Abstract

The translational and rotational dynamics of quadrotor UAVs are commonly described by mathematical modeling where aerodynamic and inertial parameters are involved. Therefore, the importance of having accurate parameters in the model is critical for the correct performance of the UAV. In this paper, Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are used to estimate the aerodynamic and inertial parameters corresponding to the mathematical model of a quadrotor. Thrust and torque coefficients from the rotor models and the quadrotor inertia matrix are estimated by proposing and training two different ANN models implementing the back-propagation algorithm, using both experimental and simulation data. The estimated parameters are then compared with the reference parameters by means of quadrotor attitude simulations, showing high accuracy in their behavior. The results have shown that the proposed ANN models can accurately estimate both the aerodynamic and inertial parameters of a quadrotor UAV model using both experimental and simulation data, thus contributing to increasing the tools available for parameter estimation.

1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have been the subject of recent research due to their extensive applications and capabilities in many different fields, such as civilian, military, and research [1]. Quadrotors are one of the most popular UAVs because of the advantages their configuration entails, such as vertical takeoff and landing, great maneuverability, and stable hovering [2,3]. Nevertheless, in order for these aircraft to work properly, their behavior has to be fully predictable by means of mathematical models. In this way, control algorithms can rely on what the quadrotor mathematical model outputs, and therefore, the system behavior is as expected. For this reason, it is of great importance that quadrotors not only possess correct structures of mathematical models, but also hold accurate parameters on them, since the variation of these can greatly influence their behavior. Consequently, parameter estimation is a common research topic within the scope of system identification.

Numerous research studies about UAV modeling and system identification have been published, for instance, in [4], where the propulsion system of a quadrotor was experimentally evaluated, characterized, and compared with a simplified model of the system. A wind tunnel was used to avoid disturbances, and a system sensor that can measure forces and torques of the real quadrotor was used for the experimental test bench. The results showed that the modeled quadrotor presented minimal variations due to the absence of considerations, while the experimental results, along with vibrations, had unknown aerodynamic effects. In [5], a review of the most common elements included in quadrotor models reported in the literature was presented. This study showed that various quadrotor applications use simplified models. To evaluate the effectiveness of the simplified models, a comprehensive comparison based on numerical simulations was presented. With this comparison, it was possible to determine the accuracy of each model over specific operating ranges. Authors in [6] presented the application and experimental demonstration of desktop-to-flight design workflow on a high-performance agile maneuvering quadrotor. The frequency-domain system identification process was used to obtain linear mathematical models for hover and forward flight. The results had significant deviations in bare-airframe dynamics of the quadrotor in hover and forward flight conditions. Regarding the classical control design, the optimized controller showed more precision, predictability, and robustness. In [7], various system identification methods for quadrotor UAVs were discussed, focusing on a literature review based on previous research. They also introduced the concept of system identification, outlining its key components, which include experimental planning, model structure selection, parameter estimation, and validation. In [8], system identification of a flight vehicle was carried out by means of black, grey, and white box approaches. The white box approach considered Cook formulas to develop the model structure, where the aerodynamic coefficients were taken from DATCOM computations. On the other hand, black and grey box approaches were empirical mathematical models built from non-linear flight simulator data. The authors concluded that the error in the white box method was due to the incompleteness of inputs and the inconvenience of formulas. Authors from [9] proposed a novel method for system identification to experimentally estimate with precision the dynamic model of a heterogeneous multirotor UAV. The approach included the use of sinusoidal input excitation signals, a filter with sampling frequency, and the derivation of transfer functions by a complex curve fitting method. The obtained transfer functions for the orientation control system were validated using self-tuning PID controllers experimentally designed, showing a stable performance in the presence of atmospheric turbulence. In addition, a flight controller designed with an open architecture microcontroller was used for the experimental implementation. The presented results demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed approach for the heterogeneous multirotor UAV. The modeling and system identification for auto-stabilization of a quadrotor by implementing the Extended Kalman Filter (EFK) was presented in [10]. A more accurate dynamic model by identification and estimation that needed parameters for the quadrotor was aimed at with the two processes, the quadrotor model dynamics and the EKF algorithm implementation. The sequence of the quadrotor study was analyzed with flight missions that started from low speed to high speed of motor rotation, followed by take-off, hover, and landing. The EKF managed to organize the noisy data flow coming from the sensor. This allowed the EKF to be useful for identifying in real-time. In [11], a quadrotor at high-speed flight regime was considered. The authors explored the aerodynamic effects of the quadrotor using flight data in a large-scale wind tunnel. Their findings suggested that at high-speed regime, the quadrotor experienced complex aerodynamic effects that significantly influenced the forces and moments acting on the aircraft. In order to understand such behavior, grey-box models were identified considering the aerodynamic effects and prior knowledge about rotorcraft aerodynamics. In [12], the potential of using control parameters, such as blade rotational speed, and data from drone navigation devices to improve the accuracy of the drone mathematical model parameters was presented. Equations to calculate adequate operation modes of the blades were proposed for a more desired aerodynamic precision in the intend to follow the path while flying. The paper showed the possibility of using control parameters and information received from navigation devices. On the other hand, in [13], the authors carried out a Jet engine online model parameter estimation, where the model parameters were tuned using a Kalman filter, while in [14], the propulsion model of multi-rotor vehicles was proposed and experimentally characterized.

Intelligent strategies within system identification have recently been carried out by several authors. In [15], the authors addressed the use of nonlinear black-box models for dynamical systems, focusing on various structures such as neural networks, radial basis networks, wavelet networks, and hinging hyperplanes, along with methods based on wavelet transforms, fuzzy sets, and fuzzy rules. They presented these approaches within a unified framework from the user’s point of view, highlighting their shared characteristics, the decisions that must be made, and the key factors to consider for the effective application of these techniques in system identification. In [16], a quadrotor control system was designed based on deep neural networks (DNNs) that improves trajectory tracking performance using pre-stored data from previous quadrotor flight control experiments. By applying offline training with relevant flight control experiments and using the DNN, a generalized model of the system was obtained. The authors stated that their model can be evaluated in real time, without the need for prior knowledge of the system, but must rely on previous training data. The proposed method proved its capability to reduce the trajectory tracking error by compensating for controller uncertainties and unknown system dynamics. In [17], the author derived a mathematical relationship between neural network weights and transfer function parameters, where the backpropagation algorithm was implemented in the training. In [18], a genetic algorithm-based method for directly identifying multivariable systems from plant step response data was presented. The technique enabled the identification of globally optimized models for both linear and nonlinear systems, without requiring a differentiable cost function or linearly separable parameters. The approach was validated through comparison with a benchmark identification problem and tested on a laboratory setup for both continuous and discrete-time systems.

