Abstract

In this work, plasma nitriding was carried out to improve the corrosion resistance of API 5L X70 steel. The process was conducted at different treatment times, 4, 6, 8, and 10 h, to determine which one provides greater resistance to corrosion. The conditions under which the nitriding was carried out were as follows: a mixture of 20% N2 and 80% H2 at 3 torr pressure, a current of 2.6 × 10−6 A, a voltage of 360 V, and the temperature inside the plasma chamber was 550 °C. The blank and nitrided materials were characterized using dispersive energy spectroscopy and scanning microscopy to study their morphology and chemical composition. In addition, open potential circuit, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, and potentiodynamic polarization curves in simulated soil solution were performed to evaluate the materials’ corrosion resistance. The treatment achieved at 10 h presented the greatest corrosion resistance, reducing the corrosion current density up to three orders of magnitude. The thickness reached 678.75 µm for this condition.

1. Introduction

The oil industry is one of the most studied fields in corrosion. The main materials used in oil ducts [1] are steels (HSLA), which contain elements (V, Ti, Nb) at different concentrations and a low carbon content (0.08–0.12 wt %) [2,3,4,5]. Corrosion affects pipeline networks, leading to high economic losses and a potential impact on the environment if a leak occurs [6,7]. The main aggressive species found in pipelines are NaCl and corrosive gases such as CO2 and H2S [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Additionally, given the working environmental conditions, these steels are susceptible to stress corrosion cracking [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Most leaks in pipelines are due to failures from both internal and external corrosion (33% and 12%, respectively) [7,20,21]. External corrosion depends on the degree of aggressiveness of the soil in which the pipes are buried [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Over time, different soil samples have been analyzed, revealing various degrees of aggressivity, which were classified as follows: NS1 to NS4, NS4 being the highest. This solution is also referred to as a simulated soil solution [29]. For the corrosion protection of buried pipelines, different methods exist—including coatings and/or cathodic protection—to prevent leaks and ruptures [30,31,32]. Other methods for improving the corrosion resistance in different areas are coatings of titanium nitride (TiN) or carburizing with plasma electrolytic treatment [33,34]. However, currently, plasma nitriding treatment is mainly used in areas such as machine tool manufacturing, the automotive industry, etc. Since this surface heat treatment significantly improves resistance to wear, fatigue, and corrosion resistance, one of its main advantages is that it is more environmentally friendly compared to other nitriding technologies [35,36,37,38,39]. In the thermochemical treatment of plasma nitriding, several parameters can be controlled, depending on the application; some of these parameters include the type of gases, their mixture, the treatment time, and the temperature [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. This treatment is easy to apply on surfaces; however, it can be challenging on geometrically complex surfaces [35,41].

In this study, how plasma nitriding treatment influences corrosion resistance at different treatment times is analyzed. It aims to determine which thermal treatment duration provides the best protection against corrosion and record the behavior of the material over time. Additionally, the study aims to understand how nitrides affect the corrosion of API 5L X70 steel when it is in contact with a simulated corrosive soil solution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples Preparation

The API 5L X70 steel was cut into cubes of 1 cm per side with a disk cutter at low revolutions to achieve a clean and precise cut. The samples were polished with silicon carbide sandpaper, progressing from 80 to 2000 grain size. After that, the surface was polished with alumina until it developed a mirror-like finish. After polishing, the samples were washed with acetone and alcohol before being stored in a desiccator for later use [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

2.2. Plasma Surface Modification

The discharge chamber was made of glass, and the base was made of aluminum. The power supply had an alternating current capacity of 360 volts and 0.3 amps. The mechanical vacuum pump was a Leibold (Trivac model D10) with a pumping capacity of 6 dm3 per second, reaching a vacuum pressure of 1 × 10−3 torr. The Pirani MKS vacuum gauge (model 945) had a measurement range from 1 × 10−3 torr to atmospheric pressure. Electrical variables were measured with an Agilent multimeter (model 344401A) with a capacity of 0–700 V and 1 A. The pressure was controlled using a Matheson flowmeter through a needle valve.

The experimental parameters were the following: the discharge was carried out 360 V, the current was 2.6 × 10−6 A, and electrodes were separated 5 mm apart. The gas mixture consisted of 80% hydrogen and 20% nitrogen at a pressure of 3.0 Torr, conditions previously used successfully in this laboratory and by other authors [37,39,43,52]. A vacuum of approximately 10−3 Torr was also created before treating the pieces. Previous research has explored nitriding treatments at various durations to determine the optimal time, considering factors such as temperature, current, and gas concentration [40,43]. The thermochemical treatment was conducted for 4, 6, 8, and 10 h to determine the optimal treatment time and its influence on the thickness of the nitrided layer [36,38]. All samples were prepared in triplicate to verify reproducibility.

