Abstract

A novel series of Schiff bases (3a–3k), incorporating tranexamic acid (TXA) and phenol-derived aldehydes via imine linkers, was synthesized and structurally characterized. The antimicrobial activity of the compounds was evaluated against a range of clinically and environmentally relevant bacterial and fungal strains. Among them, derivatives 3i and 3k, bearing bromine and chlorine substituents on the phenol ring, exhibited the most potent antimicrobial effects, particularly against Penicillium italicum and Proteus mirabilis (MIC as low as 0.014 mg/mL). To elucidate the underlying mechanism of action, in silico molecular docking studies were conducted, revealing strong binding affinities of 3i and 3k toward fungal sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51B), with predicted binding energies surpassing those of the reference antifungal ketoconazole. Additionally, UV-Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy assays demonstrated good stability of compound 3k in PBS and its effective binding to human serum albumin (HSA), respectively. ADMET and ProTox-II predictions further supported the drug-likeness, low toxicity (Class 4), and favorable pharmacokinetic profile of compound 3k. Collectively, these findings highlight TXA–phenol imine derivatives as promising scaffolds for the development of next-generation antimicrobial agents, particularly targeting resistant fungal pathogens.

1. Introduction

TXA (the trans-stereoisomer of 4-(aminomethyl)cyclohexane-carboxylic acid) is a synthetic derivative of the amino acid lysine. It can bind to lysine-binding sites on plasminogen, thereby inhibiting the formation of plasmin [1,2]. This compound exhibits an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting plasmin-mediated activation of monocytes and neutrophils. Due to its ability to inhibit fibrinolysis and prevent clot degradation, TXA has been successfully applied to prevent and reduce blood loss in a variety of clinical conditions characterized by excessive bleeding [3]. It has been found that early administration of TXA in the treatment of severe trauma and post-partum hemorrhage is associated with a reduction in thromboembolic events [4,5,6]. There are also research works describing the role of TXA in the effective treatment of hyperpigmentation and inflammation in sun-damaged skin [7,8]. Moreover, different formulations of TXA with other pharmacologically relevant compounds have been developed and used successfully as a solution for the treatment of different medical conditions, such as a combination of oral TXA with ketotifen studied for the treatment of facial melasma [9].

The synthetic modification of the TXA structural core has been employed in the design of novel compounds with improved physicochemical properties, which are essential for achieving specific pharmacological activities. For example, esterification of TXA via reaction with alkyl alcohols has produced derivatives with enhanced topical absorption [10]. Regarding Schiff bases, TXA has been widely used as a starting material for the design of suitable ligand systems, which can be further functionalized into transition-metal complexes with notable biological properties, including antimicrobial organotin(IV) [11], vanadium(III)/(IV) [12], and Co(II)/Ni(II) species [13]. The Schiff bases represent a class of organic compounds widely recognized as potent pharmacological candidates [14,15,16]. A key functional characteristic of Schiff bases is the presence of an imino group—a double bond linking carbon and nitrogen atoms in their structure, which enables the combination of alkyl and aryl substituents in many different ways [17]. Besides the unique chemical and physical properties of the imino group, as well as their ability to act as ligands for coordination compounds and acid–base properties, the Schiff bases also exhibit attractive photophysical features that make them suitable for application in optoelectronics, sensor technology, and molecular electronics [18]. The combination of two or more compounds that possess pharmacophore units in the molecular scaffold is today a recognizable concept for the design of hybrid molecules whose biological activities and pharmacodynamic/pharmacokinetic properties overcome the starting compounds. Introduction of phenol fragments into organic compounds could enable interactions with important cellular targets, modulation of enzymatic activity, inhibition of cellular signaling pathways, and regulation of oxidative stress [19]. The phenol moieties could contribute to the biological activity due to their unique properties, such as hydrogen bond abilities of OH groups, acidity, or chemical interactions enabled by the presence of aromatic benzene ring.

In this study, we present the synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation of a novel series of imine derivatives combining TXA, phenolic units, and an imine linker within a single molecular framework. All compounds were tested for antimicrobial activity against five bacterial and five fungal pathogens relevant to medicine, agriculture, and food safety. Penicillium italicum is a well-known postharvest phytopathogen responsible for blue mold decay in citrus fruits, representing one of the most economically damaging fungal infections in global citrus production [20]. Although it does not infect humans, its high prevalence in storage and distribution chains leads to significant agricultural and commercial losses, making it an important target for antifungal research. In contrast, Proteus mirabilis is an opportunistic human pathogen frequently associated with urinary tract infections, catheter-associated infections, and wound contamination [21]. Its ability to form biofilms and exhibit intrinsic antibiotic resistance contributes to its clinical relevance. Including these two microorganisms therefore enables evaluation of our compounds across both plant-pathogenic fungi and clinically relevant bacteria, providing a broader understanding of their potential antimicrobial impact. Due to the pronounced antifungal activity observed for certain derivatives, molecular docking studies were conducted to investigate their binding affinity toward sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51B), a validated fungal target involved in ergosterol biosynthesis [22]. Furthermore, the interaction of the most active compound with human serum albumin (HSA) was evaluated using fluorescence spectroscopy to assess its transport capacity under physiological conditions, while stability was monitored in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The in vitro findings were complemented by comprehensive in silico analyses aimed at elucidating the potential mechanism of antimicrobial action and predicting the pharmacokinetic profile of the most promising compounds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Procedures and Materials

All reagents were obtained from commercial sources and used as received without additional purification. NMR spectra were acquired in DMSO-d6 using a Varian Gemini 300 MHz spectrometer (Varian, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Elemental composition (C, H, N, O) was determined with an Elementar Vario MICRO analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Hesse, Germany). IR spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer FT-IR instrument (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) fitted with a DTGS detector. UV–Vis absorption measurements were performed using PerkinElmer Lambda 25 and 35 double-beam spectrophotometers (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with thermostatted 1.00 cm quartz Suprasil cells. Fluorescence studies, investigating the interactions between BSA and the tested compounds, were carried out on a Shimadzu RF-1501 PC spectrofluorometer. (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan).

2.2. Characterization

General Procedure for Synthesis 3a–3k

Equimolar amounts (1 mmol) of the appropriate aldehyde and TXA were used for the synthesis. The aldehyde was dissolved in 10 mL of ethanol, followed by the dropwise addition of an aqueous solution of TXA (1 mmol in 2 mL of distilled water). The reaction mixture was refluxed under constant stirring for 6 h. Upon completion, a solid precipitate formed, which was collected by filtration, washed with cold ethanol, and dried under reduced pressure. The resulting compounds were characterized by 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy, infrared (IR) spectroscopy, and elemental analysis (EA) to confirm their structures and purity (see Supplemental Materials).

