2. Models & Methods

Short-term natural gas load forecasting (NGLF) is inherently a high-dimensional, large-data prediction problem. Both the volume of influencing factors and the length of the historical data series often exceed those of other forecasting types. This high dimensionality and large data volume not only impose a significant burden on predictive models but also amplify the overall complexity of the forecasting task [

55]. Moreover, analyzing the impact of each factor individually would necessitate the design of numerous cross-combination scenarios, each requiring separate simulation. This approach unequivocally increases the analytical workload, while the practical utility of the method and the applicability of its results are severely limited.

Due to stochastic influences, historical NGLF data often contains numerous outliers. These outliers can interfere with the underlying patterns of the load data, disrupt the similarity of gas loads within the same period, and consequently degrade the model’s forecasting accuracy [

56,

57,

58]. Addressing these outliers is therefore an essential preprocessing step.

To address the dual challenges of complex high-dimensional data processing and the presence of anomalous data, this study adopts an improved Principal Component Analysis algorithm (PCCA) for dimensionality reduction and key factor analysis. Concurrently, an improved Singular Spectrum Analysis algorithm (ISSA) is employed for data cleansing. Finally, these components are combined with a GRU neural network to form a hybrid forecasting model that integrates data analysis, preprocessing, and prediction. Overall, the proposed model utilizes a combination of improved, lightweight preprocessing algorithms and a lightweight predictive model to achieve efficient, rapid, and accurate short-term NGLF on low-computation platforms.

2.1. Improvement of the PCA Algorithm (PCCA)

2.1.1. Shortcomings of the PCA Algorithm in Gas Load Data Processing

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) algorithm can transform several correlated variables into an equal number of uncorrelated components. By extracting the principal components from the data to replace the original dataset, it achieves the goal of reducing dataset dimensionality and eliminating redundant information. Utilizing the PCA algorithm to reduce the dimensionality of the original dataset retains the main data components while simultaneously reducing the input data dimensionality for the predictive model [

59]. The PCA algorithm primarily involves three processes: mean centering and standardization, eigendecomposition, and reconstruction.

Although the PCA algorithm can extract the principal components of the original variables, its reconstruction process relies on ranking and filtering components based solely on the magnitude of their eigenvalues. This causes the linear relationship between each component and the target variable (natural gas load) to be disregarded, rendering the standard PCA process unsuitable for direct application in short-term NGLF [

50].

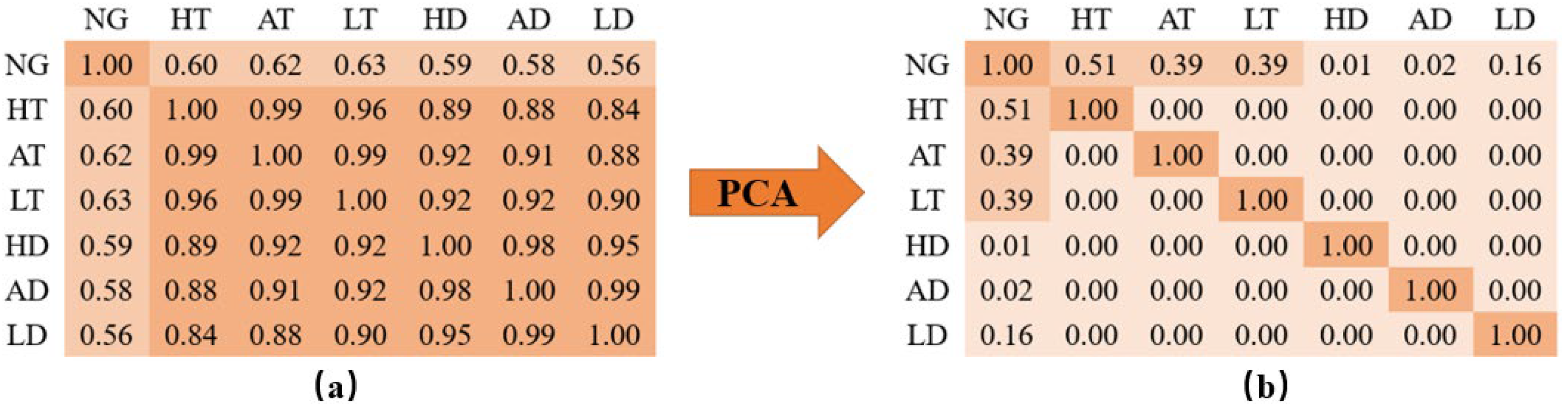

The experimental data used is the gas load data from a large city in Northern China (identical to that used in subsequent forecasting experiments), with results shown in

Figure 1. (In the figures, NG represents daily natural gas load, LT represents daily low temperature, AT represents daily average temperature, HT represents daily high temperature, LD represents daily low dew point, AD represents daily average dew point, and HD represents daily high dew point).

Figure 1a shows the correlation heatmap of the original data, where temperature factors and dew point factors have a high correlation with natural gas load (all > 0.50). Concurrently, the correlation among these factors themselves is high (all > 0.80). In

Figure 1b, which shows the principal components obtained by standard PCA, all components are uncorrelated variables, effectively reducing variable correlation and redundant input.

However, a critical issue is observed: the 4th component obtained by PCA has a correlation of only 0.01 with NG, whereas the 6th component has a correlation of 0.16. Although the eigenvalue of the 6th component is lower than that of the 4th, its correlation with NG is significantly higher. Therefore, if components are selected based on eigenvalue magnitude alone, it is highly probable that important components with high target correlation will be discarded in favor of components with low target correlation.

2.1.2. Introducing Correlation Analysis Correction to the PCA Algorithm

To address this issue, we propose an algorithm for processing influencing factors that is specifically tailored for short-term natural gas load forecasting. This method builds upon the traditional PCA algorithm by considering the correlation between each component and the natural gas load. It modifies the reconstruction process of PCA by introducing a correlation analysis step, thereby forming a new influencing factor processing algorithm, which we name Principal Component Correlation Analysis (PCCA).

The PCCA algorithm also comprises three stages: mean-centering and standardization, eigendecomposition, and reconstruction. The first two stages are identical to those of the standard PCA algorithm. However, in the reconstruction stage, after the eigenvector matrix U is obtained from eigendecomposition, a principal component matrix is formed. This matrix contains

n principal components, where each component can be represented as

for

i = 1, 2, …,

n. Let the daily natural gas load series be denoted by

. The direct correlation between each component and the daily load can then be calculated using Equations (1) and (2):

where

is the covariance between component

Li and the load

Y;

is the mean of

Li;

is the mean of

Y;

is the variance of

Li;

D(

Y) is the variance of

Y;

is the correlation coefficient between component

Li and the load

Y, with its absolute value ranging from [0, 1], where 1 indicates perfect linear correlation and 0 indicates no linear correlation.

Subsequently, the correlation coefficients of all components are arranged in descending order, and the contribution rate of each component is calculated as shown in Equation (3):

where

pi is the contribution of component

Li.

A contribution threshold, SP, is set within the range of 0% to 100%. We then select the top r components (where r < n) such that their cumulative contribution exceeds SP. Finally, the components corresponding to these selected contributions are extracted to serve as the input parameters for the forecasting model.

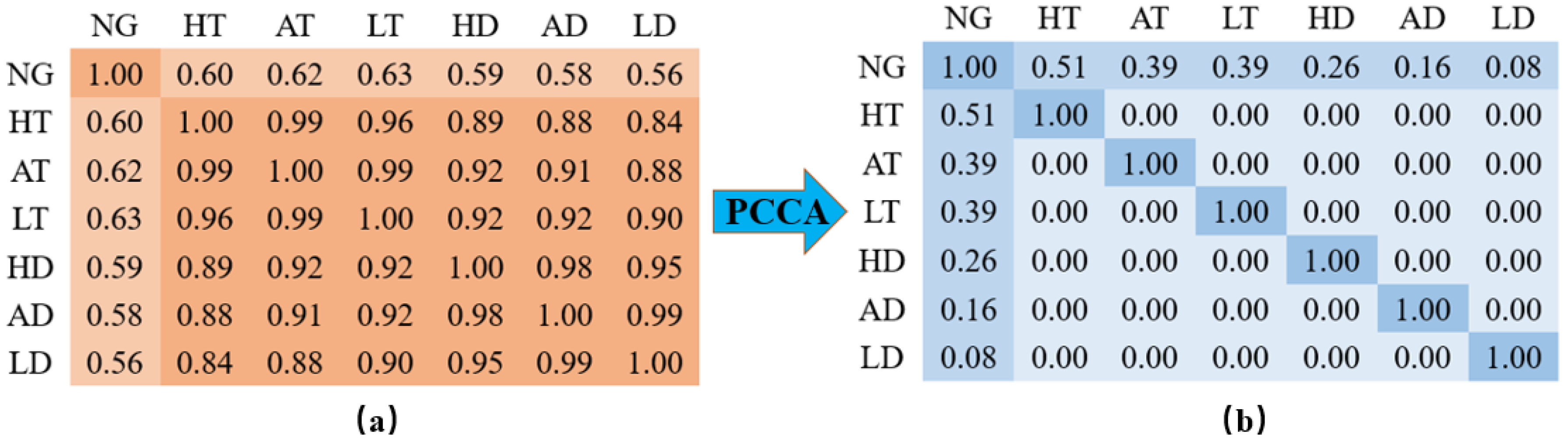

The results after processing with the PCCA algorithm are shown in

Figure 2. Compared to the original PCA algorithm, the correlation of the new PCCA-derived features with the NG load is strictly monotonically decreasing, which provides a clear and meaningful ranking of information. Both methods perform consistently on the first three principal components. However, a significant divergence occurs at the 4th and 5th components: PCCA retains substantial correlation with NG (0.26 and 0.16, respectively), whereas the original PCA components lost nearly all relevant correlation (0.01 and 0.02). This demonstrates that the improved PCCA algorithm successfully retains more critical features relevant to the target variable.

2.2. Improvement of the SSA Algorithm (ISSA)

2.2.1. The Problem of Sub-Sequence Feature Loss in SSA

The Singular Spectrum Analysis (SSA) algorithm constructs a time-lag (trajectory) matrix from a time series of N samples based on a given embedding dimension. It then performs eigendecomposition (or Singular Value Decomposition, SVD) on this matrix to obtain eigenvalues and eigenvectors. The SSA algorithm can be broadly divided into two stages: Decomposition and Reconstruction. The Decomposition stage includes Embedding and Eigendecomposition; the Reconstruction stage includes Grouping, Diagonal Averaging, and Selection.

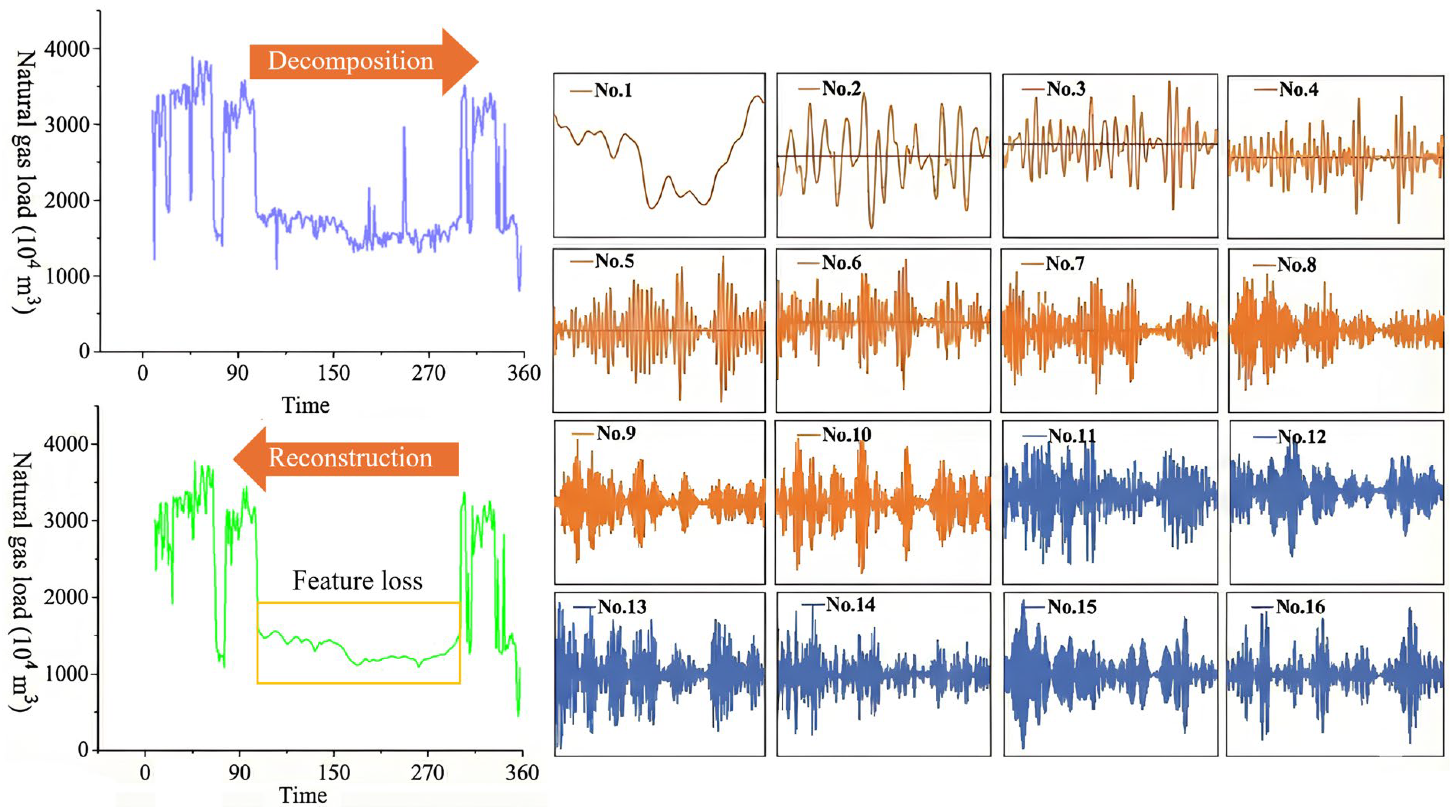

Figure 3 illustrates the denoising results of applying the original SSA algorithm to the same natural gas load data from the large city in Northern China (as used in subsequent experiments). The results clearly demonstrate a significant problem of data feature loss.

