1. Introduction

Infertility affects millions of individuals worldwide, with approximately one in six people experiencing it during their lifetimes [

1]. It is commonly described as a disease of the male or female reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a pregnancy after, at least, 12 months of regular unprotected sexual intercourse [

2]. Given the substantial global burden of infertility, including social stigma, economic hardship, and adverse physical and mental health outcomes, there is a continued need to optimize assisted reproductive care [

3].

Over the last few decades, the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) has risen steadily and has enabled many couples to achieve parenthood [

4,

5]. ART comprises all fertility treatments in which oocytes are retrieved from the ovaries, fertilized ex vivo, and transferred to the uterus, most commonly through in vitro fertilization (IVF) with or without intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) [

6]. Frozen–thawed embryo transfer (FET) has been widely used in ART since the development of advanced cryopreservation techniques [

7]. FET allows the transfer of surplus embryos from an ovarian stimulation cycle, thereby increasing cumulative pregnancy birth rates, reducing embryo wastage, and facilitating strategies such as freeze-all, preimplantation genetic testing, and the prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome [

8,

9]. Currently, FET accounts for roughly 25% of ART births, with success highly dependent on embryo quality and the optimization of endometrial preparation [

5,

10].

Several protocols can be used for endometrial priming, including true natural cycles with spontaneous ovulation; modified natural cycles in which ovulation is triggered with human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG); ovarian stimulation cycles with or without letrozole; and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) cycles with or without pituitary downregulation [

9]. Among these, HRT-FET cycles are widely adopted due to their predictability, scheduling flexibility, and low cancelation risk, especially in anovulatory women [

7,

9]. However, the absence of a corpus luteum in HRT cycles has been linked to altered maternal vascular physiology and an increased risk of adverse obstetric outcomes, such as hypertensive disorders, abnormal birthweight, and macrosomia [

9,

11]. For these reasons, women capable of spontaneous ovulation are generally advised to prioritize natural cycle regimens [

9].

Progesterone (P) plays a central role in the luteal phase by inducing secretory transformation of the endometrium, ensuring embryo implantation, and supporting early gestation [

12,

13]. Women undergoing HRT-FET cycles cannot produce sufficient endogenous luteal P and therefore require exogenous supplementation [

14,

15]. Different routes of P administration, including oral, intramuscular, vaginal, rectal, and subcutaneous preparations, have been explored, each differing in pharmacokinetics, serum bioavailability, tolerability, and patient preference [

9]. Vaginal and intramuscular preparations are the most widely used. Intramuscular injections are frequently employed in FET cycles to achieve high serum concentrations and high clinical pregnancy rates (CPRs) [

10]; however, most patients prefer vaginal administration due to greater convenience, ease of use, and reduced pain [

9,

16]. Oral P, although convenient, is generally avoided due to its low bioavailability and reduced efficacy in ART [

16]. Dydrogesterone, a synthetic progestin with enhanced oral bioavailability, has increasingly been used as an adjunct to other administration routes to improve pregnancy outcomes [

9,

16,

17]. Despite the unquestionable importance of P, the optimal regimen and monitoring strategy remain debated [

7,

18].

Growing evidence suggests that serum P levels on or immediately before the day of FET influence reproductive success [

14,

19]. Several studies report poorer outcomes when serum P concentrations fall below a minimal effective threshold, proposing values between 7 and 11 ng/mL depending on protocol, measurement timing, and route of administration [

19,

20]. Conversely, excessively elevated serum P concentrations have also been associated with reduced implantation in some cohorts, raising concerns about supraphysiologic exposure [

14,

21,

22]. Although a P threshold of 10 ng/mL is the most commonly reported in the literature, reflecting the currently accepted indicator of adequate corpus luteum function [

23], no consensus exists regarding the optimal serum P concentration on the day of embryo transfer with respect to pregnancy rates and early pregnancy loss in women undergoing FET cycles [

7,

13,

20]. The heterogeneity of protocols, formulations, and laboratory assays across centers partly explains the inconsistent findings, leading many authors to recommend institution-specific thresholds and individualization of luteal support strategies [

7,

15].