3a: Yellow powder. Yield: 73%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ13.86 (s, 1H,-COO-H), 8.49 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 7.00 (ddd, J = 8.0, 3.6, 1.5 Hz, 2H, o-vanillin-Ar-H), 6.77 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, o-vanillin-Ar-H), 3.77 (s, 3H, -OCH3), 3.45 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H, -N-CH2-), 2.13 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.96–1.87 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.81-1.71 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.63-1.47 (m, 1H, TXA-CH-), 1.31 (qd, J = 12.9, 3.0 Hz, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.11-0.95 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.86, 166.31 (-N=C-), 152.66, 148.40, 123.32, 118.26, 117.56, 114.81, 64.02, 55.90, 42.65, 38.04, 29.71, 28.43; Anal. Calcd. for (C16H21NO4) C: 65.96; H: 7.27; N: 4.81; O: 21.97 Found: C: 65.98; H: 7.21; N: 4.87; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1639.26 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-);

3b: Yellow powder. Yield: 78%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.92 (s, 1H, -COO-H), 12.02 (s, 1H, -O-H), 8.49 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 7.01 (ddd, J = 8.0, 3.6, 1.5 Hz, 2H, p-vanillin-Ar-H), 6.78 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, p-vanillin-Ar-H), 3.75 (s, 3H, -OCH3), 3.46 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H, -N-CH2-), 2.13 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.99-1.85 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.83-1.70 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.65-1.48 (m, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-),), 1.32 (qd, J = 12.8, 3.0 Hz, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.15-0.94 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.40, 165.85 (-N=C-), 152.20, 147.94, 122.86, 117.80, 117.10, 114.35, 63.56, 55.45, 42.19, 37.58, 29.25, 27.97; Anal. Calcd. for (C16H21NO4) C: 65.96; H: 7.27; N: 4.81; O: 21.97 Found: C: 65.90; H: 7.22; N: 4.85; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1635.07 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-);

3c: Yellow powder. Yield: 69%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.59 (s, 1H, -COO-H), 8.51 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 7.43 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H, salicylald-Ar-H), 7.36-7.25 (m, 1H, salicylald-Ar-H), 6.94-6.77 (m, 2H, salicylald-Ar-H), 3.45 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H, N-CH2-), 2.13 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H, TXA-CH-), 2.01-1.85 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.83-1.71 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.64-1.48 (m, 1H, TXA-CH-), 1.31 (qd, J = 12.9, 3.1 Hz, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.03 (qd, J = 12.8, 3.3 Hz, 2H, TXA-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.87, 166.15 (-N=C-), 161.11, 132.43, 131.77, 118.72, 118.56, 116.70, 64.79, 42.69, 38.07, 29.79, 28.44; Anal. Calcd. for (C15H19NO3) C: 68.94; H: 7.33; N: 5.36; O: 18.37 Found: C: 68.89; H: 7.34; N: 5.41; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1652.20 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-);

3d: Yellow powder. Yield: 81%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.80 (s, 1H, -COO-H), 8.28 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, 2,4-dihydroxybenzald.-Ar-H), 6.23 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.3 Hz, 1H, 2,4-dihydroxybenzald.-Ar-H), 6.13 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H, 2,4-dihydroxybenzald.-Ar-H), 3.35 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H, N-CH2-), 2.11 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.3 Hz, 1H, TXA-CH-), 1.98-1.83 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.81-1.65 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.62-1.44 (m, 1H TXA-CH-), 1.30 (qd, J = 12.9, 2.9 Hz, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.16-0.85 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.94, 166.06 (-N=C-), 165.06, 162.17, 133.60, 111.25, 106.89, 102.95, 63.01, 42.73, 38.16, 29.71, 28.45; Anal. Calcd. for (C15H19NO4) C: 64.97; H: 6.91; N: 5.05; O: 23.08 Found: C: 64.92; H: 6.94; N: 5.11; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1643.25 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-);

3e: Yellow powder. Yield: 73%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.92 (s, 1H, -COO-H), 8.48 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 6.99 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H, 3-etoxysalicylald-Ar-H), 6.79-6.68 (m, 1H, 3-etoxysalicylald-Ar-H), 4.01 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, O-CH2-), 3.45 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H, N-CH2-), 2.13 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H, TXA-CH-), 1.97-1.87 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.82-1.71 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.63-1.45 (m, 1H, TXA-CH-), 1.39-1.22 (m, 5H, TXA-CH2- and -CH3), 1.11-0.95 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.92, 166.35 (-N=C-), 152.78, 147.52, 123.45, 118.45, 117.65, 116.15, 64.09, 42.68, 38.08, 29.73, 28.47, 15.02; Anal. Calcd. for (C17H23NO4) C: 66.86; H: 7.59; N: 4.59; O: 20.96 Found: C: 66.83; H: 7.51; N: 4.50; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1699.55 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-);

3f: Yellow powder. Yield: 88%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.65 (s, 1H, -COO-H), 8.51 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 7.44 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H, 3-OH-benzald.-Ar-H), 7.37–7.24 (m, 1H, 3-OH-benzald.-Ar-H), 6.97-6.75 (m, 2H, 3-OH-benzald.-Ar-H), 3.45 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, N-CH2-), 2.13 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H, TXA-CH-), 1.99-1.84 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.84-1.68 (m, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.62-1.46 (m, 1H, TXA-CH-), 1.31 (qd, J = 12.9, 3.1 Hz, 2H, TXA-CH2-), 1.03 (qd, J = 12.8, 3.3 Hz, 2H, TXA-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.13, 165.43 (-N=C-), 160.37, 131.70, 131.03, 117.98, 115.97, 64.05, 41.95, 37.33, 29.06, 27.71. Anal. Calcd. for (C15H19NO3) C: 68.94; H: 7.33; N: 5.36; O: 18.37 Found: C: 68.98; H: 7.31; N: 5.39; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1635.52 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-);

3g: Yellow powder. Yield: 75%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.24 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 6.64 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 3,4,5-trihydroxy benzald.-Ar-H), 6.17 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, 3,4,5-trihydroxy benzald.-Ar-H), 3,38 (d, 2H, -CH2-N-, overlappted by water peak), 2.12 (t, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.92 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.76 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 2H, tranexamcacid-CH2-), 1.63-1.42 (m, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.30 (q, J = 12.4, 11.4 Hz, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.12-0.87 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.95, 165.13 (-N=C-), 159.16, 148.77, 133.30, 123.10, 110.39, 106.87, 60.56, 42.68, 38.05, 29.50, 28.40; Anal. Calcd. for (C15H19NO5) C: 61.42; H: 6.53; N: 4.78; O: 27.27 Found: C: 61.38; H: 6.56; N: 4.74; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1645.79 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-);

