Abstract

Background: First-trimester prenatal screening is a fundamental component of modern obstetric care, offering early insights into fetal health and development. A key focus of this screening is the detection of chromosomal abnormalities, such as Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), which can have significant implications for pregnancy management and parental counseling. Over the years, various non-invasive methods have been developed, with ultrasound-based assessments becoming a cornerstone of early evaluation. Among these, the measurement of Nuchal Translucency (NT) has emerged as a critical marker. This sonographic measurement, typically performed between 11- and 13-weeks 6+ days of gestation, quantifies the fluid-filled space at the back of the fetal neck. An increased NT measurement is a well-established indicator of a higher risk for aneuploidies and other congenital conditions, including heart defects. The Fetal Medicine Foundation has established standardized criteria for this measurement to ensure its reliability and widespread adoption in clinical practice. Methods: We utilized two datasets comprising 2425 ultrasound images from Shenzhen People’s Hospital China and the National Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology Vietnam. The methodology employs a two-stage Deep Learning framework: first, a DenseNet121 model assesses image quality to filter non-standard planes; second, a novel DenseNet-based segmentation delineates the NT region for automated measurement. Results: The quality assessment module achieved 94% accuracy in distinguishing standard from non-standard planes. For segmentation, the proposed model achieved a Dice coefficient of 0.897 and an overall accuracy of 98.9%, outperforming the standard U-Net architecture. Clinically, 55.47% of automated measurements deviated by less than 1 mm from expert annotations, and the system demonstrated > 90% sensitivity and specificity for identifying high-risk cases (NT ≥ 2.5 mm). Conclusions: The proposed framework successfully integrates quality assurance with automated measurement, offering a robust decision-support tool to reduce variability and improve screening accuracy in prenatal care.

1. Introduction

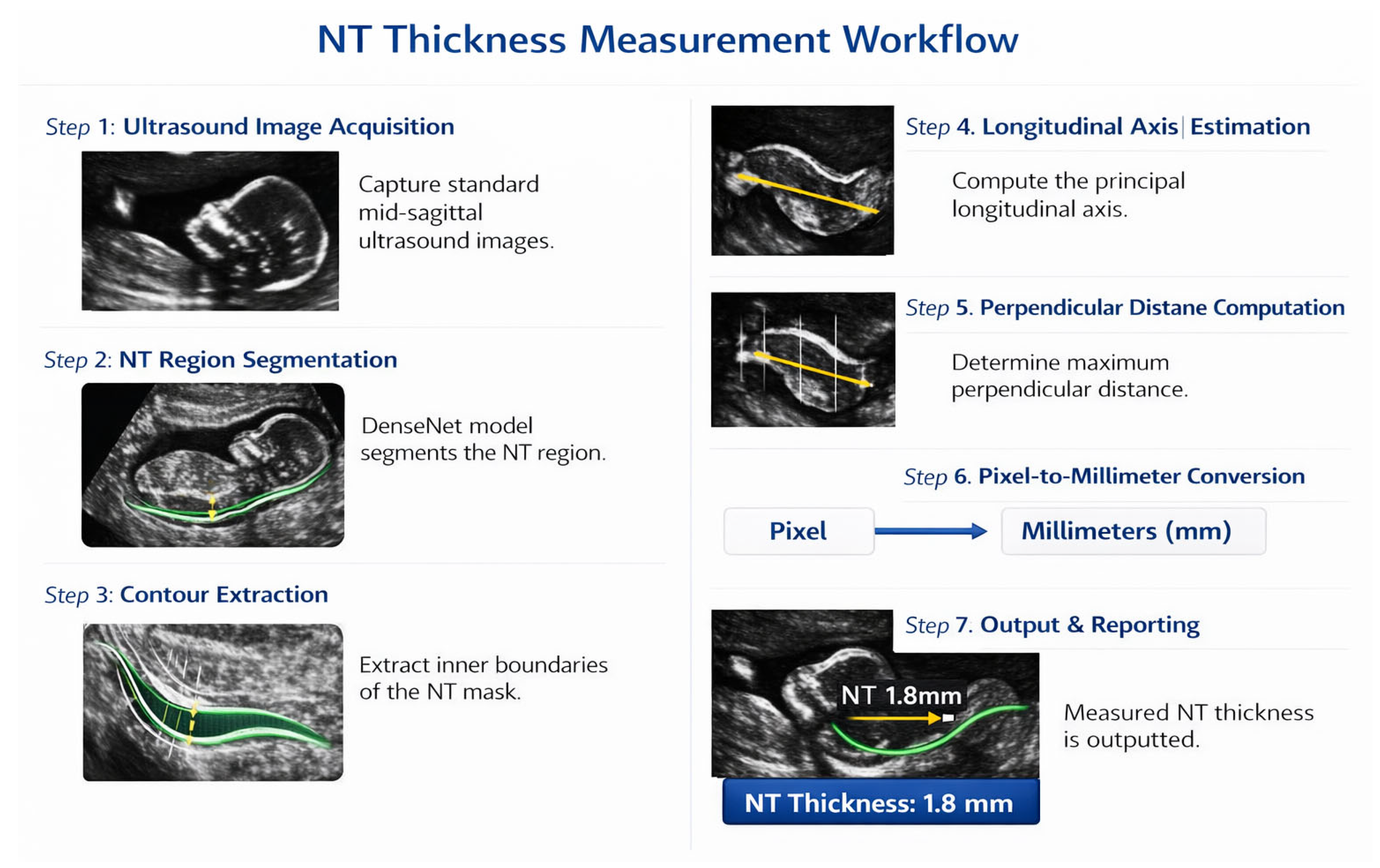

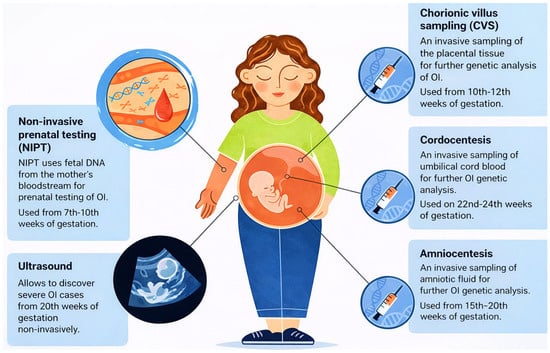

Prenatal screening is a multifaceted clinical process designed to monitor fetal development and detect potential genetic or structural abnormalities at various stages of gestation. As shown in Figure 1, several diagnostic and screening modalities are available throughout pregnancy, ranging from early non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) starting at 7 weeks, to invasive procedures like Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS) and Amniocentesis used for definitive genetic analysis [1].

Figure 1.

Overview of Prenatal Testing Options for Members of Families with OI Risk. NIPT—non-Invasive Prenatal Testing, Ultrasound, CVS—Chorionic Villus Sampling, Cordocentesis, Amniocentesis.

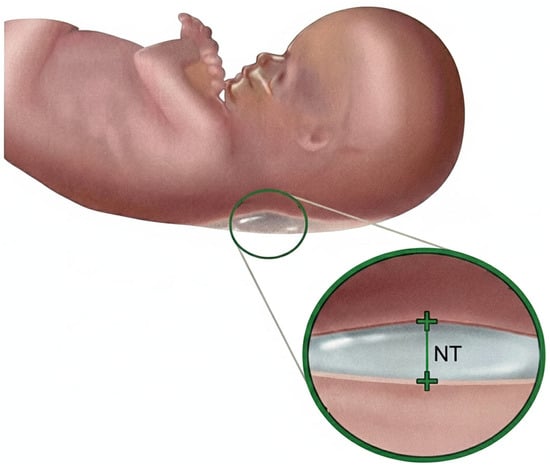

Nuchal Translucency (NT) screening, performed via ultrasound between 11 and 13 weeks + 6 days of gestation [2], is a cornerstone of first-trimester prenatal assessment and provides a critical, non-invasive marker for identifying fetuses at risk of chromosomal abnormalities, most notably Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) [3]. NT is defined as the maximum thickness of the transient, subcutaneous fluid collection at the back of the fetal neck, as illustrated in Figure 2, and increased NT width particularly above 3.5 mm is strongly associated with elevated risks of aneuploidies and congenital heart defects [4].

Figure 2.

Nuchal translucency.

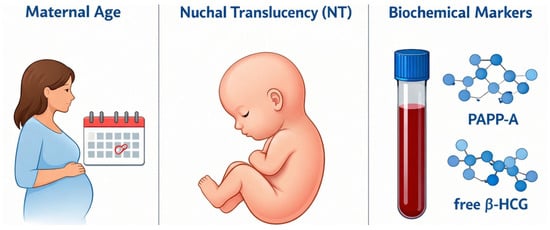

Accurate assessment requires obtaining the measurement in the strict mid-sagittal plane when the Crown–Rump Length (CRL) is between 45 mm and 84 mm, as the translucency naturally resolves after 14 weeks [5]. Screening performance improves substantially when NT is combined with maternal age and biochemical markers such as Pregnancy-Associated Plasma Protein-A (PAPP-A) and free beta–Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (free β-hCG) as illustrated in Figure 3, yielding detection rates of approximately 82–87% [6].

Figure 3.

Combined screening.

Despite its clinical value, the traditional manual technique for NT measurement requiring placement of calipers on the inner borders of the translucency remains highly operator-dependent and prone to substantial variability [7]. The reliability of NT screening is fundamentally challenged by the subjectivity of manual assessment, as accurate measurement demands strict adherence to sonographic standards such as appropriate magnification, a neutral fetal head position, and precise caliper placement [8,9]. Failure to consistently meet these criteria can introduce significant measurement error. Numerous studies [10], evaluating reproducibility have consistently reported both intra-operator and inter-operator inconsistencies, confirming that manual NT measurement lacks the uniformity required for optimal clinical decision-making [11].

In this paper, we propose an end-to-end, two-stage deep learning framework that explicitly integrates image quality assessment (IQA), precise NT segmentation, automated NT thickness measurement in millimeters, and final risk classification (Normal vs. High-Risk). Unlike prior works that either focus exclusively on standard/non-standard plane classification using the Fetus Framework dataset or limit their scope to NT measurement without upstream quality control, the proposed pipeline (i) combines a public dataset for robust image quality assessment with a clinical dataset for segmentation, measurement, and risk prediction; (ii) employs a DenseNet-based segmentation backbone tailored to the small, low-contrast NT region; and (iii) provides an interpretable geometric measurement procedure that converts pixel distances into clinically meaningful NT thickness values. This integrated design aims to more closely reflect the actual clinical workflow, reducing operator dependence and enabling scalable, reproducible screening during the 11 and 13 weeks + 6 days window recommended for NT assessment.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Manual Method for Measuring Nuchal Translucency

Manual measurement of NT remains the traditional clinical approach in first-trimester screening. The assessment is performed using two-dimensional ultrasound between 11 and 13 weeks + 6 days of gestation (crown–rump length: 45–84 mm) on a true mid-sagittal fetal plane with the fetus in a neutral position [12]. NT thickness is measured by placing calipers on the inner borders of the translucent region, ensuring clear separation between the fetal skin and the amniotic membrane [13]. Manual NT measurement is highly operator-dependent, with notable inter- and intra-observer variability [14]. Measurement accuracy is further affected by image quality limitations, including ultrasound noise, artifacts, and unfavorable fetal positioning, making the process subjective and error-prone [15,16].

2.2. Semi-Automated Methods for Measuring Nuchal Translucency

Semi-automated methods were introduced to reduce operator dependency and improve the reproducibility of manual NT measurements. Early work by Bernardino et al. required manual identification of NT boundaries, classifying the approach as semi-automatic due to user interaction in region selection [17].

Subsequent studies focused on integrating image filtering and optimization techniques to improve NT boundary detection. Lee et al. proposed a semi-automated method combining coherence-enhancing diffusion filtering and dynamic programming, achieving a high correlation (0.99) with manual measurements [18]. Similar dynamic programming–based approaches were later extended by Catanzariti et al. and Deng et al., incorporating gradient, continuity, and morphological constraints to improve boundary accuracy while still relying on manual ROI selection [19,20].

Machine learning-assisted semi-automated systems were also explored. Wee et al. employed a multilayer perceptron neural network for NT region detection, followed by automated thickness estimation, reporting a correlation of 0.98 with manual measurements [21]. Other studies investigated wavelet-based multi-resolution analysis [22] and Hessian-based filtering combined with learning models to enhance NT detection robustness [20].

To address variability and dimensional limitations, several works extended NT analysis beyond 2D. Nie et al. and Lai et al. demonstrated that 3D ultrasound-based NT measurement improves accuracy and reduces inter-operator variability compared to conventional 2D approaches [23,24].

Clinical validation studies confirmed the benefits of semi-automated methods. Abele et al., Moratalla et al., and Grangé et al. showed that semi-automated systems significantly reduce intra- and inter-observer variability, particularly for less experienced operators, achieving higher intraclass correlation coefficients than manual measurements [11,25,26]. However, these methods remain partially dependent on manual ROI placement and image acquisition quality, limiting full automation.

2.3. Machine Learning Methods for Measuring Nuchal Translucency

Machine learning (ML) methods have been increasingly applied to automate NT measurement and improve prenatal screening accuracy by reducing operator dependency. Early ML-based frameworks combined image preprocessing, feature extraction, and supervised classification to support NT-based diagnosis and fetal abnormality detection [27].

Several studies integrated NT with additional biometric and biochemical markers to enhance screening performance. Sun et al. proposed an ML-based nomogram combining NT and facial profile features, achieving high discrimination for trisomy 21 (AUC > 0.97), outperforming traditional NT-only screening [28]. Similarly, Ramanathan et al. applied classical ML classifiers to first-trimester screening data, reporting a maximum accuracy of 92.63% using Naïve Bayes [29].

To address data imbalance and feature correlation, Li et al. introduced a cascaded ML framework combining Isolation Forests and Logistic Regression, achieving an AUROC of 0.99 for Down syndrome prediction [30]. Other works explored ensemble learning, AdaBoost-based neural networks, and SVMs to improve NT-based classification accuracy and robustness [31,32].

Beyond classification, ML techniques were also used for fully automated NT detection and measurement [33]. Park et al. proposed an automatic NT measurement system integrating hierarchical detection networks, shortest-path optimization, and graph-cut segmentation, achieving a measurement error as low as 0.24 mm [34]. Spatial models combined with SVMs and HOG features further improved NT localization under noisy ultrasound conditions [35,36].

Recent studies demonstrated the effectiveness of unsupervised and hybrid ML approaches, including wavelet analysis with neural networks and feature-based regression models, achieving measurement errors below 0.3 mm and accuracies exceeding 97% [22,37,38]. These methods significantly improved consistency compared to manual and semi-automated techniques but remained sensitive to image quality and handcrafted feature design.

2.4. Deep Learning Methods for Measuring Nuchal Translucency

Quality assessment of NT ultrasound images is labor-intensive and time-consuming, which limits its feasibility in settings with constrained medical resources. Consequently, intelligent automation has become increasingly necessary. Advances in artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning, have enabled reliable automated NT image quality assessment, segmentation, and measurement with reduced operator dependency, while recent studies also emphasize end-to-end frameworks and model interpretability to ensure clinical reliability and practical deployment in obstetric ultrasound practice [39].

Several works focus on NT ultrasound image quality assessment, a critical prerequisite for reliable measurement. Liu et al. demonstrated that CNN- and Transformer-based models can accurately classify standard versus non-standard planes, with VGG16 achieving 98.1% accuracy and Grad-CAM confirming attention to clinically relevant regions [9]. Zhao et al. further improved robustness using a dual-stream contrastive framework Deep Content and Contrastive Perception (DCCP), achieving 99.3% accuracy by jointly modeling global context and local anatomical structures [40].

Beyond quality assessment, DL methods increasingly address automatic NT detection, segmentation, and measurement. U-Net-based architectures remain the most widely adopted, achieving Dice scores up to 0.94 for NT segmentation and measurement errors below 0.3 mm [41,42,43]. Hybrid pipelines combining object detection (e.g., YOLO), segmentation, and regression enable real-time and fully automated NT thickness estimation, with reported errors as low as 0.15 mm [44]. Attention-enhanced and context-aware networks further improve robustness against speckle noise, weak boundaries, and fetal pose variability [38,45,46].

DL has also been successfully applied to chromosomal abnormality and Down syndrome (DS) prediction, leveraging NT alongside complementary anatomical markers. CNN-based models trained on sagittal fetal images achieved AUC values up to 0.98 for trisomy 21 screening, outperforming traditional NT- and age-based approaches [21,47]. Dense connectivity, transfer learning, and ensemble strategies consistently improve classification accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, often exceeding 98% [48,49].

Recent trends highlight the integration of interpretability tools (e.g., Grad-CAM, saliency maps), graph-based reasoning, and multi-task learning to align model predictions with clinical knowledge and reduce diagnostic uncertainty [50]. Despite their strong performance, many DL studies remain constrained by limited dataset sizes, variability in acquisition protocols, and the lack of standardized evaluation benchmarks. Table 1 provides summary of the related works in the literature review.

Table 1.

Summary of the related works.

