Abstract

Recent advances in nanotechnology have highlighted the transformative potential of carbon-based nanomaterials, such as carbon nanofibers, carbon nanotubes, and graphene, in cementitious systems. These materials have shown a remarkable ability to enhance the mechanical strength, fracture toughness, and overall functional performance of cementitious composites. Their nanoscale dimensions and exceptional intrinsic properties allow for effective stress bridging, crack arrest, and matrix densification. Despite these promising features, the current understanding remains limited, particularly regarding their application to concrete. Furthermore, literature lacks systematic, parallel evaluations of their respective effectiveness in improving both mechanical performance and long-term durability, as well as their potential to impart true multifunctionality to concrete structures. It is worth noting that significant and statistically significant improvements in fracture behavior were observed at specific nanofiller concentrations, suggesting strong potential for the material system in next-generation innovative infrastructure applications. Experimental results demonstrated that both CNTs and GNPs significantly enhanced the mechanical performance of concrete, with flexural strength increases of approximately 49% and 38%, and compressive strength improvements of 22% and 47%, respectively, at optimum contents of 0.6 wt.% CNTs and 0.8 wt.% GNPs. SEM analyses confirmed improved matrix densification and interfacial bonding at these concentrations, while higher dosages led to agglomeration and reduced performance. This gap highlights the need for targeted experimental studies to elucidate the structure-property relationships governing these advanced materials.

1. Introduction

Concrete is currently the most widely used construction material worldwide and provides the framework for most modern infrastructure due to its versatility, low cost, and relatively high compressive strength. However, all conventional cement-based materials are inherently brittle and have poor tensile strength, with limited resistance to cracking that might compromise the long-term durability and performance of the structure [1]. Among these, carbon-based nanomaterials, particularly carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs), have attracted growing interest due to their outstanding mechanical strength, high aspect ratios, large specific surface areas, and exceptional electrical and thermal conductivities [2,3,4,5,6]. These nanomaterials, when introduced into cementitious matrices, can refine the microstructure, bridge nanoscale cracks, and facilitate more effective stress transfer across the matrix, leading to improvements in both strength and toughness [7,8]. Additionally, CNTs and GNPs have been recently shown to significantly enhance the thermal and electrical properties of cement-based materials [9]. This enables the development of multifunctional concrete that provides self-sensing, thermal regulation, and structural health monitoring capabilities, thereby representing a major step toward the next generation of smart, energy-efficient construction materials [2,9].

Over the last two decades, many studies have been conducted on nanomaterials in cementitious materials to enhance the performance of traditional concrete. Among diverse nano-inclusions, carbon-based nanomaterials, such as CNTs and GNPs, have shown the greatest potential to enhance the mechanical properties and microstructures of cementitious composites. Due to their one-dimensional tubular structure, very high tensile strength, and elastic modulus, CNTs can play the role of nanoscale reinforcement bridges between them in a cement matrix by controlling crack initiation and growth [10,11,12]. This inclusion has been linked to enhancement in compressive, flexural, and tensile properties, as well as fracture toughness if good dispersion is achieved [13,14]. Meanwhile, graphene-based materials have a two-dimensional structure. Natural hardness, specific surface area, and chemical reactivity, which may help form stronger bonding with hydration products and denser microstructure [2,15,16]. Several recent studies also confirmed the beneficial influence of GNPs on the mechanical strength and durability of concrete [16,17]. It is well known from previous studies that the effectiveness of these novel nanomaterials is highly dependent on their dispersion quality; agglomeration can lead to elevated concentrations and thus reduce the reinforcing effect. In order to tackle this problem, ultrasonication and the addition of suitable surfactants or superplasticizers have been used for a homogeneous dispersion within the cement matrix [18,19,20,21]. In general, due to their unique nanoscale crack-bridging and microstructure refinement mechanisms, CNTs and GNPs have exhibited potential as efficient nano-reinforcements for enhancing strength, stiffness, and fracture behavior [8,22].

While there have been many works on the incorporation of CNTs and GNPs into cementitious materials, these have mainly focused on single nanomaterials or within certain ranges [11,23]. In a number of studies, findings are contradictory across reports, with variations in dispersion processes, mixing methods, and curing conditions, making it difficult to discern structure-property relationships. In addition, a few reports have investigated the mechanical behavior and microstructural evolution of nanomodified cement-based composites under the influence of a systematically varying amount of nanomaterial. Current research has mainly focused on the compressive strength, flexural response, and fracture characteristics required for subsequent evaluation of crack resistance and toughness [14,24]. Furthermore, few literature reports have compared CNTs and GNPs under identical experimental conditions. As a result, there is an urgent need for a systematic experimental investigation to determine how different levels of CNT and GNP addition affect the mechanical properties and microstructural characteristics of the composite in a consistent or comparable manner.

In the present work, we systematically investigate the effect of both CNTs and GNPs on the mechanical properties and microstructure of cement-based composites. For this purpose, a set of samples with varying nanomaterial contents, ranging from 0.2 to 1.2 wt.%, was prepared. This experimental study investigated compressive and flexural strengths, as well as microstructural features by SEM. Due to the same processing and testing conditions, a direct comparison can be made between CNT and GNP modified systems, which can help us to gain a clearer picture of the dispersion performance on the mechanical properties and it is also expected that the results of this study can offer a new perspective in the development of nanomodified cements with controlled performance for high-performance and safe constructions. Despite the extensive literature on CNT- and GNP-reinforced cementitious composites, several important limitations remain unresolved. A major source of inconsistency arises from the strong dependence of mechanical performance on nanomaterial dispersion quality, as different studies employ diverse dispersion techniques, surfactants, and mixing protocols. As a result, reported improvements often vary significantly and, in some cases, appear contradictory even for similar nanomaterial contents. In addition, the optimum dosages of CNTs and GNPs reported in the literature span a wide range, making it difficult to distinguish intrinsic nanomaterial effects from processing-related influences. These inconsistencies are further compounded by variations in mixed design, curing conditions, specimen geometry, and mechanical testing methodologies, which hinder direct comparison between CNT- and GNP-based studies. Moreover, while most previous investigations focus on compressive or flexural strength, fracture-related parameters—such as fracture energy—remain comparatively underreported, despite their critical importance for crack initiation and propagation in brittle cementitious materials. To address these limitations, the present study performs a systematic and parallel investigation of CNT- and GNP-modified concrete under identical materials, dispersion procedures, mix design, curing regime, and mechanical testing conditions. By varying only the type and concentration of the carbon-based nanomaterial, this approach enables a direct assessment of relative reinforcing efficiency, optimum dosage ranges, and the onset of performance degradation due to agglomeration. Furthermore, the mechanical characterization is extended beyond conventional strength metrics to include fracture energy, allowing a more comprehensive interpretation of nanoscale reinforcement mechanisms. The combined evaluation of flexural strength, compressive strength, fracture behavior, and SEM-based microstructural analysis directly addresses the unresolved inconsistencies identified in previous CNT- and GNP-based studies. Although carbon-based nanomaterials are also known to enhance the electrical and thermal functionality of cementitious composites, the present study focuses exclusively on their influence on the mechanical performance and microstructural characteristics of concrete. The electrical and thermal properties of similar nanomodified systems have been extensively investigated in our previous work [9]. The selected nanomaterial dosage range is further motivated by previous experimental studies of the authors on cement paste and mortar systems, where CNTs and GNPs within similar sub-percent weight fractions were shown to provide stable dispersion and reproducible improvements in mechanical and functional properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Specimens

The materials used in this study were ordinary Portland cement (OPC, Type II 42.5 R), tap water, and a combination of natural sand and graded aggregates, which were the primary ingredients of the cement-based mixtures. In all the mixes, the water-to-cement ratio was maintained at 0.65 to ensure sufficient workability for the homogeneous dispersion of nano-inclusions within the matrix. Although this water-to-cement ratio is higher than that typically used in structural concrete, it was intentionally selected to ensure sufficient workability and homogeneous dispersion of the carbon-based nanomaterials, as confirmed through preliminary mixing trials. This proportion corresponds to ratios commonly used in laboratory-scale nanomodified concretes, where achieving uniform dispersion is essential. The two types of nanomaterials involved in this study are carbon-based: multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs; Nanotech Port Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) and graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs; Avanzare Innovación Tecnológica S.L., La Rioja, Spain). The MWCNTs are of type 4060, possessing a high aspect ratio, lengths of 5–15 µm, diameters of 40–60 nm, and purity above 97%, whereas the GNPs, av-PLAT-7, had lateral dimensions around 7 µm, an average thickness of 3 nm, and 5–10 atomic layers. The selected nanomaterial contents (0.2–1.2 wt.% cem) were chosen based on prior experimental investigations by the authors on cement paste and mortar systems, in which CNTs and GNPs within this range were shown to provide effective reinforcement when adequate dispersion was achieved. The same dosage window was adopted in the present study to examine the transferability of the reinforcing mechanisms from paste and mortar to concrete, where the presence of aggregates introduces additional dispersion challenges and stress-transfer complexities. The selected range spans low, intermediate, and high nanomaterial contents, enabling the identification of optimum performance windows as well as the onset of degradation related to agglomeration. A polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer, Viscocrete Ultra 300 (Sika AG, Baar, Switzerland), served as a dispersing agent at a nanomaterial-to-dispersant weight ratio of 1:1 to ensure uniform dispersion and prevent agglomeration. Furthermore, Viscocrete Ultra 600 (Sika AG, Baar, Switzerland) was also used to maintain acceptable workability in the fresh mixtures.