3h: Yellow powder. Yield: 89%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.45 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 6.82 (td, J = 8.1, 1.6 Hz, 2H, 2,3-dihydroxybenzald.-Ar-H), 6.60 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 2,3-dihydroxybenzald.-Ar-H), 3.46 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H, -CH2-N-), 2.13 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.92 (d, J = 50.0 Hz, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.77 (dd, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.63-1.48 (m, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.31 (qd, J = 12.9, 3.0 Hz, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.04 (tdd, J = 15.6, 11.0, 3.4 Hz, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.92, 166.40 (-N=C-), 153.23, 146.45, 122.00, 117.71, 117.45, 117.20, 63.07, 42.68, 38.04, 29.67, 28.44; Anal. Calcd. for (C15H19NO4) C: 64.97; H: 6.91; N: 5.05; O: 23.08 Found: C: 64.82; H: 6.95; N: 5.03; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1644.37 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-);

3i: Yellow powder. Yield: 80%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.84 (s, 1H, -COO-H), 8.49 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 7.65 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H, 5-Br-salicylald-Ar-H), 7.45 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H, 5-Br-salicylald-Ar-H), 6.83 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, 5-Br-salicylald-Ar-H), 3.48-3.43 (d, overlapped by water, 2H, -CH2-N-) 2.12 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.96-1.85 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.80-1.70 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.63-1.46 (m, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.30 (qd, J = 12.9, 3.0 Hz, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.08-0.95 (m, J = 12.9, 3.1 Hz, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.97, 165.16 (-N=C-), 161.01, 135.06, 133.72, 120.29, 119.52, 109.02, 64.45, 42.70, 37.99, 29.77, 28.47; Anal. Calcd. for (C15H18BrNO3) C: 52.96; H: 5.33; N: 4.12; O: 14.11 Found: C: 52.91; H: 5.38; N: 4.10; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1691.19 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-);

3j: Yellow powder. Yield: 85%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 14.20 (s, 1H, -COO-H), 12.08 (s, 1H, -O-H), 9.08 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 8.06 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, 2-hydroxy-1-naphtalenald.-Ar-H), 7.72 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, 2-hydroxy-1-naphtalenald.-Ar-H), 7.64-7.58 (m, 1H, 2-hydroxy-1-naphtalenald.-Ar-H), 7.48-7.36 (m, 1H, 2-hydroxy-1-naphtalenald.-Ar-H), 7.23-7.11 (m, 1H, 2-hydroxy-1-naphtalenald.-Ar-H), 6.71 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, 2-hydroxy-1-naphtalenald.-Ar-H), 3.51 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H, -CH2-N-), 2.14 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.3 Hz, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.99-1.88 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.84-1.73 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.67-1.49 (m, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.31 (qd, J = 12.9, 3.0 Hz, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.13-0.95 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 177.88, 176.84, 164.21 (-N=C-), 159.56, 137.32, 134.52, 129.09, 128.10, 127.79, 125.86, 125.31, 122.45, 122.34, 118.98, 118.64, 105.78, 56.77, 42.57, 37.94, 29.20, 28.28; Anal. Calcd. for (C19H21NO3) C: 73.29; H; 6.80; N: 4.50; O: 15.41 Found: C: 73.25; H; 6.87; N: 4.55; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1630.69 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-);

3k: Yellow powder. Yield: 89%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.79 (s, 1H, -COO-H), 8.50 (s, 1H, -N=C-H), 7.54 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H, 5-Cl-salicylald-Ar-H), 7.34 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.7 Hz, 1H, 5-Cl-salicylald-Ar-H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H, 5-Cl-salicylald-Ar-H), 3.45 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H, -CH2-N-), 2.12 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.97-1.85 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.821.68 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.62–1.48 (m, 1H, tranexamicacid-CH-), 1.31 (qd, J = 12.9, 3.0 Hz, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-), 1.02 (m, 2H, tranexamicacid-CH2-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.89, 165.14 (-N=C-), 160.37, 132.21, 130.73, 121.75, 119.66, 118.94, 64.54, 42.65, 37.96, 29.75, 28.43; Anal. Calcd. for (C15H18ClNO3) C: 60.92; H: 6.13; N: 4.74; O: 16.23 Found: C: 60.99; H: 6.19; N: 4.69; FT-IR (KBr): ṽ = 1691.18 cm−1 (s) (-N=C-).

2.3. Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of the synthesized compounds was evaluated using the microdilution method. Testing was performed against a range of bacterial and fungal strains, all obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The bacterial strains included Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Proteus mirabilis (ATCC 29906), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 70063). Fungal testing was carried out on Mucor mucedo (ATCC 20094), Cladosporium cladosporioides (ATCC 11680), Penicillium italicum (ATCC 10454), Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC 1022), and Rhizopus stolonifer (ATCC 6227a). Bacterial cultures were maintained on Müller-Hinton (MH) agar, while fungal cultures were maintained on Sabouraud dextrose (SD) agar (Torlak, Belgrade). Bacterial suspensions were prepared from 24 h incubated cultures at 37 °C on Müller-Hinton agar and diluted to approximately 108 CFU/mL according to the 0.5 McFarland standard. Fungal suspensions consisted of spores of 3 to 7 days old fungal cultures and sterile distilled water, adjusted to contain approximately 106 CFU/mL following the procedure recommended by NCCLS.

The antimicrobial activity of compounds was evaluated using the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay [23]. Stock solutions of the tested compounds were initially prepared in 5% DMSO. Serial twofold dilutions were then performed to generate a concentration range from 15 to 0.007 mg/mL in sterile microplates containing Mueller-Hinton broth for bacterial assays and Sabouraud dextrose broth for fungal assays. Bacterial and fungal suspensions were added to the corresponding wells, and resazurin solution was included as an indicator of bacterial growth. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h for bacteria and at 28 °C for 72 h for fungi. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for bacteria was determined visually as the lowest compound concentration that prevented the color change in resazurin from blue to pink, while for fungi, the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration that visibly inhibited mycelial growth. Streptomycin (for bacteria) and ketoconazole (for fungi) were used as positive controls, and 5% DMSO served as the negative control to account for any solvent effects.