Although there is currently a wide variety of tools for parameter estimation, such as least-squares, robust, and Bayesian regression methods, maximum likelihood estimation, and nonlinear optimization, within the scope of UAV system identification, there is a lack of evidence showing the application of ANNs for the estimation of the aerodynamic and inertial parameters of quadrotor UAVs. The main contribution of this paper is to expand the set of available tools for the estimation of the aerodynamic and inertial parameters of a quadrotor UAV by exploring and applying ANNs, using both experimental and simulation data, thus offering an alternative with solid theoretical foundations and practical applicability. ANNs are used to estimate the aerodynamic and inertial parameters from the mathematical model of a conventional X-configuration quadrotor. The mathematical model is developed according to the Newton-Euler formulation, which describes the translational and rotational dynamics of the aircraft. The reference quadrotor model parameters (assumed to be true values) are calculated based on the white-box approach, which in this work applies least-squares to experimental data and makes use of mass properties from the quadrotor CAD model. The ANN parameter estimation (grey-box approach) estimates the quadrotor parameters using both experimental and white-box simulation data through the application of the back-propagation algorithm. The estimated parameters are then compared to the reference parameters, showing high accuracy in the results.

The remaining of this paper is divided as follows: After briefly presenting experimental results from previous work in Section 2, the quadrotor mathematical model is developed and presented in Section 3. The parameter estimation process is introduced in Section 4, and ANN parameter estimation is addressed in Section 5. The results are presented in Section 6, along with a statistical analysis of the accuracy of the estimated parameters. Finally, some conclusions and future work are presented in Section 7.

2. A Case Study

2.1. Previous Work

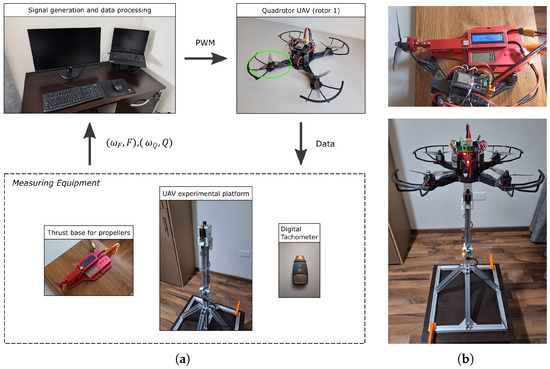

The quadrotor considered in this work is shown in Figure 1a in the upper right corner, and is the same from previous work available in reference [19], where force-torque experimental tests and structural analysis are performed on the quadrotor. The force-torque tests helped to relate the propellers thrust force and torque with the variation of its angular velocity. On the other hand, the structural analysis is carried out to propose a mass-optimized quadrotor frame considering the maximum propeller thrust force obtained in the force-torque experiments.

Figure 1.

Quadrotor experimental tests: (a) Block diagram for data acquisition. (b) Quadrotor under thrust (top image) and torque (bottom image) tests.

2.2. Platform System Setup and Experimental Tests

The platform system consists of a set of measuring equipment that is employed to obtain experimental data from the quadrotor. Two sets of data are considered, one for thrust force measurement and the other for induced torque measurement.

First, a commercial thrust base is acquired to measure the thrust force exerted by the propellers at different motor rotational speeds. Since all propellers are identical, only the thrust measurement of the propeller of motor 1 is considered; that is, only motor 1 is activated to measure the thrust force. Fifty measurements are made by varying the motor spin intensity from 1% to 50% of total thrust. Secondly, a commercial six-axis miniature force-torque sensor is acquired to measure the induced torque generated by the quadrotor propellers, also varying the motor rotational speed. As in thrust measurements, only motor 1 is activated for the torque tests. Figure 1a shows the block diagram for the experimental tests while Figure 1b shows the actual thrust and torque tests with the quadrotor and the measuring equipment.

Note that a platform made of aluminum profiles is created to install the force-torque sensor at a considerable distance from the ground to avoid the ground effect in the experiments. The mounting of both the force-torque sensor and the aluminum platform is referred to as UAV experimental platform and is intended to be used in future research. In this set of tests, similarly to the thrust tests, only motor 1 is activated so that the measured torque values over the vertical axis apply solely to the propeller of motor 1. For this case, twenty measurements are made varying the motor spin intensity from 2% to 40% of total thrust. The sensor sampling rate is established as 1000 samples per second. The tests are carried out using a computer with an Intel Core i7-9750H CPU @ 2.60GHz processor, 12 GB installed RAM, and a NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1660 Ti graphics card, thus being able to perform the measurements at the appropriate sampling rate.

As mentioned before, fifty measurements in the limit from 1% to 50% of total thrust are carried out for the thrust tests and twenty measurements in the limit from 2% to 40% of total thrust for the torque tests. The quantity of experiments is proposed due to time constraints and the extensive scope of the experimental design. On the other hand, the upper limits of 50% and 40% of total thrust are established taking into consideration a safety margin for the measuring equipment, and also considering the average thrust force of each motor to maintain the quadrotor in hover, which is around 1.6 N per motor. The proposed limits for the experimental tests are chosen to provide meaningful results while maintaining the quality and reliability of the quadrotor in practical applications.

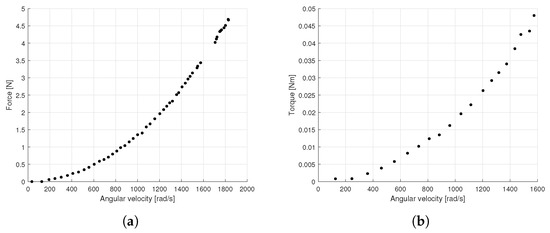

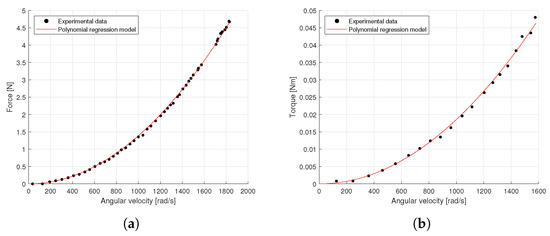

In parallel with each force and torque test, a digital tachometer is used to measure the RPM of the rotor. The information provided by the tachometer helps to match the force and torque data with their corresponding rotational speeds, according to each test carried out with the thrust base and UAV experimental platform, respectively. The results of both sets of experiments, that is, force and torque tests, are shown in Figure 2. Note that the rotor angular velocity is presented in rad/s for ease of data handling. On the other hand, the characteristics of the measuring equipment used to perform the experimental tests are presented in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Experimental propeller data: (a) Thrust force. (b) Induced torque.

Table 1.

Measuring equipment characteristics.