In particular, the morphology and surface characteristics of both nanomaterials were examined prior to incorporation using SEM (Zeiss SUPRA 35 VP, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). The MWCNTs formed entangled tubular networks, whereas the GNPs exhibited a sheet-like, wrinkled morphology with a large exposed surface area. These characteristic structural features are expected to affect both the dispersion behavior and mechanical performance of the resulting composites. The main properties of the nanomaterials and characterization procedures have been described in detail in the work of Farmaki et al. (2025) [9]. It is worth noting that in this study, the polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer acted not only as a water-reducing admixture but also as an efficient dispersant for hydrophobic carbon nano-inclusions. Previous studies have shown that certain native cement additives can effectively disperse carbon nanomaterials in aqueous suspensions, achieving high homogeneity without the need for additional surfactants or chemical functionalization [19]. On the other hand, Alafogianni et al. (2016) [19] noted that the use of superplasticizers as dispersion agents for carbon nanomaterials is not a general rule and should always be verified experimentally for each system.

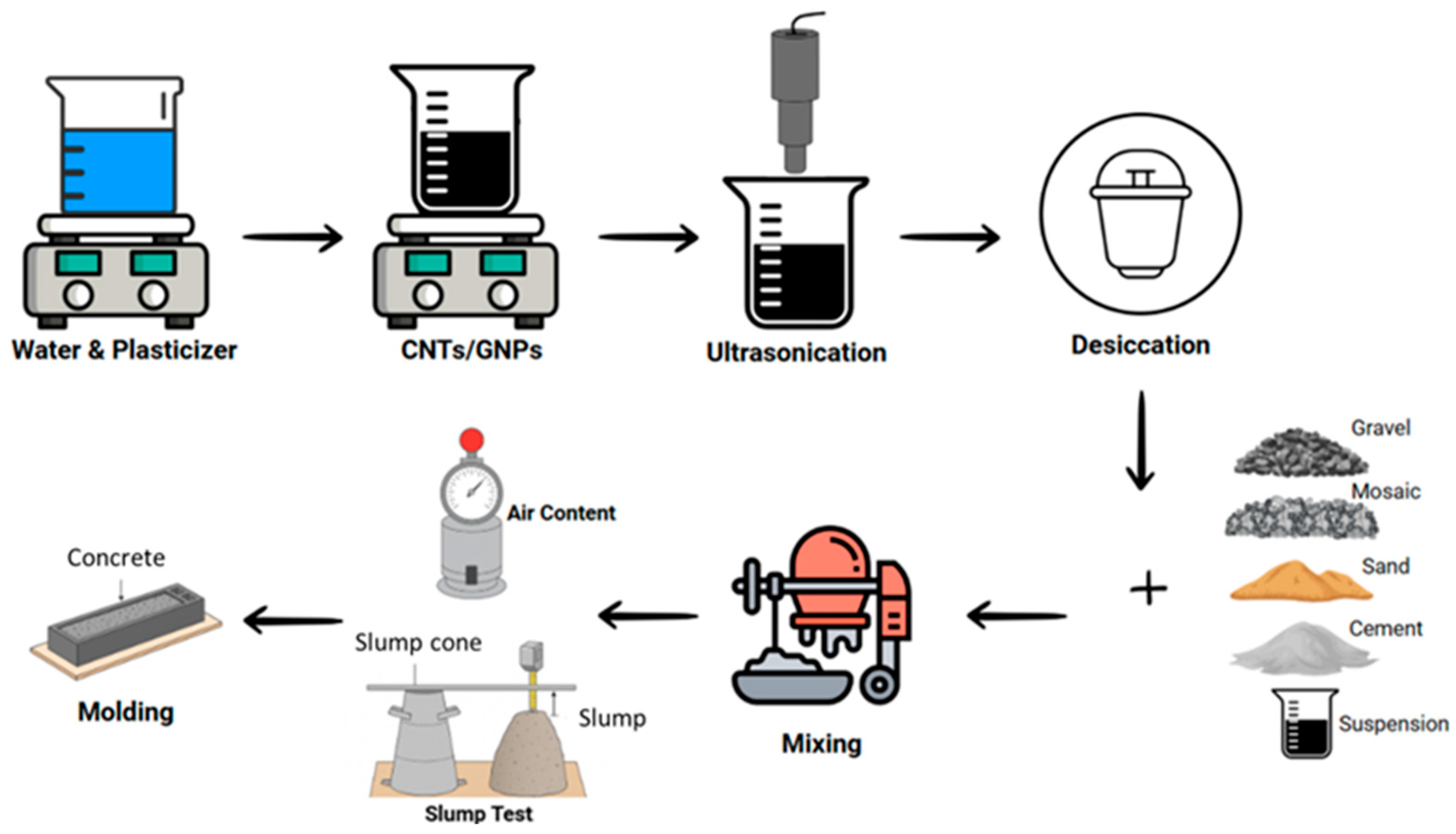

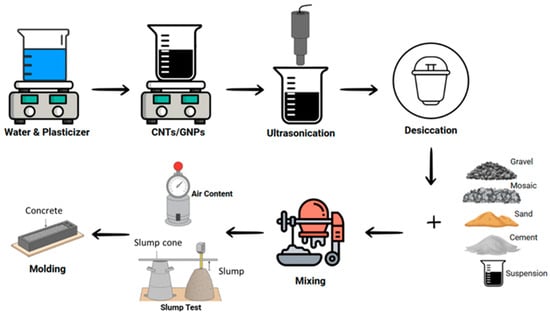

The overall procedure followed for the preparation and development of the nanomodified concrete specimens is schematically illustrated in Figure 1. The process consisted of successive stages: dispersion of carbon nanomaterials, preparation of nano-included aqueous suspensions, and subsequent incorporation into concrete mixtures. A multi-step approach was followed to achieve an effective dispersion of the carbon nanomaterials and their uniform incorporation within the concrete matrix. First, the aqueous solution was prepared by mixing tap water with the polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer ViscoCrete Ultra 300, along with the required dosage of either CNTs or GNPs under magnetic stirring. The dispersion protocol adopted in this study was selected based on prior systematic investigations by the authors, in which similar ultrasonication parameters and dispersing agents were validated for CNT- and GNP-based suspensions using complementary characterization techniques. In the context of the present work, dispersion quality was preliminarily verified through visual inspection and short-term stability assessment of the aqueous nanomaterial suspensions before incorporation into the concrete mixtures, confirming the absence of visible agglomerates or sedimentation over the time scale relevant to mixing and casting. Although no direct quantitative dispersion characterization (e.g., UV–vis spectroscopy or particle size analysis) was performed within the scope of the present study, the adopted protocol has been shown in previous work to provide stable and homogeneous dispersions under comparable conditions. This preliminary dispersion enabled homogeneous wetting of the nanoparticles and prevented the formation of large aggregates before sonication. The solution containing the nanostructure was then sonicated for 90 min at 50% amplitude using a Hielscher UP400S tip-ultrasonicator (24 kHz, 400 W; Hielscher Ultrasonics GmbH, Teltow, Germany) with a cylindrical sonotrode Ø22 mm. During sonication, the beaker with the suspension was kept in a cooling water bath to prevent overheating and maintain the suspension temperature below 30 °C. The selected parameters were established in previous work by the authors’ group as optimal for generating stable and homogeneous nanodispersions with minimal agglomeration [25]. After ultrasonication, a short vacuum-desiccation step was performed using a vacuum pump to remove entrapped air and enhance the colloidal stability of the nano-incorporated suspension.

Figure 1.

Overview of the preparation process for nanomodified concrete specimens reinforced with CNTs and GNPs.

