The Effect of Age and Symptom Duration on Patient-Reported Outcomes at 2- and 5-Year Follow-Up in Patients Undergoing Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

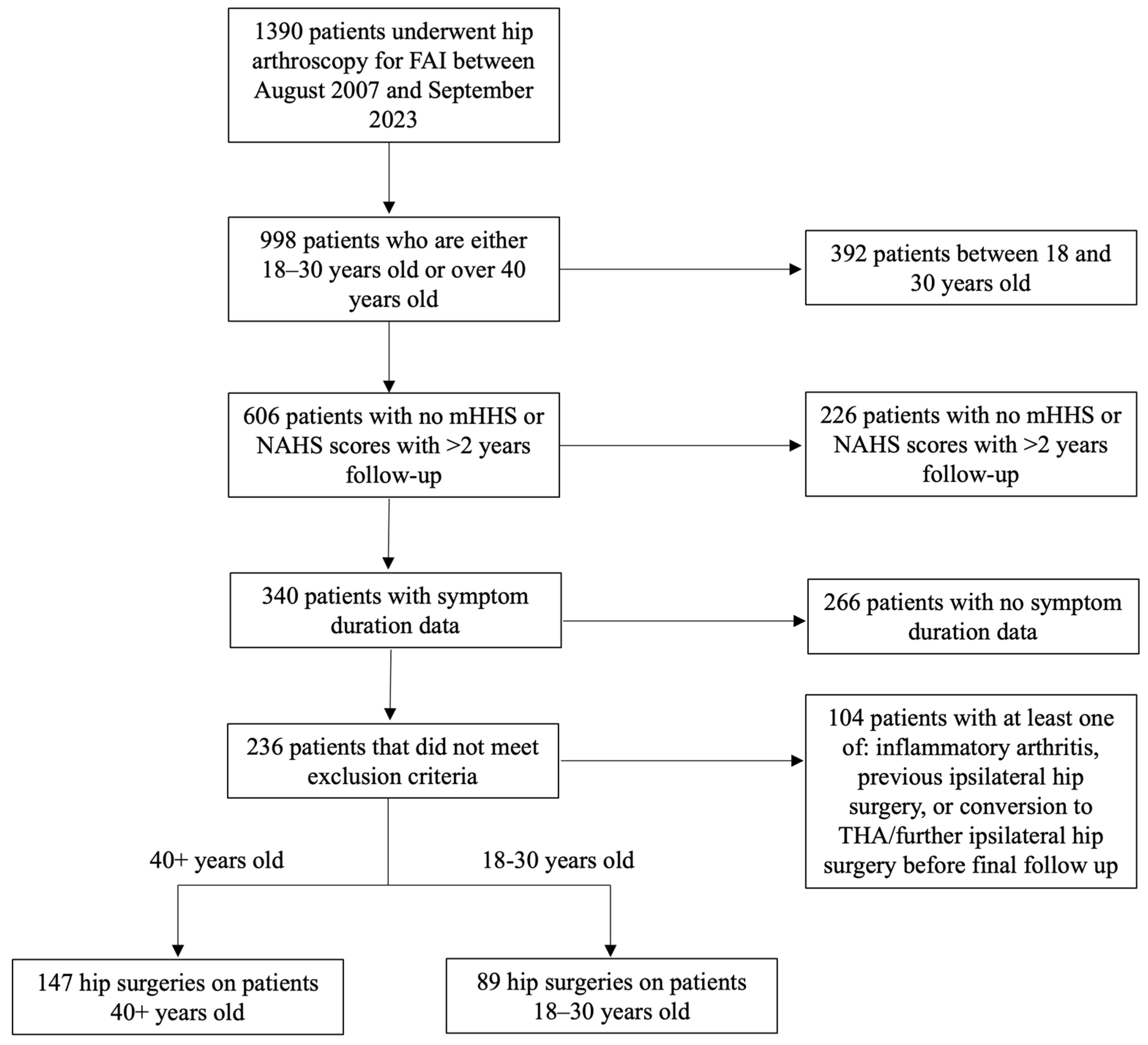

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Diagnostic Criteria and Surgical Indications