As mentioned before, all the thrust and torque experimental tests are conducted using only one motor-prop unit since the main objective is to experimentally characterize the relationship between thrust force, induced torque and RPM of the same unit that is employed in all 4 arms of the quadrotor. However, it is known that there may exist variations in the untested motor-prop units caused by possible manufacturing defects or small imbalances. Even the calibration of electronic speed controllers (ESCs) can cause variations, since they are the devices that receive the throttle signal and modify the duty cycle and frequency of the output voltage waveform to adjust the motor speed and torque [20]. Due to time constraints and simplicity in the experimental tests, the remaining motor-prop units (which include motor 2, 3 and 4) are not considered for the experimental tests, nevertheless, they are planned to be considered for future research as well as a variation analysis of these.

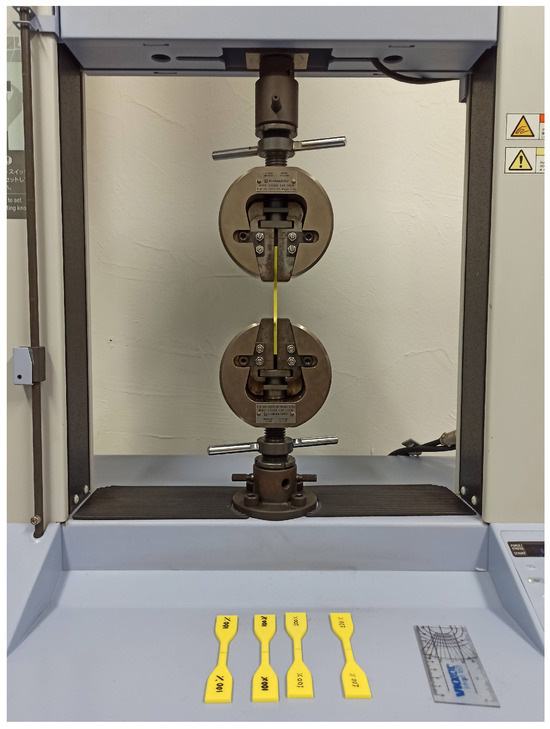

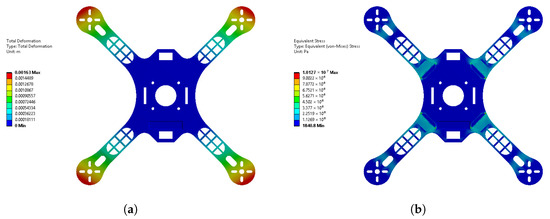

2.3. Quadrotor Structural Analysis

The 3D-printed quadrotor frame presents a buckling problem in the arms when the rotors generate thrust. The frame is upgraded by adding more mass to it, thus solving the buckling problem. Nevertheless, the increase in mass is significantly high, making the quadrotor 44% heavier and therefore less efficient. For this reason, three different quadrotor frames are proposed, and structural analyses are carried out to evaluate their performance when thrust loads are applied at the end of the arms. In order to do this, first the mechanical properties of polylactic acid (PLA) had to be calculated by means of experimental tensile tests using 3D-printed PLA specimens at 100% infill density (see Figure 3). The results of the tensile tests could determine the stress-strain curve of PLA, from which the mechanical properties could be calculated. The Elastic Modulus, Ultimate Tensile Strength, and Yield Strength were calculated, showing 1.94 GPa, 41.38 MPa, and 16.02 MPa, respectively. Once the mechanical properties of PLA are calculated, these are uploaded to the Ansys software (Research Version 2024), and the structural analyses are performed with each frame proposal. In each structural analysis, a force of 4.5 N is applied on each arm of the quadrotor frame, and the center is fixed, evaluating the buckling effect. The best results are obtained with proposal 2 (see Figure 4), showing 41% of mass reduction, with a maximum deformation of 1.63 mm at the end of the arms and a maximum stress of 10.12 MPa at the beginning of the arms. Such results complied with the quadrotor structural limits and solved the buckling problem.

Figure 3.

PLA specimens tensile tests.

Figure 4.

Structural analysis of quadrotor frame: (a) Total deformation. (b) Equivalent stress.

3. Quadrotor Mathematical Model

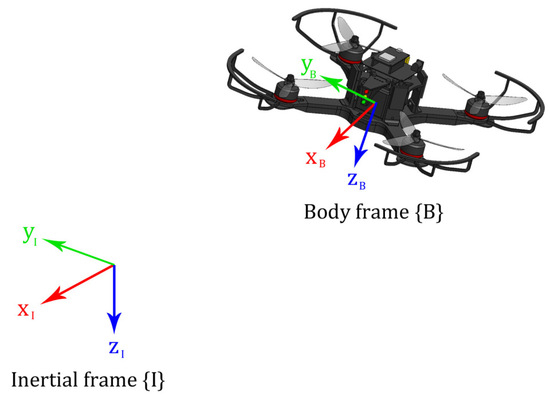

The Newton-Euler formulation is employed to determine the mathematical model of the quadrotor UAV. This formulation consists of a set of differential equations that describe the quadrotor translational and rotational movements. It contemplates two reference frames; one inertial frame fixed to the surface of the Earth which is defined as and a body frame attached to the center of gravity of the quadrotor represented as . Figure 5 shows graphically both frames.

Figure 5.

Inertial and body reference frames.

The formulation assumes that the quadrotor is a rigid body and its center of mass is attached and matches the body frame . The model is defined as:

where Equations (1) and (2) describe the translational dynamics while Equations (3) and (4) describe the rotational dynamics of the quadrotor. represents the spatial coordinates with respect to the inertial frame and denotes the rotation coordinates of the quadrotor UAV. The orientation of the quadrotor with respect to the inertial frame is obtained by means of the rotation matrix (Equation (5)), which is parameterized by the Euler angles roll, pitch, and yaw, representing a rotation with respect to the x, y, and z axis, respectively. In adherence to the convention, the quadrotor orientation with respect to the inertial frame can be described using the rotation matrix:

where , , , , , and are cosine and sine operations with the Euler angles as arguments, correspondingly. represents the angular velocities in the body frame . is the translational velocity vector with respect to the inertial frame . is the quadrotor total thrust with acting as the entire vertical component of thrust in the body frame . is the vector of torques produced by the actuators. In addition, vectors , , and represent the canonical basis vectors of . The terms and m/s2 represent the quadrotor mass and the Earth standard gravity, respectively. The matrix contains the quadrotor principal moments of inertia [21].

The quadrotor vertical component of thrust in the body frame is expressed as where indicates the force exerted by each motor. Both forces and torques are expressed as a function of the angular velocity of the motors. represent the force and the reactive torque of the motor, where is the angular velocity and and are the thrust and torque coefficients respectively.

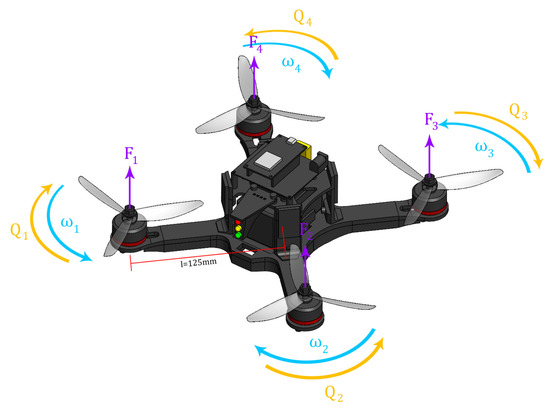

Furthermore, the roll dynamics produced by the actuators is expressed as , for pitch dynamics is , and for yaw dynamics , where with l as the quadrotor arm length. Figure 6 shows the quadrotor forces and moments convention.

