% of the objects in the test dataset were rejected due to misclassification as background. Upon closer observation, it was found that “Person” objects located farther from the camera were more frequently misclassified due to their smaller image footprint and limited discriminative features. The reduced scale of these distant objects makes it challenging for the model to extract meaningful spatial cues, leading to a higher false-negative rate. A potential approach to mitigate this limitation involves incorporating scale-aware detection strategies or leveraging depth cues to enhance spatial representation such as multimodal fusion for object detection [36,37] or utilizing RGB-D camera data for model training [38] to impart depth information, which increases model complexity and data dimensionality. PrED is designed to alleviate this issue within the RGB domain, as demonstrated in the following sections.

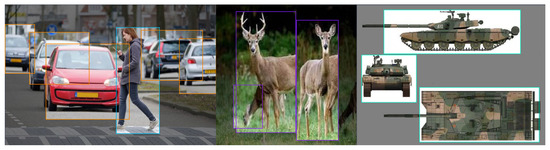

Figure 6.

Sample training images for the custom scenario model.

Figure 7.

Precision–Recall curve of the custom scenario detection model.

Figure 8.

F1 curve of the custom scenario detection model.

Figure 9.

Normalized confusion matrix of the trained model on the test custom detection dataset.

4.1.1. Scenario 2: Object Getting Detected by Backbone for One Frame

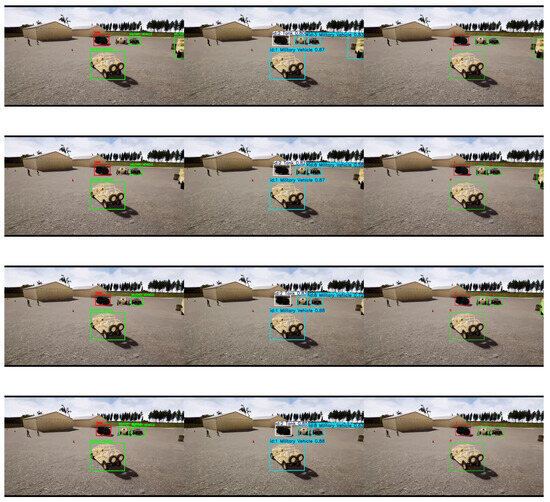

Figure 10 illustrates a scenario where an object is detected by a YOLO detector in a single frame and then disappears. In this case, the pedestrian on the left side of the frame was detected in frame 1 but lost in subsequent frames. PrED, however, continues to track the pedestrian (track 10) in the following frames. The high-confidence detection in frame 1 initializes the track, allowing PrED to leverage low-confidence bounding boxes. Even when no low-confidence bounding box is available in frame 4, PrED is still able to detect track 10 (bounding box with red dot) due to its high value, which enables it to retain the object’s line-of-sight for future frames and enhances detection. In contrast, ByteTrack fails to detect the object in any of the frames.

Figure 10.

Comparison of performance of ByteTrack (middle) and PrED (right) in retaining detection and tracking. The left column consists of high-confidence detection by backbone YOLO. Here, the human is getting tracked after detection by YOLO in frame 1, leveraging low-confidence bounding boxes and high values. The bounding box with a red dot at the center indicates an object missing by the base detector, but still getting tracked due to its high .

4.1.2. Scenario 1: Two Similar Objects in Close Proximity

Figure 11 illustrates a scenario in which two similar objects (four-legged animals/deer) are in close proximity. The YOLO backbone successfully detects the deer further from the vehicles in frame 1 and 2 but loses its detection in subsequent frames. For PrED, these two detections raise the value of the object high enough that it maintains tracking the deer (track 5) in subsequent frames. Meanwhile, the deer close to the vehicles (track 4) are being predicted without any bounding box based on its high (bounding box with red dot). Despite that, no switch in tracking ID was observed. As the value for track 4 decays, its bounding box prediction ceases in frame 5 but reappears in frame 6 with the same tracking ID due to the availability of a low-confidence bounding box. Notably, ByteTrack fails to detect either of the two objects over the six frames.

Figure 11.

Detection and tracking of low-confidence objects by ByteTrack (middle) and PrED (right). The left column consists of high-confidence detections by backbone YOLO. In the right column, track 5 is being consistently predicted in subsequent frames after getting detected by the backbone in frame 1, and successfully avoids ID-switching with track 4, despite both of them being objects of the same class (four-legged animals).

