Abstract

Generative AI enables personalized computer science education at scale, yet questions remain about whether such personalization supports or undermines learning. This scoping review synthesizes 32 studies (2023–2025) purposively sampled from 259 records to map personalization mechanisms and effectiveness signals in higher-education CS contexts. We identify five application domains—intelligent tutoring, personalized materials, formative feedback, AI-augmented assessment, and code review—and analyze how design choices shape learning outcomes. Designs incorporating explanation-first guidance, solution withholding, graduated hint ladders, and artifact grounding (student code, tests, and rubrics) consistently show more positive learning processes than unconstrained chat interfaces. Successful implementations share four patterns: context-aware tutoring anchored in student artifacts, multi-level hint structures requiring reflection, composition with traditional CS infrastructure (autograders and rubrics), and human-in-the-loop quality assurance. We propose an exploration-firstadoption framework emphasizing piloting, instrumentation, learning-preserving defaults, and evidence-based scaling. Four recurrent risks—academic integrity, privacy, bias and equity, and over-reliance—are paired with operational mitigation. Critical evidence gaps include longitudinal effects on skill retention, comparative evaluations of guardrail designs, equity impacts at scale, and standardized replication metrics. The evidence supports generative AI as a mechanism for precision scaffolding when embedded in exploration-first, audit-ready workflows that preserve productive struggle while scaling personalized support.

1. Introduction

Providing timely, personalized support to novice programmers is a long-standing challenge in computer science education. Novice learners often encounter syntax errors or logic bugs that, without immediate intervention, can lead to frustration and disengagement. While faculties recognize the importance of individualized guidance, delivering it at scale in large introductory courses has historically been impossible due to resource constraints. Generative AI now offers a potential solution to this bottleneck, enabling context-aware assistance that can support students precisely when they are struggling.

Large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4/4o and contemporary systems like Claude and DeepSeek have moved from novelty to infrastructure in higher education [1,2,3,4]. Unlike prior rule-based adaptive systems, LLMs synthesize context-aware explanations, worked examples, and code-centric feedback on demand, making personalization feasible at the granularity of a single test failure, a syntax or logic error, or a misconception articulated in dialogue [5,6]. At the same time, GenAI has caused familiar concerns to resurface—integrity, privacy and governance, bias and equity, and over-reliance—that must be managedrather than used to justify paralysis [7,8,9,10].

- Policy context.

Institutional responses to GenAI have diverged. Some universities initially prohibited or tightly restricted student use (e.g., Sciences Po’s January 2023 ban on ChatGPT—early public release, for graded work), while others have adopted enabling, systemwide access models. In California, the California State University (CSU) system has deployed ChatGPT Edu across all 23 campuses—providing no-cost, single-sign-on access for more than 460,000 students and 63,000+ employees—and launched the CSU AI Commons to centralize training and guidance [11,12,13,14,15]. This spectrum of policy choices underscores the need for adoption guidance that is practical, evidence-seeking, and resilient to local constraints.

- What we mean by personalization.

We define personalization as the systematic adaptation of content, feedback, or task sequencing to a learner’s evolving state using observable evidence (code, tests, errors, and dialogue) [6,7]. In CS contexts this includes (i) solution-withholding programming assistants that prioritize reasoning; (ii) conversational debugging targeted to concrete error states; (iii) tailored worked examples, Parsons problems, and practice sets aligned to course context; and (iv) assessment workflows in which LLMs generate tests, rubric-aligned comments, and explanation-rich grades under human audit [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. The pedagogical aim is precision scaffolding: keeping students in productive struggle with stepwise hints, tracing, and test-driven guidance rather than answer dumps [16,21,24].

- A working definition: exploration-first.

We use exploration-firstto denote a deployment stance and workflow in which instructors and institutions pilot small instrument interactions and scale in response to evidence, with learning-preserving defaults built into tools and policies. Concretely, exploration-first means:

- Help design defaults that preserve productive struggle: Explanation-first hints (pseudocode, tracing, and fault localization), solution withholding by default, and graduated hint ladders supported by short reflection prompts before escalation.

- Artifact grounding: Tutors and feedback are conditioned on the learner’s current code, failing tests, and assignment specification; assessment is conducted with explicit rubrics and exemplars and unit tests and mutation checks.

- Human-in-the-loop audits of any generated tests, items, and grades, with logs retained for pedagogy and moderation (not “detector” policing).

- Pilot → measure → scale: Activation for one section or assignment, examining process and outcome metrics, and expanding scope when the combined quantitative and qualitative evidence supports doing so.

- Enablement governance: Vetted or enterprise instances, data minimization, and prompt and version change logs; short allow-lists in syllabi plus process evidence (what was asked, hint levels used, and test history) instead of AI detectors.

- Why a scoping review now?

Since 2023, institutions have shifted from ad hoc experimentation to exploration-first adoption: course-integrated assistants that guide rather than answer explicit but enabling policies, faculty development, and vetted tooling [8,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. The literature is expanding quickly but remains heterogeneous in tasks, measures, and outcomes; many studies are classroom deployments or mixed-method evaluations. A scoping (rather than effect-size) review is appropriate to map applications and mechanisms and surface signals of effectiveness and risk and to distill design and governance guidance instructors can use now.

- Objective and gap.

Against this backdrop, there remains a lack of integrative work that focuses specifically on GenAI-enabled personalization in higher-education computer science, systematically mapping not just use cases but the underlying mechanisms, reported outcome signals, and recurrent risks. Existing reviews and position papers typically either address AI in education in general or focus on single tools, courses, or outcome types, leaving instructors and departments without a consolidated view of how personalization is actually being implemented, under what conditions it appears to support or hinder learning, and where the evidence remains thin. The objective of this scoping review is therefore to synthesize recent empirical work to (i) characterize personalization mechanisms across application areas, (ii) identify the types of process and outcome signals that are reported, (iii) relate these mechanisms and signals to established learning-theoretic constructs, and (iv) surface gaps and design considerations that can inform both practice and future research.

- Contributions.

Focusing on 2023–2025 in higher-education CS, we contribute:

- A structured map of how GenAI is used to personalize CS learning, emphasizing mechanisms (explanation-first hints, ladders, and rubric and test grounding) over brands;

- A synthesis of effectiveness signals (time-to-help, error remediation, feedback quality, and grading reliability) and the conditions under which they appear;

- A consolidation of risks (integrity, privacy, bias and equity, and over-reliance) with actionable mitigation;

- Design principles and workflow patterns for exploration-first personalization;

- Department and institution guidance for policy, vendor vetting, and AI-aware assessment [7,8,33].

- Research questions.

- RQ1.

- Design and mechanisms: Which personalization mechanisms (explanation-first help, graduated hints, and code-aware dialogue) are most promising without short-circuiting learning? [16,17,21,24]

- RQ2.

- Effectiveness conditions: Under what pedagogical and tooling conditions do GenAI approaches improve learning processes and outcomes (and when do they fail)? [18,20,34]

- RQ3.

- Risk management: What recurrent risks accompany personalization, and what mitigation is credible in higher education? [7,9,10,33,35]

- RQ4.

- Implementation and assessment: Which workflows (test and rubric pipelines and process evidence) align personalization with durable learning and fairness? [8,22,23]

- RQ5.

