Assessing the Impact of DoS Attacks on the Performance of Asterisk-Based VoIP Platforms

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Greater confidentiality of information. The information transmitted in them does not go outside the organization’s network and it is not processed by other operators as far as the calls of internal subscribers are concerned.

- Very good flexibility and equipment options. Not every subscriber needs to have a physical IP phone. They can simply install software phones on the computers that employees work on. Through the internal wireless network (Wi-Fi) and the corresponding application, the employees’ mobile phones can be used as terminals for communication in the private telephone exchange, and so even the subscriber can be mobile within the range of the wireless network.

- Ability to maintain control. The system administrator has full access to the employee conversations. It can be found out who they talked to, for how long, at what time, and more, without requiring special permission from judicial authorities or other institutions.

2. Related Work

3. Research Methodology, Topology of the Experimental Network, Used Tools

3.1. Research Methodology

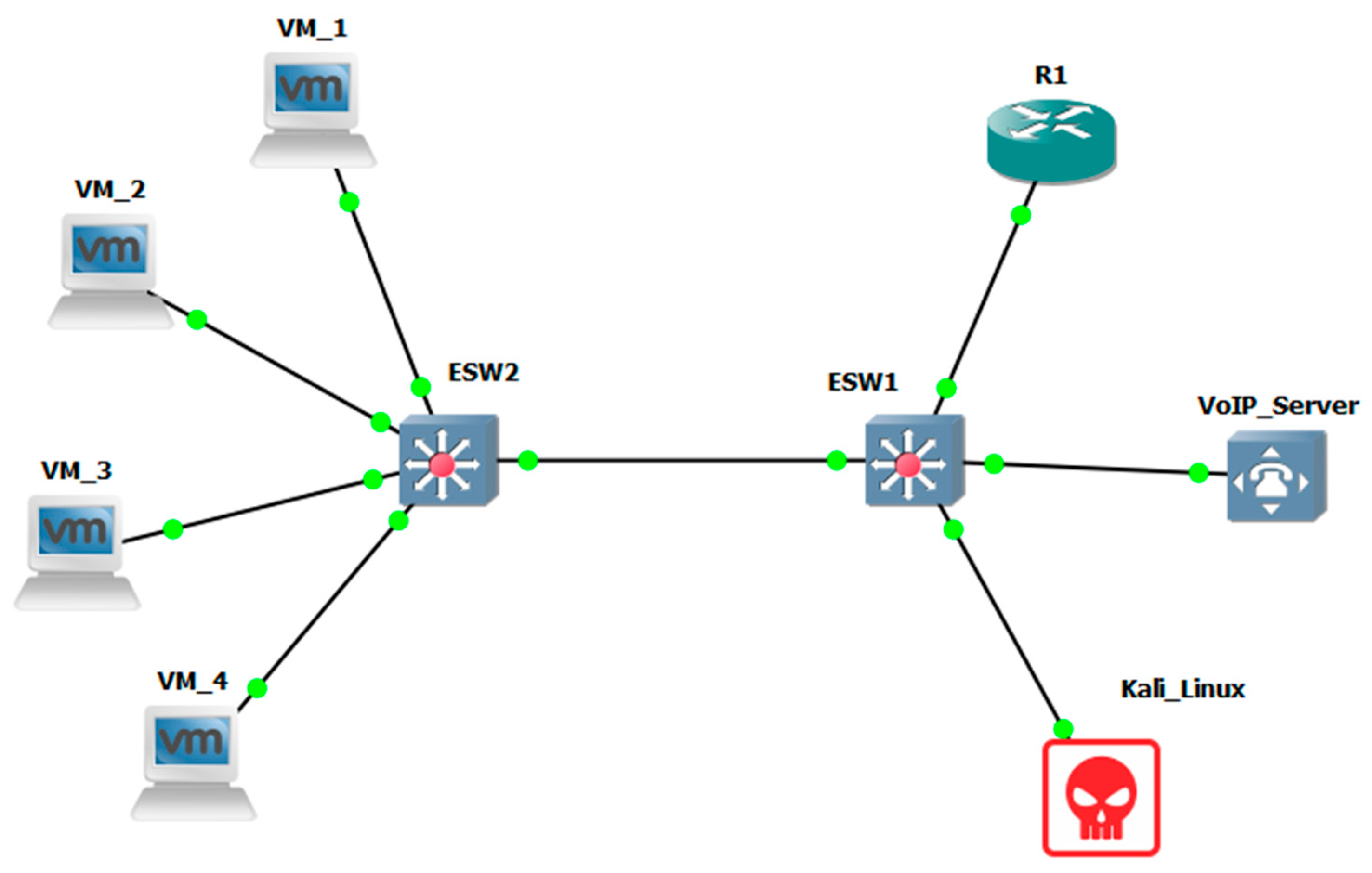

3.2. Topology of the Experimental Network

3.3. Used Tools

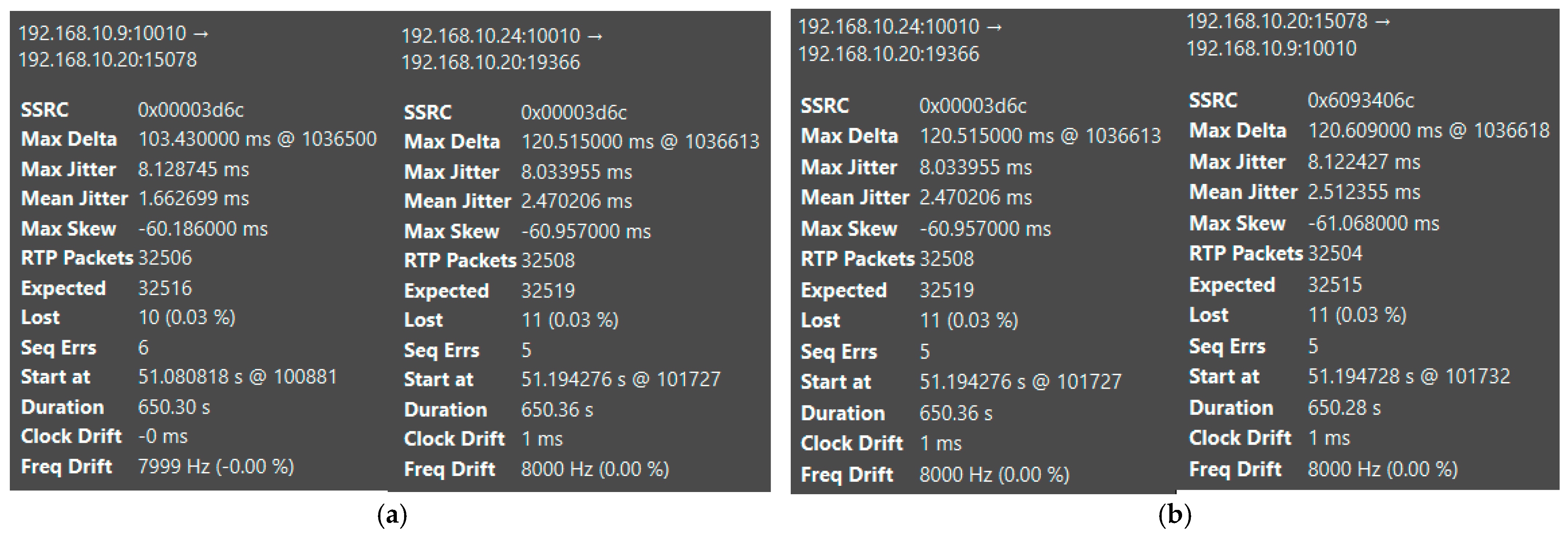

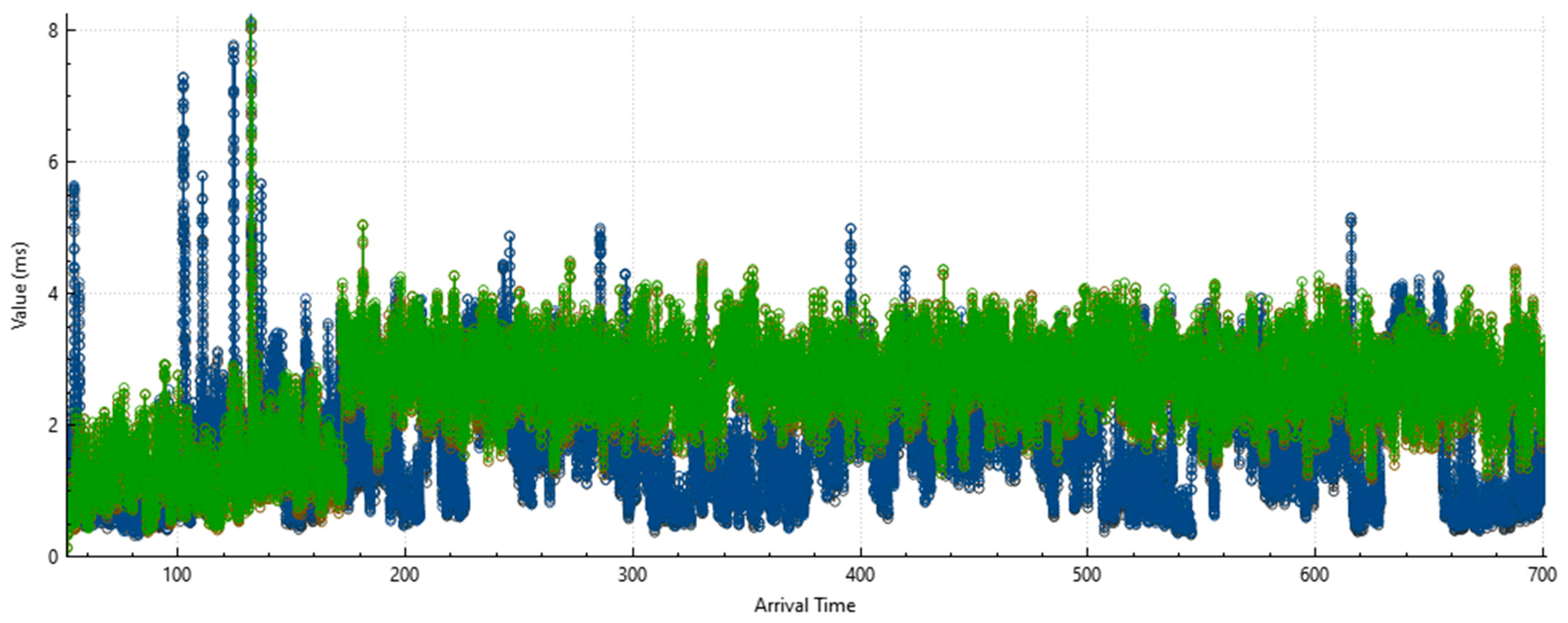

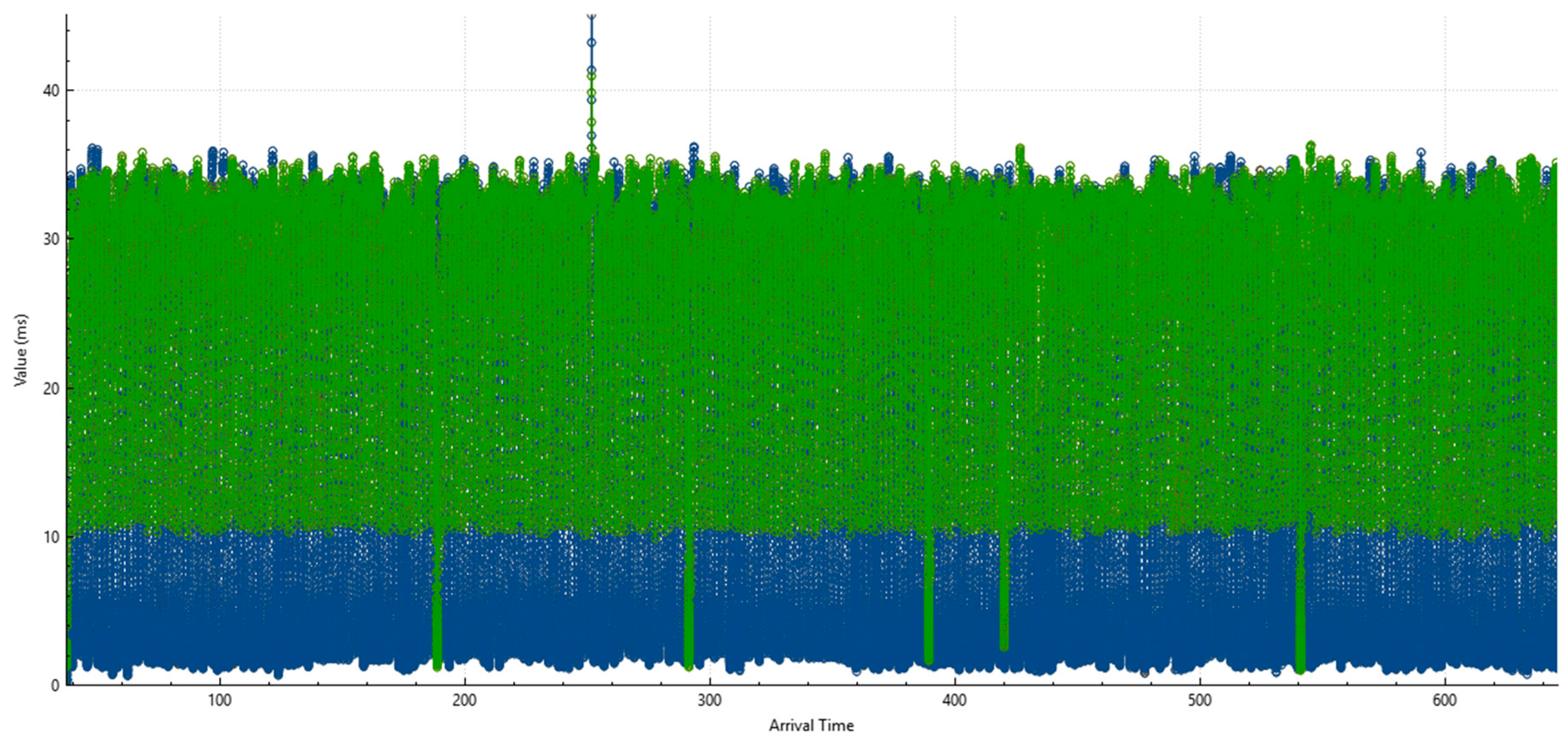

- Network protocol analyzer—Wireshark ver. 4.6.0 was used for this study. It was used to capture all packets exchanged between the VoIP server under study and its subscribers. Its main advantage that led to the use of this tool is the built-in VoIP flow analysis capabilities [38];