Figure 6.

Quadrotor forces and moments convention.

Lastly, Equation (6) presents the matrix needed to convert the quadrotor angular velocity from the body frame to the inertial frame .

Considering all the mathematical statements previously expressed and according to Equations (1)–(4), the expanded form of the quadrotor mathematical model is presented, where Equations (7) and (8) describe the quadrotor translational dynamics while Equations (9) and (10) describe its rotational dynamics, assuming all parameters are well-known.

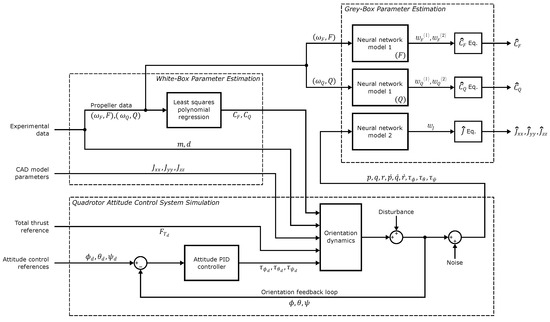

4. Parameter Estimation Overview

The quadrotor parameter estimation process proposed in this research work is presented in Figure 7. According to the diagram, the neural network approach for parameter estimation (also referred as grey-box parameter estimation) is carried out employing both experimental and simulation data. The experimental data is taken from previous work [19], where thrust force and induced torque data from the quadrotor propeller were measured along with their corresponding motor rotational speeds, as presented in Section 2. On the other hand, the simulation data is obtained from a quadrotor dynamics simulation, which outputs angular velocities, angular accelerations, and torque data. Note that the dynamics simulation considers the quadrotor parameters estimated by means of the white-box parameter estimation process. Therefore, the parameters estimated by means of the white-box approach are considered as true values and these are referred to as reference parameters throughout this work.

Figure 7.

Diagram of the proposed quadrotor parameter estimation process.

4.1. White-Box Parameter Estimation

According to the mathematical model previously developed in Section 3, the parameters that fully describe the quadrotor dynamics are the mass (m), arm distance (d), aerodynamic coefficients ( and ) and inertia matrix elements (, , and ). The mass and arm distance are variables that can be easily measured employing physical devices; therefore, in this work, these parameters are estimated by directly measuring the quadrotor mass and arm distance employing a digital scale and measuring tape, respectively, also verifying the arm distance value with the quadrotor CAD model. However, the aerodynamic and inertial parameters are variables that cannot be measured in a direct manner using a physical device. For this reason, in this work, the inertial parameters are extracted from the mass properties of the quadrotor CAD model, and the aerodynamic coefficients are estimated using the propellers experimental data.

In order to determine the aerodynamic coefficients ( and ), the sets of data from the experimental tests and are used and a least-squares polynomial regression model [22] is applied to each set of data. Since both data can perfectly fit on a second-order polynomial starting at the origin, the models are represented as:

where

correspond to the propeller thrust and torque coefficients, respectively. Recall that all summations are from through for the thrust coefficient and from through for the torque coefficient, according to the number of experimental tests carried out on each set of data. The comparison between the experimental data and the polynomial regression models of the quadrotor propellers is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Polynomial regression models of quadrotor propellers: (a) Thrust model. (b) Torque model.

To sum up, the results of the quadrotor reference parameters estimated by means of the white-box approach are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quadrotor reference parameters according to white-box parameter estimation.

4.2. Dynamics Simulation

The quadrotor dynamics simulation is carried out using MATLAB® Simulink®. The simulation consists of an attitude control system, where the orientation and total force are the system references and the angular velocities, angular accelerations, and torques are the output variables. Disturbance and noise are added to the orientation dynamics output to simulate sensor output data.

The desired reference value for the total force is , while the desired reference signals for the orientation angles are , and , where the force and angles are measured in Newtons and radians, respectively.

PID controller is chosen as the quadrotor attitude controller where the inputs are the errors between the desired and actual orientation angles, which are , and .

The controller output variables are specified as the quadrotor torques, which are defined in accordance with the proposed control law shown in Equation (15), where gain factors , , and from each orientation angle are manually tuned to stabilize the quadrotor while following the references. Since analytical tuning is not practical for the purposes of this work, the PID gain factors are tuned empirically by observing the quadrotor states in the time-domain response. A stable and well-damped response is found with the values shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

PID attitude controller gain factors.

Consider the vector as the vector containing the total force and torques, and the vector as the vector that contains the inputs to the quadrotor mathematical model, which are the propeller quadratic velocities. According to the mathematical model, the total force and torques can be expressed in the form , where contains the parameters , , and d. The expanded expression is shown below.

The input vector U is obtained by the expression where becomes , that is , hence:

is the expression used to find the quadratic velocities (desired velocities), which are the inputs to the quadrotor mathematical model that consequently produces its orientation dynamics following the reference signals.

The simulation is performed for 5 s, and the variables of interest are extracted from the system response. Recall that the quadrotor parameters used in the simulation are presented in Table 2, where coefficients and were determined by means of least-squares polynomial regressions employing experimental data, and the inertial matrix parameters , , and were obtained from SolidWorks software (Version 2021).

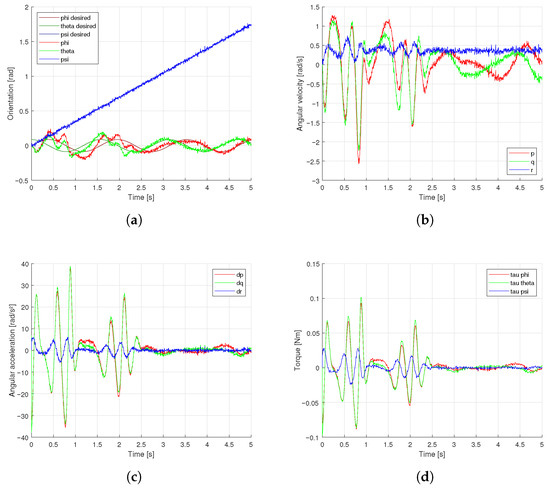

The results of the quadrotor dynamics simulation are presented in Figure 9. Note in Figure 9a that the quadrotor is disturbed between 0[s] and 2.5[s] simulation time and recovers its roll and pitch angles at around 4[s] simulation time.

Figure 9.

Quadrotor attitude control simulation results: (a) Orientation. (b) Velocity. (c) Acceleration. (d) Torque.

