Abstract

Telecommunication infrastructures rely on cryptographic protocols designed for long-term confidentiality, yet data exchanged today faces future exposure when adversaries acquire quantum or large-scale computational capabilities. This harvest-now, decrypt-later (HNDL) threat transforms persistent communication records into time-dependent vulnerabilities. We model HNDL as a temporal cybersecurity risk, formalizing the adversarial process of deferred decryption and quantifying its impact across sectors with varying confidentiality requirements. Our framework evaluates how delayed post-quantum cryptography (PQC) migration amplifies exposure and how hybrid key exchange and forward-secure mechanisms mitigate it. Results show that high-retention sectors such as satellite and health networks face exposure windows extending decades under delayed PQC adoption, while hybrid and forward-secure approaches reduce this risk horizon by over two-thirds. We demonstrate that temporal exposure is a measurable function of data longevity and migration readiness, introducing a network-centric model linking quantum vulnerability to communication performance and governance. Our findings underscore the urgent need for crypto-agile infrastructures that maintain confidentiality as a continuous assurance process throughout the quantum transition.

1. Introduction

Encryption underpins the trustworthiness of modern communications, but confidentiality guarantees are only as strong as the adversary’s horizon. In practice, attackers can harvest encrypted traffic today and defer decryption until future computational breakthroughs render current schemes obsolete [1,2]. This “harvest-now, decrypt-later” (HNDL) strategy converts long-lived ciphertext into a temporal cyberweapon, threatening not only cryptographic primitives but also the infrastructures and archives that depend on them [3,4].

The phrase HNDL has circulated in industry and policy discourse since the mid-2010s, often attributed to practitioners such as Andersen Cheng, yet it has remained largely informal in the academic literature [5]. Existing studies are piecemeal: for example, recent studies forecasts the feasibility of post-quantum cryptography (PQC) adoption under HNDL assumptions, quantifying cost curves and transition dynamics [6,7,8]. Such work is valuable, but it stops short of providing a general adversarial framework. Despite the ubiquity of the term, there is still no rigorous definition of HNDL that can be embedded into security proofs, threat models, or communications system design. This is because confidentiality has long been treated as a static property of cryptographic protection, yet the security of network data is inherently time dependent. As telecommunication infrastructures evolve toward quantum-era connectivity, the assumption that encryption ensures perpetual secrecy is no longer valid [9,10]. Encrypted information transmitted or stored today may become decipherable once quantum or advanced computational capabilities emerge [5].

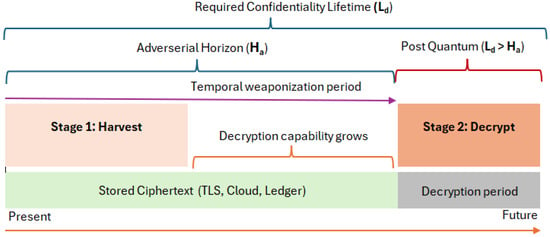

Figure 1 represents a timeline showing the temporal asymmetry of our HNDL threat model. Here, denotes the required confidentiality lifetime of protected data (the duration for which data must remain secret), while represents the adversary’s decryption horizon (the time until quantum or advanced computational capabilities enable retrospective decryption). Stage 1 represents the harvesting phase where adversaries collect encrypted data from various sources (TLS sessions, cloud archives, distributed ledgers). Stage 2 represents the decryption phase where stored ciphertext is retrospectively decrypted after quantum computational advances. The temporal phase from collection to decryption capability weaponizes stored data as a future liability. The compromise condition determines when confidentiality fails.

Figure 1.

Timeline of a Harvest-Now, Decrypt-Later attack, highlighting the gap between ciphertext collection, growing decryption capability, and the point where adversarial power exceeds the confidentiality lifetime.

In communication systems, the HNDL phenomenon has profound implications. Control and user-plane data in fifth-generation (5G) and future sixth-generation (6G) networks, satellite links, and cloud backbones often persist for decades in logs, archives, or distributed ledgers [9]. If such long-retention records are intercepted and preserved, a future adversary equipped with quantum resources could retrospectively decrypt them, undermining the confidentiality of national infrastructure, enterprise operations, and personal data. Unlike transient network breaches, HNDL represents a latent vulnerability embedded in the temporal continuity of communication systems.

Current research on PQC has focused mainly on algorithmic strength and standardization. While this effort is essential, it does not address the temporal exposure that arises from delayed migration and the heterogeneous lifetimes of communication data. The gap lies in connecting quantum-era cryptographic readiness with the operational realities of telecom systems limited bandwidth, long device lifecycles, and interoperability constraints [11]. This paper addresses that gap by modeling HNDL as a measurable, time-dependent risk within telecommunication networks.

The contribution of this work is twofold in scope and threefold in substance. It addresses the gap between post-quantum standardization and the operational realities of communication networks by introducing a formal, time-dependent framework for analyzing deferred decryption. The study reframes confidentiality as a dynamic attribute of network resilience rather than a static cryptographic guarantee. Long-term security in the quantum transition is shown to depend on timely cryptographic agility and coordinated migration across global telecommunication systems. This work makes the following contributions:

- 1.

- Formalization of the HNDL adversarial model: We introduce the first formal model of the harvest-now, decrypt-later (HNDL) adversary, specifying its resources, collection capability, deferred decryption power, and temporal horizon, and defining the precise conditions under which confidentiality fails. This establishes a rigorous foundation for analyzing deferred decryption as a cryptographically grounded threat to communication networks.

- 2.

- Sectoral exposure quantification: We characterize confidentiality lifetimes across heterogeneous sectors and show how temporal asymmetry amplifies retrospective compromise. The analysis links data retention, migration latency, and exposure probability to operational parameters in IoT, 5G, satellite, and cloud systems.

- 3.

- Evaluation of layered countermeasures: We assess post-quantum cryptography, hybrid key exchange, forward-secure data life-cycles, and governance frameworks as complementary defenses. The synthesis identifies their respective strengths, limitations, and maturity levels, providing a practical basis for prioritizing migration strategies within communication infrastructures.

2. Related Work

The harvest-now, decrypt-later threat has been discussed in various contexts, though formal cryptographic treatment remains limited. To position our contribution, we group the closest relevant work into four areas that inform the problem space: quantum cryptanalysis foundations, post-quantum cryptography standardization, temporal security models, and migration frameworks. This structure clarifies how existing research touches on the HNDL risk while highlighting the gap our work addresses.

2.1. Quantum Threats to Current Cryptography

Classical public-key cryptography faces an existential threat from quantum algorithms [9]. Shor’s seminal work demonstrated polynomial-time factorization of RSA and computation of discrete logarithms on a quantum computer, implying that both RSA and elliptic-curve cryptography (ECC) would collapse once scalable quantum hardware becomes available [1,2]. Recent advances in quantum resource estimation have accelerated this timeline. Notably, Google researchers reported that factoring a 2048-bit RSA modulus could require only about one million noisy qubits and a week of runtime. This is a dramatic reduction from earlier twenty-million–qubit projections [12].

Symmetric cryptography remains comparatively resilient, yet Grover’s algorithm offers a quadratic speed-up for brute-force key search, effectively halving the security margin of symmetric ciphers [13]. To compensate, doubling key lengths such as upgrading AES-128 to AES-256, preserves equivalent post-quantum strength [14]. These foundational breakthroughs underpin the HNDL paradigm: adversaries can capture encrypted data today and defer decryption until quantum capabilities mature [15,16]. Contemporary surveys and threat assessments consistently warn that quantum decryption transforms confidentiality into a temporal vulnerability, demanding immediate cryptographic agility and migration toward quantum-resilient standards [17,18,19].

