Abstract

Background: Retained products of conception (RPOC) after term delivery are uncommon but may lead to persistent abnormal uterine bleeding and other complications. Hysteroscopic removal is considered the optimal management strategy, and technological advances have increasingly enabled operative procedures to be performed safely in an office setting. Clinical case: We report the case of a 43-year-old woman who presented with intermittent spotting four months after spontaneous vaginal delivery. Transvaginal ultrasound revealed a small, avascular hyperechoic intrauterine lesion consistent with retained amniochorionic tissue. She underwent office hysteroscopic removal using a 16 Fr bipolar mini-resectoscope under nitrous oxide (N2O) buccal–nasal analgesia. The procedure was performed using a vaginoscopic, no-touch approach without speculum, tenaculum, or cervical dilation. Complete resection was achieved in a seven-minute procedure, with a postoperative pain score of 2/10 on the VAS and no complications. At 30-day follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic, and an ultrasound confirmed complete resolution. Conclusion: This case demonstrates that retained amniochorionic tissue can be safely and effectively treated in a fully ambulatory setting using mini-resectoscopic technology and N2O analgesia. The combination of minimally invasive instruments, patient-centered procedural strategies, and well-tolerated analgesia supports the growing role of office operative hysteroscopy for selected complex intrauterine conditions.

1. Introduction

Retained products of conception (RPOC) represent a known complication following pregnancy events, including miscarriage, termination, and term delivery. Although the incidence is relatively low after spontaneous vaginal birth, retained amniochorionic tissue may remain adherent to the uterine cavity and lead to persistent abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic discomfort, or, in more complex cases, infection and intrauterine adhesions [1]. Early detection and effective management of RPOC are essential to prevent both short- and long-term complications while preserving fertility and avoiding unnecessary surgical morbidity. Advances in transvaginal ultrasound—particularly when integrated with Doppler evaluation—have significantly improved diagnostic accuracy, supporting the differentiation between vascularized RPOC and avascular intrauterine debris or postpartum tissue [2].

Over the past decade, several studies have increasingly demonstrated that hysteroscopic management offers clear advantages over blind dilation and curettage (D&C). Because D&C is performed without direct visualization, it is associated with a higher likelihood of incomplete tissue removal and iatrogenic damage to the surrounding endometrium. These limitations translate into increased rates of intrauterine adhesions and potentially worse reproductive outcomes. Conversely, hysteroscopic removal allows direct visualization of the uterine cavity, enabling selective resection of pathological tissue and preservation of healthy endometrium [3,4]. Recent evidence, including systematic reviews and long-term follow-up studies, confirms that hysteroscopic treatment results in higher completeness of evacuation and a lower risk of postoperative adhesions, with a better reproductive prognosis compared with D&C [5,6,7]. For these reasons, when expertise and equipment are available, hysteroscopic management is increasingly considered the preferred approach for RPOC.

In parallel to these clinical benefits, substantial technological progress has reshaped the approach to intrauterine surgery. The development of miniaturized bipolar mini-resectoscopes, typically 15–16 French in diameter, has markedly expanded the feasibility of performing operative hysteroscopy in outpatient settings. These smaller-caliber instruments reduce the need for cervical dilation and often eliminate the necessity for general anesthesia, improving patient comfort while maintaining effective cutting and coagulation capability [8]. Mini-resectoscopic techniques have shown high safety and efficacy not only for RPOC but also for endometrial polyps, type 0–1 submucosal fibroids, uterine septa, and other focal intrauterine lesions, consolidating their role in modern minimally invasive gynecology [8].

The growing safety and precision of office-based hysteroscopy have been accompanied by advances in analgesic strategies, which facilitate patient tolerance during operative procedures. Among these, nitrous oxide (N2O) has gained prominence for its rapid onset, anxiolytic effect, and self-regulated inhalation, offering an optimal balance between simple oral analgesia and anesthesiologist-led sedation [9,10]. Studies have shown that N2O reduces procedural pain and anxiety during gynecologic office procedures, including hysteroscopy and hysteroscopic sterilization, while allowing patients to remain conscious and cooperative with rapid recovery [9,11].