5. Neural Networks for Parameter Estimation

The quadrotor mathematical model, as discussed earlier, possesses parameters that characterize the behavior of the vehicle. In this section, the aerodynamic and inertial parameters of the quadrotor mathematical model are estimated through the application of artificial neural networks. In order to ensure full control over the architecture and training process, every neural network in this work is manually developed in the MATLAB R2020a software. Neural network layers, activation functions, and gradient descent optimization routines are manually implemented without reliance on pre-existing machine learning toolboxes or external frameworks. All of the neural networks are trained on a machine with an Intel Core i7-9750H CPU @ 2.60 GHz processor, 12 GB installed RAM, and a NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1660 Ti graphics card.

The neural network architecture contemplates solely linear activation functions in the hidden (if applicable) and output layers, for both aerodynamic and inertial parameters. This is to be able to comply with the structure of the equations that describe the quadrotor thrust, torque, and angular accelerations. Furthermore, the architecture considers only the update of weights, without including bias, since the non-linearities are described by the mathematical model of the quadrotor, thus being able to optimize the size of the neural network. Lastly, the Batch Gradient Descent is used as the optimizer for both neural network models, implementing the back-propagation algorithm with the delta rule as the learning rule and mean squared error (MSE) as the loss function.

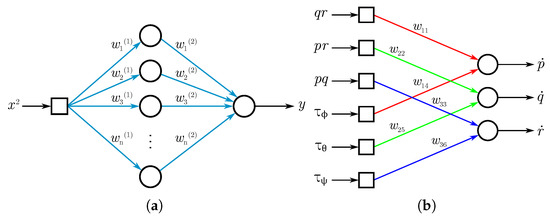

5.1. Aerodynamic Parameters

The aerodynamic parameters and from the quadrotor mathematical model are estimated using the quadrotor experimental data through the training of a neural network for each parameter. The proposed neural network architecture for this application is shown in Figure 10a, which consists of one input and one output nodes and a hidden layer of n nodes. Note that the input node receives a quadratic value , which represents the propeller quadratic velocities. One output node y is proposed, which outputs the force or torque values, as the case may be. Furthermore, a hidden layer of n nodes is considered to evaluate the training behavior as the number of neurons increases.

Figure 10.

Proposed neural network models: (a) Model 1; used for aerodynamic parameters estimation. (b) Model 2; used for inertial parameters estimation.

The weights are represented as follows:

The weighted sum of the nodes from the hidden layer are:

Then, the output of the hidden layer is calculated as:

where () executes the activation function of the argument.

The weighted sum of the output node is expressed as:

Lastly, the output from the neural network is:

For linear activation functions in the hidden and output layers:

Thus, the output of the neural network can be re-written as:

Note that Equation (25) has the same structure as a second-order polynomial starting at the origin, where the weights multiplication represents the leading coefficient. In the same way, this equation is equivalent to the quadrotor force and torque expressions from the mathematical model:

therefore, the proper adjustment of weights and on Equation (25) leads to finding the aerodynamic parameters and by employing the force and torque experimental data. Nevertheless, data normalization has to be done before training the neural network since the experimental data contains values greater than 1.

Let and be the input and output vectors of the quadrotor experimental tests data, respectively. Then, input x and output d are scaled according to the following expressions:

where and are the scaling factors, which are calculated as follows:

Since the correct output d is compared to the neural network output y in order to minimize the cost function, and considering that the correct output is now scaled by the factor , this implies that the neural network output is also scaled by the same factor. Therefore, the neural network scaled output is expressed as:

Replacing the scaled values and into Equation (25), it is obtained:

developing the quadratic term and solving for y, it becomes:

where x and y are the input and neural network output without scaling, respectively. The weights multiplication multiplied by the scaling expression represents the leading coefficient.

Aerodynamic parameters and are estimated by training two separate neural networks, according to each parameter. The training data for both forces and torques are scaled, and then the back-propagation algorithm is applied as the learning rule, so the weights of both neural networks are adjusted to minimize the cost functions. Once the cost functions are minimized and the errors converge to zero, it is said that the weights of both neural networks have been properly updated. Nonetheless, since the weights are updated using scaled data, these possess scaled values and therefore the outputs of both neural networks are also scaled. Then, the expression from Equation (31) is performed in order to descale the values of the weights and therefore be able to handle unscaled data.

Force and torque equations are equivalent to Equation (31) as follows:

therefore, the aerodynamic coefficients are calculated based on each neural networks descaled weights:

where , and , are the scaling factors for the thrust force and induced torque data, respectively.

Using the thrust and torque experimental data, two neural networks are trained as previously outlined, considering four neurons in the hidden layer of each. Training for thrust data has taken approximately 0.2431 s for 2000 epochs on the dataset of 50 samples, using a batch size of 50. For torque data, training has taken around 0.0952 s for 2000 epochs on the dataset of 20 samples, using a batch size of 20.

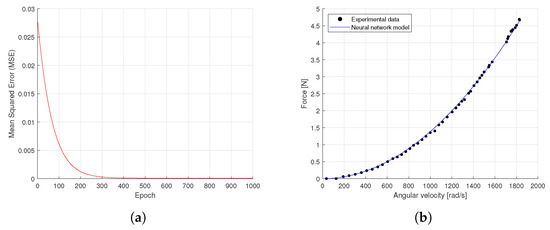

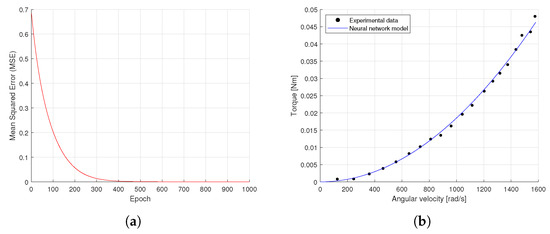

After both neural networks are trained, the quadrotor parameters and are estimated by means of Equations (34) and (35), respectively. Figure 11 and Figure 12 show the neural network thrust and torque models of the rotor, respectively. Note in Figure 11a and Figure 12a the evolution of the cost function (Mean Squared Error) through the training epochs, where it can be seen that in both cases the error converged to zero around epoch 500. On the other hand, Figure 11b and Figure 12b show the output of the neural network (thrust and torque models) in comparison with the experimental data, according to each case.

Figure 11.

Neural network thrust rotor model: (a) Mean Squared Error. (b) Thrust model.

Figure 12.

Neural network torque rotor model: (a) Mean Squared Error. (b) Torque model.