2.4. Surgical Technique and Postoperative Protocol

2.5. Outcomes Measured

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Surgical Characteristics

3.3. Patient-Reported Outcomes in 18–30 Year Cohort with Symptom Duration ≤ 1 Year Versus 40+ Year Cohort with Symptom Duration ≥ 1 Year

3.4. Patient-Reported Outcomes in 18–30 Versus 40+ Year Cohorts (Isolated Age Analysis)

3.5. Outcomes in Patients with Symptom Duration ≥ 1 Year Versus Those with Symptom Duration < 1 Year (Isolated Symptom Duration Analysis)

3.6. Symptom Duration and Clinical Outcomes in 18–30 Versus 40+ Year Cohorts

3.7. Linear Regression Analysis for mHHS and NAHS

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolfson, T.S.; Ryan, M.K.; Begly, J.P.; Youm, T. Outcome Trends After Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement: When Do Patients Improve? Arthroscopy 2019, 35, 3261–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.D.; Abraham, P.F.; Varady, N.H.; Nazal, M.R.; Conaway, W.; Quinlan, N.J.; Alpaugh, K. Hip Arthroscopy Versus Physical Therapy for the Treatment of Symptomatic Acetabular Labral Tears in Patients Older Than 40 Years: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, D.A.; Hurley, E.T.; Fariyike, B.; Akpinar, B.; Haskel, J.D.; Grapperhaus, S.A.; Youm, T. Age-Associated Functional Outcomes Following Hip Arthroscopy in Females Analysis with 5-Year Follow-Up. Bull. Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2022, 80, 230–235. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36403951 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Frank, R.M.; Lee, S.; Bush-Joseph, C.A.; Salata, M.J.; Mather, R.C., 3rd; Nho, S.J. Outcomes for Hip Arthroscopy According to Sex and Age: A Comparative Matched-Group Analysis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2016, 98, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.J.; Akpinar, B.; Bloom, D.A.; Youm, T. Age and Outcomes in Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement: A Comparison Across 3 Age Groups. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprato, A.; Jayasekera, N.; Villar, R. Timing in hip arthroscopy: Does surgical timing change clinical results? Int. Orthop. 2012, 36, 2231–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.N.; Lee, M.S.; Mahatme, R.J.; Gillinov, S.M.; Islam, W.; Fong, S.; Lee, A.Y.; Abu, S.; Pettinelli, N.; Medvecky, M.J.; et al. Short Symptom Duration Is Associated with Superior Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Primary Hip Arthroscopy: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy 2023, 39, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogbein, O.A.; Shah, A.; Kay, J.; Memon, M.; Simunovic, N.; Belzile, E.L.; Ayeni, O.R. Predictors of Outcomes After Hip Arthroscopic Surgery for Femoroacetabular Impingement: A Systematic Review. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2019, 7, 2325967119848982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basques, B.A.; Waterman, B.R.; Ukwuani, G.; Beck, E.C.; Neal, W.H.; Friel, N.A.; Stone, A.V.; Nho, S.J. Preoperative Symptom Duration Is Associated With Outcomes After Hip Arthroscopy. Am. J. Sports Med. 2019, 47, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, K.N.; Beck, E.C.; Nwachukwu, B.U.; Ahn, J.; Nho, S.J. Early Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome Provides Superior Outcomes When Compared with Delaying Surgical Treatment Beyond 6 Months. Am. J. Sports Med. 2019, 47, 2038–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, J.L.; MacDonald, D.; Collins, N.J.; Hatton, A.L.; Crossley, K.M. Hip arthroscopy in the setting of hip osteoarthritis: Systematic review of outcomes and progression to hip arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2015, 473, 1055–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardakos, N.V.; Villar, R.N. Predictors of progression of osteoarthritis in femoroacetabular impingement: A radiological study with a minimum of ten years follow-up. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2009, 91, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, M.J.; Jan, K.; Kazi, O.; Wright-Chisem, J.; Nho, S.J. The Association of Preoperative Hip Pain Duration With Delayed Achievement of Clinically Significant Outcomes After Hip Arthroscopic Surgery for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome. Am. J. Sports Med. 2024, 52, 2565–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippon, M.J.; Schroder, E.S.B.G.; Briggs, K.K. Hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in patients aged 50 years or older. Arthroscopy 2012, 28, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadinsky, N.E.; Klinger, C.E.; Sculco, P.K.; Helfet, D.L.; Lorich, D.G.; Lazaro, L.E. Femoral Head Vascularity: Implications Following Trauma and Surgery About the Hip. Orthopedics 2019, 42, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leunig, M.; Beck, M.; Woo, A.; Dora, C.; Kerboull, M.; Ganz, R. Acetabular rim degeneration: A constant finding in the aged hip. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2003, 413, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippon, M.J.; Arnoczky, S.P.; Torrie, A. Arthroscopic repair of the acetabular labrum: A histologic assessment of healing in an ovine model. Arthroscopy 2007, 23, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Leunig, M.; Ganz, R. Histopathologic features of the acetabular labrum in femoroacetabular impingement. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2004, 429, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poultsides, L.A.; Bedi, A.; Kelly, B.T. An algorithmic approach to mechanical hip pain. HSS J. 2012, 8, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, H.P.; Mc Auliffe, S.; Ardern, C.L.; Kemp, J.L.; Mosler, A.B.; Price, A.; Blazey, P.; Richards, D.; Farooq, A.; Serner, A.; et al. Oxford consensus on primary cam morphology and femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: Part 1-definitions, terminology, taxonomy and imaging outcomes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 57, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramisetty, N.; Kwon, Y.; Mohtadi, N. Patient-reported outcome measures for hip preservation surgery-a systematic review of the literature. J. Hip Preserv. Surg. 2015, 2, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, D.A.; Kaplan, D.J.; Mojica, E.; Strauss, E.J.; Gonzalez-Lomas, G.; Campbell, K.A.; Alaia, M.J.; Jazrawi, L.M. The Minimal Clinically Important Difference: A Review of Clinical Significance. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahal, J.; Van Thiel, G.S.; Mather, R.C., 3rd; Lee, S.; Song, S.H.; Davis, A.M.; Salata, M.; Nho, S.J. The Patient Acceptable Symptomatic State for the Modified Harris Hip Score and Hip Outcome Score Among Patients Undergoing Surgical Treatment for Femoroacetabular Impingement. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015, 43, 1844–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwachukwu, B.U.; Chang, B.; Adjei, J.; Schairer, W.W.; Ranawat, A.S.; Kelly, B.T.; Nawabi, D.H. Time Required to Achieve Minimal Clinically Important Difference and Substantial Clinical Benefit After Arthroscopic Treatment of Femoroacetabular Impingement. Am. J. Sports Med. 2018, 46, 2601–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosinsky, P.J.; Kyin, C.; Maldonado, D.R.; Shapira, J.; Meghpara, M.B.; Ankem, H.K.; Lall, A.C.; Domb, B.G. Determining Clinically Meaningful Thresholds for the Nonarthritic Hip Score in Patients Undergoing Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome. Arthroscopy 2021, 37, 3113–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.A.; Fried, J.W.; Bi, A.S.; Kaplan, D.J.; Chintalapudi, N.; Youm, T. Age-Associated Pathology and Functional Outcomes After Hip Arthroscopy in Female Patients: Analysis With 2-Year Follow-up. Am. J. Sports Med. 2020, 48, 3265–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierckman, B.D.; Ni, J.; Hohn, E.A.; Domb, B.G. Does duration of symptoms affect clinical outcome after hip arthroscopy for labral tears? Analysis of prospectively collected outcomes with minimum 2-year follow-up. J. Hip Preserv. Surg. 2017, 4, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, J.W.; Jones, K.S. Prospective analysis of hip arthroscopy with 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy 2000, 16, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, D.S.; Shaw, D.B.; Wolff, A.B.; Christoforetti, J.J.; Salvo, J.P.; Kivlan, B.R.; Matsuda, D.K. Symptom duration predicts inferior mid-term outcomes following hip arthroscopy. Int. Orthop. 2022, 46, 2837–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, M.; Ahlden, M.; Jonasson, P.; Thomee, C.; Sward, L.; Ohlin, A.; Baranto, A.; Karlsson, J.; Thomee, R. Outcome after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in 289 patients with minimum 2-year follow-up. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 27, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, K.N.; Nwachukwu, B.U.; Beck, E.C.; Chahla, J.; Gowd, A.K.; Rasio, J.; Nho, S.J. Preoperative Duration of Symptoms Is Associated With Outcomes 5 Years After Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome. Arthroscopy 2020, 36, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devin, C.J.; McCullough, K.A.; Morris, B.J.; Yates, A.J.; Kang, J.D. Hip-spine syndrome. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2012, 20, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardo, L.; Parimi, N.; Liu, F.; Lee, S.; Jungmann, P.M.; Nevitt, M.C.; Link, T.M.; Lane, N.E. Femoroacetabular Impingement: Prevalent and Often Asymptomatic in Older Men: The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2015, 473, 2578–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, D.C.; Feeley, B.T.; Tay, B.; Vail, T.P.; Zhang, A.L. Age-Related Trends in Hip Arthroscopy: A Large Cross-Sectional Analysis. Arthroscopy 2015, 31, 2307–2313.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, M.J.; Soriano, K.K.J.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Monroe, E.J.; Wong, S.E.; Zhang, A.L. Patient-Reported Outcome Surveys for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome Demonstrate Strong Correlations, High Minimum Clinically Important Difference Agreement and Large Ceiling Effects. Arthroscopy 2022, 38, 2829–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 40+ Years (n = 147) | 18–30 Years (n = 89) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 52.1 ± 8.7 | 25.5 ± 3.4 | <0.001 |