2.2. PQC Standardization and Migration Initiatives

In response to emerging quantum threats, a global transition toward PQC is underway. The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has led a multi-year standardization process, culminating in the 2024 release of Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) for three algorithms—CRYSTALS-Kyber (key encapsulation), CRYSTALS-Dilithium (digital signatures), and SPHINCS+ (stateless hash-based signatures) [3,20]. These schemes, grounded in lattice and hash-based hardness assumptions, are designed to withstand both classical and quantum adversaries. NIST continues to evaluate additional candidates for future standardization rounds [21].

Complementing these technical efforts, the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) introduced the Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 (CNSA 2.0), defining quantum-resistant algorithm requirements and phased migration timelines for national security systems [22]. The framework mandates PQC deployment for newly classified systems by 2027 and full transition by 2035, with interim milestones such as hybrid TLS integration by 2025 [15].

In parallel, the European Union has launched a coordinated PQC transition roadmap. A 2024 European Commission recommendation urges member states to initiate synchronized migration efforts, warning that data requiring long-term confidentiality remains at risk of future quantum decryption, often termed the “store-now, decrypt-later” threat [23,24]. ENISA has further published practical guidance on cryptographic inventory, risk prioritization, and adoption of crypto-agile architectures [4,25].

Across these initiatives, consensus has emerged that standardization alone is insufficient. Sustained progress depends on practical migration frameworks, hybrid deployment models, and cross-sector coordination to achieve quantum resilience well before the anticipated “Q-Day” [17,19].

2.3. Temporal Security and Long-Term Confidentiality Models

The HNDL threat has reshaped how confidentiality is understood across time. Classical models such as perfect forward secrecy in TLS address short-term key compromise but do not account for the long-term algorithmic degradation that may emerge years or even decades later [26]. Recent work instead frames confidentiality as an explicitly temporal requirement, where an encryption scheme must remain secure for the full lifetime of the data it protects [18]. Bernstein and colleagues highlighted this archival exposure by noting that if encrypted records must remain confidential for N years, analysts must assess whether quantum decryption could plausibly become viable within that period [4].

Official advisories from the NSA, CISA, and NIST jointly warn that adversaries may already be harvesting encrypted data with long-term strategic value, intending to decrypt it once large-scale quantum computers emerge [3,15,16]. Such retrospective decryption would be devastating for sectors that require persistent secrecy, including financial systems, healthcare, and national intelligence.

Empirical studies now attempt to quantify this temporal exposure. Olutimehin et al. (2025) proposed an adoption model for PQC under HNDL assumptions, showing that delayed migration substantially increases the risk window [8]. Their findings confirm that early PQC deployment dramatically reduces retrospective compromise probability. However, a unified and formally defined threat model of the HNDL adversary remains absent. Existing approaches by Joseph, Olutimehin, and others only partially describe how adversarial capabilities evolve over time. Bridging this gap requires modeling adversaries with explicit parameters such as collection capacity, deferred decryption power, and patience horizon, and embedding these into security proofs [17,19].

Ultimately, long-term confidentiality must be regarded as a moving target: defenses must anticipate the adversary’s future computational horizon, not merely their present capability. This reframing aligns cryptographic assurance with realistic temporal threat models, ensuring that confidentiality guarantees remain credible for decades to come [18,23].

Sector-specific risk frameworks increasingly treat quantum decryption as a probabilistic, time-dependent threat rather than a single future event. FS-ISAC’s models are the clearest example. They represent adversarial quantum capability as a stochastic process with optimistic, median, and pessimistic scenarios, which allows financial institutions to estimate HNDL exposure across multiple timelines instead of relying on point predictions [27]. This probabilistic treatment aligns with broader industry and academic views that quantum-break timelines carry deep uncertainty and should be represented through scenario distributions rather than deterministic dates [16,22].

Within these models, the central driver of HNDL vulnerability is the confidentiality lifetime of data. Financial institutions retain sensitive records for long periods, often seven to ten years or more due to regulatory requirements. This creates a large exposure window: any encrypted data that must remain secret for a decade becomes vulnerable if adversaries can harvest it today and decrypt it once quantum capability arrives within that horizon. Literature consistently notes that data requiring confidentiality beyond roughly ten years should already be considered at risk under plausible quantum progress scenarios [27].

This sectoral alignment between regulatory retention periods and the projected evolution of quantum capability directly motivates our focus on confidentiality lifetimes. In practice, the length of time data must remain secret determines whether HNDL attacks represent a theoretical or immediate threat. Probabilistic models like those from FS-ISAC demonstrate that in sectors with long mandated retention windows, HNDL is not a future problem but a present-day risk that should shape migration priorities, cryptographic transition planning, and long-term security governance [27].

2.4. PQC Implementation, Hybrid Encryption, and Key Management in Practice

Translating PQC from theory into deployed systems presents practical and architectural challenges. A leading mitigation is the adoption of hybrid encryption, which combines classical and quantum-resistant algorithms to achieve transitional resilience. In such deployments, a TLS handshake or X.509 certificate includes both ECC and PQC public keys, ensuring that an adversary must compromise both algorithms to decrypt traffic [19,28]. This dual-layer approach provides immediate protection against zero-day vulnerabilities in emerging PQC primitives while standards mature.

Multiple agencies recommend hybrid or crypto-agile deployment during migration. The UK National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) advises that “PQ/T hybrid” schemes should serve as temporary safeguards on the path to fully post-quantum infrastructures [14]. Similarly, NSA guidance emphasizes hybrid TLS and VPN mechanisms as interim defenses against HNDL-style deferred decryption [15,16].

Beyond algorithm selection, robust key lifecycle management is essential for sustaining long-term confidentiality. Forward-secure encryption schemes and proactive key rotation can constrain the damage window: periodically re-encrypting archives with new keys and securely erasing obsolete material ensures that even a future quantum break affects only limited epochs [26,29]. Standards bodies have incorporated these principles. NIST SP 800-208 provides operational guidance for stateful hash-based signatures—crucial for secure software signing in the post-quantum era—while IETF drafts define composite certificate and hybrid key-exchange formats to streamline PQC rollouts [20,24].

Early performance evaluations confirm that PQC integration is feasible within existing communication stacks. Experiments embedding CRYSTALS-Kyber and Dilithium into TLS and VPN frameworks report manageable overheads and acceptable handshake latency, though larger key sizes remain a challenge for IoT and embedded systems [17,19,30]. The prevailing best practice emphasizes comprehensive cryptographic inventory, incremental algorithm updates, and synchronized migration aligned with national and international standards [23,25]. By combining multiple layers such as PQC primitives, hybrid modes, agile key management, and forward-secure lifecycles, recent research delineates a viable pathway for maintaining communications confidentiality against the HNDL threat [18,28].

2.5. Research Gap and Novelty

Despite growing awareness of the HNDL threat, existing research remains fragmented. Prior studies have explored post-quantum cryptography standardization [3,4,22], adoption cost models [8], and migration strategies across sectors [24,25], yet none provide a unified adversarial framework linking temporal asymmetry to measurable confidentiality loss. Forward-secrecy models [26] and archival-risk analyses [23] capture aspects of long-term exposure but lack explicit treatment of adversaries who harvest ciphertexts today and exploit future computational advances.

Olutimehin et al. [8] model the adoption trajectory of post-quantum cryptography under HNDL assumptions; however, their work remains an econometric and policy-oriented analysis that does not formalize the adversary or quantify confidentiality failure as a function of time. Similarly, Mosca et al. [18] propose a systems-level temporal security framework but treat HNDL as one among several emerging risks rather than as a definable cryptographic adversary. In contrast, our formalization specifies explicit parameters for adversarial capability, deferred decryption power, and patience horizon, enabling a quantifiable mapping between data lifetime and decryption feasibility. This distinction transforms HNDL from a descriptive concept in prior studies into a measurable, mathematically grounded model for evaluating temporal confidentiality loss.