Based on these results, it is evident that the standard SSA algorithm, during time series reconstruction, selects sub-sequences solely based on their corresponding eigenvalues while disregarding the intrinsic characteristics of the sub-sequences themselves. This leads to unsatisfactory denoising performance, particularly when a large amount of noise is present [

60,

61]. When the SSA threshold is set too low, the resulting fitted curve is overly smooth, leading to low fidelity (underfitting); conversely, when the threshold is set too high, the curve fits the data closely but is prone to overfitting [

51,

52].

2.2.2. Introducing Skewness Logarithm and Kurtosis Logarithm into SSA

To enhance the denoising capability of the Singular Spectrum Analysis (SSA) algorithm for natural gas load data characterized by non-Gaussian distributions and high-skewness “spikes,” and to prevent the occurrence of overfitting or underfitting, this study proposes the Improved Singular Spectrum Analysis (ISSA) algorithm. Building upon the original algorithmic structure, ISSA introduces log-skewness and log-kurtosis to modify the selection process of the standard SSA. The structural framework of ISSA remains identical to that of SSA; the distinction lies in the selection methodology. Specifically, a log-skewness function,

s, and a log-kurtosis function,

k, are established to measure the probability distribution of the subsequences. The objective is to identify and eliminate high-frequency subsequences that contain significant noise components. The detailed process is described in Equations (4) through (7):

where

sp is the logarithmic skewness of the sub-series

Zp;

kp is the logarithmic kurtosis of the sub-series

Zp;

Skew(

Zp) is the skewness coefficient of the sub-series

Zp;

Kurt(

Zp) is the kurtosis coefficient of the sub-series

Zp;

μp is the mean of the sub-series

Zp;

σp is the variance of the sub-series

Zp;

st is the skewness threshold;

kt is the kurtosis threshold;

Y is the reconstructed time series.

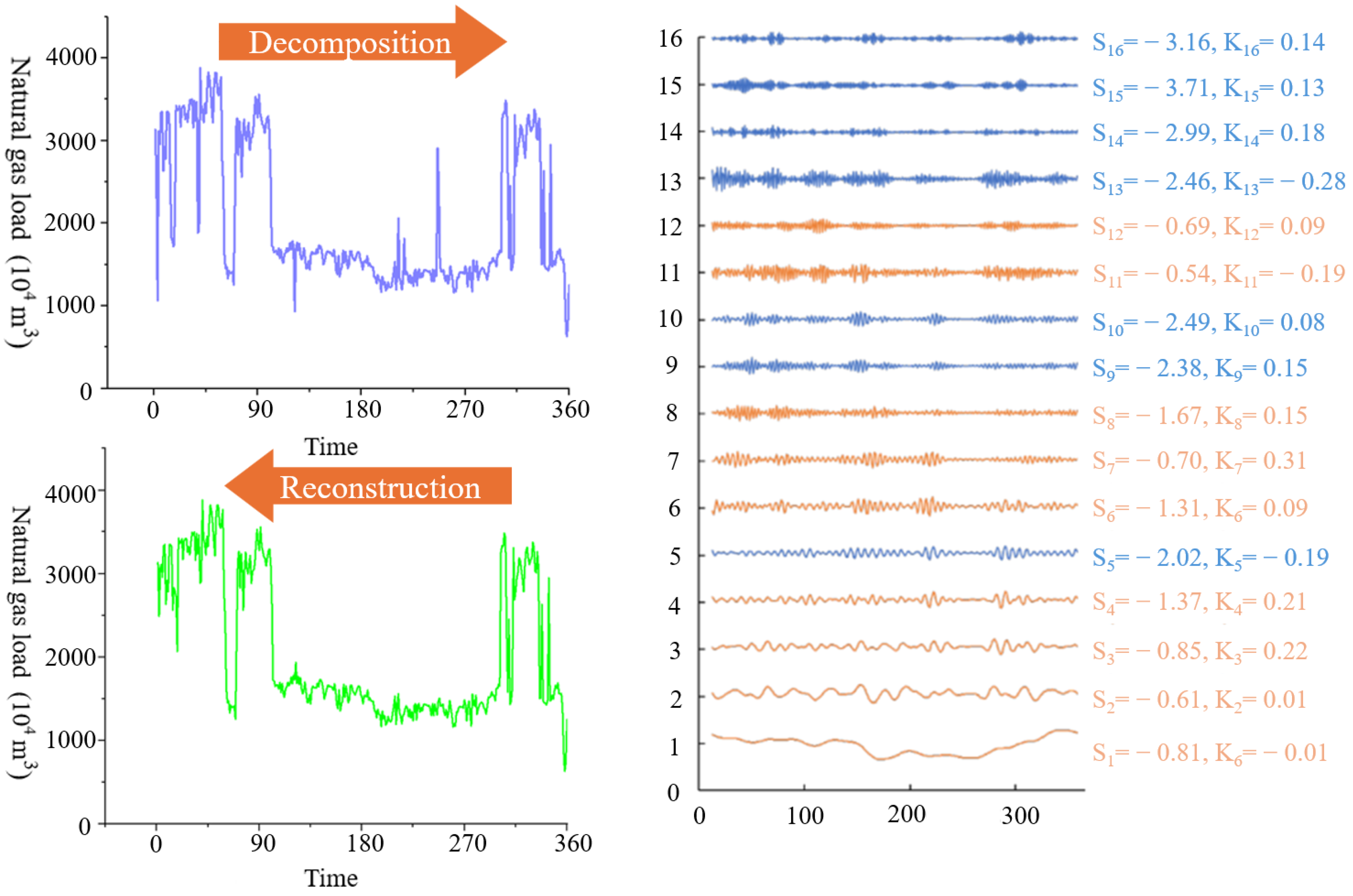

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the original data is first decomposed into one low-frequency sub-series and several high-frequency sub-series. Then, the logarithmic skewness

s and logarithmic kurtosis

k are calculated for each sub-series, and the results are compared against the predefined thresholds

st and

kt. The rationale is that the smaller the values of

sp and

kp, the more closely the sub-series

Zp approximates a Gaussian distribution. When these values fall below their respective thresholds, the component is identified as noise and is discarded from the dataset. Finally, the sub-series with s and k values greater than the given thresholds are summed to form the reconstructed time series.

As seen visually in the results from

Figure 4, the improved ISSA algorithm achieves a significantly better denoising effect on the experimental data. It also markedly remedies the problem of data feature loss, as the key oscillation characteristics of the natural gas load in the central region are fully preserved.

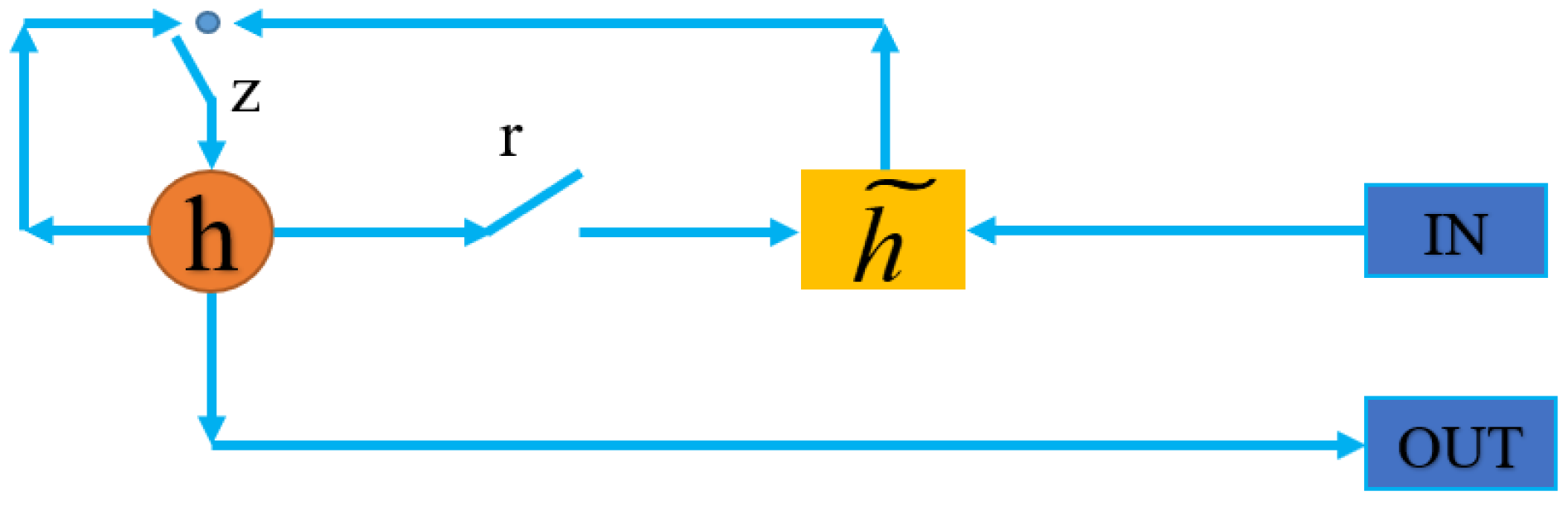

2.3. GRU Neural Network

The Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) neural network is characterized by its fast convergence speed and simple structure [

62]. As shown in

Figure 5, the hidden state

h represents the degree to which the hidden state from the previous time step is combined with the candidate hidden state of the current time step, a process controlled by the update gate. The candidate hidden state

represents whether the information from the previous time step’s hidden state (which contains historical time series information) is needed for the current time step’s candidate hidden state, as controlled by the reset gate.

The output of the GRU, the calculation formula for

yt is

. The parameters to be learned are the weight matrices W, Wr, Wz and Wo. The relationship between these weights is shown in Equation (8):

The specific training steps for these weight parameters are as follows:

- (1)

Calculate the input to the output layer , and the final output .

- (2)

Define the loss function at time step t as . The total loss for a single sample is then given by .

- (3)

Compute the partial derivatives of the total loss function.

- (4)

Calculate the relevant weight gradients to update Wr, Wz, W and Wo.

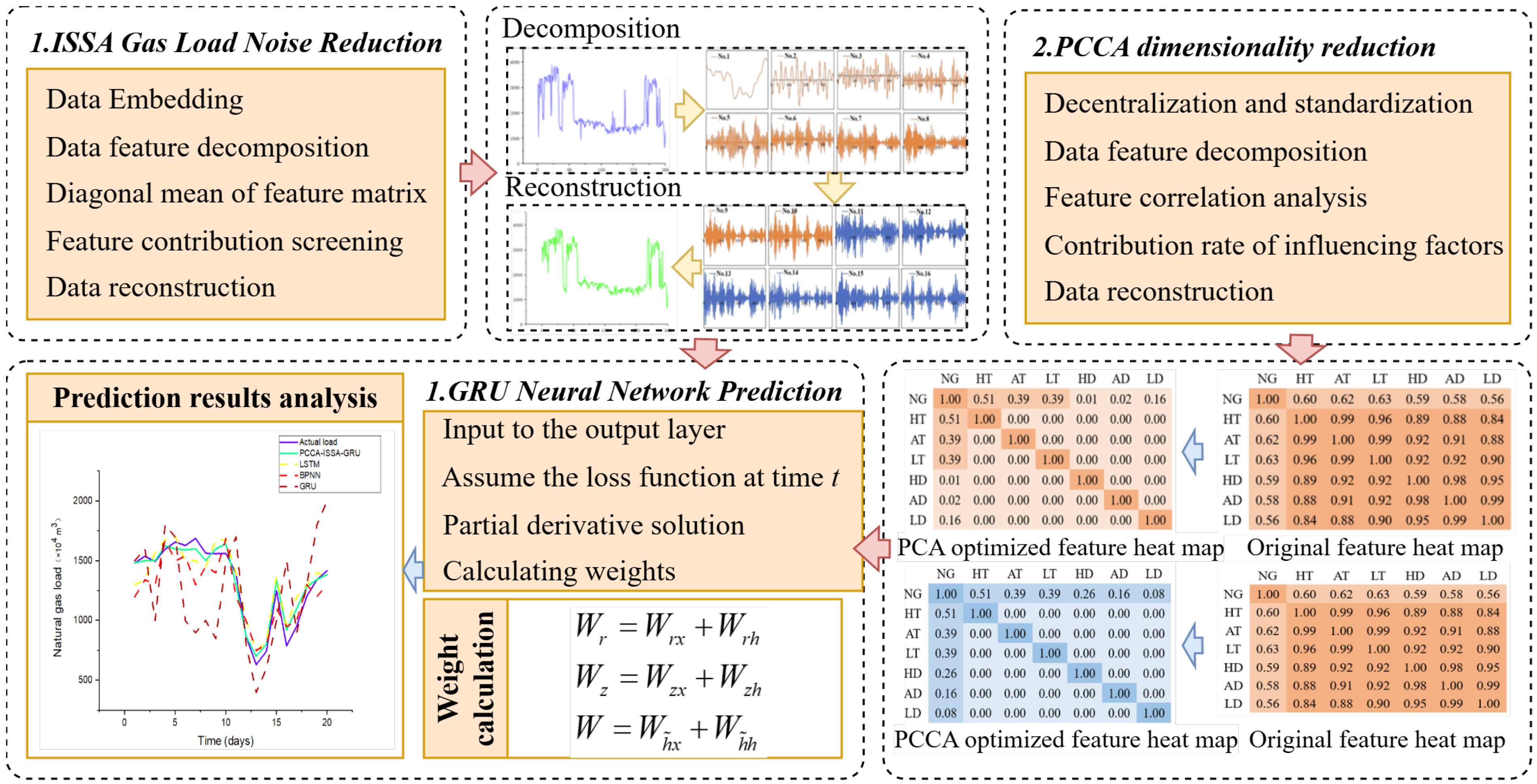

2.4. Construction of the PCCA-ISSA-GRU Model

By integrating the improved dimensionality reduction and denoising methods with the GRU network, we establish a novel hybrid model for short-term gas load forecasting, named the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model. The specific workflow of this model is illustrated in

Figure 6.