These developments align with the broader concept of “positive hysteroscopy,” which emphasizes patient-centered care, emotional comfort, and reduction in procedural stress. Environmental elements such as soft lighting, music, and continuous communication with staff contribute to reducing anxiety and improving patient satisfaction [12,13].

Despite advancements in both technology and pain management, the use of outpatient operative hysteroscopy for postpartum retained amniochorionic tissue remains underreported. Demonstrating the feasibility of managing such conditions in an office setting may help broaden clinical practice and refine patient selection while optimizing healthcare resource utilization.

In this context, we present the case of a woman with retained amniochorionic tissue successfully treated using a 16 Fr bipolar mini-resectoscope under N2O buccal–nasal analgesia in an outpatient setting. This case underscores not only the technical efficacy and safety of the approach but also the high level of patient satisfaction achieved through a fully integrated, patient-centered procedural model.

2. Clinical Case

We will present a case of a 43-year-old woman from Turin, gravida 1 para 1, with an unremarkable medical and surgical history, who delivered a healthy infant via spontaneous vaginal delivery in 2024. Her postpartum course was initially regular; however, in the weeks following delivery, she reported intermittent spotting, which she attributed to postpartum involution. She did not experience fever, pelvic pain, or other systemic symptoms.

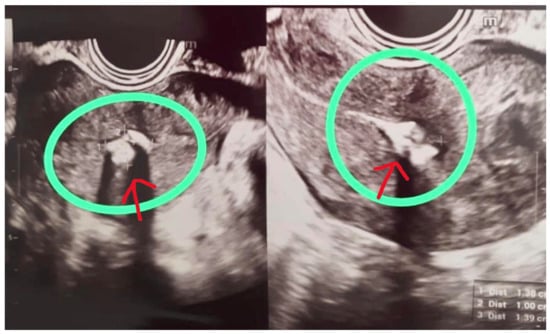

During a routine follow-up visit four months after delivery, her referring gynecologist performed a transvaginal ultrasound that revealed a hyperechoic endometrial lesion measuring 13 × 10 × 14 mm, located in the right lateral portion of the uterine cavity. Color Doppler evaluation demonstrated minimal vascularity (color score 1, minimal Doppler vascularity), consistent with retained amniochorionic tissue rather than vascularized RPOC (Figure 1). These features—small size, minimal vascularity, and late postpartum presentation—were considered favorable for an office hysteroscopic approach.

Figure 1.

Transvaginal ultrasound image showing a hyperechoic, avascular lesion (circled) in the right lateral uterine wall.

The patient was subsequently referred to the Outpatient Hysteroscopy Unit of ASL Biella. During counseling, the therapeutic options—including expectant management, blind curettage, and hysteroscopic removal—were discussed in detail, and we opted for office hysteroscopic removal.

A progestin-only pill containing drospirenone was prescribed for four weeks to stabilize the endometrium and optimize the operative field prior to hysteroscopy.

2.1. Pre-Procedural Analgesia and Setting

On the day of the procedure, the patient was welcomed into a dedicated outpatient hysteroscopy suite designed according to patient-centered care principles. The environment included soft lighting, relaxing background music, and continuous verbal reassurance by the assisting nurse and hysteroscopist. Five minutes before the start of the intervention, nitrous oxide (N2O) was administered via a buccal–nasal mask, using a demand-valve system that allowed self-regulated inhalation throughout the procedure. Nitrous oxide was selected because an operative procedure performed with a 16 Fr mini-resectoscope generally requires a higher level of analgesic comfort than diagnostic hysteroscopy.

The patient remained fully conscious, cooperative, and hemodynamically stable during N2O administration. No premedication or paracervical block was required.