| Sex | F: 70.7% M: 29.3% | F: 58.4% M: 41.6% | 0.053 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.2 ± 5.1 | 24.7 ± 4.1 | 0.020 |

| Variable | 40+ Years (n = 147) | 18–30 Years (n = 89) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical Characteristics | |||

| Impingement Type | 0.22 | ||

| Pincer Only | 9 | 3 | |

| Cam Only | 3 | 1 | |

| Mixed | 135 | 85 | |

| Labral Procedure | 0.55 | ||

| Repair | 133 | 84 | |

| Debridement | 8 | 2 | |

| Reconstruction | 5 | 3 | |

| Chondral Status (Outerbridge) | |||

| Acetabulum grade | |||

| 0 | 4 (2.7%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0.72 |

| 1 | 36 (24.5%) | 28 (31.5%) | |

| 2 | 42 (47.2%) | 42 (47.2%) | |

| 3 | 12 (16.3%) | 12 (13.5%) | |

| 4 | 13 (8.8%) | 5 (5.6%) | |

| Femoral head grade II–IV | |||

| 0 | 134 (91.2%) | 89 (100%) | 0.08 |

| 1 | 6 (4.1%) | 0 | |

| 2 | 3 (2.0%) | 0 | |

| 3 | 3 (2.0%) | 0 | |

| 4 | 1 (0.7%) | 0 |

| Variable | 40+ Years with ≥1 Year Symptom Duration (n = 45) | 18–30 Years with ≤1 Year Symptom Duration (n = 17) | p-Value |

| mHHS at pre-op | 52.4 ± 14.2 | 59.9 ± 9.0 | 0.048 |

| mHHS at 2-year follow-up | 85.0 ± 16.8 | 92.1 ± 8.1 | 0.103 |

| Change in mHHS at 2-year follow-up | 32.6 ± 16.2 | 32.2 ± 13.9 | 0.925 |

| Achieved MCID | 95.6% | 94.1% | 0.814 |

| Achieved SCB | 82.2% | 76.5% | 0.609 |

| Achieved PASS | 80.0% | 94.1% | 0.178 |

| Variable | 40+ Years with ≥1 year symptom duration (n = 46) | 18–30 Years with ≤1 year symptom duration (n = 16) | p-value |

| NAHS at pre-op | 49.2 ± 13.0 | 52.5 ± 13.6 | 0.127 |

| NAHS at 2-year follow-up | 82.0 ± 18.5 | 90.3 ± 18.8 | 0.130 |

| Change in NAHS at 2-year follow-up | 32.8 ± 19.9 | 37.8 ± 18.1 | 0.382 |

| Achieved MCID | 89.1% | 87.5% | 0.859 |

| Achieved SCB | 52.2% | 75.0% | 0.111 |

| Achieved PASS | 58.7% | 87.5% | 0.036 |

| Variable | 40+ Years with ≥1 Year Symptom Duration (n = 50) | 18–30 Years with ≤1 Year Symptom Duration (n = 15) | p-Value |