- Governance and practice: How are institutions operationalizing responsible use today (policies, training, and vendor vetting), and what practical guidance follows? [8,25,27,28,29,30,32]

- RQ6.

- Evidence gaps: What longitudinal and comparative studies are needed (for example, ladder designs and equity impacts)? [8,10]

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. From ITSs to LLMs

Classic Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITSs) modeled learner knowledge and errors to deliver stepwise hints and mastery-based sequencing [36,37,38,39,40]. Later work refined knowledge tracing and data-driven adaptivity [41,42]. LLMs alter this landscape by generating context-specific explanations, examples, and code-aware feedback through natural-language dialogue [1,6,43]. The result is a different granularity of support (line-level commentary and test-oriented guidance) that can be tuned to individual misconceptions.

2.2. Clarifying Terms

We use personalization to denote continuous, evidence-driven tailoring of content, feedback, or task sequencing. Adaptation often refers to real-time adjustments (for example, difficulty and hinting) based on performance signals, whereas individualization can include preference or profile-based configuration without continuous updates [44]. Our scope emphasizes code-centric tutoring, targeted feedback, and sequenced practice that leverage generative models to produce the adapted artifacts themselves [5].

2.3. Affordances Across CS Subdomains

Introductory programming affords fine-grained interventions (syntax and logic errors, test failures, tracing), algorithms emphasize strategy explanations and worked examples, and software engineering invites feedback on design and reviews [38,45]. Productive scaffolds include explanation-first help, graduated hints, and practice items aligned to course context and learner readiness.

2.4. Pre-GenAI Baselines

Before GenAI, personalization drew on behavior and performance signals to deliver immediate feedback, difficulty adjustment, and sequencing [44,46]. Autograding pipelines, unit tests, and program analysis underpinned scalable feedback, but authored hints and items were costly to produce and maintain. Systematic reviews in programming and medical education foreshadowed GenAI’s promise and limitations [47,48,49].

2.5. GenAI-Enabled Patterns in CS Education

Recurring application patterns (2023–2025) include

- Solution-withholding assistants and debugging tutors that deliver explanation-first, context-aware hints [16,17,50,51,52].

- Personalized exemplars and practice (worked examples, Parsons problems, and course-aligned exercises) [18,19,20,53].

- Targeted formative feedback with feedback ladders and tutor-style hints [21,24,34,54,55].

- AI-augmented assessment workflows (test generation, rubric-guided grading, and MCQ and exam authoring) [22,23,56,57,58,59,60,61].

- AI-assisted code review using curated exemplars and model prompts [62,63,64,65,66].

3. Methods: Scoping Approach

We followed Arksey–O’Malley, Levac, and JBI guidance and PRISMA-ScR reporting where applicable [67,68,69,70]. Eligibility was determined according to JBI population–concept–context (PCC): population = higher-education CS learners and instructors; concept = GenAI-enabled personalization; context = higher-education CS courses and supports. The window was 2023–2025. Sources included the ACM Digital Library (SIGCSE TS, ITiCSE, ICER, TOCE), IEEE Xplore (FIE and the ICSE SEIP track), CHI, CSCW, L@S, LAK, EDM, and indexing via Google Scholar and arXiv. We ran venue-first queries, forward and backward citation chasing, and hand-searched institutional guidance (policy and governance only).

- Registration.

This scoping review was retrospectively registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF); registration details will be provided in the final version. https://osf.io/bge7y (accessed on 10 December 2025).

3.1. Eligibility and Selection

Inclusion criteria required that studies (i) took place in higher-education computer science contexts; (ii) implemented or enabled GenAI-based personalization rather than generic AI use; (iii) provided empirical evaluation (deployment, design experiment, or prototype study); (iv) were published in English between 2023 and 2025; and (v) reported sufficient methodological detail to characterize personalization mechanisms. Exclusion criteria eliminated K–12 studies, non-GenAI personalization, opinion pieces, patents, and papers lacking empirical evaluation.

Screening proceeded through title/abstract review followed by full-text assessment. Of the 259 screened records, 59 met full-text eligibility. From these, we purposively sampled 32 studies to support a mechanism-focused scoping synthesis. Purposive sampling is consistent with JBI scoping-review guidance when the goal is to map mechanisms rather than enumerate all instances. Our sampling emphasized analytic suitability rather than outcome direction.

- Rationale for purposive sampling.

A subset of full-text-eligible papers could not meaningfully contribute to mechanism mapping because they lacked operational detail, did not actually implement personalization, or reported outcomes that were uninterpretable for our analytic aims. We therefore prioritized studies that met all three of the following suitability conditions:

- (a)

- Mechanism transparency: Studies that clearly described personalization mechanisms (e.g., hint ladders, explanation-first scaffolding, course-aligned generation, or test- or rubric-grounding) were included. Papers that invoked “ChatGPT support” without detailing intervention logic were excluded.

- (b)

- Interpretable process or learning outcomes: Studies reporting measurable learning, debugging, process, or behavioral outcomes were included. Papers reporting only post hoc satisfaction surveys or generic perceptions without task-linked metrics were excluded because they could not inform mechanism–outcome relationships.

- (c)

- Sufficient intervention detail: Studies that described prompts, constraints, workflows, model grounding, or tutor policies were included. Excluded papers typically lacked enough detail to map how personalization was implemented (e.g., no description of scaffolding, no explanation of input grounding, or insufficient reporting of tasks).

- Why 27 full-text studies were excluded.

The 27 excluded papers typically exhibited one or more of the following characteristics:

- Personalization not actually implemented: The system provided static advice or open-ended chat interaction with no evidence of adaptation.

- Insufficient mechanism description: The intervention lacked detail on how hints were generated, how tasks were adapted, or how the model was conditioned.

- Outcomes limited to satisfaction surveys: No behavioral, process, or learning-related data were reported, preventing mechanism mapping.

- Redundant or superseded work: Conference abstracts or short papers from the same research groups that were expanded into more detailed publications were included.

- Negative or null results with no mechanistic insight: Some studies reported poor or null outcomes but provided too little detail to attribute failure to design, prompting, scaffolding, or grounding decisions.

- Implications for bias.

Because we prioritized mechanism-rich studies, our final corpus likely overrepresents better-specified and more mature deployments. This introduces a known selection bias toward successful or interpretable implementations. To mitigate misinterpretation, we treat outcome patterns as indicative signals rather than effectiveness estimates and emphasize throughout that the true distribution of results in the broader literature is likely more mixed.

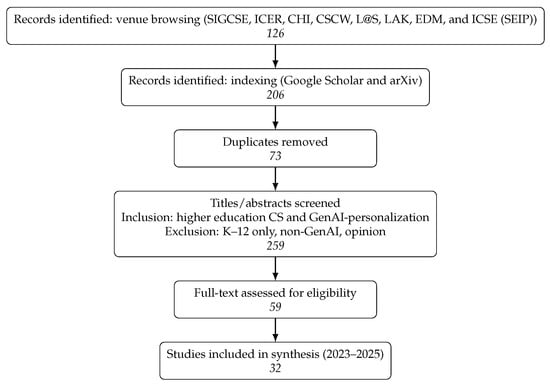

Figure 1 summarizes the screening and purposive sampling process for the included studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-style flow for the scoping review. Counts reflect purposive sampling for mechanism-rich, representative coverage.

