Outcomes of Primary Fusion vs. Reconstruction of Pediatric Cavus Foot in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

3. Results

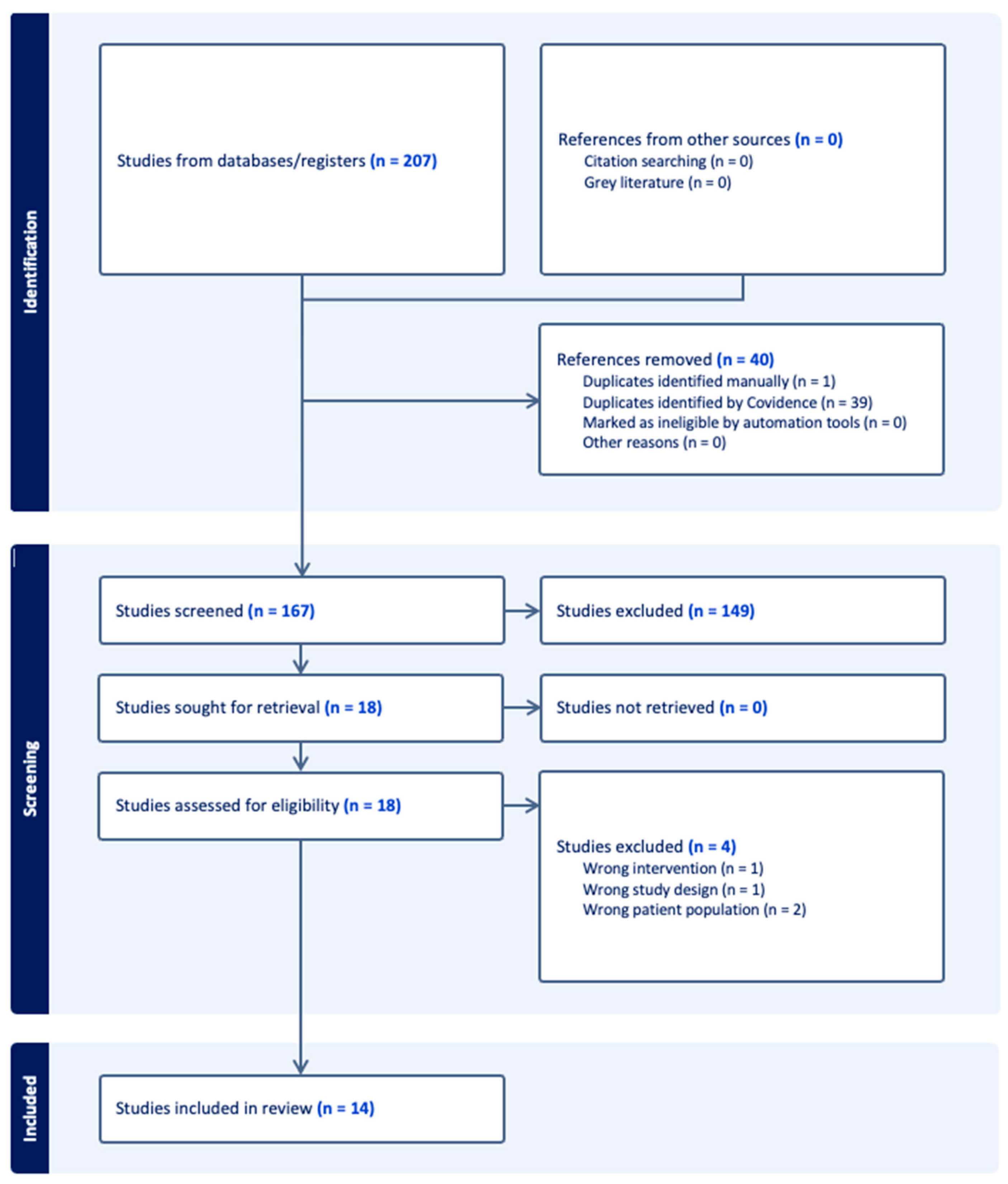

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Surgical Approaches

| Study | Study Sample | Study Design | Patients | Feet (n) | Sex (M:F) | Mean Age at Surgery (yr) | Mean Follow-Up (yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan 2007 [14] | CMT-Pediatric | Retrospective cohort study | 9 ** | 14 ** | NR | 13.3 ** | NR |

| Galan-Olleros 2025 [15] | Mixed Etiology-Pediatric | Prospective cohort study | 26 ** | 36 ** | 13:13 ** | 12.65 * | NR |

| 6 * | 8 * | 2:4 * | |||||

| Lin 2019 [7] | CMT-Pediatric | Prospective cohort study | 21 ** | 40 ** | 13:8 ** | 12.5 ** | 1.31 ** |

| Mann 1992 [12] | CMT-Pediatric | Retrospective case Series | 10 ** | 12 ** | 6:4 ** | 13.33 ** | 7.58 ** |

| Õunpuu 2025 [8] | CMT-Pediatric | Retrospective cohort study | 19 ** | 29 ** | 11:8 ** | 12.8 ** | 1.6 ** |