2.2. Operative Procedure

A 16 Fr bipolar mini-resectoscope was introduced using a no-touch vaginoscopic approach, without employing a vaginal speculum, tenaculum, or cervical dilation. The cervical canal accommodated the scope without resistance, and normal saline was used as the distension medium.

Upon entry into the uterine cavity, a 1.5 cm whitish, avascular residual amniochorionic fragment was identified on the right lateral wall. The surrounding endometrium appeared homogeneous, with no evidence of atypical vascularization, placental bed disruption, or signs suggestive of gestational trophoblastic disease.

The pathological tissue was resected using a single-use bipolar cutting loop, performing smooth shaving movements under continuous visualization. The bipolar technology ensured precise excision with minimal thermal spread. Tissue removal proceeded without bleeding or need for coagulation. Visibility remained optimal throughout the procedure with stable uterine distension.

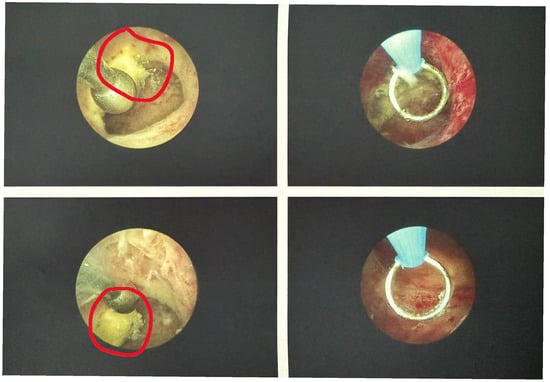

The total operative time was 7 min, from insertion of the hysteroscope to removal. No intraoperative complications occurred, and no additional instrumentation was required (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hysteroscopic view before (left) and after (right) resection of the amniochorionic tissue.

2.3. Immediate Post-Procedure Course

At the end of the intervention, the patient reported a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain score of 2/10, expressing great satisfaction with the outpatient management method, the minimal discomfort felt, and the quick recovery. She remained in the recovery area for 10 min and exhibited no dizziness, nausea, or delayed effects of inhaled analgesia. She was discharged home the same day with instructions for routine care and no pharmacological therapy. This favorable experience likely reflects the combined effect of minimally invasive instrumentation, effective analgesia, and a patient-centered environment.

2.4. Follow-Up

Thirty days after the procedure, the patient was reassessed by her referring gynecologist.

Histopathological examination was performed, and the results confirmed the presence of amniochorionic residual tissue. Transvaginal ultrasound revealed a completely normal endometrial cavity, with normal endometrial echo, absence of focal lesions, and no evidence of residual tissue or intrauterine synechiae. Clinically, she reported complete resolution of abnormal uterine bleeding and a full return to her baseline well-being. She expressed strong satisfaction with the outpatient management approach, the low discomfort experienced, and the rapid recovery.

3. Discussion

This case illustrates the feasibility of managing retained amniochorionic tissue in a fully ambulatory setting using a 16 Fr bipolar mini-resectoscope under nitrous oxide (N2O) analgesia, with excellent clinical outcome and high patient satisfaction. It aligns with and extends current evidence on the role of hysteroscopy—and specifically office hysteroscopy—as the preferred modality for treating retained products of conception (RPOC).

The rationale for choosing N2O over oral analgesia, paracervical block, or no anesthesia is that the procedure involved operative resection using a 16 Fr mini-resectoscope, which generally requires a higher level of analgesic comfort than diagnostic hysteroscopy; N2O provides anxiolysis, mild analgesia, and rapid recovery, improving compliance and tolerability during see-and-treat procedures; and the patient remained fully alert and cooperative, with a VAS score of 2/10, confirming the suitability of this modality.