Concrete mixtures were subsequently produced by incorporating the previously prepared nanosuspensions into a standard mix designed for a target strength class of C20/25, corresponding to 28-day compressive strengths of 20 MPa (cylindrical) and 25 MPa (cubic). In total, seven different mixes were prepared: one reference mix with no nano inclusion (plain) and six modified mixes containing either CNTs or GNPs at concentrations of 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.6%, 0.8%, 1.0%, and 1.2% by weight of cement. Before mixing, both the fine and coarse aggregates were dried at 120 °C for 48 h to remove residual moisture. Mixing was carried out according to the procedure outlined in BS EN 206 [26]. Initially, the dry ingredients were mixed for 1 min at a constant speed to ensure proper distribution, followed by the gradual addition of the nano-enhanced aqueous suspension. Thereafter, mixing at a constant speed continued for 3 min until proper mixing and uniform dispersion of nanomaterials were achieved. The water-to-cement ratio was kept constant at 0.65 for all batches, and minor adjustments to workability were made by adding small amounts of Viscocrete Ultra 600 superplasticizer when required. The fresh properties were determined immediately upon completion of the mixing procedure. The slump test, performed in accordance with ASTM C143 [27], yielded an average value of approximately 240 mm, while the air content, measured according to ASTM C231 [28], was maintained below 4% to ensure low porosity and reliable mechanical performance. Finally, the concrete was poured into oiled prismatic molds measuring 100 × 100 × 400 mm3, where it remained for 24 h. Following demolding, the specimens were cured by immersion in water maintained at 20 ± 2 °C under a humidity-controlled environment (100% RH) for 28 days according to ASTM C 192/C 192M-98 [28].

2.2. Testing Methods

2.2.1. Microstructural Analysis

The microstructural characteristics of the nanomodified concrete specimens were examined using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). These tests were performed on fractured surfaces obtained from compressive and flexural strength tests to directly observe the internal morphology and dispersed state of nano-inclusions within the cementitious matrix. The samples were oven-dried at 60 °C for 24 h to remove residual moisture and later coated with a thin layer of gold, ensuring electrical conductivity and minimizing charging effects during electron beam exposure.

Observations were performed using a Zeiss SUPRA 35 VP field-emission scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) under high-vacuum conditions, with an accelerating voltage of 5–15 kV. Different magnifications were used to identify morphological features including the distribution of CNTs and GNPs and their bonding with hydration products, the formation of calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) phases, and the presence of microcracks or voids. Representative micrographs obtained from each nanomodified concrete series enabled a qualitative comparison of the microstructural development as a function of nanomaterial type and concentration.

2.2.2. Mechanical Testing

Flexural performance of the nanomodified concrete was evaluated through four-point bending tests conducted in accordance with ASTM C1609/C1609M-12 [29]. The tests were carried out using a servo-hydraulic testing frame (Instron 8801, ±30 kN) equipped with a custom-designed four-point bending fixture developed according to ASTM C78-02 [30] and the dimensions of the test specimens. Prismatic specimens with nominal dimensions of 100 × 100 × 400 mm3 were tested under displacement control at a constant loading rate of 0.08 mm/min, with a span length of 300 mm, ensuring pure bending conditions as specified by the standard. Mid-Span deflection was continuously recorded using a Mitutoyo 543-450B extensometer (range = 25.4 mm; Mitutoyo Corp., Kawasaki, Japan) mounted on a yoke. For each mixture, three specimens were tested after 28 days of curing, and the flexural response was recorded as load–deflection curves. The modulus of rupture (MOR) and corresponding flexural strength were determined according to ASTM C1609.

The fracture toughness, expressed in terms of fracture energy, was derived from the load–deflection response obtained in the four-point bending tests on the nanomodified concrete. According to ASTM C1609/C1609M-12, the fracture energy was calculated as the area under the load–deflection curve up to a mid-span deflection equal to L/150 (≈2 mm for the tested geometry). This parameter represents the material’s ability to absorb mechanical energy and resist crack initiation and propagation under flexural loading.

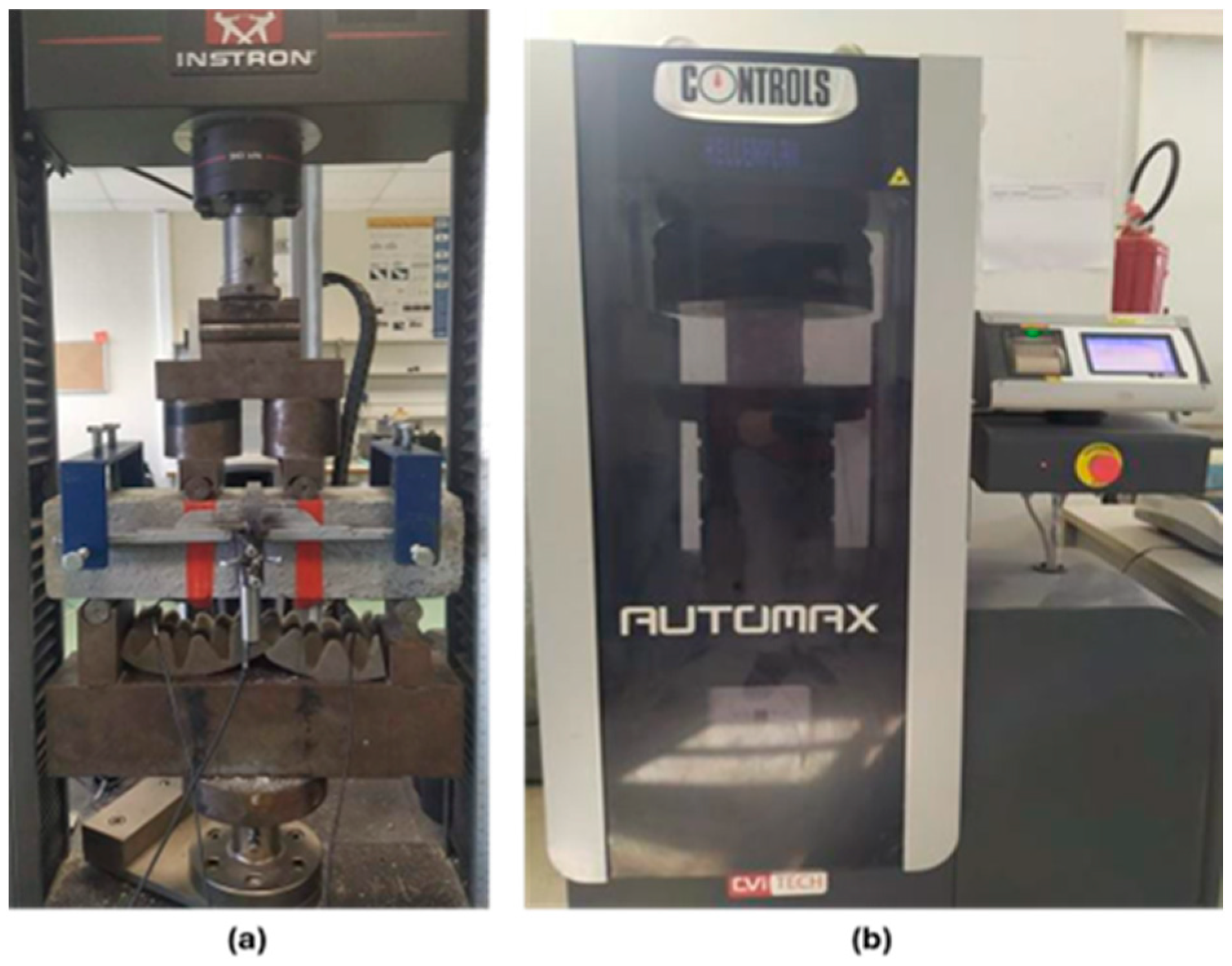

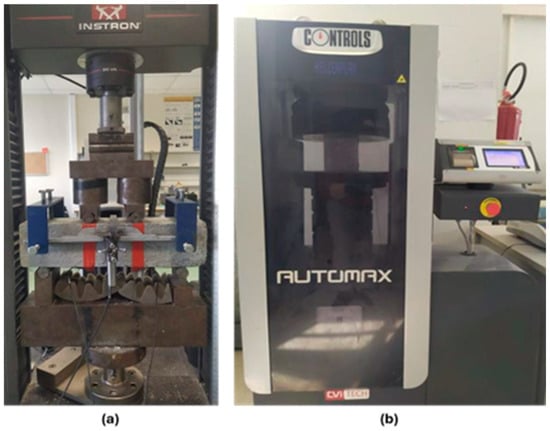

The compressive strength tests were performed using an AUTOMAX COMPACT-Line CVI-TECH compression testing machine (CONTROLS, S.p.A., Milan, Italy) suitable for testing cylindrical and cubic concrete specimens. The experiments were performed in accordance with the European standards EN 12390-3:2019 [31] and EN 12390-4 [32], which specifies the test procedure for determining the compressive strength of hardened concrete. The loading rate was kept constant at 0.6 ± 0.2 MPa/s until failure. Three specimens were tested for each nanomodified mixture, and the average value was reported as the representative compressive strength. The experimental setups for the four-point bending and compressive strength tests are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup for mechanical testing: (a) four-point bending test configuration for flexural strength evaluation (ASTM C1609), (b) compressive strength test setup performed in accordance with EN 12390-3:2019 and EN 12390-4:2019.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, the experimental results concerning the mechanical performance and microstructural characteristics of the CNT- and GNP-modified concrete mixtures are presented and discussed in detail. Compressive and flexural strengths were evaluated as a function of nanomaterial type and content, while SEM observations provided further insight into interactions between the nano-inclusions and the cementitious matrix. The combined analysis aims to establish the relationship between the microstructure and mechanical behavior of the nanomodified systems.