3.2. Charting and Synthesis

We extracted bibliometrics, instructional context, model/tooling details, personalization mechanisms, implementation, evaluation design, outcomes/effectiveness signals, and risks/governance. We used a hybrid deductive–inductive synthesis, mapping to an a priori schema (tutoring, learning materials, feedback, assessment, code review, and governance) and emergent open-coding mechanisms and success/failure conditions. We did not estimate pooled effects, and—consistent with scoping aims and PRISMA-ScR guidance—we did not undertake formal methodological quality appraisal (for example, JBI tools) as our goal was to map applications and mechanisms rather than to compute aggregate effect-size estimates.

Table 1 presents a taxonomy of GenAI-enabled personalization uses in higher-education computer science, organized by application type, mechanisms, and instructional context.

Table 1.

Taxonomyof GenAI uses for personalization in higher-education CS (illustrative). Abbrev.: LLM = large language model; MCQ = multiple-choice question.

4. Results

4.1. Corpus Characteristics

Screening and purposive sampling yielded 32studies (2023–2025) implementing or enabling personalization in higher-education CS. Most appear in peer-reviewed computing education, HCI, and software engineering venues (SIGCSE, ITiCSE, ICER, CHI, L@S, LAK, EDM, and ICSE) with the remainder as detailed preprints. The modal context is CS1 and CS2 and software engineering courses, with several large-course deployments (e.g., CS50 and CS61A) [27,71].

4.2. Application Areas and Mechanisms

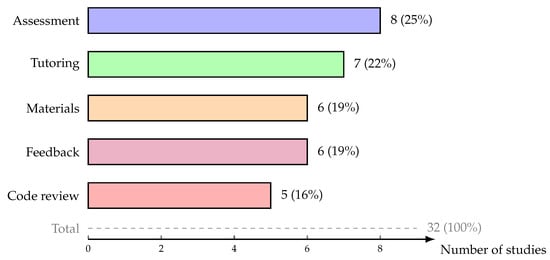

We classify studies into five non-overlapping application areas (Table 2); personalization mechanisms manifest as explanation-first tutoring and graduated hints, course-aligned generation of examples and exercises, targeted formative feedback, test- and rubric-driven assessment, and AI-assisted code review. Figure 2 visualizes the distribution of studies across these application areas.

Table 2.

Distribution of included studies by primary application area (non-overlapping).

Figure 2.

Distribution of studies by application area in the included corpus (). Colors distinguish application types for visual clarity.

4.3. Measures and Constructs

Evaluation constructs included time-to-help; error remediation (fraction of failing tests resolved and next-attempt correctness); perceived understanding and utility; feedback quality (specificity, actionability, and alignment; inter-rater ); grading reliability (QWK or adjacent agreement); test quality (statement or branch coverage, mutation score, and unique edge cases); item and exam quality (difficulty, discrimination, KR-20, or ); help-seeking behavior (hint versus solution requests and escalation); instructor and TA effort (authoring and audit time); and developer metrics in code review (precision and recall of issue detection and review acceptance). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Common evaluation constructs and typical operationalizations.

4.4. Descriptive Outcome Signals

Tutoring/assistants. Classroom deployments and observations report faster help and higher perceived understanding when assistance emphasizes explanation, pseudocode, and staged hints while withholding final solutions by default; group-aware facilitation is feasible; and unguarded chat drifts toward answer-seeking [16,17,50,51,52,89].

Personalized materials. LLM-generated worked examples and practice sets are often rated usable and helpful by novices; quality varies and benefits from instructor review; and on-demand Parsons puzzles can adapt to struggle patterns [18,19,20,53].

Targeted feedback. Structured, error-specific feedback and feedback ladders improve perceived clarity and actionability; tutor-style hints benefit from test/fix grounding and quality validation; hybrid LLM plus test feedback in MOOCs is promising; and design-oriented formative feedback is emerging [21,24,34,54,55].

Assessment. LLM-generated unit tests can increase coverage and surface edge cases and ambiguities; rubric-guided grading pipelines can approach human-level agreement when explicit rubrics and exemplars, plus calibration, are used; and MCQ and exam generation is viable with expert review and vetting workflows [22,23,56,57,58,59,60,61].

Code review. Models trained or prompted with high-quality review corpora produce more consistent, personalized critiques; industrial deployments highlight value and pitfalls; and human-in-the-loop processes remain essential [62,63,65,66].

5. Comparative Analysis: Design Patterns and Outcomes

5.1. Design Pattern Effectiveness

We coded each study by its primary design pattern and the overall outcome valence as reported by the authors (for example, positive, mixed, or negative with respect to stated goals). Recurring patterns included explanation-first, solution-withholding tutoring; graduated hint ladders; test- and rubric-grounded assessment; course-aligned generation of examples and exercises; and unconstrained chat interfaces.

Across the corpus, explanation-first and solution-withholding designs, graduated hints, and test- and rubric-grounded assessment were consistently associated with more positive reported outcomes than unconstrained chat interfaces. Unconstrained chat, especially when it routinely produced complete solutions, appeared more frequently in studies describing mixed or weaker learning benefits, concerns about over-reliance, or integrity risks.

Table 4 summarizes design patterns and high-level observations without attempting formal quantitative comparison.

Table 4.

Design patterns observed across the 32 studies and common outcome themes.

5.2. Condition Analysis

Studies reporting positive outcomes commonly share several implementation conditions:

- Artifact grounding: Tutoring and feedback anchored in students’ current code, failing tests, and assignment specifications.

- Quality assurance loops: Human review of generated tests, items, hints, or grades before or alongside student exposure.

- Graduated scaffolding: Multi-level hint structures or feedback ladders requiring reflection or effort before escalation.

- AI literacy integration: Explicit instruction on effective help-seeking, limitations of tools, and expectations around academic integrity.

Conversely, studies reporting mixed or negative outcomes often exhibit the following:

- Unconstrained access to solutions early in the interaction;

- Grading prompts without explicit rubrics or exemplar calibration;

- Limited or no instructor review of generated content;

- Weak integration with existing course infrastructure (autograders, LMS, and version control).

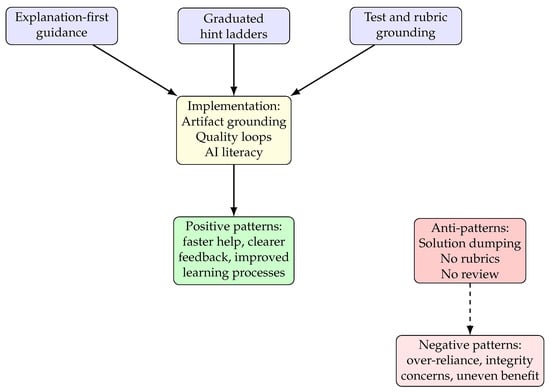

5.3. Mechanism–Outcome Mapping

Figure 3 visualizes relationships between personalization mechanisms, implementation conditions, and learning outcomes at a conceptual level.

Figure 3.

Conceptual relationships between design mechanisms, implementation conditions, and outcome patterns. Blue boxes denote design mechanisms; yellow boxes denote implementation conditions; green boxes denote patterns associated with positive learning outcomes; red boxes denote risk and negative outcome patterns. Solid arrows indicate patterns associated with positive outcomes; dashed arrows indicate patterns associated with risks and mixed outcomes.

