Abstract

We carried out a comprehensive literature search for publications on the range of vascular events that have been linked to adenomyosis. This covered vascular diseases, blood coagulation disorders, thrombosis, hypercoagulation, stroke (embolic, ischemic, thrombotic, hemorrhagic), cerebrovascular episodes, cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage) and renal disease. This review covers 63 articles. Nineteen articles reported clinical manifestations of intravascular thrombosis in women with adenomyosis. Eleven publications were identified that reported on cerebral involvement and adenomyosis, including cases of ischemic stroke or infarction. Dysregulation primarily seems to occur via local factors leading to altered angiogenesis. Five case reports were identified that reported on various vascular complications attributed to the presence of adenomyosis. The search also identified reports of cerebral complications in women with adenomyosis. Through a secondary search, we identified publications dealing with a possible connection between cardiac complications and renal pathology, which the authors attributed to adenomyosis. Vascular involvement in adenomyosis is documented in rare cases by the presence of endometrial tissue in myometrial vessels both in menstrual and non-menstrual uteri. Women with adenomyosis have a higher platelet count, a shorter thrombin and prothrombin time and an activated partial thromboplastin time. These findings has been applied to attempts to identify therapies for adenomyosis based on targeting the vasculature, but the existence of a link between the two conditions is under question for several reasons: only case reports (or very small series) have been published; all published cases come from one region of the world (the Far East); the published literature does not contain objective proof of a causal relationship between the two pathologies, except for the elevation of some markers. In summary, it is not possible to conclude that the presence of adenomyosis has a pathogenetic role in causing vascular events, first and foremost because available evidence consists mostly of case reports.

1. Introduction

For decades, adenomyosis has been seen as an ‘elusive disease’. It is now possible to make a diagnosis using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), 2D or 3D ultrasound (2D or 3D-US). It is nevertheless important to reiterate that definitive diagnosis remains a challenge, not least because of the lack of agreement on the cut-off point for histological diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of adenomyosis remains uncertain, and several theories have been put forward. The role of platelets in adenomyotic lesions deserves attention: following menstrual bleeding, in which adenomyotic foci also take part, the lesions undergo a process of recurrent tissue injury and repair (ReTIAR) that in turn initiates a number of key molecular events, with platelets acting as first responders eliciting subsequent tissue repair [1,2].

Periodic platelet activation can have consequences beyond the local injury followed by ReTIAR. Local activation could have systemic consequences, as evidenced by reports of hypercoagulability in patients with endometriosis and adenomyosis [3].

Endometriotic stromal cells, and likely adenomyotic stromal cells, produce platelet-activating factors such as thromboxane A2 and thrombin [4], possibly establishing a microenvironment that is conducive to constant platelet activation and increased vascular permeability. Whether platelet activation differs between women with and without adenomyosis remains to be examined. It is uncertain if systemic vascular pathology is associated with adenomyosis. PubMed lists (as of 10 August 2024) 69 articles on “endometriosis and atherosclerosis” and only 2 for “adenomyosis and atherosclerosis”, with only 1 of these 2 articles being relevant. There are numerous case reports suggesting increased intravascular coagulation leading to thrombotic complications and even stroke in women with adenomyosis.

It is for this reason that a comprehensive search for the frequency and seriousness of complications involving increased coagulation occurring in women with adenomyosis can be informative. Hence, we engaged in this review.

2. Search Methodology

This review included all studies without any restriction on publication year.

Data Identification and Selection

During July 2024, a literature search was carried out using the electronic databases PubMed, MEDLINE and Scopus. The following terms were used in the search: [Adenomyosis AND (cerebrovascular disorders OR vascular pathology, OR vascular disease, OR blood coagulation disorders, OR thrombosis, OR hypercoagulation, OR stroke, OR embolic stroke, OR ischemic stroke, OR thrombotic stroke, OR hemorrhagic stroke, OR cerebral infarction, OR cerebrovascular disorders, OR cerebral hemorrhage)].

All original reports, reviews, case series and case reports were considered for inclusion, and their reference lists were analyzed to identify other potential studies. Review articles, editorials and letters were excluded. Two independent reviewers (PB and IR) identified and selected the studies. Differences were resolved by a third author (GB).

3. Results

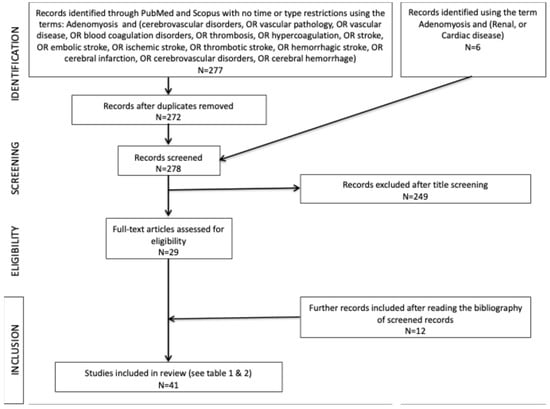

The search identified 277 studies; 5 (1.8%%) were removed as duplicates and 249 (89.9%) were excluded after title and abstract evaluation (Figure 1). Twelve studies were added after reading the reference lists of the identified studies. Forty-one articles were tabulated for comparison at the end of the selection process.

