Theoretical Modeling of BODIPY-Helicene Circularly Polarized Luminescence

Abstract

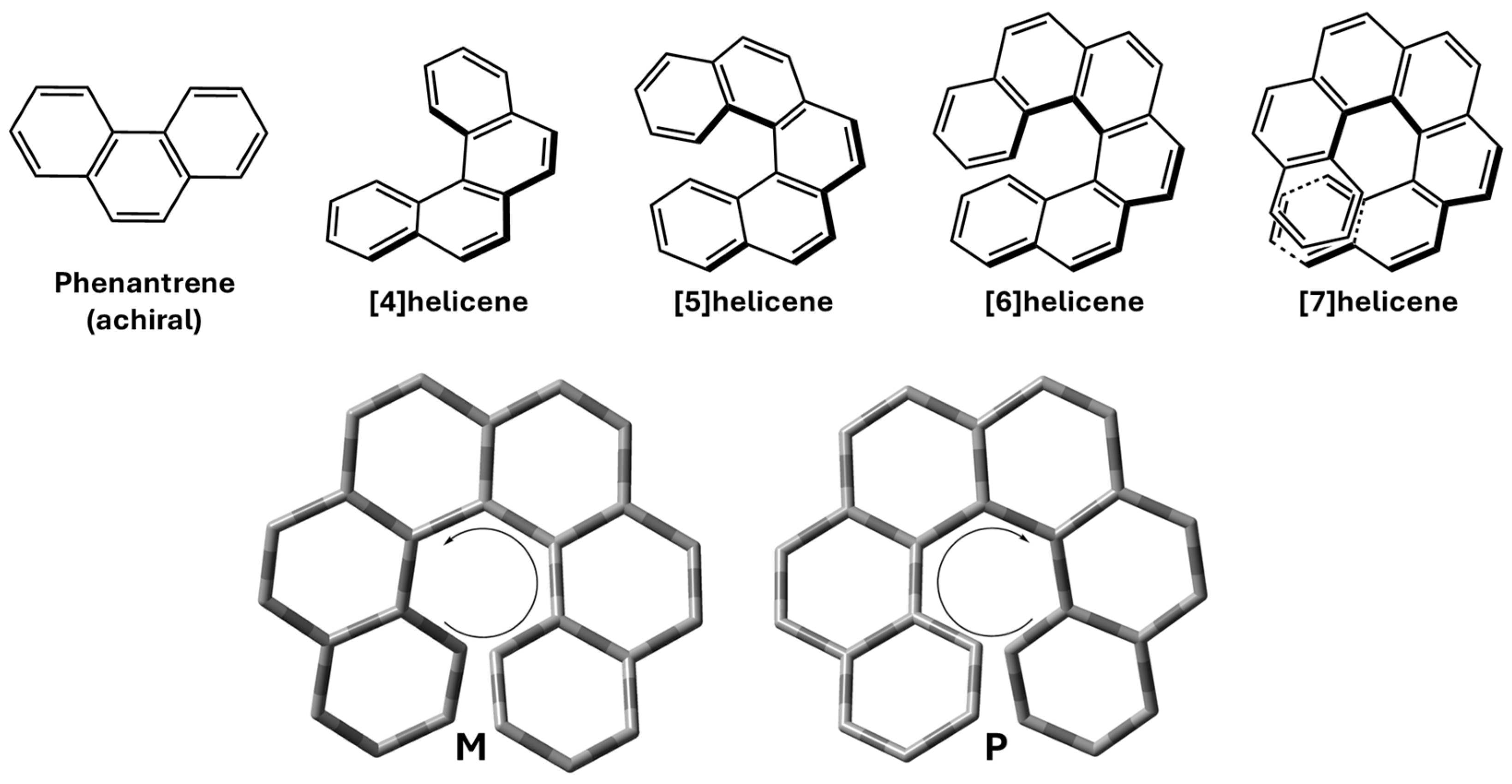