6. Discussion

6.1. RQ1: Design Mechanisms

Four design patterns recur across the corpus. First, explanation-first, solution-withholding assistance prioritizes tracing, error localization, and pseudocode over finished answers [16,17]. Second, graduated feedback ladders escalate from strategy-level cues to line-level guidance [21,54]. Third, course-aligned generation of examples and exercises (worked examples and Parsons problems) tailors content to local curricula [18,53]. Fourth, test- and rubric-driven pipelines ground assessment and tutor-style hints in explicit specifications and criteria [22,23,24]. Anti-patterns include unconstrained chat that yields full solutions early and grading prompts without explicit rubrics and calibration.

These mechanisms are consistent with earlier work on ITSs, help-seeking, and feedback quality, where granularity of support, alignment with learner state, and clarity of criteria matter at least as much as raw system accuracy [36,38,86,88].

6.2. RQ2: Effectiveness Conditions

Improvements tend to arise under conditions that include guardrails preserving student effort (solution withholding and reflection between hint levels); tight task grounding (student code, tests, and specifications); structured evaluation artifacts (unit tests, mutation checks, and rubrics); human-in-the-loop curation (items and examples); and AI literacy plus process evidence to incentivize strategy-seeking [8,16,22,23,91].

Failure modes include answer-seeking drift, variable output quality without review, rubric-poor grading prompts, and equity risks from uneven access and over-reliance [17,20,83,84]. These conditions mirror broader findings on adaptive learning systems and persuasive technology: design choices shape not only learning outcomes but help-seeking habits and motivational dynamics [44,92,93,94].

6.3. RQ3: Risks and Mitigation

Integrity and over-reliance can be mitigated via solution withholding, oral defenses or code walkthroughs, process evidence (commit histories and prompt logs), and a mix of AI-permitted and AI-free assessments [90,91,95]. Privacy and governance are addressed via vendor vetting (retention, training use, and access controls), enterprise instances, data minimization, and consent pathways [8,33,35,96]. Bias and equity concerns are mitigated when institutions provision licensed access, review outputs for bias, accommodate multilingual learners, and avoid unreliable detectors [97,98,99,100,101]. Quality and hallucination risks are reduced by composing LLMs with tests and rubrics, calibrating prompts, and auditing outputs and versions [22,23,61].

6.4. RQ4: Workflows That Align with Durable Learning

Three workflow families stand out: (a) Tutoring: defaults to explanation-first; ladder hints; requires reflection between levels; throttles or justifies any code emission, aligning with work on help-seeking, desirable difficulties, and cognitive load [86,88,102,103]. (b) Assessment: specifications feed LLM-generated tests, followed by instructor mutation/coverage audit; rubrics guide exemplar-calibrated grading with moderation [22,23,74,75]. (c) Process-based assessment: grading design rationales, test-first thinking, and revision quality; using Viva or code reviews to assess authorship and understanding [91,95].

Operational transparency—publishing model, prompt, and policy details; logging for pedagogy and audit; and piloting before scale—supports reliability and trust [8,27,29,30,31,104,105,106,107].

6.5. RQ5: Institutional Practice

Institutions are converging on policy-backed, centrally supported adoption: AI-use statements on syllabi, faculty development, vetted tools, and privacy-preserving defaults [8,9,25,104,107]. Large-course exemplars (CS50 and CS61A) illustrate assistants that guide rather than answer and embed process-based expectations into course culture [26,27,71,90]. System-level initiatives (e.g., CSU’s ChatGPT Edu deployment and AI Commons; ASU–OpenAI partnership; HKU’s shift from temporary bans to enabling policies) highlight the importance of vendor vetting, training, and governance [12,13,14,15,108,109,110,111].

6.6. RQ6: Evidence Gaps

Priorities include longitudinal learning effects (retention, transfer, and potential de-skilling); comparative effectiveness of guardrails (ladder designs, code throttling, and reflection prompts); equity impacts at scale (stratified analyses by preparation, language, and access); and shared measures for replication (time-to-help, mutation scores, and grading agreement thresholds) [22,23,49,83,97]. Many of these needs echo earlier calls from AI-in-education and digital-education policy communities for more educator-centered, equity-aware research [7,9,10,100].

6.7. Theoretical Grounding of Findings

Having addressed our six research questions empirically, we connect our findings to established learning science principles to understand why certain design patterns succeed.

- Desirable difficulties and productive struggle.

The effectiveness of solution-withholding designs (RQ1 and RQ2) connects to desirable difficulties theory [102]: introducing challenges that require effort during learning can improve long-term retention and transfer, even when they slow initial acquisition. GenAI personalization appears most promising when it maintains challenge within the zone of proximal development [112] while reducing unproductive struggle (environment setup, obscure syntax errors, and tooling friction). Graduated hint ladders operationalize this distinction—they provide just-in-time support for unproductive obstacles while preserving the cognitive engagement needed for schema construction.

- Worked examples and fading.

The success of course-aligned worked examples and Parsons problems reflects worked-example research showing that novices learn effectively from studying solutions before generating them [113,114]. The key insight is fading: progressively reducing support as competence grows, moving from complete examples through partially-completed problems to independent practice. LLMs enable dynamic, individualized fading at finer granularity than cohort-level progressions—adapting to each learner’s demonstrated understanding rather than seat time.

- Assessment for learning.

Test-driven tutoring and rubric-guided feedback exemplify assessment for learning [115,116]: formative processes that make success criteria explicit, provide actionable feedback, and create opportunities for revision. The effectiveness of test-grounded hints and rubric-anchored grading (RQ4) aligns with the idea that transparency about expectations—paired with specific, timely guidance—supports self-regulation and improvement. GenAI amplifies this by scaling individualized feedback that would be impractical for instructors to provide manually.

- Cognitive load management.

The apparent advantages of artifact-grounded assistance (conditioned on student code, tests, and specifications) over generic tutoring align with cognitive load theory [103]: learning is optimized when extraneous load is minimized and germane load (effort building schemas) is maximized. Context-aware hints reduce the load of translating generic advice to specific code, freeing working memory for conceptual understanding. Conversely, unconstrained chat that provides complete solutions risks eliminating germane load—the very processing that drives learning.

Taken together, these connections suggest GenAI personalization is not pedagogically novel so much as a mechanism for implementing evidence-based practices at scale. The central challenge is ensuring designs preserve theoretically grounded features (desirable difficulty, graduated scaffolding, and criterion transparency) rather than optimizing for superficial metrics (task completion speed and satisfaction with solution delivery).

7. Implementation Roadmap for Departments

Based on patterns in successful deployments, we propose a phased approach to GenAI personalization adoption (Table 5). A practical instructor deployment checklist, including policy approval and communication requirements, is provided in Appendix A. The aim is not to enforce hard thresholds but to encourage routine monitoring of process and outcome metrics and structured decision-making, consistent with digital-education roadmap guidance from organizations such as EDUCAUSE, OECD, UNESCO, and the World Economic Forum [8,9,10,104,107].

Table 5.

Phased implementation roadmap for departments.

- Critical decision points.