4.1.3. Scenario 3: Object Moving Out of the Frame

The phenomenon of objects rapidly moving out of the frame is common for dashboard-mounted camera scenarios. Figure 12 illustrates a scenario where a vehicle on the right side of the frame gradually disappears from the observer’s point of view. Although the detector fails to detect the object after frame 1, PrED continues tracking the object until it fully disappears. By frame 4, the object (track 7) retains a high value due to its continuous detection in prior frames. However, no bounding box is predicted at this stage due to low similarity in template matching, effectively preventing the generation of false-positive bounding boxes. In contrast, ByteTrack ceases to detect the object after frame 1.

Figure 12.

Comparison of performance of ByteTrack (middle) and PrED (right) when an object gradually moves out of the frame. The left column consists of high-confidence detection by backbone YOLO. The military vehicle in the right edge of the frame (track 7) is gradually moving out of sight. PrED is tracking the vehicle till the last frame.

Again, in Figure 13, we can observe that to maintain the line-of-sight of the disappearing vehicle, PrED keeps creating a bounding box around the disappearing vehicle, even when the detector does not generate even low-confidence bounding boxes for the object (frame 3 and 4, red dot in the bounding box). The algorithm discards the track after the object completely disappears from the frame.

Figure 13.

Comparison of performance of ByteTrack (middle) and PrED (right) when an object gradually moves out of the frame and backbone YOLO stops generating low-confidence bounding box. The left column consists of high-confidence detection by backbone YOLO. The military vehicle (track 12) is not getting detected by YOLO even with low-confidence bounding boxes after frame 1, but PrED continues to track the vehicle till its complete absence.

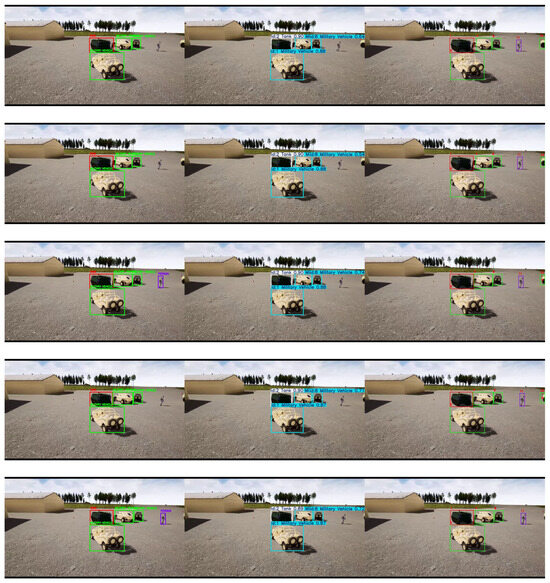

4.2. Evolution of

The predictability score is the key contribution of this study. Figure 14 illustrates its evolution across frames. In frame t, a new high-confidence object under the “four-legged animal” class is detected but unmatched with any existing track, creating a new object ID with (initialized from its confidence score). In frame , the same object is detected again with high confidence and matched with object 5, so increases by to . At frame , it matches a low-confidence detection, leading to another increment by , yielding . In frame , the backbone detector misses the object, but since is higher than , the missing object prediction function takes place. The score is first penalized by , then partially recovered by after confirming that the template similarity between the predicted and stored templates exceeds , prompting the bounding box to be drawn in the final frame.

Figure 14.

Frame-by-frame evolution of predictability score . of track 5 (Four-legged animal). The object is detected by the backbone detector with high confidence in frames t and , and thus the track ID is initialized and continued to frame after calculation of . The object is detected via a low-confidence bounding box in frame . In the final frame, despite the backbone failing to detect the object, the high triggers template similarity calculation. The bounding box with a red dot at the center indicates the template-matched track continuation in the absence of backbone detection.

4.3. Ablation Study

Table 2 presents an ablation study examining the individual contributions of the key algorithmic components introduced in this work. For this analysis, we selected sequence MOT17-13, which features a challenging combination of dense pedestrian and vehicle populations alongside significant camera motion that simulates vehicular movement—conditions that directly align with our algorithm’s intended application domain.

Table 2.

Ablation study on MOT17-13 sequence for different parameters. Here, = introduction to predictability score in algorithm, TM = template matching, ABC = artificial bbox creation, VR = variable reward Ffactor.