3. Materials and Methods

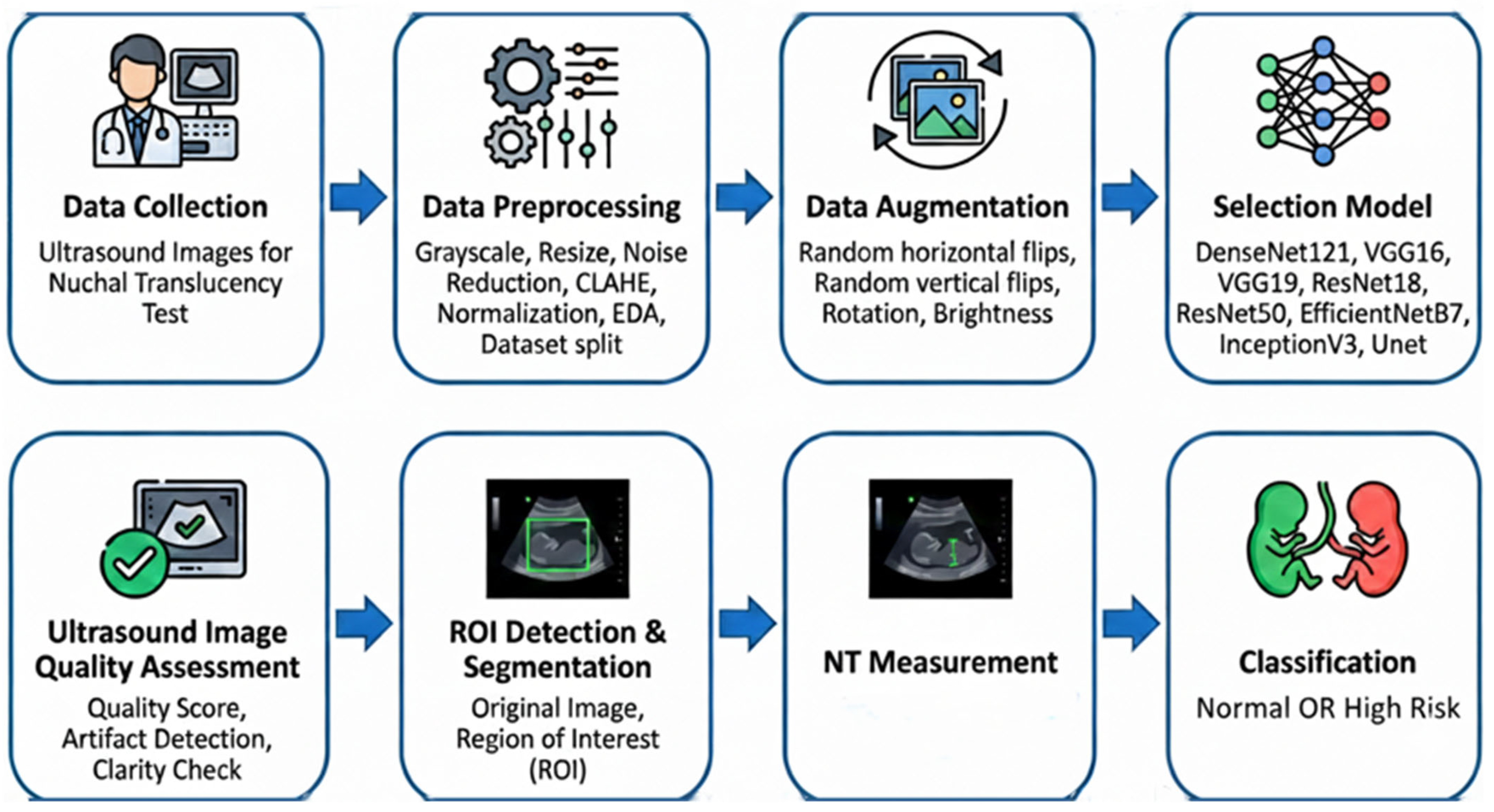

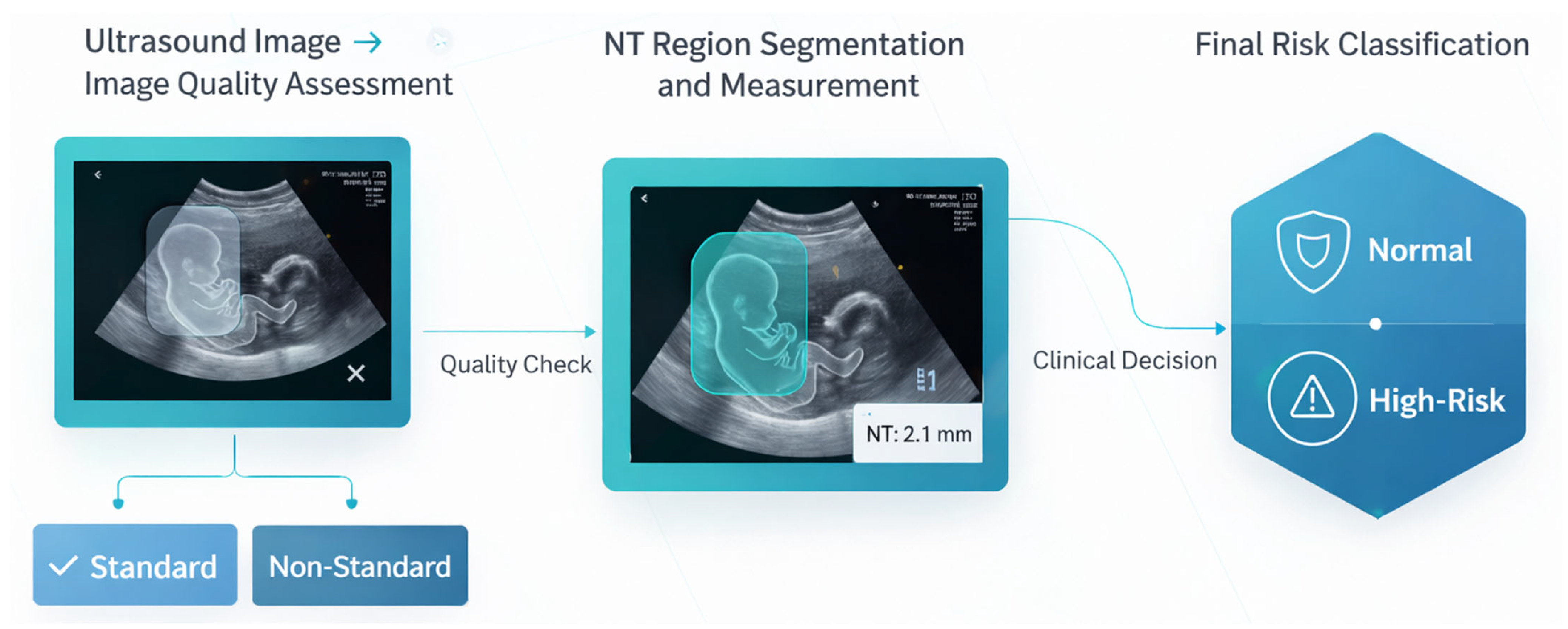

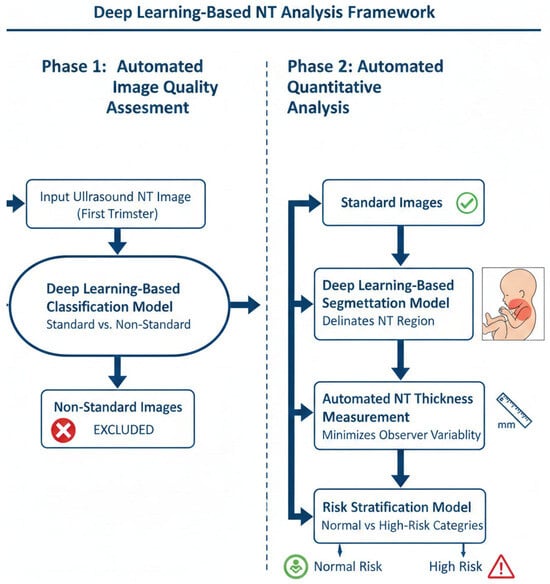

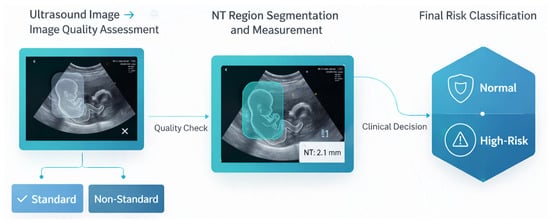

The proposed methodology comprises a two-phase automated workflow for the analysis of first-trimester NT ultrasound images, as depicted in Figure 4. The workflow is designed to first ensure image quality and then perform quantitative analysis, thereby ensuring both clinical validity and analytical accuracy.

Figure 4.

Two-phase workflow for automated NT screening.

- Phase 1: Automated Image Quality Assessment (IQA)

The initial phase consists of an automated IQA to classify first-trimester ultrasound images as either “standard plane” or “non-standard plane”. This classification is based on established sonographic criteria for obtaining a true mid-sagittal plane of the fetus.

A deep learning-based classification model was developed to perform this assessment. The model evaluates each input image for key quality indicators, including:

- Correct mid-sagittal alignment of the fetal head and thorax.

- A neutral fetal position (i.e., head in line with the spine, not hyperextended or flexed).

- Clear visualization of essential anatomical landmarks, such as the nasal bone and diencephalon [51].

Images that meet these criteria are classified as “standard plane” and proceed to the next phase. Images failing to meet the criteria are classified as “non-standard plane” and are excluded from further analysis. This quality-gating process serves as a critical control step to prevent measurement bias and error propagation, in alignment with international guidelines for reliable NT screening.

- Phase 2: Automated Segmentation, Measurement, and Risk Classification

This phase focuses on the quantitative analysis of the quality-approved “standard plane” images through a sequential pipeline.

- NT Region Segmentation: A deep learning-based segmentation model was employed to automatically delineate the precise boundaries of the NT region in the posterior fetal neck. This step isolates the subcutaneous, fluid-filled space required for measurement.

- Automated NT Measurement: Using the segmentation map generated in the previous step, the maximum vertical thickness of the NT is calculated algorithmically. This automated computation is designed to be deterministic and reproducible, thereby minimizing the inter- and intra-observer variability inherent in manual caliper placement.

- Risk Stratification: The calculated NT measurement is then fed into a final classification model. This model stratifies each case into one of two categories: “Normal” or “High Risk” for chromosomal abnormalities. This provides an objective, data-driven assessment to support clinical decision-making.

This integrated, end-to-end framework provides a reproducible and objective tool for NT analysis, leveraging deep learning to standardize a critical component of first-trimester prenatal screening.

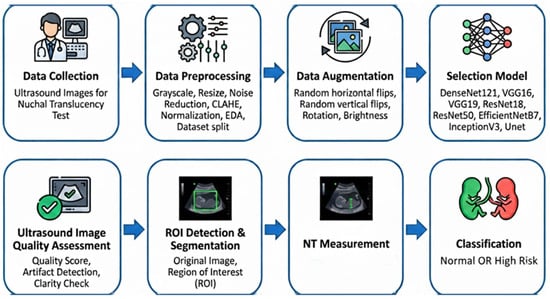

The proposed diagnostic pipeline, illustrated in Figure 5, follows a systematic approach for the automated analysis of NT. The process begins with data collection and preprocessing, utilizing CLAHE and normalization to enhance ultrasound image quality. After data augmentation, various deep learning architectures including EfficientNetB7 and UNet are evaluated for feature extraction. The final stages involve automated quality assessment, ROI segmentation, and NT measurement, ultimately facilitating the binary classification of fetal scans into “Normal” or “High Risk” categories.

Figure 5.

Overview of proposed pipeline.

3.1. Data Collection and Data Description

The development of robust deep learning models for automated NT analysis fundamentally relies on high-quality, clinically representative ultrasound data. This study employed two complementary datasets, each aligned with a distinct stage of the proposed multi-stage pipeline. The first dataset, the publicly accessible Fetus Framework collection [52], was used exclusively for NT image-quality assessment. The second dataset firsthand. It is provided by the National Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology (NHOG) in Hanoi, Vietnam. The second dataset supported all downstream tasks including NT region segmentation, automated measurement, and risk stratification.

3.1.1. First Dataset Fetus Framework

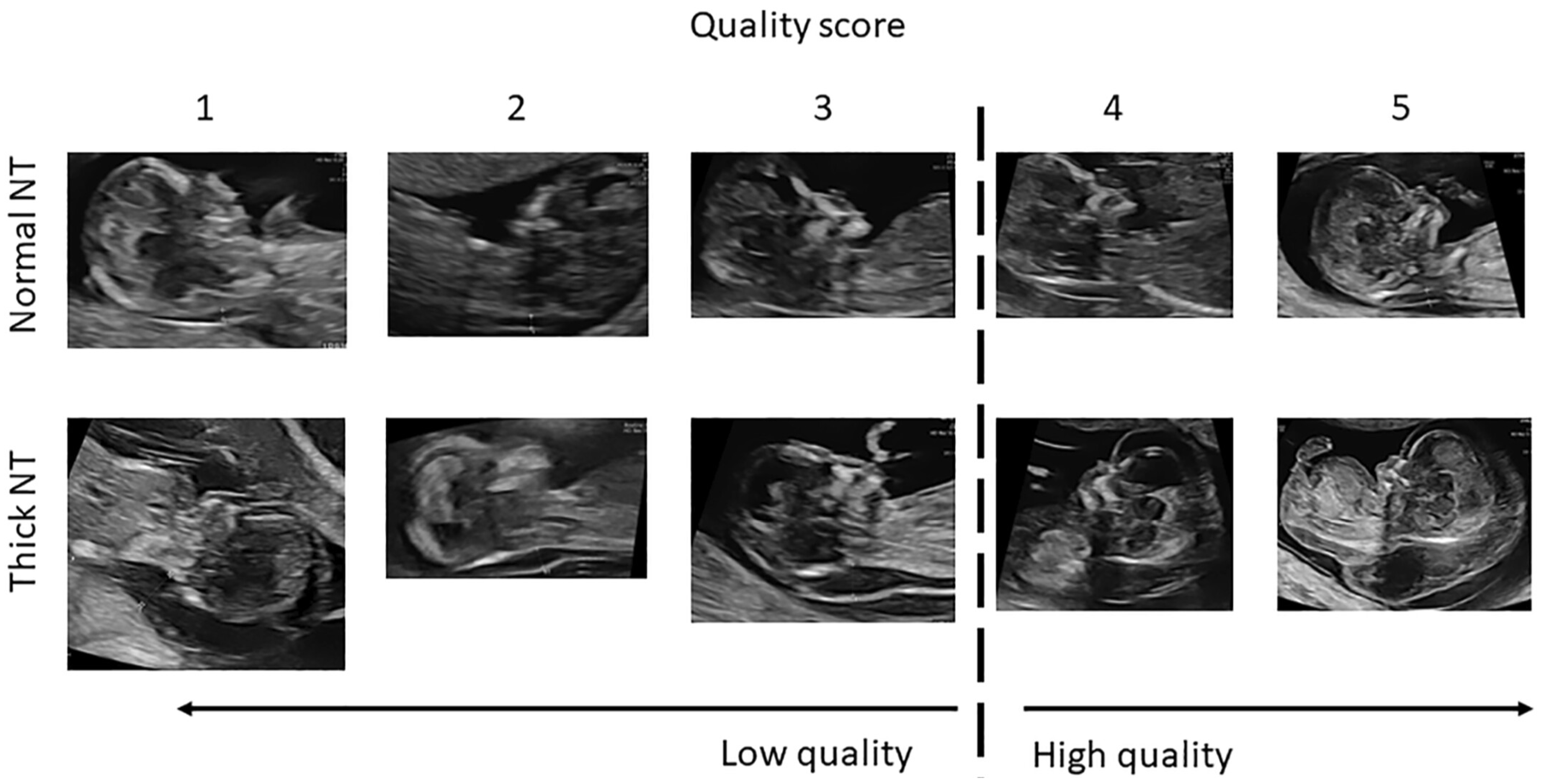

The Dataset for Fetus Framework [52] was utilized in the initial stage of the pipeline, where the objective was to classify ultrasound images into Standard and Non-Standard planes, as illustrated in Figure 6. The dataset, sourced from the Mendeley Data repository, consists of 1684 two-dimensional sagittal fetal ultrasound images collected during routine first-trimester examinations (11–13 week + 6 days gestational age) at Shenzhen People’s Hospital, China.

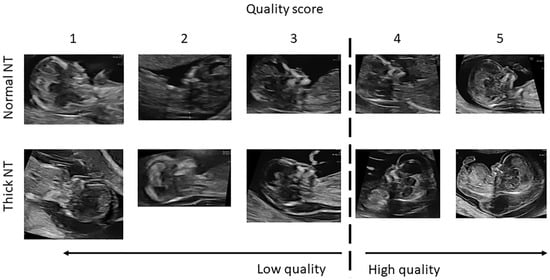

Figure 6.

Ultrasound image quality assessment for NT evaluation. The image quality is graded on a 5-point scale (1–5), where 1 indicates very low image quality, 3 represents acceptable diagnostic quality, and 5 indicates optimal image quality with clear visualization of fetal anatomical landmarks required for accurate NT measurement. The dashed vertical line separates low-quality (scores 1–2) from high-quality images (scores 3–5).

Key characteristics include:

- Binary quality labels: Each image is annotated as Standard or Non-Standard planes based on adherence to NT acquisition guidelines, including mid-sagittal plane visibility, correct fetal posture, and CRL range.

- Expert-validated annotations: Labeling was performed by experienced clinicians, ensuring high diagnostic reliability.

- Clinical realism: Images were captured under typical clinical conditions, increasing the external validity and generalizability of the classification models. Table 2 summarizes the dataset’s class distribution.

Table 2. Class distribution of the fetus framework dataset.

Table 2. Class distribution of the fetus framework dataset.

3.1.2. Second NHOG Dataset

The second dataset comprises 741 sagittal fetal ultrasound images collected at the National Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology (NHOG), Hanoi. This dataset formed the foundation for all diagnostic stages beyond image-quality assessment, including:

- Detection and segmentation of the NT Region of Interest (ROI);

- Automated NT thickness measurement in millimeters;

- Clinical risk classification into Normal versus High-Risk.

Key characteristics include:

- Pixel-level segmentations: Most images contain expert-drawn polygonal segmentation masks of the NT region, enabling high-precision supervised learning.

- Measurement-ready metadata: Verified NT thickness, gestational age, and CRL values are available for the majority of cases, supporting quantitative evaluation.

- Operational clinical variability: Images exhibit natural variations in fetal orientation, probe angle, and soft-tissue contrast—conditions essential for developing models that generalize to real clinical settings. Table 3 summarizes the dataset’s class distribution.

Table 3. NHOG dataset labeled availability.

Table 3. NHOG dataset labeled availability.

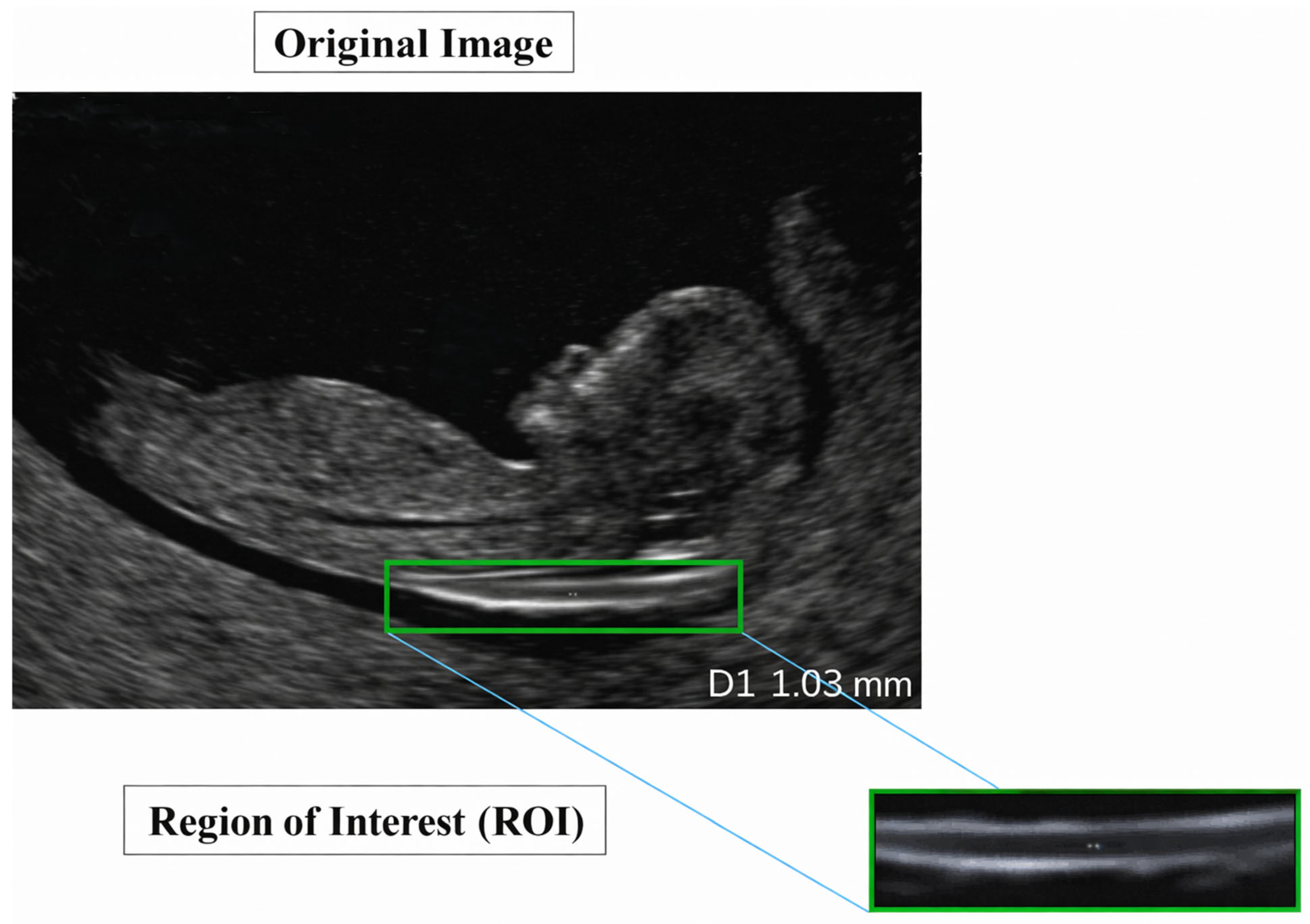

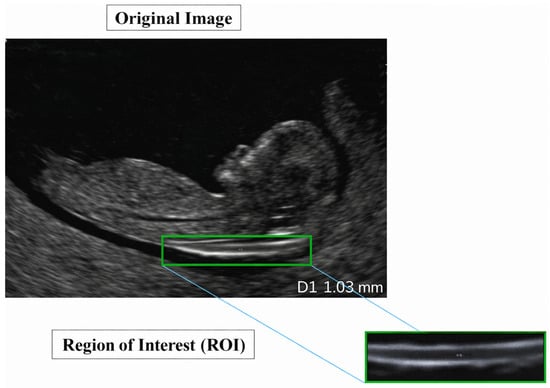

A representative example of a standard-view image from the NHOG dataset is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Sample image from the NHOG fetal ultrasound dataset.

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

Ultrasound imaging presents inherent challenges including speckle noise, low soft-tissue contrast, and significant variability in acquisition quality, which necessitate a carefully engineered preprocessing pipeline. In this study, preprocessing was tailored to the characteristics and downstream tasks of each dataset, followed by task-specific data augmentation designed to improve generalization and address class imbalance.

3.2.1. Preprocessing for First Dataset Fetus Framework

For the image-quality assessment stage, the Fetus Framework dataset underwent a standardized preprocessing pipeline:

- Denoising: A BM3D-based denoising filter (σ = 10) was applied to reduce speckle and random noise while preserving fine structural edges critical for distinguishing Standard from Non-Standard NT planes. BM3D (Block-Matching and 3D filtering) [53] remains one of the highest-performing denoisers for medical images due to its collaborative transform-domain filtering.

- Resizing and Normalization: All images were resized to 224 × 224 pixels and normalized to ensure compatibility with widely used classification architectures and pre-trained CNN backbones.

- Dataset partitioning: The dataset was split into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) subsets using stratified sampling to preserve the class distribution and prevent sampling bias.

3.2.2. Augmentation for First Dataset Fetus Framework

To counter class imbalance and increase the diversity of imaging conditions within the training distribution, multiple augmentation strategies were applied:

- Horizontal flips and 90° rotational transformations to simulate probe rotation and fetal orientation changes.

- Additive Gaussian noise and Gaussian smoothing to replicate realistic variations in acquisition noise.

- Contrast adjustments to model differences in ultrasound machine settings and operator techniques.

3.2.3. Preprocessing for Second NHOG Dataset

The NHOG dataset, used for segmentation, NT measurement, and risk classification, required a more specialized pipeline:

- Mask Generation: COCO (Common Objects in Context)-formatted polygon annotations were converted into binary segmentation masks, producing precisely aligned image–mask pairs for supervised training.

- Resizing and Normalization: All images and masks were resized to 256 × 256 pixels, and pixel intensities were normalized to stabilize gradient behavior across different ultrasound contrasts.

- Speckle Reduction: Speckle-Reducing Anisotropic Diffusion (SRAD) was applied to attenuate multiplicative speckle noise while maintaining anatomical boundaries essential for accurate NT segmentation [54].

- Local Contrast Enhancement Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) was used to enhance the local contrast around the NT region, improving separability between the translucent space and adjacent soft tissues without over-amplifying noise [55].

3.2.4. Augmentation for Second NHOG Dataset

To improve the robustness of segmentation and measurement models under varied clinical conditions, the NHOG training data underwent targeted augmentations:

- Rotational augmentation between −90° and +90° to reflect fetal position variability.

- Horizontal and vertical flips to simulate transducer orientation changes.

- Scaling, zooming, and intensity-based augmentations (brightness and contrast shifts) to reproduce differences in acquisition settings and tissue echogenicity.

These augmentations expanded the effective training set from 741 to 952 samples (+28.5%), contributing to improved generalization across real-world ultrasound appearances.

3.3. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) was conducted to characterize the datasets, verify data integrity, and ensure clinical plausibility of the extracted parameters prior to model development [56].