Key decision points include (1) whether pilot data and stakeholder feedback justify continuing or adjusting the intervention; (2) whether early scaling maintains or erodes benefits; and (3) how policies and tooling should evolve as models and institutional constraints change.

- Resource requirements.

Realistic resourcing for a mid-sized CS department (10–15 faculty members, 500–800 students) may include

- Year 1 (pilot): 0.25 FTE coordinator; 20–30 h faculty training; tool licensing; 10–15 h/week pilot faculty time.

- Years 2–3 (scale): 0.5 FTE coordinator; ongoing training (5–10 h/faculty); audit processes (5–10 h/semester per tool); vendor management.

- Ongoing: Policy review; assessment validation; longitudinal studies (potentially grant-supported).

8. Limitations

- Temporal and selection bias.

Our 2023–2025 window captures early adoption; designs and models are evolving rapidly. Within this window, we purposively sampled 32 of 59 full-text-eligible studies to prioritize mechanism transparency and analytic richness. Excluded full-texts commonly relied only on student satisfaction, did not clearly implement personalization, lacked sufficient intervention detail to map mechanisms, duplicated stronger work from the same groups, or reported negative or null outcomes without actionable mechanistic insight. As a result, our synthesis emphasizes mechanism-rich, often successful deployments and may underrepresent less well-specified or unsuccessful attempts.

- Publication and outcome bias.

Negative results are underrepresented in the published literature, and combined with our focus on mechanism-rich studies, this likely leads to an optimistic skew in the available evidence. We therefore present effectiveness signals as indicative rather than definitive and caution that the true distribution of outcomes may include more mixed or negative results than the included corpus suggests.

- Quality appraisal and study design.

Many included sources are conference papers or preprints. Consistent with the aims of a scoping review and PRISMA-ScR guidance, we did not conduct formal methodological quality assessment (for example, JBI tools) and did not attempt to compute pooled effect sizes. Readers should interpret our conclusions as mapping applications, mechanisms, and reported signals rather than as a formal judgment of study quality.

- Heterogeneity in measurement.

Studies use different metrics, making cross-study comparison difficult. We therefore refrain from cross-study quantitative synthesis and instead rely on narrative descriptions of patterns in reported measures.

- Limited longitudinal data.

Most studies are single-semester deployments. Effects on long-term retention, transfer, and professional preparation remain unknown.

- Equity analysis gaps.

Few studies stratify by student demographics or prior preparation, limiting equity claims and highlighting the need for equity-focused research.

9. Future Work and Research Priorities

9.1. Critical Research Needs

- Longitudinal studies of learning and skill development.

Cohorts should be tracked over 2–4 years to assess (1) retention of concepts learned with GenAI support versus traditional instruction; (2) transfer to advanced courses and professional practice; (3) potential de-skilling effects (reduced debugging ability and over-reliance on suggestions); and (4) career outcomes (internship acquisition and workplace performance). Needed design: Multi-institutional cohort studies with matched controls and standardized assessments at graduation and 1–2 years post-graduation are required.

- Comparative effectiveness trials of guardrail designs.

Randomized controlled trials should be conducted to compare, for example, (1) hint ladder configurations (two-level vs. four-level and reflection prompts vs. time delays); (2) code throttling thresholds (no code vs. pseudocode vs. partial snippets); and (3) artifact grounding strategies (tests-only vs. tests + rubrics vs. tests + exemplars). Needed design: Within-course randomization to ladder variants, standardized outcome measures (error remediation, exam scores, debugging tasks), and replication across institutions are required.

- Equity-focused research.

Stratified analyses and participatory design studies are required. These studies should examine (1) differential effects by prior preparation (AP/IB credit and pre-college coding); (2) language background (multilingual learners and non-native English speakers); (3) disability accommodations (screen reader use, extended time, and captioning); and (4) socioeconomic factors (device access and connectivity). Needed design: Purposive oversampling of underrepresented groups, mixed methods combining analytics with interviews, and co-design of tools and policies with students are required [83,97,100].

- Standardized benchmarks and shared datasets.

Community development of (1) benchmark problem sets for tutoring (diverse difficulty, languages, error types); (2) grading rubrics and exemplar sets for assessment studies; and (3) consensus metrics (definitions of time-to-help, error remediation, feedback quality) must be carried out. Needed infrastructure: Multi-institutional working groups, open repositories (public GitHub repositories and the Open Science Framework (OSF)), and annual benchmark efforts are required.

- Open-source tool development.

Community-maintained alternatives to commercial tools should be employed: (1) solution-withholding assistants integrated with popular IDEs (VS Code, PyCharm); (2) rubric-guided grading frameworks for common LMS platforms (Canvas and Moodle); and (3) test generation pipelines with mutation-driven quality checks. Needed investment: Funding for sustainable development, documentation, and support is required.

9.2. Practice Innovations

- Process-based assessment portfolios.

Courses that assess (1) evolution of prompts (from solution-seeking to strategy-seeking); (2) test-first and revision practices logged in version control; and (3) oral defenses or code walkthroughs demonstrating understanding are key. Implementation: Rubrics for process quality, LMS integrations for log capture, and training for faculty on portfolio grading should be developed.

- Multi-institution collaboratives.

Consortia sharing: (1) vetted prompts and system configurations; (2) audit workflows and quality metrics; (3) assessment items and rubrics; and (4) case studies of policy implementation and incidents should be employed. Examples: SIGCSE committee work on GenAI in CS education and regional collaboratives.

- Student co-design and AI literacy curricula.

Participatory design processes engaging students in (1) defining help-seeking norms and tool features; (2) developing peer-to-peer AI literacy workshops; and (3) analyzing their own usage patterns and reflecting on learning strategies should be employed. Models: User research methods adapted to CS education contexts and credit-bearing seminars on AI-augmented learning are required.

9.3. Policy and Governance Research

- Vendor vetting and contract negotiation.

Empirical studies of (1) actual data practices versus vendor claims (audits and breach disclosures); (2) effectiveness of DPAs and BAAs in protecting student privacy; and (3) lock-in effects and migration costs should be conducted. Needed: Institutional data, legal expertise, and partnership with privacy organizations (FPF, EFF, and CDT) are required [33,35,96].

- Labor and instructor impact.

Investigations of (1) changes in instructor workload (time saved on grading vs. time spent on tool management and audit); (2) deskilling concerns (TAs losing grading experience and faculty losing assessment design practice); and (3) power dynamics (algorithmic management of teaching and surveillance of instructors) should be carried out. Methods: Labor study approaches, critical pedagogy frameworks, and ethnography must be employed.

- Long-term institutional case studies.

Multi-year documentation of GenAI personalization adoption at diverse institutions should be developed: (1) policy evolution (from prohibition to enablement to normalization); (2) infrastructure development (procurement, support, and training); and (3) cultural change (faculty attitudes and student expectations). Design: Longitudinal ethnography, document analysis, and interviews with administrators and faculty are required.

10. Conclusions

GenAI can deliver precision scaffolding in CS education—faster help, clearer targeted feedback, and scalable assessment support—when designs emphasize explanation-first tutoring, graduated hints, and test- and rubric-driven workflows under human oversight. Unconstrained, solution-forward use risks eroding learning and exacerbating integrity and equity issues. An exploration-first stance—clear goals, enabling policies, vetted tools, and routine audits—aligns personalization with durable learning and fairness [8,16,22,23].