Given the heterogeneity and limited strength of the literature, the present study aims to investigate the predictive value of serum P in cryopreserved embryo transfer cycles above which pregnancy rates do not decline in our center. To this end, we seek to evaluate the association between serum P levels measured on the day of FET and pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in women undergoing IVF or ICSI with transfer of frozen–thawed embryos at different developmental stages. In addition, we aim to assess patients’ baseline characteristics according to serum P levels on the day of FET.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Center of Assisted Medical Procreation of Centro Materno-Infantil do Norte Dr. Albino Aroso and included all FET procedures performed between November 2021 and July 2023.

2.2. Study Population

A total of 417 FET cycles were performed during the described period, of which 313 met the inclusion criteria. Eligible participants were women aged 18 to 40 years who underwent HRT-FET with their own oocytes and had serum P levels measured on the day of FET. Exclusion criteria included patients with known Müllerian malformations, and cases with incomplete or missing data.

2.3. Study Protocol

2.3.1. Endometrial Preparation

Endometrial preparation was achieved through sequential administration of oral estradiol (Zumenon® or Estrofem®) 2 mg every 8 h, starting 15 days after subcutaneous injection of goserelin acetate (Zoladex®) 3.6 mg/24 h in the midluteal phase of the preceding cycle. After 7 days of estrogen therapy, a transvaginal ultrasound was performed to assess endometrial thickness. In patients with an endometrium <8 mm, oral estradiol 2 mg every 6 h was extended for up to 4 additional days, if required. When a triple-line endometrium of ≥8 mm thickness was observed, exogenous P supplementation was initiated using micronized P vaginal capsules (Cyclogest®) 400 mg every 12 h. Due to the absence of a corpus luteum and endogenous sex steroid production, exogenous hormone therapy was continued until 12 completed weeks of gestation.

2.3.2. Embryo Transfer

Embryos were previously generated through IVF or ICSI cycles and vitrified on day 3 or at the blastocyst stage. Embryo quality was assessed morphologically, with the embryologist making the final decision regarding which embryo to transfer. Transfers were performed 3 or 5–6 days after initial P administration, depending on the developmental embryo stage. On the day of FET, a blood sample was collected between 8 a.m. and 10 a.m. for serum P measurement. Preferably, a single embryo was transferred in each cycle. All transfers were performed under ultrasound guidance, and both the number of embryos transferred and their developmental stage were recorded. Serum hCG testing was performed 14 days after FET, and routine ultrasound follow-up was conducted 28 days after the procedure.

2.4. General Characteristics of Included Patients

Baseline patient characteristics were obtained from the database of the Center of Assisted Medical Procreation. Variables included maternal age, maternal body mass index (BMI), duration of infertility, type of infertility (primary or secondary), infertility diagnosis (female factor, male factor, combined factors, or unexplained), fertilization method (IVF and/or ICSI), number of FET cycles, serum P level on the day of FET, number of embryos transferred (single or double), and embryo stage at transfer (cleavage of blastocyst).

Infertility duration was calculated in months from the time the couple began attempting conception until the day of the FET. Primary infertility was defined as the absence of any prior pregnancy, whereas secondary infertility referred to cases in which at least one previous pregnancy had occurred. Female factor infertility included cases with isolated female reproductive issues, such as tubal factor, endometriosis, ovulatory dysfunction, oocyte factor, and uterine factor (excluding uterine malformations). Male factor infertility included oligoasthenoteratozoospermia and paraplegia. All cases in which both female and male factors contributed to the infertility were classified as having combined factors. Unexplained infertility was defined as the absence of identifiable causes; however, due to the small number of these cases and their lack of statistical significance, they were excluded from the analysis to allow more accurate comparison among the three primary infertility categories.

2.5. Clinical Outcomes

Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes were obtained from the same database.

Regarding the pregnancy outcomes, the primary endpoint was the association between serum P levels on the day of FET and LBR per cycle, defined as the proportion of the number of deliveries that resulted in at least one live birth (≥24 weeks of gestation) among all transfer cycles. Secondary endpoints included positive β-hCG test rate, biochemical pregnancy rate, implantation rate, CPR, early miscarriage rate, and ongoing pregnancy rate (OPR). A β-hCG test was considered positive if levels exceeded 25 IU/L. Biochemical pregnancy rate was defined as the proportion of patients with a positive β-hCG test without a visible gestational sac on ultrasound. CPR was defined as the proportion of patients with an ultrasound confirmation of at least one intrauterine gestational sac after 6 weeks of gestation among all embryo transfer cycles. Implantation rate was defined as the number of gestational sacs per transferred embryos. Early miscarriage rate was defined as the proportion of patients with pregnancy lost before 12 completed weeks of gestation; no late miscarriages were observed. OPR was defined as the proportion of patients with a gestational sac showing fetal heart activity on ultrasound examination at 13 weeks of gestation among all embryo transfer cycles.