2.3. SEM and EDS

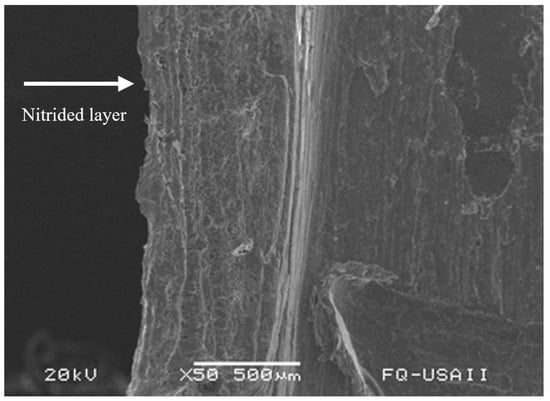

The electrode surface of X70 steel and materials having undergone thermochemical treatments at different times were evaluated using a scanning electron microscope on a cross-section to determine the nitride layer’s thickness after 10 h of treatment. The EDS were also analyzed to obtain qualitative information about the elemental composition of the surface of the blank samples and materials under different conditions.

2.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XDR)

The spectrum was recorded by a Bunker 2D PHASER diffractometer (35 kV, 20 mA, Japan) with Cu Ka radiation () at a scan rate of 2°/min, in the 2θ angle range of 10° to 90°.

2.5. Corrosion Protection Measurements

Corrosion tests were performed using electrochemical techniques: open circuit potential (OCP), potentiodynamic polarization curves, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, using an ACM Instruments Gill AC potentiostat and an electrochemical cell with three electrodes—a working electrode (X70 steel and X70 nitrided steel), an Ag-AgCl reference electrode, and an auxiliary graphite electrode. Simulated soil solution was used as the corrosive medium, the chemical composition of which is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of simulated soil solution [11,12,13,14,16,17,18,19,20].

OCP measurements were recorded for 20 min until the potential stabilized. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements were performed by applying AC signal with an amplitude of ±10 mV over a frequency range from 10 khz to 0.01 Hz. Potentiodynamic polarization curves were obtained by polarizing the working electrode from ±1000 mV relative to its corrosion potential at a scan rate of 60 mV/min. All tests were conducted in triplicate to verify reproducibility and were based on other authors’ tests and ASTM standards (G03, G59, and G106) [2,6,7,8,53,54].

2.5.1. Corrosion Inhibition Efficiency (%η)

The corrosion inhibition efficiency (%η) was calculated from the corrosion density (icorr) using the following relation:

where (icorr) is the corrosion current density without treatment and (icorr treatment) is the corrosion current density with thermochemical treatment [6,49,50,51].

2.5.2. Calculation of the Electrochemical Double Layer Cdl

Based on literature, impedance values were used to determine the electrochemical double layer capacitance (Cdl), obtained using Equation (2):

where is the frecuency at which imaginary component of the impedance is maximum, and Rct is the charge transfer resistance [49,50,51].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SEM and EDS Analysis

3.1.1. Blank (Steel X70)

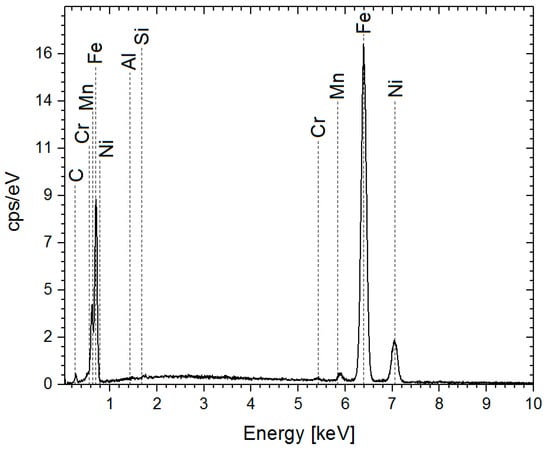

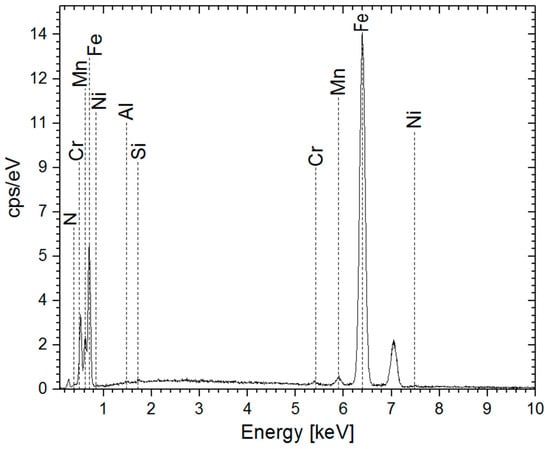

EDS analysis of the blank steel X70 steel sample showed a carbon content of 14 at.% (Figure 1 and Table 2), along with other alloying elements such as Al, Si, Mn, Cr, and Ni. This is consistent with previously reported compositions [15,17,25,26,27,28].

Figure 1.

EDS spectra of the blank sample.

Table 2.

The results show the percentage of the elements present in the blank sample.