Figure 1.

Flow chart summarizing the paper selection process.

This review included all studies without any restriction on publication year. We identified additional publications based on our review of the published literature; thus, in total, this review includes 41 relevant articles (see the tables).

3.1. Coagulation Disorders in Adenomyosis

Nineteen articles reported clinical manifestations of peripheral vascular thrombosis or deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) in women with adenomyosis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies reporting on deranged coagulation and/or DVT in women with adenomyosis. DVT: deep-vein thrombosis; CA125: cancer antigen 125; DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation.

The first evidence of localized platelet aggregation in adenomyotic lesions was presented some 10 years ago [24,25] but not confirmed in a recent study [26]. An explanation for this discrepancy has been provided in a recent review [2]. Another piece of evidence that suggests the role of platelets in adenomyosis is the overexpression of the tissue factor (TF) [27,28]. Whether the local effects have wider clinical implications is a distinct, yet unanswered, question.

There are numerous case reports documenting thromboembolism in women with adenomyosis [14]. The case report by Okuda et al. [14] was of a pulmonary embolus in a woman receiving combined contraception, which is itself a risk factor for venous thromboembolism, but the article was concerned with anesthetic management during the removal of the uterus in the acute phase as it was considered to be the source of the thrombi. Table 1 includes articles that report cases of intravascular coagulation that may have relevance to platelet or coagulation function in women who have concomitant adenomyosis.

It has been proposed that soluble serum carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA-125) plays a vital role in coagulation [29]. Consistent with this notion, women with adenomyosis have a higher platelet count, a shorter thrombin time (TT) and an activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) compared to women without adenomyosis [30]. Another study reported shorter prothrombin time (PT) and the negative correlation between uterine size and APTT/TT [22]. Women with adenomyosis had significantly higher platelet counts than controls, and had shorter PT [18]. In addition, in women with adenomyosis, APTT and TT were significantly shorter in those who had anemia due to heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) than those who did not [22]. However, increased coagulability is a feature in women with anemia, which can accompany adenomyosis and/or fibroids. This was not considered a confounding factor in the case reports.

In a retrospective study, Yang et al. [30] compared a group with adenomyosis with two control groups: women with fibroids and women with carcinoma in situ (CIN). Women with adenomyosis were far more likely to have menorrhagia and anemia and to have elevated CA128 and CA19.9. The TT values were 17.7 (17.1–18.4), 17.9 (17.3–18.5), and 18.2 (17.65–18.55) s in the adenomyosis, fibroid and CIN groups, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference between the adenomyosis and the fibroid and carcinoma groups. The corresponding values for the APTT were 26.7 (25.3–28.0), 26.75 (25.4–28.5) and 27.6 (26.25–28.95) s, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference between the adenomyosis and the carcinoma group, but not the fibroid group. Whilst the clinical significance of the identified differences is unclear, it is unknown if the difference can be accounted for by anemia. The study did not comment on the use of tranexamic acid by the various groups. It is also unclear how to account for the increased incidence of menorrhagia in the presence of apparent increased coagulability.

Women with adenomyosis who experienced HMB are in a hypercoagulable state manifesting as a higher platelet count and shorter PT and APTT, as compared to women without adenomyosis [3]. In addition, within the adenomyosis patients who complained of HMB, women who reported excessive menstrual blood loss had significantly higher plasma D-dimer (DD) and fibrin degradation product (FDP) levels but shorter APTT and lower fibrinogen levels than those who complained of moderate or heavy menstrual blood loss [3].

There are several case reports documenting the systemic thrombotic consequences in patients with adenomyosis who developed disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [15,17].

However, adenomyosis is not a rare disease; thus, proof of a link between adenomyosis and clinically significant coagulopathy could not be derived merely from case reports. Most case reports come from the Far East (Japan, China and Korea) and some feature significantly enlarged uteri, which raises a question as to whether these individuals had unique features. The articles themselves have not addressed this feature or the possibility that a mass effect compressing the pelvic vessels increases thrombotic risk. It is worth the mention that whilst adenomyosis is associated with uterine enlargement, massive uterine enlargement is more likely to be encountered in women with fibroids. The vast majority of the reports did not include a detailed description of adenomyosis, of concomitant pathology or of the use of medication that could increase the risk of thrombosis. Nevertheless, awareness of a possible association in women with significantly elevated CA125 is warranted [31].

3.2. Vasculopathies and Adenomyosis

We identified 11 relevant publications under this heading and 7 other articles reported on cases of ischemic stroke or infarction.