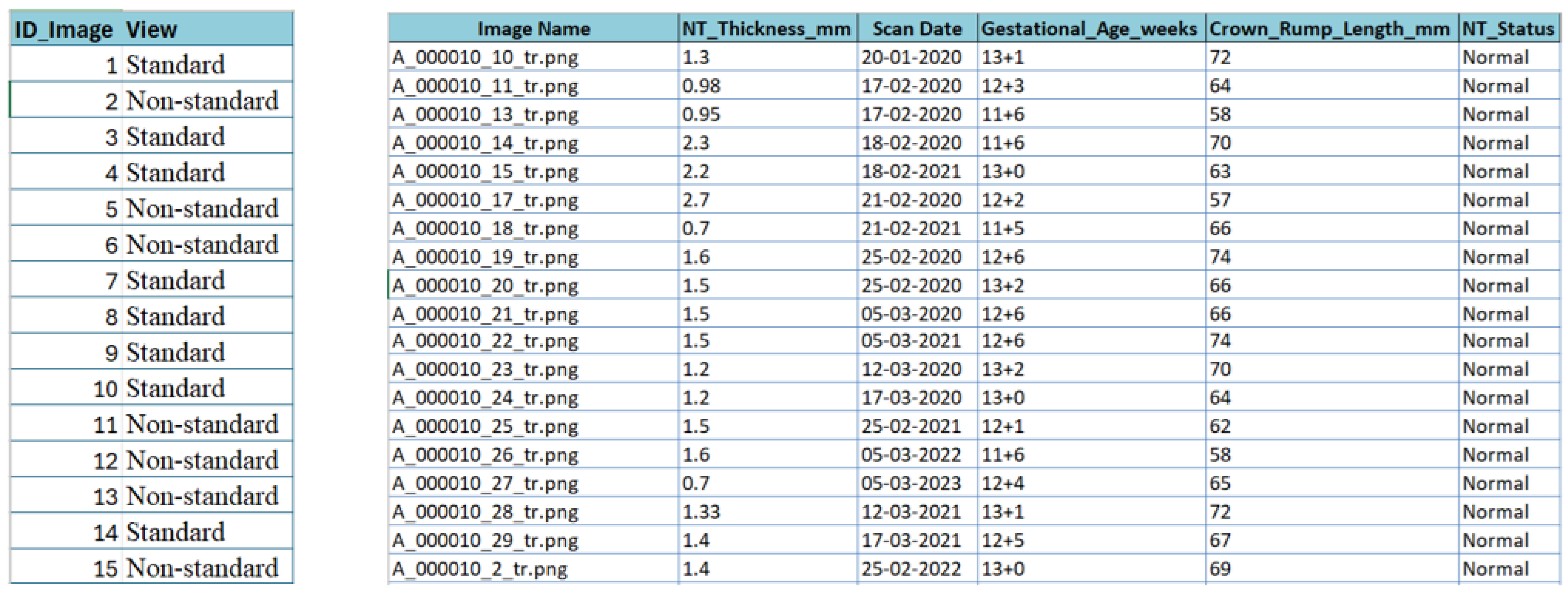

3.3.1. Metadata Extraction and Feature Definition

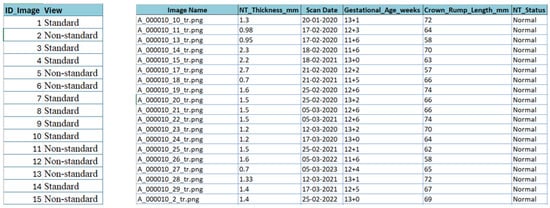

For the NHOG Vietnam dataset, metadata extraction was essential due to the absence of structured clinical descriptors. As shown in Figure 8, an automated workflow combining Python 3.13.5 scripting, OpenCV-based image parsing, and Tesseract OCR (Optical Character Recognition) [57] was implemented to retrieve clinically relevant variables directly from the ultrasound images, including NT thickness (mm), gestational age (weeks), Crown–Rump Length (CRL, mm), and NT status (Normal vs. Increased). All extracted values were carefully validated, cleaned, and harmonized to correct OCR errors and remove inconsistencies caused by image artifacts, resulting in a consolidated metadata sheet for downstream analysis.

Figure 8.

Snapshot from the metadata sheet for the fetus framework dataset and NHOG Vietnam datasets.

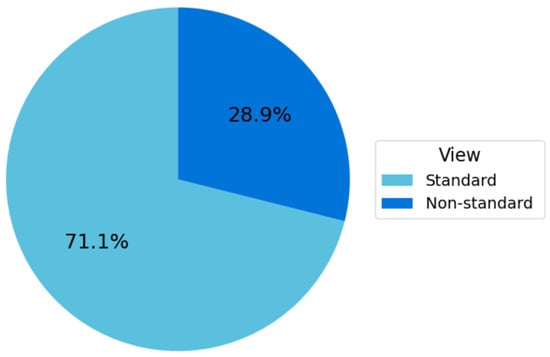

3.3.2. First Dataset Fetus Framework Distribution

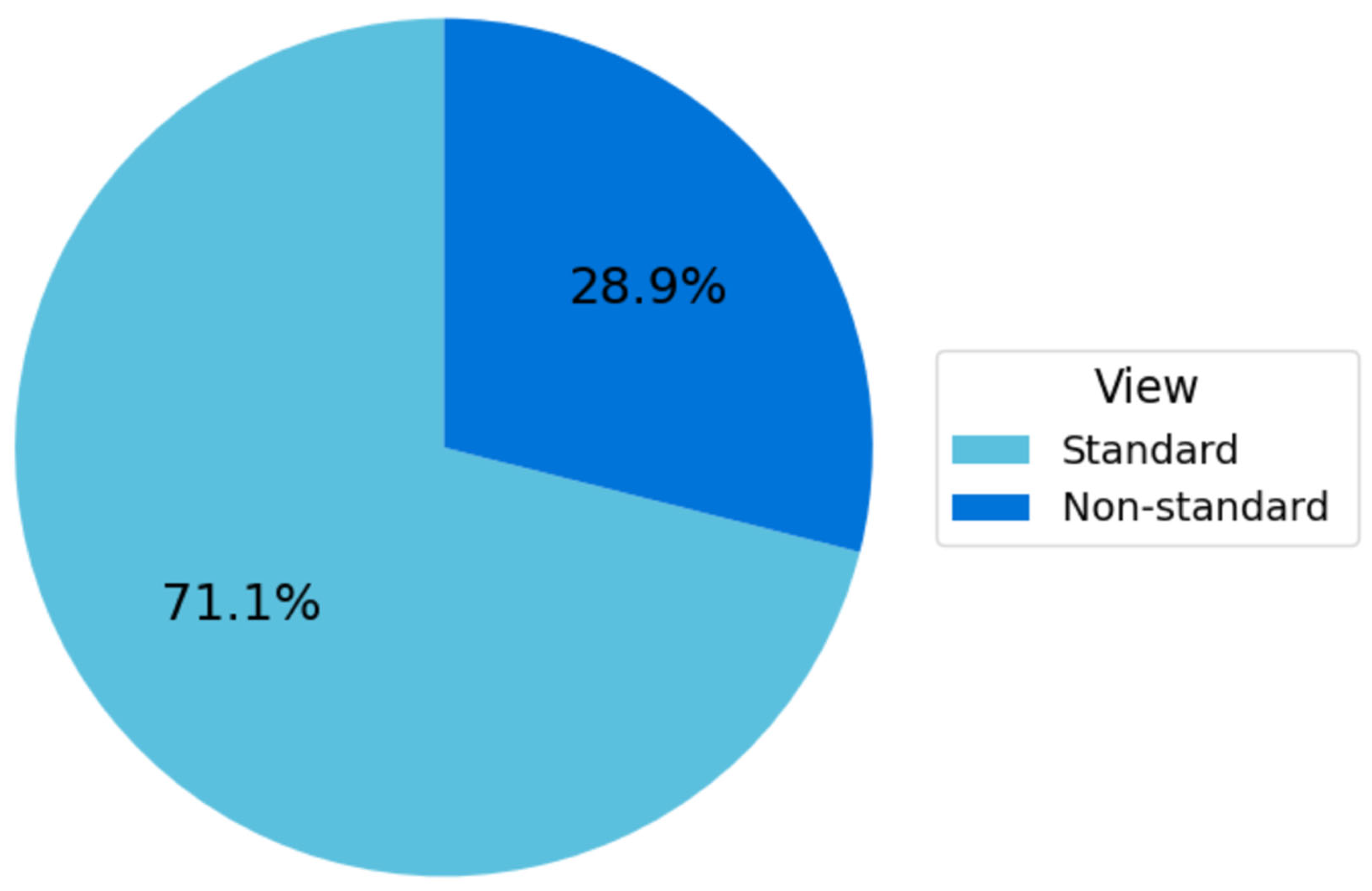

The Fetus Framework dataset comprised 1684 ultrasound images labeled according to NT image-quality criteria, as summarized in Figure 9. Among these, 1197 images (71.1%) were classified as Standard plane and 487 images (28.9%) as Non-Standard plane. This distribution reflects the higher availability of clinically interpretable NT planes in routine first-trimester screening and provides a robust foundation for developing and validating the image-quality assessment models.

Figure 9.

Distribution of standard vs. non-standard planes in the fetus framework dataset.

3.3.3. Second NHOG Dataset Distribution

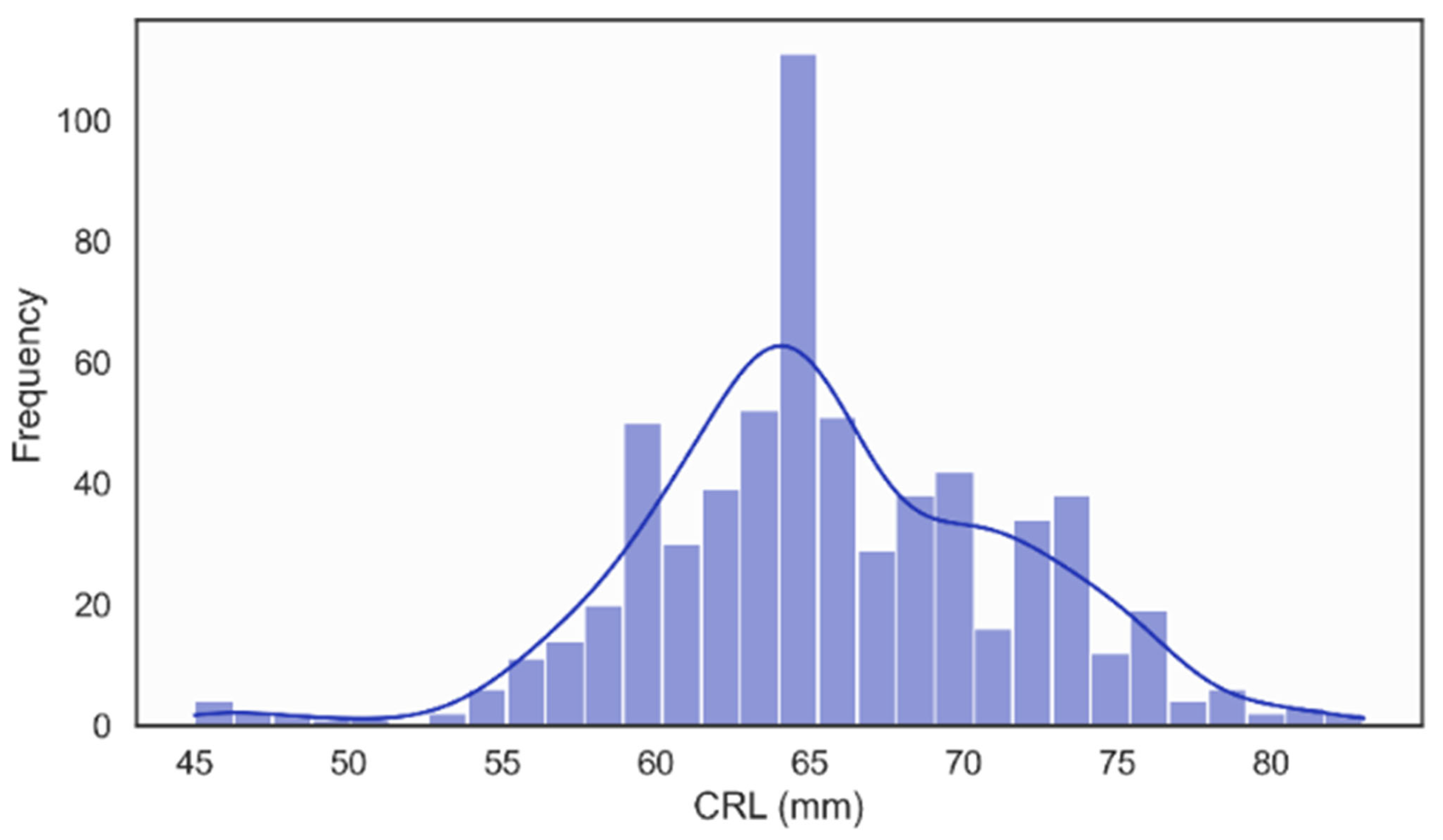

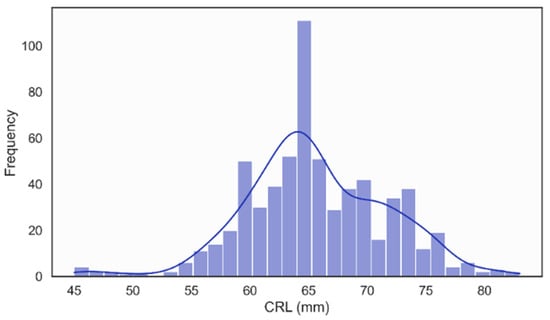

In the NHOG Vietnam dataset, the distribution of Crown–Rump Length (CRL) was unimodal and approximately Gaussian, with most values clustered around 60–70 mm, as illustrated in Figure 10. This pattern is consistent with the expected CRL range for fetuses examined during the recommended 11–13 + 6 weeks [58], window for NT screening, confirming that the dataset adequately represents early fetal development within the clinically relevant gestational period.

Figure 10.

Distribution of Crown Rump Length (CRL).

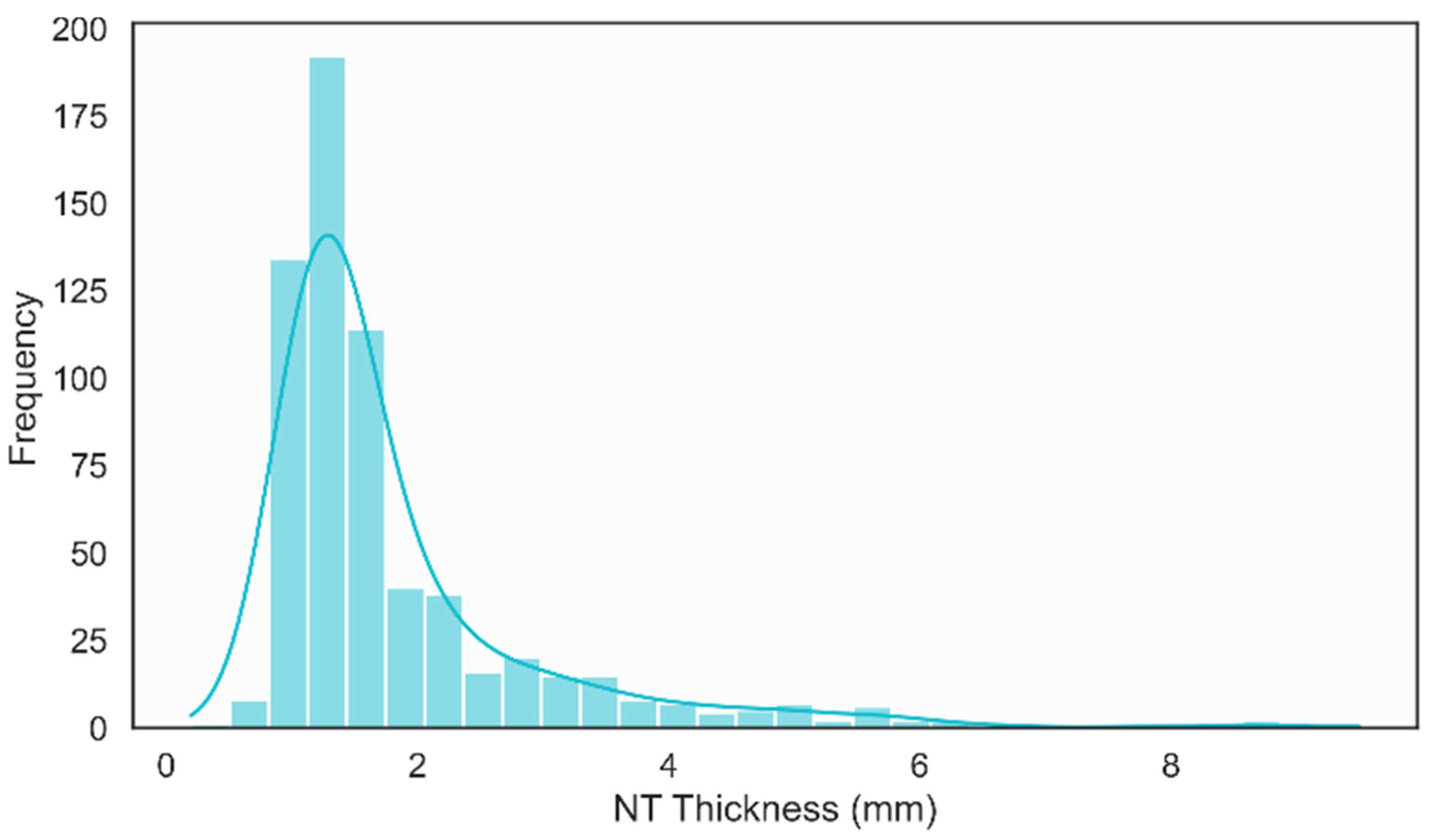

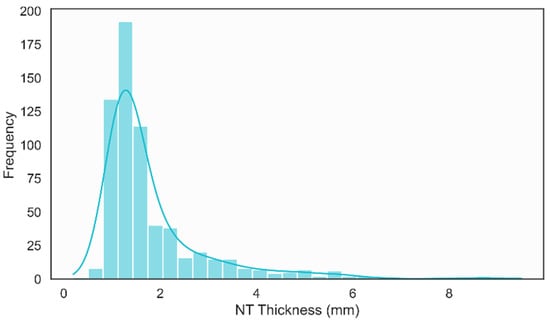

The histogram of NT thickness revealed a clearly right-skewed distribution, with the majority of measurements concentrated between 1.0 mm and 2.0 mm and a smaller tail extending beyond 3.0 mm, as shown in Figure 10. This distribution reflects the predominance of normal NT values while still capturing a meaningful subset of increased measurements, which is essential for training and evaluating models aimed at distinguishing normal and high-risk cases in a clinically realistic setting.

Figure 11 presents a histogram illustrating the distribution of NT thickness. The distribution is right-skewed, with the majority of NT measurements concentrated between 1.0 mm and 2.0 mm. The peak frequency occurs near 1.2 mm, aligning with both the mode and median reported in the descriptive statistics.

Figure 11.

Distribution of NT Thickness.

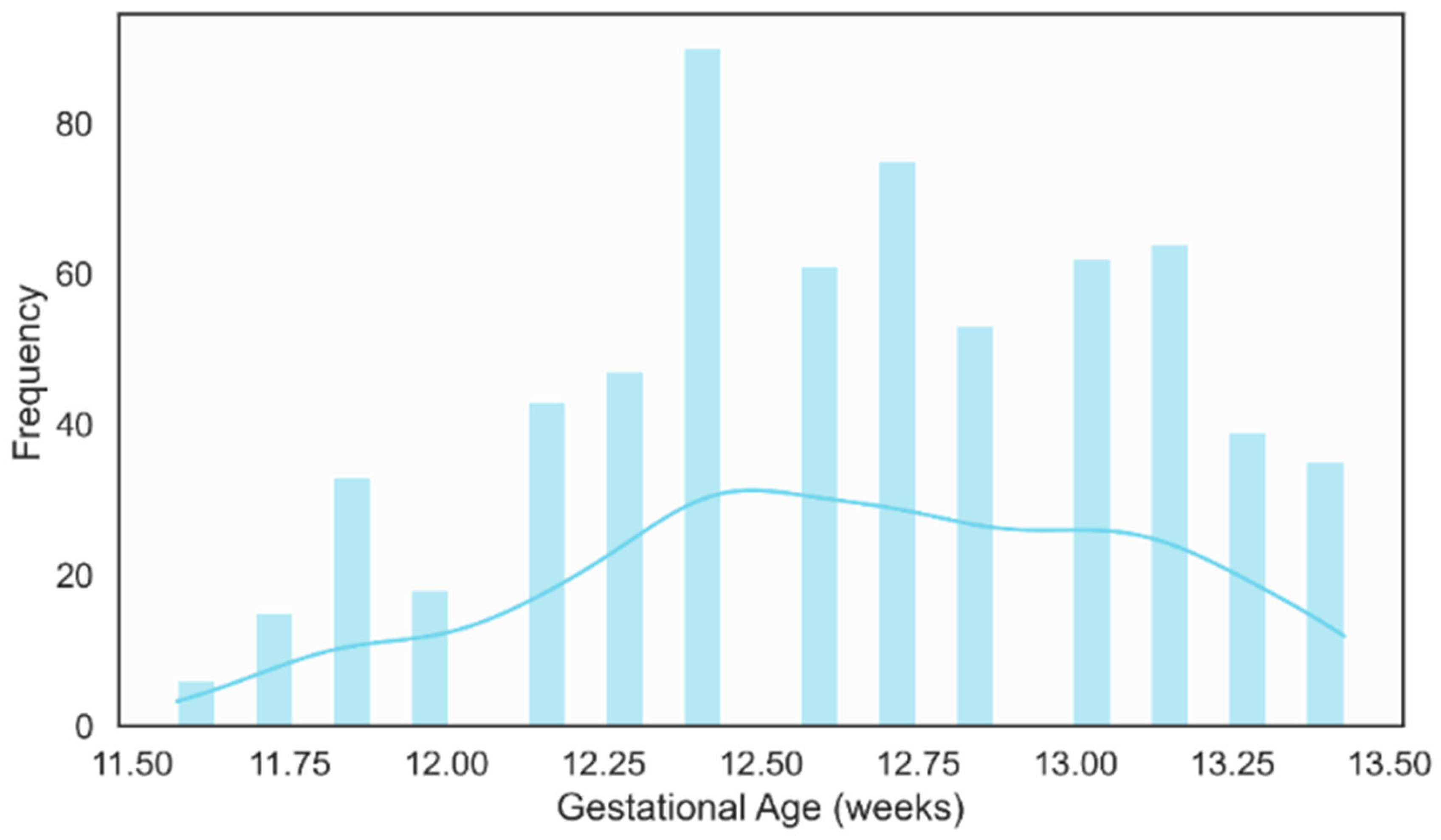

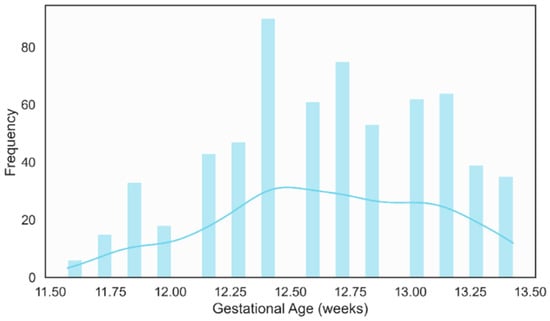

The gestational age distribution showed that most examinations were performed between 12 and 13 weeks of gestation, as illustrated in Figure 12. This clustering aligning well with international guidelines that recommend NT measurement in the 11–13 weeks + 6 days [59]. This concentration within the optimal screening period reinforces the clinical relevance of the dataset and ensures that the developed models are trained on images acquired under appropriate temporal conditions for NT assessment.