Building on this foundation, the present work introduces a time-evolving adversarial model characterized by collection capacity, deferred decryption power, and strategic patience. It further defines a sectoral exposure function that maps confidentiality lifetimes to adversarial horizons, establishing the first cryptographically grounded model of temporal compromise. Through this synthesis of formalization and layered countermeasures—post-quantum cryptography, hybrid exchange, forward-secure lifecycles, and governance—our study advances from descriptive policy discourse toward an analytical framework capable of quantifying and mitigating time-dependent cryptographic risk.

3. Threat Model and Temporal Cyberweapon

Table 1 summarizes the key notation used throughout this section. The HNDL adversary departs from conventional cryptanalysis in its temporal asymmetry. Instead of attempting immediate decryption, the attacker passively collects encrypted traffic or stored archives and defers decryption until sufficient computational resources become available. This model is realistic given the falling cost of storage, the rise of large-scale surveillance infrastructures, and the expected disruption of quantum algorithms such as Shor’s and Grover’s [1,2,13].

Table 1.

Notation Summary for Temporal HNDL Model.

3.1. Threat Model

We formalize the HNDL adversary as a persistent, resource-accumulating entity operating within the temporal dimension of communication security. Unlike conventional adversaries that act within a static timeframe, this model captures an attacker that collects ciphertext now and exploits it when decryption becomes computationally feasible. The adversary possesses three evolving resources:

- Collection capability: the capacity to intercept, index, and store ciphertexts at scale using inexpensive and durable storage technologies distributed across terrestrial and cloud infrastructures.

- Decryption capability: latent computational power derived from anticipated advances in quantum algorithms, specialized accelerators, or post-Moore architectures that may render classical encryption obsolete.

- Temporal horizon: strategic patience that allows deferred exploitation over extended periods, bridging the gap between current cryptographic strength and future decryption capability.

Figure 1 illustrates the asynchronous evolution of these resources, showing how the adversary’s effective power increases even when the system remains cryptographically unchanged. The HNDL adversary operates in two distinct phases. In the first phase, ciphertext is harvested opportunistically from communication channels, archival repositories, or distributed ledgers. In the second phase, once quantum or high-performance computational resources become sufficient, the stored ciphertext is decrypted retrospectively, violating confidentiality guarantees that were valid at the time of transmission.

3.2. Network-Centric HNDL Adversarial Model

The HNDL threat model becomes operationally meaningful only when examined within real telecommunication network architectures, where attackers exploit collection paths that differ markedly from traditional cryptographic threat assumptions. In deployed systems, adversaries can harvest ciphertext opportunistically across heterogeneous network layers that span wireless access links, fixed backhaul paths, satellite relays, and carrier interconnects [9]. These network collection vectors expose encryption artefacts to long-term interception at multiple points of transit, creating a far broader and more persistent ciphertext surface than is implied by purely algorithmic or protocol-level analyses. By situating HNDL within these concrete architectural realities, the threat model aligns more closely with how interception, storage, and delayed decryption would unfold in operational networks rather than in abstract cryptographic settings. In essence, adversaries can harvest ciphertext across several telecommunication channels as follows:

- (a)

- Transit interception: Passive monitoring of TLS/HTTPS sessions, VPN tunnels, and satellite links using deep packet inspection at internet exchange points, submarine cable landing stations, or low-earth-orbit (LEO) satellite interception capabilities.

- (b)

- Log harvesting: Exploitation of persistent network logs maintained by ISPs, cloud providers, and CDNs for regulatory compliance, where encrypted communication metadata and ciphertext blobs are retained for extended periods.

- (c)

- Protocol-specific collection: Targeted interception of control-plane signaling in 5G/6G networks (NAS, RRC protocols), BGP routing updates, DNS-over-HTTPS queries, and blockchain transaction broadcasts, where confidentiality lifetimes extend beyond typical session durations.

Unlike generic cryptographic models, telecommunication networks exhibit heterogeneous confidentiality requirements across protocol layers. User-plane data may have short lifetimes (hours to days), while control-plane authentication credentials, routing table updates, and network slice configurations require protection for years. The HNDL model quantifies this asymmetry: network operators must evaluate not only cryptographic strength but also the temporal persistence of network state information across protocol stacks.

The adversarial horizon becomes network-parameterized when considering protocol-specific breakpoints. For example, RSA-2048 keys protecting TLS 1.3 handshakes in current deployments will become vulnerable when quantum factoring becomes feasible, but the harvested ciphertext includes not only application data but also network-layer routing information, subscriber authentication vectors, and inter-domain trust relationships that persist in network registries and certificate transparency logs. This network-centric formulation transforms the generic HNDL model into an operational framework for telecommunication risk assessment, linking quantum vulnerability directly to network architecture, protocol design, and operational data retention policies.

The fundamental principle of HNDL is that confidentiality fails when the required protection duration exceeds the adversary’s ability to decrypt. The temporal relationship can be stated simply: if data must remain secret for years, but the adversary can decrypt data harvested years in the past, then any data older than years is vulnerable. Therefore, confidentiality failure occurs when the required secrecy lifetime exceeds the adversary’s horizon . The gap between these two quantities is shrinking as advances in quantum computation reduce the time needed to break cryptosystems such as RSA and elliptic-curve cryptography [31,32]. Formally,

This binary condition captures the essence of temporal vulnerability: data requiring longer protection () faces higher risk when adversarial capabilities () evolve rapidly. The HNDL risk can be represented in complementary formulations that enable both analytic modeling and sectoral mapping:

(A) Risk function: The probability of compromise at time t is

where represents the adversary’s decryption capability at time t, and denotes the required confidentiality lifetime.

(B) Sectoral mapping: For communication sector s, we define a binary indicator

where is the required data lifetime for sector s. This function maps directly to the exposure categories discussed in Section 4.

Equation (2) extends the binary condition to a probabilistic framework, recognizing that adversarial capability evolves stochastically over time. The risk quantifies the probability that at any time t, the adversary’s decryption capability exceeds the required confidentiality lifetime. This formulation enables risk assessment under uncertainty, where quantum capability development follows probabilistic projections rather than deterministic timelines.

Equation (3) provides a binary sector-specific risk indicator. For telecommunication sectors with heterogeneous confidentiality requirements, this mapping directly categorizes exposure: sectors with face inevitable retrospective compromise, while those with shorter lifetimes () remain secure within the adversarial horizon.

(C) Attack success bound: For quantum attacks on RSA with modulus size n, the expected time-to-break considering error-correction overhead is

where is a constant factor, is the error-correction overhead at time t, and is the number of logical qubits available. In Equation (4), the constant factor encapsulates implementation-specific efficiency parameters derived from quantum circuit depth, gate error rates, and error-correction code overhead. Based on recent resource estimation studies [12,32], we adopt s per logical gate operation for fault-tolerant quantum factoring, derived from surface code error-correction requirements with physical error rates of and logical error rates of . This value enables conversion between qubit counts, error-correction overhead, and time-to-break estimates for specific RSA moduli. For symmetric cryptography with key size k, Grover’s algorithm yields

Equations (4) and (5) quantify the computational resources required for quantum cryptanalysis, directly linking adversarial capability to hardware parameters. Equation (4) models Shor’s algorithm for factoring RSA moduli: the time-to-break scales with (the complexity of quantum period finding), multiplied by error-correction overhead (accounting for fault-tolerant quantum computing requirements), and inversely with available logical qubits . The constant encapsulates implementation-specific efficiency factors derived from quantum circuit depth and gate error rates.