- Actionable takeaways.

- Design for productive struggle: Default to solution withholding and laddered hints; require reflection between hint levels [16,54,102,113].

- Ground feedback in artifacts: Anchor guidance in student code, tests, and specifications; compose LLMs with unit tests and rubrics [21,22,24,74].

- Assess the process: Grade design rationales, prompt logs, and oral defenses; avoid reliance on AI detectors [91,95,98,99].

- Institutionalize enablement: Provide licensed tools, vendor vetting, privacy-by-design defaults, and faculty/TA training [8,29,30,31,33,104,106].

- Monitor equity: Provision access for all students; audit outputs for bias; study heterogeneous impacts [83,97,100,107].

- Build the evidence: Invest in longitudinal and comparative studies with shared metrics [10,22,23,49].

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2524227.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Deployment Checklist for Instructors

Appendix A.1. Before Deployment

- ☐

- Policy approved by department and communicated to students;

- ☐

- Vendor FERPA/GDPR compliance audit completed;

- ☐

- Faculty training conducted (tool features, pedagogical strategies, and risk mitigation);

- ☐

- Baseline data collection planned (control sections or pre-deployment metrics);

- ☐

- Human-in-the-loop audit workflow defined (who reviews what, when, and how);

- ☐

- Syllabus updated with AI-use statement (allowed tools, permitted uses, and citation requirements);

- ☐

- Student AI literacy session scheduled (effective help-seeking, tool limitations, and academic integrity).

Appendix A.2. During Pilot (Weekly/Bi-Weekly)

- ☐

- Interaction logs reviewed for answer-seeking patterns and over-reliance signals;

- ☐

- Student feedback collected (weeks 3, 8, 15: utility, clarity, and concerns);

- ☐

- Quality spot-checks (sample generated hints, grades, or tests; verify accuracy and alignment);

- ☐

- Equity monitoring (compare usage and outcomes by subgroup where feasible; investigate disparities);

- ☐

- Incident log maintained (errors, hallucinations, inappropriate outputs, and student complaints).

Appendix A.3. Evaluation at End of Pilot

- ☐

- Key process metrics (e.g., time-to-help, hint usage, and grading agreement) summarized and interpreted;

- ☐

- Evidence of meaningful error remediation and/or improved feedback quality relative to baseline;

- ☐

- Grading and test-generation workflows checked for reliability and alignment with rubrics and specifications;

- ☐

- No major equity concerns identified in stratified analyses (where data permits);

- ☐

- Faculty and student feedback indicates that benefits outweigh burdens or risks.

Appendix A.4. Decision Point

- ☐

- If evidence is broadly positive, consider scaling to additional sections or courses with ongoing monitoring;

- ☐

- If evidence is mixed, diagnose causes (tool design, instructor preparation, and task alignment), refine, and re-pilot;

- ☐

- If major risks are identified, pause or discontinue use pending remediation; document lessons learned.

Appendix A.5. Ongoing (Post-Scale)

- ☐

- Periodic review of usage, outcome, and equity metrics;

- ☐

- Annual policy review (update for new use cases, model changes, and regulatory shifts);

- ☐

- Vendor re-evaluation (privacy practices, pricing, feature roadmap, and lock-in risks);

- ☐

- Longitudinal follow-up where feasible (e.g., retention, transfer, and downstream course performance);

- ☐

- Community contribution (share practices, prompts, and lessons via conferences or repositories).