| Roper 1989 [16] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective case series | 10 ** | 18 ** | 3:7 ** | 14.0 ** | 14.0 ** |

| 8 * | 16 * | 2:6 * | 11.13 * | 15.75 * | |||

| Sanpera 2018 [9] | Mixed Etiology-Pediatric | Prospective case series | 13 ** | 24 ** | NR | NR | 2.34 ** |

| (Deformity was Neurological in Origin for 7 children) | (13 of Neurological Origin and 11 of Unknown Etiology) | ||||||

| Santavirta 1993 [13] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective cohort study | 15 ** | 26 ** | 6:9 ** | 14.1 * | 14.0 ** |

| 9 * | 15 * | 4:5 * | 16.1 * | ||||

| Simon 2019 [17] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective case series | 20 ** | 26 ** | 10:10 ** | 15.8 ** | 6.2 ** |

| 18 * | 24 * | 9:9 * | 15.1 * | ||||

| Song 2024 [10] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective case series | 29 ** | 29 ** | 13:16 ** | 14.67 * | 0.55 ** |

| 9 * | 9 * | 5:4 * | |||||

| Ward 2008 [5] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective cohort study | 25 ** | 41 ** | 14:11 ** | 15.5 ** | 26.1 ** |

| 21 * | 35 * | 14.1 * | 26 * | ||||

| Weiner 2008 [18] | Mixed Etiology-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective cohort study | 89 ** | 139 ** | 88:51 ** | 9.7 ** | 7.6 ** |

| 5 * | 10 * | 10.88 * | 6.73 * | ||||

| Wicart 2006 [19] | Mixed Etiology-Pediatric | Retrospective case series | 26 ** | 36 ** | 11:15 ** | 10.3 ** | 6.9 ** |

| 16 * | 25 * | 10:6 * | 11.1 * | 6.1 * | |||

| Wukich 1989 [11] | CMT-Pediatric + Adult | Retrospective case series | 22 ** | 34 ** | NR | 16.0 ** | 12.0 ** |

| 18 * | 26 * | 15.4 * | 11.5 * |

| Total Sample Size | |

|---|---|

| Patients | 169 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Patient Statistic | 1 (7.14%), [9] |

| Feet | 276 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Feet Statistic | - |

| Total Male | 62 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Male Gender Statistic | 5 (35.71%) |

| Total Female | 54 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Female Gender Statistic | 5 (35.71%) |

| Mean Age at surgery, year, (range) | 13.46 (5–18) |

| Median Age at surgery | 14 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Data on Age | 3 (21.43%) |

| Mean Length of Follow Up, year, (range) | 13.79 (2–34) |

| Median Length of Follow Up | 9.73 |

| Studies missing Pediatric-CMT Data on Length of Follow up | 7 (50.0%) |

| Study Design | |

| Prospective Cohort Study | 2 (14.29%) |

| Retrospective Cohort Study | 5 (35.71%) |

| Prospective Case Series Study | 1 (7.14%) |

| Retrospective Case Series Study | 6 (42.86%) |

| Study | Approach | Procedure | Patients | Feet (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan 2007 [14] | Reconstruction | Medial Plantar Release | NR | 10 |

| Posterior Tibialis Tendon Transfer | 11 | |||

| Jones Procedure | 2 | |||

| Flexor Digitorum Longus Tenotomy | 2 | |||

| Midfoot Osteotomy | 3 | |||

| First Metatarsal Extension Osteotomy | 3 | |||

| First and Second Metatarsal Extension Osteotomy | 3 | |||

| First to Third Metatarsal Osteotomy | 2 | |||

| Gastrocnemius Recession | 2 | |||

| Plantar Fascia Release | 1 | |||

| Lateral Column Shortening (cuboid) | 1 | |||

| Galan-Olleros 2025 [14] | Reconstruction | Talo-Calcaneo-Navicular Realignment | 6 | 8 |

| Lin 2019 [7] | Fusion & Reconstruction | Plantar fascia release | 17 | NR |

| First metatarsal osteotomy | 18 | |||

| Peroneus longus to brevis transfer | 14 | |||

| Tibialis anterior tendon transfer | 3 | |||

| Strayer calf lengthening | 1 | |||

| Tendon Achilles lengthening | 9 | |||

| Lateral displacement calcaneal osteotomy | 9 | |||

| Jones transfer with interphalangeal joint fusion | 1 | |||

| Tibialis posterior lengthening | 3 | |||

| Tibialis posterior to peroneus brevis transfer | 2 | |||

| Tibialis posterior tendon transfer | 4 | |||

| Split anterior tibialis tendon transfer | 1 | |||

| Second toe proximal interphalangeal joint fusion | 1 | |||

| Lateral closing wedge mid-tarsal osteotomy | 1 | |||

| Lateral closing wedge calcaneal osteotomy | 2 | |||

| Mann 1992 [12] | Fusion | Triple Arthrodesis | 10 | 12 |

| Õunpuu 2025 [8] | Reconstruction | Triceps Surae Lengthening (TSL): | 12 | 19 |

