Abstract

Real-world decision-making often involves uncertainty, incomplete data, and the need to evaluate alternatives based on both quantitative and qualitative criteria. To address these challenges, this study presents FAS-XAI, a unified methodological framework that integrates fuzzy clustering and explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). FAS-XAI supports interpretable, data-driven decision-making by combining three key components: fuzzy clustering to uncover latent behavioral profiles under ambiguity, supervised prediction models to estimate decision outcomes, and expert-guided interpretation to contextualize results and enhance transparency. The framework ensures both global and local interpretability through SHAP, LIME, and ELI5, placing human reasoning and transparency at the center of intelligent decision systems. To demonstrate its applicability, FAS-XAI is applied to a real-world B2B customer service dataset from a global ERP software distributor. Customer engagement is modeled using the RFID approach (Recency, Frequency, Importance, Duration), with Fuzzy C-Means employed to identify overlapping customer profiles and XGBoost models predicting attrition risk with explainable outputs. This case study illustrates the coherence, interpretability, and operational value of the FAS-XAI methodology in managing customer relationships and supporting strategic decision-making. Finally, the study reflects additional applications across education, physics, and industry, positioning FAS-XAI as a general-purpose, human-centered framework for transparent, explainable, and adaptive decision-making across domains.

1. Introduction

Decision-making in real-world environments is increasingly shaped by complex, uncertain, and multidimensional data. Traditional analytical models often assume precise inputs, crisp classifications, and fully observable conditions, assumptions that are rarely held in domains such as business intelligence, industrial processes, education, or scientific experimentation. In contrast, real-world scenarios frequently involve noisy data, latent structures, subjective assessments, and a need to balance both interpretability and predictive power.

In recent years, the integration of Fuzzy logic and Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) has emerged as a promising path toward enhancing transparency while preserving analytical robustness [1]. However, most contributions remain domain-specific or focus on isolated components, either using fuzzy methods for unsupervised profiling or applying XAI solely to explain supervised predictions. This fragmentation limits the ability to construct comprehensive pipelines that support end-to-end strategic decisions under uncertainty.

To address this gap, we introduce FAS-XAI, a unified methodological framework that combines Fuzzy clustering, interpretable machine learning, and multi-criteria strategic scoring (e.g., via AHP or fuzzy linguistic models). FAS-XAI provides a structured, modular approach for identifying latent profiles, predicting key outcomes, and ranking alternatives based on expert knowledge. One of the key contributions of this framework lies in its dual-layered use of XAI: first, to interpret the degree of membership of data points in fuzzy clusters, revealing which features contribute most to their positioning within overlapping segments; second, to explain the outputs of supervised models (e.g., XGBoost) used for outcome prediction, such as churn detection, using agnostic techniques like SHAP, LIME, PDP and ELI5 [2]. This dual application ensures interpretability throughout the entire decision pipeline, from unsupervised pattern discovery to predictive analytics.

To demonstrate its applicability, we implement FAS-XAI on a real-world dataset from a global ERP software distributor. Customer interactions are modeled using the RFID approach (Recency, Frequency, Importance, Duration), enabling a multidimensional view of engagement. Fuzzy C-Means clustering is used to identify customer segments with soft membership, and XAI techniques are applied at both the clustering and prediction levels to uncover actionable insights. Given the confidentiality of B2B ERP partner ecosystems, industry-wide churn or retention metrics are not publicly available, so the emphasis of this study is placed on the methodological contribution of FAS-XAI.

Beyond this case, the proposed framework builds upon prior methodological developments in explainable decision-support systems and fuzzy–XAI integration [3,4]. In parallel, related work in the broader literature has shown that fuzzy and explainable models can be effectively applied across diverse domains, including education, physics, and industrial quality control. By consolidating these methodological strands, the present study provides a unified reference model for transparent, human-centered, and strategically guided decision-making.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on fuzzy modeling, interpretability, and decision support. Section 3 details the components of the FAS-XAI framework. Section 4 presents the case study based on the RFID model. Section 5 discusses cross-domain applications, reflects on the contributions of the framework, and outlines future directions. Finally, Section 6 provides the conclusions of the article.

2. Related Work

In this section, we present a structured review of the literature to explore the extent to which the components of the FAS-XAI framework—fuzzy clustering, explainable machine learning, and strategic decision modeling—have been studied together or in isolation. Our aim is not only to summarize existing methods, but also to critically investigate whether the methodological integration we propose here has been developed or applied previously.

To this end, we organize the review around four main thematic areas. First, we explore the use of fuzzy clustering techniques, particularly their role in profiling and segmentation tasks under conditions of uncertainty and data overlap. Second, we examine the field of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI), with a focus on how interpretability is being integrated into machine learning models to enhance transparency and trust. Third, we investigate studies that attempt to combine fuzzy clustering with XAI techniques, assessing whether these tools have been integrated into a coherent and structured decision-making process. Finally, we analyze applications in customer service and business decision support domains, where interpretable and adaptive models are especially valuable, to evaluate the extent to which multi-layered pipelines like FAS-XAI have been considered or implemented in practice.

This literature review is guided by a series of systematic searches conducted in the Web of Science (WoS) database, using carefully selected keywords for each thematic block. Through this approach, we seek to position the FAS-XAI framework not only as a novel contribution in terms of implementation, but as a response to a methodological gap in current scientific and applied research.

2.1. Fuzzy Clustering

In recent years, fuzzy clustering has gained significant traction as a flexible and powerful tool for segmenting complex systems characterized by overlapping group structures and uncertainty. Unlike traditional clustering methods, fuzzy clustering assigns each data point of a degree of membership to multiple clusters, enabling a more nuanced understanding of human behavior, system states, or customer profiles [5].

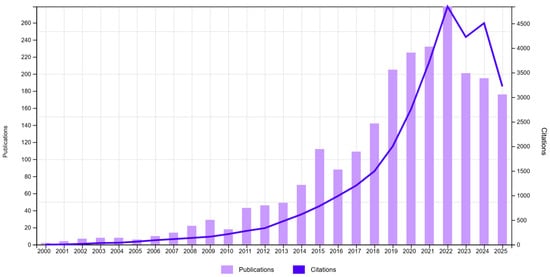

A preliminary search in the Web of Science (WoS) database using the query TS = (“FUZZY C-MEANS”) AND TS = (“CLUSTERING”) returned over 2300 publications and nearly 29,000 citations between 2000 and 2025, showing a clear upward trend in scientific interest. As illustrated in Figure 1, the number of related publications has grown steadily, with a significant increase from 2018 onward, peaking in 2020-2023. This reflects the consolidation of fuzzy clustering as a central technique in domains requiring flexible reasoning, such as healthcare, image recognition, customer segmentation, and fault detection.

Figure 1.

WoS. Publications (2300) and citations (29,040). TS = (“FUZZY C-MEANS”) AND TS = (“CLUSTERING”).

Despite its growing use, most implementations of Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) remain confined to exploratory segmentation or visualization purposes [6,7,8,9]. That is, clusters are used to describe profiles, but not as foundations for predictive modeling or dynamic decision-making systems. Furthermore, interpretability of the clustering results, why an instance partially belongs to a cluster or what variables drive cluster formation, is rarely analyzed explicitly.

Another underexplored angle is the predictive fidelity across clusters. While some fuzzy clusters may lead to stable and accurate predictions, others may reflect noisier or more volatile subpopulations. Yet, few studies measure predictive performance per cluster, missing the opportunity to identify which profiles are more reliably modeled.

These limitations call for an integrated approach where fuzzy segmentation is not an endpoint, but rather the starting point of a broader explainable and strategic pipeline. In the next sections, we explore how such integration can be enhanced through the adoption of explainable AI models and their application to high-stakes environments such as customer service.

2.2. Explainable AI (XAI)

In parallel with the rise of high-performance machine learning models, there has been growing concern about the interpretability and transparency of algorithmic decisions. The development of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) responds to this need, especially in contexts where decisions must be auditable, ethically sound, and aligned with human reasoning [10,11].

XAI encompasses a variety of techniques aimed at making the inner workings of black-box models more transparent. Some of the most widely adopted methods include SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [12], LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations) [13], and ELI5 [14], among others. These tools allow practitioners to understand which features influence the predictions, how they do so, and to what extent, thus bridging the gap between accuracy and interpretability.

