Abstract

Background/Objectives: Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease, the most common hereditary peripheral neuropathy, often causes cavovarus foot deformity in children. Surgical interventions to correct deformity or improve function can involve either primary fusion or reconstruction. However, the optimal surgical approach remains contested. This systematic review aims to present and evaluate existing data on both fusion and reconstruction surgical interventions in treating pediatric CMT cavus foot. Methods: A PRISMA-guided search of five electronic databases was conducted (from inception to 17 February 2025). Studies were eligible if they reported surgical outcomes for CMT pediatric patients (18 years) with cavovarus foot treated by primary fusion or reconstruction. Titles, abstracts and full texts were screened by four independent reviewers, and data were extracted on patient demographics, procedures, follow-up, functional scores, radiographic correction and complications. Results: Fourteen studies met inclusion criteria, encompassing 169 patients and 276 feet, with a mean age at surgery of ~13.5 years. Nine studies evaluated joint-sparing reconstruction, three assessed primary fusion, and two combined both reconstruction and fusion. Both interventions yielded improved outcomes post-operatively. Reconstruction generally produced high patient satisfaction and near-normal radiographic parameters but carried recurrence or reoperation rates of 10–40%. Fusion provided durable correction of rigid deformities but was associated with nonunion, adjacent joint arthritis and higher revision rates. Conclusions: Joint-sparing reconstruction is an effective first-line approach for flexible cavovarus deformities in pediatric CMT patients, while fusion should be reserved for severe, rigid or recurrent cases. A patient-specific staged approach is recommended, and higher-quality comparative studies are needed to refine surgical decision-making.

1. Introduction

Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease is the most common hereditary peripheral neuropathy, affecting roughly 1 in 2500 individuals [1]. This progressive disorder often presents in childhood with distal muscle weakness and sensory loss, leading to characteristic foot deformities. Over half of patients with CMT develop foot and ankle problems, among which a cavovarus (high-arched, varus) foot is by far the most prevalent [2]. The cavovarus posture results from muscular imbalance (e.g., overpull of the plantarflexors/invertors against weakened dorsiflexors and evertors) and can cause significant disability. Affected children may experience frequent ankle sprains, instability, plantar callosities and pain due to the abnormal pressure distribution [2]. If left uncorrected, the rigid varus alignment can overload the lateral foot and ankle, eventually leading to peroneal tendon injuries and varus ankle osteoarthritis [3]. These impairments underscore the importance of effective surgical intervention to restore a plantigrade, stable foot alignment. The primary goal of surgical management in CMT cavovarus foot is to achieve a painless, plantigrade foot that improves stability and gait, ideally reducing the need for bracing [4]. Two broad operative approaches exist: joint-sparing reconstruction versus joint-sacrificing fusion. In pediatric patients, an initial reconstructive strategy is often favored to correct deformity while preserving flexibility and growth potential [2]. This typically involves soft-tissue balancing and osteotomies—procedures such as plantar fascia release, tendon transfers (to re-balance muscle forces), dorsiflexion first metatarsal osteotomy and calcaneal osteotomy are commonly employed [5]. By contrast, in cases of very severe or rigid cavus deformities, surgeons may opt for a primary fusion, classically a triple arthrodesis (fusion of the subtalar, talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints), to obtain immediate correction and hindfoot stability. However, hindfoot fusion in a growing child is generally regarded as a salvage procedure and is used cautiously [2]. Triple arthrodesis permanently sacrifices joint motion and does not address the underlying muscle weakness (for instance, it will not alleviate foot drop without an adjunctive tendon transfer)

Given the lack of consensus on the best primary surgical approach for CMT-related cavus foot, a systematic review of the literature is warranted. The present review aims to consolidate available data on outcomes of primary fusion versus reconstructive surgery in pediatric CMT patients with cavovarus deformity. We compare functional outcomes, radiographic corrections (e.g., improvements in Meary’s angle), complication and reoperation rates, as well as long-term pain relief and patient satisfaction for the two surgical approaches.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic review was designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data Criteria (PRISMA). This systematic review fulfills the PRISMA Checklist (see in the Supplementary Material) and has not been registered [6].

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library from inception to 17 February 2025. Search terms included combinations of “Charcot-Marie-Tooth,” “cavus foot,” “pediatric,” “fusion,” “reconstruction,” and “outcomes” (see Appendix A). References of relevant studies and reviews were also screened to identify additional eligible articles.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) pediatric patients (≤18 years) with CMT-related cavovarus or cavus deformity; (2) interventions consisting of either primary fusion (triple or subtalar arthrodesis) or reconstruction (tendon transfers, osteotomies, soft tissue balancing or combined techniques); (3) reported at least one clinical, radiographic or functional outcome; (4) study design of case series (≥5 patients), cohort studies or randomized controlled trials. Non-English studies, animal studies, case reports, and expert opinions were excluded.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Four reviewers (B.H., K.W., A.I. and J.O) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed against inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and if necessary, consensus among the four reviewers. Data were extracted in duplicate by the same four reviewers using a standardized form, capturing study design, patient demographics, surgical procedures, follow-up, outcomes, complications and reoperations.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