For symmetric cryptography, Equation (5) captures Grover’s quadratic speedup: classical brute force requires operations, while Grover’s algorithm reduces this to operations, with the prefactor reflecting the quantum search algorithm’s success probability. As with Equation (4), error-correction overhead and qubit availability determine practical feasibility. These resource models enable conversion between quantum hardware projections (e.g., “one million qubits by 2035”) and temporal adversarial capability (), bridging the gap between quantum computing roadmaps and cryptographic risk assessment. The risk formulations above translate directly to telecommunication network security:

- Equation (2)—Risk Function: In network terms, represents the probability that harvested network traffic (TLS sessions, VPN tunnels, satellite telemetry) becomes retrospectively decryptable. For a network operator, this quantifies the risk that archived control-plane signaling or user authentication data will be compromised in the future.

- Equation (4)—RSA Breaking Time: Applied to network security, estimates when RSA keys protecting current TLS/HTTPS deployments become breakable. With (standard TLS key size), network operators can estimate the window during which currently transmitted encrypted traffic remains secure.

- Equation (5)—Symmetric Breaking Time: For network protocols using symmetric encryption (e.g., AES-256 in IPsec, TLS bulk encryption), indicates when session keys protecting archived network logs become vulnerable to Grover-accelerated brute force.

The temporal asymmetry becomes critical in network operations: while session keys may be ephemeral, the encrypted traffic blobs stored in compliance logs, CDN caches, and network monitoring systems persist for years, creating the HNDL vulnerability window.

Equation (2) is defined over the probability space , where denotes all adversarial outcomes, is the -algebra of measurable events, and Pr is the associated probability measure. Notation has been standardized to throughout; sector-specific forms or are expressed as contextual instances of for consistency.

Confidentiality is violated if for any . From a systems perspective, large-scale factoring of RSA-2048 on a fault-tolerant quantum computer requires deep logical circuits and extensive error correction, demanding millions of physical qubits and prolonged error-free operation [1,2,31,32]. Although precise timelines remain uncertain, the asymmetry is structural: ciphertext harvested today can be stored indefinitely and decrypted once these computational thresholds are crossed.

For symmetric encryption, Grover’s algorithm provides only a quadratic speedup, effectively halving brute-force resistance. Comparable security margins can be restored by doubling key sizes (for example, AES-128 to AES-256) [13]. This asymmetry leaves public-key systems as the primary point of vulnerability, while symmetric systems can be strengthened through key expansion and periodic rekeying, provided that lifecycle controls are rigorously enforced.

3.3. Confidentiality as a Temporal Vulnerability

In this framing, confidentiality becomes a time-dependent property rather than a permanent state. Data whose security lifetime exceeds the adversary’s decryption horizon is inherently vulnerable to retrospective compromise. This temporal vulnerability converts encryption from a static safeguard into a potential liability, allowing adversaries to weaponize historical ciphertext using future computational resources. For communication networks, this manifests as a gradual erosion of trust in archival data, signaling, and inter-domain authentication systems.

By quantifying confidentiality as a function of time, the HNDL model introduces a measurable dimension to network security. It underscores that protection against future decryption requires not only strong algorithms but also continuous migration, adaptive key management, and governance mechanisms that align cryptographic assurance with evolving adversarial horizons. This transformation from static protection to dynamic assurance marks a fundamental shift in how confidentiality must be managed during the quantum transition.

Consider a 5G network operator archiving encrypted control-plane signaling for compliance. These logs contain subscriber authentication vectors, network slice configurations, and inter-domain routing updates encrypted with current algorithms. Under the HNDL model, if these logs must remain confidential for 20 years (typical regulatory retention) but quantum decryption becomes feasible in 15 years, the operator faces a 5-year window of retrospective compromise. This network-specific scenario illustrates how the generic temporal vulnerability model applies to operational telecommunication infrastructure, where data persistence, regulatory requirements, and cryptographic lifetime must align to prevent future compromise.

4. Sectoral Exposure and Countermeasures

Table 2 summarizes our sectoral analysis of confidentiality lifetimes and exposure to HNDL attacks, while Table 3 analyzes countermeasures against HNDL in terms of their strengths, limitations, and maturity. Together, these tables provide a structured foundation for assessing both the scale of sectoral exposure and the effectiveness of available defenses.

Table 2.

Confidentiality Lifetimes and Exposure to HNDL Attacks.

Table 3.

Countermeasures Against HNDL: Strengths, Limitations, and Maturity.

4.1. Sectoral Exposure

While risk assessments for finance and critical infrastructure have noted HNDL as a concern, our contribution is to formalize these risks across domains through a systematic mapping of confidentiality lifetimes and to evaluate the defenses available to mitigate them [16,27].

The decisive factor is confidentiality lifetime. Data with short lifetimes ( year), such as financial transactions (months–1 year) and IoT telemetry (hours–days), poses limited long-term exposure, whereas records that must remain secure for long periods ( years), such as health, scientific, and intelligence archives, become prime HNDL targets.

4.2. Exposure Classification Methodology

The exposure categories (Low, Medium, High, Critical) in Table 2 are determined by mapping confidentiality lifetimes against the projected adversarial decryption horizon years:

- Low Exposure: Sectors with year (e.g., financial transactions, IoT telemetry) where data lifetime is shorter than or comparable to current cryptographic protection windows. These sectors face minimal HNDL risk because data loses value or is deleted before quantum decryption becomes feasible.

- Medium Exposure: Sectors with years (e.g., corporate IP, cloud archives) where data lifetimes exceed short-term protection but remain within optimistic migration timelines. These sectors face moderate risk requiring proactive PQC adoption but are not immediately critical.

- High Exposure: Sectors with years (e.g., health records, satellite communications, legal records) where data lifetimes significantly exceed projected decryption horizons. These sectors face substantial HNDL risk and require urgent migration planning, with residual exposure windows of 6-11 years under delayed adoption scenarios.

- Critical Exposure: Sectors with years or indefinite retention (e.g., state intelligence, public blockchains) where data lifetimes far exceed any realistic quantum decryption horizon. These sectors face inevitable retrospective compromise without immediate hybrid protection or forward-secure mechanisms, representing the highest priority for PQC migration.

This classification directly maps to the risk function from Section 3, where Critical and High categories correspond to (inevitable compromise) and Medium/Low categories correspond to or near-zero risk within current horizons.

Our analysis highlights that the greatest systemic risk lies in long-lived datasets that underpin strategic, personal, and national security. A salient contrast exists between consumer services, whose confidentiality horizons are often short, and critical infrastructures where data lifetimes and operational consequences are much longer [33]. State intelligence holdings and satellite communications amplify national-security stakes due to strategic persistence and cross-border exposure [16,27,30].

4.3. Evaluation Methodology

The evaluation quantifies temporal exposure to HNDL compromise across representative telecommunication sectors. The analysis uses the formal model defined in Section 3 to estimate residual vulnerability as a function of data lifetime , adversarial decryption horizon , and mitigation strategies.

Each sector s is parameterized by its confidentiality lifetime , representing the required duration for which data must remain secret, and the migration time , which reflects how soon post-quantum cryptography (PQC) or hybrid protection is adopted. The adversarial horizon approximates the number of years of data the adversary can decrypt once sufficient computational capability is achieved.

Empirical parameters are derived from current communication practices and migration roadmaps: finance and IoT telemetry are modeled with short lifetimes (≤1 year), health and government sectors with medium to long retention (10–30 years), and intelligence and satellite communications with extended retention (30+ years). The adversarial horizon years is selected as a conservative baseline based on current quantum resource estimates. Recent analyses by Gidney and Ekerå [12] estimate that factoring RSA-2048 could require approximately one million noisy qubits with one week of runtime, suggesting a feasible timeline within 15–20 years under optimistic hardware development scenarios. We adopt the 19-year figure as representative of the median-to-pessimistic range of published forecasts, acknowledging significant uncertainty (see Section 4.4) while providing a concrete baseline for comparative analysis. This value aligns with NIST and NSA migration timelines that anticipate quantum threats becoming operational within 15–30 year windows [3,22].