| Gastrocnemius Recession (GR) | 8 | |||

| Tendo Achilles Lengthening (TAL) | 11 | |||

| Plantar Fascia Release + Foot Osteotomy: | 14 | 20 | ||

| Combined with Triceps Surae Lengthening | 10 | |||

| Without Triceps Surae Lengthening | 10 | |||

| Roper 1989 [16] | Reconstruction | Elongation Calcaneal Tendon | 6 | 12 |

| Tibialis Anterior Transfer | 7 | 14 | ||

| Tibialis Posterior Transfer | 1 | 2 | ||

| Steindler Release | 7 | 14 | ||

| Flexor-to-Extensor Transfer | 2 | 4 | ||

| Calcaneal Osteotomy | 1 | 2 | ||

| Robert Jones Procedure | 2 | 4 | ||

| Sanpera 2018 [9] | Reconstruction | Dorsal Hemiepiphysiodesis of the 1st Metatarsal + Plantar Fascia Release | 7 | 13 |

| Santavirta 1993 [13] | Fusion | Triple Arthrodesis | 7 | 12 |

| Grice Arthrodesis | 1 | 1 | ||

| Interphalangeal Fusion of the 1st Toe | 1 | 2 | ||

| Simon 2019 [17] | Reconstruction | Revisited Meary dorsal closing-wedge tarsectomy + Plantar fascia release + Dwyer calcaneal osteotomy + | 18 | 24 |

| First metatarsal extension osteotomy | NR | 16 (not stratified by age) | ||

| Song 2024 [10] | Reconstruction & Fusion | Achilles Triple Hemisection | 9 | 9 |

| Posterior Tibial Tendon Transfer | 8 | 8 | ||

| Talonavicular Joint and Spring Ligament Release | 9 | 9 | ||

| Flexor Digitorum Longus Tenotomy | 6 | 6 | ||

| Plantar Fascia Release | 7 | 7 | ||

| Calcaneal Osteotomy | 7 | 7 | ||

| Peroneus Longus Resection and Transfer to Peroneus Brevis | 9 | 9 | ||

| Closing-Wedge Osteotomy of the 1st Metatarsal | 6 | 6 | ||

| 1st Interphalangeal Joint Fusion | 1 | 1 | ||

| Extensor Tendon Transfer | 3 | 3 | ||

| Flexor Tendon Transfer | 2 | 2 | ||

| Ward 2008 [5] | Reconstruction | Peroneus Longus Transfer to Peroneus Brevis Tendon | 33 | 24 |

| Plantar Fasciotomy | 32 | 23 | ||

| First Metatarsal Dorsiflexion Osteotomy | 29 | 23 | ||

| Extensor Hallucis Longus Recession/Jones procedure | 27 | 20 | ||

| Anterior Tibialis Transfer | 10 | 9 | ||

| Weiner 2008 [18] | Reconstruction | Akron Dome Midfoot Osteotomy (transverse dorsal midfoot approach, two dome-shaped osteotomy cuts, multiplanar correction of cavus/varus/rotation at the deformity apex) | 4 | 11 |

| Wicart 2006 [19] | Reconstruction | Plantar opening-wedge osteotomy of all 3 cuneiforms, Dwyer osteotomy, and selective plantar release + | 16 | NR |

| Medial release | 8 | |||

| Lateral column shortening | 4 | |||

| First metatarsal dorsal wedge osteotomy | 9 | |||

| Wukich 1989 [11] | Fusion | Triple Arthrodesis | 18 | 27 |

3.4. Functional Outcomes

3.5. Radiographic Correction

3.6. Complications and Reoperations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- CMT/Neuropathy Terms

- 1.

- exp Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease/

- 2.

- (Charcot-Marie-Tooth or CMT or hereditary motor sensory neuropathy or HMSN).kf,ti,ab.

- Cavus Foot Deformity

- 3.

- exp Foot Deformities/ or exp Pes Cavus/

- 4.

- (cavus foot or cavovarus or pes cavus or high arch or foot deformit*).kf,ti,ab.

- Pediatric Population

- 5.

- exp Child/ or exp Pediatrics/ or exp Adolescent/

- 6.

- (child* or pediatric* or paediatric* or adolescen* or teen* or young patient*).kf,ti,ab.

- Surgical Intervention: Fusion

- 7.

- exp Arthrodesis/ or exp Joint Fusion/

- 8.

- (arthrodesis or fusion or triple arthrodesis or subtalar fusion or talonavicular fusion or calcaneocuboid fusion).kf,ti,ab.

- Surgical Intervention: Reconstruction

- 9.

- exp Osteotomy/ or exp Tendon Transfer/ or exp Fasciotomy/ or exp Soft Tissue Surgical Procedures/

- 10.

- (reconstruct* or osteotomy or osteotomies or tendon transfer or plantar fascia release or peroneus transfer or Dwyer or Cole or Japas or first metatarsal osteotomy).kf,ti,ab.

- Outcomes

- 11.