In 2000, Hickey and Fraser [32] summarized evidence that disruption to both the regulation of endometrial vascular growth and of its function has been found to be associated with disturbances to menstrual bleeding. Dysregulation primarily occurs via local factors, and in the case of adenomyosis, its presence is commonly evidenced by menstrual disturbance, while alterations to vascular distribution and structure suggest altered angiogenesis.

3.2.1. Vascular Involvement in Adenomyosis

The presence of endometrial tissue in myometrial vessels was identified first during the menstrual period (e.g., [33]) and subsequently also in non-menstruating uteri. Sahin et al. [34] identified intravascular endometrial tissue in 14/277 hysterectomy specimens from women outside the menstrual phase. All had extensive adenomyosis. They suggested that as perivascular cells proliferate, they may impinge on endothelially intact vascular lumina and become intraluminal. Meenakshi and McCluggage [35] identified vascular involvement in 54/434 (12.4%) uteri with adenomyosis. This ranged from the single- to multiple-vessel involvement of endometrial stroma and, sometimes, glands. In most cases the endothelial lining was intact. There is a positive correlation between endometrial angiogenesis and menstrual disorders, including in women with adenomyosis [36].

COX-2 expression in the endometrium did not vary during the menstrual cycle in the control group or in patients with endometrial polyps but increased during the secretory phase in patients with adenomyosis. There was also an increased expression of MMP-2 in stromal cells and of micro-vessel density (MVD) in adenomyosis foci throughout the cycle [37]. The expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), but not of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-α) and MVD, was increased in the eutopic endometrium in adenomyosis [38]. In the ectopic endometrium the increase in VEGF expression exceeded that of the eutopic mucosa and was accompanied by that of HIF-1α, especially in epithelial cells, and of MVD [38]. Annexin-A2 (ANXA2), a protein that plays a role in regulating cell growth and in signal transduction pathways, was very significantly up-regulated in the ectopic endometrium of women with adenomyosis compared with its eutopic counterpart. Of relevance is the observation that overexpression of ANXA2 was highly correlated with markers of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) [39]. Levels of IL-22 and its receptors IL-22R1 and IL-10R2 in both the eutopic and ectopic endometrium in women with adenomyosis were significantly higher than in controls [40]. Recombinant human IL-22 (rhIL-22) increased IL-22R1 and IL-10R2 levels, promoted the invasiveness of endometrial stromal cells (ESCs), inhibited the expression of metastasis suppressor gene CD82, and stimulated the secretion of IL-8, RANTES (regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted) chemokine, IL-6 and VEGF from ESCs.

3.2.2. Clinical Implications

Targeting abnormal vasculature associated with uterine pathologies could be pursued within therapeutics [32]. This includes blocking dysregulated estrogen-responsive proteins such as ANXA2 in adenomyosis, which would reduce the latter’s proangiogenic capacity [39]. Another potential strategy is inhibiting the crosstalk between vascular endothelial cells and endometrial stromal cells through blocking IL-22 expression [40]. Inhibiting the increased expression of IL-22 receptors IL-22R1 and IL-10R2 in venous endothelial cells (VECs) in ectopic tissue from women with adenomyosis represents another potential treatment option. Administration of rhIL-22 led to an elevation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) without modifying apoptosis [41].

Berberine (BBR), an isoquinoline-derivative alkaloid, was shown to significantly inhibit the proliferation and viability of eutopic and ectopic ESCs, with only a minor effect on normal endometrial stromal cells, thus offering a potential therapeutic effect [42].

3.2.3. Reports of Cases of Increased Coagulability in Adenomyosis

We identified five case reports of various vascular complications attributed to the presence of adenomyosis. The first report from 1991 briefly outlined the history of a patient with adenomyosis who suffered from thrombosis, apparently due to the intravascular invasion of endometriotic tissue [6]. A second article described the case of a woman with hereditary hyper-homocysteinemia, previous myomectomy and repeated DVT leading to the occlusion of the femoral vein and menorrhagia. Adenomyosis was confirmed upon hysterectomy but was not linked to thrombosis [7].

One publication reported a case of adenomyosis complicated by an episode of acute DIC that occurred during menstruation. There were no known predisposing factors, and anticoagulation therapy and supplementation of coagulation factors resulted in rapid improvement [8].

Another report summarized the case of a patient with severe adenomyosis who, following pregnancy termination, suffered from acute, non-septic DIC [18]. There was no evidence of infection, and the hypothesis was formulated that the occurrence of a hemorrhage in the adenomyotic tissue after termination caused inflammation and the release of numerous microthrombi and necrosis in adenomyosis, leading to hypercoagulation, massive fibrinolysis and DIC [18]. It is important to reiterate that most case reports come from the Far East, and many have features that suggest either advanced or atypical disease. Many of the case reports have not included histological confirmation, and none them have included a full description of adenomyosis.

3.3. Cerebral Complications

Whether there is a link between cerebral complications and adenomyosis is contentious. Only case reports or very small series have been published, and all come from the Far East. The published literature does not contain any objective proof of a causal relationship between adenomyosis and vascular complications, except for the elevation of some non-specific markers.