Figure 12.

Distribution of Gestational Age (weeks).

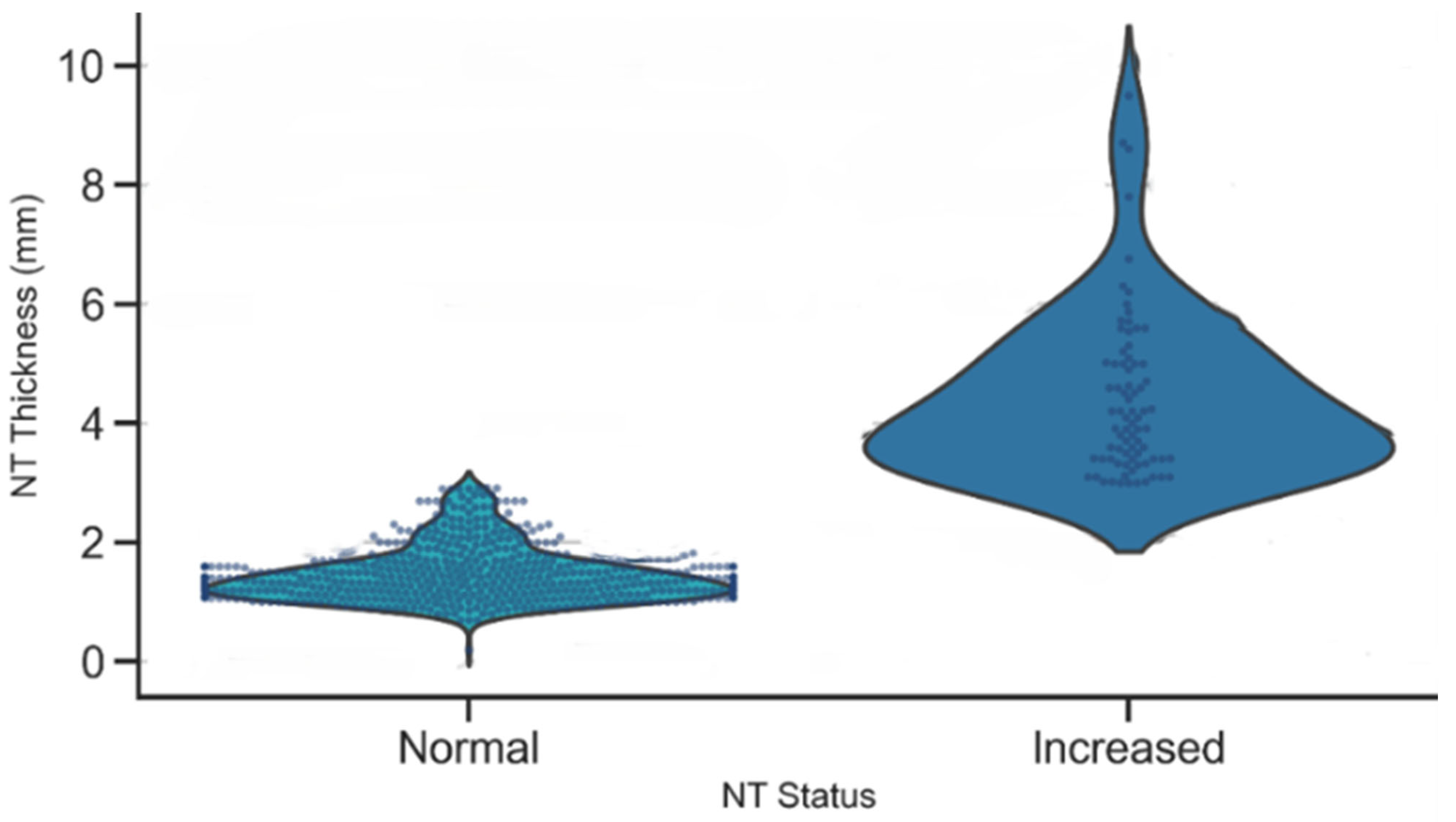

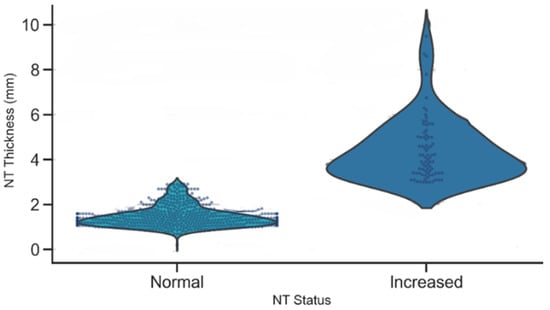

A violin plot of NT thickness stratified by NT status demonstrated a clear separation between the Normal and Increased groups, as illustrated in Figure 13. Normal cases were tightly clustered around lower NT values, while the Increased group exhibited a higher median and a broader spread, with many measurements exceeding the 3 mm clinical threshold. This distinct separation underscores the strong discriminatory power of NT thickness as a biomarker for identifying fetuses at elevated risk of chromosomal or structural abnormalities.

Figure 13.

Distribution of NT thickness by NT status.

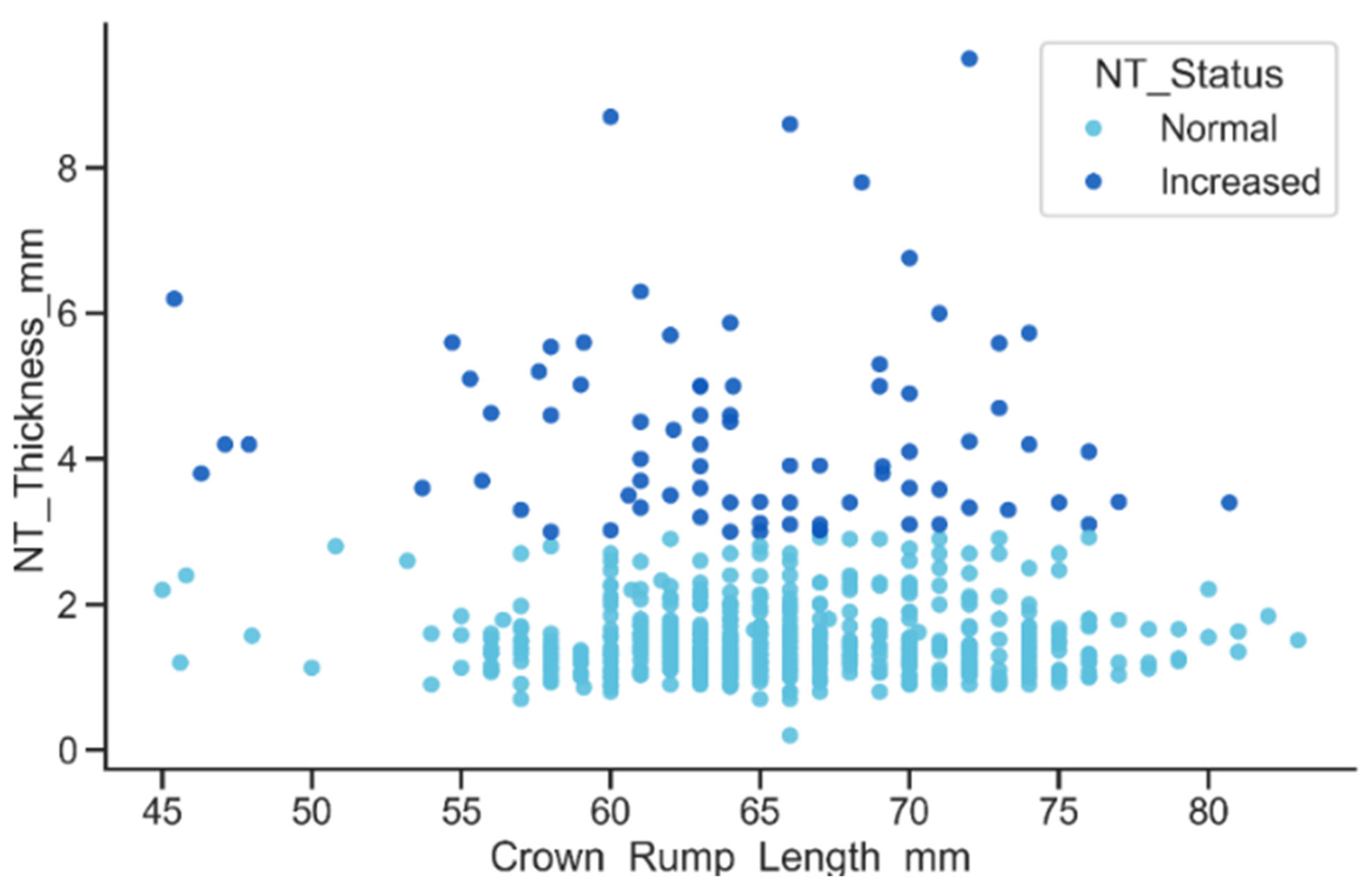

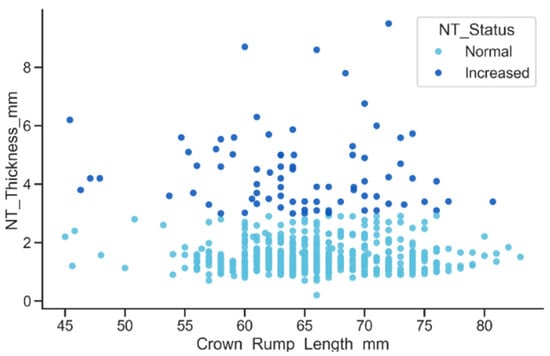

The relationship between CRL and NT thickness, stratified by NT status, showed that although NT thickness increases slightly with CRL, the Increased NT group consistently presents markedly higher values across the entire CRL range, as shown in Figure 14. Many of these measurements exceeded the 3 mm clinical threshold, resulting in a pronounced vertical separation between the Normal and Increased groups.

Figure 14.

Relationship between CRL and NT thickness by NT status.

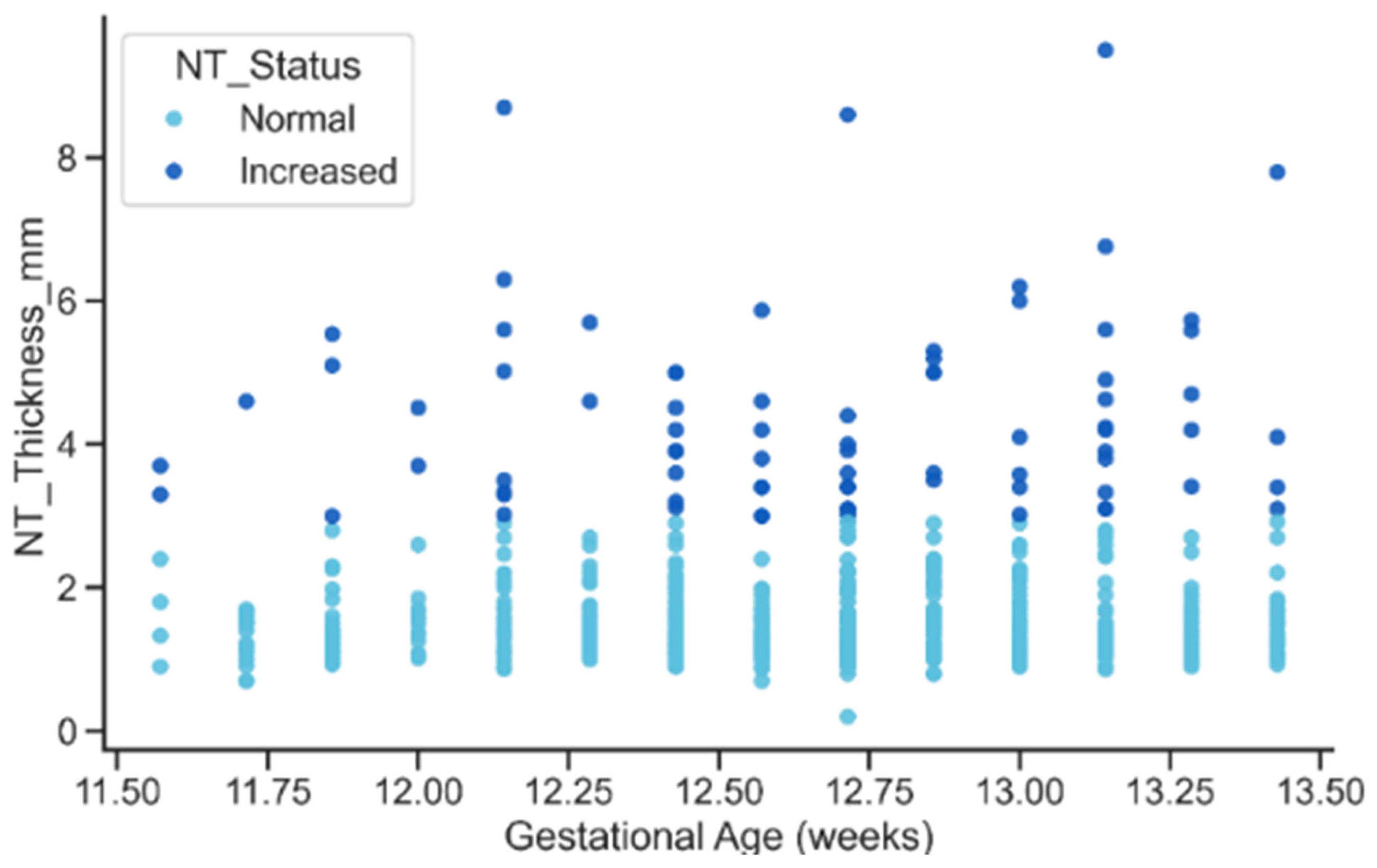

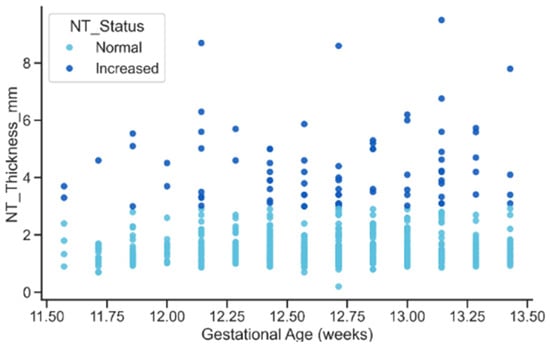

The relationship between gestational age and NT thickness revealed a mild upward trend in NT with advancing gestation for both status groups. However, the key feature visible in Figure 15, was the persistent vertical separation between Normal and Increased cases: elevated NT values remained substantially higher across all gestational ages. This pattern reinforces the interpretation that Increased NT reflects an underlying pathological process rather than a normal maturational change associated with fetal growth.

Figure 15.

Relationship between gestational age and NT Thickness by NT Status.

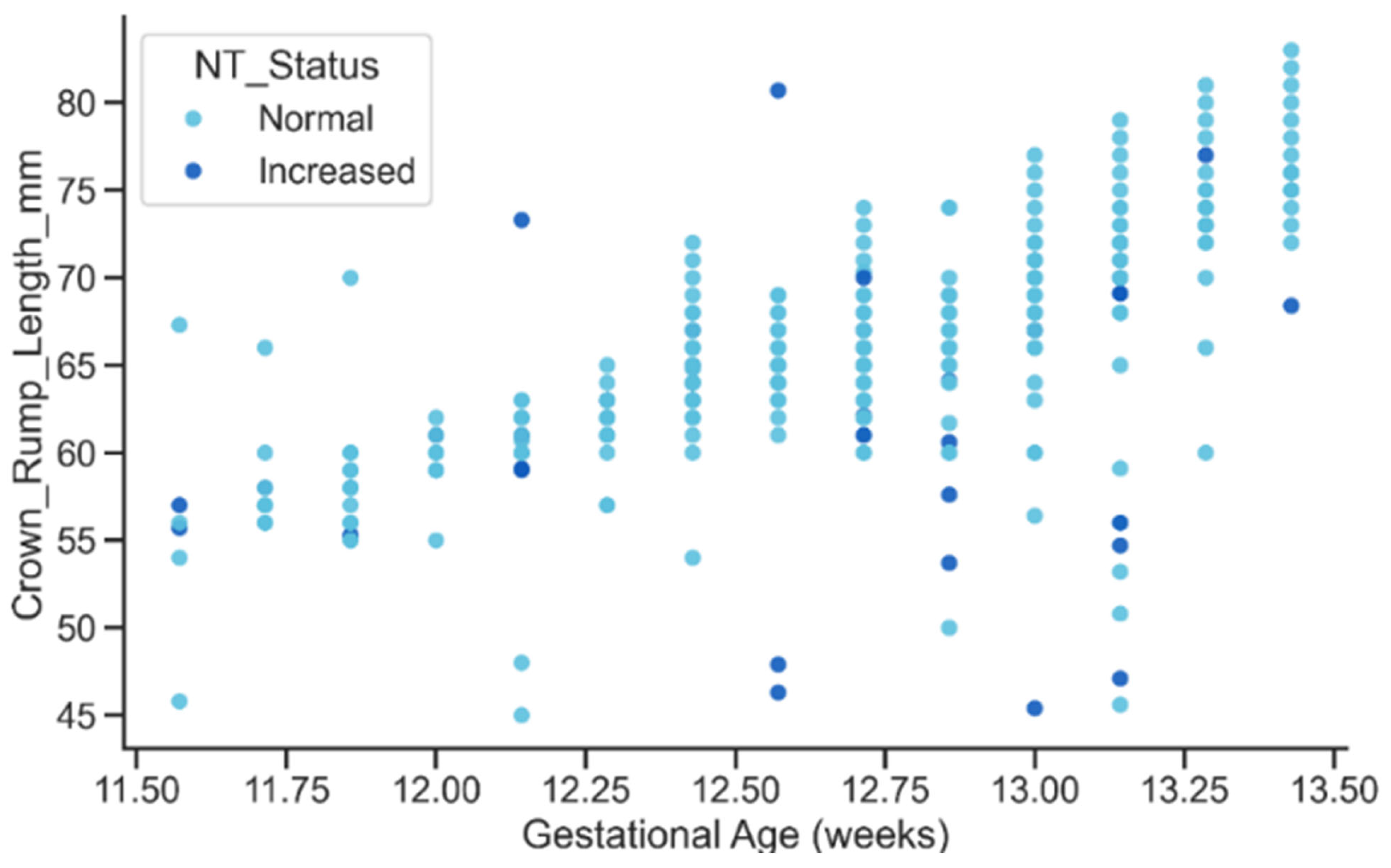

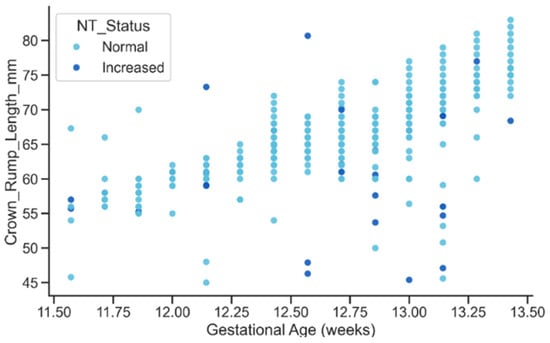

The relationship between gestational age and CRL displayed the expected strong positive growth trend, with CRL increasing steadily as gestational age advanced as shown in Figure 16. Both Normal and Increased NT groups followed similar growth trajectories, although the Increased group exhibited slightly greater dispersion at later gestational ages. This overall pattern confirms the biological plausibility of the extracted metadata and suggests that elevated NT may be subtly associated with variability in early fetal growth dynamics, an aspect that could be explored in future studies.

Figure 16.

Relationship between GA and CRL by NT Status.

3.4. Proposed Deep Learning Models

The core of this paper is an automated deep learning pipeline designed for the comprehensive analysis of NT in first-trimester fetal ultrasound images. The system is architecturally structured as a multi-stage workflow as illustrated in Figure 17, to sequentially address the challenges of medical image analysis: (1) Image Quality Assessment (IQA), (2) NT region segmentation and measurement, and (3) final risk classification (Normal or High Risk.

Figure 17.

Overview of the proposed end-to-end framework for automated NT.