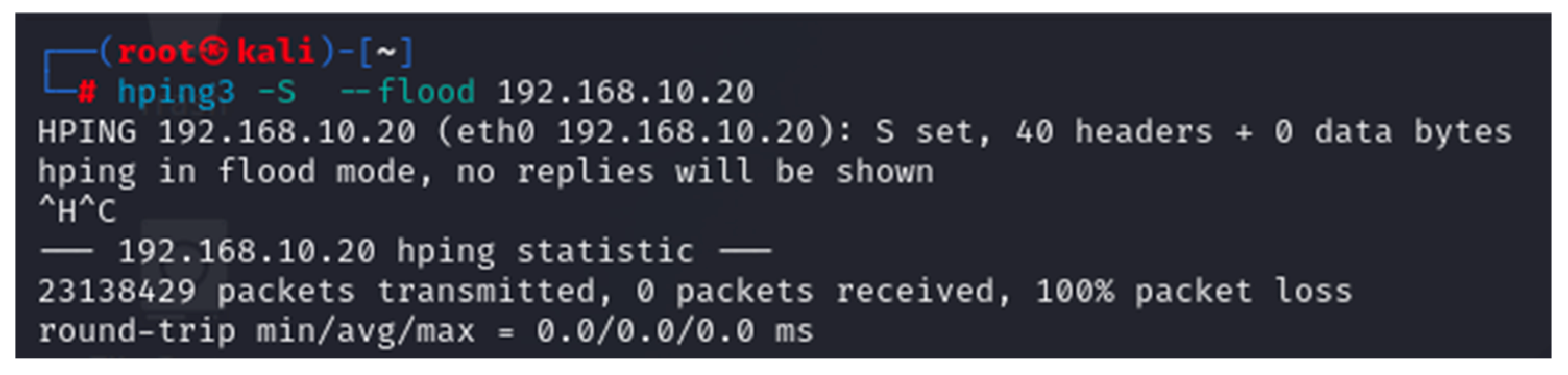

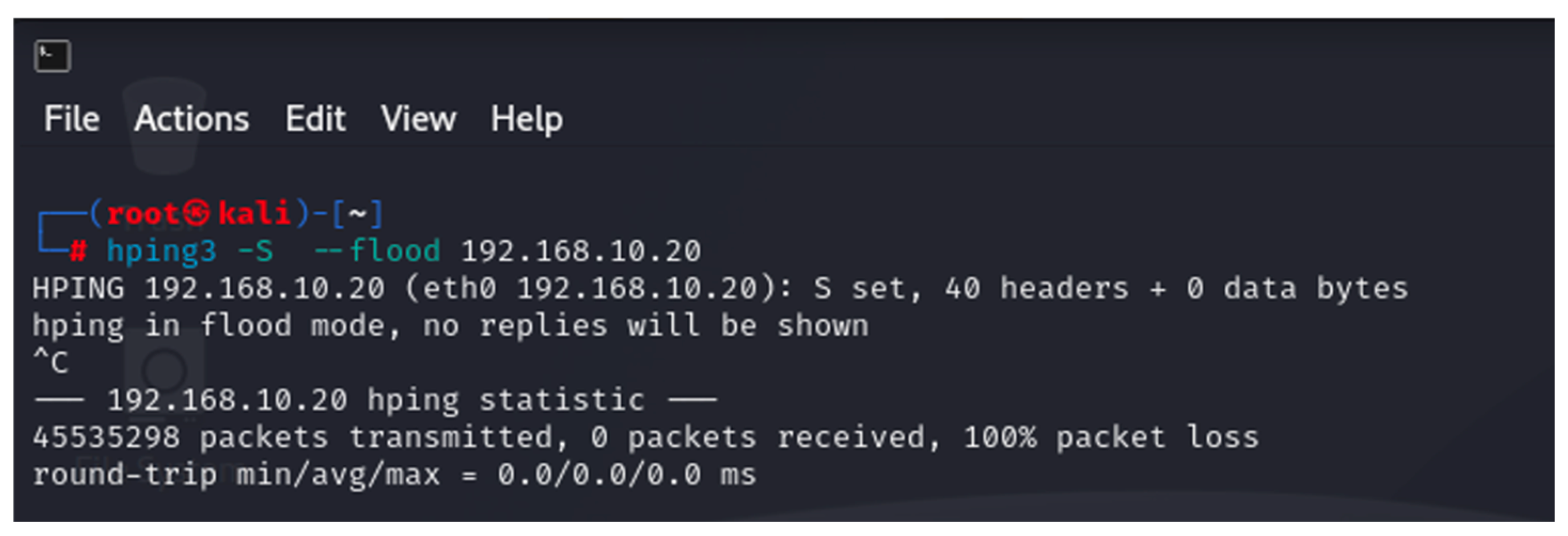

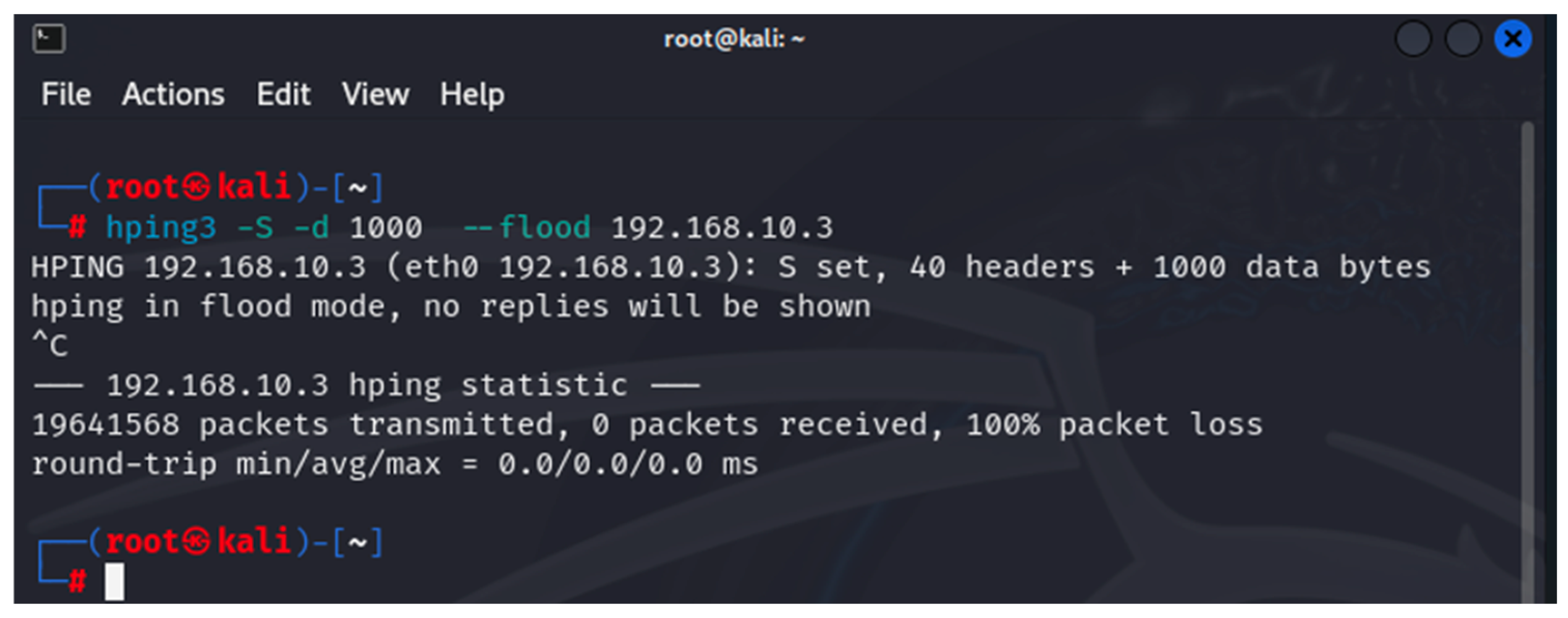

- hping3 ver. 3.0.0—this is a tool built into Kali Linux that is used to generate custom TCP/UDP packets designed to build various TCP/UDP DoS attacks. In this study, hping3 was used to implement TCP and UDP DoS attacks [39];

- Nmap ver. 7.94—this tool is also a part of the Kali Linux tools. It is used to scan ports on network devices. Nmap sends specially crafted packets to the host and then analyzes the responses. In this study, only the analysis of functionality of Nmap was used, based on specialized scripts, to analyze a network device for various network vulnerabilities [40];

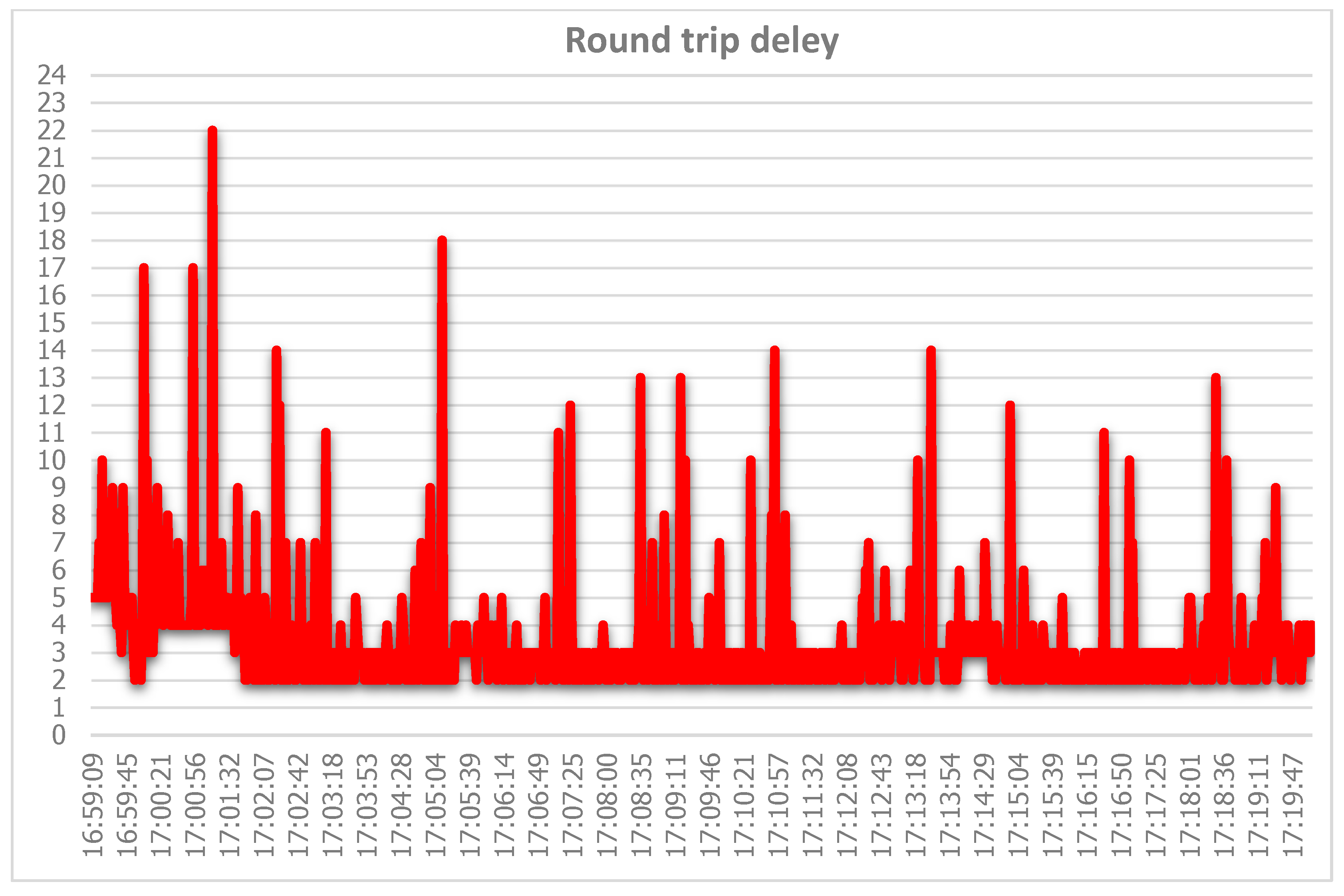

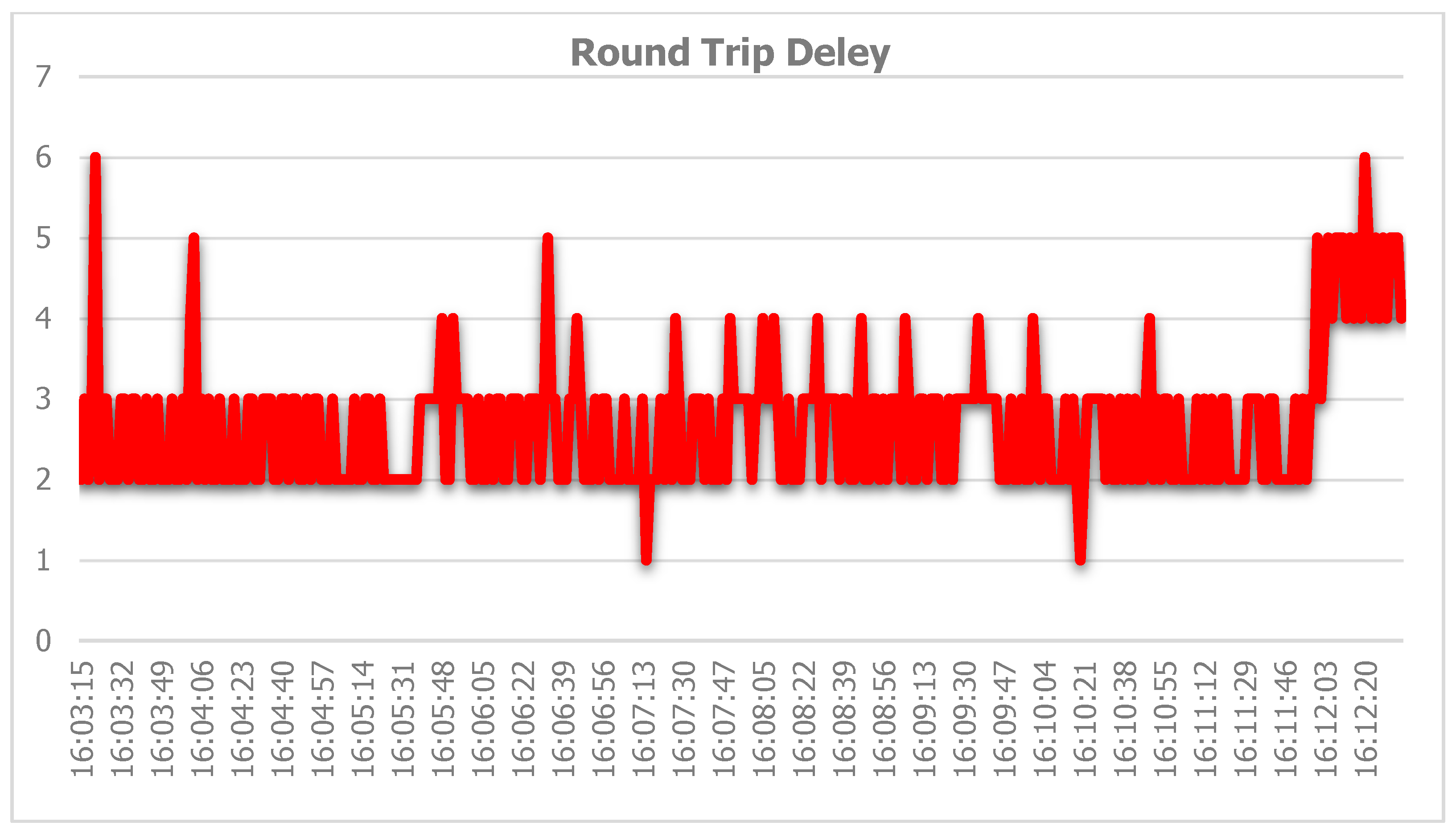

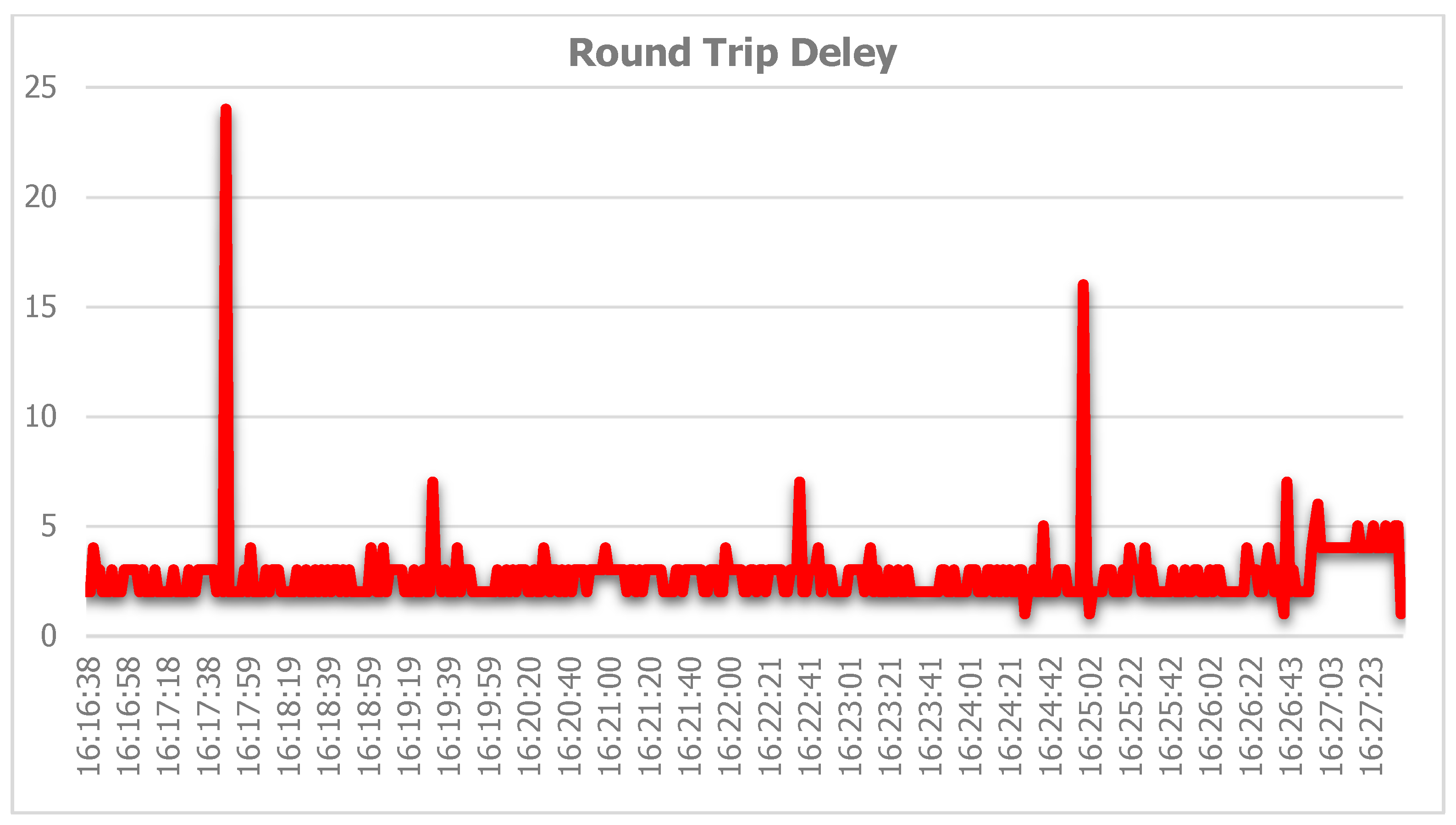

- Colasoft Ping Tool ver. 2.0—this tool was used to check what is the round-trip delay between the subscriber and the studied VoIP server during the DoS attacks—if there is packet loss, what the delay is and more [41];