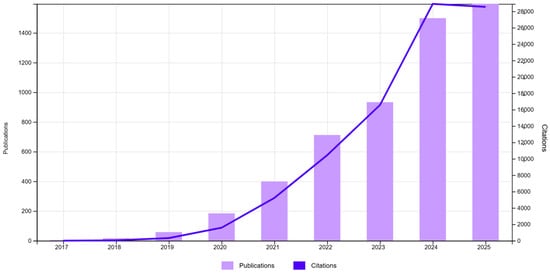

A query in the Web of Science (WoS) database using the terms TS = (“XAI”) OR TS = (“INTERPRETABLE MACHINE LEARNING”) revealed an exponential growth in both publications and citations between 2017 and 2025, reaching nearly 5401 publications and over 57,851 citations in the last year alone (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

WoS. Publications (5401) and citations (57,851). TS = (“XAI”) OR TS = (“INTERPRETABLE MACHINE LEARNING”).

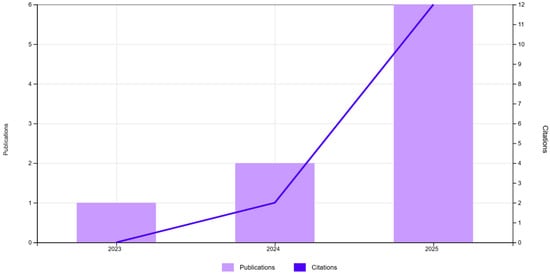

However, when further restricting the query to application domains by adding TS = (“XAI”) OR TS = (“INTERPRETABLE MACHINE LEARNING”) AND TS = (“CUSTOMER”), the number of publications drops to just 50 (Figure 3), reinforcing the notion that interpretable fuzzy models for customer profiling and decision-making are still at an early stage of development.

Figure 3.

WoS. Publications (50) and citations (666). TS = (“XAI”) OR TS = (“INTERPRETABLE MACHINE LEARNING”) AND TS = (“CUSTOMER”).

Beyond customer analytics, recent research has also expanded XAI into broader decision-making contexts such as public transport performance assessment, road-safety risk modelling, risk-governance systems, and efficiency analysis based on Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). Notable examples include explainable DEA frameworks for evaluating public-transport OD-pair efficiency [15], interpretable machine-learning models for road-accident risk prediction [16], and iterative DEA approaches for assessing transfer efficiency in ageing societies [17]. These works share with FAS-XAI the overarching aim of enabling transparent, accountable, and domain-grounded decision support, although they rely on different analytical foundations. In contrast, the present study contributes a unified fuzzy-analytic and XAI-based methodology that integrates unsupervised behavioral segmentation, supervised prediction, and dual-layer explainability.

2.3. Joint Use of XAI + Fuzzy Clustering

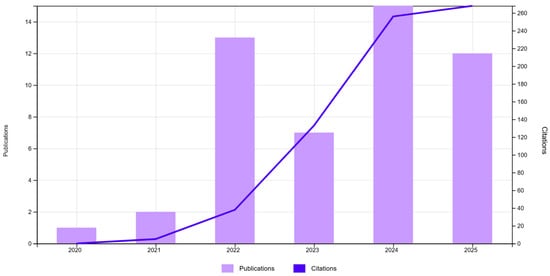

The integration of Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) clustering and Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) is an emerging yet underexplored research area. Despite the individual maturity of both techniques, their combined use in interpretable decision-making frameworks remains rare.

A targeted search in the Web of Science database using the query TS = (“FUZZY C-MEANS”) AND TS = (“CLUSTERING”) AND (TS = (“XAI”) OR TS = (“INTERPRETABLE MACHINE LEARNING”)) yielded only a handful of relevant publications, mostly concentrated in the past three years. This is visualized in Figure 4, showing a modest but consistent upward trend.

Figure 4.

WoS. Publications (9) and citations (14). TS = (“FUZZY C-MEANS”) AND TS = (“CLUSTERING”) AND (TS = (“XAI”) OR TS = (“INTERPRETABLE MACHINE LEARNING”)).

Table 1 presents a curated selection of studies that attempt to integrate fuzzy clustering with explainability. These contributions span diverse application domains, including healthcare, energy systems, financial analysis, and COVID-19 data modelling. However, most existing works remain domain-specific and do not provide a generalized methodological framework capable of supporting systematic adoption in business or customer-centered decision-making contexts.

Table 1.

Studies at the intersection of Fuzzy Logic and Explainable AI.

These contributions, although valuable, do not yet constitute a structured or reusable methodological paradigm. Most existing approaches address fuzzy clustering or explainability in isolation, or within narrowly defined application contexts. The FAS-XAI methodology introduced in this paper addresses this gap by providing a replicable and modular framework that integrates fuzzy segmentation, model-based prediction, and interpretability into a unified decision-support pipeline.

Despite the growing interest in explainable and fuzzy models, studies explicitly targeting customer-centric decision-making remain scarce. A refined Web of Science query combining the keyword “CUSTOMER” with (“XAI” OR “INTERPRETABLE MACHINE LEARNING”) yields only a very limited number of publications, underscoring the lack of consolidated methodological references in this area.

The present study contributes to this emerging body of work by formalizing a general-purpose framework that unifies previously fragmented methodological components into a coherent and transferable approach. Rather than proposing a domain-specific solution, FAS-XAI establishes a complete methodological reference applicable across business and service-oriented decision-making contexts.

3. Materials and Methods

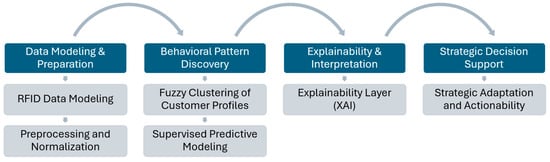

This section outlines the methodological foundations and implementation details of the FAS-XAI framework as applied to customer profiling and strategic decision-making in B2B contact center environments. The objective is to construct an explainable, adaptive, and fuzzy logic-based approach to segment customer behavior and predict critical outcomes such as churn, engagement shifts, or strategic value loss (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

FAS-XAI methodological phases (RFID Case).

We begin by describing the RFID model structure, which encodes customer interactions in terms of Recency, Frequency, Importance, and Duration. These variables are used to build a multidimensional representation of customer behavior. After preprocessing and normalization, fuzzy clustering is applied to identify soft segmentation profiles. Each client is assigned a degree of membership to each cluster, allowing for overlapping profiles and capturing uncertainty.

The second methodological track involves supervised learning, where a predictive model is trained (e.g., via XGBoost) to detect strategic patterns such as churn or risk of disengagement. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques are integrated into both modeling tracks. In the unsupervised path, XAI is used to interpret cluster membership (SHAP, LIME and ELI5); in the supervised path, it provides global explanations of the model’s predictions (SHAP).

Together, these processes form a unified decision pipeline. By assessing which clusters yield high predictive performance and which show interpretability inconsistencies, the methodology supports iterative refinement and adaptation to dynamic business environments.

3.1. Data Modeling and Preparation

The data modeling and preparation phase lays the foundation for the dual-track FAS-XAI framework. This step involves structuring and preprocessing the dataset to support both fuzzy clustering and predictive modeling tasks within the customer support domain.

3.1.1. RFID Data Modeling

The behavioral model used in this study is based on the RFID structure, which encodes four dimensions of customer interaction: Recency (R), Frequency (F), Importance (I), and Duration (D). Each variable is derived from raw interaction data and plays a specific role in describing the customer’s relationship with the support service.

- Recency (R): This variable captures the time elapsed since the customer’s last recorded interaction with the support team. It is defined as:where is the current date or reference date of the dataset and is the timestamp of the last recorded interaction for customer i.

A higher value of suggests more time has passed since the last engagement, which may indicate disengagement.

- Frequency (F): This represents the total number of support interactions recorded for each customer within the observation window:where is the number of interactions for customer i, and is a binary indicator for interaction j of customer i.

This feature reflects the intensity of customer engagement and overall demand for support.