References

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Hello GPT-4o. 2024. Available online: https://openai.com/index/hello-gpt-4o/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Anthropic. The Claude 3 Model Family: Opus, Sonnet, Haiku (Model Card). 2024. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/claude-3-model-card (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- DeepSeek-AI; Guo, D.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, P. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Liang, J.; Tang, J.; Yu, P.S.; Wen, Q. Large Language Models for Education: A Survey and Outlook. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.18105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Gan, W.; Qi, Z.; Wu, J.; Yu, P.S. Large Language Models for Education: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Technology. Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Teaching and Learning: Insights and Recommendations; U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- EDUCAUSE. 2024 EDUCAUSE AI Landscape Study; EDUCAUSE: Boulder, CO, USA, 2024; Available online: https://library.educause.edu/resources/2024/2/2024-educause-ai-landscape-study (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- UNESCO. Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/guidance-generative-ai-education-and-research (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- OECD. OECD Digital Education Outlook 2023: Towards an Effective Digital Education Ecosystem; Technical Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters. Top French University Bans Use of ChatGPT to Prevent Plagiarism; Reuters: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.reuters.com/technology/top-french-university-bans-use-chatgpt-prevent-plagiarism-2023-01-27/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- California State University. CSU Prepares Students, Faculty and Staff for an AI-Driven Future; California State University: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.calstate.edu/csu-system/news/Pages/CSU-Prepares-Students-Employees-for-AI-Driven-Future.aspx (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- California State University; Northridge. ChatGPT Edu for Students & Faculty. 2025. Available online: https://www.csun.edu/it/software-services/chatgpt (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- California State University; San Bernardino. CSUSB ChatGPT Edu. 2025. Available online: https://www.csusb.edu/faculty-center-for-excellence/instructional-design-and-academic-technologies-idat/chatgpt (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Kelly, R. California State University Launches Systemwide ChatGPT Edu Deployment. Campus Technology, 2 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemitabaar, M.; Ye, R.; Wang, X.; Henley, A.Z.; Denny, P.; Craig, M.; Grossman, T. CodeAid: Evaluating a Classroom Deployment of an LLM-based Programming Assistant that Avoids Revealing Solutions. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, H.; Xu, Y.; Brennan, K.; Schneider, B. Debugging with an AI Tutor: Investigating Novice Help-Seeking Behaviors and Perceived Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research (ICER), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 13–15 August 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jury, B.; Lorusso, A.; Leinonen, J.; Denny, P.; Luxton-Reilly, A. Evaluating LLM-generated Worked Examples in an Introductory Programming Course. In Proceedings of the ACE 2024: Australian Computing Education Conference, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 29 January–2 February 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Carpio Gutierrez, A.; Denny, P.; Luxton-Reilly, A. Automating Personalized Parsons Problems with Customized Contexts and Concepts. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education (ITiCSE 2024); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logacheva, E.; Hellas, A.; Prather, J.; Sarsa, S.; Leinonen, J. Evaluating Contextually Personalized Programming Exercises Created with Generative AI. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research (ICER), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 13–15 August 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Jansen, T.; Schiller, R.; Liebenow, L.W.; Steinbach, M.; Horbach, A.; Fleckenstein, J. Using LLMs to Bring Evidence-Based Feedback into the Classroom: AI-generated Feedback Increases Secondary Students’ Text Revision, Motivation, and Positive Emotions. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkafaween, U.; Albluwi, I.; Denny, P. Automating Autograding: Large Language Models as Test Suite Generators for Introductory Programming. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.09261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Niu, J.; Xue, C.J.; Guan, N. Grade Like a Human: Rethinking Automated Assessment with Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.19694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, T.; Pădurean, V.A.; Singh, A.; Brooks, C.; Cambronero, J.; Gulwani, S.; Singla, A.; Soares, G. Automating Human Tutor-Style Programming Feedback: Leveraging GPT-4 Tutor Model for Hint Generation and GPT-3.5 Student Model for Hint Validation. In Proceedings of the 14th Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference (LAK 2024), Kyoto, Japan, 18–22 March 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tyton Partners. Time for Class 2024: Unlocking Access to Effective Digital Teaching and Learning; Report; Tyton Partners: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- The Harvard Crimson. CS50 Will Integrate Artificial Intelligence into Course Instruction; The Harvard Crimson: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Zenke, C.; Liu, C.; Holmes, A.; Thornton, P.; Malan, D.J. Teaching CS50 with AI: Leveraging Generative Artificial Intelligence for Scaffolding and Feedback. In Proceedings of the 55th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE), Portland, OR, USA, 20–23 March 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford Teaching Commons. Artificial Intelligence Teaching Guide; Stanford Teaching Commons: Stanford, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- MIT Teaching + Learning Lab. Generative AI & Your Course. Available online: https://tll.mit.edu/teaching-resources/course-design/gen-ai-your-course/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Penn Center for Excellence in Teaching, Learning, & Innovation. Generative AI & Your Teaching. Available online: https://cetli.upenn.edu/resources/generative-ai/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- University of Pennsylvania, Center for Excellence in Teaching, Learning, & Innovation (CETLI). Penn AI Guidance and Policies. Available online: https://ai.upenn.edu/guidance (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Duke Learning Innovation & Lifetime Education. Generative AI and Teaching at Duke: Guidance for Instructors; Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Future of Privacy Forum. Vetting Generative AI Tools for Use in Schools. 2024. Available online: https://fpf.org/ (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Gabbay, H.; Cohen, A. Combining LLM-Generated and Test-Based Feedback in a MOOC for Programming. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale (L@S 2024), Atlanta, GA, USA, 18–20 July 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIT RAISE. Securing Student Data in the Age of Generative AI; Report; MIT RAISE: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, J.R. AI in CAI: An Artificial-Intelligence Approach to Computer-Assisted Instruction. IEEE Trans. Man–Mach. Syst. 1970, 11, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleeman, D.; Brown, J.S. (Eds.) Intelligent Tutoring Systems; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, B.P. Building Intelligent Interactive Tutors: Student-Centered Strategies for Revolutionizing E-Learning; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nwana, H.S. Intelligent Tutoring Systems: An Overview. Artif. Intell. Rev. 1990, 4, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.T.; Anderson, J.R. Knowledge Tracing: Modeling the Acquisition of Procedural Knowledge. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 1994, 4, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piech, C.; Bassen, J.; Huang, J.; Ganguli, S.; Sahami, M.; Guibas, L.J.; Sohl-Dickstein, J. Deep Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pelánek, R. Bayesian Knowledge Tracing, Logistic Models, and Beyond: An Overview of Learner Modeling Techniques. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2017, 27, 313–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E. ChatGPT for Good? On Opportunities and Challenges of Large Language Models for Education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, D.; Berges, M.; Chugh, A.; Striewe, M. Adaptive Learning Systems in Programming Education. In Proceedings of the GI Software Engineering/Informatics Education (DELFI 2024), Linz, Austria, 26 February–1 March 2024; Lecture Notes in Informatics (LNI), Gesellschaft für Informatik: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ishaq, K.; Alvi, A.; Ikram ul Haq, M.; Rosdi, F.; Nazeer Choudhry, A.; Anjum, A.; Ali Khan, F. Level up your coding: A systematic review of personalized, cognitive, and gamified learning in programming education. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwan, S.; Gao, G.; Fisk, S.R.; Price, T.W.; Barnes, T. Adaptive Immediate Feedback Can Improve Novice Programming Engagement and Intention to Persist in Computer Science. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Computing Education Research Conference (ICER ’20), Virtual Event, 10–12 August 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, A.P.; Barbosa, A.; Carvalho, R.; Freitas, F.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Gašević, D.; Mello, R.F. Automatic Feedback in Online Learning Environments: A Systematic Review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, H.C.; Upperman, J.S.; Robinson, J.R. A systematic review of large language models and their impact in medical education. Med. Educ. 2024, 58, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Marín, V.I.; Bond, M.; Gouverneur, F. Systematic Review of Research on Artificial Intelligence Applications in Higher Education—Where Are the Educators? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2019, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassner, P.; Frankford, E.; Krusche, S. Iris: An AI-Driven Virtual Tutor for Computer Science Education. In Proceedings of the ITiCSE 2024, Milan, Italy, 8–10 July 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zamfirescu-Pereira, J.D.; DeNero, J. Scalable Small-Group CS Tutoring System with AI. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.17007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestin, G.; Miller, K.; Klales, A.; Milbourne, T.; Ponti, G. AI tutoring outperforms in-class active learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Ericson, B.J. CodeTailor: LLM-Powered Personalized Parsons Puzzles for Engaging Support While Learning Programming. In Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale (L@S ’24), Atlanta, GA, USA, 18–20 July 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heickal, H.; Lan, A.S. Generating Feedback-Ladders for Logical Errors in Programming Assignments Using GPT-4. In Proceedings of the Educational Data Mining 2024 (Posters), Atlanta, GA, USA, 11–13 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, E.; Teja, S.; Coombes, C.; Patterson, D. FEED-BOT: Formative Design Feedback on Programming Assignments. In Proceedings of the ITiCSE 2025, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 27 June–2 July 2025; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, J.; Wan, Z.; Bompelli, A.; Qayum, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Doyle, A.; Sridhar, P.; Agarwal, A.; et al. A Comparative Study of AI-Generated (GPT-4) and Human-crafted MCQs in Programming Education. In Proceedings of the 55th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE Companion), Portland, OR, USA, 20–23 March 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelka, J.; Agarwal, A.; Bogart, C.; Sakr, M. From GPT-3 to GPT-4: On the Evolving Efficacy of Large Language Models to Answer Multiple-Choice Questions for Programming Classes in Higher Education. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.09518. [Google Scholar]

- Isley, C.; Gilbert, J.; Kassos, E.; Kocher, M.; Nie, A.; Brunskill, E.; Domingue, B.; Hofman, J.; Legewie, J.; Svoronos, T.; et al. Assessing the Quality of AI-Generated Exams: A Large-Scale Field Study. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.08314. [Google Scholar]

- Impey, C.; Wenger, M.; Garuda, N.; Golchin, S.; Stamer, S. Using Large Language Models for Automated Grading of Essays and Feedback Generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.18719. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef, M.; Mohamed, K.; Medhat, W.; Mohamed, E.H.; Khoriba, G.; Arafa, T. BeGrading: Large Language Models for Enhanced Feedback in Programming Education. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 37, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggioli, A.; Casaburi, G.; Ercolani, L.; Collova’, F.; Torre, P.; Davide, F. Assessing the Reliability and Validity of Large Language Models for Automated Assessment of Student Essays in Higher Education. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.02442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Thongtanunam, P.; Treude, C.; Charoenwet, W.P. Improving Automated Code Reviews: Learning from Experience. In Proceedings of the 21st IEEE/ACM International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR 2024), Lisbon, Portugal, 14–20 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, Y.; Gomes, A.A.R.; Dantas, E.; Muniz, F.; de Farias Santos, K.; Perkusich, M.; Almeida, H.; Perkusich, A. AICodeReview: Advancing Code Quality with AI-Enhanced Reviews. SoftwareX 2024, 26, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Erickson, S.; Waldvogel, T.; Brown, K.M. The CS1 Reviewer App: Choose Your Own Adventure or Learn by Repetition? In Proceedings of the ACM ITiCSE, Virtual, 26 June–1 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cihan, U.; Haratian, V.; İçöz, A.; Gül, M.K.; Devran, Ö.; Bayendur, E.F.; Uçar, B.M.; Tüzün, E. Automated Code Review in Practice: Experience from Deploying and Improving an LLM-based PR Agent at Scale. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.18531. [Google Scholar]