3.1. Flexural and Compressive Strength

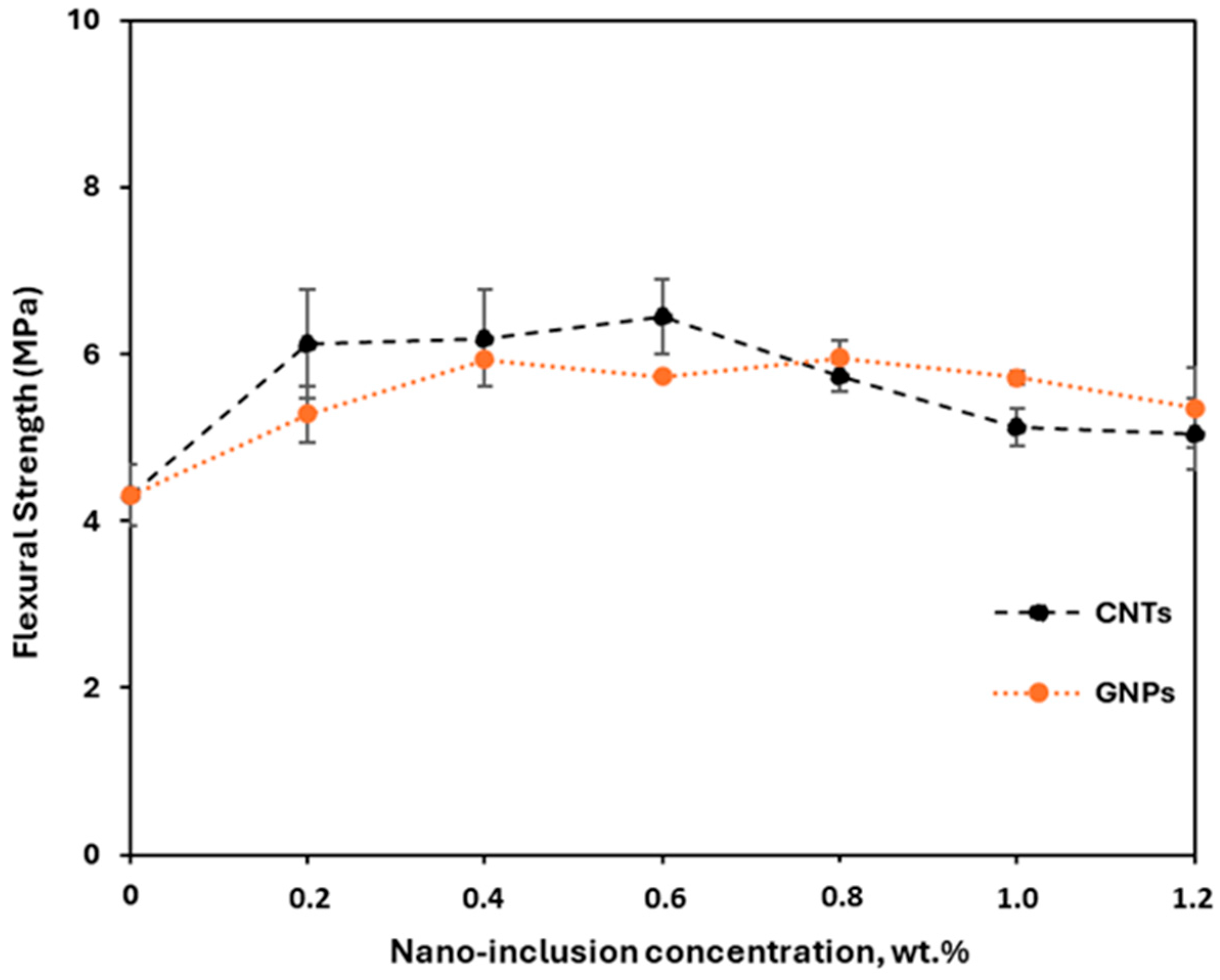

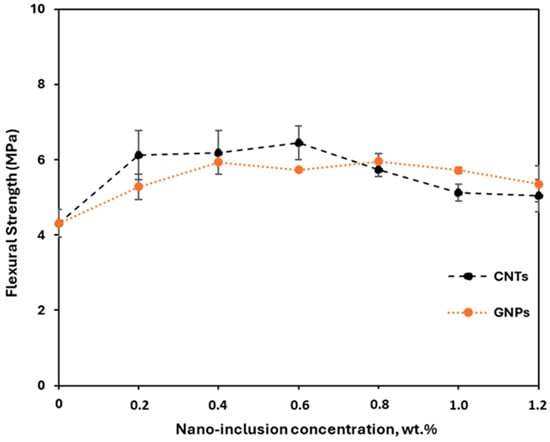

Figure 3 presents the variation in flexural strength with nano-inclusion content for the concrete modified with CNTs and GNPs. The percentage variation from the reference concrete is summarized in Table 1. Remarkable enhancements of the flexural performance were observed with the contribution of both CNTs and GNPs, especially at moderate nanomaterial contents. Specifically, the maximum improvements were observed at 0.6 wt.% CNTs (+49%) and 0.8 wt.% GNPs (+38%) compared to the control samples. It should be noted that, for the GNPs, the flexural strength is similar at 0.4 wt.%. This significant increase indicates that both nanomaterials were effectively dispersed within the cementitious matrix, enhancing nanoscale crack bridging, refining the microstructure, and improving flexural stress-transfer capacity. At higher nanomaterial contents (≥1.0 wt.%), a gradual decrease in strength was observed, attributed to the agglomeration of nano-inclusions, which act as stress concentrators and hinder load distribution. These findings are in agreement with previous studies that identified an optimum nanomaterial dosage and a subsequent decline in performance due to agglomeration effects [21,33]. Each data point represents the average of three independent tests, with error bars indicating one standard deviation. To distinguish general trends from potentially meaningful differences, we also considered the magnitude of the observed changes relative to the experimental scatter (standard deviation). At the identified optimum contents, the increase in flexural strength is substantially larger than the corresponding variability, supporting the reproducibility of the effect. In contrast, smaller differences between neighboring concentrations should be interpreted as trends within experimental scatter rather than as strictly distinct responses. Although formal statistical testing (e.g., p-values) was not conducted, the observed trends were highly reproducible across repeated experiments, and the percentage variation data provided in the corresponding tables further confirm the statistical relevance of the identified optimum dosages. Therefore, interpretation is based on variability-aware comparison, reproducibility across repeated measurements, and consistency with SEM observations. Overall, both CNTs and GNPs enhanced the flexural behavior of concrete; however, the improvement from CNTs was more profound, which is arguably due to their inherently higher aspect ratio and tubular geometry, which offer increased efficiency in crack bridging and load transfer mechanisms.

Figure 3.

Flexural strength of CNT- and GNP-modified concrete specimens as a function of nanomaterial content wt.% cement). Data points represent the average of three tested specimens, and the error bars indicate the range of all measurements.

Table 1.

Percentage variation in flexural and compressive strength of CNT- and GNP-modified concrete specimens relative to the reference concrete as a function of nanomaterial content (wt.% cement).