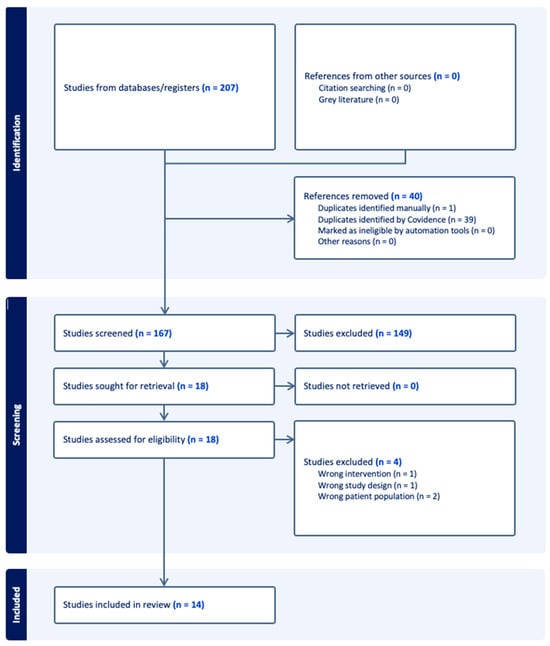

The database search yielded a total of 207 records. No additional studies were identified through citation searching or grey literature. After removal of 40 duplicates (39 by Covidence and 1 manually), 167 unique records remained for screening.

Of these, 149 studies were excluded after title and abstract screening, leaving 18 articles for full-text review. Following assessment of eligibility, four studies were excluded: one for reporting an ineligible intervention, one for inappropriate study design, and two for including the wrong patient population.

A total of 14 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The patient cohorts were predominantly CMT-related cavovarus deformities; some studies included mixed etiologies or combined pediatric and adult cases, but the data for pediatric CMT subgroups were extracted when possible (Table 1). The included studies comprised a total of 169 pediatric patients with CMT and 276 affected feet (Table 2). The majority were retrospective case series or cohort studies (11 of 14), with only three prospective studies identified. The mean age at surgery across studies was approximately 13.5 (range 5–18 years). Follow-up duration varied widely: several recent studies reported short-term outcomes around 1–3 years post-operative [7,8,9,10], whereas one classic study provided 26-year follow-up data [5].

3.3. Surgical Approaches

Among the fourteen studies, nine utilized primarily joint-sparing reconstructive surgeries, while three employed primary fusion procedures, and two had a mix of both approaches in their patient cohorts (Table 3). The reconstructive techniques typically involved a combination of soft tissue releases, tendon transfers and osteotomies, with examples specifically including peroneus longus → brevis transfer, tibialis posterior transfer/lengthening, dorsiflexion first metatarsal osteotomy, lateralizing/Dwyer calcaneal osteotomy, plantar fascia release, and adjunctive gastrocnemius recession or tendo-Achilles lengthening. In contrast, the fusion-focused studies performed triple arthrodesis as the primary intervention [11,12,13].

Table 1.

Study Design and Patient Demographics of Included Studies.

Table 1.

Study Design and Patient Demographics of Included Studies.

| Study | Study Sample | Study Design | Patients | Feet (n) | Sex (M:F) | Mean Age at Surgery (yr) | Mean Follow-Up (yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan 2007 [14] | CMT-Pediatric | Retrospective cohort study | 9 ** | 14 ** | NR | 13.3 ** | NR |

| Galan-Olleros 2025 [15] | Mixed Etiology-Pediatric | Prospective cohort study | 26 ** | 36 ** | 13:13 ** | 12.65 * | NR |

| 6 * | 8 * | 2:4 * | |||||

| Lin 2019 [7] | CMT-Pediatric | Prospective cohort study | 21 ** | 40 ** | 13:8 ** | 12.5 ** | 1.31 ** |

| Mann 1992 [12] | CMT-Pediatric | Retrospective case Series | 10 ** | 12 ** | 6:4 ** | 13.33 ** | 7.58 ** |

| Õunpuu 2025 [8] | CMT-Pediatric | Retrospective cohort study | 19 ** | 29 ** | 11:8 ** | 12.8 ** | 1.6 ** |

| Roper 1989 [16] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective case series | 10 ** | 18 ** | 3:7 ** | 14.0 ** | 14.0 ** |

| 8 * | 16 * | 2:6 * | 11.13 * | 15.75 * | |||

| Sanpera 2018 [9] | Mixed Etiology-Pediatric | Prospective case series | 13 ** | 24 ** | NR | NR | 2.34 ** |

| (Deformity was Neurological in Origin for 7 children) | (13 of Neurological Origin and 11 of Unknown Etiology) | ||||||

| Santavirta 1993 [13] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective cohort study | 15 ** | 26 ** | 6:9 ** | 14.1 * | 14.0 ** |

| 9 * | 15 * | 4:5 * | 16.1 * | ||||

| Simon 2019 [17] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective case series | 20 ** | 26 ** | 10:10 ** | 15.8 ** | 6.2 ** |

| 18 * | 24 * | 9:9 * | 15.1 * | ||||

| Song 2024 [10] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective case series | 29 ** | 29 ** | 13:16 ** | 14.67 * | 0.55 ** |

| 9 * | 9 * | 5:4 * | |||||

| Ward 2008 [5] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective cohort study | 25 ** | 41 ** | 14:11 ** | 15.5 ** | 26.1 ** |

| 21 * | 35 * | 14.1 * | 26 * | ||||

| Weiner 2008 [18] | Mixed Etiology-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective cohort study | 89 ** | 139 ** | 88:51 ** | 9.7 ** | 7.6 ** |