Yamanaka et al. [16] suggested that there was an increased risk of thrombotic disorders in women with adenomyosis with a uterine volume ≥100 cubic centimeters who had elevated soluble fibrin (SF) (a marker of coagulation) and DD (a marker of both coagulation and fibrinolysis), but there was no increased risk found in women without activated fibrinolysis. Nevertheless, their conclusion should be taken with caution as the study lacked a control group.

We identified case reports of cerebral infarction in women with adenomyosis and intracranial venous thrombosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies reporting on cerebral infarction ischemic or embolic stroke or cerebral venous thrombosis in women with adenomyosis. HRT: hormone replacement therapy.

3.3.1. Ischemic Stroke/Infarction

In an early report, adenomyosis with raised D-dimer and CA125 levels were believed to be contributory to an increased risk of thromboembolism [47]. The 59-year-old postmenopausal woman who was receiving HRT had multiple hyperintense cerebral and cerebellar lesions and aortic valve thrombi.

A case of a nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis complicated by cerebral infarction in a woman with adenomyosis was reported in Japan. She presented mitral valve vegetation upon transesophageal echocardiography and a highly elevated CA125 (901 U/mL). The vegetation reduced after treatment by intravenous unfractionated heparin [48].

Three cases of ischemic stroke during menstruation in patients with adenomyosis have been reported [52]. All had elevated CA-125, CA-19-9, and D-Dimer levels during menstruation but these markedly decreased afterwards. The strokes were attributed to nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis, stenosis of the cerebral arteries associated with a hypercoagulable state, and the presence of hyper-viscous mucinous proteins in the adenomyotic lesions [52].

In recent years, attention has been paid to the existence of specific risk factors for stroke in women. A comprehensive review of the association between adenomyosis and ischemic stroke by Yan et al. [59] listed fifteen reports of cases involving patients ranging from 34 to 59 years old. All cases were from Japan, China and Korea. The specific indications for an early diagnosis were fatigue and dizziness during menstruation [59]. Ischemic stroke can occur as part of systemic thromboembolism involving multiple organs and can recur, leading to neurological deterioration. MRI shows multiple hyper-intensive spots in the adenomyotic foci. Elevated soluble fibrin and DD levels during menstruation might indicate a higher risk of thrombotic disorders [59].

In a retrospective study of 470 consecutive women with common non-cancerous gynecologic diseases, 37 had ischemic stroke and 2 had transient ischemic attack (TIA) [63]. Cases were divided based on the etiology of the stroke into the conventional stroke mechanism: CSM (large artery atherosclerosis, small vessel occlusion, cardioembolism, and other determined etiology), or non-CSM (lesions related to hypercoagulability). Six cases were associated with adenomyosis, and the majority had cryptogenic stroke. Adenomyosis was present in one case in the CSM group (15%) and in 5 cases (25%) in the non-CSM group. The study concluded that hyper-coagulability in adenomyosis may play a role in the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke/TIA.

3.3.2. Cerebral Vasa Thrombosis

We identified 7 publications, all from the Far East, reporting a possible causal association between cerebral vascular thromboses and adenomyosis.

One case report was on a woman with massive adenomyosis who developed cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) leading to seizures and loss of consciousness. She had a localized, high-intensity region in the left frontal lobe, as determined upon MRI, abrupt termination of the anterior half of the superior sagittal sinus and a filling defect in part of the left transverse sinus. She had elevated CA-125 and D-Dimer levels. There was no recurrence following resection of the adenomyotic mass [46].

Aiura et al. [54] reported a case of middle cerebral artery occlusion and recurrent cerebral infarction. The woman had heavy uterine bleeding, adenomyosis, a left ovarian tumor, multiple uterine myomas, and old and new bilateral renal infarctions. She developed left hemiparesis, dysarthria and a pulmonary thromboembolism. She underwent endovascular thrombectomy, hysterectomy and ovariectomy. D-Dimers and tumor markers rapidly returned to normal. There were no further ischemic events at 15 months post-hysterectomy. The clinical picture resembled Trousseau’s syndrome, or cancer-associated thrombosis.

A report by Yadav et al. [58] described a 42-year-old woman with a history of menorrhagia secondary to adenomyosis, for which she received a progestin-only pill (with poor compliance). She developed a sudden onset of headaches and seizures and was identified to have a left cortical hematoma with surrounding edema in the temporo-occipital region secondary to cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. She declined a hysterectomy and was commenced on a progestin-only pill, resulting in symptomatic control and no recurrence over the two months of follow-up.

The case by Zhao et al. [53] is of a 34-year-old woman who complained of headache, fever and left limb weakness during the menstrual phase. MRI showed restriction in the middle-right cerebral artery distribution. She was diagnosed with acute infarction in the right basal ganglia and the subcortical region of the right frontotemporal lobe. Two additional cases of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) in young women with adenomyosis were reported by Li et al. [60]. Their literature review identified 25 cases of stroke in women with adenomyosis; however, only 3 were related to CVST. Li et al. pointed to the coexistence in these patients of HMB, anemia and CA-125 elevation [59].