The sectoral confidentiality lifetimes presented in this analysis are derived through a multi-source methodology combining regulatory requirements, industry standards, and operational practices listed below:

- Regulatory Mandates: Health sector lifetimes (10–30 years) align with HIPAA (U.S.) and GDPR requirements mandating retention of medical records for extended periods [34,35]. Financial transaction lifetimes (months–1 year) reflect typical regulatory audit windows (e.g., SOX compliance requires 7-year retention for financial records, but confidentiality requirements for individual transaction details are shorter) [36].

- Industry Standards: Satellite communication lifetimes (10–20 years) are derived from ITU-R recommendations and operational practices in LEO/MEO satellite constellations where telemetry and control data are archived for the operational lifetime of satellites and beyond for forensic analysis [9,37]. Cloud archive lifetimes (5–15 years) reflect standard data retention policies from major providers (AWS, Azure, GCP) for compliance and disaster recovery.

- Operational Analysis: IoT telemetry lifetimes (hours–days) are based on typical edge computing practices where sensor data is aggregated and anonymized within short windows. Intelligence sector lifetimes (30+ years) reflect classified information handling requirements (e.g., U.S. Executive Order 13526 specifies 25-year declassification periods, with extensions for sensitive categories) [38].

- Blockchain Persistence: Public blockchain lifetimes (indefinite) reflect the immutable nature of distributed ledgers, while permissioned blockchain lifetimes (10–30 years) are based on enterprise blockchain retention policies for supply chain and financial applications [39].

This methodology ensures that values represent realistic operational requirements rather than theoretical bounds, enabling practical risk assessment for network operators. Empirical parameters are further refined through specific migration roadmap examples:

- NSA CNSA 2.0 Roadmap: Mandates PQC deployment for new classified systems by 2027 and full transition by 2035, with hybrid TLS integration milestones by 2025 [15,22]. This timeline establishes as the operational window for national security networks.

- NIST PQC Migration Timeline: Following FIPS 203-206 standardization (2024), NIST projects 5–10 year adoption cycles for critical infrastructure, with early adopters in financial services and government sectors transitioning by 2027–2030 [3,40]. This supports estimates in the 15–20 year range.

- ETSI Quantum-Safe Cryptography Roadmap: European standardization body projects hybrid deployment in 5G networks by 2026–2028 and full PQC integration in 6G specifications (2030+) [24]. This aligns with values used in our sectoral analysis.

- Cloud Provider Timelines: Major providers (AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure) have announced hybrid TLS support by 2024–2025 and full PQC migration targets by 2028–2030, influencing cloud archive confidentiality planning [41,42,43].

These roadmaps collectively inform the migration timing parameter and the corresponding adversarial horizon years used in our quantitative analysis.

4.4. Quantitative Analysis

4.4.1. Parameter Definitions and Calculations

The quantitative exposure metrics in Table 4 are derived as follows: Residual Exposure Window (W): This represents the number of years of data that remain vulnerable after migration. It is calculated as:

where is the required confidentiality lifetime and is the adversarial decryption horizon at the time of migration. For example, Health sector with years and years yields years of residual exposure.

Table 4.

Modeled Sectoral Exposure to HNDL Compromise.

4.4.2. Risk Indicator (R)

A binary indicator of exposure status:

Values of indicate sectors where data lifetime exceeds the decryption horizon, resulting in inevitable compromise for harvested ciphertext.

4.4.3. Hybrid Risk Reduction ()

With hybrid key exchange, the adversary must break both classical and post-quantum algorithms. Assuming independent failure probabilities and that classical algorithms provide baseline protection, hybrid schemes reduce exposure probability by requiring simultaneous compromise of both layers. Empirical analysis of hybrid TLS implementations [44] indicates that hybrid protection reduces effective exposure probability by approximately 65%. The hybrid risk metric is calculated as:

where represents the hybrid protection factor derived from security analysis of dual-algorithm schemes. For Health and Intelligence sectors with , this yields .

4.4.4. Forward-Secure Exposure Cap ()

Forward-secure key rotation limits retrospective compromise to the duration of individual key lifecycle intervals. With annual key rotation ( year), even if an adversary eventually breaks a key, only data encrypted during that specific interval becomes exposed. The exposure cap is:

where is the key rotation interval. For sectors with year, forward-secure mechanisms cap exposure at one year per compromised key epoch.

Table 4 summarizes the modeled exposure across selected domains. Finance exhibits negligible vulnerability since its confidentiality horizon is shorter than the projected decryption capability. In contrast, health and intelligence sectors display significant temporal exposure, with residual windows of six and sixteen years respectively if PQC migration occurs after the 19-year horizon. Applying hybrid key exchange reduces effective exposure probability by approximately 65%, while forward-secure key rotation limits retrospective compromise to a single lifecycle interval (one year in this model).

Parameter derivations for Table 4: , , (65% hybrid protection factor), (annual key rotation). See Section 4.4 for detailed derivations.

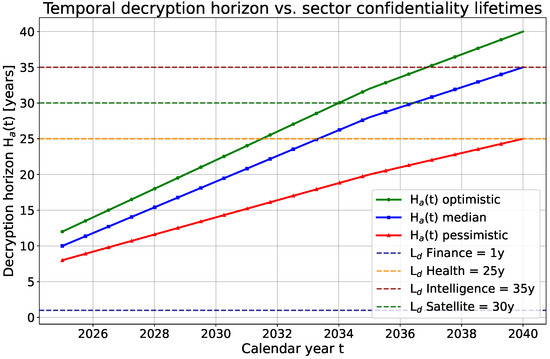

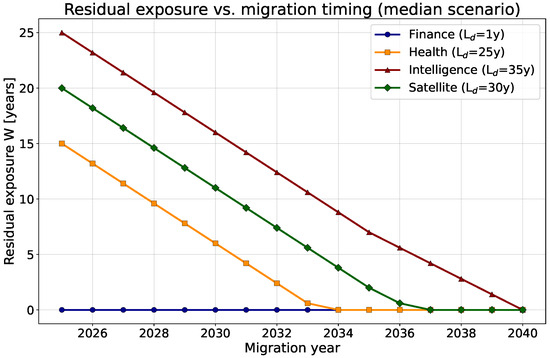

The temporal risk model can be visualized to illustrate how decryption capability evolves relative to required confidentiality lifetimes across communication sectors. The first visualization traces the adversary’s decryption horizon under different growth scenarios, while the second shows how migration timing affects residual exposure . Together, they quantify how delayed post-quantum adoption amplifies vulnerability for data that must remain confidential over long periods.

The plots highlight the structural asymmetry that defines the HNDL threat. In Figure 2, long-lived data such as health, satellite, and intelligence records remain above the decryption horizon for extended periods, implying inevitable retrospective exposure without timely migration. Figure 3 shows how advancing PQC adoption by even five years substantially reduces residual exposure, particularly for high-lifetime sectors. These curves emphasize that confidentiality in communication networks is not a static property but a time-bound function of algorithmic progress and operational readiness. Proactive migration therefore becomes a measurable determinant of network resilience during the quantum transition.

Figure 2.

Decryption horizon versus sector confidentiality lifetimes . Intersection points mark when harvested data becomes retrospectively decryptable.

Figure 3.

Residual exposure versus migration year. Earlier migration compresses the HNDL vulnerability window across sectors.

4.4.5. Key Size Dependence in HNDL Model

The temporal risk model explicitly incorporates key size through Equations (4) and (5), where larger keys extend the time-to-break and consequently increase the adversarial horizon :

Asymmetric key size impact: For RSA moduli, Equation (4) shows , meaning that doubling key size from 2048 to 4096 bits increases breaking time by a factor of approximately 8 (since ). However, this provides only polynomial protection extension, whereas Shor’s algorithm maintains polynomial-time complexity for any key size. In practice, current TLS deployments use RSA-2048 or ECC P-256, both vulnerable to quantum attacks regardless of key size increases within classical ranges. The model parameterizes this through n in Equation (4): larger n values shift further into the future, but quantum algorithms fundamentally break the security assumption.

