Molecular Biomarkers of Endometrial Function and Receptivity in Natural and Stimulated Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Cycles

Abstract

1. Introduction

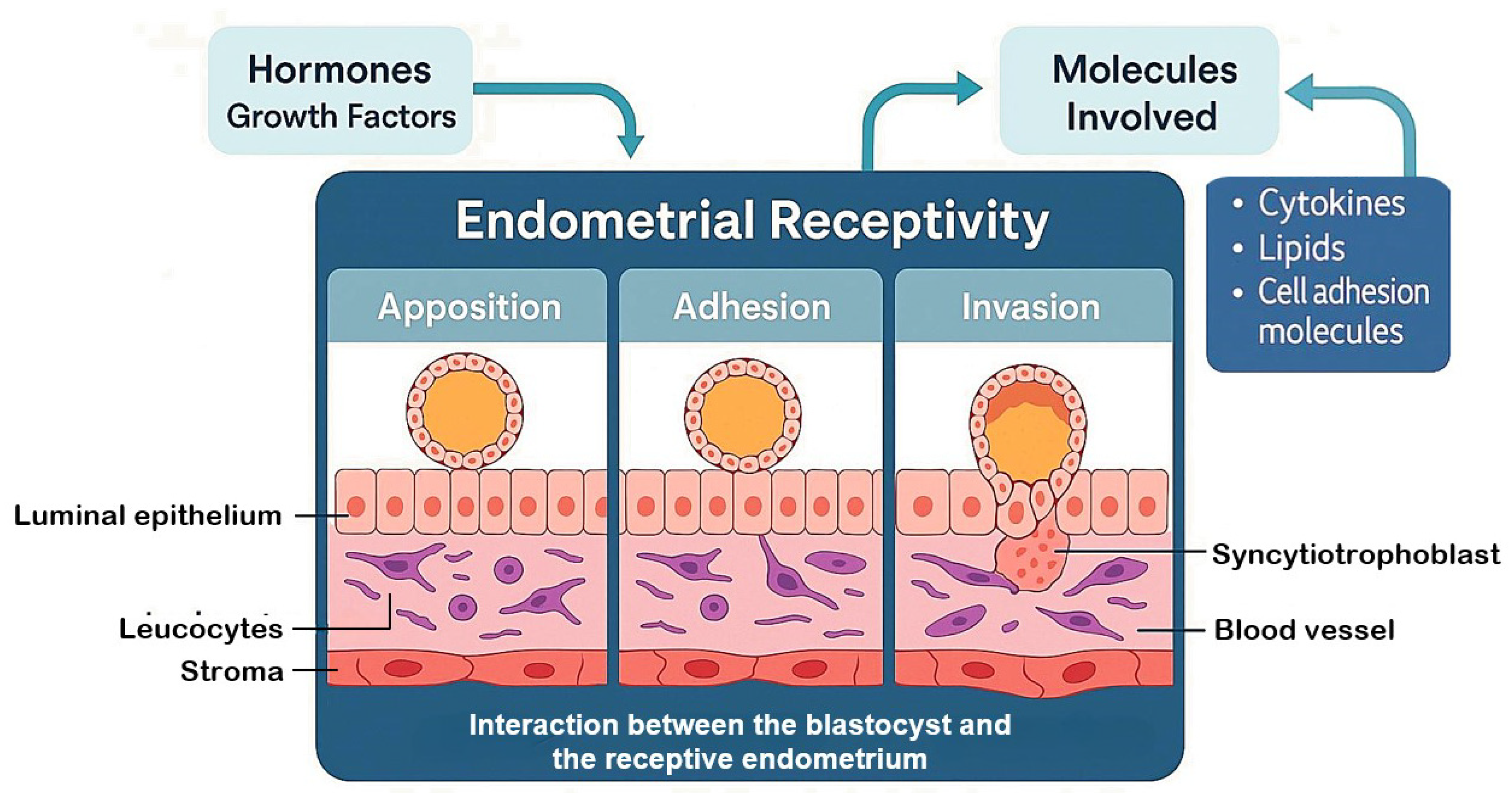

2. Endometrial Receptivity and Implantation

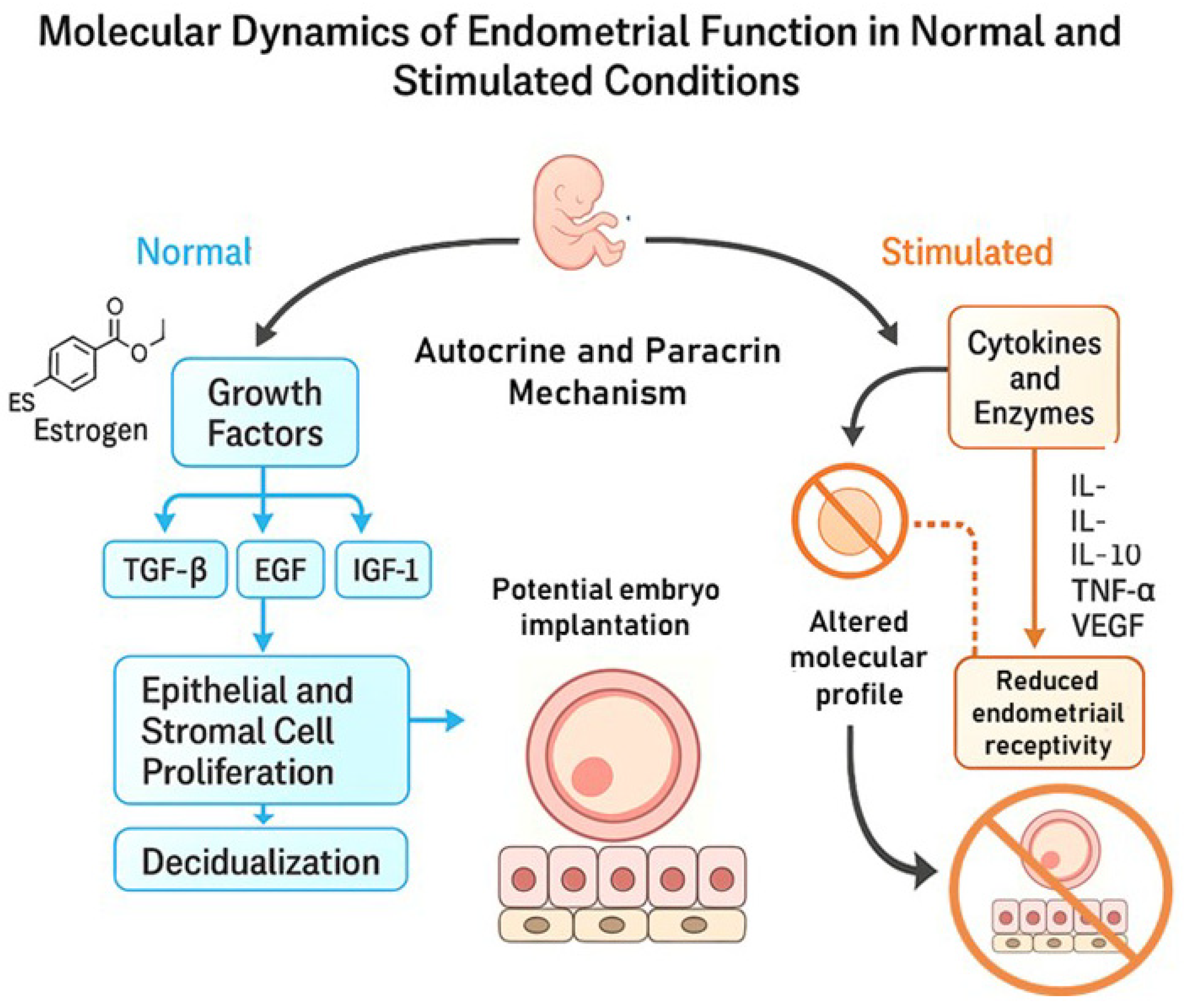

3. Molecular Dynamics of Endometrial Function in Normal and Stimulated Conditions

4. Biomarkers of Endometrial Receptivity

5. Evolution in Receptivity Evaluation Methods

5.1. Histology and Noyes Criteria

5.2. Pinopods or Uterodomes

6. Molecular Factors

6.1. Growth Factors and Cytokines

6.2. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

6.3. Cell Adhesion Molecules (CAMs)

6.4. Cadherin

6.5. Mucin 1 (MUC1)

6.6. CD44 Protein

6.7. Selectin

6.8. Immunoglobulin

7. Modulators of Trophoblast Invasion and Decidualization

7.1. Glycodelin

7.2. Stem Cell Factor (SCF)

7.3. CD34 Protein

7.4. Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-1 (IGFBP-1) and IGF 1 Receptor (IGF-1R)

7.5. Homeobox Genes

8. Signaling Pathways in Embryo Implantation

9. Advancements in Embryo Receptivity Diagnostics

10. Summary and Clinical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALCAM | Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule |

| APC | Adenomatous polyposis coli |

| ART | Assisted reproductive technology |

| bFGF | Basic fibroblast growth factor |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BMP | Bone morphogenetic proteins |

| BMPR | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor |

| CAM | Cell adhesion molecule |

| CD34 | Cluster of differentiation 34 |

| CEACAM1 | Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| c-Myc | Cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene |

| CNTF | Ciliary neurotrophic factor |

| CT-1 | Cardiotrophin 1 |

| CTB | Cytotrophoblastic |

| CXCL14 | Chemokine ligand 14 |

| DG-SIGN | Dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 grabbing non-integrin |

| DKK1 | Dickkopf-related protein 1 |

| DSCs | Decidual stromal cell |

| E2 | Estrogen |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| EGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| ERα | Estrogen receptor α |

| ERA | Endometrial receptivity array |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ESC | Endometrial stromal cells |

| EVT | Extravillous trophoblast |

| EVCT | Extravillous cytotrophoblast |

| FGF-R1 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 |