| 5 * | 10 * | 10.88 * | 6.73 * | ||||

| Wicart 2006 [19] | Mixed Etiology-Pediatric | Retrospective case series | 26 ** | 36 ** | 11:15 ** | 10.3 ** | 6.9 ** |

| 16 * | 25 * | 10:6 * | 11.1 * | 6.1 * | |||

| Wukich 1989 [11] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective case series | 22 ** | 34 ** | NR | 16.0 ** | 12.0 ** |

| 18 * | 26 * | 15.4 * | 11.5 * |

* Self-calculated to account for the Pediatric-CMT portion of Study Sample. ** Study provided statistic. NR: No Record.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Pediatric-CMT Sample Portion of Included Studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Pediatric-CMT Sample Portion of Included Studies.

| Total Sample Size | |

|---|---|

| Patients | 169 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Patient Statistic | 1 (7.14%), [9] |

| Feet | 276 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Feet Statistic | - |

| Total Male | 62 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Male Gender Statistic | 5 (35.71%) |

| Total Female | 54 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Female Gender Statistic | 5 (35.71%) |

| Mean Age at surgery, year, (range) | 13.46 (5–18) |

| Median Age at surgery | 14 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Data on Age | 3 (21.43%) |

| Mean Length of Follow Up, year, (range) | 13.79 (2–34) |

| Median Length of Follow Up | 9.73 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Data on Length of Follow up | 7 (50.0%) |

| Study Design | |

| Prospective Cohort Study | 2 (14.29%) |

| Retrospective Cohort Study | 5 (35.71%) |

| Prospective Case Series Study | 1 (7.14%) |

| Retrospective Case Series Study | 6 (42.86%) |

Table 3.

Surgical Techniques Performed on Pediatric-CMT Sample Portion in Included Studies.

Table 3.

Surgical Techniques Performed on Pediatric-CMT Sample Portion in Included Studies.

| Study | Approach | Procedure | Patients | Feet (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan 2007 [14] | Reconstruction | Medial Plantar Release | NR | 10 |

| Posterior Tibialis Tendon Transfer | 11 | |||

| Jones Procedure | 2 | |||

| Flexor Digitorum Longus Tenotomy | 2 | |||

| Midfoot Osteotomy | 3 | |||

| First Metatarsal Extension Osteotomy | 3 | |||

| First and Second Metatarsal Extension Osteotomy | 3 | |||

| First to Third Metatarsal Osteotomy | 2 | |||

| Gastrocnemius Recession | 2 | |||

| Plantar Fascia Release | 1 | |||

| Lateral Column Shortening (cuboid) | 1 | |||

| Galan-Olleros 2025 [14] | Reconstruction | Talo-Calcaneo-Navicular Realignment | 6 | 8 |

| Lin 2019 [7] | Fusion & Reconstruction | Plantar fascia release | 17 | NR |

| First metatarsal osteotomy | 18 | |||

| Peroneus longus to brevis transfer | 14 | |||

| Tibialis anterior tendon transfer | 3 | |||

| Strayer calf lengthening | 1 | |||

| Tendon Achilles lengthening | 9 | |||

| Lateral displacement calcaneal osteotomy | 9 | |||

| Jones transfer with interphalangeal joint fusion | 1 | |||

| Tibialis posterior lengthening | 3 | |||

| Tibialis posterior to peroneus brevis transfer | 2 | |||

| Tibialis posterior tendon transfer | 4 | |||

| Split anterior tibialis tendon transfer | 1 | |||

| Second toe proximal interphalangeal joint fusion | 1 | |||

| Lateral closing wedge mid-tarsal osteotomy | 1 | |||

| Lateral closing wedge calcaneal osteotomy | 2 | |||

| Mann 1992 [12] | Fusion | Triple Arthrodesis | 10 | 12 |

| Õunpuu 2025 [8] | Reconstruction | Triceps Surae Lengthening (TSL): | 12 | 19 |

| Gastrocnemius Recession (GR) | 8 | |||

| Tendo Achilles Lengthening (TAL) | 11 | |||

| Plantar Fascia Release + Foot Osteotomy: | 14 | 20 | ||

| Combined with Triceps Surae Lengthening | 10 | |||

| Without Triceps Surae Lengthening | 10 | |||

| Roper 1989 [16] | Reconstruction | Elongation Calcaneal Tendon | 6 | 12 |

| Tibialis Anterior Transfer | 7 | 14 | ||

| Tibialis Posterior Transfer | 1 | 2 | ||

| Steindler Release | 7 | 14 | ||

| Flexor-to-Extensor Transfer | 2 | 4 | ||

| Calcaneal Osteotomy | 1 | 2 | ||

| Robert Jones Procedure | 2 | 4 | ||

| Sanpera 2018 [9] | Reconstruction | Dorsal Hemiepiphysiodesis of the 1st Metatarsal + Plantar Fascia Release | 7 | 13 |

| Santavirta 1993 [13] | Fusion | Triple Arthrodesis | 7 | 12 |

| Grice Arthrodesis | 1 | 1 | ||

| Interphalangeal Fusion of the 1st Toe | 1 | 2 | ||

| Simon 2019 [17] | Reconstruction | Revisited Meary dorsal closing-wedge tarsectomy + Plantar fascia release + Dwyer calcaneal osteotomy + | 18 | 24 |