The ablation results demonstrate that the predictability score constitutes the primary contributor to false negative reduction, achieving an 18% decrease in false negative cases while providing a modest 0.16% improvement in detection accuracy, alongside more substantial gains of 1.2% in MOTA and 1.3% in IDF1. The subsequent incorporation of template matching as a similarity metric yielded significant performance enhancements, contributing an additional 2% improvement in detection accuracy and a 3.4% increase in IDF1 score relative to the -only algorithm.

PrED v1.5 introduced variable reward factors that assign differential weights to low and high-confidence matches, with low-confidence matches receiving reduced influence in the calculation. This modification effectively addresses the false positive inflation previously caused by extended track memory retention, resulting in a 1.7% improvement in detection accuracy and a substantial 6% increase in MOTA to 0.5513.

The artificial bounding box creation (ABC) component demonstrates considerable potential, independently improving MOTA by 5% even without the variable reward function. While ABC increases false positive rates due to erroneous bounding box generation in object-absent regions, the consistent improvements observed across all performance metrics (detA, MOTA, IDF1) confirm its critical contribution to the overall algorithm effectiveness. The complete PrED v2.2 system, incorporating all four components, achieves comprehensive performance gains: a 23.4% reduction in false negative cases, accompanied by improvements of 4.4% in detection accuracy, 6.8% in MOTA, and 8.8% in IDF1 compared to the baseline. These results are particularly noteworthy given that MOT17 represents one of the most challenging benchmarks due to its dense object populations. The 4–9% performance improvements achieved under these demanding conditions translate to even greater gains in our target application domain—dash-mounted camera tracking from moving vehicles—as empirically validated through experiments on KITTI and custom Unreal Engine scenarios.

4.4. Quantitative Performance Analysis

4.4.1. Custom Unreal Engine Test Environment

Table 3 presents a performance comparison of the three frameworks across different scenarios in the Unreal Engine test environment. Two sample videos from the test environment were selected, and a total of 784 images were manually evaluated for performance analysis. The results demonstrate that the proposed framework significantly enhances detection performance over the baseline YOLO model by reducing false negative cases. The reduction in false negative cases was 33.4% for the low-density scenario and 19.2% for the high-density scenario, resulting in a 15.8% and 11.2% increase in detection accuracy for both cases, respectively. Additionally, the proposed framework achieved MOTA scores of 66.4% and 41.1%, outperforming ByteTrack by 15.8% and 6.9% in the low-density and high-density scenarios, respectively.

Table 3.

Performance comparison in test scenarios. Here, our proposed algorithm is PrED (PrED v2.2).

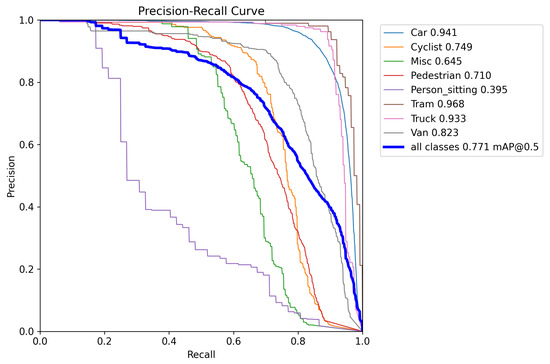

4.4.2. KITTI Training Dataset

To evaluate PrED’s performance on a benchmark driving scenario dataset, we trained a model using the KITTI dataset processed by Sebastian Krauss [39]. The KITTI training dataset contains 7464 images captured under a wide range of shadow patterns and lighting conditions under dry weather, providing natural variability for model evaluation. Four 1.4 Megapixel Point Grey Flea 2 cameras were used to capture RGB and greyscale videos at 10 FPS. The images were later cropped to 1382 × 512 pixels to generate the dataset. To simulate suboptimal detection performance, we employed the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.000833 and momentum of 0.9 for 50 epochs. The resulting model’s performance characteristics are illustrated in Figure 15 (Precision–Recall curve), Figure 16 (F1 curve), and Figure 17 (normalized confusion matrix). The confusion matrix reveals significant detection deficiencies: even at the default confidence threshold of 0.25, the model misclassifies 25% of ‘cyclist’ objects, 31% of ‘pedestrian’ objects, 62% of ‘person sitting’ objects, and 16% of ‘van’ objects as background, demonstrating the substantial room for improvement that PrED aims to address.

Figure 15.

Precision–Recall curve of KITTI object detection model.