| FOXO 1 | Forkhead transcription factor 1 |

| GlyCAM-1 | Glycosylation-dependent cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| GnRH | Gonadotropin-releasing Hormone |

| Gd | Glycodelin |

| GDF | Growth differentiation factor |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| Gp | Glycoprotein |

| HA | Hyaluronan or hyaluronic acid |

| HB-EGF | Heparin-binding EGF |

| hCG | Human chorionic gonadotropin |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| HLA-G | Human leukocyte antigen-G |

| HOXA10 | Homeobox A10 |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| ICSI | Intracytoplasmic sperm injection |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| IGF2BP1 | Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 |

| IGFBP-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ITGAE | Integrin alpha E |

| ITGB8 | Integrin subunit beta 8 |

| IVF | In vitro fertilization |

| JAK/STAT | Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| KDR | Kinase insert domain receptor |

| LAMA1 | Laminin subunit alpha 1 |

| LH | Luteinizing Hormone |

| LIF | Leukaemia inhibitory factor |

| LSL | L-selectin ligand |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCAM | Mean corpuscular haemoglobin |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MMP | Metalloproteinase |

| MUC 1 | Mucin 1 |

| NK | Natural killer |

| OSM | Oncostatin M |

| PAEP | Progestagen-associated endometrial protein |

| PCOS | Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PDGFA | Platelet-derived growth factor A |

| PDGFRA | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor, alpha polypeptide |

| PDGF-Rβ | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta |

| PECAM1 | Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| PGR-B | Progesterone receptor-B |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase |

| PRL | Prolactin |

| Rap 1 | Ras-associated protein 1 |

| rFSH | Recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone |

| SCF | Stem cell factor |

| RIF | Recurrent implantation failure |

| tsRNA | Transfer RNA-derived small RNA |

| SERM | Selective estrogen modulator |

| SMAD | Suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic |

| SGK 1 | Serum/glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 |

| TGF | Transforming growth factor |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor alpha |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WOI | Window of implantation |