3.4. Cardiac Pathology

Our search identified four publications that suggested a connection between cardiac complications and adenomyosis.

A study of the metabolic parameters and cardiometabolic risk in women with adenomyosis included 96 premenopausal women with an imaging-based diagnosis of adenomyosis and 97 controls. The adenomyosis group had a higher prevalence of raised systolic blood pressure, low HDL-cholesterol and central obesity [65]. One study reported a case of non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis associated with a hypercoagulable state in a woman with adenomyosis [48].

Soeda et al. [45] reported on a 47-year-old woman with menorrhagia, severe anemia and diffuse adenomyosis who complained of dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and loss of consciousness after a red blood cell transfusion. MRI showed multiple right cerebellar and bilateral frontal, parietal, and occipital lobe infarcts. She had nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) affecting the tricuspid and aortic valves. She was started on hormonal and anticoagulant (warfarin) treatment. Kim et al. [49] described a case of a woman with adenomyosis and NBTE who developed multiple embolic cerebral infarcts leading to dysarthria, left perioral sensory change, and left-hand weakness. Infarcts were identified in the cerebellum and precentral gyrus. She had elevated DD, CA19-9, and CA125.

3.5. Renal Pathology

We identified two case reports that dealt with renal pathology complicating DIC. The first case, by Son et al. [10], was of acute kidney injury (AKI) in a 40-year-old woman with adenomyosis. Renal affection was the result of menstruation-related disseminated intravascular coagulation, which the authors attributed to myometrial injury resulting from a heavy intra-myometrial menstrual flow.

The second case report, by Yoo et al. [13], was of a woman with significant adenomyosis and menometrorrhagia who presented with DIC. This was successfully treated with hysterectomy and blood product transfusions.

4. Adenomyosis and Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Adenomyosis has been identified to be one of the structural causes of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). We recently reviewed this topic [66] and concluded that—despite the large volume of studies—available information does not provide conclusive evidence of a link. The study design in most studies was unsuitable. There was a lack of proper characterization of the study population, there were no agreed diagnostic criteria for adenomyosis, and there was no detailed assessment of menstrual blood loss. In addition, it must be borne in mind that symptoms of adenomyosis, including AUB, can occur in the presence of other pathologies. The incidence of concomitant pathology, such as endometriosis, leiomyomas, endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma is high. A study involving 710 premenopausal women undergoing hysterectomy for adenomyosis reported that only 4.5% had no symptoms, while dysmenorrhea was the most common complaint [67].

An important issue in evaluating the possible role of adenomyosis in causing vascular complications is the presence of a state of hypercoagulability in women with adenomyosis. This topic has been extensively investigated by Liu et al. [3], who observed the presence of a clinically relevant difference in coagulability between patients with adenomyosis-associated heavy menstrual bleeding (ADM-HMB) and women without adenomyosis. They concluded that precautionary, prophylactic measures may be advisable in order to reduce the risk of thrombotic events in ADM-HMB patients, especially those with excessive menstrual blood loss. In addition, the data suggest that anti-thrombotic/anti-coagulation therapies may hold therapeutic potential. Yet, these agents may increase bleeding. It is important to reiterate that the vast majority of case reports contain incomplete descriptions of the extent of the disease and of confounding factors that can increase the risk of vascular events. These include both local factors such as the presence or absence of concomitant pathology, and the use of steroids or other drugs that can increase coagulation. On the other hand, some of the described features, such as giant adenomyosis and very high CA125 levels, raise questions regarding the general applicability of these drugs to more typical cases. There are no controlled studies that compare thrombotic events in women with and without adenomyosis, and the available data suggest that such studies may be hindered by the need for a large cohort and long-term follow-up. CA125 is recognized to increase coagulability, but it is unclear if the mildly elevated levels noted in some women with adenomyosis have a significant clinical impact. Anemia results from excessive menstrual bleeding in adenomyosis and can result in a deranged coagulation profile. It is possible to hypothesize that increased coagulability is a bodily response that is aimed at limiting bleeding, or a result of its high association with inflammation. This is an area that warrants further investigation

5. Conclusions

It is extremely difficult to draw a firm conclusion on the pathogenetic role of adenomyosis in causing vascular complications, first and foremost because available evidence consists mostly of case reports. To begin with, contrary to common belief, we have recently documented that available studies do not provide conclusive evidence of a link between adenomyosis and abnormal uterine bleeding [3].

With regards to the hypercoagulable state and adenomyosis, there is evidence that platelets play a role in the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of adenomyosis [2,19,27]. In addition, there are case reports that show increased coagulability as a feature of adenomyosis. However, case reports are insufficient evidence of an association.