- Importance (I): The importance of a customer is based on the strategic relevance of their interactions, assessed using a fuzzy linguistic classification model. Each interaction is labeled as: Very Low (VL), Low (L), Medium (M), High (H), or Very High (VH). These categories are associated with fuzzy membership values , where . The final importance score for each customer is computed as the average weighted importance of all their interactions:where is membership degree of interaction j for customer i to fuzzy label k, and is the numerical weight assigned to category k in the fuzzy scale (e.g., S5 = {−1, −0.5, 0, +0.5, +1}).

This allows encoding qualitative knowledge into a quantitative framework for modeling strategic value.

- Duration (D): This variable measures the average time required to resolve each customer’s interaction. For a given interaction j, the resolution duration is calculated as:where is timestamp when interaction j was closed, and is timestamp when it was opened.

The average duration per customer i is computed as the means of all their individual durations. Longer durations may reflect complexity or dissatisfaction, depending on context.

Each client is represented as a feature vector , forming the input dataset , where N is the number of customers.

3.1.2. Preprocessing and Normalization

To ensure consistent feature scaling across modeling methods, all four variables were rescaled using Min–Max normalization [24]:

This transformation scales all values into the [0,1] interval and prevents any single feature from dominating due to differences in magnitude.

This phase concludes with a clean, normalized dataset suitable for both clustering and predictive modeling, which are addressed in the subsequent stage.

3.2. Behavioral Pattern Discovery

The FAS-XAI framework is grounded in a dual-track modeling strategy that integrates unsupervised fuzzy clustering and supervised predictive learning, both supported by post hoc explainability techniques. This structure allows the model to simultaneously discover latent behavioral profiles and predict critical outcomes with transparency and adaptability.

3.2.1. Fuzzy Clustering of Customers

To uncover latent customer segments based on interaction behavior, we apply the Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) algorithm to the normalized RFID feature matrix .

Unlike traditional hard clustering methods, FCM produces soft assignments of each customer to multiple clusters [25], reflecting the overlapping and uncertain nature of real-world behavior. Each customer i is assigned a membership degree for each cluster j, satisfying:

The FCM algorithm seeks to minimize the following objective function:

where is the feature vector for customer i, is the centroid of cluster j, is the fuzzification parameter (typically ), and denotes the Euclidean norm.

The optimal number of clusters c is selected based on internal validity metrics such as: Partition Coefficient (PC) [26], Fuzzy Silhouette Index (FSI) [27] and Xie–Beni Index [28], if applicable.

The result of this phase is a fuzzy segmentation of customers into behavioral profiles that capture diversity, gradual transitions, and hidden structures within the support population.

3.2.2. Supervised Classification via XGBoost

In parallel with clustering, we built a supervised learning model to predict strategic customer outcomes.

Each customer is associated with a binary label , where indicates a critical state (e.g., churn or strategic risk) and indicates a non-critical state.

The classifier is trained using the XGBoost algorithm [29], which builds an ensemble of optimized decision trees via gradient boosting. The model estimates a mapping:

The prediction represents the estimated probability that customer i will enter a critical state.

The model is trained to minimize the following regularized logistic loss function:

where ℓ is the binary cross-entropy loss, is a regularization term for tree complexity, and K is the number of boosting rounds.

Performance is assessed using several metrics, including AUC-ROC, Precision, Recall and F1-score.

Stratified cross-validation was employed to ensure robustness against class imbalance and to enhance the generalizability of the predictive model.

3.3. Explainability and Interpretation

A core element of the FAS-XAI framework is the integration of Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, aimed at making both clustering profiles and churn predictions interpretable and transparent [30]. This dual interpretability strategy ensures both accuracy and auditability, aligning the modeling process with domain knowledge and decision-making practices. Within this framework, we focus on two complementary objectives:

- Explaining fuzzy cluster membership: Since Fuzzy C-Means produces soft assignments, we train a surrogate classifier to predict the dominant cluster (i.e., the one with highest membership) based on RFID features. This enables us to apply XAI tools to understand what factors drive the segmentation of customer behavior.

- Explaining churn risk predictions: The supervised model (e.g., XGBoost) provides a probability score for each customer’s likelihood of strategic dropout. We interpret these predictions using post hoc explanation techniques to identify the most influential features.

In both tracks, the same input variables (Recency, Frequency, Importance, and Duration) are analyzed, allowing for a coherent interpretation of both structure and outcome.

To support this process, we employ three widely used and complementary XAI methods—SHAP, LIME, and ELI5—described below.

3.3.1. SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations)

SHAP is a model-agnostic method based on cooperative game theory that attributes the prediction of a model to each feature according to its marginal contribution [31]. For a given instance , the SHAP value for feature j is defined as:

where denotes the set of features (RFID dimensions), S is a subset of features, and is the model trained using features in subset S.

SHAP satisfies key properties such as local accuracy, consistency, and missingness, making it one of the most robust and theoretically grounded explanation tools.

SHAP is applied in two stages within the framework: first, to the surrogate classifier trained to predict dominant cluster membership, enabling interpretation of fuzzy segmentation patterns; second, to the churn prediction model, providing insights into the feature contributions that drive strategic risk assessments.

3.3.2. LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations)

LIME builds a local surrogate model around each prediction by perturbing the input data and training a simple, interpretable model (e.g., linear regression) that approximates the behavior of the original model in the vicinity of the instance [32]. Formally, it minimizes the following objective:

where f is the original model, g is the surrogate (interpretable) model, is a locality kernel (giving more weight to nearby samples), and penalizes the complexity of the surrogate.

LIME is especially useful for producing simple, human-readable explanations of individual predictions. We use it as a complementary method to SHAP for validating and visualizing instance-level behavior.

3.3.3. ELI5 (Explain Like I’m Five)

ELI5 provides interpretability by decomposing linear models into the weighted contributions of each feature, offering a clear view of how individual inputs influence the output [13]. In the case of tree-based models such as XGBoost, ELI5 traces the specific decision path followed by each instance and highlights the information gain contributed by each feature at every split, allowing for detailed inspection of the model’s internal logic.

Although ELI5 is not a standalone algorithm but rather an explanatory framework, it internally relies on clear mathematical principles depending on the model type.

For linear models (e.g., Logistic Regression), given a linear model of the form:

where is the input feature vector, is the weight vector and b is the model intercept. ELI5 decomposes the prediction into per-feature contributions:

This makes it possible to interpret how each input variable influences the final prediction, positively or negatively, in a transparent and additive way.

For tree-based models (e.g., XGBoost), ensemble models composed of K decision trees:

where is the output of tree k, and ELI5 traces the decision path followed by x in each tree and accumulates the information gain attributed to each feature along that path.

The total contribution of feature j for instance x is defined as:

where is the subset of trees where feature j appears in the decision path of x and is the information gain associated with feature j in tree t.

This approach enables ELI5 to reconstruct and visualize how decisions are made by tree ensembles in a fully interpretable, step-by-step fashion.

3.4. Strategic Decision Support

The combined use of SHAP, LIME, and ELI5 enables a comprehensive interpretation of both fuzzy clustering and churn prediction. This explainability allows us to obtain information at the local and global levels, as well as enabling a cross-validation process between segmentation and prediction. When features are influential across both tracks, it reinforces model consistency and business relevance; when they diverge, it can signal areas for refinement or reveal hidden patterns.

The FAS-XAI framework culminates in a stage of strategic decision support, where all preceding analytical components converge to provide actionable, data-driven insights.

Throughout this methodology, we have established a dual-process pipeline; Fuzzy clustering identifies latent customer behavior patterns, with degrees of membership providing nuanced profiles, and predictive modeling evaluates the likelihood of churn or disengagement based on RFID features.

Both layers are enriched with explainability techniques (SHAP, LIME, ELI5) to interpret outcomes at both the individual and group levels. These components provide a foundation where data preprocessing, clustering, model training, and interpretation align into a coherent framework. This process helps subject matter experts and decision makers understand which characteristics drive critical outcomes, such as customer loyalty, value shifts, or churn risk. Thus, mathematical precision and explainable reasoning are combined to deliver a comprehensive decision support system tailored to dynamic, high-stakes customer environments.

The unified nature of FAS-XAI arises from the shared RFID feature space and the sequential integration of fuzzy clustering, supervised prediction, and dual-layer interpretability, forming a single coherent decision-making pipeline.