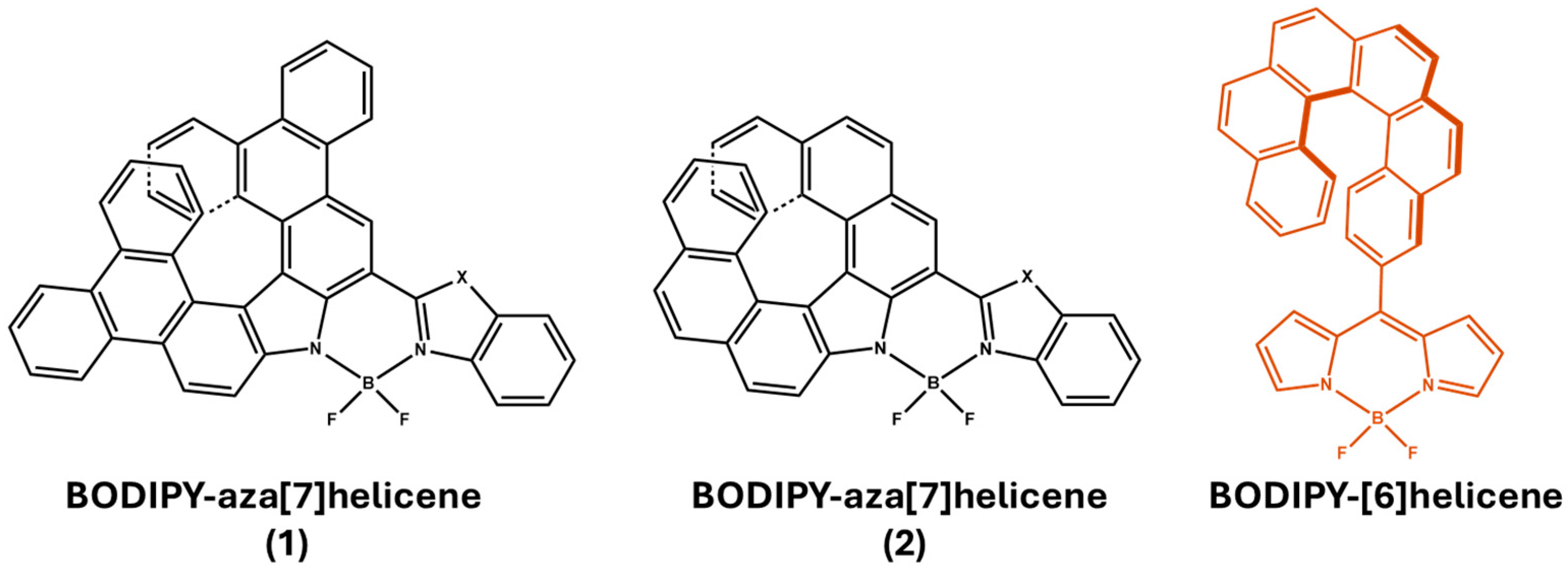

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

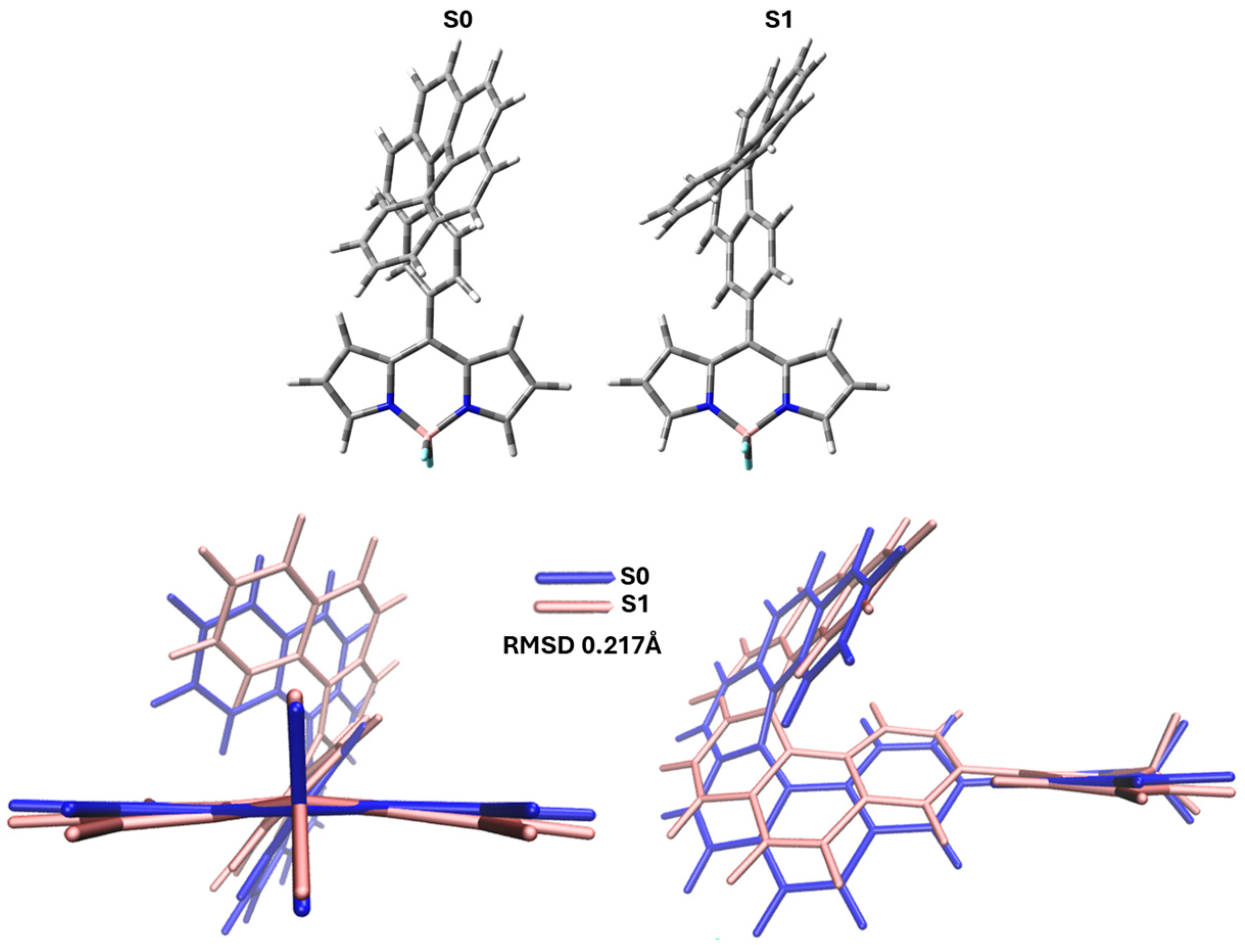