In this review, we compiled available evidence of vascular complications associated with adenomyosis; predominantly, these manifest as venous thromboembolism, ischemic stroke, and cerebral vasa thrombosis. Overall, these complications have been reported as single cases or short series, contrasting the high incidence of adenomyosis in women. This goes against the argument for the existence of a causative link. Thus, the strength of this study and the associations it discusses is that is continues to ask the question of whether there are causative links, except perhaps in a minority of cases with special features. In very rare instances these complications can also involve cardiac and renal pathology. In view of these complications, along with numerous reports of its association with depression and adenomyosis, as in the case of endometriosis, adenomyosis may be viewed as a disease with possible systemic manifestations [68].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., S.-W.G. and G.B.; methodology, I.R., P.B. and M.H.; validation, P.B. and G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H., G.B. and S.-W.G.; writing—review and editing, G.B., M.H. and S.-W.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Grant 82071623 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (S.-W.G.) and grant SHDC2020CR2062B from Shanghai Shanking Centre for Hospital Development (S.-W.G.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are derived from the publications listed in the list of references.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Habiba, M.; Benagiano, G.; Guo, S.W. An Appraisal of the Tissue Injury and Repair (TIAR) Theory on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis and Adenomyosis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.W. The role of platelets in the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of adenomyosis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Mao, C.; Guo, S.-W. Hypercoagulability in women with adenomyosis who experience heavy menstrual bleeding. J. Endometr. Uterine Dis. 2023, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.W. Endometriosis-Derived Thromboxane A2 Induces Neurite Outgrowth. Reprod. Sci. 2017, 24, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Li, T.; Ding, S.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, X. Anemia-associated platelets and plasma prothrombin time Increase in patients with adenomyosis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupryjanczyk, J. Intravascular endometriosis with thrombosis in a patient with adenomyosis. Patol. Pol. 1991, 42, 134–135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nawroth, F.; Schmidt, T.; Foth, D.; Landwehr, P.; Römer, T. Menorrhagia and adenomyosis in a patient with hyperhomocysteinemia, recurrent pelvic vein thromboses and extensive uterine collateral circulation treatment by supracervical hysterectomy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2001, 98, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Kawamura, N.; Ishiko, O.; Ogita, S. Acute disseminated intravascular coagulation developed during menstruation in an adenomyosis patient. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2002, 267, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akira, S.; Iwasaki, N.; Ichikawa, M.; Mine, K.; Kuwabara, Y.; Takeshita, T.; Tajima, H. Successful long-term management of adenomyosis associated with deep thrombosis by low-dose gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 36, 123–125. [Google Scholar]