| First metatarsal extension osteotomy | NR | 16 (not stratified by age) | ||

| Song 2024 [10] | Reconstruction & Fusion | Achilles Triple Hemisection | 9 | 9 |

| Posterior Tibial Tendon Transfer | 8 | 8 | ||

| Talonavicular Joint and Spring Ligament Release | 9 | 9 | ||

| Flexor Digitorum Longus Tenotomy | 6 | 6 | ||

| Plantar Fascia Release | 7 | 7 | ||

| Calcaneal Osteotomy | 7 | 7 | ||

| Peroneus Longus Resection and Transfer to Peroneus Brevis | 9 | 9 | ||

| Closing-Wedge Osteotomy of the 1st Metatarsal | 6 | 6 | ||

| 1st Interphalangeal Joint Fusion | 1 | 1 | ||

| Extensor Tendon Transfer | 3 | 3 | ||

| Flexor Tendon Transfer | 2 | 2 | ||

| Ward 2008 [5] | Reconstruction | Peroneus Longus Transfer to Peroneus Brevis Tendon | 33 | 24 |

| Plantar Fasciotomy | 32 | 23 | ||

| First Metatarsal Dorsiflexion Osteotomy | 29 | 23 | ||

| Extensor Hallucis Longus Recession/Jones procedure | 27 | 20 | ||

| Anterior Tibialis Transfer | 10 | 9 | ||

| Weiner 2008 [18] | Reconstruction | Akron Dome Midfoot Osteotomy (transverse dorsal midfoot approach, two dome-shaped osteotomy cuts, multiplanar correction of cavus/varus/rotation at the deformity apex) | 4 | 11 |

| Wicart 2006 [19] | Reconstruction | Plantar opening-wedge osteotomy of all 3 cuneiforms, Dwyer osteotomy, and selective plantar release + | 16 | NR |

| Medial release | 8 | |||

| Lateral column shortening | 4 | |||

| First metatarsal dorsal wedge osteotomy | 9 | |||

| Wukich 1989 [11] | Fusion | Triple Arthrodesis | 18 | 27 |

NR: No Record.

3.4. Functional Outcomes

Despite differences in surgical technique, both fusion and reconstruction groups demonstrated functional improvements, though measured in different ways (Table 4). The reconstructive studies commonly employed standardized functional scores and patient-reported outcome measures. In a recent prospective cohort, Galán-Olleros et al. documented significant improvements in all patient-reported outcome measures following joint-sparing reconstruction [15]. The median Foot and Ankle Disability Index (FADI) increased from 41 pre-operatively to 90 post-operatively (on a 0–100 scale, p < 0.001), and the Foot Function Index (FFI) and Maryland Foot Score (MFS) likewise showed large, significant gains. High patient satisfaction was reported in this study—the majority of families rated outcomes as “exceeded expectations,” and most patients would recommend the surgery and undergo it again if needed. Simon et al. reported American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society (AOFAS) scores in a subset of patients following reconstruction: median hindfoot score was 95.5/100 (IQR 84–98), indicating excellent function in the hindfoot/ankle domain, although median midfoot score was lower (75/100), reflecting some residual midfoot stiffness or symptoms [17]. Overall, the majority of patients in the reconstruction cohorts experienced substantial relief of pain and improvement in mobility.

Table 4.

Comparison of Post-Operative Outcomes Across Included Studies.

Functional outcomes in the fusion cohorts were typically reported in more qualitative terms or via surgeon-derived rating scales, given the era and design of many such studies. Nevertheless, these outcomes indicate that fusion can also restore a considerable degree of function and relieve pain, albeit with some limitations. Wukich et al. noted that 21 out of 22 patients were able to ambulate independently after their hindfoot fusions; 16 patients could walk over 800 m without braces, and 5 could walk 400–800 m (2 of those without braces) [11]. This represents a major improvement for many children who pre-operatively may have been limited by foot deformity and instability. However, on objective evaluation, most fusion outcomes were classified as fair or worse—consistent with residual pain or deformity—and only 32% of Yet, objective ratings classified the majority of those fusion outcomes as “Fair” or worse, indicating residual pain or deformity with only 32% of operated feet meeting the criteria for “Good”. In another study, 9 of 12 CMT feet treated with fusion (75%) were clinically asymptomatic at follow-up—pain-free with neutral dorsiflexion and hindfoot/forefoot alignment [12].

3.5. Radiographic Correction

Across the reconstructive cohorts, radiographic indicators of cavovarus deformity showed marked improvement post-operatively (Table 4). Many studies reported Meary’s angle (the talus–first metatarsal angle on lateral view) or analogous measures pre- and post-surgery. For example, Simon et al. documented correction of Meary’s angle from a pre-operative mean of approximately +16.7° (cavus) to −1.4° (nearly neutral) after multiplanar reconstruction, a highly significant change (p < 0.0001) [17]. Similarly, in a 2024 series using combined reconstruction with selective fusions, the sagittal Meary’s angle improved from about 14.8° pre-op to 0.1° post-op (p < 0.001) on 3D weightbearing imaging [10]. Other common angular metrics, including talonavicular coverage angle and Saltzman view angle, showed significant normalization after reconstruction. Another study reported substantial correction of forefoot-driven cavus, with the mean lateral talus–first metatarsal (Meary) angle improving from −16.9° pre-operatively to −1.6° post-operatively (p = 0.001), alongside significant gains in the calcaneus–first metatarsal angle and calcaneal pitch [14].