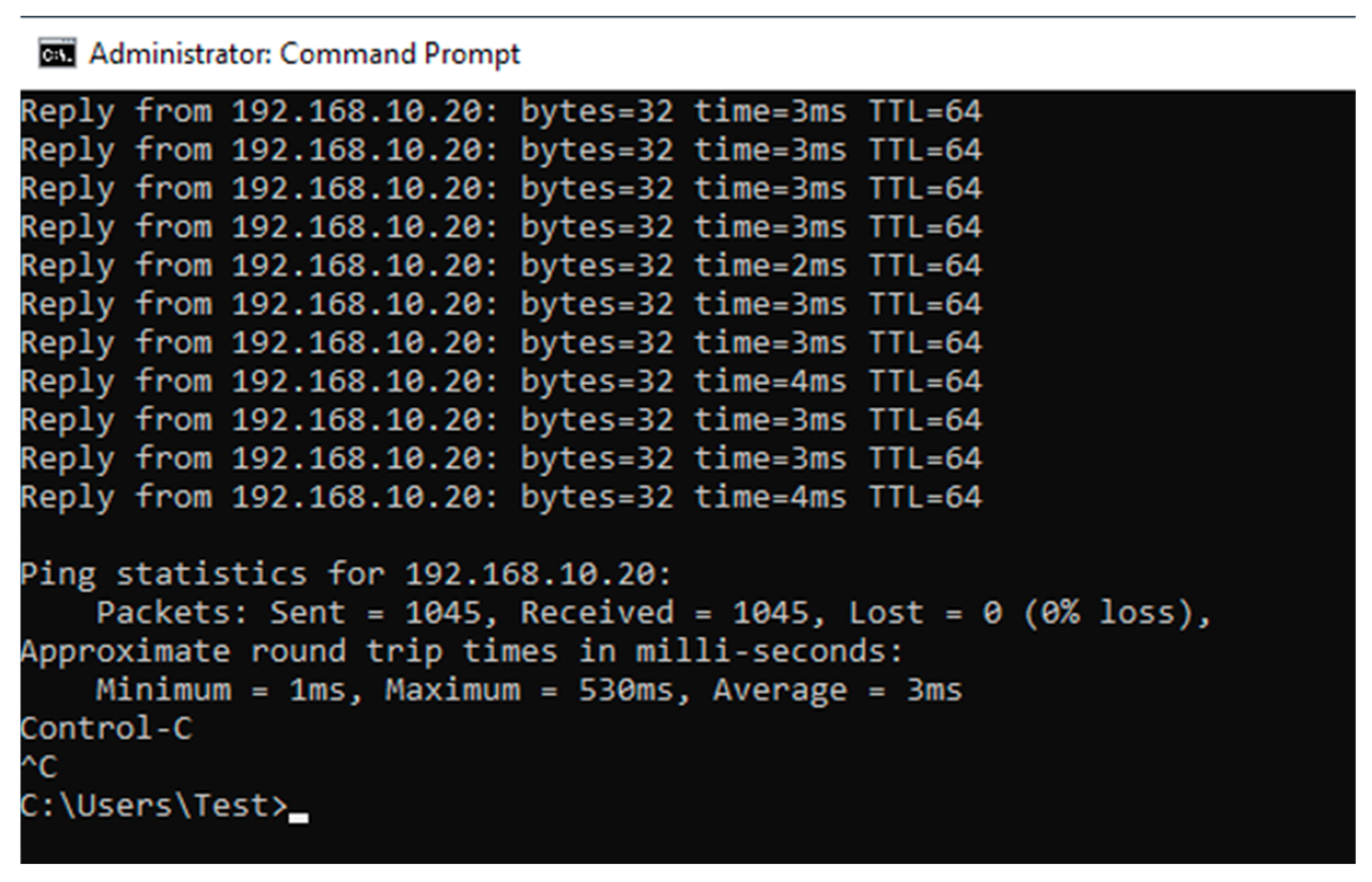

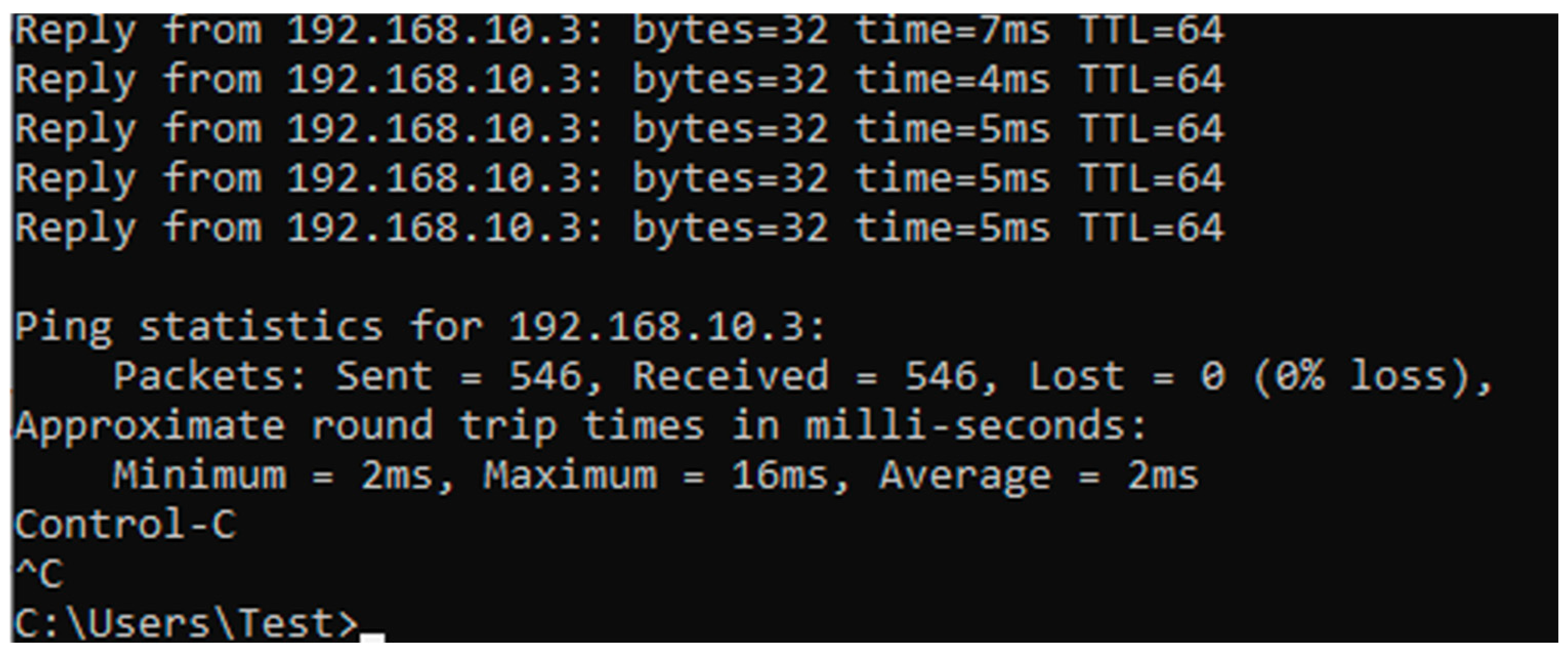

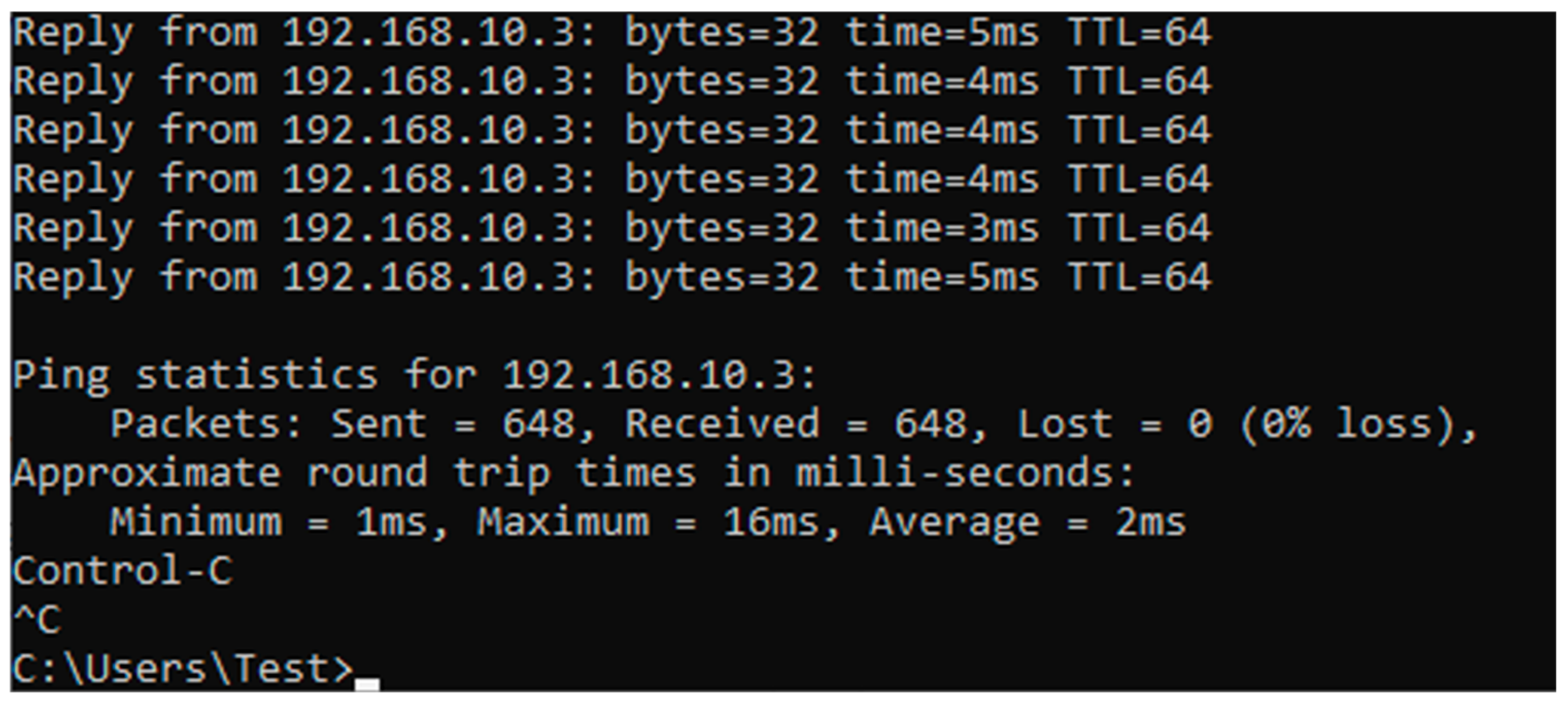

- Windows CMD—the ping command will be used, to find out the packet loss and the average delay in ms.