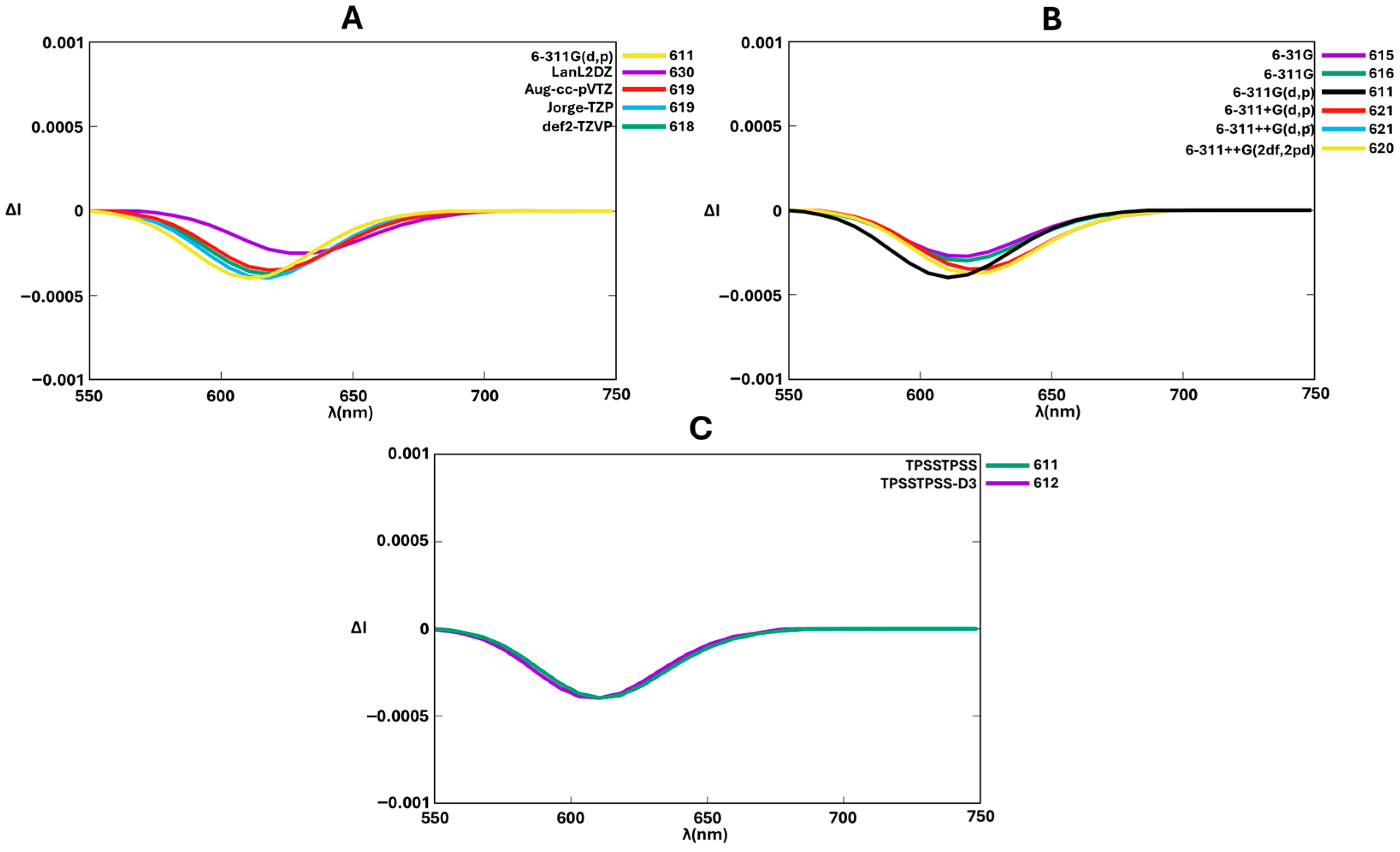

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| TD-DFT | Time-dependent density functional theory |