This model framework processes the data from two distinct perspectives: denoising the load data and reducing the dimensionality of the influencing factors. This comprehensive preprocessing aims to achieve higher forecasting accuracy. Specifically, the ISSA algorithm is applied to denoise the historical gas load data. Concurrently, the PCCA algorithm is used to perform a Pearson correlation analysis and extract the key features from the influencing factors after dimensionality reduction. Finally, the denoised and dimension-reduced data are fed into the GRU model to ensure the precision of the gas load forecast.

To ensure model reproducibility and strictly avoid “Data Leakage,” all experiments in this study adhere to a rigorous data partitioning and preprocessing workflow. Data leakage refers to the unintentional use of information from the test set during model training, a common pitfall in time series decomposition or normalization.

The PCCA-ISSA-GRU network processing workflow ensures that information from the test set remains “unseen” until model training is complete:

- (1)

Data Splitting: First, the entire dataset is strictly divided into a training set and a test set. For example, in the 20-day prediction experiment, the dataset is split into the first 345 days (training set) and the subsequent 20 days (test set).

- (2)

Fit: The parameters of the preprocessing algorithms are fitted only on the training set. Specifically,* The transformation matrix and correlation contribution rates for the PCCA algorithm are calculated based only on the 345-day training data.* The statistical thresholds (St and Kt) used by the ISSA algorithm for denoising are determined by analyzing only the historical load series of the 345-day training set.

- (3)

Transform: Using the parameters fixed in step (2) (i.e., the PCCA transformation matrix and ISSA thresholds), the transformation is applied separately to both the training set and the test set.

- (4)

Model Training: Finally, the preprocessed training set data is fed into the GRU network for training. The trained model is then used to predict the test set, which has undergone the same transformation as in step (3). This “Train-Fit, Test-Transform” workflow [

45] ensures the fairness of the forecasting process and the validity of the results.

To ensure the transparency and reproducibility of the experiment,

Table 2 details the key hyperparameters for the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model and the baseline models. Parameters for other baseline models were obtained using recommended values from the literature, combined with fine-tuning.

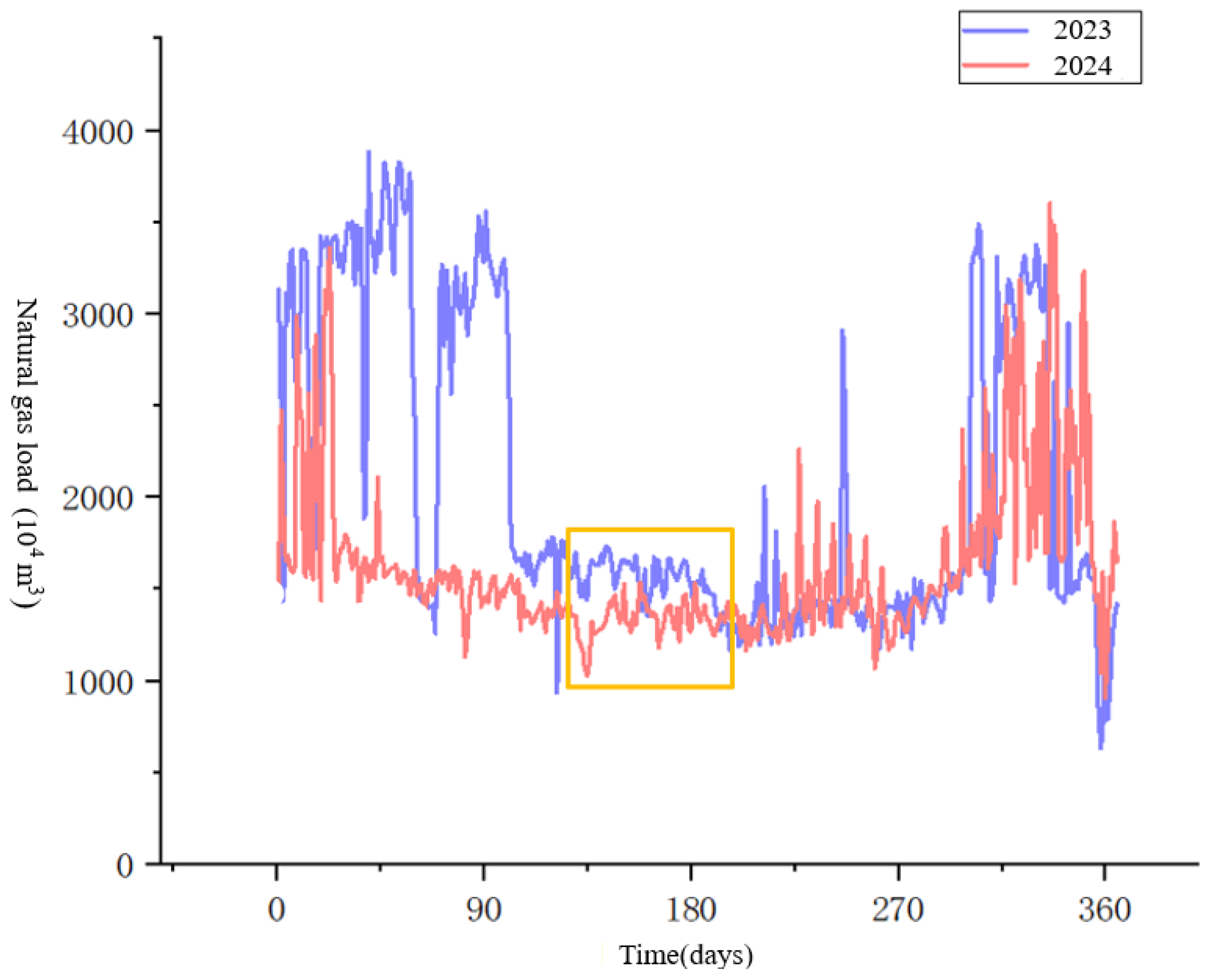

3. Load Characteristics and Influencing Factor Analysis

3.1. Load Feature Analysis

To validate the accuracy of the novel hybrid algorithm in short-term natural gas load forecasting (NGLF), this study conducts an empirical analysis based on actual gas load data from a large city in Northern China (using the same data as in the PCA and SSA algorithm improvement sections). Accurate load forecasting is the core link in ensuring the reliability of gas supply, optimizing pipeline network planning, and managing daily dispatch. It provides critical technical support for the decision-making of urban gas management departments.

The gas load data for this city exhibits complex, composite characteristics:

- (1)

First: due to the regular patterns of social production and residential life, the load demonstrates significant periodicity on daily, weekly, and annual scales.

- (2)

Second: in the absence of special events, the data changes smoothly, showing continuity.

At the same time, the presence of numerous users with diverse consumption habits, coupled with interference from various external factors such as weather and holidays, imparts strong randomicity and non-linearity to the load fluctuations, which poses a significant challenge for precise forecasting.

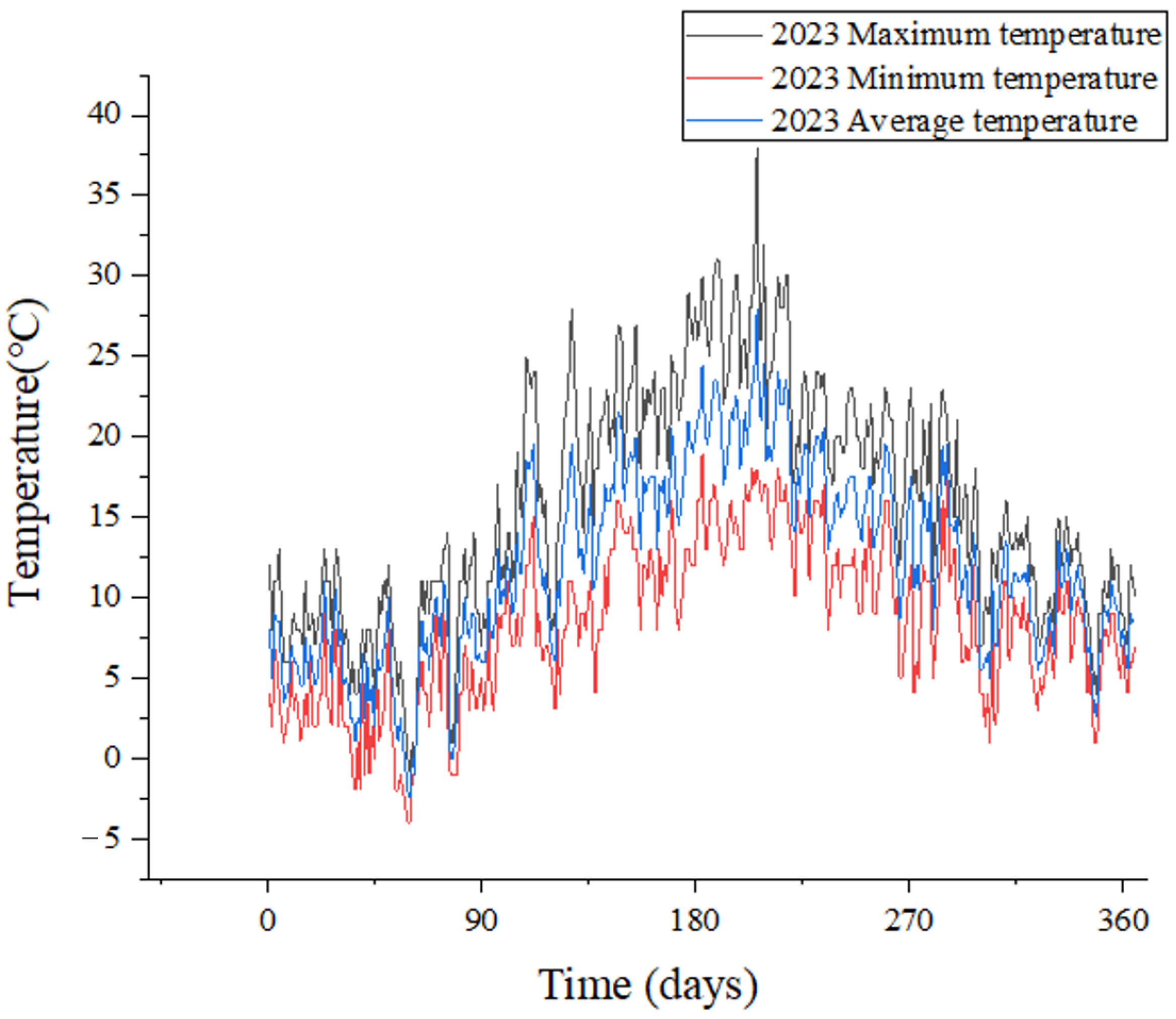

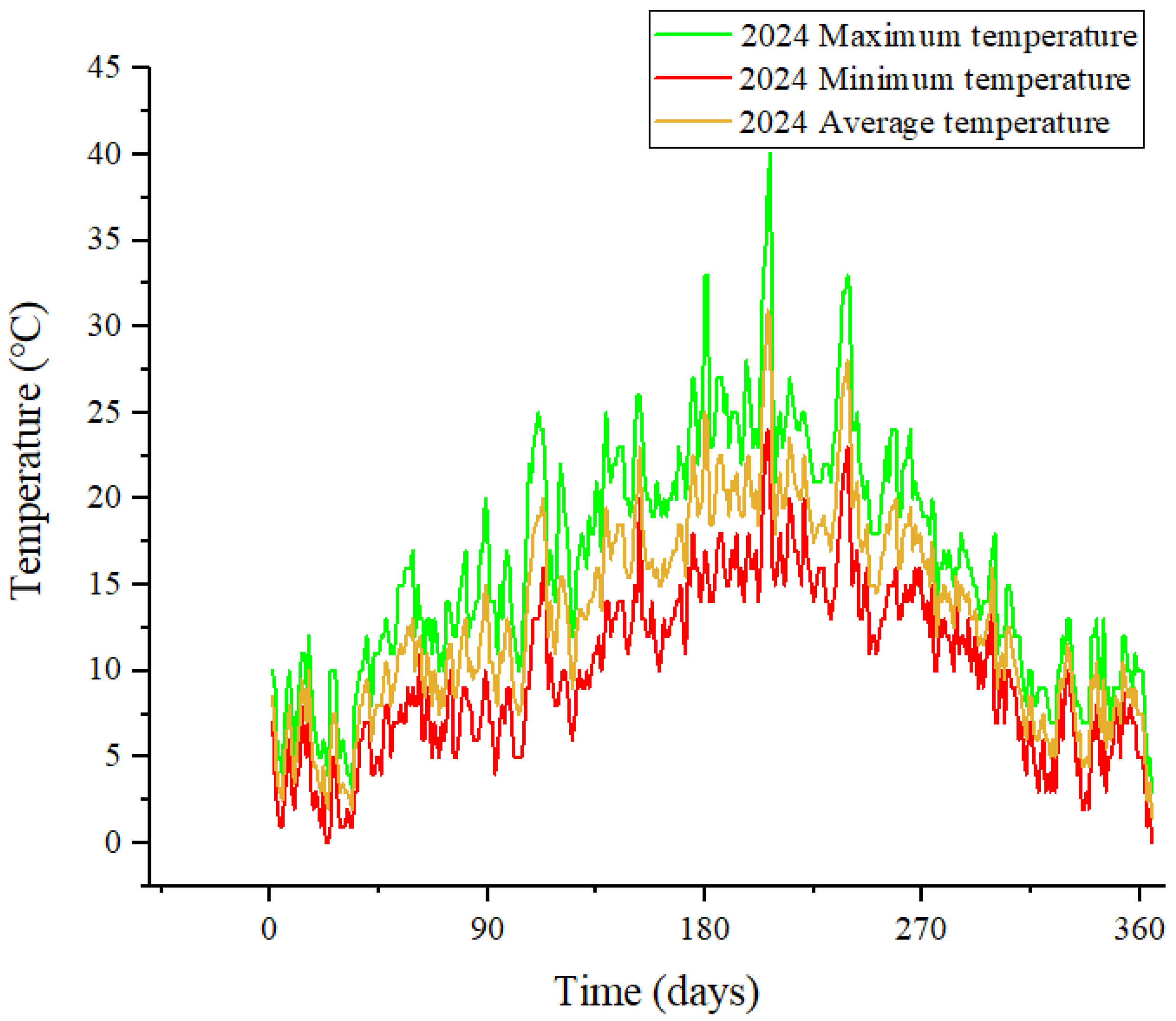

From a macroscopic trend perspective, the city’s daily load data presents a distinct seasonal pattern of being “high in winter and low in summer,” but it is also characterized by intense short-term volatility and data anomalies. As shown in

Figure 7, the load curves for 2023 and 2024 intuitively verify this set of complex characteristics.