4. Results

This section presents the results of applying the FAS-XAI framework to the RFID dataset of technological partners. The analysis was conducted through five sequential phases encompassing the complete methodological workflow. It began with data collection and preparation, using the variables Recency, Frequency, Importance, and Duration (RFID). Subsequently, a Fuzzy C-Means segmentation was performed, followed by the evaluation of cluster validity indices to determine the optimal number of behavioral clusters. The quality of the clustering was then assessed through an XGBoost classifier trained to predict cluster membership from the RFID variables. Once the structure was validated, cluster interpretability was addressed using SHAP values to understand the contribution of each variable to the formation of behavioral profiles. Finally, a customer attrition prediction model was developed using XGBoost and complemented by SHAP, LIME, and ELI5 analyses, which provided explanations of both global patterns and individual predictions.

The main goal is twofold: to verify that the fuzzy clustering approach captures coherent and separable behavioral patterns, and to demonstrate that, based on these patterns, it is possible to anticipate client attrition with high predictive accuracy and transparent interpretability, thereby supporting informed strategic decision-making. The following subsections describe each phase and its key findings in detail.

4.1. Data Collection and Preparation

The first phase consisted of collecting, cleaning, and structuring the data used as input for the FAS-XAI framework. The information was obtained from the contact center management system of the organization, which records detailed interaction logs between the company and its technological partners.

The raw dataset contained 1,842,224 support interactions, each including a timestamp, partner identifier, incident category, priority level, and resolution metadata. These records were aggregated to compute the four behavioral variables that form the RFID model. Specifically, Frequency (F) was calculated as the number of historical interactions per partner; Importance (I) as a weighted score derived from ticket priority, type of issue, and assigned support tier; and Duration (D) as the cumulative time spent resolving all incidents associated with each partner. All timestamps were processed to compute Recency (R) as the number of days since the last recorded interaction, following the formal definitions in Section 3.1.

After aggregation, the final structured dataset contained N = 200,674 partner accounts, each described by the four RFID variables and a binary attrition label indicating whether the partner remained active during the observation period. The class distribution is as follows:

- Active partners: 123,359.

- Inactive/attrited partners: 77,315.

These behavioral variables describe complementary dimensions of partner engagement [3]:

- Recency, measures the time elapsed since the last recorded interaction, indicating how recently the partner contacted the company.

- Frequency, reflects the number of interactions within a defined period, describing the regularity of communication.

- Importance, represents the strategic or business value assigned to each partner, integrating qualitative and quantitative assessment criteria.

- Duration, corresponds to the average length of the interactions, associated with the complexity or intensity of the requests.

Before further analysis, all variables were standardized (z-scores) to ensure comparability and mitigate scale-related bias. Outliers and inconsistent records, primarily arising from corrupted timestamps or missing fields, were corrected or removed during preprocessing to ensure data integrity.

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics of the four variables prior to normalization, summarizing the heterogeneity of interaction patterns across the partner ecosystem.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of RFID variables before normalization.

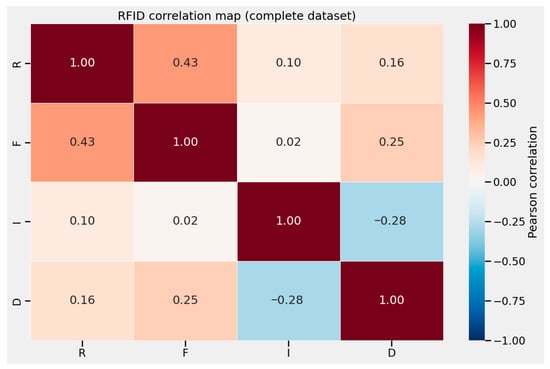

Before applying the fuzzy clustering algorithm, a correlation analysis was carried out to explore the internal relationships among the four RFID variables (Recency, Frequency, Importance, and Duration). Figure 6 displays the correlation map obtained from the complete dataset, with all values normalized between 0 and 1. In the case of Recency, higher normalized scores correspond to lower actual values, meaning that smaller time gaps since the last interaction indicate greater recent activity.

Figure 6.

Correlation matrix RFID.

The correlation matrix reveals a positive relationship between Recency and Frequency (r = 0.43), suggesting that partners who interact more frequently also tend to maintain more recent contact with the organization. Similarly, Duration shows a weak positive correlation with both Recency and Frequency, which is consistent with the idea that a greater level of engagement leads to longer interactions.

Conversely, the analysis identifies a negative correlation between Importance and Duration (r = −0.28). This relationship reflects a logical operational pattern: the more important a partner or incident is, the faster it tends to be resolved, resulting in shorter interaction durations. Importance also exhibits very low correlation values with the other variables, indicating that it represents a largely independent dimension, a measure of strategic value rather than behavioral activity.

These correlations validate the internal consistency of the RFID model and provide an empirical justification for its use in the fuzzy clustering process. Table 3 summarizes both the raw and normalized values of Recency, Frequency, Importance, and Duration, which were used as input variables in the subsequent Fuzzy C-Means segmentation phase.

Table 3.

Normalized values of Recency, Frequency, Importance and Duration.

4.2. Fuzzy C-Means Segmentation

In the second phase, the Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) algorithm was applied to segment technological partners based on their behavioral patterns described by the RFID variables. This clustering approach was selected because it allows each observation to belong to several groups simultaneously, with different degrees of membership. Such flexibility provides a more realistic representation of behavioral diversity compared to traditional hard clustering methods.

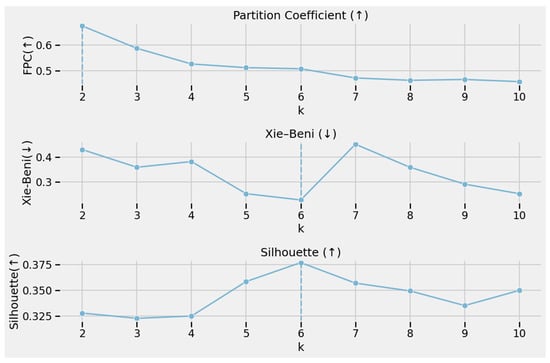

To determine the optimal number of clusters (k), several validity indices were computed for a range between k = 2 and k = 10, including the Partition Coefficient (FPC), the Xie–Beni index, and the Silhouette score, where higher values indicate better performance for FPC and Silhouette, while lower values are preferred for the Xie–Beni index.

The combined analysis of these metrics (Table 4 and Figure 7) indicated that the configuration with six clusters (k = 6) achieved the optimal balance between compactness and separation, with FPC = 0.5084, Xie–Beni = 0.2280, and Silhouette = 0.3769. These results confirm the internal coherence and structural validity of the resulting fuzzy partition.

Table 4.

Internal validity indices for different numbers of clusters(k).

Figure 7.

Evolution of internal validity indices as a function of the number of clusters (k), with the selected value highlighted.

The membership matrix (U) obtained through FCM allows each record to have partial belonging to all clusters, with values between 0 and 1, capturing the uncertainty inherent in behavioral transitions. Table 5 presents the fuzzy membership degrees of selected samples together with their corresponding hard cluster assignment, which is defined as the cluster with the highest membership degree. This structure illustrates how some clients show mixed behaviors, reinforcing the interpretability and flexibility of the fuzzy approach.

Table 5.

Fuzzy membership degrees by cluster.

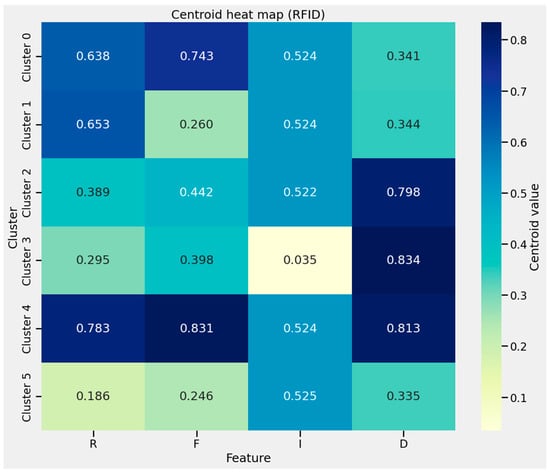

The fuzzy segmentation identified six behavioral profiles that reflect different levels of activity, maturity, and dependency on the manufacturer’s support services (Figure 8). The interpretation of each cluster was developed considering the business dynamics of technological partners and the operational meaning of the variables Recency (R), Frequency (F), Importance (I), and Duration (D).