Neonatal outcomes included the number of neonates (singletons or twins), gestational age at birth, birthweight, preterm birth (PTB), low birthweight (LBW), major congenital malformations, and neonatal death. PTB was defined as birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation, and LBW was defined as birthweight below 2500 g. Percentages were calculated based on the number of births.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Three different thresholds were considered in assessing the association between serum P levels and both baseline characteristics and FET outcomes: (1) a fixed threshold of 10 ng/mL; (2) stratification into four quartiles (Qs) based on 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles; and (3) receiver operating characteristic (ROC)-derived optimal P cut-off for predicting CPR.

P levels measured on the day of FET were categorized into Qs based on the distribution of the study population. The serum P intervals obtained for each Q were as follows: Q1 < 7.30 ng/mL; Q2: 7.30–10.26 ng/mL; Q3: 10.27–13.42 ng/mL; and Q4 > 13.42 ng/mL (

Figure 1).

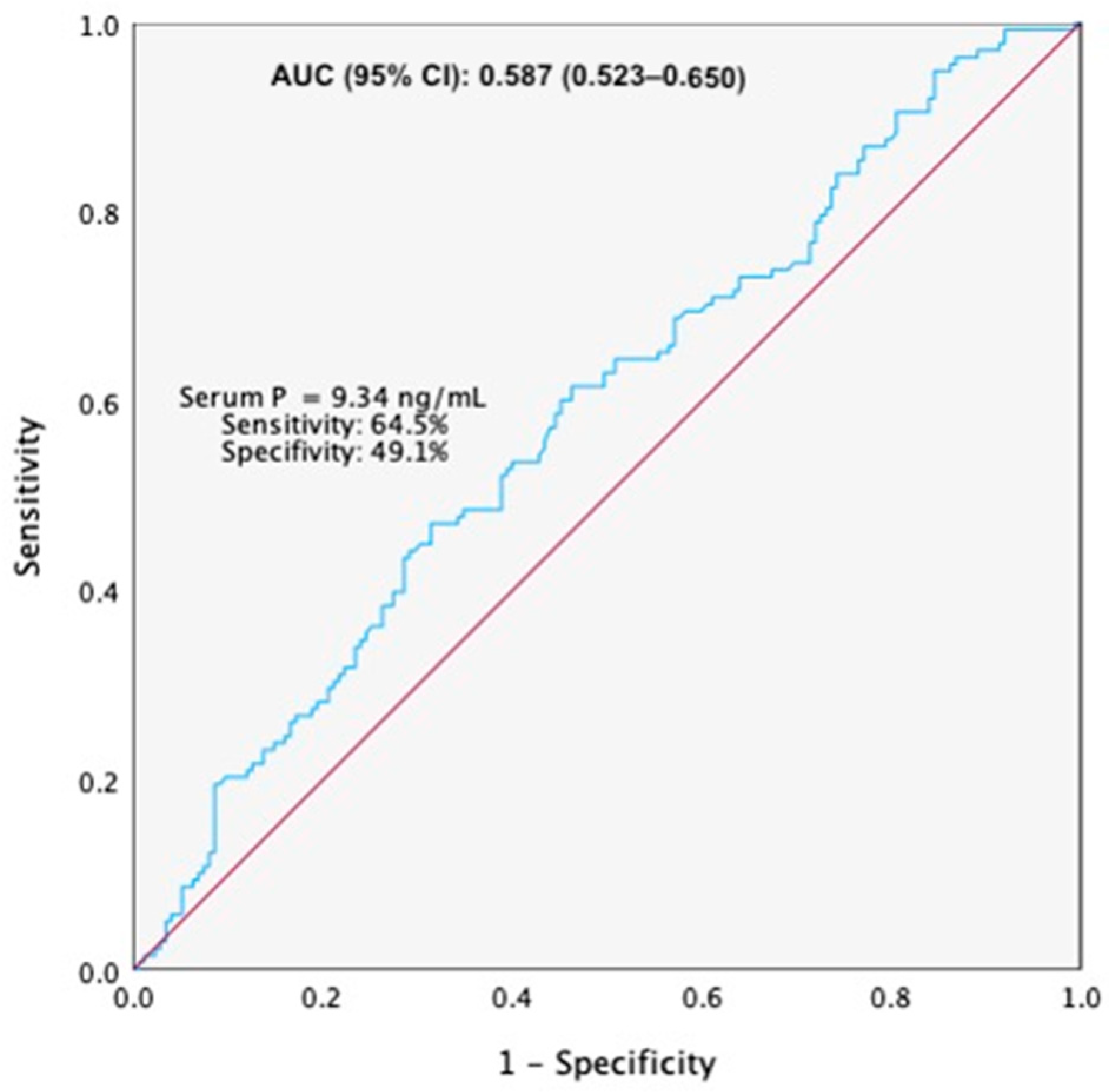

The selection of the optimal P cut-off was based on ROC curve analysis, which identified this value as providing the best balance between sensitivity and specificity for predicting clinical pregnancy in our cohort. ROC curve demonstrated a significant predictive value of serum P levels on the day of embryo transfer for CPR, with an AUC (95% CI) = 0.587 (0.523–0.650) (

Figure 2). The optimal cut-off value for predicting CPR was a serum P level of 9.34 ng/mL, corresponding to a sensitivity of 64.5% and a specificity of 49.1%.

A schematic conceptual model illustrating the three analytical strategies used to evaluate the association between serum P levels on the day of FET and baseline characteristics and reproductive outcomes is presented in

Figure 3.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and were compared using the t-test or One-Way ANOVA, as appropriate. APGAR scores are reported as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and between-group differences were assessed using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The association between serum P levels and pregnancy outcomes was assessed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. To adjust for potential confounders, those variables were introduced into the regression model. These included maternal age, maternal BMI, duration of infertility, infertility diagnosis, P level on the day of FET, number of embryos transferred, and embryo stage at transfer.