RPOC is a recognized complication after pregnancy, including after term vaginal delivery, and is associated with abnormal bleeding, infection, and long-term sequelae such as intrauterine adhesions and impaired fertility [1,12]. In their systematic review, Hooker et al. showed that retained tissue and its management may significantly influence subsequent reproductive outcomes, underlining the importance of accurate diagnosis and minimally traumatic treatment [1]. Foreste et al. further emphasized that hysteroscopic removal, compared with blind dilation and curettage (D&C), is associated with lower rates of intrauterine adhesions and more favorable reproductive outcomes, and should be considered the treatment of choice when expertise is available [5].

In our patient, transvaginal ultrasound demonstrated a small hyperechoic intrauterine lesion with minimal vascularization, consistent with retained amniochorionic tissue. These sonographic features are in line with what has been described as typical for RPOC, where a thickened endometrial echo complex with focal echogenic tissue and variable Doppler flow can aid in differentiating true RPOC from blood clots or regular postpartum changes [2]. Accurate imaging is crucial to avoid both under-treatment and overtreatment; recent office-hysteroscopy series have highlighted that a significant proportion of women referred for suspected RPOC actually have no residual tissue at hysteroscopy, reinforcing the importance of careful selection of candidates [14].

Table 1 summarizes the main clinical, sonographic, and procedural criteria proposed in the literature to identify candidates suitable for ambulatory treatment.

Table 1.

Criteria for Office Management of RPOC.

3.1. Hysteroscopic vs. Blind Management of RPOC

Traditionally, RPOC has been managed with blind suction curettage; however, growing evidence supports hysteroscopic resection as safer and more effective. Multiple observational studies and reviews have reported high rates of complete removal and low complication rates with hysteroscopy [3,6,7,12,14,15]. Alonso Pacheco et al. reported that operative hysteroscopy was highly effective for RPOC and suggested it should be preferred to conventional D&C [3]. Ben-Ami et al. found comparable overall fertility outcomes between hysteroscopic resection and D&C, but a shorter time to conception and a lower rate of new infertility diagnoses in the hysteroscopy group [4]. Vitale et al., in a systematic review and meta-analysis, confirmed that hysteroscopic removal yields high complete resection rates with reassuring reproductive outcomes and low intrauterine adhesion rates [6]. Earlier works by Golan et al. and Incognito et al. similarly support hysteroscopic removal as a safe approach with favorable fertility results [7,15].

Our case confirms that these advantages can be preserved even when the procedure is conducted in an office setting, without general or regional anesthesia. The complete removal of a postpartum remnant in a single seven-minute procedure, with subsequent resolution of bleeding and normal ultrasound findings at 30-day follow-up, mirrors the high success and low complication rates reported in larger series [3,5,6,7,16,17].

3.2. Office Hysteroscopy and Mini-Resectoscopic Technology

The miniaturization of hysteroscopic instruments has been a key factor in making operative office hysteroscopy feasible. The 16 Fr bipolar mini-resectoscope used in this case allows for effective cutting and coagulation with minimal need for cervical dilation. Papalampros et al. first demonstrated that mini-resectoscopes are efficient and acceptable for intrauterine surgery (e.g., polyps and small fibroids) and can be used without general anesthesia [8]. Subsequent studies have extended this experience to RPOC and other complex intrauterine pathology managed in ambulatory settings [18].

Cohen et al. evaluated office hysteroscopy for RPOC and showed that it was well tolerated by 96% of patients, with a 65% overall success rate; failures were mainly related to larger RPOC size, bleeding, and pain [16]. More recent data from Han et al. and Mohr-Sasson et al. confirm that hysteroscopic treatment, including office-based procedures, can achieve high complete removal rates and good menstruation recovery with low adhesion rates [14,19]. Incognito et al. reported on 468 women referred for presumed RPOC: office hysteroscopy successfully treated most cases, although a substantial proportion had no RPOC at hysteroscopy, underscoring once again the need for refined pre-operative diagnostic criteria [15]. Barel et al. specifically investigated see-and-treat office hysteroscopy for RPOC (often without anesthesia), reporting success rates around or above 90% and supporting the feasibility of fully ambulatory management [20].