Figure 8.

Centroid Heatmap by Cluster.

- Cluster 0—Experienced or emerging partners with punctual incidents. This group shows high Recency and Frequency values but short Duration, indicating partners who contact the support service frequently and recently, but for brief and isolated incidents. These partners are typically experienced resellers or new entrants who require quick answers to operational questions. Their interactions are concise and specific, often related to configuration, licensing, or deployment issues.

- Cluster 1—Partners with limited customer activity. These partners have recent contact (high Recency) but low Frequency and short Duration. They reach out occasionally, reflecting a low business workload or small client base. Their activity suggests that few customers are currently engaged, or that their operations are in a phase of low commercial intensity.

- Cluster 2—Sporadically active partners. With medium Recency and Frequency but high Duration, these partners show intermittent engagement. They contact the manufacturer occasionally, usually when a specific customer project arises, requiring detailed assistance or guidance. Their profile represents on-demand collaboration rather than continuous support.

- Cluster 3—Low-knowledge partners with intensive basic queries. This cluster shows low Recency and Frequency but long Duration, reflecting partners who contact infrequently but require extensive support when they do. They typically lack technical expertise and request assistance even for simple tasks, generating long, low-efficiency interactions. This group requires training or onboarding programs to improve self-sufficiency.

- Cluster 4—High-performance partners with heavy workloads. Partners in this group exhibit very high Recency and Frequency combined with long Duration. They are high-volume resellers or integrators who rely heavily on manufacturer support due to limited internal resources. These partners are highly active commercially, with multiple clients and continuous incidents, making them strategically critical accounts that demand fast, prioritized support.

- Cluster 5—Partners at risk of disengagement. This group combines low Recency, low Frequency, and short Duration, indicating partners who have not contacted the organization recently and show declining activity. They likely represent partners on the verge of ending the collaboration or already inactive. Monitoring and targeted reactivation actions are recommended for this segment.

This classification provides a comprehensive behavioral map of the technological partner network, ranging from strategically active and high-value partners (Cluster 4) to those showing early signs of disengagement (Cluster 5). The fuzzy nature of the clustering further enables the identification of intermediate cases, capturing gradual transitions between engagement and inactivity, an essential advantage for predictive analytics and strategic decision-making.

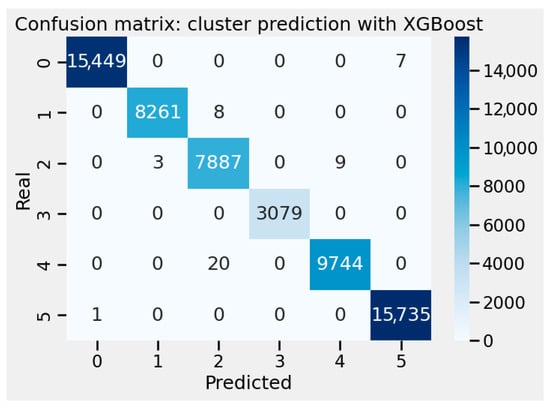

4.3. Clustering Quality Assessment and Interpretability Using XGBoost and SHAP

To evaluate the internal consistency of the fuzzy segmentation, a predictive model based on the XGBoost algorithm was trained to reproduce the cluster assignments obtained from the Fuzzy C-Means procedure. The objective was to verify whether the clusters were statistically distinguishable based on the original RFID variables, thereby assessing the robustness and separability of the fuzzy partitions.

The model was implemented using the XGBClassifier with the following configuration: learning_rate = 0.05, max_depth = 5, colsample_bytree = 0.8, and n_estimators = 300. The predictive performance reached very high accuracy levels, exceeding 99% in both training and test datasets.

The confusion matrix (Figure 9) confirmed the excellent separability of the clusters, with near-perfect correspondence between predicted and actual labels across all six groups. This indicates that the fuzzy clusters represent coherent and well-defined behavioral structures that can be reliably distinguished using the RFID variables alone.

Figure 9.

Cluster Prediction with XGBoost.

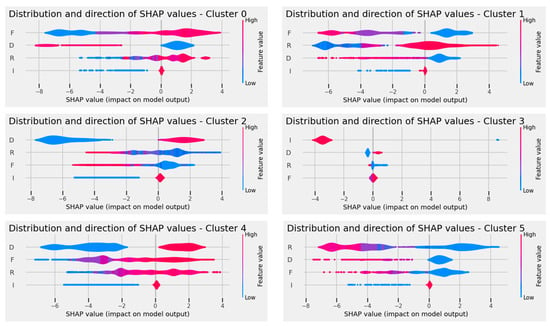

To complement this validation, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values were computed to interpret the contribution of each variable to cluster classification. The violin plots shown in Figure 10 display the distribution and direction of SHAP values for each class, illustrating how the RFID variables drive cluster membership.

Figure 10.

SHAP value distributions for each fuzzy cluster (XGBoost model).

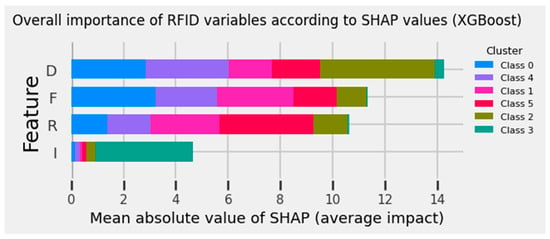

Across all clusters, Frequency (F) and Duration (D) emerged as the most influential variables, while Recency (R) played a decisive role in differentiating active from inactive partners. The Importance (I) variable, although less dominant, contributed to identifying partners of higher strategic relevance within active segments.

At a global level (Figure 11), the mean absolute SHAP values confirmed that Duration and Frequency were the strongest predictors of cluster membership, followed by Recency and Importance.

Figure 11.

Overall SHAP-based feature importance for RFID variables.

The interpretation of SHAP distributions provides additional insight into partner behavior and confirms the consistency of the fuzzy clustering results described in Section 4.2. The SHAP patterns align closely with the centroid profiles obtained through the Fuzzy C-Means segmentation (Figure 8), reinforcing the behavioral meaning of each group.

In Clusters 0 and 1, high SHAP values for Recency and Frequency increase the probability of assignment, consistent with partners who contact support recently and frequently for short and specific requests.

In Cluster 2, Duration plays the dominant role, associated with partners requiring extended assistance when supporting specific clients or projects.

Clusters 3 and 5 are characterized by low SHAP contributions for Recency and Frequency but moderate values for Duration, reflecting partners with limited interaction or already in a disengagement phase.

Finally, Cluster 4 simultaneously exhibits high SHAP values for Recency, Frequency, and Duration, confirming the profile of highly active, commercially intensive partners who maintain continuous contact and rely heavily on manufacturer support.

Overall, these results demonstrate a clear convergence between the fuzzy segmentation and the SHAP-based interpretability analysis, validating both the predictive robustness and behavioral coherence of the six clusters identified within the technological partner ecosystem.