2.4. Molecular Docking Methodology

Molecular docking studies were conducted to assess the binding affinity and inhibitory potential of compounds 3a, 3i, and 3k toward sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51B). These simulations aimed to provide a detailed understanding of the molecular interactions between the ligands and the target protein, thereby elucidating possible mechanisms underlying their biological activity. The comprehensive computational approach incorporated established docking methodologies to predict the binding modes and estimate the thermodynamic favorability of the ligand–enzyme complexes. The docking protocol was implemented using the AutoDock Tools 1.5.7 graphical interface coupled with AutoDock 4.2.6 for the execution of docking runs [24]. The Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) [25], recognized for its efficiency in exploring conformational space, was employed to identify optimal ligand binding conformations. This algorithm allows full ligand flexibility while keeping the receptor rigid, which closely mimics physiological conditions where the protein backbone is largely static during ligand binding. A cubic docking grid measuring 70 × 70 × 70 Å was meticulously defined to encompass the entire active site region of CYP51B, centered at coordinates 135.543 × 196.724 × 3.934 Å, with a grid spacing of 0.375 Å to ensure fine spatial resolution. Simulation parameters included a population size of 150, a maximum of 250,000 energy evaluations, and 27,000 generations, striking a balance between computational efficiency and thorough conformational sampling. Mutation and crossover rates were set to 0.02 and 0.8, respectively. The structural data for CYP51B were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 4UYM), corresponding to sterol 14α-demethylase from Aspergillus fumigatus in complex with the antifungal drug voriconazole [22]. Before docking, the protein structure was carefully prepared using BIOVIA Discovery Studio 4.0 [26]. This preparation step involved the removal of crystallographic water molecules, co-crystallized ligands, and heteroatoms not relevant to the binding site to avoid artifacts in the docking results. Additionally, to ensure consistency and reduce computational complexity, only chain A of the CYP51B dimeric structure was retained for further analysis. Before docking simulations, the investigated ligands underwent geometry optimization using density functional theory (DFT), implemented in the Gaussian16 software package [27]. The B3LYP exchange correlation functional was chosen in combination with the 6-31+G(d,p) basis set and Grimme’s D3BJ dispersion correction to accurately model electron correlation effects and dispersion forces critical for non-covalent interactions. This quantum chemical optimization provided reliable molecular geometries and electronic descriptors necessary for precise docking and interaction energy calculations. In addition, acid–base speciation and molar fraction distributions were assessed using the CXN Playground platform (https://playground.calculators.cxn.io/) (accessed on 11 December 2025) to identify the most representative protonation states under physiological pH conditions. The integration of quantum chemical ligand optimization, speciation analysis, and advanced molecular docking techniques allowed for a systematic and reliable investigation of the binding profiles of compounds 3a, 3i, and 3k. The docking results offer valuable insights into the molecular recognition features and thermodynamic stability of these protein–ligand complexes. Furthermore, computational findings complement experimental data and serve as a predictive tool for guiding the rational design of novel inhibitors targeting CYP51B.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Phenol-TXA Derivatives

The reaction of TXA 1 with the corresponding OH-substituted aldehydes 2a–k yielded the targeted phenol–TXA derivatives 3a–k in absolute ethanol at ambient temperature, as shown in Scheme 1. All compounds were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR, and elemental analysis, and the corresponding spectral data are provided in the Materials and Methods Section and the ESI. Although two of the synthesized derivatives 3c and 3d have been reported in the literature [28,29], apart from their crystal structures, their other experimental spectral data have not previously been described.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of TXA–phenol derivatives.

3.2. Biological Assay

3.2.1. Antimicrobial Assay

The antimicrobial activity of the synthesized compounds was evaluated by determining their minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) against a range of common microorganisms, which included pathogens responsible for human, animal, and plant diseases, mycotoxin producers, and food spoilage agents. As indicated in Table 1 and Table 2, the MIC values of our compounds for bacteria and fungi ranged from 0.014 to 7.5 mg/mL, with the lowest value (0.014 mg/mL) being observed against Penicillium italicum by the 3i and 3k compounds.

Table 1.

Antibacterial activity of the tested compounds.

Table 2.

Antifungal activity of the tested compounds.

The strongest antibacterial activity was found in 3i and 3k against P. mirabilis with an MIC value of 0.058 mg/mL. Also, these two compounds inhibited other bacteria in low concentrations (MIC from 0.117 to 0.468 mg/mL). 3a and 3e also inhibited the growth of the tested bacteria at low concentrations (from 0.117 to 0.937 mg/mL). Remaining investigated components inhibited tested bacteria in slightly higher concentrations.

The antifungal effect of the synthesized compounds was stronger than the antibacterial effect (from 0.014 to 0.937 mg/mL). The highest activity was found in 3i and 3k compounds which inhibited the growth of all tested fungi at very low concentrations (from 0.014 to 0.234 mg/mL).

The antimicrobial activity was compared with the standard antibiotics, streptomycin (for bacteria) and ketoconazole (for fungi). The results showed that standard antibiotics had slightly stronger activity than the tested samples. Regarding the negative control, DMSO had no inhibitory effect on the tested organisms.

Among the tested microorganisms, the most sensitive to all tested compounds appeared to be Penicillium italicum.

In this study, our compounds demonstrated stronger effects on fungi than bacteria. The observed stronger antimicrobial activity of our compounds against fungi may be attributed to their ability to reduce the content of ergosterol, a crucial component of fungal cell membranes, which is essential for maintaining membrane integrity and other functions. The tested compounds can also affect various cellular processes such as cell volume reduction, intracellular ROS production, and mitochondrial dysfunction. The synthesized compounds can also inhibit conidia germination and mycelial growth of the tested fungi. These mechanisms are potential ways our synthesized compounds could exhibit antimicrobial activity against the tested fungi. The stronger antifungal activity observed for our synthesized compounds is consistent with previously reported mechanisms for phenolic Schiff bases and related ligand systems. Several studies have shown that such compounds can interfere with fungal-specific pathways, particularly by disrupting or reducing ergosterol content, which is essential for maintaining fungal membrane integrity and function [30]. Additionally, Schiff-base derivatives have been reported to induce intracellular oxidative stress, alter mitochondrial function, and affect cellular homeostasis through changes in cell volume regulation [31]. Taken together, these literature-supported mechanisms provide a plausible explanation for the enhanced antifungal effects exhibited by the synthesized compounds.

A common structural feature of compounds 3i and 3k is the presence of halogen substituents at the phenol ring, chlorine in the case of compound 3k and bromine in the case of compound 3i. Taking this into consideration, it is not surprising that these two compounds affect microbial strains most efficiently, since their presence can contribute to the disruption of microbial cell walls, inactivation of proteins, and reduction in biofilm formation. Numerous literature sources are highlighting the power of the halogen substituents introduction in the creation of compounds with promising antimicrobial agents [32,33,34,35].

The 2-OH group plays an important structural role in this class of Schiff bases. In most of the synthesized derivatives, the phenolic aldehydes were selected specifically with an ortho-hydroxy group because this functional group is known to form a stabilizing intramolecular hydrogen bond with the imine nitrogen. This interaction increases the thermodynamic stability of the Schiff base, improves planarity, and often enhances biological activity, as widely reported in the literature.