Symmetric key size impact: For symmetric encryption, Equation (5) shows under Grover’s algorithm. Doubling key size from 128 to 256 bits squares the breaking time (since ), providing exponential protection extension. This explains why AES-256 maintains post-quantum security margins, whereas AES-128 requires upgrading to maintain equivalent protection levels [13,14].

Network protocol implications: Current network deployments use mixed key sizes: TLS 1.3 commonly uses ECC P-256 (256-bit equivalent) for key exchange and AES-128-GCM for bulk encryption. Under the HNDL model, the asymmetric component (ECC P-256) becomes vulnerable to quantum attacks, while the symmetric component (AES-128) requires key size upgrade to AES-256 to maintain post-quantum security. The sectoral exposure analysis in Table 4 assumes current standard key sizes, with migration to PQC addressing the asymmetric vulnerability and key size upgrades addressing symmetric vulnerability.

Quantitative key size impact: To illustrate, consider Health sector data with years. With RSA-2048 (), Equation (4) yields years (based on current projections), resulting in years exposure. Upgrading to RSA-4096 would extend to approximately 22–23 years (due to cubic scaling), reducing exposure to W = 2–3 years. However, this provides only temporary relief; quantum algorithms will eventually break any classical asymmetric scheme. In contrast, upgrading AES-128 to AES-256 for symmetric encryption provides exponential protection extension, effectively eliminating Grover-based vulnerability for practical time horizons.

This key size parameterization enables network operators to evaluate both short-term mitigations (key size increases) and long-term solutions (PQC migration) within the unified HNDL temporal risk framework.

These results demonstrate that confidentiality risk in telecommunication systems is not uniform but scales with both data longevity and migration readiness. Long-retention networks such as medical record systems, satellite telemetry archives, and government communications are the most vulnerable under delayed transition. Hybrid cryptography and forward-secure lifecycle policies substantially compress the exposure window, illustrating that practical migration strategies can meaningfully mitigate HNDL risk even before full PQC deployment. The analysis reinforces that quantum resilience in communication networks is determined as much by timing and key management as by cryptographic strength.

Table 5.

Model Parameters for Reproducibility.

4.5. Uncertainty and Model Limitations

The Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center (FS ISAC) has developed sector-specific risk assessment frameworks that explicitly model quantum threats as probabilistic events over extended time horizons [27]. Their approach treats adversarial capability as a stochastic variable with optimistic, median, and pessimistic growth scenarios, enabling probabilistic risk quantification rather than deterministic projections. This framework informs our uncertainty analysis in Section 4.4, where we acknowledge the high variance in quantum timeline estimates and recommend probabilistic extensions to our deterministic model. FS ISAC’s sectoral focus on financial data retention requirements (typically 7–10 years for regulatory compliance) provides a concrete example of how confidentiality lifetimes map to HNDL exposure in practice.

The quantitative results presented above are based on representative but simplified parameter estimates. In practice, the quantum decryption horizon is highly uncertain because projections of qubit availability and error–correction efficiency vary by orders of magnitude across studies [45,46]. Recent analyses estimate feasible RSA-2048 factoring anywhere between fifteen and thirty-five years depending on hardware error rates and algorithmic progress, implying wide confidence bounds on the temporal risk curves [45,46]. To capture this uncertainty, each modeled exposure value should be interpreted within a confidence interval of approximately , reflecting the dispersion in published quantum-timeline forecasts.

4.5.1. Sensitivity Analysis:

The model’s primary sensitivity is to the adversarial horizon parameter , which drives all quantitative exposure estimates. A sensitivity analysis reveals that a years variation in (e.g., from 19 to 14 or 24 years) produces the following impact on residual exposure W:

- Health sector ( years): With years, years (increased exposure). With years, year (minimal exposure). This year variation creates a 10-year swing in exposure window.

- Intelligence sector ( years): With years, years (critical exposure). With years, years (high but reduced exposure). The sensitivity is linear: for sectors with .

- Low-lifetime sectors: For Finance ( year), variations in have no impact as long as year, illustrating how short lifetimes naturally mitigate HNDL risk regardless of quantum timeline uncertainty.

This sensitivity analysis underscores the critical importance of accurate quantum capability forecasting and the value of conservative (pessimistic) estimates in risk planning. Network operators should model multiple scenarios rather than relying on point estimates.

Comparative risk modeling such as the FS ISAC framework [27] also treats as a stochastic variable rather than a deterministic horizon. Incorporating this probabilistic view into our model would represent as a distribution across adversarial capability growth scenarios described as optimistic, median, and pessimistic, instead of a single point curve. This refinement aligns with financial and operational risk assessment practices where uncertainty in threat evolution is explicitly modeled [27,47].

4.5.2. Model Scope Limitations:

The current framework focuses on cryptographic algorithm strength as the primary vulnerability vector, assuming that quantum advances primarily impact cryptanalysis rather than protocol-level or implementation-level attacks. In practice, HNDL risk may also be influenced by:

- Side-channel vulnerabilities: Implementation flaws in current PQC algorithms could accelerate compromise timelines independent of quantum hardware development.

- Key management failures: Inadequate key rotation, weak random number generation, or compromised key storage could enable decryption without quantum capabilities.

- Protocol downgrade attacks: Adversaries forcing use of weaker algorithms (e.g., TLS 1.2 instead of TLS 1.3) could increase harvestable ciphertext vulnerability.

- Hybrid implementation flaws: Incorrect hybrid key exchange implementations might create attack vectors that bypass one protection layer.

These factors could reduce effective values below the theoretical quantum breaking timeline, emphasizing the need for defense-in-depth approaches that combine algorithm migration with implementation security and protocol hardening.

Despite these uncertainties, the qualitative relationship remains robust: delayed post-quantum migration linearly expands exposure regardless of the precise quantum timeline. Future work will incorporate Monte-Carlo sampling of and scenario weighting derived from FS-ISAC and NIST projections to provide explicit confidence bands around sectoral exposure estimates.

4.6. Countermeasures

Mitigation strategies are most effective when they shorten the exposure window, reduce the value of harvested ciphertext, and ensure that long-lived data is protected by cryptography whose security lifetime exceeds the adversary’s decryption horizon. The countermeasures outlined below show how technical, operational, and policy controls can be aligned with these requirements, reinforcing the conclusions drawn from our evaluation.

4.6.1. Assessment of Countermeasures

Mitigating HNDL requires defenses that align confidentiality guarantees with realistic threat horizons. The four complementary approaches listed in Table 3 are emerging.

- (a)

- Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC): National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is standardizing quantum-resilient algorithms to replace RSA ECC [3]. PQC promises durable protection once deployed, but migration at scale is slow, constrained by legacy compatibility and hardware requirements, leaving a vulnerability window during which harvested ciphertext remains exposed [40].

- (b)

- Hybrid key exchange: To bridge this window, hybrid schemes are being trialed in TLS and VPNs [44]. By combining classical and post-quantum primitives in a single handshake, they provide transitional resilience. Yet they secure only future sessions in transit and do not remediate ciphertext already collected.

- (c)

- Forward-secure lifecycles: Another line of defense targets persistence rather than transit. Rotating keys, ephemeral encryption, and controlled data expiration reduce the long-term value of harvested ciphertext [25]. Such measures limit retrospective compromise but are difficult to enforce in regulated contexts where retention is mandatory.