| mHHS at pre-op | 49.9 ± 14.7 | 67.6 ± 14.0 | <0.001 |

| mHHS at 5-year follow-up | 83.0 ± 14.7 | 90.5 ± 10.1 | 0.070 |

| Change in mHHS at 5-year follow-up | 33.1 ± 17.6 | 22.9 ± 15.8 | 0.048 |

| Achieved MCID | 86.0% | 86.7% | 0.948 |

| Achieved SCB | 78.0% | 60.0% | 0.164 |

| Achieved PASS | 80.0% | 93.3% | 0.227 |

| Variable | 40+ Years with ≥1 year symptom duration (n = 53) | 18–30 Years with ≤1 year symptom duration (n = 15) | p-value |

| NAHS at pre-op | 46.7 ± 10.1 | 62.8 ± 11.0 | 0.007 |

| NAHS at 5-year follow-up | 82.1 ± 19.3 | 90.9 ± 11.0 | 0.098 |

| Change in NAHS at 5-year follow-up | 35.4 ± 24.2 | 28.1 ± 19.8 | 0.297 |

| Achieved MCID | 83.0% | 93.3% | 0.319 |

| Achieved SCB | 64.2% | 46.7% | 0.222 |

| Achieved PASS | 60.4% | 73.3% | 0.358 |

| Variable | 40+ Years (n = 70) | 18–30 Years (n = 33) | p-Value |

| mHHS at pre-op | 52.8 ± 13.6 | 61.4 ± 12.3 | <0.001 |

| mHHS at 2-year follow-up | 85.1 ± 16.8 | 92.7 ± 8.9 | 0.019 |

| Change in mHHS at 2-year follow-up | 32.3 ± 16.8 | 31.3 ± 15.8 | 0.787 |

| Achieved MCID | 91.4% | 90.1% | 0.931 |

| Achieved SCB | 78.6% | 72.7% | 0.513 |

| Achieved PASS | 78.6% | 93.9% | 0.050 |

| Variable | 40+ Years (n = 72) | 18–30 Years (n = 33) | p-value |

| NAHS at pre-op | 50.4 ± 15.1 | 54.0 ± 14.0 | 0.007 |

| NAHS at 2-year follow-up | 83.5 ± 18.3 | 91.4 ± 14.2 | 0.030 |

| Change in NAHS at 2-year follow-up | 33.1 ± 19.3 | 37.4 ± 20.7 | 0.309 |

| Achieved MCID | 87.5% | 87.9% | 0.956 |

| Achieved SCB | 62.5% | 66.7% | 0.680 |

| Achieved PASS | 66.7% | 81.8% | 0.111 |

| Variable | 40+ Years (n = 69) | 18–30 Years (n = 36) | p-Value |

| mHHS at pre-op | 48.9 ± 18.5 | 63.3 ± 11.7 | 0.005 |

| mHHS at 5-year follow-up | 81.2 ± 18.5 | 89.8 ± 11.7 | 0.013 |

| Change in mHHS at 5-year follow-up | 32.3 ± 20.7 | 26.5 ± 14.7 | 0.142 |

| Achieved MCID | 84.1% | 91.7% | 0.276 |

| Achieved SCB | 76.8% | 69.4% | 0.412 |

| Achieved PASS | 73.9% | 91.7% | 0.031 |

| Variable | 40+ Years (n = 71) | 18–30 Years (n = 34) | p-value |

| NAHS at pre-op | 46.9 ± 21.4 | 60.4 ± 11.3 | 0.006 |

| NAHS at 5-year follow-up | 81.4 ± 21.4 | 90.3 ± 11.3 | 0.024 |

| Change in NAHS at 5-year follow-up | 34.5 ± 24.9 | 29.9 ± 14.9 | 0.326 |

| Achieved MCID | 80.3% | 97.1% | 0.022 |

| Achieved SCB | 63.4% | 55.9% | 0.461 |

| Achieved PASS | 62.0% | 76.5% | 0.140 |

| Variable | Symptom Duration ≥ 1 Year (n = 70) | Symptom Duration < 1 Year (n = 33) | p-Value |