As a result of this study, 3i and 3k showed the strongest antimicrobial activity. Therefore, these compounds can be new, potential antimicrobial agents, especially antifungal agents.

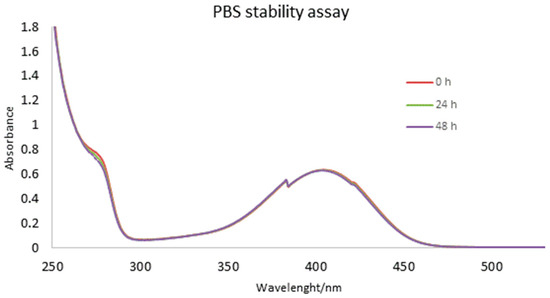

3.2.2. Stability Assay

The ability of PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) to maintain stable pH and match physiological conditions, makes it irreplaceable in the cell culture, protein studies, and sample preparation. Therefore, to gain insight into the compounds’ stability and behavior under physiological conditions, herein we performed stability screening of selected example 3k in PBS by following UV-Vis spectra during different time intervals. As shown in Figure 1, at 0, 24 and 48 h, the shapes of the peaks were the almost the same, which indicated that 3k was stable in PBS. Negligible absorbance changing could be attributed to the evaporation of solvent during time.

Figure 1.

The stability of compound 3k in PBS followed by UV-Vis spectrophotometry.

3.3. Protein Binding Studies—Fluorescence Spectroscopy of HSA

Within the bloodstream, albumin is one of the most medicinally interesting protein and plays a crucial role in transporting vital medications to their targeted sites. Examining the interactions between the different compounds and serum albumin provides a better understanding of the mechanism of action of tested drugs [36]. Human serum albumin (HSA) produces a fluorescence signal when excited at 295 nm due to the tryptophan residues [37,38]. This makes fluorescence spectroscopy an effective method for studying the interactions of HSA with various molecules. If the examined compound interacts with HSA, an increasing concentration of the tested compound will lead to a decrease in fluorescence, as presented in Figure 2 (as the arrow at the left graph indicates).

Figure 2.

(graphs left) Emission spectra of HSA in the absence and presence of quencher 3k. pH = 7.4; λex = 295 nm; (graphs right) plots of I0/I versus [3k] in mol/dm3.

The decrease in fluorescence is indicative of changes in the tertiary protein structure, suggesting the binding of the examined compound to the HSA molecule [37]. Fluorescence quenching of HSA induced by some compound is described by the Stern–Volmer Equation (1) [39].

where I0 and I are the emission intensities in the absence and in the presence of the quencher (examined compound, 3k), [Q] is quencher’s concentration, in this case concentration of 3k, and Ksv is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant. The value of Ksv is obtained from the linear dependence of I0/I to [Q]. Further, the values of quenching rate constant (kq) were determined directly from the Stern–Volmer quenching constant (Equation (2)) [40],

and values are summarized in Table 3.

I0/I = 1 + Ksv [Q]

Ksv = kq × τ0

Table 3.

Stern-Volmer (Ksv) and kq constants from HSA fluorescence for 3k.

Based on these results, it is evident that tested compound, 3k, displayed a suitable binding affinity for the HSA molecule.

3.4. Molecular Docking Study

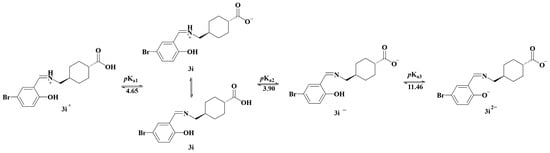

Molecular Docking Study of Complexes in the CYP51B

The pKa values of the investigated compounds were initially calculated using the CXN Playground platform, which also enabled the elucidation of their deprotonation pathways (Figure 3, Figure S34 and Figure S35). This approach enabled the prediction of protonation states across a wide pH range, facilitating a detailed assessment of their chemical behavior in aqueous media. Accurate identification of these states is essential for understanding molecular charge distribution, electrostatic interactions, and hydrogen-bonding potential, all of which critically influence ligand–target recognition and binding affinity.

Figure 3.

Deprotonation pathway and corresponding pKa values of compound 3i.

Based on the calculated pKa values, the molar fraction distribution of the various acid–base species was determined as a function of pH (Figure 4). The speciation diagrams demonstrate that at physiological pH (~7.4), all three compounds (3a, 3i, and 3k) predominantly exist in their monoanionic forms. Specifically, the neutral and zwitterionic species are relevant only in acidic to near-neutral pH ranges, while the dianionic forms become significant only at pH values above 11. These findings firmly establish that the monoanionic species represent the dominant and biologically relevant protonation states under physiological conditions.

Figure 4.

Distribution of molecular species of the investigated compounds across different pH values.

Accordingly, the monoanionic forms were selected as the most appropriate species for subsequent molecular docking simulations, as they most accurately reflect the compounds’ speciation and ionization states in vivo. This ensures higher reliability and biological relevance of the predicted protein–ligand interactions and allows for a more realistic modeling of binding affinities and molecular recognition mechanisms.

The molecular docking analysis revealed notable differences in the interactions between the investigated compounds and the CYP51B enzyme, as reflected in the variations in thermodynamic parameters and inhibition constants summarized in Table 4. The overall trend in reactivity, based on ΔGbind and Ki values, follows the order: 3i− > 3k− > 3a−, indicating a gradual decrease in binding affinity and inhibitory potential across the series. This trend clearly indicates that the introduction of halogen substituents on the aromatic ring significantly contributes to the stabilization of the ligand–enzyme complex. The strongest interaction observed for compound 3i can be associated with the higher polarizability of bromine compared to chlorine, which allows for enhanced dispersion interactions and potentially more favorable halogen–acceptor contacts with electron-rich regions of the active site. Accordingly, the absence of a halogen substituent in compound 3a is reflected in its weaker binding affinity and higher Ki value. When compared to the reference compound ketoconazole (KET), all three investigated monoanionic derivatives displayed stronger binding affinities and significantly lower inhibition constants, suggesting improved inhibitory efficiency toward CYP51B. While the binding affinities of the studied compounds were generally comparable, the monoanion of compound 3i demonstrated the most pronounced interaction with the enzyme, with a calculated ΔGbind of −13.76 kcal mol−1, indicating its potential as the most potent inhibitor within the series. Despite the observed differences in binding free energies, all compounds showed sufficient affinity for CYP51B. Furthermore, each complex successfully occupied the binding region within the enzyme’s active site, supporting their potential biological relevance.