By contrast, the fusion studies did not uniformly report detailed radiographic angle measurements. The lack of numeric angular data in older fusion studies makes direct comparison difficult; however, achieving a plantigrade foot (defined by a neutral or slight valgus heel and a normalized arch on radiographs) was a primary goal and was typically attained initially in these fusion cohorts.

3.6. Complications and Reoperations

The nature and frequency of complications varied between reconstructive and fusion-based surgical strategies, although both approaches carried some risk (Table 4). Complications following reconstruction surgery were typically related to soft tissue healing, hardware issues or the underlying neuromuscular deficits. For example, Lin et al. reported one child (of 21) who developed complex regional pain syndrome post-operatively, which resolved with therapy, and no significant osteotomy non-unions or neurovascular injuries [7]. Sanpera et al. encountered three technical complications in 13 children (two malpositioned screws requiring reoperations for repositioning and one plate breakage) [9]. Skin problems were occasionally noted: Simon et al. had one wound necrosis after a large osteotomy, which necessitated conversion to a fusion (triple arthrodesis) in that case [17]. Overall, nonunion was rare in the reconstructive groups because most osteotomies were fixated and bone healing was not heavily impaired. Instead, the predominant concern in reconstructions was residual or recurrent deformity, which often led to reoperations. Wicart et al. followed 25 CMT feet after joint-sparing correction and found that 11 feet (44%) eventually required revision surgeries, including 8 feet (32%) that underwent a salvage triple arthrodesis due to recurrent cavovarus or persistent instability [19]. Roper and Tibrewal similarly also reported two cases of recurrent deformity necessitating further correction [16]. Even in more recent series with shorter follow-up, some reoperations were needed: Simon et al. observed 3 reoperations among 26 feet (11.5%), including one re-fusion following wound complications, one repeat osteotomy for delayed healing and one hardware removal [17]. In the 2008 study by Weiner et al., which evaluated an “Akron dome” osteotomy technique, poor outcomes were largely attributed to recurrent deformity, often managed with repeat osteotomies (mean 1.8 reoperations in unsatisfactory cases vs. 0.6 in satisfactory cases) [18].

In contrast, fusion-based procedures—while more definitive in achieving deformity correction—were associated with a higher incidence of nonunion and adjacent joint sequelae. Mann et al. reported nonunion in 3 of 12 triple arthrodesis, affecting the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints, with some failures identified up to 12 years post-operatively [12]. Santavirta et al. observed a nonunion rate of 19% (4 of 21 feet) for triple fusions and an additional nonunion following a pantalar fusion [13]. Reoperation rates after fusion were also substantial: in Santavirta’s long-term follow-up, 17 of 26 feet (65%) required further surgical intervention [13]. These included repeat fusions for failed arthrodesis (n = 4), revision for malalignment (n = 2) and ankle fusions for progressive talocrural arthritis (n = 2) [13]. Similarly, Wukich et al. reported 12 additional surgeries in 9 patients following initial correction, including contralateral or revision triple arthrodesis and procedures such as bunionette corrections [11]. Fusion procedures were associated with reduced reliance on bracing, with Wukich et al. reporting a decrease in post-operative brace use from 11 to 3 patients [11]. However, this benefit was offset by the loss of joint mobility, as long-term radiographic follow-up frequently demonstrated degenerative changes in adjacent joints, particularly at the ankle and midfoot, highlighting the biomechanical consequences of immobilization [11].

In summary, reconstructive surgery was associated with lower short-term complication rates (e.g., fewer wound issues or nonunions), but carried a notable risk of deformity recurrence, in 11/25 feet (44%) (Wicart et al.) and 3/26 feet (11.5%) (Simon et al.). In contrast, fusion procedures achieved more durable correction at the expense of higher rates of nonunion (up to ~20%) and a greater frequency of secondary interventions (e.g., re-fusions, hardware revision or treatment of adjacent joint arthritis), affecting over half of patients in some series.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review of surgical management for CMT-related cavovarus foot in pediatric patients, we found that both reconstructive and fusion-based approaches can ultimately yield a plantigrade, functional foot, but with markedly different profiles of outcomes and trade-offs. Reconstructive surgeries (comprising tendon transfers, osteotomies and soft tissue releases) led to significant improvements in foot alignment and patient function, with children often achieving near-normal radiographic parameters and reporting high satisfaction. These joint-sparing procedures preserved mobility and delayed or avoided the need for arthrodesis in the majority of cases. However, recurrence of deformity was a recurrent theme—as children grew and the underlying neuromuscular disorder persisted, some required additional interventions to maintain correction. Fusion procedures (like triple arthrodesis) provided more immediate and permanent correction of the deformity, stabilizing severe cases and relieving pain. Yet the cost of this rigidity was evident: hindfoot motion was eliminated, and a substantial fraction of patients suffered fusion-related complications (nonunion, adjacent joint stress) necessitating further surgeries. Taken together, this evidence highlights a fundamental tension in treating the pediatric CMT cavus foot: the pursuit of flexibility and growth accommodation versus the desire for definitive correction. Our review’s key insight is that joint-sparing reconstruction can yield excellent early outcomes in pediatric CMT patients with flexible deformities, but careful long-term surveillance because the underlying neuropathy can lead to recurrent deformity, sometimes necessitating staged or delayed fusion. Fusion, while inevitable in severe cases, should be timed and executed with caution given the substantial revision rates and long-term joint consequences.