Our experience contributes to this body of evidence by showing that even a postpartum retained amniochorionic remnant can be safely resected in the office using a bipolar mini-resectoscope and a vaginoscopic, no-touch approach. In our case, access was achieved without a speculum, tenaculum, or cervical dilation, which likely contributed to the low reported pain (VAS 2/10) and absence of complications.

3.3. Nitrous Oxide and Analgesic Strategy

Pain control is a critical determinant of the acceptability and diffusion of office hysteroscopy. Simple oral analgesia alone is often insufficient for more complex operative procedures, while systemic sedation or anesthesiologist-led techniques increase costs and logistical challenges. Nitrous oxide offers an intermediate solution with rapid onset and offset, mild analgesic and anxiolytic properties, and a favorable safety profile [10].

Although most N2O data come from obstetric analgesia, Rosen’s systematic review concluded that N2O is safe for mothers, neonates, and staff, with acceptable analgesic efficacy and rapid recovery [10]. Del Valle Rubido et al. specifically studied N2O in office hysteroscopy for polypectomy and showed that a 50% N2O/O2 mixture significantly reduced pain and improved tolerance compared with paracervical block and control groups [9]. Schneider et al. demonstrated that N2O/O2 similarly decreased pain during in-office hysteroscopic sterilization compared to oral sedation, with good patient satisfaction and minimal side effects [11]. These data support the use of N2O as a valuable adjunct for gynecologic office procedures requiring a higher level of analgesia, such as operative hysteroscopy.

In our case, the use of N2O via buccal–nasal mask, initiated five minutes before the procedure and continued throughout, allowed the patient to remain conscious, cooperative, and hemodynamically stable, with low pain perception (VAS 2/10) and rapid recovery, without the need for additional local anesthesia or systemic sedatives. This experience is consistent with the literature indicating that N2O is safe, easy to administer, and well suited to short office procedures [9,10,11].

3.4. Patient-Centered Environment and “Positive Hysteroscopy”

Beyond instruments and drugs, the procedural environment exerts a measurable impact on pain and satisfaction. Anxiety is a strong predictor of pain perception during hysteroscopy [12,17]. Gambadauro et al. reported that anxiety during outpatient hysteroscopy may increase pain perception and negatively affect procedural success and patient satisfaction [12]. Sorrentino et al. confirmed that baseline anxiety, waiting time, and duration of the procedure are positively correlated with pain scores, and proposed interventions aimed at reducing pre-procedural anxiety to improve the outpatient hysteroscopy experience [17].

Complementary strategies such as music and simple environmental modifications have been shown to be effective. In a randomized trial, Angioli et al. demonstrated that background music during office hysteroscopy significantly reduced both anxiety and perceived pain, leading to greater overall comfort [13]. These findings are consistent with the concept of “positive hysteroscopy,” which emphasizes empathetic communication, a calm environment, and patient involvement as core elements of care.

In the present case, the outpatient setting was deliberately organized with soft lighting, background music, and continuous reassurance by staff. The very low pain score and the patient’s high satisfaction are in line with the evidence that such interventions, combined with minimally invasive technology and appropriate analgesia, can transform hysteroscopy—even when operative and potentially complex—into a well-tolerated experience [12,13,17,21].

3.5. Strengths, Limitations, and Implications

As a single case report, our experience cannot establish causality or define precise indications. The lesion was relatively small (approximately 1.5 cm) and avascular, and the patient had no comorbidities—conditions that are favorable for office management. Current guidelines and studies suggest that factors such as RPOC size, vascularity, ongoing bleeding, hemodynamic stability, and interval from delivery or abortion should be considered when selecting candidates for office hysteroscopic treatment [5,6,13,14,15,18,19,20]. Large, highly vascular, or very recent postpartum RPOC may still be better managed in an operating room setting, with anesthesia support and blood products readily available.