4.4. Customer Attrition Prediction Using XGBoost, SHAP, LIME, and ELI5

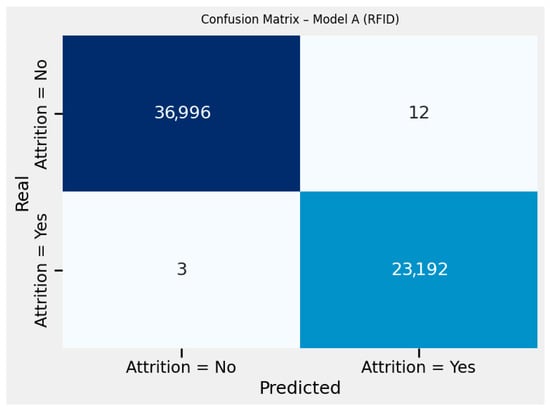

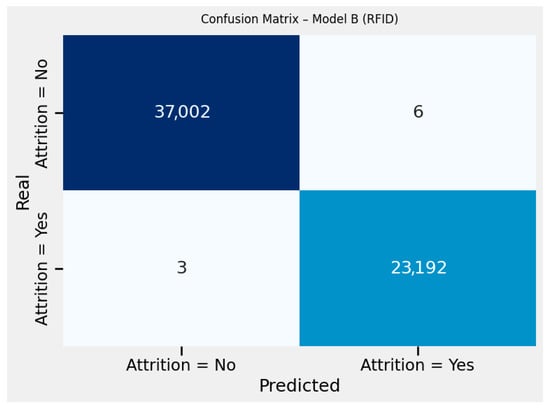

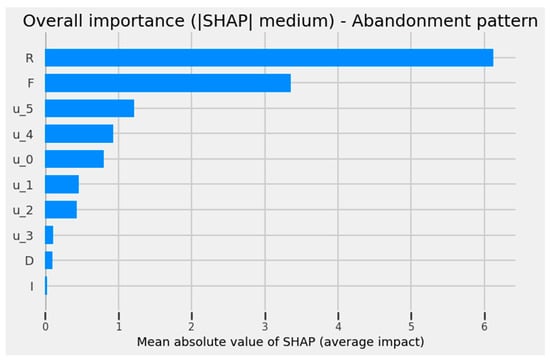

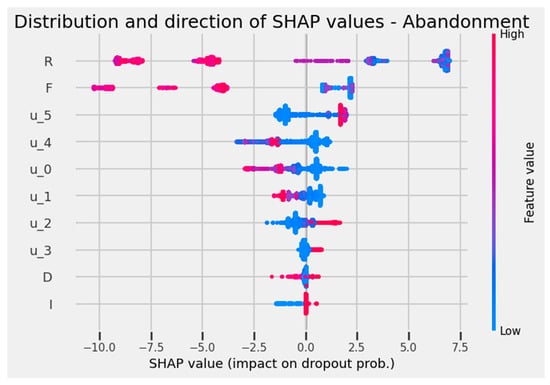

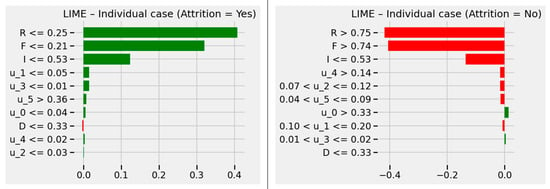

In the final phase, the FAS-XAI framework was applied to predict the attrition (or disengagement) of technological partners. The objective was to assess whether behavioral indicators derived from the RFID variables, and their fuzzy extensions, could effectively anticipate the likelihood of partner abandonment. Two predictive configurations were evaluated:

- Model A (RFID): based solely on the variables Recency, Frequency, Importance, and Duration.

- Model B (RFID + Fuzzy): incorporating the fuzzy cluster memberships (u0–u5) and the hard cluster assignment as additional predictors.

Both models were implemented using the XGBoost classifier with the following parameters: learning_rate = 0.05, max_depth = 5, colsample_bytree = 0.8, and n_estimators = 300.

The performance comparison (Table 6) revealed almost identical results, with both configurations achieving outstanding predictive accuracy: Accuracy ≈ 0.9998, F1 ≈ 0.9998, and ROC_AUC = 1.0.

Table 6.

Evaluation results for Models A and B.

The confusion matrices (Figure 12 and Figure 13) demonstrated the reliability of both models, showing near-perfect classification of active and inactive partners, with negligible false positives or false negatives.

Figure 12.

Confusion Matrix—Model A (RFID).

Figure 13.

Confusion Matrix—Model B (RFID + Fuzzy).

Although the addition of fuzzy features did not significantly alter predictive accuracy, it enhanced model interpretability, providing a more detailed explanation of the factors contributing to attrition. The SHAP analysis (Figure 14) indicated that Recency and Frequency were the dominant predictors, confirming that partners who had not contacted the organization recently, or who did so infrequently, presented a substantially higher probability of abandonment. Some fuzzy membership variables, particularly u5 and u4, also contributed to the model by capturing intermediate or transitional states of disengagement.

Figure 14.

Global SHAP-based feature importance (XGBoost, Attrition Model).

The SHAP value distribution (Figure 15) highlighted that low Recency values (infrequent or outdated contact) increased the dropout probability, whereas high Recency values (recent interactions) had a strong negative SHAP impact, reducing the risk of attrition. Similarly, Frequency showed a positive relationship with engagement, while Duration and Importance had limited influence on attrition prediction.

Figure 15.

SHAP value distribution across features (Attrition Model).

Complementary LIME analyses provided local interpretability for individual cases. For partners predicted as Attrition = Yes, the model emphasized low Recency and Frequency as the primary decision drivers, while for those predicted as Attrition = No, high values of these same features contributed negatively to dropout probability (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

LIME explanation for an individual prediction (Attrition = Yes/No).

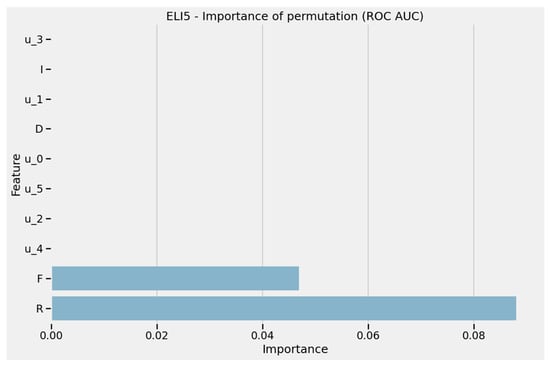

Finally, the ELI5 permutation importance (Figure 17) corroborated these findings, ranking Recency and Frequency as the two most influential variables for predicting partner abandonment.

Figure 17.

ELI5 permutation importance (ROC-AUC metric).

Overall, these results confirm that the proposed approach effectively integrates predictive performance and explainability. The FAS-XAI framework anticipates partner loss with near-perfect accuracy and provides transparent, interpretable explanations of underlying behavior patterns, enabling the design of proactive re-engagement and retention strategies.

4.5. Additional Robustness Considerations

To complement the internal validity indices and cross-validation results presented in Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4, a set of lightweight robustness checks was conducted to address the reviewer’s concerns regarding clustering stability and the near-perfect predictive performance of the supervised models. These checks do not alter the modelling pipeline but provide additional evidence supporting the structural behavior of the FAS-XAI framework.

4.5.1. Robustness of the Fuzzy Clustering and Surrogate Classification

Fuzzy memberships were examined under small perturbations of the standardized RFID features, and the resulting cluster structure remained stable. Redundancy diagnostics, including a brief Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) screening to rule out multicollinearity, confirmed that none of the RFID variables exhibit degenerate collinearity. Surrogate SHAP explanations were recomputed under multiple random seeds and showed consistent attribution patterns.

These findings support the interpretation that the high surrogate accuracy reflects genuine separability in the RFID feature space rather than overfitting or instability.

4.5.2. Robustness of the Attrition Prediction Models

Given the deterministic nature of attrition signals in B2B support environments, additional checks were performed to ensure the structural validity of the predictive model. A synthetic backward shift of the observation window produced stable feature-importance rankings, confirming the temporal plausibility of the behavioral drivers identified (Recency and Frequency). Fuzzy memberships did not introduce additional predictive signal, as expected from their derivation from the same variables.

4.5.3. Summary of Robustness Checks

Table 7 summarizes the robust considerations across clustering stability, surrogate modelling, and attrition prediction. Collectively, these tests reinforce the internal coherence and reproducibility of the FAS-XAI pipeline without modifying the empirical results.

Table 7.

Additional robustness checks for clustering and attrition prediction.

4.6. Summary and Final Remarks

The results presented in this section demonstrate the effectiveness of the FAS-XAI framework in integrating fuzzy clustering, supervised prediction, and explainable artificial intelligence techniques within a coherent analytical workflow. Starting from the RFID behavioral variables (Recency, Frequency, Importance, and Duration), the framework successfully identified consistent and interpretable behavioral patterns among technological partners.