- Cihan, U.; İçöz, A.; Haratian, V.; Tüzün, E. Evaluating Large Language Models for Code Review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.20206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamfirescu-Pereira, J.; Qi, L.; Hartmann, B.; DeNero, J.; Norouzi, N. 61A Bot Report: AI Assistants in CS1 Save Students Homework Time and Reduce Demands on Staff. (Now What?). arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.05600v3. [Google Scholar]

- Burstein, J.; Chodorow, M.; Leacock, C. Automated Essay Evaluation: The Criterion Online Writing Service. AI Mag. 2004, 25, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Education. 2013 Audit III Report: Scoring of the FCAT 2.0 Writing Assessment. 2013. Available online: https://www.fldoe.org/core/fileparse.php/3/urlt/2013burosreportfcatwritingassessment.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Pizzorno, J.A.; Berger, E.D. CoverUp: Coverage-Guided LLM-Based Test Generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.16218. [Google Scholar]

- Broide, L.; Stern, R. EvoGPT: Enhancing Test Suite Robustness via LLM-Based Generation and Genetic Optimization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.12424. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Tian, H.; Pian, W.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Klein, J.; Bissyandé, T.F.; Jin, S. CREF: An LLM-Based Conversational Software Repair Framework. In Proceedings of the ISSTA 2024, Vienna, Austria, 16–20 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Venugopalan, D.; Yan, Z.; Borchers, C.; Lin, J.; Aleven, V. Combining Large Language Models with Tutoring System Intelligence: A Case Study in Caregiver Homework Support. In Proceedings of the LAK 2025, Dublin, Ireland, 3–7 March 2025; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. Response Times: The 3 Important Limits. 1993. Updated by Nielsen Norman Group. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/response-times-3-important-limits/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Akoglu, L.; de Mel, G. Analysis of Question Response Time in StackOverflow. In Proceedings of the ASONAM 2014, Beijing, China, 17–20 August 2014; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Piazza. Fall Usage Data Far Exceeds Expectations. 2011. Available online: https://piazza.com/about/press/20120106.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- LuPLab, UC Davis. Piazza Statistics: Response Time vs Class Size. 2021. Available online: https://luplab.cs.ucdavis.edu/2021/03/16/piazza-statistics.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Washington, T., II; Bardolph, M.; Hadjipieris, P.; Ghanbari, S.; Hargis, J. Today’s Discussion Boards: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Online J. New Horizons Educ. 2019, 9, 222–230. [Google Scholar]

- Prather, J.; Reeves, B.N.; Leinonen, J.; MacNeil, S.; Randrianasolo, A.S.; Becker, B.A.; Kimmel, B.; Wright, J.; Briggs, B. The Widening Gap: The Benefits and Harms of Generative AI for Novice Programmers. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research (ICER 2024), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 13–15 August 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zviel-Girshin, R.; Terk-Baruch, M.; Shvartzman, E.; Shonfeld, M. Generative AI in Novice Programming Education: Opportunities and Challenges. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. A Quarter of U.S. Teachers Say AI Tools Do More Harm Than Good in K–12 Education. Survey report; Pew Research Center, 2024. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Price, T.W.; Dong, Y.; Roy, R.; Barnes, T. The Effect of Hint Quality on Help-Seeking Behavior. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2017), Wuhan, China, 28 June–1 July 2017; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 312–323. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roll, I.; Aleven, V.; McLaren, B.M.; Koedinger, K.R. The Help Tutor: Does Metacognitive Feedback Improve Students’ Help-Seeking Actions, Skills and Learning? In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS 2006), Jhongli, Taiwan, 26–30 June 2006; Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 4053. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 360–369. [Google Scholar]

- Rahe, C.; Maalej, W. How Do Programming Students Use Generative AI? In Proceedings of the ACM Joint Meeting on Foundations of Software Engineering (FSE 2025), Trondheim, Norway, 23–27 June 2025; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard University. CS50 Will Use Artificial Intelligence to Help Students Learn; University news announcement; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA). Reconsidering Assessment for the ChatGPT Era; Guidance report; QAA: Gloucester, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fogg, B.J. Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jisc National Centre for AI. Embracing Generative AI in Assessments: A Guided Flowchart; Guidance document; Jisc: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Future of Privacy Forum. Generative AI in Higher Education: Considerations for Privacy and Data Governance; Policy report; Future of Privacy Forum: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. The Potential Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Equity and Inclusion in Education; Technical report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. New AI Classifier for Indicating AI-Written Text (Notice of Discontinuation); Announcement; OpenAI: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.; Yuksekgonul, M.; Mao, Y.; Wu, E.; Zou, J. GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers. Patterns 2023, 4, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.S.; Hawn, A. Algorithmic Bias in Education. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2022, 32, 901–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Algorithmic Bias: The State of the Situation and Policy Recommendations. In OECD Digital Education Outlook 2023; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork, E.L.; Bjork, R.A. Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In Psychology and the Real World: Essays Illustrating Fundamental Contributions to Society; Gernsbacher, M.A., Pew, R.W., Hough, L.M., Pomerantz, J.R., Eds.; Worth Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDUCAUSE. 2024 EDUCAUSE Action Plan: AI Policies and Guidelines; Report; EDUCAUSE: Louisville, CO, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford Center for Teaching and Learning. Teaching with AI: Guidelines, Policies, and Recommendations; Instructional guidance; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Duke Learning Innovation. Generative AI Guidance for Instructors; Instructional guidance; Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Shaping the Future of Learning: The Role of AI in Education; Policy report; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sciences Po. Sciences Po Bans the Use of ChatGPT Without Transparent Referencing. Institutional Announcement; Sciences Po, 2023. Available online: https://newsroom.sciencespo.fr/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- University of Hong Kong. HKU Temporarily Bans Students from Using ChatGPT; University announcement; University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- University of Hong Kong. HKU Drops Ban and Provides Generative AI Tools Campus-Wide; University announcement; University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arizona State University. ASU–OpenAI Partnership (ChatGPT for Education/Enterprise) Announcement; Press release; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Cole, M., John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sweller, J.; Cooper, G.A. The use of worked examples as a substitute for problem solving in learning algebra. Cogn. Instr. 1985, 2, 59–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkl, A.; Atkinson, R.K.; Maier, U.H.; Staley, R. From example study to problem solving: Smooth transitions help learning. J. Exp. Educ. 2002, 70, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, P.; Wiliam, D. Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 1998, 5, 7–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, D.R. Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instr. Sci. 1989, 18, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.