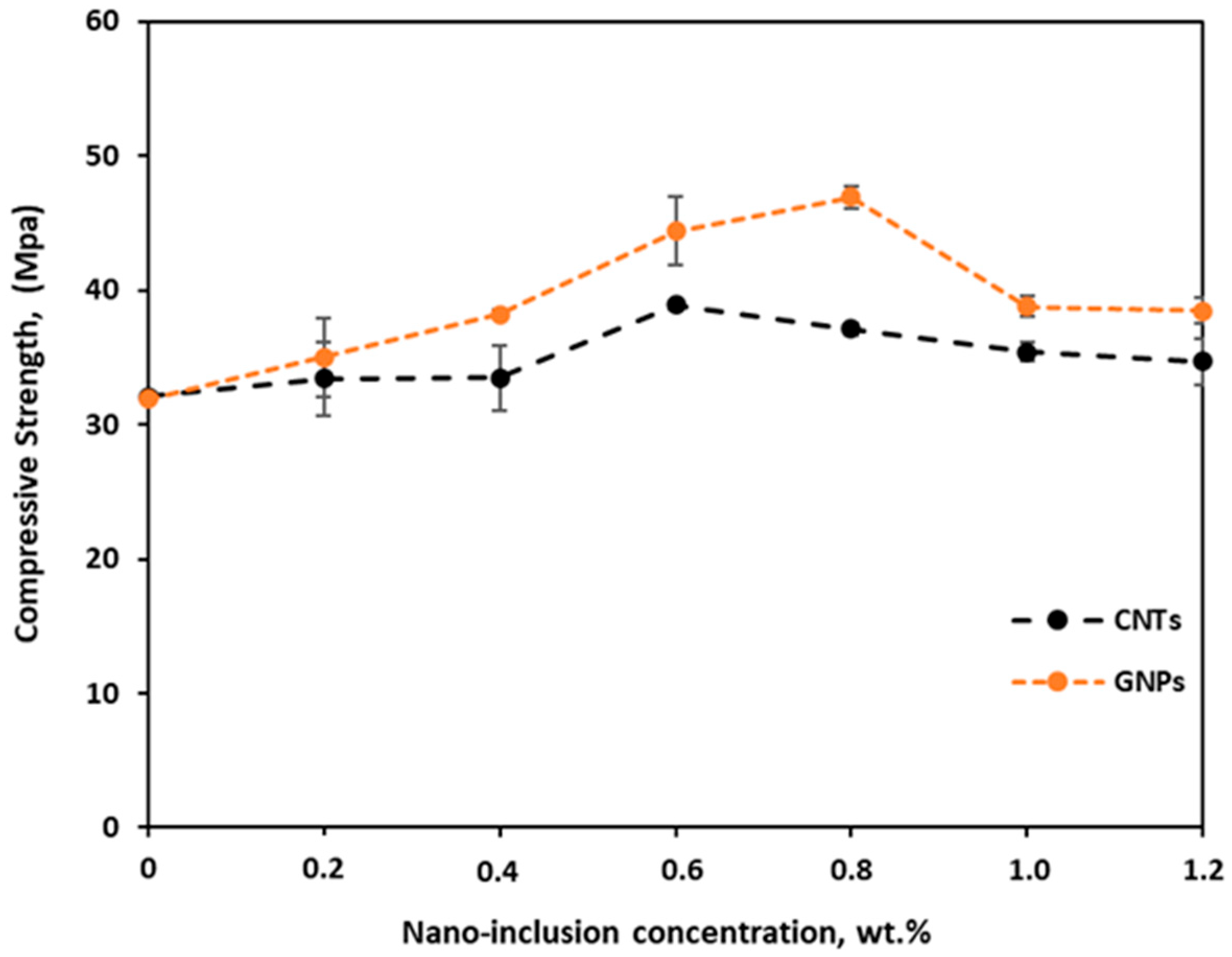

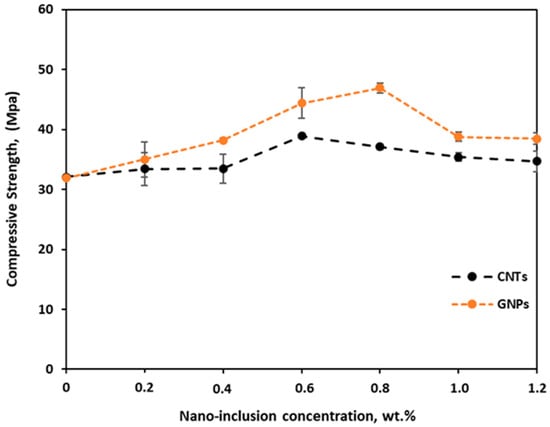

Figure 4 shows the compressive strength as a function of nano-inclusion content for CNT and GNP modified concrete specimens, while the corresponding percentage changes compared to the reference concrete are listed in Table 1. Both CNTs and GNPs were found to improve the compressive performance at moderate levels of nano-reinforcement compared to plain concrete. The maximum values were recorded at 0.6 wt.% CNTs (+21%) and 0.8 wt.% GNPs (+47%). It can be concluded that the nanoencapsulations significantly improved load transfer and densified the microstructure by filling microvoids and promoting stronger connectivity among the hydration products. Beyond these optimal concentrations, a gradual decrease in compressive strength was observed, likely due to nanomaterial aggregation, which introduces microdefects and stress-concentration regions that counteract the strengthening effect. Overall, both CNTs and GNPs effectively enhanced the compressive strength of concrete. However, GNPs demonstrated superior performance due to their larger specific surface area and two-dimensional morphology, which facilitates stronger interfacial interactions with the cementitious matrix.

Figure 4.

Compressive strength of CNT- and GNP-modified concrete specimens as a function of nanomaterial content (wt.% cement). Each value represents the mean of three specimens, and the error bars indicate the range of all measurements.