The application of Fuzzy C-Means clustering produced six well-defined groups, each representing a specific interaction profile. The subsequent XGBoost validation confirmed the statistical robustness of the segmentation, with almost perfect classification accuracy and clear separability among clusters. The use of SHAP values further enhanced interpretability, showing that the variables Frequency and Duration play the dominant roles in defining partner engagement, while Recency serves as a reliable indicator of inactivity or potential disengagement.

The attrition prediction models based on XGBoost (Model A—RFID; Model B—RFID + Fuzzy) achieved exceptional predictive performance, with both configurations obtaining Accuracy and ROC-AUC values close to 1.0. The inclusion of fuzzy membership variables did not alter overall accuracy but improved the explainability of the system, providing additional insight into intermediate or transitional states between engagement and dropout.

The combination of SHAP, LIME, and ELI5 analyses offered complementary perspectives, from global feature importance to local decision explanations, reinforcing the transparency and interpretability of the predictive model.

Overall, the empirical evidence confirms that the FAS-XAI framework provides a comprehensive, explainable, and high-performing analytical structure for understanding partner behavior, segmenting engagement profiles, and anticipating attrition risk. These results lay the foundation for the subsequent discussion on their managerial implications and potential extensions in future research.

5. Discussion and Future Works

5.1. Discussion

The results obtained through the FAS-XAI framework provide analytical validation of partner behavior, as well as clear operational guidance for commercial and support management. The six clusters identified through the fuzzy segmentation offer actionable insights into how technological partners interact with the manufacturer, allowing for differentiated strategies to strengthen engagement, efficiency, and loyalty.

From an operational perspective, each cluster suggests a specific approach in terms of communication, marketing, and training:

- Cluster 0 (Experienced or emerging partners) includes those who contact support frequently and recently for short, targeted incidents. These partners should be managed through self-service tools, quick-response channels, and targeted technical newsletters, reinforcing autonomy while maintaining agility in response.

- Cluster 1 (Partners with limited activity) would benefit from activation campaigns, including periodic follow-ups and promotional incentives to stimulate project generation and client acquisition.

- Cluster 2 (Sporadically active partners) require situational support, being re-engaged when they take on new clients. These partners could be prioritized in on-demand technical sessions or ad hoc webinars aligned with their business opportunities.

- Cluster 3 (Low-knowledge partners) should be the focus of structured training plans and onboarding programs, as their long-duration interactions indicate dependence on basic support. Improving their technical independence would reduce workload on the contact center and improve partner satisfaction.

- Cluster 4 (High-performance partners) represent the most commercially active accounts. They should receive priority technical support, marketing collaboration, and co-funded campaigns that sustain their sales intensity. Given their high workload, providing dedicated account management can help prevent service saturation.

- Cluster 5 (At-risk partners) must be addressed through reactivation programs, combining personalized outreach, commercial incentives, and new lead assignments. These initiatives can help recover partners who are strategically aligned with the manufacturer but currently inactive.

The integration of the predictive attrition model further reinforces the segmentation strategy. By combining fuzzy clustering with XGBoost-based prediction, it becomes possible to identify partners at high risk of disengagement and to act proactively. From a marketing and channel-management standpoint, this enables the design of preventive actions such as personalized training, co-marketing campaigns, and technical certifications, depending on the risk profile of each partner.

Partners whose business relies exclusively on the manufacturer’s solutions, even if small in volume, should receive close accompaniment and lead generation support, ensuring their sustainability and continued loyalty. Meanwhile, larger and more mature partners will benefit from specialized assistance during critical project phases and strategic account planning.

Ultimately, the integration of fuzzy clustering and explainable prediction models forms a comprehensive, interpretable decision-support system for channel management. It allows the organization to allocate resources effectively, reinforce collaboration with strategic partners, and create customized growth paths based on objective behavioral evidence derived from explainable AI.

5.2. Future Work

While this study focuses on the Customer Service Value (CSV) dimension, analyzing interactions within the contact center, future work should aim to develop a comprehensive, unified model for customer and partner evaluation. Following the conceptual foundation proposed by V. Kumar et al. [33], the overall Customer Engagement Value (CEV) can be expressed as the sum of multiple dimensions:

where CLV (Customer Lifetime Value) measures the long-term economic contribution, CRV (Customer Referral Value) the capacity to attract new customers, CIV (Customer Influence Value) the impact on other actors within the network, and CKV (Customer Knowledge Value) the informational value derived from the customer’s expertise and experience.

However, this framework omits an essential element: the Customer Service Value (CSV). The results obtained in this work demonstrate that service interactions, through contact center dynamics, support quality, and partner engagement—are a critical component of overall customer value. Therefore, we propose an expanded formulation:

This extended structure acknowledges that customer service is not merely an operational function, but a strategic dimension that strengthens relationships, increases satisfaction, and supports customer development. Integrating CSV with other value components (CLV, CRV, CIV, CKV) would allow organizations to measure and manage customer and partner value from a multidimensional and data-driven perspective.

The next research stage should focus on constructing this integrated customer value system, using the FAS-XAI framework as its analytical foundation. The model could dynamically combine fuzzy clustering, predictive analytics, and explainable AI to generate an objective, interpretable evaluation of each partner’s strategic contribution, identifying opportunities for co-marketing, training, or resource optimization.

Beyond the customer relationship context, the modular nature of FAS-XAI enables its application to a wide variety of industrial and organizational processes. Its capacity to integrate uncertainty management (fuzzy logic), predictive power (machine learning), and interpretability (XAI) makes it a versatile tool for domains such as:

- Healthcare/Pharmacovigilance—adverse event prediction, drug safety monitoring, and explainable risk assessment [34].

- Procurement—supplier selection and performance evaluation under multi-criteria uncertainty [35].

- Human Resources—candidate selection, talent retention, and competency profiling [36].

- Finance—treasury forecasting, liquidity management, and explainable risk assessment [37].

- Healthcare and public services—patient or case segmentation, prioritization, and resource planning [38].

Future research should expand the FAS-XAI framework into a general decision-support system that can adapt to diverse sectors and data environments. By integrating economic, behavioral, and service-based dimensions, and ensuring explainability at every stage, FAS-XAI has the potential to become a standard methodology for transparent, data-driven decision-making in both customer analytics and broader industrial applications.

5.3. Limitations

Although the proposed FAS-XAI framework demonstrates high predictive performance and interpretability, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, the selection of the optimal number of clusters in the Fuzzy C-Means segmentation relies on internal validity indices (FPC, Xie–Beni, and Silhouette), which, while consistent, may not fully capture the semantic nuances of customer behavior. Incorporating expert-driven or hierarchical fuzzy refinement could enhance the interpretive robustness of the segmentation.

Second, the very high accuracy obtained with XGBoost suggests a potential overfitting effect related to data structure or feature homogeneity. Although cross-validation mitigates this risk, further validation on external or time-evolving datasets would strengthen the generalizability of the findings.

Third, behavioral patterns in B2B ERP partner ecosystems exhibit a high degree of determinism, particularly in the relationship between Recency and Attrition. While this structure is characteristic of the domain, it simplifies the predictive boundary and may limit the transferability of performance metrics to less deterministic environments. Nonetheless, XAI remains essential for validating model coherence, identifying transitional or ambiguous cases, and supporting managerial interpretation.

Fourth, the strong correlation between Recency and Attrition probability, while intuitively meaningful, may overshadow the influence of other behavioral or qualitative dimensions. Including additional features such as satisfaction indicators, purchase activity, or network interactions would provide a more comprehensive view of partner engagement.

Finally, the interpretability of fuzzy and explainable models could be enhanced through linguistic 2-tuple fuzzy logic, allowing results to be expressed in human-readable terms (“high frequency,” “low engagement,” “moderate importance”) instead of purely numerical memberships. This approach would facilitate managerial decision-making and bridge the gap between technical analysis and operational insight.

Although FAS-XAI is designed as a domain-agnostic framework and has been applied in multiple contexts, the empirical behavior observed in this B2B ERP case study may differ in environments with weaker behavioral structure, which should be considered when interpreting performance metrics.