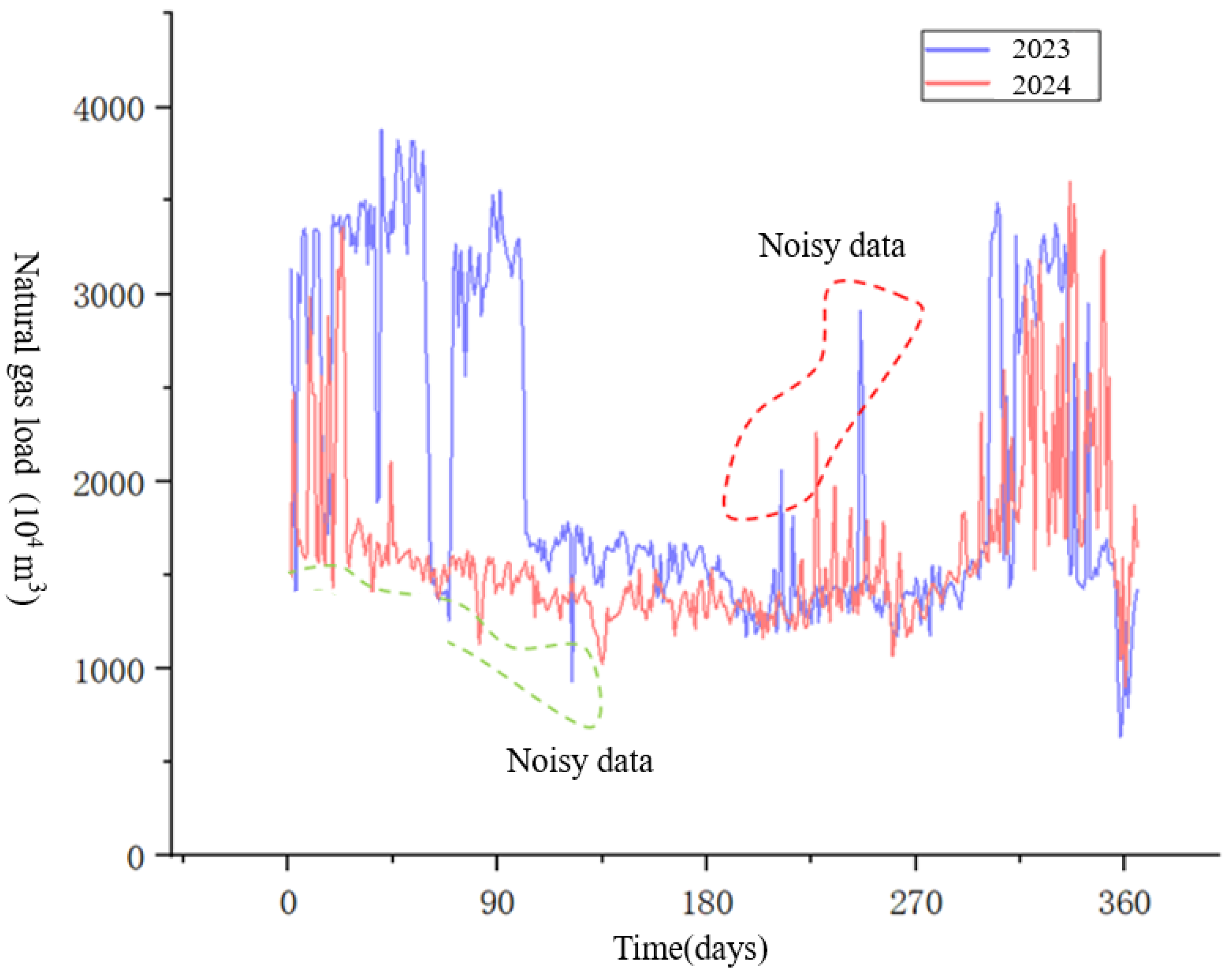

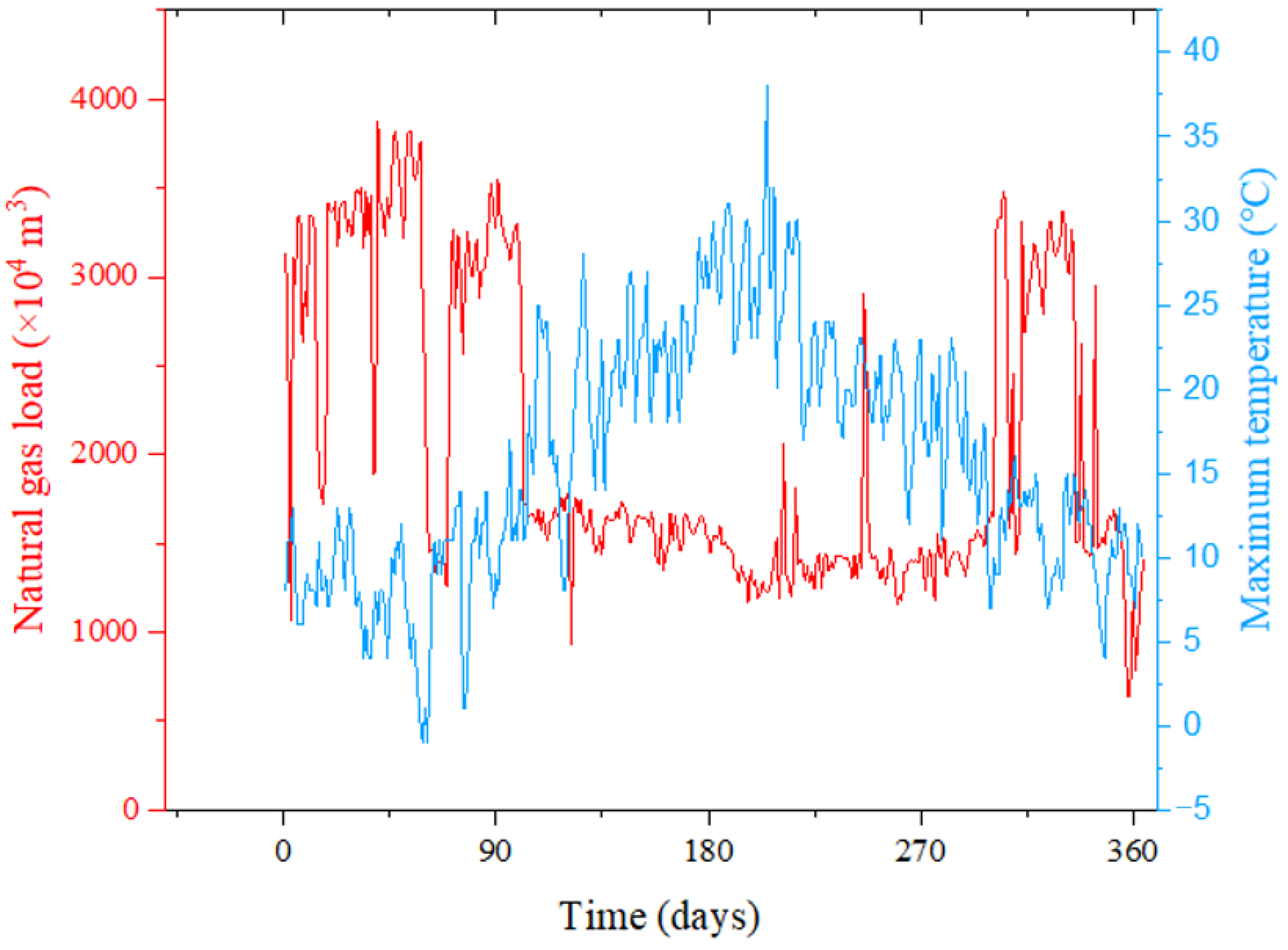

Noisy data, also known as outlier data in natural gas load forecasting (although the two are often distinct), refers to data that deviates from the true value due to factors such as metering instrument errors, operator recording errors, and statistical errors. Typically, it mainly refers to the high-frequency components in the raw data. The deviation of noisy data from the true value is difficult to identify by directly observing the load trend curve. Load data contains many outliers that differ significantly from the true value. As shown in

Figure 8, the presence of these outliers severely affects prediction accuracy and reduces the performance of the prediction model. Therefore, how to handle outlier data is a primary issue to be addressed in short-term natural gas load forecasting. Improper handling will affect the training effect of the prediction model and increase the difficulty of prediction. Numerous studies have shown that using data denoising algorithms to reduce noise in the raw data can effectively improve prediction accuracy and reduce short-term load forecasting errors.

Thus, to obtain higher prediction accuracy, it is necessary to adopt effective denoising methods to mitigate the adverse effects of noise on NGLF. The improved ISSA algorithm can accurately identify data noise while preserving the original data characteristics, providing a reliable data source for subsequent prediction (the denoising results using ISSA are shown in

Section 2.2).

3.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors

In short-term natural gas load forecasting (NGLF), it is necessary to analyze a large number of continuous daily load-influencing factors. Therefore, when considering these factors, one must account for not only their correlation with the gas load but also their feasibility (i.e., data availability and reliability for a predictive context). Based on these considerations, the primary factors ultimately identified for daily NGLF include weather conditions, date types, wind levels, and holiday factors. After analyzing the relevant factors using the improved PCCA algorithm, the following two key factor groups were identified (a detailed correlation analysis is provided in

Section 2.1):

- (1)

Meteorological Factors

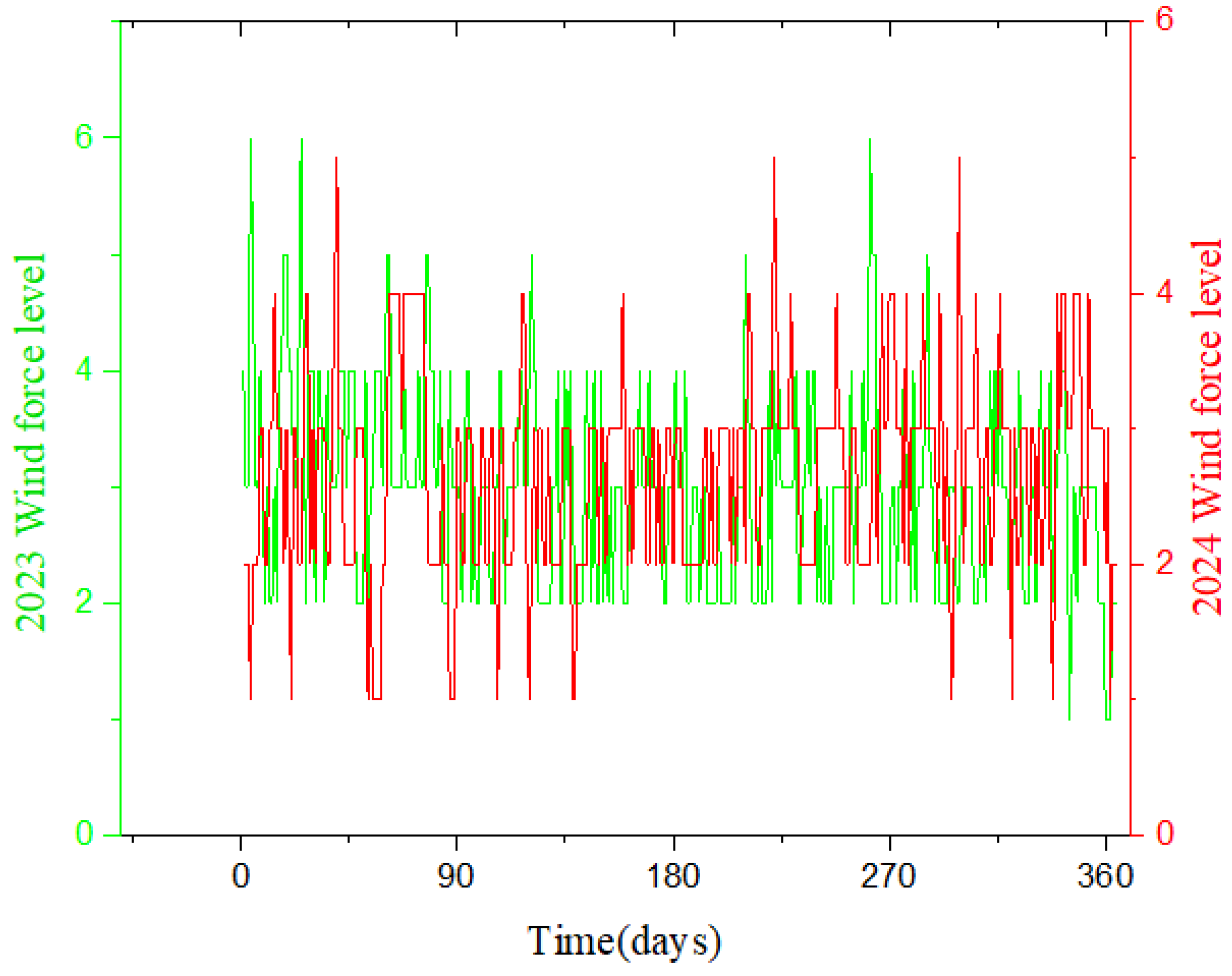

The analysis from the improved PCCA algorithm confirms that meteorological factors are the primary drivers influencing the natural gas load in the studied city. In different seasons, gas consumption is inextricably linked to changes in factors such as temperature and wind level. Consequently, meteorological factors are the foremost choice for short-term NGLF. Specific factors include daily maximum temperature, daily minimum temperature, daily average temperature, and wind level. This paper collected and organized relevant temperature and wind data for a specific city in China for the years 2023 and 2024, as shown in

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

Among these, the maximum temperature is the single most significant factor influencing the load variation in this city.

Figure 12 illustrates the correlation between load and maximum temperature. The horizontal and vertical axes represent time, temperature, and gas load value, respectively. As can be observed from the figure, the lower the temperature, the higher the gas load. As the temperature rises, the load value decreases, demonstrating a clear negative correlation between temperature and load.