Our findings are consistent with and add nuance to the prior literature on cavovarus foot management. Historically, triple arthrodesis has been considered the “gold standard” for severe pes cavovarus deformities. Saltzman et al. reported on long-term outcomes of triple arthrodesis at an average of 30+ years, showing that patients remained highly satisfied (95%) with the fusion in terms of improved function, even though many developed arthritic changes in adjacent joints and some residual pain [20]. Similarly, Wukich and Bowen’s series reported that only 32% of fused feet met “good” objective criteria despite 86% patient satisfaction [11]. The current review echoes these findings: fusion procedures were often associated with high subjective satisfaction, even in the presence of radiographic arthritis, residual stiffness or suboptimal objective outcomes. However, our analysis underlines a point increasingly emphasized in recent years—fusion is best viewed as a salvage procedure for pediatric cavovarus, to be used when joint-sparing options are not feasible or have failed [21,22]. The recurrence rates we found for reconstructions (e.g., 32% conversion to fusion in Wicart’s series) reinforce prior observations that neuropathic cavovarus has a tendency to worsen over time [17,23,24]. This aligns with the existing literature supporting the use of tendon transfers and osteotomies in flexible deformities to restore muscle balance and preserve joint motion, while recognizing that fusion may ultimately be required when deformity progresses despite these interventions [3,25].

This review has several important limitations. First, the evidence base is limited to Level III–IV studies, primarily retrospective case series, introducing high risk of bias. No randomized or comparative cohort studies directly evaluating reconstruction versus fusion were identified. Surgical approach was typically based on deformity severity and surgeon preference, leading to selection bias. Second, substantial heterogeneity existed among studies. Some included mixed etiologies or combined pediatric and adult patients. Although pediatric CMT-specific data were extracted where possible, differences in age and disease severity may confound outcomes. Reconstruction techniques also varied widely—from minimal soft tissue procedures in young children to multilevel osteotomies in adolescents—limiting generalizability and precluding meta-analysis. Third, outcome measures were inconsistent. Functional outcomes ranged from formal scoring systems (AOFAS, FADI, 6 min walk) to subjective terms like “good” or “fair,” requiring qualitative interpretation. Radiographic measures such as Meary’s angle were more consistent, though some studies used non-comparable modalities like weight-bearing CT. Finally, follow-up was often short (<2 years), limiting assessment of long-term failures or late complications. Conversely, older long-term studies (>10 years) may not reflect modern techniques or implants, underestimating improvements in current fusion practices. The lack of uniform data precluded quantitative pooling, so our conclusions are based on observed trends rather than statistical comparisons. These limitations underscore the need for prospective, comparative research—such as multicenter registries—to better guide surgical decision-making in CMT cavovarus deformities.

Despite the above limitations, the compiled evidence provides valuable guidance for clinicians managing cavovarus foot deformity in pediatric CMT patients. The choice between reconstruction and fusion in a growing CMT patient should be individualized, but certain guiding principles emerge. In general, flexible or moderate deformities are best managed with joint-sparing techniques, aiming to rebalance muscles and correct bony alignment while preserving motion. This strategy addresses the components of the cavovarus (equinus, first ray plantarflexion, hindfoot varus) in a graded manner—e.g., soft tissue releases and tendon transfers to restore muscular balance, coupled with osteotomies to correct bony malalignment. In early stages of the disease, where flexibility and growth potential remain, this surgical approach is guided by the need to maintain mobility and accommodate ongoing musculoskeletal development, a principle consistent with current literature [22]. Our review affirms that this approach yields high rates of plantigrade, pain-free feet in the short-to-intermediate term. However, families should be counseled that recurrent deformity can occur as the child grows and as neuropathy progresses. In our included studies, roughly 10–40% of reconstructed feet eventually required a second intervention, which in some cases meant a delayed fusion (often during adolescence or young adulthood) to stabilize a relapsed deformity. Notably, even when a late fusion becomes necessary, it is performed at a more skeletally mature age—potentially reducing the impact on foot development and leveraging the benefits of having postponed arthrodesis. On the other hand, primary fusion is appropriate for patients with very severe, rigid deformities or in those who have failed prior reconstructions. In such cases, the immediate correction and hindfoot stability afforded by a well-positioned triple arthrodesis can significantly improve pain and weight-bearing ability. Even after a successful fusion, ongoing surveillance is needed for adjacent joint arthritis, and patients may require bracing or shoe modifications for optimal function. Ultimately, the treatment algorithm endorsed by current evidence and expert opinion is to preserve joints whenever possible in the pediatric CMT foot, resorting to arthrodesis only for salvage or when deformities are fixed and non-response to soft tissue methods. This phased approach—reconstruct first, fuse if needed later—maximizes the years of mobility and may improve long-term patient satisfaction.