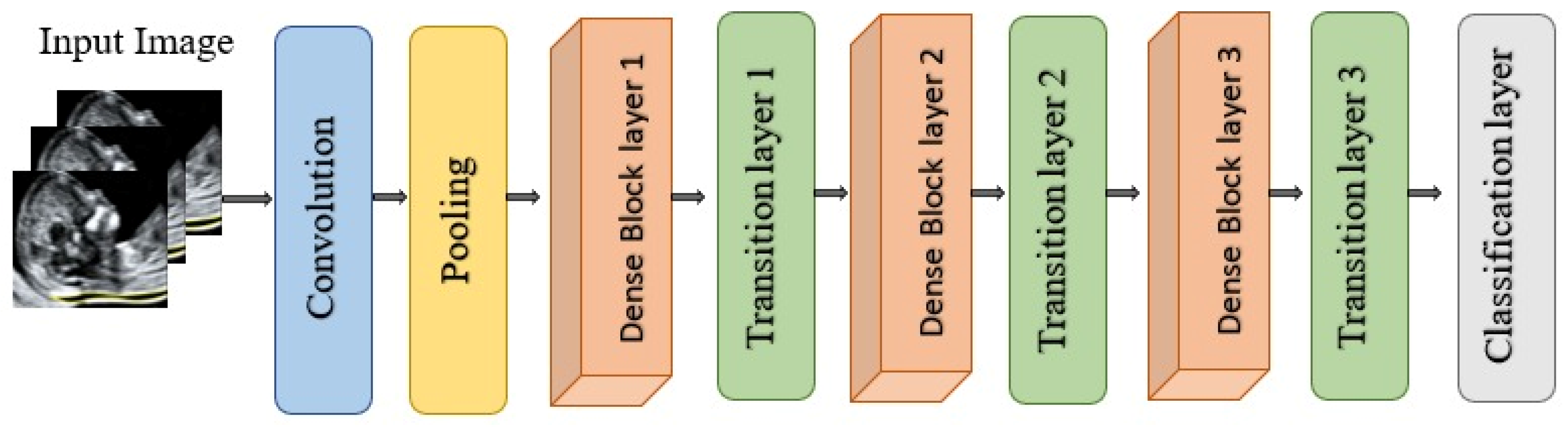

In this study, a transfer learning approach was followed, utilizing Deep Learning pre-trained models. Transfer learning is a machine-learning concept that utilizes gained knowledge from a task to enhance performance in another different but related task. The chosen models are DenseNet121 [60], VGG16 [61], VGG19 [61], ResNet18 [62], ResNet50 [62], EfficientNetB7 [63], Inceptionv3 [64], and U-Net [65]. These models were selected based on their performance and evaluation results in prior studies for similar tasks.

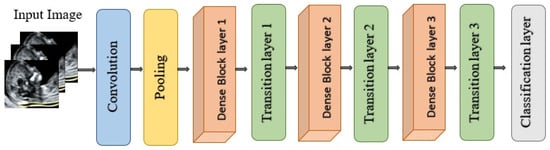

DenseNet121

DenseNet121 is a convolutional neural network architecture from the DenseNet family proposed by Huang et al. for large-scale image recognition as illustrated in Figure 18. It is characterized by dense connectivity, whereby each layer receives as input the concatenation of all feature maps produced by preceding layers and, in turn, passes its own feature maps to all subsequent layers within the same dense block. This design yields (L(L + 1)/2) direct connections for a network with (L) layers, substantially improving information flow, gradient propagation, and parameter efficiency compared with traditional feed-forward CNNs. The network is organized into multiple dense blocks separated by transition layers that perform convolution and pooling to progressively reduce spatial resolution. Within each dense block, each layer contributes a fixed number of new feature maps, referred to as the growth rate, which controls how much additional information is injected at each step while keeping the overall model compact [60]. DenseNet121 has demonstrated strong performance on benchmark classification tasks and has been widely adopted as a backbone in medical imaging due to its ability to learn rich hierarchical representations with relatively few parameters [66].

Figure 18.

Architectural design of DenseNet121.

3.5. Proposed Approaches

This study implements a multi-stage deep learning pipeline for the automated analysis of NT thickness in first-trimester fetal ultrasound images. The overall framework comprises five sequential phases: Image-Quality Assessment (IQA), NT region segmentation, feature extraction from the segmented region, NT thickness measurement in millimeters, and final risk classification (Normal vs. High-Risk). This design aims to emulate the clinical workflow used by sonographers while providing a reproducible, data-driven alternative to manual assessment.

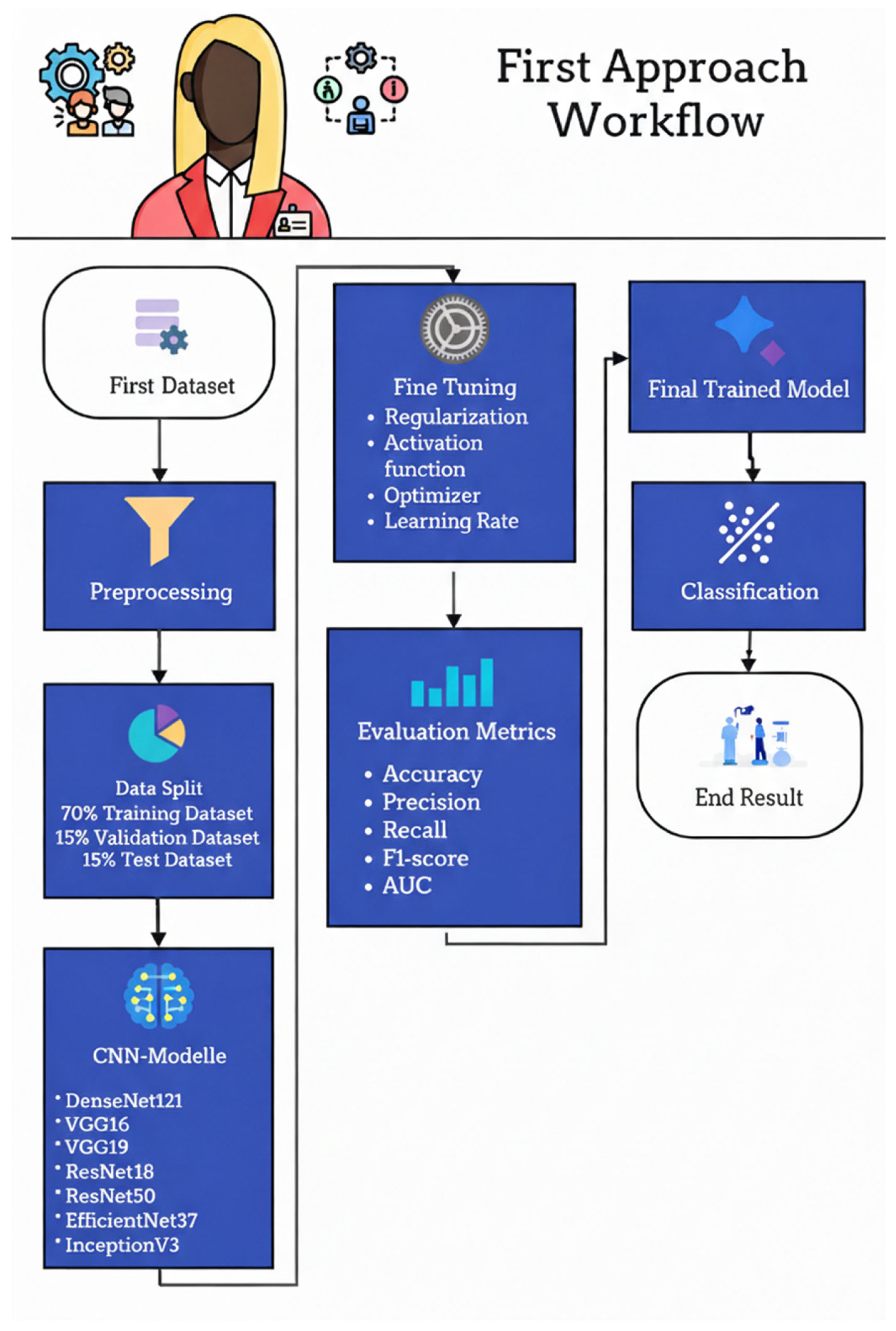

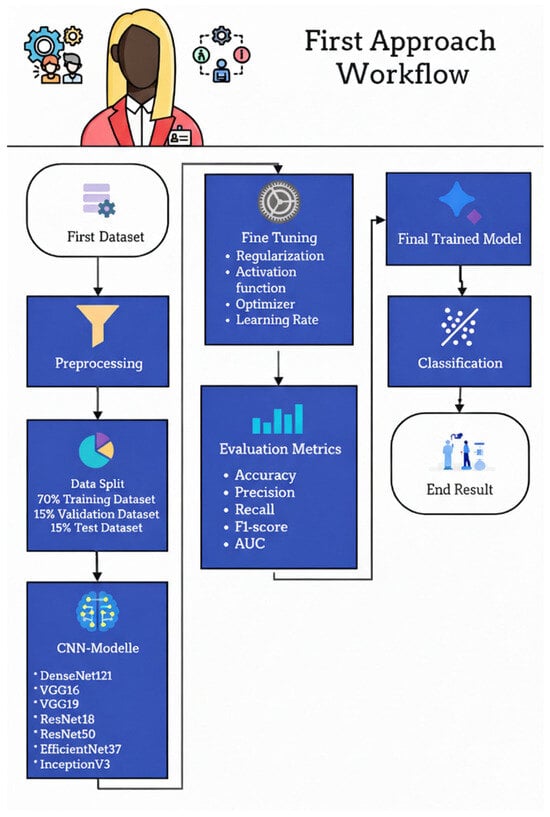

3.5.1. First Approach: Classification of Standard and Non-Standard Ultrasound Images

Figure 19 illustrates the workflow of the first approach used to classify fetal ultrasound images as Standard plane or Non-Standard plane. The pipeline begins with the first dataset of labeled mid-sagittal images, which undergoes a preprocessing stage to normalize resolution, intensity, and format. The preprocessed images are then split into three subsets: 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. The training and validation subsets are used to fine-tune a set of ImageNet-pretrained convolutional neural networks—DenseNet121, VGG16, VGG19, ResNet18, ResNet50, EfficientNetB7, and InceptionV3—by adjusting regularization strategies, activation functions, optimizer choice, and learning rate. Model performance is assessed on the held-out test set using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC, and the best-performing configuration is selected as the final trained model. This model is subsequently deployed to classify new ultrasound images into Standard or Non-Standard quality categories in the final classification stage.

Figure 19.

First approach workflow.

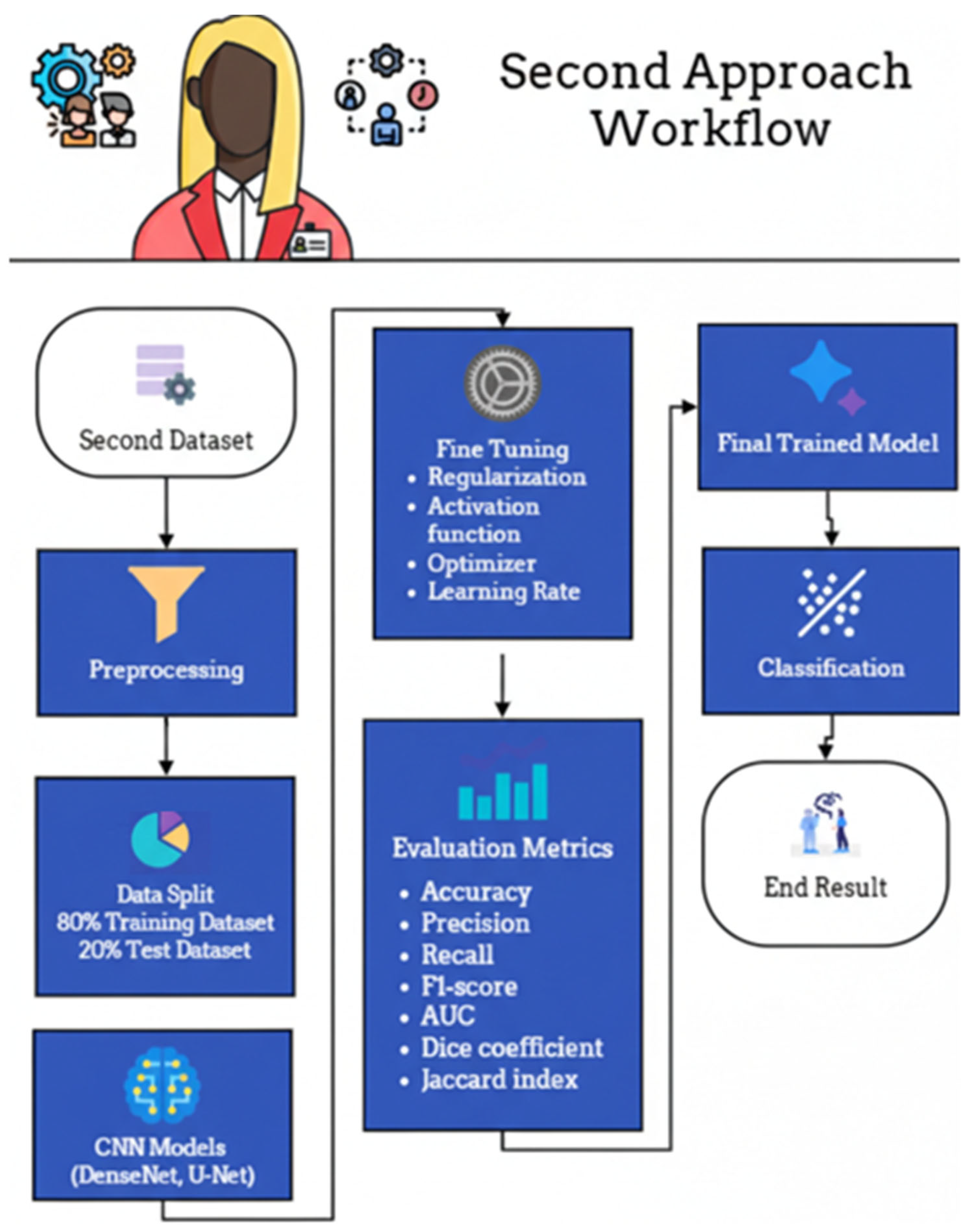

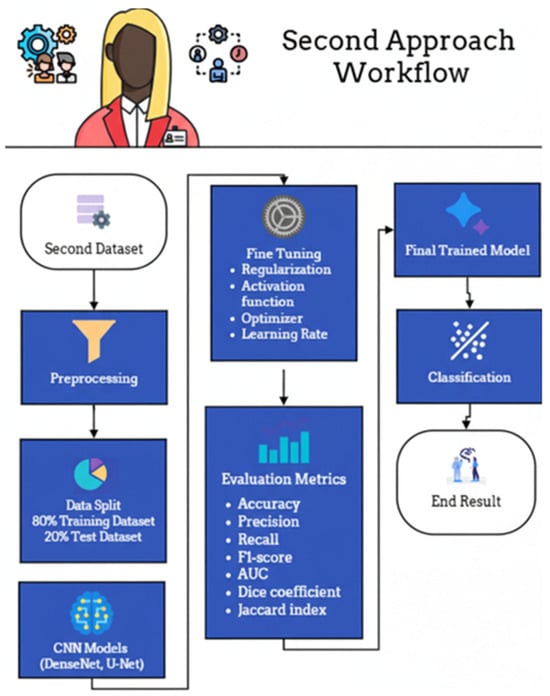

3.5.2. Second Approach: NT Region Segmentation, Measurement, and Risk Classification

The experimental workflow for the second dataset, comprising fetal ultrasound images categorized as Normal or High-Risk, is delineated in Figure 20. Following standardized preprocessing, the data was partitioned into a training set (80%) and a held-out test set (20%). The training phase involved the optimization of DenseNet- and U-Net–based architectures through systematic fine-tuning of regularization parameters, activation functions, optimizers, and learning rates. Model efficacy was rigorously assessed using a multi-faceted evaluation suite—including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, Area Under the Curve (AUC), Dice coefficient, and Jaccard index—to provide a holistic view of both classification and segmentation performance. To ensure a transparent and methodologically sound comparison, the U-Net baseline was intentionally implemented as a foundational, unenhanced reference. This implementation strictly adhered to the original architecture proposed by Ronneberger et al. [65], deliberately omitting contemporary enhancements such as attention mechanisms, residual/dense connections, or pre-trained encoders. By maintaining identical data splits and preprocessing pipelines across all models, this study ensures that the performance differential directly reflects the inherent architectural advantages of the proposed DenseNet-based framework under controlled experimental conditions.

Figure 20.

Second approach workflow.

4. Results

This section presents results obtained from both datasets. Section 4.1 presents results obtained from the image-quality assessment using the Fetus Framework dataset. Whereas, Section 4.2 presents results for NT region segmentation followed by thickness measurement and risk classification using the NHOG dataset.

4.1. Results of the First Dataset Approach

Image-Quality Assessment (IQA)

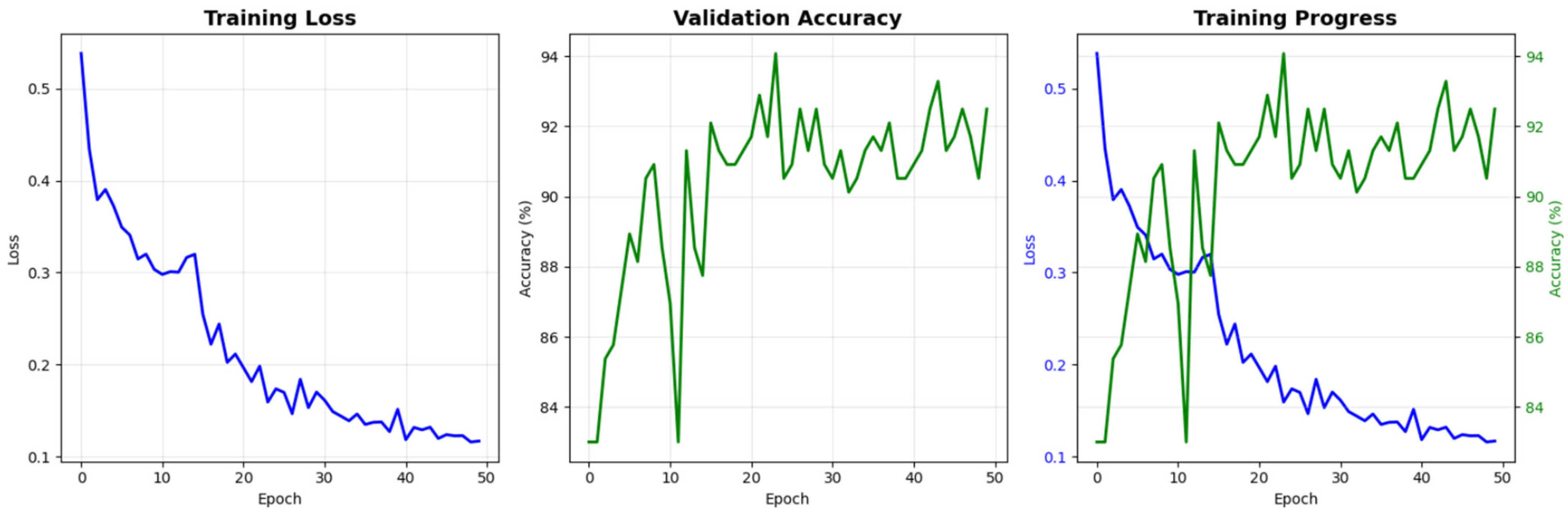

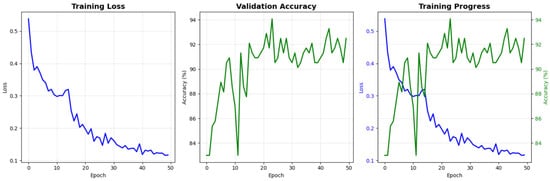

Figure 21 presents the learning curves of the proposed model over 50 training epochs. The training loss shows a consistent monotonic decrease from approximately 0.53 at the first epoch to nearly 0.10 at the final epoch, indicating effective optimization of the network parameters. In parallel, the validation accuracy rapidly increases during the initial epochs and then stabilizes in the range of 90–94%, suggesting that the model generalizes well to unseen data without evident overfitting. The combined view of loss and accuracy trajectories demonstrates stable convergence and supports the reliability of the training procedure adopted in this study.

Figure 21.

Training and validation performance of the proposed model for NT image-quality assessment. The blue line indicates training loss, while the green line indicates validation accuracy.