| CPL | Circularly polarized luminescence |

| CD | Circular dichroism |

References

- Han, L.; Hong, M. Recent Advances in the Design and Construction of Helical Coordination Polymers. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2005, 8, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Teat, S.J.; Gong, W.; Zhou, Z.; Jin, Y.; Chen, H.; Wu, J.; Cui, Y.; Jiang, T.; Cheng, X.; et al. Single Crystals of Mechanically Entwined Helical Covalent Polymers. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago-Silva, M.; Fernández-Míguez, M.; Rodríguez, R.; Quiñoá, E.; Freire, F. Stimuli-Responsive Synthetic Helical Polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 793–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, G.; Pasini, D. One-Handed Covalent Helical Ladder Polymers: The Dawn of a Tailorable Class of Chiral Functional Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Peng, L.; Liu, Y.; Wei, D. Highly Crystalline Helical Covalent Organic Frameworks. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 3666–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Dong, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Gu, Q.; Kang, F.; Li, X.-X.; Zhang, Q. A Metal-Free Helical Covalent Inorganic Polymer: Preparation, Crystal Structure and Optical Properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202315338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, E. Synthesis and Structure Determination of Helical Polymers. Polym. J. 2010, 42, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, E.; Maeda, K.; Iida, H.; Furusho, Y.; Nagai, K. Helical Polymers: Synthesis, Structures, and Functions. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6102–6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, E.; Ousaka, N.; Taura, D.; Shimomura, K.; Ikai, T.; Maeda, K. Supramolecular Helical Systems: Helical Assemblies of Small Molecules, Foldamers, and Polymers with Chiral Amplification and Their Functions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 13752–13990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Z.; Okuda, H.; Koyama, Y.; Seto, R.; Uchida, S.; Sogawa, H.; Kuwata, S.; Takata, T. Exact Helical Polymer Synthesis by a Two-Point-Covalent-Linking Protocol Between C2-Chiral Spirobifluorene and C2- or Cs-Symmetric Anthraquinone Monomers. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 10423–10426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, A.; Holub, J.; Fik-Jaskółka, M.A.; Vantomme, G.; Lehn, J.-M. Dynamic Helicates Self-Assembly from Homo- and Heterotopic Dynamic Covalent Ligand Strands. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 15664–15671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiupel, B.; Niederalt, C.; Nieger, M.; Grimme, S.; Vögtle, F. “Geländer” Helical Molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 3031–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, A.; Gidron, O. The Consequences of Twisting Nanocarbons: Lessons from Tethered Twisted Acenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 2482–2490. [Google Scholar]

- Bedi, A.; Shimon, L.J.W.; Gidron, O. Helically Locked Tethered Twistacenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8086–8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Han, X.; Wen, X.; Yu, H.; Li, B.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Wu, G. Chiral Ring-in-Ring Complexes with Torsion-Induced Circularly Polarized Luminescence. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 7858–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetto, A.; Nastasi, F.; Puntoriero, F.; Bella, G.; Campagna, S.; Lanza, S. Fast Transport of HCl across a Hydrophobic Layer over Macroscopic Distances by Using a Pt(ii) Compound as the Transporter: Micro- and Nanometric Aggregates as Effective Transporters. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P. Helical Polycyclic Heteroaromatic as Hole Transport Material for Perovskite Solar Cell: Remarkable Impact of Alkyl Substitution Position. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2301455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujise, K.; Tsurumaki, E.; Fukuhara, G.; Hara, N.; Imai, Y.; Toyota, S. Multiple Fused Anthracenes as Helical Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Motif for Chiroptical Performance Enhancement. Chem. Asian J. 2020, 15, 2456–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Tang, H.; Peng, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zeng, W. Helical Polycyclic Hydrocarbons with Open-Shell Singlet Ground States and Ambipolar Redox Behaviors. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 10519–10528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, M.; Hahn, S.; Dmitrieva, E.; Rominger, F.; Popov, A.; Bunz, U.H.F.; Feng, X.; Berger, R. Helical Ullazine-Quinoxaline-Based Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Kishida, H.; Hayama, H.; Nakano, Y.; Yamochi, H.; Saito, G. Racemic Charge-Transfer Complexes of a Helical Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Molecule. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 3626–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Petersen, J.L.; Wang, K.K. Synthesis and Structures of Helical Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Bearing Aryl Substituents at the Most Sterically Hindered Positions. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, W.-C.; Chen, C.-F. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Multiple Helicenes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2025, 23, 7501–7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, K.-H. Helicenes on Surfaces: Stereospecific on-Surface Chemistry, Single Enantiomorphism, and Electron Spin Selectivity. Chirality 2024, 36, e23706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingras, M. One Hundred Years of Helicene Chemistry. Part 1: Non-Stereoselective Syntheses of Carbohelicenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 968–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, N. Photochemical Reactions Applied to the Synthesis of Helicenes and Helicene-Like Compounds. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2014, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.-J.; Wang, X.-Y.; Li, Z.-A.; Gong, H.-Y. All Carbon Helicenes and π-Extended Helicene Derivatives. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2023, 12, e202300543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Chen, C.-F. Helicenes: Synthesis and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1463–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota, S. Expanding Chemistry of Expanded Helicenes. Chem. Eur. J. 2025, 31, e02193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, S.-Y.; Zheng, L.-S. Multiple [N]Helicenes with Various Aromatic Cores. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 4726–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafedh, N.; Aloui, F.; Raouafi, S.; Dorcet, V.; Hassine, B.B. New [4]Helicene Derivatives: Synthesis, Characterization and Photophysical Properties. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 262, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J.; Chu, A.; Wang, F.; Wang, R. Enantioselective Synthesis of [4]Helicenes by Organocatalyzed Intermolecular C-H Amination. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropasqua Talamo, M.; Cauchy, T.; Zinna, F.; Pop, F.; Avarvari, N. Tuning the Photophysical and Chiroptical Properties of [4]Helicene-Diketopyrrolopyrroles. Chirality 2023, 35, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Kaiser, R.I.; Xu, B.; Ablikim, U.; Lu, W.; Ahmed, M.; Evseev, M.M.; Bashkirov, E.K.; Azyazov, V.N.; Zagidullin, M.V.; et al. Gas Phase Synthesis of [4]-Helicene. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigon, N.; Avarvari, N. [4]Helicene-based Anions in Electrocrystallization with Tetrachalcogeno-Fulvalene Donors. CrystEngComm 2022, 24, 1942–1947. [Google Scholar]