- (AOFAS or FFI or SF-36 or PROMIS or Meary* angle or talo-first metatarsal angle or radiographic outcome* or functional outcome* or complication* or reoperation or satisfaction or gait or pain).kf,ti,ab.

- exp Charcot Marie Tooth disease/

- (Charcot-Marie-Tooth or CMT or hereditary motor sensory neuropathy or HMSN).kw,ti,ab.

- exp foot deformity/ or exp pes cavus/

- (cavus foot or cavovarus or pes cavus or high arch or foot deformit*).kw,ti,ab.

- exp child/ or exp adolescent/ or exp pediatrics/

- (child* or pediatric* or paediatric* or adolescen* or teen* or young patient*).kw,ti,ab.

- exp arthrodesis/ or exp joint fusion/

- (fusion or triple arthrodesis or subtalar fusion or talonavicular fusion or calcaneocuboid fusion).kw,ti,ab.

- exp osteotomy/ or exp tendon transfer/ or exp soft tissue surgery/

- (osteotomy or tendon transfer or Dwyer or Japas or plantar fascia release).kw,ti,ab.

- (AOFAS or FFI or SF-36 or PROMIS or Meary* angle or talo-first metatarsal angle or functional outcome* or complication* or reoperation or satisfaction or gait or pain).kw,ti,ab.

Appendix B

| Title | Authors | Published Year | Journal | Reason for Exclusion |

| Treatment of equinocavovarus deformity in adults with the use of a hinged distraction++ apparatus. [26] | Oganesyan, O V; Istomina, I S; Kuzmin, V I | 1996 | The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume | Exclusion reason: Wrong intervention |

| Navicular excision and cuboid closing wedge for severe cavovarus foot deformities: A salvage procedure [27] | Mubarak, S.J.; Dimeglio, A. | 2011 | J. Pediatr. Orthop. | Exclusion reason: Wrong patient population |

| Neuropathic ankle joint in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease after triple arthrodesis of the foot. [28] | Medhat, M A; Krantz, H | 1988 | Orthopaedic review | Exclusion reason: Wrong study design |

| Is there a place for dorsal hemiepiphysiodesis of the first metatarsal in the treatment of pes cavovarus? [29] | Domingues, L.S.; Norte, S.; Thusing, M.; Neves, M.C. | 2025 | J. Pediatr. Orthop. Part B | Exclusion reason: Wrong patient population |