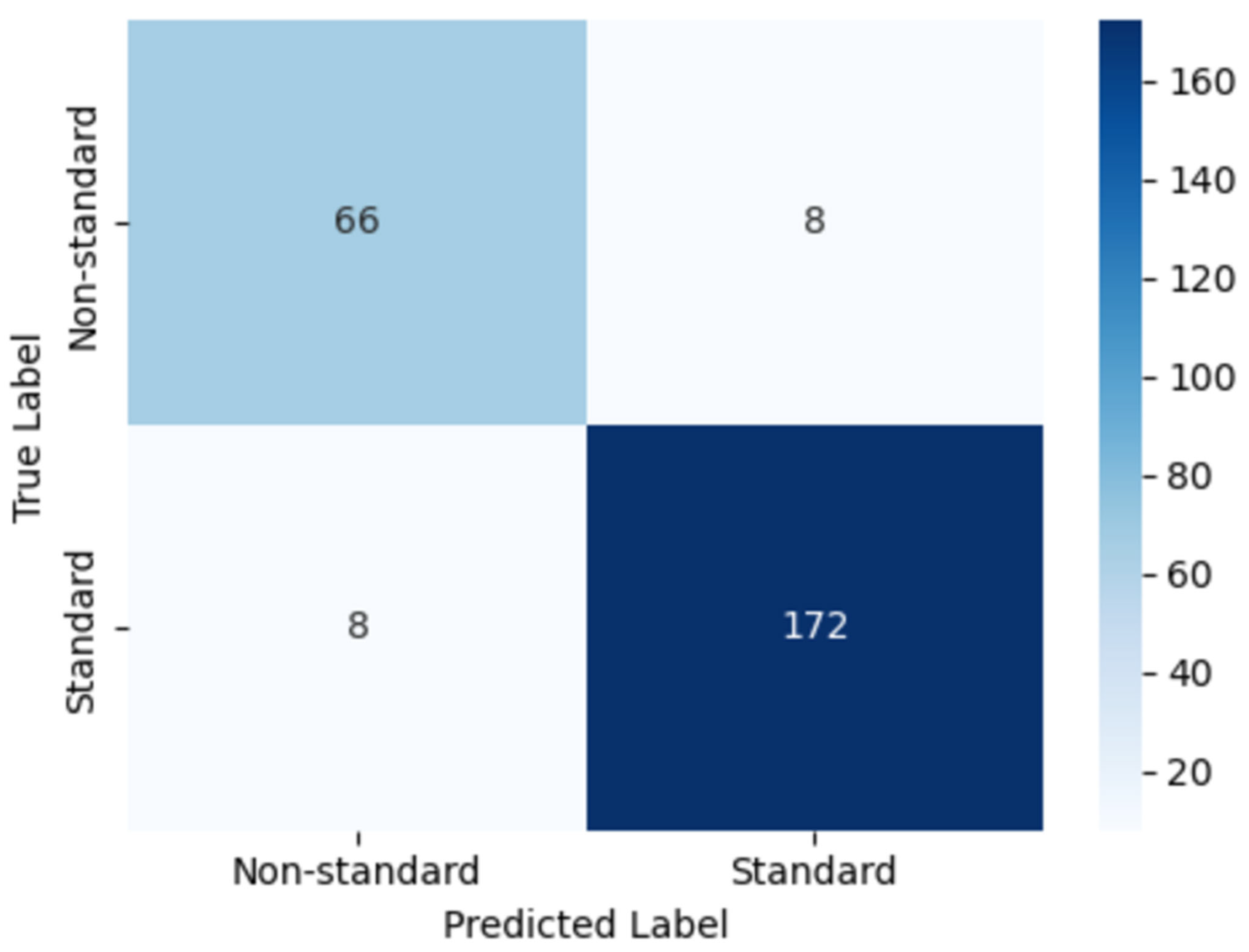

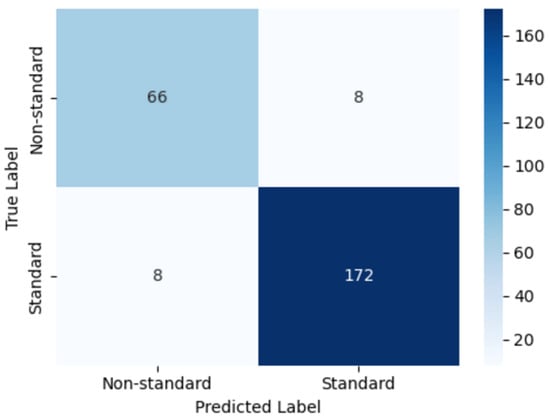

Figure 22 illustrates the confusion matrix obtained on the held-out test set. The model correctly classified 172 images as standard and 66 images as non-standard plane, with only 8 misclassified samples in each class. This distribution corresponds to a high proportion of true positives and true negatives in both categories, reflecting the model’s strong ability to distinguish clinically acceptable (standard plane) from suboptimal (non-standard plane) NT ultrasound images. The low number of misclassifications in each cell further indicates that the classifier maintains a balanced performance across classes, which is particularly important for avoiding systematic bias toward either standard or non-standard cases.

Figure 22.

Confusion matrix of the proposed model for classifying standard versus non-standard planes.

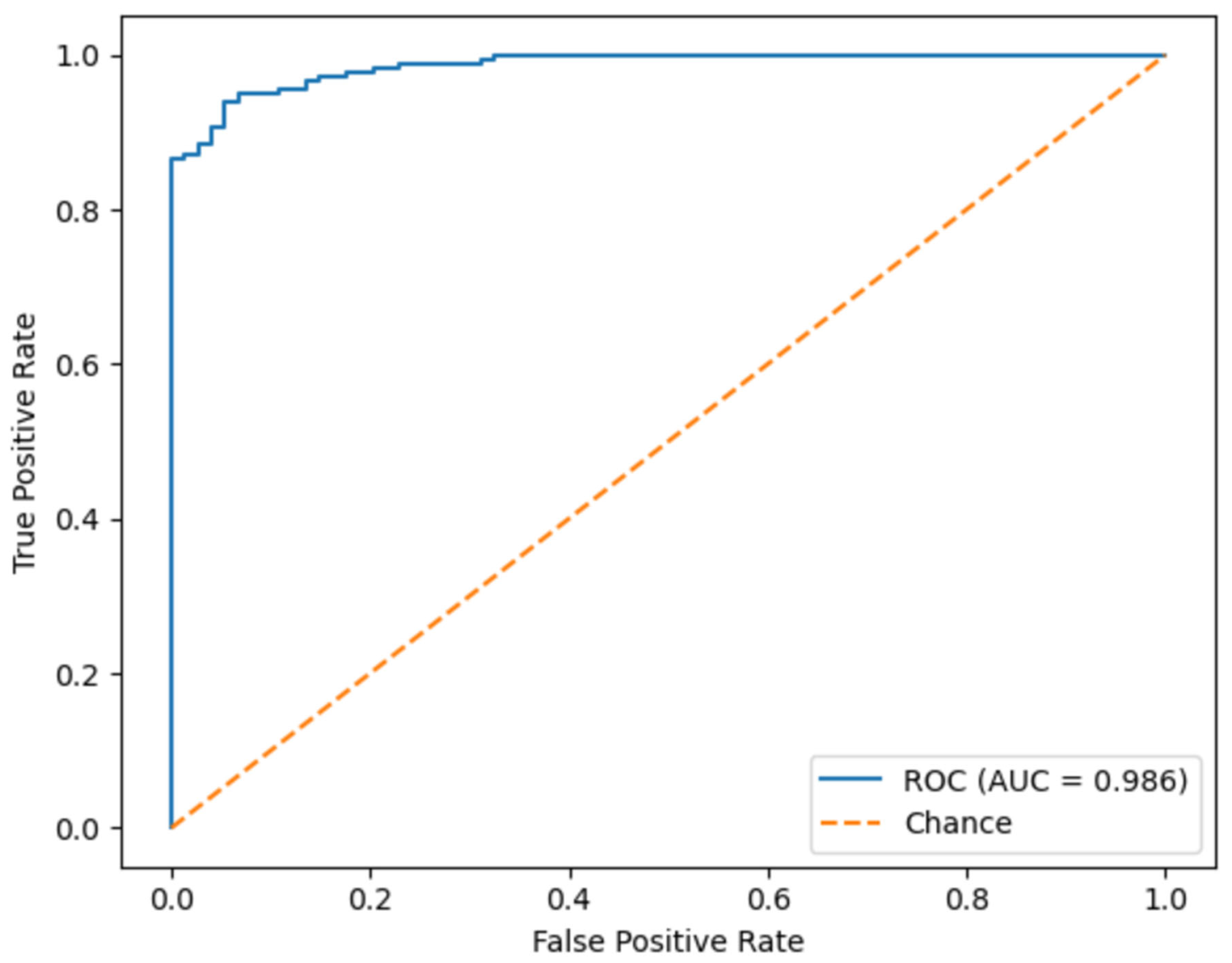

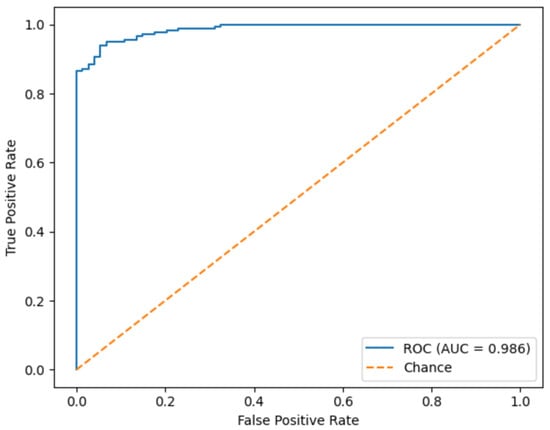

Figure 23 shows the ROC curve of the proposed model, summarizing its discriminative capability across all possible decision thresholds. The curve rises steeply toward the upper-left corner of the plot, and the corresponding Area Under Curve reaches 0.986. This near-perfect AUC value indicates an excellent separation between standard and non-standard planes NT images and a very low probability that a standard plane is ranked above a standard one. Such performance suggests that the model remains highly reliable even when the classification threshold is adjusted to prioritize sensitivity or specificity according to clinical requirements.

Figure 23.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the proposed model.

Table 4 summarizes the quantitative performance of the proposed model on the test set. The classifier achieved an overall accuracy of 0.94, with precision, recall (sensitivity), and F1-score all equal to 0.937. The ROC of 0.986, these results demonstrate that the model attains both high correctness and strong balance between detecting standard and standard planes. The close agreement between precision and recall indicates that the model rarely produces false alarms while still maintaining a high detection rate, underscoring its suitability as a robust decision-support component for automated NT ultrasound image-quality assessment.

Table 4.

Overall performance metrics.

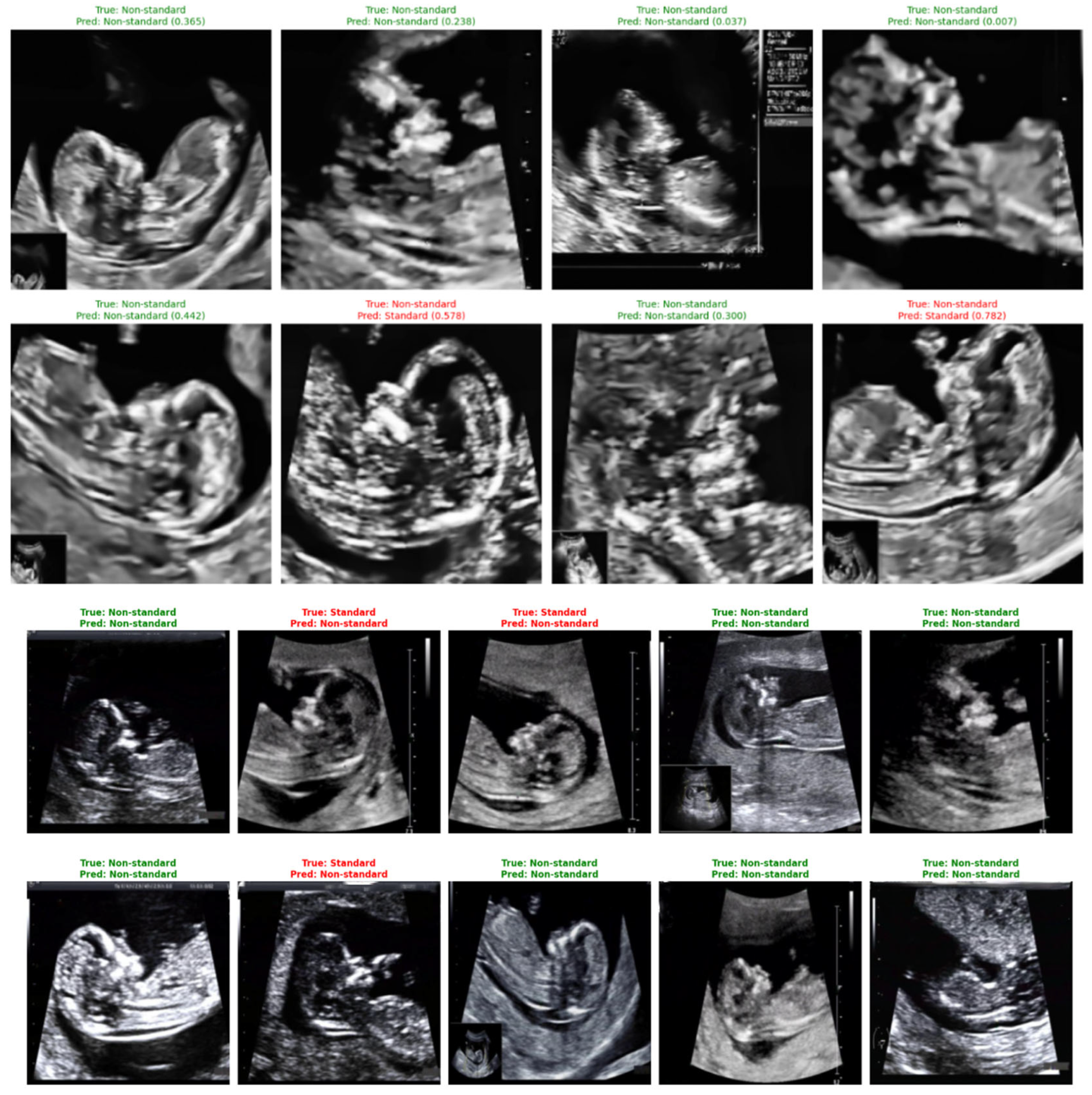

Representative classification outcomes are shown in Figure 24, illustrating both correct and incorrect predictions. Each example includes the ground-truth label, the model’s predicted label, and the associated confidence score.

Figure 24.

Sample predictions of non-standard ultrasound images using DenseNet121.

Correct predictions (shown in green) display high certainty, such as a standard plane identified with a confidence of 0.999. Misclassified cases (shown in red) typically correspond to borderline-quality images containing subtle artifacts, incomplete fetal profiles, or shadowing. These images highlight the nuanced nature of NT plane assessment and help contextualize the few observed errors.

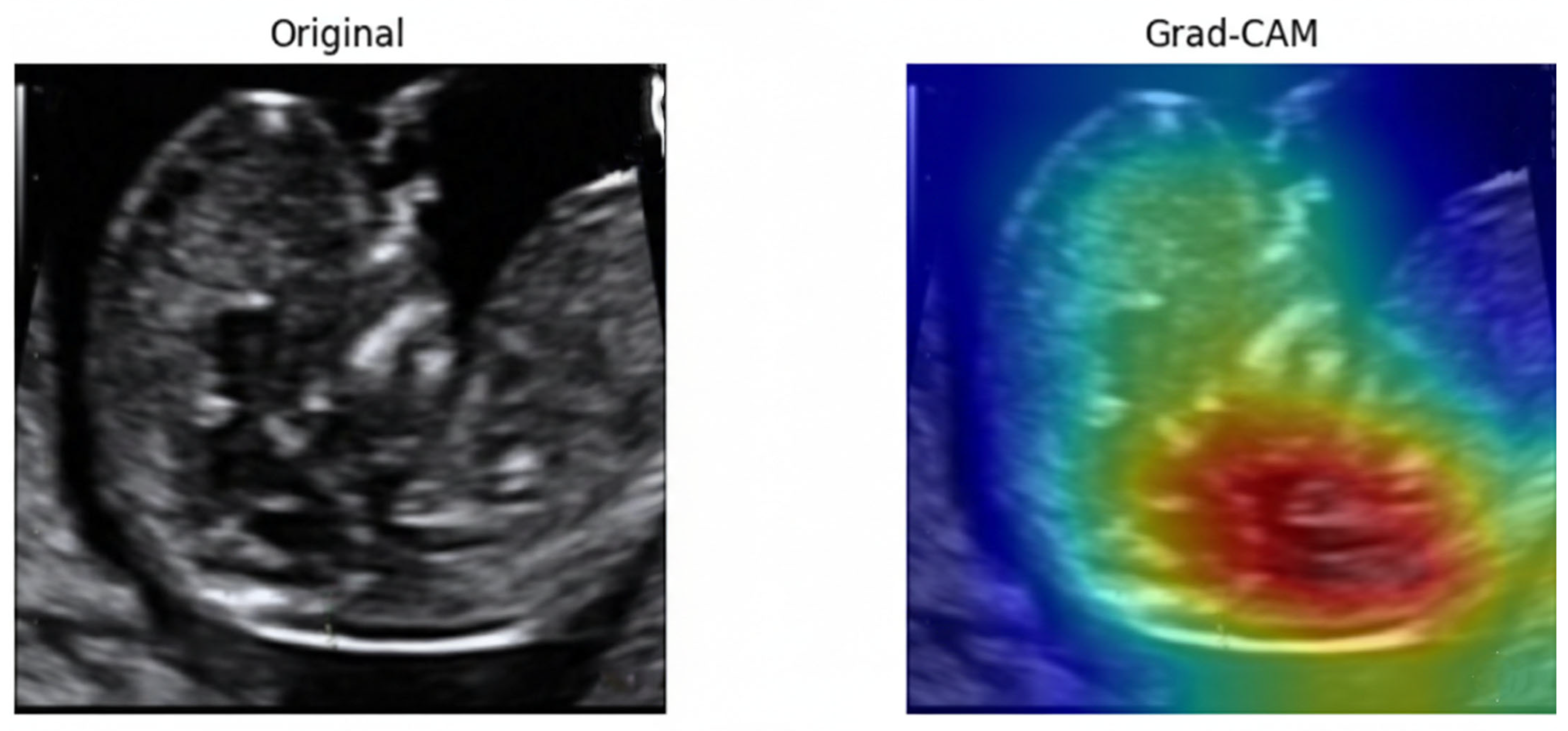

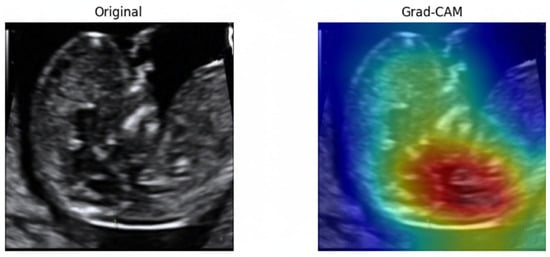

To examine the model’s decision-making process, Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) [67]. As illustrated in Figure 25, the model consistently directed its attention to the fetal nuchal region—the clinically relevant anatomical structure used for NT evaluation. Warmer colors (red, yellow) indicate regions contributing most strongly to the classification output.

Figure 25.

Original ultrasound image and corresponding Grad-CAM heatmap.

The focused activation over the NT space confirms that the model learned meaningful, physiologically aligned representations rather than relying on irrelevant background textures. This explainability further supports clinical trustworthiness and transparency in automated NT image assessment.

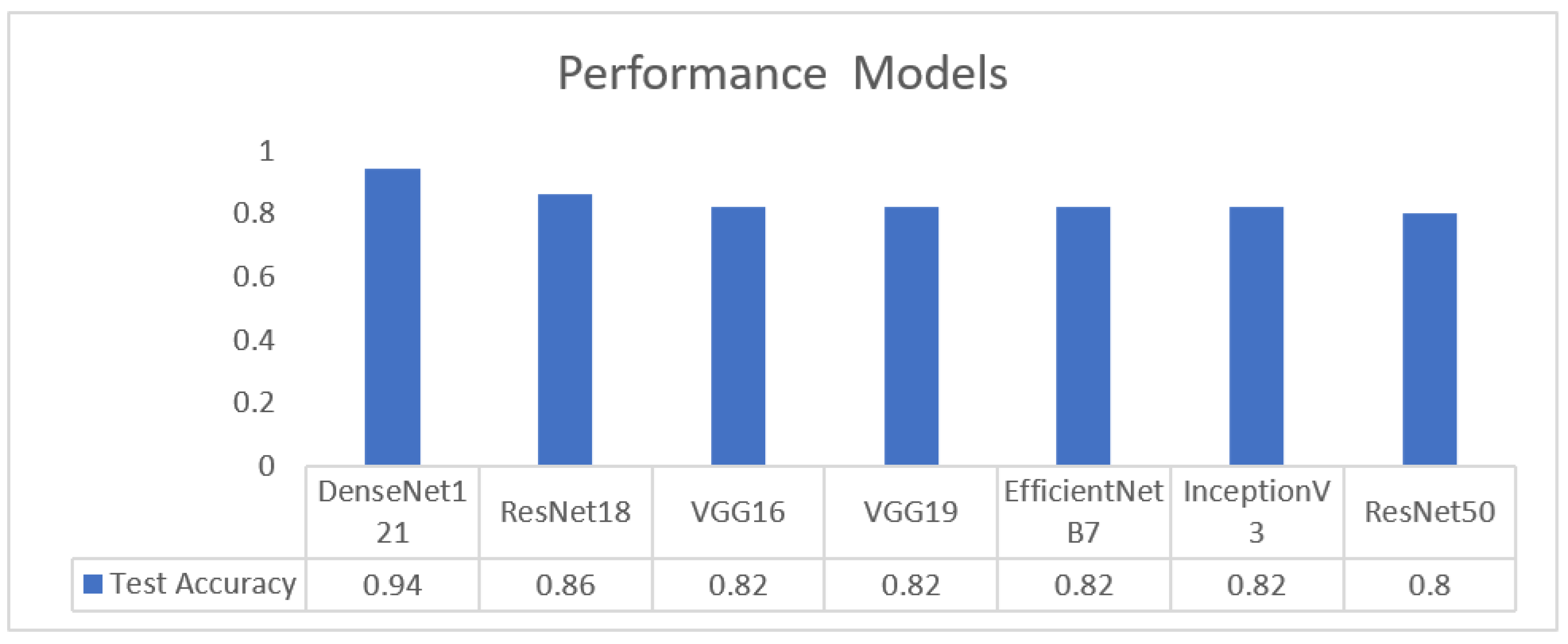

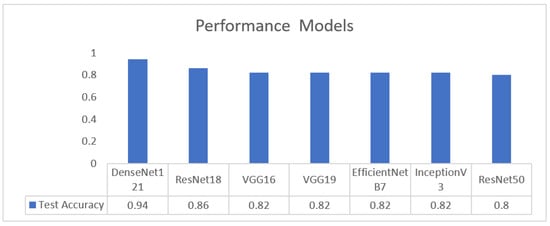

Table 5 summarizes all evaluated CNN models within the first stage of the pipeline. DenseNet121 delivered the highest and most consistent performance across accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC, establishing it as the most reliable architecture for the image-quality assessment task.

Table 5.

Models performance comparison.

As illustrated in Figure 26, DenseNet-121 achieves the highest test accuracy (0.94), outperforming all other evaluated models. ResNet-18 attains an accuracy of 0.86, while VGG16, VGG19, EfficientNet-B7, and InceptionV3 exhibit comparable performance at approximately 0.82. ResNet-50 shows the lowest test accuracy at 0.80.