- Hamrouni, K.; Spassova, M.; Alshammari, N.A.H.; Hajri, A.K.; Aloui, F. Synthesis of New [6]Helicene Derivatives for Oled Applications. Experimental Photophysical and Chiroptical Properties and Theoretical Investigation. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1311, 138408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wu, C.; Chen, C. Copper-Catalyzed Modular Synthesis of Aromatic-Interrupted Aza[6]Helicenes with Chiroptical Properties. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2025, 6, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Borovkov, V. Helicene-Based Chiral Auxiliaries and Chirogenesis. Symmetry 2018, 10, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubec, M.; Beránek, T.; Jakubík, P.; Sýkora, J.; Žádný, J.; Církva, V.; Storch, J. 2-Bromo[6]Helicene as a Key Intermediate for [6]Helicene Functionalization. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 3607–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, B.; LeBlanc, L.M.; Otero-de-la-Roza, A.; Fuchter, M.J.; Johnson, E.R.; Nelson, J.; Jelfs, K.E. A Computational Exploration of the Crystal Energy and Charge-Carrier Mobility Landscapes of the Chiral [6]Helicene Molecule. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 1865–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.-C.; Zhao, W.-L.; Tan, K.-K.; Li, M.; Chen, C.-F. B,N-Embedded Hetero[9]Helicene toward Highly Efficient Circularly Polarized Electroluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202401835. [Google Scholar]

- Kiel, G.R.; Bergman, H.M.; Samkian, A.E.; Schuster, N.J.; Handford, R.C.; Rothenberger, A.J.; Gomez-Bombarelli, R.; Nuckolls, C.; Tilley, T.D. Expanded [23]-Helicene with Exceptional Chiroptical Properties via an Iterative Ring-Fusion Strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 23421–23427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, G.R.; Patel, S.C.; Smith, P.W.; Levine, D.S.; Tilley, T.D. Expanded Helicenes: A General Synthetic Strategy and Remarkable Supramolecular and Solid-State Behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18456–18459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-J.; Yao, N.-T.; Diao, L.-N.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.-L.; Gong, H.-Y. A π-Extended Pentadecabenzo[9]Helicene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202300840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Ying, S.-W.; Liao, S.-D.; Zhang, L.; Du, J.-J.; Chen, B.-W.; Tian, H.-R.; Xie, F.-F.; Xu, H.; Deng, S.-L.; et al. Sulfur-Doped Quintuple [9]Helicene with Azacorannulene as Core. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202204334. [Google Scholar]

- Elm, J.; Lykkebo, J.; Sørensen, T.J.; Laursen, B.W.; Mikkelsen, K.V. Racemization Mechanisms and Electronic Circular Dichroism of [4]Heterohelicenium Dyes: A Theoretical Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 12025–12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedicke, C.; Stegemeyer, H. Resolution and Racemization of Pentahelicene. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970, 11, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, T.; Machleid, R.; Simon, M.; Golz, C.; Alcarazo, M. Enantioselective Synthesis of 1,12-Disubstituted [4]Helicenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5660–5664. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, K.; Segawa, Y.; Itami, K. Symmetric Multiple Carbohelicenes. Synlett 2019, 30, 370–377. [Google Scholar]