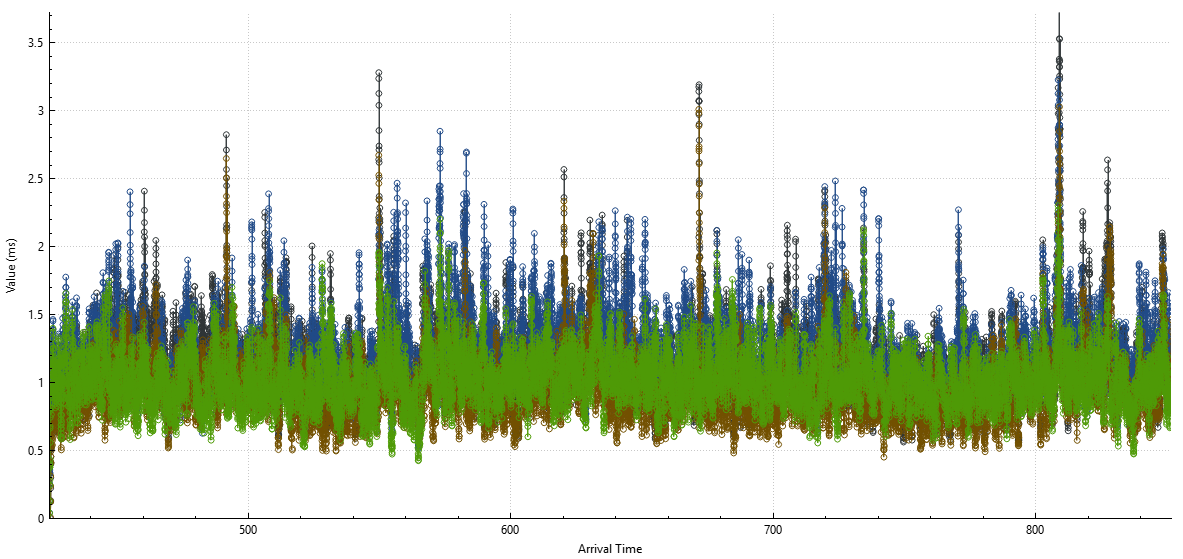

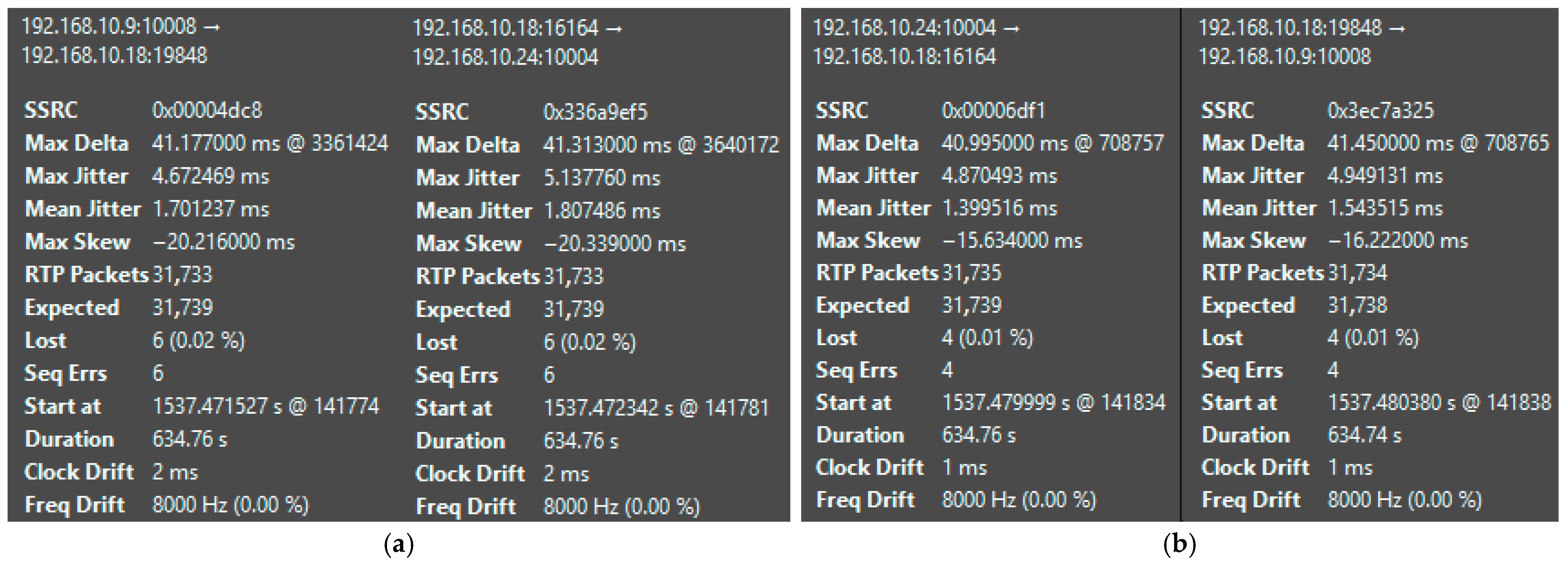

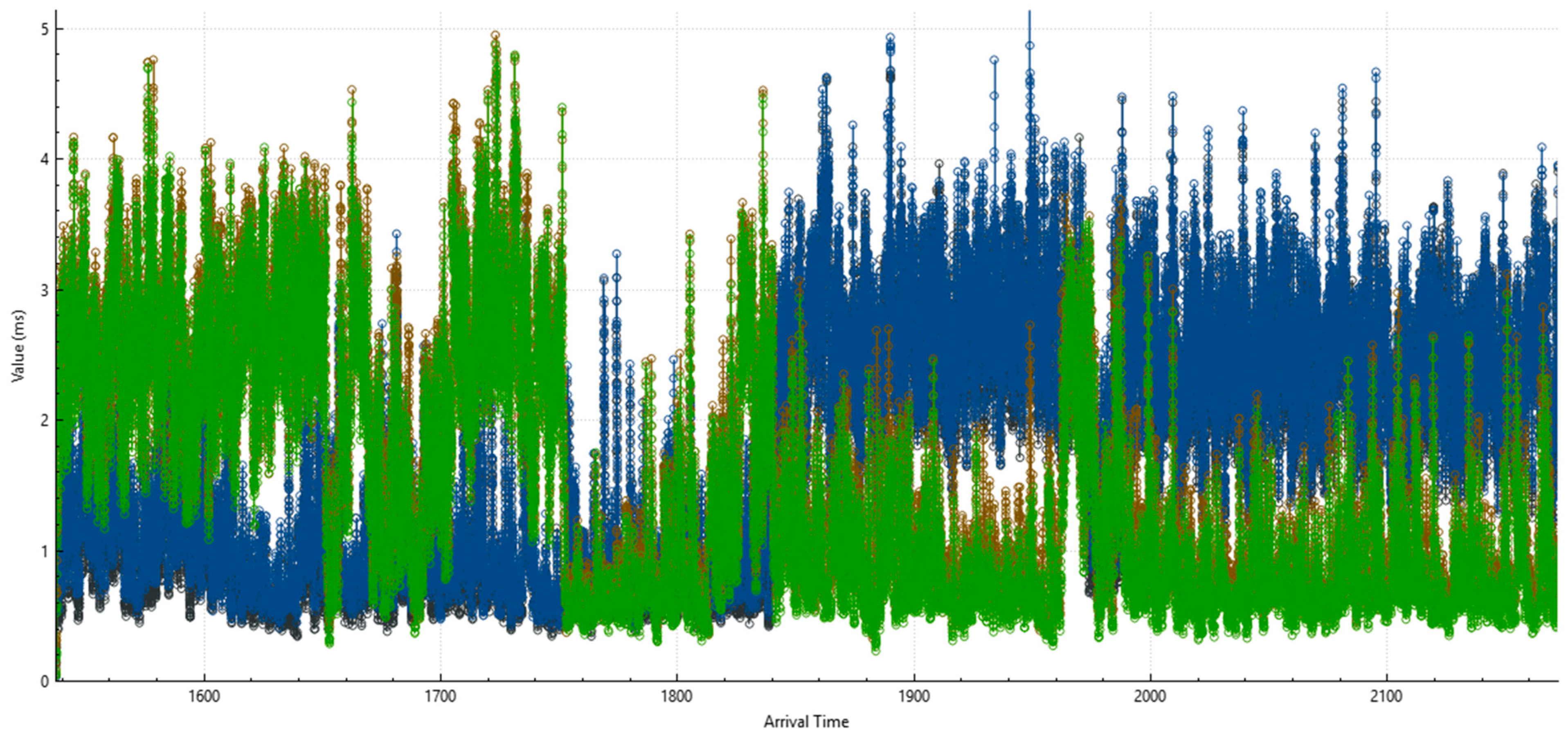

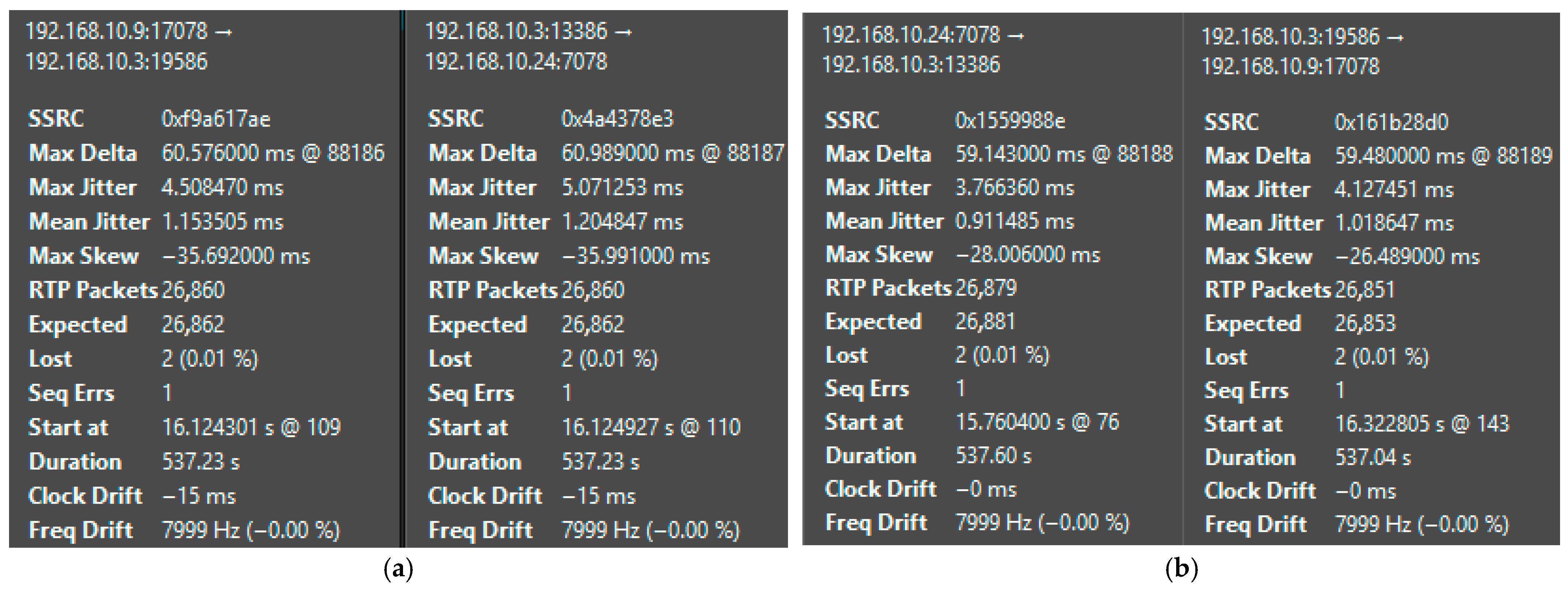

4. Results

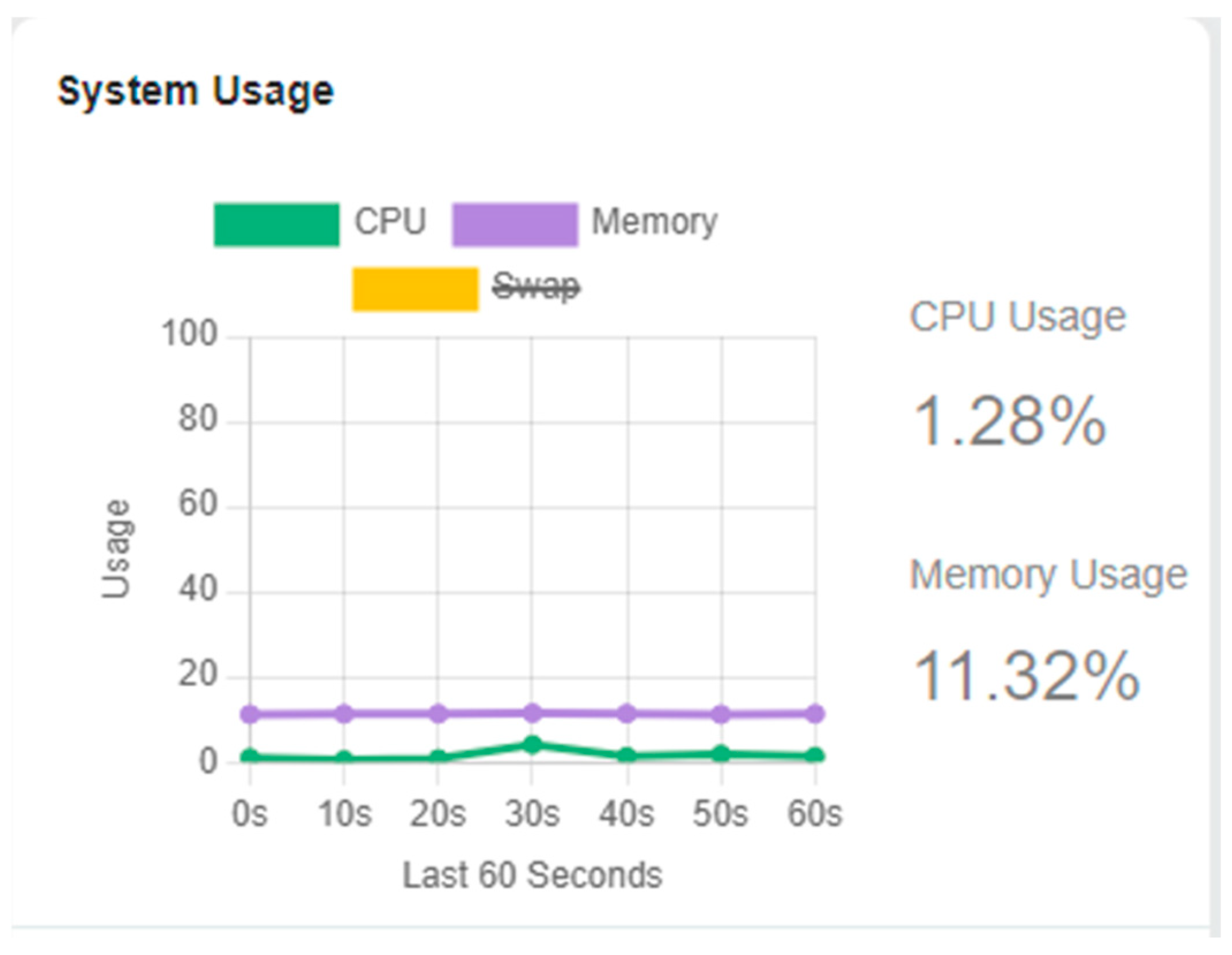

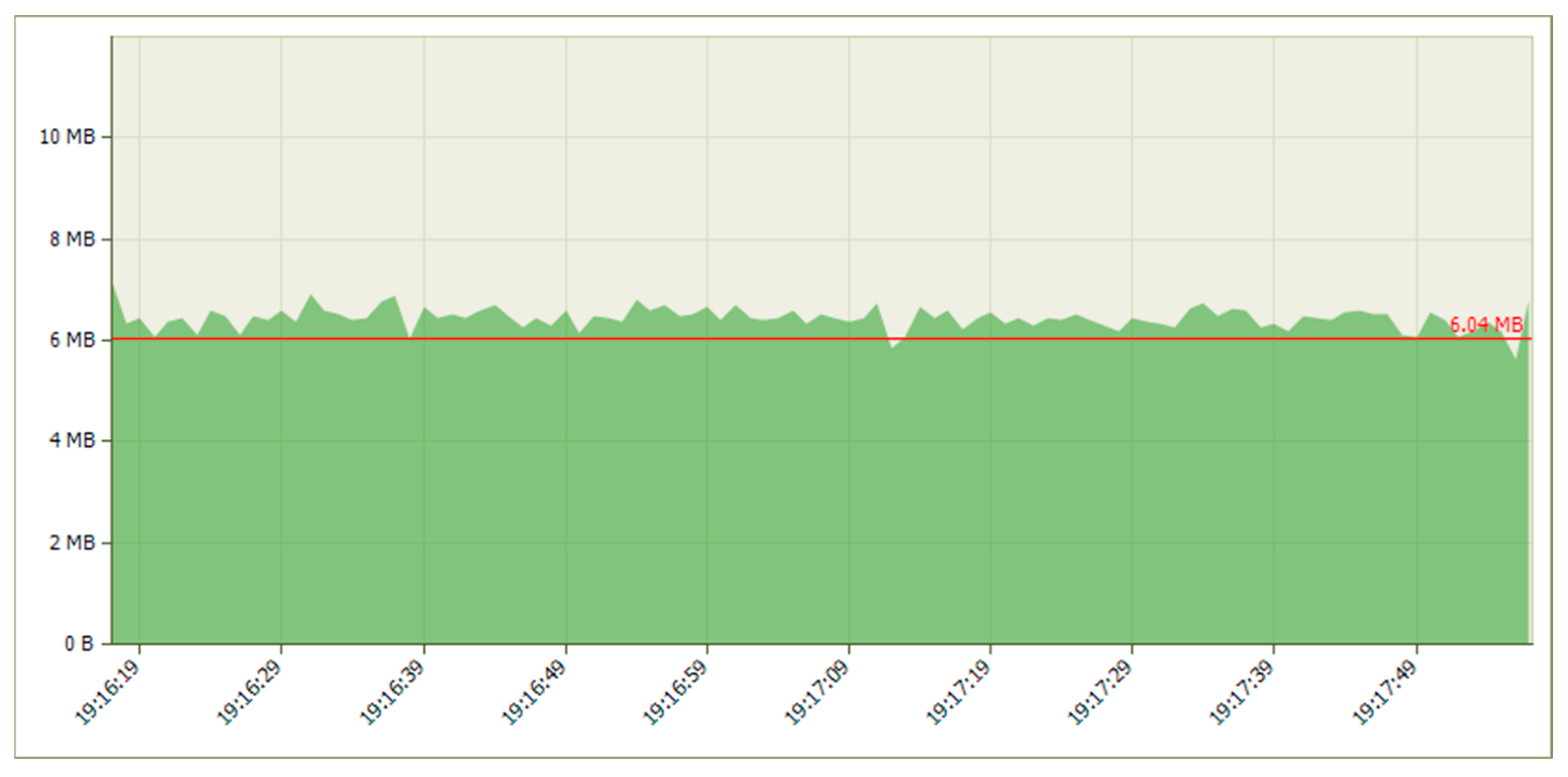

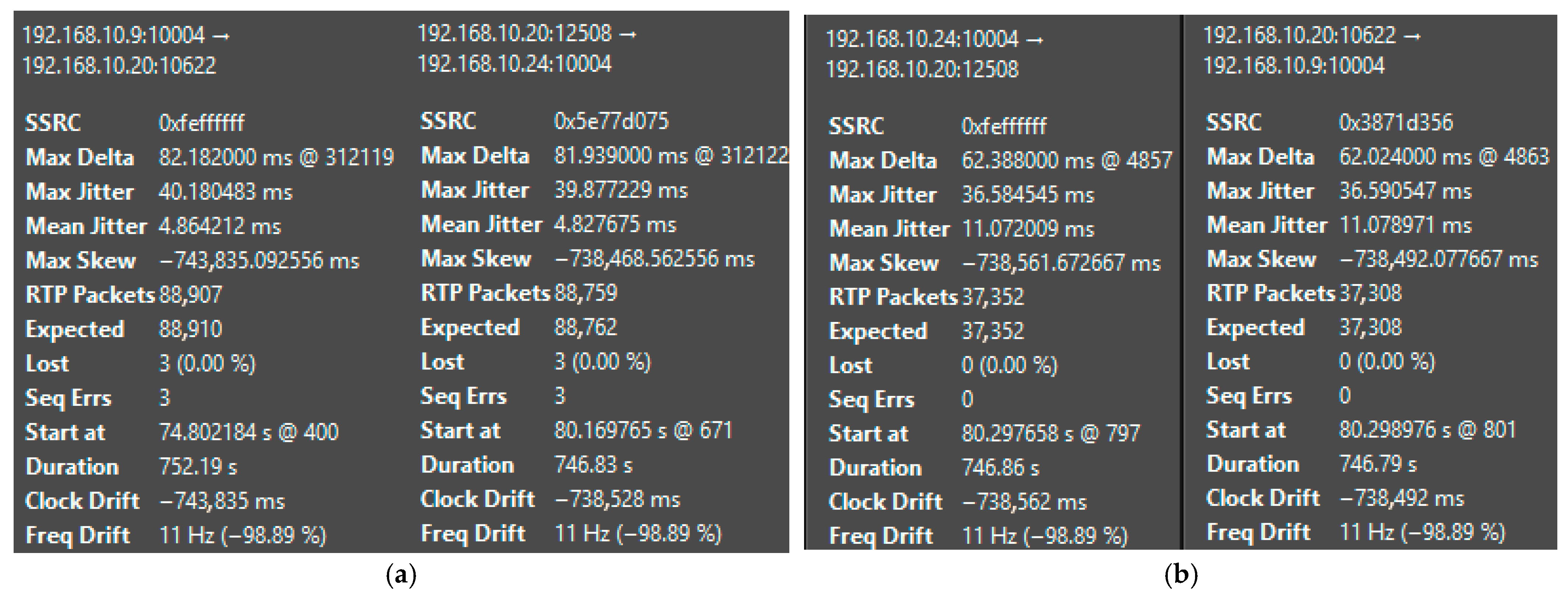

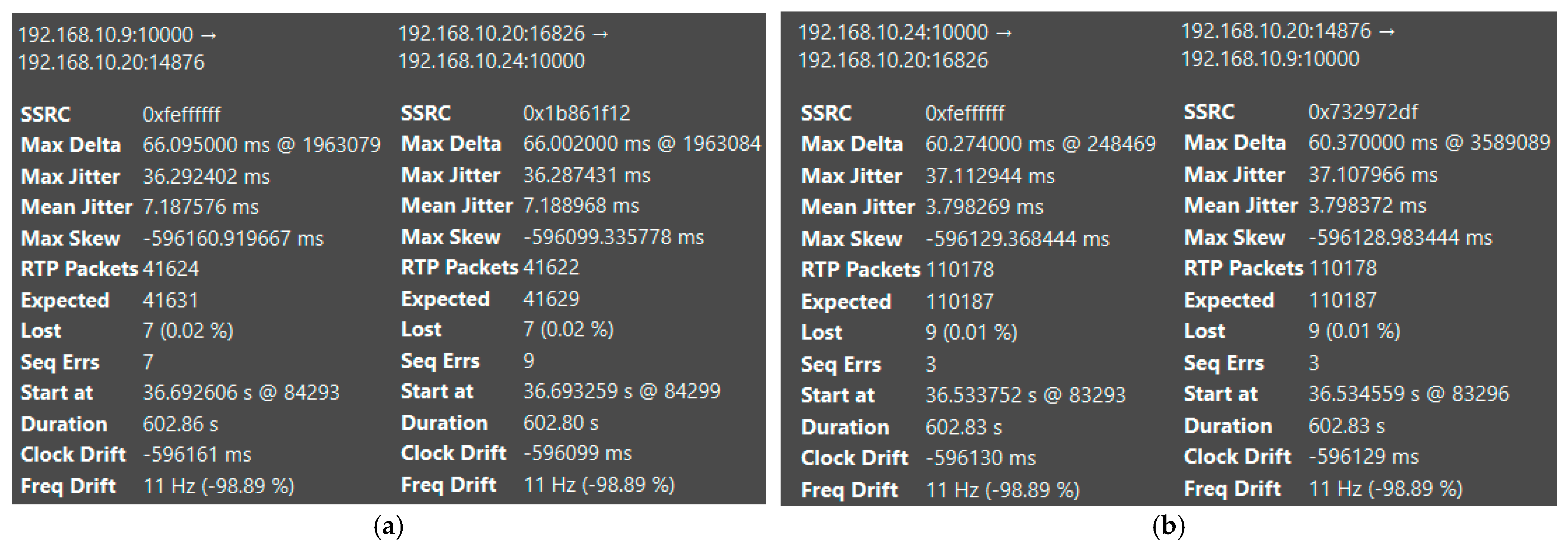

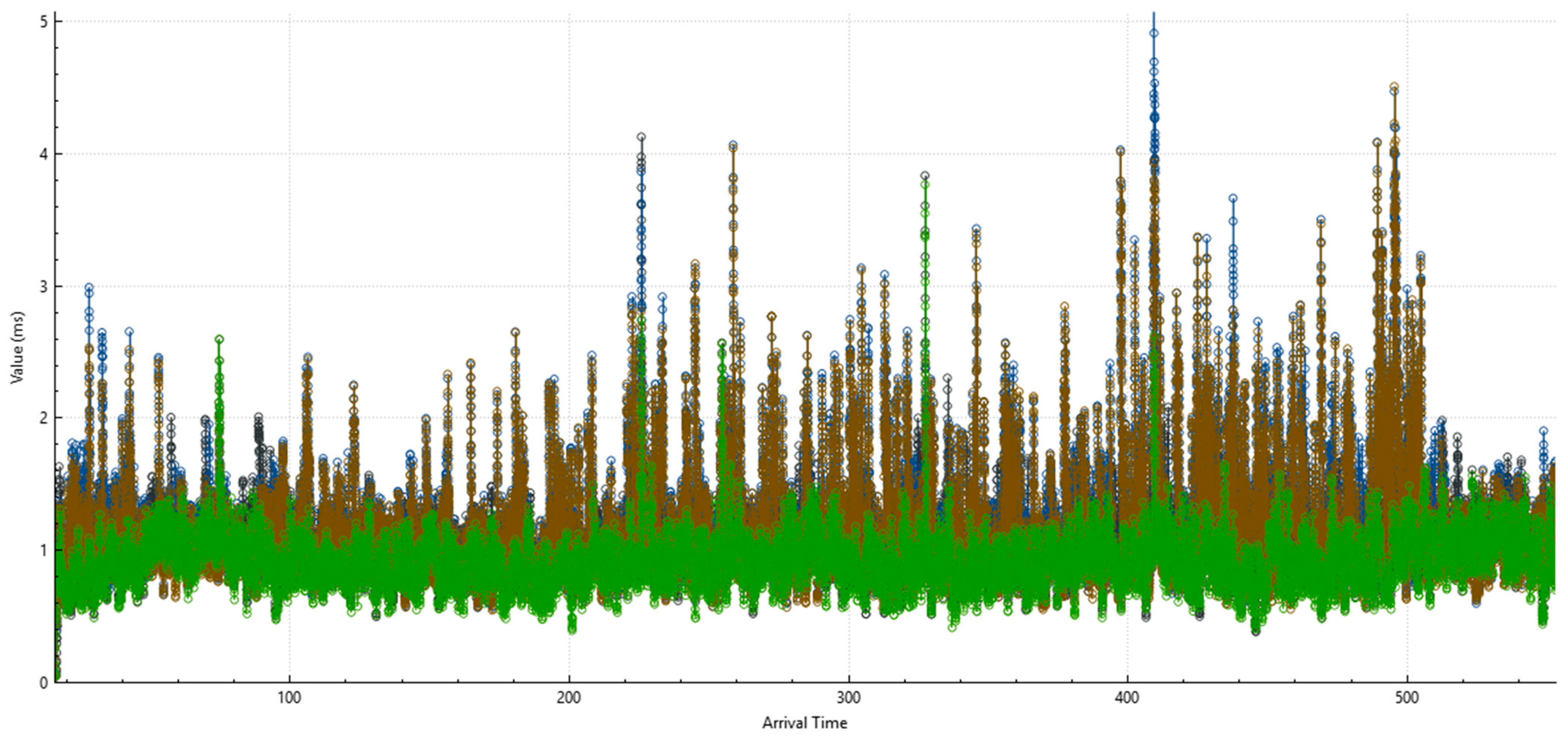

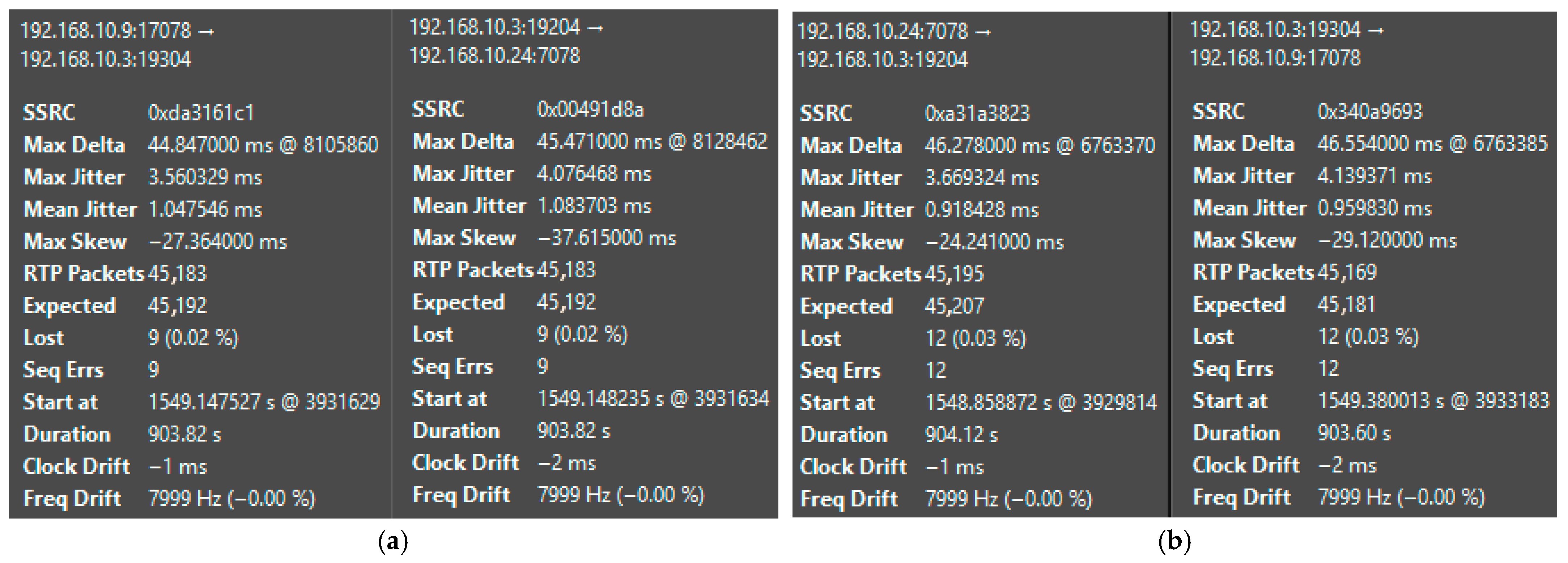

4.1. Results for the VitalPBX

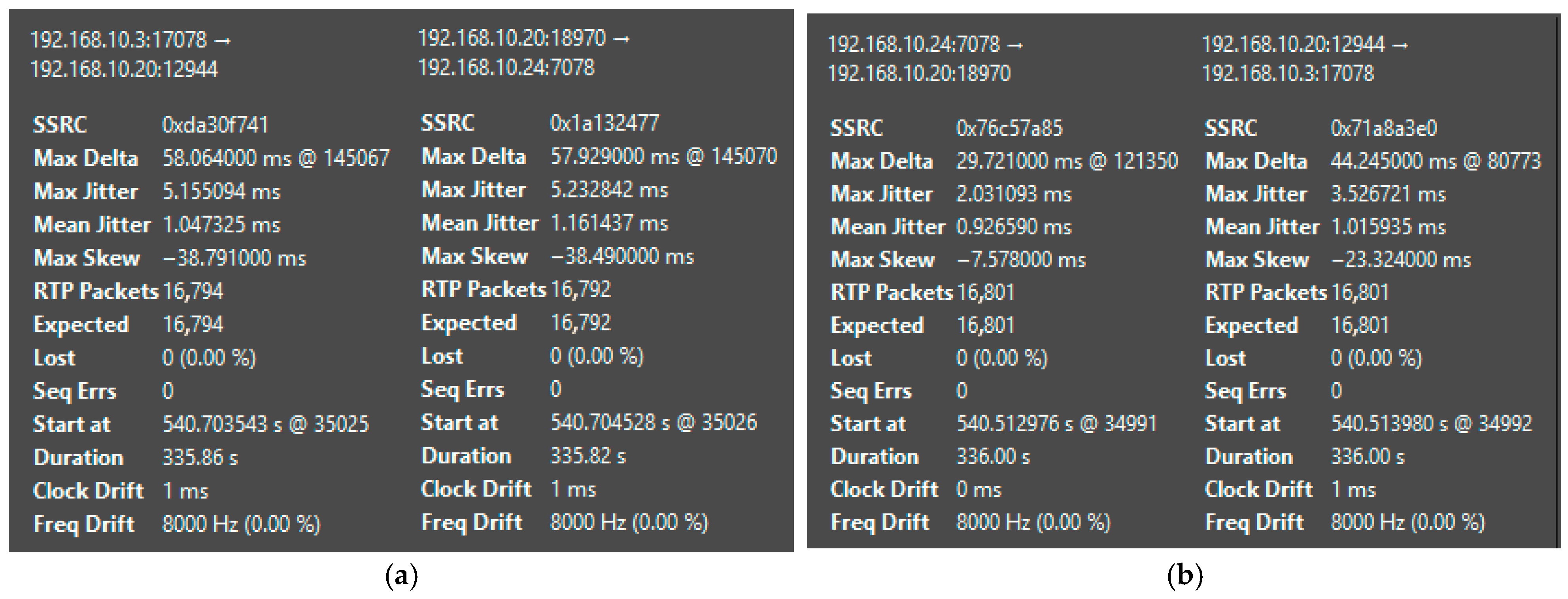

4.1.1. Only Audio Calls and TCP Flooding

4.1.2. Only Audio Calls and UDP Flooding

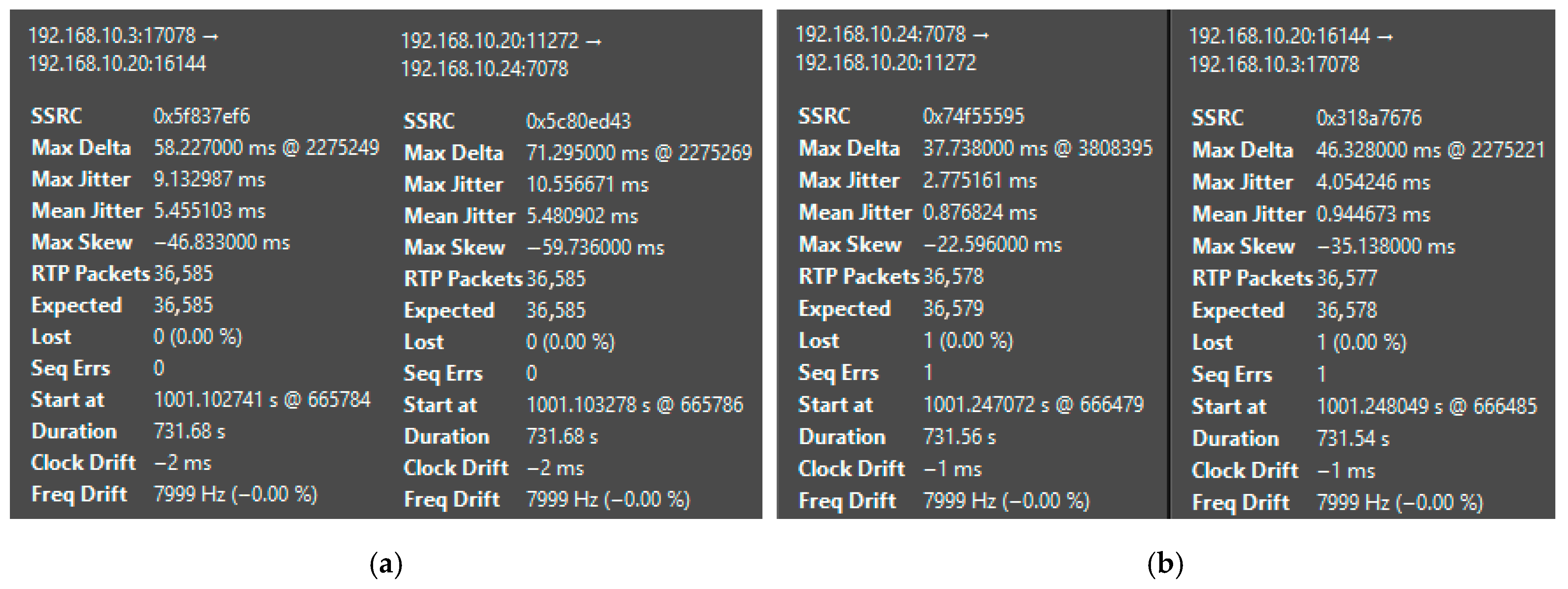

4.1.3. Only Video Calls and TCP SYN Attack

4.1.4. Only Video Calls and UDP Flooding Attack

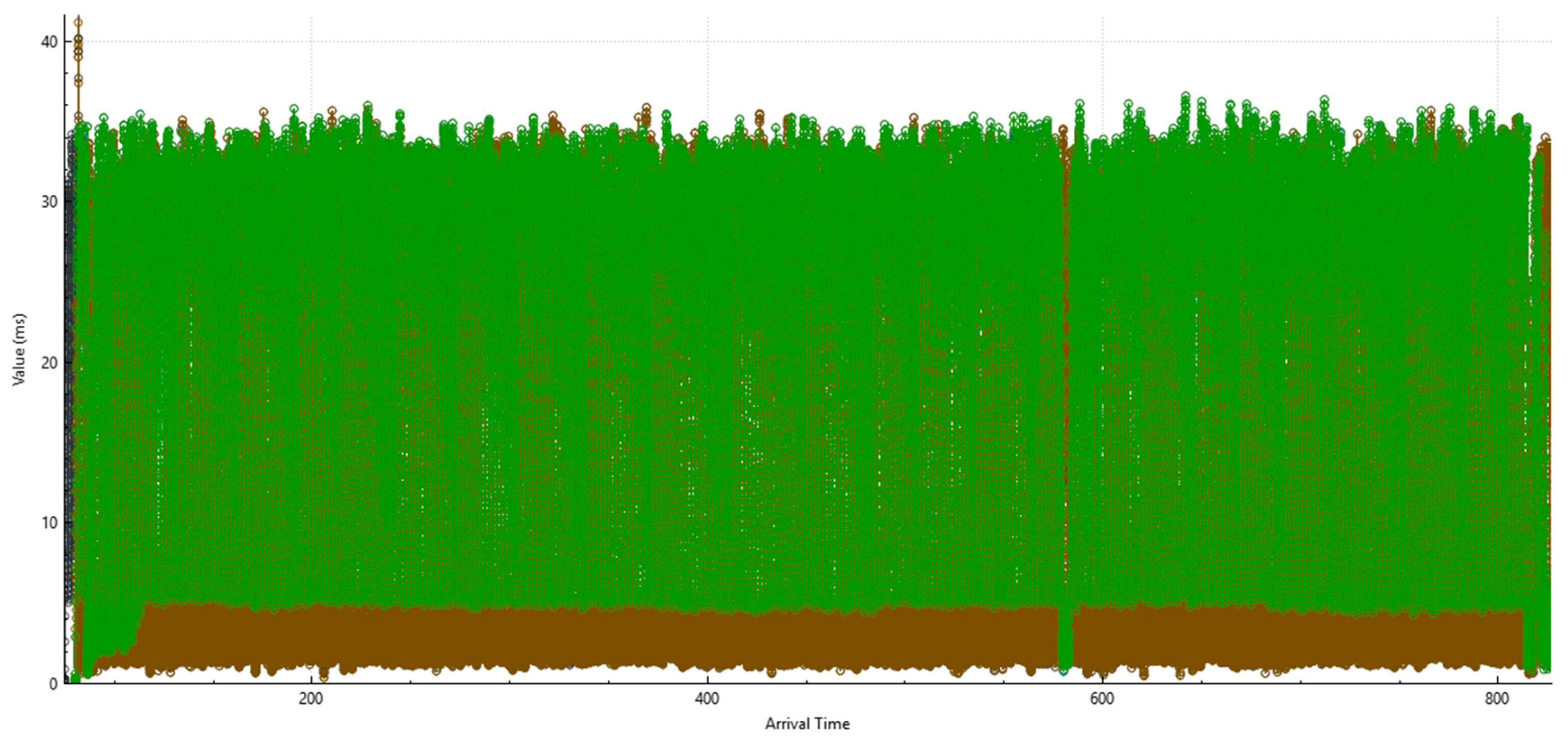

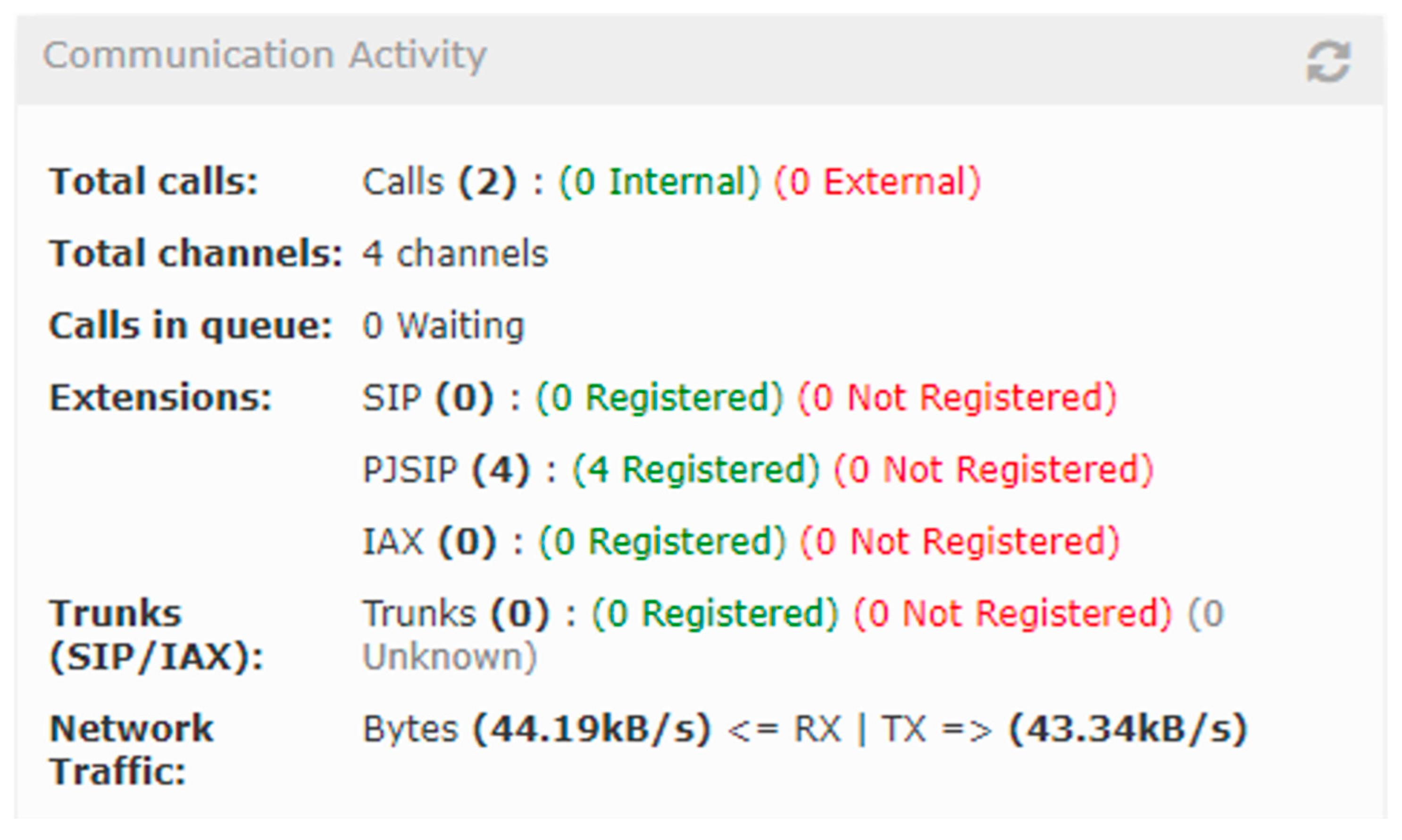

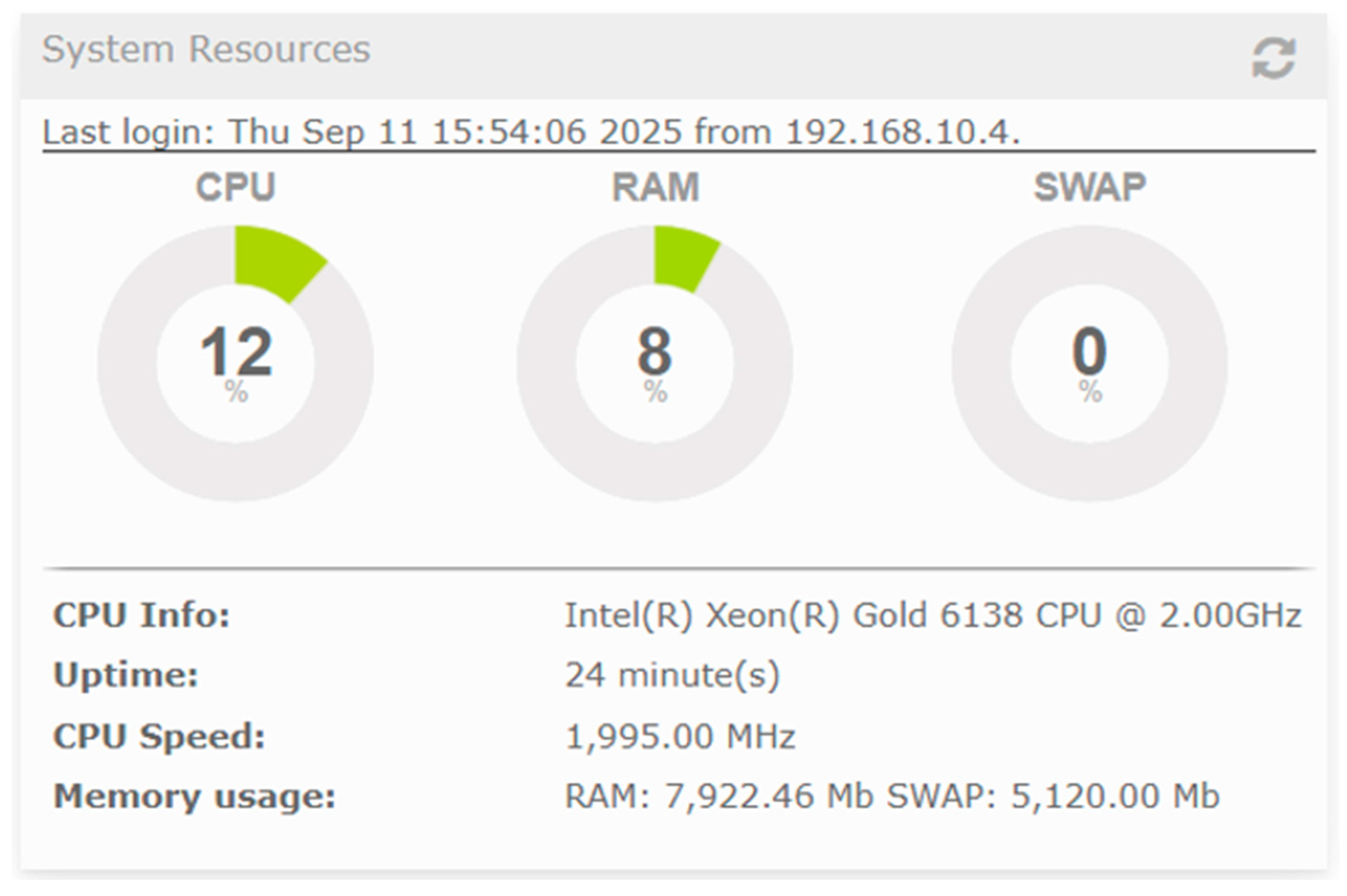

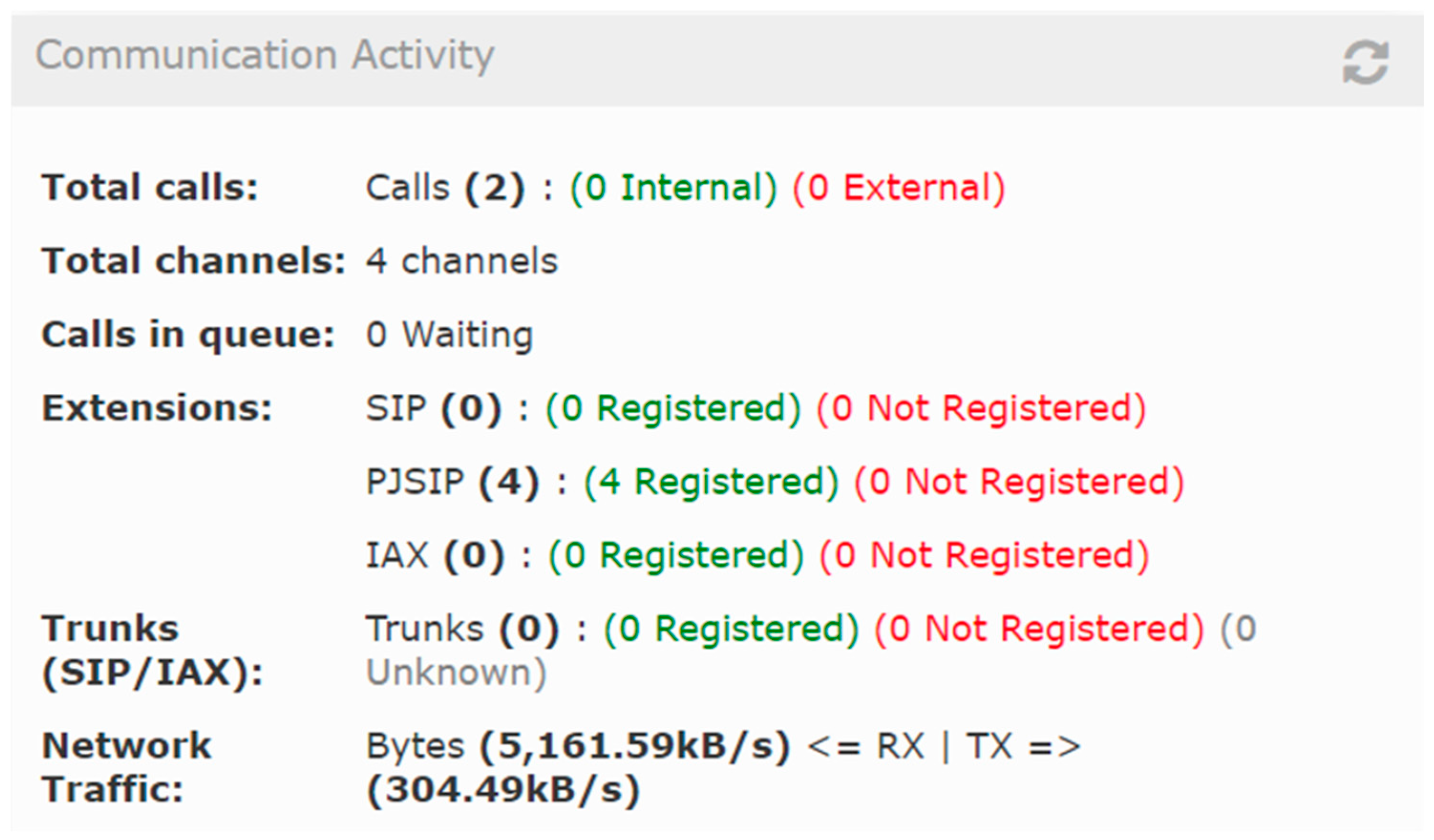

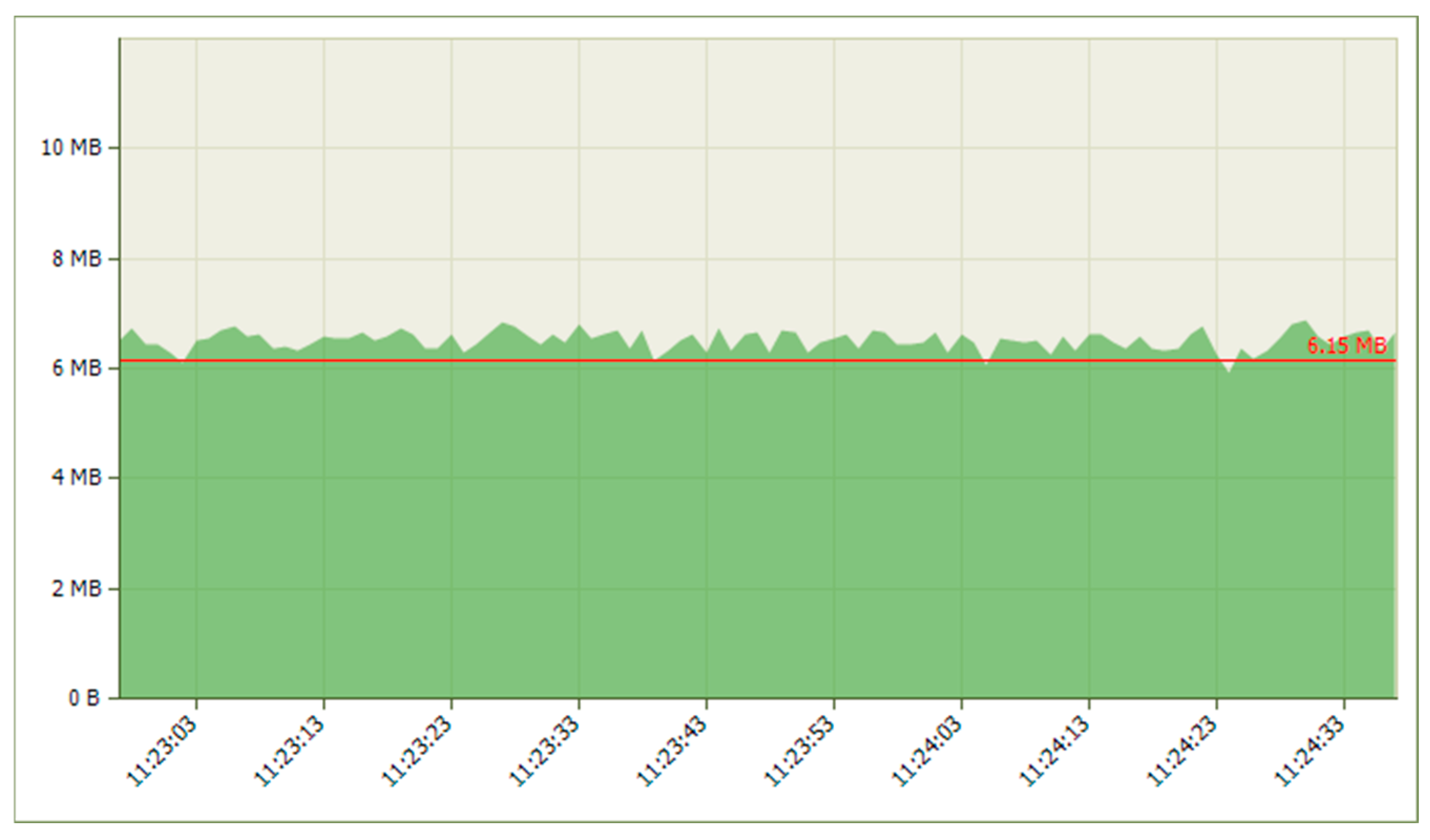

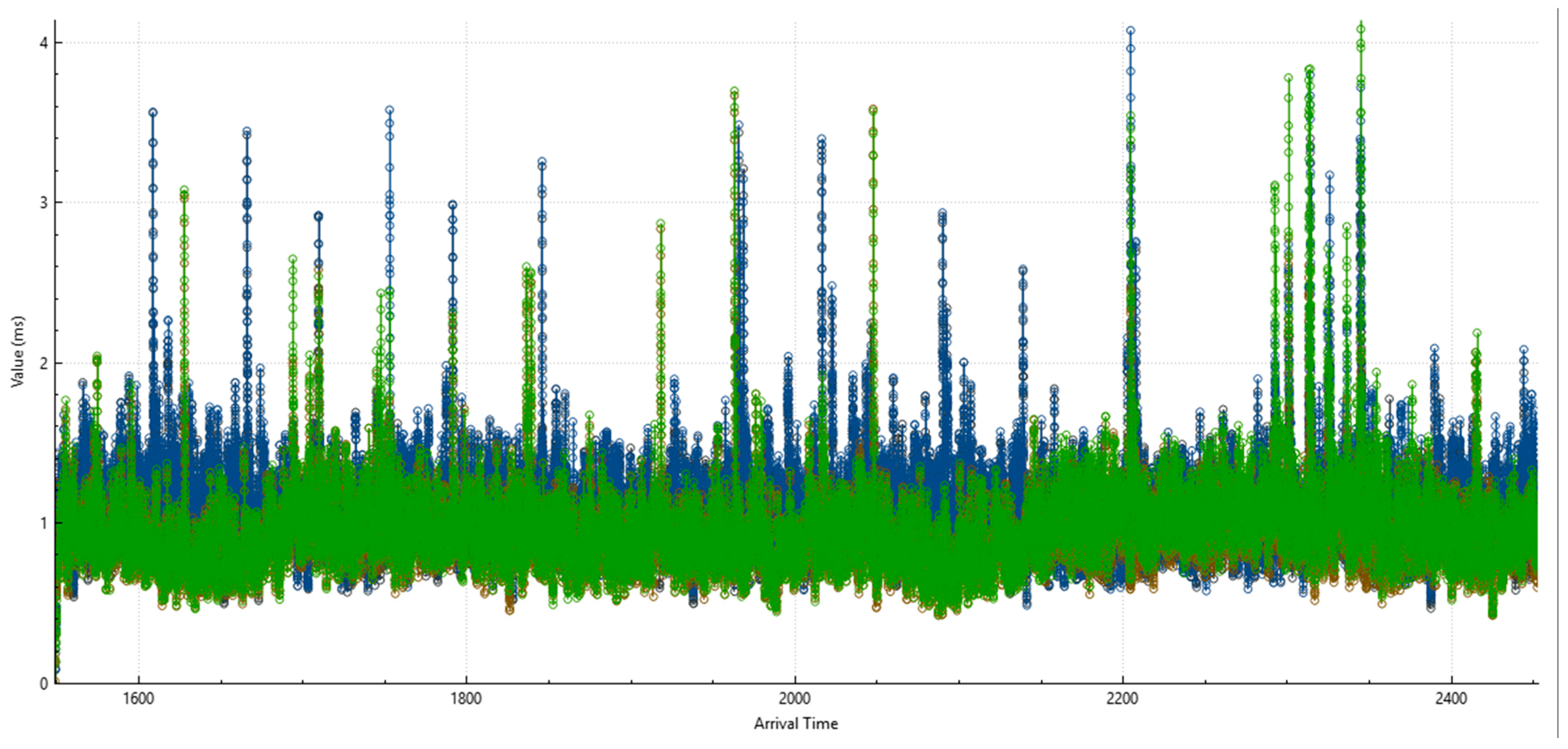

4.2. Results for the Isabella

4.2.1. TCP DoS Attack

4.2.2. UDP Flooding Attack

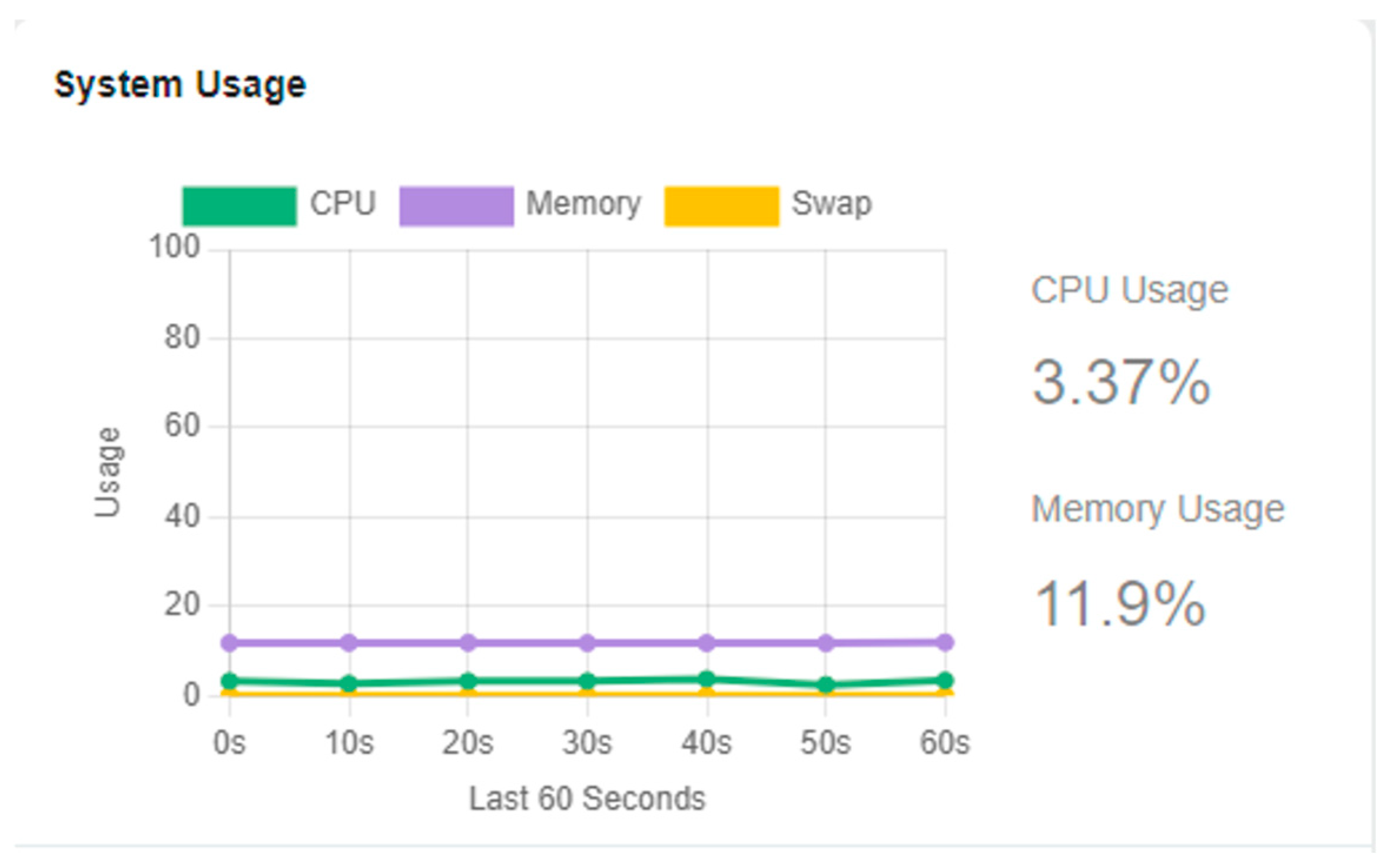

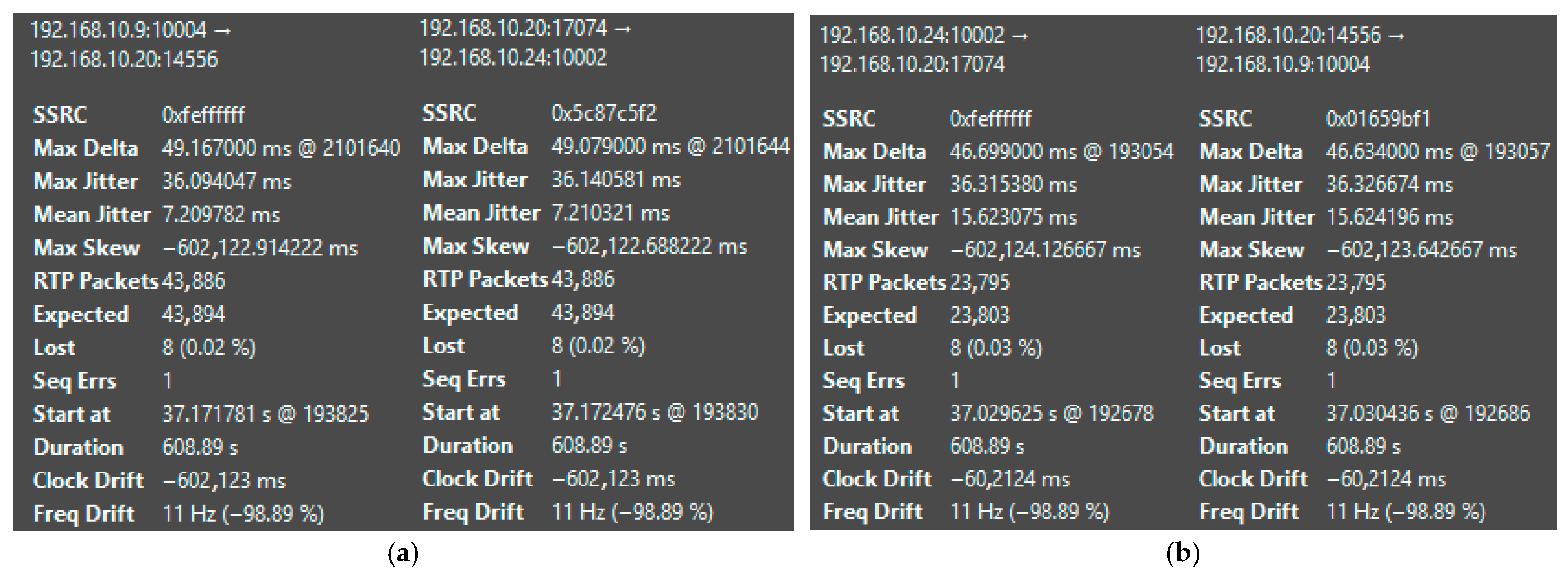

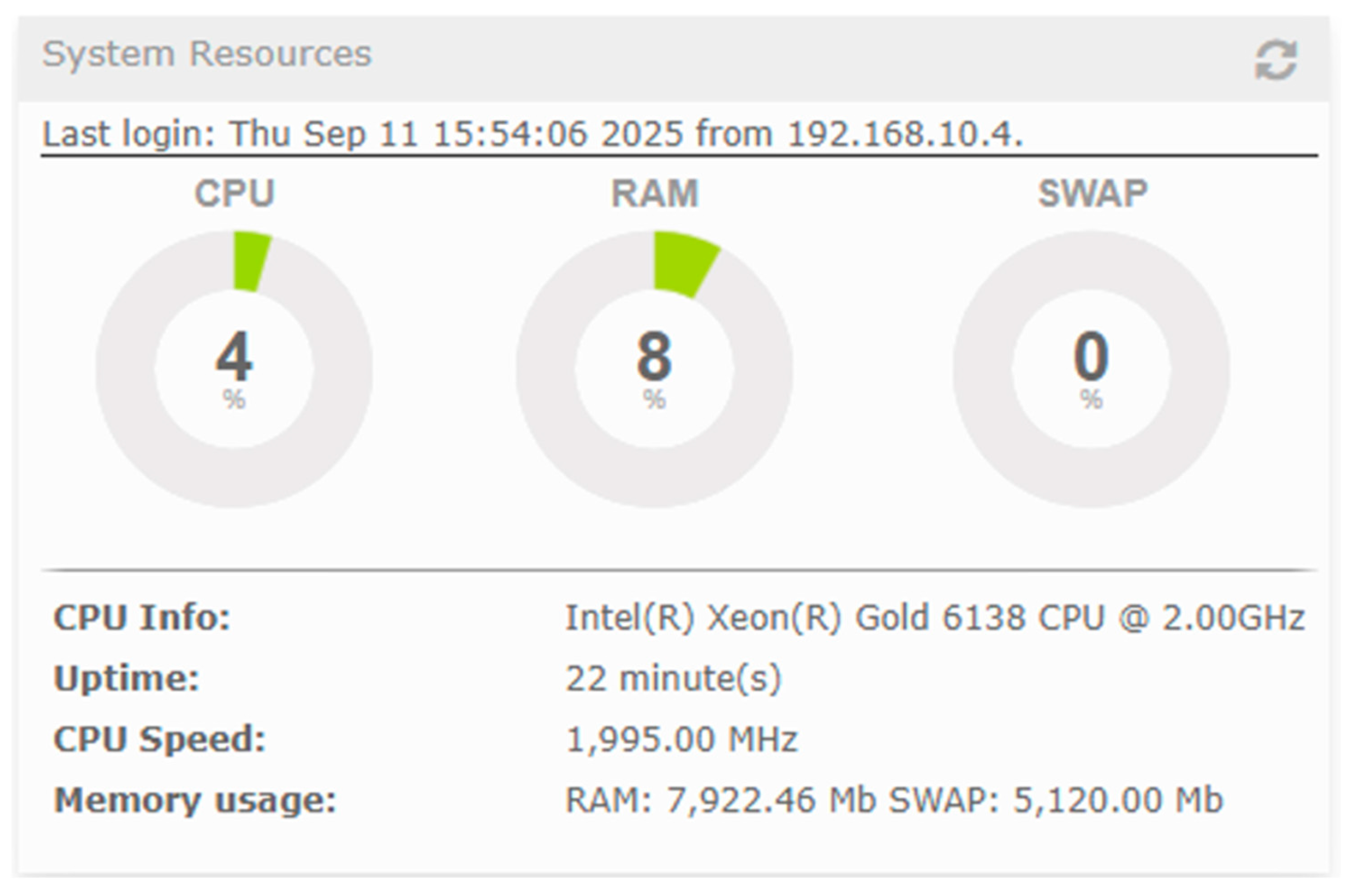

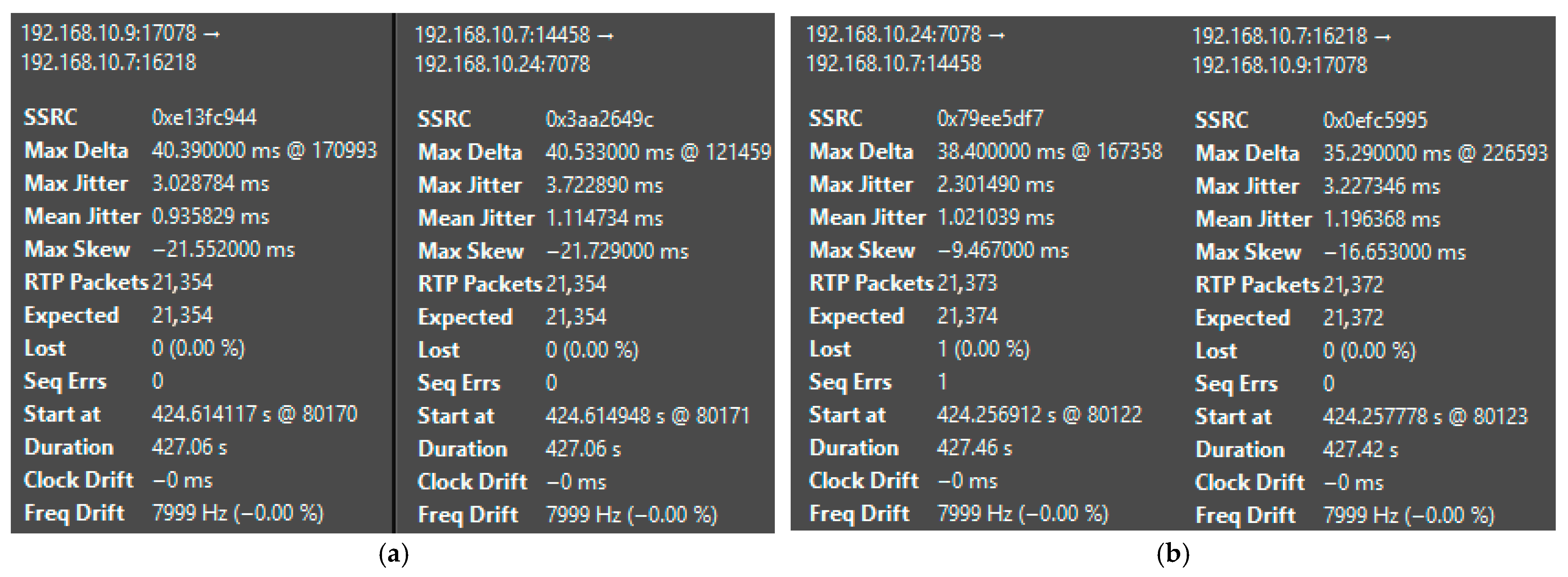

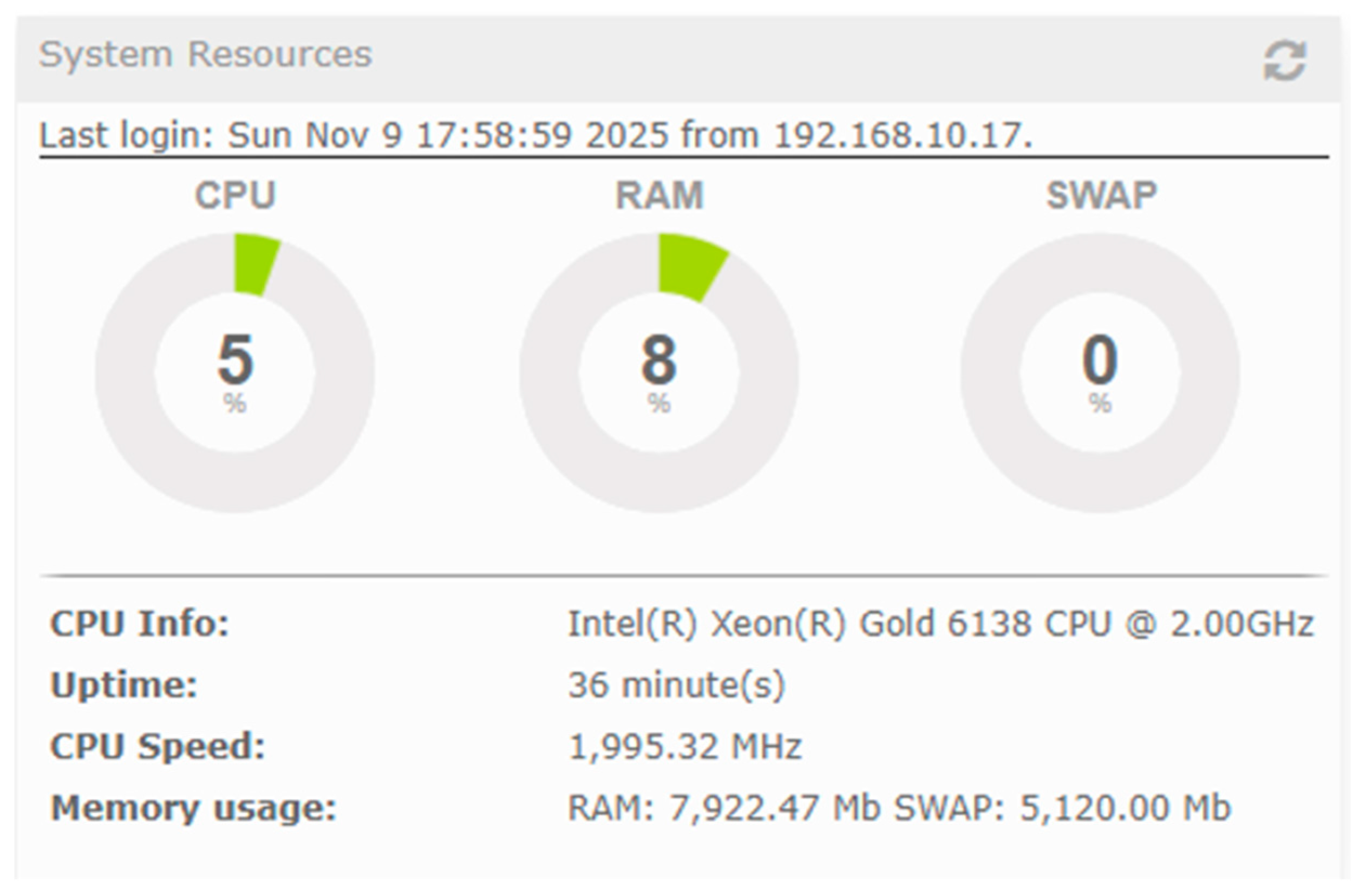

4.3. CompletePBX 5

4.3.1. TCP DoS Attack

4.3.2. UDP Flooding Attack

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussions About the VitalPBX Results

5.2. Discussions About the Issabela Results

5.3. Discussions About the CompletePBX 5 Results

5.4. Summary of Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohamed, A.A.; Eltokhy, A.; Zekry, A.A. Enhanced Multiple Speakers’ Separation and Identification for VOIP Applications Using Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuño, P.; Bulnes, F.G.; Pérez-González, S.; Granda, J.C. Asterisk as a Tool to Aid in Learning to Program. Electronics 2023, 12, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, O.; Elmalech, A.; Hajaj, C. Detecting Parallel Covert Data Transmission Channels in Video Conferencing Using Machine Learning. Electronics 2023, 12, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, M. Artificial intelligence-based model–a key technique in digital economy development for cryptocurrency price prediction. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Secur. 2025, 17, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Hassan, M.R.; al-Qerem, A.; Hamarsheh, A.; Al-Qawasmi, K.; Aljaidi, M.; Abu-Khadrah, A.; Kaiwartya, O.; Lloret, J. Towards a Smart Environment: Optimization of WLAN Technologies to Enable Concurrent Smart Services. Sensors 2023, 23, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, P.M. The 2021–2026 World Outlook for Internet Protocol Private Branch Exchange (IP PBX) Systems; ICON Group International, Inc.: Nevada, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yakubova, M.; Manankova, O.; Mukasheva, A.; Baikenov, A.; Serikov, T. The Development of a Secure Internet Protocol (IP) Network Based on Asterisk Private Branch Exchange (PBX). Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, W.-B. Reference Phone Number: A Secure and Quality of Service-Improved SIP-Based Phone System. Electronics 2025, 14, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazih, W.; Alnowaiser, K.; Eldesouky, E.; Youssef Atallah, O. Detecting SPIT Attacks in VoIP Networks Using Convolutional Autoencoders: A Deep Learning Approach. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, I.M.; Baktir, S. A Novel Approach for Efficient Mitigation against the SIP-Based DRDoS Attack. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalou, W.; Mehdi, M. An Approach to Mitigate DDoS Attacks on SIP Based VoIP. Eng. Proc. 2022, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedyalkov, I. Studying the Impact of Different TCP DoS Attacks on the Parameters of VoIP Streams. Telecom 2024, 5, 556–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Mondéjar, J.; Martinez, J.L.; Suarez-Tangil, G. On how VoIP attacks foster the malicious call ecosystem. Comput. Secur. 2022, 119, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcinnes, N.; Wills, G. The VoIP PBX Honeypot Advance Persistent Threat Analysis. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security–IoTBDS, Prague, Czechia, 23–25 April 2021; pp. 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, B.M.; Fahad, M.; Bilal, R.; Khan, A.H. Performance Analysis of Raspberry Pi 3 IP PBX Based on Asterisk. Electronics 2022, 11, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macron, T. Enhancing VoIP Network Security: An Asterisk-Based System Approach. All Content Following This Page Was Uploaded by Tolu Macron on 27 January 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388419836_Enhancing_VoIP_Network_Security_An_Asterisk-Based_System_Approach (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Nazih, W.; Elkilani, W.S.; Dhahri, H.; Abdelkader, T. Survey of Countering DoS/DDoS Attacks on SIP Based VoIP Networks. Electronics 2020, 9, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafke, J.; Viana, T. Call Me Maybe: Using Dynamic Protocol Switching to Mitigate Denial-of-Service Attacks on VoIP Systems. Network 2022, 2, 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, O.P.; Kumar, V. A Survey on Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) Reliability Research. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1020, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhlurrohman, R.; Triayudi, A.; Sari, R.T.K. VoIP System Implementation Using Issabel as an Integrated IP PBX Server with Telco Vendors. SaNa J. Blockchain NFTs Metaverse Technol. 