All p values were based on two-sided tests, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0 software.

3. Results

A total of 313 FET cycles were analyzed in terms of demographic characteristics and reproductive outcomes. Patients’ mean age was 34.2 ± 3.9 years and mean BMI was 24.8 ± 4.6 kg/m2. The main indication for FET was freeze-all cycles. There was a wide range of observed P levels on the day of FET (0.12–39.57 ng/mL), with a mean value of 10.98 ± 6.37 ng/mL.

When considering the P threshold of 10 ng/mL, baseline patient characteristics were largely similar between groups (

Table 1). The only significant difference was observed for maternal BMI, which was slightly higher in the

p < 10 ng/mL group compared to the

p ≥ 10 ng/mL group (25.37 ± 4.71 vs. 24.27 ± 4.38;

p = 0.034). No significant differences were found when the remaining baseline characteristics were analyzed. Mean serum P levels on the day of FET were 6.49 ± 2.62 ng/mL in the

p < 10 ng/mL group and 15.38 ± 5.87 ng/mL in the

p ≥ 10 ng/mL group (

p < 0.001).

Significant differences were observed in pregnancy outcomes according to the 10 ng/mL serum P threshold (

Table 2). Patients with serum P levels < 10 ng/mL on the day of FET had significantly lower positive β-hCG test rates, implantation rates, and CPR compared with those with

p ≥ 10 ng/mL: 40.0% (62/155) vs. 59.5% (84/158) (

p = 0.020); 31.1% (60/193) vs. 46.2% (91/197) (

p = 0.002); and 37.4% (58/155) vs. 50.6% (80/158) (

p = 0.019), respectively. No significant differences were found between the two groups in biochemical pregnancy rate, early miscarriage rate, OPR, or LBR.

Additionally, no significant differences were observed between the two groups when neonatal outcomes were analyzed (

Table 3).

By categorizing the P levels into Qs, no significant differences were found among groups in either baseline characteristics or reproductive outcomes (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6).