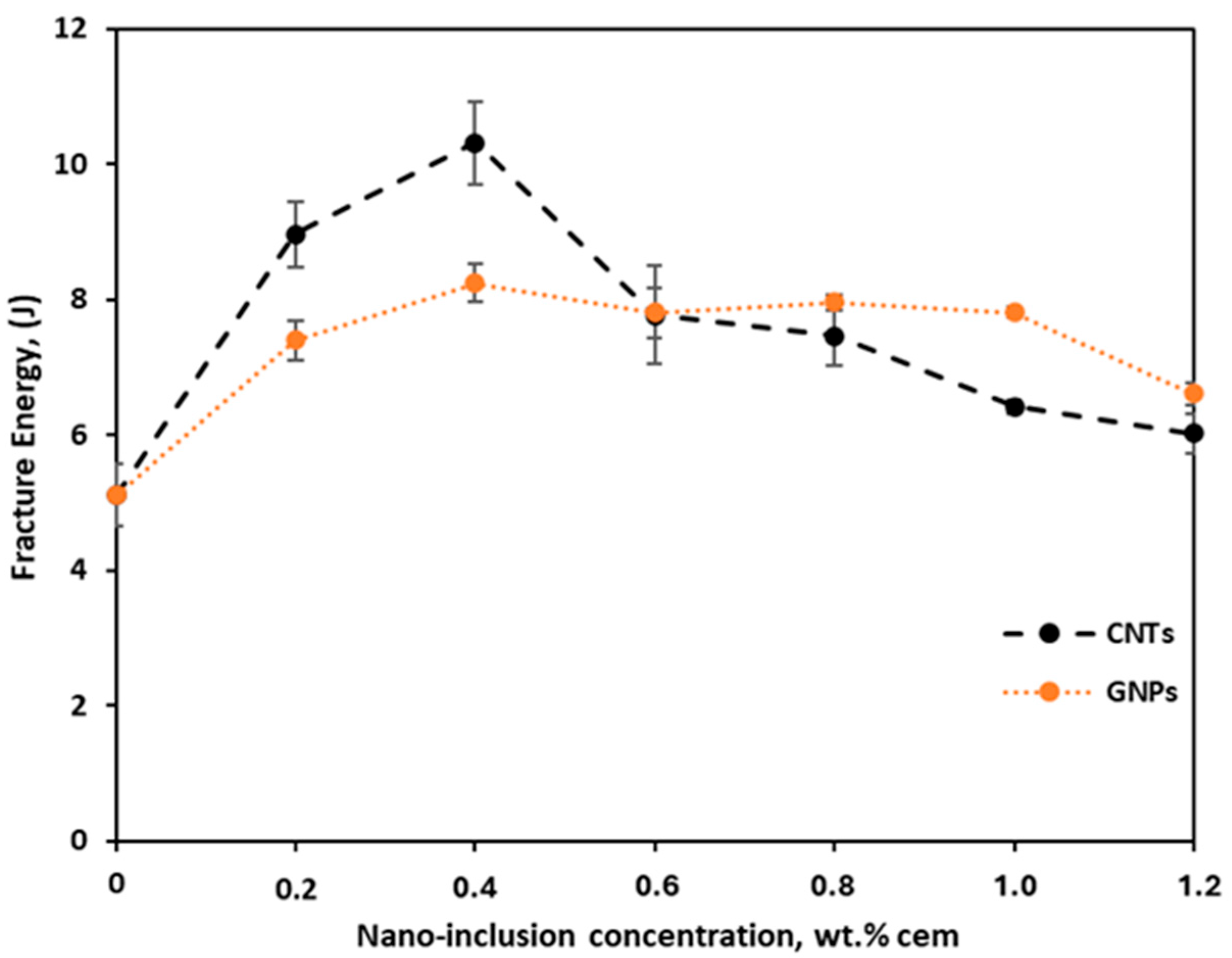

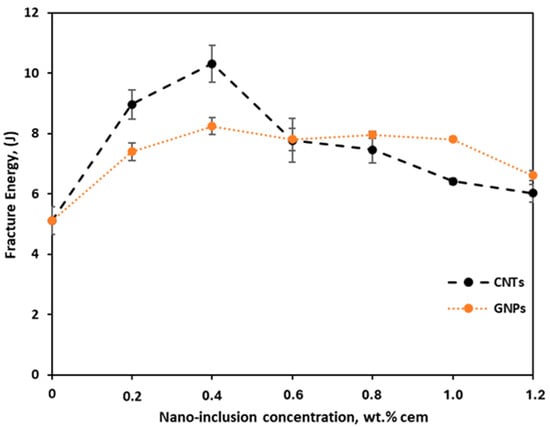

The fracture energy results, presented in Figure 5 and Table 2, follow a similar trend to the flexural strength, indicating that the addition of both CNTs and GNPs enhanced the concrete’s ability to absorb energy prior to failure. The presence of CNT led to a maximum increase of approximately 101% at 0.4 wt.%, while the GNP-modified specimens recorded their highest mean value at the same concentration, 61%. However, given the experimental dispersion (SD), no statistical difference is observed among the GNP contents of 0.4 wt.%, 0.6 wt.%, and 0.8 wt.%. Therefore, within this range, the optimal GNP content can be considered.

Figure 5.

Fracture energy of CNT- and GNP-modified concrete as a function of nanomaterial content (wt.% cement). The data corresponds to the mean of three tested specimens.

Table 2.

Percentage variation in fracture energy of CNT- and GNP-modified concrete specimens relative to the reference concrete.

Although the concrete specimens investigated in this study were plain (unreinforced), fracture energy was employed as a measure of the material’s inherent resistance to crack initiation and propagation under flexural loading, reflecting the intrinsic fracture resistance and energy dissipation capacity of the cementitious matrix rather than structural ductility. This approach is widely adopted in nanomodified cementitious composites, as nanoscale inclusions can significantly influence crack growth and energy dissipation mechanisms even without conventional fiber reinforcement. Similar observations have been reported for CNT- and GNP-reinforced cementitious composites, where the incorporation of nano-inclusions led to remarkable gains in fracture energy due to improved crack-bridging and matrix integrity [22,34]. Thus, the observed improvements in fracture energy do not indicate structural ductility but rather an increase in matrix fracture toughness and energy-absorption capacity, associated with improved nanoscale crack bridging and interfacial bonding.

Beyond the optimal nanomaterial content, the fracture energy decreased, likely due to CNT or GNP aggregation, which created weak zones and stress concentrators that counteracted the strengthening effect. Overall, the test results confirm that, particularly with CNTs, nanomodification significantly enhances the durability and crack resistance of plain concrete through microstructural refinement and improved stress redistribution at the nanoscale.

The good repeatability of the mechanical results, together with the consistent SEM observations across specimens and nanomaterial contents, provides indirect but strong evidence that adequate dispersion was achieved within the cementitious matrix.

3.2. Microstructural Characterization

The microstructural characteristics of the nanomodified concrete specimens were investigated through Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to evaluate the dispersion of the nano-inclusions within the cementitious matrix and to correlate these findings with the observed mechanical performance. Representative SEM micrographs were obtained from fractured surfaces after flexural and compressive tests, focusing on the morphology and distribution of CNTs and GNPs, as well as their interactions with hydration products.