2024, 2, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazih, W.; Hifny, Y.; Elkilani, W.S.; Dhahri, H.; Abdelkader, T. Countering DDoS Attacks in SIP Based VoIP Networks Using Recurrent Neural Networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, D.; Rughani, P.H. A Comprehensive Study of VoIP Security. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication Control and Networking (ICACCCN), Greater Noida, India, 18–19 December 2020; pp. 812–817. [Google Scholar]

- Tuleun, W. Design of an asterisk-based VoIP system and the implementation of security solution across the VoIP network. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 23, 875–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchuk, S.; Pryimak, S. Voip System with High Availability. Inf. Telecommun. Sci. 2025, 16, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tim, S.; Christina, H. End-to-End QoS Network Design: Quality of Service in LANs, WANs, and VPNs. In Part of the Networking Technology Series; Cisco Press: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2004; ISBN 1-58705-176-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cisco-Understanding Delay in Packet Voice Networks, White Paper. Available online: https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/support/docs/voice/voice-quality/5125-delay-details.html (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Getting Started with GNS3. Available online: https://docs.gns3.com/docs/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Arnaudov, D.D.; Kishkin, K.Y. Modelling and Research of Active Voltage Balansing System for Energy Storage System. In Proceedings of the 2019 X National Conference with International Participation (ELECTRONICA), Sofia, Bulgaria, 16–17 May 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kishkin, K.; Kanchev, H.; Arnaudov, D. Modeling the Influences of Cells Characteristics in Battery Bank. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Symposium on Electrical Apparatus and Technologies (SIELA), Bourgas, Bulgaria, 1–4 June 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sapundzhi, F.; Chikalov, A.; Georgiev, S.; Georgiev, I. Predictive Modeling of Photovoltaic Energy Yield Using an ARIMA Approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapundzhi, F.I.; Popstoilov, M.S. Maximum-Flow Problem in Networking. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 52, 192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hensel, S.; Marinov, M.B.; Koch, M.; Arnaudov, D. Evaluation of Deep Learning-Based Neural Network Methods for Cloud Detection and Segmentation. Energies 2021, 14, 6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashev, T.D.; Marinov, M.B.; Arnaudov, D.D.; Monov, V.V. Computer simulations for determining of the upper bound of throughput of LPF-algorithm for crossbar switch. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2505, 080030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinov, M.; Nikolov, G.; Gieva, E.; Ganev, B. Improvement of NDIR carbon dioxide sensor accuracy. In Proceedings of the 38th International Spring Seminar on Electronics Technology (ISSE), Eger, Hungary, 6–10 May 2015; pp. 466–471. [Google Scholar]