Figure 16.

F1 curve of KITTI object detection model.

Figure 17.

Normalized confusion matrix of KITTI object detection model.

Table 4 presents the performance comparison between PrED and ByteTrack on the KITTI training dataset. Consistent with our custom dataset results, PrED significantly outperforms ByteTrack, achieving 8% higher detA and MOTA. Despite some increase in false positive and ID switch cases, the substantial 37.6% reduction in false negative cases proves particularly impactful, enabling PrED to excel across additional tracking metrics, including MOTP, IDF1, and HOTA. These comprehensive improvements demonstrate that PrED’s detection enhancement strategy effectively translates into superior overall tracking performance.

Table 4.

Performance comparison in KITTI training dataset. Here, our proposed algorithm is PrED (PrED v2.2).

4.4.3. MOT17 Training Dataset

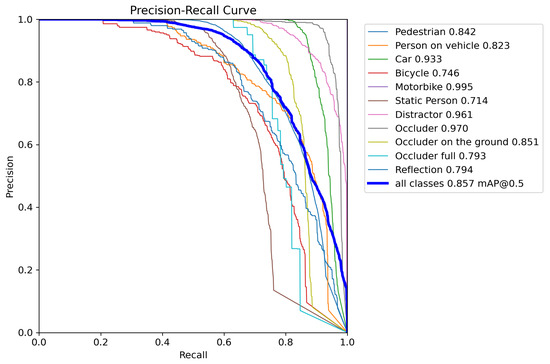

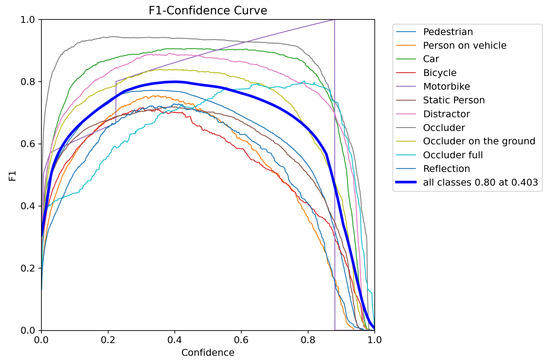

To evaluate PrED’s performance in high-density tracking scenarios, we trained a model using the MOT17 training dataset. The MOT17 training dataset contains image sequences from different Full-HD (1920 × 1080 pixels, 25 FPS) and VGA (640 × 480 pixels, 14 FPS) videos. The training utilized all 15,948 day-and-nighttime images under dry weather without preprocessing or augmentation to maintain realistic conditions. To simulate suboptimal detection performance, we employed the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.000625 and momentum of 0.9 for only 20 epochs—deliberately limiting the training duration. The resulting model’s performance characteristics are shown in Figure 18 (Precision–Recall curve), Figure 19 (F1 curve), and Figure 20 (normalized confusion matrix), which demonstrate the detection deficiencies that PrED is designed to address.

Figure 18.

Precision–Recall curve of MOT17 object detection model.

Figure 19.

F1 curve of MOT17 object detection model.

Figure 20.

Normalized confusion matrix of MOT17 object detection model.

A quick overview of these figures reveals the model’s limited capacity to detect objects across multiple classes, as evidenced by low detection confidence scores and frequent misclassification of objects as background. Table 5 demonstrates that PrED achieved a 13% reduction in false negative cases, translating to 4% improvement in detection accuracy and 1.5% improvement in MOTA compared to ByteTrack. The improvements in detA and MOTA may appear modest compared to those achieved on the KITTI dataset; however, they highlight the robustness of the proposed architecture even in dense, pedestrian-dominant environments such as MOT17. As expected, ByteTrack achieves higher MOTP since PrED deliberately incorporates lower-confidence detections to draw bounding boxes to reduce false negatives, which may introduce some localization noise. While the detection enhancement in this scenario was insufficient to improve IDF1 and HOTA metrics, this outcome aligns with our algorithm’s primary objective of enhancing the detection performance of low-classification-accuracy objects, particularly in challenging high-density environments where even modest improvements represent significant practical gains.

Table 5.

Performance comparison in MOT17 training. Here, our proposed algorithm is PrED (PrED v2.2).