5. Conclusions

By synthesizing evidence across decades, our review reinforces that joint-sparing reconstruction is effective for many pediatric cavovarus feet, restoring function and delaying arthrodesis. However, the progressive nature of CMT and the risk of recurrence necessitate long-term surveillance and readiness to intervene again. Fusion remains an essential tool for rigid or salvage cases, achieving durable alignment at the expense of motion. Ultimately, individualized, staged management—grounded by careful assessment, informed by evolving evidence and tailored to patient needs—offers the best prospects for achieving a pain-free, plantigrade foot in children with CMT.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/osteology5040036/s1, PRISMA Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.K., K.G. and Z.L.; methodology, W.K., K.G. and Z.L.; validation, W.K., K.G. and Z.L.; formal analysis, W.K., K.G., Z.L., B.H., K.W., A.I. and J.O.; investigation, W.K., K.G., Z.L., B.H., K.W., A.I. and J.O.; writing—original draft preparation, B.H. and K.W.; writing—review and editing, W.K., K.G., Z.L., B.H., K.W., A.I. and J.O.; visualization, B.H., K.W., A.I. and J.O.; supervision, W.K., K.G. and Z.L.; project administration, W.K., K.G., Z.L., B.H., K.W., A.I. and J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Search Strategy

MEDLINE (via Ovid or PubMed)

- CMT/Neuropathy Terms

- 1.

- exp Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease/

- 2.

- (Charcot-Marie-Tooth or CMT or hereditary motor sensory neuropathy or HMSN).kf,ti,ab.

- Cavus Foot Deformity

- 3.

- exp Foot Deformities/ or exp Pes Cavus/

- 4.

- (cavus foot or cavovarus or pes cavus or high arch or foot deformit*).kf,ti,ab.

- Pediatric Population

- 5.

- exp Child/ or exp Pediatrics/ or exp Adolescent/

- 6.

- (child* or pediatric* or paediatric* or adolescen* or teen* or young patient*).kf,ti,ab.

- Surgical Intervention: Fusion

- 7.

- exp Arthrodesis/ or exp Joint Fusion/

- 8.

- (arthrodesis or fusion or triple arthrodesis or subtalar fusion or talonavicular fusion or calcaneocuboid fusion).kf,ti,ab.

- Surgical Intervention: Reconstruction

- 9.

- exp Osteotomy/ or exp Tendon Transfer/ or exp Fasciotomy/ or exp Soft Tissue Surgical Procedures/

- 10.

- (reconstruct* or osteotomy or osteotomies or tendon transfer or plantar fascia release or peroneus transfer or Dwyer or Cole or Japas or first metatarsal osteotomy).kf,ti,ab.

- Outcomes

- 11.

- (AOFAS or FFI or SF-36 or PROMIS or Meary* angle or talo-first metatarsal angle or radiographic outcome* or functional outcome* or complication* or reoperation or satisfaction or gait or pain).kf,ti,ab.

Search string:

((1 OR 2) AND (3 OR 4) AND (5 OR 6)) AND ((7 OR 8) OR (9 OR 10)) AND (11)

EMBASE

- exp Charcot Marie Tooth disease/

- (Charcot-Marie-Tooth or CMT or hereditary motor sensory neuropathy or HMSN).kw,ti,ab.

- exp foot deformity/ or exp pes cavus/

- (cavus foot or cavovarus or pes cavus or high arch or foot deformit*).kw,ti,ab.

- exp child/ or exp adolescent/ or exp pediatrics/

- (child* or pediatric* or paediatric* or adolescen* or teen* or young patient*).kw,ti,ab.

- exp arthrodesis/ or exp joint fusion/

- (fusion or triple arthrodesis or subtalar fusion or talonavicular fusion or calcaneocuboid fusion).kw,ti,ab.

- exp osteotomy/ or exp tendon transfer/ or exp soft tissue surgery/

- (osteotomy or tendon transfer or Dwyer or Japas or plantar fascia release).kw,ti,ab.

- (AOFAS or FFI or SF-36 or PROMIS or Meary* angle or talo-first metatarsal angle or functional outcome* or complication* or reoperation or satisfaction or gait or pain).kw,ti,ab.

Search string:

((1 OR 2) AND (3 OR 4) AND (5 OR 6)) AND ((7 OR 8) OR (9 OR 10)) AND (11)

Appendix B

Excluded Full-Text Studies

| Title | Authors | Published Year | Journal | Reason for Exclusion |

| Treatment of equinocavovarus deformity in adults with the use of a hinged distraction++ apparatus. [26] | Oganesyan, O V; Istomina, I S; Kuzmin, V I | 1996 | The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume | Exclusion reason: Wrong intervention |

| Navicular excision and cuboid closing wedge for severe cavovarus foot deformities: A salvage procedure [27] | Mubarak, S.J.; Dimeglio, A. | 2011 | J. Pediatr. Orthop. | Exclusion reason: Wrong patient population |

| Neuropathic ankle joint in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease after triple arthrodesis of the foot. [28] | Medhat, M A; Krantz, H | 1988 | Orthopaedic review | Exclusion reason: Wrong study design |

| Is there a place for dorsal hemiepiphysiodesis of the first metatarsal in the treatment of pes cavovarus? [29] | Domingues, L.S.; Norte, S.; Thusing, M.; Neves, M.C. | 2025 | J. Pediatr. Orthop. Part B | Exclusion reason: Wrong patient population |