- (2)

Date and Price Factors

Date factors include the year, month, and day. These factors not only convey date information but also indirectly reflect holiday information, which is correlated with user gas consumption patterns. For example, during public holidays, many people choose to travel, leading to a significant drop in gas consumption, whereas consumption on weekdays remains relatively stable.

Regarding price factors, it was determined that gas price should not be used as an input variable for short-term NGLF. This decision is based on two facts: first, in the short term, the price of natural gas generally does not undergo drastic changes. Second, the gas price for a future (forecasted) period is often unknown. If a predicted gas price were used as an input variable to forecast the future gas load, the uncertainty inherent in the price prediction could itself lead to deviations in the final load forecast. Therefore, gas price is excluded as an input variable for the short-term model.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

To ensure model reproducibility, a sensitivity analysis was conducted on the most critical hyperparameters of the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model: (1) the number of GRU hidden units; and (2) the PCCA cumulative contribution threshold (SP) and the ISSA skewness threshold (St).

Based on the experimental data samples, the analysis was performed under a 20-day forecast horizon. The impact of the number of GRU hidden units on MAPE was evaluated using a controlled variable approach, where one parameter was varied while others remained constant. The results are presented in

Table 3.

As shown in

Table 3, different numbers of hidden units were tested in the hyperparameter tuning experiments to evaluate their impact on prediction performance. The results indicate that the model achieved optimal performance with 64 hidden units, yielding the lowest MAPE of 6.09%. Insufficient units may lead to underfitting, whereas excessive units tend to induce overfitting.

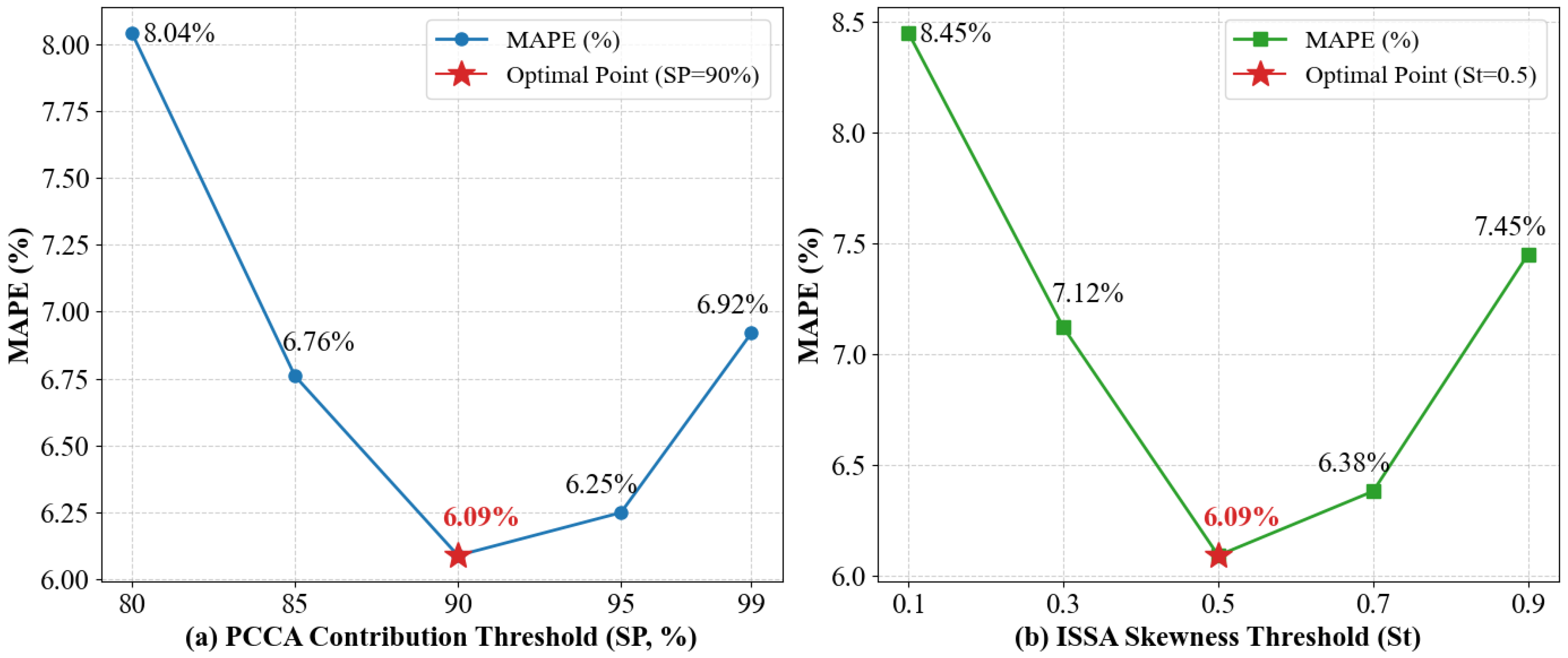

In the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model, the PCCA cumulative contribution rate threshold (

SP) and the ISSA skewness threshold (

St) are crucial hyperparameters determining feature quality and signal purity. To validate the rationale of the selected parameters (

SP = 90,

St = 0.5) and investigate the impact of parameter variations on prediction performance, a dual-parameter sensitivity analysis was conducted. Using the controlled variable approach, the model’s MAPE was tested under different parameter configurations, as illustrated in

Figure 13.

As shown in

Figure 13a, the selection of the PCCA threshold

SP requires a trade-off between “information integrity” and “feature redundancy”:

- (1)

Underfitting Region (SP < 90%): When SP is low (e.g., 80%), the model discards critical features that are non-linearly correlated with the load, resulting in a high MAPE (8.04%).

- (2)

Overfitting Region (SP > 90%): When SP is excessively high (e.g., 99%), the model incorporates numerous tail features containing noise. This increases computational complexity and interferes with prediction, causing the error to rise to 6.92%.

- (3)

Optimal Point (SP = 90%): At this level, the model retains the vast majority of valid information while eliminating redundancy, achieving the lowest error (6.09%).

As shown in

Figure 13b, the ISSA threshold

St determines the “intensity” of signal denoising, exhibiting a similar “decrease-then-increase” trend:

- (1)

Over-smoothing (St < 0.5): When the threshold is set too low (e.g., 0.1), the screening criteria of the ISSA algorithm become overly strict. Consequently, many normal high-frequency signals containing sudden load changes are erroneously identified as noise and removed. This “over-cleaning” destroys the authentic structure of the raw data, keeping MAPE at a high level (8.45%).

- (2)

Residual Noise (St > 0.5): When the threshold is set too high (e.g., 0.9), the screening criteria become too lenient. The algorithm fails to effectively identify non-Gaussian random noise, allowing significant interference signals to remain in the input sequence. This reduces the learning efficiency of the GRU, causing MAPE to rise to 7.45%.

- (3)

Optimal Balance (St = 0.5): When St is set to 0.5, the model accurately distinguishes between valid high-frequency fluctuations and random noise, maximizing the restoration of the true load variation patterns and achieving optimal prediction accuracy.

The results indicate that the model’s performance remains relatively stable within the ranges of 64 to 128 for GRU hidden units, 90% to 95% for the PCCA threshold, and 0.5 to 0.7 for the ISSA threshold. This demonstrates that the PCCA-ISSA-GRU framework possesses excellent robustness and does not rely on extreme “fine-tuning” of hyperparameters.

4.2. Comparative Analysis with Classic Single Models

To comprehensively validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, this section selects three representative types of standalone models as baselines: BPNN, LSTM, and GRU. The rationale for selecting these models is as follows:

- (1)

Foundational ANN Baseline: The Back-Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) was chosen as the most fundamental neural network model. Its simple structure represents an early application of neural networks in the forecasting domain. Comparing against it serves to establish a performance “low-bar” baseline, used to measure the necessity of more complex models designed for time-series data.

- (2)

“Gold-Standard” Sequential Baselines: Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) are the current “gold standard” and established best practices in the field of time-series forecasting. Both models are specifically designed to capture long-term temporal dependencies in data via sophisticated gating mechanisms, which is crucial for load forecasting. Comparing PCCA-ISSA-GRU against these two classic recurrent neural networks is a necessary step to evaluate whether its performance reaches the state-of-the-art (SOTA) level in the domain.

- (3)

“Ablation” Validation of Core Components: Critically, the core of the model proposed in this study is the GRU. Therefore, comparing the PCCA-ISSA-GRU (i.e., “PCCA feature selection + ISSA data cleansing + GRU prediction”) with an original, unprocessed GRU model constitutes a key part of an ablation study. The purpose of this comparison is to clearly isolate and quantify the actual performance improvement brought about by our innovative PCCA-ISSA preprocessing framework, rather than attributing the success solely to the GRU architecture itself. This directly validates the effectiveness and contribution of this study’s primary innovation (the front-end preprocessing).