Considering the P threshold of 9.34 ng/mL, almost no significant differences were observed between groups when baseline patient characteristics were analyzed (

Table 7). The two groups,

p < 9.34 ng/mL and

p ≥ 9.34 ng/mL, differed significantly only in maternal BMI (25.53 ± 4.77 vs. 24.27 ± 4.34;

p = 0.015). No significant differences were identified in the remaining baseline characteristics. The mean serum P levels on the day of FET were 6.02 ± 2.49 ng/mL and 14.73 ± 5.83 ng/mL in the

p < 9.34 ng/mL and

p ≥ 9.34 ng/mL groups, respectively (

p < 0.001).

Several statistically significant differences were observed when assessing pregnancy outcomes according to the serum P threshold of 9.34 ng/mL (

Table 8). Patients with serum P levels < 9.34 ng/mL on the day of FET had significantly poorer pregnancy outcomes than those with

p ≥ 9.34 ng/mL, including: positive β-hCG test rate [(38.5% (52/135) vs. 52.8% (94/178),

p = 0.012]; implantation rate [30.0% (51/170) vs. 45.5% (100/220),

p = 0.002]; CPR [36.3% (49/135) vs. 50.0% (89/178),

p = 0.016]; OPR [24.4% (33/135) vs. 37.6% (67/178),

p = 0.013]; and LBR [24.4% (33/135) vs. 37.6% (67/178),

p = 0.013]. No significant differences were identified when biochemical pregnancy rate and early miscarriage rate were analyzed.

In the multivariate analysis, the factors significantly associated with positive β-hCG test were infertility diagnosis involving combined female and male factors (adjusted OR = 2.51, 95% CI: 1.29–4.87,

p = 0.007), the number of embryos transferred (adjusted OR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.08–3.53,

p = 0.028), and serum P levels ≥ 9.34 ng/mL on the day of FET (adjusted OR = 2.04, 95% CI: 1.23–3.37,

p = 0.006) (

Table 9). Regarding CPR, maternal age (adjusted OR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.88–1.01,

p = 0.042), infertility diagnosis combining female and male factors (adjusted OR = 2.50, 95% CI: 1.28–4.85,

p = 0.007), number of embryos transferred (adjusted OR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.09–3.58,

p = 0.024), and serum P levels ≥ 9.34 ng/mL (adjusted OR = 1.92, 95% CI: 1.16–3.19,

p = 0.011) were significantly associated with this outcome. Additionally, the multivariate analysis showed that factors significantly associated with LBR included maternal age (adjusted OR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.86–1.00,

p = 0.036), number of embryos transferred (adjusted OR = 2.73, 95% CI: 1.47–5.10,

p = 0.002), and serum P levels ≥ 9.34 ng/mL on the day of FET (adjusted OR = 2.10, 95% CI: 1.20–3.67,

p = 0.009). Overall, the multivariate analysis identified serum P levels ≥ 9.34 ng/mL on the day of FET as an independent predictive factor for pregnancy outcomes.

Regarding the neonatal outcomes of live-born infants according to the serum P threshold of 9.34 ng/mL, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups for any of the evaluated parameters (

Table 10).

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates a significant association between serum P levels on the day of FET and pregnancy outcomes in artificial cycles using vaginal micronized P. Regarding P threshold of 10 ng/mL, univariate analyses showed that patients with serum P levels ≥ 10 ng/mL on the FET day had significantly higher rates of positive β-hCG testing, implantation, and clinical pregnancy. Further analysis using a data-derived threshold of 9.34 ng/mL revealed that patients with serum P levels above this value exhibited significantly higher positive β-hCG test rates, implantation rates, CPR, OPR, and LBR. Although the early miscarriage rate was not statistically different between groups, there was a trend toward a lower rate among patients with P levels ≥ 9.34 ng/mL. After adjusting for potential confounders, serum P levels ≥ 9.34 ng/mL remained significantly associated with an increased likelihood of achieving a positive β-hCG test, clinical pregnancy, and live birth. Therefore, serum P levels above this P cut-off appear to be an independent predictive factor for pregnancy outcomes. Although values close to this threshold (such as 7 ng/mL or 8 ng/mL) may also have potential relevance, they did not yield superior predictive performance in our analysis. Higher P concentrations (>>9.34 ng/mL) may raise clinical uncertainties, as excessively elevated levels have been suggested in some studies to be associated with impaired implantation [

22].