| Wnt | Wingless-related integration site |

References

- Somigliana, E.; Li Piani, L.; Paffoni, A.; Salmeri, N.; Orsi, M.; Benaglia, L.; Vercellini, P.; Vigano, P. Endometriosis and IVF treatment outcomes: Unpacking the process. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2023, 21, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benkhalifa, M.; Joao, F.; Duval, C.; Montjean, D.; Bouricha, M.; Cabry, R.; Bélanger, M.C.; Bahri, H.; Miron, P.; Benkhalifa, M. Endometrium Immunomodulation to Prevent Recurrent Implantation Failure in Assisted Reproductive Technology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psychoyos, A. Hormonal control of ovoimplantation. Vitam. Horm. 1973, 31, 201–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achache, H.; Revel, A. Endometrial receptivity markers, the journey to successful embryo implantation. Hum. Reprod. Update 2006, 12, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, A.; Gangi, L.M.; Zegers-Hochschild, F.; Balmaceda, J.; Pommer, R.; Trejo, L.; Pacheco, I.M.; Salvatierra, A.M.; Henríquez, S.; Quezada, M.; et al. Differences in the endometrial transcript profile during the receptive period between women who were refractory to implantation and those who achieved pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, N. Endometrial receptivity array: Clinical application. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 8, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giudice, G. Genes of the sea urchin embryo: An annotated list as of December 1994. Dev. Growth Differ. 1995, 37, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabibzadeh, S. Molecular control of the implantation window. Hum. Reprod. Update 1998, 4, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromer, J.G.; Aldad, T.S.; Taylor, H.S. Defining the proliferative phase endometrial defect. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Denker, H.W. Implantation: A cell biological paradox. J. Exp. Zool. 1993, 266, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aplin, J.D. The cell biological basis of human implantation. Baillieres. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2000, 14, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simón, C.; Martin, J.C.; Meseguer, M.; Caballero-Campo, P.; Valbuena, D.; Pellicer, A. Embryonic regulation of endometrial molecules in human implantation. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 2000, 55, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, Y.S.; Ackerman, K.M. Embryology, Week 1. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Franasiak, J.M.; Alecsandru, D.; Forman, E.J.; Gemmell, L.C.; Goldberg, J.M.; Llarena, N.; Margolis, C.; Laven, J.; Schoenmakers, S.; Seli, E. A review of the pathophysiology of recurrent implantation failure. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 1436–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbi, S.; Hamilton, A.E.; Vo, K.C.; Tulac, S.; Overgaard, M.T.; Dosiou, C.; Le Shay, N.; Nezhat, C.N.; Kempson, R.; Lessey, B.A.; et al. Molecular phenotyping of human endometrium distinguishes menstrual cycle phases and underlying biological processes in normo-ovulatory women. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 1097–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, L.C.; Germeyer, A.; Tulac, S.; Lobo, S.; Yang, J.P.; Taylor, R.N.; Osteen, K.; Lessey, B.A.; Giudice, L.C. Expression profiling of endometrium from women with endometriosis reveals candidate genes for disease-based implantation failure and infertility. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 2870–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, E.; Stoikos, C.; Stafford-Bell, M.; Clark, I.; Paiva, P.; Kovacs, G.; Salamonsen, L.A. Interleukin-11, IL-11 receptoralpha and leukemia inhibitory factor are dysregulated in endometrium of infertile women with endometriosis during the implantation window. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2006, 69, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laird, S.M.; Tuckerman, E.M.; Dalton, C.F.; Dunphy, B.C.; Li, T.C.; Zhang, X. The production of leukaemia inhibitory factor by human endometrium: Presence in uterine flushings and production by cells in culture. Hum. Reprod. 1997, 12, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrzypczak, J.; Szczepańska, M.; Puk, E.; Kamieniczna, M.; Kurpisz, M. Peritoneal fluid cytokines and sICAM-1 in minimal endometriosis: Search for discriminating factors between infertility and/or endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2005, 122, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikolajczyk, M.; Wirstlein, P.; Skrzypczak, J. The impact of leukemia inhibitory factor in uterine flushing on the reproductive potential of infertile women--a prospective study. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2007, 58, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, H.L.; Li, S.J.; Wang, H.B.; Yang, Z.M. Calcitonin immunostaining in monkey uterus during menstrual cycle and early pregnancy. Endocrine 2002, 18, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Brudney, A.; Cheon, Y.P.; Fazleabas, A.T.; Bagchi, I.C. Progesterone induces calcitonin expression in the baboon endometrium within the window of uterine receptivity. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 68, 1318–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, H.L.; Jeong, J.W.; Tsai, S.Y.; Lydon, J.P.; DeMayo, F.J. In Vivo analysis of progesterone receptor action in the uterus during embryo implantation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2008, 19, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.K.; Wang, X.N.; Paria, B.C.; Damm, D.; Abraham, J.A.; Klagsbrun, M.; Andrews, G.K.; Dey, S.K. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor gene is induced in the mouse uterus temporally by the blastocyst solely at the site of its apposition: A possible ligand for interaction with blastocyst EGF-receptor in implantation. Development 1994, 120, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, H.J.; Barlow, D.H.; Mardon, H.J. Temporal and spatial regulation of expression of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor in the human endometrium: A possible role in blastocyst implantation. Dev. Genet. 1998, 21, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessey, B.A.; Gui, Y.; Apparao, K.B.; Young, S.L.; Mulholland, J. Regulated expression of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) in the human endometrium: A potential paracrine role during implantation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2002, 62, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Kan, A.; Hitkari, J.; Taylor, B.; Tallon, N.; Warraich, G.; Yuzpe, A.; Nakhuda, G. The role of the endometrial receptivity array (ERA) in patients who have failed euploid embryo transfers. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glujovsky, D.; Pesce, R.; Sueldo, C.; Quinteiro Retamar, A.M.; Hart, R.J.; Ciapponi, A. Endometrial preparation for women undergoing embryo transfer with frozen embryos or embryos derived from donor oocytes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 10, CD006359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilcox, A.J.; Baird, D.D.; Weinberg, C.R. Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 1796–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabibzadeh, S.; Babaknia, A. The signals and molecular pathways involved in implantation, a symbiotic interaction between blastocyst and endometrium involving adhesion and tissue invasion. Hum. Reprod. 1995, 10, 1579–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, D.C.; Bronson, R.P.; Dahl, J.; Carroll, J.P.; Benjamin, T.L. Accelerated development of polyoma tumors and embryonic lethality: Different effects of p53 loss on related mouse backgrounds. Cell Growth Differ. 2000, 11, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lopata, A.; Bentin-Ley, U.; Enders, A. “Pinopodes” and implantation. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2002, 3, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz Martínez, A.d.J. Evaluación de Marcadores Moleculares de Receptividad Endometrial en Pacientes con Infertilidad Primaria. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Ciencias, Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey, A.M.; Smith, S.K. The endometrium as a cause of implantation failure. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2003, 17, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norwitz, E.R.; Schust, D.J.; Fisher, S.J. Implantation and the survival of early pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aplin, J.D. Implantation, trophoblast differentiation and haemochorial placentation: Mechanistic evidence in vivo and in vitro. J. Cell Sci. 1991, 99, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Jaffe, R.C.; Fazleabas, A.T. Blastocyst invasion and the stromal response in primates. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischof, P.; Martelli, M.; Campana, A.; Itoh, Y.; Ogata, Y.; Nagase, H. Importance of matrix metalloproteinases in human trophoblast invasion. Early Pregnancy 1995, 1, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gellersen, B.; Brosens, I.A.; Brosens, J.J. Decidualization of the human endometrium: Mechanisms, functions, and clinical perspectives. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2007, 25, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltepe, E.; Bakardjiev, A.I.; Fisher, S.J. The placenta: Transcriptional, epigenetic, and physiological integration during development. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaitu’u-Lino, T.J.; Morison, N.B.; Salamonsen, L.A. Estrogen is not essential for full endometrial restoration after breakdown: Lessons from a mouse model. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 5105–5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice, L.C. Growth factors and growth modulators in human uterine endometrium: Their potential relevance to reproductive medicine. Fertil. Steril. 1994, 61, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, S.; Harada, T.; Mitsunari, M.; Iwabe, T.; Sakamoto, Y.; Tsukihara, S.; Iba, Y.; Horie, S.; Terakawa, N. Hepatocyte growth factor/Met system promotes endometrial and endometriotic stromal cell invasion via autocrine and paracrine pathways. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice, L.C. Elucidating endometrial function in the post-genomic era. Hum. Reprod. Update 2003, 9, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukku, V.R.; Stancel, G.M. Regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor by estrogen. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 9820–9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansard, L.J.; Healy-Gardner, B.E.; Drapkin, A.T.; Bentley, R.C.; McLachlan, J.A.; Walmer, D.K. Human endometrial transforming growth factor-alpha: A transmembrane, surface epithelial protein that transiently disappears during the midsecretory phase of the menstrual cycle. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 1997, 4, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, J.; Fukaya, T.; Murakami, T.; Yoshida, H.; Yajima, A. Increased secretion of hepatocyte growth factor by eutopic endometrial stromal cells in women with endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1997, 68, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chegini, N.; Rossi, M.J.; Masterson, B.J. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and EGF and PDGF beta-receptors in human endometrial tissue: Localization and in vitro action. Endocrinology 1992, 130, 2373–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangha, R.K.; Li, X.F.; Shams, M.; Ahmed, A. Fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 is a critical component for endometrial remodeling: Localization and expression of basic fibroblast growth factor and FGF-R1 in human endometrium during the menstrual cycle and decreased FGF-R1 expression in menorrhagia. Lab. Investig. 1997, 77, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gargett, C.E.; Chan, R.W.; Schwab, K.E. Hormone and growth factor signaling in endometrial renewal: Role of stem/progenitor cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2008, 288, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, T.; Masuda, H.; Ono, M.; Kajitani, T.; Yoshimura, Y. Human uterine stem/progenitor cells: Their possible role in uterine physiology and pathology. Reproduction 2010, 140, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beier-Hellwig, K.; Alfer, J.; Müller-Schöttle, F.; Crommelinck, D.; Karl, C.; Sterzik, K.; Beier, H.M. Das Endometrium und sein “Implantationsfenster”. Reproduktionsmedizin 2001, 17, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Q.; Jin, L.P. Ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization alters the protein profile expression in endometrial secretion. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 6, 1964–1971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alexandra, J.H.; Bryn, E.W.; Eric, S.S.; David, K.G. Ovarian stimulation protocols: Impact on oocyte and endometrial quality and function. Fertil. Steril. 2025, 123, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Conejero, J.A.; Simón, C.; Pellicer, A.; Horcajadas, J.A. Is ovarian stimulation detrimental to the endometrium? Reprod. Biomed. Online 2007, 15, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Gao, W.; Li, D. Recurrent implantation failure: A comprehensive summary from etiology to treatment. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 13, 1061766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Garcia, J.; Kolp, L.; Cheadle, C.; Rodriguez, A.; Vlahos, N.F. The impact of luteal phase support on gene expression of extracellular matrix protein and adhesion molecules in the human endometrium during the window of implantation following controlled ovarian stimulation with a GnRH antagonist protocol. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, J.D.; Kempers, R.D. Citation classics: Most-cited articles from Fertility and Sterility. Fertil. Steril. 1987, 47, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, A.A.; Elberger, L.; Borghi, M.; Calamera, J.C.; Chemes, H.; Doncel, G.F.; Kliman, H.; Lema, B.; Lustig, L.; Papier, S. Endometrial dating and determination of the window of implantation in healthy fertile women. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 73, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessey, B.A.; Castelbaum, A.J.; Wolf, L.; Greene, W.; Paulson, M.; Meyer, W.R.; Fritz, M.A. Use of integrins to date the endometrium. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 73, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutifaris, C.; Myers, E.R.; Guzick, D.S.; Diamond, M.P.; Carson, S.A.; Legro, R.S.; McGovern, P.G.; Schlaff, W.D.; Carr, B.R.; Steinkampf, M.P.; et al. NICHD National Cooperative Reproductive Medicine Network. Histological dating of timed endometrial biopsy tissue is not related to fertility status. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 82, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, M.J.; Meyer, W.R.; Zaino, R.J.; Lessey, B.A.; Novotny, D.B.; Ireland, K.; Zeng, D.; Fritz, M.A. A critical analysis of the accuracy, reproducibility, and clinical utility of histologic endometrial dating in fertile women. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 81, 1333–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez-Morales, F.J.; Gamboa-Domínguez, A.; Vital-Reyes, V.S.; Hinojosa-Cruz, J.C.; Mendoza-Rodríguez, C.A.; García-Carrancá, A.; Cerbón, M. Differential expression of functionality markers in mid-secretory endometrium of infertile women under treatment with ovulation-inducing agents. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 171, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiong, Z.; Jie, H.; Yonggang, W.; Bin, X.; Jing, Z.; Yanping, L. Clinical validation of pinopode as a marker of endometrial receptivity: A randomized controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 513–517.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentin-Ley, U.; Sjögren, A.; Nilsson, L.; Hamberger, L.; Larsen, J.F.; Horn, T. Presence of uterine pinopodes at the embryo-endometrial interface during human implantation in vitro. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, S.M.; Gayer, N.; Hosie, M.J.; Murphy, C.R. Human uterodomes (pinopods) do not display pinocytotic function. Hum. Reprod. 2002, 17, 1980–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikas, G. Endometrial receptivity: Changes in cell-surface morphology. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2000, 18, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardo, L.G.; Sabatini, L.; Rai, R.; Nardo, F. Pinopode expression during human implantation. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2002, 101, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikas, G.; Aghajanova, L. Endometrial pinopodes: Some more understanding on human implantation? Reprod. Biomed. Online 2002, 4, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gearing, D.P. The leukemia inhibitory factor and its receptor. Adv. Immunol. 1993, 53, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, P.; Salamonsen, L.A.; Manuelpillai, U.; Dimitriadis, E. Interleukin 11 inhibits human trophoblast invasion indicating a likely role in the decidual restraint of trophoblast invasion during placentation. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 80, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fukui, Y.; Hirota, Y.; Aikawa, S.; Ishizawa, C.; Iida, R.; Kaku, T.; Hirata, T.; Akaeda, S.; Hiraoka, T.; Matsuo, M.; et al. Uterine Receptivity is Reflected by LIF Expression in the Cervix. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.L. The role of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and other cytokines in regulating implantation in mammals. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1994, 734, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.R.; Cheng, J.G.; Shatzer, T.; Sewell, L.; Hernandez, L.; Stewart, C.L. Leukemia inhibitory factor can substitute for nidatory estrogen and is essential to inducing a receptive uterus for implantation but is not essential for subsequent embryogenesis. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 4365–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogiagis, D.; Marsh, M.M.; Fry, R.C.; Salamonsen, L.A. Leukaemia inhibitory factor in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle. J. Endocrinol. 1996, 148, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, E.; Salamonsen, L.A.; Robb, L. Expression of interleukin-11 during the human menstrual cycle: Coincidence with stromal cell decidualization and relationship to leukaemia inhibitory factor and prolactin. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2000, 6, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghajanova, L.; Stavreus-Evers, A.; Nikas, Y.; Hovatta, O.; Landgren, B.M. Coexpression of pinopodes and leukemia inhibitory factor, as well as its receptor, in human endometrium. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 79, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghajanova, L. Update on the role of leukemia inhibitory factor in assisted reproduction. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 22, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghajanova, L. Leukemia inhibitory factor and human embryo implantation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1034, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, E.; Menkhorst, E.; Salamonsen, L.A.; Paiva, P. Review: LIF and IL11 in trophoblast-endometrial interactions during the establishment of pregnancy. Placenta 2010, 31, S99–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegra, A.; Marino, A.; Coffaro, F.; Lama, A.; Rizza, G.; Scaglione, P.; Sammartano, F.; Santoro, A.; Volpes, A. Is there a uniform basal endometrial gene expression profile during the implantation window in women who became pregnant in a subsequent ICSI cycle? Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 2549–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegra, A.; Marino, A.; Peregrin, P.C.; Lama, A.; García-Segovia, A.; Forte, G.I.; Núñez-Calonge, R.; Agueli, C.; Mazzola, S.; Volpes, A. Endometrial expression of selected genes in patients achieving pregnancy spontaneously or after ICSI and patients failing at least two ICSI cycles. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2012, 25, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makker, A.; Tandon, I.; Goel, M.M.; Singh, M.; Singh, M.M. Effect of ormeloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, on biomarkers of endometrial receptivity and pinopode development and its relation to fertility and infertility in Indian subjects. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 2298–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, R.E.; Jessmon, P.; Coutifaris, C.; Kruger, M.; Myers, E.R.; Ali-Fehmi, R.; Carson, S.A.; Legro, R.S.; Schlaff, W.D.; Carr, B.R.; et al. Reproductive Medicine Network. High throughput, cell type-specific analysis of key proteins in human endometrial biopsies of women from fertile and infertile couples. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gonzalez, M.; Neufeld, J.; Reimann, K.; Wittmann, S.; Samalecos, A.; Wolf, A.; Bamberger, A.M.; Gellersen, B. Expansion of human trophoblastic spheroids is promoted by decidualized endometrial stromal cells and enhanced by heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor and interleukin-1 β. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 17, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrot-Applanat, M.; Ancelin, M.; Buteau-Lozano, H.; Meduri, G.; Bausero, P. Ovarian steroids in endometrial angiogenesis. Steroids 2000, 65, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugino, N.; Kashida, S.; Karube-Harada, A.; Takiguchi, S.; Kato, H. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle and in early pregnancy. Reproduction 2002, 123, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Acharya, N.; Shukla, S.; Shrivastava, D.; Sharma, G. Comparative study of endometrial & subendometrial angiogenesis in unexplained infertile versus normal fertile women. Indian J. Med. Res. 2021, 154, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelian Frank, D.; Yang, Y.; Hirata, J.D.; Schultz, J.F.; Armant, D.R. Molecular interactions between fibronectin and integrins during mouse blastocyst outgrowth. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1995, 41, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes Richard, O. Integrins: Bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 2002, 110, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apparao, K.B.; Murray, M.J.; Fritz, M.A.; Meyer, W.R.; Chambers, A.F.; Truong, P.R.; Lessey, B.A. Osteopontin and its receptor alphavbeta(3) integrin are coexpressed in the human endometrium during the menstrual cycle but regulated differentially. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 4991–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessey, B.A. Two pathways of progesterone action in the human endometrium: Implications for implantation and contraception. Steroids 2003, 68, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somkuti, S.G.; Yuan, L.; Fritz, M.A.; Lessey, B.A. Epidermal growth factor and sex steroids dynamically regulate a marker of endometrial receptivity in Ishikawa cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997, 82, 2192–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daftary, G.S.; Troy, P.J.; Bagot, C.N.; Young, S.L.; Taylor, H.S. Direct regulation of beta3-integrin subunit gene expression by HOXA10 in endometrial cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002, 16, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumbiner, B.M. Cell adhesion: The molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell 1996, 84, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, O.; Korn, R.; McLaughlin, J.; Ohsugi, M.; Herrmann, B.G.; Kemler, R. Nuclear localization of beta-catenin by interaction with transcription factor LEF-1. Mech. Dev. 1996, 59, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riethmacher, D.; Brinkmann, V.; Birchmeier, C. A targeted mutation in the mouse E-cadherin gene results in defective preimplantation development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fujimoto, J.; Ichigo, S.; Hori, M.; Tamaya, T. Alteration of E-cadherin, alpha- and beta-catenin mRNA expression in human uterine endometrium during the menstrual cycle. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 1996, 10, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poncelet, C.; Leblanc, M.; Walker-Combrouze, F.; Soriano, D.; Feldmann, G.; Madelenat, P.; Scoazec, J.Y.; Daraï, E. Expression of cadherins and CD44 isoforms in human endometrium and peritoneal endometriosis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2002, 81, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Armant, D.R.; Bagchi, M.K.; Bagchi, I.C. Calcitonin down-regulates E-cadherin expression in rodent uterine epithelium during implantation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 46447–46455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.Q.; Zhu, L.J.; Bagchi, M.K.; Bagchi, I.C. Progesterone stimulates calcitonin gene expression in the uterus during implantation. Endocrinology 1994, 135, 2265–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.J.; Cullinan-Bove, K.; Polihronis, M.; Bagchi, M.K.; Bagchi, I.C. Calcitonin is a progesterone-regulated marker that forecasts the receptive state of endometrium during implantation. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 3923–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Zhu, L.J.; Polihronis, M.; Cameron, S.T.; Baird, D.T.; Schatz, F.; Dua, A.; Ying, Y.K.; Bagchi, M.K.; Bagchi, I.C. Progesterone induces calcitonin gene expression in human endometrium within the putative window of implantation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 4443–4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, H.C.; Shiozawa, T.; Miyamoto, T.; Kashima, H.; Feng, Y.Z.; Kurai, M.; Konishi, I. Immunohistochemical expression of E-cadherin and β-catenin in the normal and malignant human endometrium: An inverse correlation between E-cadherin and nuclear β-catenin expression. Anticancer. Res. 2004, 24, 3843–3850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsuzaki, S.; Darcha, C.; Maleysson, E.; Canis, M.; Mage, G. Impaired down-regulation of E-cadherin and beta-catenin protein expression in endometrial epithelial cells in the mid-secretory endometrium of infertile patients with endometriosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 3437–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindhard, A.; Bentin-Ley, U.; Ravn, V.; Islin, H.; Hviid, T.; Rex, S.; Bangsbøll, S.; Sørensen, S. Biochemical evaluation of endometrial function at the time of implantation. Fertil. Steril. 2002, 78, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meseguer, M.; Aplin, J.D.; Caballero-Campo, P.; O’Connor, J.E.; Martín, J.C.; Remohí, J.; Pellicer, A.; Simón, C. Human endometrial mucin MUC1 is up-regulated by progesterone and down-regulated in vitro by the human blastocyst. Biol. Reprod. 2001, 64, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aplin, J.D. MUC-1 glycosylation in endometrium: Possible roles of the apical glycocalyx at implantation. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessey Bruce, A. Assessment of endometrial receptivity. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, N.A.; Li, T.C.; Devine, P.L.; Graham, R.A.; Saravelos, H.; Aplin, J.D. MUC1 in secretory phase endometrium: Expression in precisely dated biopsies and flushings from normal and recurrent miscarriage patients. Hum. Reprod. 1995, 10, 2655–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, A.K.; Nair, A.; Binkley, P.A.; Tekmal, R.; Schenken, R.S. Inhibition of CD44 N-and O-linked glycosylation decreases endometrial cell lines attachment to peritoneal mesothelial cells. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 823–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Swann, H.R.; Aplin, J.D.; Seif, M.W.; Kimber, S.J.; Elstein, M. CD44 is expressed throughout pre-implantation human embryo development. Hum. Reprod. 1995, 10, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyama-Sorimachi, N.; Sorimachi, H.; Tobita, Y.; Kitamura, F.; Yagita, H.; Suzuki, K.; Miyasaka, M. A novel ligand for CD44 is serglycin, a hematopoietic cell lineage-specific proteoglycan. Possible involvement in lymphoid cell adherence and activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 7437–7444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoadley, M.E.; Seif, M.W.; Aplin, J.D. Menstrual-cycle-dependent expression of keratan sulphate in human endometrium. Biochem. J. 1990, 266, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Graham, J.; Franks, S.; Bonney, R.C. In Vivo and in vitro effects of gamma-linolenic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid on prostaglandin production and arachidonic acid uptake by human endometrium. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat. Acids 1994, 50, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hey, N.A.; Aplin, J.D. Sialyl-Lewis x and Sialyl-Lewis a are associated with MUC1 in human endometrium. Glycoconj. J. 1996, 13, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behzad, F.; Seif, M.W.; Campbell, S.; Aplin, J.D. Expression of two isoforms of CD44 in human endometrium. Biol. Reprod. 1994, 51, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, G.F.; Ashkar, S.; Glimcher, M.J.; Cantor, H. Receptor-ligand interaction between CD44 and osteopontin (Eta-1). Science 1996, 271, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poncelet, C.; Cornelis, F.; Tepper, M.; Sauce, E.; Magan, N.; Wolf, J.P.; Ziol, M. Expression of E- and N-cadherin and CD44 in endometrium and hydrosalpinges from infertile women. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 2909–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tvaroška, I.; Selvaraj, C.; Koča, J. Selectins—The Two Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde Faces of Adhesion Molecules—A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Breindel, M.F.; Singh, M.; Kahn, J. Endometrial Receptivity. 7 June 2023. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Lai, T.H.; Shih, I.M.; Ho, C.L.; Vlahos, N. Expression of endometrial L-selectin ligands at the implantation window. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 82, S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.H.; Zhao, Y.; Shih, I.M.; Ho, C.L.; Bankowski, B.; Vlahos, N. Expression of L-selectin ligands in human endometrium during the implantation window after controlled ovarian stimulation for oocyte donation. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 85, 761–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, S.R.; Yan, Y.; Kumar, M.; Lai, H.L.; Lee, Y.L.; Ng, E.H.; Yeung, W.S.B.; Lee, K.F. Multiomics approaches to uncover endometrial receptivity in embryo implantation: A mini-review. Reprod. Dev. Med. 2024, 8, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, B.R.; Isaacson, P.G. The immunocytochemical distribution of leukocytic subpopulations in human endometrium. Am. J. Pathol. 1987, 127, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marshall, R.J.; Jones, D.B. An immunohistochemical study of lymphoid tissue in human endometrium. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1988, 7, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A. Uterine leukocytes and decidualization. Hum. Reprod. Update 2000, 6, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamonsen, L.A.; Lathbury, L.J. Endometrial leukocytes and menstruation. Hum. Reprod. Update 2000, 6, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yellon, S.M.; Mackler, A.M.; Kirby, M.A. The role of leukocyte traffic and activation in parturition. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2003, 10, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.J.; Greer, M.R.; Young, A.; Boswell, F.; Telfer, J.F.; Cameron, I.T.; Norman, J.E.; Campbell, S. Expression of intercellular adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 in human endometrium: Regulation by interferon-gamma. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 5, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haouzi, D.; Dechaud, H.; Assou, S.; Monzo, C.; de Vos, J.; Hamamah, S. Transcriptome analysis reveals dialogues between human trophectoderm and endometrial cells during the implantation period. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppälä, M.; Koistinen, H.; Koistinen, R.; Chiu, P.C.; Yeung, W.S. Glycosylation related actions of glycodelin: Gamete, cumulus cell, immune cell and clinical associations. Hum. Reprod. Update 2007, 13, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, W.S.; Lee, K.F.; Koistinen, R.; Koistinen, H.; Seppälä, M.; Chiu, P.C. Effects of glycodelins on functional competence of spermatozoa. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2009, 83, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell, A.; Morris, H.R.; Easton, R.L.; Panico, M.; Patankar, M.; Oehniger, S.; Koistinen, R.; Koistinen, H.; Seppala, M.; Clark, G.F. Structural analysis of the oligosaccharides derived from glycodelin, a human glycoprotein with potent immunosuppressive and contraceptive activities. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 24116–24126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, K.H.; Lee, C.L.; Yeung, W.S.; Lee, K.F. Glycodelin suppresses endometrial cell migration and invasion but stimulates spheroid attachment. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2012, 24, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.L.; Pang, P.C.; Yeung, W.S.; Tissot, B.; Panico, M.; Lao, T.T.; Chu, I.K.; Lee, K.F.; Chung, M.K.; Lam, K.K.; et al. Effects of differential glycosylation of glycodelins on lymphocyte survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 15084–15096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hausermann, H.M.; Donnelly, K.M.; Bell, S.C.; Verhage, H.G.; Fazleabas, A.T. Regulation of the glycosylated beta-lactoglobulin homolog, glycodelin [placental protein 14:(PP14)] in the baboon (Papio anubis) uterus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppälä, M.; Koistinen, H.; Koistinen, R.; Hautala, L.; Chiu, P.C.; Yeung, W.S. Glycodelin in reproductive endocrinology and hormone-related cancer. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2009, 160, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppälä, M.; Taylor, R.N.; Koistinen, H.; Koistinen, R.; Milgrom, E. Glycodelin: A major lipocalin protein of the reproductive axis with diverse actions in cell recognition and differentiation. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 401–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeschke, U.; Richter, D.U.; Möbius, B.M.; Briese, V.; Mylonas, I.; Friese, K. Stimulation of progesterone, estradiol and cortisol in trophoblast tumor bewo cells by glycodelin A N-glycans. Anticancer Res. 2007, 27, 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lam, K.K.; Chiu, P.C.; Chung, M.K.; Lee, C.L.; Lee, K.F.; Koistinen, R.; Koistinen, H.; Seppala, M.; Ho, P.C.; Yeung, W.S. Glycodelin-A as a modulator of trophoblast invasion. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 2093–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachmilewitz, J.; Borovsky, Z.; Riely, G.J.; Miller, R.; Tykocinski, M.L. Negative regulation of T cell activation by placental protein 14 is mediated by the tyrosine phosphatase receptor CD45. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 14059–14065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ish-Shalom, E.; Gargir, A.; André, S.; Borovsky, Z.; Ochanuna, Z.; Gabius, H.J.; Tykocinski, M.L.; Rachmilewitz, J. alpha2,6-Sialylation promotes binding of placental protein 14 via its Ca2+-dependent lectin activity: Insights into differential effects on CD45RO and CD45RA T cells. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SundarRaj, S.; Soni, C.; Karande, A.A. Glycodelin A triggers T cell apoptosis through a novel calcium-independent galactose-binding lectin activity. Mol. Immunol. 2009, 46, 3411–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, P.C.; Chung, M.K.; Koistinen, R.; Koistinen, H.; Seppala, M.; Ho, P.C.; Ng, E.H.; Lee, K.F.; Yeung, W.S. Glycodelin-A interacts with fucosyltransferase on human sperm plasma membrane to inhibit spermatozoa-zona pellucida binding. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, P.C.; Tsang, H.Y.; Koistinen, R.; Koistinen, H.; Seppala, M.; Lee, K.F.; Yeung, W.S. The contribution of D-mannose, L-fucose, N-acetylglucosamine, and selectin residues on the binding of glycodelin isoforms to human spermatozoa. Biol. Reprod. 2004, 70, 1710–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, C.; Toth, B.; Brunnhuber, R.; Rampf, E.; Weissenbacher, T.; Santoso, L.; Friese, K.; Jeschke, U. Glycodelin A induces a tolerogenic phenotype in monocyte-derived dendritic cells in vitro. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2008, 60, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beier, H.M.; Beier-Hellwig, K. Molecular and cellular aspects of endometrial receptivity. Hum. Reprod. Update 1998, 4, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauma, S.; Huff, T.; Krystal, G.; Ryan, J.; Takacs, P.; Turner, T. The expression of stem cell factor and its receptor, c-kit in human endometrium and placental tissues during pregnancy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1996, 81, 1261–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsunari, M.; Harada, T.; Tanikawa, M.; Iwabe, T.; Taniguchi, F.; Terakawa, N. The potential role of stem cell factor and its receptor c-kit in the mouse blastocyst implantation. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 5, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharkey, A.M.; Jokhi, P.P.; King, A.; Loke, Y.W.; Brown, K.D.; Smith, S.K. Expression of c-kit and kit ligand at the human maternofetal interface. Cytokine 1994, 6, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, F.; Gadea, B.; Esteban, F.J.; Horcajadas, J.A.; Pellicer, A.; Simón, C. Comparative protein-profile analysis of implanted versus non-implanted human blastocysts. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 1993–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabanelli, S.; Tang, B.; Gurpide, E. In Vitro decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1992, 42, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, S.D.; Roche, J.F.; Forde, N. Temporal changes in endometrial gene expression and protein localization of members of the IGF family in cattle: Effects of progesterone and pregnancy. Physiol. Genom. 2012, 44, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.G.; Mazella, J.; Tseng, L. Activation of the human IGFBP-1 gene promoter by progestin and relaxin in primary culture of human endometrial stromal cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1994, 104, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibuya, H.; Sakai, K.; Kabir-Salmani, M.; Wachi, Y.; Iwashita, M. Polymerization of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) potentiates IGF-I actions in placenta. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011, 226, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving, J.A.; Lala, P.K. Functional role of cell surface integrins on human trophoblast cell migration: Regulation by TGF-beta, IGF-II, and IGFBP-1. Exp. Cell Res. 1995, 217, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Taylor, H.S.; Akbas, G.E.; Foucher, I.; Trembleau, A.; Jaffe, R.C.; Fazleabas, A.T.; Unterman, T.G. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 promoter activity by FKHR and HOXA10 in primate endometrial cells. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 68, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Fazleabas, A.T. Uterine receptivity and implantation: The regulation and action of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), HOXA10 and forkhead transcription factor-1 (FOXO-1) in the baboon endometrium. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2004, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fogle, R.H.; Li, A.; Paulson, R.J. Modulation of HOXA10 and other markers of endometrial receptivity by age and human chorionic gonadotropin in an endometrial explant model. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Horst, P.H.; Wang, Y.; van der Zee, M.; Burger, C.W.; Blok, L.J. Interaction between sex hormones and WNT/β-catenin signal transduction in endometrial physiology and disease. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 358, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainio, S.; Heikkilä, M.; Kispert, A.; Chin, N.; McMahon, A.P. Female development in mammals is regulated by Wnt-4 signalling. Nature 1999, 397, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mericskay, M.; Kitajewski, J.; Sassoon, D. Wnt5a is required for proper epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the uterus. Development 2004, 131, 2061–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Kannan, A.; Das, A.; Demayo, F.J.; Hornsby, P.J.; Young, S.L.; Taylor, R.N.; Bagchi, M.K.; Bagchi, I.C. WNT4 acts downstream of BMP2 and functions via β-catenin signaling pathway to regulate human endometrial stromal cell differentiation. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tulac, S.; Overgaard, M.T.; Hamilton, A.E.; Jumbe, N.L.; Suchanek, E.; Giudice, L.C. Dickkopf-1, an inhibitor of Wnt signaling, is regulated by progesterone in human endometrial stromal cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Tan, Y.; Li, M.; Dey, S.K.; Das, S.K. Canonical Wnt signaling is critical to estrogen-mediated uterine growth. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004, 18, 3035–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hayashi, K.; Burghardt, R.C.; Bazer, F.W.; Spencer, T.E. WNTs in the ovine uterus: Potential regulation of periimplantation ovine conceptus development. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 3496–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hanifi-Moghaddam, P.; Hanekamp, E.E.; Kloosterboer, H.J.; Franken, P.; Veldscholte, J.; van Doorn, H.C.; Ewing, P.C.; Kim, J.J.; Grootegoed, J.A.; et al. Progesterone inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in normal endometrium and endometrial cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 5784–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulac, S.; Nayak, N.R.; Kao, L.C.; Van Waes, M.; Huang, J.; Lobo, S.; Germeyer, A.; Lessey, B.A.; Taylor, R.N.; Suchanek, E.; et al. Identification, characterization, and regulation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in human endometrium. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 3860–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, J.S.; Poehlmann, T.G.; Schleussner, E.; Markert, U.R. Trophoblast invasion: The role of intracellular cytokine signalling via signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Hum. Reprod. Update 2008, 14, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.R.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, B.S.; Chung, T.W.; Kim, K.J.; Joo, J.K.; Ryu, D.; Bae, S.J.; Ha, K.T. Paeoniflorin Enhances Endometrial Receptivity through Leukemia Inhibitory Factor. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.L.; Stoikos, C.; Findlay, J.K.; Salamonsen, L.A. TGF-beta superfamily expression and actions in the endometrium and placenta. Reproduction 2006, 132, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, E.; White, C.A.; Jones, R.L.; Salamonsen, L.A. Cytokines, chemokines and growth factors in endometrium related to implantation. Hum. Reprod. Update 2005, 11, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makrigiannakis, A.; Minas, V.; Kalantaridou, S.N.; Nikas, G.; Chrousos, G.P. Hormonal and cytokine regulation of early implantation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 17, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoikos, C.J.; Harrison, C.A.; Salamonsen, L.A.; Dimitriadis, E. A distinct cohort of the TGFbeta superfamily members expressed in human endometrium regulate decidualization. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, H.K.; Bergmann, S.; Pandolfi, P.P. Cytoplasmic PML function in TGF-beta signalling. Nature 2004, 431, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, H.; Kishore, A.H.; Lindqvist, A.; Rogers, D.E.; Word, R.A. Transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) and progesterone regulate matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) in human endometrial stromal cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E888–E897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kane, N.M.; Jones, M.; Brosens, J.J.; Kelly, R.W.; Saunders, P.T.; Critchley, H.O. TGFβ1 attenuates expression of prolactin and IGFBP-1 in decidualized endometrial stromal cells by both SMAD-dependent and SMAD-independent pathways. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tabibzadeh, S. Isolation, characterization, and function of EBAF/LEFTY B: Role in infertility. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1221, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Naidu, D.; Hearing, P.; Handwerger, S.; Tabibzadeh, S. LEFTY, a member of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily, inhibits uterine stromal cell differentiation: A novel autocrine role. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Salker, M.S.; Christian, M.; Steel, J.H.; Nautiyal, J.; Lavery, S.; Trew, G.; Webster, Z.; Al-Sabbagh, M.; Puchchakayala, G.; Föller, M.; et al. Deregulation of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1 in the endometrium causes reproductive failure. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1509–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, K.; Takahashi, T.; Mitsui, J.; Kuroda, K.; Hiraoka, K.; Kawai, K. A case of discrepancy between three ERA tests in a woman with repeated implantation failure complicated by chronic endometritis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goharitaban, S.; Abedelahi, A.; Hamdi, K.; Khazaei, M.; Esmaeilivand, M.; Niknafs, B. Role of endometrial microRNAs in repeated implantation failure (mini-review). Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 936173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Du, B.; Chen, X.; Chen, M. Correlation of MicroRNA-31 with Endometrial Receptivity in Patients with Repeated Implantation Failure of In Vitro Fertilization and Embryo Transfer. Organogenesis 2025, 21, 2460263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, W.; Chiu, P.C.N.; Yeung, W.S.B. Mir-let-7a/g Enhances Uterine Receptivity via Suppressing Wnt/β-Catenin Under the Modulation of Ovarian Hormones. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.L.; Kang, Y.; Jeong, D.U.; Lee, D.C.; Jeon, H.J.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, S.K.; Han, A.R.; Kang, J.; Park, S.R. The miR-182-5p/NDRG1 Axis Controls Endometrial Receptivity through the NF-κB/ZEB1/E-Cadherin Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ju, Y.; Lei, H.; Dong, J.; Jin, N.; Lu, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, X. MiR-135a-5p regulates window of implantation by suppressing pinopodes development and decidualization of endometrial stromal cells. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2024, 41, 1645–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Hu, D.; Ye, Y.; Mu, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, Y. Identification of serum small non-coding RNA as biomarkers for endometrial receptivity. Genomics 2025, 117, 111002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecule | Family | Function | Expression Pattern | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIF | Cytokine | Promotes embryo adhesion and trophoblast differentiation | Peaks during the WOI | [71,72,73,74] |