- Ravat, P. Carbo[N]Helicenes Restricted to Enantiomerize: An Insight into the Design Process of Configurationally Stable Functional Chiral PAHs. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 3957–3967. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bosson, J.; Labrador, G.M.; Jacquemin, D.; Lacour, J. Cationic [6]Helicenes: Tuning (Chir)Optical Properties up to the near Infra-Red. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 7751–7753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafedh, N.; Aloui, F.; Dorcet, V.; Barhoumi, H. Helically Chiral Functionalized [6]Helicene: Synthesis, Optical Resolution, and Photophysical Properties. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2018, 21, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, K.; Hafedh, N.; Chmeck, M.; Aloui, F. Photooxidation Pathway Providing 15-Bromo-7-Cyano[6]Helicene. Chiroptical and Photophysical Properties and Theoretical Investigation. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1217, 128399. [Google Scholar]

- Nakai, Y.; Mori, T.; Inoue, Y. Theoretical and Experimental Studies on Circular Dichroism of Carbo[N]Helicenes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 7372–7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y.; Mori, T.; Inoue, Y. Circular Dichroism of (Di)Methyl- and Diaza[6]Helicenes. A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M.S.; Darlak, R.S.; Tsai, L.L. Optical Properties of Hexahelicene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 6191–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, M.E.S.; Srebro, M.; Anger, E.; Vanthuyne, N.; Roussel, C.; Lescop, C.; Autschbach, J.; Crassous, J. Chiroptical Properties of Carbo[6]Helicene Derivatives Bearing Extended π-Conjugated Cyano Substituents. Chirality 2013, 25, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzlein, M.; Shoyama, K.; Würthner, F. A Highly Fluorescent Bora[6]Helicene Exhibiting Circularly Polarized Light Emission. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 2984–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vander Donckt, E.; Nasielski, J.; Greenleaf, J.R.; Birks, J.B. Fluorescence of the Helicenes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1968, 2, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.-L.; Li, M.; Lu, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-F. Advances in Helicene Derivatives with Circularly Polarized Luminescence. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 13793–13803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göbel, D.; Míguez-Lago, S.; Ruedas-Rama, M.J.; Orte, A.; Campaña, A.G.; Juríček, M. Circularly Polarized Luminescence of [6]Helicenes through Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer. Helv. Chim. Acta 2022, 105, e202100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, V.; Jean, M.; Vanthuyne, N.; Del Rio, N.; Matozzo, P.; Crassous, J.; Ruppert, R. Porphyrin- and Bodipy-Helicene Conjugates: Syntheses, Separation of Enantiomers and Chiroptical Properties. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 8924–8935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumagina, N.A.; Antina, E.V. Review of Advances in Development of Fluorescent Bodipy Probes (Chemosensors and Chemodosimeters) for Cation Recognition. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 505, 215688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudet, A.; Burgess, K. Bodipy Dyes and Their Derivatives: Syntheses and Spectroscopic Properties. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4891–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, I.S.; Misra, R. Design, Synthesis and Functionalization of Bodipy Dyes: Applications in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells (Dsscs) and Photodynamic Therapy (Pdt). J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 8688–8723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapani, M.; Castriciano, M.A.; Collini, E.; Bella, G.; Cordaro, M. Supramolecular Bodipy Based Dimers: Synthesis, Computational and Spectroscopic Studies. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 8118–8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barattucci, A.; Campagna, S.; Papalia, T.; Galletta, M.; Santoro, A.; Puntoriero, F.; Bonaccorsi, P. Bodipy on Board of Sugars: A Short Enlightened Journey up to the Cells. ChemPhotoChem 2020, 4, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barattucci, A.; Gangemi, C.M.A.; Santoro, A.; Campagna, S.; Puntoriero, F.; Bonaccorsi, P. Bodipy-Carbohydrate Systems: Synthesis and Bio-Applications. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 2742–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Fusè, M.; Bloino, J. Theoretical Investigation of the Circularly Polarized Luminescence of a Chiral Boron Dipyrromethene (Bodipy) Dye. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Yan, B. Recent Theoretical and Experimental Progress in Circularly Polarized Luminescence of Small Organic Molecules. Molecules 2018, 23, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, G.; Milone, M.; Bruno, G.; Santoro, A. Triphasic Circularly Polarized Luminescence Switch Quantum Simulation of a Topologically Chiral Catenane. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 3005–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, G.; Bruno, G.; Santoro, A. Ball Pivoting Algorithm and Discrete Gaussian Curvature: A Direct Way to Curved Nanographene Circularly Polarized Luminescence Spectral Simulation. FlatChem 2023, 42, 100567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, G.; Bruno, G.; Santoro, A. Vibrationally Resolved Deep–Red Circularly Polarised Luminescence Spectra of C70 Derivative through Gaussian Curvature Analysis of Ground and Excited States. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 391, 123268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (Dft-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, G.; Castiglioni, E.; Abbate, S.; Lebon, F.; Lightner, D.A. Experimental and Calculated Cpl Spectra and Related Spectroscopic Data of Camphor and Other Simple Chiral Bicyclic Ketones. Chirality 2013, 25, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016; Available online: https://gaussian.com/citation/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Moneva Lorente, P.; Wallabregue, A.; Zinna, F.; Besnard, C.; Di Bari, L.; Lacour, J. Synthesis and Properties of Chiral Fluorescent Helicene-Bodipy Conjugates. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 7677–7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobo, Y.; Yamamura, M.; Nakamura, T.; Nabeshima, T. Synthesis and Chiroptical Properties of a Ring-Fused Bodipy with a Skewed Chiral π Skeleton. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 2719–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algoazy, N.; Clarke, R.G.; Penfold, T.J.; Waddell, P.G.; Probert, M.R.; Aerts, R.; Herrebout, W.; Stachelek, P.; Pal, R.; Hall, M.J.; et al. Near-Infrared Circularly Polarised Luminescence from Helically Extended Chiral N,N,O,O-Boron Chelated Dipyrromethenes. ChemPhotoChem 2022, 6, e202200090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, C.; Nagahata, K.; Shirakawa, T.; Ema, T. Azahelicene-Fused Bodipy Analogues Showing Circularly Polarized Luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7813–7817. [Google Scholar]