- Son, J.; Lee, D.W.; Seong, E.Y.; Song, S.H.; Lee, S.B.; Kang, J.; Yang, B.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Choi, J.R.; Lee, K.S.; et al. Acute kidney injury due to menstruation-related disseminated intravascular coagulation in an adenomyosis patient: A case report. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 1372–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, A.; Imoto, S.; Mori, M.; Nakano, T.; Nakamura, H. Paraneoplastic consumptive coagulopathy related to intramyometrial low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma coexistent with adenomyosis diagnosed 7 years after laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010, 282, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, N.; Aoki, R.; Shinozaki, S.; Naito, N.; Ohyama, K. A case of anemia with schistocytosis, thrombocytopenia, and acute renal failure caused by adenomyosis. Intern. Med. 2011, 50, 2347–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.J.; Chang, D.S.; Lee, K.H. Acute renal failure induced by disseminated intravascular coagulopathy in a patient with adenomyosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2012, 38, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, T.; Shigematsu, K.; Nitahara, K.; Nakayama, N.; Miyamoto, S.; Higa, K. Anesthetic management of total hysterectomy in a patient with pulmonary thromboembolism. Masui 2013, 62, 696–698. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, X.; Luo, F.; Shi, G.; He, Y.; Yao, Y.; Xu, L. Acute disseminated intravascular coagulation developed after dilation and curettage in an adenomyosis patient: A case report. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2013, 24, 771–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, A.; Kimura, F.; Yoshida, T.; Kita, N.; Takahashi, K.; Kushima, R.; Murakmai, T. Dysfunctional coagulation and fibrinolysis systems due to adenomyosis is a possible cause of thrombosis and menorrhagia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 204, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernogoraz, A.; Schiraldi, L.; Bonazza, D.; Ricci, G. Menstruation-related disseminated intravascular coagulation in an adenomyosis patient: Case report and review of the literature. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019, 35, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, F.; Takahashi, A.; Kitazawa, J.; Yoshino, F.; Katsura, D.; Amano, T.; Murakami, T. Successful conservative treatment for massive uterine bleeding with non-septic disseminated intravascular coagulation after termination of early pregnancy in a woman with huge adenomyosis: Case report. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.Y.; Lin, H.Z.; Fong, Y.F. Venous thromboembolism and adenomyosis: A retrospective review. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2020, 9, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.Y.; Peng, C.; Zhou, Y.F.; Huang, Y.; Song, H. Changes of coagulation function in patients with adenomyosis and its clinical significance. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2020, 55, 749–753. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.-C.; Zhu, L.-H.; Qian, Z.-D.; Huang, L.-L. Disseminated intravascular coagulation developed after suction curettage in an adenomyosis patient: A case report and literature review. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 48, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, A.Q.; Zhu, S.; Yu, L.; Sun, J.F.; Xu, W.; Wang, X.L. Changes of coagulation function in patients with adenomyosis. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2022, 57, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Tang, X.; Zheng, D. Isolated distal deep vein thrombosis associated with adenomyosis: Case report and literature review. Clin. Case Rep. 2024, 12, e8859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Shen, M.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, H.; Guo, S.W. Corroborating evidence for platelet-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transdifferentiation in the development of adenomyosis. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Guo, S.W. Transforming growth factor beta1 signaling coincides with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transdifferentiation in the development of adenomyosis in mice. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mosele, S.; Stratopoulou, C.A.; Camboni, A.; Donnez, J.; Dolmans, M.M. Investigation of the role of platelets in the aetiopathogenesis of adenomyosis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2021, 42, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Nie, J.; Guo, S.W. Elevated immunoreactivity to tissue factor and its association with dysmenorrhea severity and the amount of menses in adenomyosis. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteeg, H.H.; Schaffner, F.; Kerver, M.; Petersen, H.H.; Ahamed, J.; Felding-Habermann, B.; Takada, Y.; Mueller, B.M.; Ruf, W. Inhibition of tissue factor signaling suppresses tumor growth. Blood 2008, 111, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Lin, Q.; Zhu, T.; Li, T.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Is there a correlation between inflammatory markers and coagulation parameters in women with advanced ovarian endometriosis? BMC Womens Health 2019, 19, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, Q.; Ma, R.; Deng, F.; Liu, J. CA125-associated activated partial thromboplastin time and thrombin time decrease in patients with adenomyosis. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, S. Hypercoagulable states. In Mechanisms of Vascular Disease: A Reference Book for Vascular Specialists; Fitridge, R., Thompson, M., Eds.; Barr Smith Press an Imprint of the University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2011; pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, M.; Fraser, I.S. Clinical implications of disturbances of uterine vascular morphology and function. Baillieres Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2000, 14, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watters, M.; Martinez-Aguilar, R.; Maybin, J.A. The menstrual endometrium: From physiology to future treatments. Front. Reprod. Health 2021, 3, 794352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, A.A.; Silva, E.G.; Landon, G.; Ordonez, N.G.; Gershenson, D.M. Endometrial tissue in myometrial vessels not associated with menstruation. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1989, 8, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenakshi, M.; McCluggage, W.G. Vascular involvement in adenomyosis: Report of a large series of a common phenomenon with observations on the pathogenesis of adenomyosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2010, 29, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhija, D.; Mathai, A.M.; Naik, R.; Kumar, S.; Rai, S.; Pai, M.R.; Baliga, P. Morphometric evaluation of endometrial blood vessels. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2008, 51, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokyol, C.; Aktepe, F.; Dilek, F.H.; Sahin, O.; Arioz, D.T. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-2 in adenomyosis and endometrial polyps and its correlation with angiogenesis. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2009, 28, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goteri, G.; Lucarini, G.; Montik, N.; Zizzi, A.; Stramazzotti, D.; Fabris, G.; Tranquilli, A.L.; Ciavattini, A. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha), and microvessel density in endometrial tissue in women with adenomyosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2009, 28, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Yi, T.; Liu, R.; Bian, C.; Qi, X.; He, X.; Wang, K.