Table 4.

Docking-derived energetic descriptors (kcal mol−1) and inhibition constants for the most stable CYP51B–ligand complexes (kcal mol−1): inhibition constants (Ki, µM) and binding free energy (ΔGbind, kcal mol−1) values obtained from various individual energy components such as total internal energy (ΔGtotal), torsional free energy (ΔGtor), unbound system’s energy (ΔGunb), electrostatic energy (ΔGelec), and the sum of dispersion and repulsion (ΔGvdw), hydrogen bond (ΔGhbond), and desolvation (ΔGdesolv).

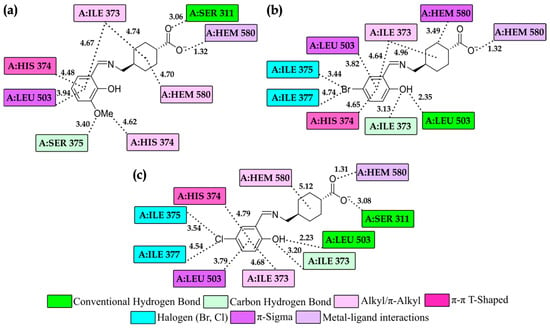

A comprehensive analysis of the binding interactions between compounds 3a, 3i, and 3k and the active site of CYP51B was conducted based on the molecular docking results. The 2D representations of the ligand–protein interactions at this binding site are illustrated in Figure 5. The interaction profiles consistently indicated that hydrogen bonding plays a central role as the primary stabilizing force facilitating ligand binding. These hydrogen bonds contribute significantly to the specificity and strength of the ligand–enzyme complex formation. In addition to hydrogen bonding, various hydrophobic interactions were identified, which further enhance the stability and selectivity of the binding conformations. Notably, alkyl and π-alkyl interactions, as well as π-π T-shaped interactions between the aromatic moieties of the ligands and the amino acid residues in the binding pocket, were recurrently observed across all three compounds. These non-covalent interactions are critical in maintaining the proper orientation and affinity of the ligands within the active site, thereby influencing their inhibitory potential. Overall, the combination of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts defines a multifaceted binding mechanism that underscores the high affinity and selectivity of the investigated compounds toward CYP51B.

Figure 5.

Representative 2D diagrams derived from molecular docking simulations depict the key intermolecular interactions between the amino acid residues of the sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51B) active site and the investigated compounds 3a− (a), 3i− (b), and 3k− (c). Interatomic distances, expressed in angstroms (Å), were obtained through molecular docking studies. Various types of interactions are distinguished by color coding, as specified in the legend.

A crucial interaction that significantly contributes to the inhibitory potential of the investigated compounds is the metal–ligand coordination interaction formed with the HEM cofactor (A:HEM 580). This interaction is established through the oxygen atom of the carboxylate group, which directly coordinates the iron atom at the center of the heme moiety. Such coordination is of particular importance because it directly affects the catalytic functionality of the enzyme’s active site. Unlike typical reversible non-covalent interactions, metal–ligand coordination suggests a stronger and more persistent mode of binding, thereby enhancing the stability of the ligand–enzyme complex and increasing the pharmacological relevance of these compounds as potential CYP51B inhibitors.

It is particularly noteworthy that the halogenated derivatives (3i and 3k) exhibit additional stabilization through halogen-mediated interactions, which are absent in the non-halogenated compound 3a. Specifically, the bromine and chlorine substituents participate in favorable halogen–acceptor interactions with hydrophobic and electron-rich regions of the active site, primarily involving residues A:ILE 375 and A:ILE 377 (Figure 5). These interactions arise from the anisotropic distribution of electron density around the halogen atoms, leading to the formation of a σ-hole that enables directional attraction toward nucleophilic regions of the protein. The stronger interaction profile observed for compound 3i is consistent with the higher polarizability of bromine relative to chlorine, which enhances dispersion forces and the strength of halogen bonding compared to compound 3k.

Non-covalent interactions also significantly contribute to the stability of the ligand–enzyme complex and the precise positioning of the ligands within the enzyme’s active site. Conventional hydrogen bonds play a key role, primarily involving amino acid residues within the catalytic pocket [42,43]. These interactions predominantly occur with amino acid residues located within the active site of the enzyme, specifically involving residue A:SER 311 in the complexes with compounds 3a and 3k, as well as residue A:LEU 503 in complexes with 3i and 3k. Besides classical hydrogen bonding, distinct carbon–hydrogen interactions were also detected, particularly between all three compounds and residue A:SER 375. Additionally, compounds 3i and 3k exhibit this type of interaction with residue A:ILE 373. Together, these non-covalent interactions contribute significantly to the overall structural integrity of the complexes and facilitate precise ligand positioning within the catalytic pocket.

Compounds 3a, 3i, and 3k also display a marked capacity to engage in hydrophobic interactions with key residues such as A:ILE 373, A:HIS 374, A:ILE 377, and A:HEM 580. These interactions are mainly mediated through alkyl and π-alkyl contacts, which play an important role in stabilizing the ligands inside the binding site. Beyond hydrophobic forces, other non-covalent interactions are essential for maintaining the structural cohesion of these complexes. Notably, π–sigma interactions, resulting from the spatial overlap between the π-electron clouds of aromatic rings and neighboring σ bonds [42], were observed between the compounds and residue A:LEU 503. Furthermore, the compound 3i forms π–sigma interactions with A:HEM 580. Another significant stabilizing force arises from π–π stacking interactions, which contribute substantially to molecular stabilization. These interactions can adopt various spatial arrangements, including T-shaped (edge-to-face) or offset parallel geometries, depending on the steric and electronic environment within the binding pocket [43,44]. In the case of the studied compounds, π–π interactions were mainly established between the aromatic moieties of the ligands and the aromatic side chain of residue A:HIS 374.

Overall, the diverse interaction patterns observed between the investigated compounds and CYP51B reveal a complex binding mechanism defined by both structural complementarity and electronic compatibility. The specificity and multiplicity of these interactions not only ensure the stable accommodation of the compounds within the protein’s binding pocket but also suggest potential implications for their biological transport and functional modulation. Such intricate binding behavior underscores the relevance of these complexes as promising candidates for further biochemical and pharmacological evaluation.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we successfully designed and synthesized a series of hybrid molecules that integrate a TXA core linked via an imine group to various phenolic scaffolds. The synthesized compounds demonstrated promising antimicrobial properties in vitro, with particularly strong activity against fungal strains. Among them, compounds 3i and 3k, containing bromine and chlorine substituents, respectively, exhibited the highest potency. Their enhanced bioactivity is attributed to specific structural features that likely disrupt microbial membranes and promote effective interactions with key protein targets.