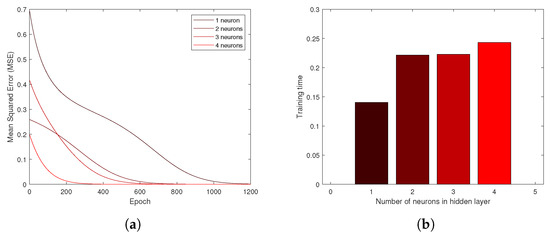

The relationship between the number of neurons in the hidden layer and the learning rate of the neural network is shown in Figure 13a. Note that as the number of neurons increases, the Mean Squared Error (MSE) converges to zero requiring fewer training epochs. This is a general behavior since the initial conditions of the weights (which are randomly assigned) also affect the learning process. Although it is currently confusing and difficult to determine the number of hidden layers and the number of neurons in each hidden layer, there have been efforts to determine these values based on the number of training examples and the complexity of the classification, as addressed in [23].

Figure 13.

Effect of neurons in the hidden layer: (a) MSE over training epochs. (b) Training time with fixed number of epochs.

The time employed by the neural network to converge to a minimum MSE is referred to as the training time [24]. Note in Figure 13b that as the number of neurons increases, the training time increases as well, considering a fixed number of epochs. This illustrates the significance of the number of neurons in the hidden layer over the training time. However, it is still not possible to obtain a standard relationship to determine the number of neurons to be used in ANN optimization [25].

Another important aspect in ANNs are the activation functions which, as previously seen, are used to transform an input signal into an output signal which in turn is fed as input to the next layer in the stack [26]. There are many types of activation functions that can be used depending on various factors such as type of task or data characteristics. For instance, the literature recommends activation functions such as Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU), sigmoid, and tanh. On the other hand, activation functions like step, softsign, and softplus are not recommended, according to the authors from [27]. New theoretical characterization to support the popular ReLu activation function is added by authors in [28]. However, the application of non-linear activation functions particularly in this work would result in not complying with the structure of the mathematical model of the quadrotor, reason why only linear activation functions are contemplated in all of the ANN architectures from this work.

5.2. Inertial Parameters

The proposed neural network architecture to estimate the quadrotor inertial parameters (, , and ) is shown in Figure 10b. Note that it is a single-layer neural network which receives six inputs that represent the quadrotor angular velocities multiplications (, , and ) and the actuators torques (, , and ) and outputs the angular accelerations (, , and ). Also note that for this scenario, not all of the neural network nodes are connected to each other, thus being known as a Sparse Neural Network (SNN). SNNs are neural architectures in which not all of the neurons are connected to each other. In addition, these types of ANNs have proven to be an effective solution to reduce computation and memory demands [29]. However, the fact that the proposed neural network is decided as SNN is not related to computation and memory demands, but rather because not all of the input variables are related to each output variable, according to the quadrotor mathematical model.

The input vector x, the output vector y, as well as the weights matrix are defined as follows:

The weighted sums of the output nodes are calculated as:

The neural network output is:

For linear activation function:

Therefore, the neural network output is expressed as:

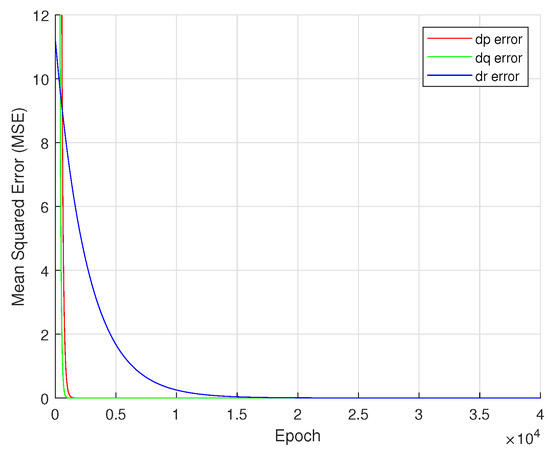

Training of the neural network is carried out using the data from the quadrotor attitude control simulation. The generalized delta rule is applied as the learning algorithm in order to minimize the cost function. Training has taken approximately 2.1454 s for 40,000 epochs on the dataset of 2063 samples, using a batch size of 2063. Figure 14 shows the MSE cost function through the epochs. Note that for and the error converged to zero in a more prompt manner compared to , which converged at approximately epoch 20,000. This shows that the number of epochs plays a crucial role in the training process of a neural network model [30].

Figure 14.

Mean Squared Error through epochs on inertial parameters estimation.

Recalling the expressions of the quadrotor angular accelerations from Equation (10) and according to the structure of the proposed neural network, the following equivalences are stated:

The principal moments of inertia are then estimated as:

6. Results

The training settings for each neural network model are summarized in Table 4. Note that in both neural network models, the number of epochs needed to achieve favorable results is high since the learning rate is affected by not including bias in the neural network architecture.

Table 4.

Training settings summary according to each neural network model.

The estimated aerodynamic and inertial parameters are presented in Table 5. Note that the values of the estimated parameters closely match the reference parameters previously shown in Table 2, however, quantitative measurement of the error is fundamental for the analysis of the results. Table 6 shows the comparison and error between the reference and estimated parameters. Note that most of the parameters achieved less than 1% error; nevertheless, the inertial parameter had an error of 2.0838%. Although it is a relatively small error, this variability might considerably impact the quadrotor dynamics. For this reason, an evaluation of the quadrotor mathematical model with the estimated grey-box parameters is considered.

Table 5.

Quadrotor estimated parameters according to grey-box parameter estimation.

Table 6.

Comparison and error between white-box and grey-box parameter estimation results.