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, C.; et al. Proteomics identification of annexin A2 as a key mediator in the metastasis and proangiogenesis of endometrial cells in human adenomyosis. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP 2012, 11, M112 017988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Shao, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, L.P.; Li, D.J.; Li, M.Q. L-22 enhances the invasiveness of endometrial stromal cells of adenomyosis in an autocrine manner. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2014, 7, 5762–5771. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, W.Q.; Yu, J.J.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, W.J.; Chang, K.K.; Wang, Q.; Li, M.Q. Blocking IL-22, a potential treatment strategy for adenomyosis by inhibiting crosstalk between vascular endothelial and endometrial stromal cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2015, 7, 1782–1797. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Luo, N.; Guo, J.; Xie, Y.; Chen, L.; Cheng, Z. Berberine inhibits growth and inflammatory invasive phenotypes of ectopic stromal cells: Imply the possible treatment of adenomyosis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 137, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashiro, K.; Furuya, T.; Noda, K.; Urabe, T.; Hattori, N.; Okuma, Y. Cerebral infarction developing in a patient without cancer with a markedly elevated level of mucinous tumor marker. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2012, 21, 619.e1–619.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, K.; Tanaka, R.; Nishioka, K.; Ueno, Y.; Shimura, H.; Okuma, Y.; Hattori, N.; Urabe, T. Cerebral infarcts associated with adenomyosis among middle-aged women. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2012, 21, 910.e1–910.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeda, S.; Mathuda, N.; Hashimoto, Y.; Yamada, H.; Fujimori, K. Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis with systemic embolic events caused by adenomyosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2011, 37, 1838–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, K.; Tanaka, R.; Tsutsumi, S.; Yamashiro, K.; Nakahara, M.; Shimura, H.; Hattori, N.; Urabe, T. Cerebral dural sinus thrombosis associated with adenomyosis: A case report. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2014, 23, 1985–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijikata, N.; Sakamoto, Y.; Nito, C.; Matsumoto, N.; Abe, A.; Nogami, A.; Sato, T.; Hokama, H.; Okubo, S.; Kimura, K. Multiple cerebral infarctions in a patient with adenomyosis on hormone replacement therapy: A case report. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2016, 25, e183–e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, K.; Shimizu, T.; Mizukami, H.; Isahaya, K.; Ogura, H.; Shinohara, K.; Hasegawa, Y. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis complicated by cerebral infarction in a patient with adenomyosis with high serum ca125 level a case report. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018, 27, e42–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, T. Cerebral Infarcts by Nonbacterial Thrombotic Endocarditis Associated with Adenomyosis: A Case Report. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018, 27, e50–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso, Y.; Chikazawa, R.; Kimura, Y.; Kimura, N.; Matsubara, E. Recurrent multiple cerebral infarctions related to the progression of adenomyosis: A case report. BMC Neurol. 2018, 18, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, K.; Oka, F.; Ishihara, H.; Suzuki, M. Cerebral infarction associated with benign mucin-producing adenomyosis: Report of two cases. BMC Neurol. 2018, 18, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Wu, J.; Song, S.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y. Cerebral infarcts associated with adenomyosis: A rare risk factor for stroke in middle-aged women: A case series. BMC Neurol. 2018, 18, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y. Acute cerebral infarction with adenomyosis in a patient with fever: A case report. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiura, R.; Nakayama, S.; Yamaga, H.; Kato, Y.; Fujishima, H. Systemic thromboembolism including multiple cerebral infarctions with middle cerebral artery occlusion caused by the progression of adenomyosis with benign gynecological tumor: A case report. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, M.; Yamanaka, Y.; Kano, H.; Araki, N.; Ishikawa, H.; Ikeda, J.I.; Kuwabara, S. Recurrent cerebral infarcts associated with uterine adenomyosis: Successful prevention by surgical removal. Intern. Med. 2022, 61, 735–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, N.; Yachi, K.; Ishihara, R.; Fukushima, T. Adenomyosis-associated recurrent acute cerebral infarction mimicking Trousseau’s syndrome: A case study and review of literature. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2022, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, M.; Uzawa, A.; Kitayama, Y.; Habu, Y.; Kuwabara, S. Multiple cerebral infarctions complicating deep vein thrombosis associated with uterine adenomyosis: A case report and literature review. Cureus 2022, 14, e28061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.K.; Thapa, A.; Bhattarai, A.; Ashmita, K.C.; Budhathoki, S.J.; Chandra, A.; Rajbhandari, R. Cerebral venous thrombosis in a patient with adenomyosis: A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2022, 10, e6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, D.; Wang, A.; Wu, S.; Wu, B. Adenomyosis-associated ischemic stroke: Pathophysiology, detection and management. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shi, K.; Jing, C.; Xu, L.; Kong, M.; Ba, M. Successful management of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis due to adenomyosis: Case reports and literature review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2023, 229, 107726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishima, Y.; Ueno, Y.; Satake, A.; Fukao, T.; Tsuchiya, M.; Hata, T.; Ogawa, T.; Oishi, N.; Nakajima, S.; Hirata, S.; et al. Recurrent embolic stroke associated with adenomyosis: A single case report and literature review. Neurol. Sci. 2023, 44, 2421–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.S. Cerebral infarction related to nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in a middle-aged woman with uterine adenomyosis: A case report. Medicine 2023, 102, e33871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, K.; Sato, T.; Nito, C.; Ueno, Y.; Kawano, H.; Chiba, T.; Nishihira, T.; Mizuno, T.; Ishizuka, K.; Iguchi, Y.; et al. Stroke in patients with common noncancerous gynecologic diseases: A multicenter study in Japan. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2023, 13, e200165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chi, B.; Liu, M.; Hou, P.; Wu, J.; Wang, S. Adenomyosis accompanied by multiple hemorrhagic cerebral infarction: A case report. Cureus 2024, 16, e59280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, S.; Aydin, S.; Ozcan, P. Cardiometabolic profiles in women with adenomyosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 3080–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habiba, M.; Guo, S.W.; Benagiano, G. Adenomyosis and abnormal uterine bleeding: Review of the evidence. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.W. Clinical profiles of 710 premenopausal women with adenomyosis who underwent hysterectomy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2014, 40, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.S.; Kotlyar, A.M.; Flores, V.A. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: Clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet 2021, 397, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).