References

- Nagappa, M.; Sharma, S.; Taly, A.B. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Olney, B. TREATMENT OF THE CAVUS FOOT: Deformity in the Pediatric Patient with Charcot-Marie-Tooth. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000, 5, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.S. Reconstruction of Cavus Foot: A Review. Open Orthop. J. 2017, 11, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haupt, E.T.; Porter, G.M.; Blough, C.; Michalski, M.P.; Pfeffer, G.B. Outcomes of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Cavovarus Surgical Reconstruction. Foot Ankle Int. 2024, 45, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, C.M.; Dolan, L.A.; Bennett, D.L.; Morcuende, J.A.; Cooper, R.R. Long-Term Results of Reconstruction for Treatment of a Flexible Cavovarus Foot in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2008, 90, 2631–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Gibbons, P.; Mudge, A.J.; Cornett, K.M.D.; Menezes, M.P.; Burns, J. Surgical Outcomes of Cavovarus Foot Deformity in Children with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2019, 29, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Õunpuu, S.; Pierz, K.A.; Rethlefsen, S.A.; Rodriguez-MacClintic, J.; Acsadi, G.; Kay, R.M.; Wren, T.A.L. Outcomes of Triceps Surae Lengthening Surgery in Children With Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Multisite Investigation. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2025, 45, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanpera, I., Jr.; Frontera-Juan, G.; Sanpera-Iglesias, J.; Corominas-Frances, L. Innovative Treatment for Pes Cavovarus: A Pilot Study of 13 Children. Acta Orthop. 2018, 89, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Michalski, M.P.; Pfeffer, G.B. 3D Analysis of Joint-Sparing Charcot-Marie-Tooth Surgery Effect on Initial Standing Foot Alignment. Foot Ankle Int. 2024, 45, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wukich, D.K.; Bowen, J.R. A Long-Term Study of Triple Arthrodesis for Correction of Pes Cavovarus in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1989, 9, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.C.; Hsu, J.D. Triple Arthrodesis in the Treatment of Fixed Cavovarus Deformity in Adolescent Patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Foot Ankle 1992, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santavirta, S.; Turunen, V.; Ylinen, P.; Konttinen, Y.T.; Tallroth, K. Foot and Ankle Fusions in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 1993, 112, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.; Sampath, J.; Miller, F.; Riddle, E.C.; Nagai, M.K.; Kumar, S.J. The Role of the Dynamic Pedobarograph in Assessing Treatment of Cavovarus Feet in Children With Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2007, 27, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Olleros, M.; Chorbadjian-Alonso, G.; Ramírez-Barragán, A.; Figueroa, M.J.; Fraga-Collarte, M.; Martínez-González, C.; Prato De Lima, C.H.; Martínez-Caballero, I. Talocalcaneonavicular Realignment: The Foundation for Comprehensive Reconstruction of Severe, Resistant Neurologic Cavovarus, and Equinocavovarus Foot Deformities in Children and Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2025, 45, e156–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, B.; Tibrewal, S. Soft Tissue Surgery in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1989, 71-B, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.-L.; Seringe, R.; Badina, A.; Khouri, N.; Glorion, C.; Wicart, P. Long Term Results of the Revisited Meary Closing Wedge Tarsectomy for the Treatment of the Fixed Cavo-Varus Foot in Adolescent with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019, 25, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, D.S.; Morscher, M.; Junko, J.T.; Jacoby, J.; Weiner, B. The Akron Dome Midfoot Osteotomy as a Salvage Procedure for the Treatment of Rigid Pes Cavus: A Retrospective Review. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2008, 28, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicart, P.; Seringe, R. Plantar Opening-Wedge Osteotomy of Cuneiform Bones Combined With Selective Plantar Release and Dwyer Osteotomy for Pes Cavovarus in Children. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2006, 26, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltzman, C.L.; Fehrle, M.J.; Cooper, R.R.; Spencer, E.C.; Ponseti, I.V. Triple Arthrodesis: Twenty-Five and Forty-Four-Year Average Follow-up of the Same Patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1999, 81, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenwasser, K.A.; Judd, H.; Hyman, J.E. Evidence-Based Management Strategies for Pediatric Pes Cavus: Current Concept Review. J. Pediatr. Orthop. Soc. N. Am. 2022, 4, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, T.; Winson, I. Joint Sparing Correction of Cavovarus Feet in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: What Are the Limits? Foot Ankle Clin. 2013, 18, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur Vithran, D.T.; Liu, X.; He, M.; Essien, A.E.; Opoku, M.; Li, Y.; Li, M.-Q. Current Advancements in Diagnosing and Managing Cavovarus Foot in Paediatric Patients. EFORT Open Rev. 2024, 9, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranho, D.A.; Volpon, J.B. Acquired Pes Cavus in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2015, 44, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Wu, S.; Zhang, H. Evaluation and Management of Cavus Foot in Adults: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oganesyan, O.V.; Istomina, I.S.; Kuzmin, V.I. Treatment of Equinocavovarus Deformity in Adults with the Use of a Hinged Distraction Apparatus. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1996, 78, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, S.J.; Dimeglio, A. Navicular Excision and Cuboid Closing Wedge for Severe Cavovarus Foot Deformities: A Salvage Procedure. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2011, 31, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhat, M.A.; Krantz, H. Neuropathic ankle joint in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease after triple arthrodesis of the foot. Orthop Rev. 1988, 17, 873-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Domingues, L.S.; Norte, S.; Thusing, M.; Neves, M.C. Is there a place for dorsal hemiepiphysiodesis of the first metatarsal in the treatment of pes cavovarus? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2025, 34, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Approach) | Functional Outcomes | Radiographic Correction | Complications/ Reoperation Rate | Gait Analysis | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan 2007 (Reconstruction) † [14] | NR | Lateral talus-1st MT: −16.9° → −1.6° (p = 0.001); Lateral calcaneus-1st MT: 121.0° → 135.6° (p = 0.000); Calcaneal pitch: 26.8° → 20.6° (p = 0.000) | NR | [pre-op → post-op] Dynamic pedobarography: Heel 34.5 → 41.9 (p = 0.119, ns); Medial Midfoot (MMF) 2.7 → 0.79 (p = 0.029); Lateral Midfoot (LMF) 35.2 → 23.6 (p = 0.001); Medial Forefoot (MFF) 12.2 → 18.2 (p = 0.146, ns); Lateral Forefoot (LFF) 15.5 → 16.3 (p = 0.716, ns). Compared with lab normals, post-op remained different: Heel ** p = 0.040, MMF ** p = 0.045, MFF ** p = 0.000, LFF ** p = 0.000. Ankle power (6 pts/9 feet): 9.11 → 8.49 W/kg body weight × % gait cycle (p = 0.128); inverse relation with heel pressure (pre-op ** p = 0.548, post-op ** p = 0.056) | NR |

| Galan-Olleros 2025 (Reconstruction) [15] | Functional Outcomes: Significant Improvements Pre-median (IQR), post-median (IQR), change-median (IQR), p-value, respectively: FADI: 41 (36), 90 (10), 38 (26), p < 0.001 FFI: 125 (28), 39 (31), −85 (41), p < 0.001 MFS: 46 (14), 78 (10), 31 (10), p < 0.001 | Radiologic Parameters: Significant Improvements Pre-median (IQR), post-median (IQR), change-median (IQR), p-value, respectively: Talocalcaneal angle: −1.3 (19.5), 17.6 (14.2), 17.5 (18.5), p < 0.001 Talo-1st MT angle: −46.4 (19.8), −9.3 (11), 31.0 (18.5), p < 0.001 Talonavicular coverage angle: −39.8 (17.3), 0.3 (9), 34.2 (19.5), p < 0.001 | NR | NR | Surgical results: High levels of satisfaction amongst most patients Significant outcomes; exceeded expectations Majority of patients further recommended the surgery and would undergo it again if ever needed |