5. Discussion

The proposed PrED framework represents a targeted approach to enhancing detection accuracy and subsequent tracking performance when working with suboptimal detection models. Given the strong dependence of tracking performance on detector accuracy, our primary objective was to effectively leverage low-confidence detections and recover undetected tracks to improve overall system performance. Since PrED is specifically designed for autonomous vehicle applications, maximizing detection accuracy takes precedence over minimizing identity switches, as missed detections pose greater safety risks than occasional track fragmentation.

The PrED architecture integrates three key mechanisms designed to enhance overall detection robustness. First, it employs a one-shot similarity computation for bounding boxes that considers both high- and low-confidence detections, enabling more effective similarity matching across frames. Second, it maintains an adaptive predictability score for each object, which governs the object’s memory retention lifetime through dynamic reward and penalty updates based on prediction consistency. Finally, when the backbone detector fails to identify an object with previously high confidence, PrED performs a template-based similarity assessment to estimate the object’s location and regenerate its bounding box, thus ensuring temporal continuity and mitigating missed detections.

The proposed architecture demonstrates robust performance across all three evaluation environments by predicting undetected objects and generating corresponding bounding boxes, thereby improving object visibility and enhancing both detection and tracking accuracy. In the custom Unreal Engine environment, the algorithm achieves substantial improvements over ByteTrack, with gains of 8–16% in both detection accuracy and MOTA. On the KITTI dataset, PrED outperforms ByteTrack by 8% in both detection accuracy and MOTA, with corresponding improvements observed across all complementary metrics (MOTP, IDF1, HOTA). Even on the challenging MOT17 benchmark, PrED maintains its advantage with improvements of 4% in detection accuracy and 1.5% in MOTA, demonstrating the algorithm’s effectiveness across diverse scenarios ranging from controlled synthetic environments to real-world pedestrian tracking challenges.

These consistent performance gains across varied testing conditions validate the framework’s robustness and its potential for deployment in autonomous vehicle systems, where reliable object detection and tracking are paramount for safe operation.

6. Conclusions

The proposed PrED framework addresses the critical challenge of maintaining object visibility when base detection models fail to identify objects across consecutive frames. By accurately predicting object locations during detection gaps, PrED effectively bridges temporal discontinuities and enhances overall tracking performance. The framework achieves this objective through reliable position prediction for objects lost by the detection algorithm, as evidenced by substantially reduced false negative rates compared to baseline methods.

PrED demonstrates substantial performance improvements across diverse evaluation scenarios. In automotive applications, the framework notably enhances baseline YOLO detection accuracy, leading to consistent gains across all major tracking metrics. Moreover, its performance on the challenging MOT17 dataset highlights PrED’s robustness and generalization capability beyond its primary autonomous vehicle domain.

However, several avenues exist for future enhancement of the framework. Current processing speeds of 13 FPS for low-density scenarios and 3–4 FPS for moderate-to-high-density scenarios limit real-time applicability of PrED. Future work will focus on optimizing memory management and sorting algorithms to achieve higher throughput. Additionally, integrating lightweight neural networks for object-specific feature extraction and directional analysis could further improve tracking precision. These developments would advance PrED toward a more efficient, real-time capable framework suitable for deployment in safety-critical autonomous vehicle systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and S.A.; methodology, A.R.; software, A.R.; validation, A.R. and S.A.; formal analysis, A.R.; investigation, A.R. and S.A.; resources, S.A., H.W. and T.W.; data curation, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; writing—review and editing, S.A.; visualization, A.R.; supervision, S.A.; project administration, S.A., H.W. and T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The source codes of our study are available at: https://github.com/11rahi23/PrED (accessed on 4 September 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the use of Unreal Engine assets by Advanced Science and Automation Corp (ASAC) for model training and evaluation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PrED | Predictive Enhancement of Detection |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| IOU | Intersection over Union |