Figure 26.

Performance metrics across models.

4.2. Results of the Second Dataset Approach

4.2.1. Segmentation

Image segmentation is the process of partitioning an image into meaningful regions, typically by assigning each pixel to a specific class such as target structure or background, and is a core step in medical image analysis for precise anatomical delineation [68]. In this study, segmentation is used to isolate the NT region from surrounding fetal tissues, producing a binary mask that enables accurate NT thickness measurement and subsequent risk classification for chromosomal abnormalities.

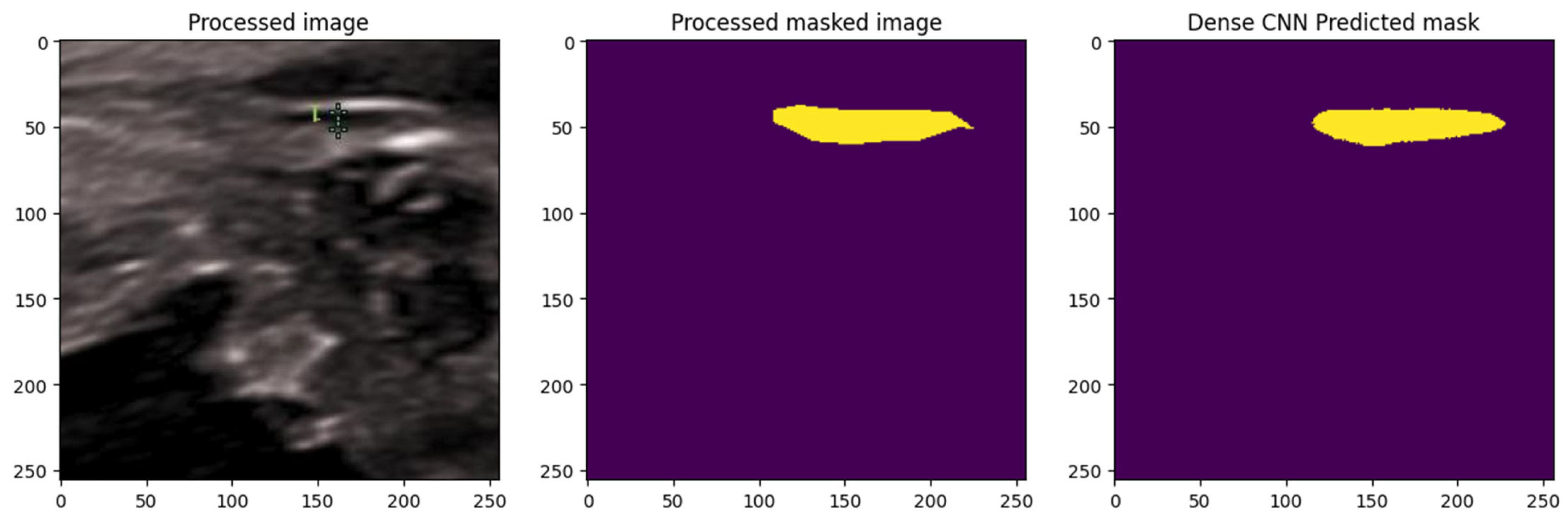

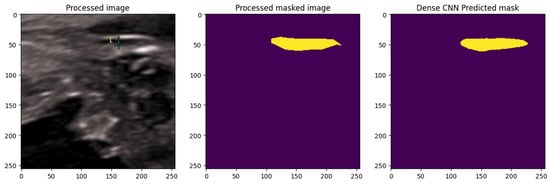

A DenseNet-based CNN was implemented, leveraging its dense connectivity for efficient feature reuse and enhanced gradient propagation, which is advantageous for segmenting subtle, low-contrast structures in ultrasound images. As illustrated in Figure 27 The model was trained with normalization and augmentation, incorporating Dropout layers (rate 0.3) for generalization.

Figure 27.

Segmentation using Dense Net: comparison between ground truth and predicted mask. The yellow color represents the NT region.

The DenseNet model generated predicted NT masks that closely matched the ground-truth annotations, successfully isolating the NT region from surrounding fetal tissues. This demonstrated the model’s effectiveness in capturing fine structural boundaries, providing a reliable basis for subsequent automated thickness measurement.

Results of Segmentation Using DenseNet Model

Table 6 summarizes the performance of the DenseNet-based segmentation model on the NHOG test set. The model achieved an overall accuracy of 0.989, with a high true positive rate (recall) of 0.921 and specificity of 0.993, indicating strong ability to detect the NT region while effectively rejecting background. Precision (PPV) reached 0.874 and the negative predictive value (NPV) 0.996, yielding a balanced F1-score of 0.897. The Dice coefficient (0.897) and Jaccard index (0.813) confirm a substantial overlap between predicted and ground-truth masks, whereas error rates remained very low (FNR = 0.079, FPR = 0.007, FDR = 0.126, FOR = 0.004). Together, these metrics demonstrate that the DenseNet model provides accurate and clinically reliable NT segmentation.

Table 6.

Performance metrics of DenseNet segmentation model.

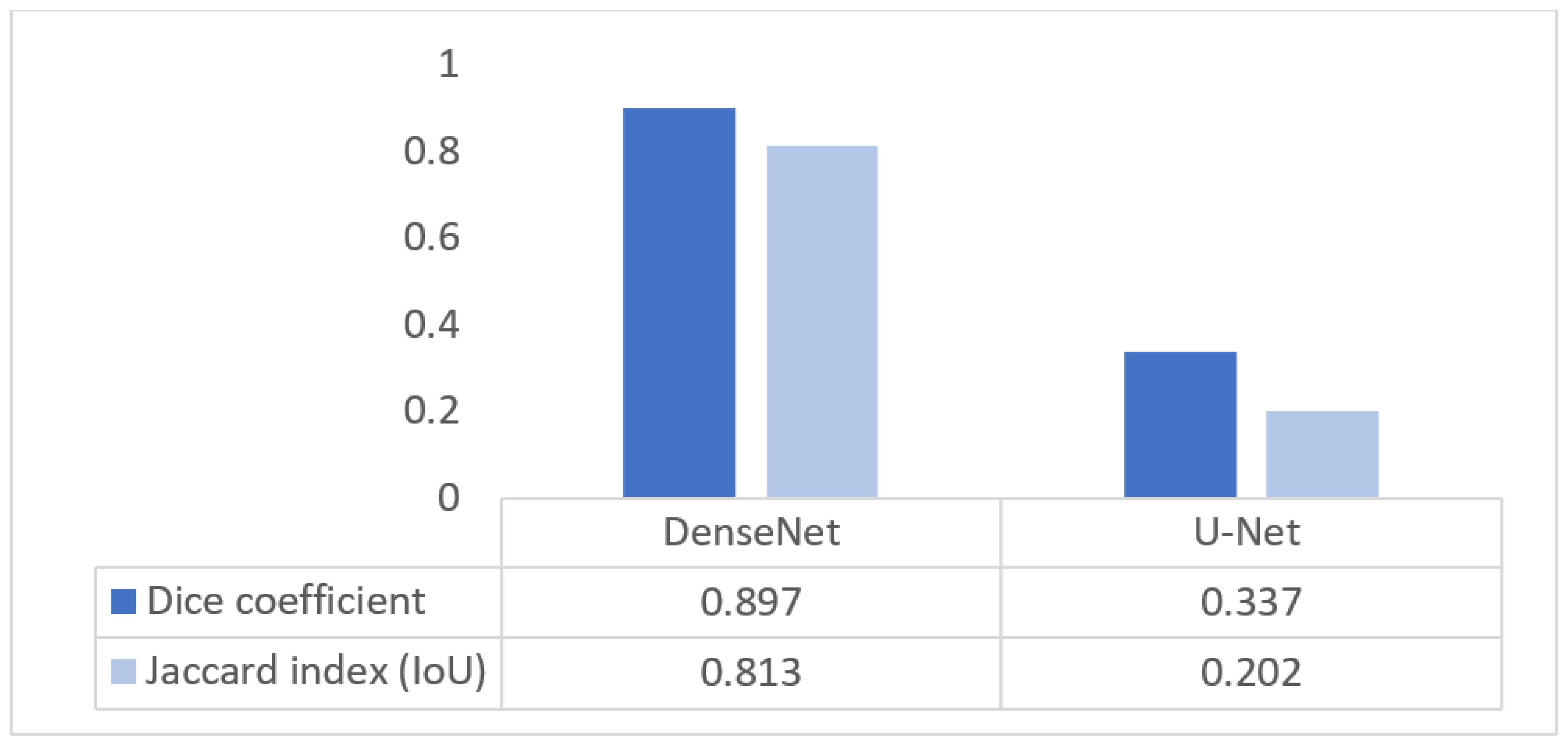

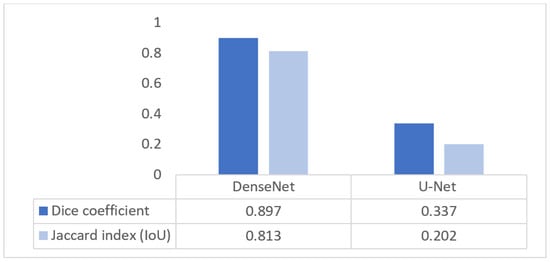

Figure 28 compares the segmentation performance of DenseNet and U-Net using Dice and IoU metrics. DenseNet achieves a Dice score of 0.897 and an IoU of 0.813, while U-Net attains 0.337 and 0.202, respectively. The lower Dice score of U-Net is attributable to the use of the original, unmodified architecture, which is known to struggle with small, low-contrast structures such as the nuchal translucency region due to aggressive downsampling and limited multiscale feature representation. In contrast, DenseNet’s dense connectivity enables better preservation of fine boundary information, leading to substantially improved segmentation accuracy.

Figure 28.

Segmentation quality Dice/IoU for DenseNet and U-Net.

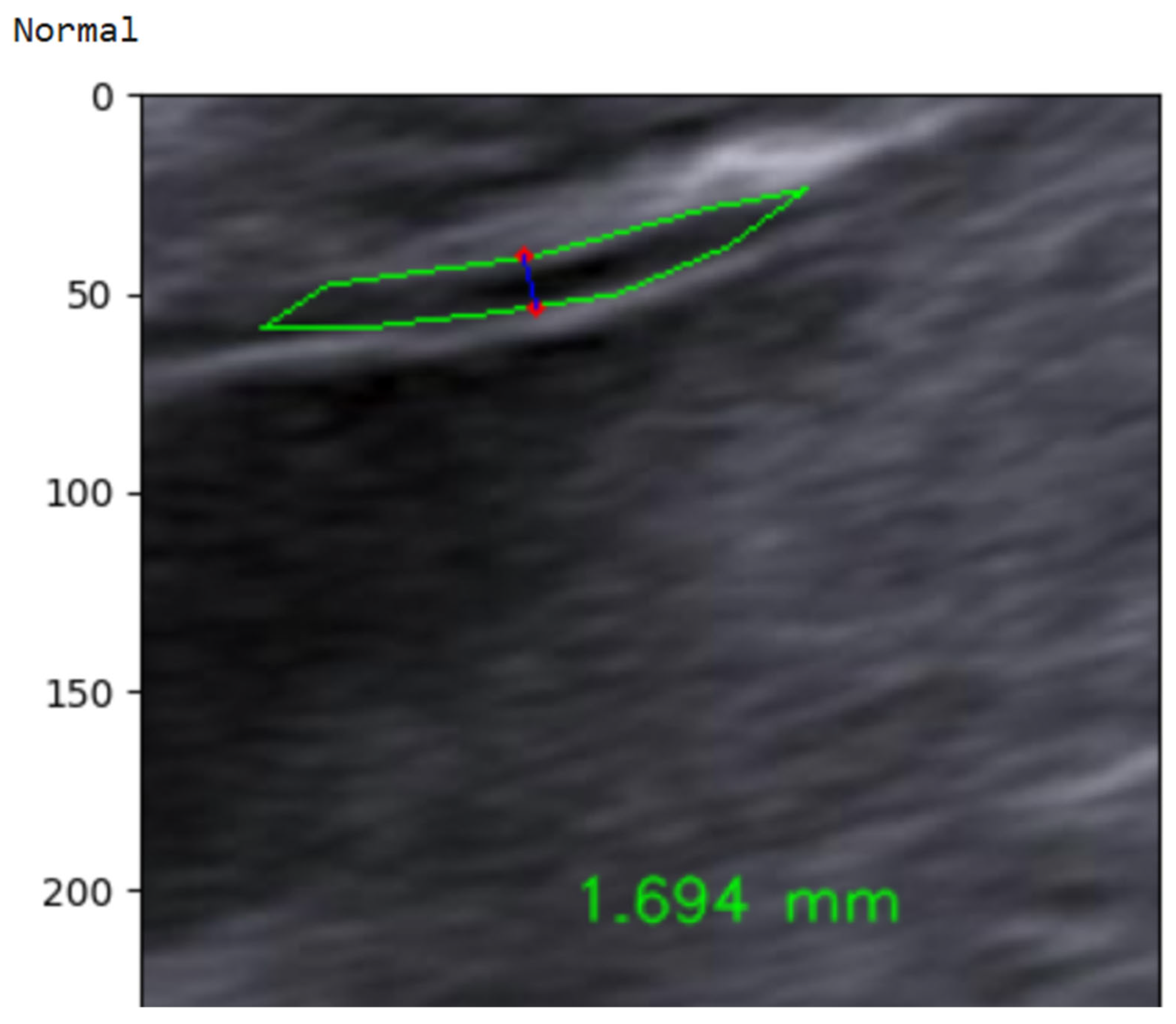

4.2.2. NT Measurement

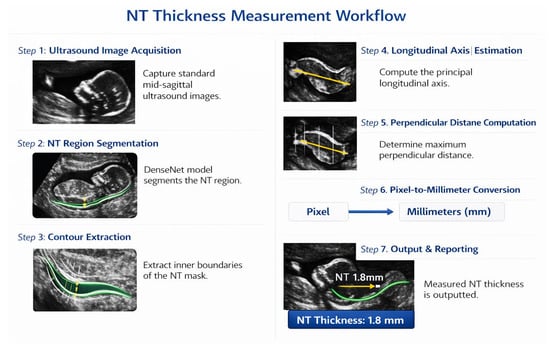

NT thickness was estimated from the DenseNet-derived NT segmentation mask using a geometry-based measurement strategy consistent with clinical standards and prior studies. Following segmentation, the NT region was isolated, and its inner boundaries were extracted to represent the translucency contour. In accordance with FMF [69] and ISUOG guidelines [58], NT thickness was defined as the maximum distance between the inner borders of the translucency, rather than a single fixed-width measurement.

To obtain this value, the principal longitudinal axis of the NT contour was estimated, and multiple perpendicular cross-sections were evaluated along this axis. For each cross-section, the Euclidean distance between opposing contour intersection points was computed, and the maximum perpendicular distance was selected as the NT thickness in pixel units. The pixel-based measurement was subsequently converted to millimeters using a calibrated pixel-to-millimeter ratio derived from the ultrasound acquisition settings. This approach aligns with established NT measurement protocols and ensures anatomically meaningful and clinically comparable results, as reported in previous AI-based NT measurement studies. The complete measurement workflow, from segmentation mask to millimeter-scale NT estimate, is illustrated in Figure 29.

Figure 29.

NT measurement workflow.

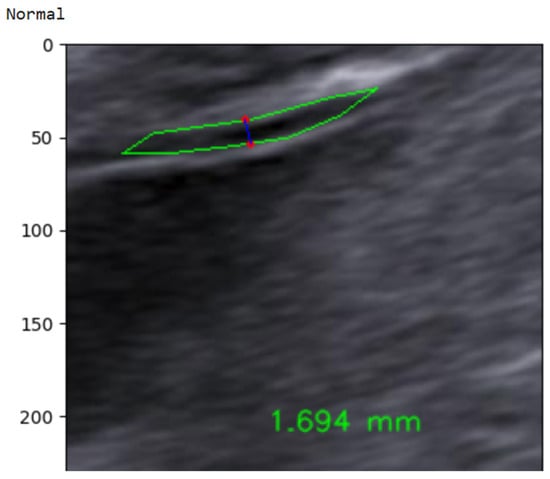

4.2.3. Classification

In the final step, the continuous NT thickness is mapped to a binary risk label using a 2.5 mm clinical threshold. As illustrated in Figure 30, an automatically measured NT value of 1.694 mm is classified as Normal, whereas measurements ≥ 2.5 mm are labeled High-Risk. This simple thresholding rule yields an interpretable, clinically aligned decision that directly reflects current first-trimester screening practice [70]. To address the class imbalance in the NHOG dataset, several mitigation strategies were employed during model training. A weighted cross-entropy loss function was used to assign higher penalties to misclassifications of the minority (High-Risk) class. In addition, targeted data augmentation was applied specifically to high-risk samples to artificially increase their effective representation. Model performance was evaluated using a comprehensive set of metrics, including sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1-score, rather than relying solely on overall accuracy.

Figure 30.

Example of automated NT measurement for a normal case.

Table 7 summarizes the absolute error between automated and expert NT measurements. The framework achieved high measurement precision, with 33.18% of cases differing by <0.5 mm and 55.47% within 1 mm of the reference annotations. Larger deviations were uncommon: only 6.82% of measurements exceeded 2 mm, 3.18% exceeded 3 mm, and just 1.36% were >4 mm. This error profile indicates that, in the vast majority of cases, the automated estimates remain within clinically acceptable limits and are unlikely to alter risk categorization, supporting the reliability of the proposed measurement pipeline as a decision-support tool in early prenatal screening.

Table 7.

Statistics of measured NT value differences between automated predictions and ground-truth annotations.

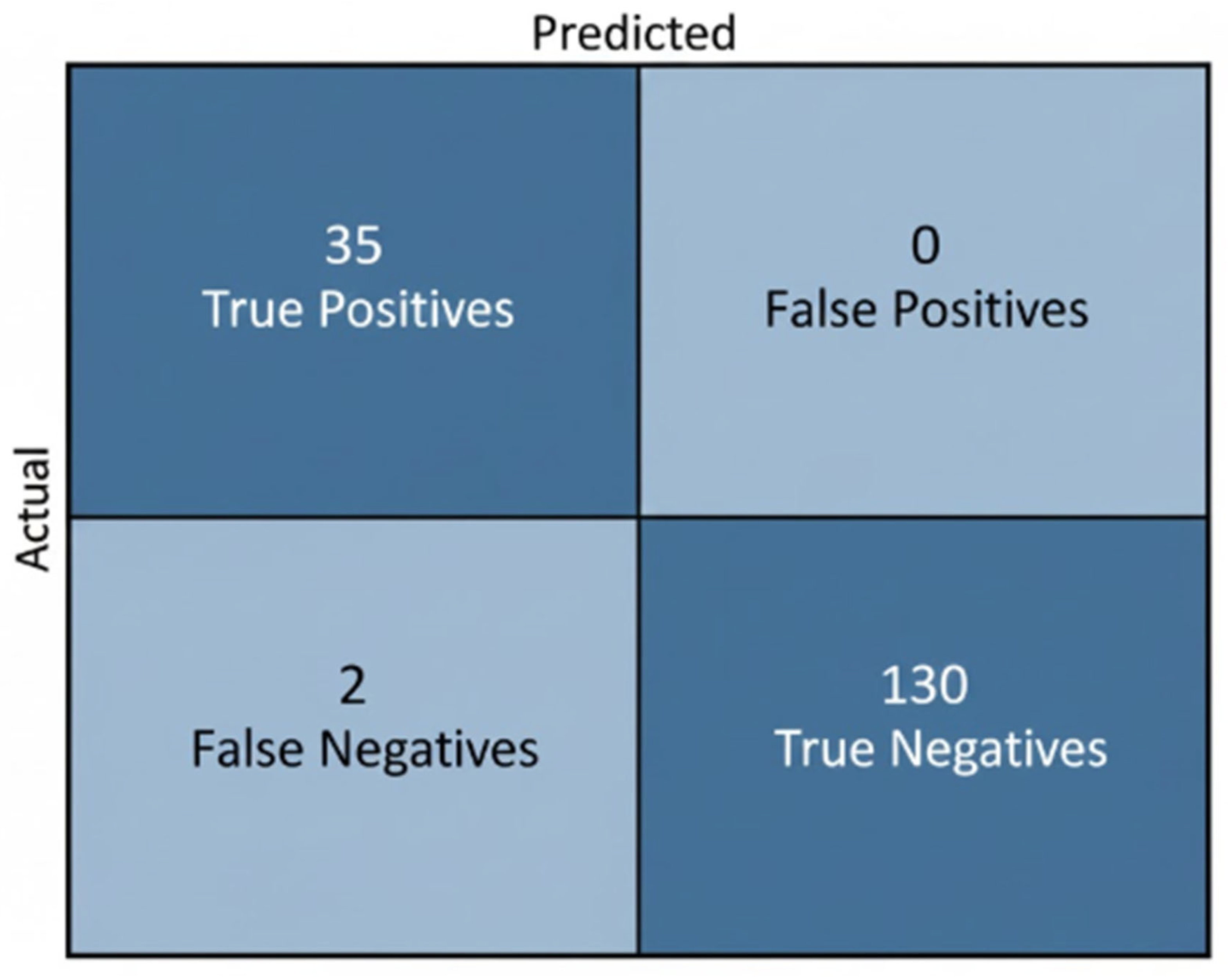

Table 8 reports the classification outcomes for NT-based risk stratification. Expert labels comprised 130 Normal and 37 High-Risk fetuses, while the model predicted 125 Normal and 35 High-Risk cases. Although a subset of high-risk fetuses was misclassified as normal, the predicted distribution shows good alignment with the ground truth and indicates that the model effectively captures the decision boundary around the 2.5 mm threshold. The tendency toward conservative predictions—favoring correct identification of Normal cases and limiting false alarms in High-Risk detection—is clinically acceptable, as it reduces unnecessary anxiety and follow-up procedures while still providing a useful automated indication of elevated risk.