| Lin 2019 (Fusion & Reconstruction) † [7] | Pre-operative mean, post-operative mean, significance, p-value, respectively: Foot Alignment via FPI: −7.4 (SD 2.6), −1.5 (SD 3.3), significant improvement, p < 0.001 Ankle Flexibility via Lunge Test: 16.7° (SD 7.1°), 22.7° (SD 3.7°), significant improvement, p = 0.003 Strength, Balance, Long Jump, and 6 min walk test: No Significant difference between pre- and post-operation Overall Disability via CMTPedS: Non-significant worsening, pre-operative mean 21.8 (SD 7.3), post-operative mean 23.7 (SD 9.4) | NR | No complications seen across all osteotomies 1 patient underwent a second surgery 2.5 years later due to dynamic supination during walking | NR | Daily trips/falls significantly decreased from 9/15 (60%) to 2/15 (13%) (p = 0.016), foot pain lessened from 9/15 (60%) to 7/15 (47%) (p = 1.000), leg cramps increased from 3/15 (20%) to 6/15 (40%) (p = 0.375), and unsteady ankles decreased from 10/15 (67%) to 9/15 (60%) (p = 1.000) Parent/proxy-reported child health questionnaire (n = 13): Physical and psychosocial domain scores: No significant difference between pre- and post-op (p > 0.05) |

| Mann 1992 (Fusion) † [12] | Plantigrade: 8 feet 1 foot became plantigrade after final Triple Arthrodesis revision Nonplantigrade: 3 feet | 9 feet had fusion at all three joints 2 feet presented nonunion of the talonavicular joint 4 years and 12 years post-operation 1 foot presented calcaneocuboid nonunion 2 years post-operation | Pseudoarthrosis: 3 feet (2 had talonavicular pseudoarthrosis, and 1 had calcaneocuboid pseudoarthrosis) Triple Arthrodesis revision: 1 foot | NR | 9 feet: Clinically asymptomatic (no pain or callosities, all feet came to neutral dorsiflexion and possessed a neutral hindfoot and forefoot) 3 feet: Clinically symptomatic secondary to residual deformity (callosities under the fifth metatarsal head, all feet required molded ankle-foot orthoses) |

| Õunpuu 2025 (Reconstruction) † [8] | FPI-3: Significant change with and without TSL (p < 0.05) -> Reduced cavovarus with mean change of +2.5 with TSL and +1.9 without TSL | NR | NR | TSL Significantly less dorsiflexion in terminal stance in limbs undergoing TAL than limbs undergoing GR, pre-operatively (TAL −6.2° vs. GR 5.2°, p = 0.043) Significant increase pre-operation to post-operation in passive dorsiflexion range of motion, peak dorsiflexion in terminal stance and peak dorsiflexion in mid-swing, with both GR and TAL Significant increase in peak plantar flexor moment with both GR and TAL (p < 0.02) No significant change in peak plantar flexor power with both GR and TAL (p > 0.09) No significant change in dorsiflexor or plantar flexor strength with both GR and TAL (p ≥ 0.16) No significant differences between GR and TAL across any kinetic or kinematic variables, post-operatively PFR & Foot Osteotomy Limbs with TSL possessed less dorsiflexion range of motion (p < 0.02) and were more plantar-flexed during mid-swing (p = 0.02) compared to limbs without TSL, pre-operatively. Significant increase in dorsiflexion post-operatively including TSL passively (p < 0.001) during terminal stance (p = 0.02) and mid-swing (p = 0.001). No significant change observed when operation excluded TSL (p 0.06) Post-operative increase in peak plantar flexor moment and power when operation included TSL (p < 0.04). No increase observed when surgery excluded TSL (p > 0.13) No significant change in dorsiflexor or plantar flexor strength post-operatively with or without TSL (p ≥ 0.08) | TSL Post-operatively, walking speed commonly decreased amongst patients (p = 0.07) PFR & Foot Osteotomy Decrease in walking speed and stride length after plantar fasciotomy without TSL (p ≤ 0.001) Decrease in walking speed after surgery with TSL (p = 0.07) |

| Roper 1989 (Reconstruction) [16] | All patients able to walk unlimited distances | NR | Across all patients no significant problems were observed post-operation | NR | All patients achieved satisfactory results |