- (d)

- Governance and policy: Technical measures succeed only if adopted in time. Guidance such as the U.S. NSA CNSA 2.0 sets deadlines for migration [22], while ETSI and the ENISA provide sectoral strategies and highlight operational challenges [4,48]. Global PKI, which anchors TLS, VPNs, and code signing, remains a bottleneck where fragmented adoption risks leaving archives vulnerable for decades. At the same time, Grover’s algorithm shows that symmetric cryptography, though more resilient, also demands doubled key sizes to maintain equivalent margins [13]. The broader challenge is therefore twofold: securing asymmetric infrastructures and refreshing symmetric protocols. Without harmonized international policy, adoption will remain fragmented and long-lived data will remain exposed to deferred decryption.

In practice, migration bottlenecks concentrate in global PKI that anchor TLS, VPNs, and code signing. Coordinating trust anchors, certificate profiles, and validation logic across heterogeneous stacks is organizationally harder than deploying new algorithms [3,40]. ENISA highlights planning, inventory, and staged rollouts to avoid fractured deployments across critical services [4,25].

Effective policy therefore couples cryptographic modernization with governance of key lifecycles, inventories of cryptographic dependencies, and procurement levers that enforce algorithm agility. Without such measures, institutional inertia risks extending the HNDL vulnerability window across borders and sectors [3,4].

4.6.2. Complementarity of HNDL Countermeasures

Figure 4 illustrates how PQC establishes long-term resilience, Hybrid Key Exchange provides transitional protection, Forward-Secure Lifecycles reduce archival exposure, and QKD enhances security at the physical layer. Governance ensures coordinated deployment across these complementary measures. The effectiveness indicators depict the relative strength of each countermeasure, while the implementation timeline highlights the importance of synchronized adoption to close the HNDL vulnerability window. These defenses are mutually reinforcing: PQC anchors enduring resilience, hybrid approaches safeguard the migration phase, and forward-secure mechanisms constrain retrospective risk, all under a governance framework that sustains consistent and verifiable transition across communication systems.

Figure 4.

Complementarity of HNDL countermeasures showing layered defenses with governance as the coordinating framework. Solid arrows denote direct mitigation of HNDL, while dashed arrows indicate complementary coordination and dependency relationships between defenses.

Each defense addresses a distinct dimension of the temporal threat, with governance providing the coordinating framework. Solid arrows denote direct mitigation, while dashed links highlight complementary relationships. Effectiveness indicators and the implementation timeline emphasize the need for synchronized deployment.

4.7. Discussion

No single countermeasure can neutralize HNDL. PQC offers durable protection but migration delays preserve a window of exposure [17]. Hybrids provide transitional security yet do not remediate harvested ciphertext. Forward-secure lifecycles reduce archival risk but remain difficult to enforce under regulatory and operational constraints. QKD contributes physical-layer guarantees, but its high cost and limited scalability restrict adoption. These defenses are therefore complementary: PQC secures the future, hybrids bridge the transition, and forward-secure designs mitigate legacy risk, with governance determining how consistently these measures are deployed [28,33].

The systemic implication is that HNDL is not only a cryptographic problem but a challenge of infrastructure coordination and policy. Residual gaps persist in protecting decades-old archives, overcoming global PKI inertia, and achieving algorithm agility across heterogeneous systems. Addressing these requires research into scalable key management and migration frameworks, cryptographically agile PKI ecosystems, secure archival and expiration practices, and international governance mechanisms that synchronize adoption timelines. Framing confidentiality as a temporal property shifts the agenda: safeguarding information demands decades-long commitments that span technical, organizational, and geopolitical domains.

5. Future Work

The communications community faces several research priorities to address HNDL threats. First, integrating HNDL-aware risk metrics into protocol design could guide algorithm agility in TLS, VPNs, and 5G/6G infrastructures. Second, lightweight mechanisms for secure expiration and cryptographic re-keying are needed to manage IoT-scale deployments where data lifetimes are short but retention is mandated. Third, embedding HNDL considerations into standards bodies and regulatory frameworks would ensure that confidentiality horizons are not overlooked during global migration. By linking cryptographic advances with network design and governance, the community can move from recognizing HNDL as a theoretical risk to operationalizing defenses at scale.

Additional research directions include developing quantitative risk models with uncertainty quantification for quantum capability development, creating game-based security definitions for HNDL-resistance, investigating side-channel attacks and implementation vulnerabilities that could accelerate HNDL timelines, and conducting empirical validation through surveys and case studies of real migration efforts.

6. Conclusions

Harvest-now, decrypt-later reframes confidentiality as a temporal vulnerability rather than a static property. This work formalizes the HNDL adversarial model, mapped sectoral exposure through confidentiality lifetimes, and synthesized countermeasures spanning PQC, hybrid exchange, forward-secure lifecycles, and governance.

Residual risks remain in protecting long-lived archives, overcoming PKI inertia, and coordinating international migration. Addressing these requires coupling technical advances with scalable key management, algorithm agility, and governance frameworks that ensure confidentiality lifetimes remain credible against advancing adversaries.

For communications infrastructures, this reframing establishes confidentiality not as a one-time cryptographic choice but as a horizon-dependent commitment. By treating HNDL as a systemic challenge, the field can accelerate quantum-resilient adoption and design protocols that embed multi-decade confidentiality into the foundations of future networks.