Nevertheless, this case offers several important messages:

- Feasibility: Even postpartum retained amniochorionic tissue can be safely and effectively managed in an office environment using a bipolar mini-resectoscope and a vaginoscopic approach, consistent with recent office-hysteroscopy series [7,14,15,18,19].

- Analgesia: N2O appears to be a practical and effective analgesic option for operative office hysteroscopy, complementing evidence from polypectomy and hysteroscopic sterilization studies [9,10,11].

- Patient experience: A structured, patient-centered setting—soft light, music, and continuous communication—likely contributed to the low pain scores and excellent satisfaction, in agreement with data on anxiety and environmental modulation in outpatient hysteroscopy [12,13,17].

Future research should further explore standardized protocols combining mini-resectoscopic technology, N2O analgesia, and patient-centered environmental measures, ideally in prospective cohorts or randomized studies, to define which subgroups of RPOC (including postpartum cases) can most safely and efficiently be managed in the outpatient setting. Therefore, careful patient selection remains crucial when considering office hysteroscopic management of postpartum RPOC.

4. Conclusions

This case demonstrates that the hysteroscopic management of retained amniochorionic tissue can be safely and effectively performed in a fully ambulatory setting using a 16 Fr bipolar mini-resectoscope and nitrous oxide analgesia. The procedure was brief, well tolerated, and associated with rapid recovery and complete clinical resolution, highlighting the potential of combining minimally invasive technology, patient-centered procedural environments, and modern analgesic strategies to expand the scope of office hysteroscopy.

Beyond the successful removal of the intrauterine remnant, this experience reinforces the importance of tailoring care to patient comfort. Elements such as a calm environment, continuous communication, and a vaginoscopic no-touch technique contributed significantly to the patient’s positive perception and low pain score. These aspects, often underestimated, are essential components of contemporary outpatient operative gynecology.

Looking forward, broader adoption of mini-resectoscopic systems and safe, easy-to-administer analgesic modalities like nitrous oxide may further shift the management of selected complex intrauterine conditions from operating theaters to ambulatory units, with benefits in terms of accessibility, resource optimization, and patient satisfaction. Future research should aim to better define patient selection criteria, establish standardized protocols for analgesia and procedural environment, and generate prospective data evaluating outcomes, safety, cost-effectiveness, and patient-reported experience measures.

Overall, this case supports an evolving paradigm in which office hysteroscopy, when performed with appropriate expertise and technology, becomes a first-line option for a growing number of operative indications—even those traditionally reserved for the operating room.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., A.L. and D.D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and A.L.; writing—review and editing, P.A., G.L., T.B., D.C. and S.V.; supervision, L.L. and B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for this case report, in accordance with the policy of the Ethics Committee of Maggiore della Carità Hospital, because case reports are not considered research and therefore do not fall under the scope of institutional review.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RPOC | Retained products of conception |

| N2O | Nitrous Oxide |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| D&C | Dilatation and Curettage |

References

- Hooker, A.B.; Aydin, H.; Brölmann, H.A.M.; Huirne, J.A.F. Long-term complications and reproductive outcome after the management of retained products of conception: A systematic review. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 105, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellmyer, M.A.; Desser, T.S.; Maturen, K.E.; Jeffrey, R.B., Jr.; Kamaya, A. Physiologic, histologic, and imaging features of retained products of conception. Radiographics 2013, 33, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Ami, I.; Melcer, Y.; Smorgick, N.; Schneider, D.; Pansky, M.; Halperin, R. A comparison of reproductive outcomes following hysteroscopic management versus dilatation and curettage of retained products of conception. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 127, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, L.A.; Timmons, D.; Saad, A.; Nulsen, J.; Benadiva, C. Hysteroscopic management of retained products of conception. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn 2019, 11, 319–326. [Google Scholar]