- Kravets, O.J.; Aksenov, I.A.; Redkin, Y.V.; Rahman, P.A.; Kochegarov, M.V.; Gorshkov, A.V.; Sorokin, S.A. Modeling of neural network monitoring agent to predict traffic spikes and agent training. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Secur. 2024, 16, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelmanov, S.S.; Krylov, V.V. Computer simulation of strength testing of an object based on signal shaped resources. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Secur. 2023, 15, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romansky, R. Investigation of communication parameters based on monitoring and statistical modelling. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Secur. 2023, 15, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wireshark User’s Guide. Available online: https://www.wireshark.org/docs/wsug_html_chunked/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- hping3 Tool Documentation. Available online: https://www.kali.org/tools/hping3/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Nmap Reference Guide. Available online: https://nmap.org/book/man.html (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Colasoft Ping Tool. Available online: https://www.colasoft.com/ping_tool/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- VitalPBX Features. Available online: https://vitalpbx.com/pbx-features/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Issabela PBX. Available online: https://www.issabel.com/en/issabel-in-detail/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- CompletePBX5. Available online: https://xorcom.com/pbx-software/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- What Is CSRF. Available online: https://portswigger.net/web-security/csrf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Nedyalkov, I. Studying the Impact of a UDP DoS Attack on the Parameters of VoIP Voice and Video Streams. Future Internet 2025, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, W.; Jekov, B.; Hristov, P. Analysis of the Cybersecurity Weaknesses of DLT Ecosystem. In Software Engineering and Algorithms, In Proceedings of the CSOC, Online, 21 April–2 May 2021; Silhavy, R., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 230. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov, W.; Syarova, S. Analysis of the Functionalities of a Shared ICS Security Operations Center. In Proceedings of the 2019 Big Data, Knowledge and Control Systems Engineering (BdKCSE), Sofia, Bulgaria, 21–22 November 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov, W.; Dimitrov, G.; Spassov, K.; Petkova, L. Vulnerabilities Space and the Superiority of Hackers. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference Automatics and Informatics (ICAI), Varna, Bulgaria, 30 September–2 October 2021; pp. 433–436. [Google Scholar]