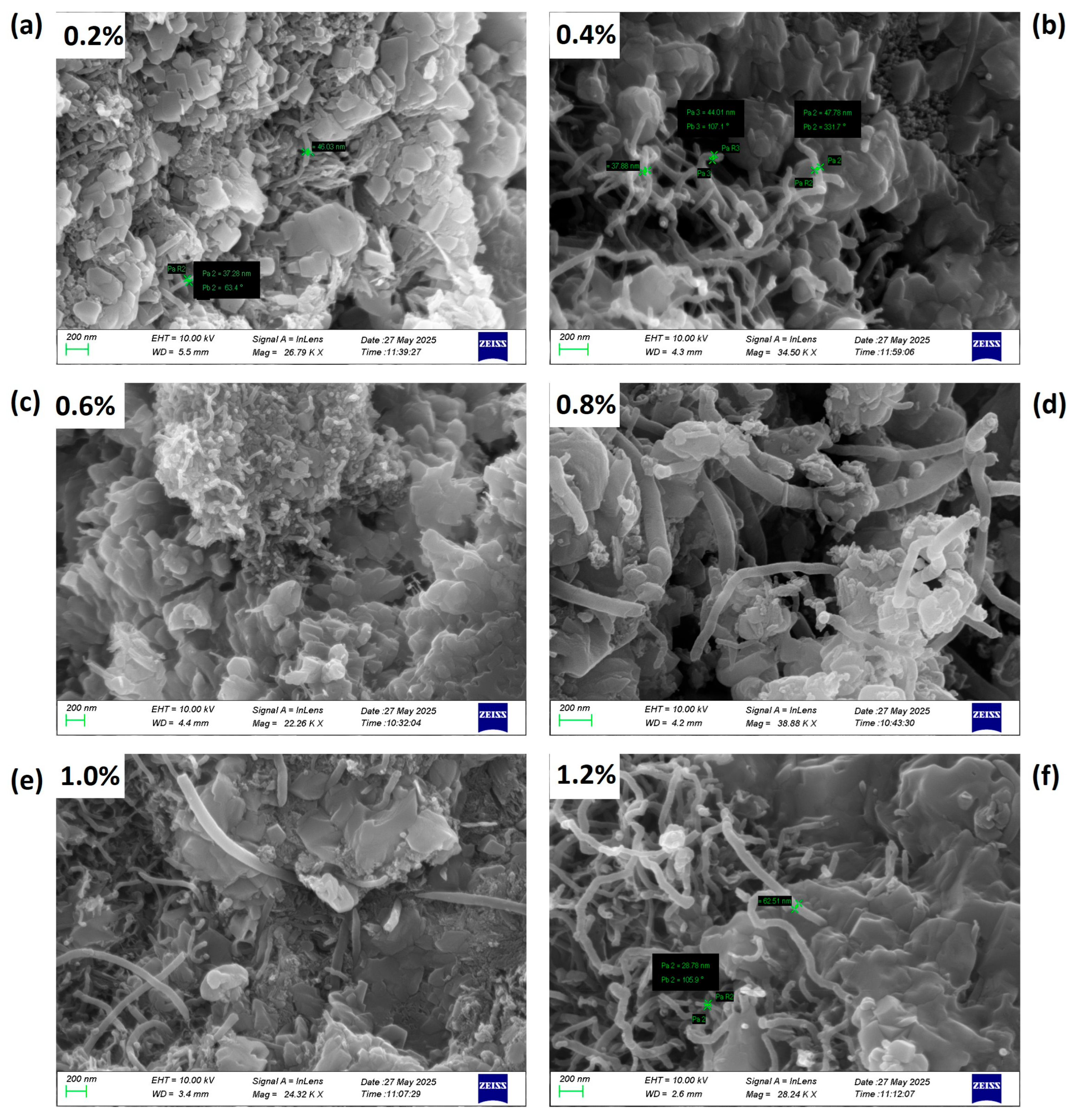

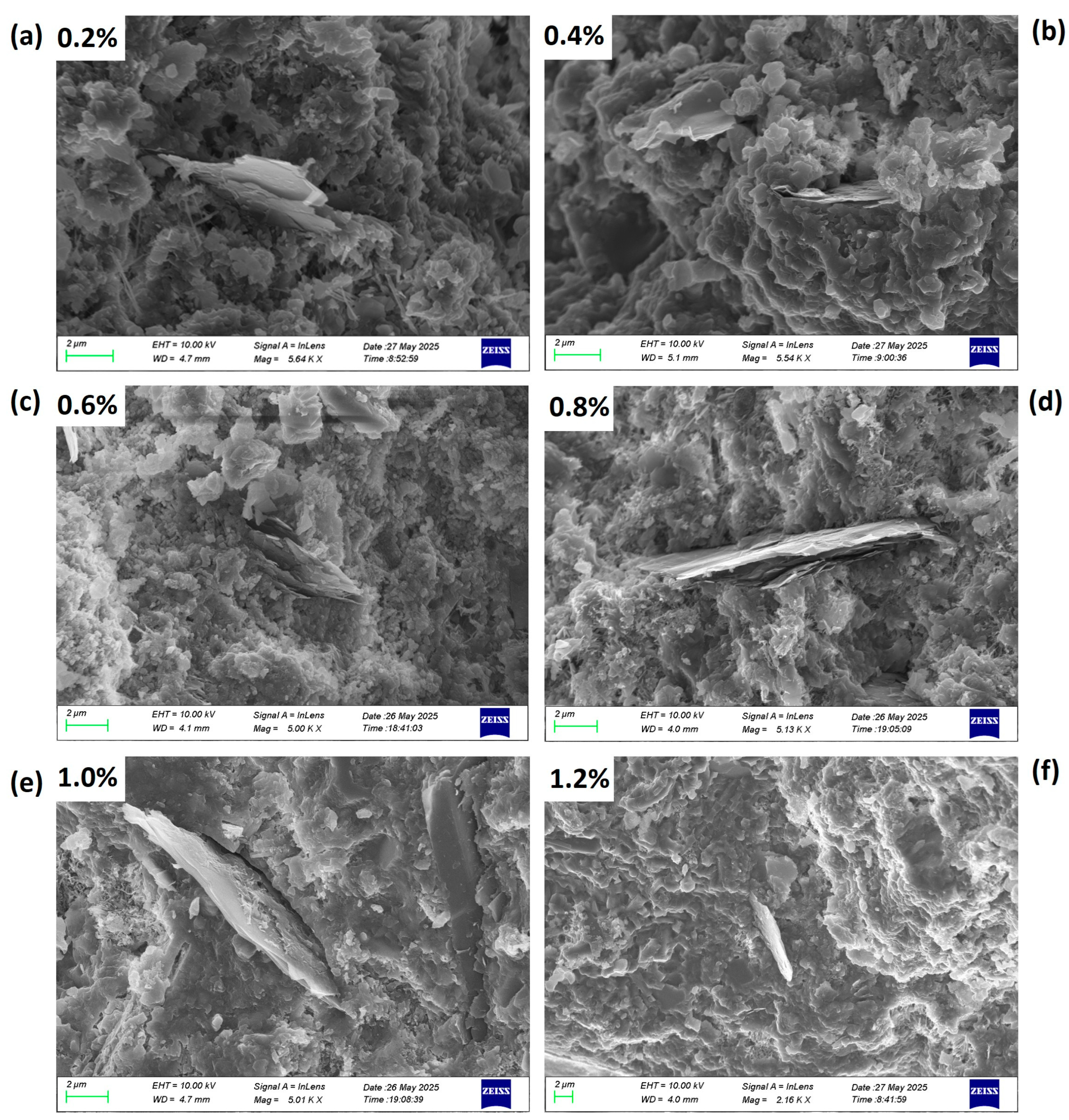

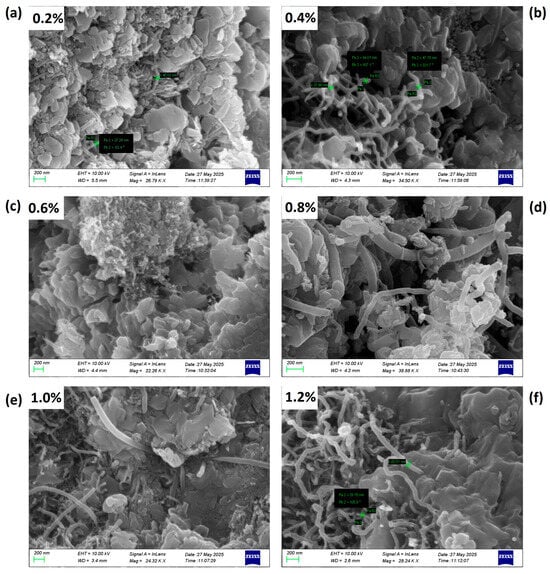

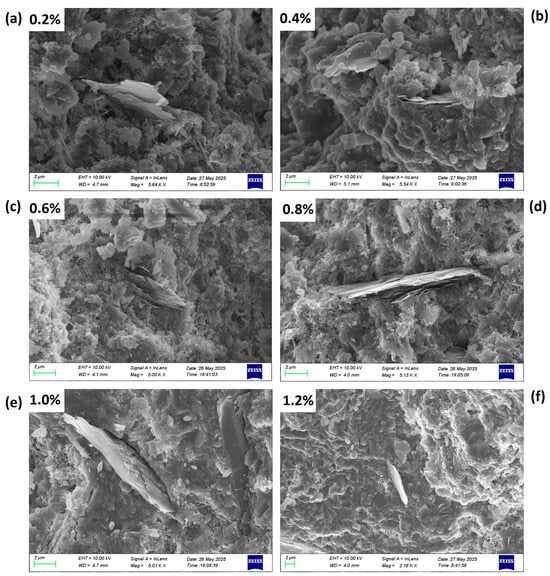

The examination provides insight into how different nanoscale reinforcement mechanisms, such as crack bridging, void filling, and interfacial bonding, contribute to overall mechanical enhancement at varying nano-reinforcement contents. Figure 6a–f correspond to CNT-modified specimens, while Figure 7a–f show the results of GNP-modified specimens.

Figure 6.

SEM micrographs of CNT-modified concrete at different CNT contents: (a) 0.2 wt.%, (b) 0.4 wt.%, (c) 0.6 wt.%, (d) 0.8 wt.%, (e) 1.0 wt.%, (f) 1.2 wt.%.

Figure 7.

SEM micrographs of GNP-modified concrete at different GNP contents: (a) 0.2 wt.%, (b) 0.4 wt.%, (c) 0.6 wt.%, (d) 0.8 wt.%, (e) 1.0 wt.%, (f) 1.2 wt.%.

SEM observations on the CNT-modified concrete specimens, as shown in Figure 6, illustrate the evolution of the microstructure with increasing CNT content. At low concentrations (0.2–0.4 wt.%), the cementitious matrix appears dense and homogeneous, with CNTs well dispersed and effectively embedded within the C–S–H phases. Moreover, individual nanotubes can be clearly seen bridging hydration products and filling nanoscale voids, indicating strong interfacial bonding and efficient load transfer. At 0.6 wt.% CNTs, the microstructure exhibits optimal compactness, with well-developed hydration products and minimal porosity, consistent with the highest mechanical performance observed experimentally. With increasing CNT content beyond 0.8 wt.%, signs of agglomeration become apparent. Clusters of entangled CNTs are observed, accompanied by poorly hydrated zones and microvoids that disrupt matrix continuity and serve as stress-concentration sites. At the highest dosage (1.2 wt.%), severe nanotube bundling and heterogeneous morphology are evident, resulting from excessive CNT addition that impairs dispersion efficiency and hinders hydration. Overall, microstructural analysis indicates that moderate CNT incorporation promotes matrix densification and crack-bridging mechanisms, whereas higher loadings lead to agglomeration and reduced mechanical efficiency.

Figure 7 presents SEM observations of GNP-modified concrete specimens, showing the evolution of the microstructure in the cementitious matrix with increasing graphene nanoplatelet content. At lower concentrations (0.2–0.4 wt.%), GNPs are uniformly distributed within the matrix and appear well incorporated into the hydration products, resulting in a dense, compact microstructure. The platelets are effectively embedded within the calcium–silicate–hydrate phases, demonstrating strong interfacial bonding and enhanced stress transfer, which account for the corresponding improvements in flexural and compressive performance. At intermediate dosages (0.6–0.8 wt.%), the matrix still exhibits a compact morphology, although localized regions of GNP stacking and partial overlapping become visible, indicating the onset of agglomeration. Despite these accumulations, the matrix’s overall cohesion and structural integrity remain largely unaffected. When the GNP content exceeds 1.0 wt.%, noticeable agglomeration and poorly hydrated zones are observed. High micro-porosity is induced by the presence of large, multilayer platelet clusters and interfacial debonding, which decrease the mechanical and fracture properties by disrupting matrix continuity. In summary, SEM analysis confirms that moderate incorporation of GNPs—through effective interaction with hydration products—enhances microstructural refinement and densification, while excessive loading promotes platelet agglomeration, porosity, and deterioration of the overall mechanical performance.

It should be noted that, while dispersion quality was ensured through a previously validated sonication protocol and indirectly supported by mechanical repeatability and microstructural consistency, direct quantitative characterization of the aqueous nanomaterial dispersions was not performed within the present study and will be addressed in future work. The agreement between the mechanical trends and the corresponding microstructural observations further supports that the reported effects are reproducible and not solely attributable to experimental scatter.

4. Conclusions

The influence of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) on the mechanical and microstructural performance of concrete was investigated in this study. Based on the experimental results, supported by SEM observations, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- The incorporation of both CNTs and GNPs led to a significant enhancement in the flexural, compressive, and fracture performance of concrete compared with the reference mixture.