3.1.2. EDS of Nitrided Steel with 4 h of Treatment

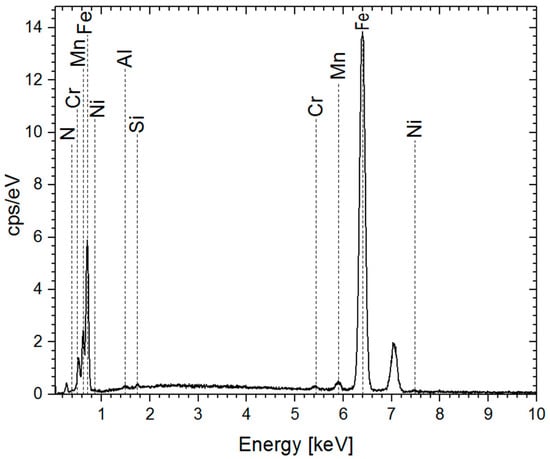

The results of the EDS analysis demonstrated the main elements presented in nitrided steel after 4 h of treatment (see Figure 2 and Table 3). The analysis reveals the presence of nitrogen due to the plasma nitriding process, which is absent in the blank sample.

Figure 2.

EDS spectra of the sample after 4 h of treatment.

Table 3.

The results show the percentage of the elements present in the sample after 4 h of treatment.

3.1.3. EDS of Nitrided Steel with 6 h of Treatment

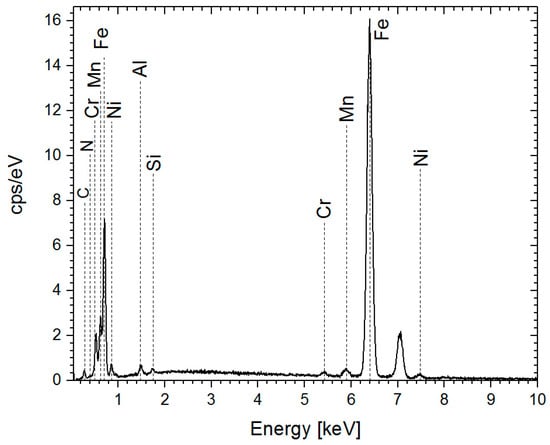

EDS analysis revealed a higher nitrogen content in the nitrided steel after 6 h of treatment compared to 4 h (Figure 3 and Table 4). This indicates that a longer treatment time leads to increased nitrogen incorporation.

Figure 3.

EDS spectra of the sample after 6 h of treatment.

Table 4.

The results show the percentage of the elements present in the sample after 6 h of treatment.

3.1.4. EDS of Nitrided Steel with 8 h of Treatment

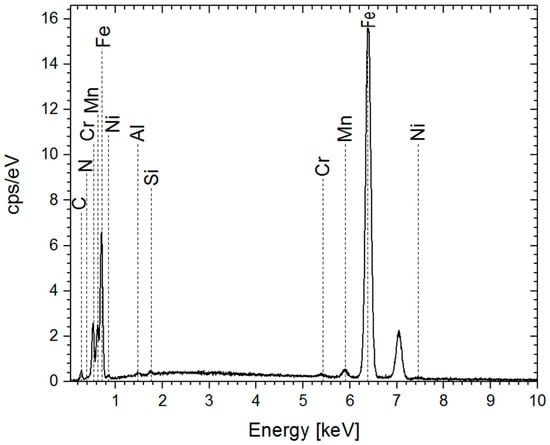

EDS analysis showed that the nitrogen concentration in the nitrided steel did not increase further after extending the treatment time from 6 to 8 h (Figure 4 and Table 5).

Figure 4.

EDS spectra of the sample after 8 h of treatment.

Table 5.

The results show the percentage of the elements present in the sample after 8 h after treatment.

3.1.5. EDS of Nitrided Steel with 10 h of Treatment

EDS analysis revealed that the nitrided steel treated for 10 h exhibited the highest nitrogen concentration compared to other treatment durations (Figure 5 and Table 6).

Figure 5.

EDS spectra of the sample after 10 h of treatment.

Table 6.

The results show the percentage of the elements present in the sample after 10 h of treatment.

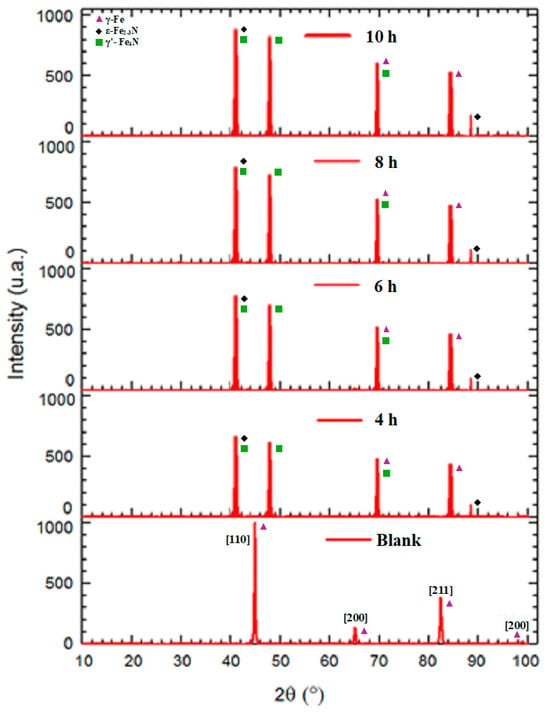

3.2. X Ray Diffraction (XRD)

Figure 6 shows the XRD patterns of the base X70 steel and the plasma-nitrided samples at different treatment times. The base material exhibits peaks corresponding to the BCC [110], [200], and [211] planes at 45°, 65°, and 82°, respectively, and the FCC [220] plane at 97°. This is consistent with reported XRD patterns for X70 and other HSLA steels [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Following plasma nitriding, new peaks appear at approximately 42° (γ’-Fe4N and ε-Fe2-3N), 48° (γ’-Fe4N), 69° (γ-Fe and γ’-Fe4N), 82°, and 88° (γ-Fe and ε-Fe3N), in agreement with previous studies [22,39,42,43,55]. The intensity of these nitride peaks increases with nitriding time, consistent with observations in other nitrided alloys [43,44,45]. CrN peaks, observed in some other steels [39,40,42,44], were not detected in the present study.