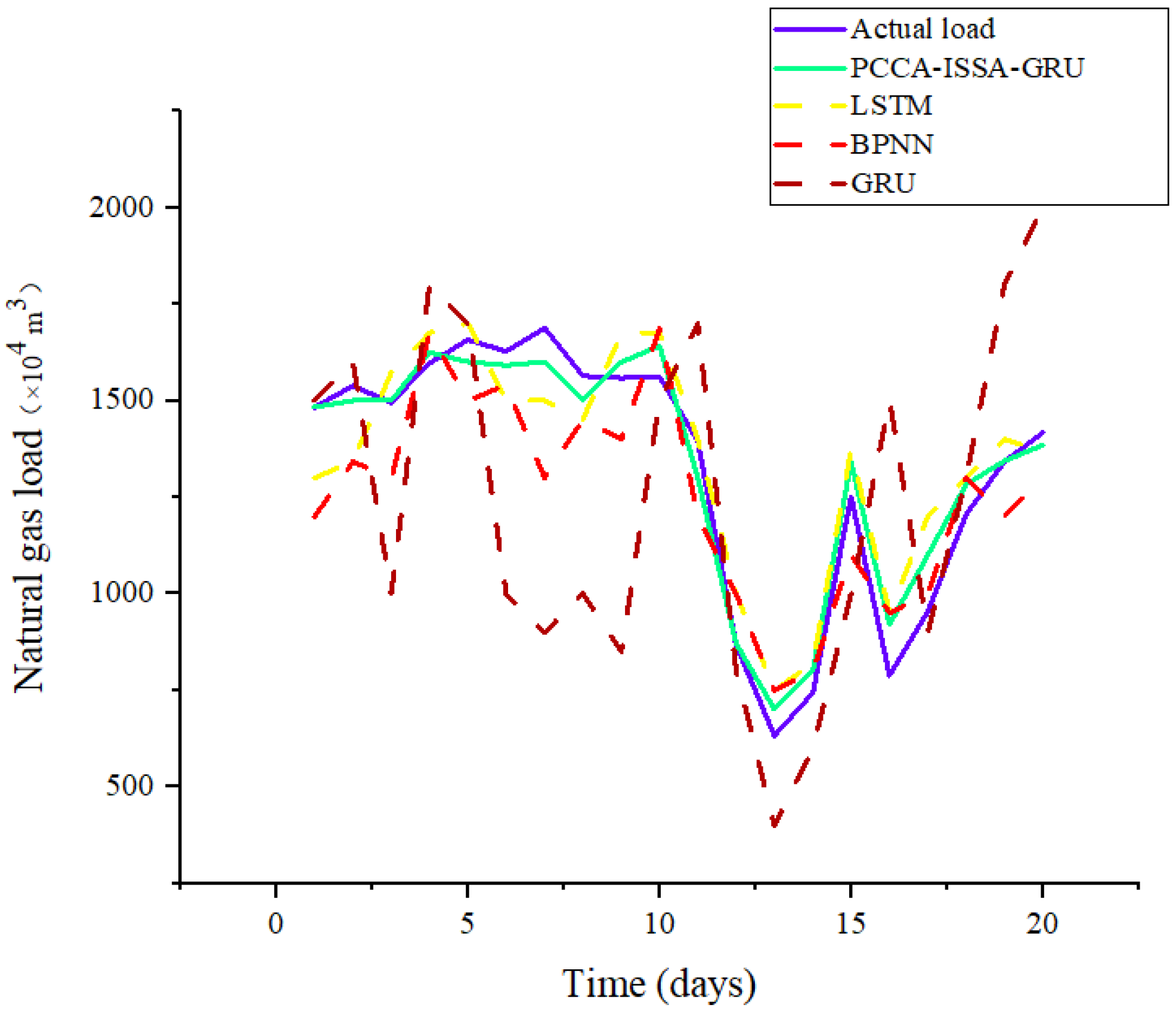

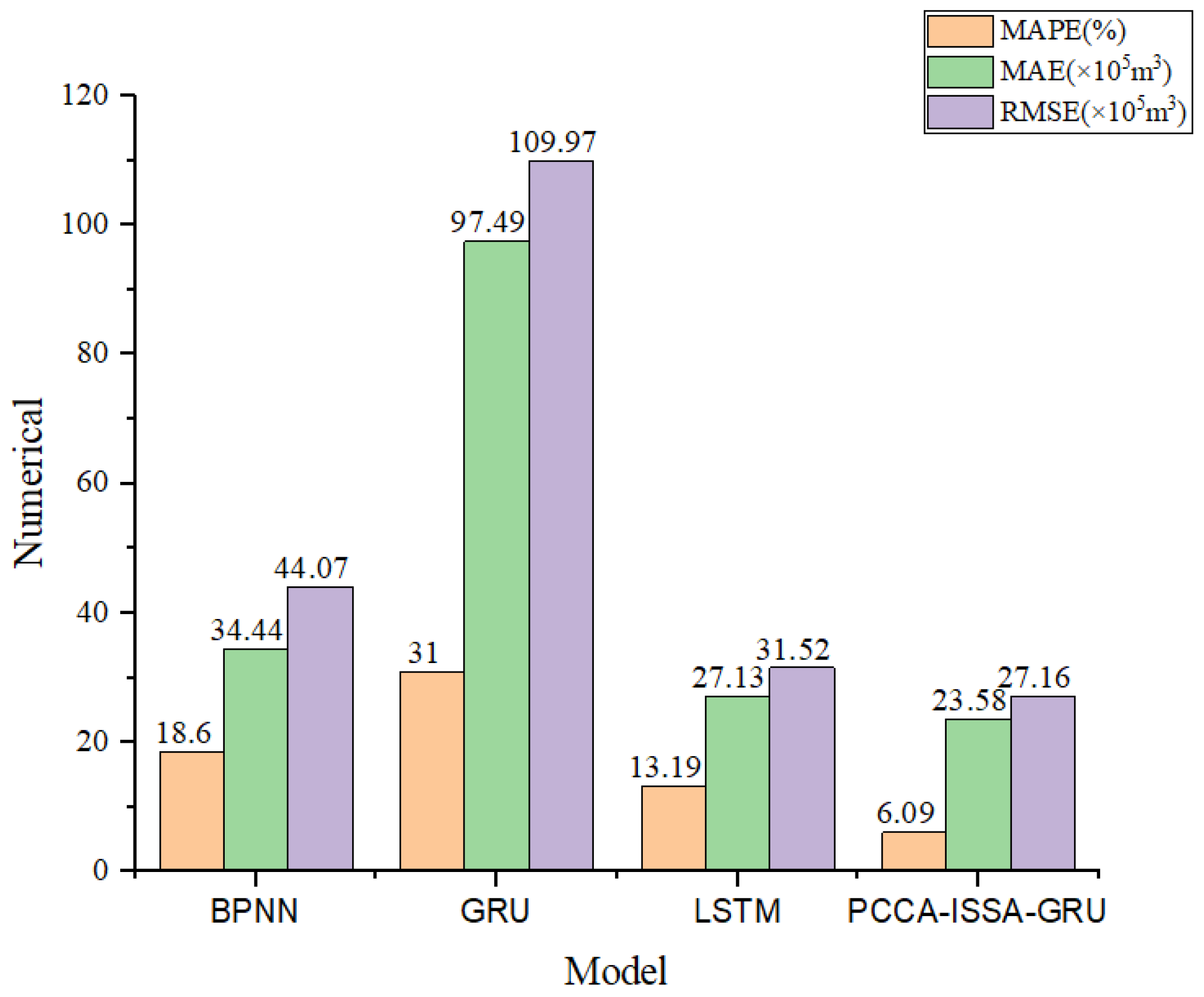

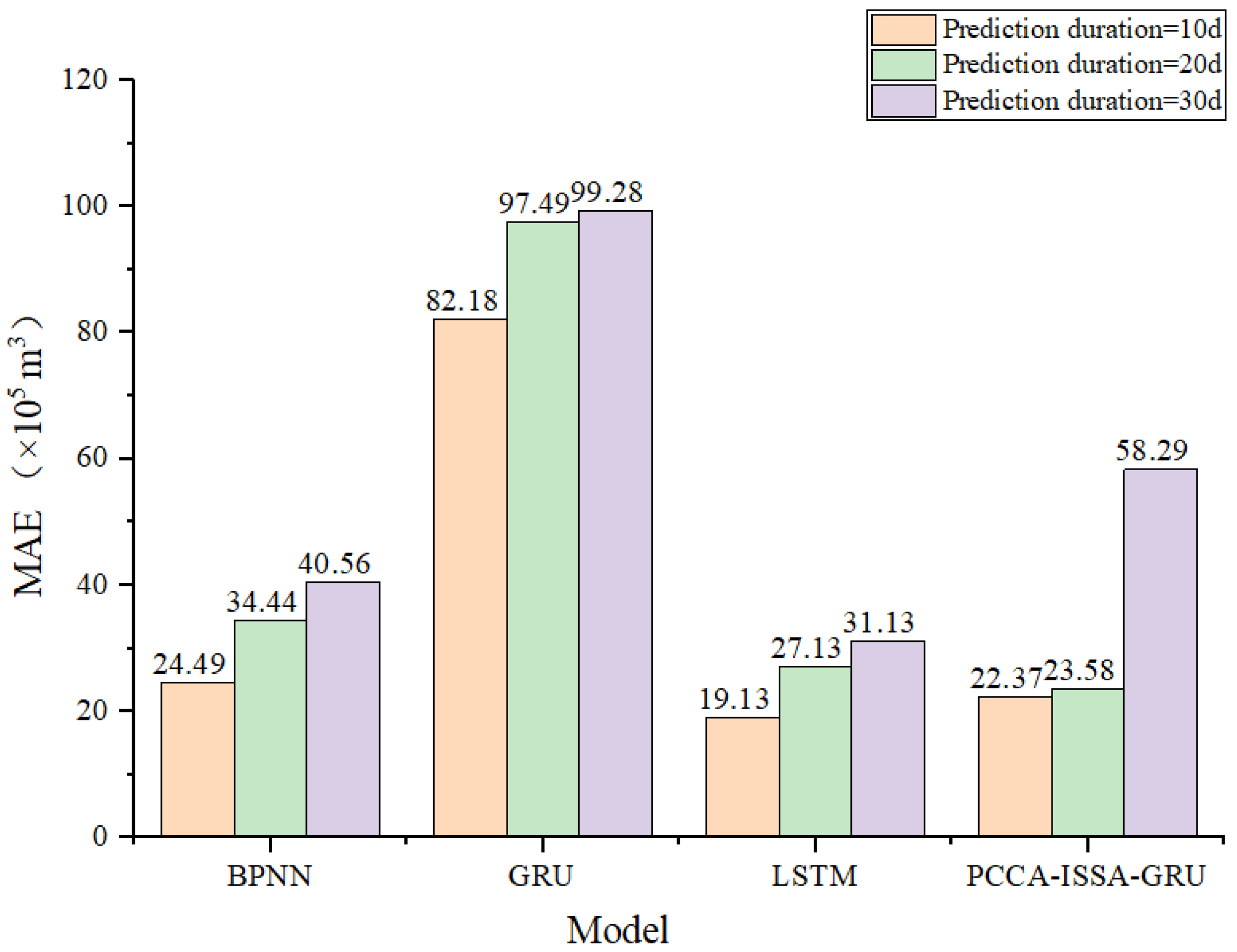

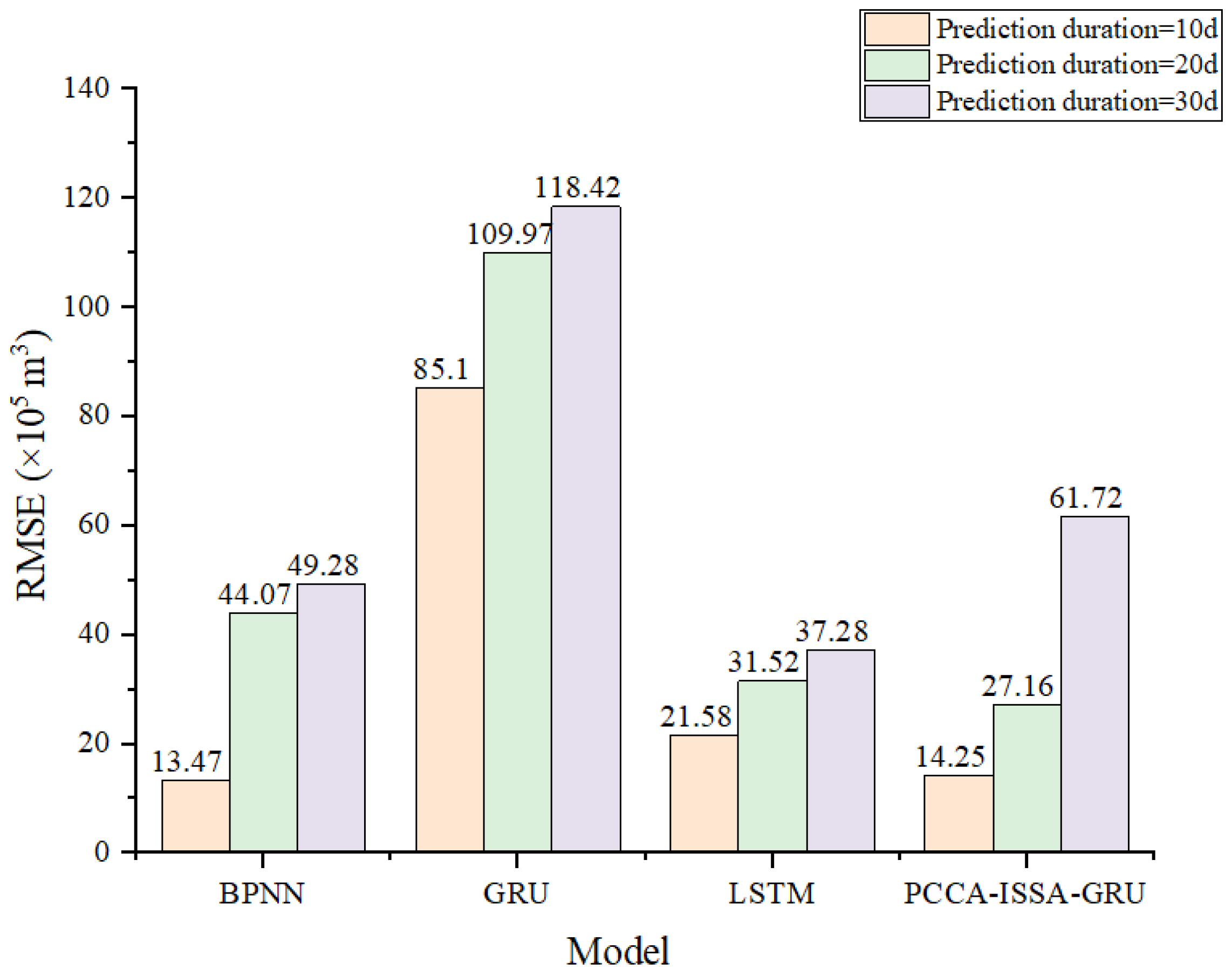

After analyzing the load data, the experiment was set with a forecast horizon of 20 days. The hybrid algorithm (PCCA-ISSA-GRU) applied the improved PCCA algorithm for dimensionality reduction in influencing factors and the improved ISSA algorithm for data cleansing to forecast the load data. A comparative analysis was conducted against the prediction results of the LSTM, BPNN, and GRU models. The comparison results are shown in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15.

As indicated by the prediction results, in the short-term forecasting scenario, the prediction accuracy of the PCCA-ISSA-GRU hybrid model is significantly higher than that of the traditional models, exhibiting the lowest MAPE, MAE, and RMSE.

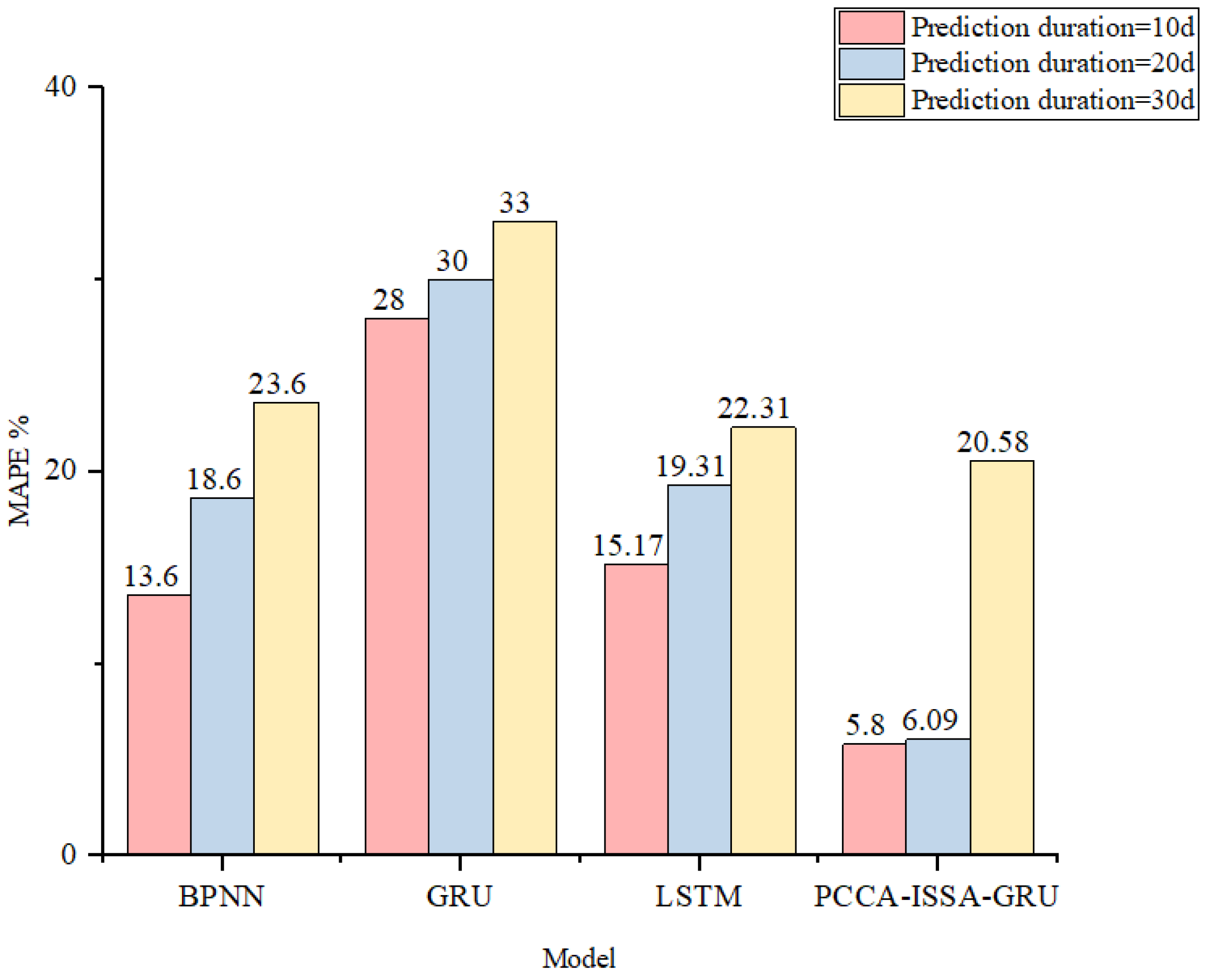

On this basis, to further verify the adaptability of the hybrid model for short-term NGLF, this paper designed three experimental groups using the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model, based on different forecast horizons. Each group has a training and test set of varying lengths, as shown in

Table 4. The error results for the four models are shown in

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18.