| detA | Detection Accuracy |

| MOTA | Multi-Object Tracking Accuracy |

| IDF1 | Identity F1 |

| HOTA | Higher Order Tracking Accuracy |

References

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ren, H.; Xie, X.; Cao, Y. A Review of Multi-Object Tracking in Recent Times. IET Comput. Vis. 2025, 19, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, D.H. Generalizing the Hough transform to detect arbitrary shapes. Pattern Recognit. 1981, 13, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.G.; Stephens, M. A combined corner and edge detection. In Proceedings of the 4th Alvey Vision Conference, Manchester, UK, 31 August–2 September 1988; pp. 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshwari, P.; Abhishek, P.; Srikanth, P.; Vinod, T. Object detection: An overview. Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. (IJTSRD) 2019, 3, 1663–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyavani, A.; Dheeraj, K.; Reddy, M.R.M.; Kumar, K.N. Object detection method based on YOLOv3 using deep learning networks. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 9, 1414–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, N.M.; Reddy, R.Y.; Reddy, M.S.C.; Madhav, K.P.; Sudham, G. Object detection and tracking using Yolo. In Proceedings of the 2021 Third International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), Coimbatore, India, 2–4 September 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M. YOLO-v1 to YOLO-v8, the rise of YOLO and its complementary nature toward digital manufacturing and industrial defect detection. Machines 2023, 11, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 3464–3468. [Google Scholar]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 3645–3649. [Google Scholar]

- Brasó, G.; Leal-Taixé, L. Learning a neural solver for multiple object tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 6247–6257. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Huang, P.; Wang, H.; Yu, E.; Liu, D.; Pan, X. Mat: Motion-aware multi-object tracking. Neurocomputing 2022, 476, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.J.; Lin, T.N. DET: Depth-enhanced tracker to mitigate severe occlusion and homogeneous appearance problems for indoor multiple-object tracking. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 8287–8304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathija, A.; Sharma, G. Visual object detection and tracking using yolo and sort. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kapania, S.; Saini, D.; Goyal, S.; Thakur, N.; Jain, R.; Nagrath, P. Multi object tracking with UAVs using deep SORT and YOLOv3 RetinaNet detection framework. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM Workshop on Autonomous and Intelligent Mobile Systems, Bangalore, India, 11 January 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Su, F.; Gong, T.; Meng, H. Strongsort: Make deepsort great again. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 8725–8737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Odashima, S.; Masui, S.; Jiang, S. Hard to track objects with irregular motions and similar appearances? Make it easier by buffering the matching space. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2–7 January 2023; pp. 4799–4808. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, D.; Weng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Bytetrack: Multi-object tracking by associating every detection box. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Aharon, N.; Orfaig, R.; Bobrovsky, B.Z. BoT-SORT: Robust associations multi-pedestrian tracking. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.14651. [Google Scholar]

- Stanojevic, V.D.; Todorovic, B.T. BoostTrack: Boosting the similarity measure and detection confidence for improved multiple object tracking. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2024, 35, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zeng, W.; Liu, W. Fairmot: On the fairness of detection and re-identification in multiple object tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 3069–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Song, X.; Song, H.; Sun, S.; Han, X.F.; Akhtar, N.; Mian, A. Yolo-3DMM for Simultaneous Multiple Object Detection and Tracking in Traffic Scenarios. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 9467–9481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, R. Template Matching Techniques in Computer Vision: Theory and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision meets robotics: The kitti dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, A. MOT16: A benchmark for multi-object tracking. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.00831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Taixé, L.; Milan, A.; Reid, I.; Roth, S.; Schindler, K. Motchallenge 2015: Towards a benchmark for multi-target tracking. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1504.01942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ess, A.; Leibe, B.; Van Gool, L. Depth and appearance for mobile scene analysis. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE 11th International Conference on Computer Vision, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 14–21 October 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ristani, E.; Solera, F.; Zou, R.; Cucchiara, R.; Tomasi, C. Performance measures and a data set for multi-target, multi-camera tracking. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Luiten, J.; Osep, A.; Dendorfer, P.; Torr, P.; Geiger, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Leibe, B. Hota: A higher order metric for evaluating multi-object tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 548–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adžemović, M. Deep Learning-Based Multi-Object Tracking: A Comprehensive Survey from Foundations to State-of-the-Art. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.13457. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yu, A.W.; Meng, T.; Caine, B.; Ngiam, J.; Peng, D.; Shen, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Le, Q.V.; et al. Deepfusion: Lidar-camera deep fusion for multi-modal 3d object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 14–24 June 2022; pp. 17182–17191. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xia, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Qi, S.; Dong, Y.; Dong, N.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, C. Rcbevdet: Radar-camera fusion in bird’s eye view for 3d object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 14928–14937. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Zhan, X.; Xiu, Y.; Suzuki, C.; Shimada, K. Onboard dynamic-object detection and tracking for autonomous robot navigation with rgb-d camera. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 9, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, S. KITTI Dataset. 2022. Available online: https://universe.roboflow.com/sebastian-krauss/kitti-9amcz (accessed on 24 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).