| mHHS at pre-op | 55.6 ± 14.0 | 55.3 ± 14.7 | 0.902 |

| mHHS at 2-year follow-up | 87.7 ± 15.1 | 87.3 ± 15.4 | 0.918 |

| Change in mHHS at 2-year follow-up | 31.5 ± 16.5 | 32.8 ± 16.5 | 0.715 |

| Achieved MCID | 92.9% | 87.9% | 0.404 |

| Achieved SCB | 75.7% | 78.8% | 0.731 |

| Achieved PASS | 84.3% | 81.8% | 0.753 |

| Variable | Symptom Duration ≥ 1 year (n = 70) | Symptom Duration < 1 Year (n = 35) | p-value |

| NAHS at pre-op | 53.3 ± 15.2 | 53.3 ± 16.8 | 0.982 |

| NAHS at 2-year follow-up | 85.9 ± 16.5 | 86.1 ± 19.5 | 0.945 |

| Change in NAHS at 2-year follow-up | 34.4 ± 18.5 | 34.5 ± 18.5 | 0.978 |

| Achieved MCID | 88.6% | 85.7% | 0.675 |

| Achieved SCB | 55.7% | 80.0% | 0.015 |

| Achieved PASS | 67.1% | 80.0% | 0.169 |

| Variable | Symptom Duration ≥ 1 Year (n =75) | Symptom Duration < 1 Year (n = 30) | p-Value |

| mHHS at pre-op | 55.6 ± 14.0 | 55.3 ± 14.7 | 0.902 |

| mHHS at 5-year follow-up | 85.5 ± 14.3 | 80.9 ± 22.1 | 0.295 |

| Change in mHHS at 5-year follow-up | 31.1 ± 17.2 | 28.3 ± 22.9 | 0.557 |

| Achieved MCID | 88.0% | 83.3% | 0.525 |

| Achieved SCB | 74.7% | 74.7% | 0.888 |

| Achieved PASS | 84.0% | 80.0% | 0.105 |

| Variable | Symptom Duration ≥ 1 year (n =76) | Symptom Duration < 1 Year (n = 29) | p-value |

| NAHS at pre-op | 53.3 ± 15.2 | 53.3 ± 16.8 | 0.982 |

| NAHS at 5-year follow-up | 84.6 ± 17.8 | 83.4 ± 22.6 | 0.798 |

| Change in NAHS at 5-year follow-up | 33.4 ± 22.0 | 32.1 ± 22.8 | 0.799 |

| Achieved MCID | 86.8% | 82.8% | 0.593 |

| Achieved SCB | 61.8% | 58.6% | 0.762 |

| Achieved PASS | 65.8% | 69.0% | 0.758 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moore, M.; Montgomery, S.R.; Chen, L.; Lehman, A.; Levitt, S.; Kaplan, D.J.; Youm, T. The Effect of Age and Symptom Duration on Patient-Reported Outcomes at 2- and 5-Year Follow-Up in Patients Undergoing Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome. Osteology 2025, 5, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040037

Moore M, Montgomery SR, Chen L, Lehman A, Levitt S, Kaplan DJ, Youm T. The Effect of Age and Symptom Duration on Patient-Reported Outcomes at 2- and 5-Year Follow-Up in Patients Undergoing Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome. Osteology. 2025; 5(4):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040037

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoore, Michael, Samuel R. Montgomery, Larry Chen, Andrew Lehman, Sarah Levitt, Daniel J. Kaplan, and Thomas Youm. 2025. "The Effect of Age and Symptom Duration on Patient-Reported Outcomes at 2- and 5-Year Follow-Up in Patients Undergoing Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome" Osteology 5, no. 4: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040037

APA StyleMoore, M., Montgomery, S. R., Chen, L., Lehman, A., Levitt, S., Kaplan, D. J., & Youm, T. (2025). The Effect of Age and Symptom Duration on Patient-Reported Outcomes at 2- and 5-Year Follow-Up in Patients Undergoing Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome. Osteology, 5(4), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5040037