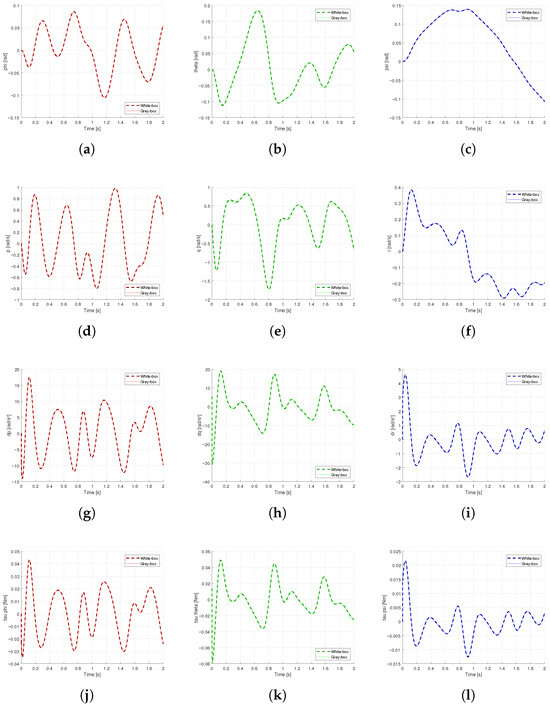

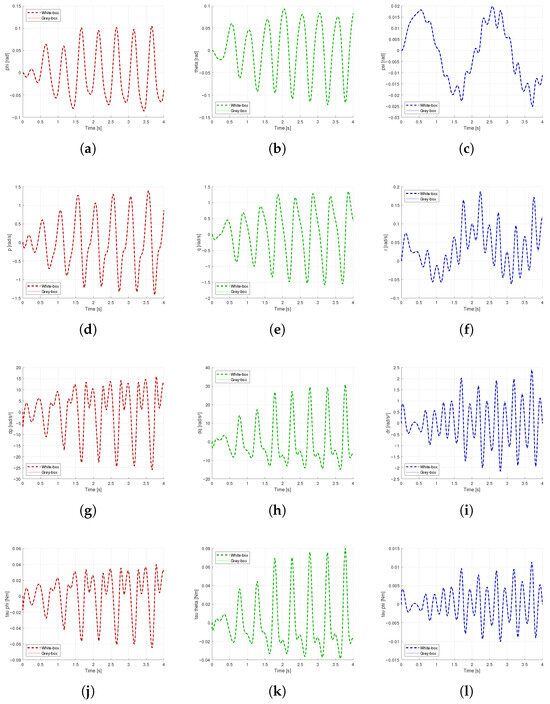

In order to evaluate the results, two different simulations of the quadrotor mathematical model with the estimated parameters are carried out using MATLAB® Simulink®.

Both simulations (simulation 1 and simulation 2) consist of the same attitude control system previously employed in the dynamics simulation from Section 4.2, but with different reference signals and without adding noise to the output. Simulation 1 is set to a total of 2 s of simulation time, while simulation 2 with a total of 4 s of simulation time. The desired reference value for the total thrust in both simulations remains in . The desired reference signals for the orientation angles in simulation 1 are , and . The desired reference signals for the orientation angles in simulation 2 are , and .

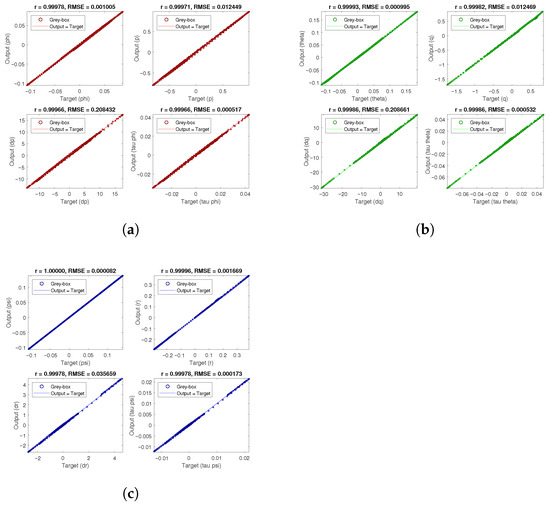

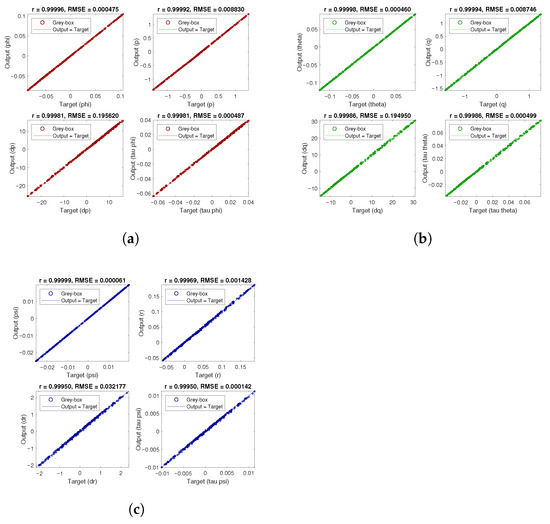

The results from simulation 1 and simulation 2 are presented in Figure 15 and Figure 16, respectively. Note that based on the quadrotor response, the white-box and grey-box results are closely aligned in all of the output variables, showing high accuracy. On the other hand, Figure 17 and Figure 18 show the correlations between white-box and grey-box results from simulation 1 and simulation 2, respectively, in all three axes where in all cases the outputs have a linear trend and closely match the targets, meaning high precision and accuracy. Lastly, the correlation results from both simulations are summarized in Table 7. Pearson r and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between white-box and grey-box results determine that the estimated aerodynamic and inertial parameters produce accurate and precise results in the quadrotor dynamics response.

Figure 15.

Comparison of quadrotor simulation 1 output variables between white-box and grey-box parameters: (a) . (b) . (c) . (d) p. (e) q. (f) r. (g) . (h) . (i) . (j) . (k) . (l) .

Figure 16.

Comparison of quadrotor simulation 2 output variables between white-box and grey-box parameters: (a) . (b) . (c) . (d) p. (e) q. (f) r. (g) . (h) . (i) . (j) . (k) . (l) .

Figure 17.

Correlation between grey-box and white-box results from validation simulation 1: (a) x-axis variables. (b) y-axis variables. (c) z-axis variables.

Figure 18.

Correlation between grey-box and white-box results from validation simulation 2: (a) x-axis variables. (b) y-axis variables. (c) z-axis variables.

Table 7.

Pearson r and RMSE between white-box and grey-box results from validation simulations output variables.

According to both simulations output variables and statistical results, it can be said that the 2.0838% of error in the inertial parameter from the grey-box approach does not significantly affect the overall results of the quadrotor dynamics compared to the white-box results, thus achieving adequate performance with the estimated parameters.

7. Conclusions

In this work, Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have been implemented to estimate the aerodynamic and inertial parameters from the mathematical model of a quadrotor. The proposed ANN models have allowed building the structure of the quadrotor UAV mathematical model in accordance with the Newton-Euler formulation, and its aerodynamic and inertial parameters have been estimated by employing the back-propagation algorithm.

The aerodynamic coefficients of the quadrotor propellers were estimated by designing a neural network architecture, one of which was trained with experimental thrust and the other with torque data. On the other hand, the quadrotor inertia matrix was estimated thanks to the design and training of a neural network that employed both experimental and simulation data. The estimated parameters showed high accuracy compared to the reference parameters of the quadrotor in study. In addition, two dynamics simulations of the quadrotor using the estimated parameters were performed. From the dynamics simulations results, a minimum percentage of error is observed compared to the dynamics simulations results with the reference parameters.

Having used experimental data to carry out the estimation of the aerodynamic parameters from the quadrotor UAV model has been beneficial to obtain results that better reflect real-world conditions and thus, to estimate its parameters more accurately.

An alternate approach for quadrotor parameter estimation applying ANNs has been presented. However, since the experimental data is only considered for the aerodynamic parameters, the question of whether the inertia matrix parameters of the built quadrotor are accurate remains unanswered, since the inertial reference parameters were obtained from the quadrotor CAD model. For this reason, experimental data with an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) is considered for future work, in order to obtain the actual angular accelerations and velocities exerted by the built quadrotor, and thus to accurately estimate the inertia matrix parameters that belong to the built quadrotor. By properly estimating the aerodynamic and inertial parameters from the mathematical model of a quadrotor UAV, the excitation response of the system in a real-world engineering application will be more accurate, thus allowing the correct design of attitude and navigation controllers.