- Chithra, P.L.; Aparna, R. Blockchain enabled dual level security scheme with spiral shuffling and hashing technique for secret video transmission. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Secur. 2023, 15, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakesh, V.S.; Vasanthakumar, G.U. Evaluation of supervised classification approach for DDoS threat detection in Software Defined Networks. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Secur. 2024, 16, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, Y. Integrating a DNS monitoring module into a cybersecurity architecture to enhance protection against spoofing and phishing attacks. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Secur. 2025, 17, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.N.; Gore, D.V.; Chavan, A.S.; Nelli, A. MOD-XGBOOST: An adaptive machine learning model for internet of things environment to detect spoofing and dos attacks. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Secur. 2025, 17, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

| Platform | Mean Jitter (ms) | Packet Loss (%) | Delay (ms) | System State | CPU Load (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VitalPBX | 7 | 0.025 | 6 | Stable | 3.6 |

| Issabela | 1.05 | 0.01 | 180 | Stable | 12 |

| CompletePBX 5 | 1 | 0.025 | 2 | Stable | 6 |

| Platform | Mean Jitter (ms) | Packet Loss (%) | Delay (ms) | System State | CPU Load (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VitalPBX | 3.8 | 0.022 | 5 | Stable | 3.37 |

| Issabela | 1.6 | 0.015 | 182 | Stable | 5 |

| CompletePBX 5 | 1.86 | 0.01 | 3 | Stable | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nedyalkov, I.; Georgiev, G. Assessing the Impact of DoS Attacks on the Performance of Asterisk-Based VoIP Platforms. Telecom 2025, 6, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom6040098

Nedyalkov I, Georgiev G. Assessing the Impact of DoS Attacks on the Performance of Asterisk-Based VoIP Platforms. Telecom. 2025; 6(4):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom6040098

Chicago/Turabian StyleNedyalkov, Ivan, and Georgi Georgiev. 2025. "Assessing the Impact of DoS Attacks on the Performance of Asterisk-Based VoIP Platforms" Telecom 6, no. 4: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom6040098

APA StyleNedyalkov, I., & Georgiev, G. (2025). Assessing the Impact of DoS Attacks on the Performance of Asterisk-Based VoIP Platforms. Telecom, 6(4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/telecom6040098