Figure 6.

XRD patterns of the blank X70 steel and plasma-nitrided X70 steel samples at different treatment times.

3.3. Electrochemical Reactions

The material’s electrochemical behavior is represented for the following reactions. The third reaction represents the dissolution of the iron, the fourth and five are the cathodic reaction, with the primary reaction being the evolution of hydrogen, and the sixth and seven reactions are the species that contributed to the process of stress corrosion cracking (SCC). Reaction eight is due to corrosion products formed on the steel surface [16,27,29,31].

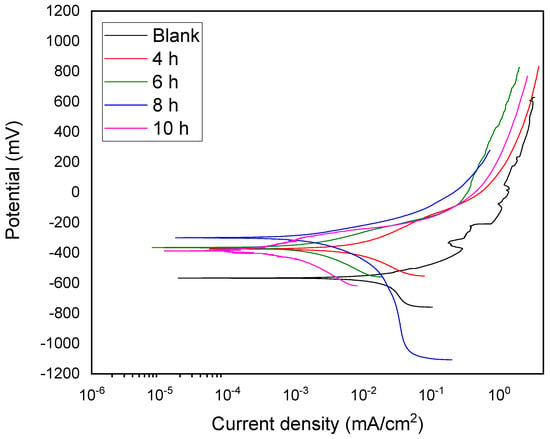

3.4. Potentiodynamic Polarization Curves

Figure 7 presents the potentiodynamic polarization curves of the blank X70 steel and plasma-nitrided samples in a simulated soil solution. The blank sample exhibited an open-circuit potential (Ecorr) of approximately −707 mV, consistent with reported values for X70 and similar steel grades in near-neutral solutions (−700 to −780 mV), which can vary depending on surface finish and pH [11,12,26]. The anodic branch of the blank sample showed active dissolution between −509 mV and −195 mV, with current fluctuations likely due to the formation and subsequent breakdown of corrosion products (oxides and oxyhydroxides), potentially leading to pitting corrosion [16,17,18,24,48]. The cathodic branch indicated a mass-transfer-controlled oxygen reduction process. Hydrogen evolution, the primary cathodic reaction for X70 steel in this environment, was consistent with an activation-controlled anodic reaction and was a significant factor in stress corrosion cracking (SCC) [26,27].

Figure 7.

Polarization curves of the blank and plasma-nitrided material at different treatment times evaluated in simulated soil solution.

The nitrided samples showed a positive shift in Ecorr compared to the blank samples, with the 8 h treatment exhibiting the noblest Ecorr. However, the 10 h treatment showed a slightly more active Ecorr than the 4, 6, and 8 h treatments. The cathodic branches of the nitrided samples revealed a decrease in the cathodic slope with increasing nitriding time, suggesting that the treatment hinders hydrogen reduction kinetics. This behavior, attributed to the formation of a nitrided layer containing Fe3N, indicates improved corrosion resistance due to the plasma nitriding treatment [41,42].

Table 7 summarizes the electrochemical parameters, averaged from three measurements. Generally, the corrosion current density (icorr) decreased with increasing treatment time. The efficiency (η%), calculated using Equation (1), also increased with treatment time. The sample nitrided for 10 h exhibited the highest corrosion resistance, with a corrosion rate two orders of magnitude lower than that of the blank material. This improvement in corrosion resistance with increased nitriding time, reflected in the decrease in icorr, is consistent with previous findings for similar steels [36,40,41,46].

Table 7.

Electrochemical parameters obtained from the polarization curves of the blank and nitrided steel with different treatment times.

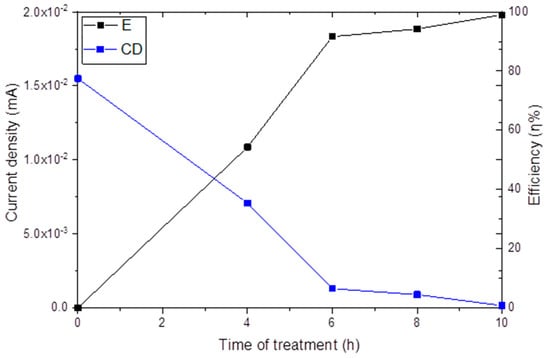

3.5. Influence of Time Treatment in Current Density and Efficiency

Figure 8 presents a graph of the current density and efficiency vs. plasma nitriding treatment time which was obtained using the values of the potentiodynamic polarization. Table 8 summarized the behavior of material under different treatments time, the percentage of nitrogen obtained and how it influences their current density. The lowest current density was achieved after 10 h of plasma nitriding treatment, demonstrating the effectiveness of longer treatment times in reducing current density and increasing the efficiency in electrochemical tests [36,41,43,46].