Author Contributions

F.K. and P.B. conceived the research and developed the theoretical framework. F.K. performed the mathematical modeling and analysis. J.B. contributed to the quantum cryptography aspects and security analysis. R.A. provided expertise in quantum physics and post-quantum transitions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the SmartSat Cooperative Research Center (CRC), funded by the Australian Government’s CRC Program.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the SmartSat CRC for their support and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shor, P.W. Algorithms for Quantum Computation: Discrete Logarithms and Factoring. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS ’94), Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20–22 November 1994; pp. 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, P.W. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM Rev. 1999, 41, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustin, M.; Ray, P.; Andrew, R.; Angela, R.; David, C. Transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography Standards; NIST Internal Report (IR) NIST IR 8547 ipd.h; National Institute of Technology and Standards: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beullens, W.; D’Anvers, J.P.; Hülsing, A.T.; Lange, T.; Panny, L.; de Saint Guilhem, C.; Smart, N.P. Post-Quantum Cryptography: Current State and Quantum Mitigation; ENISA: Heraklion, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A. Interview with Andersen Cheng. 2023. Available online: https://cybermagazine.com/interviews/andersen-cheng (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Durr-E-Shahwar; Imran, M.; Altamimi, A.B.; Khan, W.; Hussain, S.; Alsaffar, M. Quantum Cryptography for Future Networks Security: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 180048–180078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehic, M.; Michalek, L.; Dervisevic, E.; Burdiak, P.; Plakalovic, M.; Rozhon, J.; Mahovac, N.; Richter, F.; Kaljic, E.; Lauterbach, F.; et al. Quantum Cryptography in 5G Networks: A Comprehensive Overview. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 26, 302–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, O.; Omotayo, A.; Grace, A.; Abubakar, M. Future-Proofing Data: Assessing the Feasibility of Post-Quantum Cryptographic Algorithms to Mitigate ‘Harvest Now, Decrypt Later’ Attacks. Asian J. Comput. Inf. Syst. (ACRI) 2025, 25, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, I.; Kim, J.; Pawana, I.W.A.J.; Ko, Y. Mitigating security vulnerabilities in 6g networks: A comprehensive analysis of the dmrn protocol using svo logic and proverif. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, B.; Antonio, S.; Luis Enrique, S. QISS: Quantum-enhanced sustainable security incident handling in the IoT. Information 2024, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagai, F.; Branch, P.; But, J.; Allen, R.; Rice, M. Performance evaluation of low-bitrate voice using spread spectrum techniques for satellite-based emergency communication. Comput. Netw. 2025, 270, 111560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidney, C.; Ekerå, M.; Fowler, A.G. How to Factor 2048-bit RSA with Less Than One Million Noisy Qubits. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.15917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, L.K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on the Theory of Computing (STOC ’96), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 22–24 May 1996; pp. 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK National Cyber Security Centre. Preparing for Post-Quantum Cryptography. Official UK Guidance on Quantum-Safe Readiness. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/whitepaper/preparing-for-post-quantum-cryptography (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- NIST; NCCoE. NIST SP 1800-38C: Migration to Post-Quantum Cryptography (Preliminary Draft). Preliminary Draft. 2023. Available online: https://www.nccoe.nist.gov/sites/default/files/2023-12/pqc-migration-nist-sp-1800-38c-preliminary-draft.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- CISA; NSA; NIST. Quantum Readiness: Migration to Post-Quantum Cryptography; Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/resources-tools/resources/quantum-readiness-migration-post-quantum-cryptography (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Bhatt, S.; Bhushan, B.; Srivastava, T.; Anoop, V. Post-quantum cryptographic schemes for security enhancement in 5G and B5G (beyond 5G) cellular networks. In 5G and Beyond; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 247–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbeau, M.; Garcia-Alfaro, J. Cyber-physical defense in the quantum Era. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cyber Security Centre. Timelines for Migration to Post-Quantum Cryptography; National Cyber Security Centre: Cheltenham, UK, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/guidance/pqc-migration-timelines (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Alagic, G.; Bros, M.; Ciadoux, P.; Cooper, D.; Dang, Q.; Dang, T.; Kelsey, J.; Lichtinger, J.; Liu, Y.K.; Miller, C.; et al. Status Report on the Fourth Round of the Nist Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization Process. 2025. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2025/NIST.IR.8545.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Moody, D. NIST PQC: The Road Ahead; NIST presentation, 2025; Cryptographic Technology Group, National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/csrc/media/Presentations/2025/nist-pqc-the-road-ahead/images-media/rwcpqc-march2025-moody.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- National Security Agency. Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 (CNSA 2.0); U.S. NSA: Fort Meade, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://media.defense.gov/2025/May/30/2003728741/-1/-1/0/CSA_CNSA_2.0_ALGORITHMS.PDF (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Spagnolo, M.; Ndou, V.; Giribaldi, D.; Arena, V. A Framework for Dealing with Cybersecurity Risks as Part of Information Security. In Digitalization, Sustainable Development, and Industry 5.0: An Organizational Model for Twin Transitions; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, M.; Chen, L.; Mosca, M.; Ribordy, G.; Schanck, J.M. Quantum-Safe Cryptography and Security: An Introduction, Benefits, and Impact (Revision 4); Technical Report ETSI White Paper No. 8 (Rev. 4); European Telecommunications Standards Institute: Sophia Antipolis CEDEX, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.etsi.org/images/files/ETSIWhitePapers/QuantumSafeWhitepaper.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Bernstein, D.J.; Hülsing, A.T.; Lange, T. Post-Quantum Cryptography-Integration Study; ENISA: Heraklion, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bellare, M.; Rogaway, P. Entity Authentication and Key Distribution. In Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO ’93, Proceedings of the 13th Annual International Cryptology Conference (CRYPTO ’93), Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 22–26 August 1993; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; Volume 773, pp. 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigaliūnas, Š.; Brūzgienė, R. Towards a Unified Quantum Risk Assessment. Electronics 2025, 14, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankalp, M.R.; Lokapal, G.; Mohan, B.A.; Basavaraj, G.N. Addressing Cybersecurity Challenges in 6G Networks Through AI-Driven Adaptive Defense Mechanisms and Quantum-Resilient Protocols. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Computing for Sustainability and Intelligent Future (COMP-SIF), Bangalore, India, 21–22 March 2025; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervisevic, E.; Tankovic, A.; Fazel, E.; Kompella, R.; Fazio, P.; Voznak, M.; Mehic, M. Quantum Key Distribution Networks-Key Management: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagai, F.; Branch, P.; But, J.; Allen, R.; Rice, M. Rapidly Deployable Satellite-Based Emergency Communications Infrastructure. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 139368–139410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monz, T.; Nigg, D.; Martinez, E.A.; Brandl, M.F.; Schindler, P.; Rines, R.; Wang, S.X.; Chuang, I.L.; Blatt, R. Realization of a scalable Shor algorithm. Science 2016, 351, 1068–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regev, O. An Efficient Quantum Factoring Algorithm. ACM Digit. Libr. 2025, 72, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagai, F. ICT Infrastructure for Campus Big Data: Network, Storage and Security Design and Implementation; Staffordshire University: Stoke-on-Trent, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedunoori, V. A Comprehensive Review of Encryption and Protection Techniques for Healthcare Data. In Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare Information Systems—Security and Privacy Challenges; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Malina, L.; Dzurenda, P.; Ricci, S.; Hajny, J.; Srivastava, G.; Matulevičius, R.; Affia, A.A.O.; Laurent, M.; Sultan, N.H.; Tang, Q. Post-Quantum Era Privacy Protection for Intelligent Infrastructures. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 36038–36077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhouse, W.; Souppaya, M.; Barker, W.; Brown, C.; Kampanakis, P.; Manzano, M.; McGrew, D.; Dames, A.; Soukharev, V.; Lafrance, P.; et al. Migration to Post-Quantum Cryptography Quantum Readiness: Cryptographic Discovery; NIST Special Report; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1800; p. 38B. Available online: https://www.nccoe.nist.gov/sites/default/files/2023-12/pqc-migration-nist-sp-1800-38b-preliminary-draft.pdf?trk=public_post_comment-text (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Van Deventer, O.; Spethmann, N.; Loeffler, M.; Amoretti, M.; Van Den Brink, R.; Bruno, N.; Comi, P.; Farrugia, N.; Gramegna, M.; Jenet, A.; et al. Towards European standards for quantum technologies. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2022, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss, M.A. Presidential Cold War Doctrines: What Are They Good for? Dipl. Hist. 2023, 48, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascelli, J.; Rodden, M. “Harvest Now Decrypt Later”: Examining Post-Quantum Cryptography and the Data Privacy Risks for Distributed Ledger Networks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Government. Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography; Technical Report; The White House: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/REF_PQC-Report_FINAL_Send.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Russinovich, M.; Braverman-Blumenstyk, M. Quantum-Safe Security: Progress Towards Next-Generation Cryptography. Blog Post, Microsoft Security Blog. 2025. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2025/08/20/quantum-safe-security-progress-towards-next-generation-cryptography/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Fernick, J.; Foster, A. Announcing Quantum-Safe Digital Signatures in Cloud KMS. Blog Post, Google Cloud Blog. 2025. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/identity-security/announcing-quantum-safe-digital-signatures-in-cloud-kms (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Campagna, M.; Goldsborough, M.; O’Donnell, P. AWS Post-Quantum Cryptography Migration Plan. Blog Post, AWS Security Blog. 2025. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/security/aws-post-quantum-cryptography-migration-plan/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Canto, A.C.; Kaur, J.; Kermani, M.M.; Azarderakhsh, R. Algorithmic Security is Insufficient: A Comprehensive Survey on Implementation Attacks Haunting Post-Quantum Security. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI, G.Q. Exponential suppression of bit or phase errors with cyclic error correction. Nature 2021, 595, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Phalak, K.; Ghosh, S. Quantum Error Correction For Dummies. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE), Bellevue, WA, USA, 17–22 September 2023; Volume 1, pp. 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oko-Odion, C.; Angela, O. Risk management frameworks for financial institutions in a rapidly changing economic landscape. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2025, 14, 1182–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dina, G.; Andrew, M.; Katherine, B.; Laura, H.; Matthew, H. Cryptographic Standards for a Post-Quantum World. IEEE Spectr. 2024, 61, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).