As can be seen from

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18, when the forecast horizon is 20 days, the three error metrics for the hybrid forecasting model are likewise lower than those of the other three existing models. Furthermore, the same trend holds: the shorter the prediction horizon, the higher the accuracy.

Additionally, when extending the forecast horizon from 20 days to 30 days, the MAPE value for the PCCA-ISSA-GRU hybrid model triples (a 3-fold increase) compared to its 20-day MAPE. In contrast, the MAPE increases for the BPNN, GRU, and LSTM models were 26.88%, 10.00%, and 15.54%, respectively. The results show that all three baseline models and the PCCA-ISSA-GRU hybrid model experience a surge in error. This is related to the construction of the neural networks; whether it is the BP error back-propagation mechanism or the LSTM/GRU long-term memory mechanism, the iterative (step-by-step) forecasting process inevitably leads to error accumulation, causing the prediction results to gradually deviate from the true values. Therefore, the proposed hybrid model is more suitable for short-term load forecasting analysis within a 20-day horizon.

After the PCCA feature selection, the daily maximum temperature was selected as the characteristic variable for the predictive model, rather than the daily average temperature. To verify the accuracy of this selection, three sets of experiments were conducted using the daily average temperature as the characteristic variable, while all other feature variables remained unchanged.

Table 5 displays the error values of the prediction results.

It is evident from

Table 5 that for this particular city, the correlation between maximum temperature and users’ natural gas consumption is stronger than that between average temperature and consumption. This indicates that when applying this hybrid forecasting model, the maximum temperature should be considered a key factor. These experimental results indirectly validate the accuracy of the PCCA method for selecting the features of influencing factors.

4.3. Comparison with Classic Hybrid Algorithms and SOTA Algorithms

To further situate the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model within a broader academic context, this section introduces two more advanced predictive models for comparison: ARIMA-ANN and Informer. The rationale for their selection is as follows:

- (1)

Classic Hybrid Model Baseline: The ARIMA-ANN model was selected as a representative of “classic hybrid forecasting models.” Before deep learning (especially Transformer) architectures became dominant, hybrid paradigms combining statistical models like ARIMA with ANNs were a powerful and widely adopted technique for handling complex time-series forecasting (addressing both linear and non-linear components). The comparison against ARIMA-ANN aims to demonstrate that the framework proposed in this study holds a performance advantage over these mature hybrid forecasting paradigms.

- (2)

State-of-the-Art (SOTA) Baseline: The Informer model was selected as the SOTA baseline. As a highly academically influential Transformer-based architecture designed specifically for Long-Series Time-series Forecasting (LSTF), the Informer represents the cutting-edge technology in this field. A benchmark against a SOTA model is necessary to answer two key questions: (a) In terms of prediction accuracy, can the model proposed in this study compete with (or “be comparable to”) the most advanced and structurally complex architectures, such as the Informer? (b) Within the specific medium-to-short-term “tactical planning window” (e.g., 10–20 days), can this study’s “advanced domain-specific preprocessing + lightweight model” strategy prove to be a more cost-effective and practical solution than a complex SOTA model?

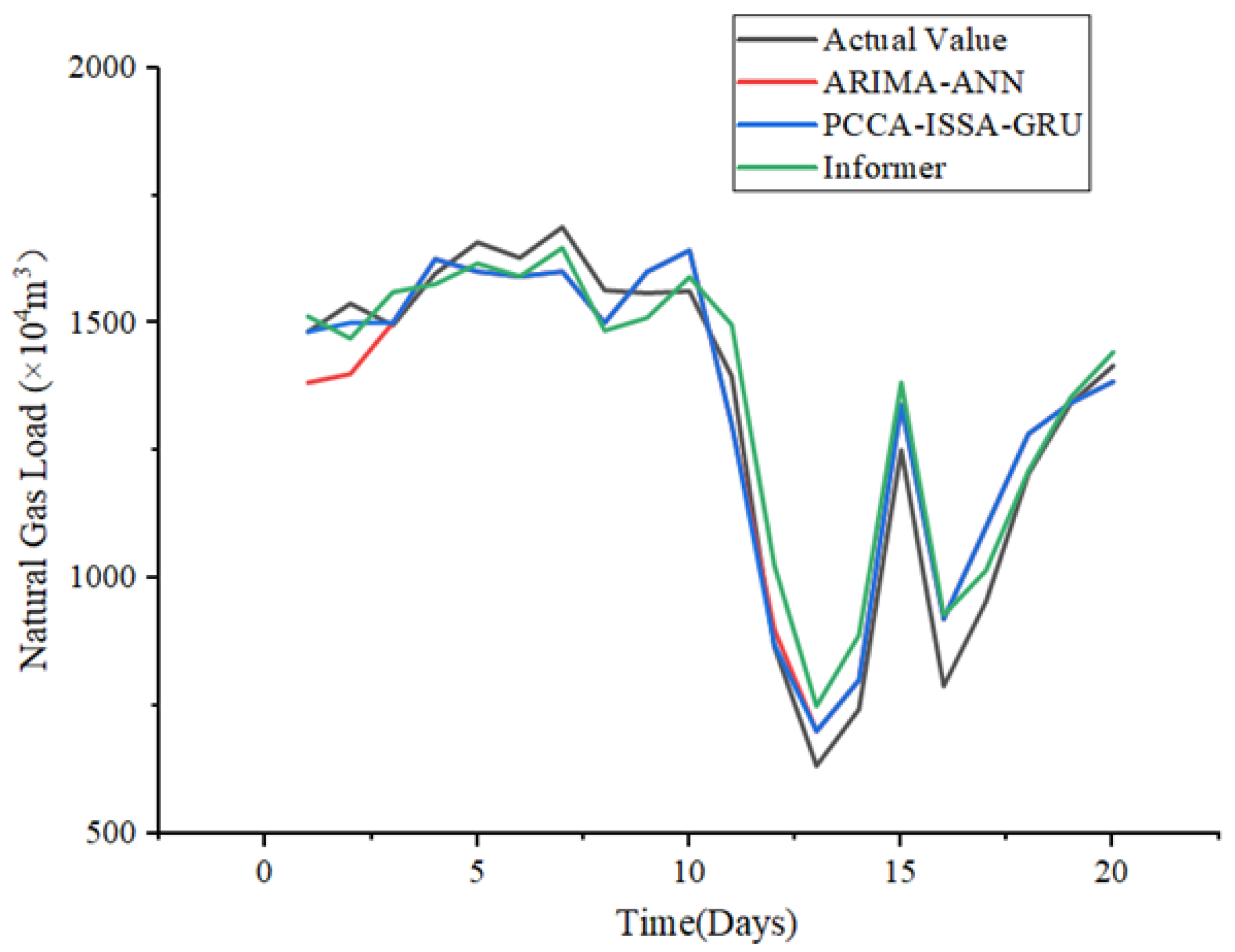

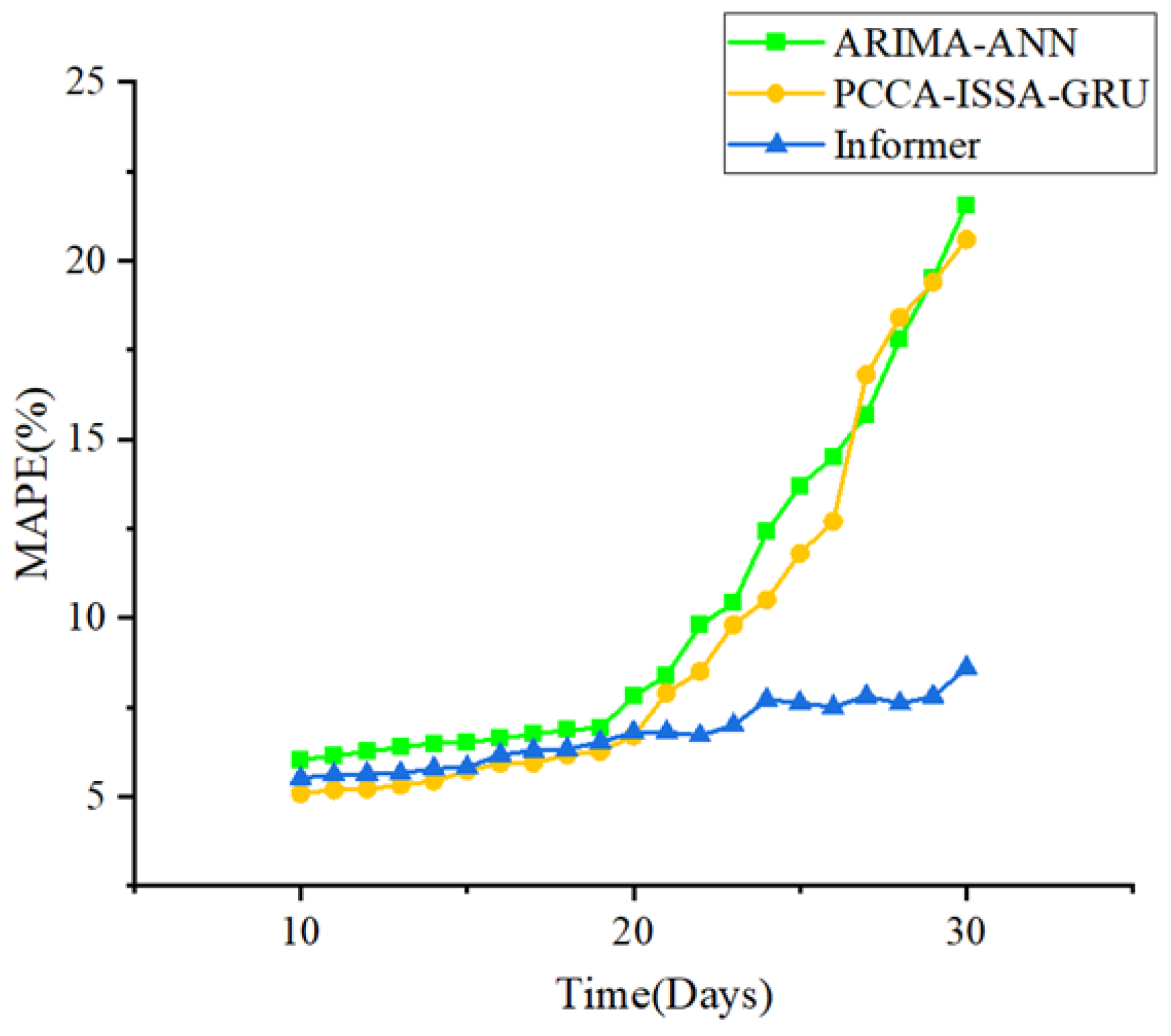

Taking the period from 12–31 December 2024, as an example, the predictive comparison results are shown in

Figure 19, and the MAPE values are shown in

Figure 20.

Through the comparative analysis of

Figure 18 and

Figure 19, it can be concluded that the classic ARIMA-ANN hybrid model exhibits some volatility in the initial forecasting stage. The novel PCCA-ISSA-GRU hybrid forecasting model’s results are more stable, whereas the Informer model shows an advantage in the later forecasting stage. Overall, the PCCA-ISSA-GRU hybrid model achieves ideal prediction results in both the early and late stages.

An analysis of the MAPE results reveals that the new hybrid model is more suitable for urban NGLF. Within the 10-day and 20-day “tactical planning window,” the MAPE metrics for PCCA-ISSA-GRU (5.80% and 6.09%) are both slightly superior to those of the Informer model (6.25% and 6.51%).

When the forecast horizon exceeds 20 days, the error of the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model increases significantly. This is attributed to the auto-regressive mechanism of its GRU core, which is prone to error accumulation in long-sequence forecasting, leading to a decline in accuracy in the later stages. In contrast, the Informer model, as the SOTA baseline, maintained high stability in its MAPE throughout the entire period. This is because it employs a Transformer-based direct multi-step prediction strategy, which circumvents the problem of error accumulation and demonstrates its architectural advantage in LSTF tasks.

During the comparative experiments, it was found that although the Informer, as a SOTA model, exhibited powerful predictive capabilities, it is a model with a complex structure, numerous hyperparameters, and requires substantial computational resources for training. In contrast, the PCCA-ISSA-GRU framework is based on a more lightweight GRU, and its core advantage lies in the efficient, targeted front-end preprocessing (PCCA and ISSA), rather than a complex model architecture.

For the NGLF “tactical planning window” (10–20 days), PCCA-ISSA-GRU achieves a level of accuracy comparable to or even slightly better than Informer, but it possesses significant advantages in terms of model simplicity, tuning difficulty, and training cost. This proves that the “advanced domain-specific preprocessing + lightweight model” strategy is a more cost-effective and practical solution than complex SOTA models in this specific application scenario.

4.4. Significance Testing and Effectiveness Analysis of Core Modules

To rigorously evaluate whether the predictive advantage of the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model over other benchmark models is statistically significant, we employed the Diebold–Mariano (DM) test. While metrics such as MAPE and MAE only indicate “average performance,” the DM test assesses whether the difference in prediction error sequences between two models is statistically meaningful. The DM test is a standard method in time series forecasting as it correctly handles the serially correlated errors inherent in multi-step forecasting.

Using the Mean Squared Error (MSE) of the 20-day forecast (h = 20) as the loss function, we tested whether PCCA-ISSA-GRU (Model A) is significantly superior to other benchmark models (Model B). The null hypothesis (H0) of the DM test posits that the two models have equal predictive accuracy. If the p-value is less than 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that Model A is significantly superior to Model B.

As shown in

Table 6, the

p-values for the comparison between the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model and all traditional benchmarks (BPNN, GRU, LSTM, ARIMA-ANN) are well below 0.01, indicating that its advantage is highly statistically significant. More importantly, in the comparison with the SOTA model Informer, the

p-value is 0.0285 (<0.05). This statistically confirms that although the lead of PCCA-ISSA-GRU in terms of MAPE for the 10–20-day forecast is relatively small (see

Table 6), this advantage is not accidental but statistically significant.