Figure 8.

Graph of current density (CD) and efficiency (E) vs. plasma nitriding treatment time (TT).

Table 8.

Comparison of treatment time, concentration of nitrogen, and Icorr in the pieces studied at different treatment times.

3.6. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

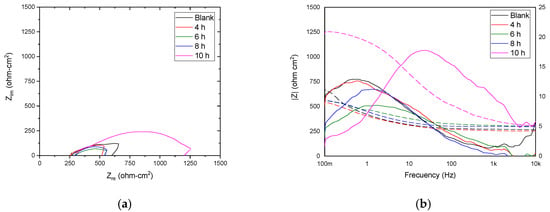

Figure 9a show the Nyquist diagrams of the blank X70 steel and the plasma-nitrided samples at different treatment times, measured in a simulated soil solution. The data represents the average of three measurements. Prior to the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements, the Nyquist diagram of the blank sample exhibits a decrease in the real impedance as a function of frequency, related to adsorption of corrosive species. The nitrided samples treated for 4, 6, and 8 h show a decrease in diameter in the capacitive loop, potentially indicating increased dissolution. In contrast, the 10 h nitrided sample exhibits a larger capacitive loop, suggesting the formation of a protective and adherent corrosion product layer, leading to increased corrosion resistance [36,40].

Figure 9.

Nyquist (a) and Bode diagrams (b) (modulus format) of the impedance and phase angle of the blank samples and materials with different treatment times evaluated in simulated soil solution.

The Bode plots (Figure 9b) were analyzed based on frequency regions: low frequencies (<1–10 Hz) corresponding to surface processes, intermediate frequencies (10–1000 Hz) to charge transfer processes, and high frequencies (>1000 Hz) to electrolyte resistance [40,49]. The impedance modulus plot of the blank X70 steel shows a high-frequency plateau, indicating the absence of a significant surface layer. In contrast, the sample nitrited for 10 h exhibits a higher impedance modulus at high frequencies, suggesting the presence of a surface layer, likely composed of metal hydroxide-type compounds. At low and intermediate frequencies, all samples exhibit two linear regions in the log|Z| vs. log|f| plot, indicative of two-time constants and corresponding to the two capacitive loops observed in the Nyquist diagrams [48].

From the Bode diagram in its phase angle format, in the high frequency region, it was viewed that the phase angle tends to zero at frequencies greater than 1000 Hz. In the intermediate frequency region, the evolution of a first-time constant was observed whose maximum angle was 18° at 10 h of plasma nitriding treatment. The presence of the first time constant for the blank conditions was visualized in the low frequency region, with 4, 6, and 8 h of plasma nitriding treatment. The shift from left to right and the increase in the phase angle were associated with an increase in its capacitive properties and the formation of protective and adherent corrosion products [39,48].

Table 9 presents the electrochemical parameters extracted from the EIS data. The constant phase element (CPE) parameters, CPEdl (double-layer capacitance), and CPEf (film capacitance), provide insights into the surface characteristics. Higher CPE values generally indicate a more protective surface with a higher concentration of adsorbed protective species. Conversely, lower CPE values suggest increased dissolution and the presence of aggressive ions. The CPE values are related to the corresponding resistance values, Rct (charge transfer resistance) and Rf (film resistance). For the 4 h treatment, Rf decreased, while for longer treatment times, Rf increased, likely due to the higher nitrogen concentration in the nitrided layer. Rct decreased for the 6 and 8 h treatments but increased for the 4 and 10 h treatments, correlating with the observed corrosion rates [7]. The solution resistance (Rs) increased with treatment time, particularly for the 6, 8, and 10 h treatments, possibly due to the formation of reaction products in the solution resulting from the thermochemical treatment.

Table 9.

Electrochemical parameters used to fit the EIS data and Cdl for the blank and plasma-nitrided material at different treatment times. The average error was less than 5% for the simulated equivalent electrical circuits.

The CPE exponents, n and nf, provide information about surface roughness. Values close to 0.5 suggest high surface roughness and a significant contribution from mass transport processes through pores in the corrosion product layer [7]. Conversely, values close to 1 indicate lower surface roughness and reduced metal dissolution. In this study, the lowest n and nf values were observed for the 4 and 6 h treatments, indicating higher surface roughness, while the highest values were observed for the 10 h treatment, suggesting a smoother, less actively dissolving surface.

The double-layer capacitance (Cdl), calculated using Equation (2), decreased with increasing plasma nitriding time, consistent with the formation of a protective film. Similar trends in capacitance and resistance values have been reported for corrosion inhibitors [49,50,51].