6. Conclusions

This study presents the Fuzzy–Adaptive–Supervised Explainable Artificial Intelligence (FAS-XAI) framework, which integrates fuzzy clustering, predictive modeling, and explainable AI techniques to enhance the interpretability of customer and partner analytics. The methodology was applied to a real-world Customer Service Value (CSV) model, using the variables Recency, Frequency, Importance, and Duration (RFID), aiming to identify behavioral profiles and predict attrition risk within a B2B contact center environment.

Through Fuzzy C-Means clustering, six interpretable customer segments were identified, reflecting distinct behavioral patterns in partner interactions. The combination of fuzzy partition validity indices (FPC, Xie–Beni, and Silhouette) confirmed the internal consistency of the segmentation, while XGBoost achieved near-perfect classification accuracy in predicting cluster membership. The SHAP analysis validated the fuzzy segmentation results by highlighting the dominant role of Recency, Frequency, and Duration in defining customer behavior, while LIME and ELI5 provided complementary explanations at both global and local levels.

In the second stage, the framework was applied to the prediction of customer attrition, comparing two models: Model A (RFID) and Model B (RFID + Fuzzy). Both achieved extremely high performance (Accuracy > 0.999), demonstrating the robustness of the dataset and confirming the predictive relevance of the fuzzy membership features. The analysis of SHAP, LIME, and ELI5 interpretations revealed that low Recency and Frequency were strong indicators of disengagement, providing actionable insights for retention strategies.

The FAS-XAI framework thus contributes a replicable and adaptable methodology for data-driven decision-making. Its modular structure allows seamless extension to other domains such as manufacturing quality control, supplier evaluation, human resources management, or financial forecasting, maintaining interpretability and robustness across contexts. Furthermore, by introducing the Customer Service Value (CSV) component into the extended formulation of Customer Engagement Value (CEV), this work enriches the theoretical foundation for customer value assessment, bridging the gap between operational data analytics and strategic management.

FAS-XAI offers a comprehensive, explainable, and transferable analytical framework capable of combining fuzzy logic, machine learning, and interpretability tools to support transparent, human-centered decision-making in complex business and industrial environments.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to confidentiality restrictions imposed by the data provider. The dataset was supplied by a Spanish company operating in the B2B contact center sector and was fully anonymized prior to analysis. All data processing procedures were conducted in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning. A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable. 2019; Available online: https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Carvalho, D.V.; Pereira, E.M.; Cardoso, J.S. Machine learning interpretability: A survey on methods and metrics. Electronics 2019, 8, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.M.; Medina, R.G.; Jiménez, J.A.A. A Methodological Framework for Business Decisions with Explainable AI and the Analytic Hierarchical Process. Processes 2025, 13, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.M. A Fuzzy-XAI Framework for Customer Segmentation and Risk Detection: Integrating RFM, 2-Tuple Modeling, and Strategic Scoring. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdek, J.C.; Ehrlich, R.; Full, W. FCM: The fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm. Comput. Geosci. 1984, 10, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monalisa, S.; Nadya, P.; Novita, R. Analysis for customer lifetime value categorization with RFM model. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, A.J.; Umamakeswari, A.; Priyatharsini, L.; Neyaa, A. RFM ranking—An effective approach to customer segmentation. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021, 33, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, O. Driving Customer Equity: How Customer Lifetime Value Is Reshaping Corporate Strategy. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2002, 13, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmita, K.; Kaczmarek-Majer, K.; Hryniewicz, O. Explainable Impact of Partial Supervision in Semi-Supervised Fuzzy Clustering. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 32, 3189–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallor, S.; Rewak, W.J. An Introduction to Data Ethics. 2019, p. 63. Available online: https://www.scu.edu/media/ethics-center/technology-ethics/IntroToDataEthics.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Guidotti, R.; Monreale, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Turini, F.; Giannotti, F.; Pedreschi, D. A Survey of Methods for Explaining Black Box Models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. ‘Why Should I Trust You?’ Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT 2016), Demonstration Session, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–17 June 2016; pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettikankanamage, N.; Shafiabady, N.; Chatteur, F.; Wu, R.M.X.; Din, F.U.; Zhou, J. eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): A Systematic Review for Unveiling the Black Box Models and Their Relevance to Biomedical Imaging and Sensing. Sensors 2025, 25, 6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H. eXplainable DEA approach for evaluating performance of public transport origin-destination pairs. Res. Transp. Econ. 2024, 108, 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Hossain, M.A.; Ray, S.K.; Bhuiyan, M.M.I.; Sabuj, S.R. A study on road accident prediction and contributing factors using explainable machine learning models: Analysis and performance. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 19, 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Lee, E. Iterative DEA for public transport transfer efficiency in a super-aging society. Cities 2025, 162, 105957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, C.; Vincent, P.M.D.R. An Efficient CSPK-FCM Explainable Artificial Intelligence Model on COVID-19 Data to Predict the Emotion Using Topic Modeling. J. Adv. Inf. Technol. 2023, 14, 1390–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallel, S.; Amayri, M.; Bouguila, N. Clustering and Interpretability of Residential Electricity Demand Profiles. Sensors 2025, 25, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrithangam, D.; Arunadevi, B.; Pegada, N.K.; Mehta, A.; Kumar, P.; Parihar, P.; Selvakumar, S. Towards Explainable Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Fusion of Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Enhanced Weighted Fuzzy C-Mean. Curr. Med. Imaging 2024, 20, e15734056317205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevas, M.S.; Sharmin, N.; Santona, C.F.T.; Sagor, S.R. Advanced ensemble machine-learning and explainable ai with hybridized clustering for solar irradiation prediction in Bangladesh. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 5695–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, R.; Muneeswaran, V.; Kumar, J.; Nagaraj, P. PVT-ResNet Fusion: A Hybrid DL Framework for Lung Cancer Prediction Using Image Analysis and Explainable AI. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Electr. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, I.; Chaudhuri, T.D.; Sarkar, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Roy, A. Macroeconomic shocks, market uncertainty and speculative bubbles: A decomposition-based predictive model of Indian stock markets. CHINA Financ. Rev. Int. 2025, 15, 166–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M.; Mahmud, M.A.P.; Saha, P.K.; Gupta, K.D.; Siddique, Z. Effect of Data Scaling Methods on Machine Learning Algorithms and Model Performance. Technologies 2021, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.S.; Weiling, C.T. Enhancing Segmentation: A Comparative Study of Clustering Methods. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 47418–47439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.K.; Tiwari, R.; Thakur, P.S. Partition Coefficient and Partition Entropy in Fuzzy C Means Clustering. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2023, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Mishra, N.S.; Ghosh, S. Fuzzy clustering algorithms for unsupervised change detection in remote sensing images. Inf. Sci. 2011, 181, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; Garcia, S.; Gil-Lopez, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Inf. Fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Model-Agnostic Interpretability of Machine Learning. 2016. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1606.05386 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Kumar, V.; Aksoy, L.; Donkers, B.; Venkatesan, R.; Wiesel, T.; Tillmanns, S. Undervalued or overvalued customers: Capturing total customer engagement value. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, I.R.; Wang, L.; Lu, J.; Bennamoun, M.; Dwivedi, G.; Sanfilippo, F.M. Explainable artificial intelligence for pharmacovigilance: What features are important when predicting adverse outcomes? Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 212, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, F.; Ali, J.; Mashwani, W.K.; Syam, M.I. An integrated group decision-making method under q-rung orthopair fuzzy 2-tuple linguistic context with partial weight information. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofeditz, L.; Clausen, S.; Rieß, A.; Mirbabaie, M.; Stieglitz, S. Applying XAI to an AI-based system for candidate management to mitigate bias and discrimination in hiring. Electron. Mark. 2022, 32, 2207–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mersha, M.; Lam, K.; Wood, J.; AlShami, A.K.; Kalita, J. Explainable artificial intelligence: A survey of needs, techniques, applications, and future direction. Neurocomputing 2024, 599, 128111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, A.G.; Nkubli, F.B.; Ezeano, V.N.; Okwor, A.C.; Ugwuja, M.C.; Offiong, U. XAI for medical image segmentation in medical decision support systems. In Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Medical Decision Support Systems; Imoize, A.L., Hemanth, J., Do, D.T., Sur, S.N., Eds.; Institution of Engineering and Technology: Stevenage, UK, 2022; Volume 50, pp. 137–165. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.