| Sanpera 2018 (Reconstruction) [9] | OXAFQ-C (n = 7): Physical 15 → 21, mean diff −5.9 (95% CI −9.2 to −2.5); School/Play 9 → 13, mean diff −3.4 (95% CI −7.4 to −0.6); Emotional 12 → 14, mean diff −2.4 (95% CI −5.2 to 0.4). p-values NR. Footwear usability 1.3 → 3.5/4 (reported improvement). | Right foot: Meary angle −6.8° (95% CI −9.4 to −4.5); Talus–1st MT angle −8.2° (95% CI −12.5 to −4.0); Calcaneal pitch angle −3.6° (95% CI −5.8 to −1.4). Left foot: Meary angle −7.1° (95% CI −10.3 to −4.4); Talus–1st MT angle −9.2° (95% CI −16.3 to −3.7); Calcaneal pitch angle: −2.2° (95% CI −4.5 to 0.2). p-values NR; CIs all include 0 except left calcaneal pitch | 3 surgical complications: 2 malpositioned proximal screws (both reoperated to reposition), 1 plate rupture 2 screw-reposition surgeries (See complications) | NR | All feet improved clinically; heel varus shifted toward valgus (mean clinical correction ≈10°, CI excludes 0). |

| Santavirta 1993 (Fusion) [13] | NR | NR | Triple arthrodesis: nonunion 3 + delayed union 1 (4/21); malposition requiring subtalar osteotomy/refusion 2. Pantalar fusion: nonunion 1. Refusions for failed triple: 4 feet (union achieved in 3/4). Talocrural fusion after triple: 2 cases. Any additional operations beyond index fusion: 17/26 feet; 5 feet had 3–4 further procedures. | NR | Most outcomes judged good/excellent. Patients generally felt they benefited. Walking distance not significantly improved. |

| Simon 2019 (Reconstruction) [17] | AOFAS (subset, 10 feet) median [IQR]: hindfoot = 95.5 [84.3–97.8]; midfoot = 75 [61.5–80]; hallux = 100 [95,96,97,98,99,100]; lesser toes = 92 [91.5–94]. Majority (58% of feet) rated very good/good by WS score. | Meary: 16.7° (pre-op) → −1.4° (post-op) (p < 0.0001); Calcaneal pitch: 23.6° → 12.5° (p < 0.0001); Talo-calcaneal angle: 20.5° → 26.8° (p = 0.01); Talo–1st MT (TM1): 20.7° → 8.1° (p = 0.0007); Stacking angle: 23.9° → 14.9° (p < 0.0001); CM5 (calcaneus–5th MT): 14.9° → 7.3° (p = 0.0003). | Overcorrection (flatfoot): 6 feet (4 patients, 23%); skin necrosis: 1; no nonunion reported 3/26 feet (11.5%) required further surgery: 1 conversion to triple arthrodesis (after wound necrosis), 1 delayed first-met osteotomy, 1 hardware removal. | NR | NR |

| Song 2024 (Reconstruction & Fusion) [10] | NR | WBCT (3D): Sagittal Meary 14.8° (pre-op) → 0.1° (post-op) (p < 0.001); Axial talonavicular angle 3.6° → 19.2° (p < 0.001); Coronal hindfoot (Saltzman) 11.0° → −11.1° (p < 0.001); multiple forefoot IMAs/TMAs also improved; several parameters approached normative values | 1 revision surgery for hindfoot overcorrection | NR | NR |

| Ward 2008 (Reconstruction) [5] | SF-36: PCS 37.7 (range 17.3–59.5), MCS 49.8 (20.5–65.8). FFI means: Pain 35.0, Disability 40.5, Activity 22.1. Smokers had worse FFI domains (p < 0.0001) and lower PCS (p = 0.0003). Patients who later required additional surgery had lower MCS (40.2 vs. 51.5; p = 0.024) and worse FFI Disability (59.3 vs. 37.7; p = 0.002) and Activity (39.1 vs. 19.5; p = 0.021). | Long-term alignment maintained; hindfoot varus commonly recurred. Study-group values: Meary (talo–1st MT) 6.2° ± 4.32°; calcaneal–1st MT 128.9° ± 5.4°; calcaneal inclination 25.3° ± 3.3°; navicular height:foot length 0.30 ± 0.03; hindfoot varus 15.9 ± 9.9 mm. Feet needing secondary surgery had higher calcaneal–1st MT (136.3° vs. 128.0°; p = 0.009) and lower Meary (0.7° vs. 7.0°; p = 0.014) | 7 patients (8 feet) had 11 subsequent procedures; no conversion to triple arthrodesis. | Slower than normals; longer double-support. TA transfer associated with less double-support time (p = 0.014) | NR |

| Weiner 2008 (Reconstruction) [18] | NR | NR | Complications were uncommon/insignificant Average number of surgeries performed after the Akron dome midfoot osteotomy was 0.6 in the satisfactory group and 1.8 in the unsatisfactory group All unsatisfactory results were secondary to recurrences of deformity and were addressed through repeated midfoot osteotomies (except for 2 cases) | NR | Post-operatively, 106 cases were classified as satisfactory and 33 as unsatisfactory 10 satisfactory results across CMT-diagnosed patients 3 unsatisfactory results across CMT-diagnosed patients “Satisfactory”: (a) Min. 75% plantigrade foot facing the floor (b) Pain-free foot without abnormal pressure areas (c) Foot does not have any significant midfoot deformity requiring surgical or orthotic intervention (d) Return to daily activities such as walking, running and leisure-time activities without requiring customized or adaptive shoe wear |