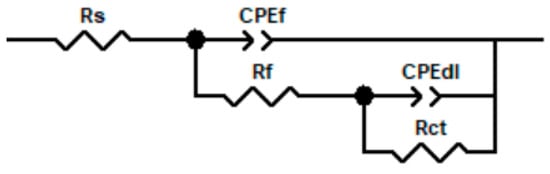

Figure 10 presents the equivalent circuit used to model the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data of the blank and nitrided steel samples at different treatment times in the simulated soil solution. The circuit consists of the solution resistance (Rs), the charge transfer resistance (Rct), in parallel with a constant phase element (CPEdl) representing the double-layer capacitance, and the film resistance (Rf), in parallel with a second constant phase element (CPEf) representing the capacitance of the nitride film. A CPE was used instead of a pure capacitor to account for surface inhomogeneities, such as roughness and non-uniform current distribution, which result in depressed semicircles in the Nyquist plots [30,38,39,48,49,50,51]. The impedance and phase angle are frequency-dependent, as described by the following equations:

where Y is the admittance of the system, a factor that combines properties related to the surface of electroactive species and is independent of the frequency, j is the imaginary unit (), w is the angular frequency (2f), f is the frequency, and n is related to the slope of log|Z| vs. log|f| [14]. If n is equal to 1, the CPE is an ideal capacitor, where Y is equal to the capacitance. However, if 0.5 < n < 1, then the CPE describes a distribution of dielectric relaxation times in the frequency range [13,38,39,48,49,50,51]. The calculated parameters obtained for the EIS data fitting for blank and nitrided steel at different treatment times are summarized in Table 9.

Figure 10.

Equivalent electrical circuits used to simulate EIS data.

For the 10 h treatment, Rct is much higher than other conditions, indicating enhanced corrosion resistance due to protective corrosion products, corroborated by polarization curves. When the n parameter is close to 1, indicating low metal surface roughness. All conditions had similar n values attributed to similar surface roughness.

3.7. Cross-Section Analysis

The nitrided layer thickness after 10 h of treatment was determined to be 678.75 µm from SEM micrography of the cross-section (Figure 11). This thickness measurement is supported by EDS, XRD, and electrochemical (CPP and EIS) analyses, which also indicate the formation of a nitrided layer. The observed relationship between treatment time and nitrided layer thickness is consistent with previous studies [4,38,40,44].

Figure 11.

Cross-section micrography of steel nitrided with 10 h of treatment.

4. Conclusions

- Correct formation of the nitride layer and its behavior with varying treatment times was confirmed.

- Formation of the iron nitrides ε-Fe2-3N and γ-Fe4N indicates a clear formation of the nitrided layer. Increasing the plasma nitriding treatment time increases the intensity of the nitride peaks.

- Plasma nitriding significantly reduces corrosion density by up to three orders of magnitude compared to the blank, with 10 h of treatment providing the best results. The variation in Ecorr and Icorr were mainly due to the reaction kinetics in the formation of corrosion products on the nitrided surface.

- According to the current density graph against treatment time, the 10 h plasma nitriding treatment provides the best corrosion resistance and efficiency, making a long treatment unnecessary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A.G.N. and J.U.C.; methodology, O.A.G.N. and A.T.I.; software, O.A.G.N. and A.F.N.; validation, O.A.G.N., A.T.I., A.F.N. and J.U.C.; formal analysis, O.A.G.N., A.T.I., A.F.N. and J.U.C.; investigation, O.A.G.N., A.T.I. and H.M.V.; resources, A.T.I., J.U.C., H.M.V. and E.C.M.C.; data curation, O.A.G.N. and A.F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, O.A.G.N.; writing—review and editing, O.A.G.N.; visualization, O.A.G.N. and A.F.N.; supervision, H.M.V., J.U.C., E.C.M.C. and A.T.I.; project administration, O.A.G.N., A.T.I., A.F.N., E.C.M.C. and J.U.C.; funding acquisition, O.A.G.N., A.T.I., A.F.N., E.C.M.C. and J.U.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to the CIICAp-UAEM, FCQeI-UAEM, and ICF-UNAM for the electrochemical test, characterization chemical, and laboratory supports.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sharma, L.; Chhibber, R. Microstructure evolution and electrochemical corrosion behaviour of API X70 line pipe Steel in different environments. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2019, 171, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Vázquez, A.; Rodríguez-Gómez, F.J.; Negrón-Silva, G.E.; González-Olvera, R.; Ángeles-Beltrán, D.; Palomar-Pardavé, M. Fluconazole and fragments as corrosion inhibitors of api 5l × 52 steel immersed in 1M HCl. Corros. Sci. 2020, 174, 108853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtadi-Bonab, M.A.; Ariza-Echeverri, E.A.; Masoumi, M. A Comparative investigation of the effect of microstructure and crystallographic data on stress-oriented hydrogen induced cracking susceptibility of API 5L X70 pipeline steel. Metals 2022, 12, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.E.L.; Franco, A.R.; Vieira, E.A. Influence of plasma nitriding pressure on microabrasive wear resistance of a microalloyed steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 1694–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadala, I.M.; Alfantazi, A. Electrochemical behavior of API-X100 pipeline steel in NS4, near-neutral, and mildly alkaline pH simulated soil solutions. Corros. Sci. 2014, 82, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashuga, M.E.; Olasunkanmi, L.O.; Verma, C.; Sherif, E.-S.M.; Ebenso, E.E. Experimental and computational mediated illustration of effect of different substituents on adsorption tendency of phthalazinone derivatives on mild steel surface in acidic medium. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 305, 112844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameri, S.; Boughrara, D.; Chopart, J.P.; Kadri, A. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of API 5L X52 pipeline Steel in soil environment. Anal. Bioanal. Electrochem. 2021, 13, 239–263. [Google Scholar]