Molecular docking studies provided insight into the underlying mechanisms of action at the molecular level, confirming strong binding affinities to fungal sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51B), surpassing those of the reference drug ketoconazole. In addition, compound 3k showed good stability in physiological buffer and a favorable binding profile with human serum albumin, supported by fluorescence spectroscopy. ADMET and ProTox-II predictions further validated the drug-like nature and low toxicity of 3k, reinforcing its potential as a lead compound.

Future research will focus on expanding the structural diversity of TXA–imine scaffolds to identify candidates with broader antimicrobial spectra, improved selectivity, and reduced resistance potential. Additionally, efforts will be directed toward developing targeted drug delivery systems to enhance therapeutic efficacy and compound stability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/org6040054/s1, Figure S1: 1H NMR spectrum of 3a. Figure S2: 13C NMR spectrum of 3a. Figure S3: FT-IR spectrum of 3a. Figure S4: 1H NMR spectrum of 3b. Figure S5: 13C NMR spectrum of 3b. Figure S6: FT-IR NMR spectrum of 3b. Figure S7: 1H NMR spectrum of 3c. Figure S8: 13C NMR spectrum of 3c. Figure S9: FT-IR spectrum of 3c. Figure S10: 1H NMR spectrum of 3d. Figure S11: 13C NMR spectrum of 3d. Figure S12: FT-IR spectrum of 3d. Figure S13: 1H NMR spectrum of 3e. Figure S14: 13C NMR spectrum of 3e. Figure S15: FT-IR spectrum of 3e. Figure S16: 1H NMR spectrum of 3f. Figure S17: 13C NMR spectrum of 3f. Figure S18: FT-IR spectrum of 3f. Figure S19: 1H NMR spectrum of 3g. Figure S20: 13C NMR spectrum of 3g. Figure S21: FT-IR spectrum of 3g. Figure S22: 1H NMR spectrum of 3h. Figure S23: 1H NMR spectrum of 3h. Figure S24: FT-IR spectrum of 3h. Figure S25: 1H NMR spectrum of 3i. Figure S26: 13C NMR spectrum of 3i. Figure S27: FT-IR spectrum of 3i. Figure S28: 1H NMR spectrum of 3j. Figure S29: 13C NMR spectrum of 3j. Figure S30: FT-IR spectrum of 3j. Figure S31: 1H NMR spectrum of 3k. Figure S32: 13C NMR spectrum of 3k. Figure S33: FT-IR spectrum of 3k. Figure S34: Deprotonation pathways and corresponding pKa values of compound 3a. Figure S35: Deprotonation pathways and corresponding pKa values of compound 3k. Table S1: SwissADME Analysis of compound 3k [45,46].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ž.M., V.M.D., M.K. and M.D.K.; Methodology, J.S.D., Ž.M. and M.D.K.; Validation, M.D.K.; Formal analysis, J.S.D., K.M. and N.P.; Resources, J.P. and N.J.; Writing—original draft, J.S.D., Ž.M., K.M., N.P., V.M.D., M.K. and M.D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia [Agreements No. 451-03-136/2025-03/200378, 451-03-137/2025-03/200122 and 451-03-136/2025-03/200122].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have do not have any competing financial and/or non-financial interests in relation to the work described.

References

- Franchini, M.; Mannucci, P.M. Adjunct agents for bleeding. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2014, 21, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, M.; Bourdiol, A.; Rooze, P.; Hourmant, Y.; Caillard, A.; Roquilly, A. Tranexamic acid: A narrative review of its current role in perioperative medicine and acute medical bleeding. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1416998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Ribkoff, J.; Olson, S.; Raghunathan, V.; Al-Samkari, H.; DeLoughery, T.G.; Shatzel, J.J. The many roles of tranexamic acid: An overview of the clinical indications for TXA in medical and surgical patients. Eur. J. Haematol. 2020, 104, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbs, S.P.; Roberts, I.; Shakur-Still, H.; Hunt, B.J. Post-partum haemorrhage and tranexamic acid: A global issue. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 180, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lier, H.; Maegele, M.; Shander, A. Tranexamic Acid for Acute Hemorrhage: A Narrative Review of Landmark Studies and a Critical Reappraisal of Its Use Over the Last Decade. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 129, 1574–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, R.J.; Spinella, P.C.; Bochicchio, G.V. Tranexamic Acid Update in Trauma. Crit. Care Clin. 2017, 33, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Souza, I.D.; Lampe, L.; Winn, D. New topical tranexamic acid derivative for the improvement of hyperpigmentation and inflammation in the sun-damaged skin. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Oh, I.Y.; Koo, K.T.; Suk, J.M.; Jung, S.W.; Park, J.O.; Kim, B.J.; Choi, Y.M. Reduction in facial hyperpigmentation after treatment with a combination of topical niacinamide and tranexamic acid: A randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial. Ski. Res. Technol. 2014, 20, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.C.L.; Cassiano, D.P.; Bleixuvehl de Brito, M. Oral ketotifen associated with oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of facial melasma in women: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, e39–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Ma, M.; Chen, Y.; Xie, H.; Ding, P.; Zhang, K. Enhancing skin delivery of tranexamic acid via esterification: Synthesis and evaluation of alkyl ester derivatives. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 34996–35004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwer, J.; Ali, S.; Shahzadi, S.; Shahid, M.; Sharma, S.K.; Qanungo, K. Synthesis, characterization, semi-empirical study and biological activities of homobimetallic complexes of tranexamic acid with organotin(IV). J. Coord. Chem. 2013, 66, 1142–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, S.; Ali, S.; Parvez, M.; Badshah, A.; Ahmed, E.; Malik, A. Synthesis, spectroscopy and antimicrobial activity of vanadium(III) and vanadium(IV) complexes involving Schiff bases derived from Tranexamic acid and X-ray structure of zwitter ion of Tranexamic acid. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 52, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Sadeek, S.A.; Rashid, N.G.; Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I. Synthesis, Characterization and Evaluation of the Antimicrobial and Herbicidal Activities of Some Transition Metal Ions Complexes with the Tranexamic Acid. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202301970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglah, A.M.; Almehizia, A.A.; Al-Wasidi, A.S.; Alharbi, A.S.; Alqarni, M.H.; Hassan, A.S.; Aboulthana, W.M. Exploring the Potential Biological Activities of Pyrazole-Based Schiff Bases as Anti-Diabetic, Anti-Alzheimer’s, Anti-Inflammatory, and Cytotoxic Agents: In Vitro Studies with Computational Predictions. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.; Alam, A.; Zainab; Assad, M.; Elhenawy, A.A.; Islam, M.S.; Shah, S.A.A.; Parveen, Z.; Shah, T.A.; Ahmad, M. Exploring the synthesis, molecular structure and biological activities of novel Bis-Schiff base derivatives: A combined theoretical and experimental approach. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1306, 137828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajid, M.; Uzair, M.; Muhammad, G.; Siddique, F.; Ashraf, A.; Ahmad, S.; Alasmari, A.F. Biological Activities, DFT and Molecular Docking Studies of Novel Schiff Bases Derived from Sulfamethoxypyridazine. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202400675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczuk, E.; Dmochowska, B.; Samaszko-Fiertek, J.; Madaj, J. Different Schiff Bases—Structure, Importance and Classification. Molecules 2022, 27, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musikavanhu, B.; Liang, Y.; Xue, Z.; Feng, L.; Zhao, L. Strategies for Improving Selectivity and Sensitivity of Schiff Base Fluorescent Chemosensors for Toxic and Heavy Metals. Molecules 2023, 28, 6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GÜLÇİN, İ.; Daştan, A. Synthesis of dimeric phenol derivatives and determination of in vitro antioxidant and radical scavenging activities. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2007, 22, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Polyphasic taxonomy of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 49, 1–174. [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster, C.E.; Mobley, H.L.T.; Pearson, M.M. Pathogenesis of Proteus mirabilis Infection. EcoSal Plus 2018, 8, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrove, T.Y.; Wawrzak, Z.; Lamb, D.C.; Guengerich, F.P.; Lepesheva, G.I. Structure-Functional Characterization of Cytochrome P450 Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51B) from Aspergillus fumigatus and Molecular Basis for the Development of Antifungal Drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 23916–23934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.D.; Nahar, L.; Kumarasamy, Y. Microtitre plate-based antibacterial assay incorporating resazurin as an indicator of cell growth, and its application in the in vitro antibacterial screening of phytochemicals. Methods 2007, 42, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Goodsell, D.S.; Halliday, R.S.; Huey, R.; Hart, W.E.; Belew, R.K.; Olson, A.J. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, J.; Rurainski, A.; Lenhof, H.; Neumann, D. A new Lamarckian genetic algorithm for flexible ligand-receptor docking. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA Version 26; Dassault Systèmes: Vélizy-Villacoublay, France, 2024.