- Zinna, F.; Bruhn, T.; Guido, C.A.; Ahrens, J.; Bröring, M.; Di Bari, L.; Pescitelli, G. Circularly Polarized Luminescence from Axially Chiral Bodipy Dyemers: An Experimental and Computational Study. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 16089–16098. [Google Scholar]

- Pecul, M.; Ruud, K. The OPTICAL activity of β,γ-Enones in Ground and Excited States Using Circular Dichroism and Circularly Polarized Luminescence. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, S.; Longhi, G.; Lebon, F.; Castiglioni, E.; Superchi, S.; Pisani, L.; Fontana, F.; Torricelli, F.; Caronna, T.; Villani, C.; et al. Helical Sense-Responsive and Substituent-Sensitive Features in Vibrational and Electronic Circular Dichroism, in Circularly Polarized Luminescence, and in Raman Spectra of Some Simple Optically Active Hexahelicenes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 1682–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, G.; Castiglioni, E.; Villani, C.; Sabia, R.; Menichetti, S.; Viglianisi, C.; Devlin, F.; Abbate, S. Chiroptical Properties of the Ground and Excited States of Two Thia-Bridged Triarylamine Heterohelicenes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2016, 331, 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Brémond, É.; Savarese, M.; Su, N.Q.; Pérez-Jiménez, Á.J.; Xu, X.; Sancho-García, J.C.; Adamo, C. Benchmarking Density Functionals on Structural Parameters of Small-/Medium-Sized Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, G.; Milone, M.; Bruno, G.; Santoro, A. Which Dft Factors Influence the Accuracy of 1h, 13c and 195pt Nmr Chemical Shift Predictions in Organopolymetallic Square-Planar Complexes? New Scaling Parameters for Homo- and Hetero-Multimetallic Compounds and Their Direct Applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 26642–26658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, G.; Santoro, A.; Nicolò, F.; Bruno, G.; Cordaro, M. Do Secondary Electrostatic Interactions Influence Multiple Dihydrogen Bonds? Aa-Dd Array on an Amine-Borane Aza-Coronand: Theoretical Studies and Synthesis. Chemphyschem 2021, 22, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, Q.; Helal, W.; Marashdeh, A. Accurate Predictions of the Electronic Excited States of Bodipy Based Dye Sensitizers Using Spin-Component-Scaled Double-Hybrid Functionals: A Td-Dft Benchmark Study. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 1704–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, J.S.; McCamant, D.W. The Best Models of Bodipy’s Electronic Excited State: Comparing Predictions from Various Dft Functionals with Measurements from Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 8238–8251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Durbeej, B. How Accurate are Td-Dft Excited-State Geometries Compared to Dft Ground-State Geometries? J. Comput. Chem. 2020, 41, 1718–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, I.; Khera, R.A.; Naveed, A.; Shehzad, R.A.; Iqbal, J. Designing the Optoelectronic Properties of Bodipy and Their Photovoltaic Applications for High Performance of Organic Solar Cells by Using Computational Approach. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 148, 106812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, M.; Barbosa, N.A.; Wieczorek, R.; Melnikov, M.Y.; Filarowski, A. Calculations of Bodipy Dyes in the Ground and Excited States Using the M06-2x and Pbe0 Functionals. J. Mol. Model. 2016, 22, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X.; Ma, X.; Fan, J. The Controllable of Bodipy Dimers without Installing Blocking Groups as Both Fluorescence and Singlet Oxygen Generators. Smart Mol. 2025, 3, e20240023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, C.A.; Zinna, F.; Pescitelli, G. Cpl Calculations of [7]Helicenes with Alleged Exceptional Emission Dissymmetry Values. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 10474–10482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 Suite of Density Functionals for Main Group Thermochemistry, Thermochemical Kinetics, Noncovalent Interactions, Excited States, and Transition Elements: Two New Functionals and Systematic Testing of Four M06-Class Functionals and 12 Other Functionals. Theor. Chem. Account. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chibani, S.; Laurent, A.D.; Le Guennic, B.; Jacquemin, D. Improving the Accuracy of Excited-State Simulations of Bodipy and Aza-Bodipy Dyes with a Joint Sos-Cis(D) and Td-Dft Approach. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014, 10, 4574–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chibani, S.; Le Guennic, B.; Charaf-Eddin, A.; Laurent, A.D.; Jacquemin, D. Revisiting the Optical Signatures of Bodipy with Ab Initio Tools. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 1950–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibani, S.; Le Guennic, B.; Charaf-Eddin, A.; Maury, O.; Andraud, C.; Jacquemin, D. On the Computation of Adiabatic Energies in Aza-Boron-Dipyrromethene Dyes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3303–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prlj, A.; Fabrizio, A.; Corminboeuf, C. Rationalizing Fluorescence Quenching in Meso-Bodipy Dyes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 32668–32672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamiya, V.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Shukla, A. Benchmarking Gaussian Basis Sets in Quantum-Chemical Calculations of Photoabsorption Spectra of Light Atomic Clusters. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 48261–48271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque-Prata, A.; Pinto, T.B.; Serpa, C.; Caridade, P.J.S.B. Performance of Functionals and Basis Sets in Calculating Redox Potentials of Nitrile Alkenes and Aromatic Molecules Using Density Functional Theory. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202300205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, G.; Santoro, A.; Cordaro, M.; Nicolò, F.; Bruno, G. Isoxazolone Reactivity Explained by Computed Electronic Structure Analysis. Chin. J. Chem. 2020, 38, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bella, G.; Bruno, G.; Santoro, A. Circular Dichroism Simulations of Chiral Buckybowls by Means Curvature Analyses. FlatChem 2023, 40, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikabata, Y.; Nakai, H. Local Response Dispersion Method: A Density-Dependent Dispersion Correction for Density Functional Theory. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2015, 115, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, V.; Biczysko, M.; Pavone, M. The Role of Dispersion Correction to Dft for Modelling Weakly Bound Molecular Complexes in the Ground and Excited Electronic States. Chem. Phys. 2008, 346, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huenerbein, R.; Grimme, S. Time-Dependent Density Functional Study of Excimers and Exciplexes of Organic Molecules. Chem. Phys. 2008, 343, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Settels, V.; Harbach, P.H.P.; Dreuw, A.; Fink, R.F.; Engels, B. Assessment of Td-Dft- and Td-Hf-Based Approaches for the Prediction of Exciton Coupling Parameters, Potential Energy Curves, and Electronic Characters of Electronically Excited Aggregates. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Functional | RMSD (Å) | |

|---|---|---|

| BODIPY-aza[7]helicene (1) (X = O) | BODIPY-aza[7]helicene (2) (X = S) | |

| B3LYP | 0.361 | 0.350 |

| CAM-B3LYP | 0.347 | 0.336 |

| ωB97XD | 0.395 | 0.248 |

| OLYP | 0.364 | 0.268 |

| M06-2X | 0.341 | 0.194 |

| MN15 | 0.372 | 0.202 |

| X3LYP | 0.356 | 0.347 |

| PBEPBE | 0.354 | 0.345 |

| B97D3 | 0.381 | 0.268 |

| APFD | 0.391 | 0.240 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bella, G.; Bruno, G.; Santoro, A. Theoretical Modeling of BODIPY-Helicene Circularly Polarized Luminescence. Organics 2025, 6, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/org6040053

Bella G, Bruno G, Santoro A. Theoretical Modeling of BODIPY-Helicene Circularly Polarized Luminescence. Organics. 2025; 6(4):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/org6040053

Chicago/Turabian StyleBella, Giovanni, Giuseppe Bruno, and Antonio Santoro. 2025. "Theoretical Modeling of BODIPY-Helicene Circularly Polarized Luminescence" Organics 6, no. 4: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/org6040053

APA StyleBella, G., Bruno, G., & Santoro, A. (2025). Theoretical Modeling of BODIPY-Helicene Circularly Polarized Luminescence. Organics, 6(4), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/org6040053