Table 8.

Comparison between ground-truth labels and model predictions for NT-based risk classification.

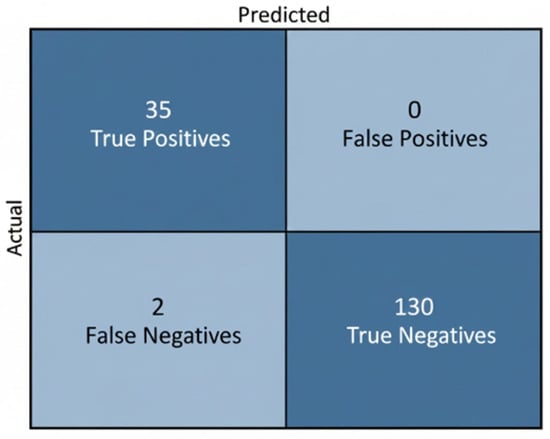

The model accurately classified most fetuses, correctly identifying 35 of 37 high-risk cases and all 130 Normal cases, with only 2 false negatives and no false positives. This conservative performance aligns with clinical expectations, minimizing unnecessary high-risk alerts while reliably supporting NT-based risk assessment. As illustrated in Figure 31.

Figure 31.

Confusion Matrix for NT-Based Risk Stratification.

5. Discussion

This study presented a two-stage deep learning framework for automated NT analysis in first-trimester ultrasound, integrating image-quality assessment and segmentation-based NT measurement with subsequent risk classification. The proposed pipeline addresses two major challenges in NT screening: variability in image acquisition quality and operator-dependent measurement inconsistency. By separating these tasks into distinct yet complementary stages, the framework improves robustness and clinical interpretability while remaining computationally efficient.

In the first stage, image-quality assessment using DenseNet121 achieved superior performance compared to other widely used convolutional neural network architectures, including VGG, ResNet, EfficientNet, and Inception variants. The achieved accuracy of 0.94 and AUC of 0.986 demonstrate that DenseNet121 effectively discriminates between standard and non-standard NT ultrasound images, even when trained on a relatively limited dataset. This result is consistent with previous findings indicating that dense feature reuse improves performance in medical imaging tasks with limited data availability. Importantly, Grad-CAM visualizations confirmed that the model consistently attended to anatomically relevant regions around the fetal neck rather than irrelevant background structures, supporting the clinical plausibility of the learned representations.

When compared with recent NT image-quality assessment approaches, including VGG16-based classifiers, Deep Content and Contrastive Perception (DCCP) models, and 3D ResNet or YOLO-based detection frameworks, the proposed method achieved competitive or superior performance while requiring fewer training samples. This highlights an important trade-off between dataset size and model complexity, suggesting that carefully selected architectures combined with interpretability analysis can reduce data dependency without compromising diagnostic reliability. A quantitative comparison with representative studies is provided in Table 9.

Table 9.

Comparison of NT image-quality assessment methods.

In the second stage, the DenseNet-based segmentation model demonstrated state-of-the-art performance on the NHOG dataset, achieving an accuracy of 0.989, Dice coefficient of 0.897, and IoU of 0.813. In contrast, the U-Net baseline, although exhibiting high specificity, suffered from markedly low recall and Dice scores, indicating limited ability to accurately delineate the thin and low-contrast NT region. These findings are in line with prior studies reporting that classical U-Net architectures may struggle with small, elongated anatomical structures in ultrasound images due to speckle noise and boundary ambiguity.

The clinical relevance of the proposed approach is further supported by the NT measurement analysis. Differences between automated and expert measurements were within clinically acceptable limits in the majority of cases, with 55.47%of measurements differing by less than 1 mm and 33.18% by less than 0.5 mm. These results compare favorably with previously reported NT measurement systems, many of which report mean absolute errors in the range of 0.3–0.6 mm. Furthermore, the risk classification based on the clinically established 2.5 mm threshold yielded a label distribution closely aligned with expert ground truth, reinforcing the suitability of the proposed framework for real-world screening scenarios.

Overall, the comparative analysis summarized in Table 10 demonstrates that the proposed two-stage framework achieves performance comparable to or exceeding that of existing methods while offering improved interpretability and reduced reliance on large annotated datasets. These characteristics are particularly valuable in clinical environments where expert sonographers or high-quality data are limited. While the results are promising, future work should focus on multi-center validation, inclusion of diverse ultrasound devices, and integration of maternal clinical parameters to further enhance generalizability and screening accuracy.

Table 10.

Comparison of NT segmentation and measurement performance.

6. Conclusions

This study proposed and validated a two-stage deep learning framework for automated NT analysis in first-trimester ultrasound, aiming to reduce operator dependency and improve the reliability of early chromosomal abnormality screening. The framework integrates image-quality assessment, NT region segmentation, automated thickness measurement, and binary risk classification in a clinically aligned workflow that mirrors routine prenatal practice.

In the first stage, DenseNet121 demonstrated strong performance for NT image-quality assessment, achieving an accuracy of 94% and an AUC of 0.986 on the Fetus Framework dataset (1684 images). These results indicate a high capability to reliably distinguish standard from non-standard mid-sagittal planes, a prerequisite for accurate NT measurement. Grad-CAM analysis further confirmed that the model’s decisions were driven by anatomically relevant regions around the fetal neck, reinforcing the interpretability and clinical plausibility of the approach.

In the second stage, the proposed DenseNet-based segmentation model achieved an overall accuracy of 98.9%, a Dice coefficient of 0.897, and an IoU of 0.813 on the NHOG dataset (741 images), clearly outperforming the baseline U-Net architecture. Automated NT measurements showed strong agreement with expert annotations, with 55.47% of cases differing by less than 1 mm and 33.18% by less than 0.5 mm, remaining well within clinically acceptable error margins reported in prior studies. Risk classification based on the established 2.5 mm threshold produced a prediction distribution closely aligned with expert ground truth, demonstrating high clinical consistency while minimizing unnecessary high-risk labeling.

Comparative analysis with existing state-of-the-art methods revealed that the proposed framework achieves performance comparable to or exceeding that of more complex or data-intensive approaches, despite being trained on smaller datasets. Importantly, the explicit integration of image-quality filtering with segmentation-based measurement distinguishes this work from many prior studies that address these tasks in isolation. This integrated design enhances robustness, interpretability, and suitability for deployment in real-world clinical environments, particularly in settings with limited expert availability.

Based on these findings, the proposed framework shows strong potential as a clinical decision-support tool for first-trimester prenatal screening.

7. Limitations and Future Work

Our study, while demonstrating a robust AI-driven framework for nuchal translucency analysis, has several limitations that offer clear directions for future research.

First, the dataset, although competitive in size for this sub-domain, is derived from only two clinical centers. This homogeneity in data sourcing spanning ultrasound hardware, acquisition protocols, and patient demographics presents a risk of overfitting and may limit the model’s generalizability. A core principle of developing robust AI is its ability to perform consistently across diverse and unseen data. Therefore, the current model’s performance on out-of-distribution data from different hospitals or patient populations remains unverified. Furthermore, our framework is confined to image-based analysis, omitting biochemical markers like PAPP-A. Integrating this multi-modal data could enrich the model’s feature space and align it more closely with established clinical screening protocols.

Second, our evaluation was conducted retrospectively. While this approach is crucial for establishing technical proof-of-concept, it cannot capture the complexities of real-world clinical application. A prospective study is the necessary next step to rigorously assess the model’s impact on diagnostic workflows, time efficiency, and its seamless integration with existing hospital information systems. Such a study is critical for translating our algorithmic success into tangible clinical value.

Third, we did not perform a direct quantitative benchmark against existing semi-automated commercial systems. Our current insights are based on qualitative observations, which suggest that full automation reduces operator-dependent variability and enhances standardization. However, a head-to-head quantitative comparison is essential to definitively establish the superiority and efficiency of our automated approach.

Future work will proceed along three primary axes. First, we will prioritize dataset expansion and diversification through multi-center collaborations, which is fundamental to improving the model’s robustness and ensuring equitable performance across different populations. Second, we plan to incorporate biochemical markers to develop a more holistic, multi-modal diagnostic model. Finally, we are actively pursuing the necessary approvals to initiate prospective clinical validation studies. These studies will not only allow for a quantitative comparison against current systems but will also provide the data needed to fine-tune the model for real-world deployment and, ultimately, facilitate its clinical translation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.O.B., A.Y.O. and M.O.; methodology, R.O.B., A.Y.O. and M.O.; software, R.O.B. and A.Y.O.; formal analysis, R.O.B. and A.Y.O.; investigation, R.O.B., A.Y.O. and M.O.; resources, R.O.B.; data curation, R.O.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.O.B. and A.Y.O.; writing—review and editing, R.O.B., A.Y.O. and M.O.; visualization, R.O.B., A.Y.O. and M.O.; project administration, A.Y.O. and M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Frist dataset was publicly available and obtained from an open source. The reader can refer to reference [52] in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NIPT | Invasive Prenatal Testing |

| CVS | Chorionic Villus Sampling |

| NT | Nuchal Translucency |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CRL | Crown–Rump Length |

| GA | Gestational Age |

| PAPP-A | Pregnancy-Associated Plasma Protein A |

| β-hCG | Beta Human Chorionic Gonadotropin |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| IQA | Image-Quality Assessment |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| TPR | True Positive Rate |

| FNR | False Negative Rate |

| FPR | False Positive Rate |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| FOR | False Omission Rate |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| BM3D | Block-Matching and 3D Filtering |

| SRAD | Speckle-Reducing Anisotropic Diffusion |

| CLAHE | Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization |

| EDA | Exploratory Data Analysis |

| OCR | Optical Character Recognition |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| U-Net | U-shaped Convolutional Neural Network |

| Grad-CAM | Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| DCCP | Deep Content and Contrastive Perception (Learning) |

| NHOG | National Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology |

| APC | Article Processing Charge |

References

- Zhytnik, L.; Simm, K.; Salumets, A.; Peters, M.; Martson, A.; Maasalu, K. Reproductive options for families at risk of Osteogenesis Imperfecta: A review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifzadeh, M.; Adibi, A.; Kazemi, K.; Hovsepian, S. Normal reference range of fetal nuchal translucency thickness in pregnant women in the first trimester, one center study. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2015, 20, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.O.; Wright, D.; Valencia, C.; Maiz, N.; Nicolaides, K.H. Screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 by maternal age, fetal nuchal translucency, fetal heart rate, free beta-hCG and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 1968–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souka, A.P.; Krampl, E.; Bakalis, S.; Heath, V.; Nicolaides, K.H. Outcome of pregnancy in chromosomally normal fetuses with increased nuchal translucency in the first trimester. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 18, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wax, J.R.; Pinette, M.G.; Cartin, A.; Blackstone, J. Optimal crown-rump length for measuring the nuchal translucency. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2007, 35, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals, E.; Aibar, C.; Martínez, J.M.; Borrell, A.; Soler, A.; Ojuel, J.; Ballesta, A.M.; Fortuny, A. First-trimester biochemical markers for Down syndrome. Prenat. Diagn. 1999, 19, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, H.; Ozyurt, S.; Aksoy, U.; Mutlu, E.; Tutus, S.; Babayigit, M.A.; Acmaz, G.; Karadag, O.I.; Yucel, B. A prospective study to assess the clinical impact of interobserver reliability of sonographic measurements of fetal nuchal translucency and crown–rump length on combined first-trimester screening. North. Clin. Istanb. 2015, 2, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, S.M.; Jun, J.K. Simplified protocol of nuchal translucency measurement: Is it still effective? Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2013, 56, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, H.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Cai, W.; Yang, P. Intelligent quality assessment of ultrasound images for fetal nuchal translucency measurement during the first trimester of pregnancy based on deep learning models. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2025, 25, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, P.P.; Altman, D.G.; Brizot, M.L.; Pettersen, H.; Nicolaides, K.H. Repeatability of measurement of fetal nuchal translucency thickness. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 5, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, H.; Hoopmann, M.; Wright, D.; Hoffmann-Poell, B.; Huettelmaier, M.; Pintoffl, K.; Wallwiener, D.; Kagan, K.O. Intra- and interoperator reliability of manual and semi-automated measurement of fetal nuchal translucency by sonographers with different levels of experience. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 36, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, M.; Zargar, M.; Masihi, S.; Taherpour, S. Evaluation of nuchal translucency measurement in first trimester pregnancy. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 5, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaides, K.H. Screening for fetal aneuploidies at 11 to 13 weeks. Prenat. Diagn. 2011, 31, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisbet, D.; Mclennan, A.; Robertson, A.; Schluter, P.J.; Hyett, J. Reducing inter-rater variability in the assessment of nuchal translucency image quality. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2011, 30, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axell, R.G.; Gillett, A.; Pasupathy, D.; Chudleigh, T.; Brockelsby, J.; White, P.A.; Lees, C.C. Accuracy of nuchal translucency measurement depends on equipment used and its calibration. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 44, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, C.; Platt, L.D. Nuchal translucency and first trimester risk assessment: A systematic review. Ultrasound Q. 2007, 23, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, F.; Cardoso, R.; Montenegro, N.; Bernardes, J.; de Sá, J.M. Semiautomated ultrasonographic measurement of fetal nuchal translucency using a computer software tool. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1998, 24, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-B.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, M.-H. Robust border enhancement and detection for measurement of fetal nuchal translucency in ultrasound images. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2007, 45, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catanzariti, E.; Fusco, G.; Isgrò, F.; Masecchia, S.; Prevete, R.; Santoro, M. A Semi-automated Method for the Measurement of the Fetal Nuchal Translucency in Ultrasound Images. In Image Analysis and Processing—ICIAP 2009; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.-H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Chen, P. Estimating Fetal Nuchal Translucency Parameters from its Ultrasound Image. In Proceedings of the 2008 2nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, Shanghai, China, 16–18 May 2008; pp. 2643–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, L.; Min, T.; Arooj, A.; Supriyanto, E. Nuchal Translucency Marker Detection Based on Artificial Neural Network and Measurement via Bidirectional Iteration Forward Propagation. WSEAS Trans. Inf. Sci. Appl. 2010, 7, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Sciortino, G.; Tegolo, D.; Valenti, C. A non-supervised approach to locate and to measure the nuchal translucency by means of wavelet analysis and neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 XXVI International Conference on Information, Communication and Automation Technologies (ICAT), Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 26–28 October 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Yu, J.; Chen, P.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.Q. Automatic measurement of fetal Nuchal translucency from three-dimensional ultrasound data. In Proceedings of the 2017 39th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 11–15 July 2017; pp. 3420–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.W.; Hum, Y.; Supriyanto, E. Computerized nuchal translucency three dimensional reconstruction, visualization and measurement for trisomy 21 prenatal early assessment. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2011, 6, 4640–4648. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Moratalla, J.; Pintoffl, K.; Minekawa, R.; Lachmann, R.; Wright, D.; Nicolaides, K.H. Semi-automated system for measurement of nuchal translucency thickness. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 36, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangé, G.; Althuser, M.; Fresson, J.; Bititi, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Tsatsaris, V.; Morel, O. Semi-automated adjusted measurement of nuchal translucency: Feasibility and reproducibility. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 37, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnaiyan, R.; Alex, S. Machine Learning Approaches for Early Diagnosis and Prediction of Fetal Abnormalities. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), Coimbatore, India, 27–29 January 2021; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, D.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Yin, C.; Poon, L.C.; Tian, J.; Wu, Q. Application of an individualized nomogram in first-trimester screening for trisomy 21. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 58, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanathan, S.; Sangeetha, M.; Talwai, S.; Natarajan, S. Probabilistic Determination of Down’s Syndrome Using Machine Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Bangalore, India, 19–22 September 2018; pp. 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, R. Down Syndrome Prediction Using a Cascaded Machine Learning Framework Designed for Imbalanced and Feature-correlated Data. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 93043–93052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, V.; Ramachandran, R. Down syndrome detection using modified adaboost algorithm. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE) 2021, 11, 4281–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Sethi, N.S.A.N.; Kamar, A.A.; Saaid, R.; Loo, C.K.; Mattar, C.N.Z.; Jalil, N.S.; Saw, S.N. Enhancing Small-for-Gestational-Age Prediction: Multi-Country Validation of Nuchal Thickness, Estimated Fetal Weight, Machine Learning Models. Prenat. Diagn. 2025, 45, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barashok, B.I.K.; Choi, Y.; Choi, Y.; Aslam, M.; Lee, J. Machine learning techniques in ultrasonics-based defect detection and material characterization: A comprehensive review. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2025, 17, 16878132251347390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Sofka, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Zhou, S.K. Automatic nuchal translucency measurement from ultrasonography. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, P. Automated detection of fetal nuchal translucency based on hierarchical structural model. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), Bentley, WA, Australia, 12–15 October 2010; pp. 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, P.; Yu, J. A hierarchical model for automatic nuchal translucency detection from ultrasound images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2012, 42, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.; Fusco, G.; Isgrò, F.; Orlandi, E.; Prevete, R.; Sciortino, G.; Tegolo, D.; Valenti, C. A system for the automatic measurement of the nuchal translucency thickness from ultrasound video stream of the foetus. In Proceedings of the 2013 26th IEEE International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), Porto, Portugal, 20–22 June 2013; pp. 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, K.; Oza, S. Ultrasound image based fully-automated nuchal translucency segmentation and thickness measurement. Int. J. Nonlinear Anal. Appl. (IJNAA) 2021, 12, 1573–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegarra, R.R.; Ghi, T. Use of artificial intelligence and deep learning in fetal ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 62, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Xu, Y.; Xu, J.; Ding, W.; Yang, J.; Zhou, H.; Du, Y.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q. Deep Content and Contrastive Perception learning for automatic fetal nuchal translucency image quality assessment. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 152, 110687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasera, B.; Shinar, S.; Edke, P.; Pruthi, V.; Goldenberg, A.; Erdman, L.; Van Mieghem, T. Deep-learning computer vision can identify increased nuchal translucency in the first trimester of pregnancy. Prenat. Diagn. 2024, 44, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhumal, Y.; Chaudhari, K.; Oza, S.; Shinde, A. The Automated Screening of Ultrasound Images for Nuchal Translucency using Auxiliary U-Net for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 15–17 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Shi, L.; Wu, S. Direct Detection and Measurement of Nuchal Translucency with Neural Networks from Ultrasound Images. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Ji, C.; Hu, X.; Cao, Y.; Chen, C.; Sui, H.; Li, B.; Zhen, C.; Huang, W.; et al. Deep Learning Model for Real-Time Nuchal Translucency Assessment at Prenatal US. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2025, 7, e240498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasrab, R.; Fu, Z.; Drukker, L.; Lee, L.H.; Zhao, H.; Papageorghiou, A.T.; Noble, J.A. End-to-end First Trimester Fetal Ultrasound Video Automated CRL and NT Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 19th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Kolkata, India, 28–31 March 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dong, D.; Sun, Y.; Hu, C.; Sun, C.; Wu, Q.; Tian, J. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Model to Screen for Trisomy 21 During the First Trimester From Nuchal Ultrasonographic Images. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2217854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshi, A.; Shafi, S.; Qayoom, I.; Wani, M.; Parveen, S.; Ahmad, A. Deep Learning-Based Architecture for Down Syndrome Assessment During Early Pregnancy Using Fetal Ultrasound Images. Int. J. Exp. Res. Rev. 2024, 38, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aher, S.; Agarkar, B.; Chaudhari, S. Deep Learning Approach for Segmenting Nuchal Translucency Region in Fetal Ultrasound Images for Detecting Down Syndrome using GoogLeNet and AlexNet. J. Electron. Electromed. Eng. Med. Inform. 2025, 7, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekdast, R. An Intelligent Method for Down Syndrome Detection in Fetuses Using Ultrasound Images and Deep Learning Neural Networks. Semantic Scholar. 2019. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:220658033 (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Lin, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, S.; Liu, X.; Peng, Q.; Huang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, C.; et al. How much can AI see in early pregnancy: A multi-center study of fetus head characterization in week 10–14 in ultrasound using deep learning. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 226, 107170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilardo, C.M.; Chaoui, R.; Hyett, J.A.; Kagan, K.O.; Karim, J.N.; Papageorghiou, A.T.; Poon, L.C.; Salomon, L.J.; Syngelaki, A.; International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology; et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines (updated): Performance of 11–14-week ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 61, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Fajin, D. Dataset for Fetus Framework. Mendeley Data 2022, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabov, K.; Foi, A.; Katkovnik, V.; Egiazarian, K. Image Denoising by Sparse 3-D Transform-Domain Collaborative Filtering. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2007, 16, 2080–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Acton, S.T. Speckle reducing anisotropic diffusion. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2002, 11, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossepoel, A.; Stoel, B.; Meershoek, A.P. Adaptive histogram equalization using variable regions. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Rome, Italy, 14 May–17 November 1988; pp. 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J.W. Exploratory Data Analysis; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Garai, S.; Paul, O.; Dey, U.; Ghoshal, S.; Biswas, N.; Mondal, S. A Novel Method for Image to Text Extraction Using Tesseract-OCR. Am. J. Electron. Commun. 2022, 3, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, L.J.; Alfirevic, Z.; Bilardo, C.M.; Chalouhi, G.E.; Ghi, T.; Kagan, K.O.; Lau, T.K.; Papageorghiou, A.T.; Raine-Fenning, N.J.; Stirnemann, J.; et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: Performance of first-trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 41, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adiego, B.; Illescas, T.; Martinez-Ten, P.; Bermejo, C.; Perez-Pedregosa, J.; Wong, A.E.; Sepulveda, W. Intracranial translucency at 11–13 weeks of gestation: Prospective evaluation and reproducibility of measurements. Prenat. Diagn. 2012, 32, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Lausanne, Switzerland, 23–25 June 2021; pp. 2261–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Ye, X.; Lu, H.; Zheng, X.; Qiu, S.; Liu, Y. Dense Convolutional Network and Its Application in Medical Image Analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 2384830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]