| VEGF | Growth factor | Promotes angiogenesis, vascularization, embryo implantation | Peaks in mid-luteal phase | [86,87,88] |

| EGF/HBEGF | Growth factor | Regulates epithelial cell growth and endometrial remodeling | Increases during mid-luteal phase | [92,93] |

| Integrin αvβ3 | Integrin (CAM) | Mediates adhesion between trophoblast and endometrial epithelium | Reduced during proliferative phase | [91,92,93] |

| Selectin L | Selection (CAM) | Facilitates initial tethering of blastocyst to endometrium | Expressed on trophoblast | [120,121] |

| CD44 | Hyaluronan receptor (CAM) | Aids in cell adhesion | Expressed in epithelium and in stromal cells | [111,117,118] |

| E-cadherin | Cadherin (CAM) | Maintains epithelial integrity for embryo attachment | Downregulated locally at implantation site | [105] |

| Ig superfamily | Facilitates immune cell adhesion, support embryo- endometrium contact | Upregulated during The secretory phase | [125,126,127,128,129,130] | |

| ICAM-1 | (CAM) | |||

| Glycopritein | Prevents adhesion | Downregulated at site of embryo attachment | [107,108,109] | |

| MUC1 | (anti-adhesive) | |||

| Ig superfamily | Supports interaction between blastocyst and the endometrium | Expressed in the proliferative and secretory phase and in blastocysts | [131] | |

| ALCAM | (CAM) |

| Molecule | Family | Function(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycodelin (GdA) | Glycoprotein isoform | Modulates trophoblast invasion, maternal immune response | [132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148] |

| Stem cell factor (SCF) | Cytokine | Promotes trophoblast growth, embryo expansion, via interaction with c-kit | [149,150,151,152] |

| CD34 | Transmembrane sialomucin | Supports the origin of decidual NK cells, immune modulation, and angiogenesis | [153,154,155] |

| IGFBP-1 and IGF-1R | IGF family | Regulates trophoblast invasion, placental function, enhances IGF-1 activity under progesterone and FOXO1 stimulation | [154,155,156,157,158] |

| Homeobox genes (HOXA 10) | Transcription factor | Regulates decidualization markers and molecular responses of endometrium to hormonal stimulus | [159,160] |

| Molecule | Pathway/Nature | Function(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-catenin | Wnt signaling pathway | Regulates implantation, trophoblast invasion, and dysregulation leading to uterine disorders | [161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169] |

| Wnt 4 Wnt 5A Wnt 7A | Wnt signaling pathway | Mullerian duct initiation | [162,163] |

| Posterior outgrowth during female tract development Mullerian duct differentiation | |||

| DKK1 | Wnt signaling molecule | Inhibits Wnt signaling, maintains endometrial homeostasis | [168] |

| LIF | Cytokine | Enhances endometrial receptivity, regulates trophoblast invasion via JAK/STAT3 pathway | [170,171] |

| TGFβ (1,2,3) | TGFβ superfamily | Modulates immune tolerance, regulates implantation-related molecules, and supports decidualization | [172,173,174,175] |

| BMP (2,4,7) | Bone morphogenetic proteins of TGFβ superfamily | Promote decidualization and regulate endometrial remodeling | [175] |

| LEFTY (EBAF) | Endometrial bleeding- associated factor of TGFβ superfamily | Inhibits decidual proteins, impairs implantation when overexpressed, regulates decidual differentiation | [179,180] |

| SGK1 | Kinase | Involved in epithelial ion transport, dysregulation linked to recurrent pregnancy loss via oxidative stress | [181] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maldonado Rosas, I.; Mottola, F.; Palmieri, I.; Ibello, L.; Kalita, J.C.; Roychoudhury, S. Molecular Biomarkers of Endometrial Function and Receptivity in Natural and Stimulated Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Cycles. Reprod. Med. 2026, 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed7010002

Maldonado Rosas I, Mottola F, Palmieri I, Ibello L, Kalita JC, Roychoudhury S. Molecular Biomarkers of Endometrial Function and Receptivity in Natural and Stimulated Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Cycles. Reproductive Medicine. 2026; 7(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed7010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaldonado Rosas, Israel, Filomena Mottola, Ilaria Palmieri, Lorenzo Ibello, Jogen C. Kalita, and Shubhadeep Roychoudhury. 2026. "Molecular Biomarkers of Endometrial Function and Receptivity in Natural and Stimulated Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Cycles" Reproductive Medicine 7, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed7010002

APA StyleMaldonado Rosas, I., Mottola, F., Palmieri, I., Ibello, L., Kalita, J. C., & Roychoudhury, S. (2026). Molecular Biomarkers of Endometrial Function and Receptivity in Natural and Stimulated Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Cycles. Reproductive Medicine, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed7010002