Based on the results obtained, it is suggested that future researchers contemplate generating a complete and extensive experimental database prior to the parameter estimation process, with the objective of obtaining results that are as accurate and true to real conditions as possible, allowing for future effective application in real quadrotor flights and implementation of control algorithms.

Since this work focused on estimating the aerodynamic and inertial parameters from the mathematical model of a quadrotor UAV, future research could examine the performance of the estimated parameters by evaluating navigation aspects as a consequence of the differences in the orientation results.

Finally, this work opens up the possibility of exploring the use of ANNs to propose new architectures that can represent the mathematical models of diverse UAVs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.-F.; methodology, E.J.O.-V. and O.G.-S.; software, A.J.-F. and P.A.T.-B.; validation, A.J.-F. and E.J.O.-V.; formal analysis, A.J.-F. and E.J.O.-V.; investigation, A.J.-F. and E.J.O.-V.; resources, L.A.R.-O., L.A.-B. and O.G.-S.; data curation, A.J.-F. and P.A.T.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.-F.; writing—review and editing, A.J.-F. and E.J.O.-V.; visualization, L.A.R.-O. and L.A.-B.; supervision, O.G.-S.; project administration, O.G.-S.; funding acquisition, O.G.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work is funded by the U.S. Office of Naval Research Global under Grant N629092512014.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Faculty of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering at the Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon (CIIIA-FIME-UANL) and the Technological Institute of La Laguna-TecNM.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tang, G.; Ni, J.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Cao, W. A survey of object detection for UAVs based on deep learning. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Yang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhao, L. Trajectory Planning of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Complex Environments Based on Intelligent Algorithm. Drones 2025, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Quan, W.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Tian, Y. Structural Parameter Optimization of the Vector Bracket in a Vertical Takeoff and Landing Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Aerospace 2025, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabela, R.; Santana, C.; Naranjo, A.; Amezquita-Brooks, L.; Liceaga-Castro, E.; Torres-Reyna, M. Experimental characterization of a small and micro unmanned aerial vehicle propulsion systems. In Proceedings of the AIAA Atmospheric Flight Mechanics Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 4–8 January 2016; p. 1530. [Google Scholar]

- Amezquita-Brooks, L.; Liceaga-Castro, E.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, M.; Garcia-Salazar, O.; Martinez-Vazquez, D. Towards a standard design model for quad-rotors: A review of current models, their accuracy and a novel simplified model. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 95, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksek, B.; Saldiran, E.; Cetin, A.; Yeniceri, R.; Inalhan, G. System identification and model-based flight control system design for an agile maneuvering quadrotor platform. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2020 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–10 January 2020; p. 1835. [Google Scholar]

- Legowo, A.; Sulaeman, E.; Rosli, D. Review on system identification for quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). In Proceedings of the Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 26 March–10 April 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nugroho, L.; Akmeliawati, R. Comparison of black-grey-white box approach in system identification of a flight vehicle. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1130, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshu, A.A.; Wang, L.; Ansari, S.; Sattar, A.; Bilal, M.H.A. System identification of heterogeneous multirotor unmanned aerial vehicle. Drones 2022, 6, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, N.; Legowo, A.; Ibrahim, Z.; Rahim, N.; Kassim, A.M. Modeling and system identification using extended kalman filter for a quadrotor system. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 313, 976–981. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; de Visser, C.C.; Chu, Q. Quadrotor gray-box model identification from high-speed flight data. J. Aircr. 2019, 56, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashayev, A.; Sabziev, E. Refinement of the parameters of a mathematical model of quadcopter dynamics. Sci. J. Silesian Univ. Technol. Ser. Transp. 2020, 109, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Litt, J. Online Model Parameter Estimation of Jet Engine Degradation for Autonomous Propulsion Control. NASA/ARL, Technical Manual TM2003-212608. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference and Exhibit, Austin, TX, USA, 11–14 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Amezquita-Brooks, L.; Hernandez-Alcantara, D.; Santana-Delgado, C.; Covarrubias-Fabela, R.; Garcia-Salazar, O.; Ramirez-Mendoza, A.M. Improved model for micro-UAV propulsion systems: Characterization and applications. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2019, 56, 2174–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ljung, L.; Benveniste, A.; Delyon, B.; Glorennec, P.-Y.; Hjalmarsson, H.; Juditsky, A. Nonlinear black-box modeling in system identification: A unified overview. Automatica 1995, 31, 1691–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Qian, J.; Zhu, Z.; Bao, X.; Helwa, M.K.; Schoellig, A.P. Deep neural networks for improved, impromptu trajectory tracking of quadrotors. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 12–15 December 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 5183–5189. [Google Scholar]

- Tutunji, T.A. Parametric system identification using neural networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 47, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.C.; Li, Y. Evolutionary system identification in the time domain. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 1997, 211, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Flores, A.; Tellez-Belkotosky, P.A.; Ollervides-Vazquez, E.J.; Castillo, P.; Reyes-Osorio, L.A.; Garcia-Salazar, O. A design modification of a quadrotor frame based on fused deposition modeling. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Chania-Crete, Greece, 4–7 June 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 800–806. [Google Scholar]

- Green, C.R.; McDonald, R.A. Modeling and test of the efficiency of electronic speed controllers for brushless dc motors. In Proceedings of the 15th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference, Dallas, TX, USA, 22–26 June 2015; p. 3191. [Google Scholar]

- Yedavalli, R.K. Flight Dynamics and Control of Aero and Space Vehicles; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chapra, S.C.; Canale, R.P. Numerical Methods for Engineers; Mcgraw-Hill Education-Europe: Columbus, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Karsoliya, S. Approximating number of hidden layer neurons in multiple hidden layer BPNN architecture. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2012, 3, 714–717. [Google Scholar]

- Adil, M.; Ullah, R.; Noor, S.; Gohar, N. Effect of number of neurons and layers in an artificial neural network for generalized concrete mix design. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 8355–8363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolak, A.B. A novel comparative investigation of the effect of the number of neurons on the predictive performance of the artificial neural network: An experimental study on the thermal conductivity of ZrO2 nanofluid. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 18944–18956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, S.; Athaiya, A. Activation functions in neural networks. Towards Data Sci. 2017, 6, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szandała, T. Review and comparison of commonly used activation functions for deep neural networks. In Bio-Inspired Neurocomputing; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Parhi, R.; Nowak, R.D. The role of neural network activation functions. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2020, 27, 1779–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Du, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lan, H.; Liu, S.; Li, L.; Guo, Q.; Chen, T.; Chen, Y. Cambricon-X: An accelerator for sparse neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO), Taipei, Taiwan, 15–19 October 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Afaq, S.; Rao, S. Significance of epochs on training a neural network. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 485–488. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).