- Lucio-Garcia, M.A.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J.G.; Casales, M.; Martinez, L.; Chacon-Nava, J.G.; Neri-Flores, M.A.; Martinez-Villafañe, A. Effect of heat treatment on H2S corrosion of a micro-alloyed C–Mn steel. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 2380–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.M.M.; Mohtadi-Bonab, M.A.; Ouellet, R.; Szupunar, J. A Comparative study of the role of hydrogen on degradation of the mechanical properties of API X60, X60SS, and X70 pipeline steels. Steel Res. Int. 2019, 90, 1900078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon Fabián, P.R.; Arturo, C.T.; Araceli, E.M.; Sergio, G.N.; Manuela, D.C. Study of flow-assisted corrosion (FAC) in a 5L X-70 API steel in a brine-H2S-CO2 system using the rotating cylindrical electrode. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 066550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo, L.R.; García, R.; López, V.H.; Contreras, A. Electrochemical assessment of X70 steel with non-conventional heat treatment. MRS Adv. 2017, 2, 2819–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Du, C.; Li, X. Effect of pH Value on the Crack Growth Behavior of X70 Pipeline Steel in the Dilute Bicarbonate Solutions. Mater. Trans. 2015, 56, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cheng, Y.F. Effect of stress on corrosion at crack tip on pipeline steel in a near-neutral pH solution. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2016, 25, 4988–4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.H.S.; Moreira, E.D.; Siqueira, P.; Gomes, J.A.C.P. Effect of cathodic potential on hydrogen permeation of API grade steels in modified NS4 solution. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 597, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.F.; Niu, L. Mechanism for hydrogen evolution reaction on pipeline steel in near-neutral pH solution. Electrochem. Commun. 2007, 9, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidi, M.; Bahalaou Horeh, S. Investigating the mechanism of stress corrosion cracking in near-neutral and high pH environments for API 5L X52 steel. Corros. Sci. 2014, 80, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.Q.; Tang, X.; Cheng, Y.F. Characterization of corrosion of X70 pipeline steel in thin electrolyte layer under disbonded coating by scanning Kelvin probe. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quej-Aké, L.M.; Galván-Martínez, R.; Contreras-Cuevas, A. Electrochemical and Tension Tests Behavior of API 5L X60 Pipeline Steel in a Simulated Soil Solution. Mater. Sci. Forum 2013, 755, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarola, J.M.; Calderón-Hernández, J.W.; Conde, F.F.; Marcomini, J.B.; de Melo, H.G.; Avila, J.A.; Bose Filho, W.W. Corrosion Behavior and Microstructural Characterization of Friction Stir Welded API X70 Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 5953–5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.H.S.; Gomes, J.A.C.P. Environmentally induced cracking of API grade steel in near-neutral pH soil. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2009, 31, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Sivaprasad, S.; Das, N.; Chattoraj, I. Study of electrochemical behavior, hydrogen permeation and diffusion in pipeline steel. Mater. Sci. Forum 2021, 1019, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Xu, Z.; Chen, X. Effect of surface plasma nitriding on corrosion resistance of X80 pipeline Steel in a simulated soil solution of Yingtan area. Corros. Sci. Prot. Technol. 2015, 27, 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, P.; Yang, M. Effect of Temperature and Applied Potential on the Stress Corrosion Cracking of X80 Steel in a Xinzhou Simulated Soil Solution. Materials 2022, 15, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Cheng, Y.F. Hydrogen permeation and distribution at a high strength X80 steel weld under stressing conditions and the implication on pipeline failure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 45, 23100–23112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cui, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, K. Effect of cathodic protection potential on microbiologically induced corrosion behavior of X70 steel in a near neutral pH solution. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 066508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-Martínez, R.; Orozco-Cruz, R.; Carmona-Hernández, A.; Mejía-Sánchez, E.; Morales-Cabrera, M.A.; Contreras, A. Corrosion Study of Pipeline Steel under Stress at Different Cathodic Potentials by EIS. Materials 2019, 9, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, X.Z.; Du, C.W.; Li, J.K.; Li, X.G. Effect of hydrogen-induced plasticity on the stress corrosion cracking of X70 pipeline steel in simulated soil environments. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 658, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Li, X.G.; Cheng, Y.F. Mechanistic aspect of near-neutral pH stress corrosion cracking of pipelines under cathodic polarization. Corros. Sci. 2012, 55, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Islas, A.; Serna, S.; Campillo, B.; Colin, J.; Molina, A. Hydrogen Embrittlement behavior on microalloyed pipeline steel in NS-4 solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 7608–7624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, M.; Danaee, I.; Saebnoori, E.; Eskandari, H. Impedance studies on stress corrosion cracking behavior of steel pipeline in NS4 solution under ssrt test condition. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2021, 57, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Luo, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, G.; Zhu, L. Stress corrosion cracking behavior of X90 pipeline steel and its weld joint at different applied potentials in near-neutral solutions. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2019, 6, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Liu, J.; Huang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.F. Effect of cathodic protection potential fluctuations on pitting corrosión of X100 pipeline Steel in acidic soil environment. Corros. Sci. 2018, 143, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmanov, S.; Mukhacheva, T.; Tambovskiy, I.; Naumov, A.; Belov, R.; Sokova, E.; Kusmanova, I. Increasing Hardness and Wear Resistance of Austenitic Stainless Steel Surface by Anodic Plasma Electrolytic Treatment. Metals 2023, 13, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, F.; Ashrafizadeh, F.; Atapour, M.; Akbari-Kharaji, E.; Mokhtari, R. Anticorrosion performance of TiN coating with electroless nickel-phosphorus interlayer on Al 6061 alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 296, 127170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, D.; Quintana, I.; Dobránszky, J. Effects of Different Variants of Plasma Nitriding on the Properties of the Nitrided Layer. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019, 28, 5485–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Bahena, E.; Martínez, H.; Porcayo-Calderon, J.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J.G.; Martínez-Gomez, L. Corrosion behavior of nitrided Ni3Al intermetallic alloy in 0.5M H2SO4. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2018, 13, 11323–11334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, A.H.; Brühl, S.P.; Gómez, B.; Zampronio, M.A.; Miranda, P.E.V.; Feugeas, J.N. Pulsed-plasma-nitrided API 5L X-65 steel: Hydrogen permeability and microstructural aspects. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1998, 31, 3469–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Torres, N.; Porcayo-Calderon, J.; Martinez-Valencia, H.; Lopes-Cecenes, R.; Rosales-Cadena, I.; Sarmiento-Bustos, E.; Rocabruno-Valdés, C.I.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J.G. Corrosion Resistance of a Plasma-Oxidized Ti6Al4V Alloy for Dental Applications. Coatings 2021, 11, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larios-Galvez, A.K.; Vazquez-Velez, E.; Martinez-Valencia, H.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J.G. Effect of Plasma Nitriding and Oxidation on the Corrosion Resistance of 304 Stainless Steel in LiBr/H2O and CaCl2-LiBr-LiNO3-H2O Mixtures. Metals 2023, 13, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.; Çomakli, O.; Yazici, M.; Yetim, A.F.; BAYRAK, Ö.; ÇELIK, A. The effect of plasma oxidation and nitridation on corrosion behavior of CoCrMo alloy in sbf solution. Surf. Rev. Lett. 2017, 25, 1950024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braceras, I.; Ibáñez, I.; Dominguez-Meister, S.; Sánchez-García, J.A.; Brizuela, M.; Larrañaga, A.; Garmendia, I. Plasma nitriding of the inner surface of stainless steel tubes. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 355, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, J.; Miao, B.; Zhao, X.; Mao, C.; Wei, W.; Hu, J. Enhancement of wear resistance by sand blasting-assisted rapid plasma nitriding for 304 austenitic stainless steel. Surf. Eng. 2019, 36, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, M.K.; Majumdar, J.D.; Mukherjee, S.; Manna, I. Effect of Prior Cold Deformation and Nitriding Conditions on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Plasma Nitrided IF Steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2019, 50, 4319–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Guo, Y.-Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.-J.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, Y.-W.; Liang, Y.-S. Effect of Cr/CrNx transition layer on mechanical properties of CrN coatings deposited on plasma nitrided austenitic stainless steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 367, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Wear resistance and microstructure of the nitriding layer formed on 2024 aluminum alloy by plasma-enhanced nitriding at different nitriding times. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 066405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andalibi Fazel, Z.; Elmkhah, H.; Nouri, M.; Fattah-alhosseini, A. Effect of compound layer on the corrosion behavior of plasma nitrided AISI H13 tool steel. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 056412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Jia, W.; Hu, J. An enhanced rapid plasma nitriding by laser shock peening. Mater. Lett. 2018, 231, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, O.A.G.; Porcayo-Calderon, J.; Martinez, H.; Lopez-Sesenes, R.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J.G. Effect of plasma treatment of copper on its corrosion behaviour in 3.5% NaCl solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandes, I.S.; da Cunha, J.N.; Santana, C.A.; Rodrigues, J.G.A.; D’Elia, E. Application of an Aqueous Extracto f Cotton Seed as a Corrosion Inhibitor for Mild Steel in HCl Media. Mater. Res. 2021, 24, e20200235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, T.A.; da Cunha, J.N.; de Oliveira, G.A.; da Silva, T.U.; de Oliveira, S.M.; de Araújo, J.R.; Machado, S.D.P.; D’Elia, E.; Rezende, M.J. Nitrogenated derivatives of furfural as green corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in HCl solution. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 7104–7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Cardenas, M.Y.; Valladares-Cisneros, M.G.; Lagunas-Rivera, S.; Salinas-Bravo, V.M.; Lopez-Sesenes, R. Peumus boldus extract as corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in 0.5 M sulfuric acid. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2017, 10, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettelaei, M.; Soltani, R.; Rahimi, M. Microstructure and wear properties of plasma nitrided low alloy steel tubes. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 12, 126439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM G59-97; Standard Test Method for Conducting Potentiodynamic Polarization Resistance Measurements. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM G3-14; Standard Practice for Conventions Applicable to Electrochemical Measurements in Corrosion Testing. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Benarrache, S.; Benchatti, T.; Benhorma, H.A. Formation and Dissolution of Carbides and Nitrides in the Weld Seam of X70 Steel by the Effects of Heat Treatments. Ann. Chim. Sci. Mater. 2019, 43, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).