Although previous studies have proposed variable minimal effective serum P thresholds, our findings align with the lower range of previously reported thresholds [

12,

24,

25,

26], reinforcing that achieving a minimal adequate exposure is critical for endometrial receptivity in HRT cycles. While 9.34 ng/mL emerged as the optimal threshold in our dataset, further multicenter and large-scale studies are needed to confirm whether this value or potentially lower thresholds can be applied more broadly in routine clinical practice.

The variability between studies likely reflects differences in endometrial preparation protocols, P formulations, routes of administration, and monitoring strategies across centers [

7,

27]. As such, many authors recommend that establishing center-specific reference values may be preferable to adopting a universal threshold. Conversely, inter-individual variability in P absorption, metabolism and bioavailability has been increasingly recognized as a possible contributor to suboptimal serum levels despite standardized protocols [

16,

21,

28]. This reinforces current discussions regarding the need for a careful monitoring of serum P levels during the luteal phase to allow for a rescue P protocol and the potential value of individualized luteal support [

13].

Our findings contribute to this body of evidence by reinforcing the challenges of clinical use of a single P cut-off value. First, although low serum P levels have been associated with poorer reproductive outcomes, it is still unclear whether adjusting P supplementation in real time is sufficient to reverse this risk. Second, the extent to which serum values accurately reflect endometrial exposure remains debated, and the clinical benefit of modifying P regimens based on isolated measurements is still not well established. Third, the inter-individual variability and the absence of a standardized monitoring protocol across centers limits the generalizability of any proposed P cut-off. Therefore, the problem highlighted by our findings is not only the identification of a minimum P threshold but also the need to determine how clinicians should intervene when levels fall below this range—an aspect that remains unresolved in current literature.

We also identified other known predictors of reproductive success. As reported in previous studies [

29,

30,

31,

32], advanced maternal age was associated with lower LBR, whereas double-embryo transfer increased the likelihood of live birth compared with single-embryo transfer. These observations further validate the representativeness of our study population.

In addition to pregnancy outcomes, attention has been drawn to the potential impact of serum P levels on neonatal outcomes [

9]. In our study, no statistically significant differences were observed for PTB, LBW, major congenital malformations, and early neonatal death, across the three P-defined thresholds. The absence of statistical significance may reflect limited statistical power to detect subtle differences, as well as the inherent variability of neonatal parameters. Additionally, several relevant maternal and clinical factors that were not captured in the present study could have influenced neonatal outcomes, such as maternal age, BMI, underlying comorbidities, obstetric history, lifestyle factors, as well as differences in embryo quality or laboratory and neonatal care practices. These unmeasured confounders may have diluted potential associations between serum P levels and neonatal results. Notably, previous studies have also reported minimal or inconsistent effects of P levels on neonatal outcomes after FET [

16], suggesting that P may play a more substantial role in endometrial preparation and implantation rather than in later stages of fetal development. Future studies with larger cohorts and more comprehensive perinatal data collection are warranted to clarify these relationships.

This study has some inherent limitations. The main limitation is its retrospective design, which limits causal inference and precludes to conclude on how to optimize reproductive outcomes in women with low serum

p values. In addition, the relatively small sample size, resulting from the short study period and the exclusion of cases with missing data, may reduce statistical power. Although analyses were adjusted to reduce the risk of confounding, selection bias cannot be entirely excluded. Embryo aneuploidy is a known contributor to implantation failure; however, the potential influence of embryo ploidy and quality on this finding was not ruled out. Endometrial thickness and pattern were also not assessed in the present study, although previous evidence suggests minimal impact of these parameters on implantation and pregnancy rates [

33].

Overall, our findings underscore both the clinical relevance and the complexity of determining an optimal serum P level in artificial-cycle FET and highlight the continued need for prospective well-designed studies to determine whether targeted interventions can effectively improve pregnancy outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In this study, serum P levels ≥ 9.34 ng/mL on the day of FET were associated with higher clinical pregnancy and LBR in HRT cycles using intravaginal P. No significant differences were observed in neonatal outcomes (PTB, LBW, congenital malformations, early neonatal death) across different P thresholds.

These findings reinforce the importance of achieving a minimal serum P level to optimize pregnancy outcomes in HRT cycles. Inter-individual variability supports the potential value of individualized serum monitoring to identify patients at risk of suboptimal luteal support.

Future research should evaluate individualized P supplementation strategies in cases of low serum levels and investigate whether increasing P dosage or introducing alternative administration routes can effectively improve reproductive outcomes.