- Foreste, V.; Gallo, A.; Manzi, A.; Riccardi, C.; Carugno, J.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A. Hysteroscopy and retained products of conception: An update. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2021, 10, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.G.; Riemma, G.; Carugno, J.; Cholkeri-Singh, A.; Della Corte, L.; Cianci, S.; Schiattarella, A.; Riemma, G.; De Franciscis, P. Surgical and reproductive outcomes after hysteroscopic removal of retained products of conception: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, A.; Dishi, M.; Shalev, A.; Keidar, R.; Ginath, S.; Sagiv, R. Operative hysteroscopy to remove retained products of conception: Novel treatment of an old problem. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011, 18, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalampros, P.; Gambadauro, P.; Papadopoulos, N.; Almaloglou, K.; Hassiakos, D. The mini-resectoscope: A new instrument for office hysteroscopic surgery. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2009, 88, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle Rubido, C.; Solano Calvo, J.A.; Rodríguez Miguel, A.; Delgado Espeja, J.J.; González Hinojosa, J.; Zapico Goñi, A. Inhalation analgesia with nitrous oxide versus other analgesic techniques in hysteroscopic polypectomy: A pilot study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2015, 22, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: A systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, S110–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.N.; Riley, R.; Espey, E.; Mishra, S.I.; Singh, R.H. Nitrous oxide for pain management during in-office hysteroscopic sterilization: A randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2017, 95, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambadauro, P.; Navaratnarajah, R.; Carli, V. Anxiety at outpatient hysteroscopy. Gynecol. Surg. 2015, 12, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angioli, R.; De Cicco Nardone, C.; Plotti, F.; Cafà, E.V.; Dugo, N.; Damiani, P.; Ricciardi, R.; Linciano, F.; Terranova, C. Use of music to reduce anxiety during office hysteroscopy: A prospective randomized trial. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014, 21, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Shi, G.; Zheng, A.; Ruan, J. Hysteroscopy for retained products of conception: A single-institution experience. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incognito, G.G.; Maček, K.J.; Blaganje, M.; Starič, K.D.; Ettore, G.; Ettore, C.; Podgornik, M.L.; Verdenik, I.; Šuster, N.K. Effectiveness of office hysteroscopy for retained products of conception: Insights from 468 cases. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2025, 312, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Cohen, Y.; Sualhi, S.; Rayman, S.; Azem, F.; Rattan, G. Office hysteroscopy for removal of retained products of conception: Can we predict treatment outcome? Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 44, 683–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, F.; Petito, A.; Angioni, S.; D’Antonio, F.; Severo, M.; Solazzo, M.C.; Tinelli, R.; Nappi, L. Impact of anxiety levels on the perception of pain in patients undergoing office hysteroscopy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 303, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipari, G.; Messina, A.; Teston, C.; Alessi, P.; Mariani, A.; Bruno, T.; Florio, F.; Vegro, S.; Leo, L.; Masturzo, B. Combined Treatment of Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation Using a 16 Fr Miniresectoscope in an Office Setting Without Anesthesia: A Case Report. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 2024, 9216109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr-Sasson, A.; Gur, T.; Meyer, R.; Mashiach, R.; Stockheim, D. Office operative hysteroscopy for the management of retained products of conception: A comparative study. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barel, O.; Treger, S.; Sabag, D.N.; Hamu, B.; Stolovitch, N.; Barak, S.; Levy, G.; Sharvit, M. Hysteroscopic Treatment of Retained Products of Conception Using See and Treat Operative Office Hysteroscopy Without Anesthesia. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2025, 32, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libretti, A.; Vitale, S.G.; Saponara, S.; Corsini, C.; Aquino, C.I.; Savasta, F.; Tizzoni, E.; Troìa, L.; Surico, D.; Angioni, S.; et al. Hysteroscopy in the new media: Quality and reliability analysis of hysteroscopy procedures on YouTube™. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 308, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.