References

- Nagappa, M.; Sharma, S.; Taly, A.B. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Olney, B. TREATMENT OF THE CAVUS FOOT: Deformity in the Pediatric Patient with Charcot-Marie-Tooth. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000, 5, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.S. Reconstruction of Cavus Foot: A Review. Open Orthop. J. 2017, 11, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haupt, E.T.; Porter, G.M.; Blough, C.; Michalski, M.P.; Pfeffer, G.B. Outcomes of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Cavovarus Surgical Reconstruction. Foot Ankle Int. 2024, 45, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, C.M.; Dolan, L.A.; Bennett, D.L.; Morcuende, J.A.; Cooper, R.R. Long-Term Results of Reconstruction for Treatment of a Flexible Cavovarus Foot in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2008, 90, 2631–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Gibbons, P.; Mudge, A.J.; Cornett, K.M.D.; Menezes, M.P.; Burns, J. Surgical Outcomes of Cavovarus Foot Deformity in Children with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2019, 29, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Õunpuu, S.; Pierz, K.A.; Rethlefsen, S.A.; Rodriguez-MacClintic, J.; Acsadi, G.; Kay, R.M.; Wren, T.A.L. Outcomes of Triceps Surae Lengthening Surgery in Children With Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Multisite Investigation. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2025, 45, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanpera, I., Jr.; Frontera-Juan, G.; Sanpera-Iglesias, J.; Corominas-Frances, L. Innovative Treatment for Pes Cavovarus: A Pilot Study of 13 Children. Acta Orthop. 2018, 89, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Michalski, M.P.; Pfeffer, G.B. 3D Analysis of Joint-Sparing Charcot-Marie-Tooth Surgery Effect on Initial Standing Foot Alignment. Foot Ankle Int. 2024, 45, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wukich, D.K.; Bowen, J.R. A Long-Term Study of Triple Arthrodesis for Correction of Pes Cavovarus in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1989, 9, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.C.; Hsu, J.D. Triple Arthrodesis in the Treatment of Fixed Cavovarus Deformity in Adolescent Patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Foot Ankle 1992, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santavirta, S.; Turunen, V.; Ylinen, P.; Konttinen, Y.T.; Tallroth, K. Foot and Ankle Fusions in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 1993, 112, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.; Sampath, J.; Miller, F.; Riddle, E.C.; Nagai, M.K.; Kumar, S.J. The Role of the Dynamic Pedobarograph in Assessing Treatment of Cavovarus Feet in Children With Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2007, 27, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Olleros, M.; Chorbadjian-Alonso, G.; Ramírez-Barragán, A.; Figueroa, M.J.; Fraga-Collarte, M.; Martínez-González, C.; Prato De Lima, C.H.; Martínez-Caballero, I. Talocalcaneonavicular Realignment: The Foundation for Comprehensive Reconstruction of Severe, Resistant Neurologic Cavovarus, and Equinocavovarus Foot Deformities in Children and Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2025, 45, e156–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, B.; Tibrewal, S. Soft Tissue Surgery in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1989, 71-B, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.-L.; Seringe, R.; Badina, A.; Khouri, N.; Glorion, C.; Wicart, P. Long Term Results of the Revisited Meary Closing Wedge Tarsectomy for the Treatment of the Fixed Cavo-Varus Foot in Adolescent with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019, 25, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, D.S.; Morscher, M.; Junko, J.T.; Jacoby, J.; Weiner, B. The Akron Dome Midfoot Osteotomy as a Salvage Procedure for the Treatment of Rigid Pes Cavus: A Retrospective Review. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2008, 28, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicart, P.; Seringe, R. Plantar Opening-Wedge Osteotomy of Cuneiform Bones Combined With Selective Plantar Release and Dwyer Osteotomy for Pes Cavovarus in Children. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2006, 26, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltzman, C.L.; Fehrle, M.J.; Cooper, R.R.; Spencer, E.C.; Ponseti, I.V. Triple Arthrodesis: Twenty-Five and Forty-Four-Year Average Follow-up of the Same Patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1999, 81, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenwasser, K.A.; Judd, H.; Hyman, J.E. Evidence-Based Management Strategies for Pediatric Pes Cavus: Current Concept Review. J. Pediatr. Orthop. Soc. N. Am. 2022, 4, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, T.; Winson, I. Joint Sparing Correction of Cavovarus Feet in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: What Are the Limits? Foot Ankle Clin. 2013, 18, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur Vithran, D.T.; Liu, X.; He, M.; Essien, A.E.; Opoku, M.; Li, Y.; Li, M.-Q. Current Advancements in Diagnosing and Managing Cavovarus Foot in Paediatric Patients. EFORT Open Rev. 2024, 9, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranho, D.A.; Volpon, J.B. Acquired Pes Cavus in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2015, 44, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Wu, S.; Zhang, H. Evaluation and Management of Cavus Foot in Adults: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oganesyan, O.V.; Istomina, I.S.; Kuzmin, V.I. Treatment of Equinocavovarus Deformity in Adults with the Use of a Hinged Distraction Apparatus. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1996, 78, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, S.J.; Dimeglio, A. Navicular Excision and Cuboid Closing Wedge for Severe Cavovarus Foot Deformities: A Salvage Procedure. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2011, 31, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhat, M.A.; Krantz, H. Neuropathic ankle joint in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease after triple arthrodesis of the foot. Orthop Rev. 1988, 17, 873-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Domingues, L.S.; Norte, S.; Thusing, M.; Neves, M.C. Is there a place for dorsal hemiepiphysiodesis of the first metatarsal in the treatment of pes cavovarus? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2025, 34, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).