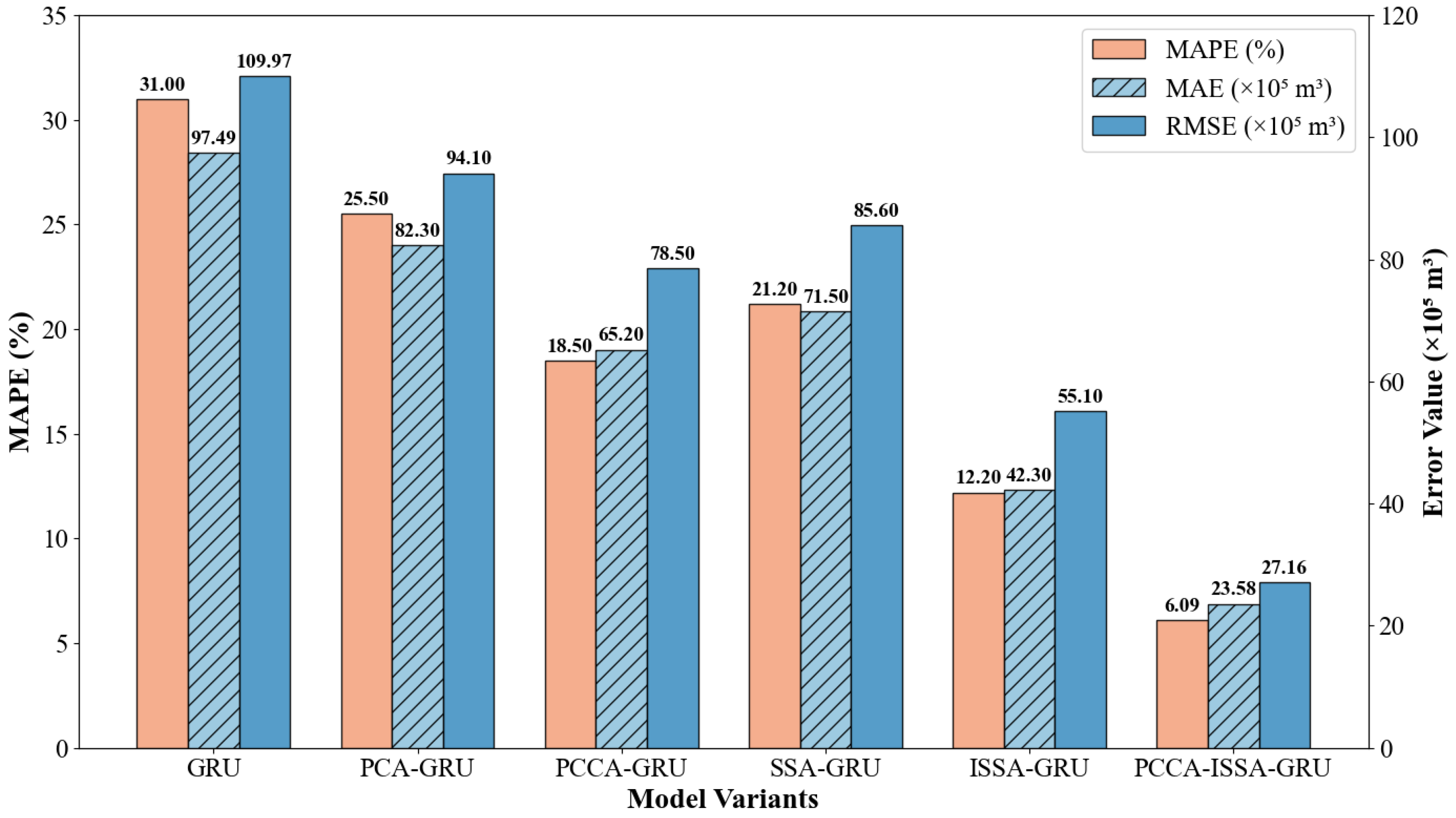

To deeply investigate the specific contributions of the proposed PCCA feature extraction module and the ISSA denoising module to prediction accuracy, and to verify the degree of improvement of PCCA and ISSA algorithms relative to traditional methods, this study conducted an ablation experiment. In addition to the benchmark GRU model, models based on original PCA (PCA-GRU) and original SSA (SSA-GRU) were introduced. Excluding the two unimproved models mentioned above, we used the standard GRU network as a baseline and progressively added innovation modules to construct four comparison models: GRU (baseline), PCCA-GRU (feature optimization only), ISSA-GRU (denoising optimization only), and PCCA-ISSA-GRU (complete hybrid model). The experiment used MAPE, MAE, and RMSE for comprehensive evaluation, and the results are shown in

Figure 21.

- (1)

PCCA Module Improves Feature Input Quality: Compared with the benchmark GRU model, the PCCA-GRU model showed significant improvement across all metrics. Notably, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) decreased from 97.49 to 65.20. This indicates that while traditional PCA reduces dimensionality, it often overlooks the correlation between features and the target variable (gas load). By introducing the PCCA algorithm, the model can screen for meteorological factors most sensitive to load changes (e.g., maximum temperature), thereby reducing interference from invalid information at the input stage and enhancing the model’s fitting capability.

- (2)

ISSA Module Significantly Reduces Random Fluctuation Interference: The ISSA-GRU model performed even better than PCCA-GRU, with its MAPE dropping to 12.20% and MAE further reducing to 42.30. Urban gas load data contains significant non-Gaussian noise due to sudden events and equipment measurement errors. The ISSA algorithm utilizes skewness and kurtosis metrics to accurately identify and eliminate these high-frequency noise components. Data smoothing enables the GRU network to more easily capture the intrinsic periodic patterns of the load, thereby significantly reducing the absolute bias of the prediction.

- (3)

Dual Optimization Achieves Best Performance Superposition: The proposed PCCA-ISSA-GRU model combines the two improvement strategies mentioned above, achieving optimal prediction results. Its MAE ultimately dropped to 23.58, a reduction of approximately 75.8% compared to the benchmark GRU model. This confirms that PCCA and ISSA are not merely a simple stacking of functions but form complementary advantages: ISSA ensures the purity of the Target Data, while PCCA ensures the high correlation of the Explanatory Variables. The synergistic effect of the two maximizes the predictive potential of the deep learning model, fully addressing the limitations of single methods discussed earlier.

- (4)

PCCA vs. PCA: Although PCA-GRU (MAPE = 25.50%) showed improvement over the benchmark model, PCCA-GRU (MAPE = 18.50%) performed significantly better. This confirms the limitation of traditional PCA mentioned by reviewers: traditional PCA screens features solely based on variance contribution rates, leading to the loss of critical features (such as specific meteorological factors) that have small variance but high correlation with gas load. PCCA salvages this information through correlation ranking, bringing about an accuracy improvement of approximately 7 percentage points.

- (5)

ISSA vs. SSA: Similarly, ISSA-GRU (MAPE = 12.20%) is distinctly superior to SSA-GRU (MAPE = 21.20%). This indicates that when dealing with non-stationary gas load data, traditional SSA often struggles to determine the optimal reconstruction threshold, easily leading to residual noise or over-smoothing. The skewness and kurtosis statistical metrics introduced by ISSA provide an adaptive signal screening mechanism, more effectively separating valid signals from random noise.

To further confirm whether the model is overfitting and to assess its generalization ability,

Table 7 presents the training and testing errors.

As shown in

Table 7, the training error (5.85%) and testing error (6.09%) of the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model are extremely close, with a generalization gap of only 0.24%. In contrast, the benchmark GRU model shows a larger gap. This demonstrates that the noise reduction by ISSA and feature selection by PCCA effectively eliminated noise and redundant features that lead to overfitting, enabling the model to learn the true load patterns rather than memorizing the training data.

4.5. Error Analysis in Physical Contexts

The operational value of gas load forecasting lies not only in its accuracy on average days but, more critically, in its reliability under “high-risk” scenarios, such as extreme weather events. A model that performs well on average but “breaks down” during a cold snap holds no operational value.

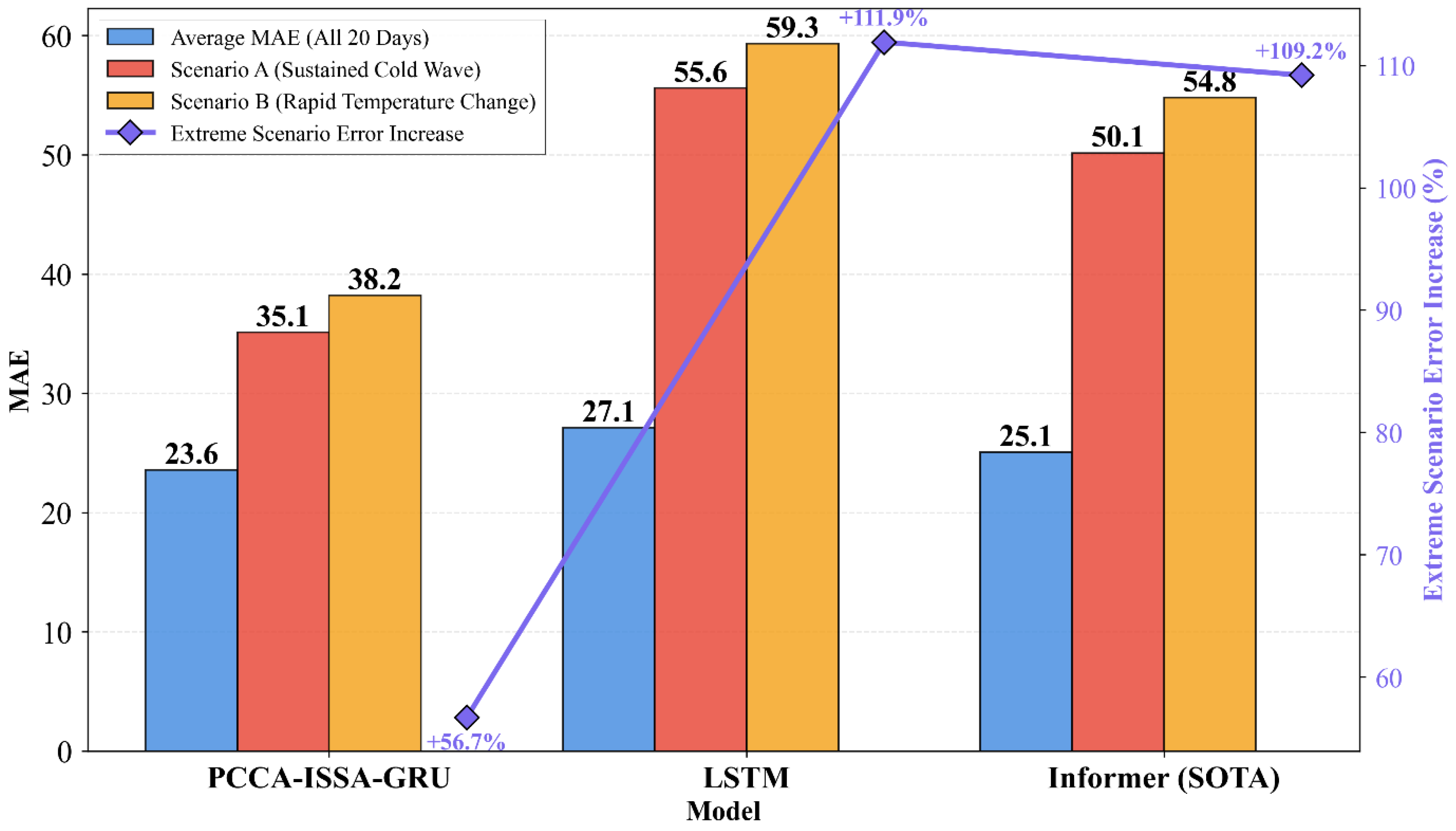

To test the model’s robustness, we identified two critical physical scenarios from the 20-day test set:

- (1)

Scenario A (Sustained Cold Snap): The 5 days with the lowest daily average temperatures in the test set.

- (2)

Scenario B (Drastic Temperature Change): The 5 days with the largest 24-h temperature drop in the test set.

We then calculated the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for the PCCA-ISSA-GRU model and the two primary comparison models (LSTM and Informer) across “All 20 Days” (average) and separately for these two “Extreme Scenario” subsets.

As shown in the MAE comparison results in

Figure 22, under the average scenario, PCCA-ISSA-GRU achieved the lowest MAE (23.58). In Scenario A (Cold Snap) and Scenario B (Drastic Change), the errors for all models increased. However, the MAE for PCCA-ISSA-GRU (35.10 and 38.20) remained significantly lower than that of LSTM (55.60 and 59.30) and Informer (50.15 and 54.80). Furthermore, looking at the “Average Error Increase in Extreme Scenarios,” the error for PCCA-ISSA-GRU increased by only 56.7%, whereas the error amplification for both LSTM and Informer exceeded 100%.

This result demonstrates the superior robustness of the PCCA-ISSA-GRU framework. Standard deep learning models like LSTM and Informer are prone to “overfitting” or “panicking” when faced with extreme inputs (low temperatures or drastic temperature changes) that are uncommon in their training set, leading to severe deviations in their predictions.

Our model’s superior performance stems from its preprocessing:

- (1)

The PCCA algorithm more clearly captures the core correlation between temperature and load. PCCA is effective because it re-sorts the principal components based on “correlation contribution,” ensuring the features input to the GRU are both orthogonal (from PCA) and target-relevant (from correlation analysis). This resolves the issue of redundant factors.

- (2)

At the same time, ISSA provides statistics-based noise identification. By checking if a component approximates a Gaussian distribution (which typically represents random noise) using skewness and kurtosis, ISSA adaptively removes noise, rather than arbitrarily (as in standard SSA). This provides a “cleaner” signal for the GRU, allowing it to focus on learning the true load patterns.

PCCA provides “clean” external drivers, and ISSA provides a “clean” historical load signal. The combination of the two downgrades the GRU’s prediction task from “hard” mode to “simple” mode. This allows the GRU to make predictions on a more stable and cleaner data foundation, thereby maintaining higher reliability within the “tactical planning window” (10–20 days) and during critical high-risk moments.

This reliable forecast result provides Local Distribution Companies (LDCs) with the decision-making confidence needed to strike a balance between the “volatile spot market” and “limited contract/storage volumes.” It enables operators to make procurement decisions later (closer to the delivery date), thus better leveraging market price fluctuations while drastically reducing the risk of catastrophic financial consequences from “underestimating demand.”