| Wicart 2006 (Reconstruction) [19] | Post-operatively 18/25 feet: “correct” function, 7/25 feet: “bad” function † Post-operatively 4/25 feet had very good results, 12/25 feet had good results, 1/25 feet had fair results, & 8/25 feet had poor results † Very Good: No functional symptoms. 0° Meary angle 15° and valgus or 5° Meary angle 20° and neutral or varus Good: No functional symptoms. 15° < Meary angle 20° and valgus or 5° < Meary angle 20° and neutral or 5° < Meary angle 15° and varus or −15 Meary angle < 0° (minor overcorrection) Fair: No functional symptoms. Meary angle > 20° and valgus or neutral or Meary angle > 15° and varus or Meary angle < −15° (major overcorrection) Poor: Pain and/or sprain. Recurrence of the deformity requiring triple arthrodesis Post-operatively 5/25 feet had “valgus” hindfoot axis, 12/25 feet had “varus” hindfoot axis, & 8/25 feet had “neutral” hindfoot axis † | Post-operative Meary Angle Average: 6.44° † Final follow-up Meary angle Average: 14.28° † | No pain or ankle sprains reported 11/25 feet had revisions: 8 feet had Triple Arthrodesis, 2 feet had subtalar and midtarsal joints release, & 1 foot had 1st MT osteotomy † | NR | NR |

| Wukich 1989 (Fusion) [11] | 21/22 patients able to ambulate post-op: 16 able to walk > 800 m without braces, & 5 able to walk between 400 and 800 m (2 of them without braces) Objective Evaluation 11 feet = “Good” 19 feet = “Fair” 4 feet = “Poor” “Good”: No/minimal pain, no/minimal deformity, no callosities, no pseudarthrosis, & no joint degeneration “Fair”: Pain after light use, moderate deformity, single callosity, single pseudarthrosis, & mild joint degeneration “Poor”: Pain on standing or at rest, severe deformity, multiple callosities, multiple pseudarthroses, & severe joint degeneration Functional Evaluation 6 feet = “Excellent” 24 feet = “Good” 2 feet = “Fair” 2 feet = “Poor” “Excellent”: Ambulatory, free of brace, pain-free “Good”: Mild symptoms and deformity, no braces “Fair”: Ambulatory, but requires braces “Poor”: Nonambulatory because of feet | Passive ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion arc exceeded 30° in 21/22 patients (32 ankles) 15 patients (25 ankles) were able to actively dorsiflex their ankles to within 5° of the neutral position (Posterior tibial tendon transfers in 12 of these feet) Mild medial to lateral ankle instability with talar tilt angles of 5–17° in 3 patients (4 ankles) | Post-op pain (24 feet): Foot only (12), Ankle only (2), Foot & Ankle (10) Pain Severity: Mild in 18 feet (no nonnarcotic medication), Moderate in 5 feet (occasional nonnarcotic medication), & Severe in 1 foot (regular nonnarcotic medication) 19 feet had plantar callosities post-op: 15 had a single callus, & 4 had multiple callosities 15/34 feet had residual deformity post-op: 10 had cavus deformities, 1 had varus deformity, & 4 had cavovarus deformities Overcorrection of 5 feet into planovalgus deformities Undercorrection or overcorrection in 60% of feet Clawing of toes in 22 feet 5 feet presented pseudoarthrosis of the talonavicular joint No observed pseudoarthrosis of the talocalcaneal or calcaneocuboid joints Degenerative joint changes observed in 8 ankles (5 = mild, 2 = moderate, 1 = severe), and midfoot of 21 feet (18 = mild, 2 = moderate) 9 patients altogether underwent 12 additional surgical procedures including triple arthrodesis and bunionette surgery | NR | Post-operatively 19/22 patients (31/34 feet) were satisfied Pre-operatively 11/22 patients wore braces. Post-operatively only 3 patients (4 feet) needed a brace |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kishta, W.; Gaber, K.; Li, Z.; Helal, B.; Wariach, K.; Ibrahim, A.; Onesi, J. Outcomes of Primary Fusion vs. Reconstruction of Pediatric Cavus Foot in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Systematic Review. Osteology 2025, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040036

Kishta W, Gaber K, Li Z, Helal B, Wariach K, Ibrahim A, Onesi J. Outcomes of Primary Fusion vs. Reconstruction of Pediatric Cavus Foot in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Systematic Review. Osteology. 2025; 5(4):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040036

Chicago/Turabian StyleKishta, Waleed, Karim Gaber, Zhi Li, Bahaaldin Helal, Khubaib Wariach, Ahmad Ibrahim, and Juliana Onesi. 2025. "Outcomes of Primary Fusion vs. Reconstruction of Pediatric Cavus Foot in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Systematic Review" Osteology 5, no. 4: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040036

APA StyleKishta, W., Gaber, K., Li, Z., Helal, B., Wariach, K., Ibrahim, A., & Onesi, J. (2025). Outcomes of Primary Fusion vs. Reconstruction of Pediatric Cavus Foot in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Systematic Review. Osteology, 5(4), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040036