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallin, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, F.A.; Ali, S.; Shahzadi, S. Spectral and biological studies of newly synthesized organotin(IV) complexes of 4-({[(E)-(2-hydroxyphenyl)methylidene]amino}methyl)cyclohexane carboxylic acid Schiff base. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2010, 7, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.; Akbar, S.; Tahir, M.N.; Butt, R.A.; Ashfaq, M. Crystal structure of 4-{[(2,4-dihydroxybenzylidene)amino]methyl}cyclohexanecarboxylic acid. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Crystallogr. Commun. 2015, 71, o995–o996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karan, J.; Kundu, A.; Gogoi, R.; Manjaiah, K.M.; Singh, A.K.; Mondal, K.; Kumar, R.; Kaushik, P.; Saini, P.; Rana, V.S.; et al. Synthesis of antifungal imines as inhibitors of ergosterol biosynthesis. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2025, 19, 2448897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Login, C.C.; Bâldea, I.; Tiperciuc, B.; Benedec, D.; Vodnar, D.C.; Decea, N.; Suciu, Ş. A Novel Thiazolyl Schiff Base: Antibacterial and Antifungal Effects and In Vitro Oxidative Stress Modulation on Human Endothelial Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 1607903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perz, M.; Szymanowska, D.; Kostrzewa-Susłow, E. The Influence of Flavonoids with -Br, -Cl Atoms and -NO2, -CH3 Groups on the Growth Kinetics and the Number of Pathogenic and Probiotic Microorganisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyboran-Mikołajczyk, S.; Matczak, K.; Olchowik-Grabarek, E.; Sękowski, S.; Nowicka, P.; Krawczyk-Łebek, A.; Kostrzewa-Susłow, E. The influence of the chlorine atom on the biological activity of 2′-hydroxychalcone in relation to the lipid phase of biological membranes—Anticancer and antimicrobial activity. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 398, 111082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk-Łebek, A.; Żarowska, B.; Janeczko, T.; Kostrzewa-Susłow, E. Antimicrobial Activity of Chalcones with a Chlorine Atom and Their Glycosides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, R.O.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-G.; Lee, J. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of halogenated phenols against Staphylococcus aureus and other microbes. Chemosphere 2024, 367, 143646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesović, M.; Jelić, R.; Nikolić, M.; Nedeljković, N.; Živanović, A.; Bukonjić, A.; Mrkalić, E.; Radić, G.; Ratković, Z.; Kljun, J.; et al. Investigation of the interaction between S-isoalkyl derivatives of the thiosalicylic acid and human serum albumin. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2025, 43, 4081–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimiza, F.; Perdih, F.; Tangoulis, V.; Turel, I.; Kessissoglou, D.P.; Psomas, G. Interaction of copper(II) with the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs naproxen and diclofenac: Synthesis, structure, DNA- and albumin-binding. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011, 105, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, N.; Mrkalić, E.; Jelić, R.; Tomović, J.; Odović, J.; Serafinović, M.Ć.; Sovrlić, M. The Molecular Recognition of Lurasidone by Human Serum Albumin: A Combined Experimental and Computational Approach. Molecules 2025, 30, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakowicz, J.R.; Weber, G. Quenching of fluorescence by oxygen. Probe for structural fluctuations in macromolecules. Biochemistry 1973, 12, 4161–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakowicz, J.R.; Gryczynski, I.; Gryczynski, Z.; Dattelbaum, J.D. Anisotropy-Based Sensing with Reference Fluorophores. Anal. Biochem. 1999, 267, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanović, J.S.; Matić, J.D.; Milanović, Ž.; Divac, V.M.; Kosanić, M.M.; Petković, M.R.; Kostić, M.D. Molecular modeling studies, in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial assay and BSA affinity of novel benzyl-amine derived scaffolds as CYP51B inhibitors. Mol. Divers. 2024, 29, 5499–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira de Freitas, R. Schapira MAsystematic analysis of atomic protein–ligand interactions in the PDB. Medchemcomm 2017, 8, 1970–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissantz, C.; Kuhn, B.; Stahl, M. A Medicinal Chemist’s Guide to Molecular Interactions. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 5061–5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuzuki, S.; Honda, K.; Uchimaru, T.; Mikami, M.; Tanabe, K. Origin of Attraction and Directionality of the π/π Interaction: Model Chemistry Calculations of Benzene Dimer Interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, P.; Eckert, A.O.; Schrey, A.K.; Preissner, R. ProTox-II: A webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W257–W263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).