- Optimum enhancement was achieved at 0.6 wt.% CNTs and 0.8 wt.% GNPs, where flexural strength increased by approximately 49% and 38% (it should again be noted that similar performance can be observed at 0.4wt.% for GNPs), respectively, while compressive strength increased by 22% and 47%.

- SEM analysis revealed that at low and intermediate nanomaterial concentrations, both CNTs and GNPs were well dispersed within the cementitious matrix, promoting matrix densification, pore structure refinement, and stronger interfacial bonding with hydration products.

- Beyond the optimum nano-inclusion dosage, the formation of agglomerates and poorly hydrated zones became evident, leading to increased porosity and a degradation of mechanical performance.

- Between the two nanomaterials, CNTs achieved the highest flexural and fracture performance, while GNPs exhibited superior compressive strength. This difference arises from their distinct reinforcing mechanisms: CNTs, due to their one-dimensional tubular morphology and high aspect ratio, promote effective crack-bridging and stress transfer, enhancing tensile and flexural behavior, whereas GNPs, with their two-dimensional platelet structure and larger surface area, improve particle packing and matrix densification, resulting in higher compressive performance. Overall, both nanomaterials contribute to strengthening through complementary mechanisms within the cementitious matrix.

As with most experimental investigations on nanomodified cementitious materials, the present study is conducted under controlled laboratory conditions and within a defined experimental framework. Such conditions are necessary to ensure repeatability, isolate the effects of nanomaterial type and content, and enable meaningful comparison between CNT- and GNP-modified systems. The adopted mix design, dispersion protocol, and short-term mechanical evaluation, therefore, represent a reasonable and widely accepted experimental approach for elucidating reinforcing mechanisms and dosage-dependent trends. Within this framework, the conclusions drawn are valid for the investigated material systems and testing conditions. Based on the authors’ previous experimental studies on similar CNT- and GNP-modified cementitious systems, no adverse effects on long-term durability are expected at the investigated nanomaterial contents; nevertheless, extended durability assessment follows the standard progression of experimental research and constitutes a natural direction for future work.

Overall, the findings confirm that the controlled incorporation of carbon-based nanomaterials can effectively improve the mechanical efficiency and microstructural integrity of concrete if dispersion is adequate and an optimum amount is used. These insights may contribute to the development of next-generation high-performance and durable cementitious composites Given the limited number of specimens per condition (n = 3), the study emphasizes variability-aware interpretation and reproducibility of trends rather than formal hypothesis-testing claims.

Author Contributions

Preparation of specimens, S.G.F.; methodology, S.G.F., D.A.E. and T.E.M.; flexural strength measurements, S.G.F.; compressive strength measurements, A.G.; SEM, V.D.; data curation, S.G.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G.F.; writing—review and editing, S.G.F., A.G., D.A.E., K.G.D. and T.E.M.; visualization, S.G.F.; supervision, K.G.D. and T.E.M.; project administration, T.E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available upon request to the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Anastasios Gkotzamanis was employed by Geotest S.A. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Sanchez, F.; Sobolev, K. Nanotechnology in concrete—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2060–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsaei, E.; de Souza, F.B.; Yao, X.; Benhelal, E.; Akbari, A.; Duan, W. Graphene-based nanosheets for stronger and more durable concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 183, 642–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S.; Pan, Z.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Wang, C.M.; Duan, W.H. Nano reinforced cement and concrete composites and new perspective from graphene oxide. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 73, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sldozian, R.J.; Burakov, A.E.; Aljaboobi, D.Z.M.; Hamad, A.J.; Tkachev, A.G. The effect of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties and water adsorption of lightweight foamed concrete. Res. Eng. Struct. Mater. 2024, 10, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.Y.; Wan, Y.; Duan, Y.J.; Shi, Y.H.; Gu, C.P.; Ma, R.; Dong, J.J.; Cui, D. A review of the impact of graphene oxide on cement composites. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.M.; Lee, J.H. Electrical conductivity and compressive strength of cement paste with multiwalled carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, T.S.; Panesar, D.K. Nano reinforced cement paste composite with functionalized graphene and pristine graphene nanoplatelets. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 197, 108063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, L.; Buoso, A.; Corazza, F. Electrical properties of carbon nanotubes cement composites for monitoring stress conditions in concrete structures. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2011, 82, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, S.G.; Dalla, P.T.; Exarchos, D.A.; Dassios, K.G.; Matikas, T.E. Thermal and Electrical Properties of Cement-Based Materials Reinforced with Nano-Inclusions. Nanomanufacturing 2025, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makar, J.M.; Beaudoin, J.J. Carbon nanotubes and their application in the construction industry. In Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Nanotechnology in Construction, Scotland, UK, 23–25 June 2003; National Research Council Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2003; p. 341. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, R.; Mehta, A. Effect of carbon nanotubes on properties of cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 50, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, E.; Zhang, W.; Lai, J.; Hu, H.; Xue, F.; Su, X. Enhancement of Cement-Based Materials: Mechanisms, Impacts, and Applications of Carbon Nanotubes in Microstructural Modification. Buildings 2025, 15, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, K.; Loh, K.J. Nanoengineering ultra-high-performance concrete with multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2142, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestro, L.; Gleize, P.J.P. Effect of carbon nanotubes on compressive, flexural and tensile strengths of Portland cement-based materials: A systematic literature review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 264, 120237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, A.; Ram, M.K.; Zayed, A.; Kamal, R.; Shanahan, N. Investigation of physical properties of graphene-cement composite for structural applications. Open J. Compos. Mater. 2014, 4, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Shakouri, M.; Abraham, O.F. Assessing the Impact of Graphene Nanoplatelets Aggregates on the Performance Characteristics of Cement-Based Materials. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, L.J.; Kalfat, R. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties and Water Resistance Performance of Concrete Modified with Graphene Nanoplatelets (GNP). Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2025, 19, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilding, J.; Grulke, E.A.; George Zhang, Z.; Lockwood, F. Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in liquids. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2003, 24, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafogianni, P.; Dassios, K.; Farmaki, S.; Antiohos, S.; Matikas, T.; Barkoula, N.-M. On the efficiency of UV–vis spectroscopy in assessing the dispersion quality in sonicated aqueous suspensions of carbon nanotubes. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 495, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Fang, W.; Li, W.; Wang, P.; Khan, K.; Tang, Y.; Wang, T. Effects of multidimensional carbon-based nanomaterials on the low-carbon and high-performance cementitious composites: A critical review. Materials 2024, 17, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumari, B.Y.; Swaminathan, E.N.; Partheeban, P. A review on characteristics studies on carbon nanotubes-based cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla, P.T.; Tragazikis, I.K.; Trakakis, G.; Galiotis, C.; Dassios, K.G.; Matikas, T.E. Multifunctional Cement Mortars Enhanced with Graphene Nanoplatelets and Carbon Nanotubes. Sensors 2021, 21, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lee, J.C.; Moon, W.C.; Ng, J.L.; Yusof, Z.M.; Hong, X.; He, Q.; Li, B. Mechanical and microstructural improvements of high-strength lightweight concrete with carbon nanotubes and shale-based aggregates. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Fan, J.; Yi, B.; Ye, J.; Li, G. Effect of industrial multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the mechanical properties and microstructure of ultra-high performance concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 156, 105850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassios, K.G.; Alafogianni, P.; Antiohos, S.K.; Leptokaridis, C.; Barkoula, N.-M.; Matikas, T.E. Optimization of Sonication Parameters for Homogeneous Surfactant-Assisted Dispersion of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes in Aqueous Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 7506–7516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN 206:2013+A2:2021; Concrete—Specification, Performance, Production and Conformity. BSI Standards Limited: London, UK, 2021.

- ASTM C143/C143M-20; Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic-Cement Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM C231/C231M-17a; Standard Test Method for Air Content of Freshly Mixed Concrete by the Pressure Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM Standard C 1609/C 1609M-05; Standard Test Method for Flexural Performance of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (Using Beam With Third-Point Loading) (2006). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2005.

- ASTM Standard C 78-02; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Third-Point Loading) (2002). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2002.

- CEN. EN 12390-3:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- CEN. EN 12390-4:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 4: Strength Determination by Compressive Testing Machine Calibration and Verification. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, T.; Ling, Y.; Jiang, N.; Tawfek, A.M.; Yuan, H. Optimization of graphene nanoplatelets dispersion and its performance in cement mortars. Materials 2022, 15, 7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, V.V.; Ludvig, P.; Trindade, A.C.C.; de Andrade Silva, F. The influence of carbon nanotubes on the fracture energy, flexural and tensile behavior of cement based composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 209, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.